Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Definition

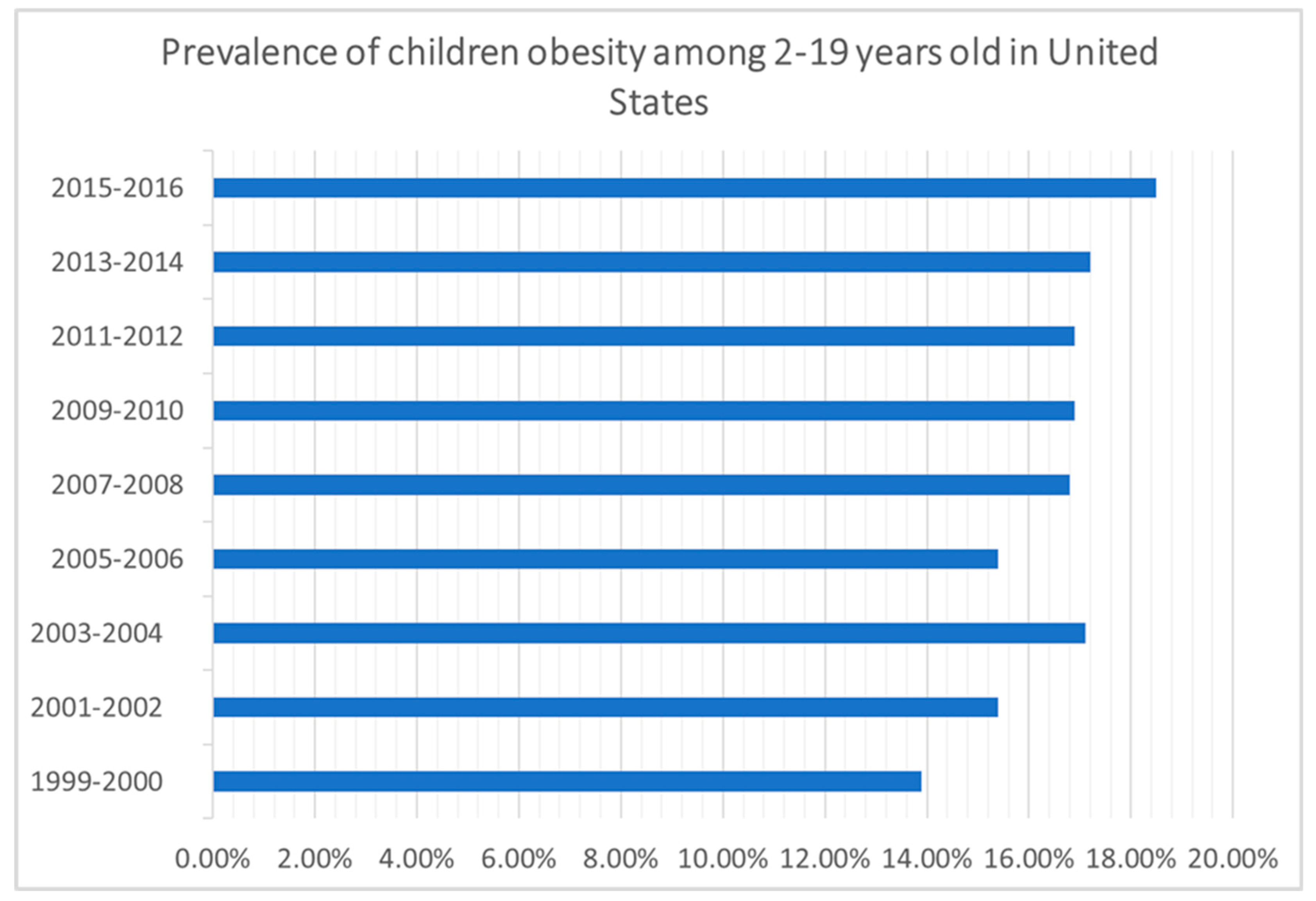

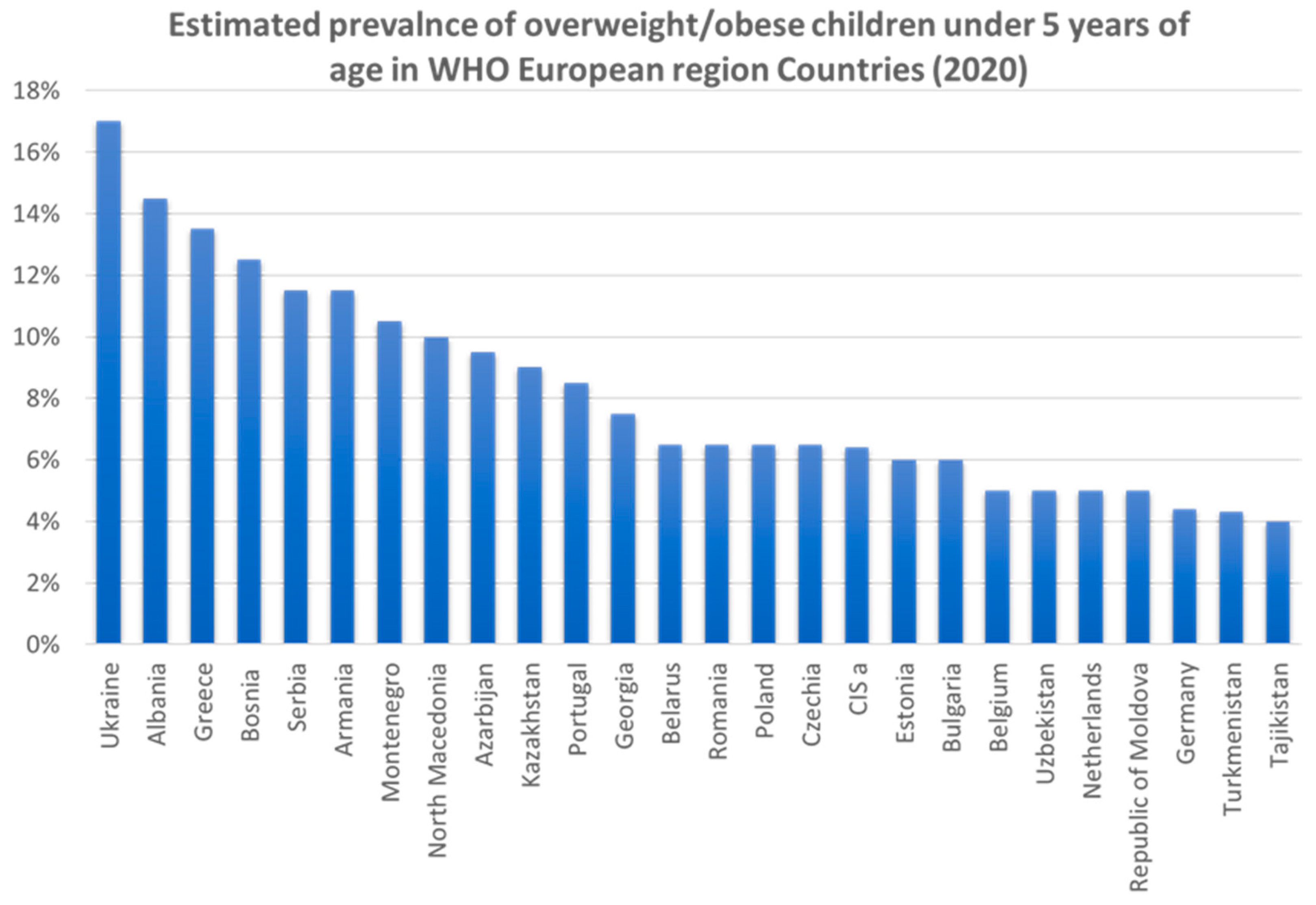

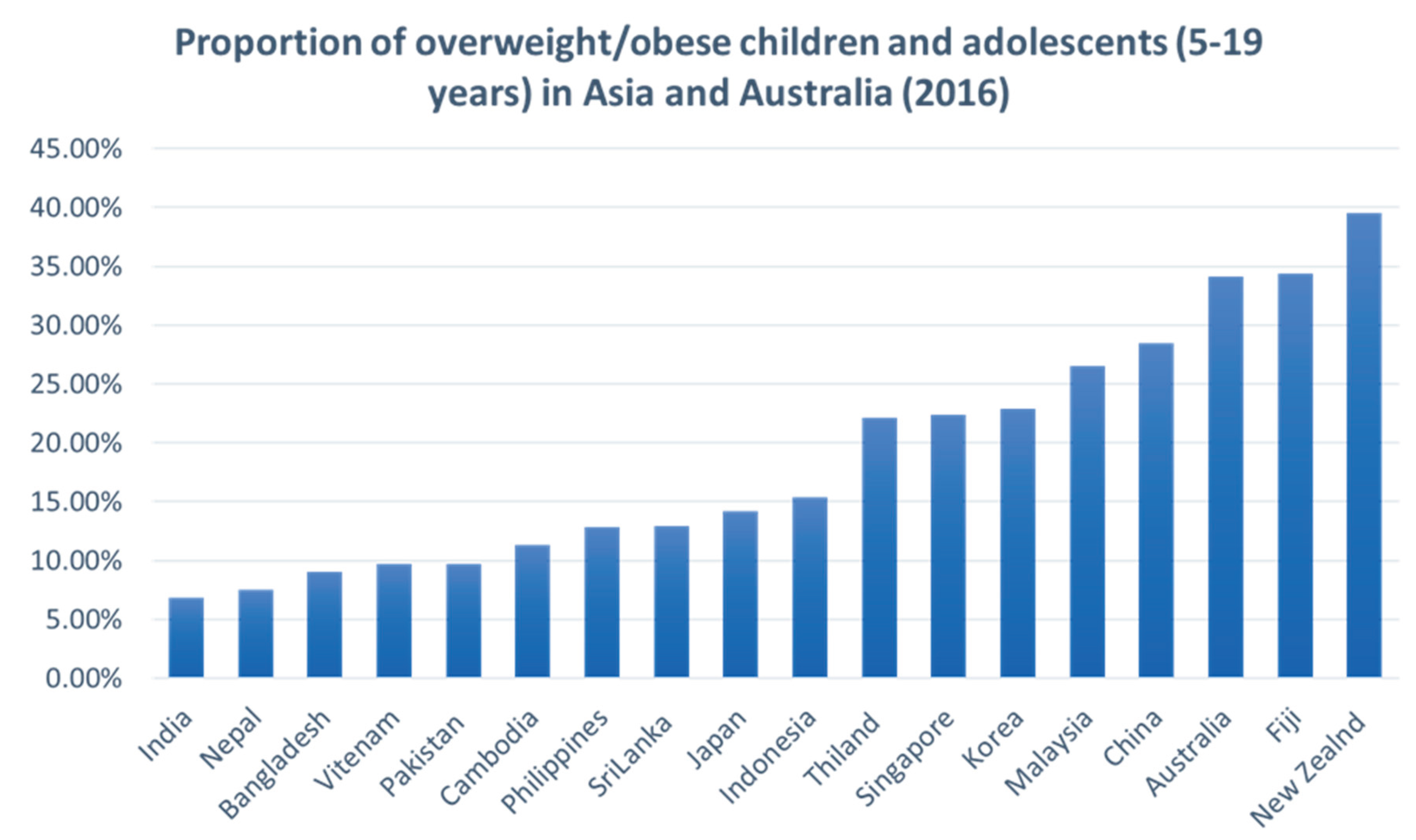

Prevalence

Factors Contributing to Childhood Obesity

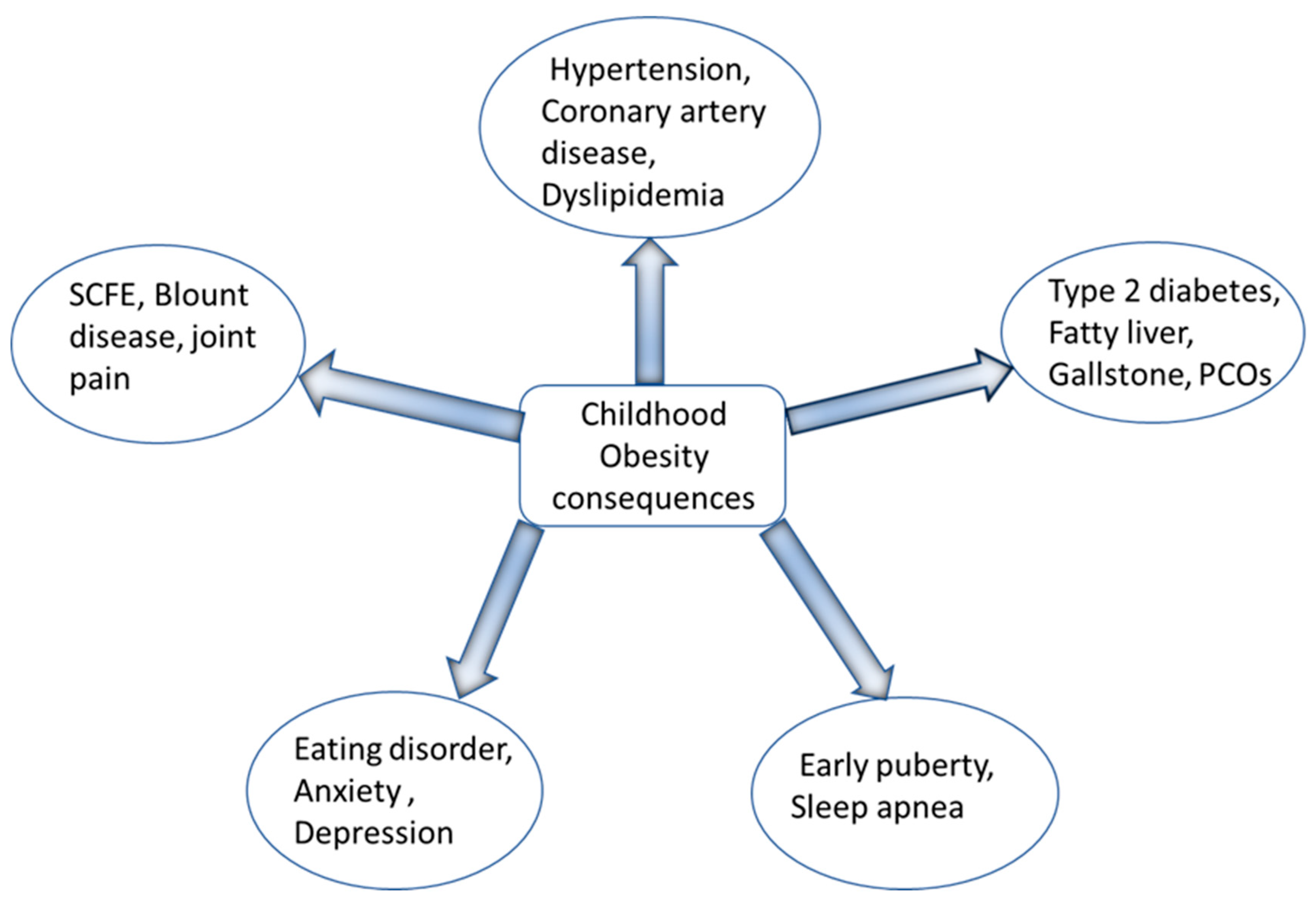

Consequences of Obesity

Preventive Strategies and Management of Childhood Obesity

Conclusions

References

- K. M. Flegal, R. Wei, and C. Ogden, "Weight-for-stature compared with body mass index-for-age growth charts for the United States from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention," Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 761-6, Apr 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Himes and W. H. Dietz, "Guidelines for overweight in adolescent preventive services: recommendations from an expert committee. The Expert Committee on Clinical Guidelines for Overweight in Adolescent Preventive Services," Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 307-16, Feb 1994. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghosh, "Explaining overweight and obesity in children and adolescents of Asian Indian origin: the Calcutta childhood obesity study," Indian J Public Health, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 125-8, Apr-Jun 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Popkin and C. M. Doak, "The obesity epidemic is a worldwide phenomenon," Nutr Rev, vol. 56, no. 4 Pt 1, pp. 106-14, Apr 1998. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B. Sahoo, A. K. Choudhury, N. Y. Sofi, R. Kumar, and A. S. Bhadoria, "Childhood obesity: causes and consequences," J Family Med Prim Care, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 187-92, Apr-Jun 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Nittari, S. Scuri, F. Petrelli, I. Pirillo, N. M. di Luca, and I. Grappasonni, "Fighting obesity in children from European World Health Organization member states. Epidemiological data, medical-social aspects, and prevention programs," Clin Ter, vol. 170, no. 3, pp. e223-e230, May-Jun 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Scuri, F. Petrelli, M. Tesauro, F. Carrozzo, L. Kracmarova, and I. Grappasonni, "Energy drink consumption: a survey in high school students and associated psychological effects," J Prev Med Hyg, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. E75-E79, Mar 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. D. C. Ball, A. Savu, and P. Kaul, "Changes in the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity between 2010 and 2017 in preschoolers: A population-based study," Pediatr Obes, vol. 14, no. 11, p. e12561, Nov 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Rao, E. Kropac, M. T. Do, K. C. Roberts, and G. C. Jayaraman, "Childhood overweight and obesity trends in Canada," Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can, vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 194-8, Sep 2016. Tendances en matiere d'embonpoint et d'obesite chez les enfants au Canada. [CrossRef]

- A. Sanyaolu, C. Okorie, X. Qi, J. Locke, and S. Rehman, "Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in the United States: A Public Health Concern," Glob Pediatr Health, vol. 6, p. 2333794X19891305, 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. World Health, "The double burden of malnutrition: policy brief," World Health Organization, Geneva, 2016 2016, issue CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255413.

- U. W. W. Bank, " joint child malnutrition estimates," 2021 edition interactive dashboard. New York (NY): United Nations Children’s Fund;, report 2021. [Online]. Available: https://data.unicef.org/resources/joint-child-malnutrition-estimates-interactive-dashboard-2021.

- M. Mazidi, M. Banach, A. P. Kengne, Lipid, and G. Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration, "Prevalence of childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Asian countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis," Arch Med Sci, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1185-1203, Oct 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Centers for Disease and Prevention, "CDC grand rounds: childhood obesity in the United States," MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 42-6, Jan 21 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21248681.

- A. Qasim et al., "On the origin of obesity: identifying the biological, environmental and cultural drivers of genetic risk among human populations," Obes Rev, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 121-149, Feb 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Bolin et al., "NMR structure of a minimized human agouti related protein prepared by total chemical synthesis," FEBS Lett, vol. 451, no. 2, pp. 125-31, May 21 1999. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Catalano et al., "Perinatal risk factors for childhood obesity and metabolic dysregulation," Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 1303-13, Nov 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Anderson and K. E. Butcher, "Childhood obesity: trends and potential causes," Future Child, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 19-45, Spring 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Ranadive and C. Vaisse, "Lessons from extreme human obesity: monogenic disorders," Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 733-51, x, Sep 2008,. [CrossRef]

- S. Farooqi et al., "Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor," N Engl J Med, vol. 356, no. 3, pp. 237-47, Jan 18 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Huvenne, B. Dubern, K. Clement, and C. Poitou, "Rare Genetic Forms of Obesity: Clinical Approach and Current Treatments in 2016," Obes Facts, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 158-73, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Kansra, S. Lakkunarajah, and M. S. Jay, "Childhood and Adolescent Obesity: A Review," Front Pediatr, vol. 8, p. 581461, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Geets, M. E. C. Meuwissen, and W. Van Hul, "Clinical, molecular genetics and therapeutic aspects of syndromic obesity," Clin Genet, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 23-40, Jan 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Heianza and L. Qi, "Gene-Diet Interaction and Precision Nutrition in Obesity," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 18, no. 4, Apr 7 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Rask-Andersen, T. Karlsson, W. E. Ek, and A. Johansson, "Gene-environment interaction study for BMI reveals interactions between genetic factors and physical activity, alcohol consumption and socioeconomic status," PLoS Genet, vol. 13, no. 9, p. e1006977, Sep 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Martinez, "Body-weight regulation: causes of obesity," Proc Nutr Soc, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 337-45, Aug 2000. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, P. Li, X. Yang, W. Li, X. Qiu, and S. Zhu, "From genetics and epigenetics to the future of precision treatment for obesity," Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf), vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 266-270, Nov 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, "Epigenetic Mechanisms Link Maternal Diets and Gut Microbiome to Obesity in the Offspring," Front Genet, vol. 9, p. 342, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Reinehr, A. Hinney, G. de Sousa, F. Austrup, J. Hebebrand, and W. Andler, "Definable somatic disorders in overweight children and adolescents," J Pediatr, vol. 150, no. 6, pp. 618-22, 622 e1-5, Jun 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Birch and J. O. Fisher, "Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents," Pediatrics, vol. 101, no. 3 Pt 2, pp. 539-49, Mar 1998. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12224660.

- F. Indrio et al., "Epigenetic Matters: The Link between Early Nutrition, Microbiome, and Long-term Health Development," Front Pediatr, vol. 5, p. 178, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Koletzko et al., "Prevention of Childhood Obesity: A Position Paper of the Global Federation of International Societies of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (FISPGHAN)," J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 702-710, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Nielsen and B. M. Popkin, "Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977-1998," JAMA, vol. 289, no. 4, pp. 450-3, Jan 22-29 2003. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth., J. M. McGinnis, J. A. Gootman, and V. I. Kraak, Food marketing to children and youth : threat or opportunity? Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2006, pp. xx, 516 p.

- R. Benjamin, "Surgeon General's prevention priorities dovetail with health care reform law. Interview by Rebecca Voelker," JAMA, vol. 303, no. 21, pp. 2123-4, Jun 2 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Friedlander, E. K. Larkin, C. L. Rosen, T. M. Palermo, and S. Redline, "Decreased quality of life associated with obesity in school-aged children," Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, vol. 157, no. 12, pp. 1206-11, Dec 2003. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Wu, and S. Yao, "Dose-response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies," Br J Sports Med, vol. 50, no. 20, pp. 1252-1258, Oct 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Lowe, J. B. Morton, and A. C. Reichelt, "Adolescent obesity and dietary decision making-a brain-health perspective," Lancet Child Adolesc Health, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 388-396, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. L. Schiffino et al., "Activation of a lateral hypothalamic-ventral tegmental circuit gates motivation," PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 7, p. e0219522, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Reilly et al., "Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study," BMJ, vol. 330, no. 7504, p. 1357, Jun 11 2005. [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare et al., "The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: a worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action," BMC Med, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 212, Nov 25 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Lissak, "Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study," Environ Res, vol. 164, pp. 149-157, Jul 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Dev, B. A. McBride, B. H. Fiese, B. L. Jones, H. Cho, and T. Behalf Of The Strong Kids Research, "Risk factors for overweight/obesity in preschool children: an ecological approach," Child Obes, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 399-408, Oct 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Vos and J. Welsh, "Childhood obesity: update on predisposing factors and prevention strategies," Curr Gastroenterol Rep, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 280-7, Aug 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Fuller, E. Lehman, S. Hicks, and M. B. Novick, "Bedtime Use of Technology and Associated Sleep Problems in Children," Glob Pediatr Health, vol. 4, p. 2333794X17736972, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Chahal, C. Fung, S. Kuhle, and P. J. Veugelers, "Availability and night-time use of electronic entertainment and communication devices are associated with short sleep duration and obesity among Canadian children," Pediatr Obes, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 42-51, Feb 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Goldschmidt, V. P. Aspen, M. M. Sinton, M. Tanofsky-Kraff, and D. E. Wilfley, "Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in overweight youth," Obesity (Silver Spring), vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 257-64, Feb 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Horsager, E. Faerk, A. N. Gearhardt, M. B. Lauritsen, and S. D. Ostergaard, "Food addiction comorbid to mental disorders in adolescents: a nationwide survey and register-based study," Eat Weight Disord, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 945-959, Apr 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Stabouli, S. Erdine, L. Suurorg, A. Jankauskiene, and E. Lurbe, "Obesity and Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents: The Bidirectional Link," Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 12, Nov 29 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Aguera, M. Lozano-Madrid, N. Mallorqui-Bague, S. Jimenez-Murcia, J. M. Menchon, and F. Fernandez-Aranda, "A review of binge eating disorder and obesity," Neuropsychiatr, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 57-67, Jun 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Puhl, M. S. Himmelstein, and R. L. Pearl, "Weight stigma as a psychosocial contributor to obesity," Am Psychol, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 274-289, Feb-Mar 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. P. Libbey, M. T. Story, D. R. Neumark-Sztainer, and K. N. Boutelle, "Teasing, disordered eating behaviors, and psychological morbidities among overweight adolescents," Obesity (Silver Spring), vol. 16 Suppl 2, pp. S24-9, Nov 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Striegel-Moore, C. G. Fairburn, D. E. Wilfley, K. M. Pike, F. A. Dohm, and H. C. Kraemer, "Toward an understanding of risk factors for binge-eating disorder in black and white women: a community-based case-control study," Psychol Med, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 907-17, Jun 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Warner, A. Wesselink, K. G. Harley, A. Bradman, K. Kogut, and B. Eskenazi, "Prenatal exposure to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and obesity at 9 years of age in the CHAMACOS study cohort," Am J Epidemiol, vol. 179, no. 11, pp. 1312-22, Jun 1 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Whitaker, M. S. Pepe, J. A. Wright, K. D. Seidel, and W. H. Dietz, "Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity," Pediatrics, vol. 101, no. 3, p. E5, Mar 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Jabakhanji, F. Boland, M. Ward, and R. Biesma, "Body Mass Index Changes in Early Childhood," J Pediatr, vol. 202, pp. 106-114, Nov 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Pulgaron, "Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities," Clin Ther, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. A18-32, Jan 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Brara, C. Koebnick, A. H. Porter, and A. Langer-Gould, "Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension and extreme childhood obesity," J Pediatr, vol. 161, no. 4, pp. 602-7, Oct 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Silverstein et al., "Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a statement of the American Diabetes Association," Diabetes Care, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 186-212, Jan 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. Dabelea et al., "Association of Type 1 Diabetes vs Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosed During Childhood and Adolescence With Complications During Teenage Years and Young Adulthood," JAMA, vol. 317, no. 8, pp. 825-835, Feb 28 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Cioana et al., "Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Patients With Pediatric Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis," JAMA Netw Open, vol. 5, no. 2, p. e2147454, Feb 1 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zeitler et al., "ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Type 2 diabetes mellitus in youth," Pediatr Diabetes, vol. 19 Suppl 27, pp. 28-46, Oct 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Brady, "Obesity-Related Hypertension in Children," Front Pediatr, vol. 5, p. 197, 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Bonner, "Hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension," J Cardiovasc Pharmacol, vol. 24 Suppl 2, pp. S39-49, 1994. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7898093.

- E. L. Anderson, L. D. Howe, H. E. Jones, J. P. Higgins, D. A. Lawlor, and A. Fraser, "The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis," PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 10, p. e0140908, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Schwimmer, P. E. Pardee, J. E. Lavine, A. K. Blumkin, and S. Cook, "Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," Circulation, vol. 118, no. 3, pp. 277-83, Jul 15 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Feldstein, P. Charatcharoenwitthaya, S. Treeprasertsuk, J. T. Benson, F. B. Enders, and P. Angulo, "The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years," Gut, vol. 58, no. 11, pp. 1538-44, Nov 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Koebnick et al., "Pediatric obesity and gallstone disease," J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 328-33, Sep 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Jehan et al., "Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Obesity: Implications for Public Health," Sleep Med Disord, vol. 1, no. 4, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29517065.

- Narang and J. L. Mathew, "Childhood obesity and obstructive sleep apnea," J Nutr Metab, vol. 2012, p. 134202, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Eisele, P. Markart, and R. Schulz, "Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence from Human Studies," Oxid Med Cell Longev, vol. 2015, p. 608438. [CrossRef]

- Z. W. Patinkin, R. Feinn, and M. Santos, "Metabolic Consequences of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adolescents with Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis," Child Obes, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 102-110, Apr 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Kaditis, "From obstructive sleep apnea in childhood to cardiovascular disease in adulthood: what is the evidence?," Sleep, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1279-80, Oct 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Magge, E. Goodman, S. C. Armstrong, N. Committee On, E. Section On, and O. Section On, "The Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: Shifting the Focus to Cardiometabolic Risk Factor Clustering," Pediatrics, vol. 140, no. 2, Aug 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Weiss et al., "Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents," N Engl J Med, vol. 350, no. 23, pp. 2362-74, Jun 3 2004. [CrossRef]

- E. Lang, "Obesity, Nutrition, and Asthma in Children," Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 64-75, Jun 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Sadeeqa, T. Mustafa, and S. Latif, "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome-Related Depression in Adolescent Girls: A Review," J Pharm Bioallied Sci, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 55-59, Apr-Jun 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Chung, "Growth and Puberty in Obese Children and Implications of Body Composition," J Obes Metab Syndr, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 243-250, Dec 30 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Soliman, M. Yasin, and A. Kassem, "Leptin in pediatrics: A hormone from adipocyte that wheels several functions in children," Indian J Endocrinol Metab, vol. 16, no. Suppl 3, pp. S577-87, Dec 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Burt Solorzano and C. R. McCartney, "Obesity and the pubertal transition in girls and boys," Reproduction, vol. 140, no. 3, pp. 399-410, Sep 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Lee et al., "Timing of Puberty in Overweight Versus Obese Boys," Pediatrics, vol. 137, no. 2, p. e20150164, Feb 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Franks, "Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents," Int J Obes (Lond), vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 1035-41, Jul 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Ong et al., "Infancy weight gain predicts childhood body fat and age at menarche in girls," J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 94, no. 5, pp. 1527-32, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Stovitz, E. W. Demerath, P. J. Hannan, L. A. Lytle, and J. H. Himes, "Growing into obesity: patterns of height growth in those who become normal weight, overweight, or obese as young adults," Am J Hum Biol, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 635-41, Sep-Oct 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Schwimmer, T. M. Burwinkle, and J. W. Varni, "Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents," JAMA, vol. 289, no. 14, pp. 1813-9, Apr 9 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Budd and L. L. Hayman, "Addressing the childhood obesity crisis: a call to action," MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 111-8, quiz 119-20, Mar-Apr 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. Bacchini et al., "Bullying and Victimization in Overweight and Obese Outpatient Children and Adolescents: An Italian Multicentric Study," PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 11, p. e0142715, 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. Niehoff, "Childhood Obesity: A Call to Action," Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 17-23, 2009/03/01 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Rankin et al., "Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention," Adolesc Health Med Ther, vol. 7, pp. 125-146. [CrossRef]

- D. Ruiz, M. L. Zuelch, S. M. Dimitratos, and R. E. Scherr, "Adolescent Obesity: Diet Quality, Psychosocial Health, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors," Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec 23 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Hayes, E. E. Fitzsimmons-Craft, A. M. Karam, J. Jakubiak, M. L. Brown, and D. E. Wilfley, "Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors in Youth with Overweight and Obesity: Implications for Treatment," Curr Obes Rep, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 235-246, Sep 2018. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, A. Llewellyn, C. G. Owen, and N. Woolacott, "Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis," Obes Rev, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 95-107, Feb 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pont, R. Puhl, S. R. Cook, W. Slusser, O. Section On, and S. Obesity, "Stigma Experienced by Children and Adolescents With Obesity," Pediatrics, vol. 140, no. 6, Dec 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Puhl and Y. Suh, "Health Consequences of Weight Stigma: Implications for Obesity Prevention and Treatment," Curr Obes Rep, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 182-90, Jun 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Carcone, A. J. Jacques-Tiura, K. E. Brogan Hartlieb, T. Albrecht, and T. Martin, "Effective Patient-Provider Communication in Pediatric Obesity," Pediatr Clin North Am, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 525-38, Jun 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Brown, E. E. Halvorson, G. M. Cohen, S. Lazorick, and J. A. Skelton, "Addressing Childhood Obesity: Opportunities for Prevention," Pediatr Clin North Am, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 1241-61, Oct 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Katzmarzyk et al., "An evolving scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity," Int J Obes (Lond), vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 887-905, Jul 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. F. Skjakodegard et al., "Study Protocol: A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of family-based behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity-The FABO-study," BMC Public Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 1106, Oct 21 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. Singhal, A. C. Sella, and S. Malhotra, "Pharmacotherapy in pediatric obesity: current evidence and landscape," Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 55-63, Feb 1 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Woodard, L. Louque, and D. S. Hsia, "Medications for the treatment of obesity in adolescents," Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab, vol. 11, p. 2042018820918789, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Maahs et al., "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss in adolescents," Endocr Pract, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 18-28, Jan-Feb 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Torgerson, J. Hauptman, M. N. Boldrin, and L. Sjostrom, "XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients," Diabetes Care, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 155-61, Jan 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Ryder, A. Kaizer, K. D. Rudser, A. Gross, A. S. Kelly, and C. K. Fox, "Effect of phentermine on weight reduction in a pediatric weight management clinic," Int J Obes (Lond), vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 90-93, Jan 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Srivastava and C. M. Apovian, "Current pharmacotherapy for obesity," Nat Rev Endocrinol, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 12-24, Jan 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Wolfgram, A. L. Carrel, and D. B. Allen, "Long-term effects of recombinant human growth hormone therapy in children with Prader-Willi syndrome," Curr Opin Pediatr, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 509-14, Aug 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Lustig et al., "Octreotide therapy of pediatric hypothalamic obesity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial," J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 88, no. 6, pp. 2586-92, Jun 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. Srivastava, V. O'Hara, and N. Browne, "Use of Lisdexamfetamine to Treat Obesity in an Adolescent with Severe Obesity and Binge Eating," Children (Basel), vol. 6, no. 2, Feb 4 2019. [CrossRef]

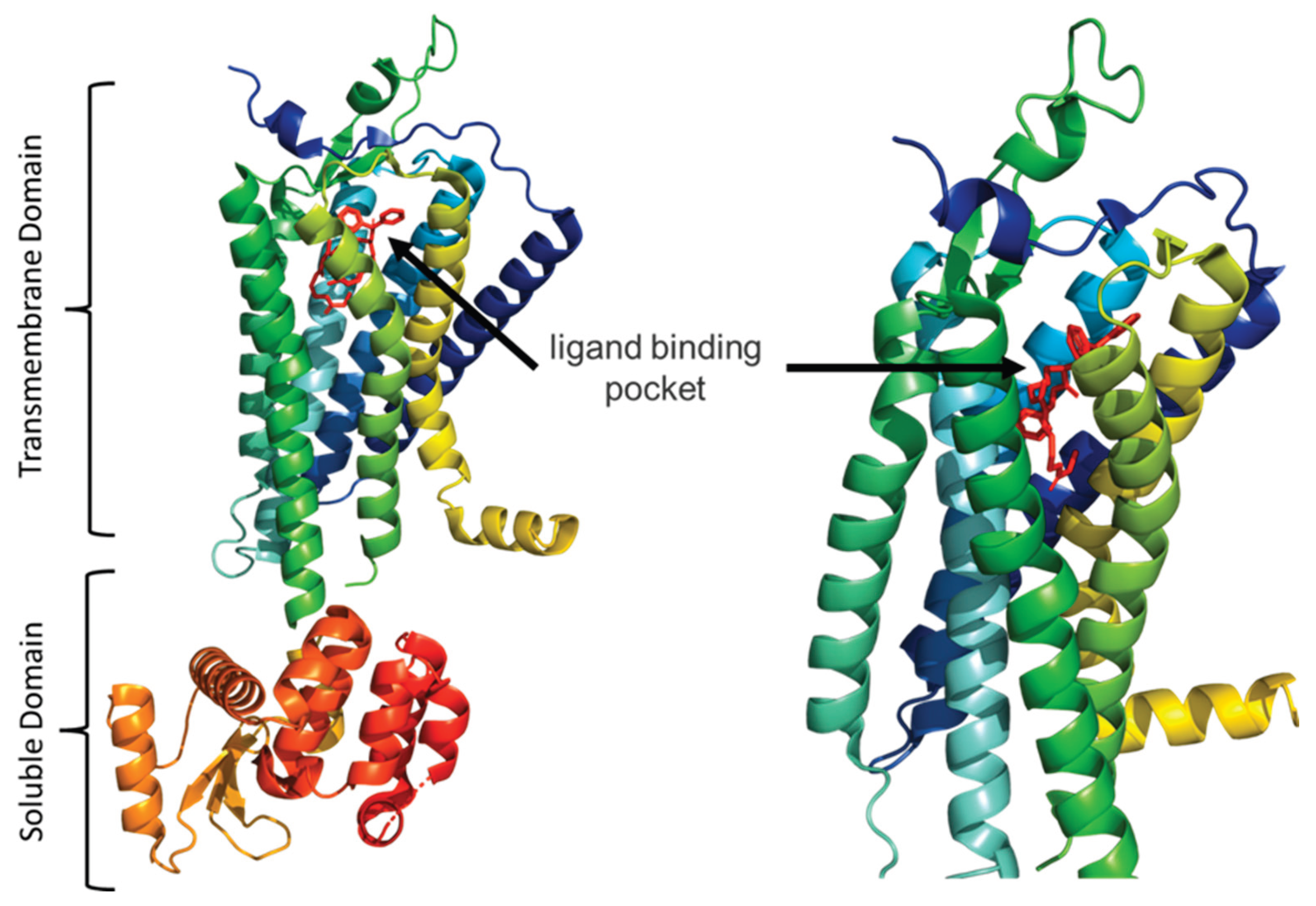

- C. Park et al., "Structural basis of neuropeptide Y signaling through Y1 receptor," Nat Commun, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 853, Feb 14 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Weiss, A. Mooney, and J. P. Gonzalvo, "Bariatric Surgery: The Future of Obesity Management in Adolescents," Adv Pediatr, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 269-283, Aug 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lamoshi, A. Chernoguz, C. M. Harmon, and M. Helmrath, "Complications of bariatric surgery in adolescents," Semin Pediatr Surg, vol. 29, no. 1, p. 150888, Feb 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).