1. Introduction

Healthcare providers around the globe face the daunting task of improving patient outcomes while keeping costs manageable [

1]. Advanced analytical technology, driven by the digital revolution, holds promise for enhancing patient care and data-driven decision-making, which promotes a culture of continuous improvement within healthcare organizations [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Industries such as manufacturing, finance, and logistics have shown that the successful implementation of workflow automation is critical in optimizing operations [

6]. Automation techniques can be tailored to address the unique needs and complexities of the healthcare industry, especially when existing methods rely on manual data analysis [

1,

4,

6,

7,

8]. This customization can significantly enhance efficiency and accuracy in handling healthcare data.

Trauma triage systems play a crucial role in trauma care in the Emergency Department (ED) [

9,

10,

11]. Research has consistently shown that appropriate trauma triage improves patient care and outcomes, enhances ED efficiency, and reduces operating costs [

12,

13]. Critical resources like blood products, hospital staff, and inpatient beds are limited, making it a complex challenge to balance the need for rapid and effective trauma care with the scarcity of available resources [

14,

15]. Trauma team activations (TTA) at the anticipated level of need are essential to ensuring that trauma patients with severe injuries receive timely and adequate care, even in the face of limited resources [

11,

16,

17,

18]. In the United States, trauma centers have established TTA protocols to respond promptly to patients with varying degrees of injuries [

19]. These protocols rely on criteria of physiologic findings, mechanism of injury, and anatomic damage to approximate injury severity, morbidity, and mortality risk [

17,

18,

20].

Though structured, TTA criteria do not consistently anticipate every patient’s needs, often leading to inappropriate triage decisions [

10,

11,

21,

22,

23]. Overtriage occurs when patients are triaged to a higher level of care than their injury severity warrants, leading to increased healthcare costs [

22,

24,

25]. In contrast, undertriage occurs when patients with significant injury burdens do not receive the full or appropriate level of TTA, which can lead to adverse outcomes by preventing or delaying the delivery of definitive care [

14,

19,

24,

26]. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) aims for triage error rates of less than 5% for undertriage and between 25% and 50% for overtriage [

15,

23,

26]. Accurate reporting of overtriage and undertriage rates in trauma activations is imperative for optimizing trauma resource utilization and improving trauma care [

23,

24,

26].

The Standardized Triage Assessment Tool (STAT) is used to evaluate the appropriateness of trauma triage and TTA [

14]. It evaluates whether a trauma patient was misclassified in terms of injury severity using the Cribari Matrix Method (CMM) and determines if the patient required major trauma intervention based on Need for Trauma Intervention (NFTI) criteria [

13,

14,

20,

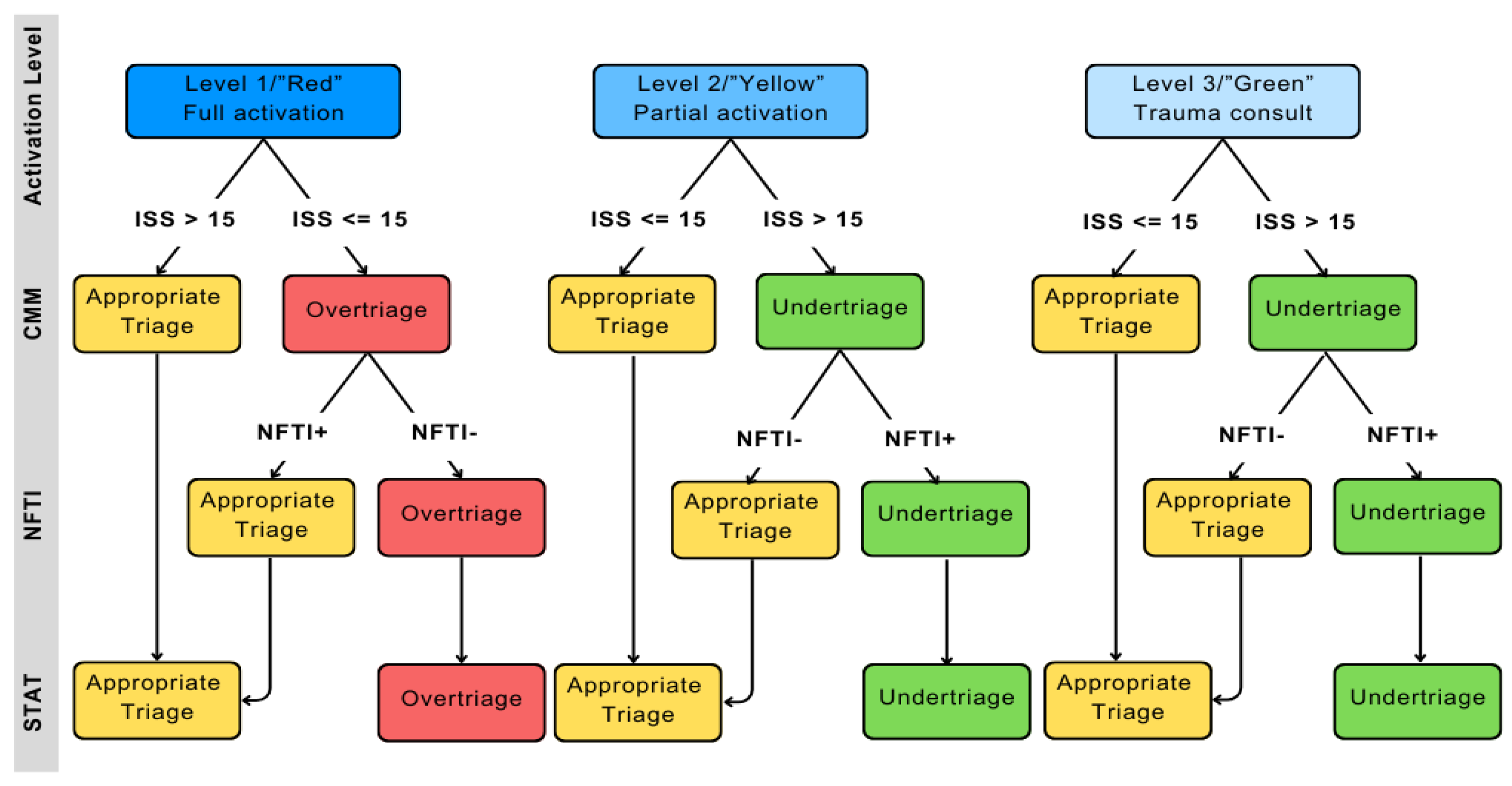

27]. CMM calculates the overtriage and undertriage using the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and the level of TTA, while the NFTI criteria assess resource utilization and level of TTA, as outlined in

Figure 1 [

12,

13,

25,

28].

The STAT is a combination of the CMM and the NFTI tool [

14,

28]. CMM calculates the overtriage and undertriage using the ISS and the level of TTA—in undertriage, a patient is severely injured with an ISS greater than 15 but with a TTA other than full; in overtriage, a patient with a minor to moderate ISS (less than or equal to 15) receives operating room within 90 minutes; (3) discharge from the ED to interventional radiology; (4) discharge from the highest level of TTA [

12,

28,

29]. The NFTI criteria assess resource utilization and trauma-related interventions; a positive NFTI (NFTI+) requires at least one of the following: (1) transfusion of packed red blood cells within four hours of ED arrival; (2) discharge from the ED to the the ED to the intensive care unit (ICU) with ICU length of stay of three or more days; (5) use of non-procedural mechanical ventilation within 72 hours; and, (6) mortality within 60 hours of arrival [

20,

30,

31,

32].

Using insights from successful workflow automation in other industries, the objective of this project was to develop an automated, web-based tool for calculating overtriage and undertriage rates of TTA using the STAT [

6,

33,

34]. To our knowledge, this is the first tool specifically designed for this purpose: automating the calculation of triage accuracy and optimizing trauma care decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

We collected de-identified data sets of 1,578 TTAs from the trauma registry of a single ACS COT-verified Level 1 Trauma Center from November 1, 2022

, to October 31, 2023, inclusive. At this institution, Level 1 or ‘Red’ traumas require a full trauma team activation, which includes immediate mobilization of both the ED and Trauma Surgery teams, comprising the Trauma Surgery attending and resident teams, as well as the ED attending and resident teams. Level 2 or ‘Yellow’ traumas require activation of the ED team and the resident Trauma Surgery team, but do not necessitate immediate involvement of the Trauma Surgery attending. Level 3 or ‘Green’ traumas are managed solely by the ED team, who may consult the Trauma Surgery team if they deem it necessary. Trauma overtriage and undertriage for each TTA were determined according to the criteria of the CMM and NFTI used in the STAT, as shown in

Figure 1. All statistical analyses were done using Python version 2022.3.1. The web tool was designed using the website development programming languages Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS).

2.2. Application Prototyping and Development

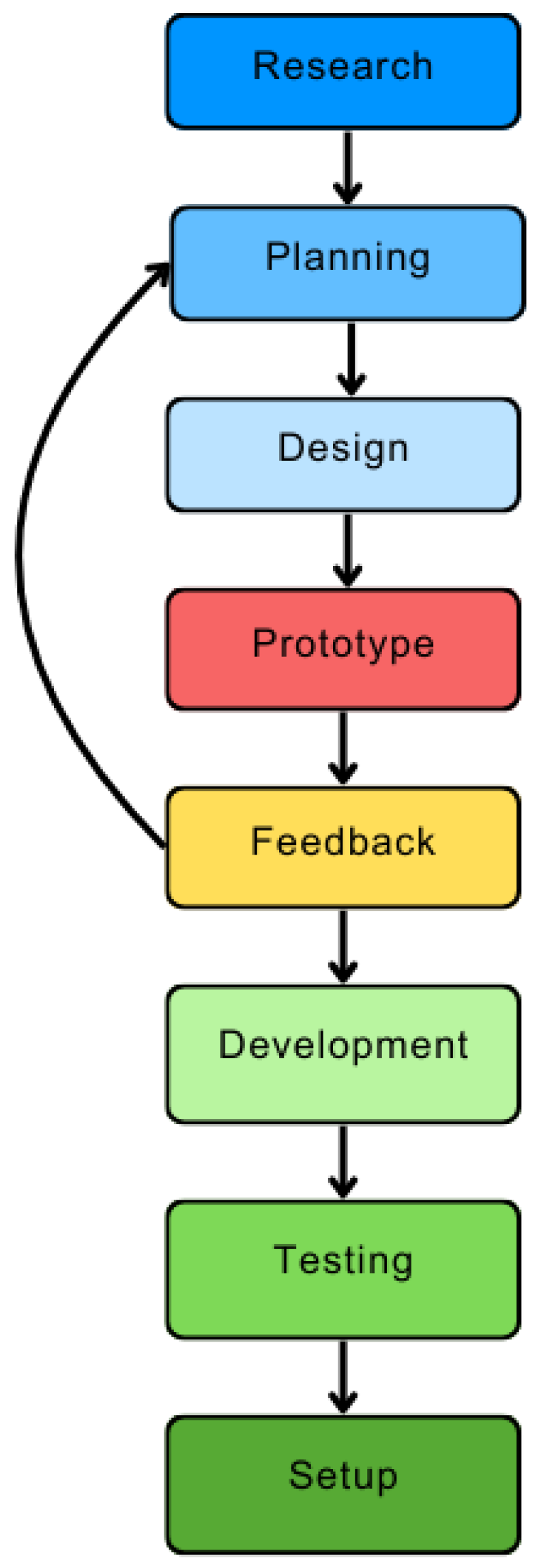

Figure 2 illustrates the prototyping methodology, which involves an iterative process of planning, designing, building, testing, and debugging the application [

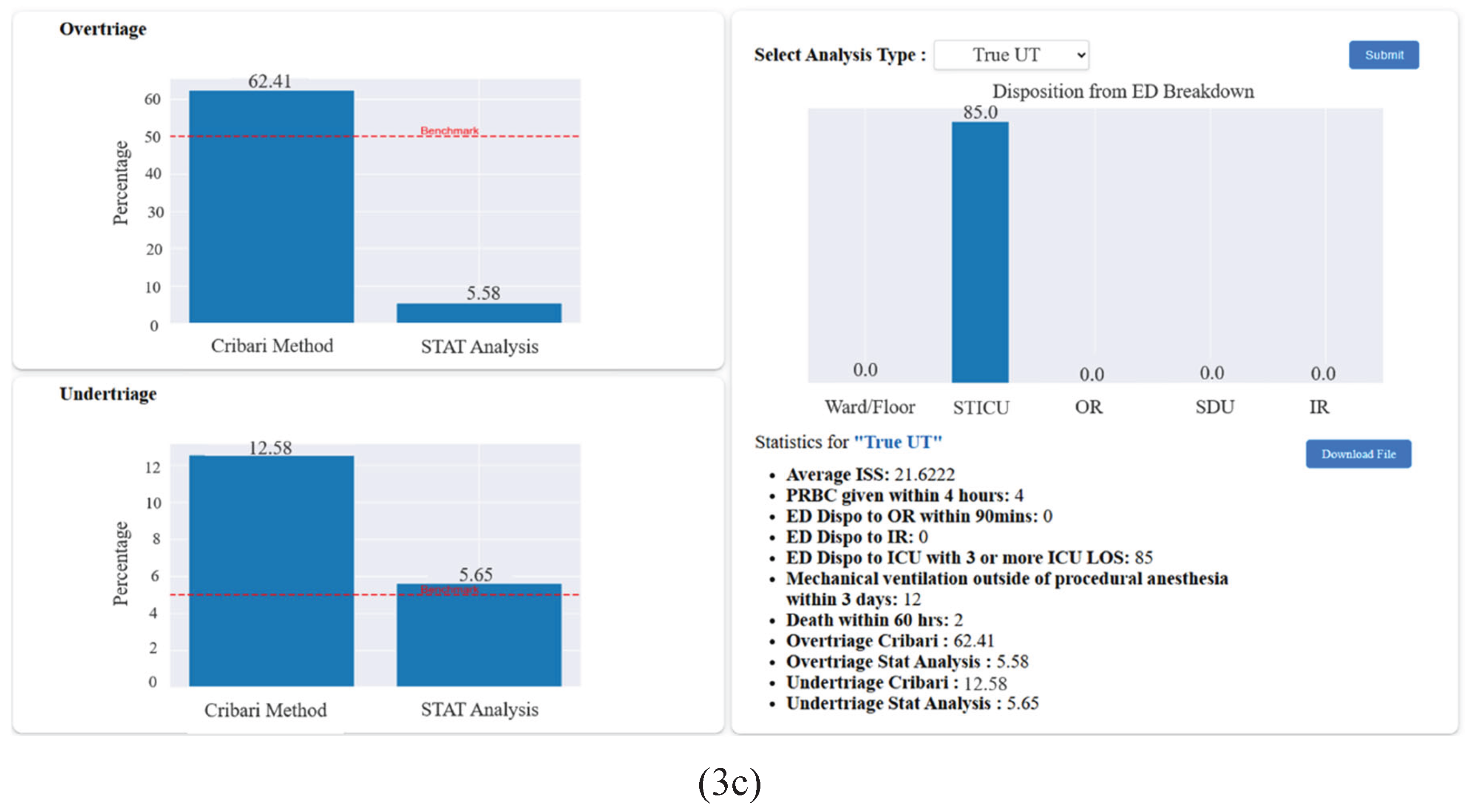

35]. During the development stage, a graphical user interface (GUI) was constructed, allowing end-users to interact with the application and perform relevant calculations. The application was designed to receive TTA data through a data upload feature that supports the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet format. The application was encrypted and secured behind a login requiring authorized credentials for access. Screenshots of the final application are shown in

Figure 3.

2.3. Application Performance Testing

Preliminary testing of the application was performed by testing the tool on a mock data set of 15 TTAs and comparing the results with the manual data analysis process conducted by the programmer (author AA). Intermediate testing used a limited dataset of 104 de-identified TTAs spanning a one-month subset of the TTAs collected from the hospital. Final testing was conducted on the completed TTA dataset collected from the hospital, which included 1,578 de-identified TTAs over one year. For both datasets, the Accuracy and Process Efficiency of the automated and manual analysis methods were evaluated to assess the tool’s performance relative to the manual process. Accuracy was determined by comparing the triage classifications (appropriate, overtriage, or undertriage) from the manual calculations with those from the automated tool. It was anticipated that, once provided with complete data in Excel format and correctly programmed to apply the STAT method, the tool would achieve 100% accuracy. Process Efficiency Improvement was calculated as:

2.4. Application Evaluation

The application and its functionality were presented to a focus group of trauma providers from a level 1 trauma center. The providers were first trained on performing manual calculations using the STAT method, followed by instructions on how to use our tool with a sample dataset. After, the participants were asked to complete an evaluation survey using a 5-point Likert scale, evaluating the tool’s performance, and their experience with and perception of the tool. Mean ratings for each question, on a scale of 1 to 5, were calculated and reported for all participants.

3. Results

3.1. Performance Testing

As expected, the automated data analysis process had 100% accuracy in determining overtriage and undertriage for the mock and actual datasets. The time to complete the analysis of the full dataset was 26 minutes and 19 seconds (1579 seconds) using the manual process, whereas it took 23 seconds using our automated tool (

Table 1). The mean process efficiency of the automated data analysis process was 98.0%. This represents a significant time-saving advantage.

3.2. Survey Findings

Ten participants completed the online survey to evaluate the tool: two Trauma Program Directors, two Performance Improvement/Clinical Data Analysts, a Trauma Medical Director, an Associate Trauma Medical Director, a Trauma Surgeon, a Trauma Liaison, a Trauma Research Associate, and a consultant. The majority of participants had a significant amount of experience in caring for trauma patients and in trauma center leadership roles: six had over six years of experience in trauma center leadership, three had between three and six years of experience, and one had one to two years of experience.

Table 2 shows the results of the evaluation survey. All participants said the application was easy to use, giving the program an average rating of 4.6. They all thought the application significantly reduced data analysis time, with an average rating of 4.9. They also all agreed that the application assisted in identifying mistreated trauma patients during the performance improvement process (mean rating of 4.7) and noted that the tool effectively automated both overtriage and undertriage analyses, each receiving a mean rating of 4.8. The reliability of the tool was deemed to be high, with an average rating of 4.6. All participants indicated they would consider incorporating this tool into their institution/workflow.

3.3. Open-Ended Participant Feedback

Participants expressed enthusiasm about the tool’s ability to enhance workflow efficiency, particularly by reducing the time required for data analysis. One participant highlighted its potential value for trauma research. Several others noted that the tool holds great promise for future advancements in data analysis technology for trauma center leadership. A suggested improvement for future development was to add a feature for identifying outliers in the overtriage and undertriage of TTA.

4. Discussion

We outlined the development and evaluation of an automated, web-based data analysis tool that calculates the mistriage rates of a dataset of TTAs at a trauma center. Findings indicated that our tool represents an accurate and highly time-efficient method for analyzing mistriage. Feedback from experienced trauma providers was overwhelmingly positive, highlighting the tool's perceived efficiency and reliability in streamlining processes. Overall, participants felt the application was easy to use, accurate in calculating overtriage and undertriage rates, and beneficial for performance improvement activities, with all respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with the evaluated metrics.

From a quality improvement perspective, having a reliable tool that can accurately report on rates and trends of overtriage and undertriage of trauma activations while reducing data analysis processing time allows trauma centers to focus on critical aspects of utilization management [

16,

23,

34]. This includes developing actionable plans to enhance the quality of patient care delivery and improving overall trauma center operations.

Limitations

One notable limitation of the project was that there was limited end-user interaction with the tool, as the institution had high-level security and permission requirements for any application to be installed on local computers. Additionally, the evaluation of the data analysis tool was conducted with a small sample size of participants, which may affect the generalizability of the results. To enhance the reliability of our evaluation, it is recommended to conduct a larger-scale participant study to minimize potential biases and improve the robustness of the findings.

Future Considerations

Further development and refinement of our tool will be necessary before broader institutional and external deployment. Future versions of the data analysis tool will include features for summarizing trends in overtriage and undertriage and identifying outliers, as suggested. Additional functionalities will incorporate an export feature for downloading detailed overtriage and undertriage determinations for each analyzed case and tools for handling incomplete data. Ultimately, we plan to provide access to this tool to all trauma providers, starting with our institution and eventually extending to others. This will involve the engagement of the information technology infrastructure and organizational leadership teams at our trauma center to ensure adequate security permissions and approvals before deployment. Successful deployment will enable the tool to be utilized for quality improvement initiatives and research projects, enhancing its impact on trauma care and outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- AA, and BS; Resources- MC, KT, CG, PN, SB, SP, NDB; Formal analysis- AA, BS and MA; Investigation- AA, BS, JD, JM, ZS; Writing—original draft preparation- AA and BS; writing—review and editing- BS, GA, SA and JW; supervision- BS; project administration- BS

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Statement

This retrospective study was approved by the IRB at Elmhurst Hospital Center (EHC) on July 5, 2024, with IRB number 24-12-103-05G(HHC)

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to Aya Nageh Mohamed, who holds a Bachelor of Science in Communication and Information Engineering from the University of Science and Technology in Zewail City, Egypt, for her contribution to the development of this application.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS COT |

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma |

| AT |

Appropriate Triage |

| CMM |

Cribari Matrix Method |

| CSS |

Cascading Style Sheets |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| GUI |

Graphical User Interface |

| HTML |

Hypertext Markup Language |

| IR |

Interventional Radiology |

| ISS |

Injury Severity Score |

| NFTI |

Need for Trauma Intervention |

| OR |

Operating Room |

| OT |

Overtriaged |

| SDU |

Step-Down Unit |

| STAT |

Standardized Triage Assessment Tool |

| STICU |

Surgical Trauma Intensive Care Unit |

| TTA |

Trauma Team Activation |

| UT |

Undertriage |

References

- Gopal, G.; Suter-Crazzolara, C.; Toldo, L.; Eberhardt, W. Digital Transformation in Healthcare – Architectures of Present and Future Information Technologies. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.. CCLM 2019, 57, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazmomi, N.; Ilmudeen, A.; Qaffas, A.A. The Impact of Business Analytics Capability on Data-Driven Culture and Exploration: Achieving a Competitive Advantage. Benchmarking 2022, 29, 1264–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M. Does Data Analytics Use Improve Firm Decision-Making Quality? The Role of Knowledge Sharing and Data Analytics Competency. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 120, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.A. Healthcare’s Future: Strategic Investment in Technology. Front. Health Serv. Manage. 2018, 34, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilty, D.M.; Armstrong, C.M.; Smout, S.A.; Crawford, A.; Maheu, M.M.; Drude, K.P.; Chan, S.; Yellowlees, P.M.; Krupinski, E.A. Findings and Guidelines on Provider Technology, Fatigue, and Well-Being: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayas-Cabán, T.; Haque, S.N.; Kemper, N. Identifying Opportunities for Workflow Automation in Health Care: Lessons Learned from Other Industries. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, B.; Restuccia, J. Process Improvement and Information Technology: The Keys to Health Care Transformation. J. Ambulatory Care Manage. 2023, 46, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ramón Fernández, A.; Ruiz Fernández, D.; Sabuco García, Y. Business Process Management for Optimizing Clinical Processes: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Informatics J. 2020, 26, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Carlos, G.; Nassar, A.K.; Knowlton, L.M.; Spain, D.A. The Impact of Trauma Systems on Patient Outcomes. Curr. Probl. Surg.. 2021, 58, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, A.; Strömmer, L.; Schandl, A.; Östlund, A. A Criteria-Directed Protocol for in-Hospital Triage of Trauma Patients. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R.K.; Arthurs, Z.M.; Cuadrado, D.G.; Casey, L.E.; Beekley, A.C.; Martin, M.J. Trauma Team Activation: Simplified Criteria Safely Reduces Overtriage. Am. J. Surg. 2007, 193, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, F.; Holmberg, L.; Eklöf, H.; Björck, M.; Juhlin, C.; Mani, K. Better Compliance with Triage Criteria in Trauma Would Reduce Costs with Maintained Patient Safety. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, M.E.; Boremski, P.A.; Collier, B.R.; Tegge, A.N.; Gillen, J.R. Impact of Nonphysician, Technology-Guided Alert Level Selection on Rates of Appropriate Trauma Triage in the United States: A before and after Study. J. Trauma Inj. 2023, 36, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roden-Foreman, J.W.; Rapier, N.; Yelverton, L.; Foreman, M. Avoiding Cribari Gridlock: The Standardized Triage Assessment Tool Improves the Accuracy of the Cribari Matrix Method in Identifying Potential Overtriage and Undertriage. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient; American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma, 2014.

- Verhoeff, K.; Saybel, R.; Fawcett, V.; Tsang, B.; Mathura, P.; Widder, S. A Quality-Improvement Approach to Effective Trauma Team Activation. Can. J. Surg. 2019, 62, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seegert, S.; Redfern, R.E.; Chapman, B.; Benson, D. Efforts to Improve Appropriate Trauma Activation for Patients Transferred to A Level 1 Trauma Center from Outside Hospitals. Am. Surg. 2020, 86, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waydhas, C.; Heiko, T.; Hardcastle, T.C.; Jensen, K.O.; Abdelmotaleb Khaled, T.Y.; George, A.S.; Markus, B.; Nehat, B.; Christos, B.; Becker, L.; et al. Survey on Worldwide Trauma Team Activation Requirement. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 47, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient 2022 Standards; American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma, 2022.

- Gabriel, B.; Kimberly, G.; Siddhartha, N.; Jami, Z.; Thomas, S.; Russell, D. Need for Trauma Intervention and Improving Under-Triaging in Geriatric Trauma Patients: Under-Triaged or Misclassified. Int. J. Crit. Care Emerg. Med. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Rogers, F.B.; Schwab, C.W. ; al, et Increased Mortality with Undertriaged Patients in a Mature Trauma Center with an Aggressive Trauma Team Activation System. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2013, 39, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawhan, R.R.; McVay, D.P.; Casey, L.; Spears, T.; Steele, S.R.; Martin, M.J. A Simplified Trauma Triage System Safely Reduces Overtriage and Improves Provider Satisfaction: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Surg. 2015, 209, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonko, D.P.; O’Neill, D.C.; Dennis, B.M.; Smith, M.; Gray, J.; Guillamondegui, O.D. Trauma Quality Improvement: Reducing Triage Errors by Automating the Level Assignment Process. J. Surg. Educ. 2018, 75, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.W.; Dirks, R.C.; Sue, L.P.; Kaups, K.L. Attempting to Validate the Overtriage/Undertriage Matrix at a Level I Trauma Center. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 83, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abback, P.; Brouns, K.; Moyer, J.-D.; Holleville, M.; Hego, C.; Jeantrelle, C.; Bout, H.; Rennuit, I.; Foucrier, A.; Codorniu, A.; et al. ISS Is Not an Appropriate Tool to Estimate Overtriage. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 48, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, E.; Cuevas-Østrem, M.; Gram-Knutsen, C.; Uleberg, O. Undertriage in Trauma: An Ignored Quality Indicator? Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med.. 2020, 28, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.S.; Davis, N.J.; Koestner, A.; Napolitano, L.M.; Hemmila, M.R.; Tignanelli, C.J. Redefining the Trauma Triage Matrix: The Role of Emergent Interventions. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 251, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden-Foreman, J.W.; Rapier, N.R.; Foreman, M.L.; Cribari, C.; Parsons, M.; Zagel, A.L.; Cull, J.; Coniglio, R.A.; McGraw, C.; Blackmore, A.R.; et al. Avoiding Cribari Gridlock 2: The Standardized Triage Assessment Tool Outperforms the Cribari Matrix Method in 38 Adult and Pediatric Trauma Centers. Inj. Int. J. Care Inj. 2021, 52, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waydhas, C.; Bieler, D.; Hamsen, U.; Baacke, M.; Lefering, R. ISS Alone, Is Not Sufficient to Correctly Assign Patients Post Hoc to Trauma Team Requirement. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2020, 48, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden-Foreman, J.W.; Rapier, N.R.; Yelverton, L.; Foreman, M.L. Asking a Better Question: Development and Evaluation of the Need for Trauma Intervention (NFTI) Metric as a Novel Indicator of Major Trauma. J. Trauma Nurs. 2017, 24, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, N.; Phillips, R.; Rodenburg, C.; Meier, M.; Shirek, G.; Recicar, J.; Moulton, S.; Bensard, D. Combining Cribari Matrix and Need For Trauma Intervention (NFTI) to Accurately Assess Undertriage in Pediatric Trauma. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 56, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden-Foreman, J.W.; Rapier, N.R.; Foreman, M.L.; Zagel, A.L.; Sexton, K.W.; Beck, W.C.; McGraw, C.; Coniglio, R.A.; Blackmore, A.R.; Holzmacher, J.; et al. Rethinking the Definition of Major Trauma: The Need for Trauma Intervention Outperforms Injury Severity Score and Revised Trauma Score in 38 Adult and Pediatric Trauma Centers. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, L.B.; Bassi, L.C.; Caldas, L.P.; Sarantopoulos, A.; Zeferino, E.B.B.; Minatogawa, V.; Gasparino, R.C. Lean Healthcare Tools for Processes Evaluation: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacEachern, L.; Ginsburg, L.R.; Hoben, M.; Doupe, M.; Wagg, A.; Knopp-Sihota, J.A.; Cranley, L.; Song, Y.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Berta, W. Developing a Tool to Measure Enactment of Complex Quality Improvement Interventions in Healthcare. BMJ Open Qual. 2023, 12, e002027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soobia, S.; Humayun, M.; Naqvi, S.M.; Zaman, N. Analysis of Software Development Methodologies. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2019, 8, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).