1. Introduction

Clinical data are heterogeneous in real-world healthcare settings. Some patients, particularly those with complex comorbidities, undergo frequent laboratory evaluations that produce an abundance of data [

1]. Other patients who are perceived as clinically stable often have sparser data available, thus raising concerns about whether machine learning models can accurately predict adverse outcomes under such incomplete circumstances. Traditionally, missing data have been viewed as problematic because missingness can lead to biases or imputed approximations [

2,

3]. However, previous studies have introduced the notion of “informative presence,” which suggests that the absence of laboratory tests is not random; instead, this absence signals that specific tests were not performed because no abnormality was suspected [

4]. The VitalCare–Major Adverse Event Score (VC-MAES), which is an artificial intelligence (AI)-based early warning system, leverages this concept by conservatively imputing missing values by assuming that the unmeasured parameters were likely within normal ranges.

Our recent study demonstrated that artificially imputing these missing values with approximate estimates reduced the performance of the VC-MAES compared to that achieved by using the system’s default normal value replacement, suggesting that missing healthcare data can have intrinsic meaning and reflect the decision-making process of clinicians [

5]. Furthermore, this study also demonstrated the following implicit clinical rationale: if no concern exists, then further testing may not be required. To elucidate how baseline severity intersects with these patterns of missingness, we categorized inpatients using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) to determine whether data quantity alone drives the predictive performance and whether ordering (or forgoing) laboratory tests plays a critical role in predicting outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective analysis was performed at Presbyterian Medical Center in the Republic of Korea. Adult patients (19 years or older) admitted to general wards between December 2022 and May 2024 were included if at least one valid measurement of five key vital signs (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature) had been performed. Patients who were directly transferred from the emergency department or operating room to an intensive care unit were excluded because they were considered planned intensive care unit admissions. Baseline comorbidities were assessed using the CCI. Patients with a CCI greater than 3 were classified as having high severity, and those with a CCI of 3 or less were classified as having moderate or low severity [

6].

Clinical endpoints included unplanned intensive care unit transfers, cardiac arrest, or death during hospitalization. The VC-MAES, which is a deep learning-based model, was used to predict these events up to 6 hours in advance by incorporating time series of available vital signs, age, and laboratory test results (total bilirubin, lactate, creatinine, platelets, pH, sodium, potassium, hematocrit, white blood cell count, bicarbonate, and C-reactive protein). Missing test results were handled via the last observation carried forward method, with default normal values assigned if prior measurements were not available. The model performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve.

Demographic characteristics and the proportions of missing laboratory results were compared between groups classified by the CCI. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using either the independent t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the distribution of the data. Differences in proportions of missingness were assessed using a two-sided z-test for independent proportions with continuity correction, based on the score method. A two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

During this study, 24,359 hospitalizations occurred; specifically, 12,139 patients in the high severity group (CCI >3) and 12,220 patients in the moderate/low severity group (CCI ≤3) were hospitalized. Patients with high severity underwent more laboratory investigations, resulting in fewer missing values and a higher rate of unplanned intensive care unit transfer, cardiac arrest, or death (4.8%), consistent with their high risk of adverse outcomes at baseline. Conversely, patients in the moderate/low severity group underwent fewer laboratory tests and, consequently, exhibited higher missingness rates; however, they experienced significantly fewer adverse events overall (1.0%).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic characteristics, vital signs, and differences in laboratory test missingness of the high severity and moderate/low severity groups.

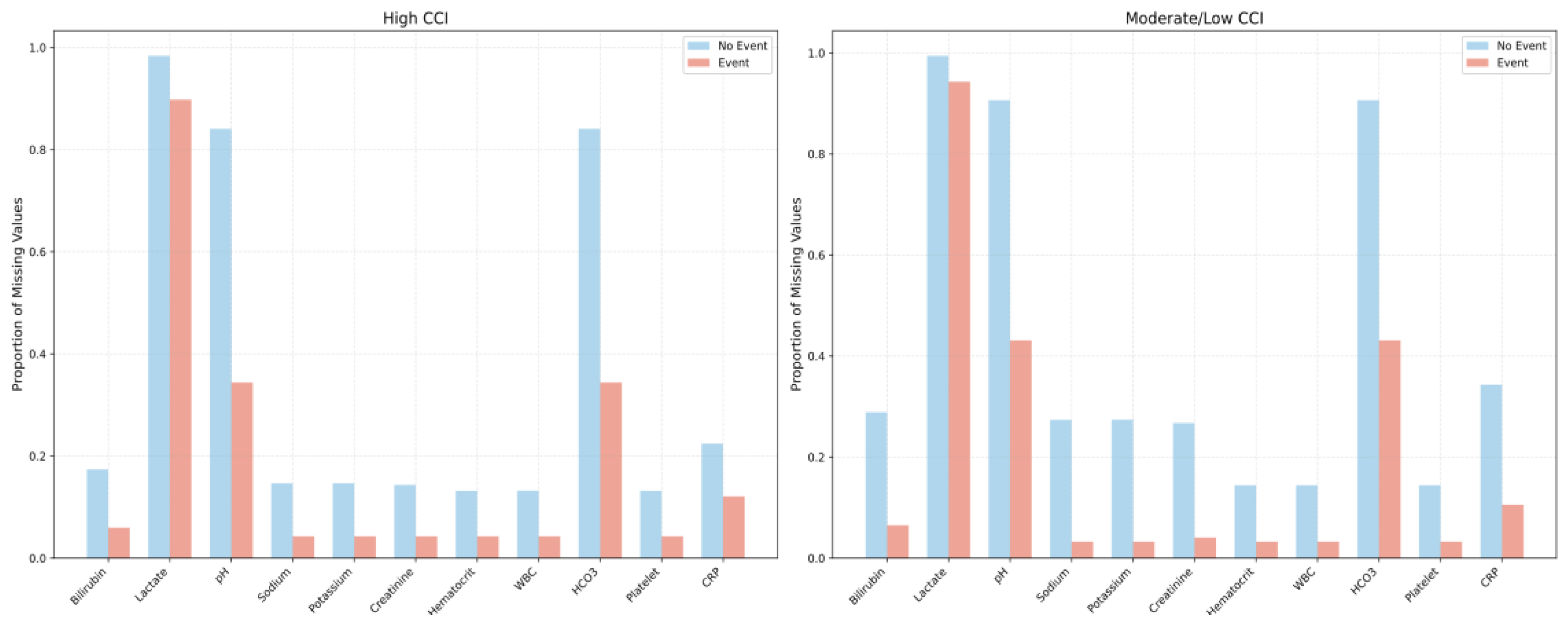

In both the high-CCI and moderate/low-CCI groups, patients who experienced adverse events consistently had fewer missing laboratory values than those without events, reflecting more frequent testing when clinical deterioration was suspected. Among the event cohorts specifically, patients in both the high-CCI and moderate/low-CCI groups exhibited similar proportions of missing values overall; however, the high-CCI group had fewer missing pH and HCO₃ values (0.34 vs. 0.43, p = 0.08), suggesting an even more intensive diagnostic approach for higher-risk patients (

Figure 1).

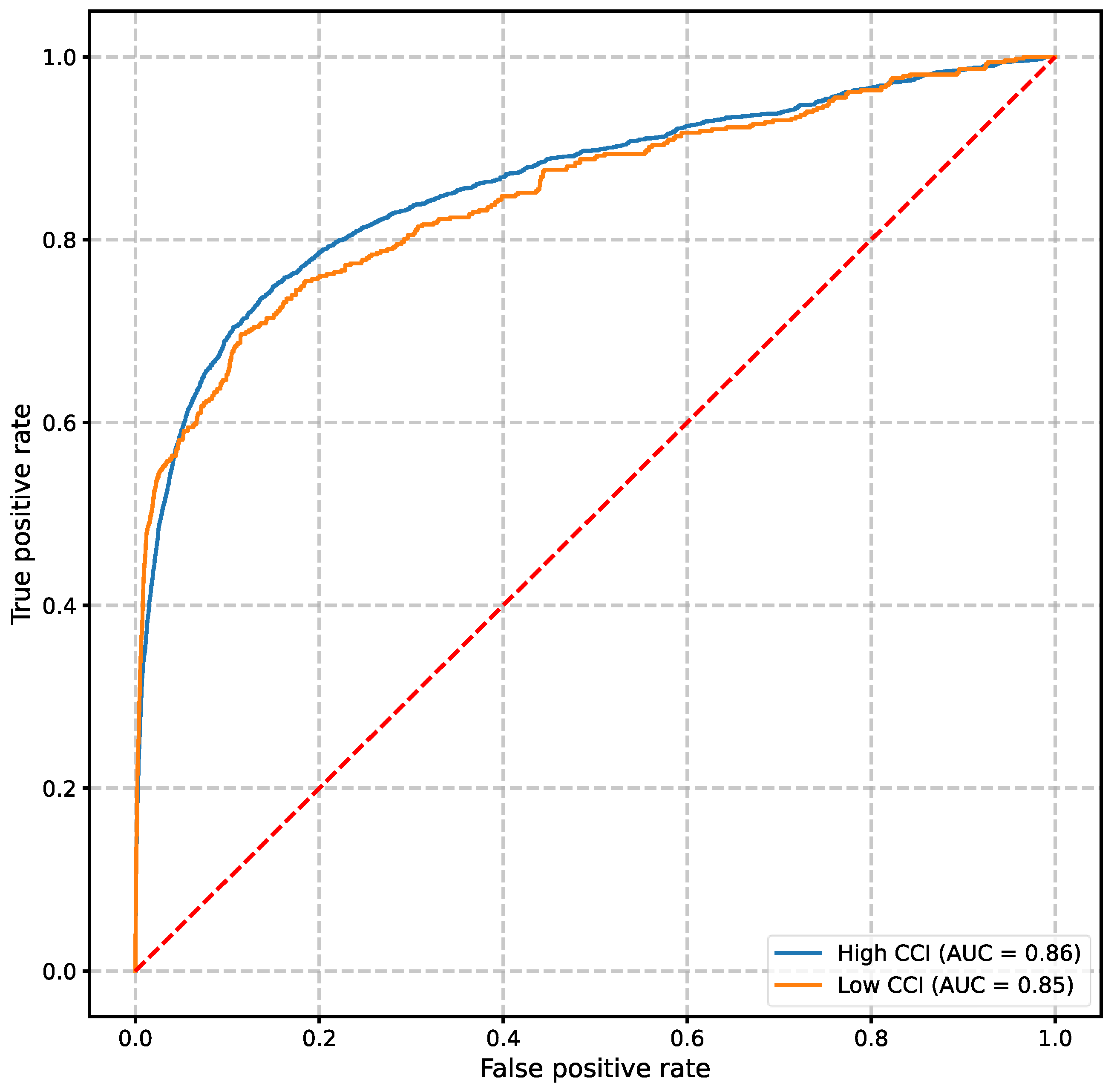

When used to predict clinical deterioration events, the VC-MAES demonstrated robust performance among both cohorts despite differences in data availability. The areas under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of the 6-hour prediction window of the high severity and moderate/low severity groups were 0.86 and 0.85, respectively (

Figure 2).

BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; F, female; IQR, interquartile range; M, male; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicated that the discriminative performance of the model did not exclusively depend on the volume of laboratory data. However, missingness alone appeared to be a clinical indicator of whether a patient was perceived as requiring further investigation, thus allowing the model to capture signals of deterioration even when laboratory data were sparse. This observation strengthens the concept of “informative presence,” whereby each decision to order or forgo a test can be diagnostically relevant, thus reflecting the degree of clinical concern.

The CCI was used to classify patients into the high severity (CCI >3) and moderate/low severity (CCI ≤3) groups. This classification revealed that the comorbidity burden can shape clinical trajectories as well as clinical decisions to order (or not order) laboratory tests. Our results showed that patients with a high CCI generally underwent more frequent testing, resulting in fewer missing values, whereas patients with a low CCI underwent less frequent testing. Despite this disparity in data volume, the AI-based early warning system maintained its robust discriminative power when used to evaluate both groups, indicating that the quantity of data alone did not guide the model performance.

Although many predictive modeling approaches focus on maximizing data completeness—either by collecting more frequent measurements or by aggressively imputing missing values—our findings suggest that such strategies may unintentionally obscure the inherent meaning behind “naturally” missing data. For instance, patients who are clinically stable are less likely to undergo repeated tests; therefore, the absence of multiple laboratory test results may be a marker of lower acuity. If we artificially fill these gaps with imputed values that do not reflect true clinical reasoning, then we could diminish the ability of the model to recognize genuine patterns in practice [

5].

Additionally, our study resonates with the broader literature that showed that capturing real-world practice patterns can enhance the generalizability of AI-based early warning systems [

7,

8]. Because clinicians with different specialties have various thresholds for ordering laboratory tests, the VC-MAES model effectively learned to incorporate these differences in clinical behavior. This approach could allow for more seamless scaling to diverse healthcare environments because it does not rely on uniform data collection protocols; instead, it adapts to existing practices.

Importantly, this study was conducted at a single center in Korea; therefore, local clinical workflows and resources may have influenced the laboratory tests that were ordered and baseline comorbidity profiles. Although the CCI is widely used, other severity measures may offer different views of missingness and event rates. Additional multi-institutional and prospective studies should be performed to further validate these findings to potentially allow refinement of the management of missing data and testing variations and optimize risk prediction across settings.

Overall, our results indicated that respecting the natural patterns of test ordering, which often reflect clinical judgment, may be more beneficial to predictive accuracy than striving for exhaustive data. By leveraging the “informative presence,” AI-based models can balance their robustness with real-world applicability, thus ensuring that they genuinely identify patients who are at risk without necessitating unnecessary or duplicative testing. The consistent performance across CCI groups suggested that the underlying context of missingness, rather than the absolute quantity of data, plays a decisive role in model accuracy.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.J.K.; methodology, T.S., E.C., J.K., and H.G.K.; formal analysis, E.C.; data curation, E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, S.J.K., E.C., J.K., and H.G.K.; project administration, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Presbyterian Medical Center approved this study on December 12, 2023, and waived the requirement for informed consent (No. 2023-12-051). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent was waived given the specific nature of the retrospective study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have reported the following: T.S., E.C., and J.K. are employees of AITRICS. None declared (S.J.K. and H.G.K.).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AI

CCI |

Artificial intelligence

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| VC-MAES |

VitalCare–Major Adverse Event Score |

References

- Kim, D.H.; Cho, A.; Park, H.C.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, M.; Kim, G.O.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.K. Regular laboratory testing and patient survival among patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A Korean nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 18360. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013, 64, 402–406. [CrossRef]

- Wells, B.J.; Chagin, K.M.; Nowacki, A.S.; Kattan, M.W. Strategies for handling missing data in electronic health record derived data. eGEMs (Wash DC) 2013, 1, 1035. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.A.; Navar, A.M.; Pencina, M.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Opportunities and challenges in developing risk prediction models with electronic health records data: A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017, 24, 198–208. [CrossRef]

- Sim, T.; Hahn, S.; Kim, K.J.; Cho, E.Y.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Ha, E.Y.; Kim, I.C.; Park, S.H.; Cho, C.H.; et al. Preserving informative presence: How missing data and imputation strategies affect the performance of an AI-based early warning score. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 2213. [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson comorbidity index: A critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom 2022, 91, 8–35. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dung, N.T.; Thach, P.N.; Phong, N.T.; Phu, V.D.; Phu, K.D.; Yen, L.M.; Thy, D.B.X.; Soltan, A.A.S.; Thwaites, L.; et al. Generalizability assessment of AI models across hospitals in a low-middle and high income country. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8270. [CrossRef]

- El Morr, C.; Ozdemir, D.; Asdaah, Y.; Saab, A.; El-Lahib, Y.; Sokhn, E.S. AI-based epidemic and pandemic early warning systems: A systematic scoping review. Health Inform J 2024, 30, 14604582241275844. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).