Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To identify the most prolific machine learning methods and the primary health care research categories and themes where these methods are applied.

- To identify publishing venues where researchers can be informed about the use of AI in primary health care and where they can publish the outcomes of their of research.

- To identify more productive institutions and countries for potential collaboration and possible funding bodies to support the research.

2. Materials and Methods

- We harvested the research publications corpus from the Scopus bibliographic database (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) using the advanced search command TITLE-ABS-KEY(({machine learning} or {decision tree*} or {random forest*} or {deep learning} or {Naive Bayes} or {Neural network*} or SVM or KNN or {rough set*} or {genetic algorithm*} or {evolutionary program*}) AND ("primary care" or "primary health")). The search was performed on the 15th of April, 2025.

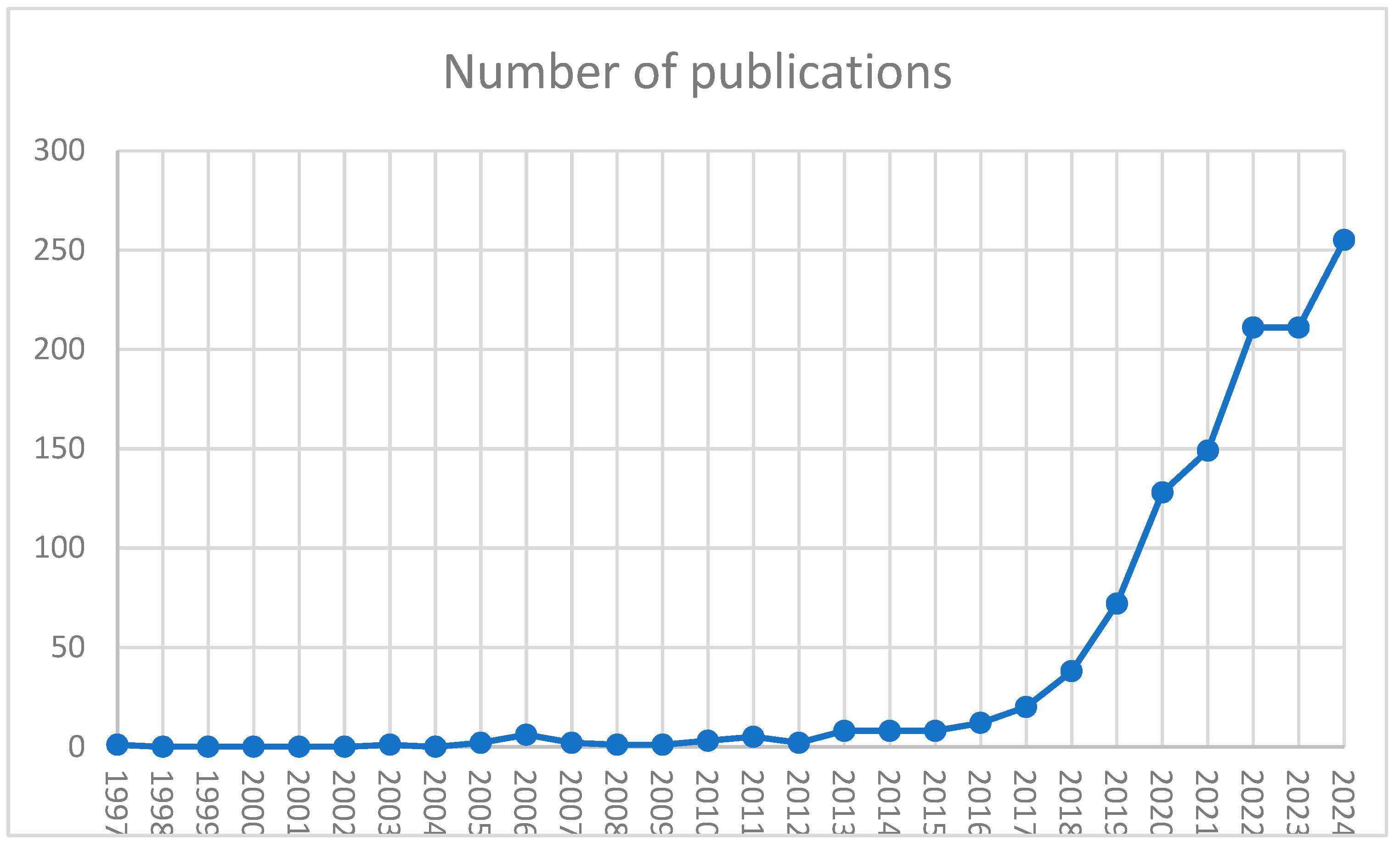

- Descriptive bibliometrics has been performed using Scopus built-in functions like country and institution productivity analysis, literature production trend analysis, journal analytics, funding bodies analytics, and document type analytics.

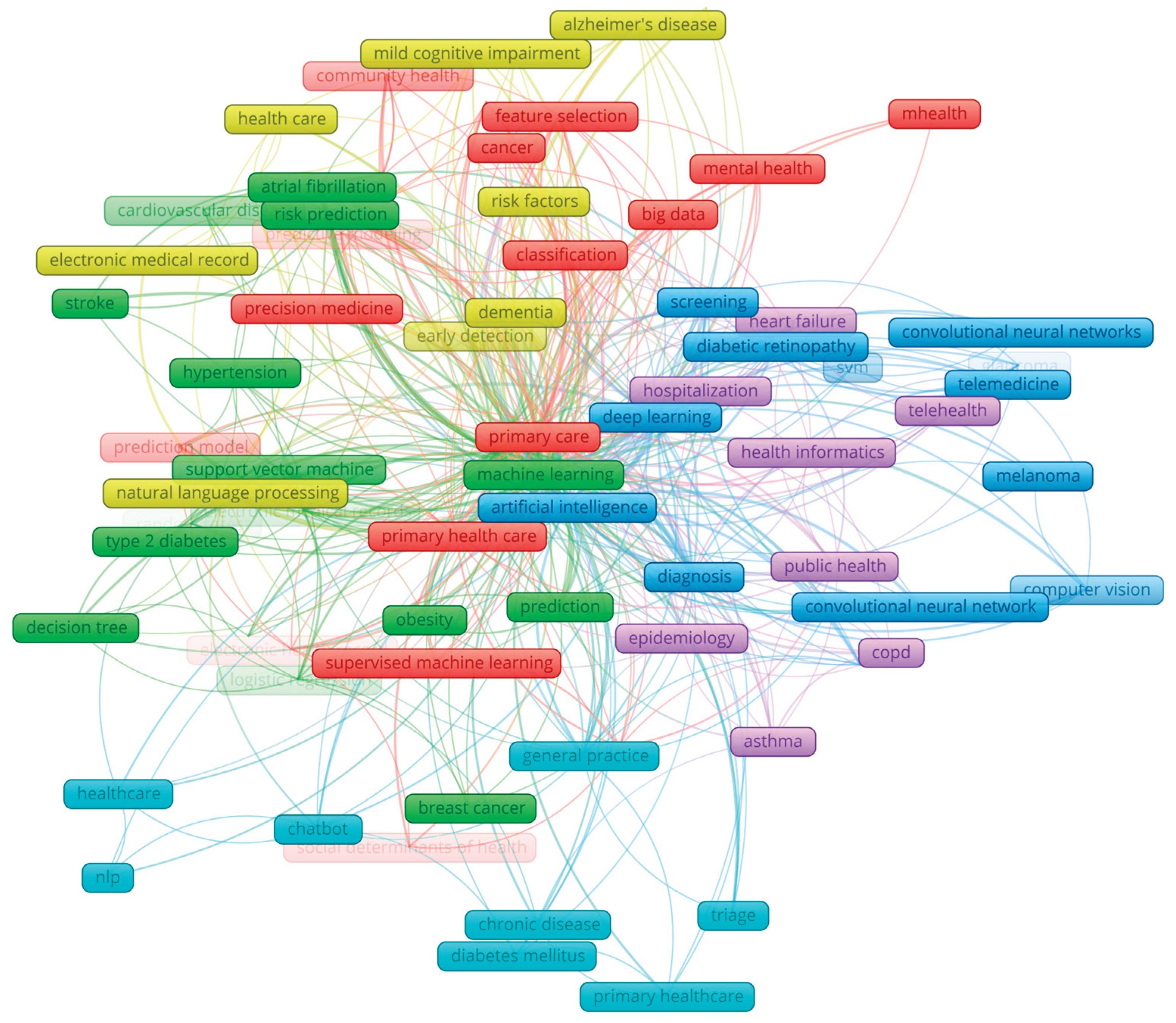

- The author's keywords landscape was induced from the entire corpus harvested in Step 1 using bibliometric mapping with VOSViewer software version 1.6.20 (Leiden University, The Netherlands). VOSViewer employs text mining to recognize various text terms, specifically authors' keywords from the keyword lists. It then uses a mapping technique called Visualisation of Similarities (VoS) [33], based on the co-word analysis to induce different bibliometric maps, in this case, the author's keywords landscape. Authors’ keywords were selected as meaningful units of information referred to as codes, as they most concisely present what authors intended to communicate to the scientific community. The number of keywords to be included in the landscape was determined by the Zipf law [34].

- Inductive content analysis was initially conducted by examining the frequency of codes. Subsequent qualitative network analysis focused on the links and proximity between popular codes to identify distinct subnetworks representing research categories. Categories that share a common cluster were condensed together to form a cohesive research theme.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Bibliometrics

3.1.1. Funding

3.2. Inductive Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis

3.2.1. Literature Review Based on Induced Themes and Categories

- Natural language processing and Clinical Decision Support Systems in dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and mild cognitive impairment: Maclagam et al. [40,41] used natural language processing of free texts in electronic health records and clinical notes to identify patients with risk of dementia, Alzheimer’s or cognitive impairment [42] in a preventive manner to shorten the length of hospitalization, delay admission to long term care and reduce the number of underrecognized patients with the above diseases. Artificial intelligence and speech and language processing have been used to predict the occurrence of the Alzheimer disease [43] or cognitive decline in the context of Alzheimer's disease or aging to facilitate restorative and preventive treatments [44,45,46,47,48,49].

- Optimizing health care and managing risk and patient safety in primary health with machine learning: The use of machine learning in primary health care has recently gained popularity and promise [28,50,51,52]. Pikoula et al. [53] and Jennings et al. [54] used clustering, correspondence analysis, and decision trees on medical records data of 30961 smokers diagnosed with COPD to classify them into groups with differing risk factors, comorbidities, and prognoses. In general AI is often used in managing COPD in general [55]. Oude et al. [56] and developed a clinical decision support system based on various decision tree algorithms for self-referral of patients with low back pain to prevent their transition into chronic back pain. In general AI is frequently used to support services for patients with musculoskeletal diseases [57]. Sekelj et al. [58] and performed a study to evaluate the ability of machine learning algorithms to identify patients at high risk of atrial fibrillation in primary care. They found that the algorithm performed in a way that, if implemented in practice, could be an effective tool for narrowing the population who would benefit from atrial fibrillation screening. Similarly Norman et al [59] used machine learning to predict new cases of hypertension. Liu et al. found out that a machine learning-assisted nonmydriatic point-of-care screening administered during primary care visits would increase the adherence to recommendations for follow-up eye care in patients with diabetes. On an epidemiology level new diabetes patients were identified using stochastic gradient boosting [60]. Priya and Thilagamani [61] developed a machine learning-based prediction model to predict arterial stiffness risk in diabetes patients. Machine learning has also been used for the prediction/classification of infectious diseases [62,63], anxiety [64], COVID severity [65], cancer [26,66], or even patient no-shows [19,67]. On the other hand, Evans et al. [68], Fong [69] and Govender [70] developed an automated classification of patient safety reports system using machine learning.

- Using supervised learning and data/text mining to analyze primary health-based social determinants: Natural language processing and big data analytics can potentially transform primary health care [71,72]. Bejan et al. [73] developed a methodology based on text mining to identify rare and severe social determinants of health in homelessness and adverse childhood experiences found in electronic healthcare records. Chilman et al. [74] successfully developed and evaluated a natural language processing and text mining application to analyze psychiatric clinical notes of 341 720 de-identified clinical records of a large secondary mental healthcare provider in south London to identify patients' occupations and Hatef et [75]al used a similar approach on electronic health records to identify patients with high-risk housing issues. On the other hand, Scaccia [76] applied NLP to explore the concept of equity in community psychology after the COVID-19 crisis by analyzing relevant literature, and Hadley et al. [77] examined the trends in health equity by text mining revenue service tax documentation submitted by nonprofit hospitals. Ford et al. [78]developed a supervised machine learning application for automated detection of patients with dementia without formal diagnosing in routinely collected electronic health records to improve service planning and delivery of quality care. Kasthurirathne et al. [79] used random forest machine learning and NLP algorithms on integrated patient clinical data and community-level data representing patients' social determinants of health obtained from multiple sources to build models to predict the need for any mental health dietitian social work or other SDH service referrals. Big data analysis on traditional non-text clinical was used to recognize patterns of collaboration between physicians, nurses, and dietitians in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and to compare these patterns with the clinical evolution of the patients within the context of primary care and determine patterns which lead to the improved treatment of patients [80], classify skin diseases [81], predict the influx of patients to primary health centers [82] or for early prediction of risk pregnancies [83]. Garies et al [84]used machine learning to derive health related social determinants of primary care patients. On a larger scale AI was used to derive social determinants of health data from medical records in Canada [85].

- Deep learning in screening and diagnosing: Nemesure et al. [64] developed a machine learning pipeline of machine learning algorithms, including deep learning, to predict Generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder on data from an observational study of 4184 undergraduate students. Deep learning for automatic image analysis [86] has been used in various studies for the early diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy in diabetes patients [87,88,89] or in predicting HER2 in blader cancer patients [90] . Convolutional neural networks were used for early diagnosis of multiple cardiovascular diseases early [91], chronic respiratory diseases [92], or melanoma [93] reaching a high accuracy between 94% and 98% and 94%. Graph convolutional network was employed for automatic diagnosing and integrated into more than 100 hospital information systems in China to improve clinical decision-making [94]. Zhang et al. [95] developed a Deep-learning model for sarcopenia diagnosis using clinical characteristics and laboratory indicators of aging cohorts.

- Health informatics in primary health: The COVID–19 pandemic additionally triggered the employment of machine learning in primary health for various applications like management of COVID with intelligent digital health systems [96]; chatbots to classify patient symptoms and recommendations of appropriate medical experts [97], evaluation of vaccine allergy documentation [98], predicting the need for hospitalization or home monitoring of confirmed and unconfirmed coronavirus patients [99] and predicting severity of Covid among older adults [100]. From the epidemiological viewpoint, machine learning in primary health has been used for frailty identification [101], heart failure prediction [102], the incidence of infectious diseases from routinely collected ambulatory records [103], and identifying psychological antecedents and predictors of vaccine hesitancy [104]. On the other hand, machine learning has been used for clinical decision support for childhood asthma management [105] and predictive analytics in nursing [106]. In general health informatics supported by machine learning can significantly improve primary health care [107,108].

- Chatbots in primary health care: In the last four years, chatbots become more frequently used in primary health care [109,110,111]. They are used to make the healthcare systems more interactive by using NLP to understand patients' queries and give suitable responses [112,113,114] or even to virtualise primary health care [115], such as detecting possible COVID cases and guiding the patients [116]. Further examples include chatbots to try to persuade smokers to quit smoking [117], help patients with anxiety depressive symptoms or burnout syndrome [118,119], provide support to patients with chronic diseases [120], detect early onset of cognitive impairment [121], suicide intentions [122], guide mothers or family members about breastfeeding [123] or address patient inquires in hospital environments [124].

3.3. Deductive Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis

3.4. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hefti, L.; Boëthius ,Hanna; Loppow ,Detlef; Serry ,Nakisa; Martin ,Rocio; Rupalla ,Katrin; Krämer ,Dietmar; Juchler ,Isabelle; Masters ,Caitlin; and Voelter, V. The Tango to Modern Collaboration and Patient-Centric Value Generation in Health Care – a Real-World Guide from Practitioners for Practitioners: A Field Analysis on Value-Based Health Care of 12 Leading Institutions Worldwide. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2025, 41, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P.; Vošner, H.B.; Kokol, M.; Završnik, J. The Quality of Digital Health Software: Should We Be Concerned?: DIGITAL HEALTH 2022. [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.; del Barrio, J.; Nuño, R.; Errea, M. Value-Based Digital Health: A Systematic Literature Review of the Value Elements of Digital Health Care. DIGITAL HEALTH 2024, 10, 20552076241277438. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Implementing the Primary Health Care Approach: A Primer; World Health Organization, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-009058-3.

- Pagliari, C. Digital Health and Primary Care: Past, Pandemic and Prospects. Journal of Global Health 2021, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Borges, D.G.F.; Coutinho, E.R.; Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Grave, M.; Vasconcelos, A.O.; Landau, L.; Coutinho, A.L.G.A.; Ramos, P.I.P.; Barral-Netto, M.; Pinho, S.T.R.; et al. Combining Machine Learning and Dynamic System Techniques to Early Detection of Respiratory Outbreaks in Routinely Collected Primary Healthcare Records. BMC Med Res Methodol 2025, 25, 99. [CrossRef]

- Manickam, P.; Mariappan, S.A.; Murugesan, S.M.; Hansda, S.; Kaushik, A.; Shinde, R.; Thipperudraswamy, S.P. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Assisted Biomedical Systems for Intelligent Healthcare. Biosensors 2022, 12, 562. [CrossRef]

- Pallathadka, H.; Mustafa, M.; Sanchez, D.T.; Sekhar Sajja, G.; Gour, S.; Naved, M. IMPACT OF MACHINE Learning ON Management, Healthcare AND AGRICULTURE. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, 80, 2803–2806. [CrossRef]

- Panch, T.; Szolovits, P.; Atun, R. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Health Systems. J Glob Health 2018, 8, 020303. [CrossRef]

- Plana, D.; Shung, D.L.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Saraf, A.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Kann, B.H. Randomized Clinical Trials of Machine Learning Interventions in Health Care: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2233946. [CrossRef]

- Quazi, S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Precision and Genomic Medicine. Med Oncol 2022, 39, 120. [CrossRef]

- Rubinger, L.; Gazendam, A.; Ekhtiari, S.; Bhandari, M. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Research and Healthcare. Injury 2023, 54, S69–S73. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xing, L.; Zou, J.; Wu, J.C. Shifting Machine Learning for Healthcare from Development to Deployment and from Models to Data. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2022, 6, 1330–1345. [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Araos, A.; Contreras, C.; Kaushal, H.; Prodanoff, Z. Predictive Optimization of Patient No-Show Management in Primary Healthcare Using Machine Learning. J Med Syst 2025, 49, 7. [CrossRef]

- Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.; Islam, M.S.; Alaboson, J.; Ola, O.; Hasan, I.; Islam, N.; Mainali, S.; Martina, T.; Silenga, E.; Muyangana, M.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Health in Improving Primary Health Care Service Delivery in LMICs: A Systematic Review. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 2023, 16, 303–320. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Hu ,Xiaohao; Yan ,Linyang; Li ,Zhiyin; Li ,Bo; Chen ,Xinpeng; Lin ,Zexun; Zeng ,Huiqiong; Li ,Chun; Mo ,Yingqian; et al. Development and Validation of a Cost-Effective Machine Learning Model for Screening Potential Rheumatoid Arthritis in Primary Healthcare Clinics. Journal of Inflammation Research 2025, 18, 1511–1522. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Application and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Early Screening of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease at Primary Healthcare Institutions in China. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2024, 19, 1061–1067. [CrossRef]

- Hautala, A.J.; Shavazipour, B.; Afsar, B.; Tulppo, M.P.; Miettinen, K. Machine Learning Models in Predicting Health Care Costs in Patients with a Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Prospective Pilot Study. Cardiovascular Digital Health Journal 2023, 4, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Araos, A.; Contreras, C.; Kaushal, H.; Prodanoff, Z. Predictive Optimization of Patient No-Show Management in Primary Healthcare Using Machine Learning. J Med Syst 2025, 49, 7. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Madanian, S.; Parry, D. Enhancing Health Equity by Predicting Missed Appointments in Health Care: Machine Learning Study. JMIR Medical Informatics 2024, 12, e48273. [CrossRef]

- Erku, D.; Khatri, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Digital Health Interventions to Improve Access to and Quality of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 6854. [CrossRef]

- Lamem, M.F.H.; Sahid, M.I.; Ahmed, A. Artificial Intelligence for Access to Primary Healthcare in Rural Settings. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2025, 5, 100173. [CrossRef]

- Abdulazeem, H.; Whitelaw, S.; Schauberger, G.; Klug, S.J. A Systematic Review of Clinical Health Conditions Predicted by Machine Learning Diagnostic and Prognostic Models Trained or Validated Using Real-World Primary Health Care Data. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0274276. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, D.; Abbasgholizadeh Rahimi, S. Implications of Conscious AI in Primary Healthcare. Fam Med Community Health 2024, 12, e002625. [CrossRef]

- Berkel, C.; Knox, D.C.; Flemotomos, N.; Martinez, V.R.; Atkins, D.C.; Narayanan, S.S.; Rodriguez, L.A.; Gallo, C.G.; Smith, J.D. A Machine Learning Approach to Improve Implementation Monitoring of Family-Based Preventive Interventions in Primary Care. Implementation Research and Practice 2023, 4, 26334895231187906. [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.T.; Matin, R.N.; van der Schaar, M.; Prathivadi Bhayankaram, K.; Ranmuthu, C.K.I.; Islam, M.S.; Behiyat, D.; Boscott, R.; Calanzani, N.; Emery, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Algorithms for Early Detection of Skin Cancer in Community and Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. The Lancet Digital Health 2022, 4, e466–e476. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. A Clinician’s Guide to Artificial Intelligence (AI): Why and How Primary Care Should Lead the Health Care AI Revolution. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2022, 35, 175. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.A.; Légaré, F.; Sharma, G.; Archambault, P.; Zomahoun, H.T.V.; Chandavong, S.; Rheault, N.; Wong, S.T.; Langlois, L.; Couturier, Y.; et al. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Community-Based Primary Health Care: Systematic Scoping Review and Critical Appraisal. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23, e29839. [CrossRef]

- Rakers, M.M.; van Buchem, M.M.; Kucenko, S.; de Hond, A.; Kant, I.; van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.M.; Leeuwenberg, A.M.; Chavannes, N.; Villalobos-Quesada, M.; et al. Availability of Evidence for Predictive Machine Learning Algorithms in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2432990. [CrossRef]

- Taloyan, M.; Jaranka, A.; Bidonde, J.; Flodgren, G.; Roberts, N.W.; Hägglund, M.; Nilsson, G.H.; Papachristou, P. Remote Digital Monitoring for Selected Chronic Diseases in Primary Health Care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P. Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis in Hospital Libraries. Journal of Hospital Librarianship 2023, 0, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Završnik, J.; Kokol, P.; Žlahtič, B.; Blažun Vošner, H. Artificial Intelligence and Pediatrics: Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis. Electronics 2024, 13, 512. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing Bibliometric Networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp. 285–320 ISBN 978-3-319-10377-8.

- Gupta, S.; Singh, V.K. Distributional Characteristics of Dimensions Concepts: An Empirical Analysis Using Zipf’s Law. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 1037–1053. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, R.E.; Mangoud, A.M. Modeling Obesity Using Abductive Networks. Computers and Biomedical Research 1997, 30, 451–471. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K. Using Rough Sets, Neural Networks, and Logistic Regression to Predict Compliance with Cholesterol Guidelines Goals in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. AMIA ... Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium 2003, 834.

- Stiglic, G.; Kokol, P. Intelligent Patient and Nurse Scheduling in Ambulatory Health Care Centers. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference; January 2005; pp. 5475–5478.

- Dimitropoulou, A. Revealed: Countries With The Best Health Care Systems, 2023 Available online: https://ceoworld.biz/2023/08/25/revealed-countries-with-the-best-health-care-systems-2023/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Kokol, P.; Železnik, D.; Završnik, J.; Blažun Vošner, H. Nursing Research Literature Production in Terms of the Scope of Country and Health Determinants: A Bibliometric Study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2019, 51, 590–598. [CrossRef]

- Maclagan, L.C.; Abdalla, M.; Harris, D.A.; Stukel, T.A.; Chen, B.; Candido, E.; Swartz, R.H.; Iaboni, A.; Jaakkimainen, R.L.; Bronskill, S.E. Can Patients with Dementia Be Identified in Primary Care Electronic Medical Records Using Natural Language Processing? Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research 2023, 7, 42–58. [CrossRef]

- Calzà, L.; Gagliardi, G.; Rossini Favretti, R.; Tamburini, F. Linguistic Features and Automatic Classifiers for Identifying Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Computer Speech and Language 2021, 65. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R.; Bundele, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A. A Systematic Review of Natural Language Processing Techniques for Early Detection of Cognitive Impairment. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health 2025, 3, 100205. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H. Natural Language Processing of Electronic Health Records for Predicting Alzheimer’s Disease. In Deep Generative Models for Integrative Analysis of Alzheimer’s Biomarkers; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025; pp. 141–174 ISBN 979-8-3693-6442-0.

- Amini, S.; Cheng, Y.; Magdamo, C.G.; Paschalidis, I.; Das, S. From Normal Cognition to Dementia: Using Natural Language Processing to Identify Cognitive Stages from Clinical Notes. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20, e089228. [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente Garcia, S.; Ritchie, C.W.; Luz, S. Artificial Intelligence, Speech, and Language Processing Approaches to Monitoring Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2020, 78, 1547–1574. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.A.; Lee, E.E.; Jeste, D.V.; Van Patten, R.; Twamley, E.W.; Nebeker, C.; Yamada, Y.; Kim, H.-C.; Depp, C.A. Artificial Intelligence Approaches to Predicting and Detecting Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A Conceptual Review. Psychiatry Research 2020, 284. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Hou, W. VGG-TSwinformer: Transformer-Based Deep Learning Model for Early Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2023, 229. [CrossRef]

- Roshanzamir, A.; Aghajan, H.; Soleymani Baghshah, M. Transformer-Based Deep Neural Network Language Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Assessment from Targeted Speech. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, T.J.; Zahra, S.R.; Wu, F.; Alwakeel, A.; Alwakeel, M.; Jeribi, F.; Hijji, M. Deep Learning-Based Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ibengera, A G, E., H.; Eichbeum, H, I. Primary Health Research: A Comprehensive Review of Current Trends and Future Directions. Health Science Journal 2023, 17, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Hanif, M.; Mirza, E.; Khan, M.A.; Malik, M. Machine Learning in Primary Care: Potential to Improve Public Health. Journal of Medical Engineering and Technology 2021, 45, 75–80. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Martin, C.M.; Sturmberg, J.P.; Hall, S.; Bazemore, A.; Kakadiaris, I.A.; Lin, S. What Complexity Science Predicts About the Potential of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning to Improve Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med 2024, 37, 332–345. [CrossRef]

- Pikoula, M.; Quint, J.K.; Nissen, F.; Hemingway, H.; Smeeth, L.; Denaxas, S. Identifying Clinically Important COPD Sub-Types Using Data-Driven Approaches in Primary Care Population Based Electronic Health Records. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.A.; Hollands, S.; Keeler, E.; Wenger, N.S.; Reuben, D.B. The Effects of Dementia Care Co-Management on Acute Care, Hospice, and Long-Term Care Utilization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2020, 68, 2500–2507. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hao, J.; Sun, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Q. Applications of Digital Health Technologies and Artificial Intelligence Algorithms in COPD: Systematic Review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2025, 25, 77. [CrossRef]

- Oude Nijeweme-d’Hollosy, W.; van Velsen, L.; Poel, M.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.M.; Soer, R.; Hermens, H. Evaluation of Three Machine Learning Models for Self-Referral Decision Support on Low Back Pain in Primary Care. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2018, 110, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Tilburg, M.L. van; Spin, I.; Pisters, M.F.; Staal, J.B.; Ostelo, R.W.; Velde, M. van der; Veenhof, C.; Kloek, C.J. Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of Digital Health Services for People With Musculoskeletal Conditions in the Primary Health Care Setting: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e49868. [CrossRef]

- Sekelj, S.; Sandler, B.; Johnston, E.; Pollock, K.G.; Hill, N.R.; Gordon, J.; Tsang, C.; Khan, S.; Ng, F.S.; Farooqui, U. Detecting Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation in UK Primary Care: Validation of a Machine Learning Prediction Algorithm in a Retrospective Cohort Study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2021, 28, 598–605. [CrossRef]

- Norrman, A.; Hasselström, J.; Ljunggren, G.; Wachtler, C.; Eriksson, J.; Kahan, T.; Wändell, P.; Gudjonsdottir, H.; Lindblom, S.; Ruge, T.; et al. Predicting New Cases of Hypertension in Swedish Primary Care with a Machine Learning Tool. Preventive Medicine Reports 2024, 44, 102806. [CrossRef]

- Wändell, P.; Carlsson, A.C.; Wierzbicka, M.; Sigurdsson, K.; Ärnlöv, J.; Eriksson, J.; Wachtler, C.; Ruge, T. A Machine Learning Tool for Identifying Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Primary Care. Primary Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 501–505. [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.M.; Thilagamani Prediction of Arterial Stiffness Risk in Diabetes Patients through Deep Learning Techniques. Information Technology and Control 2022, 51, 678–691. [CrossRef]

- Borges, D.G.F.; Coutinho, E.R.; Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Grave, M.; Vasconcelos, A.O.; Landau, L.; Coutinho, A.L.G.A.; Ramos, P.I.P.; Barral-Netto, M.; Pinho, S.T.R.; et al. Combining Machine Learning and Dynamic System Techniques to Early Detection of Respiratory Outbreaks in Routinely Collected Primary Healthcare Records. BMC Med Res Methodol 2025, 25, 99. [CrossRef]

- Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Rawson, T.M.; Ahmad, R.; Buchard, A.; Georgiou, P.; Lescure, F.-X.; Birgand, G.; Holmes, A.H. Machine Learning for Clinical Decision Support in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review of Current Applications. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020, 26, 584–595. [CrossRef]

- Nemesure, M.D.; Heinz, M.V.; Huang, R.; Jacobson, N.C. Predictive Modeling of Depression and Anxiety Using Electronic Health Records and a Novel Machine Learning Approach with Artificial Intelligence. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Gude-Sampedro, F.; Fernández-Merino, C.; Ferreiro, L.; Lado-Baleato, Ó.; Espasandín-Domínguez, J.; Hervada, X.; Cadarso, C.M.; Valdés, L. Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model Based on Comorbidities to Predict COVID-19 Severity: A Population-Based Study. Int J Epidemiol 2021, 50, 64–74. [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.T.; Calanzani, N.; Saji, S.; Duffy, S.W.; Emery, J.; Hamilton, W.; Singh, H.; de Wit, N.J.; Walter, F.M. Artificial Intelligence Techniques That May Be Applied to Primary Care Data to Facilitate Earlier Diagnosis of Cancer: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23. [CrossRef]

- Aladeemy, M.; Adwan, L.; Booth, A.; Khasawneh, M.T.; Poranki, S. New Feature Selection Methods Based on Opposition-Based Learning and Self-Adaptive Cohort Intelligence for Predicting Patient No-Shows. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 86, 105866. [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.P.; Anastasiou, A.; Edwards, A.; Hibbert, P.; Makeham, M.; Luz, S.; Sheikh, A.; Donaldson, L.; Carson-Stevens, A. Automated Classification of Primary Care Patient Safety Incident Report Content and Severity Using Supervised Machine Learning (ML) Approaches. Health Informatics J 2020, 26, 3123–3139. [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.; Behzad, S.; Pruitt, Z.; Ratwani, R.M. A Machine Learning Approach to Reclassifying Miscellaneous Patient Safety Event Reports. Journal of Patient Safety 2021, 17, E829–E833. [CrossRef]

- Govender, I.; Tumbo, J.; Mahadeo, S. Using ChatGPT in Family Medicine and Primary Health Care. South African Family Practice 2024, 66, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Bundi, D.N. Adoption of Machine Learning Systems within the Health Sector: A Systematic Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda. Digital Transformation and Society 2023, 3, 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Y.; Nair, A.; Shariq, S.; Hannan, S.H. Transforming Primary Healthcare through Natural Language Processing and Big Data Analytics. BMJ 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bejan, C.A.; Angiolillo, J.; Conway, D.; Nash, R.; Shirey-Rice, J.K.; Lipworth, L.; Cronin, R.M.; Pulley, J.; Kripalani, S.; Barkin, S.; et al. Mining 100 Million Notes to Find Homelessness and Adverse Childhood Experiences: 2 Case Studies of Rare and Severe Social Determinants of Health in Electronic Health Records. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2018, 25, 61–71. [CrossRef]

- Chilman, N.; Song, X.; Roberts, A.; Tolani, E.; Stewart, R.; Chui, Z.; Birnie, K.; Harber-Aschan, L.; Gazard, B.; Chandran, D.; et al. Text Mining Occupations from the Mental Health Electronic Health Record: A Natural Language Processing Approach Using Records from the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) Platform in South London, UK. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042274. [CrossRef]

- Hatef, E.; Singh Deol, G.; Rouhizadeh, M.; Li, A.; Eibensteiner, K.; Monsen, C.B.; Bratslaver, R.; Senese, M.; Kharrazi, H. Measuring the Value of a Practical Text Mining Approach to Identify Patients With Housing Issues in the Free-Text Notes in Electronic Health Record: Findings of a Retrospective Cohort Study. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Scaccia, J.P. Examining the Concept of Equity in Community Psychology with Natural Language Processing. Journal of Community Psychology 2021, 49, 1718–1731. [CrossRef]

- Hadley, E.; Marcial, L.H.; Quattrone, W.; Bobashev, G. Text Analysis of Trends in Health Equity and Disparities From the Internal Revenue Service Tax Documentation Submitted by US Nonprofit Hospitals Between 2010 and 2019: Exploratory Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.; Sheppard, J.; Oliver, S.; Rooney, P.; Banerjee, S.; Cassell, J.A. Automated Detection of Patients with Dementia Whose Symptoms Have Been Identified in Primary Care but Have No Formal Diagnosis: A Retrospective Case-Control Study Using Electronic Primary Care Records. BMJ Open 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kasthurirathne, S.N.; Vest, J.R.; Menachemi, N.; Halverson, P.K.; Grannis, S.J. Assessing the Capacity of Social Determinants of Health Data to Augment Predictive Models Identifying Patients in Need of Wraparound Social Services. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2018, 25, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Conca, T.; Saint-Pierre, C.; Herskovic, V.; Sepúlveda, M.; Capurro, D.; Prieto, F.; Fernandez-Llatas, C. Multidisciplinary Collaboration in the Treatment of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care: Analysis Using Process Mining. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2018, 20. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.M.; Patel, A.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, P.J. From Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Pandemic-Driven Initiative. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 6, 88–89. [CrossRef]

- Cubillas, J.J.; Ramos, M.I.; Feito, F.R. Use of Data Mining to Predict the Influx of Patients to Primary Healthcare Centres and Construction of an Expert System. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E.; Kumbangsila, M.; Aryuni, M.; Richard; Zakiyyah, A.Y.; Sano, A.V.D. Early Risk Pregnancy Prediction Based on Machine Learning Built on Intelligent Application Using Primary Health Care Cohort Data. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 2023, 1008, 145–161. [CrossRef]

- Garies, S.; Liang, S.; Weyman, K.; Ramji, N.; Alhaj, M.; Pinto, A.D. Developing an AI Tool to Derive Social Determinants of Health for Primary Care Patients: Qualitative Findings From a Codesign Workshop. The Annals of Family Medicine 2024, 22, 317–324. [CrossRef]

- Davis, V.H.; Qiang, J.R.; MacCarthy, I.A.; Howse, D.; Seshie, A.Z.; Kosowan, L.; Delahunty-Pike, A.; Abaga, E.; Cooney, J.; Robinson, M.; et al. Perspectives on Using Artificial Intelligence to Derive Social Determinants of Health Data From Medical Records in Canada: Large Multijurisdictional Qualitative Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e52244. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B. Practical Applications of Advanced Cloud Services and Generative AI Systems in Medical Image Analysis 2024.

- Wintergerst, M.W.M.; Bejan, V.; Hartmann, V.; Schnorrenberg, M.; Bleckwenn, M.; Weckbecker, K.; Finger, R.P. Telemedical Diabetic Retinopathy Screening in a Primary Care Setting: Quality of Retinal Photographs and Accuracy of Automated Image Analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2022, 29, 286–295. [CrossRef]

- Verbraak, F.D.; Abramoff, M.D.; Bausch, G.C.F.; Klaver, C.; Nijpels, G.; Schlingemann, R.O.; van der Heijden, A.A. Diagnostic Accuracy of a Device for the Automated Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in a Primary Care Setting. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 651–656. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, A.; Govindaiah, A.; Deobhakta, A.; Gupta, M.; Rosen, R.; Saleem, S.; Smith, R.T. Development and Validation of an Automated Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Tool for Primary Care Setting. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, e147–e148. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Fu, S.; Weng, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Q. Deep Learning-Based Computed Tomography Urography Image Analysis for Prediction of HER2 Status in Bladder Cancer. Journal of Cancer 2024, 15, 6336–6344. [CrossRef]

- Baghel, N.; Dutta, M.K.; Burget, R. Automatic Diagnosis of Multiple Cardiac Diseases from PCG Signals Using Convolutional Neural Network. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 197. [CrossRef]

- Baghel, N.; Nangia, V.; Dutta, M.K. ALSD-Net: Automatic Lung Sounds Diagnosis Network from Pulmonary Signals. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 17103–17118. [CrossRef]

- Helenason, J.; Ekström ,Christoffer; Falk ,Magnus; and Papachristou, P. Exploring the Feasibility of an Artificial Intelligence Based Clinical Decision Support System for Cutaneous Melanoma Detection in Primary Care – a Mixed Method Study. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 2024, 42, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Chen, J.; Lu, C.; Huang, H. The Graph-Based Mutual Attentive Network for Automatic Diagnosis.; 2020; Vol. 2021-January, pp. 3393–3399.

- Zhang, H.; Yin, M.; Liu, Q.; Ding, F.; Hou, L.; Deng, Y.; Cui, T.; Han, Y.; Pang, W.; Ye, W.; et al. Machine and Deep Learning-Based Clinical Characteristics and Laboratory Markers for the Prediction of Sarcopenia. Chinese Medical Journal 2023, 136, 967–973. [CrossRef]

- Gerotziafas, G.T.; Catalano, M.; Theodorou, Y.; Dreden, P.V.; Marechal, V.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Carter, C.; Jabeen, N.; Harenberg, J.; Elalamy, I.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Need for an Integrated and Equitable Approach: An International Expert Consensus Paper. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2021, 121, 992–1007. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kang, J.; Yeo, J. Medical Specialty Recommendations by an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot on a Smartphone: Development and Deployment. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, E.M.; Greenhawt, M.; Shaker, M.; Kosowan, L.; Singer, A.G. Primary Care Provider-Reported Prevalence of Vaccine and Polyethylene Glycol Allergy in Canada. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2021, 127, 446-450.e1. [CrossRef]

- Vetrugno, G.; Laurenti, P.; Franceschi, F.; Foti, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Cicconi, M.; la Milia, D.I.; Di Pumpo, M.; Carini, E.; Pascucci, D.; et al. Gemelli Decision Tree Algorithm to Predict the Need for Home Monitoring or Hospitalization of Confirmed and Unconfirmed COVID-19 Patients (GAP-Covid19): Preliminary Results from a Retrospective Cohort Study. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2021, 25, 2785–2794. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Chu, C.; Grad, R.; Karanofsky, M.; Arsenault, M.; Ronquillo, C.; Vedel, I.; McGilton, K.; Wilchesky, M. Explainable Machine Learning Model to Predict COVID-19 Severity Among Older Adults in the Province of Quebec. Annals of family medicine 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aponte-Hao, S.; Wong, S.T.; Thandi, M.; Ronksley, P.; McBrien, K.; Lee, J.; Grandy, M.; Katz, A.; Mangin, D.; Singer, A.; et al. Machine Learning for Identification of Frailty in Canadian Primary Care Practices. International Journal of Population Data Science 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Stewart, W.F.; Sun, J.; Ng, K.; Yan, X. Recurrent Neural Networks for Early Detection of Heart Failure from Longitudinal Electronic Health Record Data: Implications for Temporal Modeling with Respect to Time before Diagnosis, Data Density, Data Quantity, and Data Type. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lanera, C.; Baldi, I.; Francavilla, A.; Barbieri, E.; Tramontan, L.; Scamarcia, A.; Cantarutti, L.; Giaquinto, C.; Gregori, D. A Deep Learning Approach to Estimate the Incidence of Infectious Disease Cases for Routinely Collected Ambulatory Records: The Example of Varicella-Zoster. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Rustagi, N.; Choudhary, Y.; Asfahan, S.; Deokar, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Thirunavukkarasu, P.; Kumar, N.; Raghav, P. Identifying Psychological Antecedents and Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy through Machine Learning: A Cross Sectional Study among Chronic Disease Patients of Deprived Urban Neighbourhood, India. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease 2022, 92. [CrossRef]

- Seol, H.Y.; Shrestha, P.; Muth, J.F.; Wi, C.-I.; Sohn, S.; Ryu, E.; Park, M.; Ihrke, K.; Moon, S.; King, K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Clinical Decision Support for Childhood Asthma Management: A Randomized Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Alsaeed, K.A.S.; Almutairi, M.T.A.; Almutairi, S.M.D.; Nawmasi, M.S.A.; Alharby, N.A.; Alharbi, M.M.; Alazzmi, M.S.S.; Alsalman, A.H.; Alenazy, F.A.; Alfalaj, F.I. Artificial Intelligence and Predictive Analytics in Nursing Care: Advancing Decision-Making through Health Information Technology. Journal of Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 9308–9314. [CrossRef]

- Damar, M.; Yüksel, İ.; Çetinkol, A.E.; Aydın, Ö.; Küme, T. Advancements and Integration: A Comprehensive Review of Health Informatics and Its Diverse Subdomains with a Focus on Technological Trends. Health Technol. 2024, 14, 635–648. [CrossRef]

- Naskath, J.; Rajakumari, R.; Aldabbas, H.; Mustafa, Z. Computational Intelligence and Deep Learning in Health Informatics. In Computational Intelligence; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2024; pp. 189–211 ISBN 978-1-394-21425-9.

- Khamaj, A. AI-Enhanced Chatbot for Improving Healthcare Usability and Accessibility for Older Adults. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2025, 116, 202–213. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.W.; Ma, C.C. Application of AI in Addressing Challenges of Primary Healthcare in Hong Kong. In The Handbook of Primary Healthcare: The Case of Hong Kong; Fong, B.Y.F., Law, V.T.S., Lee, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 589–609 ISBN 978-981-96-0817-1.

- Razai, M.S.; Al-bedaery, R.; Bowen, L.; Yahia, R.; Chandrasekaran, L.; Oakeshott, P. Implementation Challenges of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Primary Care: Perspectives of General Practitioners in London UK. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0314196. [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Sharma, S. Medical Communication: Designing an Enhanced Health Care Chatbot for Instructive Conversations. AIP Conference Proceedings 2025, 3253, 030037. [CrossRef]

- Kidwai, B.; Rk, N. Design and Development of Diagnostic Chabot for Supporting Primary Health Care Systems.; 2020; Vol. 167, pp. 75–84.

- Nivedhitha, D.P.; Madhumitha, G.; Janani Sri, J.; Jayashree, S.; Surya, J.; Divya, D.M. Conversational AI for Healthcare to Improve Member Efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Management (ICSTEM); April 2024; pp. 1–6.

- Grant, P. The Rise of Virtual Primary Care. In The Virtual Hospital; Grant, P., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 55–70 ISBN 978-3-031-69944-3.

- Erazo, W.S.; Guerrero, G.P.; Betancourt, C.C.; Salazar, I.S. Chatbot Implementation to Collect Data on Possible COVID-19 Cases and Release the Pressure on the Primary Health Care System.; 2020; pp. 302–307.

- Olano-Espinosa, E.; Avila-Tomas, J.F.; Minue-Lorenzo, C.; Matilla-Pardo, B.; Serrano, M.E.S.; Martinez-Suberviola, F.J.; Gil-Conesa, M.; Del Cura-González, I.; Molina Alameda, L.; Andrade Rosa, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a Conversational Chatbot (Dejal@bot) for the Adult Population to Quit Smoking: Pragmatic, Multicenter, Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial in Primary Care. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Anmella, G.; Sanabra, M.; Primé-Tous, M.; Segú, X.; Cavero, M.; Morilla, I.; Grande, I.; Ruiz, V.; Mas, A.; Martín-Villalba, I.; et al. Vickybot, a Chatbot for Anxiety-Depressive Symptoms and Work-Related Burnout in Primary Care and Health Care Professionals: Development, Feasibility, and Potential Effectiveness Studies. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Diniz, C.S.; Chagas, B.A.; Mendes, M.S.; Prates, R.; Pagano, A.; Ferreira, T.C.; Moreira Alkmim, M.B.; Alves Oliveira, C.R.; Borges, I.N.; et al. Synchronous Teleconsultation and Monitoring Service Targeting COVID-19: Leveraging Insights for Postpandemic Health Care. JMIR Medical Informatics 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Schachner, T.; Keller, R.; Wangenheim, F.V. Artificial Intelligence-Based Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions: Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22. [CrossRef]

- de Arriba-Pérez, F.; García-Méndez, S.; González-Castaño, F.J.; Costa-Montenegro, E. Automatic Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Elderly People Using an Entertainment Chatbot with Natural Language Processing Capabilities. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sels, L.; Homan, S.; Ries, A.; Santhanam, P.; Scheerer, H.; Colla, M.; Vetter, S.; Seifritz, E.; Galatzer-Levy, I.; Kowatsch, T.; et al. SIMON: A Digital Protocol to Monitor and Predict Suicidal Ideation. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Junior, J.B.; Dias, L.; Figueiredo, L.J.; de Brito, L.F.C.; de Souza Abrão, T.M.; Bonfim, T.R. A chatbot proposal for tele orientation on breastfeeding. RISTI - Revista Iberica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informacao 2021, 2021, 357–363.

- Dogan, O.; Faruk Gurcan, O. Enhancing Hospital Services: Utilizing Chatbot Technology for Patient Inquiries. In Proceedings of the Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems; Kahraman, C., Cevik Onar, S., Cebi, S., Oztaysi, B., Tolga, A.C., Ucal Sari, I., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 233–239.

| Cluster Colour | Representative author's keywords (the number in parentheses represents the number of occurrences in publications) | Categories | Theme |

| Yellow (12 authors keywords) | Natural language processing (28); Dementia (13); Risk factors (9); Mild cognitive impairment (9) | Natural language processing of medical records for clinical decision support in dementia health care; Identification of risk factors for early detection of dementia, Alzheimer and mild cognitive impairment with natural language processing | Natural language processing and Clinical Decision Support System in dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and mild cognitive impairment |

| Green (19 authors keywords) | Machine learning (239); Electronic health records (47); Prediction (19); Risk prediction (13); Atrial fibrillation (13) | Use machine learning algorithms like support vector machines, random trees, decision trees, and logistic regression on electronic health records in cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and other chronic diseases; Machine learning in risk prediction and prediction in general; Improve patient safety with machine learning. | Optimizing health care and managing risk and patient safety in primary health with machine learning |

| Red (20 authors keywords) | Primary care (89); Primary health care (24); Depression (16); Classification (15); Supervised machine learning (8); Precision medicine (7); Mental health (7); Big data (7) | Using text mining and classification in primary, community, population, and mental health to improve social determinants; Supervised machine learning in primary health care delivery; Big data and data mining in primary care; precision medicine and depression. | Use of supervised learning and data/text mining to analyze primary health-based social determinants |

| Blue (13 author keywords) | Artificial intelligence (99); Deep learning (77); Diagnosing (29); Screening (23); Convolutional neural networks (18); Diabetic retinopathy (15); Telemedicine (8) | Artificial intelligence and deep learning in screening and diagnosing; Deep learning with convolutional networks in computer vision; Screening of diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma with deep learning; Use of artificial intelligence in telemedicine | Deep learning in screening and diagnosing |

| Violet (10 authors keywords) | COVID-19 (24); Public health (14), Telehealth (8); Epidemiology (8); Health informatics (7); | Covid 19 and Telehealth; Use of Health informatics in Epidemiology; Health informatics and Asthma | Health informatics in primary health |

| Light blue (9 authors keywords) | General practice (12); Suicide (8); Chatbot (5); NLP (5) | Chatbots in general practice in primary health; Chat boots and NLP | Chatbots in primary healthcare |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).