Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

17 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. History of Ambient Temperature Dried Meat Products

3. Ambient Temperature Dried Meat Products

3.1. Biltong

3.2. Droëwors

3.3. Pastrima

3.4. Charqui

3.5. Cecina

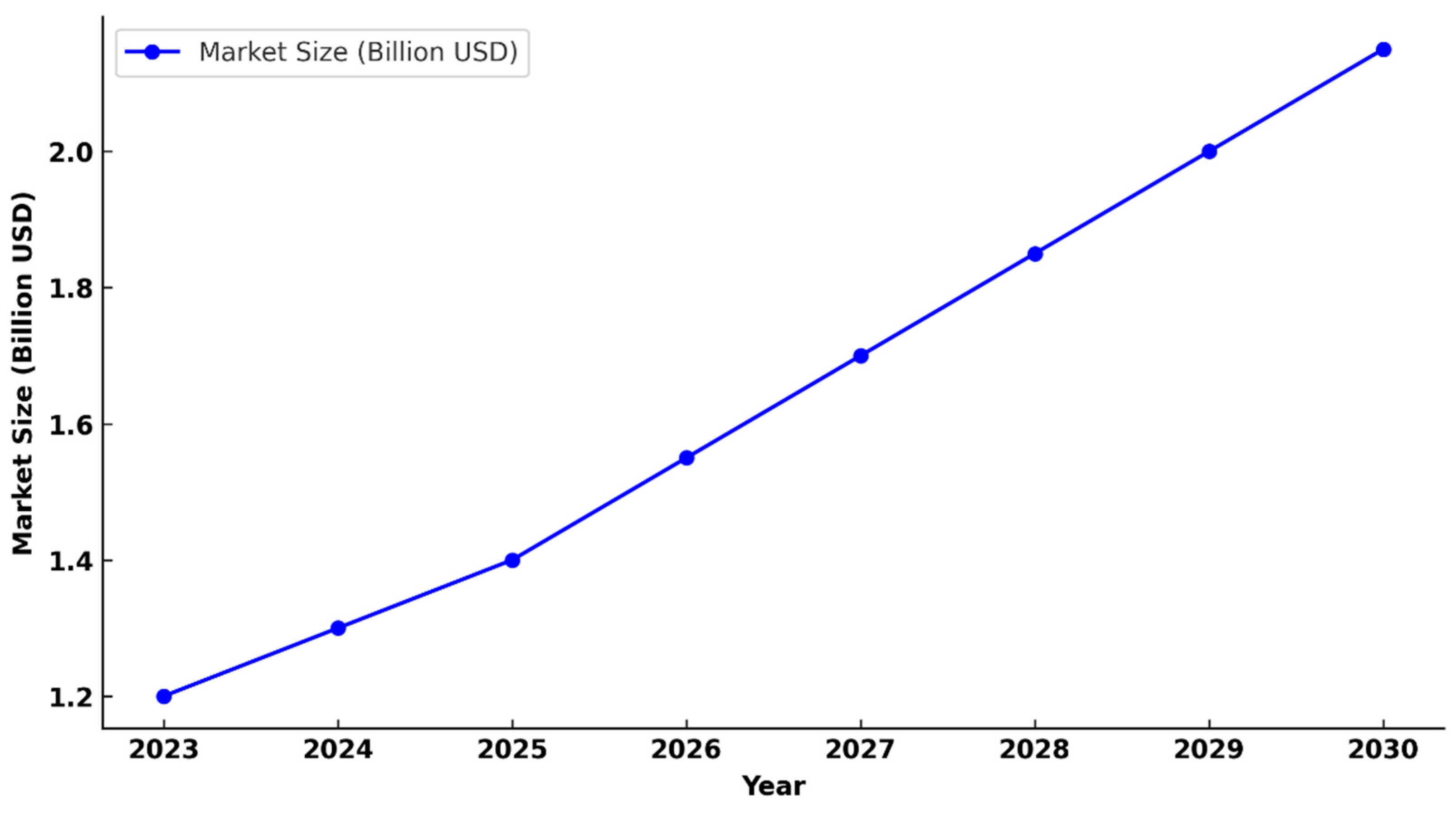

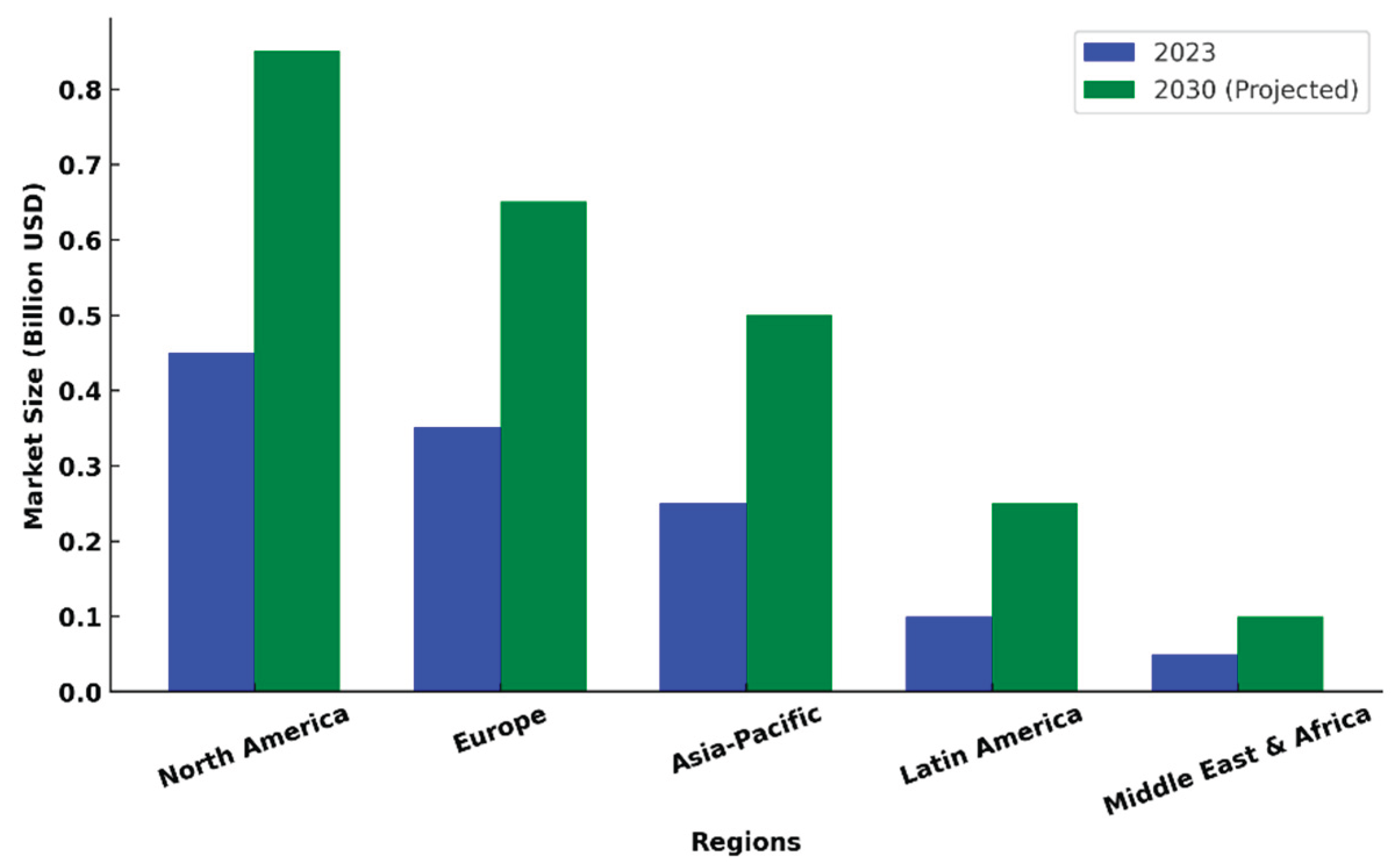

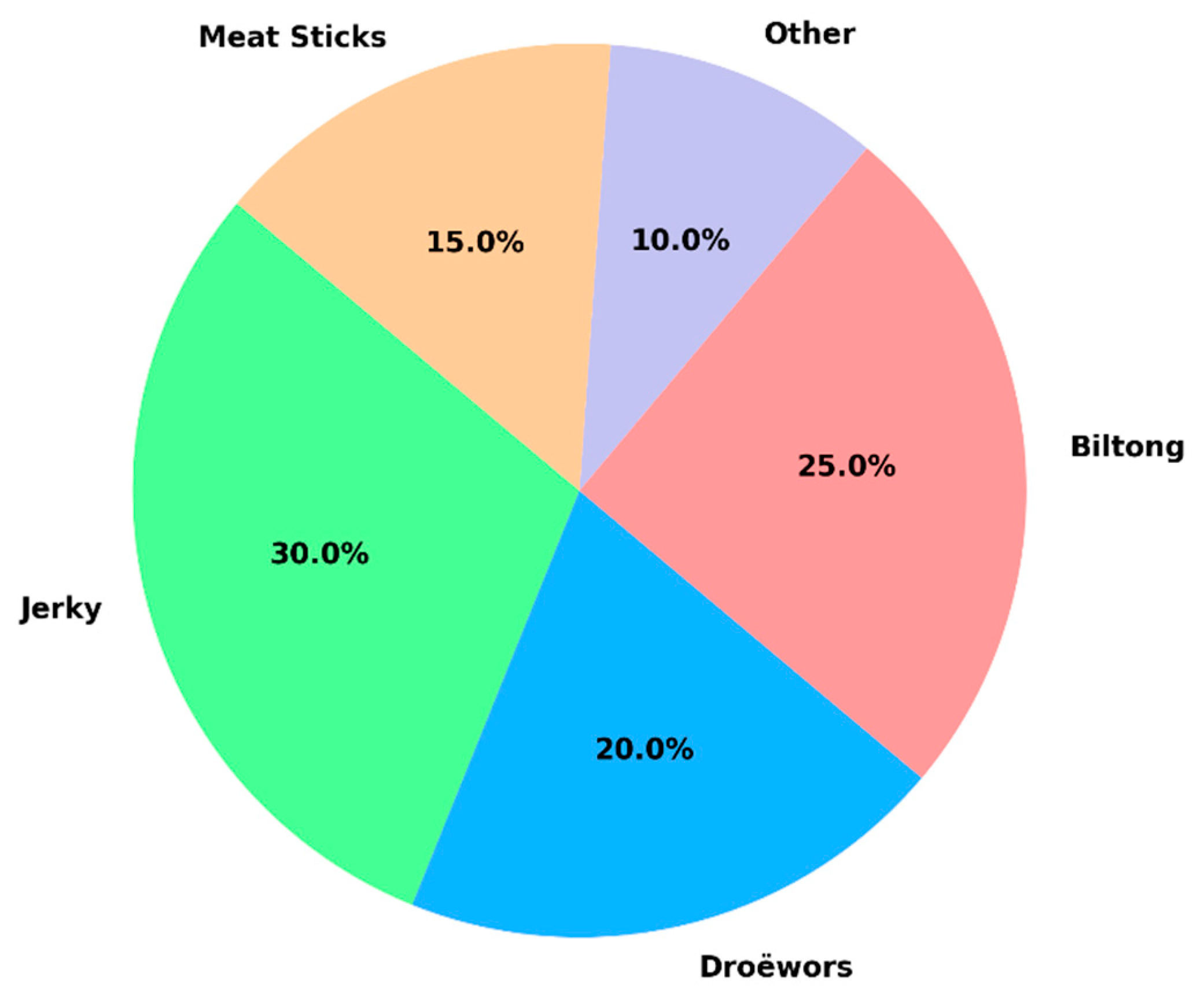

4. Market Trends for Ambient Temperature Dried Meat Products

5. Economic Importance of Ambient Temperature Dried Meat Products for Small Meat Processors.

6. Production Process of Biltong ad Droëwors

6.1. Biltong Production Ingredients

- Beef (or alternative meats such as game or ostrich)

- Coarse salt

- Vinegar (typically apple cider or malt vinegar)

- Coriander

- Black pepper

- Sugar (optional)

- Additional spices such as cloves or chili powder (optional)

6.1.1. Production Process

- Meat Selection & Trimming: High-quality lean cuts of meat, such as the silverside or topside, are selected and trimmed of excess fat to prevent rancidity during drying.

- Cutting into Strips: The meat is cut into long strips, usually about 1-2 inches thick, to allow for even drying.

- Marination: The strips are coated with coarse salt, vinegar, and spices to enhance flavor and aid in preservation. The vinegar lowers the pH, creating an unfavorable environment for bacterial growth.

- Resting/Absorption: The meat is left to marinate for several hours to allow the flavors and preservation agents to penetrate.

- Drying: The strips are hung in a well-ventilated area with controlled temperature and humidity. Traditional drying occurs at room temperature for 4-10 days, depending on environmental conditions.

- Packaging: Once the desired dryness is achieved, the biltong is sliced into smaller pieces and packaged in vacuum-sealed bags or moisture-resistant packaging.

- Storage & Distribution: The final product is stored at ambient temperature and distributed for sale.

6.2. Droëwors Production Ingredients

- Beef or lamb (or a mix)

- Beef fat (helps maintain texture and flavor)

- Coriander

- Vinegar

- Black pepper

- Salt

- Other optional spices like nutmeg or cloves

- Sausage casings (traditionally natural casings, but synthetic can be used)

6.2.1. Production Process

- I.

- Meat Selection & Trimming: Lean cuts of beef or lamb are selected and trimmed, with a small amount of fat retained for texture.

- II.

- Grinding & Mixing: The meat is ground and mixed with salt, spices, and vinegar improve preservation and enhance flavor.

- III.

- Stuffing into Casings: The seasoned meat is stuffed into natural or synthetic sausage casings, ensuring even distribution.

- IV.

- Hanging for Drying: The sausages are hung in a well-ventilated drying chamber or room.

- V.

- Drying at Controlled Temperature: Unlike biltong, which is dried in open air, droëwors is usually dried in a controlled environment with regulated humidity and temperature.

- VI.

- Packaging: Once dried to the desired consistency, the sausages are cut into smaller portions and vacuum-sealed.

- VII.

- Storage & Distribution: The final product is stored at ambient temperature and distributed through retail channels.

7. Food Safety Concerns Associated with the Ambient Temperature Dried Meat Products

- Lack of Heat Treatment: Traditional drying methods often omit a heat lethality step, relying solely on drying to reduce water activity. This approach may be insufficient to eliminate pathogens like Salmonella and E. coli O157:H7, which can survive in low-moisture environments [29].

- Ambient Temperature Drying: Drying at ambient temperatures without controlled conditions can allow pathogens to survive and potentially proliferate if the drying process is not adequately managed [29].

- Cross-Contamination: Improper handling during processing, such as cross-contamination from raw to finished products, can introduce pathogens [3].

- Inadequate Process Validation: Small-scale producers may lack the resources to conduct microbial challenge studies to validate their processes, leading to potential safety hazards [29].

8. Regulatory Compliance for Biltong and Droëwors Production in the U.S.

9. Microbial Safety of Biltong and Droëwors

9.1. Pathogen Presence and Survival

9.2. Baseline Microbial Reductions

9.3. Role of Salt, Vinegar and Drying Conditions in Pathogen Reduction

- Salt: Salt binds available water and lowers water activity (Aw), creating an osmotic stress for bacteria. Even a modest salt concentration in biltong (around 2% w/w in the meat) can significantly inhibit microbial growth once drying progresses. Interestingly, increasing salt beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns in lethality. Karolenko et al. (2020) varied the salt level in biltong marinade from 1.7% up to 2.7% and found no significant difference in Salmonella kill – all batches achieved >5.5-log reductions after 6 days of drying. This suggests that even the lowest salt level tested (1.7%) was sufficient to facilitate major pathogen decline when combined with vinegar and drying, and higher salt did not markedly improve the kill. In practice, a ≥2% salt content is common and effective for safety, while also keeping the product palatable [8].

- Vinegar (Acid): Vinegar (acetic acid) in the marinade lowers the meat surface pH and has direct bactericidal effects. Traditional recipes use vinegar (often malt, cider, or wine vinegar) sprayed or mixed with the spiced meat. The acidity is crucial for Salmonella and E. coli inactivation. Karolenko et al. tested different vinegar concentrations and found 2% vinegar (relative to meat weight) was insufficient – biltong with 2% vinegar did not quite reach a 5-log Salmonella reduction even after 8 days. In contrast, increasing vinegar to 3% or 4% accelerated the kill, achieving >5-log Salmonella reductions by day 7–8 (with no significant difference between 3% and 4%). Vinegar’s antimicrobial action is evidenced in vitro as well: Naidoo and Lindsay (2010) reported that full-strength (glacial) acetic acid could inhibit all test strains isolated from biltong, whereas household vinegars (diluted acetic acid, like apple cider or brown spirit vinegar) inhibited some but not all strains [3]. This indicates vinegar contributes to pathogen control, but typical marinade concentrations may be bacteriostatic rather than instantly bactericidal, especially against acid-tolerant organisms. Indeed, acid-adapted bacteria can better survive acidic marinades. Recent validation studies purposely used acid-adapted challenge cultures (grown in mildly acidic media) to ensure the biltong process can kill even acid-tolerant cells. The consensus is that a sufficiently acidic marinade (pH ~4) provides an important initial reduction and works in synergy with drying.

- Drying Time & Conditions: The drying step is ultimately the critical kill step in biltong and droëwors production. As moisture is removed, water activity drops below levels that support pathogen growth or toxin production (a critical safety threshold is aW < 0.85 for staphylococcal toxin prevention). Drying at ambient temperature (typically ~22–25 °C) and moderate humidity (50–60% RH) for several days will gradually inactivate pathogens. The rate of drying can influence how quickly pathogens are reduced. Higher drying temperatures (still far below cooking, but slightly warmer air) cause faster moisture loss – one study found that drying at 25 °C vs 22 °C (at constant 55% RH) led to a quicker drop in aW and achieved the target moisture loss a bit sooner. However, final safety is more tied to ultimate Aw than the exact drying schedule. In practice, biltong is often dried for 4–10 days until it is quite dry (aW ~0.6–0.8). Pathogen reductions tend to follow first-order decline with time until they reach an undetectable or injury phase. For example, Burnham et al. observed about 1–2 log reductions once biltong reached an intermediate aW ≈0.85, and around 2–3 log by the time aW ≈0.60 was achieved. If drying continues longer or product is stored dry, additional minor declines may occur (they noted a small further drop after an extra week of dry storage). It’s important that drying is uniform: thick pieces or the centers of droëwors sticks may retain higher internal aW even when the surface feels dry. Researchers emphasize measuring the internal water activity of biltong/droëwors, since the core can be less dry than the surface. Overall, the drying process creates a low-moisture, high-salt, acidic environment that is increasingly hostile to pathogens, and sufficient drying time is key to reaching the ≥5-log reduction mark.

10. Traditional vs. Modern Processing Methods and USDA-FSIS Compliance

10.1. Regulatory Requirements

10.2. Traditional Process Efficacy

10.3. Modern Process Enhancements

- Vacuum Tumbling Marination: Instead of static soaking, marinating the meat under vacuum while tumbling can drive the brine (vinegar and salt) into the tissue more effectively and uniformly. Karolenko et al., [8] used a 30-minute vacuum tumble in marinade as a “short marination” process, allowing them to start drying the same day. This yielded comparable or faster pathogen reductions than a long soak. In fact, a combined approach (brief vacuum tumble plus an overnight hold in marinade) achieved a full 5-log Salmonella reduction after only 4 days of drying – effectively shortening the required drying time. Vacuum tumbling ensures all surfaces see the marinade and likely causes some physical cell injury, enhancing lethality.

- Additional Antimicrobial Dips: Some processors introduce a pre-marination dipping step in a stronger antimicrobial solution (organic acid or other sanitizers) to knock down surface bacteria prior to drying. Karolenko et al., [8] evaluated dips such as acidified calcium sulfate (applied at a level equivalent to 5% or 10% lactic acid) and lactic acid solutions on inoculated beef strips. The results were dramatic: a dip adjusted to 10% lactic acid yielded >5-log Salmonella reduction in only 4 days of drying (and >6-log by 8 days). Even a milder 5% lactic acid dip achieved ~5-log in 6 days. By contrast, the no-dip control in that experiment (just the standard vinegar/salt marinade) took longer – around 8+ days – and some replicates just under 5-log reduction in that time. These findings echo Burnham et al.’s suggestions that a pre-treatment like a peracetic acid spray on the raw meat can dramatically reduce initial contamination and help meet the lethality standard . Modern recipes may also incorporate food-grade antimicrobials (e.g. sodium acid sulfate or potassium sorbate) into the marinade for an extra hurdle.

- Climate-Controlled Drying: Traditional biltong might be hung in ambient air (which can vary in temperature/humidity), but commercial production often uses drying cabinets or rooms where temperature and relative humidity are regulated. Maintaining ~50–60% RH is important – too high and drying is too slow (risking mold or survival), too low and the outside may case-harden before the inside dries. Studies have used chambers at 55% RH and found consistent results in pathogen decline. As noted, slightly elevating the air temperature (to the mid-20s °C) can speed drying without cooking the meat. Modern methods thus optimize drying parameters to reliably reach a safe A_w throughout the product in a reasonable timeframe. The use of drying chambers also allows uniform airflow and prevents fluctuating conditions that could occur if weather changes (a concern in true open-air drying).

10.4. Microbial Challenges Studies and Findings

11. Impact of Drying Techniques on Microbial Reduction

11.1. Ambient Air vs. Controlled Drying

11.2. Temperature and RH Regimens

11.3. Drying Whole Strips vs. Ground Sausage

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- R. Coetzee, “Spys en drank: Die oorsprong van die Suid-Afrikaanse eetkultuur,” C Struik Uitgewers Kaapstad South Afr., 1977.

- P. Strydom and B. Zondagh, “Biltong: A Major South African Ethnic Meat Product,” Encycl. Meat Sci., vol. 1, pp. 515–517, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Naidoo and D. Lindsay, “Pathogens associated with biltong product and their in vitro survival of hurdles used during production.,” Food Prot. Trends, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 532–538, 2010.

- M. Jones, E. Arnaud, P. Gouws, and L. C. Hoffman, “Processing of South African biltong – A review,” South Afr. J. Anim. Sci., vol. 47, no. 6, p. 743, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Karolenko, A. Bhusal, J. L. Nelson, and P. M. Muriana, “Processing of Biltong (Dried Beef) to Achieve USDA-FSIS 5-log Reduction of Salmonella without a Heat Lethality Step,” Microorganisms, vol. 8, no. 5, p. 791, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Van Tonder and W. Van Heerden, “Make your own biltong and droëwors, Illustrated edition,” Struik Cape Town, pp. 9–19, 1992.

- G. M. Burnham, D. J. Hanson, C. M. Koshick, and S. C. Ingham, “Death of Salmonella Serovars, Escherichia coli O157: H7, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes During the Drying of Meat: A Case Study Using Biltong and Droëwors,” J. Food Saf., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 198–209, May 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Karolenko, A. Bhusal, J. L. Nelson, and P. M. Muriana, “Processing of Biltong (Dried Beef) to Achieve USDA-FSIS 5-log Reduction of Salmonella without a Heat Lethality Step,” Microorganisms, vol. 8, no. 5, p. 791, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Nortjé, E. M. Buys, and A. Minnaar, “Effect of γ-irradiation on the sensory quality of moist beef biltong,” Meat Sci., vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 603–611, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Jay, M. J. Loessner, and D. A. Golden, Modern food microbiology. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Barbosa-Cánovas, A. J. Fontana Jr, S. J. Schmidt, and T. P. Labuza, Water activity in foods: fundamentals and applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- M. Flores, “Understanding the implications of current health trends on the aroma of wet and dry cured meat products,” Meat Sci., vol. 144, pp. 53–61, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Feiner, Meat products handbook: Practical science and technology, vol. 145. Elsevier, 2006.

- L. M. Prescott, J. P. Harley, and D. A. Klein, Microbiology. McGraw-Hill, 1999.

- Davidson, The Oxford companion to food. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- F. Toldrá and Y. H. Hui, Handbook of fermented meat and poultry. Wiley, 2021.

- L. Leistner, “Basic aspects of food preservation by hurdle technology,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 55, no. 1–3, pp. 181–186, Apr. 2000. [CrossRef]

- F. Toldrá, M. Reig, and M. C. Aristoy, “Advances in meat drying: Processing, safety, and quality.,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 122, pp. 36–50, 2022.

- Zion Market Reasearch, “Dehydrated Meat Product Market Size, Growth & Trends 2032,” Zion Market Reasearch, 2023.

- The Business Research Company, “Canned and Ambient Food Global Market Report 2024,” The Business Research Company, 2024.

- MarketsandMarkets, “Meat Snacks Market: Trends, Growth, and Forecasts.,” 2023.

- Grand View Research, “Global Meat Snacks Market Size, Share & Growth Report,” 2023.

- J, C. P, and C. A, “COVID-19 disruptions in the U.S. meat supply chain: Impacts and policy responses,” Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 55–72, 2021.

- J, H. R, and S. L, “Expanding small meat processing: USDA grants and loans in response to COVID-19,” J. Agric. Econ., vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 211–225, 2023.

- J. MacDonald, “Market concentration and competition in U.S. meatpacking,” USDA Economic Research Service Report, 2021.

- J. Lusk, G. Tonsor, and L. Schulz, “The economics of small meat processing: Challenges and opportunities,” Am. J. Agric. Econ., vol. 104, no. 3, pp. 789–806, 2022.

- USDA-FSIS, “FSIS Ready-to-Eat Fermented, Salt-Cured, and Dried Products Guideline (FSIS-GD-2023-0002).,” Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture., 2023.

- FSIS, “FSIS Cooking Guideline for Meat and Poultry Products (Revised Appendix A),” U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2021a.

- USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture., “Filling USDA-FSIS Food Safety ‘Knowledge Gaps’: The Safety of Ambient Temperature Air-Dried Beef (Droëwors),” 2023.

- FSIS, “Meat and Poultry Hazards and Controls Guide,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2023c.

- FSIS, “Food Safety Research Priorities & Studies,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2023d.

- K. Gavai, C. Karolenko, and P. M. Muriana, “Effect of Biltong Dried Beef Processing on the Reduction of Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and Staphylococcus aureus, and the Contribution of the Major Marinade Components,” Microorganisms, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 1308, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wilkinson, “The effect of acid adaptation on pathogenic bacteria used as challenge organisms for microbial validation of biltong processing,” Unpublished undergraduate thesis, Oklahoma State University, 2021.

- K. Naidoo and D. Lindsay, “Pathogens associated with biltong products and their in vitro survival of hurdles used during production,” Food Protection Trends, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 532–538, 2010.

- FSIS, “Beef Biltong recalled in Canada after testing finds Salmonella,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2024.. Available: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/recalls.

| Region | CAGR(%) | Project Growth Trend |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 6.5 | Steady growth driven by clean-label and organic meat snacks |

| Europe | 5.8 | Moderate growth with strong demand for specialty meat snacks |

| Asia Pacific | 9.2 | Fastest-growing region, fueled by increasing protein consumption |

| Latin America | 4.3 | Moderate growth due to urbanization and higher disposable incomes |

| Middle East & Africa | 3.8 | Slowest growth, with expansion in select premium markets |

| Product | Pathogen | Year | Location | Illnesses | Amount Recalled | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biltong | Salmonella | 2001 | USA | 6 | Not specified | [34] |

| Beef Biltong | Salmonella | 2024 | Canada | Not reported | Not specified | [35] |

| Jerky | E. coli O157:H7 | 1995 | USA | 9 | Not specified | [14] |

| Lebanon Bologna | E. coli O157:H7 | 2011 | USA | Not reported | Not specified | [14] |

| Italian-style Meats | Salmonella | 2021 | USA | 40 | Not specified | [14] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).