1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) remains a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men globally, with metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) representing an incurable stage despite sequential therapies including androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), next-generation androgen receptor (AR) inhibitors, taxane chemotherapies, and radioligand therapy (RLT, e.g., 177Lu-PSMA) [

1]. The transformative impact of immunotherapy seen in other malignancies has largely not extended to PCa [

2]. This refractoriness is primarily attributed to its immunologically “cold” tumor microenvironment (TME), characterized by poor T cell infiltration and low antigen presentation, rendering immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) largely ineffective for most patients [

3]. Although the autologous vaccine sipuleucel-T offered an early glimpse into immunotherapeutic possibilities, its modest benefits underscore the need for more potent strategies [

4].

T cell engagers (TCEs) have emerged as a powerful alternative. Typically designed as bispecific antibodies, TCEs simultaneously bind T cells (via CD3) and tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) on cancer cells. This forced synapse triggers direct, potent T cell mediated cytotoxicity, crucially bypassing the need for conventional T cell receptor recognition and antigen presentation on Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules [

5,

6]. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in PCa, where MHC downregulation is a common immune evasion tactic, allowing TCEs to potentially activate potent killing even within poorly immunogenic tumors [

7]. Initial efforts targeting Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) provided essential proof-of-concept for TCEs in PCa [

8] but also highlighted significant challenges regarding durability and toxicity. However, the field is rapidly advancing. Newer TCEs targeting other antigens like Six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1 (STEAP1) [

9] and Delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) [

10], often incorporating sophisticated engineering features, are showing increasingly promising clinical activity in refractory mCRPC.

This rapidly evolving landscape necessitates a timely synthesis and critical perspective. Therefore, this review aims to move beyond a mere compilation of trial data. We provide molecular insights into the diverse TCE strategies being employed against PCa (targeting PSMA, STEAP1, and DLL3), critically evaluate their associated clinical outcomes, and synthesize the lessons learned thus far. Our central argument is that while TCEs offer undeniable promise, transforming this potential into a robust and durable clinical reality for patients with advanced PCa requires strategically addressing inherent limitations through continuous innovation in molecular engineering and the implementation of evidence-based combination approaches.

Our narrative review begins with the fundamental mechanisms of TCE action and the innovative engineering approaches designed to harness their power while mitigating risks. We then progress through a critical examination of the evolving clinical landscape, analyzing trials targeting different antigens and evaluating their therapeutic value. Subsequently, we delve into the practical challenges of safety and toxicity management, com-pare TCEs against the existing standards of care, and culminate by outlining the crucial future directions—spanning novel targets, advanced constructs, biomarker development, and combination strategies—necessary to solidify the role of TCEs as a cornerstone of future PCa treatment and realize the potential argued herein.

2. Mechanism of Action and Novel Engineering Approaches of T-Cell Engagers

2.1. Mechanism of Action

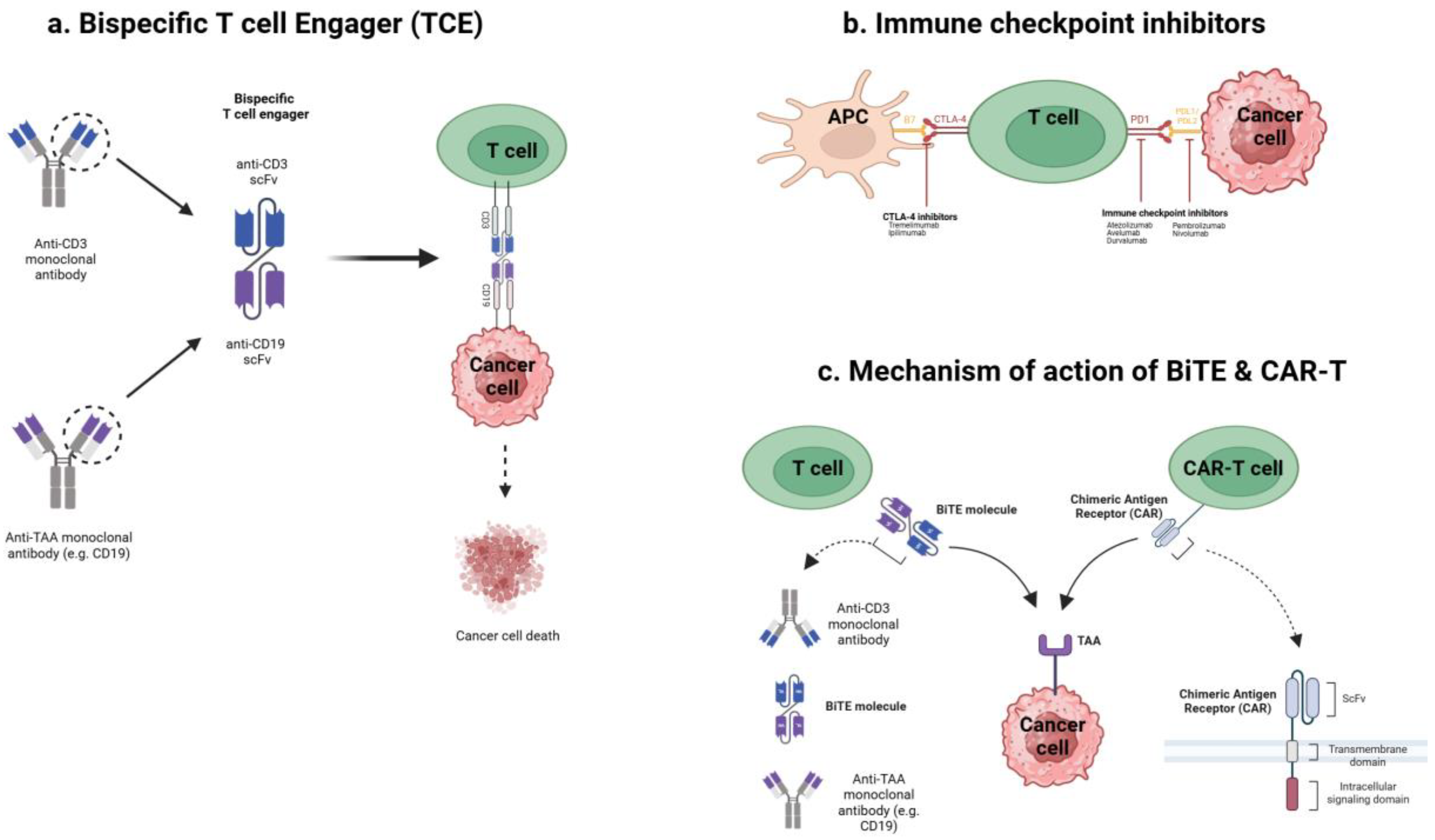

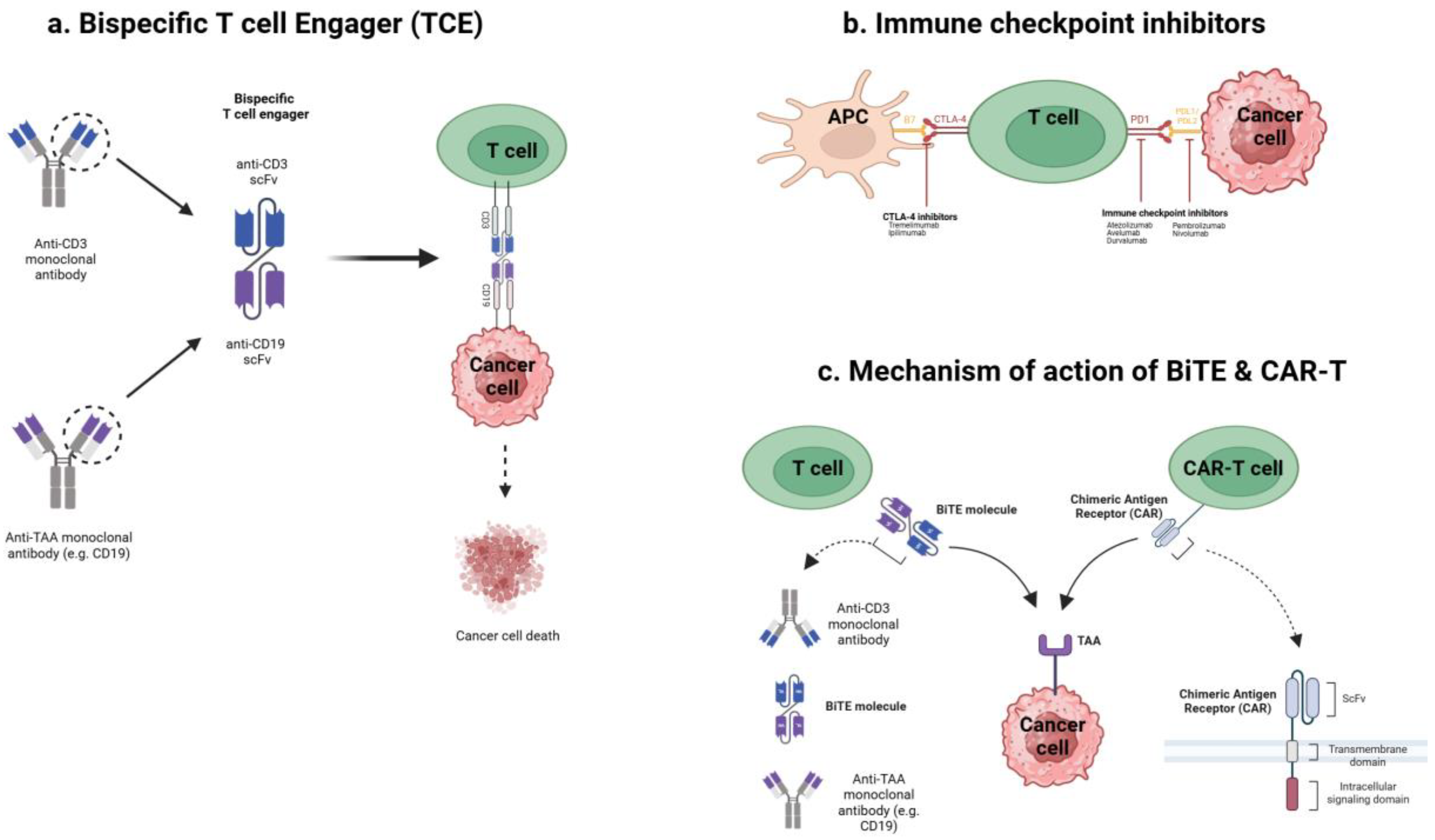

The fundamental mechanisms by which various T cell engaging cancer immunotherapies, including TCEs, ICIs, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, exert their effects are illustrated in

Figure 1.

TCEs are engineered proteins, typically bispecific antibodies, designed to simultaneously bind T cells and tumor cells. One arm recognizes CD3 on T cells, while the other binds a tumor-associated antigen (TAA) expressed on PCa cells. By forming this physical bridge, TCEs induce an artificial immune synapse, triggering T cell activation and directing cytotoxicity specifically towards the targeted tumor cells [

11,

12]. Crucially, this mechanism bypasses the requirement for peptide antigen presentation on MHC molecules for T cell recognition [

13]. Prostate tumors frequently downregulate MHC expression as an immune evasion tactic, thereby impairing conventional T cell responses [

7]. TCEs overcome this limitation by directly engaging T cells for MHC-independent tumor cell killing, effectively redirecting T cell activity based on target antigen presence.

Once engaged, activated T cells release cytotoxic molecules like perforin and granzymes, along with pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFα), Interleukin (IL)-6), at the tumor interface, leading to cancer cell lysis [

6,

8]. This process can potentially transform an immunologically ‘cold’ tumor microenvironment (TME) into an inflamed or ‘hot’ environment by promoting the influx and activation of T cells and cytokines locally. This mode of action distinctly differs from that of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which function by releasing inhibitory signals (e.g., Programmed cell Death protein 1 (PD-1)/Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade) on pre-existing T cells [

8]. Checkpoint blockade is effective only when tumor-specific T cells are already present within the TME. In PCa, where effector T cells are often scarce, releasing these “brakes” yields limited results for most patients [

8,

14]. In contrast, TCEs actively recruit and redirect T cells to the tumor, initiating an immune attack irrespective of pre-existing T cell specificity, thereby overcoming a key limitation of ICI therapy in this setting [

15].

Compared to therapeutic cancer vaccines aiming to prime de novo immunity over time, TCEs provide immediate effector function by co-opting the patient’s existing T cell repertoire. TCEs also differ from adoptive cell therapies using CAR T cells. Adoptive CAR-T cell therapy involves extracting, genetically engineering, and reinfusing patient T cells [

16]. While sharing the goal of redirecting T cells, TCEs are “off-the-shelf” pharmaceuticals, eliminating the need for personalized cell manufacturing and allowing for more accessible administration and dose adjustments. Furthermore, the effects of TCEs are pharmacologically reversible upon treatment cessation as the drug clears, whereas persistent CAR-T cells can lead to prolonged toxicity if severe adverse events occur. Early TCE formats (like the original BiTE® (Bispecific T cell Engager)) had a small size leading to rapid clearance, necessitating continuous infusion [

8]. Newer designs incorporate half-life extension strategies (e.g., Fragment crystallizable (Fc) fragments, albumin-binding domains), permitting intermittent dosing (weekly or biweekly) while maintaining T cell engagement and therapeutic effect [

17]. This has significantly improved the clinical practicality of TCE therapy for solid tumors. In summary, this distinct mechanism of action—redirecting a patient’s own T cells for immediate, targeted cytotoxicity—underpins the potential for TCEs to add a critical new dimension to the treatment paradigm for advanced PCa. However, this potent mechanism, relying on broad T cell activation, also carries inherent challenges, primarily concerning safety and pharmacokinetics.

2.2. Novel Engineering Approaches

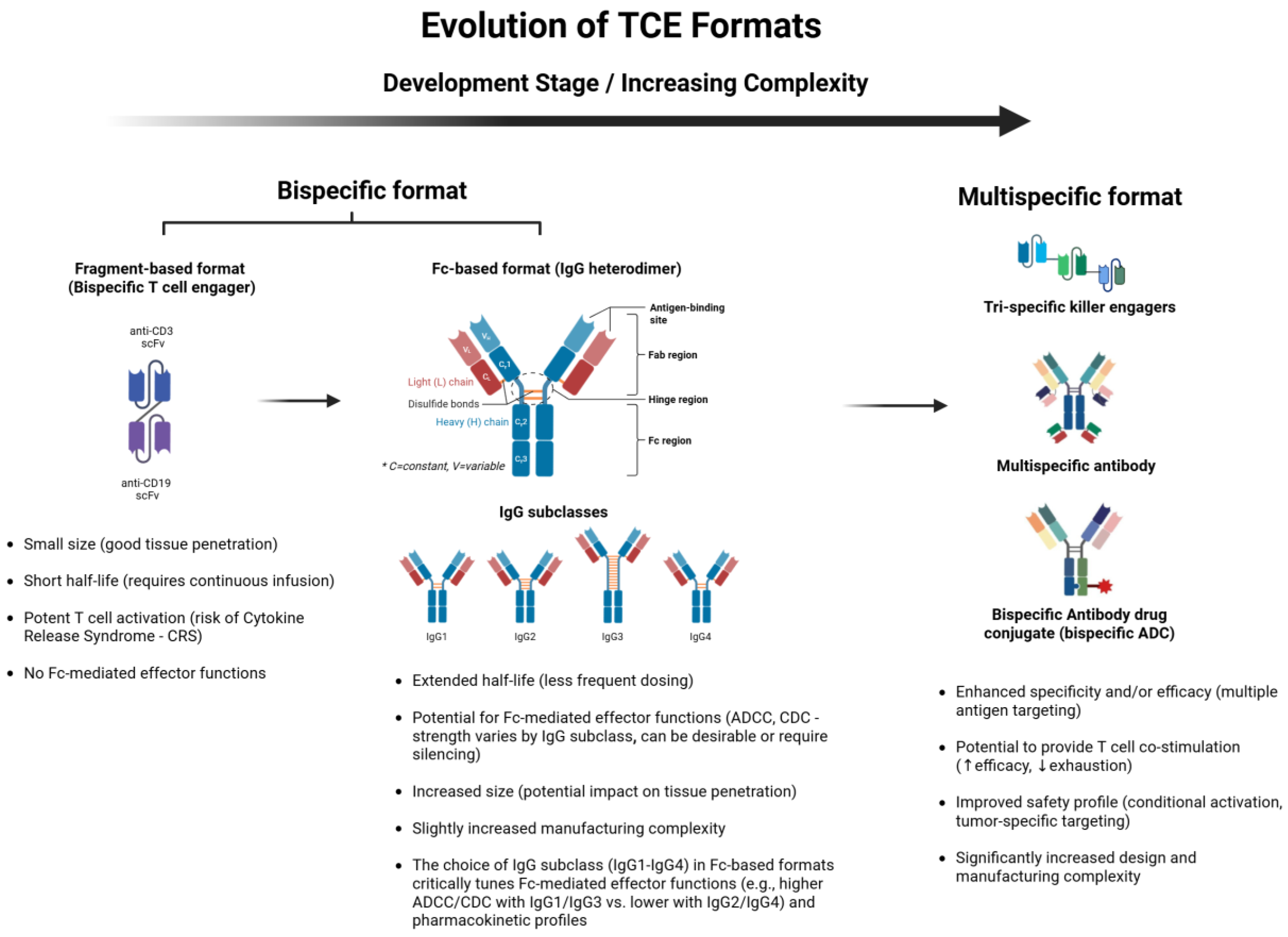

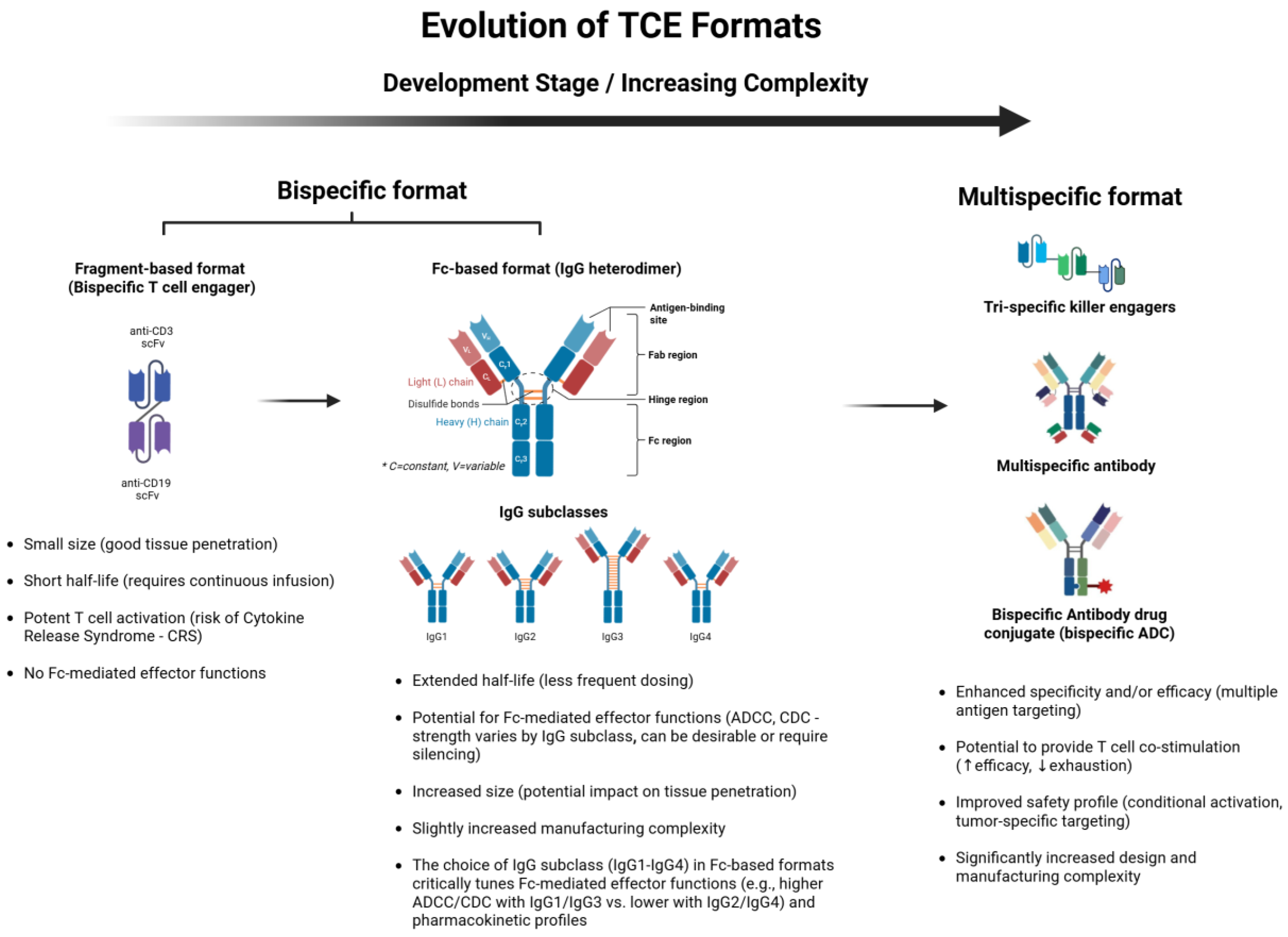

Addressing these intrinsic challenges became the primary driver for the sophisticated engineering approaches developed over the past decade. The evolution of these TCE formats, from simpler fragment-based constructs to more complex IgG-like and multispecific designs, is depicted in

Figure 2. Early TCEs, such as those based on the bispecific T cell engager (BiTE®) format, were typically small, Fc-free antibody fragments comprising two linked single-chain variable fragments (scFvs). While potent, their short circulating half-lives necessitated continuous infusion to maintain therapeutic levels [

8]. To overcome this significant practical limitation, numerous engineering strategies have emerged over the past decade [

18,

19]. These strategies aim to enhance pharmacokinetic properties, mitigate immunogenicity, and reduce safety risks like cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

Recent developments have focused primarily on two format types: immunoglobulin G (IgG)-like and fragment-based constructs. IgG-like formats incorporate engineered Fc domains, often featuring mutations to abrogate Fc receptor binding (silencing effector functions) while leveraging the FcRn interaction to extend circulating half-life, enabling intermittent dosing schedules [

17]. Prominent examples include “2+1” or “CrossMab” formats with two tumor antigen-binding arms and one CD3-targeting domain, employing technologies like “knob-into-hole” or other chain-pairing strategies to ensure correct assembly and enhance tumor selectivity [

20]. Alternatively, fragment-based constructs lacking an Fc domain may offer superior tumor penetration due to their smaller size, but often integrate albumin-binding domains or other moieties to prolong serum persistence [

21].

Affinity tuning represents another critical engineering advance [

22]. Modulating the binding affinities for CD3 and the tumor antigen allows for precise control over T cell activation, potentially confining potent activation primarily to the TME and thereby reducing systemic CRS risk. Furthermore, concepts like “masked” or prodrug-like TCEs, which remain systemically inert and are activated selectively within the tumor microenvironment (e.g., by tumor-associated proteases), are emerging as a means to significantly improve the safety profile [

18,

23]. Advanced multi-specific designs are also under investigation. These include tri specific constructs targeting multiple tumor antigens (to overcome heterogeneity or escape) or integrating costimulatory signals (e.g., targeting 4-1BB (CD137)) or cytokine moieties (e.g., IL-15) to provide synergistic effects by simultaneously addressing antigen escape and boosting immune activation or survival [

24,

25]. Collectively, these sophisticated engineering innovations are substantially advancing the clinical applicability and potential of TCEs, particularly for challenging solid tumors like PCa, by optimizing therapeutic potency, safety, and response durability.

3. Clinical Development and Therapeutic Value of TCEs for Prostate Cancer

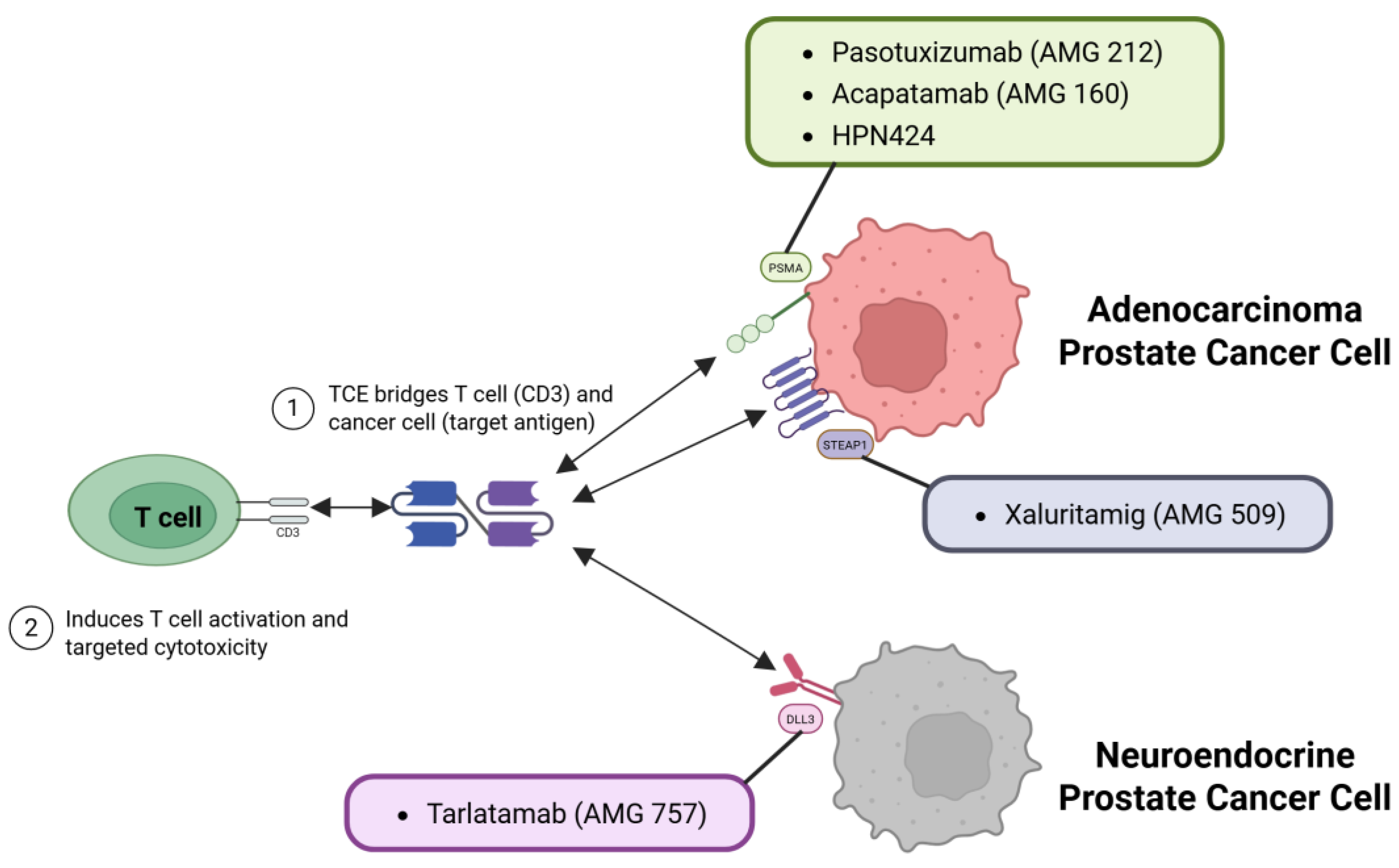

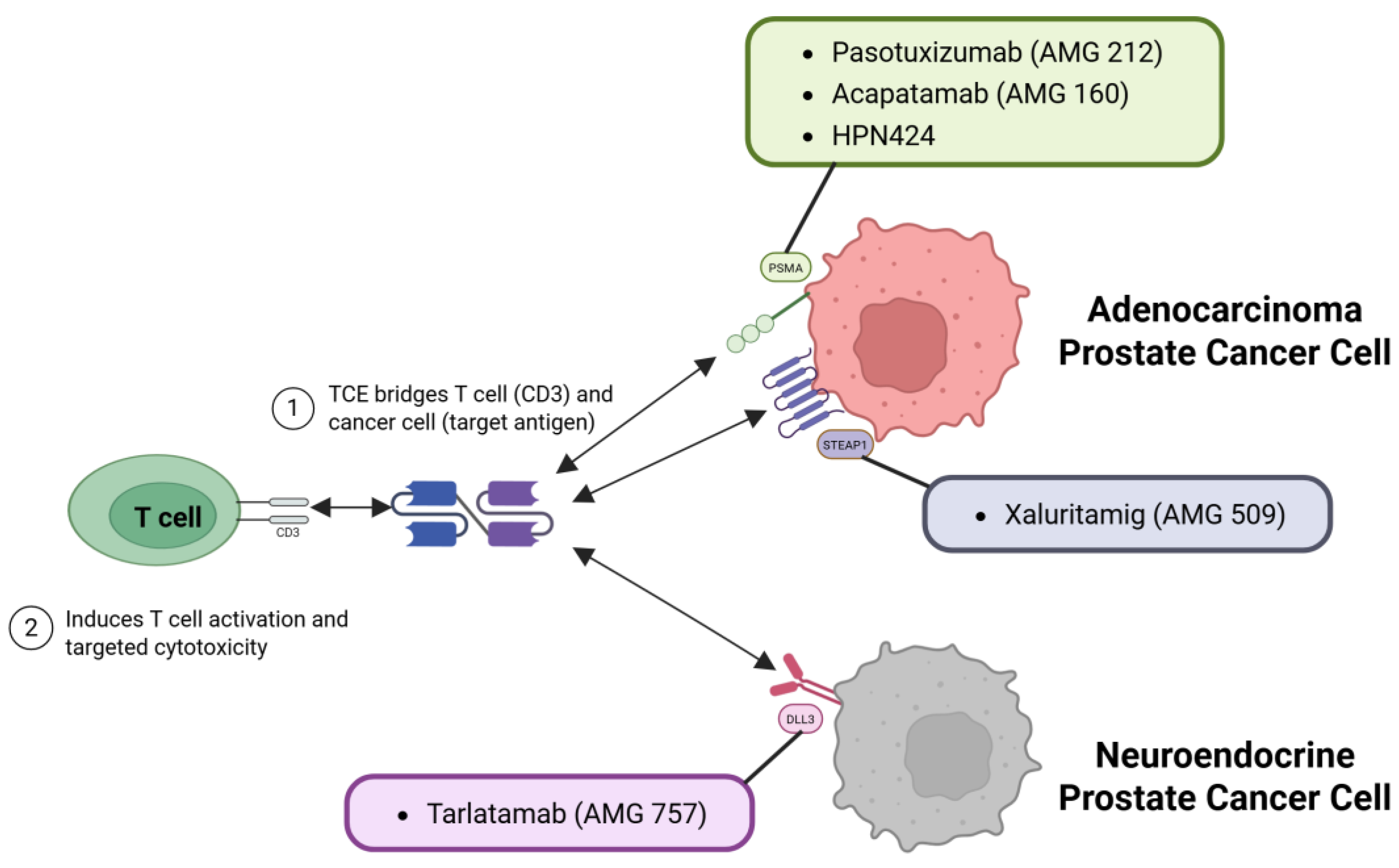

Multiple TCEs targeting PCa antigens have entered clinical trials with formats ranging from traditional BiTE molecules to tri specific T cell engagers (TriTEs) designed for greater stability and half-life.

Figure 3 illustrates how these TCEs mechanistically target distinct antigens, such as PSMA, STEAP1, and DLL3, present on different subtypes of PCa cells, including adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine PCa.

Table 2 summarizes the main TCEs currently in clinical development targeting PSMA, STEAP1, or DLL3 in advanced PCa. Early trials demonstrated that TCEs can induce prostate-specific antigen (PSA) decline and objective response rate (ORR) in patients with mCRPC who have exhausted conventional therapies, albeit with some challenges in tolerability and durability [

12,

26,

27].

3.1. Key Insights from Approved TCEs in Hematology

(TCEs approved for hematologic malignancies have rapidly re-shaped the treatment landscape, offering insights that can inform PCa immunotherapy. First, robust efficacy can be achieved in late-line heavily pretreated populations, underscoring the potency of redirecting a patient’s own T cells. Trials of agents such as blinatumomab [

28], glofitamab [

29], and teclistamab [

30] have demonstrated that response rates can exceed those of traditional chemotherapy in refractory settings, even producing durable remission in some patients. Second, the safety profiles of these agents highlight the critical role of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) monitoring and early intervention [

7,

17,

20,

31]. Although step-up dosing and tocilizumab prophylaxis effectively temper high-grade CRS, these protocols must be carefully tailored to the pharmacological features and disease context of each TCE. Third, antigen escape and downregulation remain frequent mechanisms of acquired resistance [

6,

8,

29,

32]; combining TCEs with other treatments (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors or alternative bispecific constructs) can potentially preserve long-term disease control [

33]. Finally, many TCEs have received accelerated or conditional approval based on clinically meaningful response rates in niche-refractory populations, demonstrating the regulatory path that new PCa-directed TCEs may follow. Although prostate tumors pre-sent a distinct immune environment relative to B-cell malignancies, hematological experience with approved TCEs provides a valuable blueprint for optimizing dosing regimens, toxicity management, and trial designs in solid tumor settings.

3.2. PSMA-targeting TCEs

PSMA, highly expressed on most PCa cells but with limited normal tissue distribution, became the initial primary target for TCE development in this disease [

34]. Early proof-of-concept was established by pasotuxizumab (AMG 212), a classic BiTE molecule [

8]. While demonstrating the potential for TCEs to induce >50% PSA declines in some mCRPC patients, its clinical utility was significantly hampered by a short half-life necessitating continuous infusion, notable immunogenicity, and importantly, a lack of durable responses [

8,

12,

17,

35]. These initial learnings directly spurred the development of second-generation PSMA TCEs engineered for extended half-lives and potentially improved tolerability.

Acapatamab (AMG 160), incorporating an IgG-like Fc domain, exemplified this next wave [

12]. In its Phase I trial, it showed promising pharmacokinetic profiles and achieved >50% PSA reduction in 63% of evaluable patients treated at higher doses [

12,

36]. However, this bio-chemical activity did not translate into high rates of objective radiographic response, highlighting a potential disconnect often observed in mCRPC trials and underscoring the need for further optimization, potentially in molecular design (e.g., CD3 affinity tuning) or patient selection beyond just PSMA presence. Cytokine release syndrome remained frequent, though reported as mostly manageable with mitigation strategies [

36].

Other approaches followed, such as HPN424, tri specific TCE targeting PSMA, CD3, and albumin for further half-life extension [

36]. Early Phase I data indicated modest activity, with only about 20% of patients showing any PSA decline and ~5-6% achieving a ≥50% reduction, although stable disease (SD) was noted in roughly half. While CRS was again prevalent, step-up dosing rendered it largely low-grade, reinforcing the importance of ad-ministration schedules [

36]. Collectively, these early-generation PSMA TCE trials, while validating the target and mechanism, revealed persistent hurdles in achieving deep and durable objective responses and consistently managing CRS without compromising efficacy. This context motivated exploration of novel constructs, such as the fully human CC-1, which showed encouraging early signals of universal PSA decline (up to 60%) with pre-dominantly mild CRS in a small Phase I cohort [

37], or targeting alternative immune effector cells, like LAVA-1207 engaging Vgamma9 Vdelta2 T cell receptor (Vγ9Vδ2) T cells [

38]. More crucially, these challenges also intensified interest in alternative TAAs, such as STEAP1.

While PSMA targeting provided critical initial validation, the quest for improved efficacy and strategies to overcome potential resistance mechanisms spurred the investigation of other promising antigens like STEAP1.

3.3. STEAP1-Targeting TCEs

STEAP1 emerged as another compelling TAA, given its overexpression in approximately 80–95% of metastatic PCa and minimal normal tissue expression [

9,

39]. The STEAP1-directed TCE AMG 509 (Xaluritamig) generated considerable excitement with its first-in-human trial results. In a Phase I study encompassing 97 heavily pretreated mCRPC patients, AMG 509 achieved a PSA50 response in 49% overall, rising to 59% in higher-dose cohorts, with 36% achieving ≥90% PSA reductions. Importantly, objective tumor responses per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria were observed in 24% (41% at high doses), including deep regressions in visceral sites [

19].

These efficacy figures, particularly the ORR, appear notably higher than those reported in many initial Phase I trials of PSMA-targeted TCEs, which often struggled to exceed 20% ORR [

40]. While direct cross-trial comparisons are inherently limited by patient heterogeneity and trial design, this apparent disparity warrants consideration. Potential contributing factors could include: (1) STEAP1’s potentially broader and more homogeneous expression across mCRPC lesions compared to PSMA in some populations, providing more consistent target availability [

41]; (2) superior molecular engineering or optimized binding affinities inherent to the Xaluritamig construct itself [

19]; or (3) differences in target biology, such as internalization kinetics or down-stream signaling upon TCE binding. Further investigation, including potential future head-to-head studies, is needed to dissect these possibilities.

The safety profile, while showing class-typical CRS in ~72% of patients, was deemed manageable [

19]. Critically, the low incidence of grade (G) ≥3 CRS (two cases) and treatment discontinuation due to CRS (3%) suggests that the implemented mitigation strategies (e.g., priming and step-up dosing) were particularly effective for this agent in this trial, offering a more favorable tolerability signal than some earlier TCE experiences. Although anti-drug antibodies (ADA) were detected, their lack of correlation with efficacy suggests responses occurred rapidly, prior to significant ADA interference [

19]. These robust early data, representing a potential step-change in TCE efficacy for PCa, have justifiably propelled AMG 509 towards pivotal Phase III evaluation [

42].

Beyond the common adenocarcinoma histology, a subset of advanced PCa exhibits neuroendocrine features, presenting distinct therapeutic challenges and necessitating novel targets such as DLL3.

3.4. Delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3)-Targeting TCEs in Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer

A subset of advanced PCa can undergo neuroendocrine differentiation, either de novo or as a result of the evolution of treatment-resistant mCRPC [

16]. Neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) typically lose androgen receptor expression and PSA production, behave aggressively, and have a poor prognosis [

16]. DLL3 is a cell surface protein expressed in neuroendocrine tumors (notably small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and NEPC) but not in normal adult tissues, making it an ideal immunotherapeutic target in this context [

16,

43]. Tarlatamab (AMG 757) is a Half-Life Extended (HLE) BiTE® that targets DLL3 in tumor cells and CD3 in T cells. It was first developed for small-cell lung cancer and has shown anti-tumor activity [

10]; it has recently been tested in NEPC [

16]. In a Phase I trial presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2024, patients with NEPC (either treatment-emergent or de novo NEPC with genomic loss of TP53, RB1, or PTEN) received tarlatamab at doses up to 100mg intravenously (IV) every 2 weeks (Q2weeks). The efficacy in this PCa cohort was modest but notable given the refractory setting [

16]. The ORR was 10.5% and 22.2% among the subsets of patients with DLL3-positive tumors. DLL3-positivity was defined as ≥1% expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC); about 56% of patients met this low threshold) Most of the responses were partial and not particularly durable. The median treatment duration was only 1.4 months in the overall cohort, indicating that many patients progressed early, whereas responders in the DLL3-high group had a median response duration of ~7.3 months. However, one patient had an exceptionally long-lasting response lasting beyond 2 years, illustrating that profound and durable remission is possible in principle. Investigators suggest that better patient selection may improve outcomes, as treating patients with low or negative DLL3 expression likely diluted the overall efficacy results. In terms of safety, the NEPC tarlatamab study recorded CRS in 75% of patients (mostly grade 1–2, only a single grade ≥3 case) and a low incidence of neurotoxicity (12.5%, with one grade 3 event). These toxicities are reminiscent of experiences in small cell lung cancer and appear manageable with appropriate precautions [

16]. While the activity of DLL3 TCEs in NEPC has yet to reach the high response rates seen with other targeted agents in different settings, this trial provided proof of concept that T cell redirection can target an aggressive variant of PCa that is otherwise extremely difficult to treat. Ongoing efforts will likely refine this approach (e.g., by requiring higher DLL3 expression or combining it with other therapies) to increase its impact. Given the lack of options for NEPC, identifying a subset of patients benefiting from it (as seen here) is a meaningful step forward.

3.5. Emerging Efficacy Landscape and Intrinsic Therapeutic Value of TCEs in mCRPC

Synthesizing the early clinical data presented for TCEs targeting PSMA, STEAP1, and DLL3 (

Table 2), a compelling picture emerges: T cell engagers possess the intrinsic capability to elicit meaningful anti-tumor activity in heavily pretreated mCRPC patients, a population often refractory to standard therapies. Biochemical responses (PSA declines ≥50%) have been consistently observed across various constructs, ranging roughly from 20% to over 60% in specific cohorts [

8,

12,

19]. Crucially, objective tumor responses (ORR according to RECIST) have also been documented, with rates spanning from approximately 10% in some initial PSMA trials to encouraging figures exceeding 40% in higher-dose cohorts of the STEAP1-targeting Xaluritamig study [

12,

19].

While these early results must be interpreted with caution—stemming largely from non-randomized Phase I trials with inherent patient heterogeneity and often limited follow-up—the ability to achieve objective regressions, including in visceral sites, via an off-the-shelf immunotherapy represents a significant potential advance in the ‘immune-cold’ landscape of PCa. This activity, driven by direct T cell redirection independent of MHC presentation [

5], offers a unique mechanistic advantage where conventional immunotherapies like ICIs have largely failed outside niche populations [

44]. The higher response rates suggested by the STEAP1-targeted approach compared to some initial PSMA TCEs (though direct comparisons are premature) hint at the critical influence of target selection [

15] and potentially optimized molecular engineering [

45] on clinical outcomes.

However, realizing the full therapeutic value of TCEs necessitates confronting key challenges highlighted by these initial studies. Foremost among these is the question of response durability [

6]. While some patients experience prolonged disease control, early relapse or primary resistance remains common, likely driven by factors such as antigen loss or T cell exhaustion that require further investigation and specific counter-strategies [

6,

46]. Furthermore, optimal patient selection remains a critical unmet need. While target antigen expression (via PET or IHC) is a prerequisite, the ideal expression threshold, the predictive value of antigen density, and the influence of the tumor microenvironment (e.g., baseline T cell infiltration, immunosuppressive factors) on TCE efficacy are still poorly understood [

47]. The modest activity of tarlatamab in a broadly defined DLL3-positive NEPC population [

48] underscores that simply identifying the target antigen may be insufficient for predicting meaningful benefit.

In essence, the current evidence provides strong proof-of-concept for the therapeutic value of TCEs in mCRPC, demonstrating their ability to induce responses in refractory disease. Yet, variability in efficacy across agents and targets, unanswered questions about durability, and the need for refined predictive biomarkers clearly indicate that significant work remains to translate this potential into consistent, long-term clinical benefit. Understanding how this unique therapeutic modality compares and integrates with established treatments is the next critical step.

4. Safety and Toxicity Mitigation Strategies

The promising anti-tumor activity highlighted in the previous section can only be translated into true clinical benefit if the associated toxicities, inherent to potent T cell activation, are effectively managed.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity (Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS)) are major challenges [

49]. Although TCEs offer a powerful therapeutic strategy, their administration is often associated with significant adverse events, including CRS, ICANS, and immunogenic complications, requiring robust safety measures. CRS results from extensive T cell activation and the subsequent release of cytokines such as IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1, leading to clinical manifestations including fever, hypotension, hypoxia, and organ dysfunction [

49,

50]. The risk of CRS correlates with tumor burden, dosage, and CD3 binding affinity of the TCE construct; thus, patients with widespread metastatic PCa lesions are particularly susceptible at therapy initiation. To address this, step-up dosing regimens involving initial low-dose priming followed by incremental increases are used to effectively reduce cytokine surges. Pharmacological interventions, such as tocilizumab, corticosteroids, and IL-1 inhibitors like anakinra, are frequently employed at early CRS onset, significantly mitigating progression to severe presentations [

49,

51]. ICANS poses an additional risk, characterized by symptoms ranging from mild encephalopathy and confusion to severe seizures and focal neurological deficits. Vigilant neurological monitoring and prompt initiation of high-dose corticosteroids are critical for managing moderate-to-severe cases [

17], and temporary suspension or discontinuation of TCE therapy may be necessary if symptoms persist or worsen. Historically, ADA has limited the efficacy of early-generation TCEs, often due to insufficient humanization, resulting in shortened half-lives and reduced therapeutic potency [

52]. Modern TCE designs leverage human or humanized frameworks with engineered variable regions, thereby significantly reducing the number of immunogenic epitopes. Additionally, intermittent dosing regimens, rather than continuous infusion, further reduce immunogenic responses [

53]. Off-tumor toxicity is addressed primarily by selecting prostate-specific antigens, such as PSMA and STEAP1, to minimize risks to non-prostate tissues [

39]. However, low antigen expression in normal tissues requires careful monitoring. Advanced mitigation includes the development of masked or prodrug TCE constructs that are selectively activated within the TME, further lowering the risk of off-target effects [

18,

54]. Combination strategies involving TCEs may increase efficacy but carry an increased risk of CRS and immune-mediated adverse events [

17]. Protocols often incorporate sequential approaches, initially employing cytoreductive treatments such as RLT to reduce tumor burden before introducing TCEs, thus minimizing the magnitude of cytokine release. Close monitoring through laboratory evaluations, including cytokine profiles, complete blood counts, and coordinated multidisciplinary care involving oncology, hospital medicine, and critical care units ensures early detection and effective management of immune-related toxicities. With the continued clinical integration of TCE therapy in advanced PCa, refined step-up dosing regimens, proactive pharmacological interventions, improved immunogenicity profiles, and precision-targeting technologies promise a progressively safer therapeutic landscape.

With optimized dosing regimens and proactive management protocols increasingly demonstrating the feasibility of mitigating major toxicities like CRS, the question then becomes how TCEs, with their distinct efficacy and safety profiles, compare and potentially integrate with the existing therapeutic landscape for advanced PCa.

5. Comparison with Existing Therapies

Having established the potential efficacy, intrinsic value, and key challenges of TCEs based on early clinical evidence, it is crucial to position this novel therapeutic class within the existing treatment landscape for advanced PCa. TCEs offer distinct mechanisms, efficacy profiles, and toxicity considerations compared to established modalities, as summarized in

Table 1. Understanding these differences is essential for determining their optimal role and integration into future treatment algorithms.

Comparison with Androgen Receptor (AR)-Targeted Agents: TCEs provide an AR-independent mechanism, crucial for patients progressing on agents like enzalutamide or abiraterone [

55]. Potential synergy exists, as AR modulation may alter PSMA expression [

56], but TCEs fundamentally bypass AR resistance pathways. Toxicity profiles differ significantly (immune-mediated for TCEs vs. metabolic/fatigue for AR agents) [

57].

Comparison with Chemotherapy (Taxanes): Chemotherapy offers broad cytotoxicity but significant systemic toxicities (myelosuppression, neuropathy). In contrast, TCEs in-duce targeted T cell killing but bring CRS/ICANS risks. While cross-trial comparisons are difficult, some early TCE data (particularly STEAP1-targeted) show ORR in late-line settings that appear competitive with or potentially exceed those historically reported for third-line cabazitaxel (~10-20% ORR) [

19,

58]. However, chemotherapy benefits are often transient, and TCE durability remains under investigation. Pre-TCE cytoreduction with chemo to potentially lower CRS risk is an area of interest [

59].

Comparison with Radioligand Therapy (177Lu-PSMA-617): Both require PSMA ex-pression (for PSMA TCEs/RLT). RLT delivers targeted radiation, has proven survival benefits in Phase III, and has distinct toxicities (hematologic, xerostomia) [

60]. Early TCE trials (e.g., Xaluritamig targeting STEAP1, potentially relevant for PSMA-low patients [

9,

19]) suggest ORRs that might rival the ~30% ORR seen in VISION [

60], although TCE data are less mature. Furthermore, potential resistance mechanisms differ (radiation vs. immune escape) [

53,

61]. Sequential or combination approaches are highly anticipated but require careful study regarding feasibility and additive toxicity.

Comparison with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): Unlike ICIs, which are largely ineffective in unselected mCRPC due to the ‘cold’ TME [

62], TCEs actively redirect T cells, bypassing the need for pre-existing anti-tumor immunity required for ICI efficacy [

11]. Their mechanisms are thus complementary, raising significant interest in combination strategies to potentially sustain TCE-activated T cell function [

11]. Toxicity profiles are both immune-related but manifest differently (e.g., CRS is unique to TCEs/CAR-T) [

17,

63].

Comparison with Sipuleucel-T: Relative to Sipuleucel-T, which aims to prime an immune response over time with modest survival benefit and minimal PSA impact [

4,

64], TCEs induce immediate, direct cytotoxicity via pre-existing T cells [

65]. They represent fundamentally different immunotherapeutic approaches in terms of mechanism, potency, and kinetics.

Table 1.

Comparison of TCE Therapy with Key Existing Treatments for Advanced Prostate Cancer.

Table 1.

Comparison of TCE Therapy with Key Existing Treatments for Advanced Prostate Cancer.

| Therapy |

Mechanism |

Typical Efficacy in Late-Line mCRPC |

Key Toxicities |

Potential Synergy or Considerations |

References |

| AR-Targeted (e.g., enzalutamide, abiraterone) |

Block androgen receptor signaling; efficacy loss in AR-independent disease |

PSA50 ~30–40% (earlier lines); less effective later |

Fatigue, metabolic disturbances (e.g., hypertension w/ abiraterone) |

May upregulate PSMA expression, potentially enhancing TCE activity |

[55,56] |

| Chemotherapy (e.g., docetaxel, cabazitaxel) |

Direct cytotoxicity to dividing cells (non-tumor-specific) |

~35% PSA50, ORR ~10-20% (heavily pretreated); OS benefit |

Myelosuppression, neuropathy, alopecia |

Cytoreduction prior to TCE might lower tumor burden and reduce CRS risk |

[1] |

| Radioligand (177Lu-PSMA-617) |

Delivers targeted radiation to PSMA-expressing cells |

PSA50 ~46%, ORR ~30% (VISION trial); survival benefit |

Hematologic toxicity, xerostomia, potential renal impact |

Requires PSMA+; sequential/combination w/ TCE under investigation |

[6,31,47,60] |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) |

Blocks PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 to restore T cell function |

Low response (<5-10% ORR) in unselected mCRPC; higher in MSI-H/dMMR/CDK12mut |

Immune-related AEs (pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis) |

May reduce T cell exhaustion, thus enhancing TCE efficacy |

[1,14] |

| Sipuleucel-T (autologous vaccine) |

Autologous APC vaccine targeting prostatic acid phosphatase |

Modest OS gain (~4 mo); low PSA50 rate |

Infusion reactions, flu-like symptoms |

Could be combined or sequenced with TCE for potential additive immune activation |

[4,64] |

| T cell Engagers (e.g., PSMAxCD3, STEAP1xCD3) |

Redirect T cells to tumor antigens (CD3×TAA), MHC-independent |

Phase I data: PSA50 ~20-60%, ORR ~10-40%+ (agent/target dependent) |

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity (ICANS), potential off-target effects |

Novel MOA bypassing resistance; combinations under study |

[5,6,19,40] |

Table 2.

Major TCE Agents Targeting PSMA, STEAP1, and DLL3 in Clinical Trials.

Table 2.

Major TCE Agents Targeting PSMA, STEAP1, and DLL3 in Clinical Trials.

| TCE Name, Developer |

Target Antigen |

Format / Key Features |

Clinical Stage (Phase) |

Key Efficacy Results |

Key Toxicities |

References |

| Pasotuximab (AMG 212), Amgen |

PSMA |

BiTE (small Fc-free) |

Phase I (completed) |

>50% PSA decline in some pts; Limited ORR & durability |

Frequent CRS (various grades), immunogenicity |

[8] |

| Acapatamab (AMG 160), Amgen |

PSMA |

IgG-like, extended half-life |

Phase I (Ongoing/Reported) |

PSA50 ~63% (evaluable pts, higher doses); Modest ORR reported |

CRS common (~high %), mostly G1-2 w/ mitigation; Low rate G≥3 |

[40] |

| HPN424, Harpoon Therapeutics |

PSMA |

Tri-specific (PSMA×CD3×albumin) |

Phase I (Ongoing/Reported) |

~20% had any PSA decline; ~5-6% PSA50; SD in ~50% |

Mostly G1-2 CRS with step-up dosing |

[21] |

| CC-1 (Fully Human) |

PSMA |

Fully human bispecific (CD3×PSMA) |

Phase I (Reported) |

PSA decline up to 60% in all 14 pts (early data) |

CRS common (~79%), mostly G1-2; No severe events reported |

[37] |

| Xaluritamig (AMG 509), Amgen |

STEAP1 |

IgG-based TCE |

Phase I (Reported; Ph III Planned) |

PSA50 ~49% (overall), 59% (high dose); ORR 24% (overall), 41% (high dose) |

CRS ~72% (mostly G1-2, 2 G3 cases); Fatigue, myalgia; Manageable immunogenicity |

[19] |

| Tarlatamab (AMG 757), Amgen |

DLL3 |

BiTE-like (CD3×DLL3) |

Phase I (NEPC Cohort Reported) |

NEPC Cohort: ORR 10.5% (overall), 22.2% (DLL3+ subset); One durable response >2yrs |

CRS 75% (mostly G1-2, one G≥3); Neurotoxicity ~12.5% (one G3) |

[10] |

| NJ-78278343, Janssen |

KLK2 (kallikrein-2) |

Bispecific antibody (CD3×KLK2) |

Phase I / II (ongoing) |

Early data pending |

Data pending reporting |

[66] |

| LAVA-1207, LAVA Therapeutics |

PSMA |

Vγ9Vδ2 T cell engager |

Phase I/II (Ongoing) |

Early signals of stable disease reported; data maturing |

Generally mild AEs reported; Low CRS incidence |

[38] |

In summary, TCEs occupy a unique position. They offer potent, targeted immuno-therapy for a historically ‘immune-cold’ tumor, acting independently of AR signaling and conventional MHC presentation. Their efficacy signals in heavily pretreated patients ap-pear promising relative to some existing options, particularly chemotherapy in later lines, although data maturity and durability remain key considerations. Crucially, their distinct mechanism and non-cross-resistance profile suggest significant potential for integration—either sequentially or concurrently—with AR therapies, chemotherapy, or RLT. However, their unique immune-mediated toxicities necessitate specialized management. Defining the optimal place for TCEs—whether as salvage therapy, sequenced with RLT, combined with ICIs, or even moved into earlier disease settings—will depend on results from ongoing and future randomized controlled trials that directly compare these strategies. Nevertheless, their demonstrated ability to generate objective responses where other immunotherapies have faltered strongly positions TCEs as a likely future pillar in the management of advanced PCa. However, this comparison also underscores that TCEs are unlikely to be a universal solution alone. Addressing challenges like durability and reaching broader patient populations necessitates exploring how to best integrate their unique strengths with other modalities, paving the way for the future research directions discussed next.

6. Future Directions and Research Priorities

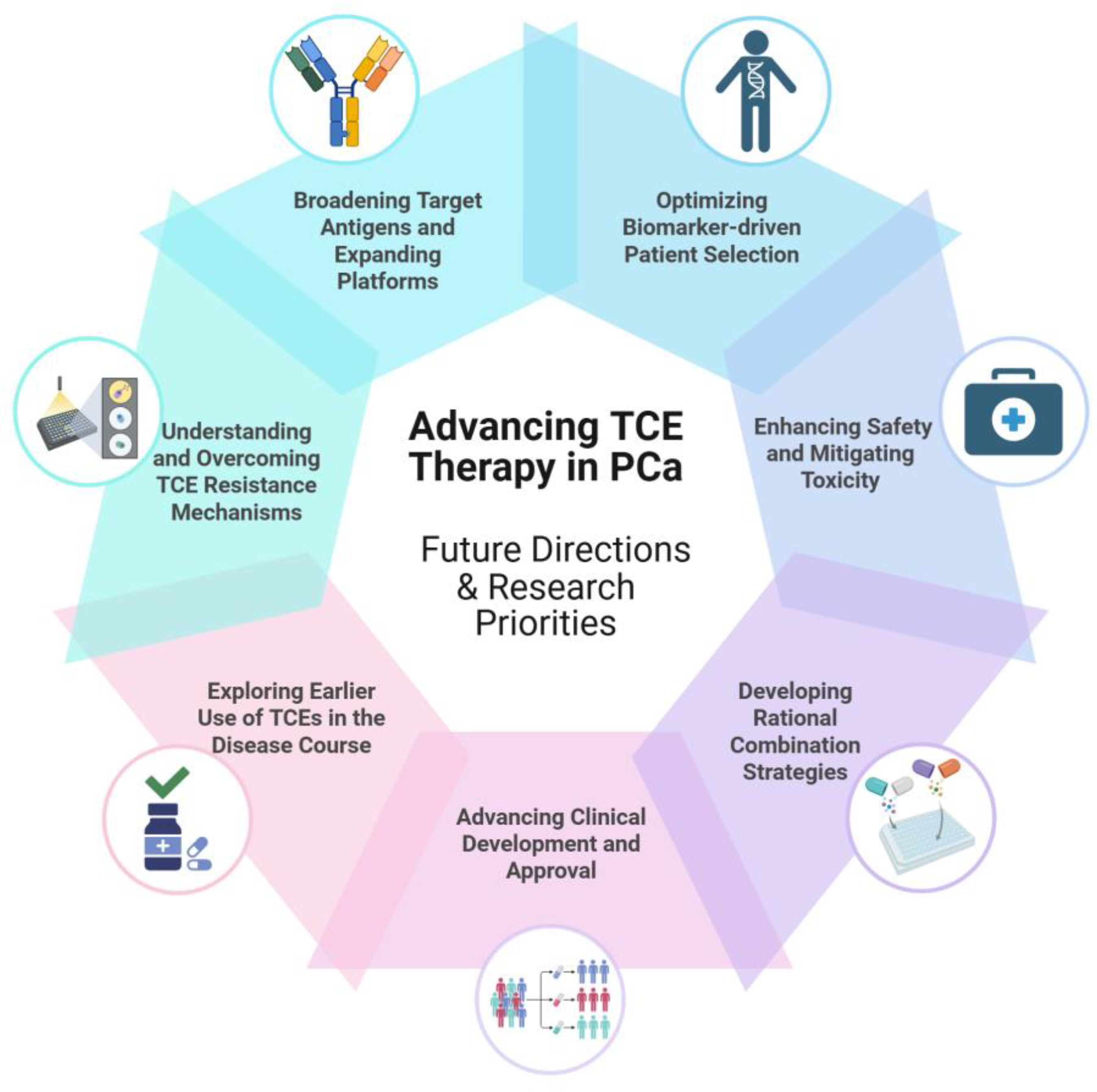

Positioning TCEs within the treatment landscape underscores their significant potential alongside the key hurdles that must be overcome as they advance toward broader clinical use in PCa. An overview of these future directions and research priorities essential for advancing TCE therapy in PCa is presented in

Figure 4. To realize the full promise of this therapeutic class, several key research priorities have emerged, focusing on critical challenges identified thus far, including enhancing durability, improving safety profiles, overcoming resistance, and optimizing patient selection. Below, we outline these important directions for future research aimed at achieving TCE therapy’s full potential.

6.1. Broadening Target Antigens and TCE Platforms

While PSMA and STEAP1 are currently the principal targets, researchers are exploring additional TAAs to reach patients whose tumors have heterogeneous antigen expression. For instance, the prostate stem cell antigen was targeted by a TCE (GEM3PSCA) in early trials (NCT03927573). Human Kallikrein-related peptidase 2 (hK2), an antigen related to PSA, is another target, and Janssen’s JNJ-78278343 (a Kallikrein-related peptidase 2 (KLK2) xCD3 TCE) is in Phase I testing [

66,

67]. Targeting multiple antigens may be crucial for covering the full spectrum of PCa biology and preventing escape. In the future, multi specific engagers may simultaneously target two tumor antigens and CD3, thereby attacking heterogeneous tumor cell populations in one stroke [

45]. Preclinical designs such as dual-affinity retargeting bispecifics and tandem trimeric engagers (TriKEs) are being developed [

68]. Moreover, engaging other immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells (with CD16 (Cluster of Differentiation 16)-directed bispecific killer cell engagers (BiKEs)) is under investigation. These novel platforms can complement TCEs or provide alternatives when T cell function is impaired. The pipeline of next-generation engagers is rich, and ongoing research will identify antigens and formats that yield the best therapeutic index.

6.2. Beyond CD3—NK Engagers and Multi-Specific Constructs

In addition to engaging CD3-positive T cells, some newer bispecifics harness other immune cell subsets or combine multiple functionalities to augment their antitumor activity. One emerging approach involves bridging cancer cells to NK cells by targeting CD16 (FcγRIIIa) and a TAA [

69]. Unlike T cells, NK cells are not restricted by MHC presentation and can be especially advantageous in malignancies with downregulated Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) expression or defects in antigen processing [

69,

70]. Early clinical experience with NK-engaging bispecifics (sometimes referred to as BKEs) has demonstrated manageable safety profiles and encouraging efficacy in hematological cancers, primarily by capitalizing on antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [

71]. Although still in the early stages, NK engagers can be applied to solid tumors, including PCa, particularly those that exhibit a “cold” TME or limited T cell infiltration. Meanwhile, multi-specific constructs expand beyond the two-arm model. Tri-specific designs can incorporate a second TAA or costimulatory/cytokine arm. For instance, some formats couple CD3 and two different TAAs (“OR-gated” targeting) to reduce the risk of antigen-negative escape [

72]. Others add a costimulatory signal (e.g., 4-1BB agonism) or IL-15 moieties to enhance T cell or NK cell expansion and potency in the TME [

72,

73]. Trispecific constructs targeting PSMA, CD3, and an albumin-binding domain have already entered clinical trials for PCa (e.g., HPN424) [

40], illustrating how multi specificity can simultaneously boost half-life and tumor specificity. Over time, these advanced formats may be refined to address the known pitfalls of single-target TCEs such as partial antigen loss and suboptimal durability. Ultimately, by going beyond classical CD3-mediated redirection and incorporating additional targets or immune effector mechanisms, next-generation agents seek to improve both efficacy and safety, offering a broader immunological arsenal against advanced PCa.

6.3. OR-Gated vs. AND-Gated Targeting Strategies

OR-gated and AND-gated targeting strategies offer distinct ways to enhance the selectivity and efficacy of bispecific and multi-specific therapies [

74]. OR-gated designs target two different antigens and kill tumor cells expressing either antigen, thereby reducing the likelihood of immune escape through antigen loss or downregulation. This approach is especially relevant in advanced PCa, where the heterogeneous expression of targets such as PSMA or STEAP1 can hamper single-antigen treatments over time. In contrast, AND-gated approaches require the simultaneous binding of two antigens to the same cell before triggering cytotoxicity. By necessitating the co-expression of both markers, AND gating helps limit on-target off-tumor toxicity, thereby improving safety in tissues with partial or low-level antigen expression [

74,

75]. These “hemi body” or split-antibody concepts are under active investigation as a means to exploit unique tumor–antigen combinations while sparing healthy tissues. In advanced PCa, dual-marker gating might be adapted to include a key TCE domain that only becomes active once both prostate-specific antigens are recognized, thus potentially achieving more precise killing of malignant cells while minimizing risks to the normal prostate or other nontarget tissues. Whether employing OR gating to broaden the coverage of heterogeneous tumors or AND gating to enhance specificity, these strategies exemplify next-generation innovations aimed at overcoming the core challenges faced by single-target TCEs.

6.4. Biomarker-driven Patient Selection

Optimizing patient selection is fundamental to improving TCE outcomes. Expression of the target antigen seems to be the most obvious selection criterion. STEAP1 is expressed in proportionally more patients than PSMA in some analyses of mCRPC (~95% vs. ~68% in one analysis [

76], or 87.7% vs 60.5% [

77]), suggesting that STEAP1 TCEs could treat a wider population. In trials, IHC or PET imaging is used to confirm the presence of the target (for example, PSMA PET scans ensure that a patient’s metastases express PSMA before receiving PSMA TCEs, analogous to selection for PSMA RLT) [

47]. In the future, a combination of biomarkers may be used: antigen density (quantified by imaging uptake or histology) could predict the intensity of the TCE response, while immune contexture markers (such as baseline T cell infiltration or interferon-gamma gene signatures) might predict how readily the TCE-redirected T cells can infiltrate and function in a given tumor [

26]. For DLL3-targeted therapy in NEPC, future trials will likely require a higher DLL3 expression cutoff to enrich for responders [

48]. Another biomarker angle is the monitoring of immune activation markers during therapy (e.g., cytokine levels or circulating T cell profiles) to gauge whether the patient is mounting a response and to preemptively manage side effects. As our understanding grows, we may develop a panel of biomarkers, including tumor genomics, sur-face antigen profiling, and immune phenotypes, to personalize TCE therapy, identify those most likely to benefit, and guide the choice of target antigen for each patient.

6.5. Enhancing Safety and Mitigating Toxicity

Alongside enhancing efficacy through novel platforms and better patient selection (discussed in 6.4), improving the safety profile remains paramount. Safety management remains the top priority in the development of TCEs. CRS, while often manageable, is closely linked to the mechanism of action of TCEs and thus cannot be entirely eliminated. However, structural modifications are being implemented to reduce the severity of CRS without sacrificing efficacy. One strategy is affinity tuning: reducing the affinity of the CD3-binding arm of the TCE can temper the speed and intensity of T cell activation, as attempted with Amgen’s AMG 340 [

78]. Although AMG 340 was discontinued for other reasons, the concept remains scientifically valid and can be applied in future studies. Another approach is to use prodrug TCEs—antibodies that are activated only in the TME (for example, through tumor-specific protease cleavage)—which can localize T cell activation to the tumor and spare systemic immune activation [

79,

80]. Additionally, step-up dosing regimens (gradually increasing the dose with initial low “priming” doses) have already been adopted in trials to safely reach efficacious dose levels [

19,

36,

63]. On the immunogenicity front, fully human or humanized protein scaffolds are now the norm for minimizing ADA formation [

81]. The use of continuous infusion in early trials has largely been supplanted by half-life extended formats, which are not only more convenient but also may reduce immunogenic reactions by avoiding high concentration peaks and certain administration routes (experience from the pasotuxizumab study suggested that subcutaneous delivery led to high ADA rates [

8,

36]). Ongoing research is also investigating adjunct therapies to manage toxicity, such as better prophylaxis or treatment for CRS (beyond tocilizumab and steroids) and monitoring for neurotoxic effects [

17,

49,

82]. By the time TCEs reach Phase III, we anticipate that these safety optimizations will make outpatient administration with manageable side effects a realistic scenario.

6.6. Combination Strategies

Combining TCEs with other therapeutic modalities is a promising strategy to enhance antitumor immunity and potentially overcome the immunosuppressive TME characteristic of advanced PCa. Various combinations aimed at improving TCE efficacy are currently under clinical investigation. For instance, trials are exploring the co-administration of PSMA TCEs with CD28 (Cluster of Differentiation 28) co-stimulatory bispecific antibodies [

83] or PD-1 blocking antibodies [

21], seeking to provide dual signaling for enhanced T cell activation and persistence. Another trial evaluated a 4-1BB agonist TCE (CB307) combined with the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab to augment T cell cytotoxic activity [

84].

Beyond these ongoing trials, several experimental combination approaches hold significant interest. Immune modulators, such as IL-15 super agonists, combined with TCEs could potentially stimulate robust T cell proliferation and function [

85]. Concurrently using ICIs targeting distinct pathways (e.g., anti-PD-1/L1 or anti-Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated protein 4 (CTLA-4)) alongside TCEs may counteract T cell exhaustion and prolong cytotoxic activity within the TME [

86]. Targeting immunosuppressive cytokines like Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β), often elevated in PCa, represents another approach to improve T cell infiltration and enhance TCE efficacy, particularly in resistant lesions [

87].

Integrating TCEs with traditional therapies is also being explored. Chemotherapy or RLT administered prior to TCEs could reduce tumor burden, potentially lessening the severity of CRS and exposing tumor antigens to prime additional immune responses [

88]. Hormonal therapies, central to PCa management, might synergize with TCEs; ADT, for instance, can upregulate PSMA expression, potentially enhancing the binding and efficacy of PSMA-targeted TCEs [

89]. Localized interventions like radiation therapy could induce immunogenic cell death and potentially abscopal effects, creating a TME more favorable for TCE-mediated immunity [

90].

An intriguing strategy involves sequential or concurrent administration of multiple TCEs targeting different antigens [

86]. Given the heterogeneity of antigen expression within tumors and over time, using TCEs against distinct targets (e.g., PSMA and STEAP1) could maximize tumor cell killing and mitigate the risk of antigen-loss escape [

5,

91]. While com-plex regarding safety and dosing, careful management could potentially amplify the “se-rial killing” capacity of engaged T cells. Overall, these diverse combination strategies aim to overcome barriers such as T cell exhaustion and TME immunosuppression, ultimately seeking deeper and more durable therapeutic responses than achievable with TCE monotherapy alone. Continued research into optimally integrated treatment regimens is essential for advancing immunotherapy outcomes in advanced PCa.

6.7. Advancing Clinical Development and Approval

Promising results from early phase trials are now catalyzing larger studies. Notably, a Phase III trial of the STEAP1-targeted TCE AMG 509 is planned to confirm potential survival benefits and impact on quality of life in patients with mCRPC [

92]. Success in such Phase III trials could lead to the first TCE approval for the treatment of PCa. Concurrently, other agents are progressing; for example, Regeneron’s PSMAxCD3 bispecific REGN4336 is in Phase I/II evaluation (alone and with cemiplimab) to assess its safety and preliminary efficacy [

36]. Several new PSMA TCEs (e.g., JNJ-80038114) and the KLK2-directed TCE (JNJ-78278343) are currently in early clinical trials [

93,

94,

95]. These trials will determine the optimal constructs and dosing strategies and expand our understanding of how to integrate TCEs into the treatment sequence. Over the next few years, we expect to see the first randomized trials comparing TCEs versus standard care for PCa, which will be pivotal in positioning these drugs in clinical practice.

6.8. Earlier Use of TCEs in the Disease Course

A significant question is whether TCEs should be moved into earlier lines of therapy rather than being reserved for late stage mCRPC. It is logical to hypothesize that using these agents when the patient’s immune system is less compromised and tumor burden is lower could potentially increase efficacy. A Phase I trial is currently testing a PSMA-targeted TCE in patients with biochemical recurrence (rising PSA after local therapy but no visible metastases) [

37,

96]. This represents a setting with minimal residual disease, where immunotherapy like TCEs could theoretically eliminate micro metastatic cancer. If safe and effective, this strategy could prevent progression to overt metastases. Similarly, future trials may integrate TCEs into the upfront management of metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (e.g., adding a TCE to ADT and AR inhibitors in high-risk patients) to determine whether it can deliver deeper responses. Moving immunotherapy earlier has been beneficial in some other cancers [

97]; whether this holds true for PCa will be answered by these studies. Challenges remain; for instance, using TCEs in asymptomatic patients could alter the risk-benefit calculus, but the potential rewards are high. Researchers will also investigate whether earlier use mitigates resistance mechanisms (e.g., an untreated tumor might express more target antigen and possess a less immunosuppressive milieu than heavily treated tumors).

6.9. Understanding and Overcoming TCE Resistance

Addressing the critical challenge of treatment resistance, observed clinically and anticipated mechanistically, requires understanding escape pathways and developing counter strategies. Finally, a critical research priority is to understand how tumors might resist or escape TCE therapy, and how to counter-act these mechanisms [

98]. As previously mentioned, antigen loss or downregulation is a clear route of resistance [

98]. Detailed molecular studies of post-TCE tumor samples (when available) can reveal whether resistant lesions have lower target expression or mutations affecting the target epitope. This reinforces the need for multi-targeted approaches and sequential antigen targeting. Additionally, the immunosuppressive TME rich in TGF-β, regulatory T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in PCa could blunt TCE efficacy over time [

99]. Therefore, interventions to reprogram the TME are a priority. As discussed, (

Section 6.6), blocking TGF-β signaling is one approach; others include using myeloid cell inhibitors (such as Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF-1R) blockers to reduce suppressive macrophages) or adding IL-12 or other cytokine therapies to boost T helper 1 (Th1) responses in the tumor. Moreover, repeated exposure to TCEs can potentially induce T cell exhaustion. Monitoring T cell phenotypes in patients receiving TCE therapy will inform this; high expression of exhaustion markers (PD-1, Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3) in T cells would support the addition of checkpoint inhibitors or switching strategies at that juncture [

39]. Researchers are also exploring gene expression profiling of tumors during TCE therapy to determine how the tumor reacts; for example, determining whether interferon-stimulated genes are upregulated (indicating an immune attack) or whether escape pathways (such as alternative immune checkpoints) are induced [

100]. Such data can guide rational combinations or sequence adaptations (e.g., if PD-L1 is induced in tumors, a PD-L1 inhibitor may be added. The battle between TCEs and tumor defenses is expected to evolve, and research is geared toward staying one step ahead by anticipating resistance and designing therapeutic countermeasures. In summary, the future of TCEs for PCa will be shaped by ongoing clinical trials and innovative research focusing on improving their efficacy, safety, and patient selection. The field is moving toward more targets, smarter designs, combination regimens, and earlier interventions. These efforts aim to solidify the role of TCEs as durable, safe, and widely applicable treatments for advanced PCa.

7. Conclusion

Having explored the fundamental mechanisms, clinical evolution, safety considerations, comparative value, and future research priorities of T cell engagers in PCa, we return to the central premise: TCEs represent a paradigm shift in the treatment of advanced PCa, offering a means to harness the immune system against a disease that has historically been immunotherapy resistant. Our review traced the arc from initial proof-of-concept and early challenges to the increasingly sophisticated agents demonstrating tangible clinical activity today. By bridging T cells to tumor cells, TCEs can induce tumor regression and PSA decline, even in mCRPC patients who have exhausted conventional therapies. Clinical data, although primarily from early phases, have demonstrated that prostate tumors, including aggressive variants, can be effectively targeted via T cell redirection—a remarkable development where ICIs and vaccines alone have largely fallen short.

The strength of TCEs lies in their novel mechanisms and engineering versatility. However, the journey thus far underscores that these are potent agents requiring careful management of challenges like CRS and antigen escape through continued refinement of drug de-sign and clinical protocols. Balanced optimism permeates the field: the potential to trans-form treatment is clear, but requires validation and further improvements in efficacy, durability, and safety. Ongoing efforts focusing on rational combinations, biomarker-driven patient selection, and moving TCEs earlier in the disease course are crucial. While this re-view provides a comprehensive synthesis based on current evidence, as a narrative review, it reflects the authors’ perspective and selection of literature; further systematic analyses may provide complementary insights.

In conclusion, T cell engagers are poised to play a significant role in the evolving landscape of PCa therapy. They fill a critical immunotherapeutic gap for this pre-dominantly ‘cold’ tumor, offering a flexible, off-the-shelf approach. As research continues to sharpen patient selection, fine-tune molecular designs, and integrate supportive com-bination therapies, TCEs hold the potential to yield more durable remissions and improve long-term control of advanced PCa. The coming years, marked by pivotal clinical trials, will be decisive. If successful, T cell engagers will not merely add another tool, but mark a new chapter, offering substantial hope for improved outcomes in a disease that remains a leading cause of cancer mortality in men. The convergence of immunology and oncology embodied by TCEs holds tremendous promise, and sustained, strategic innovation will determine how effectively we translate that promise into meaningful reality for patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-A.K. and J.Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-A.K.; writing—review and editing, W.-A.K. and J.Y.J.; supervision, J.Y.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center (No 2211880-3, and No 1941760-1). .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADA |

Anti-Drug Antibody |

| ADCC |

Antibody-Dependent Cell-mediated Cytotoxicity |

| ADC |

Antibody-Drug Conjugate |

| ADT |

Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| AE |

Adverse Event |

| AMG |

Amgen (company code for drug development) |

| APC |

Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| AR |

Androgen Receptor |

| ASCO |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| BiKE |

Bispecific Killer cell Engager |

| BiTE® |

Bispecific T cell Engager |

| CAR |

Chimeric Antigen Receptor |

| CAR-T cell |

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell |

| CD |

Cluster of Differentiation |

| CDC |

Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity |

| CDK12mut |

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 12 mutated/mutation |

| CRS |

Cytokine Release Syndrome |

| CSF-1R |

Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor |

| CTLA-4 |

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated protein 4 |

| DLL3 |

Delta-Like Ligand3 |

| dMMR |

deficient Mismatch Repair |

| Fc |

Fragment crystallizable region |

| FcRn |

Neonatal Fc Receptor |

| G |

Grade (for toxicity grading) |

| hK2 |

Human Kallikrein-related peptidase 2 |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HLE |

Half-Life Extended |

| HPN |

Harpoon Therapeutics (company code for drug development) |

| ICANS |

Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome |

| ICI |

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| IV |

Intravenous |

| KLK2 |

Kallikrein-related peptidase 2 |

| LAG-3 |

Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3 |

| MHC |

Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| mCRPC |

Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| MOA |

Mechanism of Action |

| MSI-H |

Microsatellite Instability-High |

| NEPC |

Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer |

| NK |

Natural Killer |

| ORR |

Objective Response Rate |

| OS |

Overall Survival |

| PCa |

Prostate Cancer |

| PD-1 |

Programmed cell Death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PET |

Positron Emission Tomography |

| PSA |

Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PSA50 |

≥50% decline in Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PSMA |

Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen |

| PTEN |

Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| Q2weeks |

Every 2 weeks |

| RB1 |

RB Transcriptional Corepressor 1 |

| RECIST |

Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors |

| REGN |

Regeneron (company code for drug development; REGN4336) |

| RLT |

Radioligand Therapy |

| SCLC |

Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| scFv |

Single-chain variable fragment |

| SD |

Stable Disease |

| STEAP1 |

Six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1 |

| TAA |

Tumor-Associated Antigen |

| TCE |

T cell engager |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| Th1 |

T helper 1 |

| TIM-3 |

T cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain containing-3 |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNFα |

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TP53 |

Tumor Protein P53 |

| TriKE |

Tandem trimeric engager |

| TriTE |

Trispecific T cell Engager |

References

- Francini, E.; Agarwal, N.; Castro, E.; Cheng, H.H.; Chi, K.N.; Clarke, N.; Mateo, J.; Rathkopf, D.; Saad, F.; Tombal, B. Intensification approaches and treatment sequencing in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review. European Urology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.-A.; Joung, J.Y. Immunotherapy in Prostate Cancer: From a “Cold” Tumor to a “Hot” Prospect. Cancers 2025, 17, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, J.N.; Hoimes, C.J.; Gerritsen, W.R.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Elliott, T.; Hwang, C.; Tije, A.J.T.; Omlin, A.; McDermott, R.S.; Fradet, Y. Pembrolizumab plus enzalutamide for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing on enzalutamide: cohorts 4 and 5 of the phase 2 KEYNOTE-199 study. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantoff, P.W.; Higano, C.S.; Shore, N.D.; Berger, E.R.; Small, E.J.; Penson, D.F.; Redfern, C.H.; Ferrari, A.C.; Dreicer, R.; Sims, R.B.; Xu, Y.; Frohlich, M.W.; Schellhammer, P.F. Sipuleucel-T Immunotherapy for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucà, G.; Spagnoletti, A.; Ambrosini, M.; De Braud, F.; Di Nicola, M. Immune cell engagers in solid tumors: promises and challenges of the next generation immunotherapy. ESMO open 2021, 6, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, C.H.; Ozay, Z.I.; Ostrowski, M.; Mercinelli, C.; Gebrael, G.; Sayegh, N.; Swami, U.; Azad, A.A.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Agarwal, N. T-Cell engagers in prostate cancer. European Urology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatchinamoorthy, K.; Colbert, J.D.; Rock, K.L. Cancer immune evasion through loss of MHC class I antigen presentation. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 636568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, H.L.; Hainline, K.; Theoharis, N.; Wu, B.; Brandl, C.; Webhofer, C.; McComb, M.; Wittemer-Rump, S.; Koca, G.; Stienen, S. Characterization and root cause analysis of immunogenicity to pasotuxizumab (AMG 212), a prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeting bispecific T-cell engager therapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1261070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Evans, L.; Bizzaro, C.L.; Quaglia, F.; Verrillo, C.E.; Li, L.; Stieglmaier, J.; Schiewer, M.J.; Languino, L.R.; Kelly, W.K. STEAP1–4 (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1–4) and their clinical implications for prostate cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Champiat, S.; Lai, W.V.; Izumi, H.; Govindan, R.; Boyer, M.; Hummel, H.-D.; Borghaei, H.; Johnson, M.L.; Steeghs, N. ; Tarlatamab; a first-in-class DLL3-targeted bispecific T-cell engager; in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase I study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 2893–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, J.; Kudlacek, S.; Qi, T.; Dunlap, T.; Cao, Y. Population dynamics of immunological synapse formation induced by bispecific T cell engagers predict clinical pharmacodynamics and treatment resistance. Elife 2023, 12, e83659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorff, T.; Horvath, L.G.; Autio, K.; Bernard-Tessier, A.; Rettig, M.B.; Machiels, J.-P.; Bilen, M.A.; Lolkema, M.P.; Adra, N.; Rottey, S. A phase I study of acapatamab, a half-life extended, PSMA-targeting bispecific T-cell engager for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2024, 30, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, M.; Ren, F.; Meng, X.; Yu, J. The landscape of bispecific T cell engager in cancer treatment. Biomarker Research 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Piulats, J.M.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Goh, J.; Ojamaa, K.; Hoimes, C.J.; Vaishampayan, U.; Berger, R.; Sezer, A.; Alanko, T.; de Wit, R.; Li, C.; Omlin, A.; Procopio, G.; Fukasawa, S.; Tabata, K.I.; Park, S.H.; Feyerabend, S.; Drake, C.G.; Wu, H.; Qiu, P.; Kim, J.; Poehlein, C.; de Bono, J.S. Pembrolizumab for Treatment-Refractory Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Multicohort, Open-Label Phase II KEYNOTE-199 Study. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V.; Kamat, N.V.; Pariva, T.E.; Wu, L.-T.; Tsao, A.; Sasaki, K.; Sun, H.; Javier, G.; Nutt, S.; Coleman, I. Targeting advanced prostate cancer with STEAP1 chimeric antigen receptor T cell and tumor-localized IL-12 immunotherapy. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.R.; Rottey, S.; Bernard-Tessier, A.; Mellado-Gonzalez, B.; Kosaka, T.; Stadler, W.M.; Sandhu, S.; Yu, B.; Shaw, C.; Ju, C.-H. Phase 1b study of tarlatamab in de novo or treatment-emergent neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC). American Society of Clinical Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géraud, A.; Hueso, T.; Laparra, A.; Bige, N.; Ouali, K.; Cauquil, C.; Stoclin, A.; Danlos, F.-X.; Hollebecque, A.; Ribrag, V. Reactions and adverse events induced by T-cell engagers as anti-cancer immunotherapies, a comprehensive review. European Journal of Cancer 2024, 114075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Dovedi, S.J.; Vajjah, P.; Phipps, A. Strategies for clinical dose optimization of T cell-engaging therapies in oncology, MAbs, Taylor & Francis, 2023, pp. 218 1016.

- Kelly, W.K.; Danila, D.C.; Lin, C.-C.; Lee, J.-L.; Matsubara, N.; Ward, P.J.; Armstrong, A.J.; Pook, D.; Kim, M.; Dorff, T.B.; Fischer, S.; Lin, Y.-C.; Horvath, L.G.; Sumey, C.; Yang, Z.; Jurida, G.; Smith, K.M.; Connarn, J.N.; Penny, H.L.; Stieglmaier, J.; Appleman, L.J. ; Xaluritamig, a STEAP1 × CD3 XmAb 2+1 Immune Therapy for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Results from Dose Exploration in a First-in-Human Study. Cancer Discovery 2024, 14, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surowka, M.; Schaefer, W.; Klein, C. Ten years in the making: application of CrossMab technology for the development of therapeutic bispecific antibodies and antibody fusion proteins, MAbs, Taylor & Francis, 2021, pp. 196 7714.

- De Bono, J.S.; Fong, L.; Beer, T.M.; Gao, X.; Geynisman, D.M.; Burris, H.A., III; Strauss, J.F.; Courtney, K.D.; Quinn, D.I.; VanderWeele, D.J. Results of an ongoing phase 1/2a dose escalation study of HPN424, a tri-specific half-life extended PSMA-targeting T-cell engager, in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Wolters Kluwer Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, L.; Olson, K.; Kelly, M.P.; Crawford, A.; DiLillo, D.J.; Tavaré, R.; Ullman, E.; Mao, S.; Canova, L.; Sineshchekova, O.; Finney, J.; Pawashe, A.; Patel, S.; McKay, R.; Rizvi, S.; Damko, E.; Chiu, D.; Vazzana, K.; Ram, P.; Mohrs, K.; D’Orvilliers, A.; Xiao, J.; Makonnen, S.; Hickey, C.; Arnold, C.; Giurleo, J.; Chen, Y.P.; Thwaites, C.; Dudgeon, D.; Bray, K.; Rafique, A.; Huang, T.; Delfino, F.; Hermann, A.; Kirshner, J.R.; Retter, M.W.; Babb, R.; MacDonald, D.; Chen, G.; Olson, W.C.; Thurston, G.; Davis, S.; Lin, J.C.; Smith, E. Generation of T-cell-redirecting bispecific antibodies with differentiated profiles of cytokine release and biodistribution by CD3 affinity tuning. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 14397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yang, Y.; Mortazavi, A.; Zhang, J. Emerging immunotherapy approaches for treating prostate cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 14347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, S.; Gunde, T.; Snell, D.; Brock, M.; Weinert, C.; Simonin, A.; Hess, C.; Tietz, J.; Johansson, M.; Spiga, F.M. Engineering of a trispecific tumor-targeted immunotherapy incorporating 4-1BB co-stimulation and PD-L1 blockade. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 2004661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Ptacek, J.; Havlinova, B.; Nedvedova, J.; Barinka, C.; Novakova, Z. Targeting prostate Cancer using bispecific T-Cell engagers against prostate-specific membrane Antigen. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2023, 6, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Simão, D.C.; Zarrabi, K.K.; Mendes, J.L.; Luz, R.; Garcia, J.A.; Kelly, W.K.; Barata, P.C. Bispecific T-cell engagers therapies in solid tumors: focusing on prostate cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, J.C.; Berking, C.; Forschner, A.; Gebhardt, C.; Heinzerling, L.; Meier, F.; Ochsenreither, S.; Siveke, J.; Hauschild, A.; Schadendorf, D. Practical guidelines for the management of adverse events of the T cell engager bispecific tebentafusp. European Journal of Cancer 2023, 191, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Zugmaier, G.; Rizzari, C.; Morris, J.D.; Gruhn, B.; Klingebiel, T.; Parasole, R.; Linderkamp, C.; Flotho, C.; Petit, A. Effect of blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on event-free survival among children with high-risk first-relapse B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2021, 325, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, M.J.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Morschhauser, F.; Bachy, E.; Corradini, P.; Iacoboni, G.; Khan, C.; Wróbel, T.; Offner, F.; Trněný, M. Glofitamab for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.; Garfall, A.L.; van de Donk, N.W.; Nahi, H.; San-Miguel, J.F.; Oriol, A.; Nooka, A.K.; Martin, T.; Rosinol, L.; Chari, A. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Fakhri, B.; Shah, N. Toci or not toci: innovations in the diagnosis, prevention, and early management of cytokine release syndrome. Leukemia & Lymphoma 2021, 62, 2600–2611. [Google Scholar]

- Belmontes, B.; Sawant, D.V.; Zhong, W.; Tan, H.; Kaul, A.; Aeffner, F.; O’Brien, S.A.; Chun, M.; Noubade, R.; Eng, J. Immunotherapy combinations overcome resistance to bispecific T cell engager treatment in T cell–cold solid tumors. Science translational medicine 2021, 13, eabd1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbari, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Pilvankar, M.; Nickaeen, M.; Hansel, S.; Popel, A.S. Using quantitative systems pharmacology modeling to optimize combination therapy of anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor and T cell engager. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1163432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, D.; Lin, M. Advances in PSMA-targeted therapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 2022, 25, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Campbell, B.K.; Stylli, S.S.; Corcoran, N.M.; Hovens, C.M. The prostate cancer immune microenvironment, biomarkers and therapeutic intervention. Uro 2022, 2, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, W.K.; Thanigaimani, P.; Sun, F.; Seebach, F.A.; Lowy, I.; Sandigursky, S.; Miller, E. A phase 1/2 study of REGN4336, a PSMAxCD3 bispecific antibody, alone and in combination with cemiplimab in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, J.S.; Hackenbruch, C.; Walz, J.S.; Jung, S.; Pflügler, M.; Schlenk, R.F.; Ochsenreither, S.; Hadaschik, B.A.; Darr, C.; Jung, G.; Salih, H.R. Updated results on the bispecific PSMAxCD3 antibody CC-1 for treatment of prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, 2536–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, N.; Robbrecht, D.; Voortman, J.; Parren, P.W.; Macia, S.; Veeneman, J.; Umarale, S.; Winograd, B.; van der Vliet, H.J.; Wise, D.R. Early dose escalation of LAVA-1207, a novel bispecific gamma-delta T-cell engager (Gammabody), in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). American Society of Clinical Oncology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ren, X.; An, R.; Song, H.; Tian, Y.; Wei, X.; Shi, M.; Wang, Z. The Role of STEAP1 in Prostate Cancer: Implications for Diagnosis and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorff, T.; Horvath, L.G.; Autio, K.; Bernard-Tessier, A.; Rettig, M.B.; Machiels, J.P.; Bilen, M.A.; Lolkema, M.P.; Adra, N.; Rottey, S.; Greil, R.; Matsubara, N.; Tan, D.S.W.; Wong, A.; Uemura, H.; Lemech, C.; Meran, J.; Yu, Y.; Minocha, M.; McComb, M.; Penny, H.L.; Gupta, V.; Hu, X.; Jurida, G.; Kouros-Mehr, H.; Janát-Amsbury, M.M.; Eggert, T.; Tran, B. A Phase I Study of Acapatamab, a Half-life Extended, PSMA-Targeting Bispecific T-cell Engager for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2024, 30, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Galisteo, A.; Compte, M.; Álvarez-Vallina, L.; Sanz, L. When three is not a crowd: trispecific antibodies for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raychaudhuri, R.; Schweizer, M.T.; Hawley, J.E.; Fong, L.; Yu, E.Y. Xaluritamig: a first step towards a new target, new mechanism for metastatic prostate cancer. AME Clinical Trials Review 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ding, C.-K.C.; Aggarwal, R.R. Emerging Therapeutic Targets of Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Current Oncology Reports 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, A.; Patel, N.; Patel, P.A.; Kilinc, E.; Hachem, S.; Elajami, M.; Mansour, E. Immunotherapeutic strategies and immunotherapy resistance in prostate cancer, Therapy Resistance in Prostate Cancer, Elsevier2024, pp. 235–253.

- Goebeler, M.-E.; Stuhler, G.; Bargou, R. Bispecific and multispecific antibodies in oncology: opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2024, 21, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, N.; Kazerani, M.; Nicholls, A.; Vick, B.; Wulf, J.; Straub, T.; Scheurer, M.; Muth, A.; Hänel, G.; Nixdorf, D. T-cell exhaustion induced by continuous bispecific molecule exposure is ameliorated by treatment-free intervals, Blood. The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2022, 140, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Deluce, J.E.; Cardenas, L.; Lalani, A.-K.; Vareki, S.M.; Fernandes, R. Emerging biomarker-guided therapies in prostate cancer. Current oncology 2022, 29, 5054–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, H.; Dowlati, A.; Jain, P.; Johnson, M.L.; Sanborn, R.E.; Thompson, J.R.; Mamdani, H.; Schenk, E.L.; Aggarwal, R.R.; Sankar, K. Interim results from a phase 1/2 study of HPN328, a tri-specific, half-life (T1/2) extended DLL3-targeting T-cell engager, in patients (pts) with neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) and other neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN). American Society of Clinical Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, K.K.; Bender, B.C.; Li, Z.; Turner, D.C.; Roy, S.; Belousov, A.; Li, C.-C. Clinical Pharmacology of Cytokine Release Syndrome with T-Cell–Engaging Bispecific Antibodies: Current Insights and Drug Development Strategies. Clinical Cancer Research 2025, 31, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.C.; Neelapu, S.S.; Giavridis, T.; Sadelain, M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2022, 22, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]