1. Introduction

Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, the pace of AI breakthroughs has accelerated exponentially—from years to months and now weeks. In this context, ensuring AI is “beneficial to all” has become a race against time. The proliferation of new terminologies associated with AI for Good, such as “Responsible AI” [

1], “Trustworthy AI” [

2], and “AI for Social Good” [

3], reflects growing interest but also underscores the complexities involved. The notion of “Good” in AI carries multilayered implications. Technically, it entails systems that are fair, transparent, and accountable. Societally, it involves leveraging AI to address humanity’s grand challenges, such as poverty eradication and climate adaptation. Paradigmatically, it requires scrutinising the political economy of AI, including its roles in power concentration, digital divide, and ecological degradation. Beyond being multilayered, the concept of “Good” is inherently tied to cultural and contextual definitions of a “good society.” Birhane [

4] highlights the importance of cultural relativity, noting that what is deemed critical or acceptable in one context may be irrelevant or even undesirable in another. For instance, China views social credit scoring as a benign form of societal governance prioritising social order, while the EU, upholding individual liberties, prohibits such systems. This disparity illustrates how the meaning of “Good” is not only layered but also contextually bound, shaped by societal values and norms.

Scholars e.g., [

5,

6,

7] have called for broadening the scope of AI ethics beyond the Global North’s institutional and cultural contexts to include perspectives from the Global South. This shift has sparked critical inquiries into “AI for and from the Global South” [

8]. However, like the concept of “Good,” the notion of the “South” is far from static. Traditionally referring to postcolonial, developing nations, the “South” has been reconceptualised by Santos [

9] as a collective symbol of “human suffering caused by capitalism and colonialism, as well as resistance to overcoming such suffering.” This expanded view includes marginalised groups in the Global North and highlights disparities even within the South, such as between billionaires and impoverished communities [

10]. Png [

8] encapsulates this complexity with the idea of “economic Souths in the geographic North and Norths in the geographic South,” presenting the South as a dynamic representation of structural inequities and collective struggles for justice.

Thailand’s agricultural sector provides a compelling lens through which to explore these dynamics. While agriculture’s share of GDP has declined from 36.4% in 1960 to 8.6% in 2020 [

11], it remains vital, employing one-third of the Thai labour force [

12] and acting as a safety net for rural households. However, the sector faces significant challenges, including an ageing workforce, low productivity, and pervasive poverty among farming households. Thai farmers, often occupying the lowest socioeconomic strata, epitomise the marginalised groups described by Santos [

9]. Their struggles reflect the broader realities of the economic Souths within the geographic South, necessitating a contextual examination of how AI interacts with these marginalised groups—whether as users or beneficiaries—and its broader socio-economic impacts.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

In my PhD dissertation, which forms the foundation of this article, I propose a framework examining three intersections where the connotations of “South” and “Good” converge:

Traditional Intersection: The Global South is equated with developing nations, and “Good” in AI is tied to economic development and national competitiveness.

Hybrid Intersection: The South transcends geography to include marginalised populations within the capitalist system [

9]. “Good” in AI focuses on addressing societal challenges, often aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Transformative Intersection: The South represents resistance to the status quo, with “Good” in AI reflecting emancipation from oppressive structures, including those underpinning AI development itself.

These three intersections have no clear starting and end points but dynamically emerge and coexist simultaneously, albeit with varying degrees of prominence. Importantly, a shift in emphasis from a traditional to a transformative perspective cannot be assumed to occur organically or without contention. Each intersection reflects distinct value systems, priorities, and political economies, often resulting in tensions over what constitutes the “Good” in AI and how it should be pursued.

1.2. The Significance of Hybrid Intersection

The concept of the hybrid intersection is vital for contemporary AI governance because it captures the ongoing transition in AI discourses and practices—from a deterministic, technology-driven perspective towards a more socio-technically nuanced and human-centred framework. At this intersection, AI is neither perceived merely as an uncontrollable, complex technology nor as a neutral tool devoid of socio-political implications [

13]. Rather, it is acknowledged explicitly as a socio-technical system—a product intentionally shaped by human design, embedded with specific cultural, institutional, and ethical values [

14,

15]. Recognising AI’s inherent human intentionality shifts the discourse away from passive acceptance of technological determinism [

15,

16] towards a proactive human-centred approach, emphasising that AI can and should be explicitly directed for societal benefit [

17,

18].

The term “hybrid” is inspired from the Three Horizons Framework [

19] and Schiff’s [

20] classification of STI (science, technology, and innovation) policies. The Three Horizons Framework has an intermediary phase (H2) where there is contestability and ambiguity in policy/goal transition, making a shift in perspective genuine yet provisional. Conversely, Shiff’s classification underscores the “hybrid” model – where transformative objectives are negotiated within traditional policy and incentive structures. Therefore, the hybrid intersection is an intermediary phase that incorporates “growth with governance and mission.” Thus, the concept of “Good” revolves around creating opportunities for the Southern population to benefit from technological advancements. While this approach addresses immediate needs and integrates these groups into the broader socio-economic fabric, it often lacks the emancipatory impact to challenge the structural features and value systems that sustain the South’s deprivation condition.

To demonstrate and contextualise this remark, this article examines how the framing of “social good” and the context driving Agricultural AI applications in Thailand may fall short of achieving true prosperity for Thai farmers due to the prevailing focus on immediate financial gains at the expense of a broader agenda encompassing environmental sustainability and systemic reform. This narrow framing not only limits the transformative potential of AI but also entrenches the existing political economy, leaving deeper structural issues unresolved [

21].

This research critically addresses an essential gap in current scholarship concerning how the concept of “AI for social good” is framed and enacted within Southern context. While AI-based agricultural innovations are frequently positioned as unproblematic contributors to sustainable development and farmer empowerment, such claims often remain narrowly economic in scope, neglecting broader social, ethical, and ecological dimensions. This study is significant precisely because it interrogates how Agricultural AI in Thailand is frequently trapped within a “hybrid intersection”—a contested middle-ground characterised by incremental improvements and immediate economic relief but limited in achieving deeper structural transformation in power shifting.

1.3. Research Outline

The remainder of the article proceeds in eleven parts that move from conceptual framing to empirical analysis and, finally, to synthesis and policy implications.

Section 2,

Section 3 and

Section 4 form the literature review and contextual foundations:

Section 2 introduces Agricultural AI, outlining its promises and attendant risks;

Section 3 examines the classifications of “Good” associated with AI and their interconnections;

Section 4 situates the lived precarities of Thai smallholders.

Section 5 details the research design, including case-selection, data sources, and analytical procedure. Empirical findings unfold in two stages.

Section 6 maps the contemporary Agricultural-AI value chain in Thailand, and

Section 7 interrogates the cost structures and business models that mediate farmers’ access to these technologies. The insights from these sections form the foundation for

Section 8 and

Section 9, which evaluate the good governance practices and social good impacts of Agricultural AI, respectively.

Section 10 synthesises the evidence to expose two persistent tensions—data commodification versus social-good delivery, and market optimisation versus structural reform—thereby illustrating the constraints often found in the hybrid intersection.

Section 11 concludes by distilling policy recommendations, practical implications, and avenues for future research.

2. AI in Agriculture

In recent years, authoritative frameworks such as the OECD [

22] and the EU’s AI Act have sought to provide more precise definitions of AI. According to these definitions, AI refers to machine-based systems that process inputs to infer outputs such as predictions, recommendations, content generation, or decisions. These outputs, in turn, influence physical or virtual environments, with AI systems demonstrating various degrees of autonomy and adaptiveness throughout their deployment lifecycle. This dynamic capability allows AI to continuously evolve and optimise its performance in response to new data and conditions, making it an invaluable tool for addressing complex challenges in modern society. A compelling example of this transformative potential can be found in agriculture, where AI is driving the transition to the Agricultural 4.0 paradigm. This paradigm shift is characterised by the integration of advanced science, digital technologies, and data-driven approaches into agricultural practices.

2.1. Drivers of Agricultural AI

The use of AI in agriculture embodies the transition onto the Agricultural 4.0 paradigm, which integrates advanced science, digital technologies, and data-driven approaches into agricultural practices. Reflecting the ethos of the “green revolution,” the transformation of agriculture is driven by the urgent need to scale up the global food supply to meet the demands of a rapidly growing population while simultaneously reducing inputs, minimising environmental impacts, and addressing critical issues such as climate change and food waste. We stand at a pivotal juncture where escalating demands and environmental constraints necessitate a fundamental shift in agricultural practices. By 2050, global food production will need to increase by 50% to feed a projected population of 10 billion[

23]. Yet, this challenge is compounded by the declining fertility of agricultural lands, with approximately 34% of global agricultural land now degraded due to unsustainable farming methods[

24]. Furthermore, agricultural activities have doubled greenhouse gas emissions over the past half-century, intensifying droughts, floods, and other climatic disruptions. These changes have profound implications for agricultural yields, food quality, and accessibility, particularly for marginalised households. As such, the agricultural sector must play a central role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and devising strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change.

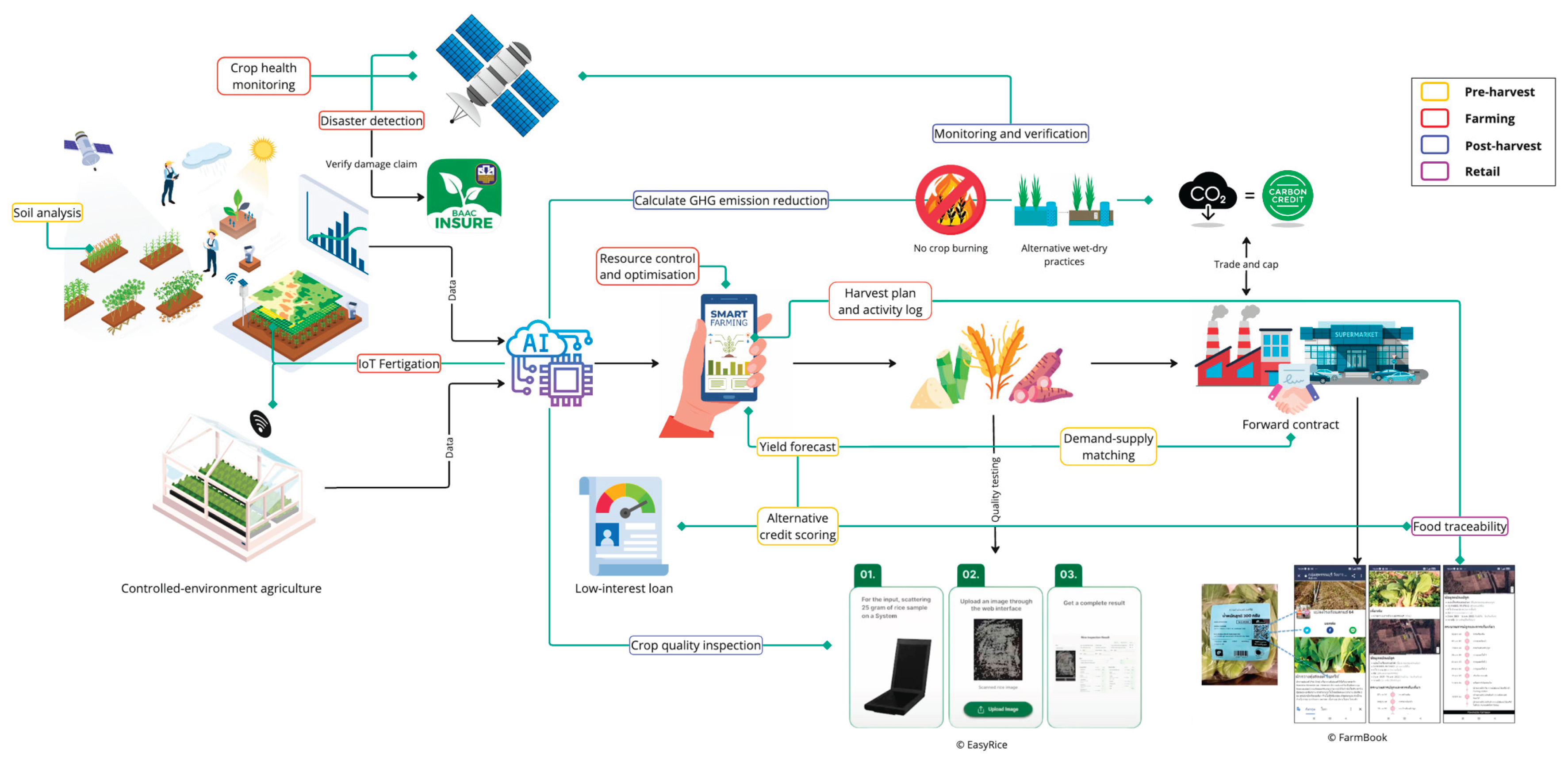

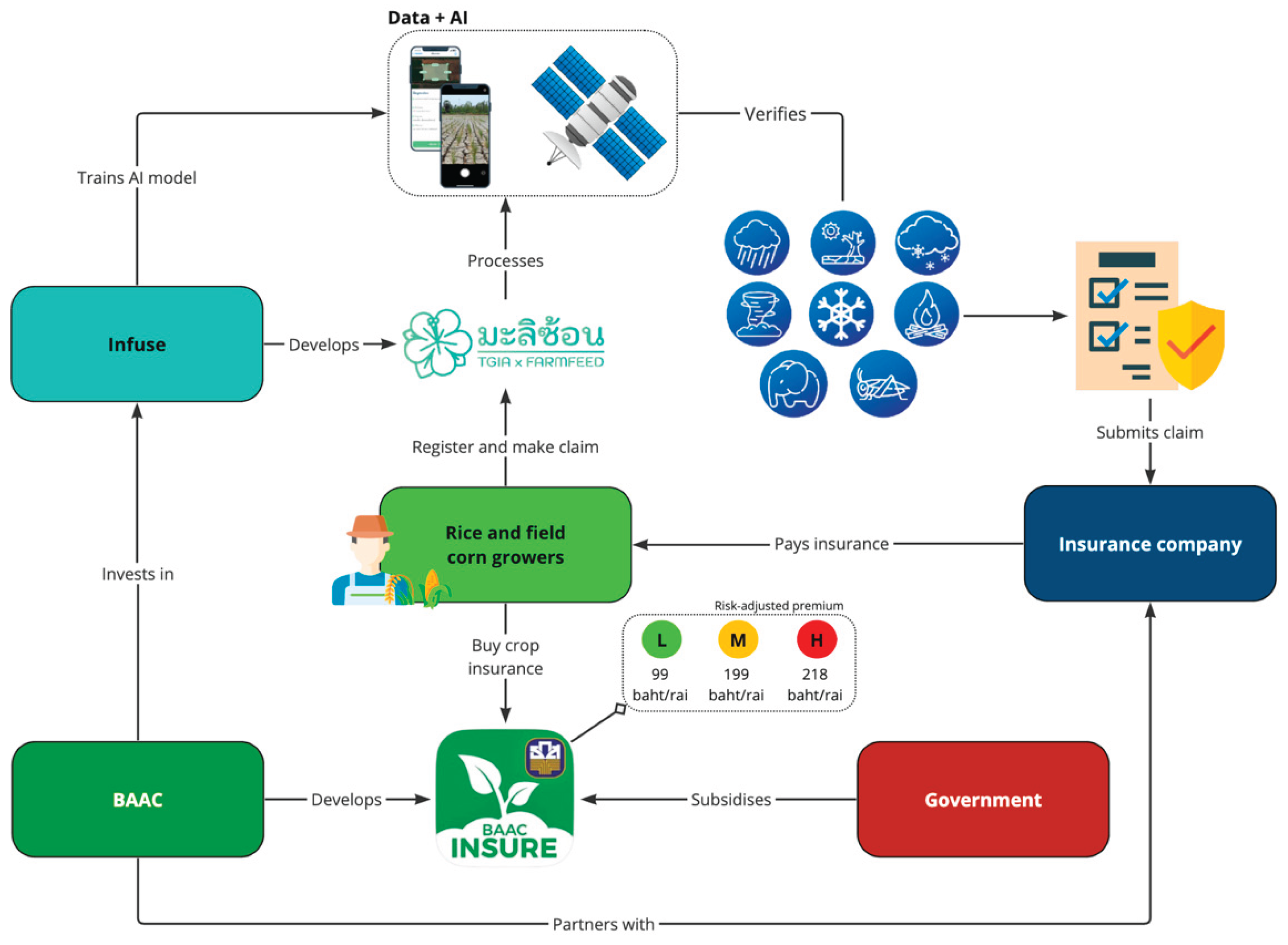

In response to these challenges, Agricultural AI is increasingly framed as a form of AI for “social good,” positioned as a transformative tool to address these global issues. Among its most recognisable applications is precision agriculture (PA), or smart farming, which entails precisely monitoring, measuring, and controlling farming inputs—such as water, fertiliser, and pesticides—to meet the specific needs of crops, animals, or soil conditions. By leveraging real-time data and automation, PA enhances resource efficiency, boosts productivity, and reduces environmental impact. However, the potential of Agricultural AI extends far beyond smart farming. It is increasingly employed in diverse areas, including crop quality inspection, determining credit scores based on past yields, and monitoring carbon sequestration and emission reductions. These applications demonstrate the expansive role of AI in reshaping the agricultural landscape. To capture the breadth of these innovations, the term “Agricultural AI” will be used as a collective reference for all AI technologies deployed within the agricultural sector.

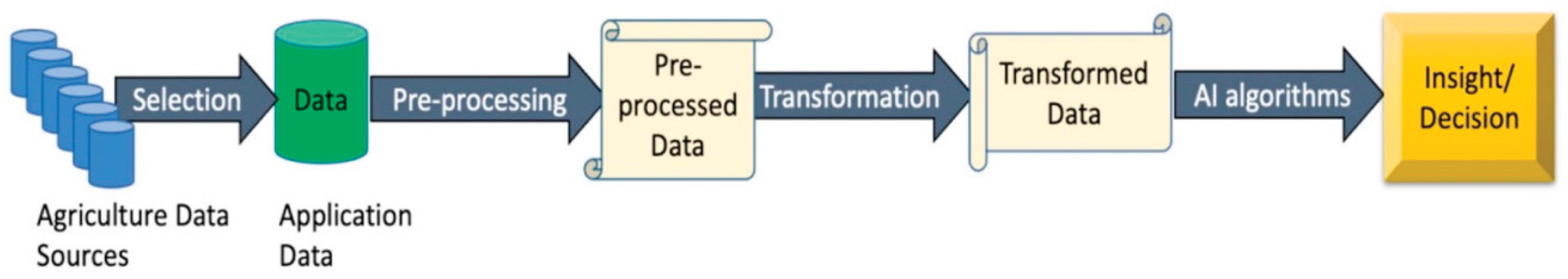

Hackfort [

25] notes that Agricultural AI encompasses both digitisation—the technical process of converting analogue information into digital data—and digitalisation, the broader societal process of integrating and embedding digital technologies into everyday practices, workflows, and systems to transform how society operates [

26]. The digitisation of agriculture begins with collecting extensive data on various aspects of farming, including production metrics, environmental conditions, and machinery operations. This data is gathered from diverse sources such as wireless sensor networks, internet-connected weather stations, surveillance cameras, drones, and historical records. Once collected, the data is used to develop advanced analytics tools that facilitate more informed decision-making and enable automated actions (

Figure 1). The digitalisation of agriculture, however, extends beyond the technical process, requiring social configurations that ensure the acceptance and integration of these technologies within agricultural communities. As Bronson [

27] observed, the appeal of precision agriculture lies in its promise to address farmers’ dual concerns about crop productivity and environmental stewardship. This concept, called “sustainable productivism,” presents PA as a ‘win-win’ solution, allowing farmers to fulfil their roles as environmental stewards while maintaining or enhancing profitability.

2.2. Concerns over Agricultural AI

However, critical scholars view Agricultural 4.0 technologies as a “technofix” for addressing food insecurity, environmental degradation, and climate change [

29]. Weinberg [

30] defines technofixes as solutions that reconfigure, obscure, postpone, or even exacerbate underlying problems and trade-offs. Factors such as farm resources, productivity, and income, which are easily quantifiable, are readily incorporated into technical solutions. In contrast, concepts like justice, solidarity, and human dignity—difficult to measure and deeply entrenched in political contestation—often evade the scope of these technofixes [

6]. Retrospectively, these solutions depoliticise critical global challenges such as hunger, climate change, and poverty, detracting from the structural reforms necessary to address these issues at their core [

31].

Stock and Gardezi [

32] argue that Agricultural AI represents the latest manifestation of a capital-intensive approach to ecological modernisation in farming. For example, through precision agriculture, agricultural technology providers (ATPs) establish new digital frontiers in rural areas, facilitating the expansion of capital into spaces previously untouched by digitalisation. In this context, PA serves as a new agrarian frontier for surveillance capitalism. Duncan et al. [

33] suggest that the financial and technology sectors reap the greatest benefits from this shift. Financial institutions leverage data-collecting precision tools to expedite the financialisation of agriculture, while the tech industry uses the complexity of lands, crops, and farmers as a testbed for developing and refining AI capabilities in real-world settings. This creates a power dynamic marked by significant imbalances between farmers and ATPs [

34]. ATPs consolidate proprietary data and intellectual property rights, not only through seed and chemical patents but also via digital platforms. This control allows them to amass capital by exercising dominion over the data generated by farmers. As a result, agricultural AI, specifically PA systems, facilitate a social order where farmers become increasingly reliant on the information and commercial products provided by ATPs, reshaping the dynamics of the agricultural sector [

35].

3. Notions of Good

The notion of good is nebulous; even academia across disciplines ascribes different concepts and descriptions to it. Green [

36] posits that in computer science, “good” denotes incremental improvement in the performance and efficiency of the system. In the field of social justice, “good” represents a structural change in the system that liberates individuals from oppression and necessitates human flourishing. Following Green’s comment, I distinguish the notion of “good” technology into two types: fundamental and transformative.

3.1. Good Governance

At its core, the notion of “good” in AI is intrinsically tied to the principle of good governance. Good governance in AI is not merely about functionality or efficiency; it embodies a commitment to accountability, ethical responsibility, and the equitable distribution of the technology’s benefits and burdens. Scholars and practitioners often describe this process as AI governance, with Responsible AI ending up as the output of these good governance practices. In this light, Responsible AI seeks to cultivate trust and acceptance among all stakeholders while proactively addressing the potential risks and unintended consequences of AI deployment [

37]. Good governance entails a multi-faceted approach integrating technical, legal, and ethical measures to ensure AI systems align with human values. Technically, it may involve advanced computational techniques such as adversarial debiasing, which removes the influence of sensitive attributes like race or gender from predictive models during data training and inferencing. Legally and ethically, it incorporates mechanisms like privacy policies, transparency notices, and accountability frameworks that establish a mutual understanding of risks and responsibilities between AI developers, organisations, and users.

However, while crucial, these initiatives often operate as “technical fixes” aimed at incrementally improving AI systems' performance, reliability, or trustworthiness. Although such measures can inspire user confidence and facilitate broader adoption, they often fail to address the deeper, systemic inequalities that underlie societal injustices. As Hoffmann [

38] critiques, these approaches frequently fall short of fostering the “structural change that social justice demands,” instead focusing on optimising existing systems within prevailing paradigms.

3.2. Social Good

Conversely, in a transformative sense, the notion of “good” extends beyond harm prevention to consider what should be made possible to meet human needs and demands [

36]. This shift moves from the principle of non-maleficence, which focuses on harm prevention, to the beneficence principle, which emphasises making positive contributions to humanity and the environment. The concept of good in AI thus broadens from the technical purview of “good governance” to the broader framework of “social good.”

Floridi et al. [

37] argue that AI for Social Good (AI4SG) enables the achievement of societal benefits that were previously unattainable, financially infeasible, or less efficiently realised. They define AI4SG as:

The design, development, and deployment of AI systems in ways that (i) prevent, mitigate or resolve problems adversely affecting human life and/or the well-being of the natural world, and/or (ii) enable socially preferable and/or environmentally sustainable developments (Ibid., pp. 1173-1174).

Cowls et al. [

3] advocate utilising the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a benchmark to gauge the contribution of AI to social good. Admittedly, such an alignment might be perceived as restrictive, given the myriad potential applications of AI that could foster societal benefits outside the SDG ambit. Yet, in defence of their stance, pronounced merits exist in harnessing the SDGs as a yardstick for AI4SG evaluations. These merits encompass well-defined parameters, an internationally agreed-upon framework, a foundation of extensive research and established metrics, possibilities for collaboration among SDG-oriented initiatives, and enhanced strategic and resource allocation planning.

Understanding the framing of “social good” in a local-specific context is essential, as a generalisation approach often glosses over the nuanced realities and contexts of the communities involved [

17]. When these specificities are overlooked, even well-intentioned efforts risk becoming superficial interventions, or worse, “good-AI-gone-awry” [

3], particularly if projects fail to integrate with local infrastructures, knowledge, and networks [

39]. Such oversights not only undermine the effectiveness of AI4SG initiatives but also perpetuate a misalignment between the technology’s potential and the lived realities of the communities it seeks to benefit.

3.3. Interconnectedness of the Two Notions

The fundamental notion of “good” in AI is inseparable from its transformative counterpart, which focuses on creating positive societal and environmental impacts. While Responsible AI initiatives may not inherently prioritise explicit social or environmental objectives, their absence creates a foundational void that prevents AI systems from realising their transformative potential. Responsible AI lays the groundwork by ensuring fairness, accountability, transparency, and respect for human rights—indispensable for cultivating trust and acceptance among stakeholders. Without these foundational elements, AI systems risk perpetuating harm, bias, or mistrust, undermining efforts to achieve broader societal benefits. In this sense, AI governance is the enabling condition for transformative applications, ensuring that AI systems are robust, ethically aligned, and capable of addressing pressing global challenges. Only when the principles of Responsible AI are deeply integrated into the design and deployment of AI systems can the transformative aspirations of AI for Social Good be pursued effectively.

4. The Precarity of Thai Farmers

Agrarian land constitutes 320 million rai (1 rai = 0.0016 km² or 0.16 hectares), or 32.7% of Thailand’s total land use. Approximately 66% of agricultural land is dedicated to cultivating key economic crops, including rice, cassava, maize, sugarcane, rubber, and palm oil. In 2024, Thailand’s agricultural exports reach 53 billion USD with rice remains the top export product [

40]. Economic values aside, the agricultural sector also houses 9.2 million registered farmers and 8 million households, which constitute 13.9% of the population and 29.0% of Thai households. With these significance in mind, Thailand is deeply rooted in agriculture.

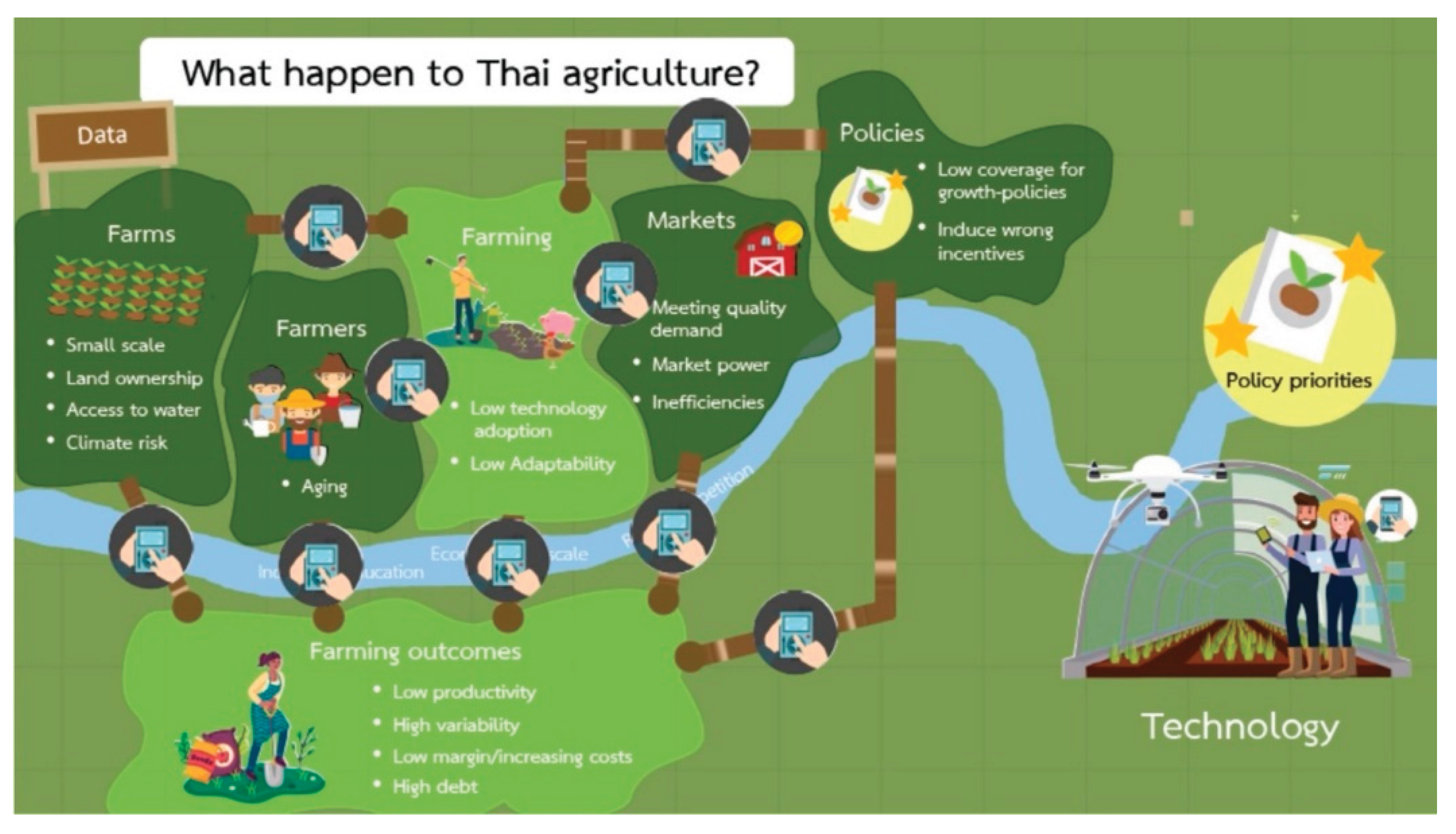

While this statement acknowledges agriculture as the ‘backbone of the country,’ it obscures a harsh reality. Beyond the fact that a significant portion of the population identifies as farmers, the sector offers little else to celebrate. Thai agriculture is marked by low productivity, declining competitiveness, an ageing and shrinking labour force, and a concentration of poverty within its demographic. These stark realities paint a picture of a sector fraught with challenges, making it a significant vulnerability within Thailand’s economy rather than a source of pride. In this section, I will delve into the multifaceted challenges Thai farmers face, examining the traps and contexts of deprivation that contribute to their continued marginalisation. These challenges are explored from multiple perspectives, including demographics, infrastructure, economic constraints, and policy-induced clientelism that collectively keep them teetering on the edge of subsistence—able to survive but unable to thrive or prosper.

4.1. Farmers’ Demographic

Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in the educational levels of Thai farmers. Yet, as of 2020, the predominant level of education completed by the majority remains at the primary level [

41]. This disparity suggests that individuals with higher educational achievements have been able to capitalise on structural economic shifts, transitioning to occupations outside of farming. In contrast, those with more limited education have continued to work within the agricultural sector. Off-farm migration, in search of better job opportunities and lifestyle, among the younger generation equipped with higher education is therefore inevitable. This makes the ageing population more severe in the farming sector. In 2020, elderly workers comprised 20% of the rural farm population compared with 7% in 2001 and 10% in 2010. Moreover, in 2020, young workers in the farming sector represented 30 % of all rural farm workers, a decrease from 56% in 2001 and 45% in 2010 [

41].

Attavanich et al. [

42] estimate that the ageing problem reduces farm productivity by 2.4% and 3.7% in 2017 and 2023, respectively. Jansuwan and Zander [

43] corroborate that older farmers are less inclined and motivated to invest in modern technology because of the need to save funds for their retirement, not to mention their digital illiteracy, which makes catching up with modern ag-techs even more difficult. As a result, even though farm households generally have the lowest income level of all rural households, income is lowest among households whose head is 60 years or older, indicating that ageing is a grave concern for productivity and income in rural farming households. Therefore, if the number of young farmers continues to decline, leaving only older farmers to handle increased farming workloads and risks, the agricultural sector's competitiveness, sustainability, and national food security will likely become a challenge.

4.2. Factors of Production

The prevailing predicament for Thailand's rural and small-scale farming households is restricted access to essential production inputs, such as water and farmland. Water accessibility remains a critical concern, with 58% of farmers lacking reliable access to water resources and only 26% of agricultural households having access to irrigation systems [

41], primarily concentrated in the Central, lower North, and Bangkok metropolitan regions. Farmers in the Northeast, home to the largest proportion of farm households, face the greatest exposure to drought risks due to significantly lower rainfall compared to other regions [

41]. The limited availability of water severely heightens the vulnerability of Thai agriculture, a situation likely to worsen with the increasing severity and frequency of droughts driven by climate change.

Compounding this issue is the fragmented nature of landholdings. The average size of agricultural land is 14.3 rai, but this figure masks significant disparities. Attavanich et al. [

42] highlight that in 2017, 50% of Thai farming households operated less than 10 rai, while only 20% held more than 20 rai. This skewed distribution underscores the dominance of small-scale farmers. Such diminutive farm sizes hinder the realisation of economies of scale, making it difficult for farmers to offset the high capital costs associated with modern agricultural machinery and PA technologies, such as tractors and unmanned spraying drones.

In addition to smallholding, land ownership remains precarious for many farm households, particularly in the central region. Research by Pochanasomboon et al. [

44] demonstrates that secure land ownership significantly improves productivity. For small and mid-size farms, complete ownership increases rice yields by 115.789 to 127.414 kilograms per hectare and 51.926 to 70.707 kilograms per hectare, respectively. These productivity gains are attributed to the enhanced liquidity and investment capacity afforded by secure tenure. Fully owned land has a higher appraisal value, enabling farmers to access credit and invest in machinery to boost productivity. Conversely, insecure land tenure constrains liquidity and stifles investment, perpetuating low productivity. Together, these elements constitute the poverty trap for Thai farmers from geographical and infrastructural perspectives.

4.3. Economic Conditions

In terms of income, a comprehensive agricultural economic survey conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MOAC) in 2021 revealed that the average net income from agricultural activities in Thailand amounts to just 78,322 THB per annum, or approximately 6,500 THB per month. In stark contrast, the annual income of a worker earning the minimum wage (328 THB per day, with 246 working days per year) is calculated at 80,688 THB, surpassing the income generated by farming activities. This disparity underscores the precarious financial situation of smallholder farmers in Thailand, who occupy the lowest rung of the nation’s economic hierarchy. Moreover, farmers’ incomes are inherently seasonal and subject to fluctuations in global commodity market rates, reflecting the occupation’s lack of income security and its vulnerability to external economic forces.

The challenges faced by Thai farmers have been compounded by historical price volatility in agricultural commodities. Following a historic peak in 2011, global agricultural commodity prices, particularly for rubber, plummeted dramatically. This decline coincided with a series of natural disasters between 2011 and 2015, which caused extensive damage to farm production across the country. The declining prices and adverse climatic events put immense pressure on farmers’ incomes. Meanwhile, key crop production costs have steadily risen over the past decade. According to Attavanich et al. [

42], labour, fertiliser, and land rent constitute the largest components of production costs. For Thai rice farmers, the economic burden is particularly stark: over the past 50 years, the selling price of rice has increased by a modest 3.9 times, while production costs have soared by an alarming 11.4 times [

41]. This widening gap between production costs and selling prices exacerbates financial stress for farmers, leaving them with shrinking margins and limited capacity to reinvest in their operations.

4.4. Policy-Induced Clientelism

Two-thirds of Thai farmers engage in monoculture, a practice often criticised by economists for yielding low-risk-adjusted returns. When farmers synchronously cultivate the same economic crops as their neighbours within a specific period, it leads to geographical and temporal concentration of production. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in rice farming, where 44% of the nation’s yield is harvested in November in the Northeastern region [

45]. Such concentrated production often results in market oversupply, driving down commodity prices and offsetting any potential benefits of economies of scale associated with monoculture. Addressing the interconnected issues of monoculture, soil degradation, and the poverty trap requires confronting a critical challenge: unconditional state assistance. Programmes such as price guarantees, income support, and input subsidies have been criticised for discouraging farmers from diversifying into alternative crops better suited to their land conditions. For example, state-backed incentives for rice production have been shown to skew farmers’ cropping decisions, deterring them from cultivating higher-value crops and contributing to the decline in agricultural profitability.

According to Lertrat [

46], the Thai government has relied on two primary subsidy mechanisms to bolster farmers’ incomes: price support for agricultural produce and harvest support based on farm size. The former guarantees farmers a price for their crops above market rates, while the latter provides additional payments tied to land size, primarily benefiting rice and longan growers. Between 2019 and 2022, these subsidy programmes exclusively targeted farmers cultivating major economic crops such as rice, rubber, cassava, sugarcane, oil palm, and maize, covering approximately 7.9 million households. During this period, the government allocated an average of 150 billion THB annually to these subsidies, exceeding the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives’ total budget of 126 billion THB in 2023. Much of this funding is sustained through loans from the BAAC, adding to the future fiscal burden.

Attavanich [

47] evaluated eight agricultural policies and found none of the unconditional support schemes improved net farm income. Three policies actively reduced farm income by disincentivising farmers from enhancing productivity. Despite mounting evidence of these programmes' ineffectiveness and unintended consequences, the government remains reluctant to reform its approach. Kanchoochat [

48] attributes this to entrenched clientelism. Historically, Thailand’s military-led governments exhibited an urban bias, marginalising the rural agrarian population. However, the political landscape shifted significantly with the advent of Thaksin Shinawatra’s populist agricultural policies. These initiatives were so influential that even subsequent military administrations (2014–2023) continued implementing large-scale subsidies and income support for farmers.

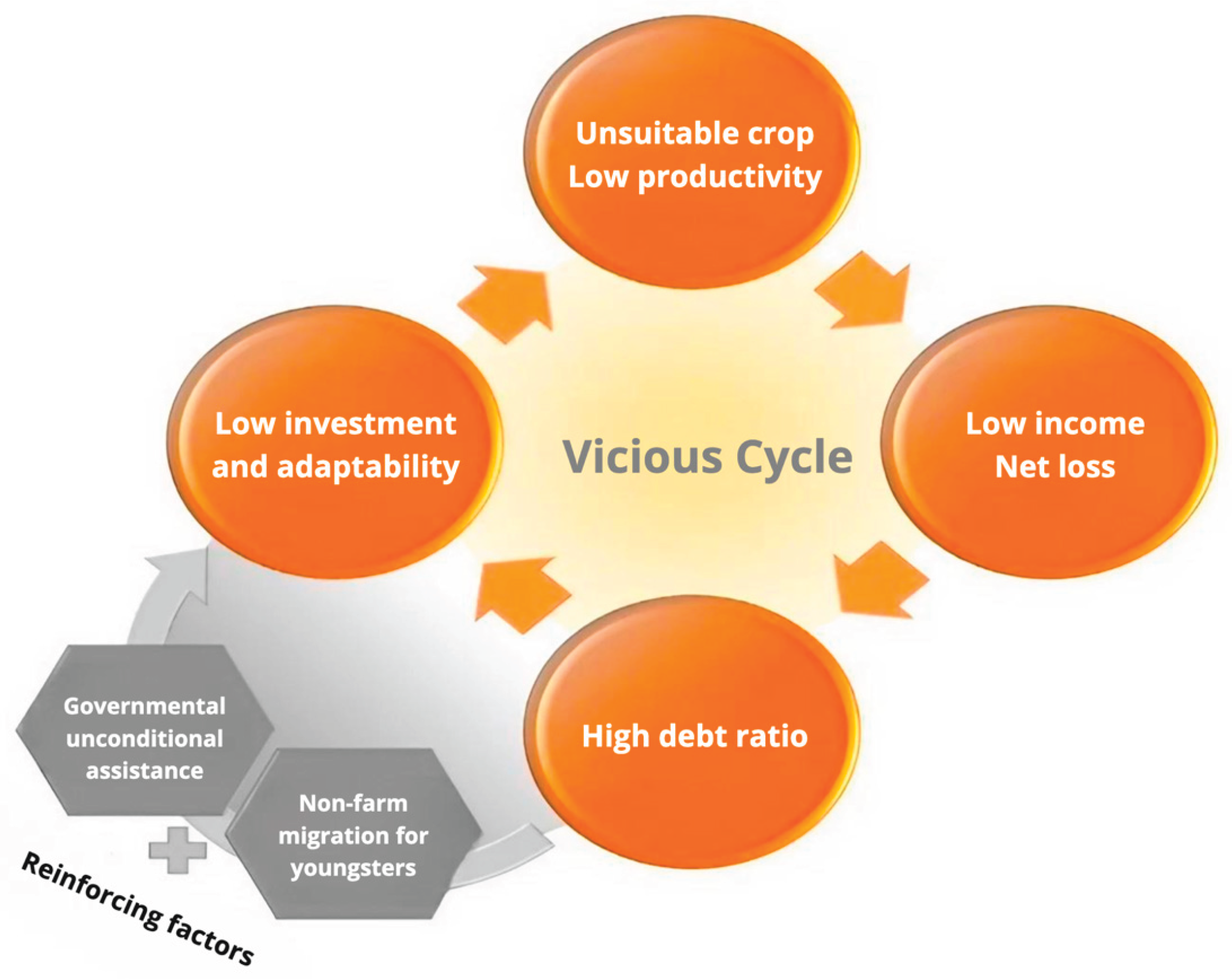

4.5. Vicious Cycle

Economists often regard “farmers produce unsuitable commodities” as the first step of wrong decision-making that spirals downward. Lertrat [

46] stresses that such production issues are not the fault of individual farmers alone. Often, they are compelled by government policies that dictate their actions. Because the government provides subsidies only for seven major economic crops, farmers are inclined to continue or even expand the cultivation of these crops despite market losses because the subsidies ensure a predictable and secured income. In contrast, shifting to other crops or professions would mean losing subsidy entitlements, in addition to shouldering new investments and risks. The government also provides subsidies without regard to the quality of the yield and production efficiency. If the government subsidises the traditionally cultivated low-quality produce as much as high-quality produce, which requires additional investment, knowledge, and technology, then the farmers would be dissuaded from adapting.

Figure 2.

Agricultural Poverty Trap. Source: modified from [

49].

Figure 2.

Agricultural Poverty Trap. Source: modified from [

49].

Despite billions spent annually on subsidy programmes, the majority of Thai farmers remain impoverished and heavily indebted. Thailand’s agricultural sector exemplifies a classic neoclassical economic paradox: government interventions, though well-intentioned to alleviate poverty, often perpetuate a cycle of dependency and poverty among the very farmers they aim to support. Economists and scholars do not advocate for the outright cessation of these programmes. Instead, they argue that such interventions should be conditional and strategically designed to promote capacity-building and empower farmers toward achieving long-term self-sufficiency. Kanchoochat [

48] has noted that these short-term remedial policies distract from pivotal systemic challenges such as the growing monopoly in the agricultural inputs market, land ownership complications, and the lack of reliable water resources.

In summary, the Thai agricultural sector faces various systemic challenges that impede its development and sustainability (

Figure 3). Farms are predominantly small-scale, grappling with issues of land ownership and water access, compounded by the increasing threats of climate change. Farmers face hurdles such as ageing demographics, low advanced technology adoption, and limited adaptability to modern farming methods, all of which impede productivity. Market barriers, which limit access to broader markets, force farmers to accept lower prices from intermediaries, while financial struggles due to consistent operational losses lead to a vicious cycle of debt. Current policies, including unconditional assistance and poorly structured subsidies, fail to alleviate indebtedness or improve productivity. They inadvertently promote low-value crop cultivation and monoculture, reducing the sector's agility to meet market demands and transition to sustainable practices.

5. Methodology

To understand the impact of Agricultural AI, this study will not only examine the applications already in use in Thailand’s agricultural value chain but, more importantly, explore how these technologies reach end users and the business models underpinning their deployment. Unlike prior studies [

34,

51,

52], which have focused primarily on the technological impacts, this research will delve into the service types and business frameworks that define these AI offerings. Examining the business aspects is crucial, as they reveal where power lies within the ecosystem. For instance, the extent of farmers’ influence often hinges on whether the AI services they use are offered free of charge or as paid services. If the services are free, the question arises: who is funding them? Paying customers typically holds greater sway in shaping the services than the beneficiaries. Investigating these business models provides insight into potential conflicts of interest and the critical question of who truly benefits from agri-tech innovations [

33].

Although Agricultural AI manifests in multiple forms [

53], I use the term “AI services” to reflect the business model, “AI-as-a-service” (AIaaS) that underpins both AI-embedded software and hardware. AI is often described as a service rather than a product because its functionality typically depends on subscription-based data analytics performed on the cloud platform. In this business offering, ATPs deliver AI as a service that users employ as a solution to address specific challenges. From hereon, I will refer to Agricultural AI as both a service and a solution interchangeably.

5.1. Scope of the Research

The development and adoption of Agricultural AI align with Thailand’s 4.0 policy, which signifies not merely the adoption of sophisticated technologies and practices aimed at bolstering productivity, efficiency, and sustainability but also embodies the nation's drive towards technological self-sufficiency. This marks a strategic move away from reliance on foreign technology. Going forward, these advanced solutions will be developed by Thai innovators/corporates for Thai farmers, ensuring that the technologies are closely aligned with the specific requirements and challenges of the country. This research will predominantly focus on ATPs that publicly and competitively offer their AI solutions, ensuring the examined technologies are comparable against alternatives and their impact is readily assessable. Hence, most of the Agricultural AI applications studied in this research will primarily come from ag-tech start-ups, with few exceptions from state agencies that are publicly accessible.

Unlike in the US, where there is an established leader in the agri-tech market like John Deere, large domestic and multinational companies have yet to control the agri-tech market in Thailand completely. For example, Microsoft had plans to introduce its PA services, FarmBeats, in Thailand, but the FarmBeats was terminated in September 2023. IBM engaged in a joint initiative with Mitr Phol on sugarcane farm management in 2019 but has yet to share any updates publicly. Kubota has a significant share in Thailand's agricultural machinery market, yet it prefers to be a strategic partner and investor in ListenField for PA services. Domestic telecom conglomerates like True and AIS have entered the fray with initiatives like TrueFarm and AIS iFarm, albeit as companies’ side projects. In short, while domestic tycoons and multinational firms are participating in the ag-tech market, they typically are not monopolising the agri-tech market outside their contract farming network.

The scope of this study is limited to crop cultivation. The exclusion of animal husbandry and aquaculture is because they utilise AI services from providers distinct groups from those providing for crop cultivation, which dominate the landscape per the observation of Attachvanich et al. [

51]. Considering that the data collected by the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperative (MOAC) indicates that a mere 11.5% of farming households partake in animal husbandry and aquaculture exclusively, and with agricultural land use predominantly allocated to field crops (70.8%) and horticulture (24.7%), this narrowed focus still comprehensively encompasses a large proportion of Thai farmers and the Agricultural AI services landscape.

5.2. Data Collection Method

The data collection for this study employed a combination of semi-structured interviews, event participation (including start-up demo days), and secondary data analysis. Interviews and event participation were conducted between May 2022 and September 2023, while some secondary data sources extended into 2024 during the thesis writing phase. The National Innovation Agency (NIA), specifically its Agricultural Business Centre (ABC) sub-unit, served as the primary point of contact. As the NIA maintains and constantly updates a database of ATPs in Thailand, it became a pivotal resource for research participant selection.

5.3. ATP’s Selection Criteria

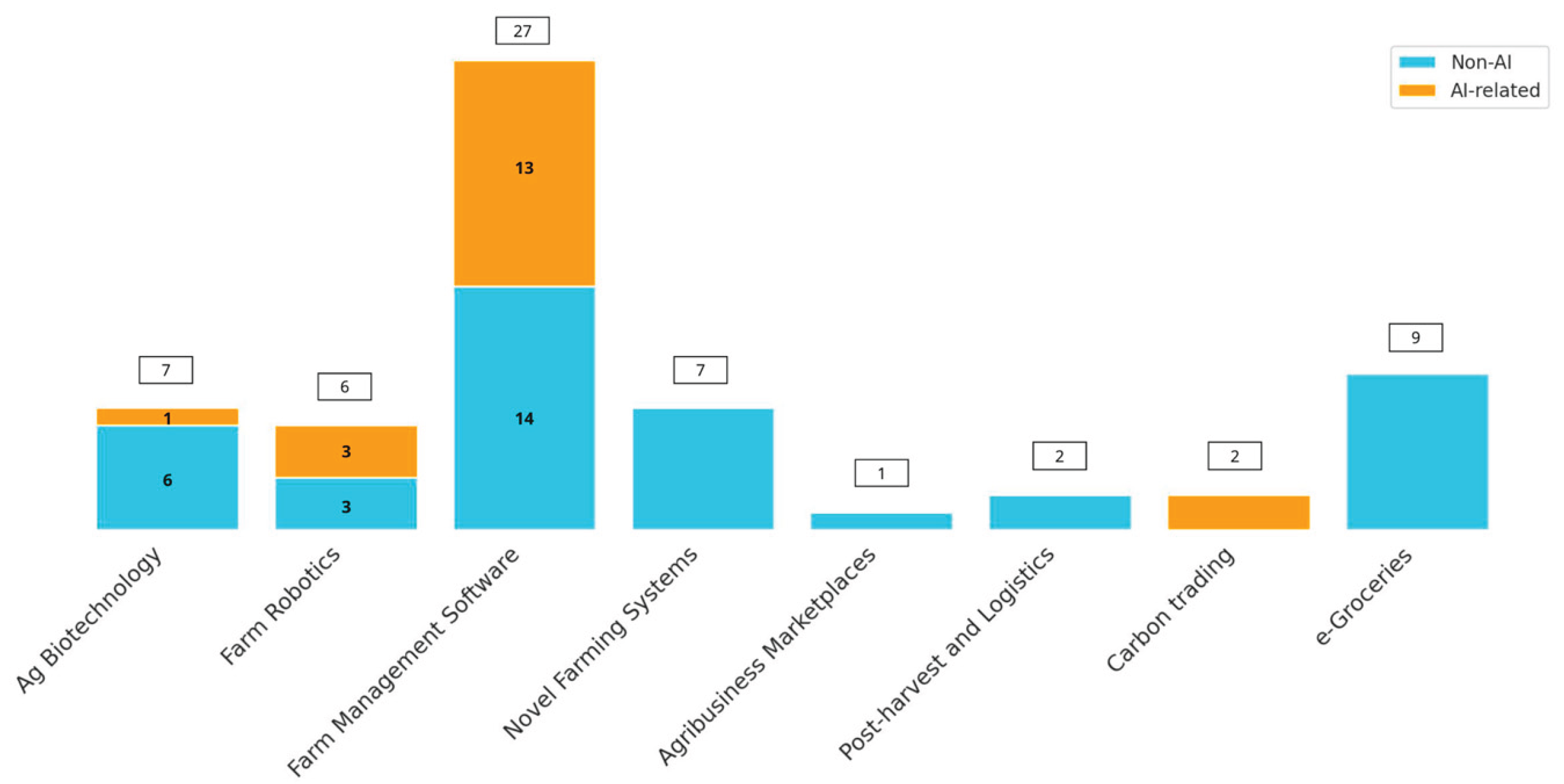

Out of the 61 ag-tech start-ups listed in the NIA database, as illustrated in

Figure 4, 19 firms prominently feature AI services as their primary solutions. Digital marketplaces and e-grocery platforms are considered AI-targeted ATPs, even though these platforms may utilise machine learning algorithms behind their platform operation. This exclusion is due to the limited direct engagement of AI with farmers, as their primary use lies in operational optimisation rather than mission-oriented objectives. Similarly, several farm management software solutions were not considered AI-related because they predominantly focus on data dashboards without incorporating advanced AI capabilities, such as analytics, prescription, or automation. In contrast, notable AI use case, that is not grouped by the NIA, such as carbon trading where AI is employed for measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural activities is included in the study.

Previous studies of Agricultural AI landscape in Thailand [

51,

52,

55] mostly focus precision agriculture and farming management platform, deducing their potential economic impact and reasons of slow uptake from the farming demographic. This study objective will broaden the variety of Agricultural AI used in the value chain and the scope of assessment from technology availability to its underpinned business model.

I classified the value chain of Agricultural AI into four phases: pre-harvest, farming, post-harvest, and retail.

The pre-harvest phase involves activities that prepare for effective crop cultivation, including soil analysis, seed selection, and weather forecasting.

The farming phase focuses on managing crops' growth cycles to optimise yields and resource usage.

The post-harvest phase encompasses processes such as crop processing, quality inspection, and assessing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated during farming activities.

The retail phase involves bringing agricultural goods to market, incorporating technologies for supply chain optimisation and food traceability.

Table 1 highlights the position of each selected ATP in the value chain and the data collection channel for this research. The data comes from primary sources such as the author’s interviews with the firms or observation of solution demos at attending events, as well as secondary sources such as interviews with media or companies’ websites and publications.

Table 2 provides additional details about each ATP’s profile, including the specific crops they focus on and the AI solutions they specialise in.

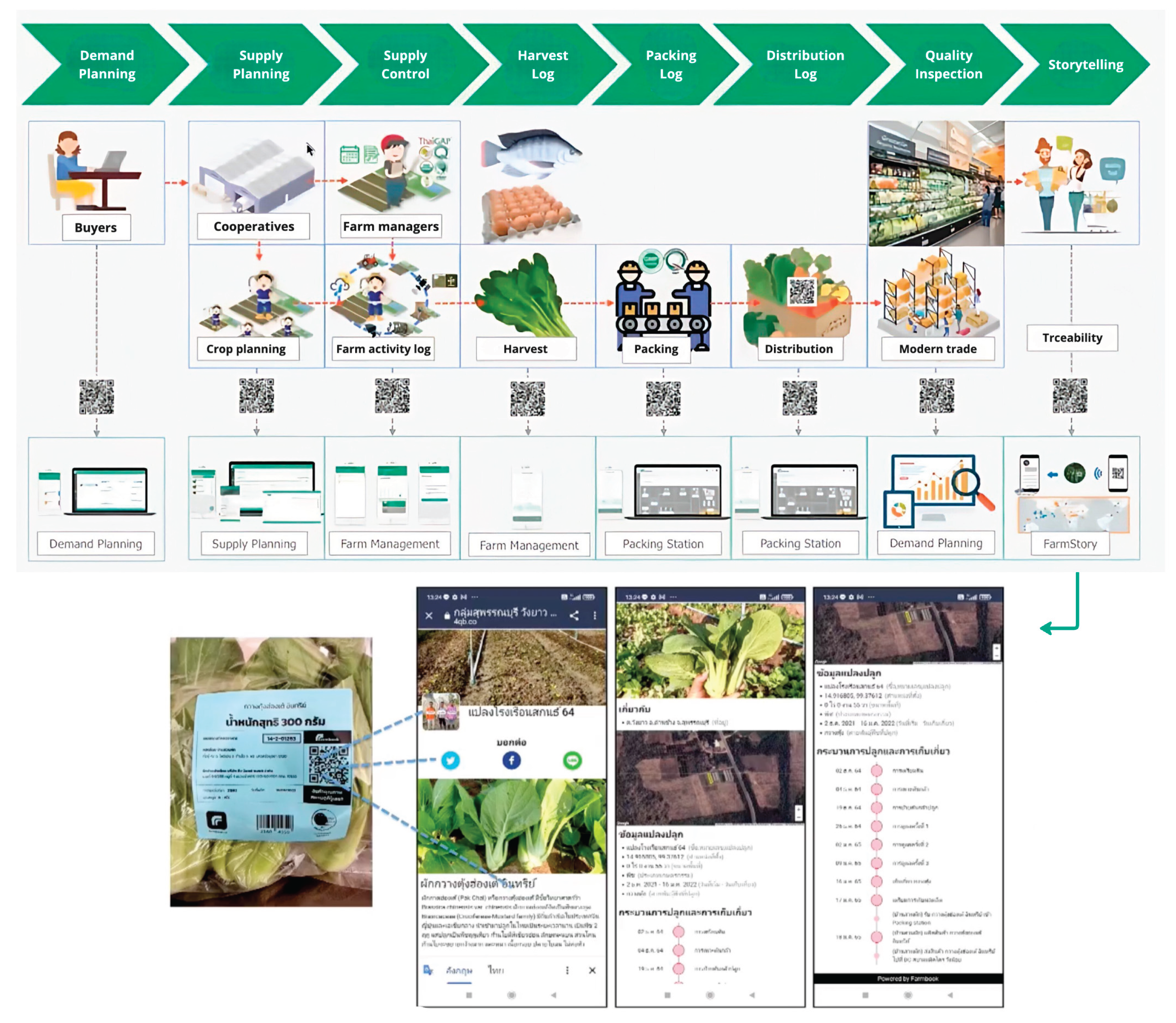

This study examines nine private providers (selected from 19 in

Figure 5) and two government projects, Rice Disease Linebot (RDL) and HandySense.

The engagement of ATPs in the retail phase is notably underrepresented in this study, with only Farmbook participating in this specific segment. This underrepresentation can be attributed to two key factors: first, there is a disproportionate concentration of ATPs operating on the crop production side of the value chain [

51]; and second, within the retail phase, most e-grocery platforms embed AI functionalities that have limited relevance or impact on the primary target group of this research—namely, farmers. Farmbook is distinct because its consumer-facing traceability feature, FarmStory, facilitates value addition to crop prices and leverages yield history in its credit solution, FarmFinn, both of which have a direct and tangible impact on farmers (see more in

Section 6.4).

5.4. Data Analysis

Most of the data analysed, whether primary or secondary, is in Thai. For author and media interviews, conversations were transcribed verbatim in Thai and then translated into English when used as quotes in the analysis. To ensure confidentiality, any personally identifiable information of participants was excluded during transcription, allowing the use of ChatGPT (model 4o) to assist with translations without privacy risks.

The analysis is structured around five key questions that provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the ATPs and their AI solutions:

Problem Identification: What problems is the ATP’s AI solution designed to solve?

Technical Implementation: How does the AI solution address these problems from a technical standpoint?

Business and Revenue Models: What is the underlying business or revenue model that supports the AI solution?

AI Ethics and Governance: What ethical principles or governance processes has the ATP adopted in developing and deploying its AI solutions?

Empirical Social Good Impacts: What are the observed social good impacts of these AI solutions on individual farmers and the agricultural sector at large?

Qualitative data from interviews and observations were coded using thematic analysis in NVivo 14. Key themes were identified based on the five guiding questions, with attention to recurring patterns, unique insights, and deviations. Quantitative data, where available, were used to complement and contextualise the findings.

7. Cost of Services

Technological merit alone does not determine impact; access is mediated by the business model behind each ATP. Of the eleven initiatives reviewed, only the three farm-automation services oblige farmers to pay directly for sensors, control boards or annual subscriptions, and their adoption remains confined to a few hundred users in high-value horticulture (

Table 3). Every other service shifts the cost burden onto better-capitalised actors—export mills, modern-trade retailers, carbon-credit buyers or the state—allowing farmers to enrol free of charge. With no upfront cost, farmers onboarding significantly rise to the level of ten thousand, with Ricult reached a remarkable number of 600,000 users in its farm advisory, Baimai, application. This goes to underscore how relevant cost structure and service delivery model are to Agricultural AI impact assessment.

7.1. Data Aggregator and GP-Sharing

Free services are not entirely cost-free for farmers. Where the business model relies on data aggregation and brokerage, farmers “pay” with their person, behavioural, and agronomic data. While it is true that all AI providers collect data from users, data aggregator collector data more extensively for the sake of “connecting” farmers to other well-capitalised stakeholders (e.g. financial institutions, millers) rather than purely for “improving” their models and service deliveries. In the media interview Ricult [

65] explains its business as similar to food delivery companies. The platforms make money by charging gross profit share (GP) from the restaurants. That's a very similar concept. I don't charge farmers, but I do connect them with other service providers such as banks, insurance companies, vendors, and transport services. Then, we charge the GP in the middle.

Effectively, farmers pay for prediction and analytics services by contributing their personal and farm activity data, which is commodified for profiling and monetisation. In return, farmers benefit from improved access to formal credit, as their transactional records and yield histories are shared with financial institutions via the ATPs.

Farmers’ familiarity with sharing data for government assistance programmes also makes them more open to providing data to ATPs if it increases profitability. For instance, Ricult’s

Bai Mai system integrates big data to monitor local product prices, helping farmers decide where and when to sell their crops for the highest returns. Ricult [

65] illuminates that: we met some farmers in Saraburi who drove across town to Khorat [roughly 150 km apart] just to sell their crops because they knew [they were getting a better price and] it was worth the transportation time and cost. We give them an opportunity. We give them data. So that they can make a better decision and get a better price.

This willingness contrasts with attitudes in countries like the United States [

71] and Australia [

35], where concerns about data privacy create significant barriers. In Thailand, reluctance to adopt precision agriculture technologies is more commonly linked to the cost and doubts about digital technologies’ effectiveness [

51,

52] rather than data-sharing concerns.

Although both Farmbook and Ricult provide free-to-access, supply-and-demand matching, their business architectures diverge markedly. Farmbook integrates software with capital-intensive infrastructure: it franchises traceability-enabled packing stations (complete with cold-chain and grading equipment) and markets “Food Story” produce to modern-trade retailers. This model lets Farmbook capture its gross-profit share downstream, drawing revenue from retailers and consumers willing to pay a premium for food-safety guarantees, provenance, and just-in-time inventory. Ricult, by contrast, is an intentionally asset-light data aggregator. It monetises satellite imagery, farm-level records, and transactional data by selling crop-supply forecasts to mills, generating leads for input vendors, and offering alternative credit-scoring to financial institutions. Ricult thus exemplifies the pure data-broker model in Thailand’s Agricultural-AI landscape—optimising for scale, near-zero marginal cost, and multi-sided data monetisation.

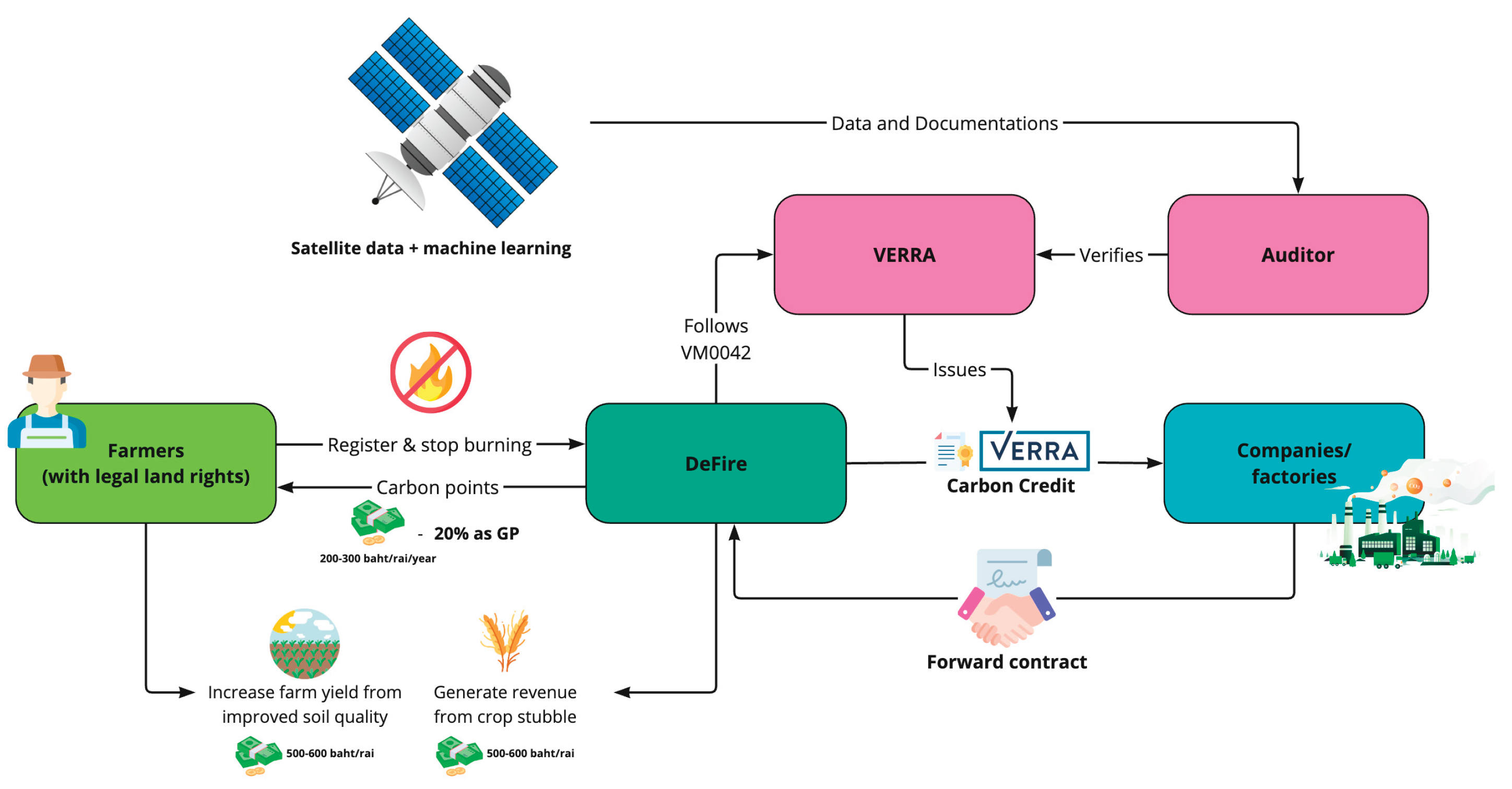

Another form of GP sharing comes from carbon credit trading, where the revenue of the carbon MRV platform is generated through operational expenses deducted from the sales of carbon credits—approximately 20% of the total credit value.

7.2. State Funding

State funding remains a pivotal lever for reducing or eliminating farmers’ out-of-pocket costs for Agricultural-AI services, and it can be deployed through several complementary mechanisms. First, direct budget appropriations cover the full development and operating expenses of certain services, as in the RDL, which the NECTEC maintains entirely at public expense. Secondly, agencies can release open-source, licence-free platforms and hardware schematics—HandySense being the leading example—so that farmers need purchase only low-cost micro-controller boards, sensors and actuators, or adapt equipment they already own. Third, the state can take an equity or procurement stake in start-ups whose technologies align with policy objectives; the BAAC’s backing of Infuse’s enables free, AI-based insurance claims processing for growers. By absorbing development costs or subsidising deployment in these ways, government programmes expand the reach of Agricultural-AI solutions while minimising the financial burden on resource-constrained smallholders.

However, state funding also carries certain limitations. Firstly, while subsidies from the state typically enhance affordability, they do not necessarily guarantee scalability. For instance, despite being offered at no cost to farmers, the publicly funded Rice Disease Linebot serves only around 3,500 users—approximately two orders of magnitude fewer than its privately operated counterparts. Secondly, although open platforms like HandySense are more cost-effective (ranging from 3,100 to 9,095 THB for a ready-to-use setup) compared to proprietary systems such as Farm Connect Asia (approximately 20,000 to 35,000 THB), they pose significant barriers for farmers who lack technical skills. The installation and ongoing maintenance of these open systems demand proficiency in electrical engineering and coding.

7.3. Charging Wealthier Stakeholders

Another method to shift costs away from smallholders is to bill capital-rich stakeholders—food processors, millers and exporters—for the service. Crop-quality inspection illustrates the approach. EasyRice, for example, supplies hyperspectral scanners that cost about 100,000 THB per unit, a sum far beyond the reach of most small and mid-sized rice growers. Consequently, farmers can use the technology only when they belong to a well-organised co-operative or sell to mills and exporters that have purchased the scanners. Although farmers do not pay directly, they still get the benefit due to grading now takes three to five minutes instead of hours, cash is released sooner, and higher returns for those producing premium-quality milled rice or other desirable varieties.

However, a critical drawback of this model is its limited accessibility. According to EasyRice [

60], its customer base includes over 235 paying clients, predominantly rice millers, Thai exporters, and foreign importers. This limitation still leaves majority of farmers, outside its network and therefore subject to conventional, often opaque price assessments by local middlemen.

8. Good Governance Analysis

Responsible AI aims to ensure that AI applications align with societal values and goals by addressing their social, economic, and environmental impacts [

72]. In his meta-analysis, Ryan [

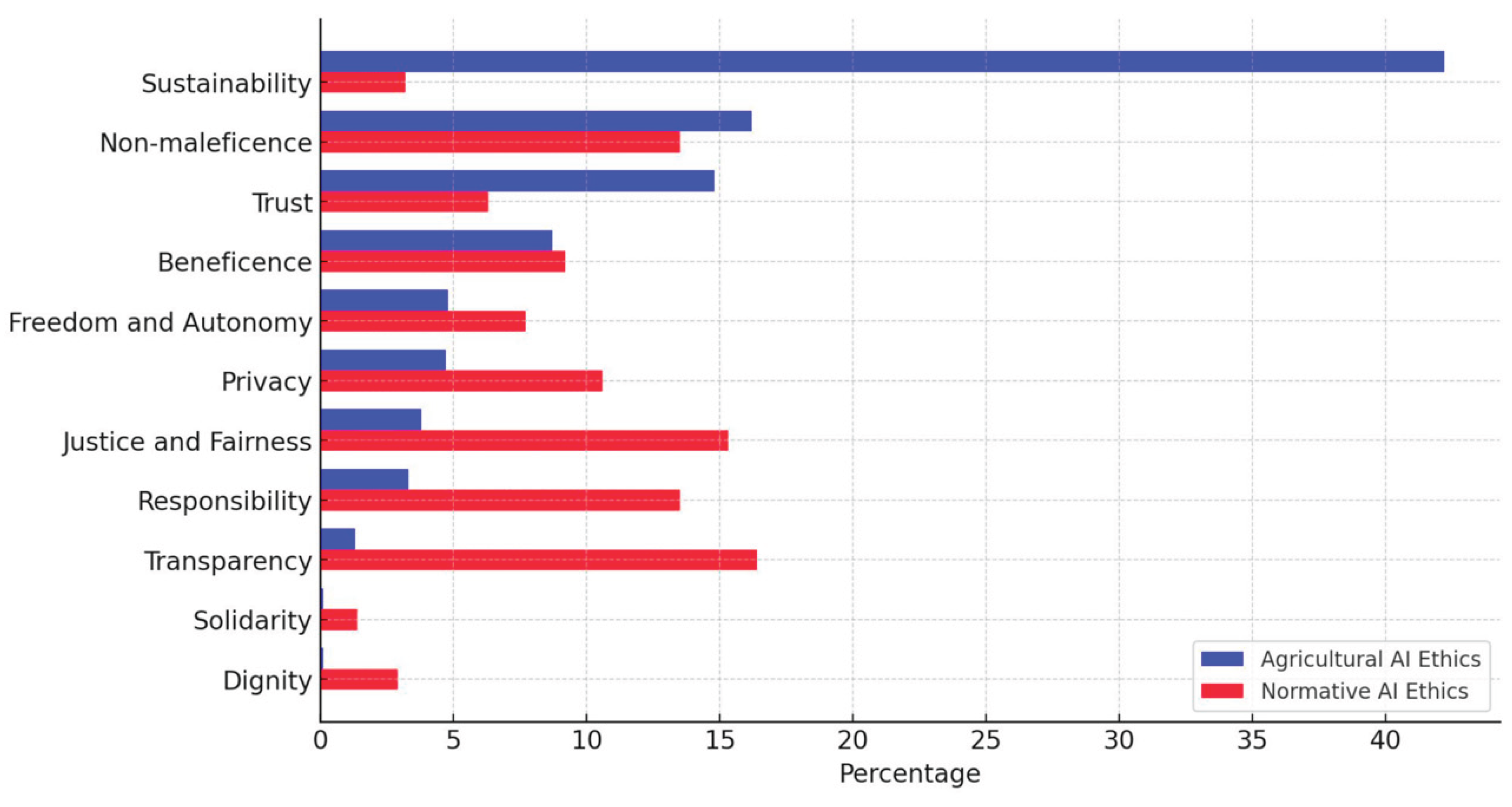

53] highlighted the differences in how ethical concerns and principles are framed and prioritised in Agricultural AI and normative AI ethics.

Figure 10 illustrates that sustainability emerges as a central theme in the ethical discourse surrounding Agricultural AI—a sharp contrast to its relatively lower priority in broader AI ethics frameworks. Coupled with the relatively high emphasis on beneficence, Ryan’s findings further illustrate why the use of Agricultural AI is highly accentuated on delivering social good impact.

Another insight is pragmatism over procedural ethics in agricultural AI. Adoption on farms is decided by functional trust: “Does the model improve yield and reduce risk?” Hence trust and non-maleficence rank highly, whereas abstract procedural duties (i.e. explainability audits, bias assessments) receive less attention compared to normative AI ethics. This pragmatism, while understandable, risks leaving structural power imbalances unexamined—for example, data asymmetries between smallholders and ATPs [

72]. This further explains the under-representation of justice-oriented principles, such as justice, fairness, responsibility, and transparency in Agricultural AI.

To testify Ryan’s meta-analysis, which is predominantly western-oriented, this section examines the prevailing norms in “good governance” of Agricultural AI in Thailand. Because

Section 9 will assess outcome-oriented principles such as sustainability and beneficence, this section concentrates on the principles critical for safeguarding farmers’ rights: privacy, autonomy, reliability, transparency, and accountability.

8.1. Privacy

Privacy has consistently been a primary ethical concern in AI, though it appears to be less emphasised within the domain of Agricultural AI, as observed by Ryan [

53]. This stems from the assumption that most data collected pertains to non-sensitive, farm-related information. Comparing privacy practices across different ATPs is challenging for several reasons. Many services are not publicly available as mobile applications with easily accessible privacy policies. Instead, access to privacy notices for proprietary software is often restricted until after a purchase. Despite these limitations, an analysis of the available terms and conditions and privacy policies from ATPs such as

Ricult (a data aggregator provider), compared to

Infuse (a specialised service provider), reveals notable differences in their data collection and usage practices (

Table 4).

ATPs routinely require baseline identifiers—name, national-ID number, postal address, e-mail—and geo-coordinates of farm plots to deliver site-specific services. Both Infuse’s Malisorn and Ricult’s Bai Mai therefore mirror mainstream agri-tech practice. Where they begin to diverge is in the breadth and granularity of the “digital exhaust” they each regard as commercially valuable.

Infuse logs standard website-traffic metrics (pages viewed, search terms) primarily to gauge product demand and tailor in-app promotions. Beyond this it captures device diagnostics—hardware model, OS version, mobile-network data—and, with the user’s permission, the camera roll, allowing it to ingest photographs and videos farmers submit as evidence of crop damage or for profile personalisation. The policy does not record session-time or pointer-movement analytics and makes no explicit reference to behaviour-based advertising.

Ricult, by contrast, applies the playbook of e-commerce and social-media firms. In addition to the usual traffic counters, it records dwell time on each page, scrolling patterns and mouse-movement traces. Such fine-grained telemetry underpins Ricult’s role as a data aggregator: the company can build probabilistic profiles that support targeted offers—e.g. soft-loan adverts embedded in Bai Mai—and can monetise anonymised cohort insights with third-party partners. Ricult is explicit that only aggregated statistics leave its servers (for instance, “500 men under 30 who clicked an advert in one day”), thus lowering re-identification risk while still enabling behavioural advertising revenue. Neither provider seeks highly sensitive attributes—biometrics, health data, ethnicity or political opinions—so the overall sensitivity level remains moderate.

From a compliance perspective, Ricult again goes further. Its notice enumerates Personal Data Protection Act’s (PDPA) data-subject rights, prescribes a five-year erasure horizon for inactive accounts, and appoints a Data Protection Officer. Infuse states the lawful bases for collection and lists security safeguards, yet omits a retention schedule, cross-border transfer clause, or DPO contact. Taken together, the comparison portrays Ricult as the more data-hungry—yet also the more PDPA-mature—ATP.

8.2. Autonomy

As Floridi et al. [

74] describe, autonomy is the ability to make decisions independently based on one’s discretion. Farmers’ autonomy is highest when they are direct users of AI technologies and bear the financial costs themselves (

Error! Reference source not found.). For instance, in precision farming, farmers can configure pre-set conditions, such as timing and climate triggers, for automated irrigation systems and retain the ability to deactivate the system whenever necessary. This level of control empowers farmers to adapt AI solutions to their specific needs and preferences. However, higher financial investment in AI technologies does not always translate to greater user control. For example, IoT systems with open-source platforms like

HandySense allow farmers to choose their connected hardware and determine where their data is stored and processed. In contrast, proprietary systems may restrict these choices, limiting farmers’ control in return for better ease of use. When farmers are not the financial contributors to an AI service, their autonomy diminishes. For instance, in rice quality assessments or carbon MRV processes, farmers have limited influence over the methodologies and rebuttal of the outcomes.

8.3. Transparency

Farmers’ autonomy is inherently linked the principle of transparency as it enables insights and understanding necessary for effective accountability [

75] from ATPs and due discretion exercised by farmers. Transparency operates on multiple levels. At the institutional level, it involves openness about policies, actions, and laws to promote communication, collaboration, and trust among stakeholders [

28]. At the system level, transparency pertains to the interpretability of AI systems, allowing users to understand the decision-making processes and the factors influencing those decisions [

76]. Transparency in Agricultural AI predominantly manifests at the institutional level, driven by legal requirements, such as PDPA.

Transparency is also fundamental for managing user expectations of technology. It anchors users to a realistic understanding of the technology’s capabilities and limitations [

77]. None of the studied ATPs claim perfect accuracy for their AI systems, highlighting their commitment to setting clear expectations. EasyRice [

60] claims to achieve 95% accuracy.

Ricult claims 90+% accurate crop scan but advises farmers to retain human judgment in conjunction with AI assistance [

78]. Similarly, NECTEC’s

Strawberry Disease Linebot is transparent about its current limitations, explicitly stating that its disease detection accuracy ranges between 60–70%, which is way below its counterpart service,

Rice Disease Linebot. By openly communicating its capabilities and areas for improvement, NECTEC sets a precedent for honest and responsible use of AI, fostering trust while acknowledging the ongoing development of its systems.

8.4. Reliability

Reliability in AI ethics involves ensuring that AI systems are dependable, consistent, and capable of performing as expected under various conditions. For Agricultural AI, ease of use is a critical component of reliability, particularly given that many farmers—the primary users—are older and less familiar with digital technologies. Established ATPs, such as ListenField, Ricult, and Farmbook, have invested heavily in human-centred design. By incorporating continuous feedback loops, these companies prioritise user experience and strive to make their applications intuitive and accessible to a less tech-savvy audience.

Reliability is further reinforced through familiarity and simplicity [

79]. Research conducted by the Department of Rice and institutional partners [

80] found that farmers’ use of mobile applications decreases with age and that LINE (similar to WhatsApp in the West) is the most widely used communication application across all age groups. Recognising this, ATPs such as

Techmorrow and the

RDL have embedded their services within the LINE platform. This strategy reduces software development costs and lowers the learning curve, enabling farmers to adopt the technology more easily without significant time or effort.

Another aspect of reliability lies in the consistent delivery of accurate results. Many ATPs exercise caution when launching AI services, ensuring the systems meet stringent accuracy thresholds before widespread deployment. For example, the Rice Disease Linebot can detect up to 16 rice diseases, but general users can currently access diagnostics for only ten diseases. The remaining six are reserved for beta testing until their detection accuracy matches the initial offerings’ 90–95% benchmark. Once this standard is achieved, the service will expand its official diagnostic capabilities.

8.5. Accountability

While there is an expectation that transparency in processes and policies will hold firms more accountable, a detailed examination of ATPs’ end-user agreements reveals a contrasting reality. At the initiation of service usage, users are mandated to accept the Terms and Conditions (T&C) that absolve the companies from liabilities potentially caused by their AI systems. For example, Ricult's T&C explicitly disclaims: any liability for damages, including direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages, losses, or expenses resulting from errors, omissions, interventions, data deficiencies, suggestions, advice, or methods related to agricultural operations or cultivation. Users bear the risk of relying on such information, and Ricult does not verify, endorse, or guarantee the content, accuracy, opinions, or other connections made available [on] the platform.

Farmbook's T&C similarly declare that the company will not be held responsible for: any direct or indirect losses, including but not limited to loss of use, profits, revenue, data, goodwill, or anticipated savings. This includes indirect, incidental, special, consequential, or exemplary damages arising from the use or inability to use the site or services, even if Farmbook has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

Based on these clauses, holding ATPs accountable for errors and financial or reputational losses remains challenging.

The empirical evidence of Agricultural AI substantiates the hypothesis that regulatory frameworks establish a baseline standard of good governance in AI. Legislative mandates are instrumental in enforcing AI ethics, a capacity in which standalone guidelines are notably deficient. The operationalisation of AI accountability similarly encounters significant challenges without clear legal directives regarding responsibility for faults and errors. This issue is compounded by the prudent legal drafting employed by ATPs, which often includes clauses disclaiming liability for any losses or damages, be they direct or indirect.

8.6. Good Governance Diagnosis

Thailand’s Agricultural-AI landscape exhibits a persistent asymmetry between functional and procedural trust. Functional trust thrives because farmers can readily observe that yield-forecast models and advisory apps “work” in practice: predictions are accurate, interfaces fit local digital habits, and tangible gains—higher yields, better market access, improved cash-flow—quickly accrue. By contrast, procedural trust lags. The algorithms remain opaque and “no-liability” clauses in end-user agreements shield providers from redress. Interview evidence reinforces this pattern. ATPs concede that commercial success hinges less on watertight privacy notices or algorithmic explainability than on delivering visible, field-level benefits. Consequently, reliability—expressed through accuracy thresholds, robustness testing, and easy-to-use interfaces—is marketed vigorously, whereas deeper procedural safeguards receive cursory attention. To their credit, ATPs practice a narrow form of accountability: new features enter production only after surpassing stringent performance benchmarks, and most companies avoid overstating accuracy rates. Yet in the absence of explicit AI-liability statutes, smallholders—often digitally under-resourced and, in many cases, merely downstream recipients rather than direct users—possess scant legal recourse when erroneous outputs inflict economic harm.

9. Social Good Impact Analysis

The agri-tech ecosystem report by the NIA [

81] states that addressing societal issues is the primary motivation for 82% of agri-tech founders, closely followed by profitability at 80%. While claims of prioritising societal goals over or equal to financial performance might be dismissed as public relations tactics, they may hold genuine significance for many ATPs, particularly start-ups. Addressing agricultural challenges requires focusing on rural populations and their specific needs. This is particularly difficult when working with smallholders, who often lack the purchasing power and the willingness to adopt innovations from lesser-known ventures [

52]. These barriers complicate the monetisation of services and the adoption of advanced technologies.

From a financial perspective, it would be more straightforward for agri-tech start-ups to provide AI solutions to large agri-businesses. Examples of this approach include Sertis’ (an AI start-up) partnership with CPF (the largest agribusiness and food conglomerate) [

82] and IBM’s collaboration with Mitr Phol (the leading sugar producer in Asia) [

83]. However, many ATPs examined in this research have chosen to engage with smallholder farmers, often at significant financial and operational trade-offs. From this lens, many ATPs are genuinely committed to making a social good contribution. However, what remains underexplored is a nuanced understanding of what “social good” means in the context of Thai agriculture.

9.1. Agricultural AI x SDG

As discussed in

Section 2, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a standardised framework for evaluating AI’s contributions to social good (Cowls et al., 2020). My analysis reveals that Agricultural AI contributes to eight SDGs—Goals 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 (

Figure 11). These contributions vary in scope, intent, and immediacy. Some SDGs, such as SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), are addressed primarily because AI-driven solutions are often developed and deployed as part of agri-tech initiatives that generate employment and modernise the agricultural sector with innovative tools. These contributions are largely a by-product of the industry’s growth rather than a direct outcome of AI applications benefiting farmers.

Other SDGs, such as SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), represent tangible and intended outcomes of engaging with Agricultural AI. For instance, AI-driven precision farming can optimise resource use, enhance yields, and reduce agricultural waste, directly contributing to poverty alleviation, improved food security, and climate resilience. However, certain goals, such as SDG 5 (Gender Equality), are less directly impacted by current Agricultural AI implementations. These goals require deliberate and targeted interventions to ensure that marginalised groups—such as female-headed farm households practising monoculture on small plots—can access and benefit from AI technologies.

9.2. Empirical Translation of Social Good

Because most ATPs do not frame their outcomes in SDG language,

Table 5 re-maps the impacts they do report—productivity, income, finance, agri-waste, food safety, net-zero, and food waste—to the corresponding SDG targets, creating a practical “translation bridge.” One goal is conspicuously absent: SDG 5 (Gender Equality). None of the initiatives examined sets explicit gender metrics. Ricult merely notes in a USAID brief [

84] that most Thai farmers are women, while Spiro Carbon remarks that female growers earn extra income from carbon-credit trading. In both cases, the benefits to women are incidental rather than the product of intentional, gender-responsive design.

The process of validating the impacts addressed by each ATP hinges on two criteria: first, whether their services fulfil the specified theme, and second, whether the positive contributions are a deliberate target of the ATP or simply byproducts of service usage not explicitly promoted by the ATP. This distinction is crucial because direct impacts reflect intentional contributions that are typically internalised, measured, and promoted. In contrast, indirect impacts represent positive externalities that may not be systematically monitored or leveraged. Without regular measurement and progress tracking, the sustainability and scalability of these indirect benefits remain uncertain. Using net-zero contributions as an example, precision farming enhances resource efficiency, curtailing excess input waste. Nonetheless, without a comprehensive monitoring system, it is challenging to determine how much this reduction contributes to the broader decarbonisation goal.

9.2.1. Explicit Economics Focus

Table 6 indicates that ATPs’ direct and quantifiable contributions to social good are predominantly economic. Their primary objectives involve reducing input costs, enhancing yields, and improving market connectivity—all of which collectively aim to increase smallholder incomes. Indeed, nine out of eleven ATPs explicitly assert a direct and positive impact on farmers’ incomes, with reported farmer-level improvements in yields, prices, or net profits consistently ranging between 15% and 22%. A notable exception is

Infuse, whose business model emphasises processing insurance claims in accordance with government policies, thus categorising its contribution within the financial sector rather than direct income enhancement. Given that agriculture consistently ranks as Thailand’s lowest-remunerated occupation, it is unsurprising that most ATPs define their contributions to social good primarily through their capacity to uplift smallholder incomes.

This economically oriented approach not only characterises ATP practices but also mirrors the priorities of state actors facilitating farmer-ATP partnerships. For instance, promotional materials from the NIA’s AgTech Connext [

91] highlight agricultural technologies through slogans such as “making work easier, improving productivity, reducing costs, and increasing income.”

Within this framework, sustainability appears as a secondary consideration in Thailand’s agricultural context. Although ATPs involved in farm advisory and automation regularly document and advertise their economic impacts, quantifiable data on how precision farming reduces input usage and contributes to better preservation of natural resources remain noticeably underreported.

ListenField is the only farm management platform that reports a reduction in fertiliser use by 25% in pilot communities [

92], thanks to its real-time soil nutrition analysis and crop health monitoring, which help farmers apply fertilisers and chemicals only where and when needed.

9.2.2. Hybrid Sustainability Model

Contrary to the findings Ryan [

53] where sustainability often occupies a central role in the discourse on Agricultural AI, the environmental focus in Thailand frequently exhibits a “hybrid” model [

20], where, to progress a transformative agenda and out-of-convention practices, it needs to be justified through economic benefits. The logic is straightforward—farmers needs to “do well” financially when they are expected to “do good” for society.

A clear illustration is

Ricult’s Agriwaste scheme. Post-harvest, smallholders typically torch cassava rhizomes because baling and hauling them costs time, labour, and cash. Ricult solves the incentive problem: it aggregates residues from nine provinces, guarantees collection, pays within 48 hours, and lifts monthly farm income by about 18,000 THB [

93]. Farmers now have a clear incentive to bale residues instead of lighting them, overcoming the labour- and transport-cost barrier that made burning the cheapest option. A similar incentive architecture underpins

Spiro Carbon and

DeFire, which reward climate-smart practices with carbon-credit revenue.

Greenwashing is always a concern when strong economic motives drive sustainability-oriented initiatives. In this regard, Spiro Carbon is committed to upholding the credibility and transparency of its credit conversion to mitigate greenwashing.

When the farmer registered a 50-rai plot, the expectation was to receive full credit for the total land use. However, in reality, the 50 rai aren’t all on the same level, with low-lying and elevated areas, which causes the soil to dry unevenly. After we used AI to analyse the images, only about 17 rai were undergoing wetting and drying cycles.

Beyond honest dialogue with farmers, Spiro Carbon mints an NFT (non-fungible tokens)—essentially a tamper-proof digital certificate—each time it completes a monitoring cycle. Because every credit issued later carries the smart-contract address of its underlying NFT, buyers and regulators can click the address in a public blockchain explorer and inspect the supporting evidence that justifies the claimed tonnes of CO₂e.

In return for thorough carbon verification, the company does not ask for a land ownership or lease contract as part of the registration process. In the interview, Spiro Carbon states that:

Greenhouse gas reductions derive from farming activities, not from land ownership; consequently, the reward for such positive action should go to the farmer rather than the landowner, who may be a different person altogether.

This criterion would benefit elderly, female, or disabled farmers who often lack formal land titles. Spiro Carbon's deliberate commitment to environmental and social justice slightly pushes the horizon of how social good can be operationalised in the sector.

9.2.3. Influences on Environmental Goal Setting

The environmental focus among Agricultural Technology Platform (ATP) providers in Thailand exhibits a noticeable divergence, strongly correlated with their engagement with international stakeholders. A clear trend emerges: ATPs with significant international exposure tend to demonstrate a stronger commitment to environmental goals compared to those primarily confined to the domestic market.

This trend is particularly evident among farm management platform providers.

ListenField, which benefits from support from the Japanese government and operates across five countries, has set an ambitious target to reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions by 48% by 2030 relative to 2021 levels [

66]. Similarly,