1. Introduction

Organizations are environments ripe for conflict [

1]. Traditional management approaches see conflict as harmful and a threat to productivity. However, contemporary thinking recognizes that conflicts, when well-managed, lead to increased productivity, creativity and innovation [

2,

3,

4]. When interpersonal conflicts become dysfunctional, they contribute to the perpetuation of abusive practices within healthcare organizations. Normalizing and not penalizing these practices normalizes their existence [

5].

The concept of silent epidemics [

6] becomes particularly relevant when it is observed that, in certain organizational cultures, negative behaviors are naturalized and even considered acceptable as an integral part of the professional socialization process. Often, these behaviors are understood as a rite of passage inherent to joining the team or adapting to institutional dynamics.

These behaviors manifest themselves in the form of hostile, unruly and unprofessional attitudes [

7], and are widely recognized in the literature as negative behaviors [

8,

9]. However, there is considerable conceptual heterogeneity in the terminology used to describe these dynamics, which are also referred to as inappropriate attitudes or adverse social behaviors [

7,

10].

Although the literature presents a variety of related constructs, this review relies on the definition proposed by Nemeth et al. (2017). Their concept of negative behaviors among nursing professionals was consolidated in the literature in 2017 with the publication of Nemeth et al. who proposed a unified conceptual and methodological framework. Thus, the definition proposed by these authors is adopted, according to which such behaviors are potentially harmful relational manifestations, with adverse impacts at both the individual and organizational levels [

8].

The International Labor Organization (ILO) identifies several similar phenomena that form part of the spectrum of negative behavior, including abuse of power, aggression, verbal harassment, sexual harassment, incivility, mobbing, ostracism, among others [

11]. Although it's difficult to pinpoint the beginning of the study of this subject, it is possible to identify Leyman's pioneering research dating back to the 1980s, in which he studied the personal and organizational effects of bullying and mobbing among health professionals in Sweden [

1].

Current international and national laws and regulations recognize that negative behavior is widespread in all sectors of the workplace [

11]. However, the literature shows that nurses are among the professionals most likely to be exposed to this phenomenon [

7,

12,

13].

Current scientific evidence describes the existence of 4 types of negative behavior expressed in the healthcare sector: type 1) criminal intent towards the organization; type 2) from clients, family members or carers towards the organization's multidisciplinary team; type 3) between the organization's multidisciplinary team and type 4) involving an aggressor who has a personal relationship with the victim, but not with the organization [

14]. This study will only focus on mapping the scientific evidence about negative behaviors that occur among nurses (type 3).

This type of negative behavior can manifest itself in two ways: it can occur between peers, i.e. between employees who have the same hierarchical level within the same organization, called horizontal or lateral behavior (example: general care nurse - general care nurse) [

9]; or between employees with different hierarchical levels, described as vertical. Within these, we can be faced with a perpetrator who is of a higher hierarchical level (example: nurse director - nurse manager) or who has a lower hierarchical level (example: general care nurse - nurse manager) [

9].

The literature points out that these behaviors can be due to various factors such as unfavorable working conditions [

15,

16], unequal exercise of power between professionals [

17,

18] and, additionally, the high emotional demands, work overload and need for constant decision-making under pressure inherent to the profession, these and other characteristics make nurses particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon [

19,

20,

21].

Negative behaviors have repercussions that go beyond the individual and have a direct impact on the safety and quality of the nursing care provided [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. They also contribute significantly to worsening emotional exhaustion, fatigue and sleep disturbances. They are also associated with somatic manifestations, namely musculoskeletal symptoms and cardiovascular alterations [

3,

22]. At the same time, these dynamics negatively influence levels of motivation and job satisfaction, increase turnover and compromise the quality of the Nursing Practice Environment [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Unfavorable Nursing Practice Environments are catalysts for the emergence and perpetuation of negative behaviors. The structural and organizational precariousness of these environments, combined with the critical shortage of nursing professionals, has been associated with reduced satisfaction and motivation among nurses, which compromises not only the quality of care provided, but also patient safety [

23,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30].

Nursing management plays a crucial role in the interrelationship between negative behaviors and Nursing Practice Environments. Effective leaders could shape organizational culture, promoting an environment of respect, collaboration and mutual support [

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, the lack of institutional mechanisms for reporting and mediating these phenomena, coupled with the fear of retaliation, perpetuates this problem and highlights the need for a structured and proactive approach on the part of nursing management [

31].

Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to map the available scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations, contributing to a deeper understanding of the underlying factors and the implications of these phenomena in the context of healthcare.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

As part of the methodological strategy outlined for this scoping review, several databases were consulted - namely Open Science Framework (OSF), INPLASY, PROSPERO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews - to identify previously registered protocols and other systematic reviews related to the subject under analysis. Although the preliminary search revealed the existence of studies that partially address this issue, no registered protocol or scoping review was identified that presented objectives, review questions or methodological criteria like those underpinning the present study. No scoping review was available that comprehensively and systematically synthesizes the existing literature on negative behaviors in the organizational context of health services. Despite the existence of research exploring specific dimensions of the phenomenon, there is still a significant gap in the integrated and holistic understanding of these dynamics within healthcare organizations.

This scoping review was carried out in accordance with the methodology for scoping reviews proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The presentation of the results was structured according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

32,

33].

2.2. Protocol and Registration

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

To draw up the review question, the mnemonic PCC (Population, Concept and Context) was used, defining the population (P) as nurses; the concept (C) as negative behaviors; the context (C) as health organizations. The combination of these mnemonics gave rise to the review question: “What is the scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations?”.

The following criteria were included for this study:

Participants: nurses working in public or private organizations, regardless of professional category, length of professional practice, age, gender, academic qualifications or professional relationship.

Concept: studies that address one or more negative behaviors or that discuss the concept of negative behavior. The concept of negative behavior that will serve as the basis for this review consists of a set of work attitudes towards other professionals that have the potential to negatively impact individuals and organizations [

8]. Within the set of negative behaviors presented above, this scoping review will focus on disorderly, inappropriate and unprofessional attitudes [

7], adverse social behaviors [

10] as well as abuse of power, aggression, verbal and sexual harassment, bullying, incivility, mobbing, ostracism and workplace violence [

8,

11].

Context: This scoping review included all studies reporting or discussing results from healthcare organizations, covering primary, hospital and long-term care, regardless of whether they were conducted in public or private institutions.

Types of Resources: Qualitative, quantitative, mixed-approach studies and systematic reviews that fit the defined criteria were considered for inclusion, as well as gray literature according to the methodology for scoping reviews by the JBI.

Given the diversity of terminology associated with this set of phenomena and the refinement of the concept of negative behavior in 2017 [

11], the time frame established is structured between 2017 and 2024. In this way, this review aims to ensure the inclusion of studies that use more consistent definitions of the phenomenon, to allow for a robust comparative analysis and the minimization of terminological biases.

This scoping review will include studies published in Portuguese, English or Spanish, with no restrictions on their geographical location.

2.4. Sources Information and Search Strategies

The search strategy was divided into three phases: initially, a search was carried out in the CINAHL and MEDLINE databases (via EBSCOhost) to identify relevant terms, as these are the two most relevant databases for literature reviews in Nursing [

34].

In turn, using the CINAH, MEDLINE, Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, SCOPUS and RCAAP databases, the selected terms were rigorously combined using Boolean operators and truncations, with equations adapted to each database (

Table 1); we then proceeded to select the articles based on an analysis of the titles, abstracts and full reading, carried out independently by two reviewers; and finally, the selected studies were grouped together and their bibliographic references analyzed to identify additional research, using a manual snowball search strategy [

35].

In cases where doubts remained after analyzing the abstracts, the articles were fully extracted and read in their entirety. After thorough reading, those that answered the research question initially formulated were selected to be part of this scoping review.

Two researchers carried out the selection process. As there were no disagreements between the two researchers, there was no need for a third party. In line with the methodological approach recommended by the JBI for scoping reviews, data extraction was carried out using a systematized results extraction table, built based on the review's objective and the respective research question [

36].

Once the bibliographic search was complete, all the references identified were organized and imported into the Mendeley bibliographic management software (version 1.19.8), after which any duplicates detected were eliminated. The remaining articles were imported into the Rayyan Enterprise and Rayyan Teams+ application (version 1.6.0), where they were analyzed by title and abstract according to the inclusion criteria [

37].

2.5. Selection Process

In the third stage of the review (study selection), all the articles were independently assessed by two reviewers, starting with the titles and abstracts, based on the previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The process of identifying, selecting and including the studies, as illustrated in the PRISMA-ScR diagram, was conducted in a systematic and transparent manner, in line with the exploratory nature of the scoping review, ensuring a comprehensive mapping of the relevant literature on the phenomenon under study [

35].

2.6. Data Collection Process

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, in accordance with JBI guidelines, and systematized in a structured table. Essential information was collected, including author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study objective, population and sample (where applicable), type of negative behavior analyzed, methodology adopted and main results relevant to the scope of the scoping review. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the reviewers and, when necessary, with the intervention of a third reviewer [

32,

38,

39].

To extract the data, an Excel file was developed based on the model proposed by the JBI [

39]. This form included key information from each source, such as authorship, results and findings relevant to the review question.

3. Results

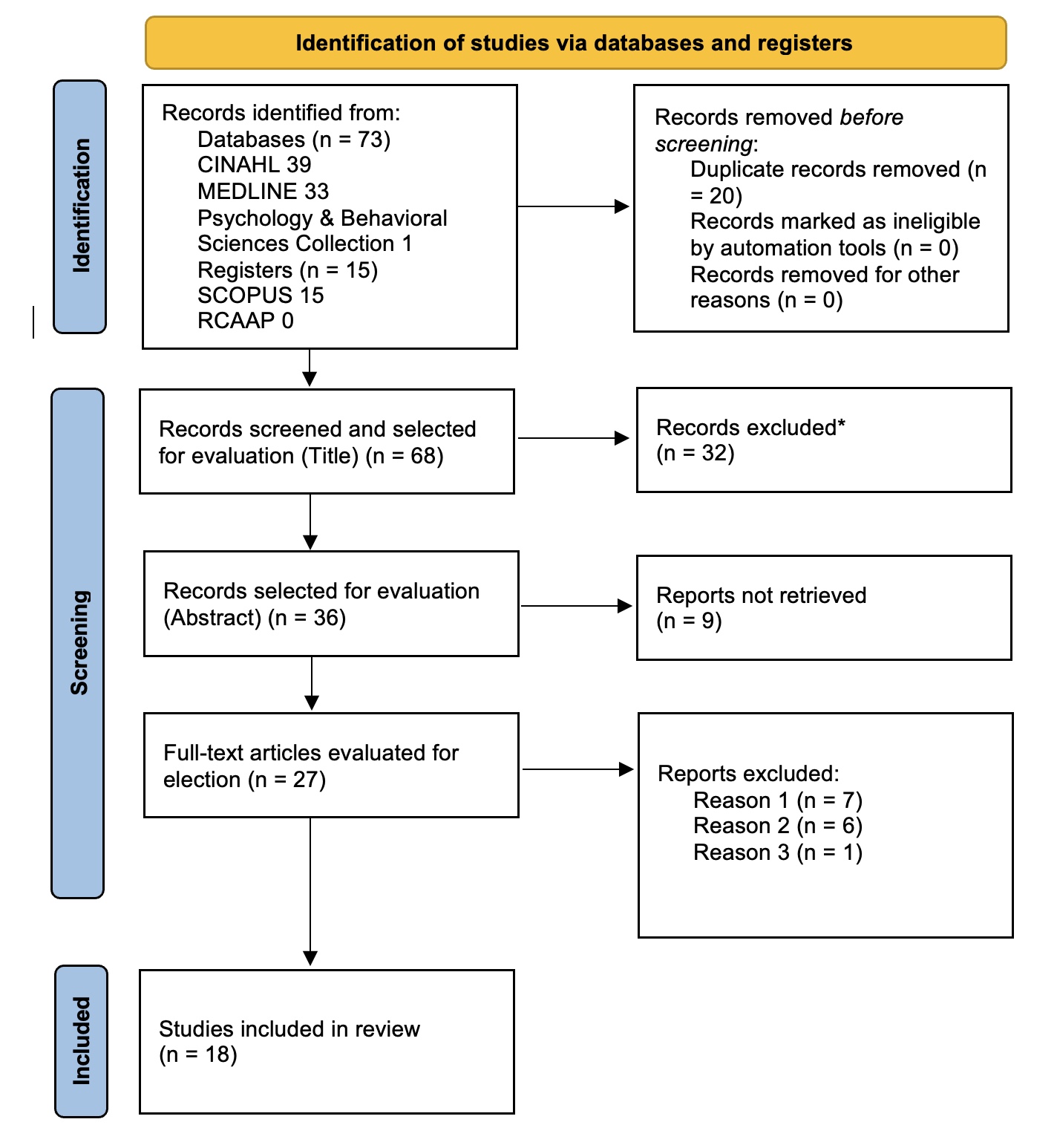

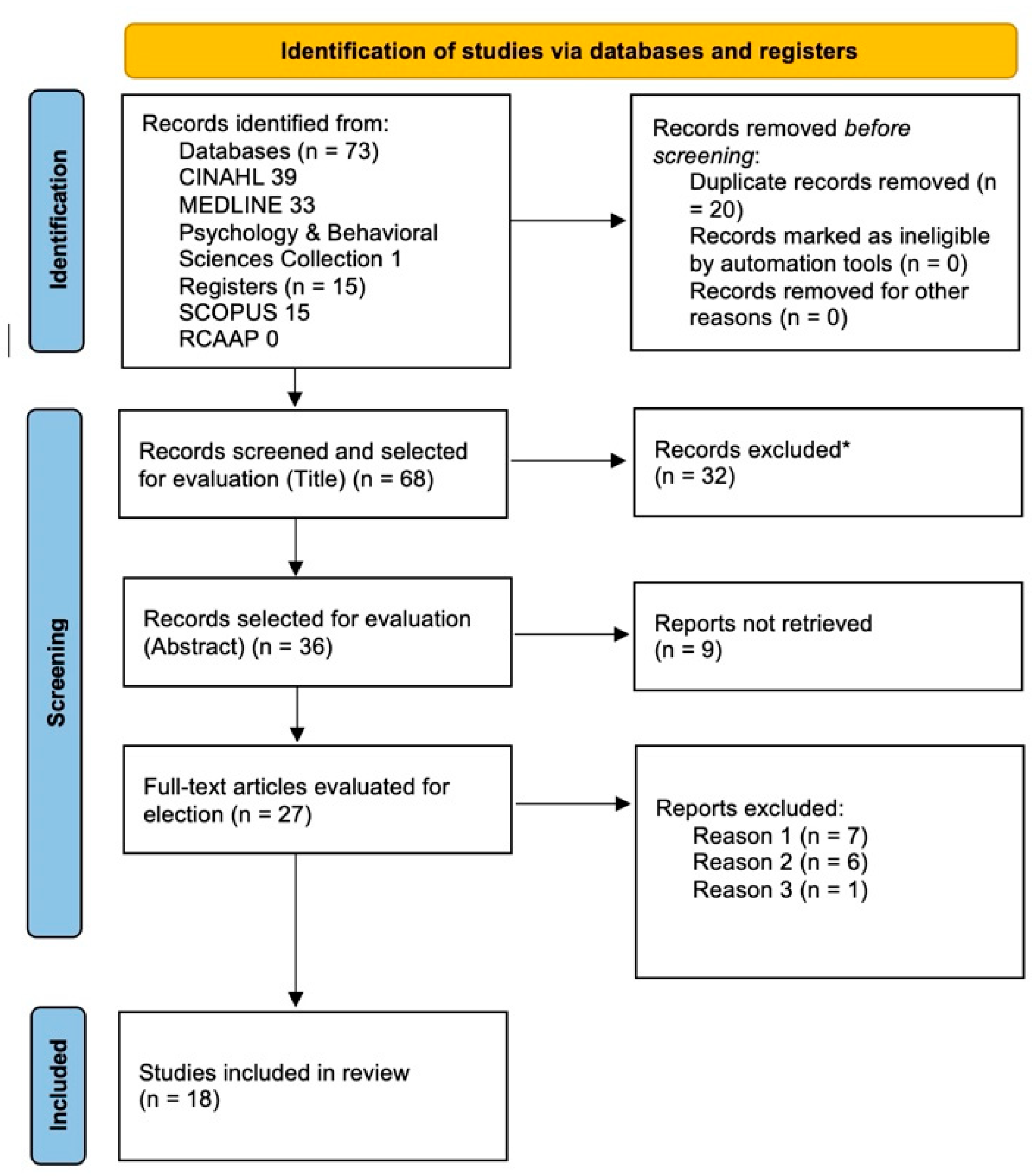

Figure 1 shows in detail the results obtained during the analysis stages.

The initial search resulted in the identification of 88 records, 20 of which were eliminated due to duplication.

In the first phase, 32 records were excluded after analyzing the titles, resulting in 36 articles for screening by abstract. In the second phase, 9 articles were eliminated based on their abstracts, leading to the selection of 27 articles for full-text evaluation. Of these, 14 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria, due to the inadequacy of the population studied (n=7), the concept addressed (n=6) or because they were instrument validation studies (n=1).

A review of the list of references of the included studies and expert recommendations resulted in 5 additional articles being added. Thus, a total of 18 studies were considered suitable for inclusion in the scoping review.

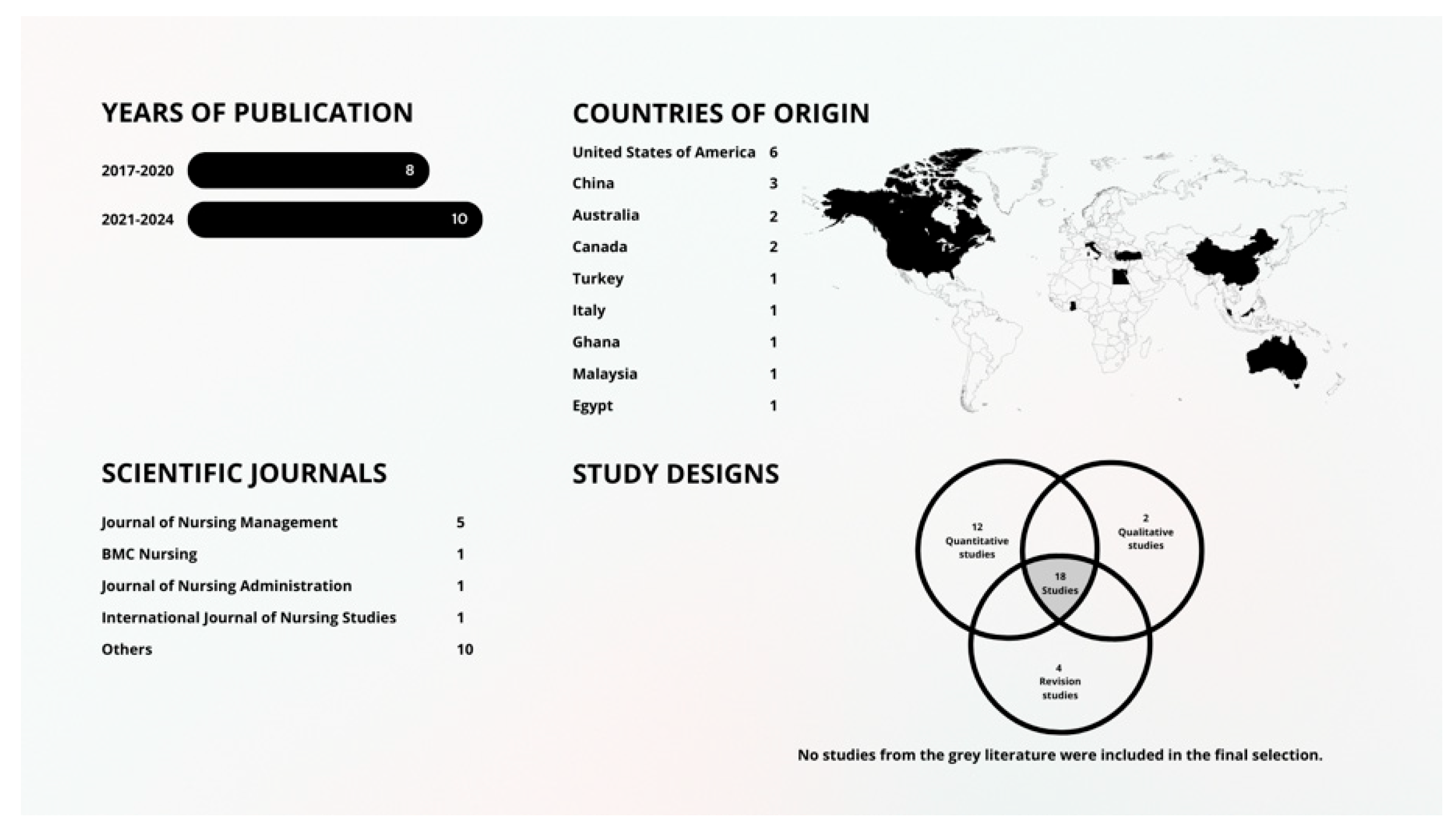

The 18 studies included were published between 2017 and 2024; 12 adopt quantitative approaches [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51], 2 are qualitative [

28,

52] and 4 are integrative reviews [

53,

54,

55,

56]. No studies from the grey literature were included in the final selection.

The samples range from 13 participants [

28] to large cohorts of more than 1,900 nurses [

50] with a total of 8,500 participants in this study. These come from the United States [

40,

41,

48,

53,

55,

56] Turkey [

41] Italy [

42], Canada [

49,

52], China [

44,

46,

51], Australia [

28,

54], Ghana [

45], Egypt [

50] and Malaysia [

47]. This methodological and geographical heterogeneity offers a comprehensive view of negative behavior. Table 2. shows the main characteristics of the selected studies.

Figure 2.

Main characteristics of the selected studies.

Figure 2.

Main characteristics of the selected studies.

Table 1.

Data Collection Instruments.

Table 1.

Data Collection Instruments.

| Instrument |

Negative Behavior |

Nº of Questions |

Nº of Dimensions |

| Negative Interactions Among Nurses Questionnaire [42] |

Lateral violence and Bullying

|

17 |

3 |

| Counterproductive work behavior scale [50] |

Counterproductive work behaviors |

23 |

5 |

| |

|

|

|

| Workplace ostracism scale [50] |

Ostracism |

10 |

1 |

Interpersonal conflict at work [46] |

Incivility

|

4 |

1 |

| Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) [43,45,48,49] |

Workplace bullying |

22 |

3 |

Deviant Workplace Behavior (DWD) [47]

Workplace Psychological Violence Behavior Assessment and Development Scale (WPVBADS) [41]

|

Deviant Workplace Behaviors

Colleague Violence |

19

41

|

2

3 |

| Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS) [40] |

Incivility |

7 |

1 |

| Workplace Psychologically Violent Behaviors Instrument [44] |

Bullying |

32 |

4 |

| Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) [51] |

Horizontal Violence |

19 |

2 |

The quantitative studies selected used various measuring instruments to collect data.

Table 1. shows the distribution of studies according to the instruments used to assess negative behavior.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the studies analyzed.

4. Discussion

As mentioned, the aim of this scoping review was to map the available scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations. To meet this objective, 18 studies were included that address the manifestation of these behaviors within nursing teams, the analysis of which generated the following domains: Negative Behaviors Spectrum; Prevalence of Negative Behaviors; Protective Factors and Risk of Negative Behaviors; Profiles of Victims and Aggressors; Impacts of Negative Behaviors; The Nurse Manager in Mitigating Negative Behaviors.

4.1. Negative Behaviors Spectrum

4.1.1. Negative Behaviors

There is a significant conceptual variation between authors regarding the manifestations of negative behaviors at work. On the one hand, Mansor et al. (2022) present a broad definition of deviant workplace behaviors, understanding them as a form of ethical conduct that goes against organizational objectives, manifesting itself as actions that can harm the organization, its members or the work environment in general. From this perspective, they range from minor infractions (lateness, absenteeism) to extremely serious behaviors (theft, harassment, insubordination) [

47].

For Mansor et al. (2022), periodicity (sporadic vs. systematic) and intensity (severity of acts) are key dimensions that not only differentiate the nature of behavioral deviance, but also signal the quality of the organizational climate: the more toxic the environment, the greater the frequency and systematization of these deviant behaviors [

47].

On the other hand, Hawkins et al. (2019, 2023) define negative workplace behaviors in the context of nursing, particularly among recently graduated professionals, as manifestations of bad manners, disrespect and hostile behaviors that occur in interactions marked by hierarchical power differences [

28,

54].

4.1.2. Bullying

Regarding bullying, there is unanimity on its core elements - intentionality, repetition and imbalance of power - but differences emerge in the time thresholds and the types of behavior described. Anusiewicz et al. (2019) define it as a pattern of negative, deliberate and inappropriate behaviors directed at a single individual, creating a hostile environment where repeated acts of hostility manifest themselves in verbal aggression, social exclusion or the spreading of rumors. From this perspective, the subjective perception of the victim and the difficulty in confronting often indirect and psychological behavior are emphasized [

56].

Trépanier et al. (2021) state that bullying corresponds to repeated and prolonged exposure to negative behavior perpetuated by colleagues, supervisors or managers, highlighting not only the frequency and duration, but also the involvement of witnesses in legitimizing the phenomenon, which shows a multi-participant power dynamic [

50]. Similarly, Olender (2017) highlights malicious intent and weekly occurrence, over months or years, differentiating bullying from mere occasional incivilities and emphasizing the hierarchical imbalance that intensifies the victim's vulnerability [

48].

Edmonson & Zelonka (2019) broaden the definition to repeated, unwanted and harmful behaviors aimed at humiliating and causing suffering, including physical or psychological threats, highlighting the persistent toxicity of the work environment [

56]. Dapilah & Druye (2024) propose a tripartite categorization - person-related, work-related and physical bullying - to capture the multidimensionality of the phenomenon and the role of perpetrator groups [

45].

Lu et al. (2022) reinforce the criterion of intentionality and systematization, excluding isolated episodes or those of low severity [

43], while Sauer & McCoy (2017) impose a minimum threshold of six months of exposure to disruptive behaviours, classifying them as verbal and non-verbal and highlighting the relevance of the number of people involved [

45]. Finally, Bambi et al. (2019), based on Einarsen et al. (2011), stipulate that the behavior must occur at least once a week for a minimum period of six months to be considered bullying, reinforcing its persistent nature and unequal power dynamics [

42,

57].

4.1.3. Horizontal, Vertical or Peer Violence

We found three strongly related constructs - horizontal, lateral and peer violence - which emerge with definitions that, although they share common cores, reveal relevant conceptual and operational nuances.

For Peng et al. (2021), horizontal violence is defined as interpersonal conflict between peers in the nursing profession, characterized by negative behaviour that manifests itself openly (destructive criticism, verbal harassment) or covertly (social exclusion), with the aim of humiliating or denigrating the colleague. The research also shows the persistence of the phenomenon: 59.1% of nurses reported having experienced horizontal violence at least once in the six months prior to the survey, suggesting a chronic problem in the hospital environment [

51].

In line with this relational perspective, Krut et al. (2021) describe horizontal violence as aggressive, hostile or disrespectful behavior between colleagues - particularly harmful to new graduates - expressed through hostile verbal communication, psychological harassment or exclusion, which occurs frequently in everyday interactions. The main difference with Peng et al. lies in Krut et al.'s emphasis on the vulnerability of new professionals and the intensity of their daily interactions, without necessarily specifying a minimum time threshold [

51,

52].

For their part, Bambi et al. (2019) use the term lateral violence to denote repeated negative interactions between coworkers, pointing out that verbal and emotional abuse, even when isolated, accumulates to create a hostile and inappropriate environment. This definition reinforces the systematic nature of the phenomenon and its potential to damage both individual well-being and professional relationships, aligning with the classic criteria of Einarsen et al. (2011) regarding the pattern and frequency of aggression [

42,

57].

Ayakdaş and Arslantaş (2018) prefer the concept of peer violence, which encompasses both psychological violence and other forms of hostility in teamwork. These authors document that around 47% of nurses have experienced this type of violence, highlighting its impact on the psychological integrity of professionals and the quality of care provided [

41].

Comparatively, although they all recognize the presence of hostile behavior among peers, Peng et al. (2021) and Krut et al. (2021) differ in their emphasis on overt vs. covert typology and frequency in daily routines, respectively [

51,

52]; Bambi et al. (2019) highlight the cumulative and systematic nature required to classify lateral violence [

42]; and Ayakdaş and Arslantaş (2018) broaden the focus to the consequences on mental health and clinical performance. These conceptual and operational variations - especially in terms of frequency thresholds, the nature of the acts (overt vs. covert) and the impact on specific populations (recent graduates, multidisciplinary teams) - reinforce the urgency of establishing clear operational definitions and consensual measurement tools to enable reliable comparisons and guide effective preventive interventions [

41].

4.1.4. Incivility

The phenomenon of incivility emerges as a multifaceted construct, whose definition varies depending on the degree of hostility, intentional ambiguity and pattern of occurrence. According to Xiaolong et al. (2021), incivility in the workplace translates into disrespectful behavior that ranges from a lack of courtesy in interpersonal interactions to disdain in communications and indifference to colleagues' needs, manifesting itself in attitudes such as ignoring others or omitting expressions of basic politeness (“please”, “thank you”) and in verbally hostile interactions [

46].

Farrell (2022) broadens the concept by considering incivility - often equated with bullying - as a set of negative, intentional and repeated acts, perceived as emotionally disturbing, which are subdivided into overt (verbal insults, explicit intimidation) and covert (rumors, ostracism). From this perspective, the variability in periodicity (sporadic vs. frequent) and intensity (from mild discomfort to severe emotional hostility) shapes the severity of the professionals' experience [

53].

Smith et al. (2018) define incivility as the occurrence of low-intensity behaviors that exhibit an ambiguous intention to cause harm, emphasizing its subtle nature but significant impact on the interpersonal dynamics of high-pressure environments such as hospitals [

40].

4.1.5. Ostracism

Ostracism as the perception of social exclusion in the workplace, manifested by subtle behaviors - avoiding eye contact, withdrawal from common spaces or even forced relocation to peripheral areas - which create a sense of marginalization among nursing professionals. At the same time, the same authors propose a classification of negative behaviors into two dimensions: those directed at the organization and those directed at individuals [

50].

Based on this taxonomy, it was observed that 86.45 % of nurses gave an unfavorable assessment to ostracism practices, with acts directed at the organization eliciting a slightly more negative reaction (39.69 %) than behaviors directed specifically at colleagues. Finally, 82.11 % of respondents expressed a negative opinion of ostracism itself, reinforcing the pernicious nature of this phenomenon for team cohesion and the organizational climate [

50].

This shows not only the insidious nature of ostracism, but also its high disapproval rate among professionals, underlining the urgency of intervention strategies capable of re-establishing bonds of inclusion and support in the hospital context [

50].

4.1.6. Conceptual Challenges

The studies analyzed identified different forms of negative behaviors, including incivility [

39,

46,

53] bullying [

43,

44,

45,

46,

49,

55,

56] and ostracism [

50]. In addition, some research uses broader terminology, such as negative workplace behaviors [

28,

55] or deviant workplace behaviors [

47], while others differentiate the phenomena, using terminology such as lateral violence [

41,

51] and horizontal violence [

51,

52] or peer violence [

41] to describe similar phenomena.

The diversity of terminology represents a significant challenge, as it is seen as a factor that makes it difficult to compare different variables between studies. This terminological divergence could compromise the formulation of effective intervention strategies, since the lack of conceptual standardization could infer the intrinsic complexity of the underlying phenomenon, constituting a methodological obstacle to its assessment and mitigation. As ILO (2020) and Hawkins et al. (2019) point out, it is essential to move towards greater standardization of the terms used in scientific literature, allowing for more precise analyses and the development of appropriate preventive and mitigation measures [

11,

55].

There is significant heterogeneity in the prevalence of negative behaviors among nursing professionals. This marked heterogeneity reflects not only contextual and methodological differences between studies, but also the complexity of the phenomenon itself.

The variability in results may be associated with contextual and methodological factors, and the quality of leadership, institutional support and organizational culture play a crucial role in modulating these phenomena. In addition, work overload, the pressures inherent in clinical practice and individual factors, such as stress management capacity and resilience, influence the incidence and perception of these negative behaviors [

3,

42,

49].

4.2. Prevalence of Negative Behaviors

Regarding prevalence, Sauer & McCoy (2017) and Anusiewicz et al. (2019) identified rates between 27% and 40% [

43,

56], while Bambi et al. (2019) report that 35.8% of nurses experienced negative interactions, 42.3% of which were weekly bullying over six months [

41]. Lu et al. (2022) report 30.6% prevalence [

43], Trépanier et al. (2021) point to almost 40% exposure [

49], and Olender (2017) finds that 26.3% of nurses face daily episodes of bullying and 35.9% weekly episodes [

48]. These figures illustrate the magnitude of the problem and, at the same time, reveal slight methodological variations, namely the different types of data collection instrument, as well as contextual ones that should be carefully considered when interpreting the results comparatively.

In short, the prevalence of negative behaviors among nurses varies widely, ranging from 27% to 64.4%, depending on the type of behavior analyzed and the context investigated. This range reinforces the need for multifaceted approaches that consider both individual and organizational factors, with a view to promoting favorable and safe Nursing Practice Environments for nursing professionals and, consequently, the quality of care provided.

4.3. Protective Factors and Risk of Negative Behaviors

4.3.1. Protective Factors

The analysis of the studies shows a complex network of factors that influence the manifestation of negative behaviors in nursing practice. These factors include both organizational elements, such as team structure and management, and individual characteristics of professionals, including personality traits and resilience. The following is a summary of the main findings, contributing to the mapping of scientific knowledge in this area.

In relation to organizational factors, a positive work environment, characterized by supportive leadership and effective communication, plays a key role in reducing the incidence of incivility and bullying. Smith et al. (2018) found that a Nursing Practice Environment that promotes nurse autonomy is inversely associated with the occurrence of incivility [

40].

Favorable Nursing Practice Environments, based on effective leadership practices and adequate institutional support, favor professional satisfaction and reduce the prevalence and incidence of dysfunctional interpersonal interactions [

23,

24,

25,

26]. On the other hand, deteriorated environments have been identified as catalysts for insecurity in the care provided and increased turnover among professionals [

29,

30].

Faced with exposure to negative behaviors in the workplace, nurses resort to various coping strategies, which can be grouped into positive and negative approaches, depending on their effectiveness and impact on mental health and professional performance.

Positive coping strategies include active problem-solving and measures to promote well-being. Ayakdaş and Arslantaş (2017) found that many professionals choose to deal with the situation directly, using dialogue with colleagues as a way of clarifying conflicts and re-establishing interpersonal relationships. At the same time, they reorganize their tasks to avoid criticism and prevent new situations of tension. This work restructuring is an attempt to regain control over the Nursing Practice Environment, mitigating the impact of disruptive behavior [

41].

Another relevant aspect of adaptive coping strategies involves proactive behaviors. Krut et al. (2021) identified that regular physical exercise, intentional distancing from the aggressor or the harmful environment, as well as establishing clear boundaries between the personal and professional domains, act as measures that favor emotional balance and resilience. Such actions demonstrate a proactive effort to reduce exposure to stress factors and promote a more effective psycho-physiological recovery [

52].

Seeking social support is also one of the most valuable coping strategies. Hawkins et al. (2023) stress the importance of sharing experiences with family, friends and mentors, as well as resorting to formal professional assistance programs. These mechanisms not only contribute to emotional validation and a reduced sense of isolation, but also promote a more constructive reinterpretation of adverse experiences [

28].

On the other hand, some coping strategies based on avoidance can, in the long term, perpetuate the problem by preventing the effective resolution of conflicts and aggravating psychological distress. For example, persistent avoidance and excessive separation between the personal and professional domains - when used as an escape mechanism - can reduce the professional's involvement with the team, compromising group cohesion [

52].

It should also be noted that, although individual coping strategies are crucial for dealing with negative behaviors, their effectiveness depends heavily on organizational support. Olender (2017) and Bambi et al. (2019) emphasize that sound institutional policies - which promote safe and inclusive Nursing Practice Environments - enhance the positive effects of coping strategies and allow for a more robust and systematic response to the occurrence of abusive behavior [

42,

48].

4.3.2. Risk Factors

On the other hand, high workloads, a lack of resources, fatigue, a lack of familiarity between professionals and ineffective communication were identified as risk factors. The combination of these elements with conflicting personalities can create a volatile working environment, prone to abusive interactions. Thus, measures that reduce overwork, foster team cohesion and promote effective communication have the potential to minimize or eliminate episodes of bullying [

53].

Trépanier et al. (2021) showed that workload positively predicts exposure to bullying behavior over time, but this association is attenuated when social support and professional recognition are high. In contexts where these elements are robust, workload is no longer related to the occurrence of bullying and may even be inversely related to this phenomenon. This finding reinforces the importance of well-structured organizational environments in preventing abusive behavior [

49].

Bambi et al. (2019) identified, through a logistic regression analysis, significant predictors for negative interactions and peer bullying. Risk factors include working day shifts, exposure to negative interactions directed at other nurses and the practice of negative behaviors by the professional themselves. Regarding bullying, the main predictors identified were greater perceived intensity of negative interactions, currently being a victim of these interactions and the manifestation of psychophysical symptoms and disorders. On the other hand, working in a hospital environment proved to be a protective factor, reducing the likelihood of these behaviors occurring [

42].

This perspective is further supported by a study which shows that a shortage of resources, ineffective leadership and poor management contribute significantly to the occurrence of negative behaviors. Specifically, poor planning and resource allocation was found to hinder not only the ability to respond to operational demands, but also the creation of environments prone to conflict and abusive practices [

56].

The geographical context can also influence the occurrence of negative behaviors. Hawkins et al. (2023) identified that rural or remote environments can be risk factors for incivility and bullying, since the lower turnover of the workforce in these places favors the development of lasting interpersonal relationships. These dynamics can reinforce counterproductive behaviour and promote the exclusion of new professionals, increasing vulnerability to harassment and marginalization in the workplace [

28].

In addition, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the perpetuation of these phenomena, exacerbating the challenges that already exist in the organizational culture [

28].

As for the individual characteristics of professionals, Mansor et al. (2022) identified that personality traits such as trait anger can act as triggers for negative behaviors, suggesting that certain individual predispositions can exacerbate these types of interactions. However, no evidence was found that negative affectivity has a significant influence on deviant behavior, which indicates that not all negative emotions automatically result in harmful attitudes [

47].

Sauer and McCoy (2017) analyzed the role of resilience in mediating the negative impacts of bullying on nurses' health, but concluded that resilience, in this context, was not an effective protective factor. This finding reinforces that, although resilience is desirable, it is not sufficient to mitigate the adverse effects of bullying [

43].

As evidenced by Elliethey et al. (2024), the results indicated that work ethic exerts a significant negative influence on each negative behavior. Regression analysis revealed that work ethic can negatively predict around 15% of the variance in each of the adverse behaviors. This finding underlines the importance of promoting high ethical standards in the workplace to reduce the incidence of negative behavior and foster a more harmonious and productive work environment [

50].

In short, the interaction between protective factors - such as a positive and ethical work environment that promotes autonomy, recognition and social support - and risk factors - such as work overload, lack of resources, inadequate leadership and dysfunctional organizational dynamics - reveals the complexity of the mechanisms underlying negative behaviors in nursing (

Table 3).

This evidence reinforces the need for integrated interventions that not only improve working conditions, but also strengthen ethical values and individual skills, to reduce the incidence of these behaviors and their impact on the professional context.

4.4. Profiles of Victims and Aggressors

4.4.1. Characteristics of the Victims

Victims of negative behavior among nurses are often professionals at the start of their careers and those in lower hierarchical positions. Studies indicate that recent graduates are more vulnerable to this phenomenon, leading to feelings of isolation, low self-esteem and emotional fragility [

28]. This fragility is exacerbated by the organizational culture present in many teams, where there is an “us versus them” attitude, in which more experienced professionals adopt a territorial stance and new nurses feel the need to prove that they are worthy of inclusion [

28,

54].

In addition, professionals with less hierarchical prestige, often due to the absence of consolidated support networks, are more exposed to negative behavior, namely harassment, mobbing and incivility. This dynamic perpetuates a vicious cycle of exclusion and vulnerability, in which the absence of support increases the likelihood of exposure to negative behavior, which in turn further compromises access to support networks, exacerbating isolation and susceptibility to new situations of abuse [

54].

Although the literature points to a higher risk for nurses at the start of their careers, there is also evidence that more experienced professionals can be the target of negative interactions. Nurses with a higher level of university certification experience more negative behavior. Similarly, professionals with a master’s degree in nursing report greater victimization. In addition, nurses with a career between 11 and 20 years seem to be more exposed to these dynamics than other groups [

42].

Finally, the literature highlights that gender differences can play a relevant role in exposure to these negative experiences. Although most studies include predominantly female professionals, some authors suggest that female nurses are disproportionately affected and are more often the target of abusive behavior in the workplace [

44,

47,

55].

4.4.2. Characteristics of the Aggressors

The perpetuators of negative behaviors among nurses tend to occupy positions of authority - formal or informal - and resort to aggressive behaviors to reaffirm their status and exert control in the Nursing Practice Environment. Bambi et al. (2019) showed that nurses in management and coordination positions (around 12.9% of participants) and nursing managers (1.1%) can take on an ambiguous role, acting as both aggressors and victims, depending on the context of the interactions [

42].

The available evidence shows that, in the organizational context, the roles of victim and aggressor are not mutually exclusive. Bambi et al. (2019) identified that 32.4% of the professionals surveyed reported playing both roles - victim and perpetrator of negative behavior - with this dual condition being more prevalent than the isolated role of victim. This data highlights the complexity of relational dynamics in the workplace, where individuals can alternate between positions of vulnerability and power [

42].

This overlapping of roles suggests the existence of a relational cycle of violence, in which professionals who experience abusive behavior may, in certain contexts, reproduce such behavior as a defense mechanism or hierarchical affirmation strategy. Power dynamics thus play a central role in understanding this phenomenon, indicating that the same individuals can be, at different times or simultaneously, targets and perpetuators of disruptive behavior [

47,

55].

4.5. Impacts of Negative Behaviors

Negative behaviors in the nursing workplace have significant impacts on several levels, affecting the individuals directly involved, organizations and the quality of care provided. The consequences manifest themselves above all on a physical and psychological level for the victims, contributing to burnout, the intention to leave the job and the deterioration of care. These impacts are analyzed below, including the effect of polychronicity, defined as the ability to manage multiple tasks simultaneously [

46].

4.5.1. Impacts for Nurses

Negative behaviors profoundly affect nurses' well-being, causing physical and psychological harm. Studies, such as Lu et al. (2022), have shown a direct relationship between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation, associated with a higher risk of suicide attempts [

44]. Sauer and McCoy (2017) pointed out that nurses who are victims of bullying face high levels of stress and depressive symptoms, which directly affects their quality of life and the safety of the care they provide [

43].

Hawkins et al. (2019) indicated that newly graduated nurses exposed to negative interactions experience frequent emotional disturbances, anxiety and depression, leading to decreased job satisfaction, burnout and the intention to leave the profession [

53]. Bambi et al. (2019) revealed that 21.9% of nurses who were victims of negative behavior expressed an intention to leave nursing, and 20% requested a transfer to another unit or service. In addition, 59% of nurses reported that negative behaviors had a detrimental impact on their psychophysical health, and 8.4% reported making clinical errors as a result of abusive interactions [

42].

Physically, negative behaviors can induce psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, sleep disturbances and concentration difficulties, thus increasing the risk of clinical errors and compromising nurses' ability to respond, which can put patient safety at risk [

52,

53].

Xiaolong et al. (2021) found that polychronic nurses, i.e. those who adopt multitasking behaviors, tend to demonstrate high engagement and performance in the hospital environment. However, exposure to uncivil behavior on the part of colleagues and supervisors weakens the positive relationship between polychronicity and affective well-being at work, exacerbating the negative effects of a hostile environment [

46].

In contrast, Ayakdaş and Arslantaş (2018) also pointed out that 84.1% of nurses who were victims of peer violence increased their work effort in response to negative behaviors, which in turn intensified physical and mental exhaustion, perpetuating the burnout cycle [

41].

4.5.2. Impact on Patients

Adverse effects on nurses have a direct impact on the quality of care provided to the person being cared for. Anusiewicz et al. (2019) observed that exposure to negative behaviors is associated with an increase in medication administration errors and a greater number of falls. Extreme fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and burnout reduce clinical effectiveness, compromising safety and well-being [

56].

Sauer and McCoy (2017) also point out that nurses who are victims of bullying see their ability to provide safe and effective care compromised, which can lead to negative outcomes for the person being cared for. A poor nursing practice environment not only affects communication between professionals, but also compromises the ability to respond to critical situations, increasing the risk of adverse events [

43].

4.5.3. Impacts on the Organization

The existence of negative behaviors among nursing professionals also has consequences at the organizational level. Dapilah and Druye (2024) observed that exposure to bullying is strongly associated with an increase in the intention to quit the profession and the development of depression among nurses [

45]. In addition, Anusiewicz et al. (2019) point out that negative behaviors lead to increased absenteeism, increased intention to turnover and, consequently, increased turnover of professionals. The authors point out that these phenomena lead to a reduction in job satisfaction associated with a deterioration in the physical and psychological well-being of professionals [

56].

On a financial level, the costs associated with high turnover, absenteeism and the need to train new professionals represent a substantial economic burden for healthcare organizations. Edmonson and Zelonka (2019) point out that an organizational culture that perpetuates behaviors such as bullying contributes to a poor nursing practice environment, substantially increasing patients' susceptibility to risk and negatively affecting patient satisfaction rates. These consequences, coupled with increased nurse turnover, can cost an organization between 4 and 7 million dollars on average [

56].

Therefore, the implementation of strategies that promote favorable nursing practice environments, better resource management and psychosocial support is essential to mitigate these impacts and guarantee the quality of care provided.

4.6. The Nurse Manager in Mitigating Negative Behaviors

The role of the nurse manager is crucial to mitigate negative behaviors among professionals, contributing to the construction of a favorable, collaborative and safe nursing environment. The selected studies show that the leadership styles adopted significantly influence the incidence of unwanted behaviors such as bullying, incivility and lateral violence, affecting both the well-being of nurses and the quality of care provided.

Nurse managers who adopt a leadership style characterized by empathy, open communication and continuous support promote environments that minimize such behaviors. Smith et al. (2018) showed that work contexts that value support and autonomy have considerably lower levels of incivility [

41]. Similarly, Olender (2017) points out that the demonstration of care and attention by managers acts as a determining factor in reducing nurses' exposure to negative behaviors [

48].

On the other hand, authoritarian leadership styles tend to aggravate tensions and consolidate an organizational culture marked by disrespect and conflict. Farrell (2022) shows that the imposition of authoritarian management practices intensifies hierarchical disparities and encourages harmful behavior. In addition, Farrell (2022) also proposes specific strategies to combat incivility, which include early intervention, the elimination of triggers, continuous education for nurses and leaders, as well as the use of strategies such as cognitive rehearsal - both in the form of scenario review and role playing - in addition to emphasizing prevention and leadership accountability [

53].

Additionally, Bambi et al. (2019) suggest that nurse managers can play a decisive role in preventing negative interactions between colleagues. Among the recommended strategies are the implementation of continuing education programs to raise awareness of the problem, the establishment of anonymous reporting systems, the promotion of the presence of occupational psychologists and the prevention of confrontations through frequent changes in team composition during shifts [

42].

The importance of leadership is further emphasized by Hawkins et al. (2019), who state that leadership style and the influence of managers are key determinants in creating respectful and positive organizational cultures, recommending that multi-level organizational interventions be implemented and tested to directly address the problem [

54].

In this sense, Edmonson and Zelonka (2019) propose a series of strategies to combat bullying in nursing: acknowledging the existence of the problem; eliminating situational factors that can exacerbate bullying, such as work overload, stress and fatigue; initiating change starting with leadership, training managers in clear communication and collaboration skills; adopting a zero-tolerance policy for those who persist in abusive behavior; fostering an environment in which nurses feel comfortable reporting episodes of bullying or even addressing them directly; and finally, encouraging mutual accountability among colleagues, turning bystanders into agents of change [

55].

However, additional challenges have been reported by Hawkins et al. (2023), who highlight that performance management processes aimed at correcting negative behaviors are often ignored by senior management, mainly due to staff shortages and the prioritization of other organizational objectives. Nurse managers of services/units reported that the existence of other organizational priorities and the shortage of nurses, especially in more remote regional areas, often lead to the acceptance of negative behaviors as the norm [

28].

Nurse managers therefore play a dual and essential role: on the one hand, they must act preventively, creating an organizational environment that minimizes hierarchical disparities and promotes positive interpersonal interactions; on the other, they must intervene effectively in conflict resolution, using structured strategies and ongoing support.

Consolidating such practices requires leadership training programs that emphasize transformational approaches, including the implementation of Farrell's (2022) strategies for combating incivility - such as early intervention, eliminating triggers, education and cognitive rehearsals - contributing to building more respectful, collaborative environments and, consequently, improving patient care [

40,

42,

45,

47,

48,

50,

53,

54,

55].

5. Limitations and Future Prospects

The limitations of this study include the selection of databases - namely CINAH, MEDLINE, Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, SCOPUS and RCAAP - and the inclusion of only studies published in Portuguese, English and Spanish, which restricted the scope of the contributions and may have omitted important evidence from other sources or languages.

One of the main limitations of this scoping review lies in the conceptual heterogeneity that characterizes the scientific community regarding the terminology and classification of negative behaviours. This highlights the need to standardize the terms used, and this scoping review is a pioneer in this area.

The selected studies present a variety of data collection instruments. Among the most prominent are the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) [

43,

45,

48,

49], widely adopted to measure bullying; the Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS) [

40], applied to assess incivility; as well as instruments developed ad hoc, often based on previous validations or semi-structured interviews. Although this variety of tools reflects the complex and multidimensional nature of negative behaviors in the nursing workplace, it also represents an obstacle to comparability between studies. The lack of standardization in the assessment criteria, as well as variations in the domains covered by each instrument, compromise the uniformity of the data collected and make cross-sectional analysis between different geographical, cultural and organizational contexts difficult.

Given these limitations, future research should deepen the understanding and mitigation of negative behaviors in nursing practice. Longitudinal studies evaluating the impact of interventions based on transformational leadership are recommended to clarify the contribution of continuous leadership training to reducing these behaviors. Furthermore, it is suggested that quasi-experimental and experimental intervention studies be carried out that implement educational strategies, such as the application of training programs that include coping and effective communication techniques, to evaluate their effectiveness in mitigating negative behaviors.

Research should also explore the practical application of interventions, such as the implementation of safe reporting systems, with special attention to the most vulnerable professionals, such as recent graduates.

The use of mixed methods will allow for a holistic analysis of organizational and individual factors, contributing to the formulation of policies and programs that promote safer, more ethical and resilient nursing practice environments. In short, future research should operationalize and evaluate the impact of practical interventions aimed at continuously improving the quality and safety of healthcare.

6. Conclusão

This scoping review made it possible to map and synthesize the scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations, revealing the complexity and multifaceted nature of this phenomenon. The inclusion of 18 studies published between 2017 and 2024 showed a wide methodological and geographical variability, offering a global panorama, although this diversity imposes limitations on the direct comparability of results.

The analysis of the results revealed six key dimensions that contribute to the understanding of negative behaviors in the studied context: the Negative Behaviors Spectrum, the Prevalence of Negative Behaviors, the Protective Factors and Risk of Negative Behaviors, the Profiles of Victims and Aggressors, the Impacts of Negative Behaviors, and finally, the role of the Nurse Manager in Mitigating Negative Behaviors.

It was found that phenomena such as bullying, incivility and lateral violence are not isolated episodes, but structural reflections of dysfunctional organizational climates. The prevalence rates observed - between 27% and 64.4%, depending on the type of behavior and the context analyzed - illustrate the magnitude of the problem and the urgent need for systemic responses. These behaviors have been shown to be particularly harmful to professionals, with physical (fatigue, sleep disturbances), psychological (anxiety, burnout, suicidal ideation) and organizational consequences, with direct impacts on the safety and quality of care provided [

40,

43].

One of the central contributions of this review was the identification of a notable terminological and conceptual heterogeneity - visible in the different ways of naming and operationalizing negative behaviors - which makes comparison between studies difficult and highlights the need for rigorous standardization of the concepts and instruments used.

The risk factors identified - such as work overload, lack of resources and poor leadership - amplify negative dynamics, while positive nursing practice environments - based on empathetic leadership, open communication, professional autonomy and institutional support - prove to be crucial protective factors, significantly mitigating the occurrence of abusive behaviors such as bullying and incivility [

28,

42,

53]. Although individual traits, such as trait anger, can predispose professionals to certain behaviours, the ultimate responsibility lies with organizations, as structures that shape the relational climate and standards of conduct [

47].

In this context, nurse managers play a central and unavoidable role. Their strategic action - through the implementation of zero-tolerance policies, the creation of safe reporting channels, continuous leadership training and the promotion of positive coping strategies - has proven effective in preventing and responding to negative behavior [

44,

49,

55]. The adoption of transformational leadership styles, centered on empathy, continuous support and professional recognition, contributes significantly to the creation of more collaborative, safe and sustainable practice environments [

48,

57].

This synthesis of evidence provides nursing managers and policymakers with a solid basis for developing sustained interventions that promote positive and resilient work environments. In short, this scoping review not only systematizes the state of the art, but also outlines clear directions for the advancement of nursing research and practice, reaffirming the structuring role of the work environment and leadership in promoting occupational health, safety of care and quality of care to promote ethical, resilient practice environments focused on the safety of professionals and patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S., R.B., P.C., P.L. and E.N.; methodology, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N.; software, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N; formal analysis, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N; investigation, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N; resources, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N; data curation, N.S., R.B., P.L. and E.N; writing—original draft preparation, N.S., R.B., P.C., P.L. and E.N.; writing—review and editing, N.S., R.B., P.C., P.L. and E.N.; visualization, N.S., R.B., P.C., P.L. and E.N.; supervision, N.S., R.B., P.C., P.L. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper forms part of the invitation extended by the editors of the special issue. This study didn’t receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- João, A.L. Mobbing/agressão psicológica na profissão de Enfermagem; Lusociência: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013; ISBN: 9789728930882.

- Chiavenato, I. Recursos humanos: o capital humano das organizações, 11th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brasil, 2020; ISBN: 9788597023671.

- Huston, C.J. Leadership roles and management functions in nursing: theory and application, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, Países Baixos, 2024; ISBN: 9781975193089.

- Rahim, M.A. Managing conflict in organizations, 5th ed; Routledge: Nova York, Estados Unidos da América, 2023; ISBN: 9781032258201.

- Maben, J.; Conolly, A.; Abrams, R.; Rowland, E.; Harris, R.; Kelly, D.; Kent, B.; Couper, K.; the Impact of Covid On Nurses Survey Research Group. ‘You can't walk through water without getting wet’: UK nurses’ distress and psychological health needs during the Covid-19 pandemic – a longitudinal interview study. Int J Nurs Stud 2022,131,104242. [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S. Workplace bullying in nursing: a problem that can't be ignored. Medsurg Nurs. 2009,18(5),273–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19927962/.

- Aunger, J.A.; Maben, J.; Abrams, R.; Wright, J.M.; Mannion, R.; Pearson, M.; Jones, A.; Westbrook, J.I. Drivers of unprofessional behavior between staff in acute care hospitals: a realist review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023, 23(1),1–22. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, L.S.; Stanley, K.M.; Martin, M.M.; Mueller, M.; Layne, D.; Wallston, K.A. Lateral violence in nursing survey: instrument development and validation. Healthcare 2017, 5(3),1–12. [CrossRef]

- Layne, D.M.; Nemeth, L.S.; Mueller, M.; Wallston, K.A. The Negative Behaviours in Healthcare Survey: instrument development and validation. J Nurs Meas 2019, 27(2),221–33, . [CrossRef]

- Eurofund. Violence and harassment in European workplaces: causes, impacts and policies; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Irlanda, 2015.

- International Labour Organization. Safe and healthy working environments free from violence and harassment; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Suíça, 2020.

- International Labour Organization; International Council of Nurses; World Health Organization; Public Services International. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector: the training manual; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Suíça 2005. https://www.world-psi.org/sites/default/files/documents/research/training-manual.pdf.

- Luongo, J.; Freitas, G.F.; Fernandes, M.F.P. Caracterização do assédio moral nas relações de trabalho: uma revisão da literatura. Cult Cuid. 2011,15(30),71–8, . [CrossRef]

- American Nurses Association. Workplace violence. Disponível online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/advocacy/state/workplace-violence2/. Acedido em: 20 dezembro 2024.

- Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress. 2009,23(1),24-44. [CrossRef]

- Salin, D.; Hoel, H. Organizational risk factors of workplace bullying. In: Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Theory, research, and practice, 3rd ed; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., eds., Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, Estados Unidos da América, 2020; pp. 305-329, ISBN: 9780429462528.

- Arnetz, J.E.; Sudan, S.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Jodoin, C.; Chang, C.H.; Arnetz, B.B. Organizational determinants of bullying and work disengagement among hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs 2019,75(6),1229-1238. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. Negative workplace behavior and coping strategies among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci 2021,23(1),123-135. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P.; Lopes, C.; Monteiro, A.P. Uma abordagem global sobre conflitos em contexto de saúde. In: Gestão de Conflitos na Saúde; Cunha, P.C.; Monteiro, A.P. eds; Pactor: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021; pp. 1–16, ISBN: 9789896931032.

- Rangel, A.; Moreira, R.B.; Pimentão, C.; Fonte, C.; Cunha, P. A gestão construtiva de conflitos como processo de desenvolvimento pessoal e organizacional. Gestão de Conflitos na Saúde; Cunha, P.C.; Monteiro, A.P. eds; Pactor: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021; pp. 1–18, ISBN: 9789896931032.

- Shorey, S.; Wong, P.Z.E. A qualitative systematic review on nurses’ experiences of workplace bullying and implications for nursing practice. J Adv Nurs 2021,77(11),4306-4320. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, B.M.S. Mobbing – assédio moral no trabalho como fator desencadeante de stress laboral em enfermeiros. Dissertação de Mestrado, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança – Escola Superior de Saúde, Bragança, 2023. https://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/bitstream/10198/29227/1/Bruna%20Mendes.pdf.

- Teixeira, G., Lucas, P. & Gaspar, F. (2022). International Portuguese Nurse Leaders’ Insights for Multicultural Nursing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12144. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G., Lucas, P. & Gaspar, F. (2022). International Portuguese Nurse Leaders’ Insights for Multicultural Nursing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12144. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D., Figueiredo, A. R. & Lucas, P. (2024). Nurses’ Well-Being at Work in a Hospital Setting: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 12(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020173 Guo, G.; Cheng, B.; Tian, J.; Ma, J.; Gong, C. Effects of negative workplace gossip on unethical work behavior in the hospitality industry: the roles of moral disengagement and self-construal. J Hosp Mark Manag 2022,31(3),290–310. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P., Sousa, J. P., Nascimento, T., Cruchinho, P., Nunes, E., Gaspar, F., Lucas, P. (2025). Leadership Development in Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 160-185. [CrossRef]

- Guo G, Cheng B, Tian J, Ma J, Gong C. Effects of negative workplace gossip on unethical work behavior in the hospitality industry: the roles of moral disengagement and self-construal. J Hosp Mark Manag. 2022;31(3):290–310. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.Y.S.; Smith, T.; Sim, J. A conflicted tribe under pressure: a qualitative study of negative workplace behavior in nursing. J Adv Nurs 2023,79(2),711–26. [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, França, 2023. [CrossRef]

- International Council of Nurses. International Nurses Day 2024: the economic power of care; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Suíça, 2024. https://www.icn.ch/resources/publications-and-reports/international-nurses-day-2024-report.

- João, A.L.; Portela, A. Coping with workplace bullying: strategies employed by nurses in the healthcare setting. Nurs Forum 2023,23(1),1–9. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: 2024. ISBN: 978-0-6488488-2-0. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. BMC Syst Rev 2021,10:263. [CrossRef]

- Subirana, M.; Solà, I.; Garcia, J.M.; Gich, I.; Urrútia, G. A nursing qualitative systematic review required MEDLINE and CINAHL for study identification. J Clin Epidemiol 2005,58(1),20–5. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018,169(7),467–73. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc 2015,13(3),141–146. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016,5(1), 210. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., eds; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020;. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, E.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2023,21(3),520–32. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.G.; Morin, K.H.; Lake, E.T. Association of the nurse work environment with nurse incivility in hospitals. J Nurs Manag 2018,26(2),219-226. [CrossRef]

- Ayakdaş, D., Arslantaş H. Colleague violence in nursing: A cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Nurs 2018,9(1),36-44. [CrossRef]

- Bambi, S.; Guazzini, A.; Piredda, M.; Lucchini, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Rasero, L. Negative interactions among nurses: An explorative study on lateral violence and bullying in nursing work settings. J Nurs Manag 2019,27(4),749-757. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.A.; McCoy, T.P. (2017) Nurse Bullying: Impact on Nurses’ Health. West J Nurs Res 2017,39(12),1533-1546. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.E.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Cao, F. Association of workplace bullying with suicide ideation and attempt among Chinese nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2023,30(3),687-696. [CrossRef]

- Dapilah, E.; Druye, A.A. Investigating workplace bullying (WPB), intention to quit and depression among nurses in the Upper West Region of Ghana. PLoS One 2024,19(11),e0305026. [CrossRef]

- Xiaolong. T.; Gull, N.; Asghar, M.; Jianmin, Z. The relationship between polychronicity and job-affective well-being: The moderator role of workplace incivility in healthcare staff. Work 2021,70(4),1267-1277. . [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Afthanorhan, A.; Salleh, A.M.M. The mechanism of anger and negative affectivity on the occurrence of deviant workplace behavior: An empirical evidence among Malaysian nurses in public hospitals. Belitung Nurs J 2022,8(2),115-123. [CrossRef]

- Olender, L. The Relationship Between and Factors Influencing Staff Nurses' Perceptions of Nurse Manager Caring and Exposure to Workplace Bullying in Multiple Healthcare Settings. J Nurs Adm 2017,47(10),501-507. [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.G.; Peterson, C.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Desrumaux, P. When workload predicts exposure to bullying behaviours in nurses: The protective role of social support and job recognition. J Adv Nurs 2021,77(7),3093-3103. . [CrossRef]

- Elliethey, N.S.; Hashish, E.A.A.; Elbassal, N.A.M. Work ethics and its relationship with workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviours among nurses: a structural equation model. BMC Nurs 2024,23(1),126, . [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Gan, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, F.; Xiong, H.; Chang, H.; Chen, Y.; Guan, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Nurse-to-nurse horizontal violence in Chinese hospitals and the protective role of head nurse's caring and nurses' group behaviour: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag 2022,30(6),1590-1599. [CrossRef]

- Krut, B.A.; Laing, C.M.; Moules, N.J.; Estefan, A. The impact of horizontal violence on the individual nurse: A qualitative research study. Nurse Educ Pract 2021,54,103079, . [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.A. Empowering nurses to build a culture of civility. J Radiol Nurs 2022,41(2),136-138. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. New graduate registered nurses’ exposure to negative workplace behaviour in the acute care setting: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2019,93,41-54. [CrossRef]

- Edmonson, C.; Zelonka, C. Our own worst enemies: The nurse bullying epidemic. Nurs Adm Q 2019,43(3),274-279. [CrossRef]

- Anusiewicz, C.V.; Shirey, M.R.; Patrician, P.A. Workplace bullying and newly licensed registered nurses: An evolutionary concept analysis. Workplace Health Saf 2019,67(5),250-261,. [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. The concept of bullying at work: The European tradition. In: Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace. International perspectives in research and practice; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., eds. Taylor and Francis: Londres, Reino Unido, 2011; p. 3-30.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).