Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model and Method

2.1. Model

2.2. Method and Simulation Settings

2.3. Mean Force and Potential of Mean Force

3. Results and Discussion

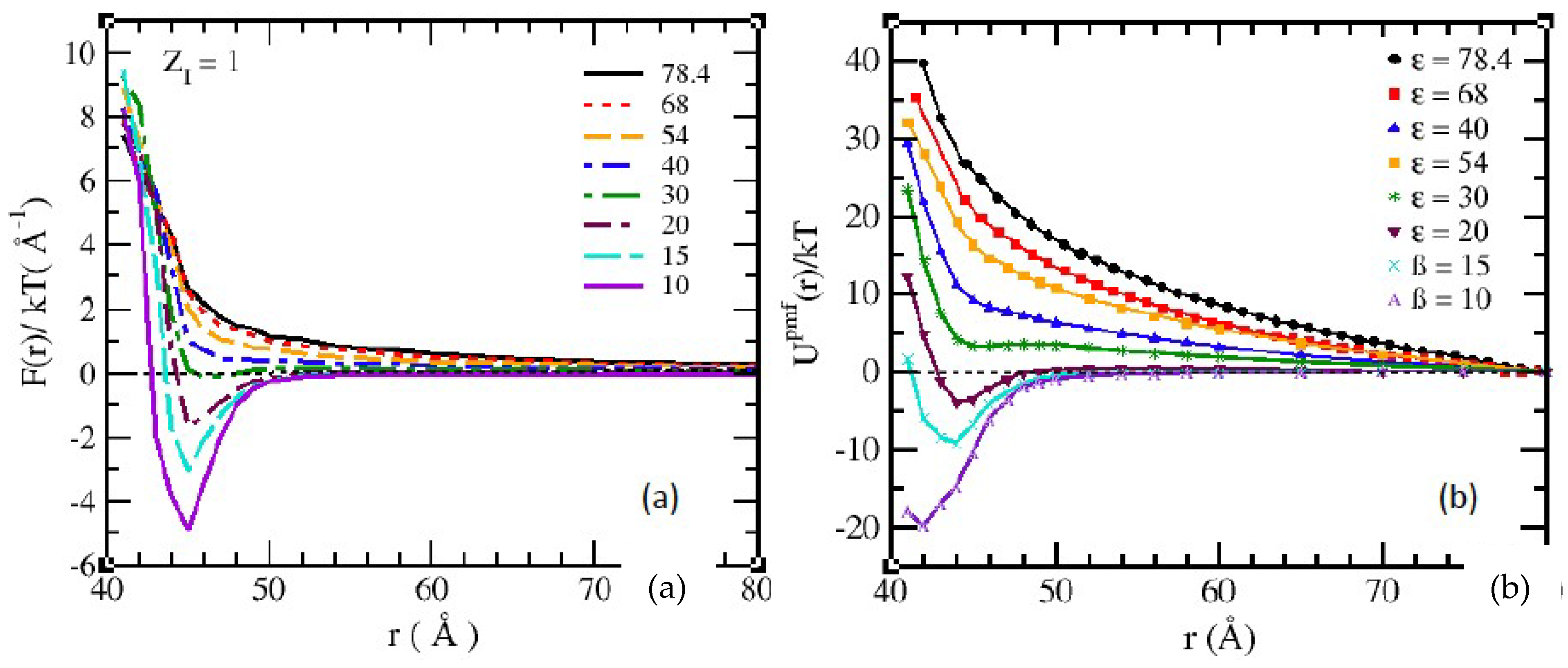

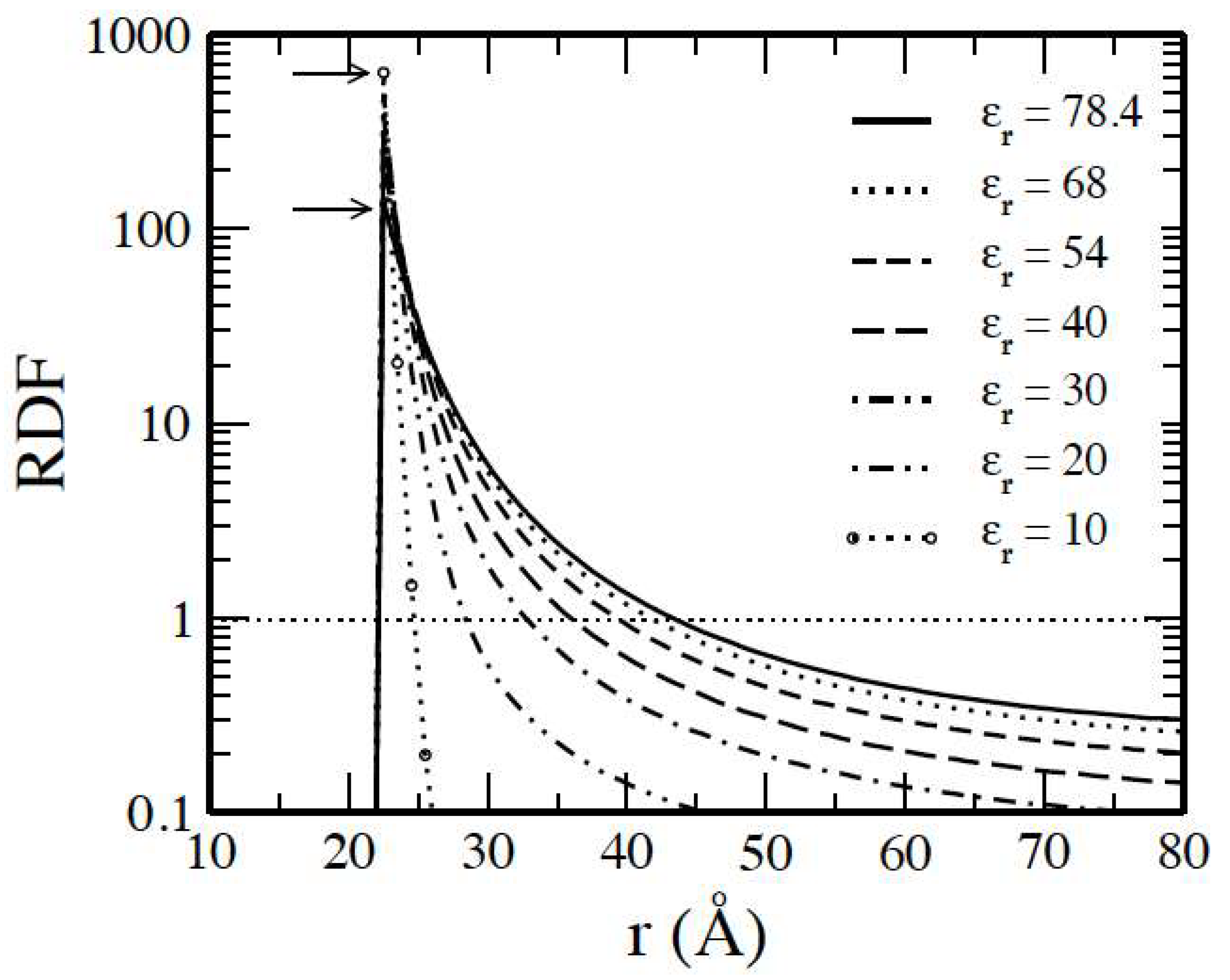

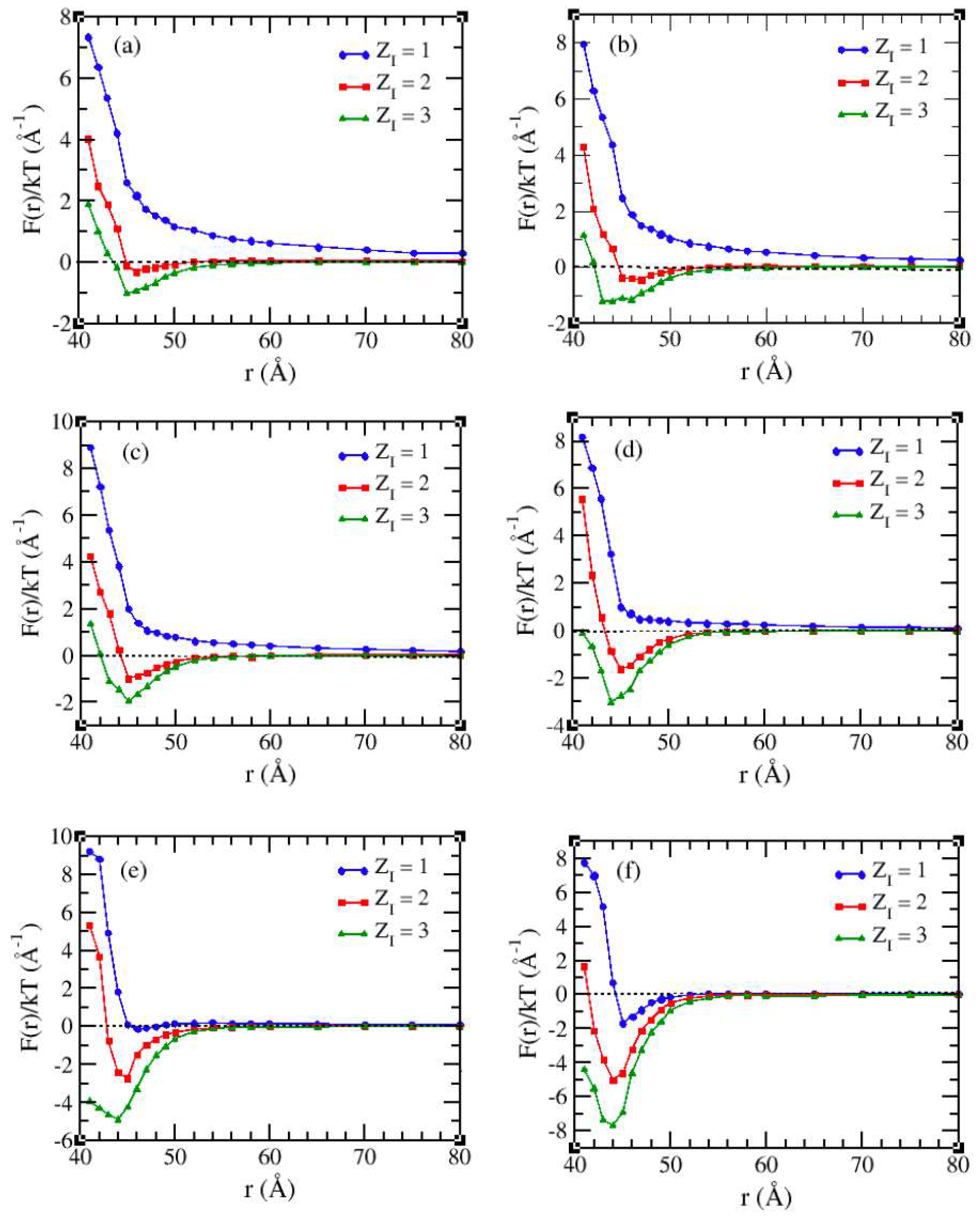

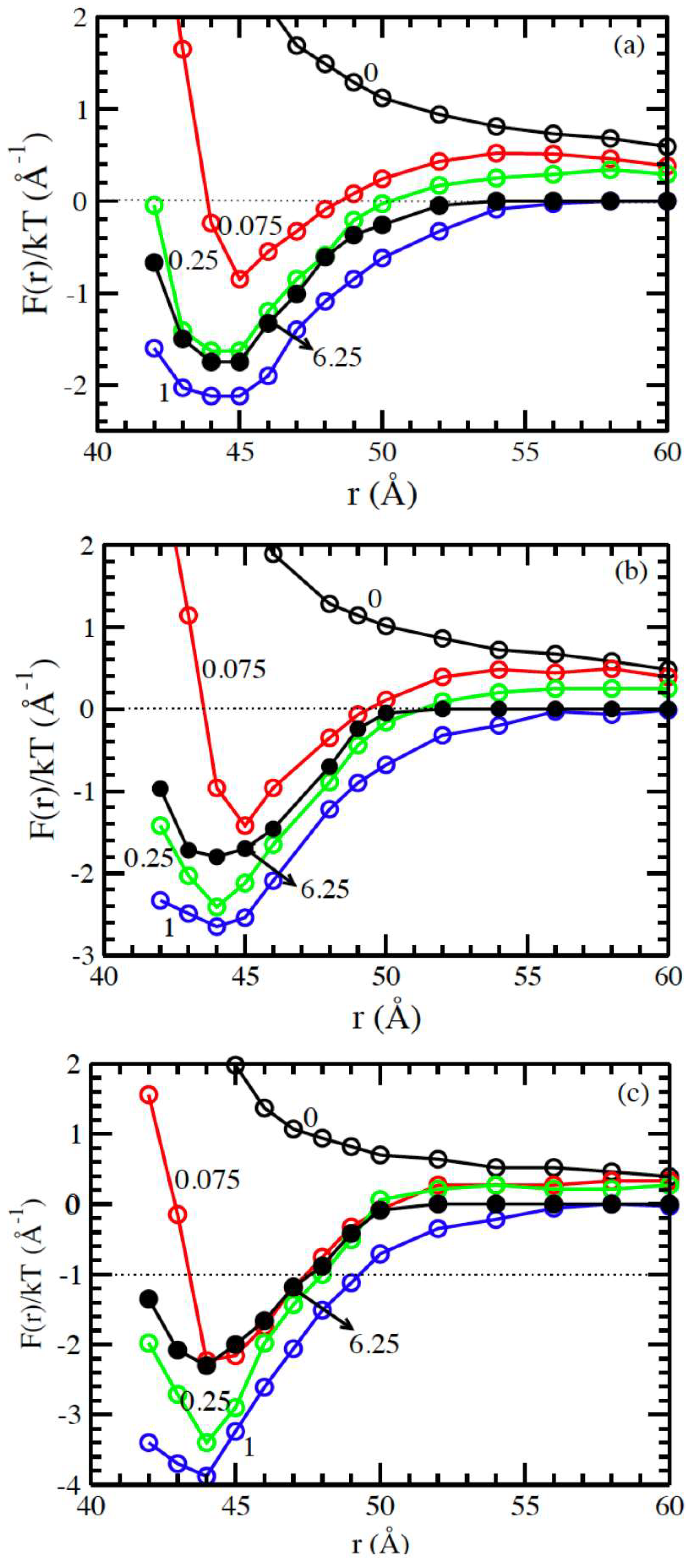

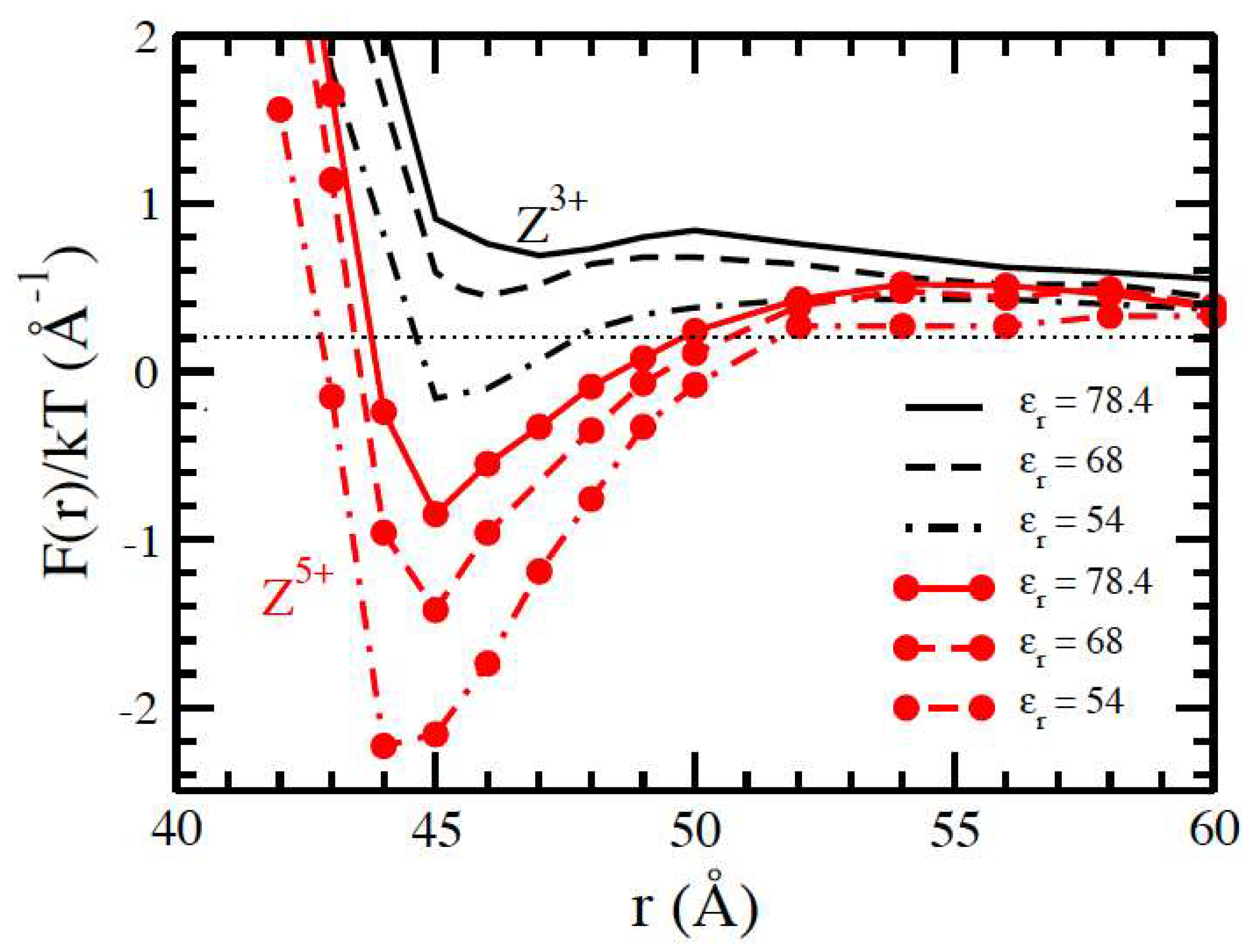

3.1. Salt-Free Solvents

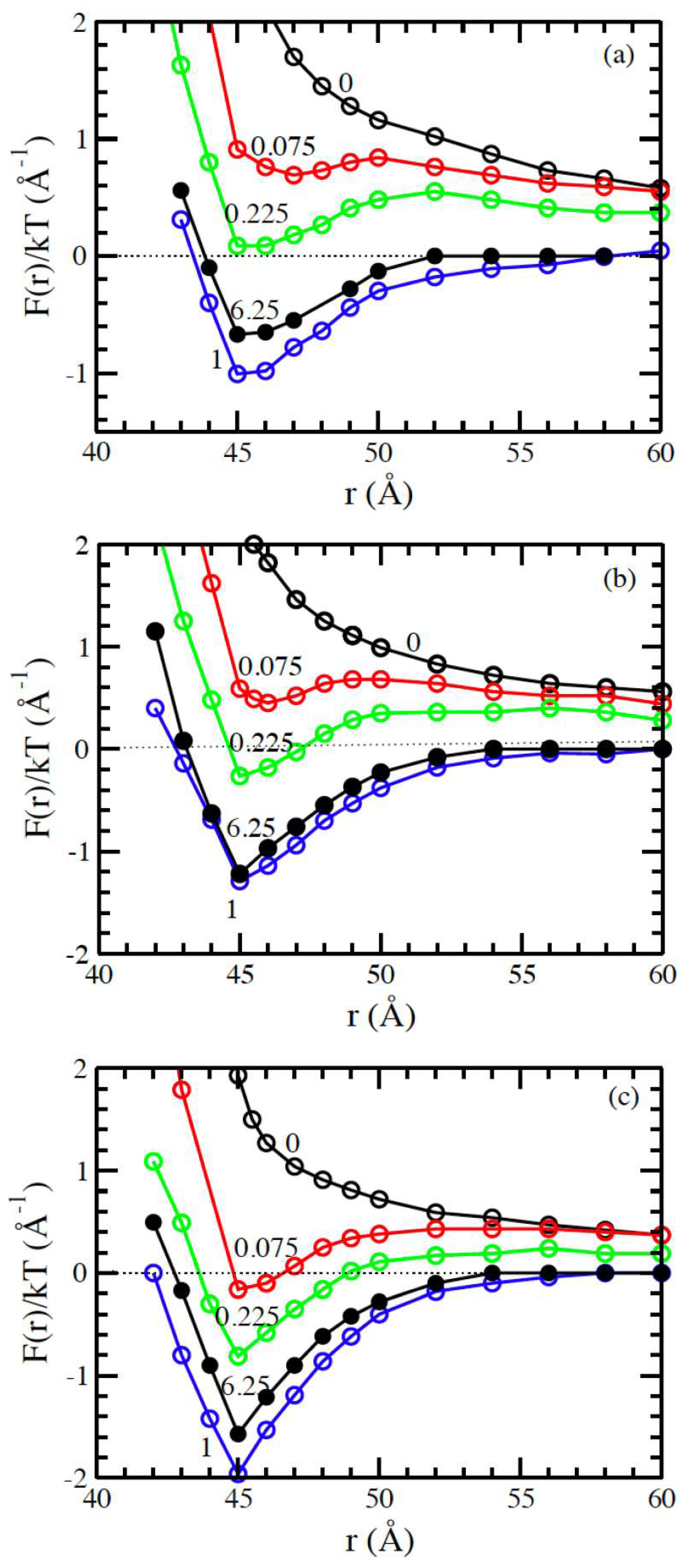

3.2. Solvents with the Presence of Added Salt

4. Conclusions

References

- Evans, D.; Wennerström, H. The Colloidal Domain: Where Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Technology Meet, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunk, W., Jr.; White, E.B. The Elements of Style, 4th ed.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X.; Lee, H.; Qiu, S. Behavior of complex knots in single DNA molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 265506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiners, J.C.; Quake, S.R. Femtonewton Force Spectroscopy of Single Extended DNA Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 5014–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, G.M.C.; Gallegos, A.; Wu, J. Modeling Surface Charge Regulation of Colloidal Particles in Aqueous Solutions. Langmuir 2020, 36, 11918–11928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobaskin, V.; Qamhieh, K. Effective Macroion Charge and Stability of Highly Asymmetric Electrolytes at Various Salt Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 8022–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Linse, P. Effect of discrete macroion charge distributions in solutions of like-charged macroions. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Nylander, T. Electrostatic interactions between cationic dendrimers and anionic model biomembrane. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2022, 246, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Amleh, M.; Khaleel, M. Effect of Discrete Macroion Charge Distributions on Electric Double Layer of a Spherical Macroion. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2013, 34, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, P. Electrostatics in the presence of spherical dielectric discontinuities. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 214505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, F.; Robben, A.; Yu, W.L.; Borkovec, M. Aggregation of colloidal particles in the presence of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes: Effect of surface charge heterogeneities. Langmuir 2001, 17, 5225–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzina, I.; Bloomfield, V.A. Macroion attraction due to electrostatic correlation between screening counterions. 1. Mobile surface-adsorbed ions and diffuse ion cloud. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 9977–9989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldbrand, L.; Jönsson, B.; Wennerström, H.; Linse, P. Electrical double layer forces. A Monte Carlo study. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 80, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, R.; Holm, C.; Kremer, K. Strong attraction between charged spheres due to metastable ionized states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Grosberg, A.Y. Electrophoresis of a charge-inverted macroion complex: Molecular-dynamics study. Eur. Phys. J. E 2002, 7, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Molina, A.; Quesada-Pérez, M.; Galisteo-González, F.; Hidalgo-Álvarez, R. Looking into overcharging in model colloids through electrophoresis: Asymmetric electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4183–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteman, K.; Zevenbergen, M.A.G.; Heering, H.A.; Lemay, S.G. Direct observation of charge inversion by multivalent ions as a universal electrostatic phenomenon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 170802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteman, K.; Zevenbergen, M.A.G.; Lemay, S.G. Charge inversion by multivalent ions: Dependence on dielectric constant and surface-charge density. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 061501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyarov, E.; Zaccarelli, E.; Sciortino, F.; Tartaglia, P.; Löwen, H. Interaction between charged colloids in a low dielectric constant solvent. EPL 2007, 78, 38002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K. Effect of dielectric constant on the zeta potential of spherical electric double layer. Molecules 2024, 29, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, P. MOLSIM; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Angelescu, D.G.; Linse, P. Monte Carlo simulation of the mean force between two like-charged macroions with simple 1:3 salt added. Langmuir 2003, 19, 9661–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, P. Mean force between like-charged macroions at high electrostatic coupling. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 13449–13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, L. Colloidal interactions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2000, 12, R549–R587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The solvent | Water | 75%water, 25%ethanol | Methyl alcohol | Glycerin | Methanol | Ethanol | Cyclohexanol | Butyl Chloral |

| Dielecrtiric constant( | 78.4 | 68 | 54 | 40 | 30 | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| 7.1 | 8.23 | 10.36 | 14.0 | 18.657 | 27.986 | 37.315 | 55.973 |

| The solvent | Water | Methyl alcohol | Glycerin | Methanol | Ethanol | Cyclohexanol | Butyl Chloral | |

| Dielecrtiric constant( | 78.4 | 68 | 54 | 40 | 30 | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| (Å) | 7.1 | 8.2 | 10.4 | 14.0 | 18.6 | 28.0 | 37.3 | 56 |

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.5`` | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 6.1 | |

| 2.3 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 8.5 | 11.6 | 17.2 | |

| 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 10.4 | 15.6 | 21.3 | 31.7 | |

| 8.9 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 16.8 | 22.4 | 33.5 | 45.8 | 68.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).