Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

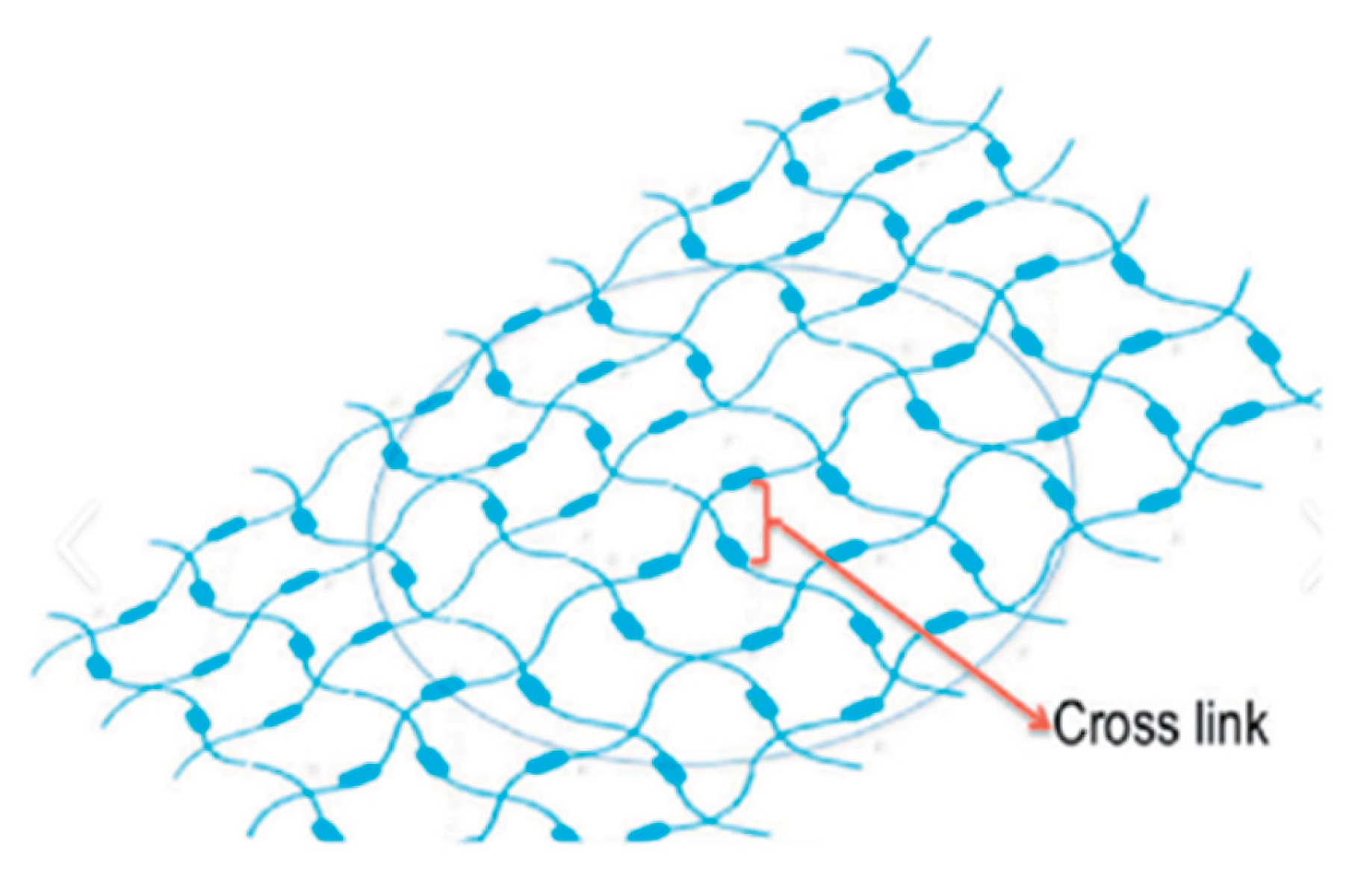

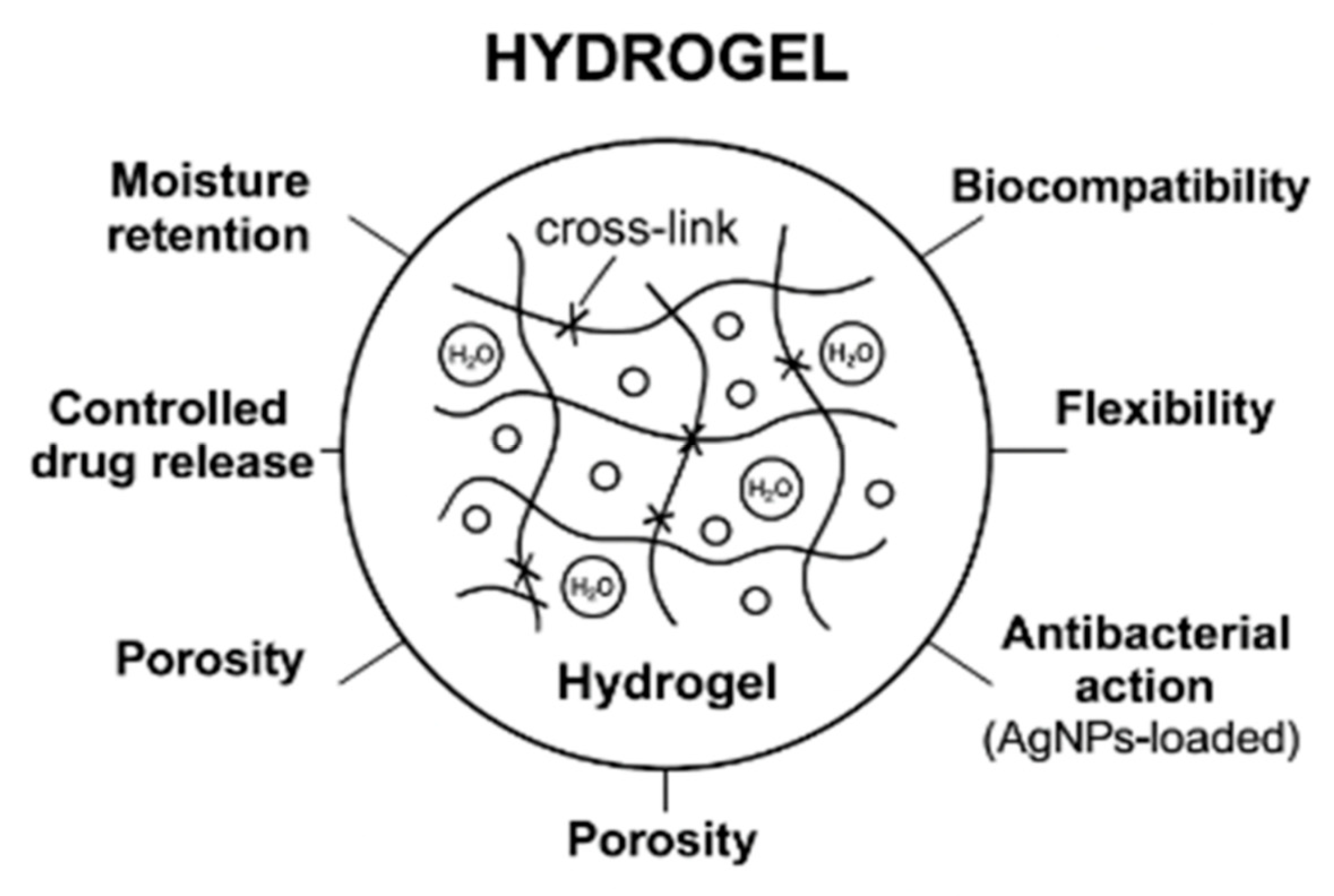

2. Hydrogel in Wound Healing

Properties of Hydrogels

-

Elevated Water Content: Hydrogels may absorb and retain over 90% of their weight in water, which helps maintain a moist wound environment. This is important for a number of reasons

- -

- Cell migration: Keratinocytes and fibroblasts, two important cells in wound closure, migrate more readily in a wet environment.

- -

- Increased epithelialization: New epithelial tissue that covers and shields the wound is formed more quickly when there is moisture present.

- -

- Decreased scab development: Hydrogels keep the wound from drying out and developing crusts, in contrast to dry dressings that encourage scab formation, which can impede healing and increase scarring.

- -

- Improved autolytic debridement: Without endangering healthy tissue, the wet environment facilitates the body’s natural enzymatic breakdown of dead tissue.[38]

-

Biocompatibility: Hydrogels may be directly applied to live tissues since they are often made of non-toxic, non-immunogenic, and chemically stable polymers. Among their advantages are:

- -

- Decreased immune response: Because hydrogels don’t cause a significant immunological or inflammatory response, they stop more tissue damage [39] .

- -

- Minimal irritation: Their neutral composition and mild hydration quality prevent stinging or burning feelings when aplied

- -

- Long-term safety: Due to their inert nature, hydrogels can be employed without running the risk of cytotoxicity for post-operative recovery or chronic wound care [40].

-

Softness and Flexibility: Hydrogels’ soft, elastic, and highly conformable physical characteristics make them perfect for wound treatment, particularly for sensitive or uneven areas:

- -

- Conform to wound geometry: Whether a wound is shallow, deep, or placed across joints or bony parts, hydrogels adapt well to the surface [41] .

- -

- Comfort of the patient: Their softness minimizes discomfort during application or removal by reducing mechanical damage to the wound and surrounding skin.

- -

- Mobility-friendly: Flexible hydrogels are perfect for active people or hard-to-dress regions since they remain in place even when the patient moves [42] .

-

Controlled Release Capability: It is possible to design hydrogels to function as drug delivery vehicles that release therapeutic chemicals locally and continuously:

- -

- Drug incorporation: Hydrogel matrices can be used to embed growth hormones, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents, and even stem cells [43] .

- -

- Targeted action: By delivering medications straight to the wound site, systemic adverse effects are decreased and local effectiveness is increased.

- -

- Profiles of sustained release: Timed release made possible by hydrogels’ porous nature guarantees a longer therapeutic effect without the need for frequent reapplication [44].

-

Non-Adhesive Nature: The majority of hydrogels do not cling to the wound bed because they are non-adherent:

- -

- Painless dressing changes: This greatly enhances patient comfort, particularly when treating chronic wounds like burns, diabetic foot ulcers, and pressure ulcers [45].

- -

- Granulation tissue preservation: When changing dressings, non-adhesive materials lessen the possibility of ripping away fresh tissue [46] .

- -

- Reduced trauma: Careful removal helps preserve the integrity of the healing wound and prevents mechanical harm [47] .

3. Silver Nanoparticles and Their Function in Wound Healing

3.1. Role Of AgNPs in Wound Healing : [50]

- ➢

-

Anti-inflammatory Effects: Although inflammation is a normal aspect of wound healing, severe or protracted inflammation can harm good tissue and slow the healing process. AgNPs assist by:

- -

- Immune response modulation: AgNPs limit excessive inflammation by lowering the overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β.

- -

- Reducing oxidative stress: They counteract reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are damaging inflammatory byproducts that might impede the healing process.

- -

- Stabilizing the wound environment: AgNPs improve the stability of the wound environment, which promotes tissue regeneration and quicker healing, by lowering inflammation.[51]

- ➢

-

Promote Collagen Synthesis: A crucial structural protein that serves as the foundation for new tissue is collagen. AgNPs increase its synthesis, which helps with:

- -

- Tissue remodeling: By strengthening the wound region and encouraging tissue regeneration, increased collagen deposition lowers the chance of a reopened wound.

- -

- Formation of the matrix: Collagen aids in the production of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is necessary for new cell structure and support.

- -

- Faster wound contraction: With more collagen, the wound edges may contract more efficiently, speeding up closure.[52]

- ➢

-

Enhanced Cellular Proliferation: Fibroblasts, the main cells in charge of producing connective tissue and healing wounds, are activated by AgNPs:

- -

- Increased fibroblast migration: AgNPs promote the migration of fibroblasts into the wound site, which is essential for starting the healing process.

- -

- Increased proliferation: By promoting cell division, they enable more fibroblasts to take part in tissue regeneration.

- -

- AgNPs may also promote the activity of keratinocytes and endothelial cells, which are essential for re-epithelialization and the development of new blood vessels. [53]

- ➢

-

Pain Reduction: Infection and inflammation are common causes of pain in wounds. AgNPs assist in easing this pain by:

- -

- Antibacterial action: They lessen discomfort associated with infections by eradicating or inhibiting a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria and fungus.

- -

- Reducing inflammatory signals: They lessen the biological causes of pain by suppressing inflammatory mediators.

- -

- Encouraging a cleaner wound environment: This lessens the need for frequent dressing changes and forceful debridement, both of which are typical causes of discomfort.[54]

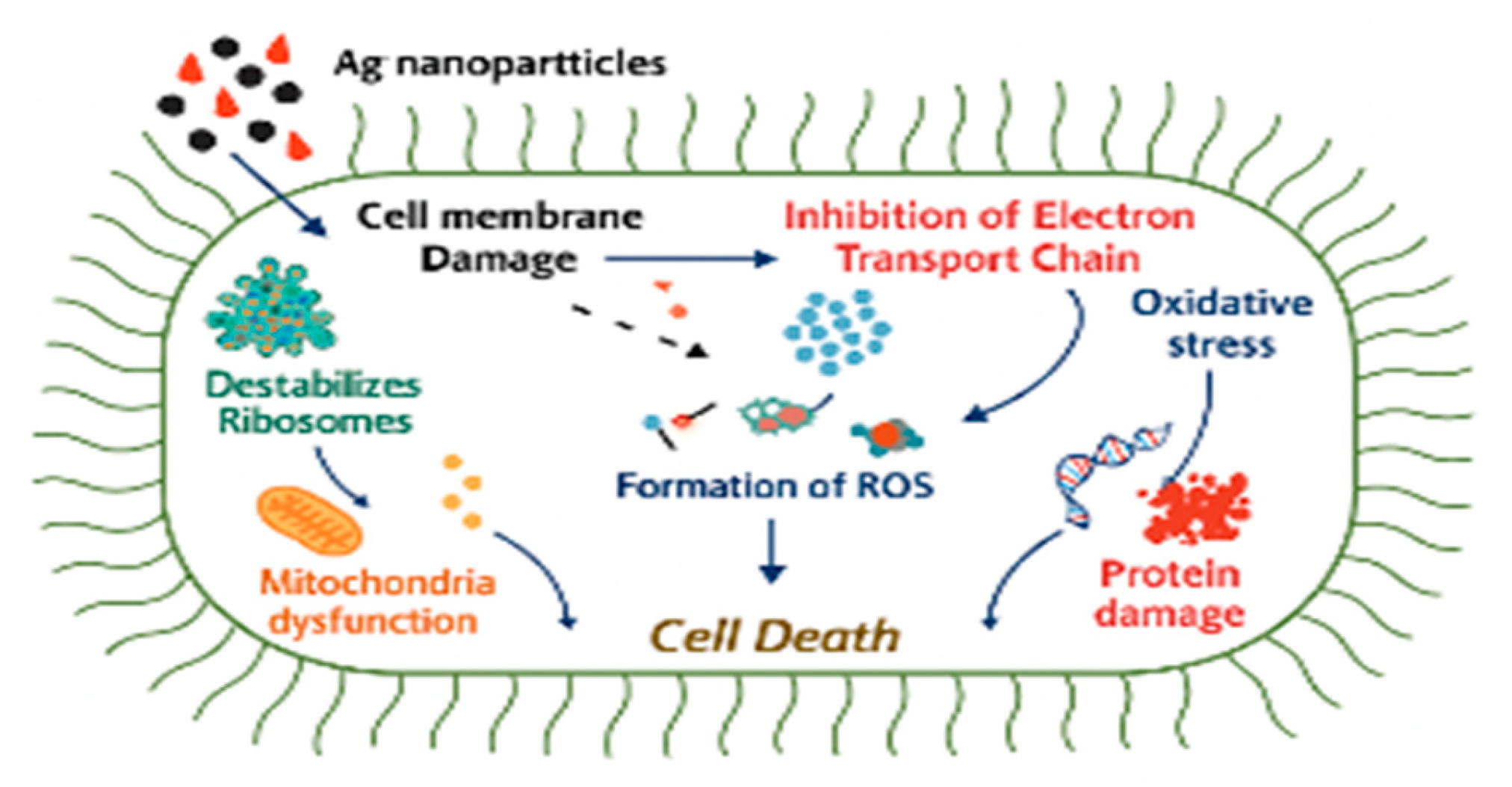

3.2. Mechanism of Action of Silver Nanoparticles in Wound Healing

- Silver nanoparticles’ continuous ion discharge might be a method of eliminating germs because of their electrostatic attraction and closer similarity to sulphur proteins, which allow them to easily bind to the cytoplasmic membrane and cell wall.[56]

- As a result of the silver ions’ attachment to the cell wall or cytoplasmic membrane, the microbial envelope is destroyed since the cell becomes more accessible. [57]

- When free silver ions are taken up by cells, they discontinue respiratory enzymes, producing ROS which stop the production of adenosine triphosphate.[58] After adhering to the cell surface, AgNPs accumulate in the pit , which leads to the membrane denaturation in a cell.[59] They have the ability to alter the composition of the cell membrane and permeate the cell wall due to their nanoscale size. [60]

- Cell rupture brought on by denaturation of the cytoplasmic membrane also results in cell lysis. Bacterial signal transduction also involves AgNPs.[61] Tyrosine residues on peptide substrates can be dephosphorylated by nanoparticles and protein substrate phosphorylation, which eventually impacts bacterial signal transmission. Cell death and the end of cell division can be accompanied by disruptions in signal transmission.[62]

- This promotes wound healing through tissue remodeling.

4. Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibitor and Their Role in Wound Healing [64]

- A class of antimicrobial drugs known as cell wall synthesis inhibitors causes bacterial cells to lyse and die by interfering with the formation of their cell walls. These substances are particularly important for treating bacterial wound infections .[65]

4.1. Types of Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibitors Used in Wound Care

-

Beta-lactam Antibiotics:

- -

- -

- Cephalosporins : Similar to penicillin’s, cephalosporins are frequently utilized because to their wider range of activity, which includes their ability to effectively combat several resistant types.[68]

- -

- Carbapenem : Because of their broad-spectrum action, carbapenems are used to treat infections that are more severe or resistant to many drugs.[69]

-

Glycopeptides :

- -

- Vancomycin : Gram-positive bacterial illnesses, especially those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), frequently treated with this glycopeptide antibiotic.[70]

- -

- Teicoplanin : This infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to vancomycin are treated with glycopeptide..[71]

- -

4.2. Mechanism of Action Of Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibitors in wound healing

-

Inhibition of Peptidoglycan Cross-Linking : [74]

- -

- These medications primarily target the bacterial cell wall, namely the peptidoglycan synthesis, which provides the wall its stiffness.[75]

- -

- -

- In the latter phases of peptidoglycan enzymes known as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) facilitate cross-linking are inhibited by penicillin’s and cephalosporins. This causes bacterial cell lysis by weakening the cell wall.[78]

-

Prevention of Bacterial Growth:

- -

- These medications stop the manufacture of cell walls, which stops bacteria from growing and dividing normally.[79]

- -

-

Reduction of Inflammation and Infection:

- -

- -

- This aids in reducing pain, enhancing tissue oxygenation, and managing wound exudate—all of which are critical for fostering healing.[84]

-

Allowing for Normal Healing Processes:

- -

- Cell wall synthesis inhibitors reduce infection-related damage by preventing bacterial growth, creating a healing environment.[85]

5. Synergistic Dual-Action Strategy of Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibitors Plus Silver Nanoparticles for Wound Infection Control

- -

- The synergistic actions of cell wall synthesis inhibitors and silver nanoparticles improve the antimicrobial capacity .[86]

- -

- The combination of Ag-NP infused hydrogels and cell wall synthesis inhibitors provides a dual-action strategy to control wound infections:[87]

-

Antimicrobial Action:

-

Reduced Resistance Development:

- -

- A major benefit over single-agent treatments is that the twin modes of action—membrane rupture and cell wall inhibition—make it more difficult for bacteria to become resistant.[90]

-

Enhanced Healing:

- -

- By lowering inflammation, boosting collagen production, and stimulating cell proliferation, the combination not only gets rid of bacterial infections but also speeds up wound healing.[91]

-

Faster Bacterial Killing:

-

Controlled Release Systems :

- -

- AgNPs and antibiotics can be delivered in a regulated way using hydrogels, guaranteeing sustained antibacterial action at the wound site while reducing systemic toxicity.[94] By increasing the therapeutic concentration of both drugs in the wound, this targeted administration can maximize effectiveness while reducing adverse effects.[95]

6. Clinical Applications of this Dual Action Strategy

-

Chronic Wounds :-

- -

- Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Action: (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), are just a few of the MDR pathogens that the AgNPs in the hydrogel system exhibit strong effectiveness against.[96]

- -

- Controlled Release: The hydrogel system ensures long-lasting antibacterial action and lessens the need for frequent dressing changes by enabling the steady, regulated release of antibiotics and AgNPs at the wound site.[97]

- -

- Biofilm Disruption: By efficiently breaking up bacterial biofilms, which are frequently present in chronic wounds, AgNPs increase the effectiveness of therapy by facilitating antibiotic penetration.[98]

- -

- Enhanced Healing: AgNPs and antibiotics work together to lower inflammation, manage infection, and encourage collagen production, all of which hasten wound closure and tissue healing. [99]

-

Diabetic Foot Infections :

- -

- Targeted Infection Control: AgNPs work very well against MRSA, species, which are frequent causes of foot infections in diabetics. Antibiotics are added to improve antimicrobial coverage even further.[100]

- -

- Prevents Amputations: The hydrogel lowers the risk of tissue necrosis and amputation by regulating infection and encouraging quicker healing, which is a major worry for diabetes patients.[101]

-

Surgical Site Infections :

- -

- Prophylactic Infection Control: In high-risk operations (such as orthopedic, abdominal, or cardiovascular procedures), the hydrogel system can be utilized as a preventative measure to avoid infection at the operative site.[102]

- -

- Minimal Tissue Irritation: Because the hydrogel is biocompatible, it creates a non-irritating environment that lowers the likelihood of problems that come with using traditional post-surgical ointments or lotions.[103]

7. Conclusions

8. Future Perspective

References

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. Journal of advanced research. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpure, P.S.; Patil, S.S.; More, Y.M.; Nikam, P.P. A review on-hydrogel. Am J PharmTech Res. 2018, 8, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, F.; Vasheghani, F.S.; Vasheghani, F.E. Theoretical description of hydrogel swelling: a review.

- Garg, S.; Garg, A.; Vishwavidyalaya, R.D. Hydrogel: Classification, properties, preparation and technical features. Asian J. Biomater. Res. 2016, 2, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Pérez-Puyana, V. Novel trends in hydrogel development for biomedical applications: A review. Polymers. 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Othman, M.B.; Javed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Akil, H.M. Classification, processing and application of hydrogels: A review. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2015, 57, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiet, T.; Vandenhaute, M.; Schelfhout, J.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P. A review of trends and limitations in hydrogel-rapid prototyping for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2012, 33, 6020–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, H.; Harahap, H.; Dalimunthe, N.F.; Ginting, M.H.; Jaafar, M.; Tan, O.O.; Aruan, H.K.; Herfananda, A.L. Hydrogel and effects of crosslinking agent on cellulose-based hydrogels: A review. Gels. 2022, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R. Cross-linked hydrogel for pharmaceutical applications: a review. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin. 2017, 7, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, M.L. Mechanical characterisation of hydrogel materials. International Materials Reviews. 2014, 59, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Azadi, A.; Rafiei, P. Hydrogel nanoparticles in drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2008, 60, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, S.H.; Mohd, N.H.; Suhaili, N.; Anuar, F.H.; Lazim, A.M.; Othaman, R. Preparation of cellulose-based hydrogel: A review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2021, 10, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Cheng, D. Environmentally friendly hydrogel: A review of classification, preparation and application in agriculture. Science of the Total Environment. 2022, 846, 157303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Fu, Q.Q.; Wang, M.H.; Gao, H.L.; Dong, L.; Zhou, P.; Cheng, D.D.; Chen, Y.; Zou, D.H.; He, J.C.; Feng, X. Designing nanohesives for rapid, universal, and robust hydrogel adhesion. Nature Communications. 2023, 14, 5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, F.R.; Maia, R.C.; de Andrade, L.R.; Andrade, L.N.; Vinicius Chaud, M.; da Silva, C.F.; Corrêa, C.B.; de Albuquerque Junior, R.L.; Pereira da Costa, L.; Shin, S.R.; Hassan, S. Silver nanoparticles-composing alginate/gelatine hydrogel improves wound healing in vivo. Nanomaterials. 2020, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakheel, F.M.; Sayed, M.M.; Mohsen, D.; Fagir, M.H.; El Dein, D.K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles loaded hydrogel for wound healing; systematic review. Gels. 2023, 9, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Fan, Z. Novel chitosan hydrogels reinforced by silver nanoparticles with ultrahigh mechanical and high antibacterial properties for accelerating wound healing. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2018, 119, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ly, K.L.; Tran, A.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Vo, M.T.; Ho, H.M.; Dang, N.T.; Vo, V.T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Nguyen, T.T. In vivo study of the antibacterial chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol loaded with silver nanoparticle hydrogel for wound healing applications. International Journal of Polymer Science. 2019, 2019, 7382717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Rajendran, N.K.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Recent advances on silver nanoparticle and biopolymer-based biomaterials for wound healing applications. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2018, 115, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami Nejad, A.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.S. In situ synthesis of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles within antifouling zwitterionic hydrogels by catecholic redox chemistry for wound healing application. Biomacromolecules. 2016, 17, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, G.; Chandrasekharan, S.; Koh, T.W.; Bhatnagar, S. Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial and wound healing efficacy of silver nanoparticles from Azadirachta indica. Frontiers in microbiology. 2021, 12, 611560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Farooq, M.A. Therapeutic potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles loaded PVA hydrogel patches for wound healing. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2019, 54, 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampieng, T.; Wongkittithavorn, S.; Chaiarwut, S.; Ekabutr, P.; Pavasant, P.; Supaphol, P. Silver nanoparticles-based hydrogel: Characterization of material parameters for pressure ulcer dressing applications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2018, 44, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nešović, K.; Mišković-Stanković, V. A comprehensive review of the polymer-based hydrogels with electrochemically synthesized silver nanoparticles for wound dressing applications. Polymer Engineering & Science. 2020, 60, 1393–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Nqakala, Z.B.; Sibuyi, N.R.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, M.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M. Advances in nanotechnology towards development of silver nanoparticle-based wound-healing agents. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021, 22, 11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; George, E.; Saxena, N.; Sen, S. Silver-nanoparticle-entrapped soft GelMA gels as prospective scaffolds for wound healing. ACS Applied Bio Materials. 2019, 2, 1802–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varaprasad, K.; Mohan, Y.M.; Ravindra, S.; Reddy, N.N.; Vimala, K.; Monika, K.; Sreedhar, B.; Raju, K.M. Hydrogel–silver nanoparticle composites: A new generation of antimicrobials. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2010, 115, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massironi, A.; Franco, A.R.; Babo, P.S.; Puppi, D.; Chiellini, F.; Reis, R.L.; Gomes, M.E. Development and characterization of highly stable silver nanoparticles as novel potential antimicrobial agents for wound healing hydrogels. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, F.; Pollini, M. Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles for wound healing application: progress and future trends. Materials. 2019, 12, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novientri, G.; Abbas, G.H.; Budianto, E. Nanocomposite hydrogel-based biopolymer modified with silver nanoparticles as an antibacterial material for wound treatment. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2019, 9, 001–009. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar, K.; Won, S.Y.; Han, S.S. Gelatin stabilized silver nanoparticles for wound healing applications. Materials Letters. 2022, 325, 132851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidari, H.; Bright, R.; Strudwick, X.L.; Garg, S.; Vasilev, K.; Cowin, A.J.; Kopecki, Z. Multifunctional ultrasmall AgNP hydrogel accelerates healing of S. aureus infected wounds. Acta Biomaterialia. 2021, 128, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. An antifouling hydrogel containing silver nanoparticles for modulating the therapeutic immune response in chronic wound healing. Langmuir. 2018, 35, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhe, T.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Lu, Q.; Wang, J. Silver nanoparticle-embedded hydrogel as a photothermal platform for combating bacterial infections. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2020, 382, 122990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybka, M.; Mazurek, Ł.; Konop, M. Beneficial effect of wound dressings containing silver and silver nanoparticles in wound healing—from experimental studies to clinical practice. Life. 2022, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Yarlagadda, V.; Ghosh, C.; Haldar, J. A review on cell wall synthesis inhibitors with an emphasis on glycopeptide antibiotics. Medchemcomm. 2017, 8, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasz, A.; Waks, S. Mechanism of action of penicillin: triggering of the pneumococcal autolytic enzyme by inhibitors of cell wall synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1975, 72, 4162–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomanen, E. Newly made enzymes determine ongoing cell wall synthesis and the antibacterial effects of cell wall synthesis inhibitors. Journal of bacteriology. 1986, 167, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.C.; Mashalidis, E.H.; Tanino, T.; Kim, M.; Matsuda, A.; Hong, J.; Ichikawa, S.; Lee, S.Y. Structural insights into inhibition of lipid I production in bacterial cell wall synthesis. Nature. 2016, 533, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, S.; Sosio, M. Inhibitors of Cell-Wall Synthesis. Targets, Mechanisms and Resistance. 2014.

- Hao, H.; Cheng, G.; Dai, M.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, Z. Inhibitors targeting on cell wall biosynthesis pathway of MRSA. Molecular Bio Systems. 2012, 8, 2828–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.M.; Zaworski, P.G.; Parker, C.N. A high throughput screen for inhibitors of fungal cell wall synthesis. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2002, 7, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, T.G.; Roof, W.D.; Young, R. Genetic evidence that the bacteriophage φX174 lysis protein inhibits cell wall synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000, 97, 4297–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhashi, M.; Ohara, I.; Yoshiyama, Y. Inhibition of the Bacterial Cell Wall Synthesis in vitro by Enduracidin, a New Polypeptide Antibiotic. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1969, 33, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, E.R.; Huang, K.C.; Theriot, J.A. Homeostatic cell growth is accomplished mechanically through membrane tension inhibition of cell-wall synthesis. Cell systems. 2017, 5, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Muñoz, R.; Meza-Villezcas, A.; Fournier, P.G.; Soria-Castro, E.; Juarez-Moreno, K.; Gallego-Hernández, A.L.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Vazquez-Duhalt, R.; Huerta-Saquero, A. Enhancement of antibiotics antimicrobial activity due to the silver nanoparticles impact on the cell membrane. PloS one. 2019, 14, e0224904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Patil, S.; Ahire, M.; Kitture, R.; Kale, S.; Pardesi, K.; Cameotra, S.S.; Bellare, J.; Dhavale, D.D.; Jabgunde, A.; Chopade, B.A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Dioscorea bulbifera tuber extract and evaluation of its synergistic potential in combination with antimicrobial agents. International journal of nanomedicine. 2012, 483–496. [Google Scholar]

- Barapatre, A.; Aadil, K.R.; Jha, H. Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by lignin-degrading fungus. Bioresources and BioproHwang IS, Hwang JH, Choi H, Kim KJ, Lee DG.

- Synergistic effects between silver nanoparticles and antibiotics and the mechanisms involved. Journal of medical microbiology. 2012, 61, 1719–1726.cessing. [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, A.M.; Balaji, K.; Girilal, M.; Yadav, R.; Kalaichelvan, P.T.; Venketesan, R. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their synergistic effect with antibiotics: a study against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2010, 6, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; McShan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sinha, S.S.; Arslan, Z.; Ray, P.C.; Yu, H. Mechanistic study of the synergistic antibacterial activity of combined silver nanoparticles and common antibiotics. Environmental science & technology. 2016, 50, 8840–8848. [Google Scholar]

- Smekalova, M.; Aragon, V.; Panacek, A.; Prucek, R.; Zboril, R.; Kvitek, L. Enhanced antibacterial effect of antibiotics in combination with silver nanoparticles against animal pathogens. The veterinary journal. 2016, 209, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombre, R.S.; Shinde, V.; Thaiparambil, E.; Zende, S.; Mehta, S. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of inhibition of silver nanoparticles against extreme halophilic archaea. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016, 7, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Han, H. Synergistic antibacterial effects of curcumin modified silver nanoparticles through ROS-mediated pathways. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2019, 99, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Lekshmi, G.S.; Ostrikov, K.; Lussini, V.; Blinco, J.; Mohandas, M.; Vasilev, K.; Bottle, S.; Bazaka, K.; Ostrikov, K. Synergic bactericidal effects of reduced graphene oxide and silver nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Scientific reports. 2017, 7, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Shan, S.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. Synergistic antimicrobial effects of polyaniline combined with silver nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2012, 125, 3560–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Batista, J.G.; Rodrigues, M.Á.; Thipe, V.C.; Minarini, L.A.; Lopes, P.S.; Lugão, A.B. Advances in silver nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on their potential as antimicrobial agents and their mechanisms of action elucidated by proteomics. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2024, 15, 1440065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar-Krishnan, S.; Prokhorov, E.; Hernández-Iturriaga, M.; Mota-Morales, J.D.; Vázquez-Lepe, M.; Kovalenko, Y.; Sanchez, I.C.; Luna-Bárcenas, G. Chitosan/silver nanocomposites: Synergistic antibacterial action of silver nanoparticles and silver ions. European Polymer Journal. 2015, 67, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S. Biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles enhances antibiotic activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 2015, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilich, B.M.; van de Ven, A.L.; Singleton, G.L.; Sepúlveda, L.J.; Sridhar, S.; Webster, T.J. Silver nanoparticle-embedded polymersome nanocarriers for the treatment of antibiotic-resistant infections. Nanoscale. 2015, 7, 3511–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franci, G.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S.; Palomba, L.; Rai, M.; Morelli, G.; Galdiero, M. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules. 2015, 20, 8856–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, M.; Sedeh, A.N.; Motamedi, H.; Rezatofighi, S.E. Magnetic graphene oxide inlaid with silver nanoparticles as antibacterial and drug delivery composite. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2018, 102, 3607–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasher, P.; Singh, M.; Mudila, H. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial therapeutics: current perspectives and future challenges. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.S.; Singh, P.; Mijakovic, I. Interactions of gold and silver nanoparticles with bacterial biofilms: Molecular interactions behind inhibition and resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020, 21, 7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Functional silver nanoparticle as a benign antimicrobial agent that eradicates antibiotic-resistant bacteria and promotes wound healing. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2016, 8, 25798–25807. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, A.; Preet, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R. Synergetic effect of vancomycin loaded silver nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial activity. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2019, 176, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisan, C.M.; Mocan, T.; Manolea, M.; Lasca, L.I.; Tăbăran, F.A.; Mocan, L. Review on silver nanoparticles as a novel class of antibacterial solutions. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, N.; Kaur, G.; Kumar, N.; Tiwari, A. APPLICATION OF SILVER NANOPARTICLES IN VIRAL INHIBITION: A NEW HOPE FOR ANTIVIRALS. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials & Biostructures (DJNB).

- Barua, N.; Buragohain, A.K. Therapeutic Potential of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) as an Antimycobacterial Agent: A Comprehensive Review. Antibiotics. 2024, 13, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, F.; Pollini, M. Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles for wound healing application: progress and future trends. Materials. 2019, 12, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovska, J.; Zvicer, J.; Obradovic, B. Preclinical functional characterization methods of nanocomposite hydrogels containing silver nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2020, 104, 4643–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Constantin, M.; Solcan, G.; Ichim, D.L.; Rata, D.M.; Horodincu, L.; Solcan, C. Composite hydrogels with embedded silver nanoparticles and ibuprofen as wound dressing. Gels. 2023, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, D. In situ reduction of silver nanoparticles by sodium alginate to obtain silver-loaded composite wound dressing with enhanced mechanical and antimicrobial property. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020, 148, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, M.T.; Lincopan, N.; Santos, P.M.; Ramirez, P.A.; Brant, A.J.; Riella, H.G.; Lugão, A.B. Simultaneous hydrogel crosslinking and silver nanoparticle formation by using ionizing radiation to obtain antimicrobial hydrogels. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2020, 169, 108777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.; Soni, S.; Patial, V.; Kulurkar, P.M.; Kumari, A.; Padwad, Y.S.; Yadav, S.K. In vivo diabetic wound healing potential of nanobiocomposites containing bamboo cellulose nanocrystals impregnated with silver nanoparticles. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2017, 105, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baukum, J.; Pranjan, J.; Kaolaor, A.; Chuysinuan, P.; Suwantong, O.; Supaphol, P. The potential use of cross-linked alginate/gelatin hydrogels containing silver nanoparticles for wound dressing applications. Polymer Bulletin. 2020, 77, 2679–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katas, H.; Mohd Akhmar, M.A.; Suleman Ismail Abdalla, S. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles loaded in gelatine hydrogel for a natural antibacterial and anti-biofilm wound dressing. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 2021, 36, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, P.; Ho, J.K.; Jin, R.; Zhang, L.; Shao, H.; Han, C. Silver nanoparticle loaded collagen/chitosan scaffolds promote wound healing via regulating fibroblast migration and macrophage activation. Scientific reports. 2017, 7, 10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandhini, J.; Karthikeyan, E.; Rani, E.E.; Karthikha, V.S.; Sanjana, D.S.; Jeevitha, H.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Venugopal, V.; Priyadharshan, A. Advancing engineered approaches for sustainable wound regeneration and repair: Harnessing the potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. Engineered Regeneration. 2024, 5, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astaneh, M.E.; Fereydouni, N. Silver Nanoparticles in 3D Printing: A New Frontier in Wound Healing. ACS omega. 2024, 9, 41107–41129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, P.; Neves Amaral, M.; Neves, A.; Ferreira-Gonçalves, T.; Viana, A.S.; Catarino, J.; Faísca, P.; Simões, S.; Perdigão, J.; Charmier, A.J.; Gaspar, M.M. Pluronic® F127 hydrogel containing silver nanoparticles in skin burn regeneration: an experimental approach from fundamental to translational research. Gels. 2023, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, K.; Won, S.Y.; Han, S.S. Gelatin stabilized silver nanoparticles for wound healing applications. Materials Letters. 2022, 325, 132851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, H.; Pandey, M.; Lim, Y.Q.; Low, C.Y.; Lee, C.T.; Marilyn, T.C.; Loh, H.S.; Lim, Y.P.; Lee, C.F.; Bhattamishra, S.K.; Kesharwani, P. Silver nanoparticles: Advanced and promising technology in diabetic wound therapy. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2020, 112, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, Q. Silver Nanoparticles Incorporated Chitosan Hydrogel as a Potential Dressing Material for Diabetic Wound Healing in Nursing Care. Ind. J. Pharm. Edu. Res. 2024, 58, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonkaew, B.; Suwanpreuksa, P.; Cuttle, L.; Barber, P.M.; Supaphol, P. Hydrogels containing silver nanoparticles for burn wounds show antimicrobial activity without cytotoxicity. Journal of Applied Polymer Science.

- Alavi, M.; Varma, R.S. Antibacterial and wound healing activities of silver nanoparticles embedded in cellulose compared to other polysaccharides and protein polymers. Cellulose. 2021, 28, 8295–8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, H.; Singh, S.; Kashyap, P.; Singh, A.; Kumar, G. Advancing biomedical applications: An in-depth analysis of silver nanoparticles in antimicrobial, anticancer, and wound healing roles. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2024, 15, 1438227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Lu, T.; Zhang, P.; Jing, X. Preparation and antibacterial effects of PVA-PVP hydrogels containing silver nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2007, 103, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, A. Radiation synthesis of hydrogels with silver nanoparticles for use as an antimicrobial burn wound dressing. Polymer Science, Series B. 2022, 64, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanema, N.S.; Mansur, A.A.; Carvalho, S.M.; Mansur, L.L.; Ramos, C.P.; Lage, A.P.; Mansur, H.S. Physicochemical properties and antimicrobial activity of biocompatible carboxymethylcellulose-silver nanoparticle hybrids for wound dressing and epidermal repair. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2018, 135, 45812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakheel, F.M.; Sayed, M.M.; Mohsen, D.; Fagir, M.H.; El Dein, D.K. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Loaded Hydrogel for Wound Healing; Systematic Review. Gels 2023, 9, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, J.; Catanzano, O. Silver and silver nanoparticle-based antimicrobial dressings. Therapeutic dressings and wound healing applications. 2020, 157–184. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon, E.I.; Udekwu, K.I.; Noel, C.W.; Gagnon, L.B.; Taylor, P.K.; Vulesevic, B.; Simpson, M.J.; Gkotzis, S.; Islam, M.M.; Lee, C.J.; Richter-Dahlfors, A. Safety and efficacy of composite collagen–silver nanoparticle hydrogels as tissue engineering scaffolds. Nanoscale. 2015, 7, 18789–18798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Z.; Abubaker, M.A.; Ding, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Fan, Z. Antibacterial polyvinyl alcohol/bacterial cellulose/nano-silver hydrogels that effectively promote wound healing. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2021, 126, 112171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiangnoon, R.; Karawak, P.; Eamsiri, J.; Nuchdang, S.; Thamrongsiripak, N.; Neramitmansook, N.; Pummarin, S.; Pimton, P.; Nilgumhang, K.; Uttayarat, P. Antibacterial hydrogel sheet dressings composed of poly (vinyl alcohol) and silver nanoparticles by electron beam irradiation. Gels. 2023, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, H.; Ceylan, D. Multi-responsive shape memory and self-healing hydrogels with gold and silver nanoparticles. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2025, 13, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazin, A.; Shirazi, F.A.; Shafiei, M. Natural biomarocmolecule-based antimicrobial hydrogel for rapid wound healing: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023, 244, 125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Jia, R.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Qin, Z. Preparation and application of sustained-release antibacterial alginate hydrogels by loading plant-mediated silver nanoparticles. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2024, 12, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, A.; Azandeh, S.; Orazizadeh, M.; Bayati, V.; Rafienia, M.; Karami, M.A. Fabrication and characterisation of chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol-based transparent hydrogel films loaded with silver nanoparticles and sildenafil citrate for wound dressing applications. Materials Technology. 2022, 37, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Witkowska, A.M.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Silver nanoparticles in therapeutics and beyond: A review of mechanism insights and applications. Nanomaterials. 2024, 14, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Behl, T.; Chadha, S. Synthesis of physically crosslinked PVA/Chitosan loaded silver nanoparticles hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties and antibacterial effects. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2020, 149, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, S.; Mulaba-Bafubiandi, A.F.; Rajinikanth, V.; Varaprasad, K.; Narayana Reddy, N.; Mohana Raju, K. Development and characterization of curcumin loaded silver nanoparticle hydrogels for antibacterial and drug delivery applications. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials. 2012, 22, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyashri, G.; Badhe, R.V.; Sadanandan, B.; Vijayalakshmi, V.; Kumari, M.; Ashrit, P.; Bijukumar, D.; Mathew, M.T.; Shetty, K.; Raghu, A.V. Applications of hydrogel-based delivery systems in wound care and treatment: an up-to-date review. Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 2022, 33, 2025–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, P.; Celik, M.; Ustun, M.; Saha, S.; Saha, C.; Kacar, E.A.; Kugu, S.; Karagulle, E.N.; Tasoglu, S.; Buyukserin, F.; Mondal, R. Wound healing strategies based on nanoparticles incorporated in hydrogel wound patches. RSC advances. 2023, 13, 21345–21364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.N.; Rouzé, R.; Quilty, B.; Alves, G.G.; Soares, G.D.; Thiré, R.M.; McGuinness, G.B. Mechanical properties and in vitro characterization of polyvinyl alcohol-nano-silver hydrogel wound dressings. Interface focus. 2014, 4, 20130049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M.; Wen, T.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Liu, H. Preparation and application of quaternized chitosan-and AgNPs-base synergistic antibacterial hydrogel for burn wound healing. Molecules. 2021, 26, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albao, M.J.; Calsis, J.R.; Dancel, J.O.; De Juan-Corpuz, L.M.; Corpuz, R.D. Silver nanoparticle-infused hydrogels for biomedical applications: A comprehensive review. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society. 2025, 72, 124–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Esther Jinugu, M.; Khristi, A.; Thareja, P.; Bagchi, D. Non-toxic, Printable Starch Hydrogel Composite with Surface Functionalized Silver Nanoparticles Having Wide-Spectrum Antimicrobial Property. BioNanoScience. 2024, 14, 4442–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, D. Radiation synthesis of PVP/alginate hydrogel containing nanosilver as wound dressing. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2012, 23, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, L.; Fiorati, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Pelacani, C.M.; Chiesa, R.; Farè, S.; De Nardo, L. Smart methylcellulose hydrogels for pH-triggered delivery of silver nanoparticles. Gels. 2022, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, C.; He, G.; Ban, L.; Huang, L.; Li, Z.; Gong, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P. Biomedical potential of ultrafine Ag nanoparticles coated on poly (gamma-glutamic acid) hydrogel with special reference to wound healing. Nanomaterials. 2018, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethi, G.U.; Unnikrishnan, B.S.; Sreekutty, J.; Archana, M.G.; Anupama, M.S.; Shiji, R.; Pillai, K.R.; Joseph, M.M.; Syama, H.P.; Sreelekha, T.T. Semi-interpenetrating nanosilver doped polysaccharide hydrogel scaffolds for cutaneous wound healing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020, 142, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, G.; Franklin, D.S.; Sudarsan, S.; Sakthivel, M.; Guhanathan, S. Noncytotoxic silver and gold nanocomposite hydrogels with enhanced antibacterial and wound healing applications. Polymer Engineering & Science. 2018, 58, 2133–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yan, Z.; Ji, S.; Xiao, S.; Gao, J. Metal nanoparticle hybrid hydrogels: the state-of-the-art of combining hard and soft materials to promote wound healing. Theranostics. 2024, 14, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, N.A.; Syed, A.; Kastrat, E.; Cheng, H.P. Antibacterial Silver Nanoparticle Containing Polydopamine Hydrogels That Enhance Re-Epithelization. Gels. 2024, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).