1. Introduction

With the increasing prevalence of mobile recording devices such as digital cameras, smartphones, wearable gadgets, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), users can now capture high-resolution videos across diverse environments. However, unlike professional videographers who utilize specialized stabilizers to ensure video stability, amateur users often face challenges when recording with handheld devices or vehicle-mounted recorders. Due to the lack of professional filming skills and stabilization equipment, their videos frequently exhibit noticeable jitter and poor stability. Consequently, video stabilization has emerged as a critical research focus, aiming to eliminate or mitigate undesired motion artifacts to generate stable, high-quality video outputs.

Figure 1 visually contrasts the differences between jittery and stabilized video sequences.

A video can be conceptualized as a temporal sequence of frames—static images captured at minimal time intervals and spatial proximity. Beyond the spatial information inherent in individual frames, videos encapsulate motion trajectories of foreground/background objects and dynamic variations in capturing devices (ego-motion). Interdisciplinary studies in psychology and neurophysiology [

1] have extensively investigated how the human visual system infers motion velocity and direction. Empirical evidence demonstrates that viewers perceive and infer motion attributes with high precision during video observation, mirroring real-world perceptual mechanisms. Notably, while stationary objects may escape attention, motion-triggered attention mechanisms enable rapid detection of dynamic changes. Critically, the visual system robustly discriminates between inherent object motion and artifacts induced by camera shake across most scenarios.

Despite the sophisticated processing capabilities of the human visual system, computationally addressing video jitter remains a formidable challenge. When capture devices operate under adverse external conditions, recorded videos often contain unintentional jitter that deviates from the photographer’s intent. The ubiquitous access to mobile devices enabling video acquisition anytime and anywhere has exacerbated the pervasiveness of instability issues. Beyond user-induced shaking, jitter artifacts frequently degrade visual quality in videos captured by vehicle-mounted surveillance systems [

2] and autonomous vehicle cameras [

3], particularly under dynamic operational environments.

Beyond focus inaccuracies, texture distortions, and hardware-induced artifacts (e.g., lens limitations), video acquisition introduces another instability artifact termed incapture distortion. Subjective studies confirm that video instability is perceptually salient to viewers, provoking significant visual discomfort—for instance, low-frequency vertical oscillations caused by walking motions during recording divert attention from content comprehension. Consequently, unstable camera motion severely degrades user experience. Although systematic analyses remain scarce regarding how unstable camera dynamics specifically impair computer vision tasks, empirical evidence establishes that excessive motion adversely impacts action recognition and object detection performance. This underscores the critical need for precise camera motion computation and correction. The primary objective of video stabilization is to compensate for undesired camera motion in jittery videos, thereby generating stabilized outputs with optimized perceptual quality.

Meanwhile, recent studies such as [

4,

5], optimizing motion compensation through spatio-temporal feature enhancement significantly improves the motion estimation accuracy of compressed video, and also provides more robust motion trajectories for the stabilization algorithm. [

6,

7] optimizes the segmentation boundary through foreground-background separation in dynamic scenes to enhance the robustness of the stabilized images and reduce the misjudgment due to occlusion, which provides a reference for the stabilized images in complex motion scenes.

Stabilized videos may retain intentional camera movement, provided such motion follows smooth and controlled trajectories. Thus, the primary objective of video stabilization is not to suppress all camera dynamics, but rather to selectively mitigate irregular, high-frequency jitter components while preserving intentional motion cues.

Contemporary video stabilization technologies are typically categorized into three primary classes: mechanical stabilization, optical stabilization, and digital stabilization.

Mechanical stabilization [

8] was a mainstream approach for early camera stabilization, relying on sensors to achieve stability. A typical mechanical stabilization method uses a gyroscope to detect the camera’s motion state and then employs specialized stabilizing equipment to physically adjust the camera’s position, counteracting the effects of shake, as shown in

Figure 2. Although mechanical stabilization technology excels at handling large-amplitude, high-frequency random vibrations and has been widely applied in vehicular, airborne, and marine platforms, it still has limitations. Purely mechanical stabilization is restricted in precision and susceptible to external environmental factors such as friction and air resistance. To improve stabilization accuracy, integrating mechanical stabilization with optical or digital stabilization techniques has been considered. However, the need for specialized equipment, device weight, and battery consumption associated with mechanical stabilization impose constraints on its application in handheld devices.

Optical stabilization [

9] is another important video stabilization method. It compensates for camera rotation and translation by real-time adjustment of internal optical components in the imaging device, such as mirrors, prisms, or optical wedges, to redirect the optical path or move the imaging sensor. This stabilization process is completed before image information is recorded by the sensor, with the internal component layout shown in

Figure 3. To improve stabilization accuracy, some optical stabilization systems incorporate gyroscopes to measure differences in motion velocity at different time points, effectively distinguishing between normal camera movements and unwanted shake. However, optical stabilization technology also has limitations. First, the high cost of optical components increases the overall system cost. Second, it is susceptible to lighting conditions, which can reduce accuracy and degrade the final stabilization effect. It is only suitable for applications with small random vibrations. Therefore, optical stabilization is more appropriate for scenarios with minimal random shake. Given the pursuit of higher stabilization performance and broader applicability, integrating optical stabilization with other stabilization techniques may represent a worth exploring direction.

Digital image stabilization are mainly implemented through software and mostly do not depend on specific hardware devices, such as [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Its fundamental principle involves accurately estimating undesired camera motion from video frames and compensating for such motion through appropriate geometric or optical transformations, as schematically illustrated in the stabilization pipeline of

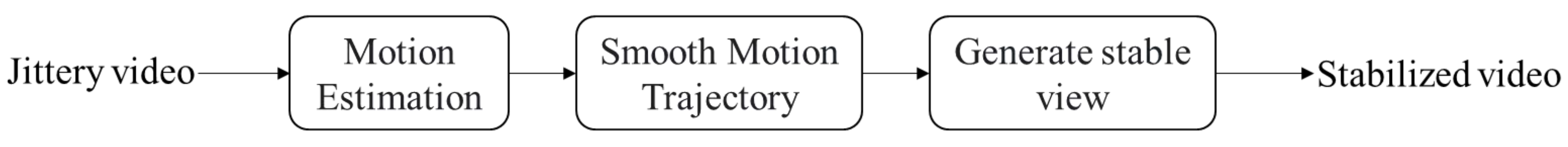

Figure 4. Although DVS exhibits slightly less advantageous processing speed compared to optical stabilization, it delivers superior performance in terms of stabilization quality and operational flexibility. A defining advantage of DVS lies in its unique capability: it represents the sole technology capable of post-hoc stabilization of pre-recorded videos, a critical feature for retrofitting stability to existing footage. With technological advancements, DVS has further diverged into two distinct paradigms: traditional model-driven methods and emerging deep learning-based approaches, expanding the research and application frontiers for video stabilization.

In the field of video stabilization, several representative surveys [

18,

19,

20,

21] have been conducted. However, the literature [

18] exclusively focuses on traditional methods and lacks perspectives on deep learning-based approaches. literature [

19] further discusses deep learning methods and quality assessment criteria, but does not provide a comprehensive investigation into deep learning methodologies and their performance comparisons. Although the literature [

20] comprehensively addresses both traditional and deep learning-based methods, it omits discussions on quality assessment metrics, datasets, and the results of the leading stabilization approaches. The literature [

21] provides a systematic overview of the evolution of stabilized image technology, but the integration and discussion of the data set is insufficient.Therefore, more in-depth research on video stabilization is essential for developing better future research guidelines. This paper presents a comprehensive investigation of both traditional and learning-based methods. In addition, we introduce and discuss quality assessment frameworks, benchmark datasets, and future challenges and prospects. The primary contributions of our work are as follows:

We provide a comprehensive survey of representative methodologies in video stabilization;

We introduce and discuss comprehensive assessment metrics for video stabilization quality;

We summarize currently widely used benchmark datasets;

We further discuss the challenges and future directions of video stabilization tasks.

In this paper,

Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art development and representative methodologies in video stabilization.

Section 3 then elaborates on the assessment methodologies for video stabilization quality in detail. Additionally,

Section 4 introduces public datasets and summarizes the state-of-the-art performance. Furthermore,

Section 5 discusses the challenges and future directions faced by video stabilization. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the work.

2. Advances in Video Stabilization

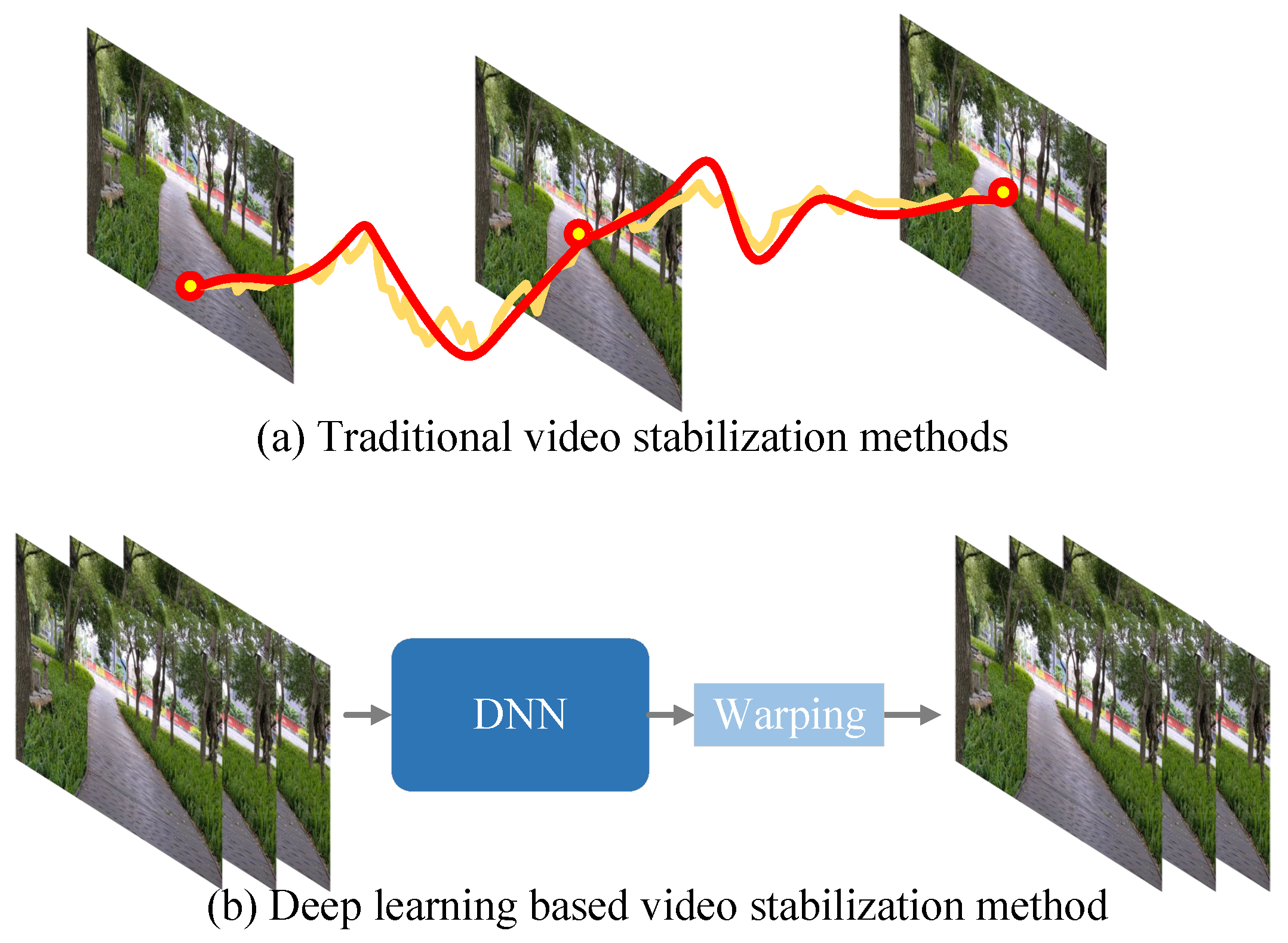

Currently, in the research field of digital video stabilization, it is mainly divided into two approaches: traditional methods and those based on deep learning. Traditional methods rely on manually and meticulously designed and extracted features, as shown in

Figure 5a. This process has a high demand for professional knowledge and is complex to operate. In contrast, video stabilization based on deep learning does not directly calculate and display the motion trajectory of the camera. Instead, it skillfully uses a supervised learning model for stabilization processing, as illustrated in

Figure 5b. It is worth noting that the video stabilization methods based on deep learning have demonstrated significant advantages in terms of performance, such as [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. They are capable of extracting high-dimensional features, getting rid of the dependence on manual feature extraction and matching, thus endowing a stronger video stabilization ability. In this paper, in response to the current development of video stabilization, the digital video stabilization is introduced by classifying it according to traditional and deep learning-based video stabilization algorithms. The purpose of this paper is to comprehensively sort out the current video stabilization and systematically expound and introduce the digital video stabilization based on the two categories of traditional methods and deep learning.

2.1. Algorithms of Traditional Digital Video Stabilization

In 2011, Grundmann et al. proposed the L1 optimization method [

29]. This method aims to obtain a stable video that meets the visual requirements by generating a smooth camera path that follows the laws of cinematography. To achieve this goal, they employed a linear programming algorithm. By minimizing the first-order, second-order, and third-order derivatives and simultaneously considering various constraints in the camera path, they effectively smoothed the camera path. It is worth noting that the L1 optimization method tends to generate some smooth paths with zero derivatives. This characteristic enables it to eliminate the undesired low-frequency jitter of the camera, further enhancing the stability of the video.

In 2021, Bradley et al. [

30] improved the L1 optimization method. By introducing the homography transformation, they significantly enhanced the precision of the algorithm. This method is deeply rooted in Lie theory and operates within the logarithmic homography space to maintain the linearity of the processing, thus enabling efficient convex optimization. In order to enhance the approximation between the stabilized path and the original path, this method employs the L2 norm. Meanwhile, the constraints in the optimization process ensure that only valid pixels are included in the cropped frames, and the field of view is retained according to the approximate values of the area and side length. In addition, this method can effectively address the distortion problem through specific constraints and optimization objectives. A sliding window strategy is used to process videos of any length. When dealing with videos of arbitrary length, Bradley et al. adopted the sliding window strategy, demonstrating extremely high flexibility. To properly handle the problem of discontinuity, they further introduced the third-order Markov property, which means that the first three frames of the current window will maintain the solutions generated within the previous window unchanged. This innovative technical approach has significantly improved the coherence and stability of video stabilization processing.

In 2013, Liu et al. [

31] proposed a method named Bundled, which achieves video stabilization by calculating two minimization operations to obtain the global optimal path. Firstly, in order to prevent excessive cropping and geometric distortion, this method endeavors to maintain the approximation between the original path and the optimal stabilized path. Secondly, it ensures the stability of motion by minimizing the L2 norm of the internal path difference within the neighborhood. It is worth noting that this method calculates the bundled path for each grid cell, aiming to effectively handle parallax and rolling shutter effects by deeply exploring local transformations and shape preservation constraints, thereby further enhancing the stabilization effect.

In 2014, Liu et al. [

32] proposed a video stabilization method named SteadyFlow. The core idea of this method is to achieve video stabilization by smoothing the optical flow. In specific implementation, it skillfully combines the traditional optical flow and the global matrix for initialization, thus laying the foundation for video stabilization. In order to identify discontinuous motion more accurately, this method also divides the motion vectors of a given frame into inliers and outliers based on spatio-temporal analysis. This division strategy enables the optical flow to more easily calculate the global path, and thus achieves a more efficient video stabilization effect.

In 2016, Liu et al. [

33] further improved the SteadyFlow method and proposed a new optimization scheme named MeshFlow. This method has remarkable online stabilization performance and only produces a one-frame delay, which greatly improves the real-time processing efficiency. During the processing, MeshFlow uses a dynamic buffer to store the processed frames. In the initial stage, the number of frames in the buffer is small, but as the processing progresses, the number gradually increases and stabilizes at a fixed size, thus forming a processing mechanism of a sliding window. Whenever a new frame enters the buffer, MeshFlow will calculate the best path for all the frames in the buffer, and additionally introduce an additional term to maintain the approximation between the current optimal path and the previous optimal path. This design not only ensures the continuity of the path but also effectively reduces the instability caused by path changes. Finally, MeshFlow only uses the calculated value of the last frame to warp the incoming frame, thus achieving an efficient and accurate video stabilization effect.

In 2015, Zhang et al. [

34] proposed a video stabilization method. This method collaboratively completes the tasks of removing excessive jitter and mesh warping through a set of specific trajectories, thus achieving faster stabilization processing. In order to reduce the geometric distortion in the stabilized video, this method carefully encodes the two key steps of jitter removal and mesh warping based on the positions of the mesh vertices in a single global optimization. This global optimization method not only improves the processing speed but also effectively reduces the geometric distortion during the video stabilization process, further enhancing the video quality.

In 2017, Zhang et al. [

35] proposed a video stabilization method conducted in the geometric transformation space. By using the Riemannian Metric, they ingeniously transformed the Geodesics in the Lie Group into an optimized path, thus providing new ideas for video stabilization. It is worth noting that this method adopts a closed-form expression in a specific space to accurately solve the geodesics, which enables the smoothing of the camera trajectory to be easily achieved through geometric interpolation. According to the authors, by applying the geodesic solution in the rigid transformation space, the running speed of this method has been significantly improved, providing a more efficient and convenient means for the practical application of video stabilization.

In 2018, Wu et al. [

36] proposed a novel video stabilization method. They believed that the local window in time contains stationary, constant velocity, or accelerated motion. Different from previous methods, the optimization method of Wu et al. can specifically deal with each type of jitter. The first contribution of this method lies in the fidelity of motion perception. Previously, most methods used a Gaussian kernel function as the temporal weight during the optimization process. However, the isotropic property of the Gaussian kernel function in time makes it perform poorly in accelerated motion. To solve this problem, Wu et al. innovatively introduced the Motion Steering Kernel to replace the Gaussian kernel function and used an adaptive window size to achieve better performance in fast motion. The second contribution of this method is the proposal of the local Low-Rank regularization term, which can effectively improve the model’s robustness to different motion patterns and further enhance the effect of video stabilization.

Currently, most video stabilization methods adopt the strategy of removing some outliers when dealing with feature trajectories, but this practice may mistakenly remove the features in the foreground as well. To solve this problem, Zhao, Ling et al. [

37] proposed a new method. Based on the similarity transformation between and within frames, they imposed two constraints on the motion of the foreground trajectories. According to these trajectories, they further calculated a Delaunay triangular mesh. In order to determine the unwanted motion, they achieved it by solving an optimization problem with three constraints: First, the stabilized path should be smooth, which is to ensure the coherence and comfort of video viewing. Second, for each frame, each stabilized triangle must be geometrically similar to the original triangle, and this constraint helps to maintain the geometric structure of the video from being damaged. Finally, for each frame, the transformation between a given stabilized triangle and its adjacent triangles must be similar to the transformation of the same unstable triangle and its adjacent triangles, and this constraint ensures the motion consistency between video frames. Through these elaborate constraints, their method can more effectively retain the foreground features while maintaining the stability of the video.

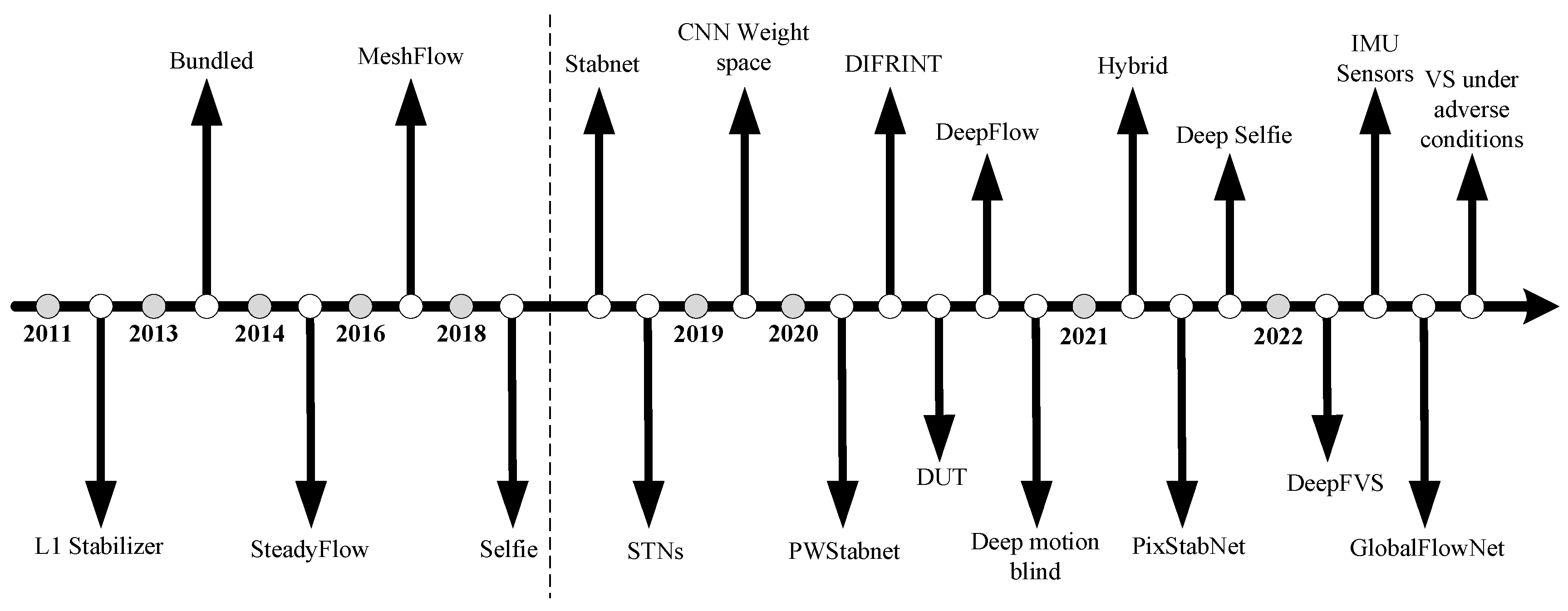

Since deep learning technology entered the field of video stabilization in 2018, digital video stabilization methods have shown a trend of diversification. Compared with traditional methods, these methods, while dealing with video jitter, adopt different training strategies to reduce the possible distortion and cropping problems during the stabilization process. More importantly, the speed advantage brought by deep learning makes online video stabilization possible.

Figure 6 shows various digital video stabilization methods mentioned in this paper in chronological order. The part before the dotted line represents traditional video stabilization technologies, while the part after the dotted line demonstrates new video stabilization methods based on deep learning.

2.2. Video Stabilization Methods Based on Deep Learning

Since 2018, deep learning technology has been increasingly widely applied in the field of video stabilization, such as [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] injecting new vitality into digital video stabilization methods. By adopting diverse training methods, these methods can not only effectively deal with video jitter but also reduce distortion and cropping phenomena during the stabilization process. At the same time, the high-speed processing ability of deep learning also provides strong support for online video stabilization. The extensive application of deep learning has greatly enriched the technical means of video stabilization. In addition to the basic jitter processing task, different methods also show unique advantages during the video processing. According to the type of motion information utilized in motion estimation, this paper classifies the video stabilization algorithms based on deep learning into three major categories: 2D, 3D, and the 2.5D method that uses 2D motion information to estimate three-dimensional motion for handling parallax. This classification method helps to more systematically understand and compare the performance and characteristics of various video stabilization algorithms.

2D methods primarily rely on two-dimensional motion calculations, and their processes may also involve other video processing tasks such as compression, denoising, interpolation, and segmentation. In contrast, 3D methods require reconstructing a 3D scene model and precisely modeling camera poses to compute smooth virtual camera trajectories in 3D space. To determine the camera’s six degrees of freedom (6DoF) pose, researchers have employed various techniques, including projective 3D reconstruction [

45], camera depth estimation [

46], structure from motion (SFM) [

47], and light-field analysis [

48].

While 3D methods offer significant advantages in handling parallax and generating high-quality stabilized results, they typically demand high computational costs [

49] or specific hardware support. By comparison, 2D stabilization methods are widely adopted in practice due to their robustness and lower computational overhead. Additionally, 3D methods may fail when large foreground objects are present [

50], further limiting their application scenarios, whereas 2D methods exhibit better adaptability across a broader range of scenarios. However, when successfully implemented, 3D methods often yield stabilized results of superior quality.

To integrate the strengths of 2D and 3D approaches while mitigating their limitations, researchers have proposed 2.5D methods. These hybrid methods fuse features from 2D and 3D techniques, aiming to enhance stabilization quality while reducing computational requirements or hardware dependencies. As such, 2.5D methods hold promising development prospects and substantial application potential in the field of digital video stabilization.

2.2.1. 2D Video Stabilization

In 2018, Wang et al. [

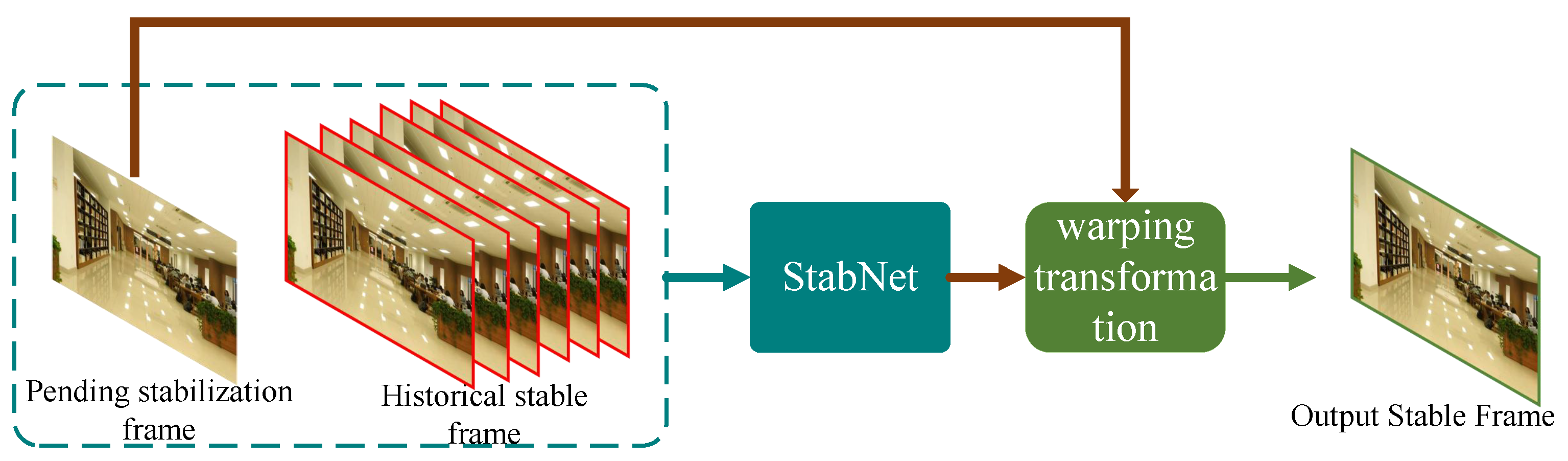

51] first proposed a video stabilization solution based on a deep neural network, named StabNet. Previously, the application of deep learning in the field of video stabilization had been limited, mainly due to the lack of corresponding datasets. In order to train this network, Wang et al. ingeniously collected a dataset of synchronized stable and unstable video pairs named Deepstab through specially designed handheld devices. This dataset includes 60 pairs of synchronized videos, with each pair of videos lasting approximately 30 seconds and recorded at a frame rate of 30 FPS.

Traditional digital image stabilization methods mostly use offline algorithms to smooth the overall camera path through feature matching techniques. Huang et al. [

52] systematically summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of classical algorithms in feature matching, and provides theoretical support for the optimization of feature trajectories in image stabilization. In contrast, StabNet is committed to achieving low-latency and real-time camera path smoothing. It neither explicitly presents the camera path nor relies on the information of future frames. Instead, it gradually learns a set of mesh transformations for each input frame to be stabilized from the historical sequence of stabilized frames, and then obtains the stabilized frame output through the warping operation. The algorithm flow is shown in

Figure 7.

Compared with traditional offline video stabilization, without relying on future frames, StabNet has increased its running speed by nearly 10 times. At the same time, when dealing with low-quality videos, such as night scenes, videos with watermarks, blurry and noisy videos, etc., StabNet has demonstrated excellent performance. However, StabNet is slightly deficient in the stability score, and there may be unnatural inter-frame swinging and distortion phenomena. This is mainly due to the limitations of it as an online method, that is, it only relies on the information of historical frames and lacks a comprehensive grasp of the complete camera path. In addition, the effect of StabNet is also limited by its generalization ability, because it requires a large number of video pairs containing different types of motion for training. Unfortunately, since the types of videos covered in the DeepStab dataset are relatively limited, the methods using this dataset are often affected by insufficient generalization ability.

Xu et al. [

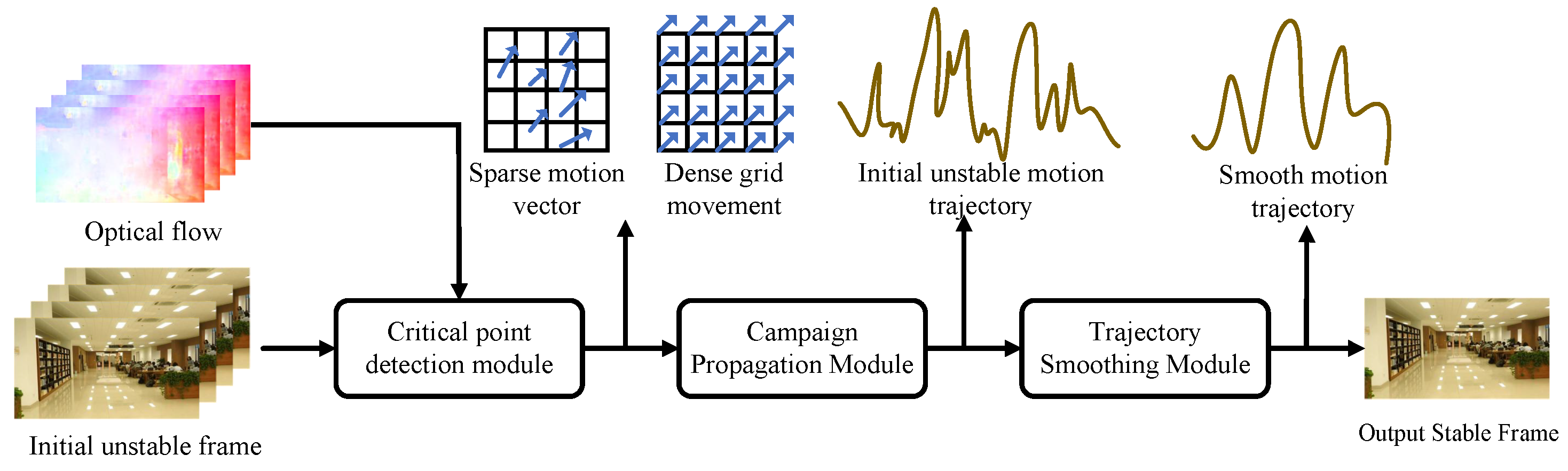

53] proposed an unsupervised motion trajectory stabilization framework named DUT. Traditional video stabilization methods mainly rely on human-controlled trajectory smoothing. However, in scenes with occlusions and without textures, the performance of manually annotated features is often unstable. In order to improve the controllability and robustness of video stabilization, DUT made the first attempt to use the unsupervised deep learning method to explicitly estimate and smooth the trajectory to achieve video stabilization. This framework is composed of a keypoint detector and a motion estimator based on a deep neural network (DNN), which are used to generate grid-based trajectories. At the same time, it also employs a trajectory smoother based on a convolutional neural network (CNN) to stabilize the video. During the unsupervised training process, DUT makes full use of the characteristic of motion continuity, as well as the consistency of the keypoints and grid vertices before and after stabilization.

As shown in

Figure 8, the DUT framework mainly consists of three core modules: the Keypoint Detection module (KD), the Motion Propagation module (MP), and the Trajectory Smoothing module (TS). Firstly, the KD module uses the detector of RFNet [

54] (used for feature point analysis) and the optical flow of PWCNet to calculate the motion vectors. Then, the MP module propagates the motion of sparse keypoints to the dense grid vertices of each frame and obtains their motion trajectories through temporal correlation. Finally, the TS module smooths these trajectories. By optimizing the estimated motion trajectories while maintaining the consistency of the keypoints and vertices before and after stabilization, this stabilizer forms an unsupervised learning scheme.

DUT performs excellently in dealing with challenging scenes with multi-plane motion. Compared with other traditional stabilizers, DUT benefits from its deep learning-based keypoint detector and has more advantages in handling scenes of fast rotation categories such as blurriness and large motions. It outperforms other methods both in terms of distortion and stability metrics. However, in the case of texture absence, DUT may lead to relatively large distortion.

Yu and Ramamoorthi [

55] proposed a neural network named DeepFlow. This network innovatively adopts the optical flow method for motion analysis and directly infers the pixel-level warping used for video stabilization from the optical flow field of the input video. The DeepFlow method not only uses optical flow for motion restoration but also achieves smoothing through the warping field. In addition, this method applies the PCA optical flow [

56] technology to the field of video stabilization, thus significantly improving the processing robustness in complex scenes such as moving objects, occlusions, and inaccurate optical flow. This stabilization strategy that integrates optical flow analysis and learning has brought new breakthroughs to video stabilization.

Choi and Kweon [

57] proposed a full-frame video stabilization method named DIFRINT. This method performs smoothing processing through frame interpolation technology to achieve a stable video output. DIFRINT is a video stabilization method based on deep learning. Its uniqueness lies in its ability to generate stable video frames without cropping and maintain a low distortion rate. This method uses frame interpolation technology to generate interpolations between frames, effectively reducing the inter-frame jitter. Through iterative application, the stabilization effect can be further improved. This is the first deep learning method that proposes full-frame video stabilization.

Given an unstable input video, DIFRINT ingeniously uses frame interpolation as a means of stabilization. Essentially, it interpolates iteratively between consecutive frames while keeping the stable frames at the boundaries of the interpolated frames, thus achieving a full-frame output. This unsupervised deep learning framework does not require paired real stable videos, making the training process more flexible. By using the frame interpolation method to stabilize frames, DIFRINT successfully avoids the problem of introducing cropping.

From the perspective of interpolation, the interpolated frames generated by the DIFRINT deep framework represent the frames captured between two consecutive frames, that is, the intermediate frames in a temporal sense. The sequential generation of such intermediate frames effectively reduces the spatial jitter between adjacent frames. Intuitively, frame interpolation can be regarded as the linear interpolation (low-pass filter) of the spatial data sequence in the time domain. When linear interpolation is applied iteratively multiple times, the stabilization effect will be significantly enhanced. For the spatial data sequence (i.e., the frame sequence), DIFRINT estimates the precise intermediate points for almost every pixel through interpolation and generates intermediate frames, thus achieving high-precision video stabilization. Another advantage of DIFRINT is that users can adjust the number of iterations and parameters according to their preferences. Some users may prefer to retain a certain degree of instability for certain types of videos. Instead of applying a one-size-fits-all approach to each video, this can provide users with some freedom of operation. However, it still has certain limitations. In videos with severe jitter, this method may introduce blurring at the image boundaries and may lead to serious distortion during the iterative process.

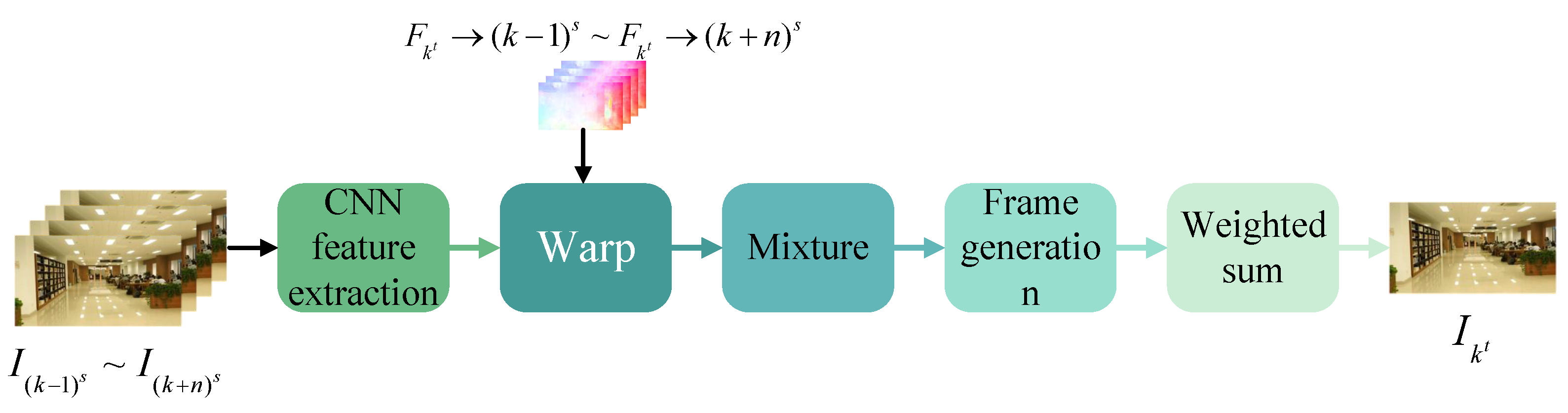

Liu et al. [

58] proposed a frame synthesis algorithm named Hybrid, which is committed to achieving full-frame video stabilization and effectively solves the problems of obvious distortion and large-scale cropping of frame boundaries that may be caused by existing video stabilization methods. The Hybrid algorithm is composed of a feature extractor, a warping layer, a fusion function frame generator, and a final weighted summation step, thus generating a stable video output. The algorithm flow is shown in

Figure 9. The core idea of this method is to fuse the information from multiple adjacent frames in a robust way. It first estimates the dense warping field from the adjacent frames, and then synthesizes the stable frames by fusing these warped contents. The main innovation of Hybrid lies in its deep learning-based hybrid spatial fusion technology, which can mitigate the impacts caused by inaccurate optical flow and fast-moving objects, and thus reduce the generation of artifacts. Instead of directly using RGB color frames, this method uses a trained CNN to extract features for each frame to represent the local appearance, and fuses multiple aligned feature maps to decode and render the final color frame through a neural network.

Hybrid adopts a hybrid fusion mechanism that combines feature-level and image-level fusion to reduce sensitivity to inaccurate optical flow. By learning to predict the spatially varying hybrid weights, Hybrid is able to remove blurriness and generate videos with low distortion. In addition, in order to transfer the remaining high-frequency details to the stabilized frames and re-render them to further improve the visual quality of the synthesis results, this method also employs a unique processing approach. To minimize the blank areas in all adjacent frames, Hybrid also proposes a path adjustment method, which aims to balance the smoothness of camera motion and the maximum reduction of frame cropping.

The stabilized videos generated by Hybrid significantly reduce artifacts and distortion. This method shows stronger robustness when the optical flow prediction is inaccurate, but it may produce overly blurred outputs. Nevertheless, Hybrid can still generate full-frame stabilized videos with fewer visual artifacts and can be combined with existing optical flow smoothing methods to achieve further stabilization effects. However, the Hybrid method performs poorly in dealing with the rolling shutter effect and may be limited in complex situations such as lighting changes, occlusions, and foreground/background motion. In addition, the running speed of this method is relatively slow (10 FPS), making it more suitable for offline applications.

2.2.2. 3D Video Stabilization

Lee and Tseng [

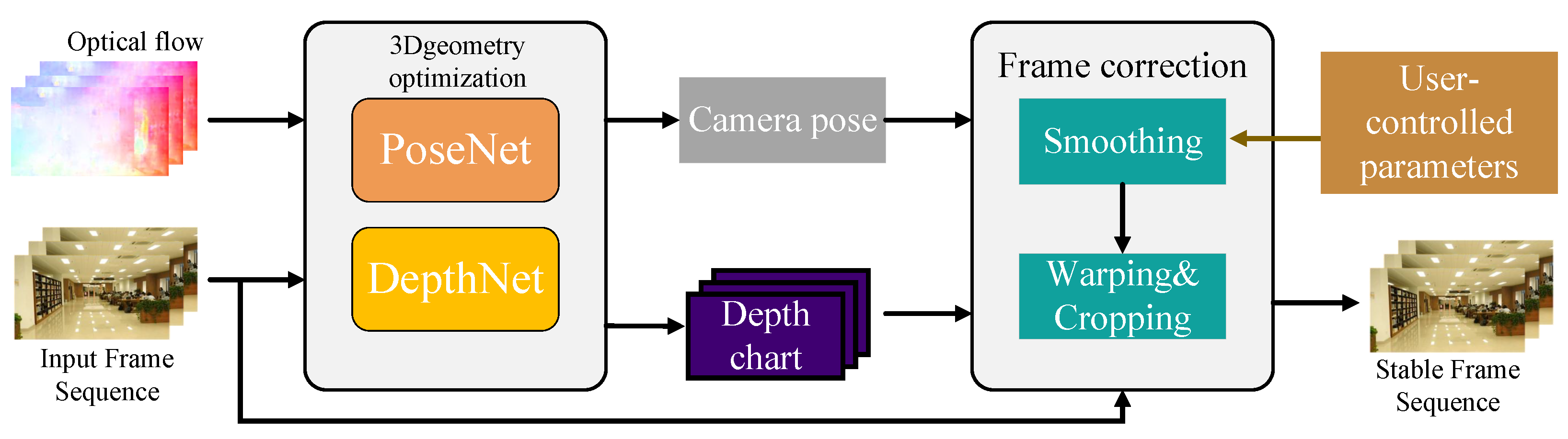

59] proposed a deep learning-based 3D video stabilization method named Deep3D, which innovatively uses 3D information to enhance video stability. Compared with previous 2D methods, when dealing with scenes with complex scene depths, Deep3D can significantly reduce the generation of artifacts. It adopts a self-supervised learning framework to simultaneously learn the depth and camera pose in the original video. It is worth noting that Deep3D does not require pre-trained data but directly stabilizes the input video through 3D reconstruction. In the testing phase, the convolutional neural network (CNN) simultaneously learns the scene depth and 3D camera motion of the input video.

The implementation of this method is divided into two stages, as shown in

Figure 10. The first stage is the 3D geometric optimization stage. In this stage, PoseNet and DepthNet are used to estimate the 3D camera trajectory and dense scene depth of the input RGB frame sequence respectively. In addition, the input frame sequence and its corresponding optical flow are used as guiding signals for learning the 3D scene. The second stage is the frame correction stage. This stage takes the estimated camera trajectory and scene depth as inputs, and generates a stabilized video through view synthesis of the smoothed trajectory. Users can adjust the parameters of the smoothing filter during this process to obtain different degrees of stabilization effects. Subsequently, through warping and cropping operations, a stabilized video output is finally produced.

The DepthNet and PoseNet in the geometric optimization framework of Deep3D can estimate the dense scene depth and camera pose trajectory according to the segments of the input sequence. Using the loss term of 3D projection measurement, the parameters of these networks are updated through backpropagation during the test time.

Deep3D performs excellently in dealing with parallax and severe camera jitter, and is able to achieve both high stability and low distortion in the output of stabilized videos. However, this method still needs to address some issues, such as motion blur, rolling shutter effect, and excessive cropping, etc., to further improve the quality of video stabilization.

Chen Li et al. [

60] proposed an innovative online video stabilization method, which uses the Euler angle and acceleration data provided by the gyroscope and accelerometer in the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) to enhance video stability. In order to more comprehensively verify the effectiveness of their method, Chen Li et al. also constructed a brand-new dataset, which covers seven typical shooting scenarios, including walking, going up and down stairs, panning, zooming, fast shaking, running, and the stationary state. These videos are all recorded at a resolution of 1080p and a frame rate of 30FPS, and each video is approximately 30 seconds long. In order to achieve more refined optimization, they adopted the improved Cubic Spline Method to generate pseudo-ground-truth stabilized videos as references.

RStab [

61] breaks through the traditional limitations through a 3D multi-frame fusion body rendering framework - its core stable rendering (SR) module fuses multi-frame features and color information in 3D space, combined with deep a priori sampling of the adaptive ray range (ARR) module and optical flow constraints of color correction (CC), preserving the full field of view (FOV) while significantly improving the projection accuracy of dynamic regions, realizing full-frame stabilized video generation.

In terms of trajectory optimization, Chen Li et al. adopted two sub-networks. The first sub-network focuses on detecting the motion scene and adaptively selects the features that conform to a specific scene by generating an attention mask. This method significantly improves the flexibility and robustness of the model when dealing with complex motion scenes, enabling the model to achieve a prediction accuracy of 99.9% in all seven scenes. The second sub-network, under the supervision of the mask, uses the Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM) to predict a smooth camera path based on the real unstable trajectory.

Although this method has a slightly lower score in terms of stability and may occasionally cause visual distortion due to the lack of future information, its output results are more reliable. It has produced robust results with less distortion in various scenes and achieved a more balanced performance in different types of videos. It is particularly worth mentioning that in the four scenes of walking, stairs, zooming, and static, even with only a 3-frame delay, this method has achieved impressive results.

2.2.3. 2.5D Video Stabilization

Given the complementary strengths of 2D and 3D methods, 2.5D methods do not explicitly reconstruct the 3D structure of the camera path, but instead use some spatial relationships as path smoothing constraints.

Goldstein and Fattal [

62] utilize an “epipolar geometry” technique for intermediate scene modeling called projective reconstruction. This model explains the internal geometric relationships between general uncalibrated camera views and avoids 3D reconstruction. Experiments show that this method is suitable for any scene with variable depth.

Matthias et al. [

63] proposed the idea of hybrid homology, fitted to matching after feature extraction and RANSAC purification to obtain glo bal motion parameters.

Wang et al. [

64]represented each trajectory as a Bessel curve and maintained the spatial relationship between trajectories by preserving the original offsets of neighboring curves. In this approach, video stabilization is defined as a spatio-temporal optimization problem that finds smooth features while avoiding visual distortion.

Zhao and Ling [

65] proposed a video stabilization network named PWStableNet, which adopts a pixel-by-pixel calculation method. Different from most previous methods that calculate a global homography matrix or multiple homography matrices based on a fixed grid to warp the jittery frames to a stable view, PWStableNet introduces a pixel-level warping map, allowing each pixel to be warped independently, thus more accurately handling the parallax problem caused by depth changes. This is also the first pixel-level video stabilization algorithm based on deep learning.

PWStableNet adopts a multi-level cascaded encoder-decoder structure and innovatively introduces inter-stage connections. This connection fuses the feature map of the previous stage with the corresponding feature map of the later stage, enabling the later stage to learn the residuals from the features of the previous stage. This cascaded structure helps to generate a more accurate warping map in the later stage.

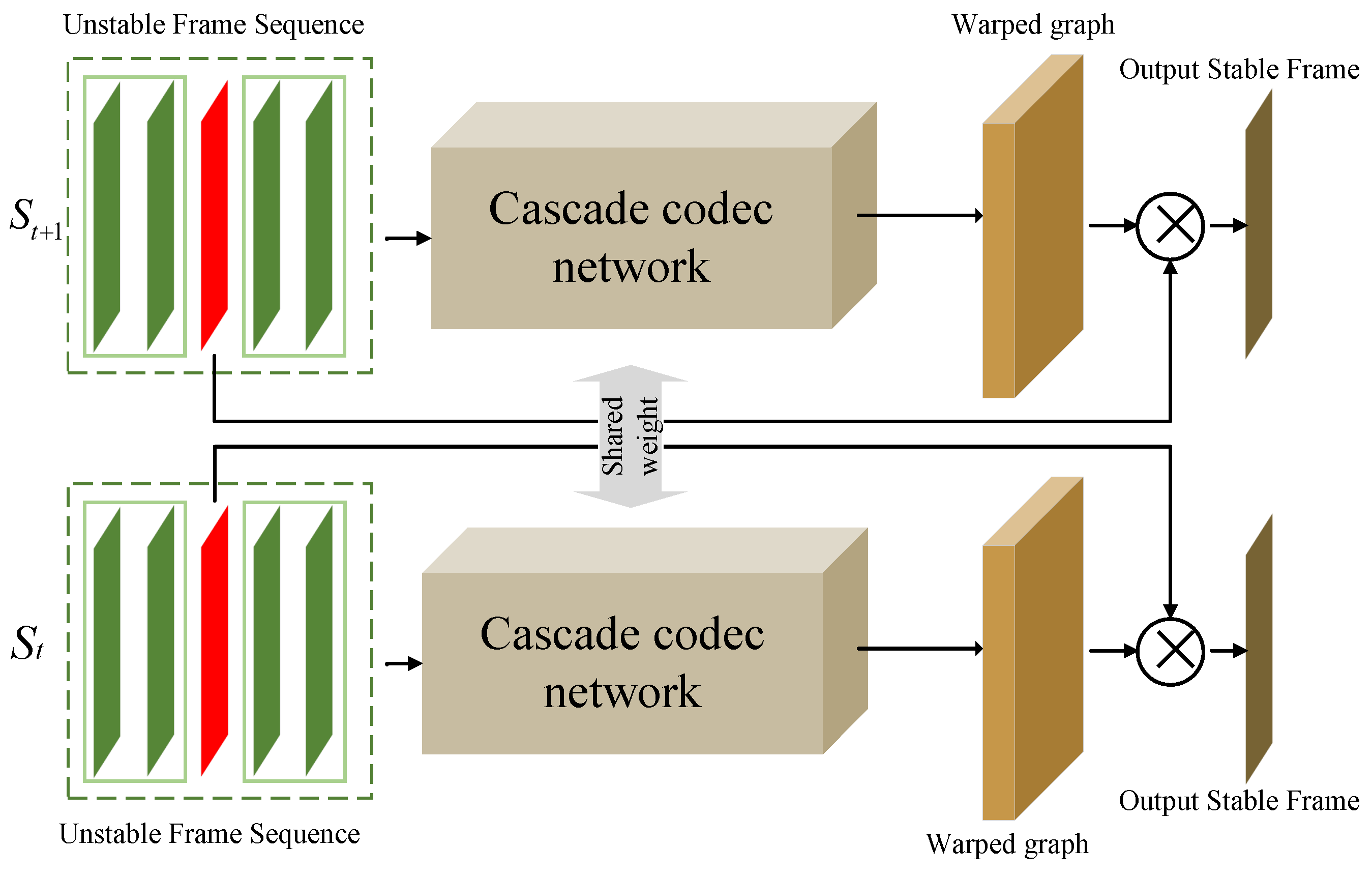

As shown in

Figure 11, in order to stabilize a certain frame, PWStableNet receives a group of adjacent frames as input and estimates two warping maps: a horizontal warping map and a vertical warping map. For each pixel, the corresponding values in these two warping maps indicate the new position of the pixel in the stable view after it is transformed from its original position. PWStableNet is composed of three-level cascaded encoder-decoder modules, in which the two branches of the siamese network share parameters. This siamese structure ensures the temporal consistency between consecutive stabilized frames, thus significantly improving the stability of the generated video.

By applying the pixel-level warping mapping, PWStableNet can accurately convert the unstable frames into stable frames. This method is more accurate than simply estimating a global affine transformation or a set of transformations, especially in videos with parallax and crowds. This is because such videos usually contain more parallax or discontinuous depth changes, which cannot be described by a few affine matrices. In addition, PWStableNet also shows good robustness to low-quality videos such as those with noise and motion blur. However, when facing complex scenes such as large parallax and fast movement, its effect may be affected to some extent.

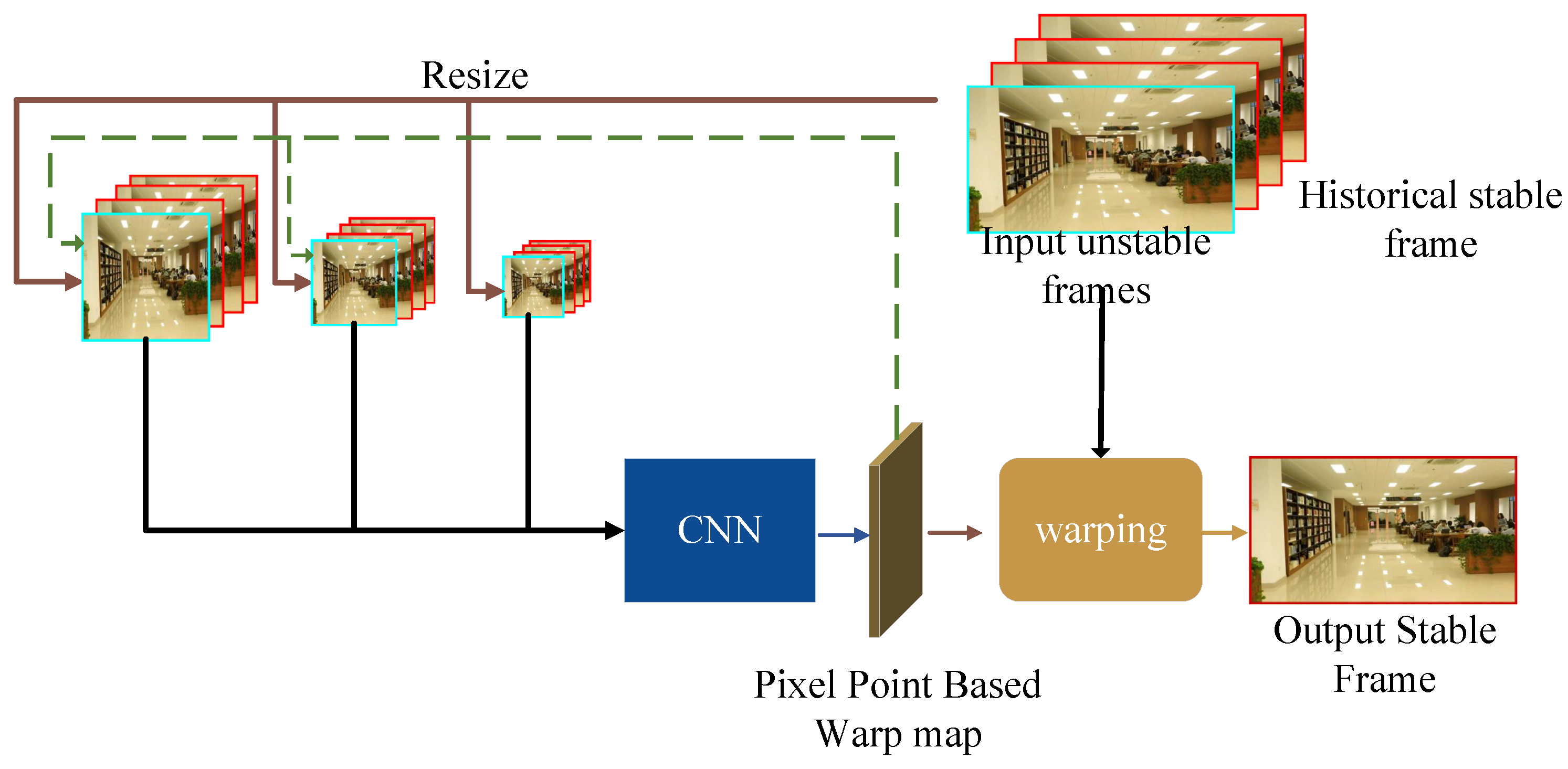

Chen and Tseng et al. [

66] proposed a multi-scale convolutional neural network named PixStabNet for video stabilization, which can achieve real-time video stabilization without using future frames. In order to enhance the robustness of the network, the researchers also adopted a two-stage training scheme.

Some previous methods, such as StabNet, did not consider depth changes. It used historical real stabilized frames as inputs during training and historical output stabilized frames during testing, which may lead to serious distortion and warping in the output video. Although PWStableNet takes depth changes into account by generating pixel-based warping maps, since it requires 15 future frames as network inputs, it will introduce a delay of at least 15 frames. PixStabNet solves these problems by proposing a multi-scale CNN network, which can directly predict the transformation of each input.

As shown in

Figure 12, the structural framework of PixStabNet adopts a multi-scale approach, which can be regarded as a coarse-to-fine optimization strategy. The network uses an encoder-decoder architecture to estimate the pixel-based warping map to stabilize the frames and utilizes a two-stage training scheme to further enhance the robustness of the network. During the processing, PixStabNet starts from the coarsest level first to estimate a rough transformation. In order to transfer the output of the coarser level to the finer level, the network uses the warping map predicted by the coarser level to pre-stabilize the unstable frames at the finer level, and then the network further optimizes the frames at the finer level. Finally, the final warping map is generated by combining the warping maps of each level.

The experimental results show that compared with StabNet, PixStabNet can produce more stable results with less distortion. Although the video output by PWStableNet has less distortion, its stability is poor and there is obvious jitter. It is worth mentioning that PixStabNet is currently the fastest online method, with a running speed of 54.6 FPS and without using any future frames. However, while pursuing stability, it may lead to large cropping in the output results.

Yu and Ramamoorthi [

67] proposed a robust video stabilization method, which innovatively models the inter-frame appearance changes directly as a dense optical flow field between consecutive frames. Compared with traditional technologies that rely on complex motion models, this method adopts a video stabilization formula based on the first principle, although this introduces a large-scale non-convex problem. To solve this problem, they cleverly transfer the problem to the parameter domain of the convolutional neural network (CNN). It is worth noting that this method not only takes advantage of the standard advantages of CNN in gradient optimization, but also uses CNN purely as an optimizer, rather than just extracting features from the data for learning. The uniqueness of this method lies in that it trains the CNN from scratch for each input case and deliberately overfits the CNN parameters to achieve the best video stabilization effect on a specific input. By transforming the transformation directly targeting the image pixels into a problem in the CNN parameter domain, this method provides a new feasible way for video stabilization.

The process of this method includes four main steps: (1) Pre-stabilize the video using a basic 2D affine transformation; (2) Utilize the optical flow between consecutive frames in the pre-stabilized video to transform the video stabilization problem into a problem of minimizing the motion between the corresponding pixels; (3) Use the CNN as an optimizer to solve the problems of the 2D affine transformation and the warping field of each frame; (4) Warp and crop the video frames to produce stable results.

In a recent study, to address the model generalization challenge, Ali et al. [

68] proposed a test-time adaptive strategy to optimize pixel-level synthesis parameters through single-step fine-tuning combined with meta-learning to significantly improve the stability of complex motion scenes. A Framework for Deep Camera Path Optimization [

69] achieves real-time image stabilization with single-frame-level delay within a sliding window with performance comparable to offline methods via a motion smoothing attention (EMSA) module with a hybrid loss function. Literature [

70] proposes a self-similarity two-stage denoising scheme combined with temporal trajectory pre-filtering to enhance the quality of input frames; meanwhile, Zhang et al. [

71] utilizes IMU-assisted grayscale pixel matching across frames to significantly enhance the temporal consistency of the white balance, and to provide more robust preprocessing support for the image stabilization algorithm.

For videos with large occlusions, the 2D methods based on feature trajectories often fail due to the difficulty of obtaining long feature trajectories and produce artifacts in the video. At the same time, the Structure from Motion (SFM) method is usually not suitable for dynamic scenes, and the 3D method also cannot produce satisfactory results. In contrast, the optical flow-based method shows stronger robustness when dealing with larger foreground occlusions. However, the processing speed of this method needs to be improved.

3. Assessment Metrics for Video Stabilization Algorithms

In the technology of video stabilization, the irregular jitter of the camera can cause visual discomfort. However, at the same time, the processing of video stabilization may introduce artifacts, distortion, and cropping, all of which will lead to the impairment of the visual quality of the video output by the algorithm. Therefore, the assessment of video stabilization quality has become a key indicator for measuring the advantages, disadvantages, and practicality of video stabilization methods.

Although there have been many previous studies [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] involving the assessment of video stabilization performance, up to now, there has not been a clear and unified assessment standard for video stabilization quality. This section will mainly review the development history of video stabilization quality assessment. Similar to video quality assessment, the current mainstream assessment of video stabilization quality is also divided into two major categories: subjective assessment and objective assessment.

3.1. Subjective Quality Assessment

Subjective quality assessment is an assessment method based on the human subjective visual system. In this method, the stability of a video is usually evaluated through the inspection of the human visual system and user surveys. Among them, the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) [

77] is a widely adopted subjective assessment method for measuring the quality of video stabilization at present. This method was first established by Suan et al. on a statistical basis and has been applied in the medical field. In order to ensure that the results of the subjective assessment of the video have statistical significance, a certain number of observers must be involved, so that the results of the subjective assessment can truly reflect the stabilization effect of the video. However, the drawback of the MOS assessment method is that it cannot be represented by mathematical modeling and is time-consuming, so it is not suitable for the stability assessment of large datasets.

The Differential Mean Opinion Score (DMOS) is a derivative index based on the MOS score, which reflects the difference in assessment scores between the distortion-free image and the distorted image by the human visual system. The smaller the DMOS value, the higher the image quality.

In addition, a MOS-based user survey method was introduced in [

78], which measures the subjective preferences of users through combined comparisons between different methods. Specifically, the investigator will show multiple videos to the observers and ask the observers to select the best-performing video among them according to some predefined indicators.

In the assessment of video stabilization quality, user surveys are often used as a supplementary means to objective assessment to assess the stability of the stabilized video and whether the distortion and blurriness have an impact on the user’s viewing experience. However, the drawback of user surveys is that they are too time-consuming and it is difficult to accurately describe them through mathematical modeling. Nevertheless, in the current situation where there is a lack of a unified objective quality assessment standard, the existence of subjective quality assessment is still very necessary, as it provides us with an intuitive and effective method for evaluating the quality of video stabilization.

3.2. Objective Quality Assessment

The objective assessment method is to conduct a standardized assessment of the video stabilization algorithm by constructing a mathematical model of indicators that can reflect the quality of video stabilization. According to whether they rely on a reference object or not, these methods can be further divided into full-reference quality assessment methods and no-reference quality assessment methods. The core of the full-reference quality assessment method lies in comparing the stabilized video processed by the video stabilization algorithm with the real stabilized video, and judging the advantages and disadvantages of the algorithm based on the differences between the two. In contrast, the no-reference quality assessment method does not require a real stabilized video as a reference. Instead, it uses a statistical model to measure the motion changes of the video before and after the stabilization process and conducts an assessment accordingly.

3.2.1. Full-Reference Quality Assessment

In full-reference quality assessment, a real and stable video is used as a reference standard. To conduct this assessment, we add jitter to the real stable video to generate a jittery video, which is then used as the input for the video stabilization algorithm. Subsequently, the performance of the video stabilization algorithm is evaluated by comparing the quality difference between the video processed by the algorithm and the original real stable video.

Common full-reference quality assessment methods include Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [

79], Mean Squared Error (MSE) [

80], and Structural Similarity (SSIM) [

79]. These methods are favored for their wide applicability and computability, and they are well-suited for integration into video optimization algorithms.

Offiah et al. [

81] proposed a full-reference image quality assessment method for the stabilization effect of medical endoscopic videos. Tanakian et al. [

73] used the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the motion path after processing by the stabilization algorithm and the real stable motion path as a distance metric to evaluate the quality of the video stabilization algorithm. Qu et al. [

82] constructed a dataset of stable and jittery videos required for full-reference quality assessment by synthesizing jittery videos and used the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) to evaluate the effect of the video stabilization algorithm. However, these methods have limitations in reflecting and examining more stability indicators. Zhang et al. [

83] proposed a new video stabilization quality assessment algorithm based on Riemannian metrics. By measuring and evaluating the motion difference between the video processed by the algorithm and the real stable video, it achieves higher accuracy, but the corresponding computational complexity also increases. Wang et al. [

84] combined feature point detection with full reference evaluation to adaptively adjust the stabilized image strength to measure video stability performance. Liu et al. [

58] used PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS to comprehensively evaluate the quality of synthesized frames. In addition, Ito et al. [

85] proposed a comprehensive evaluation index consisting of MSE, SSIM, resolution loss, and MSE, and collected a comprehensive dataset for video stabilization assessment.

Nevertheless, due to the limited capacity of the current paired datasets, the application of full-reference quality assessment methods in video stabilization assessment is still not widespread.

3.2.2. No-Reference Quality Assessment

Unlike full-reference quality assessment, no-reference quality assessment does not require paired real stable videos as references. It relies on statistical models to measure motion changes in videos before and after stabilization, thereby evaluating the effectiveness of video stabilization algorithms.

Niskanen et al. [

86] used low-pass/high-pass filter technology to separate the jitter component from stabilized videos processed by stabilization algorithms and evaluated their stability through the degree of jitter attenuation. However, this method has limitations in clearly determining the motion stability of stabilized videos.

To comprehensively evaluate the quality of videos processed by stabilization algorithms from multiple perspectives, Liu et al. [

31] proposed a set of objective evaluation indicators, including cropping rate, distortion degree, and stability. The cropping rate measures the remaining frame area after cropping empty pixel regions caused by motion compensation; the distortion degree quantifies the anisotropic scaling of homography between input and output frames; and stability aims to measure the stability and smoothness of the stabilized video. Their specific definitions and descriptions are as follows:

The cropping rate (Cropping) is an indicator used to measure the proportion of the frame area retained in the stabilized result after removing the boundaries of missing pixels. A higher ratio means less loss of original content, resulting in better visual quality. Specifically, the cropping rate of each frame is calculated by determining the homography scale factor between the input and output frames during the stabilization process. The cropping rate for the entire video is the average of the cropping rates of all frames.

The distortion degree (Distortion) describes the degree of distortion of the stabilized result compared to the original video. To quantify this indicator, we calculate the distortion value for each frame, which is equal to the ratio of the two largest eigenvalues of the affine part of the homography matrix. The distortion degree of the entire video is defined as the minimum distortion value among all frames.

The stability (Stability) indicator is used to evaluate the stability and smoothness of the video. We calculate the stability score through frequency-domain analysis of the camera path. Specifically, the rotation and translation sequences of all homography transformations between consecutive frames in the output video are treated as two time series. We then calculate the ratio of the lowest frequency components (2nd to 6th) to the full frequency (excluding the DC component) in these two sequences and take the smaller ratio as the stability score of the stabilized result.

Currently, the above CDS evaluation indicators are widely used in the field of video stabilization. However, when setting the high-low frequency separation threshold for this evaluation method, adjustments are usually required according to videos with different motion types. This feature necessitates flexible settings for specific scenarios in practical applications to ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of the evaluation results.

Zheng et al. [

87] proposed a no-reference video stabilization quality assessment algorithm based on the total curvature of motion paths. They first constructed homography matrices by detecting feature points in adjacent frames, then mapped these matrices to Lie group space to form motion paths. Finally, they used discrete geodesics to calculate the total curvature of the motion paths and used it as an indicator to measure video stability. Zhang et al. [

88] improved upon Zheng et al.’s work by using constrained paths to handle spatially varying motions and calculating the resulting weighted curvature to evaluate video stability.

Liu [

58] proposed a method to measure video stability using cumulative optical flow. However, current video stabilization quality assessment methods mainly focus on evaluating factors such as distortion, cropping, and path stability, while neglecting factors that may significantly impact video stability, such as lighting conditions, visual system characteristics, and accurate recognition of background regions. In future work, one of the major challenges we face is to explore more stability-related features and represent them through modeling to further improve the accuracy and universality of objective evaluation methods.

4. Benchmark Datasets for Video Stabilization

(1) The HUJ dataset proposed by Goldstein et al. comprises 42 videos, covering driving scenarios, dynamic scenes, zooming sequences, and walking motions.

(2) Koh et al. introduced the MCL dataset, containing 162 videos across seven categories: regular motion, jello effect, depth scenes, crowd environments, driving sequences, running motions, and object-focused scenarios.

(3) The BIT dataset proposed by Zhang et al. includes 45 videos spanning walking, climbing, running, cycling, driving, large parallax, crowd scenes, close-up objects, and low-light environments.

(4) Ito et al.’s QMUL dataset consists of 421 videos, encompassing regular, blurry, high-speed motion, low-light, textureless, parallax, discontinuous, depth, crowd, and close-up object scenarios.

With the integration of deep learning into video stabilization research, the following datasets have become pivotal for algorithm development and validation:

(5) The NUS dataset, containing 144 videos, covers seven distinct categories: regular motion, fast rotation, zooming, parallax, driving, crowd scenes, and running sequences.

(6) The DeepStab dataset is a purpose-built dataset for supervised deep learning in video stabilization, containing 61 pairs of synchronized videos, each with a duration of up to 30 seconds and a frame rate of 30 FPS. It encompasses diverse scenarios, such as indoor environments with large parallax and outdoor scenes featuring buildings, vegetation, and crowds. Camera motions include forward translation, lateral movement, rotation, and their composite dynamics, providing rich temporal-spatial variations. Notably, data collection employs dual-camera synchronization: one camera records stable footage, while the other captures handheld jitter, generating high-fidelity paired samples for training (as illustrated in

Figure 13).

(7) Building on their research in selfie video stabilization [

89], Yu et al. expanded and introduced the Selfie dataset, comprising 1,005 videos in total. The dataset employs Dlib for facial detection in each frame, tracking face occurrences across consecutive frames. Only video segments with successful face detection in at least 50 continuous frames are retained as specific face-focused clips, ensuring high-quality and targeted data through this stringent selection criterion. Uniquely, the Selfie dataset includes both regular color videos and corresponding Ground Truth Foreground Masks for each frame, providing rich annotations critical for selfie video stabilization research.

(8) Shi et al. proposed the Video+Sensor dataset, distinguished by its inclusion of 50 videos paired with gyroscope and OIS sensor logs. For research convenience, the dataset is meticulously divided into 16 training videos and 34 test videos. The test set is further categorized into six scenarios—regular motion, rotation, parallax, driving, human-centric, and running—to facilitate comprehensive evaluation of video stabilization algorithms across diverse real-world contexts.

(9) Li et al. introduced the IMU_VS dataset, encompassing 70 videos augmented with IMU sensor data across seven scenarios: walking, stair climbing/descending, static, translation, running, zooming, and rapid shaking. To ensure data diversity, 10 videos were collected for each scenario, with sensor logs detailing angular velocity and acceleration. The dataset is carefully partitioned into training (42 videos), validation (7 videos), and test (21 videos) subsets, supporting algorithm development, optimization, and evaluation at different stages.

(10) Leveraging the virtual scene generator Silver [

90], Kerim et al. innovatively proposed the VSAC105Real dataset, divided into two sub-datasets: VSNC35Synth and VSNC65Synth. VSNC35Synth focuses on normal weather conditions, containing 35 videos, while VSNC65Synth is broader, encompassing 65 videos across diverse weather scenarios—day/night, normal, rainy, foggy, and snowy—to simulate real-world filming environments.

In other special scenarios, such as ship videos in water scenes, the ISDS dataset [

91] optimizes the detection of small targets through a multi-scale weighted feature fusion model (YOLOv4-MSW), which provides data and modeling support for the application of steady image algorithms to dynamic water scenes.

In the field of deep learning for video stabilization, the NUS dataset stands as the most widely used resource, primarily due to its provision of numerous videos encompassing diverse motion types for algorithm validation. Meanwhile, the DeepStab dataset is highly favored during the training phase, owing to its inclusion of paired unstable/stable video sequences—an invaluable resource for supervised learning frameworks. The Selfie dataset is specifically tailored for researching selfie video stabilization methods, while the Video+Sensor dataset plays a pivotal role in advancing 3D video stabilization.

These meticulously collected and curated datasets have made substantial contributions to the progress of video stabilization, offering critical support for the development of novel stabilization approaches. However, to further enhance the generalizability and robustness of deep learning algorithms, ongoing efforts are needed to explore standardized datasets that incorporate a broader spectrum of motion types in the future.

5. Challenges and Future Directions

5.1. Current Challenges

Despite the significant progress and rapid development in the research and application of video stabilization over the years, we must acknowledge that numerous challenges and unresolved technical problems still persist. These challenges and issues drive us to pursue more efficient and precise stabilization results, with the aim of achieving more profound breakthroughs in the field of video stabilization.

Optical flow-based video stabilization methods struggle to obtain accurate camera motion during motion estimation. These methods provide the flexibility of nonlinear motion compensation and offer new ideas for video stabilization processing. However, when facing complex motions in the scene or a lack of reliable features, these methods often cannot effectively cope. Due to the lack of reliable rigid constraint conditions, they may produce obvious non-rigid distortions and artifacts, thereby affecting the stability effect of the video.

Sensor-based video stabilization methods have poor visual quality. These methods use motion sensor data, such as gyroscopes and accelerometers, to accurately capture the camera’s motion state. Since they do not depend on scene content, they can effectively avoid the impact of content complexity on the stabilization effect and achieve excellent video stabilization through precise distortion correction [

92,

93]. However, these methods typically stabilize the plane at infinity based on homography principles and cannot adapt to changes in scene depth. This leads to limitations in the stabilization effect in close-up scenarios due to residual parallax motion.

Warping-based video stabilization methods achieve video stabilization by estimating and smoothing camera trajectories. This method generates a pixel displacement field based on the transformation from the jittery trajectory to the smooth trajectory, and then warps the unstable video to obtain a stabilized video. However, during the warping process, some necessary source pixels may lie outside the boundary of the current unstable frame, inevitably causing holes near the boundary of the stabilized result view due to missing pixels. To maintain visual consistency, cropping is usually used to handle these holes, which may result in a reduction in effective frame size, changes in frame aspect ratio, and amplification of jitter. Previous studies have attempted to mitigate this issue by reducing the area of pixels outside the boundary(i.e.,limiting the maximum deformation displacement). However, this limitation creates a trade-off between stability and the cropping ratio: smoother trajectories typically mean larger cropping areas, and vice versa [

29,

47,

49,

94]. This trade-off is not ideal as it cannot provide the best visual experience. Therefore, how to minimize cropping areas and jitter amplification while maintaining video stability remains a challenge for warping-based video stabilization methods.

5.2. Future Directions

With the further advancement of research, there are still some worthy research directions in the field of video stabilization:

Model selection is the core aspect of video stabilization in practical applications. Among the current mainstream methods, the 2D model, with its high computational efficiency and robustness, dominates in lightweight scenes such as handheld devices, but it is difficult to effectively deal with the geometric distortion caused by parallax; while the 3D model can significantly alleviate the problem of parallax by means of depth perception and three-dimensional motion compensation, but the defects of high computational complexity and limited generalization capability make it difficult to cover the complex and changeable actual scenes. This trade-off between performance and efficiency makes it necessary for model selection to be closely integrated with specific application requirements. For example, in dynamic scenes, Huang et al. [

95] proposes a decomposed motion compensation framework that decouples the global camera motion from the local object motion and reduces parallax-induced distortions through hierarchical optimization; while in the field of optical flow estimation, literature [

96] proposes a spatio-temporal context modeling approach to optimize motion trajectory smoothness through optical flow-guided feature prediction, and the idea can be migrated to steady image algorithms to enhance the adaptability of the 2D model to complex motion. The integration of these cross-domain techniques suggests that hybrid strategies combining multimedia orientations (e.g. motion decomposition, compressed domain optimization) may provide more flexible solutions for model selection to achieve a balance between stability, efficiency, and visual quality in a given scene. A recent video-stabilized image study [

97] for flapping wing robots further validates this idea and significantly improves the accuracy of airborne detection and measurement.

Real-time online stabilization. In today’s era of widespread real-time applications, real-time online stabilization has become a hot but challenging problem. Warping-based stabilization methods often use feature matching in motion estimation to obtain motion trajectories, which limits the operating speed. With the development of deep learning, many deep learning-based stabilization methods can achieve real-time performance requirements. However, some of these methods also need to use a few future frames as network inputs, resulting in a fixed delay of several frames. How to maintain high-performance stabilization while maximizing the operating speed to achieve no latency is worth in-depth exploration in the future. For example, literature [

98] reduces redundant computations through optical flow-guided context modeling, and its lightweight design ideas (e.g., channel pruning and quantization) can be applied to accelerate the stabilized video model on mobile. Wang et al. [

99] proposes a video compression framework with spatio-temporal joint optimization, and its dynamic bit allocation strategy can provide an efficiency reference for the online processing of stabilized video algorithms.

Combined with other directions in the multimedia field, the video stabilization performance can be improved. For example, in the field of motion analysis, the skeleton-based angular feature enhancement method [

100] captures subtle motion differences through a three-stream integration strategy, and its key angular weighting strategy can be migrated to dynamic motion modeling in stabilized video to improve the robustness of complex scenes. In the video compression neighborhood SME [

101] proposes a hierarchical motion enhancement and temporal context reinforcement (TCR) module to achieve efficient video compression in resource-constrained devices, which provides compression-stable image co-optimization ideas for real-time processing of stable images on mobile.

Collecting more comprehensive standard datasets. Although many methods in the field of video stabilization have achieved good results at this stage, there is a lack of complete and comprehensive datasets in the deep learning field. This can lead to biased network outputs or overfitting, resulting in poor generalization and the inability to obtain mature and robust algorithms. Especially in the field of video stabilization, algorithms need to face various different motion scenarios that may exist in videos. Only datasets with sufficiently diverse motion types can help neural networks better handle such problems. For example, due to the lack of low-texture scene datasets, networks cannot learn how to effectively process such scenarios. If an appropriate amount of low-texture scene datasets are added to train the network, allowing the network to learn how to stabilize such scenes, the algorithm will achieve more robust results in more scenarios.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, with the deepening of research on digital video stabilization, deep learning-based video stabilization algorithms have become one of the hot research areas. Compared with traditional video stabilization, deep learning-based video stabilization algorithms can not only effectively handle video shake but also reduce distortion and cropping during the stabilization process.

In this paper, we first conduct an in-depth analysis of the research background and significance of video stabilization. Based on a comprehensive review and analysis of previous research achievements, this paper systematically expounds on the current mainstream video stabilization algorithms, mainly classified and described according to traditional and deep learning approaches based on their implementation methods. We then elaborate on their current development status and representative methods. Subsequently, the comprehensive evaluation metrics for video stabilization are introduced, and widely used datasets are summarized. Finally, the main challenges and future directions of this technology in practical applications are clearly pointed out.

References

- Baker, C.L.; Hess, R.F.; Zihl, J. Residual motion perception in a “motion-blind” patient, assessed with limited-lifetime random dot stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience 1991, 11, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Q.; Zhao, M. Stabilization of traffic videos based on both foreground and background feature trajectories. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2018, 29, 2215–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Khan, S.; Saba, T.; et al. Improved video stabilization using SIFT-log polar technique for unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCIS). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Tang, B.; Li, X.; Li, X. STFE-VC: Spatio-temporal feature enhancement for learned video compression. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Tang, B.; Li, X.; Li, X. Multiscale motion-aware and spatial-temporal-channel contextual coding network for learned video compression. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 316, 113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, F.; Yong, X.; Chen, D.; Xia, R.; Ye, B.; Gao, H.; Chen, Z.; Lyu, X. SSCNet: A spectrum-space collaborative network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, F.; Li, L.; Xu, N.; Liu, F.; Yuan, C.; Chen, Z.; Lyu, X. AAFormer: Attention-Attended Transformer for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; et al. Underwater target tracking control of an untethered robotic fish with a camera stabilizer. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2020, 51, 6523–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardani, B. Optical image stabilization for digital cameras. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 2006, 26, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- e Souza, M.R.; de Almeida Maia, H.; Pedrini, H. Rethinking two-dimensional camera motion estimation assessment for digital video stabilization: A camera motion field-based metric. Neurocomputing 2023, 559, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Watras, A.J.; Kim, J.J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.H. Efficient online real-time video stabilization with a novel least squares formulation and parallel AC-RANSAC. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2023, 96, 103922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mo, H.; Liu, F. A robust video stabilization method for camera shoot in mobile devices using GMM-based motion estimator. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2023, 110, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Rajiv, P.; Kumar, P.; Khari, M.; Verdú, E.; Crespo, R.G.; Manogaran, G. Feature based video stabilization based on boosted HAAR Cascade and representative point matching algorithm. Image and Vision Computing 2020, 101, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S., K.; S., R. Intelligent software defined network based digital video stabilization system using frame transparency threshold pattern stabilization method. Computer Communications 2020, 151, 419–427. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zheng, L.; Jia, W.; Liu, X. Real-time video stabilization via camera path correction and its applications to augmented reality on edge devices. Computer Communications 2020, 158, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolly, D.R.J.; Peter, J.D.; Josemin Bala, G.; Jagannath, D.J. Image fusion for stabilized medical video sequence using multimodal parametric registration. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 135, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, X.X.; Zhang, L. Encoding Shaky Videos by Integrating Efficient Video Stabilization. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2019, 29, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, W.; Wei, X.; Zhiqiang, H. Digital Video Stabilization Techniques:A Survey. Journal of Computer Research and Development 2017, 54. [Google Scholar]