Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

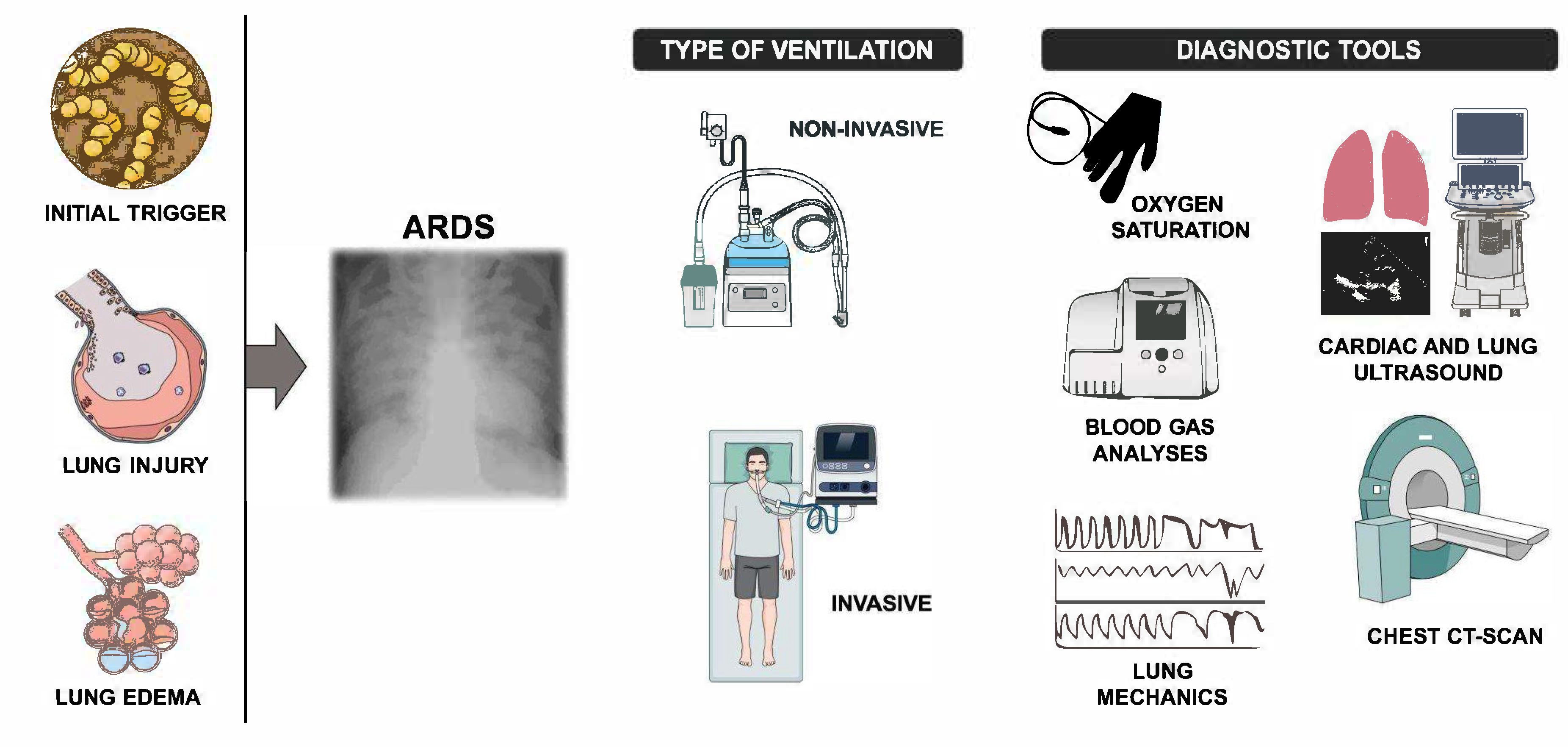

1. Introduction

2. Definition Of ARDS

| DIAGNOSIS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Ashbaught (1967) | AECC (1994) | Berlin (2012) | Kigali (2016) |

| Onset | RF with tachypnea, lung stiffness | RF with tachypnea, lung stiffness | RF within 1 week not fully explained by cardiac function or volume overload | RF within 1 week not fully explained by cardiac function or volume overload |

| Imaging | Bilateral opacities on CRX | Bilateral opacities on CRX | Bilateral opacities on CRX or CT not fully explained by effusion, collapse or nodules | Bilateral opacities on CRX or US not fully explained by effusion, collapse or nodules |

| Oxygenation | Oxygenation impairment | Oxygenation impairment: ALI (P/F ≤ 300 mmHg) ARDS (P/F ≤ 200 mmHg) |

Oxygenation impairment: Mild 200 < P/F ≤ 300 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O Moderate 100 < P/F ≤ 200 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O Severe P/F < 100 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O |

Oxygenation impairment: SpO2/FiO2 <315; no PEEP requirement |

| MANAGEMENT ESICM 2023 |

|---|

| Low Tv ≤ 4-8 mL/kg PBW |

| Pplat ≤ 30 cmH2O, DP ≤ 15 cmH2O, Reduction Mechanical Power |

| Individualized PEEP titration, avoid lung recruitment maneuvers |

| Use of NIV or HFNC to reduce risk of intubation |

| Prone Position (PaO2/FiO2 < 150, PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O) and awake prone position |

| Use of ECMO VV in severe ARDS, avoid ECCO2R |

| Avoid continuous infusion of NMBA |

2. Management Of ARDS

3. NIV and HFNC

3. New Criteria Of ARDS

3.1. Rationale and Evidence

| NEW ARDS DEFINITION | BERLIN DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Criteria for ALL ARDS categories | |

| |

|

Criteria for SPECIFIC ARDS categories NEW ARDS DEFINITION |

Criteria for SPECIFIC ARDS categories BERLIN DEFINITION |

|

|

4. Advantages and Limits

4.1. Advantages

| NEW ARDS DEFINITION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| New Definition | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical implications |

| Inclusion of HFNC/NIV | Expands recognition of “non intubated ARDS” | Potential for overdiagnosis | Closer monitoring needed to avoid delayed intubation |

| SpO₂/FiO₂ for diagnosis | Useful in low resource settings | Affected by perfusion, skin pigmentation, device accuracy | May require arterial blood gas confirmation |

| Use of lung ultrasound | Portable, bedside diagnostic tool | Operator-dependent, lacks standardized criteria | Training and standardization are essential |

| Applicability in resource-limited settings | Does not require PEEP for diagnosis | Excludes ECMO patients | May help early diagnosis but could overdiagnose ARDS |

4.2. Limitations

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cillóniz, C.; Torres, A.; Niederman, M.S. Management of Pneumonia in Critically Ill Patients. BMJ 2021, e065871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S. Pneumonia: Considerations for the Critically Ill Patient. In Critical Care Medicine; Elsevier, 2008; pp. 867–883, ISBN 978-0-323-04841-5.

- Morris, A.C. Management of Pneumonia in Intensive Care. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2018, 2, 101–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, D.L.; Menga, L.S.; Cesarano, M.; Rosà, T.; Spadaro, S.; Bitondo, M.M.; Montomoli, J.; Falò, G.; Tonetti, T.; Cutuli, S.L.; et al. Effect of Helmet Noninvasive Ventilation vs High-Flow Nasal Oxygen on Days Free of Respiratory Support in Patients With COVID-19 and Moderate to Severe Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure: The HENIVOT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019, 200, e45–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotberg, J.C.; Reynolds, D.; Kraft, B.D. Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Primer. Crit Care 2023, 27, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARDS Definition Task Force; V Marco Ranieri Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012, 307. [CrossRef]

- Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.G.; Pham, T.; Fan, E.; Brochard, L.; Esteban, A.; Gattinoni, L.; Van Haren, F.; Larsson, A.; McAuley, D.F.; et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA 2016, 315, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Arabi, Y.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bernard, G.; Bersten, A.D.; Brochard, L.J.; Calfee, C.S.; Combes, A.; Daniel, B.M.; Ferguson, N.D.; et al. A New Global Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, DavidG. ; Boyd Bigelow, D.; Petty, ThomasL.; Levine, BernardE. ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS IN ADULTS. The Lancet 1967, 290, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.F.; Matthay, M.A.; Luce, J.M.; Flick, M.R. An Expanded Definition of the Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988, 138, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Calfee, C.S.; Camporota, L.; Poole, D.; Amato, M.B.P.; Antonelli, M.; Arabi, Y.M.; Baroncelli, F.; Beitler, J.R.; Bellani, G.; et al. ESICM Guidelines on Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Definition, Phenotyping and Respiratory Support Strategies. Intensive Care Med 2023, 49, 727–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, T.L.; Ashbaugh, D.G. The Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Chest 1971, 60, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, G.R.; Artigas, A.; Brigham, K.L.; Carlet, J.; Falke, K.; Hudson, L.; Lamy, M.; Legall, J.R.; Morris, A.; Spragg, R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, Mechanisms, Relevant Outcomes, and Clinical Trial Coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 149, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.J.D.; McAuley, D.F.; Perkins, G.D.; Barrett, N.; Blackwood, B.; Boyle, A.; Chee, N.; Connolly, B.; Dark, P.; Finney, S.; et al. Guidelines on the Management of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. BMJ Open Resp Res 2019, 6, e000420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Zemans, R.L.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Arabi, Y.M.; Beitler, J.R.; Mercat, A.; Herridge, M.; Randolph, A.G.; Calfee, C.S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviello, E.D.; Kiviri, W.; Twagirumugabe, T.; Mueller, A.; Banner-Goodspeed, V.M.; Officer, L.; Novack, V.; Mutumwinka, M.; Talmor, D.S.; Fowler, R.A. Hospital Incidence and Outcomes of the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Using the Kigali Modification of the Berlin Definition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 193, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Thompson, B.T.; Ware, L.B. The Berlin Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Should Patients Receiving High-Flow Nasal Oxygen Be Included? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2021, 9, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazian, L.; Aubron, C.; Brochard, L.; Chiche, J.-D.; Combes, A.; Dreyfuss, D.; Forel, J.-M.; Guérin, C.; Jaber, S.; Mekontso-Dessap, A.; et al. Formal Guidelines: Management of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Ann. Intensive Care 2019, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, C.; Albert, R.K.; Beitler, J.; Gattinoni, L.; Jaber, S.; Marini, J.J.; Munshi, L.; Papazian, L.; Pesenti, A.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; et al. Prone Position in ARDS Patients: Why, When, How and for Whom. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 2385–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramji, H.F.; Hafiz, M.; Altaq, H.H.; Hussain, S.T.; Chaudry, F. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; A Review of Recent Updates and a Glance into the Future. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, N.; Sahetya, S.; Munshi, L.; Summers, C.; Abrams, D.; Beitler, J.; Bellani, G.; Brower, R.G.; Burry, L.; Chen, J.-T.; et al. An Update on Management of Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, A.; Hajage, D.; Capellier, G.; Demoule, A.; Lavoué, S.; Guervilly, C.; Da Silva, D.; Zafrani, L.; Tirot, P.; Veber, B.; et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, N.; Wu, H.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, K. The Impact of the New Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Criteria on Berlin Criteria ARDS Patients: A Multicenter Cohort Study. BMC Med 2023, 21, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.N.; Aggarwal, N.R.; Thompson, B.T.; Schmidt, E.P. Advancing Precision Medicine for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JCM 2023, 12, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, G.J.; Clemens, F.; Elbourne, D.; Firmin, R.; Hardy, P.; Hibbert, C.; Killer, H.; Mugford, M.; Thalanany, M.; Tiruvoipati, R.; et al. CESAR: Conventional Ventilatory Support vs Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure. BMC Health Serv Res 2006, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaky, A.M.; Elmasry, W.G.; Awad, A.H.; Khan, S.; Jarrahi, M. The Impact of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Therapy on Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gershengorn, H.B.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.-T.; Hsieh, S.J.; Dong, J.; Gong, M.N.; Chan, C.W. The Impact of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Use on Patient Mortality and the Availability of Mechanical Ventilators in COVID-19. Annals ATS 2021, 18, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, D.L.; Chen, L.; Brochard, L. Transpulmonary Pressure: Importance and Limits. Ann Transl Med 2017, 5, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frat, J.-P.; Thille, A.W.; Mercat, A.; Girault, C.; Ragot, S.; Perbet, S.; Prat, G.; Boulain, T.; Morawiec, E.; Cottereau, A.; et al. High-Flow Oxygen through Nasal Cannula in Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczkowski, S.; Ergan, B.; Bos, L.; Chatwin, M.; Ferrer, M.; Gregoretti, C.; Heunks, L.; Frat, J.-P.; Longhini, F.; Nava, S.; et al. ERS Clinical Practice Guidelines: High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Acute Respiratory Failure. Eur Respir J 2022, 59, 2101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, S.; Navalesi, P.; Conti, G. Time of Non-Invasive Ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultström, M.; Hellkvist, O.; Covaciu, L.; Fredén, F.; Frithiof, R.; Lipcsey, M.; Perchiazzi, G.; Pellegrini, M. Limitations of the ARDS Criteria during High-Flow Oxygen or Non-Invasive Ventilation: Evidence from Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients. Crit Care 2022, 26, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ven, F.-S.L.I.M.; Valk, C.M.A.; Blok, S.; Brouwer, M.G.; Go, D.M.; Lokhorst, A.; Swart, P.; Van Meenen, D.M.P.; Paulus, F.; Schultz, M.J.; et al. Broadening the Berlin Definition of ARDS to Patients Receiving High-Flow Nasal Oxygen: An Observational Study in Patients with Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure Due to COVID-19. Ann. Intensive Care 2023, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, V.M.; Rubenfeld, G.; Slutsky, A.S. Rethinking Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome after COVID-19: If a “Better” Definition Is the Answer, What Is the Question? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023, 207, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sorbo, L.; Nava, S.; Rubenfeld, G.; Thompson, T.; Ranieri, V.M. Assessing Risk and Treatment Responsiveness in ARDS. Beyond Physiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 197, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khatib, M.F.; Karam, C.J.; Zeeni, C.A.; Husari, A.W.; Bou-Khalil, P.K. Oxygenation Indexes for Classification of Severity of ARDS. Intensive Care Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catozzi, G.; Pozzi, T.; Nocera, D.; Camporota, L. Oxygenation Indexes for Classification of Severity of ARDS. Authors’ Reply. Intensive Care Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Ware, L.B.; Riviello, E.D.; Wick, K.D.; Thompson, T.; Martin, T.R. Reply to Liufu et al. and to Palanidurai et Al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 1280–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Grissom, C.K.; Moss, M.; Rice, T.W.; Schoenfeld, D.; Hou, P.C.; Thompson, B.T.; Brower, R.G. Nonlinear Imputation of Pao2/Fio2 From Spo2/Fio2 Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. CHEST 2016, 150, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, T.W.; Wheeler, A.P.; Bernard, G.R.; Hayden, D.L.; Schoenfeld, D.A.; Ware, L.B. Comparison of the Sp o 2 /F Io 2 Ratio and the Pa o 2 /F Io 2 Ratio in Patients With Acute Lung Injury or ARDS. Chest 2007, 132, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, A.; Pivetta, E.; Goffi, A.; Steinberg, I.; Arina, P.; Mazzeo, A.T.; Del Sorbo, L.; Veglia, S.; Davini, O.; Brazzi, L.; et al. Clinical Performance of Lung Ultrasound in Predicting ARDS Morphology. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongodi, S.; Chiumello, D.; Mojoli, F. Lung Ultrasound Score for the Assessment of Lung Aeration in ARDS Patients: Comparison of Two Approaches. Ultrasound Int Open 2024, 10, a–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, M.R.; Brower, R.G.; Parsons, P.E.; Phua, J.; Bos, L.D.J. The Global Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Ready for Prime Time? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviello, E.D.; Pisani, L.; Schultz, M.J. What’s New in ARDS: ARDS Also Exists in Resource-Constrained Settings. Intensive Care Med 2016, 42, 794–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlebach, R.; Pale, U.; Beck, T.; Markovic, S.; Seric, M.; David, S.; Keller, E. Limitations of SpO2 / FiO2-Ratio for Classification and Monitoring of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome—an Observational Cohort Study. Crit Care 2025, 29, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Pesenti, A.; Bellani, G.; Rubenfeld, G.; Fan, E.; Bugedo, G.; Lorente, J.A.; Fernandes, A.D.V.; Van Haren, F.; Bruhn, A.; et al. Outcome of Acute Hypoxaemic Respiratory Failure: Insights from the LUNG SAFE Study. Eur Respir J 2021, 57, 2003317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipanah-Lechner, N.; Cavalcanti, A.B.; Diaz, J.; Ferguson, N.D.; Myatra, S.N.; Calfee, C.S. From Berlin to Global: The Need for Syndromic Definitions of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanidurai, S.; Chan, Y.H.; Mukhopadhyay, A. “PEEP-Adjusted P/F Ratio” in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Call for Further Enhancement of Global Definition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 1279–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, K.; Ichikado, K.; Anan, K.; Nakamura, K.; Kawamura, K.; Suga, M.; Sakagami, T. The ROX Index (Index Combining the Respiratory Rate with Oxygenation) Is a Prognostic Factor for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, O.; Messika, J.; Caralt, B.; García-de-Acilu, M.; Sztrymf, B.; Ricard, J.-D.; Masclans, J.R. Predicting Success of High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Pneumonia Patients with Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure: The Utility of the ROX Index. Journal of Critical Care 2016, 35, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, L.D.J.; Laffey, J.G.; Ware, L.B.; Heijnen, N.F.L.; Sinha, P.; Patel, B.; Jabaudon, M.; Bastarache, J.A.; McAuley, D.F.; Summers, C.; et al. Towards a Biological Definition of ARDS: Are Treatable Traits the Solution? ICMx 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beitler, J.R.; Goligher, E.C.; Schmidt, M.; Spieth, P.M.; Zanella, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Calfee, C.S.; Cavalcanti, A.B. ; The ARDSne(x)t Investigators Personalized Medicine for ARDS: The 2035 Research Agenda. Intensive Care Med 2016, 42, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Husinat, L.; Azzam, S.; Al Sharie, S.; Araydah, M.; Battaglini, D.; Abushehab, S.; Cortes-Puentes, G.A.; Schultz, M.J.; Rocco, P.R.M. A Narrative Review on the Future of ARDS: Evolving Definitions, Pathophysiology, and Tailored Management. Crit Care 2025, 29, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).