Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental fish

2.2. Experimental pesticides

2.3. Experimental set-up

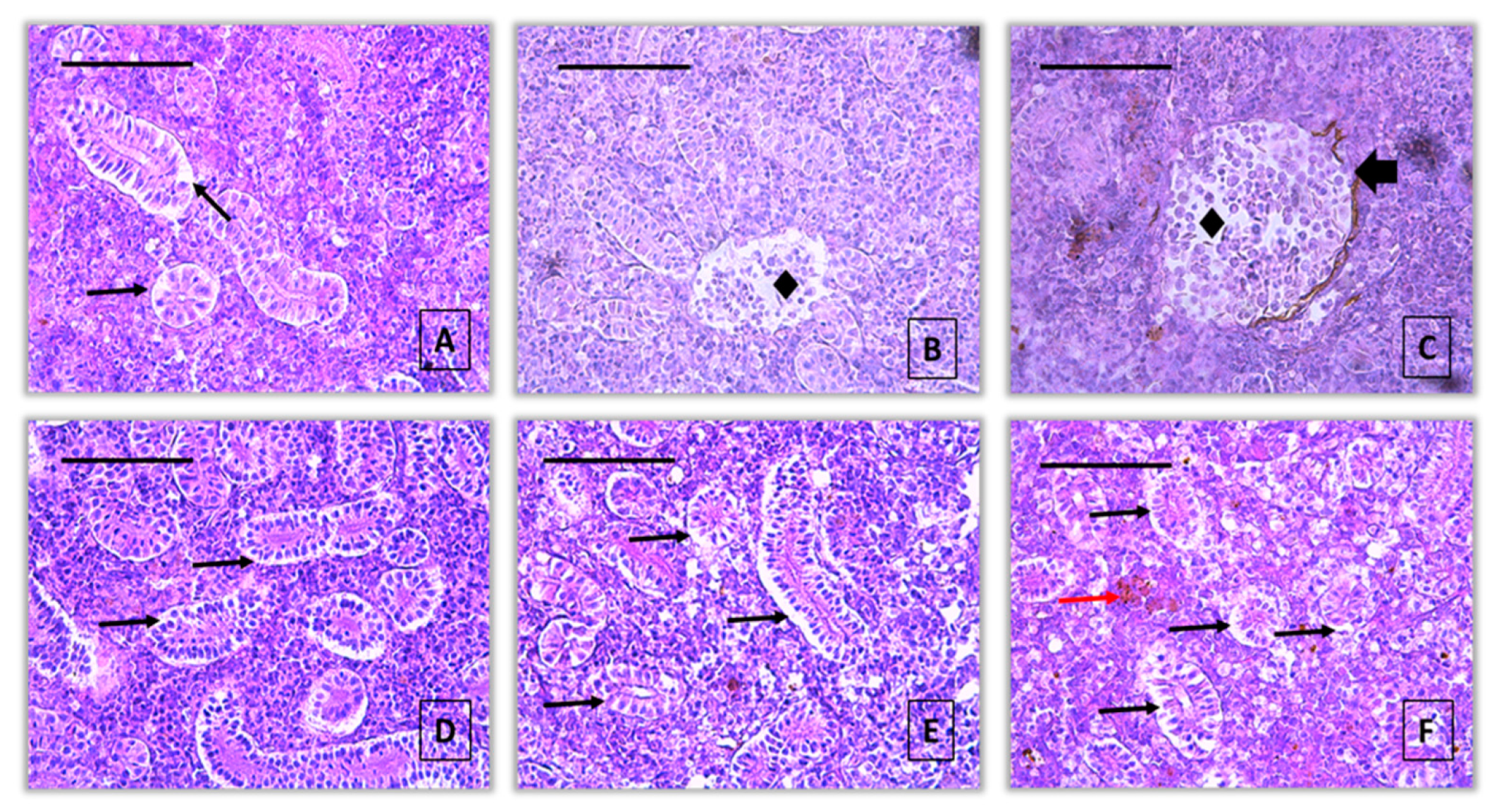

2.4. Histopathological assessment

2.5. Statistical analysis

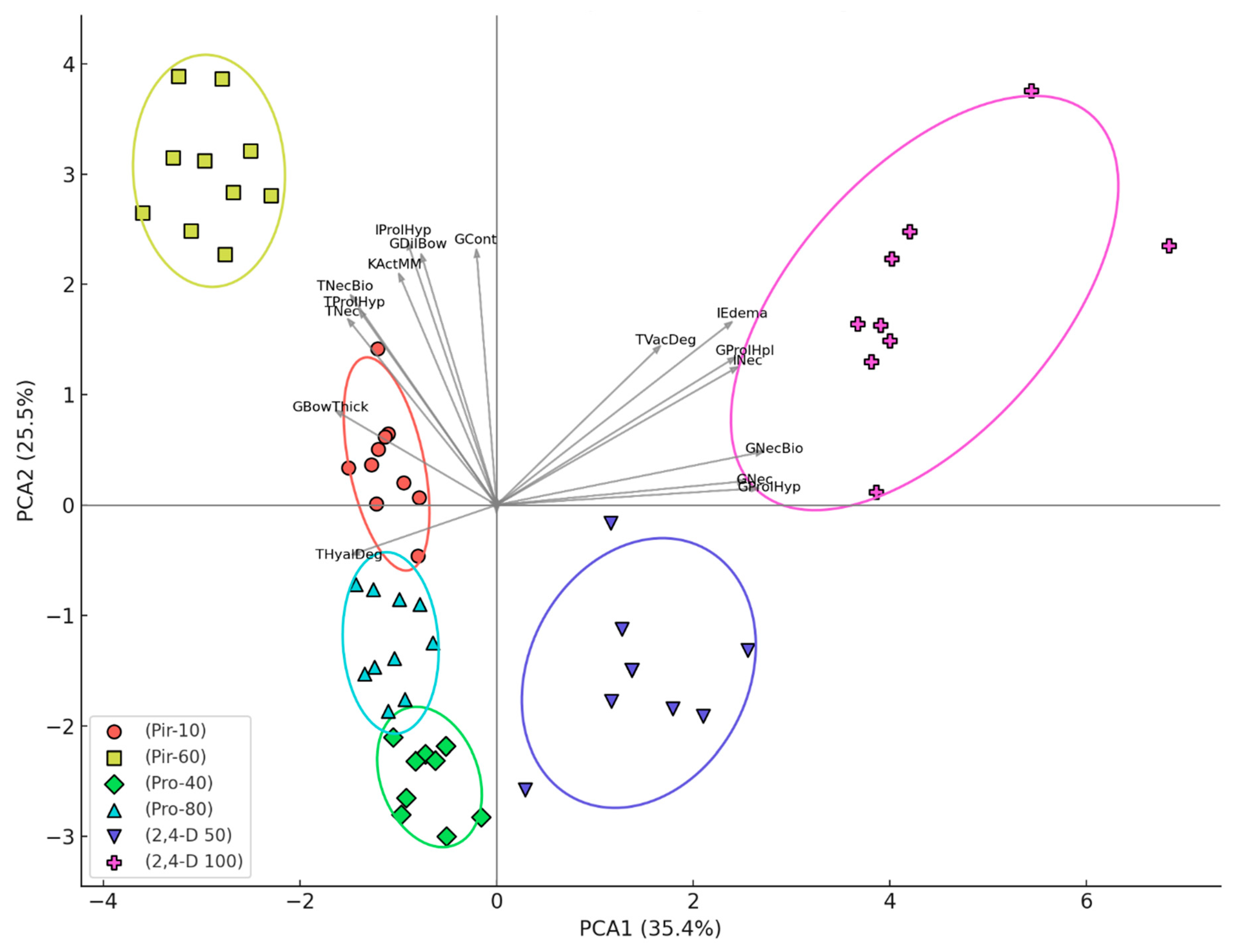

3. Results and Discussion

| Reaction pattern | Орган | Alteration |

Importance factor |

Score value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Control |

2, 4 - D | |||||

| 50 μg/L | 100 μg/L | |||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Kidney | Haemorrhage | WKC1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Hyperaemia | WKC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Aneurysms | WKC3 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for changes in the circulatory system | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | |||

| Degenerative changes | Tubule | Vacuolar degeneration | WKR1 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 4C |

| Hyaline degeneration | WKR2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Necrobiosis | WKR3 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Necrosis | WKR4 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Glomerulus | Dilatation of the Bowman's capsule | WKR5 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 2C | |

| Contraction | WKR6 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Necrobiosis* | WKR7 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Necrosis | WKR8 = 3 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

|

Interstitial tissue |

Necrosis | WKR9 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 1B | |

| Index forthedegenerative changes | IKR = 0A | IKR=5B | IKR=15C | |||

| Proliferative changes | Tubule | Hypertrophy | WKP1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 1B |

| Hyperplasia | WKP2 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Glomerulus | Hypertrophy | WKP3 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 3C | |

| Hyperplasia | WKP4 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Thickening of Bowman's capsular membrane | WKP5 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

|

Interstitial tissue |

Hypertrophy | WKP6 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 1B | |

| Edema | WKP7 = 2 | 0A | 2B | 4C | ||

| Index fortheproliferative changes | IKP = 0A | IKP =6B | IKP=15C | |||

| Inflammation | Kidney | Infiltration | WKI1 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Activation of melano-macrophages | WKI2 = 2 | 0A | 2B | 2B | ||

| Index fortheinflammatory processes | IKI = 0A | IKI =4B | IKI =4B | |||

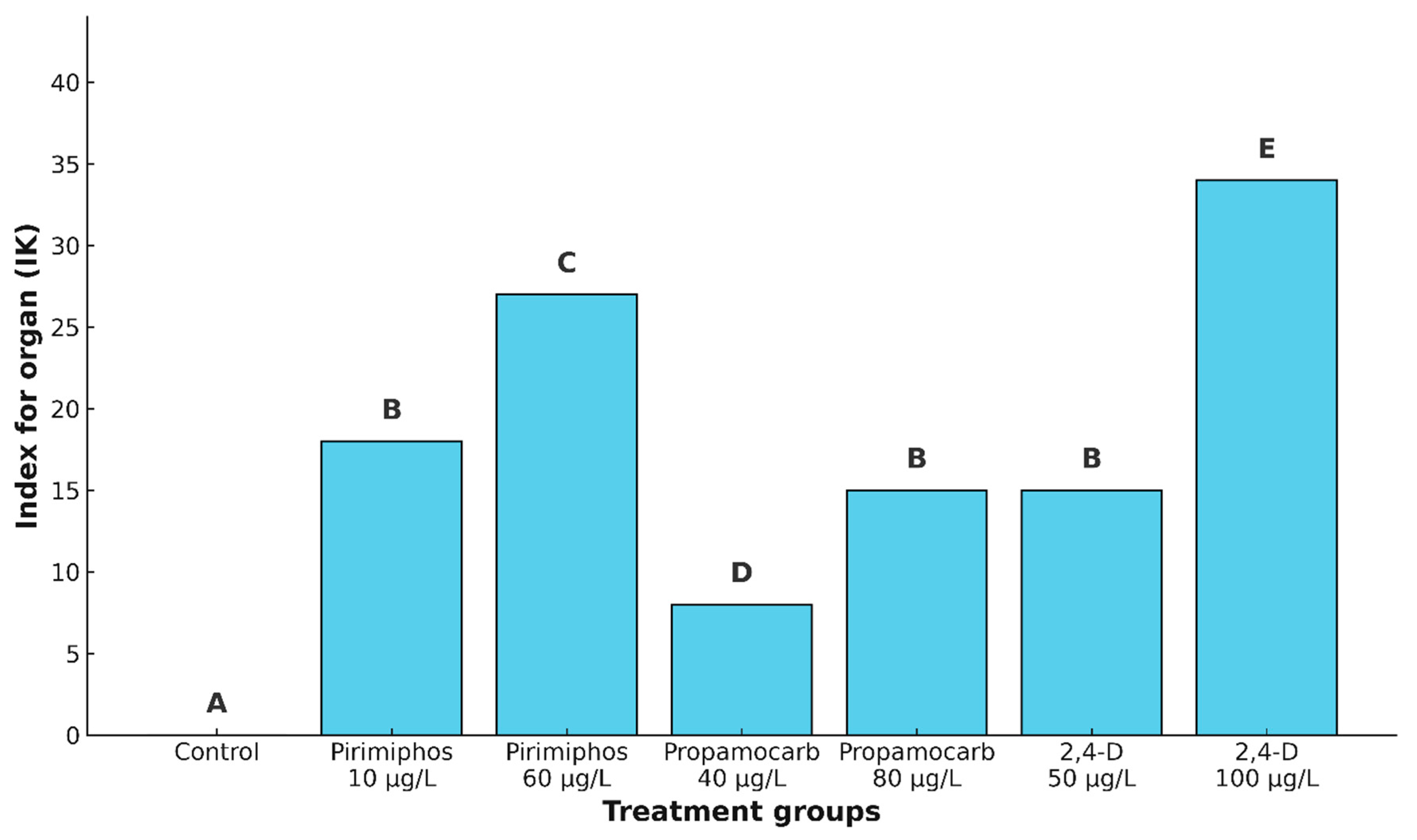

| Index for organ IK | IK = 0A | IK=15B | IK=34C | |||

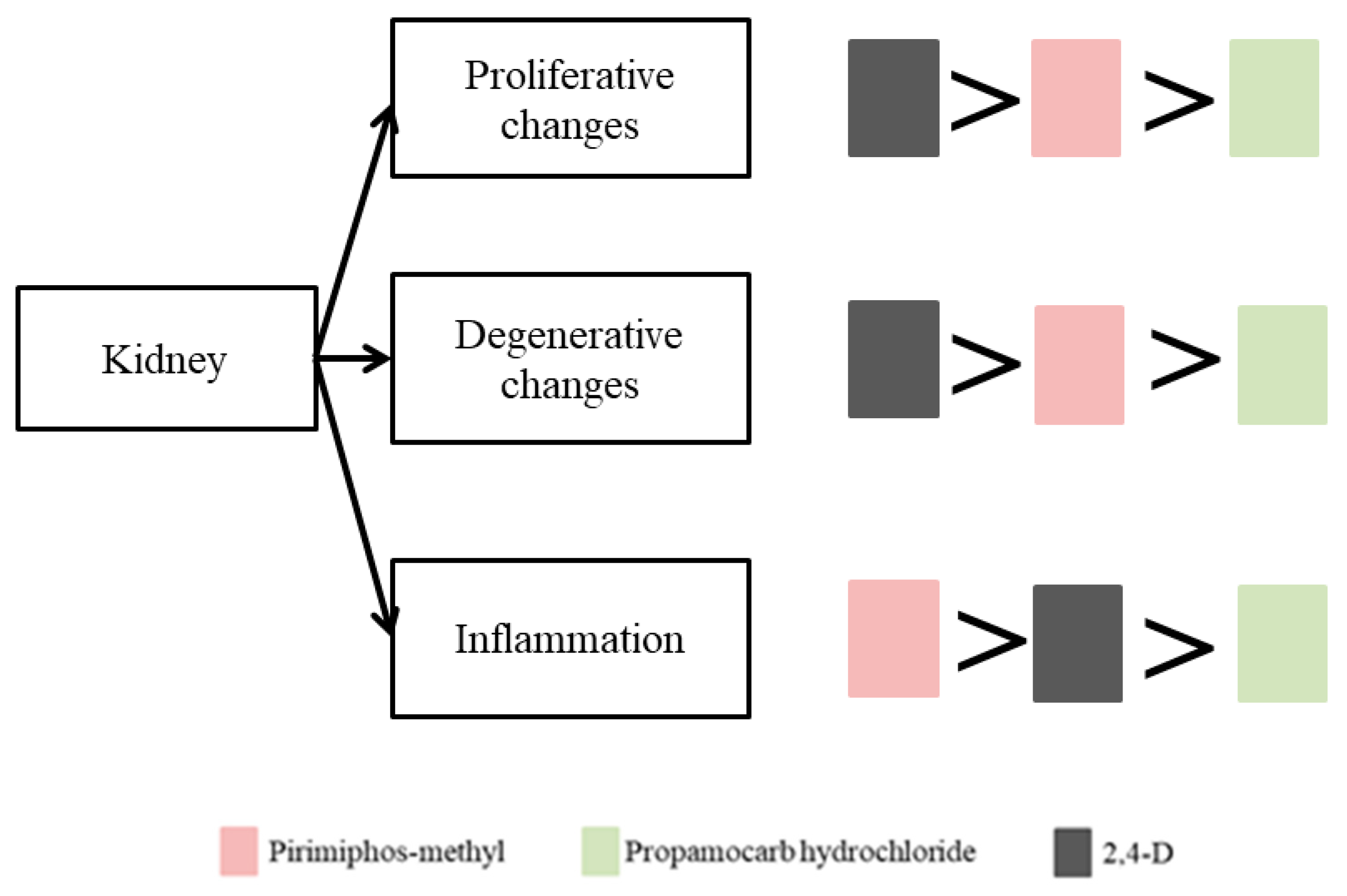

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US EPA. What is a Pesticide? Chapter 6—Insecticides and environmental pesticide control subchapter II—Environmental pesticide control. Se. 136—Definitions (2013).

- Tang, F.H.M. , et al., Risk of pesticide pollution at the global scale. Nature Geoscience, 2021. 14(4): p. 206-210. [CrossRef]

- Zaller, J.G., Daily Poison: Pesticides - an Underestimated Danger. Springer Nature 2020.

- Hvezdova, M. , et al., Currently and recently used pesticides in Central European arable soils. Sci Total Environ, 2018. 613-614: p. 361-370. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.S.A. and N. Hidayah, Global Trade and Pesticide Use, in The Interplay of Pesticides and Climate Change: Environmental Dynamics and Challenges, B.R. Babaniyi and E.E. Babaniyi, Editors. 2025, Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham. p. 111-126.

- Sharma, A. , et al., Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Applied Sciences, 2019. 1(11): p. 1446. [CrossRef]

- Sjerps, R.M.A. , et al., Occurrence of pesticides in Dutch drinking water sources. Chemosphere, 2019. 235: p. 510-518. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G., J.P. Monzon, and O. Ernst, Cropping system-imposed yield gap: Proof of concept on soybean cropping systems in Uruguay. Field Crops Research, 2021. 260: p. 107944. [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, M. , et al., Pesticides in Drinking Water-A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(2). [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Parada, A. , et al., Recent advances and open questions around pesticide dynamics and effects on freshwater fishes. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 2018. 4: p. 38-44. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.M. , et al., Occurrence, impacts and general aspects of pesticides in surface water: A review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 2020. 135: p. 22-37.

- Souza-Bastos, L.R. , et al., Evaluation of the water quality of the upper reaches of the main Southern Brazil river (Iguacu river) through in situ exposure of the native siluriform Rhamdia quelen in cages. Environ Pollut, 2017. 231(Pt 2): p. 1245-1255.

- Ortiz, J.B., M.L.G. De Canales, and C. Sarasquete, Histopathological changes induced by lindane (γ-HCH) in various organs of fishes. SCIENTIA MARINA, 2003. 67(1): p. 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F., I. Qureshi, and M. Ali, Histopathological changes in the kidney of common carp, Cyprinus carpio following nitrate exposure. J. Res. Sci, 2004. 15.

- Sachi, I.T.C. , et al., Biochemical and morphological biomarker responses in the gills of a Neotropical fish exposed to a new flavonoid metal-insecticide. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2021. 208: p. 111459. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.J. and M.L. Brown, Relationships among invasive common carp, native fishes and physicochemical characteristics in upper Midwest (USA) lakes. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 2011. 20(2): p. 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Kloskowski, J. , Impact of common carp Cyprinus carpio on aquatic communities: Direct trophic effects versus habitat deterioration. Fundamental and Applied Limnology / Archiv für Hydrobiologie, 2011. 178: p. 245-255. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H. , et al., Pollution Problem in River Kabul: Accumulation Estimates of Heavy Metals in Native Fish Species. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 537368. [CrossRef]

- Xing, H. , et al., Oxidative stress response and histopathological changes due to atrazine and chlorpyrifos exposure in common carp. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 2012. 103(1): p. 74-80. [CrossRef]

- Mhadhbi, L. and R. Beiras, Acute Toxicity of Seven Selected Pesticides (Alachlor, Atrazine, Dieldrin, Diuron, Pirimiphos-Methyl, Chlorpyrifos, Diazinon) to the Marine Fish (Turbot, Psetta maxima). Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2012. 223(9): p. 5917-5930. [CrossRef]

- Stepic, S. , et al., Effects of individual and binary-combined commercial insecticides endosulfan, temephos, malathion and pirimiphos-methyl on biomarker responses in earthworm Eisenia andrei. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2013. 36(2): p. 715-723. [CrossRef]

- Fleurat-Lessard, F. , et al., Effects of processing on the distribution of pirimiphos-methyl residues in milling fractions of durum wheat. Journal of Stored Products Research, 2007. 43(4): p. 384-395. [CrossRef]

- Oxborough, R.M. , Trends in US President's Malaria Initiative-funded indoor residual spray coverage and insecticide choice in sub-Saharan Africa (2008-2015): urgent need for affordable, long-lasting insecticides. Malar J, 2016. 15: p. 146.

- Dengela, D. , et al., Multi-country assessment of residual bio-efficacy of insecticides used for indoor residual spraying in malaria control on different surface types: results from program monitoring in 17 PMI/USAID-supported IRS countries. Parasit Vectors, 2018. 11(1): p. 71. [CrossRef]

- Oakeshott, J.G. , et al., Comparing the organophosphorus and carbamate insecticide resistance mutations in cholin- and carboxyl-esterases. Chem Biol Interact, 2005. 157-158: p. 269-75. [CrossRef]

- Donarski, W.J. , et al., Structure-activity relationships in the hydrolysis of substrates by the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta. Biochemistry, 1989. 28(11): p. 4650-5. [CrossRef]

- Elersek, T. and M. Filipic, Organophosphorous Pesticides - Mechanisms of Their Toxicity. 2011.

- Khan, H.A.A. , Variation in susceptibility to insecticides and synergistic effect of enzyme inhibitors in Pakistani strains of Trogoderma granarium. Journal of Stored Products Research, 2021. 91: p. 101775. [CrossRef]

- John, H. , et al., Chapter 56 - Toxicokinetic Aspects of Nerve Agents and Vesicants, in Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents (Second Edition), R.C. Gupta, Editor. 2015, Academic Press: Boston. p. 817-856.

- Pieroh, E.A. , Krass, W., Hemmen, C., 1978. Propamocarb, einneues Fungizid zur Abwehr von Oomyceten im Zierpflanzen- und Gemüsebau. Meded. Fac. Landbouw. Rijksuniv. Gent, 43, 933-942. 1978.

- Taylor, J.C. , et al., Determination of residues of propamocarb in wine by liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry with direct injection. Food Addit Contam, 2004. 21(6): p. 572-7. [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, M. and A. de Kok, Determination of propamocarb in vegetables using polymer-based high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A, 2002. 972(2): p. 231-9.

- Sahoo, S., R.S. Battu, and B. Singh, Development and Validation of QuEChERS Method for Estimation of Propamocarb Residues in Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) and Soil. American Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2011. 02. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrahman, S.H. and M.M. Almaz, Degradation of propamocarb-hydrochloride in tomatoes, potatoes and cucumber using HPLC-DAD and QuEChERS methodology. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, 2012. 89(2): p. 302-5.

- Mohamed, H. Mpina, F.H., Fenamidone + Propamocarb Hydrochloride: A Promising Package for the Control of Early and Late Blights of Tomatoes in Northern Tanzania. Int. J. Agr. Forestry, 3(3), 1-7, 2016.

- Wang, Z. , et al., Exogenous 24-epibrassinolide regulates antioxidant and pesticide detoxification systems in grapevine after chlorothalonil treatment. Plant Growth Regulation, 2017. 81(3): p. 455-466. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , et al., Predicting the Relative Bioavailability of DDT and Its Metabolites in Historically Contaminated Soils Using a Tenax-Improved Physiologically Based Extraction Test (TI-PBET). Environ Sci Technol, 2016. 50(3): p. 1118-25. [CrossRef]

- USEPA. 1995. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Propamocarb Hydrochloride R.E.D. FACTS - Prevention, P.а.T.S.W.

- Elliott, M., S.F. Shamoun, and G. Sumampong, Effects of systemic and contact fungicides on life stages and symptom expression of Phytophthora ramorum in vitro and in planta. Crop Protection, 2015. 67: p. 136-144. [CrossRef]

- Dehnert, G.K. , et al., Effects of low, subchronic exposure of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and commercial 2,4-D formulations on early life stages of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas). Environ Toxicol Chem, 2018. 37(10): p. 2550-2559.

- Heap, I. 2022. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. https://www.weedscience.org.

- USEPA. 2015. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage 2008–2012 Market Estimates. https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/pesticides-industrysales-and-usage-2008-2012-market-estimates.

- Islam, F. , et al., 2,4-D attenuates salinity-induced toxicity by mediating anatomical changes, antioxidant capacity and cation transporters in the roots of rice cultivars. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 10443. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. , Insight into the mode of action of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) as an herbicide. J Integr Plant Biol, 2014. 56(2): p. 106-13.

- von Stackelberg, K. , A Systematic Review of Carcinogenic Outcomes and Potential Mechanisms from Exposure to 2,4-D and MCPA in the Environment. J Toxicol, 2013. 2013: p. 371610.

- RED. 2006. Reregistration eligibility decision (RED) 2, -.D.U.s.e.P.A.

- da Fonseca, M.B. , et al., The 2,4-D herbicide effects on acetylcholinesterase activity and metabolic parameters of piava freshwater fish (Leporinus obtusidens). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2008. 69(3): p. 416-20.

- Kiljanek, T. , et al., Multi-residue method for the determination of pesticides and pesticide metabolites in honeybees by liquid and gas chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry--Honeybee poisoning incidents. J Chromatogr A, 2016. 1435: p. 100-14. [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.L. , et al., Solar-powered electrokinetic remediation for the treatment of soil polluted with the herbicide 2,4-D. Electrochimica Acta, 2016. 190: p. 371-377. [CrossRef]

- Gul, U. and H. Silah, Monitoring 2,4-D removal by filamentous fungi using electrochemical methods. Biotech Studies, 2025. 34: p. 52-65. [CrossRef]

- Islam, F. , et al., Potential impact of the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on human and ecosystems. Environ Int, 2018. 111: p. 332-351. [CrossRef]

- Bartczak, P. , et al., Saw-sedge Cladium mariscus as a functional low-cost adsorbent for effective removal of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid from aqueous systems. Adsorption, 2016. 22(4): p. 517-529. [CrossRef]

- APHA. 2005. Standard methods for examination of water and wastewater, s.E.W., American Public Health Association.

- Rosseland, B.O. , et al., Brown Trout in Lochnagar: Population and Contamination by Metals and Organic Micropollutants, in Lochnagar: The Natural History of a Mountain Lake, N.L. Rose, Editor. 2007, Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht. p. 253-285.

- relevance, D.E.o.t.E.P.a.o.t.C.o.S.o.t.p.o.a.u.f.s.p.T.w.E.

- Romeis, B. , Mikroskopische technik. München: Urban und Schwarzenberg, p. 697. Radic, Z., Taylor, P. 2006. Structure and function of cholinesterases. Toxicol. Organo-phosphat. Carbamate Comp., 1, 161-186. 1989.

- Bernet, D. , et al., Histopathology in fish: proposal for a protocol to assess aquatic pollution. Journal of Fish Diseases, 1999. 22(1): p. 25-34.

- Saraiva, A. , et al., A histology-based fish health assessment of farmed seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Aquaculture, 2015. 448: p. 375-381. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, S. , et al., Assessment of fish health status in four Swiss rivers showing a decline of brown trout catches. Aquatic Sciences, 2007. 69(1): p. 11-25. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H. and W.A. and Wallis, Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1952. 47(260): p. 583-621.

- Mann, H.B. and D.R. Whitney, On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 1947. 18: p. 50-60.

- Pedregosa, F. , et al., Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2012. 12.

- Hunter, J.D. , Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science & Engineering, 2007. 9(3): p. 90-95.

- Takashima, F. and T. Hibiya, An Atlas of Fish Histology: Normal and Pathological Features. 1995: Kodansha Limited.

- Donaldson, E.M. pituitary-interrenal axis as an indicator of stress in fish. 1981.

- Wendelaar Bonga, S.E. , The stress response in fish. Physiol Rev, 1997. 77(3): p. 591-625. [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, S. , et al., Renal glomerulogenesis in medaka fish, Oryzias latipes. Dev Dyn, 2008. 237(9): p. 2342-52. [CrossRef]

- Mobjerg, N., A. Jespersen, and M. Wilkinson, Morphology of the kidney in the West African caecilian, Geotrypetes seraphini (Amphibia, Gymnophiona, Caeciliidae). J Morphol, 2004. 262(2): p. 583-607. [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E.I. , Gill and kidney histopathology in the freshwater fish Cyprinus carpio after acute exposure to deltamethrin. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2006. 22(2): p. 200-4. [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, A.M. , et al., Toxicity bioassay and sub-lethal effects of diazinon on blood profile and histology of liver, gills and kidney of catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Braz J Biol, 2019. 79(2): p. 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A. , et al., Fipronil (Phenylpyrazole) induces hemato-biochemical, histological and genetic damage at low doses in common carp, Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758). Ecotoxicology, 2018. 27(9): p. 1261-1271. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Y. Bu, and X. Li, Immunological and histopathological responses of the kidney of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) sublethally exposed to glyphosate. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2015. 39(1): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Boran, H. , et al., Assessment of acute toxicity and histopathology of the fungicide captan in rainbow trout. Exp Toxicol Pathol, 2012. 64(3): p. 175-9. [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S. , et al., Sumithion induced structural erythrocyte alteration and damage to the liver and kidney of Nile tilapia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2021. 28(27): p. 36695-36706. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S. , et al., Toxic effects of agro-pesticide cypermethrin on histological changes of kidney in Tengra, Mystus tengara. Asian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 2018. 3: p. 494. [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E.I. and E. Unlu, Sublethal effects of commercial deltamethrin on the structure of the gill, liver and gut tissues of mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis: A microscopic study. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2006. 21(3): p. 246-53. [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, V. and M. Narayanan, Heavy Metal Induced Histopathological Alterations in Selected Organs of the Cyprinus carpio L.(Common Carp). International Journal of Environmental Research (ISSN: 1735-6865) Vol 3 Num 1, 2009. 3.

- Mohammod Mostakim, G. , et al., Alteration of Blood Parameters and Histoarchitecture of Liver and Kidney of Silver Barb after Chronic Exposure to Quinalphos. J Toxicol, 2015. 2015: p. 415984. [CrossRef]

- Sigamani, D. , Effect of herbicides on fish and histological evaluation. 2015: p. 437-440.

- Ayoola, S.O.a.A., E.K. , Histopathological Effect of Cypermethrin on Juvenile African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus). World Journal of Biological Research. Vol.1(2): 1-14. 2008.

- Ortiz-Delgado, J., M. Canales, and C. Sarasquete, Cambios histopatológicos inducidos por lindano (?HCH) en varios órganos de peces. Scientia Marina, 2003. 67.

- Das, B. and S. Mukherjee, A histopathological study of carp (Labeo rohita) exposed to hexachlorocyclohexane. Veterinarski Arhiv, 2000. 70.

- Tilak, K., K. Veeraiah, and K. Yacobu, Studies on histopathological changes in the Gill, liver and kidney of Ctenopharyngodon idellus (Valenciennes) exposed totechnical fenvalerate and EC 20%. Pollution Research, 2001. 20: p. 387-393.

- Velmurugan, B. , et al., The effects of monocrotophos to different tissues of freshwater fish Cirrhinus mrigala. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, 2007. 78(6): p. 450-4. [CrossRef]

- Olatubi, O.K. and A. Ojokoh, Effects of Fermentation and Extrusion on the Proximate Composition of Corn-Groundnut Flour Blends. Nigerian Journal of Biotechnology, 2016. 30: p. 59. [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Control | Pirimiphos-methyl | Propamocarb hydrochloride | 2,4-D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μg/L | 60 μg/L | 40 μg/L | 80 μg/L | 50 μg/L | 100 μg/L | ||

| Total length(cm) | 9,16±0,4 | 10,44±0,8 | 11,49±0,5 | 9,64±0,63 | 8,67±2,9 | 9,31±0,2 | 11,13±0,3 |

| Weight(g) | 18,83±5,7 | 19,25±2,8 | 18,89±2.4 | 19,11±3,1 | 19,57±2,7 | 16,28±2,5 | 15,87±3,5 |

| Pesticide | Recommended dose | Dilution relative to LC50 | Experimental concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pirimiphos-methyl | 0.00015 mL/m3 - 1 mL/dka | x 60 000 | 10 μg/L |

| x 10 000 | 60 μg/L | ||

| Propamocarb hydrochloride | 0.01-0.3 mL/dka | x 2 000 | 40 μg/L |

| x 1 000 | 80 μg/L | ||

| 2,4-D | 120-200 mL/dka | x 2 000 | 50 μg/L |

| x 1 000 | μg/L |

| Pirimiphos-methyl | pH | To | Dissolved oxygen mg/L |

Electrical conductivity μS/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 8,3±,.05 | 17,5±0,05 | 9±0,05 | 365±0.05 |

| 10 μg/L | 8,2±0,05 | 17±0,05 | 8,5±0,05 | 426±0.05 |

| 60 μg/L | 8,1±0,05 | 17,5±0,05 | 7,3±0,05 | 473±0.05 |

| Propamocarb hydrochloride | pH | To |

Dissolved oxygen mg/L |

Electrical conductivity μS/cm |

| Control | 8,5±0,05 | 17,5±0,05 | 9±0,05 | 365±0,05 |

| 40 μg/L | 8,1±0,05 | 18±0,05 | 8,1±0,05 | 433±0,05 |

| 80 μg/L | 7,9±0,05 | 18,5±0,05 | 7,5±0,05 | 485±0,05 |

| 2,4-D | pH | To |

Dissolved oxygen mg/L |

Electrical conductivity μS/cm |

| Control | 8,5±0,05 | 17,5±0,05 | 9±0,05 | 365±0,05 |

| 50 μg/L | 7,5±0,05 | 17,5±0,05 | 8,2±0,05 | 451±0,05 |

| 100 μg/L | 6,9±0,05 | 18,5±0,05 | 7,7±0,05 | 469±0,05 |

| Reaction pattern |

Organ | Alteration | Importance factor | Score value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Pirimiphos-methyl | |||||

| 10 μg/L | 60 μg/L | |||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Kidney | Haemorrhage | WKC1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Hyperaemia | WKC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Aneurysms | WKC3 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index for the circulatory system | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | |||

| Degenerative changes | Tubule | Vacuolar degeneration | WKR1 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 2B |

| Hyaline degeneration | WKR2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Necrobiosis | WKR3 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Necrosis | WKR4 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Glomerulus | Dilatation of the Bowman's capsule | WKR5 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 3C | |

| Contraction | WKR6 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Necrobiosis* | WKR7 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Necrosis | WKR8 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Interstitial tissue | Necrosis | WKR9 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |

| Index forthedegenerative changes | IKR = 0A | IKR=5B | IKR=12C | |||

| Proliferative changes | Tubule | Hypertrophy | WKP1 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 2B |

| Hyperplasia | WKP2 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Glomerulus | Hypertrophy | WKP3 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |

| Hyperplasia | WKP4 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Thickening of Bowman's capsular membrane | WKP5 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 1B | ||

| Interstitial tissue | Hypertrophy | WKP6 = 1 | 0A | 3B | 3B | |

| Edema | WKP7 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Index fortheproliferative changes | IKP = 0A | IKP = 7B | IKP = 9B | |||

| Inflammation | Kidney | Infiltration | WKI1 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A |

| Activation of melanomacrophages | WKI2 = 2 | 0A | 3B | 3B | ||

| Index fortheinflammatory processes | IKI = 0A | IKI =6B | IKI =6B | |||

| Index fortheorgan | IK = 0A | IK=18B | IK=27C | |||

| Reaction pattern |

Organ | Alteration | Importance factor | Score value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Propamocarb hydrochloride | ||||||

| 40 μg/L | 80 μg/L | ||||||

| Changes in the circulatory system | Kidney | Haemorrhage | WKC1 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |

| Hyperaemia | WKC2 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Aneurysms | WKC3 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Index for changes in the circulatory system | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | IKC =0A | ||||

| Degenerative changes | Tubule | Vacuolar degeneration | WKR1 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 3C | |

| Hyaline degeneration | WKR2 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 2C | |||

| Necrobiosis | WKR3 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Necrosis | WKR4 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Glomerulus | Dilatation of the Bowman's capsule | WKR5 = 1 | 0A | 2B | 2B | ||

| Contraction | WKR6 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Necrobiosis* | WKR7 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Necrosis | WKR8 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

|

Interstitial tissue |

Necrosis | WKR9 = 3 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Index forthedegenerative changes | IKR = 0A | IKR=4B | IKR=7C | ||||

| Proliferative changes | Tubule | Hypertrophy | WKP1 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 1B | |

| Hyperplasia | WKP2 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Glomerulus | Hypertrophy | WKP3 = 1 | 0A | 1B | 1B | ||

| Hyperplasia | WKP4 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Thickening of Bowman's capsular membrane | WKP5 = 2 | 0A | 0B | 1B | |||

| Interstitial tissue | Hypertrophy | WKP6 = 1 | 0A | 0A | 0A | ||

| Edema | WKP7 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |||

| Index fortheproliferative changes | IKP = 0A | IKP =2B | IKP =4C | ||||

| Inflammation | Kidney | Infiltration | WKI1 = 2 | 0A | 0A | 0A | |

| Activation of melano-macrophages | WKI2 = 2 | 0A | 1B | 2C | |||

| Index for inflammatory processes | IKI = 0A | IKI =2B | IKI =4B | ||||

| Index for organ IK | IK = 0A | IK=8B | IK=15C | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).