1. Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) remains one of the most common and concerning nutritional disorders globally, particularly among adolescent girls. IDA occurs when iron availability is insufficient to meet the body’s needs for hemoglobin production, leading to reduced oxygen transport, which in turn affects physical health, cognitive development, and academic performance [

1,

2]. Adolescents face heightened vulnerability due to accelerated growth and the onset of menstruation, which increase iron requirements [

3,

4].

Globally, anemia affects more than 32.9% of the population, with the highest rates observed in women of reproductive age in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including regions of Southeast Asia [

5,

6]. In Indonesia, the prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls ranges from 20% to 50%, posing a significant public health challenge [

7,

8]. The consequences of IDA extend beyond fatigue and weakness; they include diminished cognitive function, compromised immunity, and long-term productivity losses [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Despite the introduction of various iron supplementation programs, such as the Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFAS) initiative in Indonesia, adherence remains notably low. Several studies have shown that digital health interventions, such as mobile applications and SMS reminders, can significantly improve adherence to iron supplementation among adolescents [

13,

14]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of mobile health (mHealth) tools in improving adherence to iron supplementation. For example, Mahmoud et al. (2021) found that app-based reminders were effective in improving adherence among adolescents in rural areas, while Lassi et al. (2021) showed that mHealth interventions significantly increased adherence to supplementation among pregnant women. Previous studies have highlighted that digital health interventions, such as mobile applications and SMS reminders, can significantly enhance adherence to iron supplementation among adolescents [

13,

14]. Factors contributing to poor adherence include lack of awareness, side effects, social stigma, and insufficient follow-up mechanisms [

15,

16,

17]. Innovative strategies are therefore needed to support behavior change and ensure sustained compliance.

In recent years, mobile health (mHealth) interventions have gained attention for their potential to enhance adherence to health regimens. mHealth tools—ranging from SMS reminders to mobile apps—can deliver personalized messages, monitor user behavior, and foster continuous engagement with health programs [

13,

18,

19]. Evidence suggests that such digital tools are effective in promoting adherence to medication and micronutrient supplementation, including iron and folic acid, through timely reminders and behavioral feedback [

14,

20,

21,

22]. Adolescents, as digital natives, may respond particularly well to these platforms compared to traditional health education methods [

23,

24,

25].

Studies have demonstrated the benefits of mHealth in supporting iron intake, symptom tracking, and education, especially when these tools are designed with users’ preferences and context in mind [

26,

27]. However, the success of mHealth interventions in low-resource settings hinges on their feasibility and usability, emphasizing the need for early evaluation with intended users [

28,

29].

This study constitutes the third phase of a mixed-methods research project aimed at developing an e-Health model to improve adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) among adolescent girls. Specifically, this phase involves a feasibility study of the FRESH mobile application, a digital tool designed to provide health education, monitoring, and motivation related to IFAS consumption. The feasibility assessment was conducted through structured questionnaires administered to adolescent girls, school health teachers, and healthcare providers in Bogor City. It aimed to evaluate the application’s content quality, functionality, user interface, and overall usability. By identifying the strengths and challenges of the intervention, this study seeks to inform scalable digital health strategies for combating IDA in resource-limited settings [

30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design to assess the feasibility of the FRESH e-health application—Folates and Iron for REsilient Adolescent Girls’ Health. The feasibility domains assessed included acceptability, usability, content quality, and implementation potential. The study was conducted in Bogor City, West Java, Indonesia, an urban area with an active adolescent iron supplementation program and widespread smartphone usage among school-aged girls.

2.2. Participants

Participants were selected from three groups: (1) adolescent girls aged 15–18 years receiving weekly IFA supplementation, (2) school personnel involved in health education, and (3) local health workers managing adolescent health programs.

Eligible adolescents owned smartphones, were able to use mobile applications, and consented to participate. For adults, eligibility required direct involvement in school-based health or IFA-related activities. A total of 30 participants were enrolled: 15 adolescent girls, 10 school representatives, and 5 health workers.

2.3. The FRESH Application

The FRESH (Folates and Iron for REsilient Adolescent Girls’ Health) application is a mobile-based e-health tool developed to enhance knowledge and adherence to IFA supplementation among adolescent girls. It consists of four key features:

Educational content (videos and articles on anemia, nutrition, and adolescent health)

IFA tracking and reminders (calendar-based intake monitoring with push notifications)

Behavioral motivation tools (testimonial stories, goal setting, and achievement badges)

Interactive learning (quizzes and games reinforcing core messages)

All content was based on the national adolescent health guidelines and was validated through expert reviews and focus group discussions with target users.

2.4. Feasibility Assessment Instrument

To evaluate the application, a structured feasibility questionnaire was adapted from established mHealth evaluation frameworks. The instrument included 25 items grouped into four domains:

Acceptability (e.g., design attractiveness, ease of installation)

Usability (e.g., ease of navigation, response speed, layout clarity)

Content Quality (e.g., relevance, credibility, age-appropriateness)

Implementation Potential (e.g., perceived usefulness in school settings, integration feasibility)

Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Two open-ended questions captured additional feedback and improvement suggestions.

2.5. Data Collection

Data collection took place in February 2025. Participants were instructed to download and use the FRESH application over five days. After the usage period, they completed the feasibility questionnaire via an online survey platform (Google Forms). Supplementary interviews were conducted with school and health personnel to gather contextual insights.

2.6. Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the closed-ended questionnaire items were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and mean scores. Qualitative responses from open-ended items and interviews were thematically coded to identify common perceptions, barriers, and suggestions related to app feasibility. Integration of quantitative and qualitative data allowed for a comprehensive assessment.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia (Ref: 001/EC/FKMUI/2025). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For adolescent respondents below 18 years of age, additional parental consent was secured in compliance with national ethical standards.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

A total of 30 participants were involved in this study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1 displays the demographic breakdown of the participants involved in this study. The majority of participants were adolescent girls, aged 15–18, from diverse socio-economic backgrounds in Bogor City, Indonesia. The high proportion of smartphone users was essential for the evaluation of the FRESH application’s feasibility.

3.2. Feasibility Domain Scores

Table 2 presents the results of the feasibility assessment based on the four key domains: acceptability, usability, content quality, and implementation potential. Each domain was rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Table 2 summarizes the average scores for each feasibility domain of the FRESH application based on participants’ assessments. The high scores across all domains indicate that the application was well-received by users, particularly in terms of usability and content quality.

3.3. Key Findings from Qualitative Data

Qualitative feedback from open-ended responses and interviews provided several key insights into the application’s feasibility:

Adolescent Girls: The majority of participants reported that they found the content to be engaging and informative. Most adolescents appreciated the reminder system, stating that it helped them remember to take their IFA supplements. However, a few mentioned that the content was sometimes too detailed and could be simplified for easier understanding. Quote: “The reminders were helpful, and I liked the quizzes because I could test what I learned.”

Health Workers: Health workers generally felt that the application could enhance adherence to IFA supplementation, especially as it integrates educational content with real-time tracking. Some health workers suggested adding more interactive features, such as live chat or community forums, to further support adolescent users. Quote: “It could be a great tool for school health programs. Maybe it could include more personalized advice for the girls.”

School Representatives: Most school representatives felt the application was easy to integrate into the school’s health curriculum. However, they pointed out that internet access could be a barrier for some students in rural areas. Quote: “It’s a useful tool, but we need to ensure all students have reliable access to the internet.”

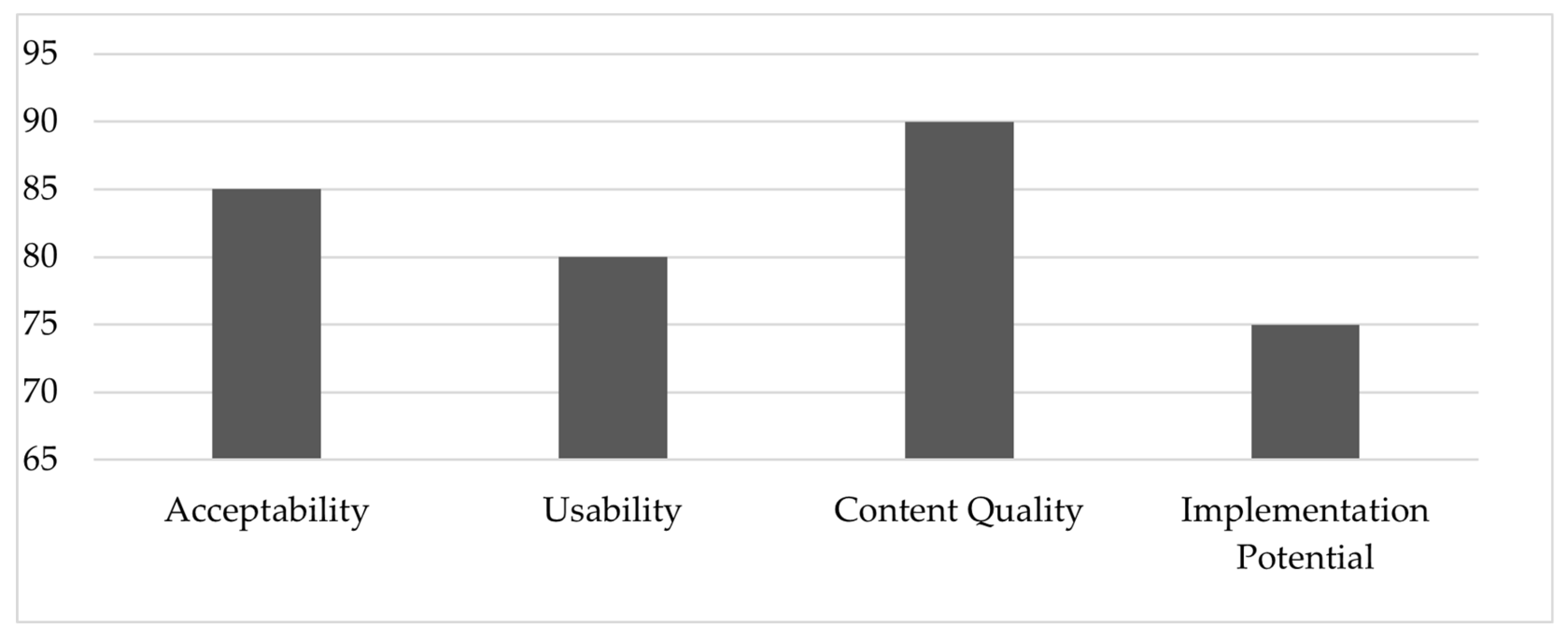

3.4. Visual Representation of Domain Scores

The following figure visualizes the average scores across the feasibility domains, demonstrating a generally positive response to the application’s features.

Figure 1 visually presents the domain feasibility scores for the FRESH application, based on participant feedback. The graph clearly shows that the application received high scores in usability and content quality, which reflects its positive reception among the users.

The results from

Table 2 and

Figure 1 show that the FRESH application was highly regarded by users, particularly in terms of usability and content quality. The data presented in the tables and figures provide a clearer understanding of the acceptance of the FRESH application among participants.

Table 2 and

Figure 1 highlight the high feasibility scores in usability and content quality, demonstrating that the application was well-received by the users.

3.5. Discussion of Key Barriers and Recommendations

Despite the FRESH application showing strong feasibility across most domains, several barriers were identified that could impact its broader implementation:

Internet Access: A recurring concern was that some adolescent girls, particularly in rural areas, may not have consistent internet access, which could limit the app’s utility. Future iterations of the application could explore offline features or data-light versions.

User Training: A few users noted that an introductory tutorial would help familiarize them with the app’s functionalities, especially the reminder system.

3.6. Summary of Feasibility

The FRESH application demonstrated high acceptability and usability among adolescent girls, school personnel, and health workers. The content was well-received, with most users expressing a positive attitude toward its potential to improve adherence to IFA supplementation. While implementation potential was slightly lower, the app’s integration into school health programs was seen as feasible with minor adjustments, particularly concerning internet access and user support.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

This study assessed the feasibility of the FRESH application—a mobile health tool designed to improve adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation among adolescent girls. The results showed that the FRESH e-health application was feasible and well-received by adolescent girls, school staff, and health workers. The mean scores for the feasibility domains—acceptability, usability, content quality, and implementation potential—were all high, with the content quality scoring the highest (3.81), indicating strong engagement with the educational materials provided.

4.2. Strengths of the FRESH Application

The high acceptability score (3.75) suggests that the application is perceived as valuable by its users. Adolescent girls, in particular, expressed positive feedback about the interactive elements, including reminders, quizzes, and educational content. These features appear to support both the understanding and retention of key health messages about iron deficiency anemia and the importance of supplementation. As highlighted by previous studies, mobile health interventions have been shown to increase adherence to health behaviors, especially when they include personalized, timely reminders and interactive elements like those integrated into

FRESH [

1].

Additionally, the usability score of 3.62 indicates that most users were able to navigate the app without difficulty. This is a critical strength, as ease of use is often a barrier in mobile health applications, especially among adolescents who may not have advanced technical skills [

2]. The integration of both educational content and user-friendly features likely contributed to the app’s success in this domain.

4.3. Challenges and Areas for Improvement

Although the feedback was mostly positive, several challenges were identified that may affect the broader implementation of the FRESH application. First, internet access emerged as a major barrier.. Although smartphone penetration is high in urban areas like Bogor, stable internet connectivity remains inconsistent in rural regions.. Although smartphone penetration is high in urban areas such as Bogor, the availability of a stable internet connection remains inconsistent in rural regions. This limitation could prevent some adolescents from fully benefiting from the app. To address this, future versions could include offline functionality or lighter data versions of the application, allowing users to access content without requiring continuous internet connectivity [

3].

Second, while the content of the application was well-received, some adolescent users expressed that the educational materials were too detailed at times, which could be overwhelming for some. Simplifying the language and structure of content, particularly for younger or less informed users, may help increase engagement and retention. Tailoring content to different literacy levels or providing more bite-sized learning modules could address this concern [

4].

4.4. Implications for Future Research and Practice

This study underscores the potential for mobile health applications like FRESH to support public health initiatives aimed at improving adolescent nutrition and supplementation adherence. The positive feedback from both users and stakeholders suggests that such applications could be effectively integrated into existing health programs, particularly those targeting iron deficiency anemia among adolescent girls.

However, further research is needed to assess the long-term effectiveness of the FRESH application in improving health outcomes, such as increased adherence to IFA supplementation and reduced rates of anemia. Future studies could also explore the scalability of the application in different geographic regions, including rural and remote areas, to ensure that its impact extends beyond urban populations. Additionally, research exploring the integration of FRESH with other public health initiatives, such as school-based health education and local health services, could provide insights into how to maximize its impact.

5. Conclusions

The FRESH application has demonstrated strong feasibility in improving adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation among adolescent girls. The positive feedback from users, including adolescents, school representatives, and health workers, highlights its potential to enhance health outcomes in this population. With high acceptability, usability, and content quality, the application presents a promising tool for addressing iron deficiency anemia in adolescent girls.

Despite challenges related to internet access and content complexity, the findings suggest that these issues can be mitigated in future versions of the application. Optimizing offline functionality and simplifying content could help the application reach a broader audience and increase its impact.

Further research is essential to assess the long-term effectiveness of the FRESH application and its scalability across various regions. If successful, FRESH could become a key component of public health programs aimed at improving adolescent nutrition and overall health.

In conclusion, the FRESH application represents a valuable innovation in mobile health technology, with significant potential to contribute to global efforts in combating iron deficiency anemia among adolescent girls.

6. Patents

This research was conducted under the supervision of the Postgraduate Program in Public Health, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta, and the Health Office of Bogor City. The FRESH mobile application developed in this study is part of an ongoing initiative aimed at improving health outcomes related to iron deficiency anemia. The work complies with intellectual property protection and ethical guidelines as set by these institutions.

Supplementary Materials

For more details, you can access the following official websites

Dinas Kesehatan Kota Bogor (Bogor Smart Health): https://dinkes.kotabogor.go.id. This website provides information about health services, healthcare facilities, recent news, and other public information managed by the Health Office of Bogor City.

Pemerintah Kota Bogor (Bogor City Government):

https://kotabogor.go.id. The official portal of the Bogor City Government, offering information on governance, public services, investments, tourism, and current news about Bogor City.

Author Contributions

For this research article, the contributions of the authors are as follows: Conceptualization: Armein Sjuhary Rowi, Ari Natalia Probandari, and Ratih Puspita Febrinasari. Methodology: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Software: Ari Natalia Probandari. Validation: Armein Sjuhary Rowi, Ari Natalia Probandari, and Ratih Puspita Febrinasari. Formal Analysis: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Investigation: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Resources: Ratih Puspita Febrinasari.Data Curation: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Writing—Review and Editing: Armein Sjuhary Rowi, Ari Natalia Probandari, and Ratih Puspita Febrinasari. Visualization: Ari Natalia Probandari. Supervision: Ratih Puspita Febrinasari. Project Administration: Armein Sjuhary Rowi. Funding Acquisition: Ratih Puspita Febrinasari. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta (protocol code 59/02/02/2024 and date of approval 25 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results can be found at [link or DOI to dataset]. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement has been included in the

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Postgraduate Program in Public Health, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta for their support and approval in conducting this research. Special thanks go to the Health Office of Bogor City for their collaboration, valuable insights, and guidance in ensuring the relevance and impact of the FRESH mobile application in addressing iron deficiency anemia among adolescents. We also extend our appreciation to the Puskesmas (Community Health Centers) for their involvement in facilitating the project and supporting the implementation of the intervention. Our deepest thanks go to the schools for their cooperation in recruiting participants and providing the necessary environment for this research. We also acknowledge the parents who entrusted us with their children’s participation and provided the essential support for the adolescent girls throughout the study. Lastly, we would like to thank the adolescent girls who participated in the testing phase of the app. Their feedback and insights were invaluable in refining the application and ensuring its effectiveness in promoting adherence to iron supplementation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Form |

| FRESH |

Folates and Iron for REsilient Adolescent Girls’ Health.Mobile application for Iron Supplementation adherence |

| ID |

Iron deficiency |

| TTD |

Tablet Tambah Darah (Iron Supplement) |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| mHealth |

Mobile Health |

| Puskesmas |

Community Health Centers |

References

- Kumar A, Gupta S, Meena NK, Yadav A. Iron deficiency anaemia: pathophysiology, assessment, clinical implications and challenges. J Transl Int Med. 2022, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann MB, Hurrell RF. Nutritional iron deficiency. Lancet. 2020, 395, 320–332. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S. Iron metabolism and its disorders. In: Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 12th ed. Wolters Kluwer;

- Harding KL, Aguayo VM, Webb P. Hidden hunger in South Asia: a review of recent trends and persistent challenges. Public Heal Nutr. 2020, 23, S1–S15. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, WH. Anaemia [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2025 May 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

- Petry N, Olofin I, Hurrell RF, Boy E, Wirth JP, Moursi M, et al. The proportion of anemia associated with iron deficiency in low, medium, and high human development index countries: a systematic analysis of national surveys. Nutrients 2018, 8, 693. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry SK, Hossain MB, Arora A, Yadav UN, Majeed A. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia among adolescents in LMICs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2022, 80, 988–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav RK, Chand R. Iron-deficiency anemia among adolescent girls in South Asia: a neglected public health issue. Int J Adolesc Med Heal. 2019, 31, 20180078. [Google Scholar]

- Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018, 23, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG, Mayers DR. Early child growth: how do nutrition and infection interact? Matern Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13057. [Google Scholar]

- Horton S, Ross J. The economics of iron deficiency. Food Policy. 2020, 64, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Camaschella, C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2019, 372, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud AS, Farag HH. The role of mHealth applications in promoting iron supplementation among adolescents. J Adolesc Heal. 2021, 68, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Lassi ZS, Moin A, Bhutta ZA. Nutrition interventions in adolescent girls and women of reproductive age: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2730. [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Shankar AH, Wu LS-F. Trials of iron supplementation and risk of infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Heal. 2022, 7, e007627.

- Prieto-Patron A, van der Horst K, Hutton Z V. Factors associated with adherence to iron-folic acid supplementation among women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021, 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D. Iron supplementation in children: a narrative review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020, 111, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Singh T, Kumar R. Effectiveness of mobile health interventions on health behaviors in adolescents: a systematic review. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Luzuriaga MJ, Neufeld LM, García-Guerra A. mHealth intervention increases adherence to micronutrient supplements among adolescent girls in Guatemala. J Nutr. 2020, 150, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Sato APS, Fujimori E, Borges AL V. Mobile applications for iron supplementation adherence in adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021, 24, e210020. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry SK, Arora A, Das Gupta R. Use of mobile phones and digital health interventions to improve adolescent nutrition: a global systematic review. Glob Heal Action. 2022, 15, 2051042. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira D, Oliveira A, Santos F. Impact of mHealth reminders on adherence to iron-folic acid supplementation: a cluster trial in rural adolescents. Heal Technol. 2019, 9, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Akseer N, Wright J, Tasic H. Adolescents’ digital engagement and opportunities for promoting health. J Adolesc Heal. 2020, 66, S12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Badurdeen F, Abdul Majeed N, Chandrasekharan A. Adolescent-centered approaches to digital health interventions: a global review. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020, 4, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Yousafzai AK, Rasheed MA, Rizvi A. Digital tools for enhancing adolescent health education in South Asia: challenges and innovations. Asia Pac J Public Heal. 2019, 31, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, Cacault MP, Gallay A. Digital delivery of health interventions for adolescents: design matters. J Adolesc Heal. 2019, 65, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha SR, Tye-Din J, Muckenthaler MU, Swinkels DW. Iron deficiency. Lancet. 2021, 397, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz M, Villar I, García-Erce JA. Challenges in implementing mHealth-based anemia screening programs in low-resource settings. Blood Transfus. 2021, 19, 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. Health system integration of mHealth tools for anemia control: policy and feasibility. Blood. 2020, 136, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar]

- de-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP, Garcia-Casal MN, Centeno TA. Development of evidence-informed WHO guidelines for micronutrient interventions: iron and folic acid. J Nutr. 2019, 149, 7S–12S. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).