Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Ethical approval

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

| Muslim (n = 884) | Jewish (n = 916) | Difference test | |||||

| Path | Sig. | Sig. | Z-scores | ||||

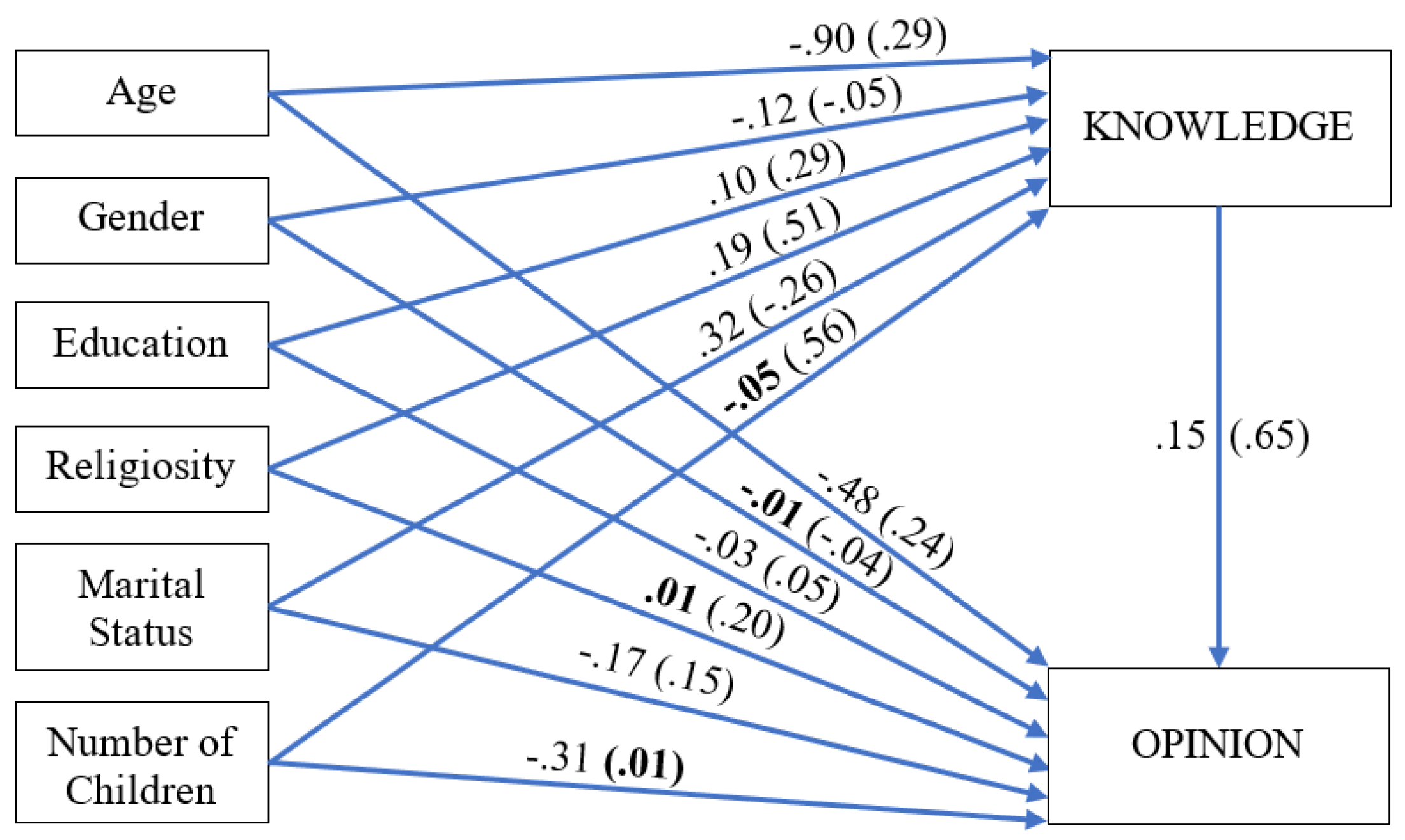

| Age | → | KNOWLEDGE | -.90 | .000 | .29 | .000 | 19.07*** |

| Gender | → | KNOWLEDGE | -.12 | .000 | -.05 | .000 | 2.37** |

| Education | → | KNOWLEDGE | .10 | .000 | .29 | .000 | 6.02*** |

| Religiosity | → | KNOWLEDGE | .19 | .000 | .51 | .000 | 8.99*** |

| Marital Status | → | KNOWLEDGE | .32 | .000 | -.26 | .000 | 17.26*** |

| Children | → | KNOWLEDGE | -.05 | .282 | .56 | .000 | 8.97*** |

| Age | → | OPINION | -.48 | .000 | .24 | .000 | 21.97*** |

| Gender | → | OPINION | -.01 | .186 | -.04 | .000 | 1.97** |

| Education | → | OPINION | -.03 | .000 | .05 | .000 | 5.17*** |

| Religiosity | → | OPINION | .01 | .718 | .20 | .000 | 9.77*** |

| Marital Status | → | OPINION | -.17 | .000 | .15 | .000 | 18.30*** |

| Children | → | OPINION | -.31 | .000 | .01 | .848 | 10.31*** |

| Knowledge | → | OPINION | .15 | .000 | .65 | .000 | 19.46*** |

| Muslim (n = 809) | Jewish (n = 714) | |||||||||||

| Path | Eff. | LL | UL | Sig. | Eff. | LL | UL | Sig. | ||||

| Age | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | -.13 | -.19 | -.09 | .001 | .19 | .14 | .25 | .000 |

| Gender | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | -.02 | -.03 | -.01 | .000 | -.03 | -.06 | -.01 | .020 |

| Education | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | .02 | .01 | .03 | .000 | .19 | .15 | .22 | .000 |

| Religiosity | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | .03 | .02 | .04 | .000 | .33 | .30 | .37 | .000 |

| Marital Status | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | .05 | .03 | .07 | .000 | -.17 | -.21 | -.13 | .000 |

| Children | → | KNOWLEDGE | → | OPINION | -.01 | -.02 | .01 | .321 | .38 | .30 | .43 | .001 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Correspondence

Appendix A. Informed Consent Form for Online Studies

- Part I: Informed Consent Form for Online Studies

- Greetings,

- You are invited to participate in a study examining patient knowledge and attitudes towards donating organs that are produced from a pig in the Jewish and Islamic religions. This study was conducted by researchers at the School of Nursing Sciences, Tel Aviv-Jaffa Academic College. We thank you for dedicating your time and participating in the study.

- The primary aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge among Muslim and Jewish individuals regarding religious rulings that allow the use of porcine organs in life-saving situations. Additionally, the study sought to evaluate participants’ personal attitudes toward the permissibility of such transplants within their religious and cultural frameworks.

- The time required to fill out the questionnaire is about 15 minutes. The questionnaire is anonymous and will be filled out anonymously, your answers are completely confidential, and will not be used in any way except for research purposes.

- In this questionnaire, you will be presented with several different questions regarding the effect of treatments on the quality of life and emotional reactions of transplant recipients. You are asked to mark the correct answer next to each question.

- You do not have to answer all the questions. If you feel uncomfortable, you may stop filling out the questionnaire at any stage.

- By agreeing to fill out this questionnaire, you declare that you are over 18 years old.

- It is assumed that participating in the research will not bring you any personal profit or advantage, but we hope that your participation will contribute to general knowledge in this research field.

- It should be noted that we are not aware of any risks by participating in the study, but as with any online activity there is a certain risk of breach of privacy. We make every effort to reduce this risk by have the questionnaire filled out anonymously and not using the details except for the purpose of the study.

- At the end of the study, you can get more information from the Ethics Committee of the Tel Aviv-Jaffa Academic College using the Debriefing form. In addition, you can contact the research team by email:

- We thank you very much for filling out the questionnaires in full.

- Sincerely yours,

- Dr. Mahdi Tarabia

- mahdita@mat.ac.il

- By clicking the "I agree" button, you express your consent to participate in the study. By clicking on the "I do not agree" button, you terminate your participation in the study.

Appendix B. The research questionnaire

- - Age (in years):

- 2- Gender: 1 - Male 2- Female

- 3- Education: 1. Academic 2. Non-academic

- 4- Religion: 1. Muslim 2. Jew

- 5- Level of religiosity: 1- Religious, 2- Secular

- 6- Family status: 1. In a relationship 2. Not in a relationship

- 7. Number of children…….

- The first part of the questionnaire presents you with a number of medical treatment scenarios. Please indicate, to the best of your knowledge, to what extent Jewish/Islamic religion allows medical treatment as described in the scenario:

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always permitted |

6 It is totally 100% permitted |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always almost permitted |

6 It is totally (100%) permitted ` |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always almost permitted |

6 It is totally 100% permitted ` |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always almost permitted |

6 It is totally 100% permitted ` |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always almost permitted |

6 It is totally 100% permitted ` |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 It is 100% forbidden |

2 It is almost always forbidden |

3 It is permitted infrequently |

4 It is permitted in exceptional cases |

5 It is always almost permitted |

6 It is totally 100% permitted ` |

7 I don’t know |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

| 1 Totally disagree |

2 Disagree somewhat |

3 Agree slightly |

4 Agree moderately |

5 Agree to a large extent |

6 Agree strongly |

7 Totally agree |

References

- Worldometers.info. Current World Population. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Padela, A.I.; Auda, J. The Moral Status of Organ Donation and Transplantation within Islamic Law: The Fiqh Council of North America's Position. Transplant. Direct. 2020, 6, e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, W.; Seidler, R.J.H.; FitzGerald, K.; Padela, A.I.; Cozzi, E.; Cooper, D.K.C. Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Theological Perspectives about Xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation 2018, 25, e12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Syahadah binti Mod Ali, S.; Gunardi, S. Porcine DNA in Medicine toward Postpartum Patients from Medical and Islamic Perspectives in Malaysia. Int. J. Halal Res. 2021, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritsugu, K.P.; Transplant Patients Need Hope—Not Waiting Lists—and Science May Finally Catch Up. Real Clear Policy [website] 2022, 30 November. Available online: https://www.realclearpolicy.com /2022/12/01/transplant_patients_need_hope_not_waiting_lists_867797.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Mohiuddin, M.M.; Reichart, B.; Byrne, G.W.; McGregor, C.G.A. Current Status of Pig Heart Xenotransplantation. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 23 (Pt B), 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.K.C. A Brief History of Cross-Species Organ Transplantation. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2012, 25, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; He, W.; Ruan, Y.; Geng, Q. First Pig-to-Human Heart Transplantation. Innovation (Camb.). 2022, 3, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, S. First Pig-to-Human Heart Transplant: What Can Scientists Learn? Nature. 2022, 601, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, R.N., 3rd; Burdorf, L.; Madsen, J.C.; Lewis, G.D.; D'Alessandro, D.A. Pig-to-Human Heart Transplantation: Who Goes First? Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 2669–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisseeff, J.; Badylak, S.F.; Boeke, J.D. Immune and Genome Engineering as the Future of Transplantable Tissue. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2451–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J.E.; Kumar, V.; Anderson, D.; Porrett, P.M. Normal Graft Function after Pig-to-Human Kidney Xenotransplant. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 1106–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrett, P.M.; Orandi, B.J.; Kumar, V.; et al. First Clinical-Grade Porcine Kidney Xenotransplant Using a Human Decedent Model. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.A.; Stern, J.M.; Lonze, B.E.; et al. Results of Two Cases of Pig-to-Human Kidney Xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godehardt, A.W.; Tönjes, R.R. Xenotransplantation of Decellularized Pig Heart Valves—Regulatory Aspects in Europe. Xenotransplantation 2020, 27, e12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, E.D.; Yip, M.; Melman, L.; Frisella, M.M.; Matthews, B.D. Informed Consent: Cultural and Religious Issues Associated with the Use of Allogeneic and Xenogeneic Mesh Products. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 210, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, A.I.; Duivenbode, R. The Ethics of Organ Donation, Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death, and Xenotransplantation from an Islamic Perspective. Xenotransplantation 2018, 25, e12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, M.D.; Canova, D.; Rumiati, R.; et al. Understanding of and Attitudes to Xenotransplantation: A Survey among Italian University Students. Xenotransplantation 2004, 11, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, L.A.; Hurst, D.; Lopez, R.; Kumar, V.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Paris, W. Attitudes to clinical pig kidney xenotransplantation among medical providers and patients. Kidney360 2020, 1, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Burcharth, J.; Rosenberg, J. Animal Derived Products May Conflict with Religious Patients’ Beliefs. BMC Med. Ethics 2013, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, K.C.; Patel, K.P. Suitability of Common Drugs for Patients Who Avoid Animal Products. BMJ 2014, 348, g401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, H.M.R.; Khan, T.H. Religious Belief as Determinant of Animal Derived Medications in Health Care: How Much Is Fairly Good? Anaesth. Pain Intensive Care 2018, 22, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, A.; Hossain, M.; Barla, C. Toward Comprehensive Medicine: Listening to Spiritual and Religious Needs of Patients. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 5, 2333721419843703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babos, M.B.; Perry, J.D.; Reed, S.A.; et al. Animal-Derived Medications: Cultural Considerations and Available Alternatives. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 121, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, D.; Goyal, A.; Brittberg, M. Consideration of Religious Sentiments While Selecting a Biological Product for Knee Arthroscopy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiwani, M.H. The Use of Porcine Mesh Implants in the Repair of Abdominal Wall Hernia: An Islamic Perspective for an Informed Consent. J. Br. Islam. Med. Assoc. 2020, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, H.L.; Blome-Eberwein, S.E.; Branski, L.K.; et al. Porcine Xenograft and Epidermal Fully Synthetic Skin Substitutes in the Treatment of Partial-Thickness Burns: A Literature Review. Medicina 2021, 57, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, A.; Firas, A.; Hazim, R. The Use of Porcine Bioprosthetic Valves: An Islamic Perspective and a Bio-Ethical Discussion. J. Br. Islam. Med. Assoc. 2020, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Padela, A.I.; Furber, S.W.; Kholwadia, M.A.; Moosa, E. Dire Necessity and Transformation: Entry-Points for Modern Science in Islamic Bioethical Assessment of Porcine Products in Vaccines. Bioethics 2014, 28, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manji, R.A.; Menkis, A.H.; Ekser, B.; Cooper, D.K. Porcine Bioprosthetic Heart Valves: The Next Generation. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Iwase, H.; King, T.W.; Hara, H.; Cooper, D.K.C. Skin Xenotransplantation: Historical Review and Clinical Potential. Burns 2018, 44, 1738–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommaggio, R.; Uribe-Herranz, M.; Marquina, M.; Costa, C. Xenotransplantation of Pig Chondrocytes: Therapeutic Potential and Barriers for Cartilage Repair. Eur. Cell Mater. 2016, 32, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Tarabeih, M. The Use of Porcine-Derived Materials for Medical Purposes: What Do Muslim and Jewish Individuals Know and Opine about It? J. Bioeth. Inq. 2022, 19, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger, D. Why We Should Stop Using Animal-Derived Products on Patients without Their Consent. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 47, medethics–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, D.; Blackshaw, B.P. Using Animal-Derived Constituents in Anaesthesia and Surgery: The Case for Disclosing to Patients. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, N. ; Jolly, K.; Darr, A.; Bowyer, D.J.; Ahmed, S.K. Intra-Operative Use of Biological Products—Are We Aware of Their Derivatives? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, C.; Maddern, G. Porcine and Bovine Surgical Products: Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu Perspectives. Arch. Surg. 2008, 143, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.P.; Shakeel Ahmed, M.; Majeed, F.; Petty, F. Inert Medication Ingredients Causing Nonadherence Due to Religious Beliefs. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vissamsetti, B.; Payne, M.; Payne, S. Inadvertent Prescription of Gelatin-Containing Oral Medication: Its Acceptability to Patients. Postgrad. Med. J. 2012, 88, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, K.; Darr, A.; Aslanidou, A.; Bowyer, D.; Ahmed, S. The Intra-Operative Use of Biological Products: A Multi-Centre Regional Patient Perspective of a Potential Consenting Conundrum. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2019, 44, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat, K.M.; Pirzadeh, R. Issues in Islamic Biomedical Ethics: A Primer for the Pediatrician. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Branden, S.; Broeckaert, B. The Ongoing Charity of Organ Donation: Contemporary English Sunni Fatwas on Organ Donation and Blood Transfusion. Bioethics 2011, 25, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daar, A.S.; Al Khitamy, A.B. Bioethics for Clinicians: 21. Islamic Bioethics. CMAJ 2001, 164, 60–63 https://wwwcmajca/content/164/1/60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bokek-Cohen, Y. The Need to Adjust the Informed Consent for Jewish Patients for Treatments Involving Porcine Medical Constituents. J. Immigr. Minor Health 2023, 25, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, E.R.; Adams, W.A. Reconciling Private Benefit and Public Risk in Biotechnology: Xenotransplantation as a Case Study in Consent. Health Law J. 2002, 10, 31–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dorff, E.N. End-of-Life: Jewish Perspectives. Lancet 2005, 366, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabeih, M.; Amiel, A.; Na'amnih, W. The View of the Three Monotheistic Religions toward Xenotransplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2024, 38, e15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loike, J.D.; Kadish, A. Ethical Rejections of Xenotransplantation? The Potential and Challenges of Using Human-Pig Chimeras to Create Organs for Transplantation. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e46337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, E. Medicine and Shariah: A Dialogue in Islamic Bioethics; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fadel, H. The Islamic Viewpoint on New Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Fordham Urban Law J. 2002, 30, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Fadel, H. Prospects and Ethics of Stem Cell Research: An Islamic Perspective. J. Islamic Med. Assoc. North America 2007, 39, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, H. Developments in Stem Cell Research and Therapeutic Cloning: Islamic Ethical Positions, A Review. Bioethics 2012, 26, 128–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zuhayli, W. al-Fiqh al-Islami wa-Adillatuh; Dar al-Fikr: Damascus, Syria, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Musarrat Nawaz, M. An Exploration of Students' Knowledge and Understanding of Istihalah. J. Islamic Marketing 2016, 7, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, M.A. Fiqh Istihala: Integration of Science and Islamic Law. Revelation and Science 2012, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, D.J.; Padilla, L.A.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Paris, W. Factors Influencing Attitudes Toward Xenotransplantation Clinical Trials: A Report of Focus Group Studies. Xenotransplantation 2021, 28, e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enoch, S.; Shaaban, H.; Dunn, K.W. Informed Consent Should Be Obtained from Patients to Use Products (Skin Substitutes) and Dressings Containing Biological Material. J. Med. Ethics 2005, 31, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelin, J.; Hau, J.; Schapiro, S.J.; Suleman, M.A.; Carlsson, H.E. Religious Beliefs and Opinions on Clinical Xenotransplantation–A Survey of University Students from Kenya, Sweden and Texas. Clin. Transplant. 2001, 15, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Abu-Rakia, R.; Azuri, P.; Tarabeih, M. The View of the Three Monotheistic Religions Toward Cadaveric Organ Donation. Omega (Westport) 2022, 85, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelin, J. Public Opinion Surveys about Xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation 2004, 11, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.P.; Ahmed, M.S.; Madison, J.; et al. Patient and Physician Attitudes to Using Medications with Religiously Forbidden Ingredients. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, L.W.; Kerssens, C.; Ijzermans, J.N.; Zuidema, W.; Weimar, W.; Busschbach, J.J. Reluctant Acceptance of Xenotransplantation in Kidney Patients on the Waiting List for Transplantation. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 61, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, F. Pig Organs for Transplantation into Humans: A Jewish View. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 1999, 66, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loike, J.D.; Krupka, R.M. The Jewish Perspectives on Xenotransplantation. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2023, 14, e0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, M. 1895-1986 Igros Moshe, Yore Deah, 229 and 230; Beth Medrash L’Torah V’Horaah: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zilberstein, Y. Shiurei Torah laRofim. II; Maimonides Research Institute: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J. Three Ethical Issues Around Pig Heart Transplants. BBC News, /: Jan 11. [Accessed , 2023]. Available online: https, 21 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Population of Israel on the Eve of 2024. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Julvez, J.; Tuppin, P.; Cardoso, J.; Borsarelli, J.; Cohen, S.; Jouan, M.C. Population and Xenograft Investigation. Preliminary Results. Pathol. Biol. 2000, 48, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabeih, M.; Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Azuri, P. Health-Related Quality of Life of Transplant Recipients: A Comparison Between Lung, Kidney, Heart, and Liver Recipients. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curlin, F.A.; Roach, C.J.; Gorawara-Bhat, R. When Patients Choose Faith over Medicine: Physician Perspectives on Religiously Related Conflict in the Medical Encounter. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebner, K.; Ostheimer, J.; Sautermeister, J. The Role of Religious Beliefs for the Acceptance of Xenotransplantation: Exploring Dimensions of Xenotransplantation in the Field of Hospital Chaplaincy. Xenotransplantation 2020, 27, e12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Gonen, L.D.; Tarabeih, M. The Muslim Patient and Medical Treatments Based on Porcine Ingredients. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Ravitsky, V. Cultural and Personal Considerations in Informed Consent for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Am. J. Bioethics 2017, 17, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapaty, S.; Kozlov, M. First Pig Kidney Transplant in a Person: What It Means for the Future. Nature 2024, 628, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Nm (Nj) | %m (%j) | Mm (Mj) | SDm (SDj) | Rm (Rj) |

| Gender | Male | 427 (457) | 48.3 (49.9) | - | - | - |

| Female | 457 (459) | 51.7 (50.1) | - | - | - | |

| Education | Not academic | 439 (435) | 49.7 (47.5) | - | - | - |

| Academic | 445 (481) | 50.3 (52.5) | - | - | - | |

| Religiosity | Secular | 402 (450) | 45.5 (49.1) | - | - | - |

| Religious | 482 (466) | 54.5 (50.9) | - | - | - | |

| Marital Status | No relationship | 86 (157) | 9.7 (17.1) | - | - | - |

| In a relationship | 798 (759) | 90.3 (82.9) | - | - | - | |

| Age | - | - | 49.41 (51.13) | 20.43 (20.78) | 18-81 | |

| Children | - | - | 4.43 (3.96) | 2.84 (2.73) | 0-13 (0-10) |

| Jewish (n = 916) | Muslim (n = 884) | ||||||||

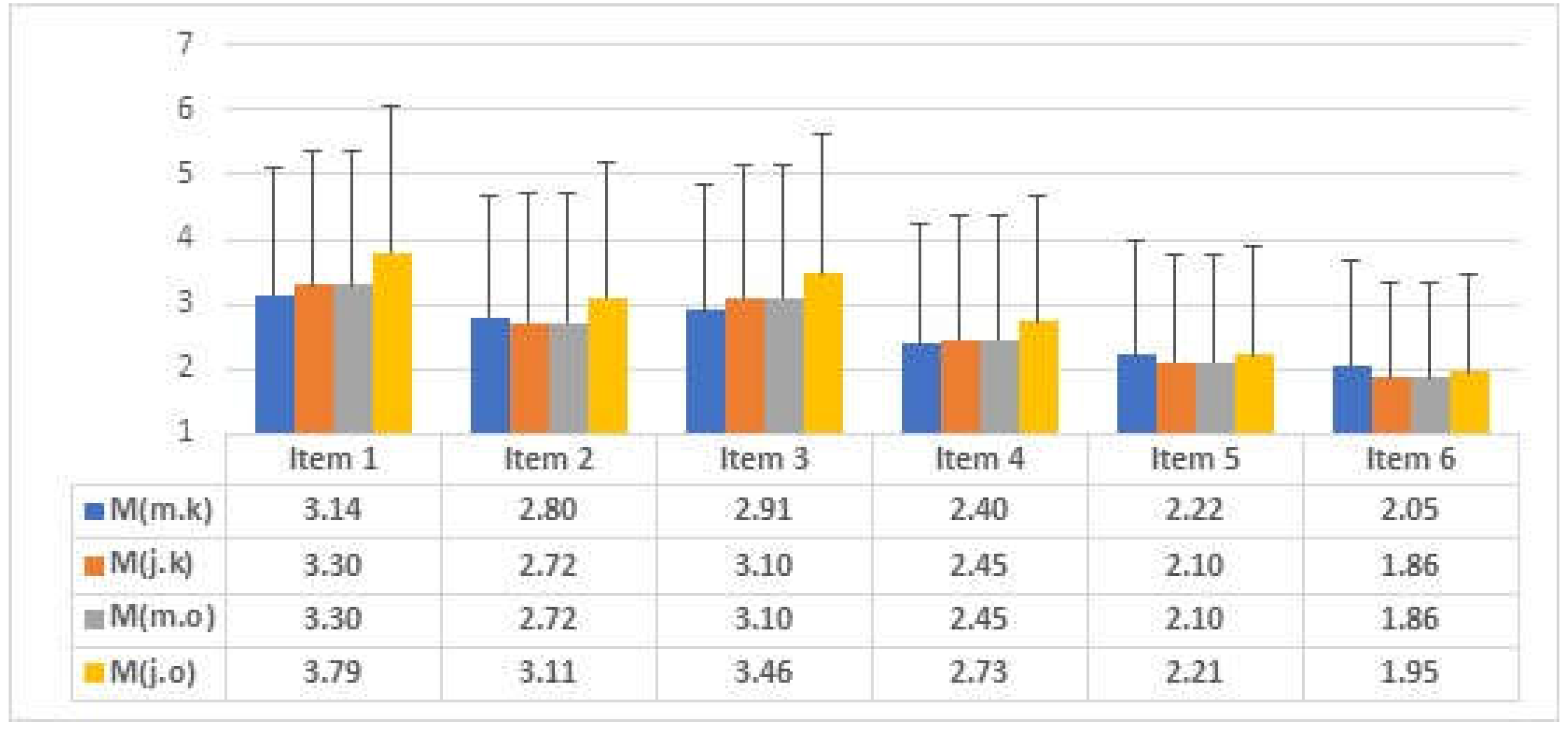

| Item | Mk (Mo) | SDk (SDo) | rp | Mk (Mo) | SDk (SDo) | rp | Fisher’s Z | ||

| 1. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to transplant a heart or a heart valve taken from a pig into a patient suffering from a heart problem whose life is in danger? | 3.14 (3.30) | 1.95 (2.06) | .92 | 3.30 (3.79) | 2.06 (2.28) | .96 | 7.56*** | ||

| 2. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to do a lung transplant in a patient suffering from severe obstructive pulmonary disease, using a lung taken from a pig? | 2.80 (2.72) | 1.88 (1.97) | .95 | 2.72 (3.11) | 1.97 (2.09) | .96 | 2.42* | ||

| 3. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to do a kidney transplant in a patient suffering from severe renal insufficiency using a kidney taken from a pig? | 2.91 (3.10) | 1.94 (2.04) | .96 | 3.10 (3.46) | 2.04 (2.17) | .93 | 6.09*** | ||

| 4. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to treat a patient who is in danger of death from pancreatic insufficiency by doing a transplant of a pancreas/pancreatic cells taken from a pig? | 2.40 (2.45) | 1.82 (1.92) | .94 | 2.45 (2.73) | 1.92 (1.94) | .95 | 1.98* | ||

| 5. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to implant in a patient’s knee cartilage taken from a pig, in order to replace worn cartilage? | 2.22 (2.10) | 1.74 (1.66) | .88 | 2.10 (2.21) | 1.66 (1.68) | .96 | 12.07*** | ||

| 6. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to use skin tissue of a pig to do a skin graft in a patient with serious burn injuries? | 2.05 (1.86) | 1.65 (1.46) | .79 | 1.86 (1.95) | 1.46 (1.50) | .95 | 16.10*** | ||

| KNOWLEDGE items | OPINION items | |||||

| Item | Mm (Mj) | SDm (SDj) | t-test | Mm (Mj) | SDm (SDj) | t-test |

| 1. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to transplant a heart or a heart valve taken from a pig into a patient suffering from a heart problem whose life is in danger? | 3.14 (3.30) | 1.95 (2.06) | 1.58 | 3.81 (3.79) | 2.51 (2.28) | 0.12 |

| 2. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to do a lung transplant in a patient suffering from severe obstructive pulmonary disease, using a lung taken from a pig? | 2.80 (2.72) | 1.88 (1.97) | 0.78 | 3.45 (3.11) | 2.49 (2.09) | 3.09*** |

| 3. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to do a kidney transplant in a patient suffering from severe renal insufficiency using a kidney taken from a pig? | 2.91 (3.10) | 1.94 (2.04) | 1.84* | 3.55 (3.46) | 2.53 (2.17) | 0.85 |

| 4. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to treat a patient who is in danger of death from pancreatic insufficiency by doing a transplant of a pancreas/pancreatic cells taken from a pig? | 2.40 (2.45) | 1.82 (1.92) | 0.61 | 2.82 (2.73) | 2.35 (1.94) | 0.94 |

| 5. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to implant in a patient’s knee cartilage taken from a pig, in order to replace worn cartilage? | 2.22 (2.10) | 1.74 (1.66) | 1.41 | 2.47 (2.21) | 2.18 (1.68) | 2.84** |

| 6. Is it permitted according to the Jewish/Islamic religion to use skin tissue of a pig to do a skin graft in a patient with serious burn injuries? | 2.05 (1.86) | 1.65 (1.46) | 2.38** | 2.13 (1.95) | 1.95 (1.50) | 2.29** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|

- | -.02 | .06 | .02 | .63*** | .83*** | .62*** | .75*** |

|

.02 | - | -.01 | .01 | .13*** | .10*** | -.03 | -.05 |

|

.01 | .00 | - | .01 | -.01 | -.19*** | .21*** | .19*** |

|

.07* | -.04 | .02 | - | -.11** | -.27*** | .39*** | .44*** |

|

.47*** | .13*** | -.11*** | -.03 | - | .65*** | .22*** | .43*** |

|

.79*** | .06 | -.24*** | -.33*** | .51*** | - | .44*** | .52*** |

|

-.77*** | -.10** | .08* | .14*** | -.15*** | -.68*** | - | .93*** |

|

-.92*** | -.08* | .07* | .10** | -.57*** | -.87*** | .75*** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).