Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

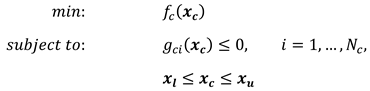

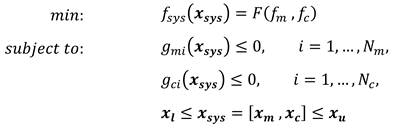

1. Introduction

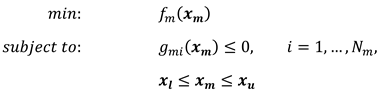

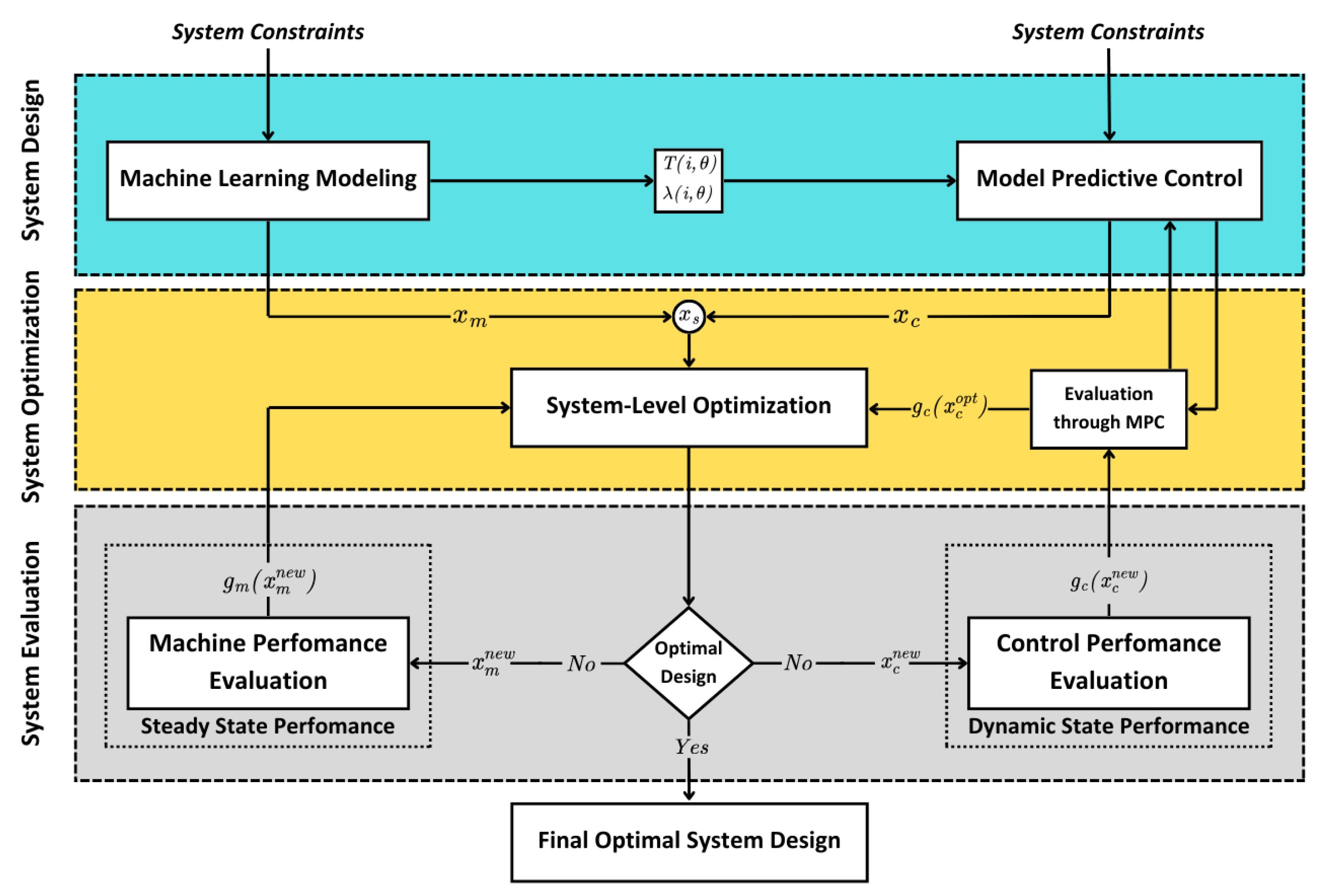

2. System-Level Design Optimization

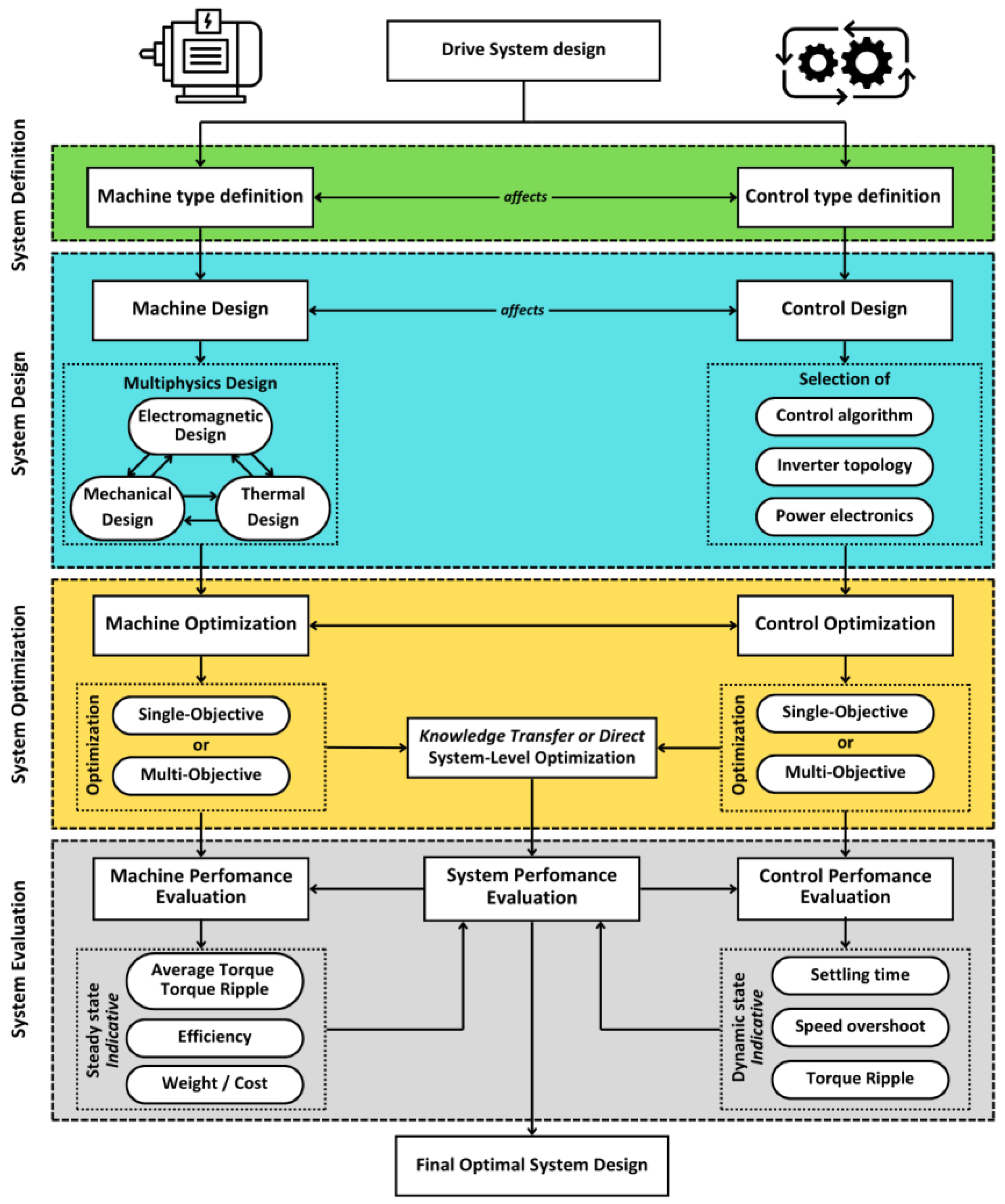

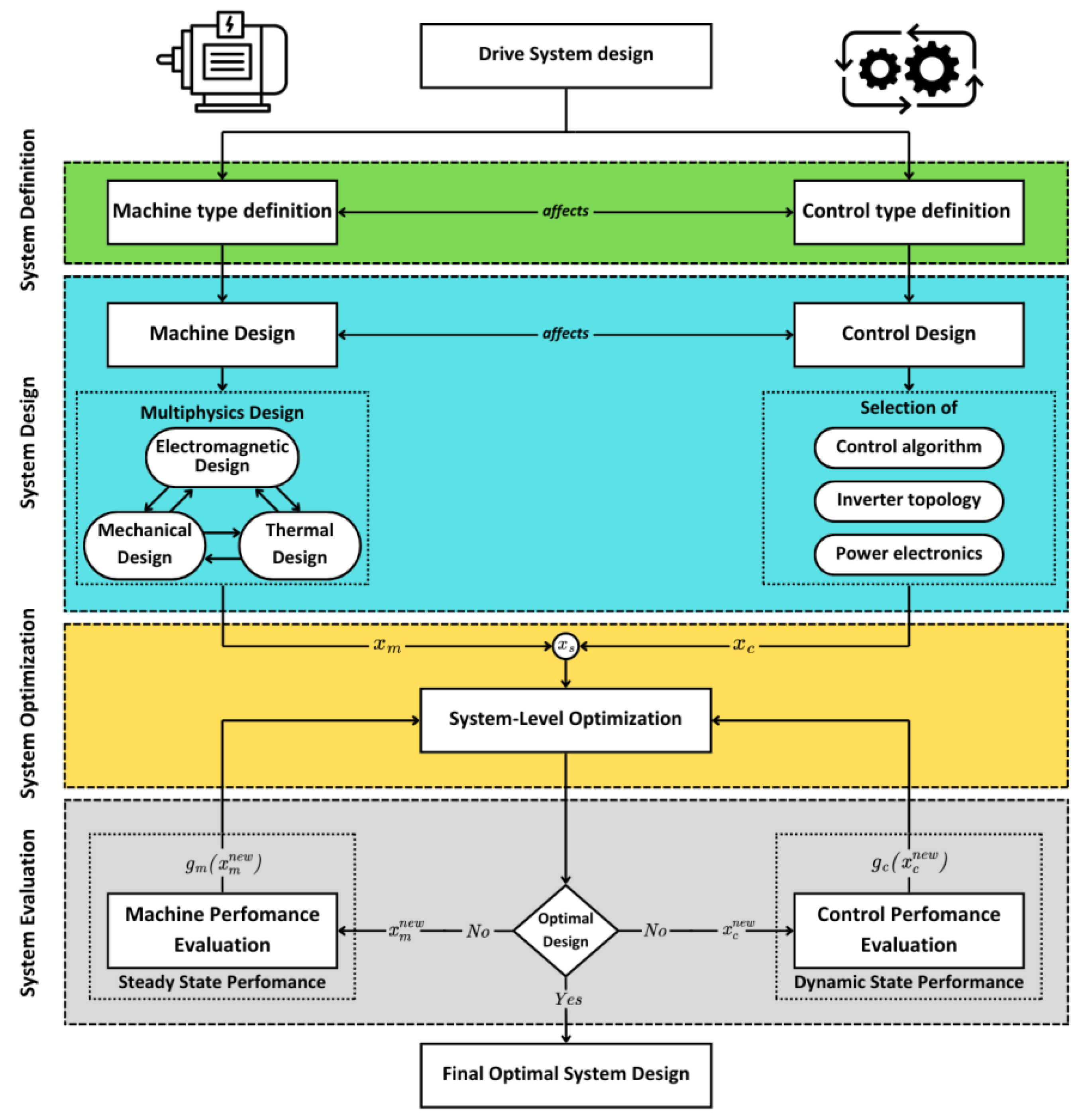

2.1. Methodology and Framework

- At steady state, the evaluation focuses on the machine’s performance, including efficiency, weight, average torque, and cost.

- At dynamic state, the evaluation examines the performance of the controller and the overall drive system, considering factors such as speed overshoot, settling time, torque ripple, and system cost.

System-Level Optimization Methods

2.2.1. Single-Level Optimization Method

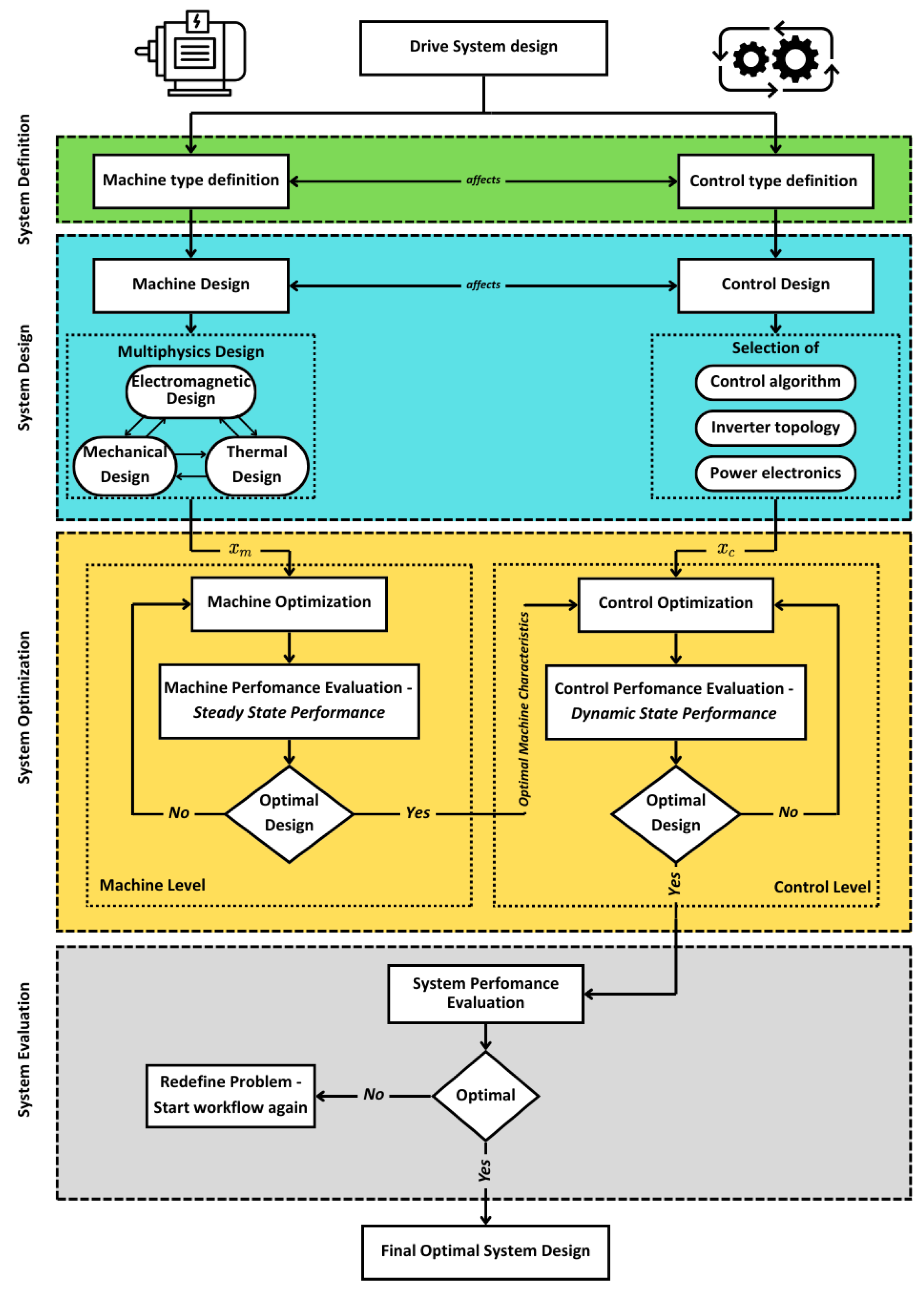

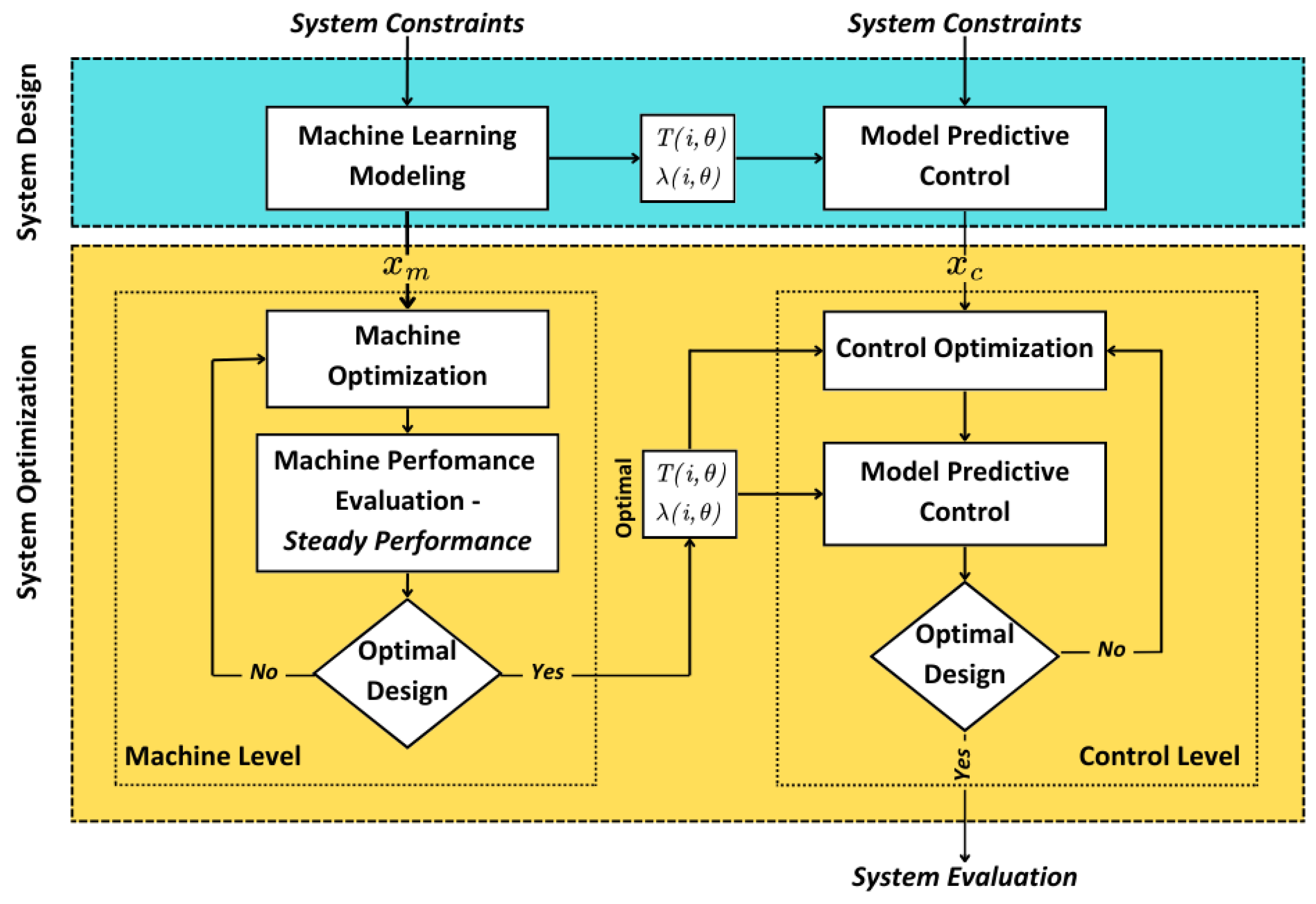

2.2.2. Multi-Level Optimization Method

- 3.

- Machine Level: Design optimization is carried out for the machine, and the steady-state performance of the machine is evaluated, including efficiency, weight, average torque, and cost. Key machine parameters, such as resistance, flux linkage, and inductance, are then passed on to the next step to be used as inputs at the control level.

- 4.

- Control Level: At this level, optimization of the controller is performed based on the output parameters from the previous level. The dynamic performance of the drive system is then evaluated, focusing on speed overshoot, settling time, and torque ripple.

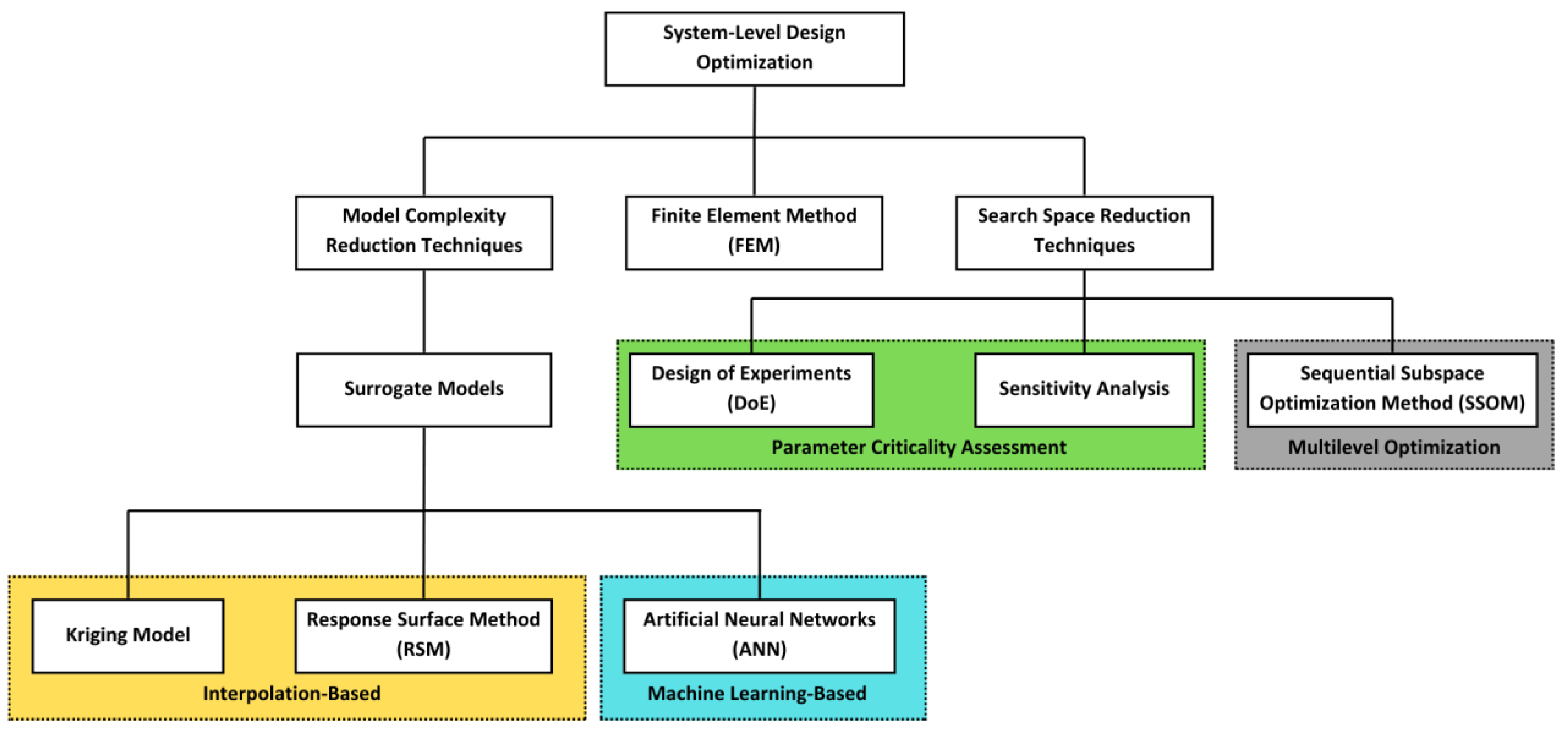

3. Model Complexity and Space Reduction Techniques for System-Level Optimization

3.1. Surrogate Modeling

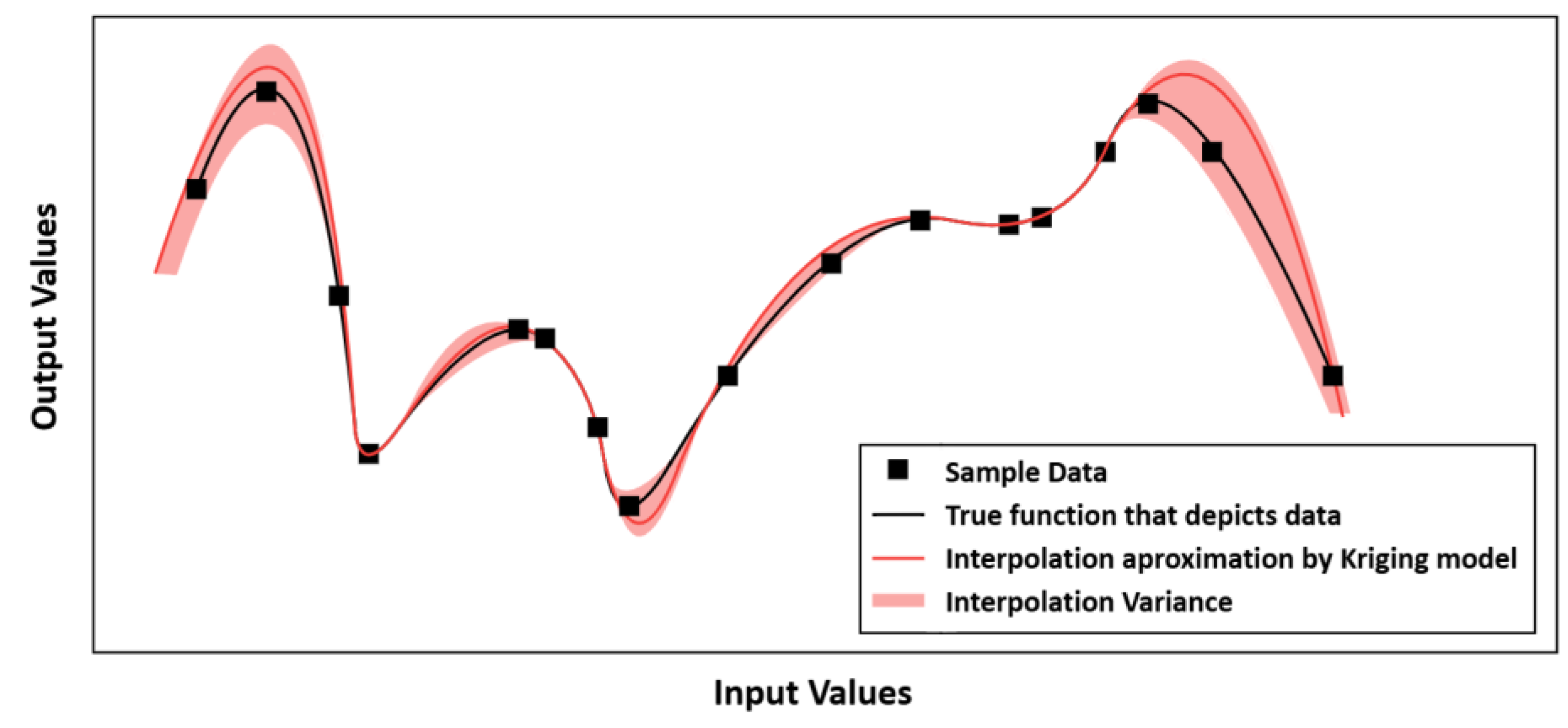

3.1.1. Kriging Model

3.1.2. Response Surface Method

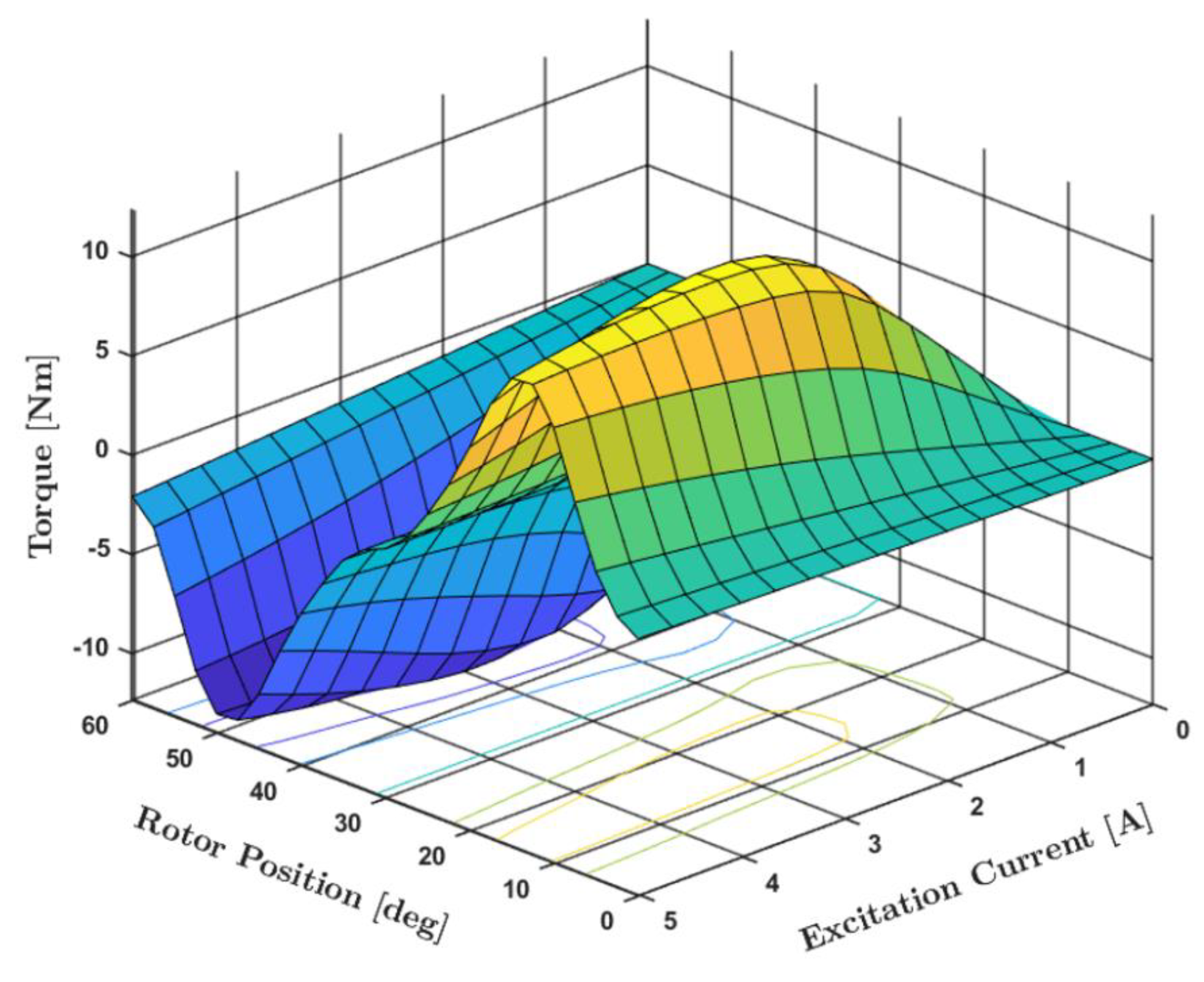

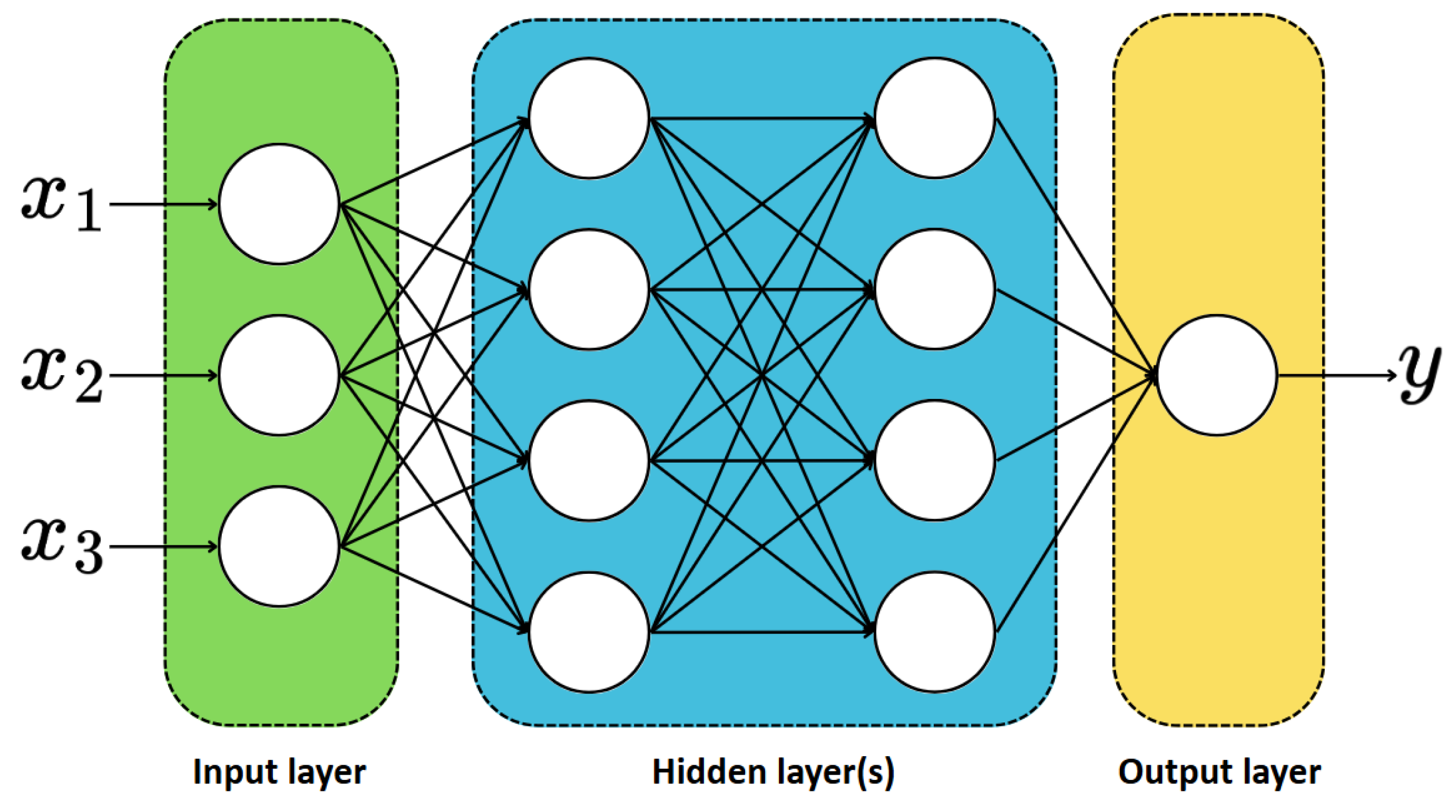

3.1.3. Artificial Neural Networks

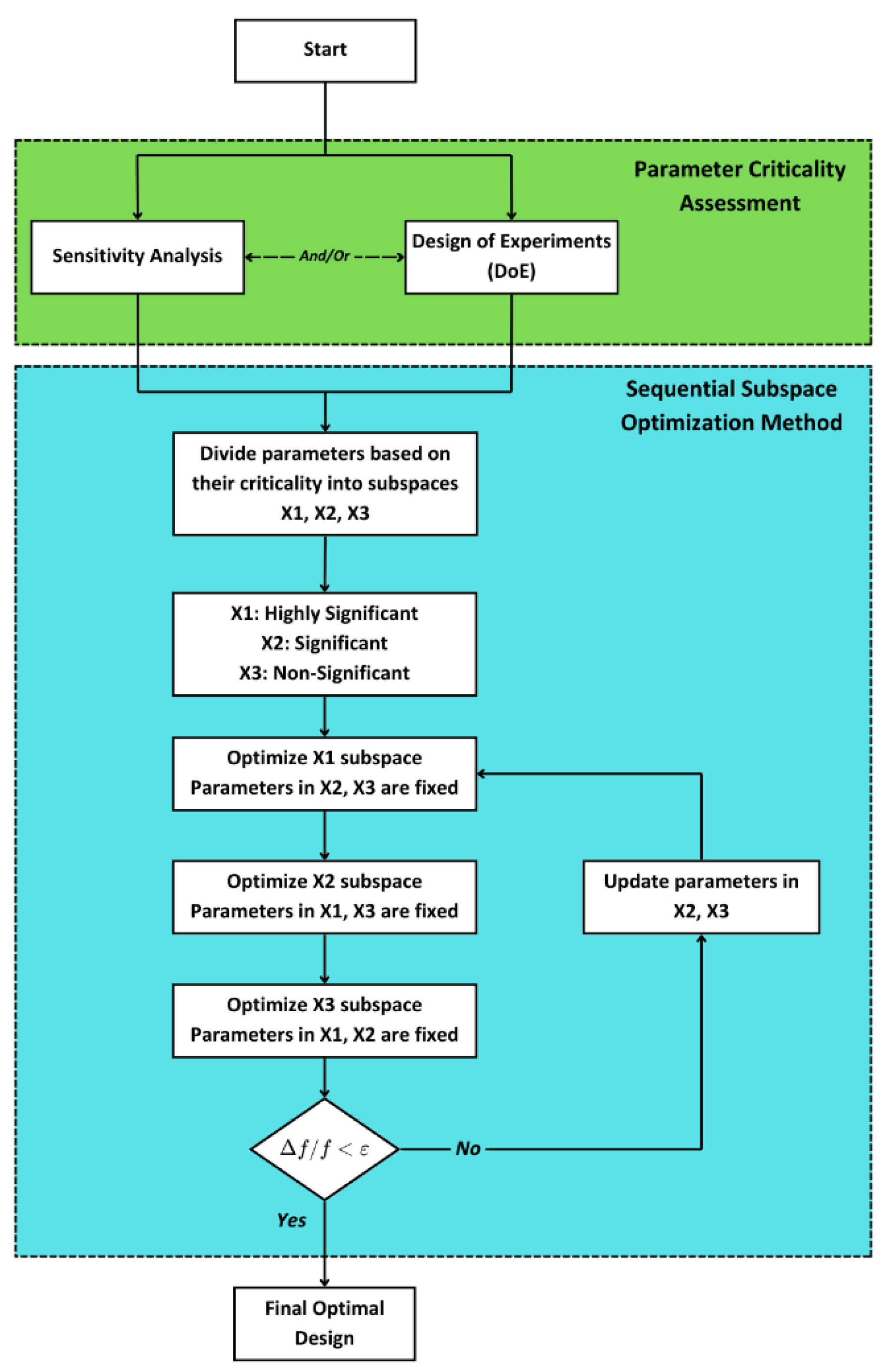

3.2. Parameter Criticality Assessment

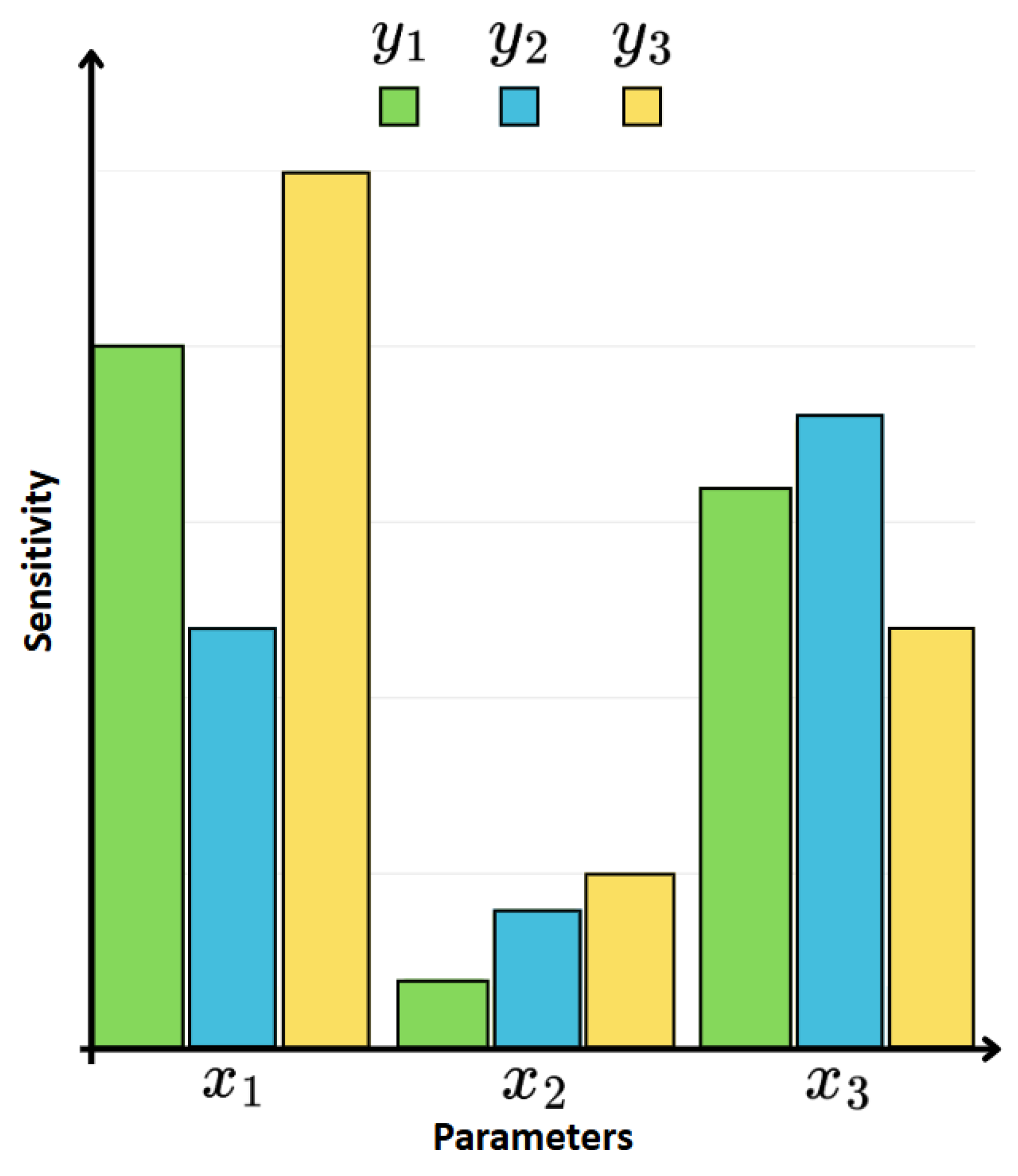

3.2.1. Sensitivity Analysis

3.2.2. Design of Experiments

3.3. Sequential Subspace Optimization Method

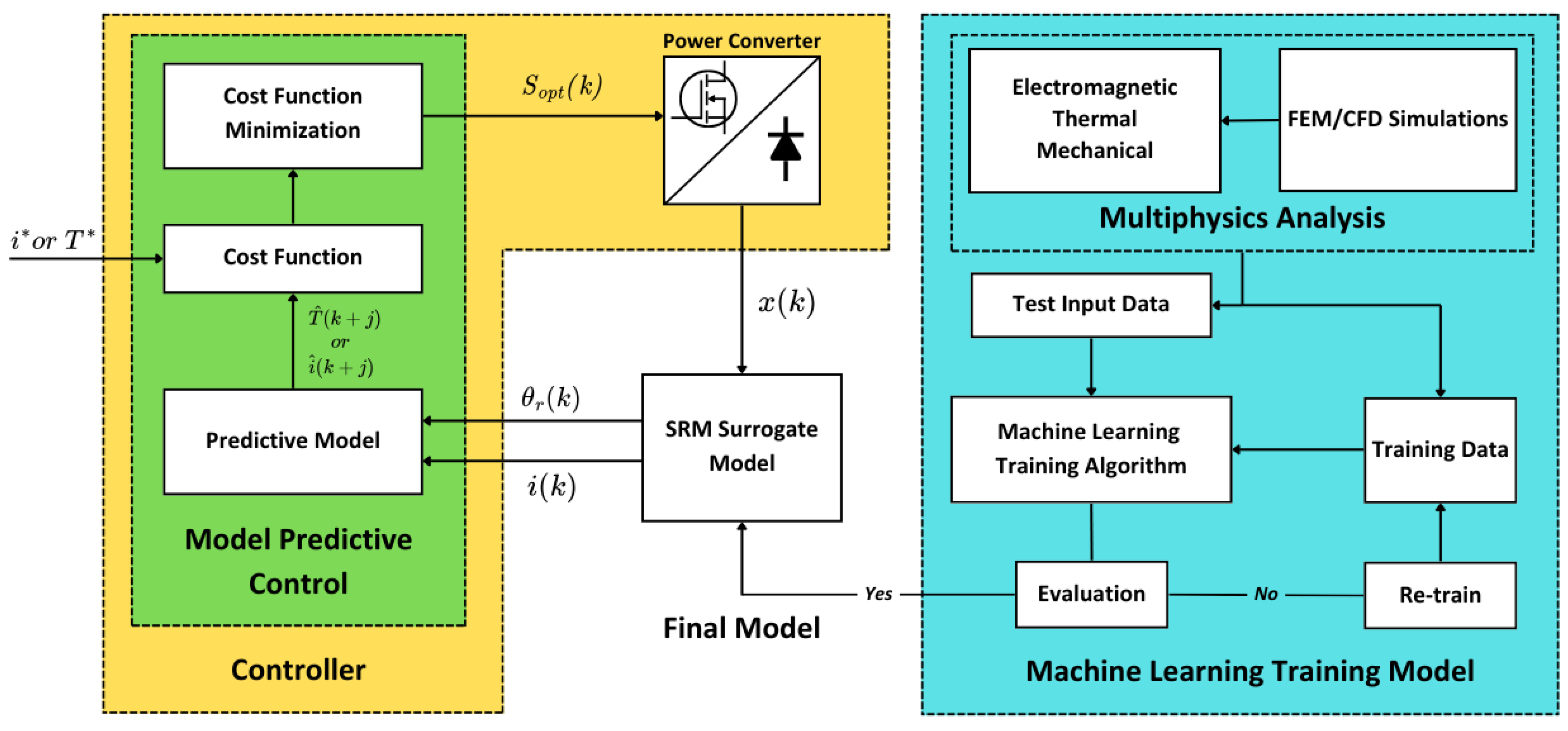

4. Proposed Solution – Machine Learning Modeling Coupled with Model Predictive Control

5. Future Directions in Research

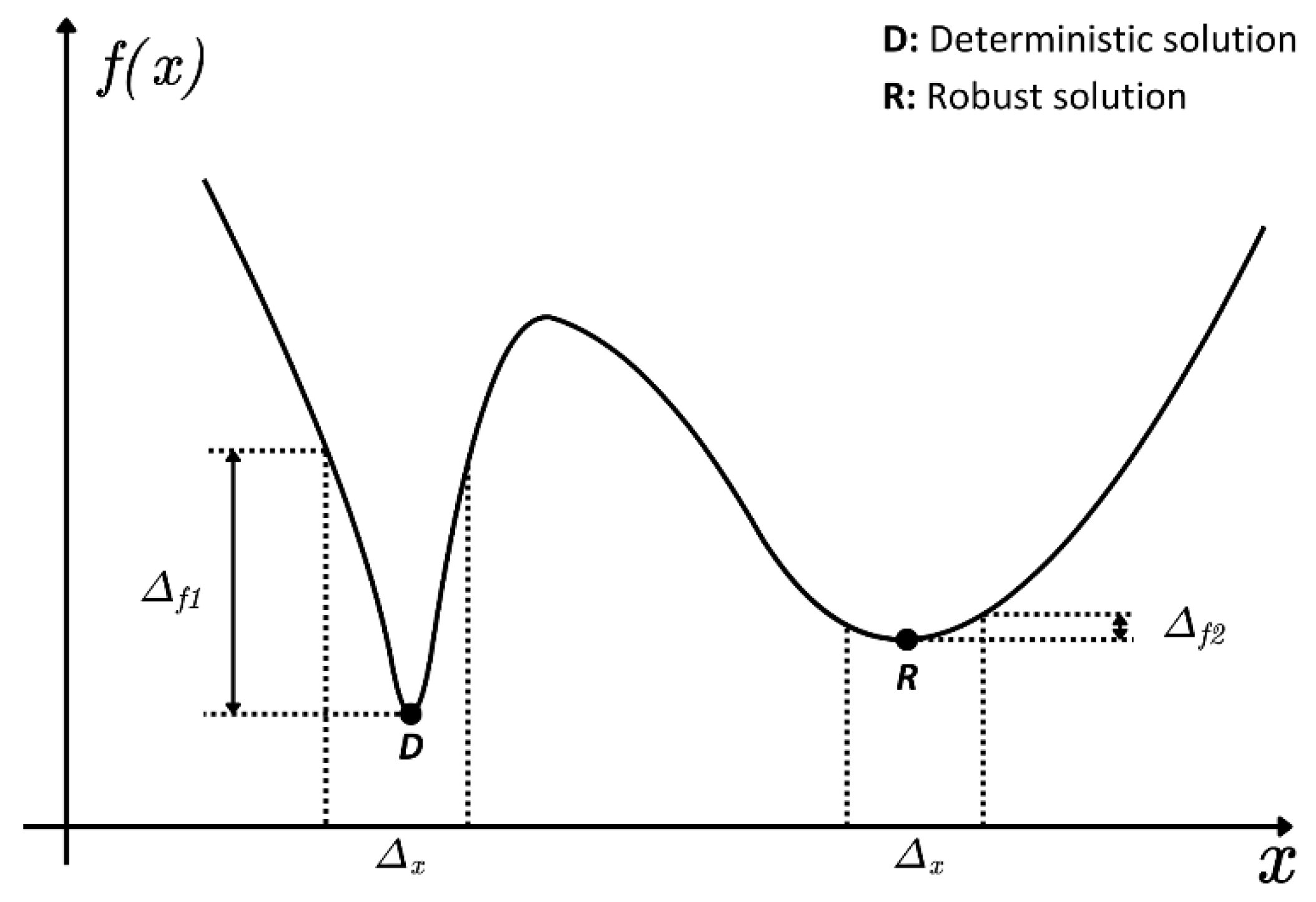

5.1. Integration of Robustness in System-Level Design Optimization

5.2. Noise and Vibration Improvement Through System-Level Design Optimization

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- N. Zabihi and R. Gouws, A Review on Switched Reluctance Machines for Electric Vehicles. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdalmagid, E. Sayed, M. H. Bakr, and A. Emadi, “Geometry and Topology Optimization of Switched Reluctance Machines: A Review,” 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [CrossRef]

- R. Krishnan, Switched reluctance motor drives: modeling, simulation, analysis, design, and applications. CRC press, 2017.

- K. Vijay Babu, N. B.L., and D. M. and Vinod Kumar, “Switched Reluctance Machine for Off-Grid Rural Applications: A Review,” IETE Technical Review, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 428–440, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Bilgin, J. W. Jiang, and A. Emadi, “Switched reluctance motor drives: fundamentals to applications,” Boca Raton, FL, 2018.

- Z. Xu, T. Li, F. Zhang, Y. Zhang, D. H. Lee, and J. W. Ahn, “A Review on Segmented Switched Reluctance Motors,” Dec. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, S. Zhang, T. G. Habetler, and R. G. Harley, “Modeling, design optimization, and applications of switched reluctance machines - A review,” IEEE Trans Ind Appl, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 2660–2681, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Mishra and B. Singh, “Solar-powered switched reluctance motor-driven water pumping system with battery support,” IET Power Electronics, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1018–1031, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Lukman, W. H. Myeong, and J.-W. Ahn, “Design and Analysis of a Low-Cost High-Speed Switched Reluctance Motor for Supercharger,” in 2018 IEEE Student Conference on Electric Machines and Systems, 2018, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- K. Vijayakumar, R. Karthikeyan, S. Paramasivam, R. Arumugam, and K. N. Srinivas, “Switched reluctance motor modeling, design, simulation, and analysis: A comprehensive review,” IEEE Trans Magn, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 4605–4617, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- 2016 IEEE 25th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE) : proceedings : Santa Clara Convention Center, Santa Clara, CA, United States, 08-10 June, 2016. IEEE, 2016.

- K. Diao, X. Sun, G. Bramerdorfer, Y. Cai, G. Lei, and L. Chen, “Design optimization of switched reluctance machines for performance and reliability enhancements: A review,” Oct. 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Jiang, B. Bilgin, B. Howey, and A. Emadi, “Design optimization of switched reluctance machine using genetic algorithm,” in 2015 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), 2015, pp. 1671–1677. [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, W. Du, W. Song, C. Liang, and Y. Tang, “An improved weighted optimization approach for large-scale global optimization,” Complex & Intelligent Systems, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1259–1280, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Tekgun, B. Tekgun, and I. Alan, “FEA based fast topology optimization method for switched reluctance machines,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 1985–1995, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Owatchaiphong and N. H. Fuengwarodsakul, “Multi-objective based optimization for switched reluctance machines using fuzzy and genetic algorithms,” in 2009 International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems (PEDS), 2009, pp. 1530–1533. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao, R. Na, C. Jia, X. Wang, and Y. Zhou, “Multi- objective optimization of switched reluctance motor drive in electric vehicles,” Computers & Electrical Engineering, vol. 70, pp. 914–930, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Gaafar, A. Abdelmaksoud, M. Orabi, H. Chen, and M. Dardeer, “Switched Reluctance Motor Converters for Electric Vehicles Applications: Comparative Review,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 3526–3544, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Lei, J. Zhu, and Y. Guo, “Power Systems Multidisciplinary Design Optimization Methods for Electrical Machines and Drive Systems.” [Online]. Available: http://www.springer.com/series/4622.

- G. Lei, T. Wang, Y. Guo, J. Zhu, and S. Wang, “System-level design optimization methods for electrical drive systems: Deterministic approach,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 6591–6602, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhu, D. Fan, Z. Xiang, L. Quan, W. Hua, and M. Cheng, “Systematic multi-level optimization design and dynamic control of less-rare-earth hybrid permanent magnet motor for all-climatic electric vehicles,” Appl Energy, vol. 253, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Lei, J. Zhu, Y. Guo, C. Liu, and B. Ma, “A review of design optimization methods for electrical machines,” Dec. 01, 2017, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- T. Orosz et al., “Robust design optimization and emerging technologies for electrical machines: Challenges and open problems,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 19, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Li, and Y. Wang, “Fuzzy Inference NSGA-III Algorithm-Based Multi-Objective Optimization for Switched Reluctance Generator,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 3578–3581, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Shah, M. Khalid, and B. Bilgin, “Design of a Switched Reluctance Motor for an Elevator Application,” in 2024 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, ITEC 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Burress and L. M. Tolbert, “A framework for multiple objective Co-optimization of switched reluctance machine design and control,” in 2021 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, ITEC 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jun. 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- H. Ge, H. Hua, X. Duan, and R. Li, “Design and Optimization of High-Speed Switched Reluctance Machines for Aerospace Applications,” in 2024 International Conference on Electrical Machines, ICEM 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Anvari, H. A. Toliyat, and B. Fahimi, “Simultaneous Optimization of Geometry and Firing Angles for In-Wheel Switched Reluctance Motor Drive,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 322–329, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Ma, J. Zhu, and G. Lei, “Advanced Design and Optimization Techniques for Electrical Machines,” Australia, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/advanced-design-optimization-techniques/docview/2877959791/se-2?accountid=197513.

- B. Sandesh Bhaktha, N. Jose, M. Vamshik, J. Pitchaimani, and K. V. Gangadharan, “Driving Cycle-based Design Optimization and Experimental Verification of a Switched Reluctance Motor for an E-Rickshaw,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, S. Wang, H. Qiu, and Y. Song, “Design and System-Level Optimization of Switched Reluctance Motors for Electric Vehicles Oriented to Complex Scenarios,” in Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2021, pp. 841–858. [CrossRef]

- M. Cheng, X. Zhao, M. Dhimish, W. Qiu, and S. Niu, “A Review of Data-driven Surrogate Models for Design Optimization of Electric Motors,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Gu, W. Hua, W. Yu, Z. Zhang, and H. Zhang, “Surrogate Model-Based Multiobjective Optimization of High-Speed PM Synchronous Machine: Construction and Comparison,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 678–688, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, Z. Wang, S. Huang, and H. Lou, “Multi-objective Optimization of Topology and Control Parameters of the Switched Reluctance Motor with 12/8 Poles,” in 2021 IEEE 4th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, M. Cheng, H. Wen, and Y. Jiang, “Design and Many-Objective Optimization of an In-Wheel Hybrid-Excitation Flux-Switching Machine Based on the Kriging Model,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Qiao, S. Han, K. Diao, and X. Sun, “Optimization Design and Control of Six-Phase Switched Reluctance Motor with Decoupling Winding Connections,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 17, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, N. Xu, S. Ge, D. Guo, and B. Wan, “Multilevel and Multiobjective Optimization of a Six-Phase SRM with Bezier Curve,” Journal of Electrical Engineering and Technology, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Diao, X. Sun, G. Lei, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Application-Oriented System Level Optimization Method for Switched Reluctance Motor Drive Systems,” in 2020 IEEE 9th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, IPEMC 2020 ECCE Asia, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Nov. 2020, pp. 472–477. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, X. Sun, N. Xu, B. Wan, and M. Yao, “Design Optimization of a 12/10 Switched Reluctance Motor Considering Target Driving Cycle and Driving Condition,” IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, B. Wan, G. Lei, X. Tian, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Multiobjective and Multiphysics Design Optimization of a Switched Reluctance Motor for Electric Vehicle Applications,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 3294–3304, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohamodhosen, C. Riley, and D. Ilea, “Reduced order modelling method for electromagnetic analysis of electrical machines,” IET Science, Measurement and Technology, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Lei, G. Bramerdorfer, C. Liu, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Robust Design Optimization of Electrical Machines: A Comparative Study and Space Reduction Strategy,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 300–313, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Tekgun, B. Tekgun, and I. Alan, “FEA based fast topology optimization method for switched reluctance machines,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 1985–1995, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Moghaddam, A. Vahedi, and S. H. Ebrahimi, “Design Optimization of Transversely Laminated Synchronous Reluctance Machine for Flywheel Energy Storage System Using Response Surface Methodology,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 64, no. 12, pp. 9748–9757, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Jian, Y. Shi, J. Wei, Y. Zheng, and Z. Deng, “Design optimization and analysis of a dual-permanent-magnet-excited machine using response surface methodology,” Energies (Basel), vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 10127–10140, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Omar, E. Sayed, M. Abdalmagid, B. Bilgin, M. H. Bakr, and A. Emadi, “Review of Machine Learning Applications to the Modeling and Design Optimization of Switched Reluctance Motors,” 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [CrossRef]

- M. Tahkola, J. Keranen, D. Sedov, M. F. Far, and J. Kortelainen, “Surrogate Modeling of Electrical Machine Torque Using Artificial Neural Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 220027–220045, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Omar, M. Bakr, and A. Emadi, “Switched Reluctance Motor Design Optimization: A Framework for Effective Machine Learning Algorithm Selection and Evaluation,” in 2024 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, ITEC 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Demidova, A. Bogdanov, A. Iaremenko, Z. Xirong, H. Chen, and A. Anuchin, “Neural Network Approaches for Magnetization Surface Prediction in Switched Reluctance Motors: Classical, Radial Basis Function, and Physics-Informed Models,” in Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd International Conference on Problems of Informatics, Electronics and Radio Engineering, PIERE 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 1270–1275. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Abdollahi, N. Vaks, and B. Bilgin, “A Multi-objective Optimization Framework for the Design of a High Power-Density Switched Reluctance Motor,” in 2022 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, ITEC 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 67–73. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, S. Zhang, C. Jiang, J. R. Mayor, T. G. Habetler, and R. G. Harley, “A fast control-integrated and multiphysics-based multi-objective design optimization of switched reluctance machines,” in 2017 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), 2017, pp. 730–737. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, S. Rao, and X. Zhang, “Performance prediction of switched reluctance motor using improved generalized regression neural networks for design optimization,” CES Transactions on Electrical Machines and Systems, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 371–376, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, W. Hua, Y. Gao, Y. Wang, and H. Zhang, “An improved Kriging surrogate model method with high robustness for electrical machine optimization,” in 2022 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific, ITEC Asia-Pacific 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Qiao, K. Diao, S. Han, and X. Sun, “Design optimization of switched reluctance motors based on a novel magnetic parameter methodology,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 104, no. 6, pp. 4125–4136, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Burress and L. M. Tolbert, “Multiple Objective Co-Optimization and Experimental Evaluation of Switched Reluctance Machine Design and Control,” in 2023 IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, IEMDC 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, H. Yuan, Y. Wu, Y. Geng, and W. Cao, “A Preference Multi-Objective Optimization Method for Asymmetric External Rotor Switched Reluctance Motor,” 2022.

- C. Huang, H. Yuan, W. Cao, and Y. Wu, “Multi-Objective Optimization Design of ERSRM with Asymmetric Stator Poles,” 2023.

- Y. Gong, S. Zhao, and S. Luo, “Design and optimization of switched reluctance motor by Taguchi method,” in 2018 13th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), 2018, pp. 1876–1880. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, Z. Shi, and J. Zhu, “Multiobjective Design Optimization of an IPMSM for EVs Based on Fuzzy Method and Sequential Taguchi Method,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 68, no. 11, pp. 10592–10600, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Gope and S. K. Goel, “Design optimization of permanent magnet synchronous motor using Taguchi method and experimental validation,” International Journal of Emerging Electric Power Systems, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 9–20, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Yan, J. Hu, H. Chen, H. Li, F. Yu, and Q. Wang, “Design of Novel Hybrid Excitation Segmented-Rotor Switched Reluctance Motor for Electric Vehicle,” in Proceedings of 22nd International Symposium on Power Electronics, Ee 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Diao, X. Sun, G. Lei, G. Bramerdorfer, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “System-Level Robust Design Optimization of a Switched Reluctance Motor Drive System Considering Multiple Driving Cycles,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 348–357, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Abunike, O. I. Okoro, A. J. Far, and S. S. Aphale, “Advancements in Flux Switching Machine Optimization: Applications and Future Prospects,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 110910–110942, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, Z. Shi, G. Lei, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Multi-Objective Design Optimization of an IPMSM Based on Multilevel Strategy,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 139–148, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Lei, T. Wang, J. Zhu, Y. Guo, and S. Wang, “System-Level Design Optimization Method for Electrical Drive Systems - Robust Approach,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 4702–4713, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Diao, X. Sun, G. Lei, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Multiobjective system level optimization method for switched reluctance motor drive systems using finite-element model,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 10055–10064, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Omar, M. H. Bakr, and A. Emadi, “Advanced Design Optimization of Switched Reluctance Motors for Torque Improvement Using Supervised Learning Algorithm,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 122057–122068, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Kocan, P. Rafajdus, R. Bastovansky, R. Lenhard, and M. Stano, “Design and optimization of a high-speed switched reluctance motor,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 20, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Jiang and T. M. Jahns, “Coupled electromagnetic/thermal machine design optimization based on finite element analysis with application of artificial neural network,” in 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), 2014, pp. 5160–5167. [CrossRef]

- Qiang Yu, Xuesong Wang, and Yuhu Cheng, “Multiphysics optimization design flow with improved submodels for salient switched reluctance machines,” International Journal of Applied Electromagnetics and Mechanics, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 501–514, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, J. Wang, L. Sun, H. Kang, L. Liu, and L. Zhou, “Multi-Objective Optimization of Electromagneticthermal Coupling Performance for High-torquedensity PMSM based on Multi-dimensional Correction Techniques,” in 2024 International Conference on Electrical Machines, ICEM 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, S. Zhang, T. G. Habetler, and R. G. Harley, “A survey of electromagnetic — Thermal modeling and design optimization of switched reluctance machines,” in 2017 IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference (IEMDC), 2017, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- L. Feng et al., “A review on control techniques of switched reluctance motors for performance improvement,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 199, p. 114454, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Ma, F. Ling, F. Li, and F. Liu, “Torque ripple suppression of switched reluctance motor by segmented harmonic currents injection based on adaptive fuzzy logic control,” IET Electr Power Appl, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 325–335, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Cai, X. Dou, A. D. Cheok, W. Ding, Y. Yan, and X. Zhang, “Model Predictive Control Strategies in Switched Reluctance Motor Drives-An Overview,” IEEE Trans Power Electron, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Valencia, R. Tarvirdilu-Asl, C. Garcia, J. Rodriguez, and A. Emadi, “Vision, Challenges, and Future Trends of Model Predictive Control in Switched Reluctance Motor Drives,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 69926–69937, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Valencia, R. Tarvirdilu-Asl, C. Garcia, J. Rodriguez, and A. Emadi, “A Review of Predictive Control Techniques for Switched Reluctance Machine Drives. Part I: Fundamentals and Current Control,” IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ENERGY CONVERSION, vol. 36, no. 2, p. 1313, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gmyrek, “The Impact of the Core Laminate Shaping Process on the Parameters and Characteristics of the Synchronous Reluctance Motor with Flux Barriers in the Rotor,” Energies (Basel), vol. 18, no. 5, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Falekas, Z. Kolidakis, and A. Karlis, “Investigation of Discrepancies Between Induction Motor Test Results and Design Simulation,” in 2024 International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), 2024, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- K. Diao, X. Sun, G. Lei, G. Bramerdorfer, Y. Guo, and J. Zhu, “Robust Design Optimization of Switched Reluctance Motor Drive Systems Based on System-Level Sequential Taguchi Method,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 3199–3207, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Diao, X. Sun, and M. Yao, “Robust-Oriented Optimization of Switched Reluctance Motors Considering Manufacturing Fluctuation,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 2853–2861, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Sahu, A. Emadi, and B. Bilgin, “Noise and Vibration in Switched Reluctance Motors: A Review on Structural Materials, Vibration Dampers, Acoustic Impedance, and Noise Masking Methods,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 27702–27718, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Das, O. Gundogmus, Y. Sozer, J. Kutz, J. Tylenda, and R. L. Wright, “Wide Speed Range Noise and Vibration Mitigation in Switched Reluctance Machines With Stator Pole Bridges,” IEEE Trans Power Electron, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 9300–9311, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, S. Yaman, M. Salameh, S. Singh, C. Chen, and M. Krishnamurthy, “Effectiveness of power electronic controllers in mitigating acoustic noise and vibration in high-rotor pole srms,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 3, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

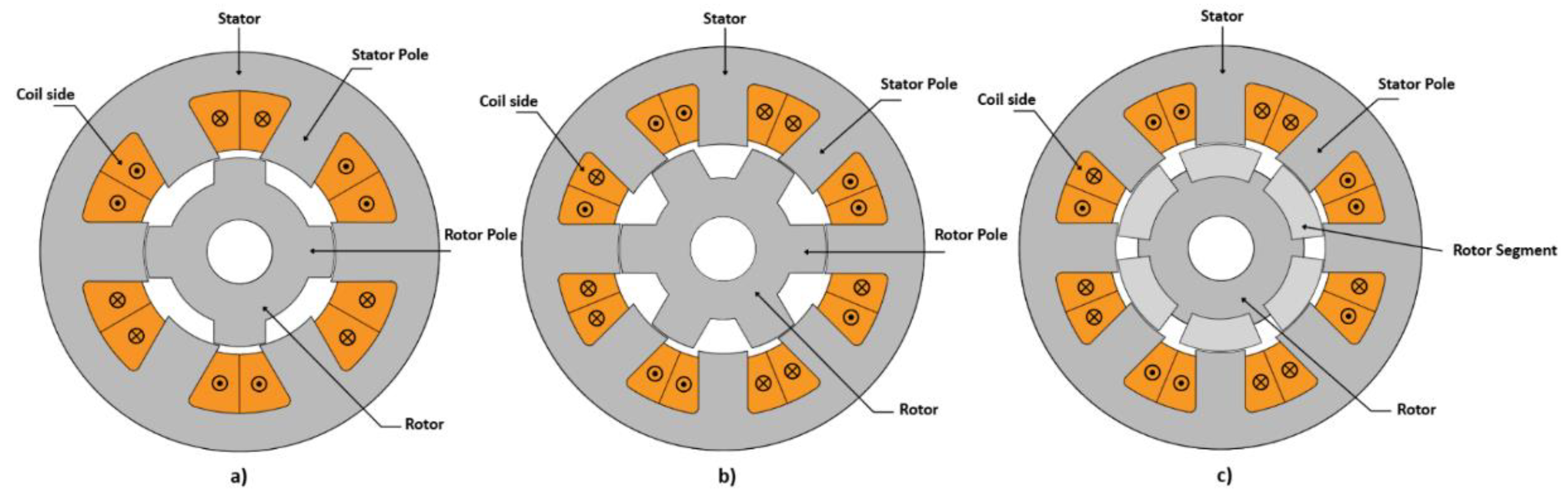

| Kriging model | RSM | ANN | Models employing SA | Models employing DoE | Models employing SSOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational time/number of simulations compared to FEM | [30] from 30 min to a few seconds | [43] 559 simulations from 3,000 ones, from 33 hours to roughly 6 | [50] from 900 candidate models to a fraction of them | [54] 33% fewer parameters in simulations | [61] from 15,625 to 25 simulations | [66] from 50,000 to 3,993 simulations (92% reduction) |

| [36] from 100 thousand to 1,125 simulations | [55] from 1-3 mins to 0.5-3 secs | |||||

| [37] from 1,331 to 726 simulations | [62] from 81 to 18 simulations (78% reduction) | |||||

| [38] from 27 million to 1,331 simulations | [56] 90% down in computation time | |||||

| [40] from a few million to a few thousands | ||||||

| Model accuracy compared to FEM | [30] 1-2% discrepancies | [43] almost 100% accuracy | [50] average error 1.5%, maximum error 3% | [54] max 23% overprediction | [61] maximum error 1% | [66] errors well within 1% in the convergence measure |

| [36] decent accuracy | [55] maximum error 2% | |||||

| [37] 1.79% maximum error | [56] maximum error 5% | [62] maximum error 5% | ||||

| [38] average error 1%, maximum error 3.1% |

| Ref. | Modeling | Optimization Algorithm | System-Level Algorithm |

Optimization Parameters Machine/Control |

Optimization Goals | Application | ||

| [24] | RSM | FIS - NSGA-III | Single-Level | Geometrical Parameters / θon, θc | Efficiency, Torque Ripple, Power Density | SRG Drives | ||

| [25] | FEM | GA | Candidate Models / θon, θoff | Average Torque, Torque Ripple | Vertical Transportation | |||

| [26] | FEM | PSO | Geometrical Parameters / θon, θoff |

Efficiency, Torque Ripple, Power Density | SRM Drives | |||

| Ref. | Modeling | Optimization Algorithm | System-Level Algorithm | Optimization Parameters Machine/Control |

Optimization Goals | Application | ||

| [27] | Field-Circuit coupled FEM | GA | Single-Level | Geometrical Parameters / θon, θoff |

Efficiency, Mass | Aerospace Applications | ||

| [28,31] | [28] FEM, [31] FEM with SA | [28] NSGA-II, [31] GA | [28] Single-Level, [31] Multi-Level | Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Efficiency | [28] In-Wheel application EV, [31] EV | |||

| [30] | Kriging | NSGA-II | Multi-Level | Average Torque, Torque Density, Losses | EV | |||

| [34] | PR Model | MOGA | Rotor pole shape / θon, θoff |

Average Torque, Torque Ripple | SRM Drives | |||

| [36] | Kriging | NSGA-II | Single-Level | Yoke width ratio / θon, θc |

Average Torque, Torque Ripple, RMS Current | |||

| [37,38,66] | Kriging with SA | [37,38] NSGA-II, [66] SSOM - NSGA-II |

[37] Rotor pole shape, [38,66] Geometrical Parameters / θon, θoff |

Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Losses | ||||

| [39] | Kriging with SA | GRA with TOPSIS | Multi-Level | Geometrical Parameters / θon, θoff |

Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Losses | EV | ||

| [40] | FEM with TLPTM - Kriging with SA | NSGA-II | Single-Level | Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Losses, Temperature Rise | ||||

| [43] | RSM with SA | DE | Torque Ripple, Mass, Copper Losses | In-Wheel application EV | ||||

| [50] | RBFNN with SA | GA, PSO, GRSM | Multi-Level | Candidate Models / θon, θoff | Radial Force Harmonics, Torque Ripple, Average Torque | SRM Drives | ||

| [54] | Analytical Equations with SA | DE | Single-Level | Geometrical Parameters / θon, θoff |

Average Torque, Current Density, Torque Ripple | |||

| [55] | Voltage-fed Analytical Equations and FEM | PSO | Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Efficiency | |||||

| [56], [57] |

FEM with SA | [56] CD-NSGA-II [57] NSGA-II |

[56] Efficiency, Average Torque, [56,57] Torque Ripple |

E-Bikes | ||||

| [61,62] | Taguchi with SA | Taguchi | Average Torque, Torque Ripple, Torque Density | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).