Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

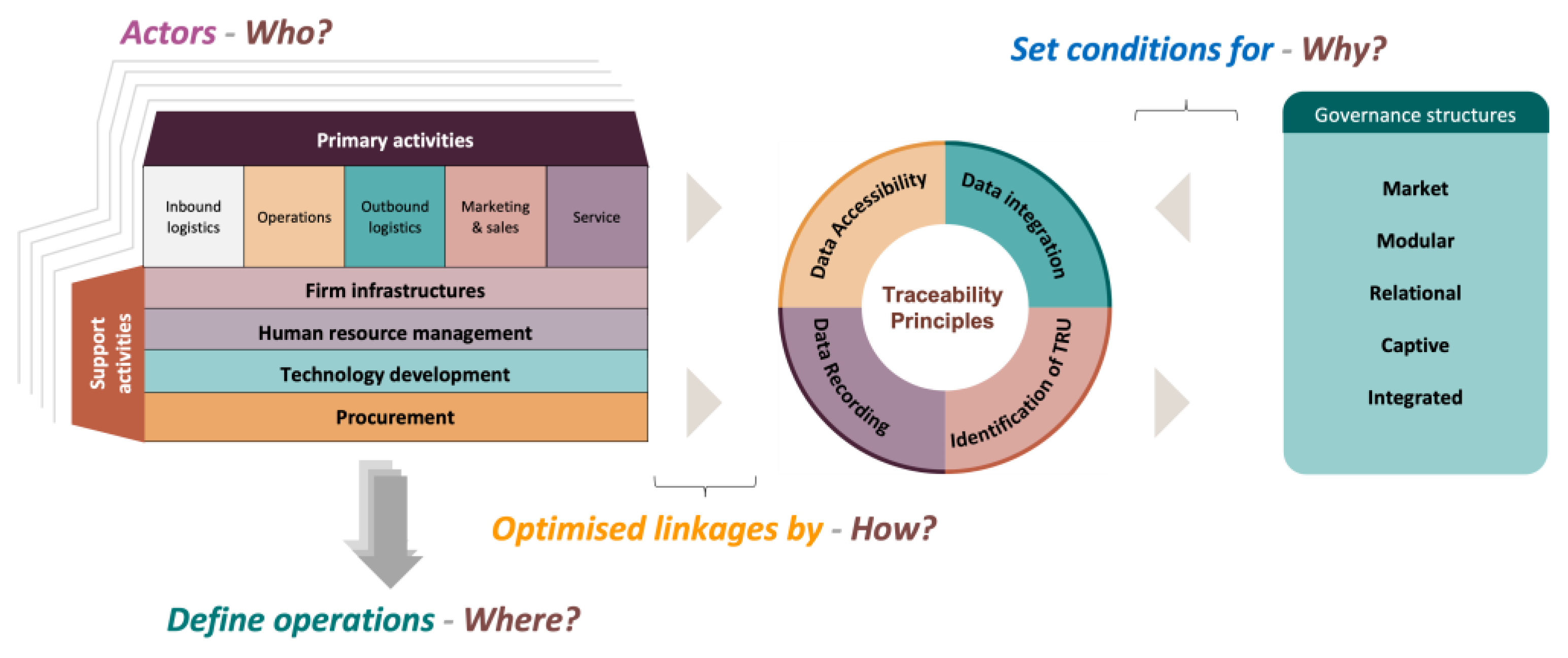

2.1. Analytical Framework

2.1.1. Why Trace? Governance Structures and Transaction Complexity

2.1.2. Where to Trace? Internal vs. External Operations and Specialization

2.1.3. Who Traces? Actors, Responsibilities, and Governance of Information

2.1.4. How to Trace? Mechanisms of Data Capture, Integration, and Use

2.1.5. Identification

2.1.6. Data Recording

2.1.7. Integration Data

2.1.8. Data Accessibility

2.2. Data Collection

| ID | Traceability object | Traceability driver | Who Benefits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | Wine production process from grapes to bottles | Regulatory compliance, quality assurance, brand trust | Producers, regulatory bodies, consumers | ||

| ICT1 | Milk collection to cheese production and aging | Quality assurance, regulatory compliance, consumer transparency | Farmers, cheese producers, consumers | ||

| ICT4 | Cheese production from raw milk to final product | Quality assurance, compliance, consumer transparency | Producers, processors, consumers, brand owners | ||

| P3 | Olive oil production from harvest to bottling | Quality certification (DOP, organic), consumer transparency | Producers, consumers, certification bodies | ||

| T3 | Wheat cultivation to pasta production and packaging | Quality assurance, consumer transparency, origin verification | Farmers, millers, pasta producers, consumers |

3. Results

3.1. Actors, Who?

3.1.1. Primary Producers (P,C)

3.1.2. Agri-Food Industry (T)

3.1.3. ICT Companies (ICT)

3.2. Define Operations, Where?

3.2.1. Wine Supply Chain

3.2.2. Olive Oil Supply Chain

3.2.3. Pasta and Cheese Supply Chain

3.3. Optimised Linkages – How?

3.4. Set Conditions for Why?

3.5. Successful Value Networks

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVO | Extra-virgin olive oil |

| PDO | Protected Designation of Origin |

| PGI | Protected Geographical Indication |

| TRU | Traceable Resource Unit |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Operation and Type of data traced | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin and Cultivation Data | Farm records: Details about specific plots, number of trees, geographic layout, and treatments applied | Agricultural operations: Pruning, fertilization, pest control and other agronomic practices | |

| Harvesting and Transportation | Harvest details: Date, type and quantity of olives harvested | Transport documents: Origin of olives, supplier, fields, and delivery notes to the mill | Transportation data: Vehicle details, capacity, transport conditions |

| Processing and Milling |

Processing stages: Quantity of olives received, washing, milling and crushing, malaxation, extraction, storage, and filtration |

Milling log: Date of milling, type of extraction, yield, and quality of the product (Chemical-physical tests) | Oil storage: Tank number, movements, labelling (barcodes) and weight records |

| Quality Control and Certification |

Quality control: Accompanying documents, PDO/PGI certification, acidity, phenol content, peroxide levels, organoleptic analysis parameters. |

Certification details: Compliance certificates, hygienic conditions of storage tanks | Analytical reports and panel test evaluations |

| Bottling and Labelling | Bottling process: Entry of oil from the mill, yield from each milling batch, caps and bottles used | Labelling: Bottle tracking number, label generation, batch number, QR codes for traceability | Packaging data: Quantity of bottles produced, bottle format, minimum shelf life |

| Distribution and Sales | Sales data: Details of product transfer to customers, online and offline sales tracking | Transport and logistics: Tracking shipment routes, transit times, temperature and humidity monitoring | Warehouse management: Product flow, customer orders, storage, and dispatch |

| Operation and Type of data traced | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin and Cultivation Data | Field operations: Agricultural activities, water resources, pesticides, crop protection, and other environmental data | ||

| Harvesting and Transportation | Grape harvest: Harvesting period, geolocation of vineyards | Grape batches: Grape type, year, quantity, alcohol content | Transportation data: Vehicle details, capacity, transport conditions |

| Processing | Crushing or destemming: Date, operation number, client, grapes being unloaded, products obtained. | Racking: Date, operation number, product being unloaded, new wine, products obtained. | Vinification and aging process: Tank identification (barcode), quality checks during processing. |

| Quality Control and Certification | Quality control: Analytical tests, quality control parameters | Certification: Compliance with PDO/PGI and Organic regulations, chemical analysis, and certification | |

| Bottling and Labelling | Bottling process: Test and quality check during bottling step, batch number, production records | Labelling: Barcode tracking, label generation, lot number | Packaging data: Bottles, caps, cartons, labels used |

| Distribution and Sales | Sales data: Product transfer, customer tracking (QR code) | Logistics: Shipment tracking, temperature and humidity monitoring, transit times | |

| Operation and Type of data traced | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin and Cultivation Data | Crop protection: pesticides, water resources | IoT sensors in the field: plant health, soil moisture | |

| Breeding and Milk production | Diets of cows and sheep: lactation, dry periods | Milk production: quantity and quality of milk | IoT sensors in the barn: tempera ture and humidity |

| Processing | Milk collection and pasteurization | Transformation into fresh cheeses and pecorino | Identification of cheese forms: taleggio, ricotta, pecorino |

| Packaging and Labelling | Batch traceability: milk batch, tank number, production date | Certification details: Compliance certificates, hygienic conditions of storage tanks | |

| Transport and Distribution | Transportation data: Vehicle details, capacity, transport conditions | Distribution traceability: wholesalers, retailers, final customers | |

| Operation and Type of data traced | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin and Cultivation Data | Agricultural operations: Pesticides, fertilization, pest control, water resources | ||

| Harvesting and Transportation | Harvesting: date, variety, field location | Transport documents: Origin, supplier, fields, and delivery notes to the mill | Transportation data: Vehicle details, capacity, transport conditions |

| Processing and Milling (Semolina production) | Processing date, Semolina batch number, Orders details from the pasta factory | ||

| Pasta production | Processing conditions | Pasta batch number | |

| Packaging and Labelling | Batch traceability: tank number, production date | Packaging: quantity of cartons, labels | |

| Distribution | Distribution traceability: wholesalers, retailers, final customers | Packaging: quantity of cartons, labels | |

References

- Daniele Vergamini, Maria Bonaria Lai, Gianluca Brunori. Trace to Treasure: What’s the role of traceability systems in adding value across diverse agrifood value networks?. In Proceedings of LX Convegno SIDEA 2024 ‘Dalla Strategia Farm-To-Fork All’Approccio One-Health: Soluzioni Per Il Modello Agricolo Europeo Alla Luce Dei Nuovi Scenari Economici’, Anacapri, Italy, 16 Settembre 2024.

- Garske, B; Bau, A; & Ekardt, F. Digitalization and AI in European agriculture: A strategy for achieving climate and biodiversity targets?. Sustainability 2021, Volume 13(9), 4652. [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G. Agriculture and rural areas facing the “twin transition”: principles for a sustainable rural digitalisation. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics 2022, Volume 77(3), pp. 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Finger, R. Digital innovations for sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2023, 50(4); pp. 1277-1309. [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. Blockchain’s roles in meeting key supply chain management objectives. International Journal of information management,2018, 39, 80-89. [CrossRef]

- Galvez JF, Mejuto JC, Simal-Gandara J. Future challenges on the use of blockchain for food traceability analysis. TrAC Trends Anal Chem 2018;107:222–32. [CrossRef]

- Giganti, P., Borrello, M., Falcone, P. M., & Cembalo, L. The impact of blockchain technology on enhancing sustainability in the agri-food sector: A scoping review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 142379. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Bacco, M.; Gaber, K.; Jedlitschka, A.; Hess, S.; Kaipainen, J.; Koltsida, P.; Toli, E.; Brunori, G. Drivers, barriers and impacts of digitalization in rural areas from the viewpoint of experts. Information and Software Technology, 2022, 145, 106816. [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Maye, D.; Bailye, C.; Barnes, A.; Bear, C.; Bell, M.; Cutress, D.; Davies, L.; de Boon, A.; Dinnie, L.; Gairdner, J.; Hafferty, C.; Holloway, L.; Kindred, D.; Kirby, D.; Leake, B.; Manning, L.; Marchant, B.; Morse, A.; Oxley, S.; Phillips, M.; Regan, Á.; Rial-Lovera, K.; Rose, D.C.; Schillings, J.; Williams, F.; Williams, H.; Wilson, L. What are the priority research questions for digital agriculture? Land Use Policy, 2022, 114, 105962.

- Rolandi, S., Brunori, G., Bacco, M., & Scotti, I. The digitalization of agriculture and rural areas: Towards a taxonomy of the impacts. Sustainability, 2021, 13(9), 5172. [CrossRef]

- Tsouros, D. C., Bibi, S., & Sarigiannidis, P. G. (2019). A review on UAV-based applications for precision agriculture. Information, 10(11), 349. [CrossRef]

- Ray, P. P. Internet of things for smart agriculture: Technologies, practices and future direction. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart Environments, 2017, 9(4), 395–420. [CrossRef]

- Maffezzoli, F., Ardolino, M., Bacchetti, A., Perona, M., & Renga, F. Agriculture 4.0: A systematic literature review on the paradigm, technologies and benefits. Futures, 2022,142, 102998. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Abdelsalam, M., Khorsandroo, S., & Mittal, S. (2020). Security and privacy in smart farming: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access, 8, 34564–34584. [CrossRef]

- Muzammal, M., Qu, Q., Nasrulin, B., 2019. Renovating blockchain with distributed databases: an open source system. Future Generat. Comput. Syst. 90, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N., Marinakis, Y., Olson, S., White, R., & Walsh, S. Is blockchain mining profitable in the long run?. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2023, 70(2), 386-399. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Cullen, J.M. Food traceability: A generic Theoretical framework. Food Control, 2021; 123, 107848. [CrossRef]

- ISO/TC 176/SC 1 22005:2005, Traceability in the feed and food chain- general principles and basic requirements for system design and implementation (2005).

- FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius. (1997). Joint FAO. Rome: WHO Food Standards Programme Codex Alimentarius Commission, 1997.

- EU. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. Official Journal of the European Communities, 2002, 31, 1–24, 2002.

- Bosona, T., & Gebresenbet, G. (2013). Food traceability as an integral part of logistics management in food and agricultural supply chain. Food control, 33(1), 32-48. [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D., Margariti, S., Stylios, C., Arvaniti, E., & Kafetzopoulos, P. Managing the traceability system for food supply chain performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 2023, 73(2), 563-582. [CrossRef]

- Latino, M. E., Menegoli, M., Lazoi, M., & Corallo, A. Voluntary traceability in food supply chain: a framework leading its implementation in Agriculture 4.0. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2022,178, 121564. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press, New York, NY, 1985.

- Kogut, B. (Designing global strategies: comparative and competitive value added chains. Sloan Management Review, 1985, 26, 15–28.

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeo, T. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 2005, Volume 12, pp. 78-104. [CrossRef]

- Henrsiksen, L.F., Riisgaard, L., Ponte, S., Hartwich, F., Kormawa, P. (2010). Agro-Food Value Chain Interventions in Asia. A review and analysis of case studies. International Fund for Agricultural Development. United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, Austria. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2011-01/WorkingPaper_VC_AsiaFinal_0.pdf.

- WBCSD (2011) Collaboration, innovation, transformation: Ideas and inspiration to accelerate sustainable growth – A value chain approach. https://www.wbcsd.org/Archive/Sustainable- Lifestyles/Resources/Collaboration-Innovation-Transformation-Ideas-and-Inspiration-to- Accelerate-Sustainable-Growth-A-value-chain-approach.

- Peppard, J.; Rylander, A. (2006). From value chain to value network: insights for mobile operators. European Management Journal 2006; Volume 24, pp. 128–141. [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M., Brunori, G., Scotti, I., Ievoli, C., & UNIMOL, A. B. (2021). MOVING Conceptual Framework.

- European Commission. (2018). Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D), Methodological Brief - Frame and Tools. Version 1.2.

- Galli, F., Bartolini, F., Brunori, G., Colombo, L., Gava, O., Grando, S., & Marescotti, A. Sustainability assessment of food supply chains: an application to local and global bread in Italy. Agricultural and Food Economics, 2015, 3, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M., & Peck, H. (2004). Building the resilient supply chain.

- Bolwig, S., Ponte, S., du Toit, A., Riisgaard L., Halberg, N. Integrating poverty and environmental concerns into value-chain analysis: a conceptual framework. Development Policy Review, 2010, 28, 173- 194. [CrossRef]

- Reddy Amarender, A. (2013). Training Manual on Value Chain Analysis of Dryland Agricultural Commodities. Patancheru 502 324, Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi- Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). 88 pp. https://oar.icrisat.org/6888/1/Reddy_a_Train_Manual_2013.pdf.

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1959.

- Imeri, D. Khadraoui, 9th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security. Paris, France, 26-28 February 2018. Paris, FranceThe Security and Traceability of Shared Information in the Process of Transportation of Dangerous Goods2018, The Security and Traceability of Shared Information in the Process of Transportation of Dangerous Goods (2018).

- Saberi, S., Kouhizadeh, M., Sarkis, J., & Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. International journal of production research, 2019, 57(7), 2117-2135. [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 22005; 2007 CEN. (2007). EN ISO 22005:2007, Traceability in the feed and food chain – General principles and basic requirements for system design and implementation. Brussels: European Committee for Standardization (CEN). (VERIFICARE SILVIA).

- Olsen, P., & Borit, M. (2013). How to define traceability. Trends in food science & technology, 29(2), 142-150. [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A., & Manning, L. Using the rapid alert system for food and feed: Potential benefits and problems on data interpretation. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2021, 61(6), 906-919. [CrossRef]

- Vergamini, D., Bartolini, F., Prosperi, P., & Brunori, G. Explaining regional dynamics of marketing strategies: The experience of the Tuscan wine producers. Journal of Rural Studies, 2019, 72, 136-152. [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha Oliveira Teixeira, R., Arcuri, S., Cavicchi, A., Galli, F., Brunori, G., & Vergamini, D. Can alternative wine networks foster sustainable business model innovation and value creation? The case of organic and biodynamic wine in Tuscany. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2023, 7, 1241062. [CrossRef]

| ID | Type | Location | Supply chain | Traceability | Technologies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int | Est | |||||

| A|1 | Organic Food supplier | Emilia Romagna | Olive oil | ü | ü | Blockchain |

| A|2 | Meat supplier | Lombardy | Meat | ü | ü | Management software+e-commerce |

| C1 | Cooperative | Tuscany | Wine | ü | ü | BI software+vinification software |

| C2 | Cooperative | Tuscany | Wine | ü | ü | Management Software + sensors |

| C3 | Cooperative | Apulia | Olive Oil | ü | ü | ERP |

| C4 | Cooperative | Tuscany | Wine | ü | ü | ERP + temperature sensors |

| C5 | Consortium | Veneto | Wine | ü | ü | Management software+APP |

| C6 | Cooperative | Sardinia | Wine | ü | ü | Management software |

| C7 | Consortium | Campania | Olive oil | ü | ü | Blockchain+Management software |

| C8 | Cooperative | Tuscany | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Milling software |

| CC1 | Certification company | Lazio | Various | ü | Dataloger + App + +AR+VR+Blockchain | |

| E1 | Consulting firm | Tuscany | Various | Scanner software+RFID systems | ||

| E2 | Consulting firm | Pidemont | Various | Blockchain+AI+smart collars | ||

| ICT1 | Tech. company | Sardinia | Dairy | ü | ü | APP+blockchain+sc |

| ICT2 | Tech. company | Campania | Trust services | |||

| ICT3 | Tech. company | Aosta Valley | Various | LoRa+low energy sensors+blockchain | ||

| ICT4 | Tech. company | Sardinia | Various | |||

| P1 | Farm | Apulia | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Blockchain |

| P2 | Winery | Tuscany | Wine | ü | ü | 2 in-house software |

| P3 | Farm | Tuscany | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Blockchain+sc |

| P4 | Farm+mill | Campania | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Blockchain+ERP |

| P5 | Farm+mill | Sardinia | Olive Oil | ü | Milling software+ TAG NFC | |

| P6 | Farm | Sardinia | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Excel+Management Software+GPS |

| T1 | Snack Factory | Sardinia | Snacks | ü | ü | - |

| T2 | Dairy factor | Abruzzo | Cheeses | ü | IoT+ blockchain+ERP | |

| T3 | Pasta factory | Campania | Pasta | ü | ü | Blockchain+sc |

| T4 | Pasta factory | Sardinia | Pasta | ü | 2 farming platforms + smart harvester | |

| T5 | Mill company | Tuscany | Olive Oil | ü | ü | Management software |

| ID | Main Spec. | Product traced | Revenue | Net Profit | Employee | ROE | ROA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euros | Number | % | |||||

| A|1 | Marketing | EVO oil | 73,214,825 | 51,791 | 100 | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| A|2 | Marketing | Meat | 1,194,426 | -1,406,267 | 8 | n.s. | -143.14 |

| C1 | Prod./marketing | Wine | 5,019,906 | 23,983 | 21 | 1.56 | 0.78 |

| C2 | Prod./marketing | Wine | 13,822,793 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 1.06 |

| C3 | Prod./marketing | Olive Oil | 7,107,887 | 9,931 | 3 | 4.36 | 1.45 |

| C4 | Prod./marketing | Wine | 2,933,033 | 15,149 | 10 | 1.67 | 1.04 |

| C5 | Protection/prom. | Wine | 510,555 | 34,902 | 10 | 6.34 | 1 |

| C6 | Production | Wine | 11,916,258 | 258 | 34 | 0 | 0.59 |

| C7 | Protection/prom. | EVO Oil | 291 | -10,381 | - | n.s. | -159.42 |

| C8 | Prod./marketing | Olive Oil | 392,255 | 144,880 | 7 | 29.84 | 15.32 |

| CC1 | Quality controls | Various | 36,165,329 | 411,467 | 217 | 19.44 | 4.22 |

| E1 | R&D | Several | 550,898 | 24,075 | 6 | 12.61 | 8.14 |

| E2 | Traceability services | Alpine grazing | - | - | - | - | - |

| P1 | Olive growing | EVO Oil | 72,868 | 3,746 | 0 | 65.19 | 11.32 |

| P2 | Prod./marketing | Wine | 16,330,351 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 1.6 |

| P3 | Arable/Olive growing | EVO Oil | 57,479 | -212,470 | 4 | -4.33 | -2.18 |

| P4 | Milling | PDO Olive oil | - | - | - | - | - |

| P5 | Milling | EVO Oil | - | - | - | - | - |

| P6 | Prod./marketing | EVO Oil | 1,887,480 | 6,166 | 3 | 5.86 | 1.28 |

| T1 | Transformation | Artisanal Chips | 2,343,398 | 1,799 | 13 | 0.18 | 1.38 |

| T2 | Transformation | Cheese | 3,373,397 | 64,685 | 21 | 5.97 | 5.42 |

| T3 | Transformation | PGI pasta | 5,007,000 | 11,000 | 15 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| T4 | Transformation | Pasta | - | - | - | - | - |

| T5 | Milling | Olive oil | 398,139 | 79,856 | 3 | 34.99 | 17.34 |

| ICT1 | Traceability techn. | Cheese | 0 | -13,217 | 0 | - | -4.22 |

| ICT2 | Trust services | Various | 23,125,341 | 3,611,997 | 99 | 36.83 | 28.66 |

| ICT3 | IoT solutions | Pesto sauce | 45,455 | 13,464 | 0 | 92.57 | 56.49 |

| ICT4 | IoT solutions | 77,971,000 | -3,796,000 | -1.5 | -1.84 | ||

| C1 | C4 | C5 | CC1 | P2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary activities | |||||

| Inbound | Monitor weather conditions and collect field data | ||||

| Operation | Tracking grapes from harvest to wine production |

Partial integration of Industry 4.0 technologies in vinification and grape reception |

Managing certifications, traceability, and data monitoring (e.g., sustainability certifications, bottling, and stock management) | Implemented digital tools like the "Dioniso" database, inspection systems (PC, tablet), and AR/VR for vineyard monitoring and training |

Tracks production from grape reception to packaging, using barcodes to manage wine flow |

| Outbond | Managing distribution logistics | Use of QR codes on labels for regulatory purposes | Barcodes are used during the bottling process, and products are tracked until they reach the final packaging stage | ||

| Marketing | Enhance brand strength and market perception of the product |

Use of QR codes for commercial purposes | |||

| Service | Members support | Facilitate market analysis and ensure product traceability up to the consumer level (e.g., QR codes and digital labels for product information) | Use of digital platforms for traceability and certification, including tools for ensuring compliance with environmental and sustainability standards | ||

| Support activities | |||||

| Infrast. | Software systems for data management and process integration | Digital sensors for temperature monitoring | Implementation of software systems for administrative tasks, certification processes, and monitoring | Developed interoperable platforms, integrated data sources, and engaged in European projects | Data is stored on physical and virtual servers, managed by in-house software |

| Hum. Res. | Staff training | Training and use of external consultants for digital implementation | Collaboration with external consultants and use of software-specific support services | Internal quality and safety team, supported by external software and system consultants | |

| Tech. Dev. | QR code e smart labels |

Deployment of AR and VR tools for inspections and training, and use of digital loggers for monitoring conditions during product transport |

Uses manual and automatic systems for data entry and tracking, including readers in bottling | ||

| Proc. | Quality focus | ||||

| Value creation | Ensuring quality, efficiency, compliance, and market differentiation |

Improved product quality and process efficiency, better compliance with regulations |

Improved operational control, enhanced product quality, and increased compliance with market and regulatory demands |

Digital integration boosts efficiency, certification reliability, and environmental compliance, adding product value |

Improved production control enhances quality, safety, brand reputation, and regulatory compliance |

| Value capture | Enhancing relationships, brand reputation, pricing, and profit through efficiency | Increased market positioning, higher customer trust, and enhanced profitability |

Increased consumer trust, brand value, and market positioning through transparent product information |

Enhanced certification transparency strengthens market position, builds trust, and opens access to premium markets |

Better traceability and data management boost customer trust and market competitiveness, enhancing sales and positioning |

| A|1 | C7 | P1 | P3 | P4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary activities | |||||

| Inbound | |||||

| Operation | Blockchain tracks olive oil from harvest to bottling, including DOP and organic certifications | Use of the "Sian" system and blockchain to ensure traceability of olive oil from olive harvesting through milling, bottling, and storage, including quality checks and compliance with standards | The company, use sensors, digital records, and blockchain to track and document olive oil production from field to bottiling | Uses blockchain to trace olive oil from field to bottling, ensuring transparency and PDO/organic compliance through detailed documentation | Mandatory traceability through the "Sian" system, tracking olive oil production from harvest to bottling, including by-product and waste management |

| Outbound | |||||

| Marketing | QR codes on bottles link consumers to product origin and production details via blockchain | QR codes on bottles to provide consumers with access to product origin and production details, promoting transparency and enhancing the brand’s value | QR codes enable consumers to access detailed product information and traceability from bottle to olive tree via blockchain | QR codes on bottles allow consumers to access detailed information about the product's origin, production process, and quality metrics | |

| Service | Real-time updates to regulatory bodies via the "Sian" system, ensuring compliance and facilitating audits | ||||

| Support activities | |||||

| Infrast. | Internal servers and cloud systems manage data, integrated with SIAN for compliance | Data managed through internal servers, cloud systems, and FederItaly's blockchain platform, ensuring secure and reliable data storage and access. | Use of digital platforms for managing and storing data, including blockchain for secure and transparent data tracking | An external platform manages blockchain data, with documents digitized on internal servers before transfer | Use of internal servers and cloud systems for secure data management, with automated data transfer to external platforms |

| Hum. Res. | |||||

| Tech. Dev. | Field sensors monitor conditions in real-time for organic compliance, though data entry remains largely manual | Consideration of drones and other monitoring technologies for future implementation to improve agricultural monitoring and production forecasting | Deployment of sensors in the field for real-time data collection and integration with digital platforms for data management | Field sensors were discontinued due to poor results; QR codes now manage product identification and traceability | Sensors for temperature monitoring during the cold extraction process to ensure product quality |

| Proc. | |||||

| Value creation | Improved traceability and transparency enhance product quality and compliance | Enhanced traceability, product quality, and transparency through digital tools, contributing to stronger consumer trust and compliance with market regulations | Digital tools enhance traceability, quality assurance, and compliance, adding value through improved product transparency | Blockchain and QR codes boost transparency and traceability, meeting consumer demand and ensuring quality compliance, adding value | Enhances the traceability and quality control of the production process, adding value by ensuring the product meets high standards and is fully compliant with regulatory requirements |

| Value capture | Increased consumer trust and brand differentiation through transparency | Potential for premium pricing and market differentiation by leveraging transparency and product authenticity through digital traceability systems. | Digital traceability strengthens trust, justifies premium pricing, and improves market positioning | Digital tools enhance brand differentiation and loyalty, leading to better market positioning and premium pricing opportunities | Strengthened consumer trust and brand reputation, enabling market differentiation |

| E2 | ICT1 | T3 | T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary activities | ||||

| Inbound | Digital platforms monitor and track wheat production using field sensors and machinery data | |||

| Operation | Blockchain tracks cheese production from milk collection to processing, ensuring traceability of each step, including the specific cattle pasture | Blockchain tracks cheese production ensuring full traceability and transparency | Blockchain tracks the entire pasta production process, from wheat cultivation to manufacturing | |

| Outbond | Barcodes ensure traceability from packaging to distribution | |||

| Marketing | QR codes on cheese packaging provide consumers with detailed product information, including production process and origin | QR codes on cheese packaging give consumers access to detailed production information, enhancing product authenticity and market appeal | QR codes on pasta packaging provide consumers with detailed origin and production process information (wheat fields) | QR codes on packaging provide product origin and production details to consumers |

| Service | ||||

| Support activities | ||||

| Infrast. | Integration of blockchain with internal data systems to securely manage and store information related to dairy production and traceability | Use of internal servers and cloud systems integrated with blockchain to manage and secure data related to production and traceability | Integration of internal servers and blockchain platforms to manage, store, and secure data on wheat sourcing, milling, and pasta production | Integration of internal systems with external platforms for secure data management |

| Hum. Res. | ||||

| Tech. Dev. | IoT devices and sensors monitor cattle locations and behavior, linking pasture data to cheese production for enhanced traceability | Potential integration of IoT devices to improve data accuracy during milk collection and cheese production processes | Potential use of IoT devices and field sensors for crop monitoring, with much data entry still manual | Field sensors and advanced machinery enhance crop monitoring and yield data collection |

| Proc. | Integrating data from field sensors and machinery for real-time crop monitoring and planning | |||

| Value creation | Improved product traceability and quality control, enhancing consumer trust and product authenticity | Improved traceability and transparency strengthen product quality and compliance with industry standards | Blockchain-enhanced traceability boosts product quality, compliance, and consumer trust. | Integrated digital systems enhance traceability and quality control, boosting product reliability and consumer confidence |

| Value capture | Increased brand reputation and differentiation through transparency and detailed product information | Enhanced brand reputation and consumer trust through detailed, accessible product information | Increased brand reputation and market differentiation through transparency and authenticated product origin | Strengthened brand reputation and market differentiation through transparency and detailed product information |

| ID | Identification (TRUs) | Granularity of TRU | Data Recording | Integrating data | Data accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | Bottles, Batches (grapes, fermentation tanks, bottles), Process (QR codes, IDs) | Individual bottles, batches of grapes, fermentation tanks, bottle batches | Mixed: Manual entry + Automated systems (compliance-focused) | Moderate; challenges with interoperability | Variable: High for authorities, moderate for others (cloud-based) |

| ICT1 | Milk, batches of milk, cheese products (tracked via blockchain and QR codes) | Individual milk deliveries, processing batches, final cheese products | Manual entry, mobile apps, digital system mirrored on blockchain | Moderate; centralized database with blockchain mirroring, some manual processes | Moderate; QR codes provide consumer access, but blockchain data is encrypted and access-controlled |

| ICT4 | Batches of milk, Cheese products, batches of cheese during production and aging | Individual cheese products, batches during milk collection, processing, and aging | IoT devices, manual entry, centralized database, potential blockchain integration | Low-Moderate; combination of manual and digital processes, fragmented integration | Moderate; QR codes for consumer access, controlled blockchain access |

| P3 | Olive trees, batches of olives (based on harvest time), bottles | Individual bottles, batches of olives based on harvesting periods | Manual entry, digitalization by external service (EZ Lab) | Moderate; managed by external provider, manual to digital data transfer | Moderate; QR codes for consumers, centralized control by external provider |

| T3 | Wheat lots, batches of semolina, final pasta products | Individual wheat lots, semolina batches, pasta products | Manual entry, IoT devices, blockchain integration | Low-Moderate; manual data entry with some digital integration, potential for errors | Moderate; QR codes for consumer access, controlled access to detailed blockchain data |

| ID | Supply chain | Complexity of transactions | Supplier autonomy | Data intermediaries | Governance type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | Wine | High | Low | Integral; Central role of C5 | Captive network with elements of relational governance |

| ICT1 | Cheese | Moderate-high | Low | Integral with a central role | Mix of captive modular and relational |

| ICT4 | Cheese | Moderate-high | Low | Integral with a central role | Mix of captive and modular |

| P3 | Olive Oil | High | Low | Integral; Key role of external mill and certification bodies | Mix of captive and modular |

| T3 | Pasta | Moderate-high | Moderate-low | Critical role | Modular with some captive network elements |

| ID | C5 | ICT1 | ICT4 | P3 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased capacity | |||||

| Research/education | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Knowledge exchange | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Reduced costs | |||||

| Reduced variable cost | X | X | X | √ | X |

| Reduced fixed costs | X | X | X | X | X |

| Production resilience | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Financial resilience | - | - | - | - | - |

| Product differentiation valued by market | |||||

| Differentiation by traceability | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Enhance market access | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Enabling marketing opportunities | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Certification organic | X | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Certification animal welfare | X | √ | √ | X | X |

| Certification Sustainability | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Societal value and farmer well-being | |||||

| Enjoyment/improved well-being for farmer | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Community engagement | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Perceived environmental benefits by farmer | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Perceived animal welfare benefits by farmer | X | √ | √ | X | X |

| Government finance for digitalisation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Other support | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).