1. Introduction

In subtropical climates, land use in small farms is generally determined by agricultural activities practiced there [

1]. These activities are mainly characterized by extensive agricultural systems, where technology and mechanization in farming are limited. Animals are raised extensively, typically grazing on pasture and forest lands, and during certain periods of the year (off-season), they also graze in agricultural lands. This system allows small properties to be utilized to their full potential, increasing profitability, and is characterized as an integrated crop-livestock (ICL) system.

Worldwide, several alternative agricultural activities have emerged that are profitable for small properties, such as agroecological production [

2], crop diversification [

3], agroforestry systems [

4,

5], and the cultivation of cash crops, such as tobacco [

6]. In the subtropical zone, tobacco cultivation has become an important source of income for small farms, as with approximately 2.5 ha, it is possible to generate enough profit to sustain rural livelihoods in annual basis [

6]. It is worth noting that tobacco cultivation is a seasonal activity in south hemisphere, with planting in September and harvest ending in March (this cycle may vary depending on the region). From April to August, the period is referred to as the off-season, during which agricultural activities decline, leading to changes in land use throughout the year; thus, leaving space for the implementation of ICL farming.

During off-season, oats (like

Avena strigosa) are seeded in agricultural land, in a density of 80 kg ha

-1, approximately to serve as pasture during the winter. When preparing the soil for the next crop, animals are kept in adjacent natural pastures and forest lands, and this rotation continues. This ICL farming system has been widely adopted in small farms; in southern Brazil, the system stands out, as most of summer croplands are left fallow during the winter due to climatic conditions [

7].

It is important to note that ICL systems aim to develop interactions between their components (crops, pastures, and animals) [

8] with the goals of improving environmental conditions and farm profitability [

9]. The adoption of ICL land use can enhance production processes, including labor efficiency, economic stability, and risk reduction. This land use type shows potential for increasing profitability and improving environmental conditions [

10].

Numerous studies have been conducted in recent years on ICL systems, addressing topics, such as carbon sequestration [

11,

12,

13], carbon's role in soil aggregates [

14], sustainable land use [

15], soil quality [

16,

17], soil properties [

18], soil acidification [

19], synergy between agricultural production and environmental quality [

20], and economic profitability [

21]. Therefore, the adoption of ICL systems have been proposed as a strategy for achieving agricultural sustainability, while maintaining productivity [

22]. However, research which evaluates the changes in soil quality and infiltration rates throughout the year in subtropical agricultural, pasture, and forest lands that are experiencing ICL farming is still scarce [

23].

Therefore, this research aimed to identify how grazing influences soil density and water infiltration rates across different land-use types (pasture, forest, eucalyptus reforestation, and agriculture) during the tobacco growing season and the off-season (when grazing occurs in agricultural land) on a small property in the Boa Vista River Basin, Southeast Paraná region, Brazil. To achieve these objectives, it was necessary to: a) identify the behavior of animals during grazing; b) assess the availability of forage; and c) measure soil conditions before and after grazing. We hypothesized that the physical quality of the soil in subtropical areas, determined by the implementation of ICL farming, is influenced by variations in land use, particularly when animals are introduced for grazing exclusively in off-season crop cultivated land.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was carried out between May 2023 and April 2024. This period corresponds to the period for tobacco cultivation. Field activities were carried out every month; activities related to the estimation of forage availability, monitoring of animal behavior, collection of soil to assess soil density and moisture, and measurement of the water infiltration rate. These three parameters were measured in rotational grazing, as they are more easily affected and altered by animal grazing.

2.1. Study Area

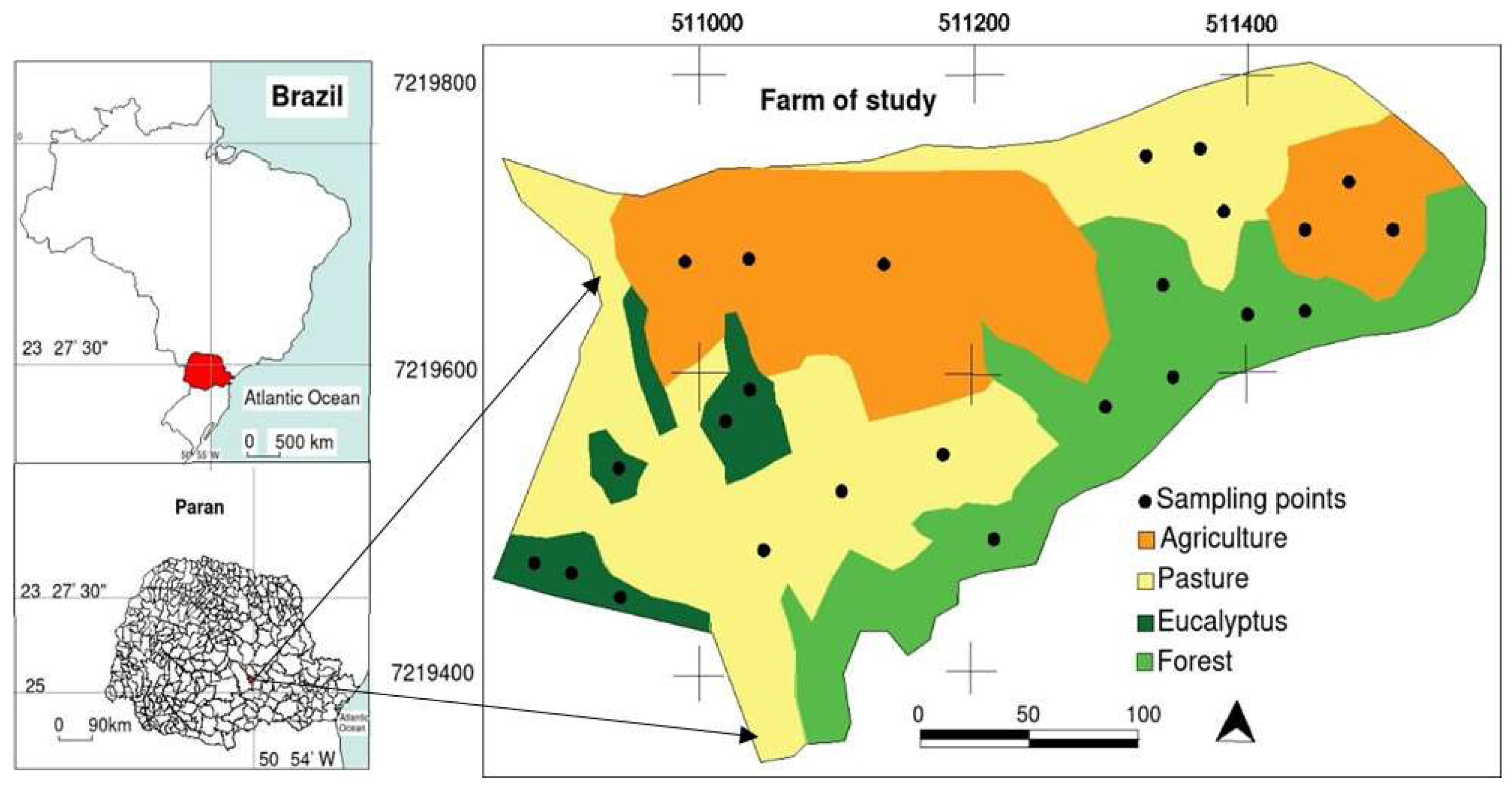

The small farm used in this research is located in the Boa Vista River Basin, municipality of Guamiranga, S.E. Paraná region, Brazil, (25º08’22” S; 50º 53’30” W, elevation 815 m a.s.l.). The study area is located in the Paraná sedimentary basin and on the western edge of the Second Paraná Plateau. This condition contributes to the formation of steep reliefs and shallow soils. This farm was chosen due to its representativeness of the characteristic small farms in the basin, where approximately 75% of the farms rely on tobacco cultivation, as their main source of income.

The area of the farm is 9 ha, consisting of 2.5 ha of

Araucaria forest, 1 ha of

Eucalyptus reforestation with perennial grassland, 2.3 ha of pasture (perennial grassland), and 3.2 ha of agricultural land (

Figure 1). In the pasture, forest, and eucalyptus reforestation, animals are raised extensively, including 15 dairy cattle and 2 horses used for animal traction in agricultural activities.

During the tobacco planting season, from September to March (spring and summer), the animals are confined to pasture and forest lands, with a stocking rate of approximately 2.5 AU ha

-1. After the tobacco cultivation ends in March, the soil is tilled, and the annual bristle oat (

Avena strigosa) is sown in a seed density ~ 60 kg ha

-1. From May to August, the animals were confined to agricultural land in a rotational grazing system. The area is divided into 4 fenced plots of approximately 0.7 ha. The animals remain in each plot for about 10 days. The stocking rate in the agricultural area is 4.6 AU ha

-1. During this period, the pasture and forest lands are not subjected to grazing (

Table 1).

The ICL system consists of a fragment of

Araucaria forest, predominantly featuring tree species, such as

Araucaria angustifolia,

Campomanesia xanthocarpa,

Casearia sylvestris,

Ocotea puberula, and

Rapanea ferrugínea. The pasture is composed of the subtropical perennial bahiagrass (

Paspalum notatum) [

24].

Growing Eucalyptus grandis is a common practice among local tobacco producers, as they use its wood to generate energy for drying tobacco leaves. The average wood consumption per tobacco harvest is approximately 60 m³ (50 trees approx.). Eucalyptus reforestation is typically organized on small plots, within the animal grazing areas. There is a rotation for cutting eucalyptus trees for firewood during the tobacco season, with a cycle of approximately 8 years (pers. com.).

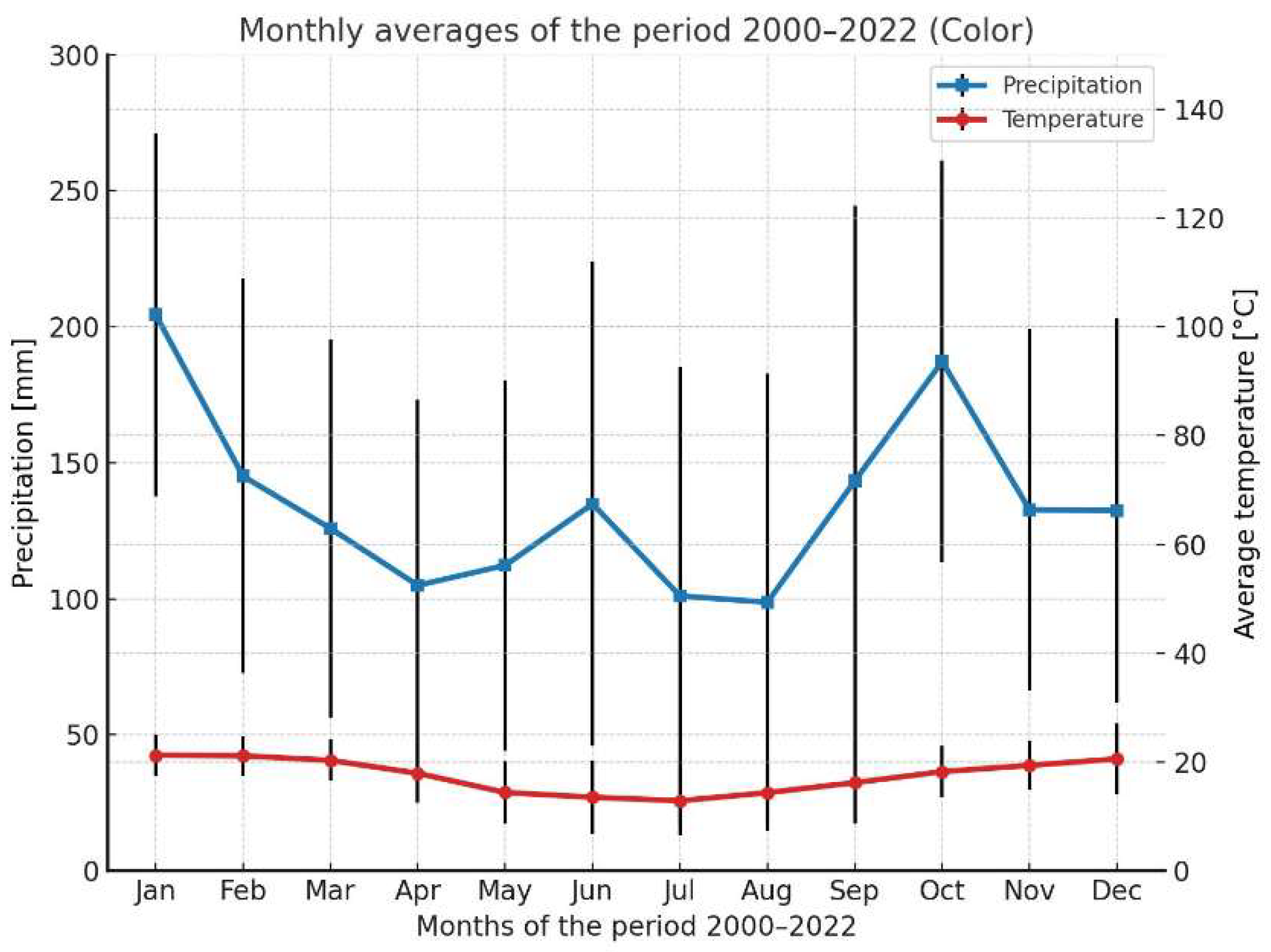

The region's climate is classified as Cfb – Humid Subtropical without a dry season, with summer temperatures below 22 °C, and frost occurring during the colder months (

Figure 2). The cold period with the occurrence of frosts, influencing the agricultural dynamics of the region. Some physical characteristics of the examined property are presented in

Table 2.

2.2. Experimental Design

Two data collection campaigns were conducted, at the beginning (May) and the end (August) of grazing period. Soil density, antecedent soil moisture, and water infiltration rate in the soil were estimated. In both campaigns, 6 randomly selected collection points were identified in each land type. Soil density and moisture samples were collected at depths of 0-10, 10-20, 20-30, and 30-40 cm, totaling 40 samples per campaign for each land use type. The infiltration rate was measured at the same points where soil samples were collected, with 6 repetitions per area, totaling 18 infiltration measurements per campaign.

2.3. Animal Grazing Dynamics

Throughout the study, the animals’ grazing behavior was monitored. Two individuals (cattle) were selected each day for monitoring, and their daily behavior was tracked by the means of GPS attached in collars. Horses were not evaluated, as they were primarily engaged in agricultural activities during most of the time. In each season, 4 monitoring days were selected, totaling 16 days of evaluation. The monitoring of animal behavior was conducted from the moment the animals leave the stables for the pastures (in the morning) until they return in the afternoon. The monitoring period was approximately 10 hours. The animals were observed throughout the day, and a stopwatch was used to record the time spent in each area (pasture and forest). Additionally, the locations and times when the animals rested were recorded.

2.4. Forage Availability

Forage availability was expressed as above-ground biomass (AGB) of fresh forage. Throughout the year, data collection campaigns were conducted to assess AGB in native pastures, forest lands and oat crops. All available AGB within a 1x1 m² area were collected and immediately weighed. AGB was expressed in kg ha-1. Two data collection campaigns were conducted for each land type: one before livestock were introduced into pastures and forests (August) and another immediately after livestock were removed from pastures and forests (May). In agricultural land, data were collected at the beginning of grazing (May) and ending in August. In each campaign, samples were collected from 10 points in each land type. Oat volume was collected before livestock was introduced (May) and after the end of grazing activity (August).

2.5. Soil Bulk Density

To measure soil bulk density, samples were collected randomly at 6 points in each land type, totaling 24 samples for each land type in each campaign. Soil density was determined using the volumetric ring method [

25]. Undisturbed soil samples were collected using an iron ring with a volume of 100 cm³. Each sample was taken to the laboratory for analysis, weighed, and placed in an oven to dry at 105 ºC. After 24 hours, the samples were removed and weighed again. To calculate the bulk density, the mass of the soil was divided by the volume of the ring (g cm

-3).

2.6. Water Infiltration and Antecedent Moisture

The infiltration rate was measured near points where soil was collected for bulk density analysis. Six replicates were performed for each land use, totaling 24 replicates in each campaign. The collection periods were also the same (beginning and end of grazing).

To evaluate water infiltration in the soil across different land types, a manual double-ring infiltrometer was used, consisting of two cylinders: one with a diameter of 400 mm and the other with 900 mm, along with a graduated burette to measure the volume of water added to the inner cylinder (400 mm). The purpose of the outer ring (900 mm) is to generate only vertical flow in the smaller ring (400 mm), reducing the lateral flow of water into the soil. The measurement duration was 1 h, with readings taken every 5 min. The surface soil moisture on the data collection days was measured using a soil moisture sensor HOBOnet T11 model, with 10 repetitions at each measurement point.

2.7. Data Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA one-way) was employed to compare bulk density, soil water infiltration, forage quantity, and livestock dynamics among land uses. The statistical significance of the comparison of means between groups was conducted through a Tukey test of a significance level below 5% probability.

3. Results

3.1. Animal Grazing Dynamics

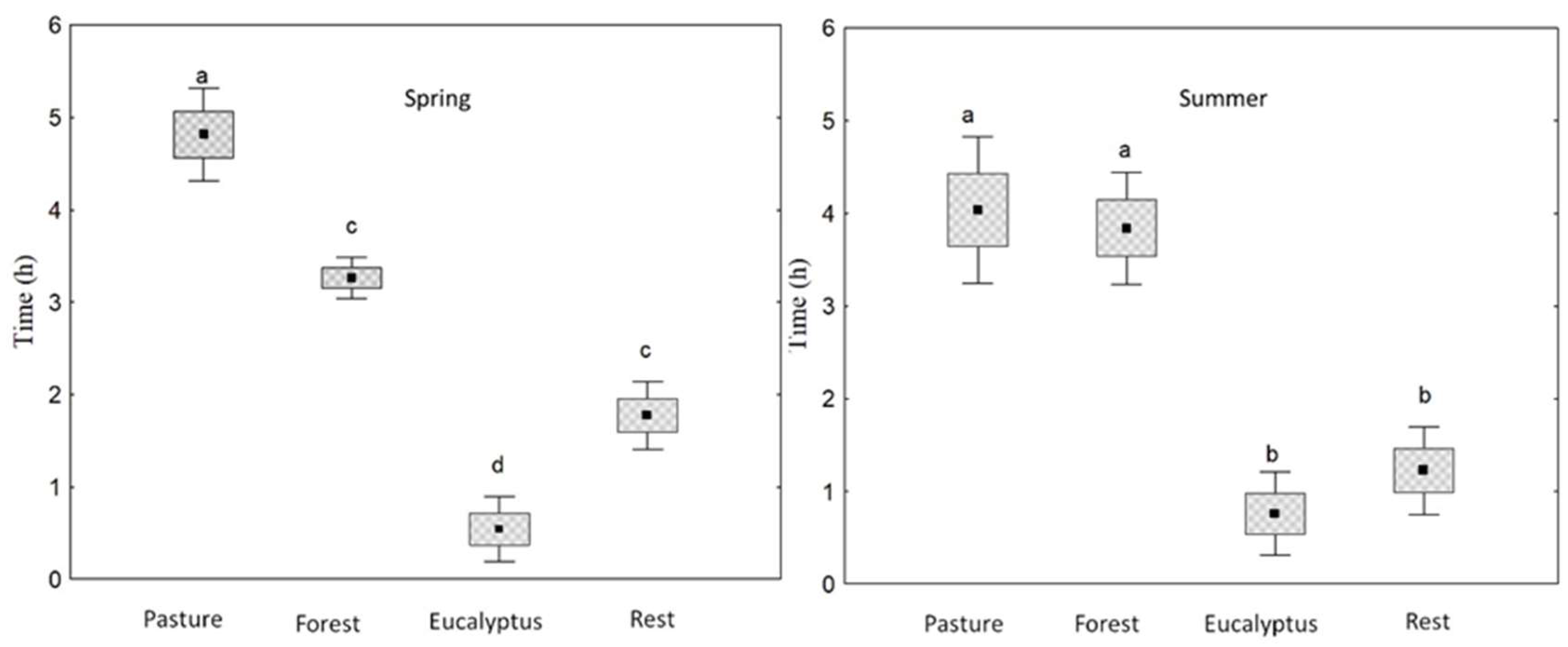

The change in land use of small rural properties throughout the year affects the dynamics of grazing animals. From September to March (spring to summer), tobacco is cultivated in agricultural land. During this period, animals graze in pastures and forests in daytime, while they return to stables and stay overnight.

The grazing time in spring was 10.25 h. Of this total, 47.6% of the time was spent in pastures, 29.9% in the forest, 5.3% in eucalyptus reforestation, and 17.2% in resting (lying down). Of the total rest time, 74% occurred in the pasture and 26% in the forest. The time spent grazing by animals during the summer was 10.42 h. In this period, 39.2% of the time was spent in pastures, 35.4% in the forest, 10.3% in eucalyptus reforestation, and 15.1% in resting. Of the total resting time, 82% was spent in the forest and 18% in the pasture (

Figure 3).

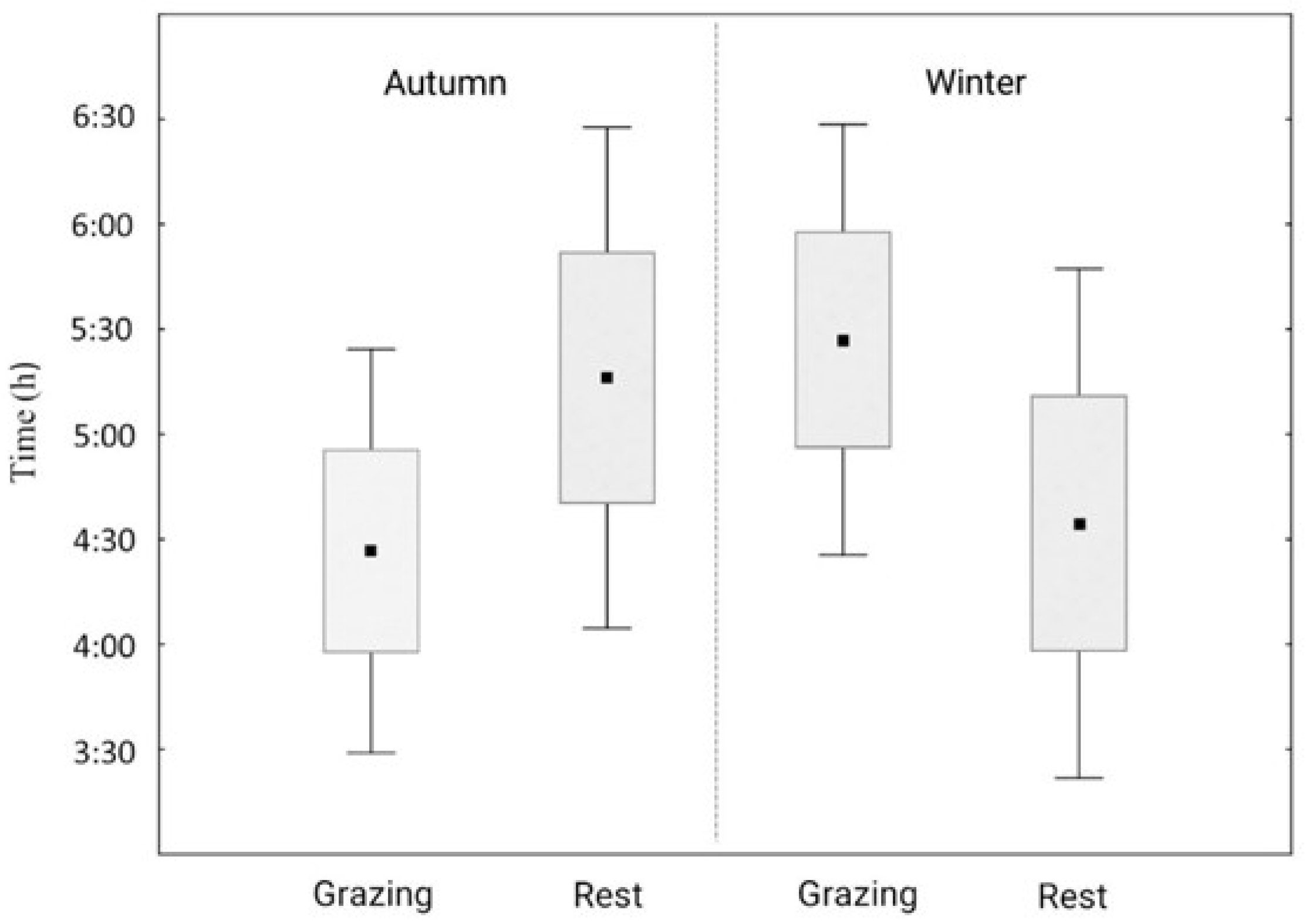

In May, i.e. at the end of the tobacco cultivation and the beginning of oats cultivation, the animals were transferred to the agricultural land for grazing. They were left grazing until August, when the farmer prepared the soil for tobacco cultivation again. The daily routine of the animals grazing in the agricultural land was similar to that in native pastures. During the night, they were confined to the stables and in the morning, they were taken out to graze. The animals were confined only to the agricultural land, without contacting native pasture and forest. Grazing duration in the agricultural area during the autumn was 9.50 h. Of this total grazing time, 46.5% was for grazing, while 53.5% was for resting. The average grazing time for the animals during winter was 9.28 h (

Figure 4).

When comparing the behavior of the animals between the two seasons (

Figure 3), it was observed that in autumn, the animals rested for a longer duration than in winter (2.08 h) However, in winter, the opposite happened, with the majority of the time to have been spent for grazing (1.06 h).

3.2. Forage Availability

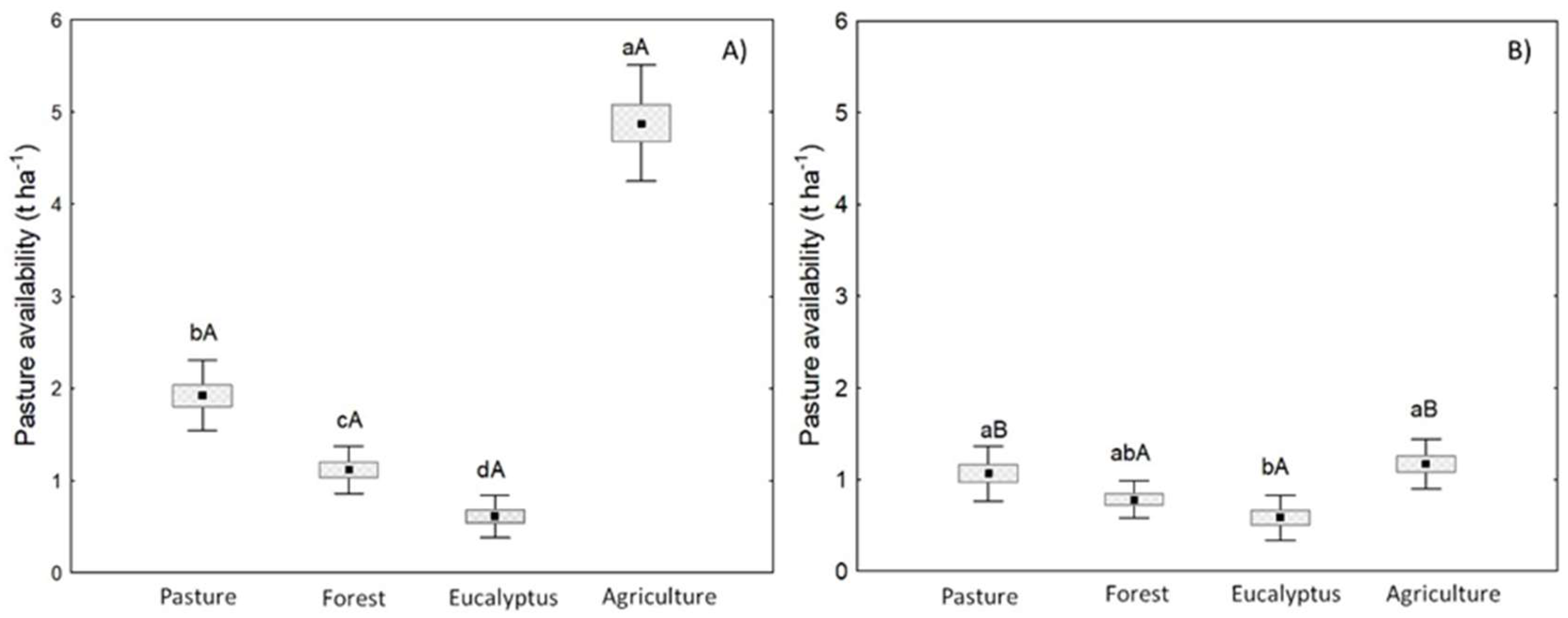

Forage productivity at the beginning of grazing period (September) showed a significant variation among land types (

Figure 5). The eucalyptus reforestation indicated the lowest biomass values (0.61 t ha⁻¹), followed by the forest with an average of 1.11 t ha⁻¹, and pastures of 1.92 t ha⁻¹. In contrast, forage biomass, provided from oat cultivation, was 4.87 t ha⁻¹.

After the end of grazing period (April), forage biomass showed a significant reduction in both, the pasture (1.01 t ha⁻¹) and the forest area (0.78 t ha⁻¹). In the eucalyptus reforestation, the biomass provided at the end of grazing was similar to that recorded at the beginning of grazing (0.57 t ha⁻¹).

Forage availability in the pasture at the end of the grazing period was 92% lower compared to the beginning of the grazing. A significant reduction was also found in the forest between the two time periods. In contrast, no significant variation was observed in the eucalyptus reforestation between the two time periods (

Figure 4).

The greatest variation occurred in the agricultural land, where the availability of forage (oats) at the beginning of grazing period was 4.98 t ha⁻¹, while at the end it was 1.17 t ha⁻¹, i.e. 4.2 times lower (

Figure 4). Our findings indicate that the forage availability at the end of grazing in the agricultural area was similar to the values found in the pastures after grazing.

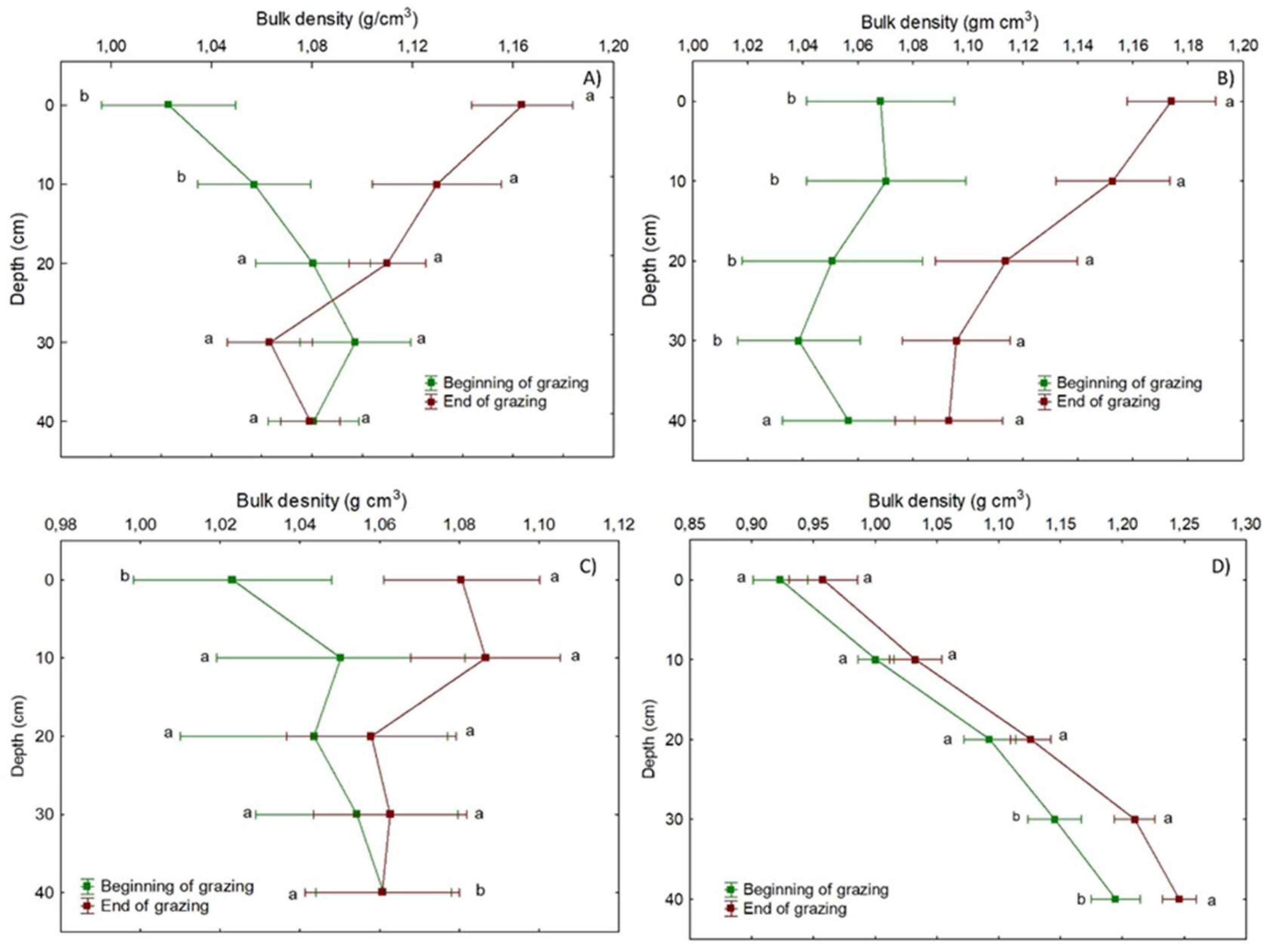

3.3. Soil Bulk Density

The greatest variation in soil bulk density between the two periods was observed in the agricultural land, followed by the pasture, forest, and eucalyptus reforestation. The soil density after grazing in the agricultural land was 58% greater than the beginning of grazing. However, there was no variation starting from a depth of 20 cm. The lowest variation was observed in the eucalyptus reforestation, where the data did not show significant variation in the upper layers (0 to 20 cm depth) (

Figure 6).

At the end of the grazing period, an increase in soil bulk density up to a depth of 30 cm was indicated for the pasture. At the soil surface, the increase was 83.2% compared to the fallow period. This variation decreased along the soil profile. The smallest variation between the two periods was observed in the eucalyptus reforestation.

3.4. Water Infiltration and Antecedent Moisture

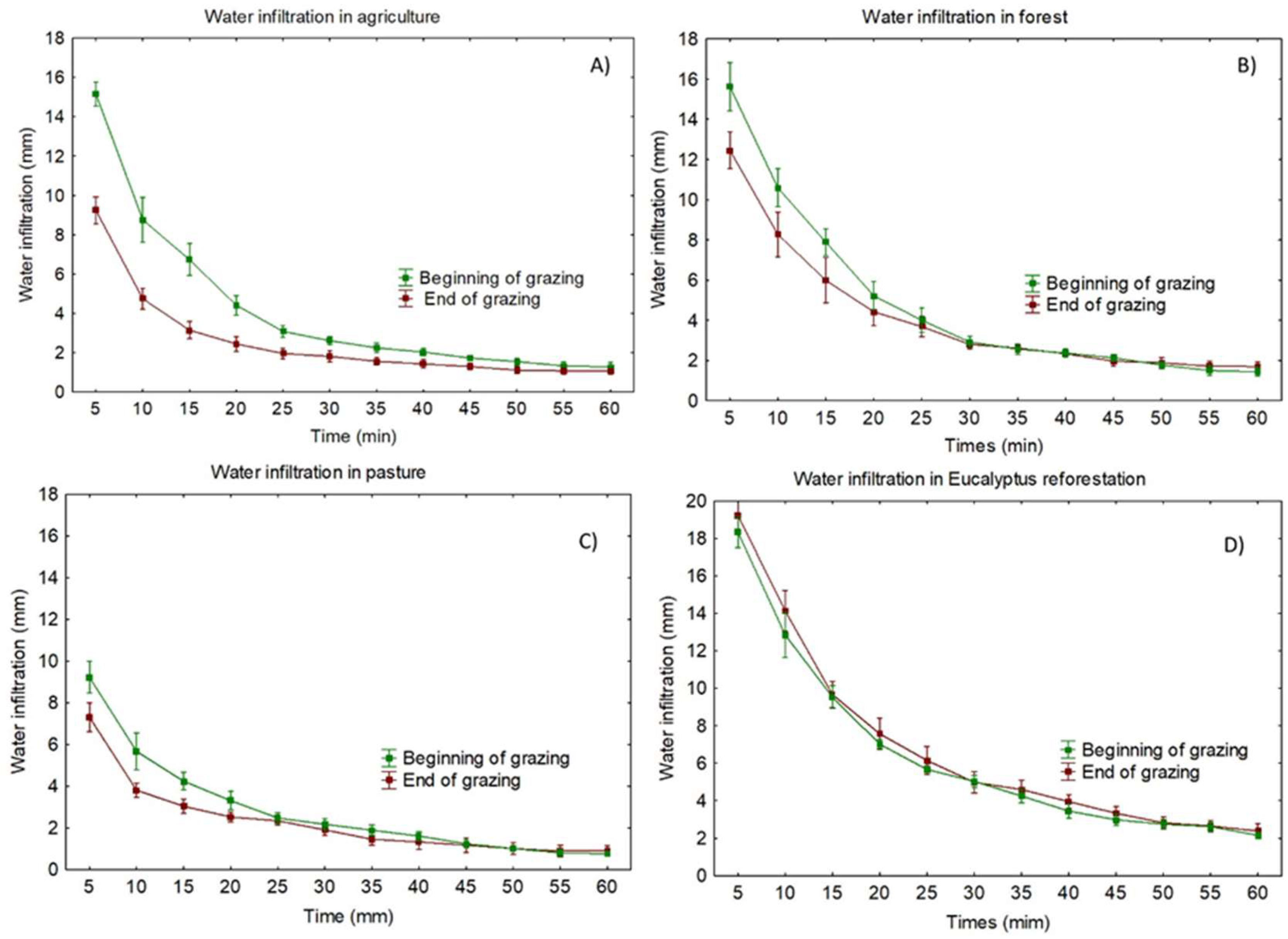

The highest water infiltration rate was observed in the eucalyptus reforestation (76.8 mm h

-1) at the beginning of the grazing period (September), while the lowest rate was found in the agricultural land at 29.8 mm h

-1 at the end of the animals' grazing (March) (

Figure 6). The agricultural area exhibited the greatest variation in total infiltration rate between the two periods. At the beginning of grazing, total infiltration in agriculture was 59.5 mm h

-1, while at the end of grazing, it decreased to 29.8 mm h

-1 (a reduction of 99.6%). The forest showed the least variation, with the infiltration rate at the beginning of grazing being 5.5% lower than during grazing (

Figure 7).

Infiltration rate showed significant variation for up to 40 min of monitoring in agricultural land; after this period, the values were similar. In forest and pasture, this variation occurred for up to 15 min, indicating similarity after that period. The eucalyptus reforestation did not show significant variation between the two collection periods (

Figure 6).

The total soil moisture throughout the profile did not show significant variation, at the significance level of 5%. The highest soil moisture rate was observed in the

Eucalyptus reforestation (32 mm h

-1), coinciding with the highest infiltration rates, followed by the forest (28.5 mm h

-1, approx.), agriculture (27.3 mm h

-1), and the pasture with the lowest soil moisture (22 mm h

-1) (

Figure 6).

3.5. Relationships Between Variables

Correlation coefficients revealed that forage volume appeared to be the factor with the greatest influence on grazing time (r = 0.852, p < 0.05), soil density (r = 0.784, p < 0.05) and infiltration rate (r = 0.795, p < 0.05) (

Table 3). On the contrary, pasture availability did not present a significant correlation with soil moisture (r = 0.384, p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Numerous studies around the world have indicated the influence of climate and geographic location on pasture availability [

26,

27]. In subtropical regions, low temperatures during the colder months reduce pasture availability [

28] leading animals to move more in search of food, thereby altering the environmental conditions of the soil. These conditions prompt small farmers to use agricultural lands as pastures during the colder months, leaving pastures and forests fallow.

In subtropical regions, tobacco is cultivated during spring and summer, and the animals are left grazing in pastures and forests. Our findings show that during spring and summer, animals exhibited different behaviors. The time they spent in pastures during spring was 8% higher than in summer. On the other hand, the time spent in the forest during spring was 6% lower.

There was also a significant variation in the resting time, which was 92% higher in spring compared to summer. The resting locations were inversely related; in spring, most resting time was in open pastures, while in summer, most resting time was in the forest. This animal behavior is probably due to two reasons. Forage availability in summer is generally less than spring; animals spend more time for fresh green forage, and also are getting more relaxed in open pastures. The greater the pasture availability in spring, the lower the mobility of animals within the forest. Therefore, weather conditions such as climate conditions and pasture availability can affect cattle behavior in relation to the time dedicated to rest and grazing [

29]. In summer, forage availability of pastures decreased, and animals used the forest more in search of food and also for protection [

30]. Also, the thermal stress is higher in summer than in spring; animals are used to rest in forests.

In summary, the variation in animal mobility among the seasons can be attributed to climatic conditions, as during the warmer periods, animals tend to use the forest for resting, alleviating thermal stress [

31]. Pastures associated with forest fragments provide forage, shade, and shelter for animals, thus improving their thermal comfort during the hottest hours of the day [

32], as well as on cold and rainy days [

33,

34]. Forests, used for extensive livestock grazing, consist of small fragments with sparse trees and no lower strata (understory and herbaceous plants).

The limited time that animals spent in eucalyptus reforestation was due to the lack of forage. The density of the planting, the layer of litter on the surface, and competition for water and nutrients hindered the development of grasses [

35]. During the evaluation of animal behavior, it was observed that the eucalyptus reforestation was used mostly for shelter, during certain hours of the day.

In agricultural land (autumn and winter), the behavior of animals differed in relation to native pastures. In autumn, the resting time of animals was higher than their grazing time. This condition is related to forage availability, which during autumn was four times higher compared to summer (end of grazing in agriculture). Therefore, forage availability affects grazing time [

26,

37,

38].

The dynamics of animal grazing in different land uses altered certain soil parameters, such as soil density and water infiltration rate. Our findings indicate that at the end of grazing activity (summer) in pastures, there was an increase in soil density of about 83%, while in the forest, the alteration was only observed in the surface layer of the soil. In eucalyptus reforestation, the data were similar in both periods, due to the limited movement of animals, and also to low forage availability. During spring, the variation in soil density in pastures is indirectly regulated by the greater forage availability and longer animal presence. In summer, animal movement times have the same pattern; however, soil density in the forest was lower than in pastures.

The forest maintains soil moisture, and through the accumulation of litter and organic matter on the soil surface, it alters the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil [

39]. Conventional soil preparation reduces soil density and surface compaction [

40]. In the current study, a leveling harrow was used, which only disturbs the surface layer of the soil (~15 cm deep) [

41,

42]. The findings showed that soil density, at the beginning of grazing in agriculture, was 53% lower than that at the end of grazing. However, this variation was observed only at a depth of up to 15 cm. Beyond this depth, the soil maintained the same density pattern.

Soil compaction, due to trampling and reduced pasture availability, can lead to higher exposure of the soil surface, interfering with hydrological and geomorphological dynamics. Changes in the physical structure of the soil affect the water retention rate in soils, reduce water infiltration, and enhance surface runoff and soil loss [

43,

44,

45]. In agricultural land, the soil exhibited increased compaction and reduced infiltration rates at the end of grazing activity. The data appeared to be higher than those found in the literature under tobacco cultivation [

6,

46]. Our findings suggest that agricultural machinery should be used to remove the compacted soil layer left by animal trampling in the preparation for the next crop.

Rotational systems with grazing and fallow periods, like the regime imposed by ICL farming, could be a significant alternative for reducing the impact of grazing animals on soil physical properties. It seems to allow for greater recovery of forage compared to continuous grazing systems found in the literature [

47], which could contribute to improving soil structure and hydrological dynamics. These improvements reflect on the profitability of herding activity, and underpin the significance of ICL as a sustainable farming system towards soil integrity in subtropical regions.

Therefore, this study investigates the influence of animal behavior on soil quality within Integrated Crop-Livestock (ICL) systems, implemented on smallholder farms engaged in tobacco cultivation. Emphasis was placed on evaluating the effects of intermittent grazing, considering the unique characteristics of such systems. Observations focused on daytime animal behavior, as livestock were confined to stables during nighttime hours.

The findings underscore the importance of animal management practices in maintaining soil health and suggest that behavioral patterns can serve as indicators of system sustainability. The study also highlights key directions for future research, including variations in stocking density, full-time behavioral monitoring, the role of vegetation structure in pasture quality and thermal comfort, pre-grazing soil conditions shaped by tobacco cultivation, and the influence of forage diversity on animal behavior. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between livestock management and soil conservation in diversified agricultural systems.

5. Conclusions

Pasture availability and climatic conditions determined the grazing time in pasture and forest lands in subtropical areas, experiencing an ICL farming regime. The higher the volume of forage, the lower time animals spent grazing and the more time animals spent resting.

The best soil conditions, in terms of soil density and water infiltration rates were found in eucalyptus reforestation. This improvement emerged due to the limited time animals spent in this land type.

Intensive grazing in agricultural land during the tobacco off-season increased soil density and reduced infiltration rate. There was also a variation between the grazing time and resting time of animals. This condition can be attributed to forage availability and the lack of trees for animals to use as shelter and resting places.

ICL farming systems applied throughout the year seems to create positive conditions for soil quality. The fallow periods improved soil condition, increased forage availability, and maintained higher soil moisture. These conditions helped to increase the water infiltration rate in the soil.

Therefore, of the ICL systems in subtropical areas that include pasture rotation combined with forests and grazing in agricultural lands during the off-season on small farms appears to be a sustainable alternative for improving environmental soil conditions and maintaining pastures, as well as potentially improving her quality in order to increase profitability. However, further research is necessary to explore the impact of this farming system in other properties of the soils, like the chemical ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A., L.M.G. and J.A.B.; methodology, V.A and J.A.B.; validation, V.A., L.M.G. and J.A.B.; formal analysis, L.M.G.; investigation, V.A.; resources, V.A.; data curation, V.A. and J.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A, M.P.C.M. and M.V.; writing—review and editing, M.V, A.K. and M.P.C.M; visualization, V.A.; supervision, V.A.; project administration, V.A. and M.V.; funding acquisition, V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Araucaria, Foundation Paraná Government, grant number Public Call n. 09/2021. Agreement 378/2021.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kirkman, K.P.; Fynn, R.W.S.; McGranahan, D.; O’Reagain, P.J.; Dugmore, T. Future-proofing extensive livestock production in subtropical grasslands and savannas. Animal Frontiers. 2023. 13, 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Durham, T.C.; Mizik, T. Comparative economics of conventional, organic, and alternative agricultural production systems. Economies 2021, 9, 64. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Orsi, L.; Ferrazzi, G.; Corsi, S.; The dimensions of agricultural diversification: A spatial analysis of Italian municipalities. 2020. Rural Sociology, 85, 316-345. [CrossRef]

- Kokkora, M.I.; Vrahnakis, M.; Kleftoyanni, V. Soil quality characteristics of traditional agroforestry systems in Mouzaki area, central Greece. Agroforestry Systems, 2022. 96, 857-871. [CrossRef]

- Tsiakiris, R.; Stara, K.; Kazoglou, Y.; Kakouros, P.; Bousbouras, D.; Dimalexis, A.; Dimopoulos, P.; Fotiadis, G.; Gianniris, I.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Mantzanas, K.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Tzortzakaki, O.; Vlami, V.; Vrahnakis, M. Agroforestry and the climate crisis: Prioritizing biodiversity restoration for resilient and productive Mediterranean landscapes. Forests 2024, 15, 1648. [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, E.; Antoneli, V. Long-term soil quality decline due to the conventional tobacco tillage in Southern Brazil. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science. 2022. 68, 719-731. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.d., Carvalho, P.C.d.F., Lustosa, S.B.C., Lang, C.R., Deiss, L. Research on Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems in Brazil. Revista Ciência Agronômica. 2014. 45. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Moraine, M.; Ryschawy, J.; Magne, M.A.; Asai, M.; Sarthou, J.P.; Duru, M.; Therond, O. Crop–livestock integration beyond the farm level: a review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 2016. 36, 53. [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M. Factors Influencing Farm Profitability. In: Lichtfouse, E. (eds) Sustainable Agriculture Reviews. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, 2015, vol 15. Springer, . [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Epper, C.A.; Tschopp, D.J.; Long, C.T.M.; Tungani, V.; Burra, D.; Hok, L.; Phengsavanh, P.; Douxchamps, S. Crop-livestock integration provides opportunities to mitigate environmental trade-offs in transitioning smallholder agricultural systems of the Greater Mekong Subregion. Agricultural Systems, 2022. 195, . [CrossRef]

- Brewer, K.M.; Gaudin, A.C.M. Potential of crop-livestock integration to enhance carbon sequestration and agroecosystem functioning in semi-arid croplands. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2020. 149, 107936. [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J.M.; Anghinoni, I.; Martins, A.P.; Costa S.E.V.G.de A.; Cecagno D.; Carlos F.S.; Carvalho P.C. de F. Soil carbon and nitrogen stocks and fractions in a long-term integrated crop–livestock system under no-tillage in southern Brazil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014. 190. 52–59. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zheng,H,; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y,Z.; Han, H.; Ning, T. Crop – Livestock integration via maize straw recycling increased carbon sequestration and crop production in China. Agricultural Systems, 2023. 210, 103722. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Chakraborty, P.; Kumar, S. Crop–livestock integration enhanced soil aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen, and phospholipid fatty acid. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12, 2781. [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, J.C.; Rodrigues, G.S.; de Barros, I.; Rodrigues, R. de A.R.; Garrett, R.D.; Valentim, J.F.; Kamoi, M. Y.T.; Michetti, M.; Wruck, F.J.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Pimentel, P.E.O.; Smukler, S. Integrated crop-livestock systems: A sustainable land-use alternative for food production in the Brazilian Cerrado and Amazon. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021. 283, 124580. [CrossRef]

- Buller, L.S.; Bergier, I.; Ortega, R.; Moraes, A.; Bayma-Silva, G.; Zanetti, M.R. Soil improvement and mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions for integrated crop–livestock systems: Case study assessment in the Pantanal savanna highland, Brazil. Agricultural Systems, 2015. 137, 206-219. [CrossRef]

- Simões, V.J.L.P.; de Souza, E.S.; Martins, A.P.; Tiecher, T.; Bremm, C.; da Silva Ramos, J.; Duarte Farias, G.; de Faccio Carvalho, P.C. Structural soil quality and system fertilization efficiency in integrated crop-livestock system. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2023, 349, 108453. [CrossRef]

- Ambus, J.V.; Reichert, J.M.; Gubiani, P.I.; de Faccio Carvalho, P.C. Changes in composition and functional soil properties in long-term no-till integrated crop-livestock system. Geoderma, 2018. 330, 232-243. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; de Andrade Costa S.E.V.G.; Anghinoni, I.; Kunrath, T.R.; Balerini, F.; Cecagno, D.; Carvalho, P.C.d.F. Soil acidification and basic cation use efficiency in an integrated no-till crop–livestock system under different grazing intensities. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2014, 195, 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, G.; Franzluebbers, A.; Carvalho, P.C.d.F.; Dedieu, B. Integrated crop–livestock systems: Strategies to achieve synergy between agricultural production and environmental quality. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2014, 190, 4–8. [CrossRef]

- Simioni, F.J.; Bartz, M.L.C.; Wildner, L. do P.; Spagnollo, E.; Veiga, M. da .; Baretta, D. Economic and soil quality indicators in soybean crops grown under integrated crop-livestock and winter-grain cultivation systems. Ciência Rural. 2016, 46 (7), 1165–1171. [CrossRef]

- Sulc, R.M.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Exploring integrated crop–livestock systems in different ecoregions of the United States. European Journal of Agronomy, 2014, 57, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.B.; Pontius, J.; Galford, G.L.; Merrill, S.C.; Gudex-Cross, D. Modeling carbon storage across a heterogeneous mixed temperate forest: the influence of forest type specificity on regional-scale carbon storage estimates. Landscape Ecology, 2018, 33, 641–658. [CrossRef]

- Antoneli, V.; Pulido Fernández, M.; de Oliveira, T.; Lozano-Parra, J.; Bednarz, J.A.; Vrahnakis, M.; García-Marín, R. Partial grazing exclusion as strategy to reduce land degradation in the traditional Brazilian faxinal system: Field data and farmers’ perceptions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7456. [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA, Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solo. 2ª ed. Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Solos, Rio de Janeiro. 1997. (in portugues).

- Chang-Fung-Martel, J.; Harrison, M.; Rawnsley, R.; Smith, A.; Meinke, H. The impact of extreme climatic events on pasture-based dairy systems: a review. Crop and Pasture Science. 2017, 68, 1158 - 1169. [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, K., Samireddypalle, A. Impact of Climate Change on Forage Availability for Livestock. In: Sejian, V., Gaughan, J., Baumgard, L., Prasad, C. (Eds.), Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation. Springer India, New Delhi, 2015 pp. 97–112.

- Churchill, A.C. Zhang, H.; Fuller, K.J.; Amiji, B.; Anderson, I.C.; Barton, C.V.M.: Carrillo, Y.; Catunda, K.L.M.; Chandregowda, M.H.; Igwenagu, C.; Jacob, V.; Kim, G.W.; Macdonald, C.A.; Medlyn, B.E.; Moore, B.D.; Pendall, E.; Plett, J.M.; Post, A.K.; Powell, J.R.; Tissue, D.T.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Power, S.A. Pastures and climate extremes: Impacts of cool season warming and drought on the productivity of key pasture species in a field experiment. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.K.; Scharf, B.; Eichen, P.A.; Spiers, D.E. Relationships between ambient conditions, thermal status, and feed intake of cattle during summer heat stress with access to shade. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2017, 63, 104–111. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.D.; Schlecht, E. Livestock mobility in sub-Saharan Africa: A critical review. Pastoralism, 2019, 9, 13. [CrossRef]

- Herbut, P.; Hoffmann, G.; Angrecka, S.; Godyń, D.; Corrêa Vieira, F.M.; Adamczyk, K.; Kupczyński, R. The effects of heat stress on the behaviour of dairy cows – a review. Annals of Animal Science, 2021, 21, 385–402. [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M.; Schmitt Filho, A.L.; Hötzel, M. J.; de Sousa, K. T.; Pinheiro Machado Filho, L.C.; Sinisgalli, P.A. Microclimate and pasture area preferences by dairy cows under high biodiversity silvopastoral system in Southern Brazil. Int J Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1877–1887. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, K.T.; Deniz, M.; Vale, M.M.d.; Dittrich, J.R.; Hötzel, M.J. Influence of microclimate on dairy cows’ behavior in three pasture systems during the winter in south Brazil. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2021, 97, 102873. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, C.A.; Zolin, C.A.; Lulu,J.; Lopes, L.B.; Furtini, I.V.; Vendrusculo, L.G.; Zaiatz A.P.S.R.; Pedreira, B.C.; Pezzopane, J R. Improvement of thermal comfort indices in agroforestry systems in the southern Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2020, 91, 102636. [CrossRef]

- Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Bosi, C.; Nicodemo, M.L.F.; Santos, P.M.; Gomes da Cruz, P.; Parmejiani, R.S. Microclimate and soil moisture in a silvopastoral system in southeastern Brazil. Bragantia, 2015, 74. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.F.; Person, J.A.; Cosgrove, G.P.; Barker, D.J.; Marotti, D.M.; Venning, K.J.; Rutter, S.M.; Hill, J.; Thompson, A.N. Impacts of spatial patterns in pasture on animal grazing behavior, Intake, and Performance. 2007, 47, 399–415. [CrossRef]

- Launchbaugh, K.L. Grazing animal behavior, Forages, 2020, pp. 827–838. [CrossRef]

- Paciullo, D.S.C.; Fernandes, P.B.; Carvalho, C.A.B.; Morenz, M.J.F.; Lima, M.A.; Maurício, R.M.; Gomide, C.A.M. Pasture and animal production in silvopastoral and open pasture systems managed with crossbred dairy heifers. Livestock Science, 2021, 245, 104426. [CrossRef]

- Waring, B.G.; Adams, R.; Branco, S.; Powers, J.S. Scale-dependent variation in nitrogen cycling and soil fungal communities along gradients of forest composition and age in regenerating tropical dry forests. The New Phytologist. 2016, 209, 845–854. [CrossRef]

- Orzech, K.; Wanic, M., Załuski, D. The effects of soil compaction and different tillage systems on the bulk density and moisture content of soil and the yields of winter oilseed rape and cereals. Agriculture, 2021, 11, 666. [CrossRef]

- Horn, R. Time dependence of soil mechanical properties and pore functions for arable soils. Soil Science Society of America journal. 2004, 68, 1131–1137. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.M.; Suzuki, L.E.A.S.; Reinert, D.J.; Horn, R.; Håkansson, I. Reference bulk density and critical degree-of-compactness for no-till crop production in subtropical highly weathered soils. Soil and Tillage Research, 2009, 102, 242–254. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, M.; Monaghan, R. Impacts of grazing on ground cover, soil physical properties and soil loss via surface erosion: A novel geospatial modelling approach. Journal of Environmental Management, 2021, 287, 112206. [CrossRef]

- Löbmann, M.T.; Tonin, T.; Stegemann, J.; Zerbe, S.; Geitner, C.; Mayr, A.; Wellstein. C. Towards a better understanding of shallow erosion resistance of subalpine grasslands. Journal of Environmental Management. 2020, 276, 111267. [CrossRef]

- Pilon, C.; Moore, P.A.; Pote, D.H.; Pennington, J.H.; Martin, J.W.; Brauer, D.K.; Raper, R.L.; Dabney, S.M.; Lee, J. Long-term effects of grazing management and buffer strips on soil erosion from pastures. J. Environ Qual. 2017, 46, 364–372. [CrossRef]

- Antoneli, V.; Rebinski, E.A.; Bednarz, J.A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Keesstra, S.D.; Cerdà, A.; Pulido Fernández, M. Soil erosion induced by the introduction of new pasture species in a faxinal farm of Southern Brazil. Geosciences. 2018, 8, 166. [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, G.S.; Brazier, R.E.; Haygarth, P.M. The impacts of grazing animals on the quality of soils, vegetation, and surface waters in intensively managed grasslands. Advances in Agronomy. 2007, 94, 237–280. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).