Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

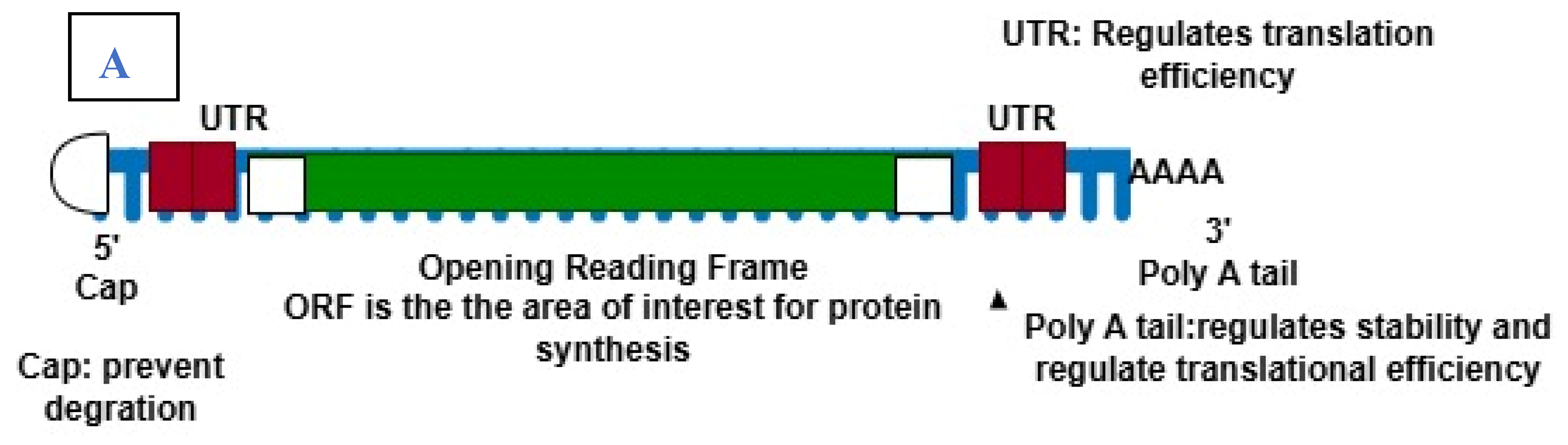

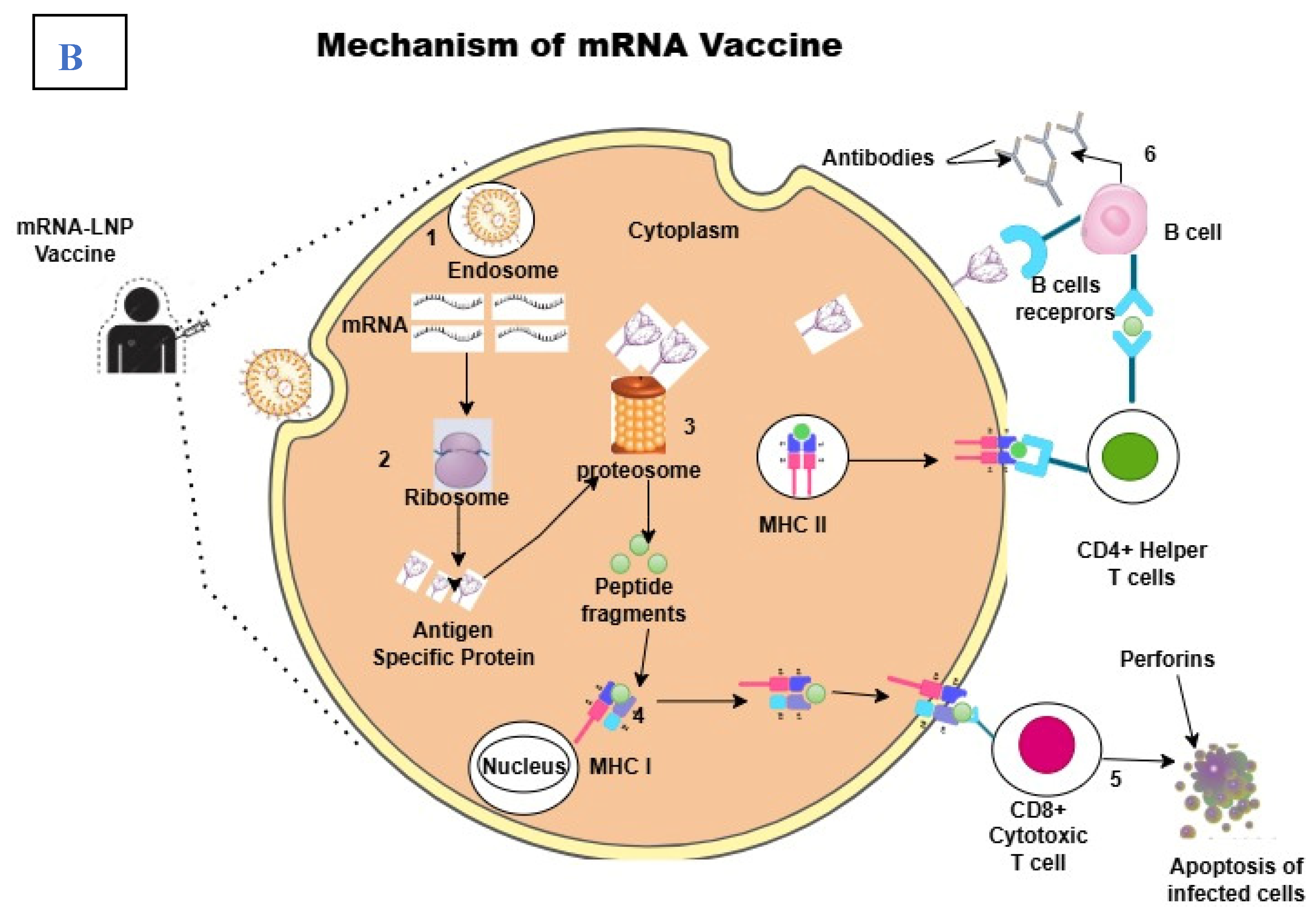

2.1. The Structure and Mechanism of Action of mRNA Vaccines

2.3. Key Advantages over Traditional Vaccine Platforms

3. Applications Beyond COVID-19

3.1. Infectious Diseases

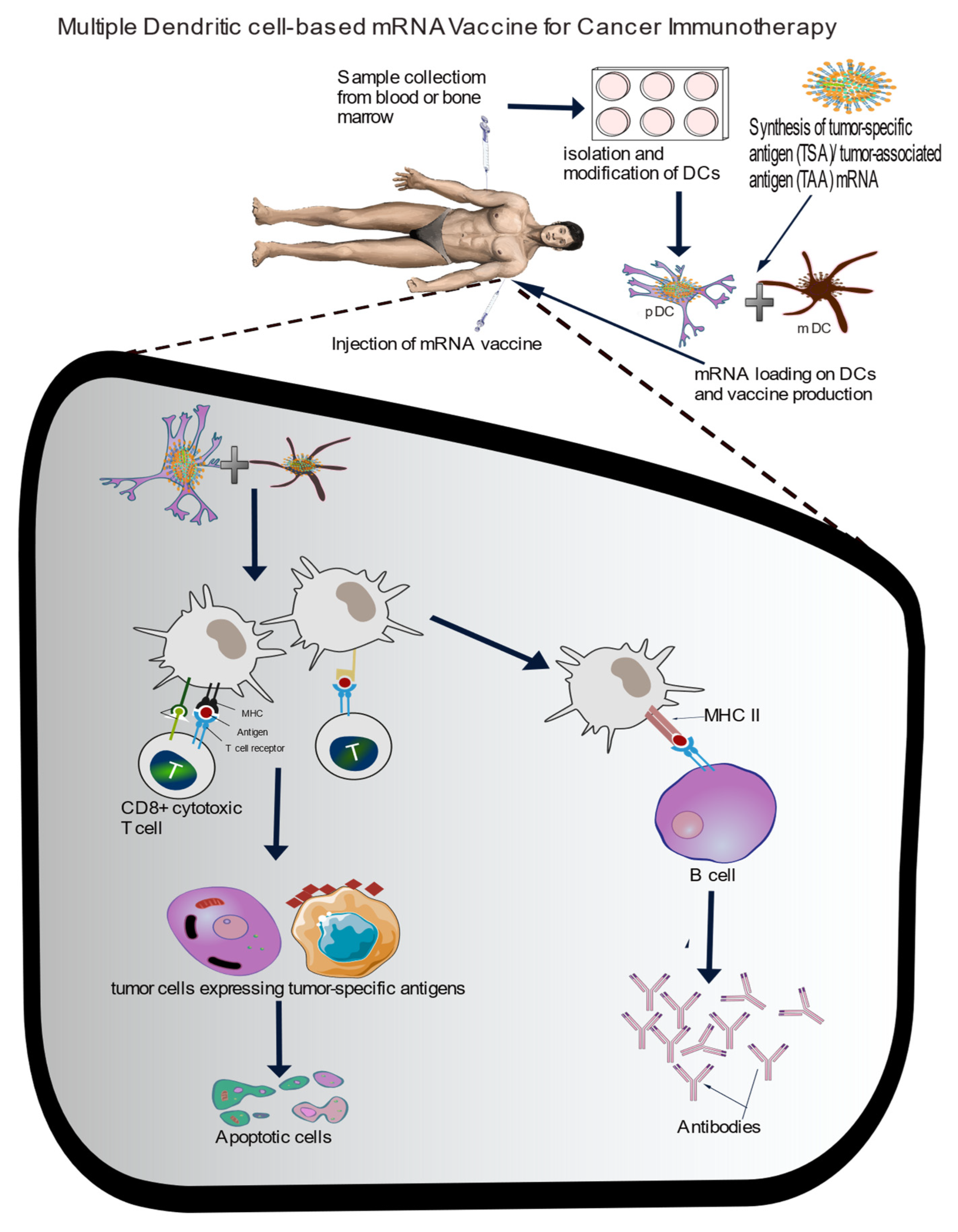

3.2. Cancer Immunology

3.3. Personalised Medicine

- -

- Potential in creating individualised vaccines for patients based on genetic profiles

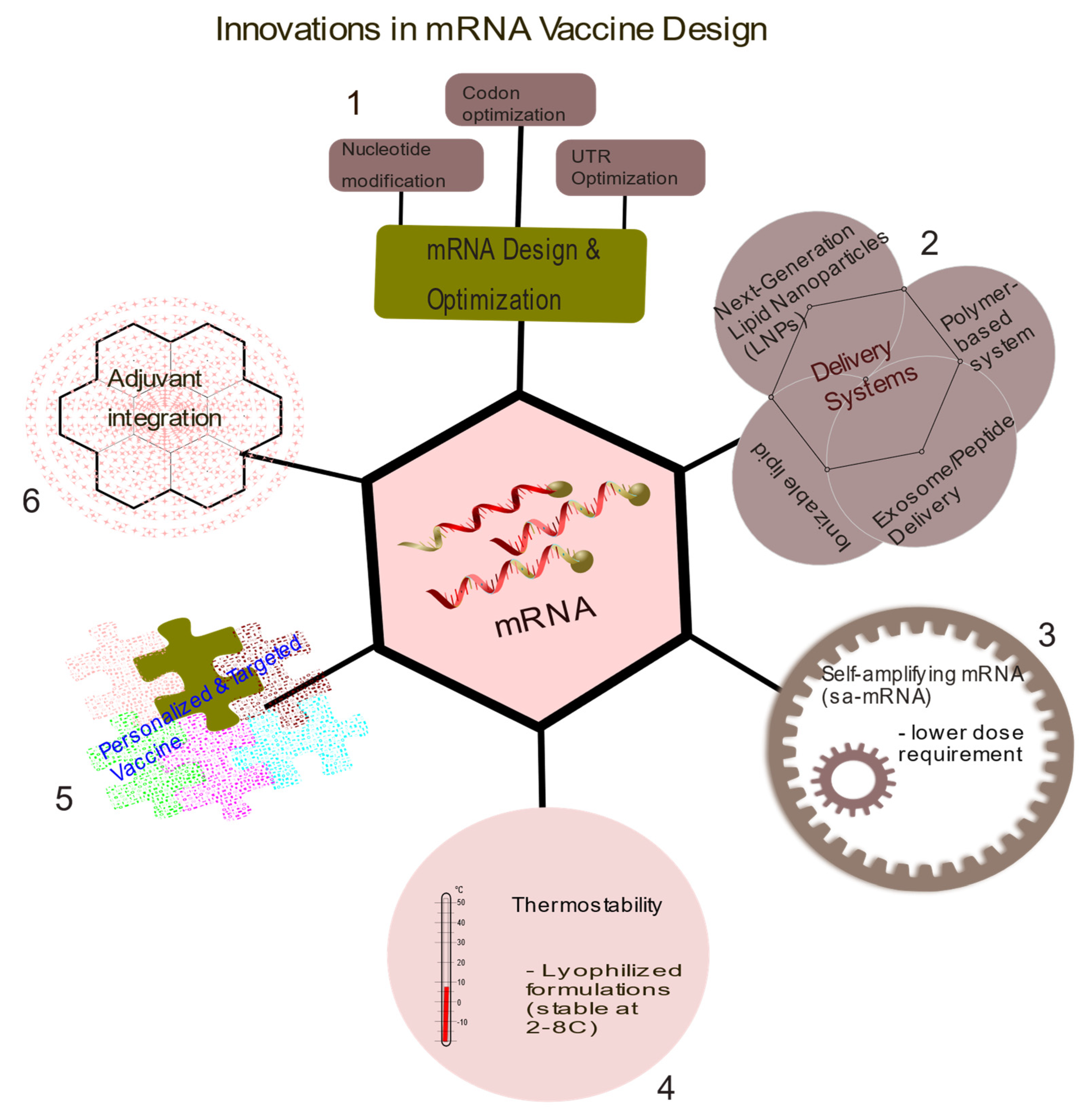

4. Innovations in mRNA Vaccine Designs

4.1. Advances in Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Delivery Systems

4.2. Improvement in Delivery Systems

4.3. Strategies for Enhancing Stability and Immunogenicity

4.4. Multivalent Vaccine Designs for Multiple Pathogens or Cancer Antigens

5. Current Challenges

5.1. Manufacturing and Scale-Up

- -

- Challenges in production and supply chain scalability.

- -

- Addressing regional manufacturing gaps.

5.2. Cost and Accessibility

- -

- High costs of mRNA technology compared to traditional vaccines.

- -

- Strategies for reducing costs and ensuring global equity.

5.3. Safety Concerns and Public Acceptance

- -

- Addressing adverse effects (e.g., myocarditis).

- -

- Public skepticism in the wake of misinformation.

6. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

- -

- Regulatory landscape for mRNA vaccines beyond COVID.

- -

- Ethical concerns related to personalized mRNA vaccines.

7.0. Future Direction

8.0. Conclusion

References

- Hsu FJ, Benike C, Fagnoni F, Liles TM, Czerwinski D, Taidi B, et al. Vaccination of patients with B–cell lymphoma using autologous antigen–pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med 1996;2:52–8. [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, Dong Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater 2021;6:1078–94. [CrossRef]

- Igyártó BZ, Qin Z. The mRNA-LNP vaccines – the good, the bad and the ugly? Front Immunol 2024;15:1336906. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Z, Rehman K, Mahmood A, Shabbir M, Liang Y, Duan L, et al. Exosome for mRNA delivery: strategies and therapeutic applications. J Nanobiotechnology 2024;22:395. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Zhang H, Butowska K, Swingle KL, Alameh M-G, Weissman D, et al. An ionizable lipid toolbox for RNA delivery. Nat Commun 2021;12:7233. [CrossRef]

- Hannani D, Leplus E, Laurin D, Caulier B, Aspord C, Madelon N, et al. A New Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccine in Combination with Anti-PD-1 Expands the Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cells of Lung Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:1897. [CrossRef]

- Charles J, Chaperot L, Hannani D, Bruder Costa J, Templier I, Trabelsi S, et al. An innovative plasmacytoid dendritic cell line-based cancer vaccine primes and expands antitumor T-cells in melanoma patients in a first-in-human trial. OncoImmunology 2020;9:1738812. [CrossRef]

- Lenogue K, Walencik A, Laulagnier K, Molens J-P, Benlalam H, Dreno B, et al. Engineering a Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccine to Prime and Expand Multispecific Viral and Tumor Antigen-Specific T-Cells. Vaccines 2021;9:141. [CrossRef]

- Perez CR, De Palma M. Engineering dendritic cell vaccines to improve cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2019;10:5408. [CrossRef]

- Schlake T, Thess A, Fotin-Mleczek M, Kallen K-J. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol 2012;9:1319–30. [CrossRef]

- Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Weissman D. Recent advances in mRNA vaccine technology. Curr Opin Immunol 2020;65:14–20. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary N, Weissman D, Whitehead KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:817–38. [CrossRef]

- Jin L, Zhou Y, Zhang S, Chen S-J. mRNA vaccine sequence and structure design and optimization: Advances and challenges. J Biol Chem 2025;301:108015. [CrossRef]

- Iavarone C, O’hagan DT, Yu D, Delahaye NF, Ulmer JB. Mechanism of action of mRNA-based vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017;16:871–81. [CrossRef]

- Bettini E, Locci M. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines: Immunological Mechanism and Beyond. Vaccines 2021;9:147. [CrossRef]

- Cagigi A, Loré K. Immune Responses Induced by mRNA Vaccination in Mice, Monkeys and Humans. Vaccines 2021;9:61. [CrossRef]

- Gergen J, Petsch B. mRNA-Based Vaccines and Mode of Action. In: Yu D, Petsch B, editors. MRNA Vaccines, vol. 440, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020, p. 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran S, Satapathy SR, Dutta T. Delivery Strategies for mRNA Vaccines. Pharm Med 2022;36:11–20. [CrossRef]

- Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, Weissman D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018;17:261–79. [CrossRef]

- Rosa SS, Prazeres DMF, Azevedo AM, Marques MPC. mRNA vaccines manufacturing: Challenges and bottlenecks. Vaccine 2021;39:2190–200. [CrossRef]

- Sahin U, Karikó K, Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics — developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:759–80. [CrossRef]

- Swetha K, Kotla NG, Tunki L, Jayaraj A, Bhargava SK, Hu H, et al. Recent Advances in the Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines 2023;11:658. [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker L, Witzigmann D, Kulkarni JA, Verbeke R, Kersten G, Jiskoot W, et al. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J Pharm 2021;601:120586. [CrossRef]

- Parhi R, Suresh P. Preparation and Characterization of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles-A Review. Curr Drug Discov Technol 2012;9:2–16. [CrossRef]

- Viegas C, Patrício AB, Prata JM, Nadhman A, Chintamaneni PK, Fonte P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Comparative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023;15:1593. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Gong L, Wang P, Zhao X, Zhao F, Zhang Z, et al. Recent Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles for Delivery of mRNA. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:2682. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Ding Y, Chong K, Cui M, Cao Z, Tang C, et al. Recent Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Safety Concerns for mRNA Delivery. Vaccines 2024;12:1148. [CrossRef]

- Naseri N, Valizadeh H, Zakeri-Milani P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Structure, Preparation and Application. Adv Pharm Bull 2015;5:305–13. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Wang X, Liu Y, Yang G, Falconer RJ, Zhao C-X. Lipid Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Adv NanoBiomed Res 2022;2:2100109. [CrossRef]

- Akbari J, Saeedi M, Ahmadi F, Hashemi SMH, Babaei A, Yaddollahi S, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: a review of the methods of manufacture and routes of administration. Pharm Dev Technol 2022;27:525–44. [CrossRef]

- Yoon G, Park JW, Yoon I-S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs): recent advances in drug delivery. J Pharm Investig 2013;43:353–62. [CrossRef]

- Klepac P, Funk S, Hollingsworth TD, Metcalf CJE, Hampson K. Six challenges in the eradication of infectious diseases. Epidemics 2015;10:97–101. [CrossRef]

- Parhiz H, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Weissman D. mRNA-based therapeutics: looking beyond COVID-19 vaccines. The Lancet 2024;403:1192–204. [CrossRef]

- Keddy KH, Gobena T. The continuing challenge of infectious diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:800–1. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues CMC, Plotkin SA. Impact of Vaccines; Health, Economic and Social Perspectives. Front Microbiol 2020;11:1526. [CrossRef]

- Khormi AHI, Qohal RMM, Masrai AYA, Hakami KHH, Ogdy JA, Almarshad AA, et al. Emerging Trends in mRNA Vaccine Technology: Beyond Infectious Diseases. Egypt J Chem 2024;67:1567–74. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi T. Advances in vaccines: revolutionizing disease prevention. Sci Rep 2023;13:11748, s41598-023-38798-z. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary N, Weissman D, Whitehead KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:817–38. [CrossRef]

- Overmars I, Au-Yeung G, Nolan TM, Steer AC. mRNA vaccines: a transformative technology with applications beyond COVID -19. Med J Aust 2022;217:71–5. [CrossRef]

- Szabó GT, Mahiny AJ, Vlatkovic I. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: Platforms and current developments. Mol Ther 2022;30:1850–68. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Magües LG, Gergen J, Jasny E, Petsch B, Lopera-Madrid J, Medina-Magües ES, et al. mRNA Vaccine Protects against Zika Virus. Vaccines 2021;9:1464. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Wei L, Chen H, Niu X, Dou Y, Yang J, et al. Development of Colloidal Gold-Based Immunochromatographic Assay for Rapid Detection of Goose Parvovirus. Front Microbiol 2018;9:953. [CrossRef]

- Bollman B, Nunna N, Bahl K, Hsiao CJ, Bennett H, Butler S, et al. An optimized messenger RNA vaccine candidate protects non-human primates from Zika virus infection. Npj Vaccines 2023;8:58. [CrossRef]

- Berkley SF, Koff WC. Scientific and policy challenges to development of an AIDS vaccine. The Lancet 2007;370:94–101. [CrossRef]

- Morris L. mRNA vaccines offer hope for HIV. Nat Med 2021;27:2082–4. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Y, Tian M, Gao Y. Development of an anti-HIV vaccine eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies. AIDS Res Ther 2017;14:50. [CrossRef]

- Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature 2008;455:613–9. [CrossRef]

- Boomgarden AC, Upadhyay C. Progress and Challenges in HIV-1 Vaccine Research: A Comprehensive Overview. Vaccines 2025;13:148. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Herschhorn A. mRNA-based HIV-1 vaccines. Clin Microbiol Rev 2024;37:e00041-24. [CrossRef]

- Khalid K, Padda J, Khedr A, Ismail D, Zubair U, Al-Ewaidat OA, et al. HIV and Messenger RNA Vaccine. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Moderna. Moderna Announces First Participant Dosed in Phase 1 Study of its HIV Trimer mRNA Vaccine. n.d.

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. The Lancet 2018;391:1285–300. [CrossRef]

- Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. The Lancet 2017;390:697–708. [CrossRef]

- Gouma S, Anderson EM, Hensley SE. Challenges of Making Effective Influenza Vaccines. Annu Rev Virol 2020;7:495–512. [CrossRef]

- Becker T, Elbahesh H, Reperant LA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME. Influenza Vaccines: Successes and Continuing Challenges. J Infect Dis 2021;224:S405–19. [CrossRef]

- Fleeton MN, Chen M, Berglund P, Rhodes G, Parker SE, Murphy M, et al. Self-Replicative RNA Vaccines Elicit Protection against Influenza A Virus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and a Tickborne Encephalitis Virus. J Infect Dis 2001;183:1395–8. [CrossRef]

- Mazunina EP, Gushchin VA, Kleymenov DA, Siniavin AE, Burtseva EI, Shmarov MM, et al. Trivalent mRNA vaccine-candidate against seasonal flu with cross-specific humoral immune response. Front Immunol 2024;15:1381508. [CrossRef]

- Leonard A, Weiss MJ. Hematopoietic stem cell collection for sickle cell disease gene therapy. Curr Opin Hematol 2024;31:104–14. [CrossRef]

- Hatta M, Hatta Y, Choi A, Hossain J, Feng C, Keller MW, et al. An influenza mRNA vaccine protects ferrets from lethal infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus. Sci Transl Med 2024;16:eads1273. [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko AV, Khan MM, Zhen X, Tang Y, Tao W. Clinical advances of mRNA vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Med 2025;6:100562. [CrossRef]

- Zhang G, Tang T, Chen Y, Huang X, Liang T. mRNA vaccines in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8:365. [CrossRef]

- Bidram M, Zhao Y, Shebardina NG, Baldin AV, Bazhin AV, Ganjalikhany MR, et al. mRNA-Based Cancer Vaccines: A Therapeutic Strategy for the Treatment of Melanoma Patients. Vaccines 2021;9:1060. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Pei J, Xu S, Liu J, Yu J. Recent advances in mRNA cancer vaccines: meeting challenges and embracing opportunities. Front Immunol 2023;14:1246682. [CrossRef]

- Sahin U, Oehm P, Derhovanessian E, Jabulowsky RA, Vormehr M, Gold M, et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature 2020;585:107–12. [CrossRef]

- Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC. A Clinical Study of V940 Plus Pembrolizumab in People With High-Risk Melanoma (V940-001). n.d.

- Seraphin TP, Joko-Fru WY, Kamaté B, Chokunonga E, Wabinga H, Somdyala NIM, et al. Rising Prostate Cancer Incidence in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Trend Analysis of Data from the African Cancer Registry Network. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021;30:158–65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang G, Tang T, Chen Y, Huang X, Liang T. mRNA vaccines in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8:365. [CrossRef]

- Kübler H, Scheel B, Gnad-Vogt U, Miller K, Schultze-Seemann W, Vom Dorp F, et al. Self-adjuvanted mRNA vaccination in advanced prostate cancer patients: a first-in-man phase I/IIa study. J Immunother Cancer 2015;3:26. [CrossRef]

- Varaprasad GL, Gupta VK, Prasad K, Kim E, Tej MB, Mohanty P, et al. Recent advances and future perspectives in the therapeutics of prostate cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol 2023;12:80. [CrossRef]

- Lin G, Elkashif A, Saha C, Coulter JA, Dunne NJ, McCarthy HO. Key considerations for a prostate cancer mRNA vaccine. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2025;208:104643. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Ramiro F, Peiró-Pastor R, Aguado B. Human genomics projects and precision medicine. Gene Ther 2017;24:551–61. [CrossRef]

- Goetz LH, Schork NJ. Personalized medicine: motivation, challenges, and progress. Fertil Steril 2018;109:952–63. [CrossRef]

- Lin F, Lin EZ, Anekoji M, Ichim TE, Hu J, Marincola FM, et al. Advancing personalized medicine in brain cancer: exploring the role of mRNA vaccines. J Transl Med 2023;21:830. [CrossRef]

- Fu Q, Zhao X, Hu J, Jiao Y, Yan Y, Pan X, et al. mRNA vaccines in the context of cancer treatment: from concept to application. J Transl Med 2025;23:12. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yan Q, Zeng Z, Fan C, Xiong W. Advances and prospects of mRNA vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Rev Cancer 2024;1879:189068. [CrossRef]

- Hu C, Bai Y, Liu J, Wang Y, He Q, Zhang X, et al. Research progress on the quality control of mRNA vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2024;23:570–83. [CrossRef]

- Weber JS, Carlino MS, Khattak A, Meniawy T, Ansstas G, Taylor MH, et al. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): a randomised, phase 2b study. The Lancet 2024;403:632–44. [CrossRef]

- Weichenthal M, Svane IM, Mangana J, Leiter U, Meier F, Ruhlmann C, et al. Real-World efficiency of pembrolizumab in metastatic melanoma patients following adjuvant anti-PD1 treatment. EJC Skin Cancer 2024;2:100271. [CrossRef]

- Jim Stallard. In Early-Phase Pancreatic Cancer Clinical Trial, Investigational mRNA Vaccine Induces Sustained Immune Activity in Small Patient Group 2025. https://www.mskcc.org/news/can-mrna-vaccines-fight-pancreatic-cancer-msk-clinical-researchers-are-trying-find-out.

- Chitwood, H. & Myers, A. Use of Circulating Tumor DNA to Monitor Minimal Residual Disease Among Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2023. [CrossRef]

- Oosting LT, Franke K, Martin MV, Kloosterman WP, Jamieson JA, Glenn LA, et al. Development of a Personalized Tumor Neoantigen Based Vaccine Formulation (FRAME-001) for Use in a Phase II Trial for the Treatment of Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:1515. [CrossRef]

- Bitounis D, Jacquinet E, Rogers MA, Amiji MM. Strategies to reduce the risks of mRNA drug and vaccine toxicity. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2024;23:281–300. [CrossRef]

- Kremsner PG, Ahuad Guerrero RA, Arana-Arri E, Aroca Martinez GJ, Bonten M, Chandler R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the CVnCoV SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine candidate in ten countries in Europe and Latin America (HERALD): a randomised, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22:329–40. [CrossRef]

- Sheykhhasan M, Ahmadieh-Yazdi A, Heidari R, Chamanara M, Akbari M, Poondla N, et al. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: The power of dendritic cell-based vaccines in immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother 2025;184:117858. [CrossRef]

- Kranz LM, Diken M, Haas H, Kreiter S, Loquai C, Reuter KC, et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 2016;534:396–401. [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Jones GBE, Elbashir SM, Wu K, Lee D, Renzi I, Ying B, et al. Development of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines encoding spike N-terminal and receptor binding domains 2022. [CrossRef]

- Arevalo CP, Bolton MJ, Le Sage V, Ye N, Furey C, Muramatsu H, et al. A multivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against all known influenza virus subtypes. Science 2022;378:899–904. [CrossRef]

- Sahin U, Muik A, Vogler I, Derhovanessian E, Kranz LM, Vormehr M, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature 2021;595:572–7. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Yang K, Li R, Zhang L. mRNA Vaccine Era—Mechanisms, Drug Platform and Clinical Prospection. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6582. [CrossRef]

- Wei H, Rong Z, Liu L, Sang Y, Yang J, Wang S. Streamlined and on-demand preparation of mRNA products on a universal integrated platform. Microsyst Nanoeng 2023;9:97. [CrossRef]

- Doua J, Ndembi N, Auerbach J, Kaseya J, Zumla A. Advancing local manufacturing capacities for vaccines within Africa - Opportunities, priorities and challenges. Vaccine 2025;50:126829. [CrossRef]

- Davidopoulou C, Kouvelas D, Ouranidis A. COMPARING vaccine manufacturing technologies recombinant DNA vs in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA. Sci Rep 2024;14:21742. [CrossRef]

- Seth Berkley. Ramping up Africa’s vaccine manufacturing capability is good for everyone. Here’s why 2022.

- Van De Pas R, Widdowson M-A, Ravinetto R, N Srinivas P, Ochoa TJ, Fofana TO, et al. COVID-19 vaccine equity: a health systems and policy perspective. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022;21:25–36. [CrossRef]

- Faksova K, Walsh D, Jiang Y, Griffin J, Phillips A, Gentile A, et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2024;42:2200–11. [CrossRef]

- Mahase E. FDA pauses all infant RSV vaccine trials after rise in severe illnesses. BMJ 2024:q2852. [CrossRef]

- Meghana GVR, Chavali DP. Examining the Dynamics of COVID-19 Misinformation: Social Media Trends, Vaccine Discourse, and Public Sentiment. Cureus 2023;15:e48239. [CrossRef]

- Bouderhem R. Challenges Faced by States and the WHO in Efficiently Regulating the Use of mRNA Vaccines. IECV 2023, MDPI; 2023, p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Dixit S, Srinivasan K, M D, Vincent PMDR. Personalized cancer vaccine design using AI-powered technologies. Front Immunol 2024;15:1357217. [CrossRef]

- Clemente B, Denis M, Silveira CP, Schiavetti F, Brazzoli M, Stranges D. Straight to the point: targeted mRNA-delivery to immune cells for improved vaccine design. Front Immunol 2023;14:1294929. [CrossRef]

| Company | Candidate | Product Type | Disease | Status | CT Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanofi | VAV00027 | mRNA/LNP | RSV/hMPV | Phase I | NCT06237296 |

| VBS00001 | mRNA vaccine | Pandemic flu H5 | Phase I/II | NCT06727058 | |

| MRT5421, MRT5424, and MRT5429 | mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I/II | NCT06361875 | |

| mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I/II | NCT06744205 | ||

| mRNA-NA | mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I | NCT05426174 | |

| mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I | NCT05829356 | ||

| mRNA vaccine | Acne | Phase I/II | NCT06316297 | ||

| Rabipur® CV7202 | mRNA vaccine | Rabies | Phase I | NCT03713086 | |

| RNActive® CV7201 | mRNA vaccine | Rabies | Phase I | NCT02241135 | |

| MRT5413 | mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I/II | NCT05650554 | |

| mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I | NCT06118151 | ||

| Moderna TX, Inc. | mRNA-1189 | mRNA vaccine | Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) | Phase I/II | NCT05164094 |

| mRNA-1644 mRNA-1574 |

HIV | Phase I/II | NCT03547245 | ||

| mRNA-1215 | Nipah Virus (NiV) | Phase I | NCT05398796 | ||

| mRNA-1769 | Mpox | Phase I/II | NCT05995275 | ||

| mRNA-1403 | Novovirus/(Acute Gastroenteritis) | NCT06592794 | |||

| mRNA-1647 | Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Phase III | NCT05085366 | ||

| mRNA-1325, mRNA-1893 |

mRNA vaccine | Zika virus | Phase I Phase II |

NCT03014089 NCT04064905 |

|

| mRNA-1010 | Seasonal Flu | Phase III | NCT06602024 | ||

| mRNA-1011.1, mRNA-1011.2, mRNA-1012.1 | Next-Gen mRNA vaccines | Influenza Virua | Phase I/II | NCT05827068 | |

| mRNA-1345 | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | Phase III | NCT06067230 | ||

| mRNA-1365 | Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) | Phase I | NCT05743881 | ||

| mRNA-1608 | Herpes Simplex Virus | Phase I/II | NCT06033261 | ||

| mRNA-1468 | Herpes Zoster (HZ) | Phase I/II | NCT05701800 | ||

| VAL-339851 | Seasonal influenza | Phase I | NCT03345043 | ||

| mRNA-1944 | Chikungunya Virus | Phase I | NCT03829384 | ||

| CanSino Biologics | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase I/II | NCT05373485 NCT05373472 |

|

| National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) | HVTN 302 | BG505 MD39.3 mRNA/BG505 MD39.3 gp151 mRNA/BG505 MD39.3 gp151 CD4KO mRNA | HIV | Phase I | NCT05217641 |

| mRNA-1273 | mRNA-LNP | COVID-19 | Phase I | NCT04283461 | |

| mRNA-1215 | mRNA vaccine | Nipah Virus (NiV) | Phase I | NCT05398796 | |

| Massachusetts General Hospital | mRNA-transfected autologous dendritic cells | HIV-1 | Phase I/II | NCT00833781 | |

| AstraZeneca | AZD9838/ AZD6563 | mRNA-VLP | SARS-CoV-2 | Phase I | NCT06147063 |

| CSPC ZhongQi Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. | SYS6006 | mRNA vaccine | SARS-CoV-2 | Phase II | NCT05439824 |

| Immorna Biotherapeutics, Inc. | JCXH-221 | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase II | NCT05743335 |

| JCXH-108 | mRNA vaccine | RSV | Phase I | NCT06564194 | |

| CNBG-Virogin Biotech (Shanghai) Ltd. | ZSVG-02-O | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase II | NCT06113731 |

| Vaxart | VXA-CoV2-3.1 | Oral SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Tablet | COVID-19 | Phase II | NCT06672055 |

| Shenzhen Shenxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd | IN001 | mRNA vaccine | Herpes Zoster | Phase I | NCT06375512 |

| *** Lemonex | LEM-mR203 | mRNA-DegradaBALL vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase I | NCT06032000 |

| Barinthus Biotherapeutics | ChAdOx1-HBV | mRNA HBV vaccine | Chronic HBV infection | Phase I | NCT04297917 |

| RinuaGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. | RG002 | mRNA vaccine | HPV16/18 associated Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 2 or 3(CIN2/3). | Phase I/II | NCT06273553 |

| Speransa Therapeutics | PRIME-2-CoV_Beta | COVID-19 | Phase I | NCT05367843 | |

| Albert B. Sabin Vaccine Institute | Sinovac | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase IV | NCT05343871 |

| Sinocelltech Ltd. | SCTV01E-2 | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase II | NCT05933512 |

| SK Bioscience Co., Ltd. | GBP560-A GBP560-B |

mRNA vaccine | SK Japanese Encephalitis virus disease | Phase I/II | NCT06680128 |

| Gritstone bio, Inc. Seqirus Stemirna Therapeutics |

GRT-R912, GRT-R914, and GRT-R918 | samRNA Vaccine | COVID-19/HIV | Phase I | NCT05435027 |

| V202_01 | Sa-mRNA vaccine | Influenza | Phase I | NCT06028347 | |

| SWC002 | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase I/II | NCT05144139 | |

| SW-BIC-213 | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase III | NCT05580159 | |

| SWIM816 | mRNA vaccine | COVID-19 | Phase II/III | NCT05911087 |

| Company | Candidate | Product Type | Cancer Type | Status | CT Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioNTech | BNT111 TYR, vaccine, CTAG1B | mRNA vaccine | Malignant melanoma | Phase II | NCT04526899 |

| BNT113 vaccine | mRNA vaccine | Head and neck cancer | Phase II | NCT04534205 | |

| BioNTech/Regeneron Pharmaceuticals | BNT116 vaccine, TAA | mRNA vaccine | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Phase II | NCT05557591 |

| BioNTech/Roche | BNT112 (autogene cevumeran) vaccine, neoantigen | mRNA vaccine | Malignant melanoma | Phase II | NCT03815058 |

| Colorectal cancer | Phase II | NCT04486378 | |||

| Other metastatic tumors | Phase II | NCT03289962 | |||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | Phase II | NCT05968326 | |||

| Muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIUC) | Phase II | NCT06534983 | |||

| **** | Metastatic castration resistance prostate cancer (mCRPC) | Phase I/II | NCT04382898 | ||

| Moderna TX, Inc. | mRNA-4359 + pembrolizumab | Advanced solid tumors | Phase I/II | NCT05533697 | |

| mRNA-4106 + Nivolumab/Relatlimab | Solid tumors | Phase I | NCT06880549 | ||

| mRNA-2752 | Refractory solid tumors/lymphoma | Phase I | NCT03739931 | ||

| mRNA-2736 | Relapsed/refractory multiple myeolema | Phase I | NCT05918250 | ||

| Moderna/ Merck & Co | mRNA-4157 vaccine/ neoantigen | mRNA vaccine | Bladder cancer | Phase I/II | NCT06305767 |

| non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Phase III | NCT06077760 | |||

| Renal cell carcinoma | Phase II | NCT06307431 | |||

| Malignant melanoma | Phase III | NCT05933577 | |||

| Others | Phase II/III | NCT06295809 | |||

| Stemirna | mRNA vaccine | Advanced malignant solid tumors | Preclinical | NCT05949775 | |

| Personalized tumor vaccine for esophageal and non-small cells lung cancers | Preclinical | NCT03908671 | |||

| CureVac | CV09050101 | mRNA vaccine (CVGBM) | Glioblastoma (GBM) | Phase I | NCT05938387 |

| Fudan University | PANC-IIT-RGL-mRNA vaccine | mRNA vaccine | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Preclinical/phase I | NCT06156267 |

| HRXG-K-1939 | mRNA vaccine + adebrelimab | Advanced solid tumors | Phase I | NCT05942378 | |

| Guangzhou Medical University | ZZVACCINE-mRNA-020 | Neoantigen mRNA vaccine | Advanced Solid Tumors | Phase I | NCT06195384 |

| National cancer institute *** | NCI-4650 | mRNA-based personalized vaccine | Metastatic epithelial cancer | Phase I/II | NCT03480152 |

| Ruijin Hospital | Xp-004 | mRNA tumor vaccine | Recurrent pancreatic cancer | Phase I | NCT06496373 |

| WGc-043 | EBV mRNA vaccine | Refractory Lymphoma | Phase I | NCT06788600 | |

| Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital | Neoantigen mRNA vaccine | non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). | Phase I | NCT06735508 | |

| University Hospital Tuebingen | RNA-Mel-03 | mRNA vaccine coding for Melan-A, Mage-A1, Mage-A3, Survivin, GP100 and Tyrosinase | Malignant melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT00204516 |

| Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital | Personalized mRNA vaccine | Posto perative hepatocellular carcinoma | Preclinical | NCT05761717 | |

| Steinar Aamdal*** | DC-004 | mRNA vaccine with dendritic cells | Metastatic malignant melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT00961844 |

| Radboud University Medical left | TLR-DC and Trimix DC loaded with mRNA encoding melanoma-associated tumor antigens (gp100 and tyrosinase) | Metastatic melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT01530698 | |

| *** Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer left | Vaccination With CT7, MAGE-A3, and WT1 mRNA-electroporated Autologous Langerhans-type Dendritic Cells as Consolidation | Multiple myeloma | Phase I | NCT01995708 | |

| Autologous Langerhans-type Dendritic Cells with mRNA encoding tumor antigen | Melanoma | Phase I | NCT01456104 | ||

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine | mRNA-0523-L001 | Individualized mRNA neoantigen vaccine | Advanced endocrine tumor | Phase I | NCT06141369 |

| John Sampson, Duke University | BTSC mRNA-loaded DCs | Personalized cancer vaccine | glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) | Phase I | NCT00890032 |

| Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital | iNeo-Vac-R01 | Personalized mRNA vaccine | Advanced Digestive System Neoplasms | Phase I | NCT06019702 |

| iNeo-Vac-R01 + standard adjuvant therapy | NCT06026774 | ||||

| Inge Marie Svane, Herlev Hospital | mRNA transfected dendritic cell | Metastatic prostate cancer | Phase II | NCT01446731 | |

| Steinar Aamdal, Oslo University Hospital *** | DC-004 ** | mRNA vaccine therapy with dendritic cells | Metastatic malignant melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT00961844 |

| DC-006 ** | Dendric cells with amplified ovarian cancer stem cell vaccine | Recurrent Platinum Sensitive Epithelial Ovarian cancer | Phase I/II | NCT01334047 | |

| DC-005 | Dendritic cells with cancer mRNA vaccine | Prostate cancer | Phase I/II | NCT01197625 | |

| DC-CAST-GMB | Dendritic cells with cancer mRNA vaccine | gliobalstoma | Phase I/II | NCT00846456 | |

| Nanjing Tianyinshan Hospital | RGL-270 | MRNA Vaccine + Adebrelimab | Non-small cells lung cancer | Phase I | NCT06685653 |

| Radboud University Medical left | TLR-DC and Trimix DC | Autologous dendritic cell vaccine | Melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT01530698 |

| mRNA vaccine | Melanoma stage III/IV | Phase I/II | NCT00243529 | ||

| MiHA-loaded PD-L-silenced DC vaccine | Hematological malignancies | Phase I/II | NCT02528682 | ||

| CEA-loaded dendritic cell vaccine | Colorectal cancer | Phase I/II | NCT00228189 | ||

| ***Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research | BI 1361849 | mRNA vaccine + durvalumab + tremelimumab | Metastatic non-small cells lung cancer | Phase I/II | NCT03164772 |

| YueJuan Cheng, Peking Union Medical College Hospital | KY- 1007 | Personalized mRNA neoantigen vaccine | Advanced solid tumors | Early phase I | NCT05359354 |

| Guangdong 999 Brain Hospital | PERCELLVAC3 | Personalized cellular vaccine | Glioblastoma | Phase I | NCT02808416 |

| PerCellVac2 | Personalized cellular vaccine | Glioblastoma | Phase I | NCT02808364 | |

| Jinling Hospital, China | SJ-Neo006 | Camrelizumab + personalized neoantigen vaccines | Pancreatic cancer | Early phase I | NCT06326736 |

| Wu Wenming, Peking Union Medical College Hospital | XH001 | Neoantigen cancer vaccine + Ipilimumab | Pancreatic cancer | Early phase I | NCT06353646 |

| University of Florida *** | RNA PRIME | pp65 RNA LP (DP1 & DP2) vaccines | Pediatric Recurrent Intracranial malignancies | Phase I/II | NCT05660408 |

| pp65 RNA-LP | mRNA vaccine | Recurrent glioblastoma | Phase I | NCT06389591 | |

| PNOC020 | RNA-loaded lipid particle (RNA-LP) vaccine | Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas (pHGG), and Adult Glioblastoma | Phase I/II | NCT04573140 | |

| pp65-shLAMP *** | pp65-shLAMP mRNA DCs with GM-CSF | Glioblastoma Multiforme | Phase II | NCT02465268 | |

| jianming xu, The Affiliated Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences | mRNA neoantigen tumor vaccine | Advanced gastric, esophageal, and liver cancers | Early phase I | NCT05192460 | |

| XH001 | Neoantigen tumor vaccine, XH001 + sintilimab | Advanced solid tumors | Preclinical | NCT05940181 | |

| RinuaGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. | RG002 | mRNA therapeutic vaccine | HPV16/18 associated Cervical Intraepithelial neoplasia | Phase I/II | NCT06273553 |

| Gary Archer Ph.D., Duke University | Dendric cell-based mRNA vaccine | Brain tumor | Phase I | NCT00639639 | |

| DC-based mRNA vaccine + Nivolumab | Brain tumors | Phase I | NCT02529072 | ||

| University Medical left Groningen | W_ova1 vaccine | Liposome formulated mRNA vaccine | Ovarian cancer | Phase I | NCT04163094 |

| Zwi Berneman, University Hospital, Antwerp | CCRG12-001 | DC vaccine | Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) | Phase II | NCT01686334 |

| Svein Dueland, Oslo University Hospital | mRNA vaccine | Malignant melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT01278940 | |

| mRNA vaccine | Androgen Resistant Metastatic Prostate cancer | Phase I/II | NCT01278914 | ||

| Inge Marie Svane, Herlev Hospital | DC vaccine | Breast cancer | Phase I | NCT00978913 | |

| Peking Union Medical College Hospital | ABOR2014(IPM511) | Neoantigen mRNA vaccine | Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma | Preclinical | NCT05981066 |

| Diakonos Oncology Cooperation | DOC1021 | Dendric cell-based mRNA vaccine loaded with tumor lysate | Adult Glioblastoma | Phase II | NCT06805305 |

| Peking University Hospital & Institute | JCXH-212 | Tumor neoantigen mRNA vaccine | Malignant solid tumors | Early phase I | NCT05579275 |

| *** Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC | mRNA 5679/V941 | mRNA vaccine | Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Colorectal or Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | Phase I | NCT03948763 |

| University Hospital, Antwerp | CCRG 05-001 | Dendritic-based mRNA vaccine | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Phase I | NCT00834002 |

| DC vaccine | Pediatric High Grade Gliomas, and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas | Phase I/II | NCT04911621 | ||

| The Affiliated Hospital Of Guizhou Medical University | InnoPCV | mRNA vaccine | Advanced solid tumors | Early phase I | NCT06497010 |

| Company/sponsor | Candidate | Product Type | Disease(s) | Status | Reference |

| Duke University | |||||

| BioNTech/Roche | BNT112 (autogene cevumeran) vaccine, neoantigen | mRNA vaccine | Malignant melanoma | Phase II | NCT03815058 |

| Colorectal cancer | Phase II | NCT04486378 | |||

| Other metastatic tumors | Phase II | NCT03289962 | |||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | Phase II | NCT05968326 | |||

| Muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIUC) | Phase II | NCT06534983 | |||

| Moderna/ Merck & Co | mRNA-4157 vaccine/ neoantigen | mRNA vaccine | Bladder cancer | Phase I/II | NCT06305767 |

| non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Phase III | NCT06077760 | |||

| Renal cell carcinoma | Phase II | NCT06307431 | |||

| Malignant melanoma | Phase III | NCT05933577 | |||

| Others | Phase II/III | NCT06295809 | |||

| mRNA-1195 | mRNA vaccine |

Multiple Sclerosis | Phase II | NCT06735248 | |

| mRNA-3927 | Propionic Acidemia | Phase I/II | NCT04159103 | ||

| mRNA-3745 | Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1a (GSD1a) | Phase I/II | NCT05095727 | ||

| mRNA-3705 | methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) | Phase I/II | NCT05295433 | ||

| mRNA-1083 | COVID-19 + Influenza | Phase III | NCT06694389 | ||

| mRNA-1975, mRNA-1982 | Lyme Disease | Phase I/II | NCT05975099 | ||

| mRNA-1653 | hMPV + Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 (PIV3) | Phase I | NCT04144348 | ||

| mRNA-1045 | Influenza + RSV | Phase I | NCT05585632 | ||

| mRNA-1230 | Influenza + RSV + SARS-CoV-2 | Phase I | NCT05585632 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).