1. Introduction

Industry 5.0 signifies a paradigm shift in manufacturing, characterized by a renewed emphasis on human-centricity, sustainability, and resilience, contrasting with the efficiency- and automation-driven objectives of Industry 4.0. [

1]. Smart manufacturing environments are now designed to optimize performance and productivity and ensure adaptability to unforeseen challenges, such as pandemics, wars, and natural disasters. [

2]. Humanoid robots (HRs) are becoming more recognized as a viable and strategic asset in this new industrial landscape. With their anthropomorphic design and advanced cognitive and motor skills, humanoid robots fit seamlessly into environments where they can work alongside people. They can navigate spaces, use tools, and interact intuitively and safely with people. This makes them valuable in achieving the goals of Industry 5.0 [

3,

4,

5,

6].

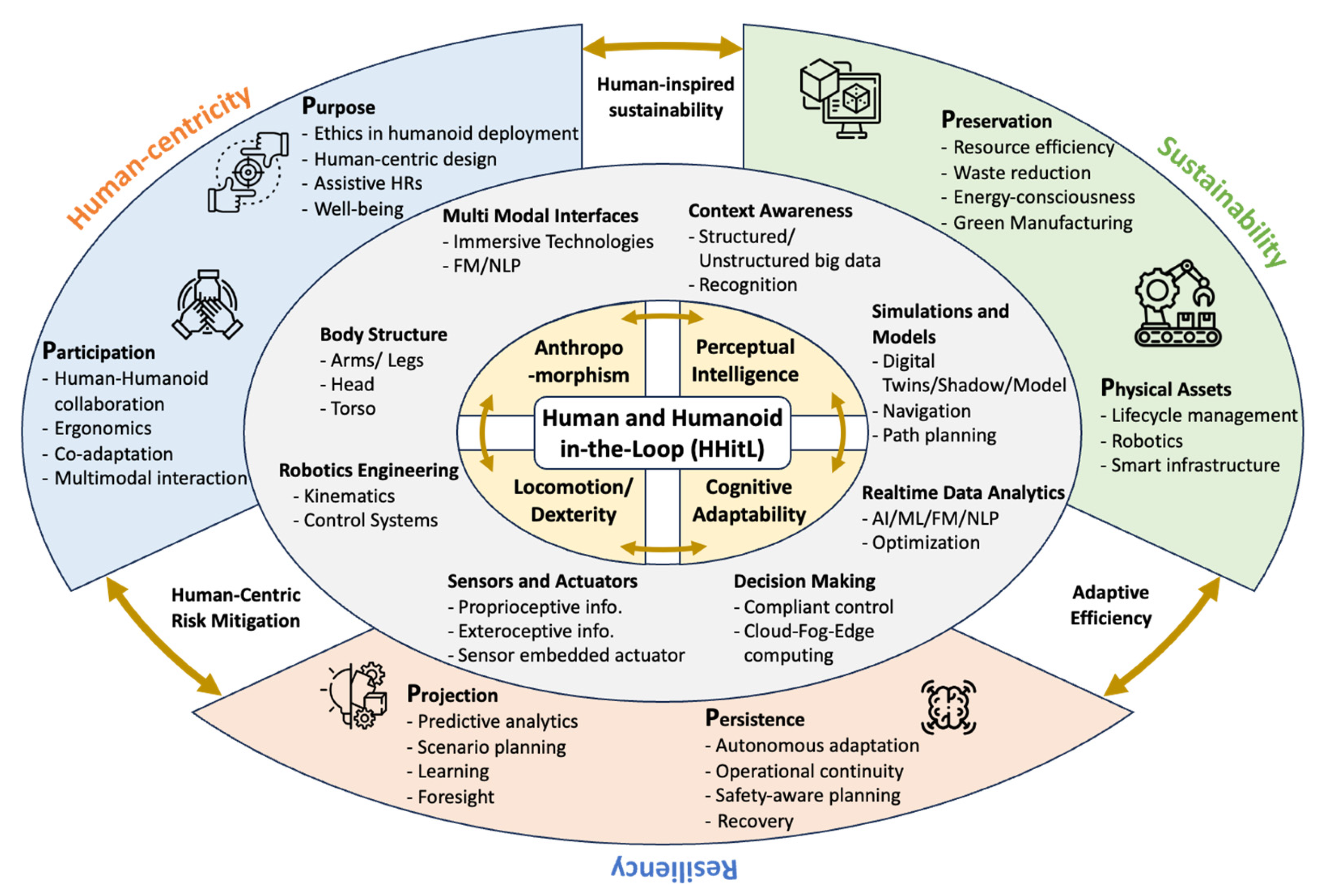

In the context of sustainability, resiliency, and human-centricity, which are the main aspects of Industry 5.0 [

7], the concept of “Human and Humanoid in-the-Loop (HHitL)” is introduced. It refers to integrating HRs not just as tools, but as autonomous, decision-making entities within collaborative manufacturing loops. HRs can replace or assist human operators in hazardous conditions, ensuring continuity without compromising safety. In addition, during supply chain disruptions, they can adaptively take over manual operations with minimal retraining. HRs can enhance human well-being while improving productivity in ergonomically risky or repetitive tasks.

Despite HRs’ huge potential in these roles, a significant research gap remains unexplored, especially under the umbrella of Industry 5.0. Accordingly, there is a demand to reidentify the industrial ecosystem through the lens of HRs. The primary goal of this paper is to conceptualize the HHitL ecosystem, outline its architecture, and explore the challenges and outlooks of its implementation in smart manufacturing aligned with Industry 5.0 principles.

2. The Proposed Ecosystem

With the emergence of Industry 5.0, three principles of human-centricity, resiliency, and sustainability have gained much importance. Simultaneously, manufacturing has expanded beyond traditional cyber-physical systems to include humanoid robots, i.e., physical AI [

8] agents capable of interacting in shared human environments with cognitive, physical, and social capabilities. These developments necessitate rethinking the architectural foundation to better reflect the demands of the modern industry. To address this issue, we have proposed the HHitL ecosystem from the Industry 5.0 perspective, as shown in

Figure 1. In the following, we will elaborate on different aspects of this ecosystem from a bottom-up perspective. We will begin by introducing the HHitL architecture in

Section 2.1. The core features and their enablers will be defined in

Section 2.2, and the six pillars (6P) of the proposed ecosystem will be elaborated and mapped to the three principles of Industry 5.0.

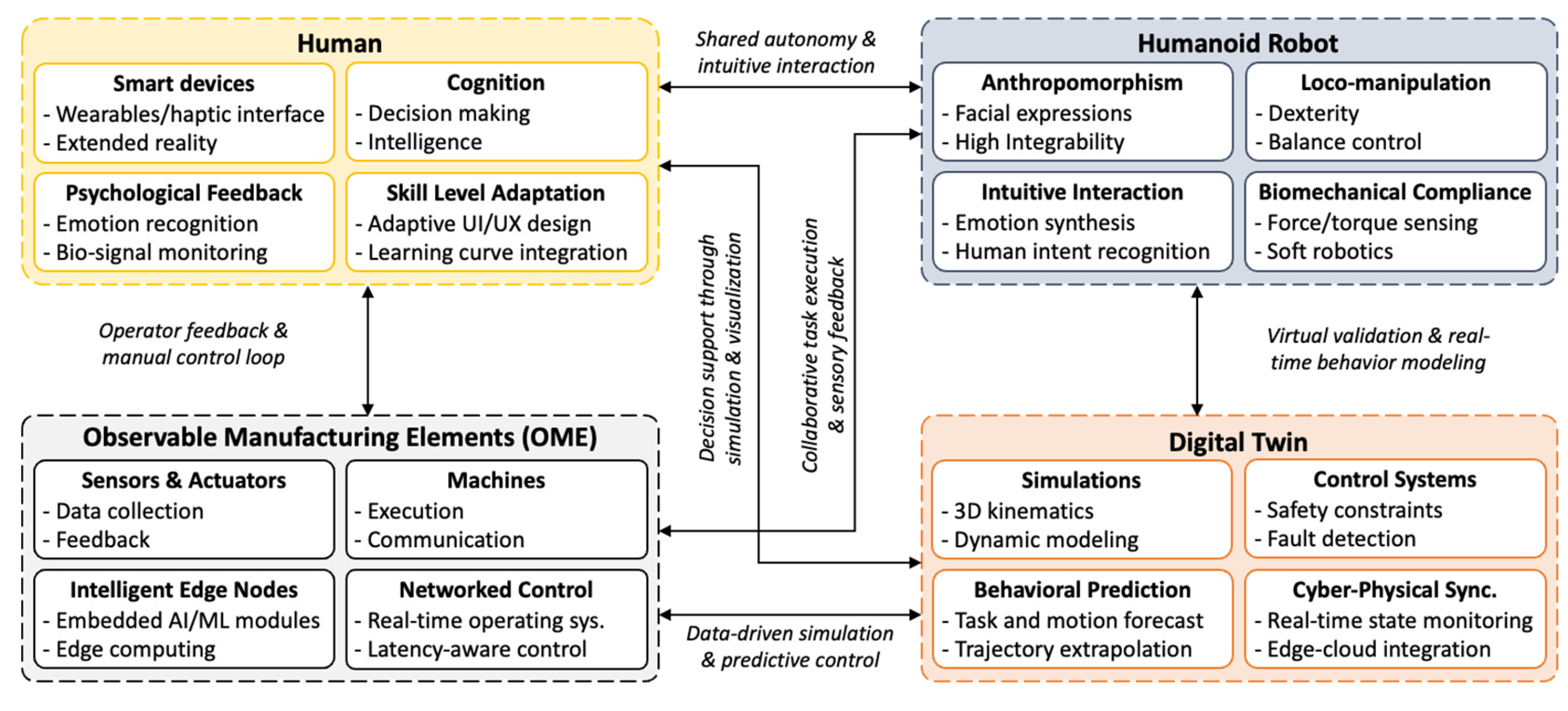

2.1. Human and Humanoid in-the-Loop

The human-in-the-loop (HitL) concept integrates human expertise with automated systems. It employs human decision-making abilities to enhance system performance, especially where human cognition is needed. It also enables workers to oversee and refine automated processes [

9]. However, seamless human-machine interaction is yet a challenge due to the rigid, non-intuitive interfaces of traditional robotic systems. This leads to inefficiencies in the manufacturing processes and increased cognitive load on human operators. The HHitL architecture (

Figure 2) addresses these gaps by incorporating HRs, which mimic human movements, gestures, and communication styles, yet it retains the core structure of the already established HitL in smart manufacturing [

10]. It also incorporates the presence and roles of HRs, the interactive and cognitive complexity of modern manufacturing, and the strategic objectives defined by Industry 5.0. The architecture comprises four interrelated modules: Human, Humanoid Robot, Observable Manufacturing Elements (OME), and Digital Twin, each containing four components. In the following, all four modules and their components will be discussed in detail.

The Observable Manufacturing Elements (OME) module enables sensing, actuation, and control within the manufacturing setting. It includes sensors and actuators, machines, intelligent edge nodes equipped with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) modules, and networked control systems for latency-aware coordination [

11,

12]. The OME module acts as the backbone of the system, providing the raw data and real-time responsiveness required for informed decision-making and adaptive task execution by both human and robotic agents [

13,

14].

The Human module positions the human operator as a cognitive, physical, and emotional agent within the manufacturing loop [

15]. It includes smart devices, cognition, psychological feedback, and skill level adaptation. These components enhance the personalized interaction and reduce cognitive load for operators with different levels of experience or cognitive capabilities, including beginner, intermediate, or expert [

10]. Additionally, the HR module can perform complex tasks and interact intuitively with the human module. This module encompasses anthropomorphism, loco-manipulation, intuitive interaction, and biomechanical compliance. The humanoid robot module can function as a manipulator and a socially intelligent collaborator. It can also understand and respond to human behavior in shared environments.

The Digital Twin module operates as the virtual counterpart to the physical system. It provides a real-time simulation and predictive control over the OMEs, humans and HRs involved in the manufacturing process [

16]. It also comprises behavioral prediction, and cyber-physical synchronization. This module ensures that humans and HRs can access actionable insights and foresight and enables scheduling/ planning, anomaly detection, continuous system optimization, and is a step toward zero-waste manufacturing.

2.2. Core Features and Enablers

The proposed ecosystem has four key features: Anthropomorphism, Perceptual Intelligence, Cognitive Adaptability, and Locomotion/Dexterity. Each core feature is realized through specific enablers that enable the ecosystem to bridge the gap between human intent and robotic execution. Core features of the proposed ecosystem and their corresponding enablers are shown in

Table 1.

Anthropomorphism enables HRs to emulate human-like physicality and communications. It facilitates natural human-robot collaboration by Body Structure analogous to human and Multi-Modal Interfaces. Body Structure, with components like arms/legs, head, and torso, mirrors human anatomy to perform tasks requiring dexterity, such as precise assembly, enhancing compatibility with human workflows. Multi-Modal Interfaces, processing inputs like text, speech, and images via foundation models (FM) and naturally visualizing them through immersive technologies, enable intuitive communication by interpreting verbal commands and gestures.

Perceptual intelligence equips HRs with the ability to understand and navigate complex manufacturing environments. To achieve this, multiple enablers need to be realized. For instance, Context Awareness and Sensors and Actuators, are required to enable HRs to navigate and understand complex manufacturing environments. Context Awareness processes structured and unstructured big data for real-time recognition of objects, processes, and environmental changes. Sensors and Actuators provide proprioceptive and exteroceptive feedback through sensor-embedded actuators, enabling precise environmental interaction and task execution. Together, these enablers improve responsiveness, precision, and adaptability within the HHitL ecosystem. In addition, real-time data analytics and simulations provide a clear understanding of the manufacturing setting to the user/operators, which can be a human, an HR, or their digital counterparts.

Cognitive adaptability empowers HRs to process and act on real-time information. It enhances decision-making in dynamic manufacturing contexts. Cognitive Adaptability relies on Realtime Data Analytics and Decision-Making to enable intelligent and autonomous operations in the HHitL ecosystem. Real-time Data Analytics leverages AI, ML, foundation models (FM), and NLP to optimize processes. Decision-Making integrates compliant control and cloud-fog-edge computing to facilitate autonomous, context-aware decisions. In addition, simulations and models in the manufacturing setting also enable the cognitive adaptability of the system by providing a digital replica of the physical aspects.

Locomotion and dexterity are critical for humanoid robots to execute physical tasks with precision and agility in manufacturing environments. They are driven by Robotics Engineering and Simulations and Models, ensuring precise and agile task execution in manufacturing environments. Robotics Engineering designs robust motion systems using kinematics and control systems. Simulations and Models use digital twins and physics-informed models to support navigation and path planning by optimizing movement and anticipating obstacles. In addition, the body structure is also a fundamental enabler of dexterity and locomotion, providing the mechanical framework and kinematic flexibility necessary for complex movement, balance, and task-oriented manipulation in humanoid robots.

2.3. Industry 5.0 and the Six Pillars (6P)

The HHitL ecosystem represents a paradigm shift in smart manufacturing and intelligent automation. It integrates the unique cognitive, perceptual, and physical abilities of both humans and humanoid robots within a unique framework. To achieve this, six foundational pillars, including Participation, Purpose, Preservation, Physical Assets, Projection, and Persistence, are proposed. These pillars align with the core principles of Industry 5.0: Human-Centricity, Sustainability, and Resiliency. Together, they generate a collaborative and intelligent system capable of navigating the complexities of modern industrial and societal demands.

Table 2 demonstrates the relationship between the six pillars and Industry 5.0 principles.

The human-centricity dimension of the HHitL ecosystem is grounded in the pillars of Participation and Purpose. Participation emphasizes the active and ergonomic involvement of humans in collaboration with HRs. It supports human and HR adaptation, seamless multimodal interaction. It also enables workers to interact naturally and safely with intelligent robotic agents. Complementing this, the Purpose pillar addresses the ethical and social responsibilities of deploying humanoid robots. It promotes a human-centric design that prioritizes human well-being, and assistive role of HRs in the manufacturing processes.

In addition, sustainability within the HHitL architecture is achieved through the pillars of Preservation and Physical Assets. Preservation focuses on minimizing the environmental impact of robotic and manufacturing operations through resource efficiency, waste reduction, and support for green manufacturing practices. It reinforces the need for systems that are not only intelligent but also eco-conscious by design. The Physical Assets complements this by emphasizing the optimal use and lifecycle management of hardware and infrastructure. By integrating energy-aware robotics and smart infrastructure, HHitL becomes a vehicle for sustainable automation that reduces environmental footprints while maintaining high-performance standards in industry.

Finally, to navigate uncertain and dynamic environments, and achieve resiliency, the HHitL ecosystem incorporates pillars of Projection and Persistence. Projection involves the capacity for forward-thinking through predictive analytics, learning, and scenario planning, enabling proactive responses to emerging challenges. It equips the system with strategic foresight necessary for long-term viability. Persistence, on the other hand, ensures that the system can adapt autonomously to disruptions, maintain operational continuity, and recover safely from failures.

3. Challenges and Outlooks

3.1. Challenges

One of the primary challenges in deploying humanoid robots in manufacturing lies in real-time perception and context awareness. Despite significant advancements in computer vision, multimodal sensing, and ML, humanoid robots still struggle to reliably interpret dynamic, unstructured environments such as shop floors, and real industrial setting where unexpected changes are inevitable The integration of perception systems that can understand intent, emotion, and environmental complexity remains a critical barrier.

Another major concern is physical robustness and dexterity [

6]. Most HRs still lack the mechanical endurance and precision required for continuous industrial tasks, particularly those involving exposure to contaminants or hazardous conditions. Achieving a balance between anthropomorphic factors and industrial durability is still an open engineering challenge. In addition, smart manufacturing environments often comprise heterogeneous systems with varied communication protocols and data standards. Seamless integration requires modular, adaptive middleware layers and standardized interfaces, which are currently underdeveloped in the context of humanoid robotics.

From a human-centered perspective, socio-technical alignment remains an important issue. Operators may resist working alongside HRs due to trust, safety, or job displacement concerns. Ensuring transparent, intuitive interaction and developing ergonomic collaboration models are essential for acceptance and long-term integration [

5]. Finally, cost and scalability continue to limit deployment. HRs remain significantly more expensive than traditional industrial robots due to their complex kinematics, sensing systems, and control architectures. This limits adoption to pilot projects or high-value manufacturing contexts, leaving mass-market applications out of reach.

3.2. Outlooks

Despite these challenges, the outlook for humanoid robots in smart manufacturing is promising. Advances in foundation models, AI, and multi-modal interfaces rapidly improve robots’ ability to perceive, understand, and act in complex environments. These technologies will soon enable HRs to perform more diverse and cognitively demanding tasks with minimal human supervision.

In parallel, the development of modular hardware architectures and soft robotics is expanding the capabilities of humanoid platforms in terms of dexterity, safety, and energy efficiency. These improvements will enable robots to handle delicate assembly tasks, adapt to diverse tools, and interact safely with humans in shared spaces. The growing maturity of digital twin technologies will further support predictive maintenance, behavior simulation, and collaborative decision-making between humans and HRs. Digital twins will serve as real-time cognitive companions for HRs, allowing them to test behaviors virtually before executing them physically, which improves both safety and adaptability. In addition, standardization efforts are expected to accelerate, enabling better interoperability between humanoid robots, industrial systems, and cloud-based manufacturing platforms. Open-source frameworks and cross-platform middleware will facilitate smoother integration and foster a more competitive ecosystem.

4. Summary

This paper proposed the HHitL Ecosystem as a novel framework for smart manufacturing in the Industry 5.0 era, emphasizing human-centricity, sustainability, and resiliency through a structured 6P architecture and four interconnected modules of Human, Humanoid Robot, Observable Manufacturing Elements, and Digital Twin. Core features of the ecosystem include anthropomorphism, cognitive adaptability, perceptual intelligence, and dexterity/locomotion. While numerous challenges exist, the outlook for realizing the HHitL ecosystem is optimistic. In conclusion, the HHitL ecosystem offers a forward-looking perspective for the next generation of manufacturing systems, where human values and robotic intelligence coexist to create factories that are not only productive but also adaptive and ethical.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program [grant number NRF-2022R1A2C2005879] through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIT).

References

- X. Xu, Y. X. Xu, Y. Lu, B. Vogel-Heuser, L. Wang, Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception, J. Manuf. Syst., 2021, 61.

- Sheth, A. Kusiak, Resiliency of Smart Manufacturing Enterprises via Information Integration, Journal of industrial information integration, 2022, 28. [CrossRef]

- S. Nahavandi, Industry 5.0—A Human-Centric Solution, Sustainability, 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, Y. J. Yang, Y. Liu, P.L. Morgan, Human–machine interaction towards Industry 5.0: Human-centric smart manufacturing, Digital Engineering, 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Malik, T. Masood, A. Brem, Intelligent humanoids in manufacturing to address worker shortage and skill gaps: Case of Tesla Optimus, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gu, J. Z. Gu, J. Li, W. Shen, W. Yu, Z. Xie, S. McCrory, X. Cheng, A. Shamsah, R. Griffin, C.K. Liu, A. Kheddar, X.B. Peng, Y. Zhu, G. Shi, Q. Nguyen, G. Cheng, H. Gao, Y. Zhao, Humanoid Locomotion and Manipulation: Current Progress and Challenges in Control, Planning, and Learning, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghobakhloo, H.A. M. Ghobakhloo, H.A. Mahdiraji, M. Iranmanesh, V. Jafari-Sadeghi, From Industry 4.0 Digital Manufacturing to Industry 5.0 Digital Society: a Roadmap Toward Human-Centric, Sustainable, and Resilient Production, Information systems frontiers, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Z. Y. Li, Z. Li, Y. Duan, A. Spulber, Physical artificial intelligence (PAI): the next-generation artificial intelligence, Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering, 2023, 24.

- Wang, P. Zheng, Y. Yin, A. Shih, L. Wang, Toward human-centric smart manufacturing: A human-cyber-physical systems (HCPS) perspective, Journal of manufacturing systems, 2022, 63. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S. Bajestani, J.Y. Lee, S. Shin, S.D. Noh, Introduction of Human-in-the-Loop in Smart Manufacturing (H-SM), International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Smart Technology, 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Wallner, B. Zwölfer, T. Trautner, F. Bleicher, Digital Twin Development and Operation of a Flexible Manufacturing Cell using ISO 23247, Procedia CIRP, 2023, 120. [CrossRef]

- Bong Kim, G. Shao, G. Jo, A digital twin implementation architecture for wire + arc additive manufacturing based on ISO 23247, Manufacturing Letters, 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- M. Kang, D. M. Kang, D. Lee, M.S. Bajestani, D.B. Kim, S.D. Noh, Edge Computing-Based Digital Twin Framework Based on ISO 23247 for Enhancing Data Processing Capabilities, Machines (Basel), 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- G. Shao, G. M. Raimondo, Use Case Scenarios for Digital Twin Implementation Based on ISO 23247, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, S. H. Chen, S. Li, J. Fan, A. Duan, C. Yang, D. Navarro-Alarcon, P. Zheng, Human-in-the-Loop Robot Learning for Smart Manufacturing: A Human-Centric Perspective, TASE, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.F. Sahed, Z. Tasneem, P. Das, F.R. Badal, M.F. Ali, M.H. Ahamed, S.H. Abhi, S.K. Sarker, S.K. Das, M.M. Hasan, M.M. Islam, M.R. Islam, Towards next generation digital twin in robotics: Trends, scopes, challenges, and future, Heliyon, 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- R. Kühne, J. R. Kühne, J. Peter, Anthropomorphism in human–robot interactions: a multidimensional conceptualization, Communication theory, 2023, 33. [CrossRef]

- Tusseyeva, A. Sandygulova, M. Rubagotti, Perceived Intelligence in Human-Robot Interaction: A Review, Access, 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Tanevska, F. Rea, G. Sandini, L. Canamero, A. Sciutti, A Cognitive Architecture for Socially Adaptable Robots, DEVLRN 195–200. [CrossRef]

- J. Aguilar, T. J. Aguilar, T. Zhang, F. Qian, M. Kingsbury, B. McInroe, N. Mazouchova, C. Li, R. Maladen, C. Gong, M. Travers, R.L. Hatton, H. Choset, P.B. Umbanhowar, D.I. Goldman, A review on locomotion robophysics: the study of movement at the intersection of robotics, soft matter and dynamical systems, RoPP, 2016, 79. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).