Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Asthma

1.2. Role of Epigenetics in Asthma

1.3. Significance of Studying Epigenetically Important Proteins

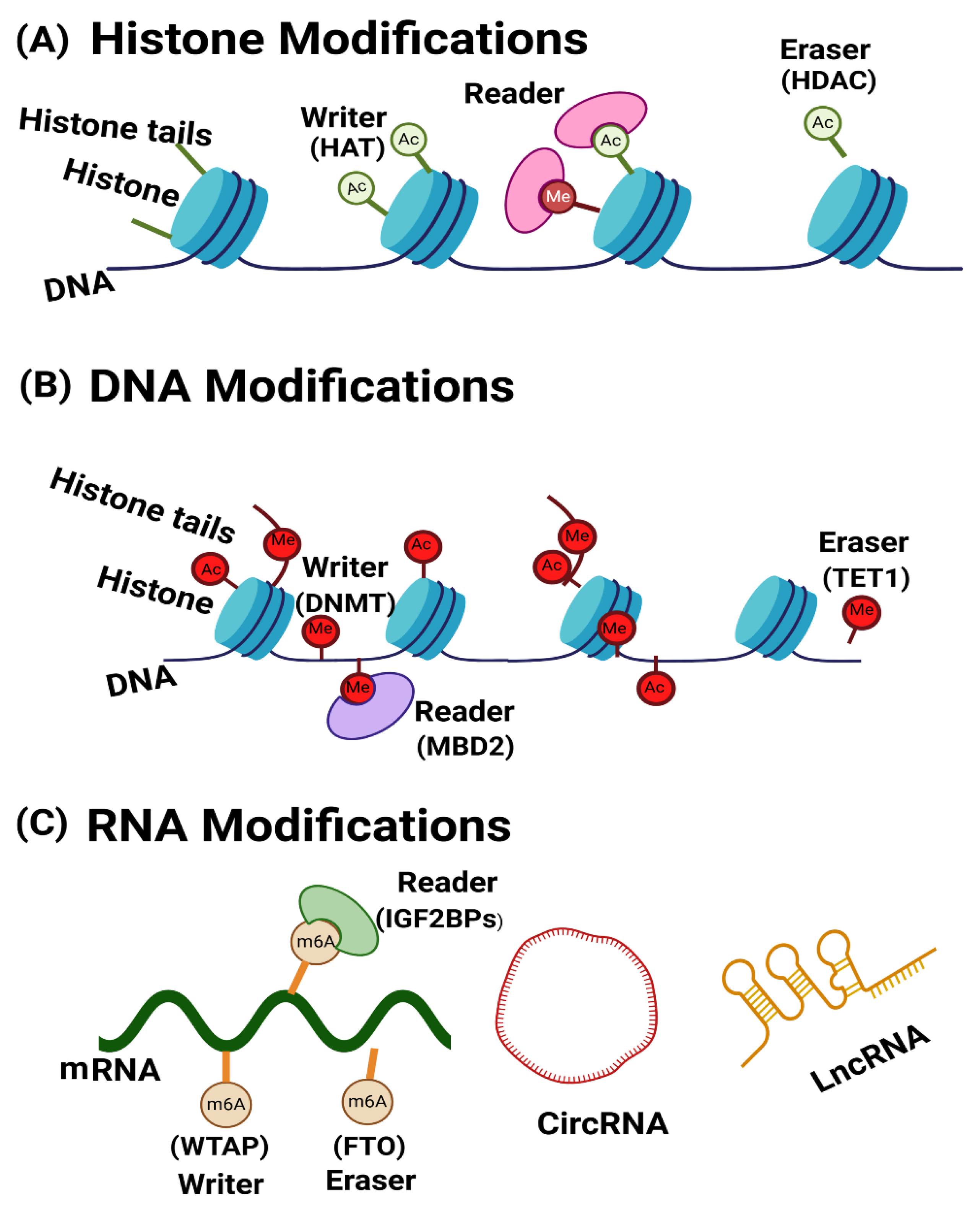

1.4. Overview of Epigenetic Mechanisms

2. Role of Key Epigenetic Proteins in Asthma Pathogenesis

3. Epigenetic Regulators in Asthma: Writers, Readers, and Erasers of Histone Modifications

3.1. The Role of HATs in Asthma

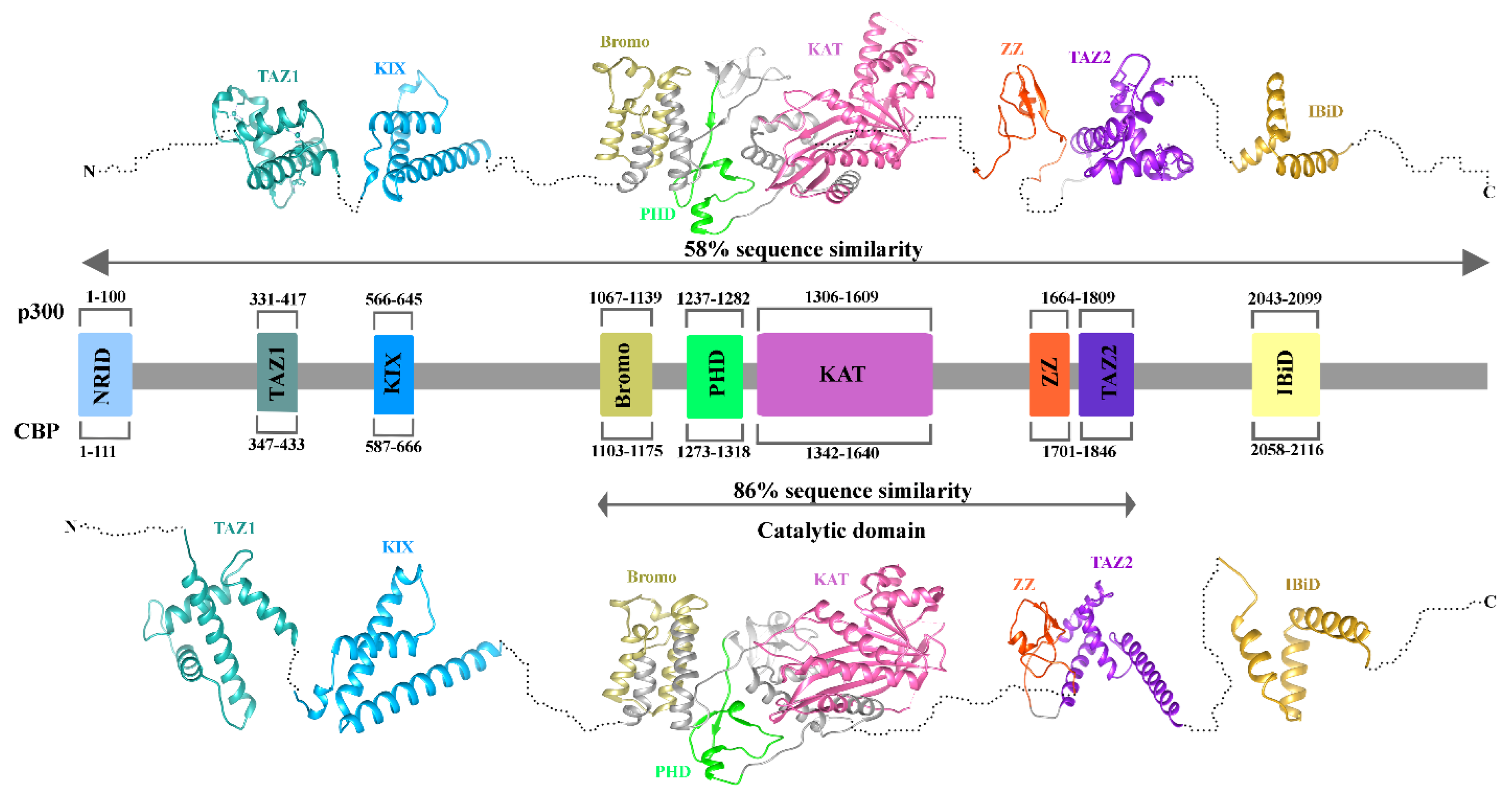

3.2. Structure of P300/CBP

3.3. The role of Class III histone Deacetylases in Asthma

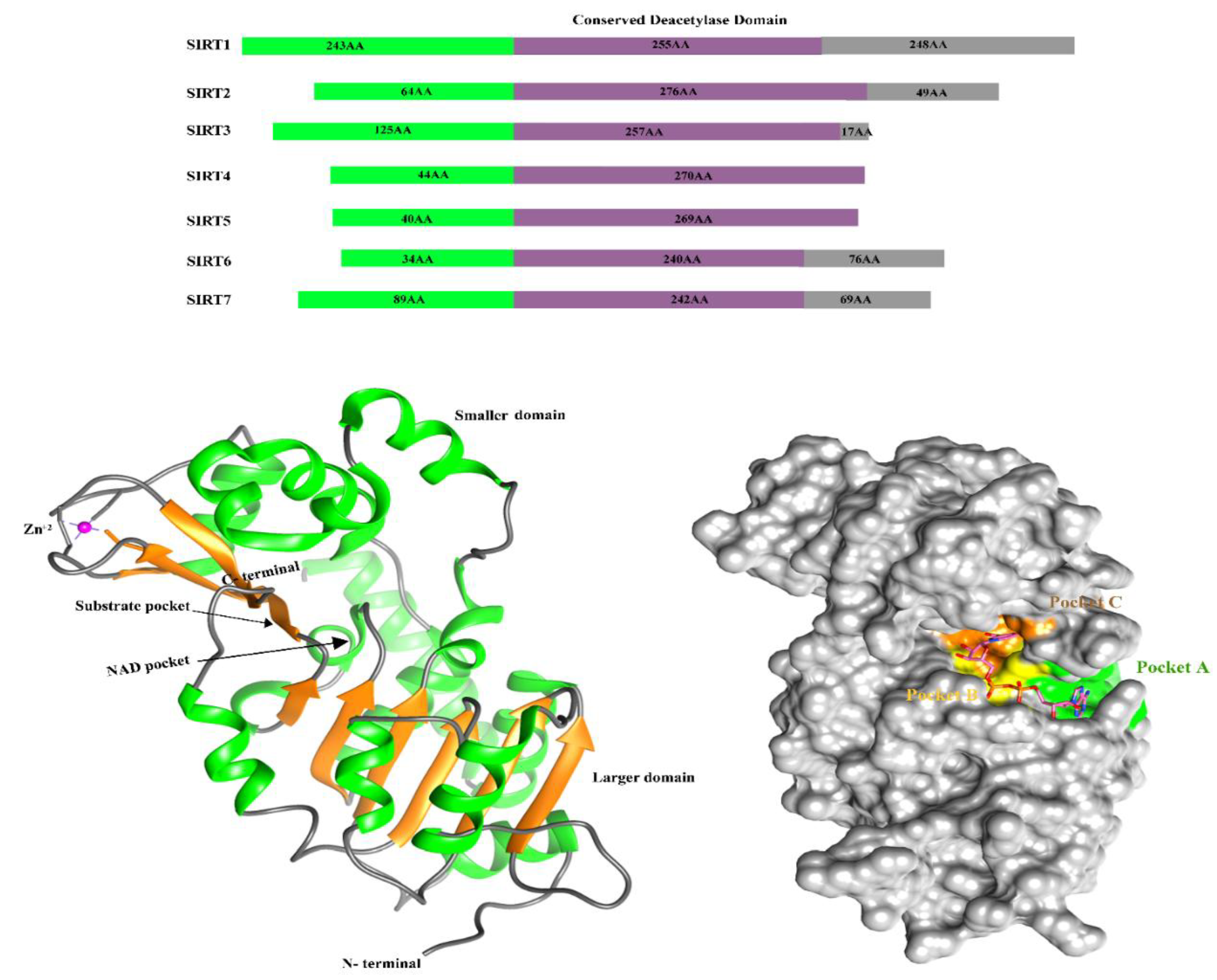

3.4. Structure of Sirtuin

4. Epigenetic Regulators in Asthma: Writers, Readers, and Erasers of DNA Modifications

4.1. DNMT1 and DNMT3a Role in Asthma

4.2. Structure of DNMT1 and DNMT3a

4.3. Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain Protein 2 MBD2 Role in Asthma

4.4. Structure of Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain Protein 2 (MBD2)

4.5. Role of TET1 in Asthma and Its Structural Information

5. Epigenetic Regulators in Asthma: Writers, Readers, and Erasers of RNA Modifications

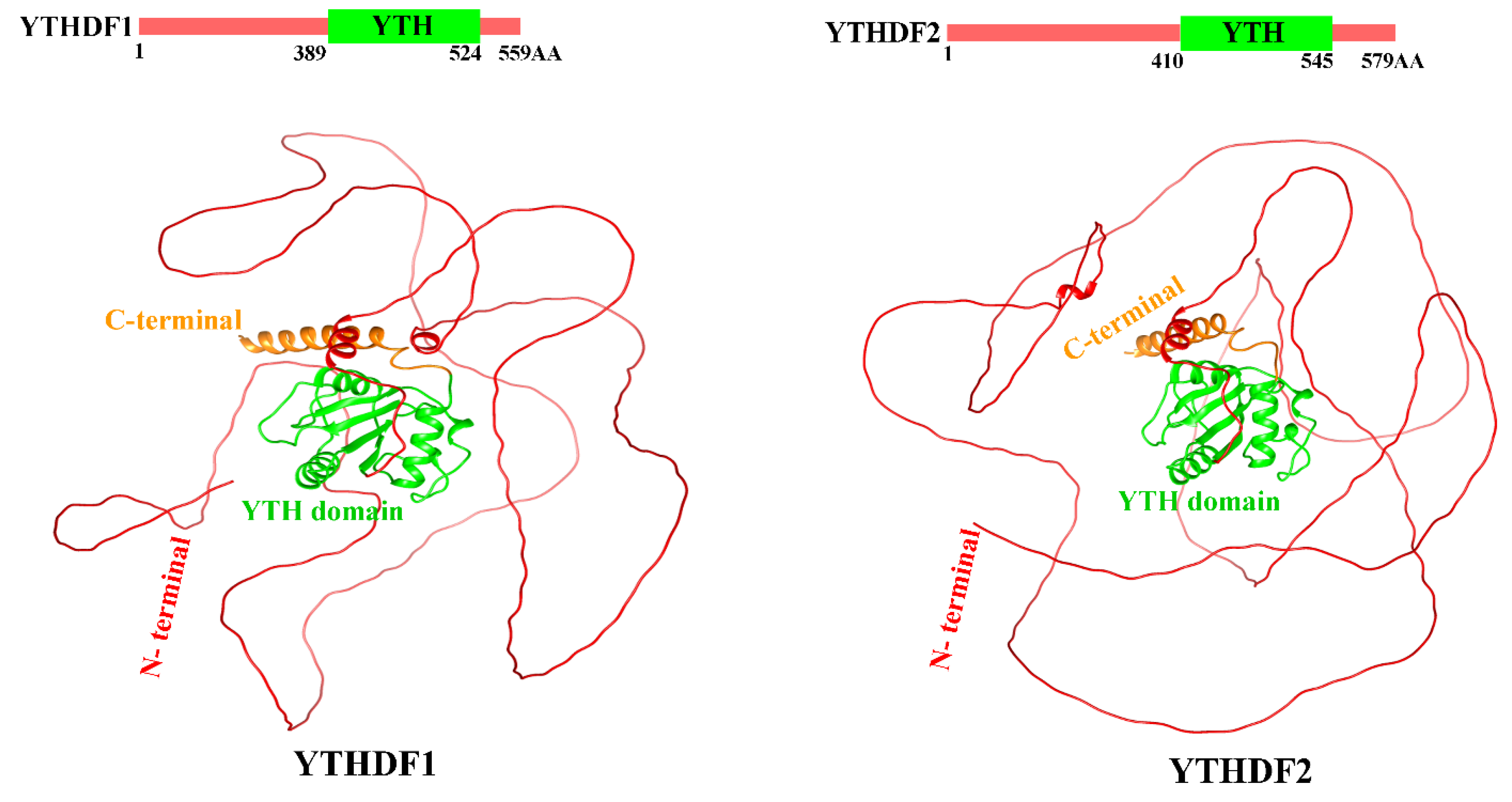

5.1. Role of Reader Protein YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 in Asthma

5.2. Structure of YTHDF Proteins

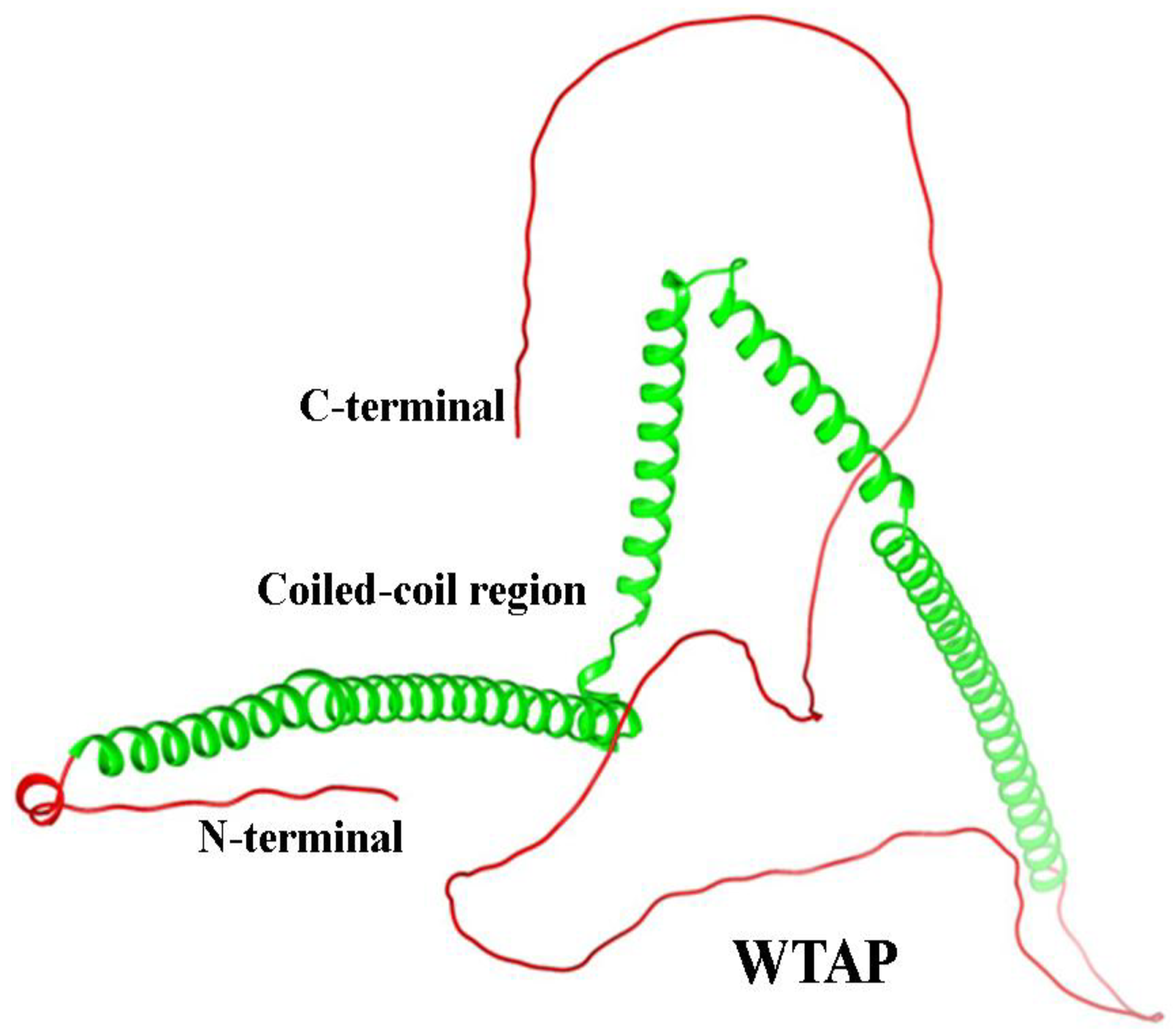

5.3. WTAP Role in Asthma

5.4. Structure of WTAP Protein

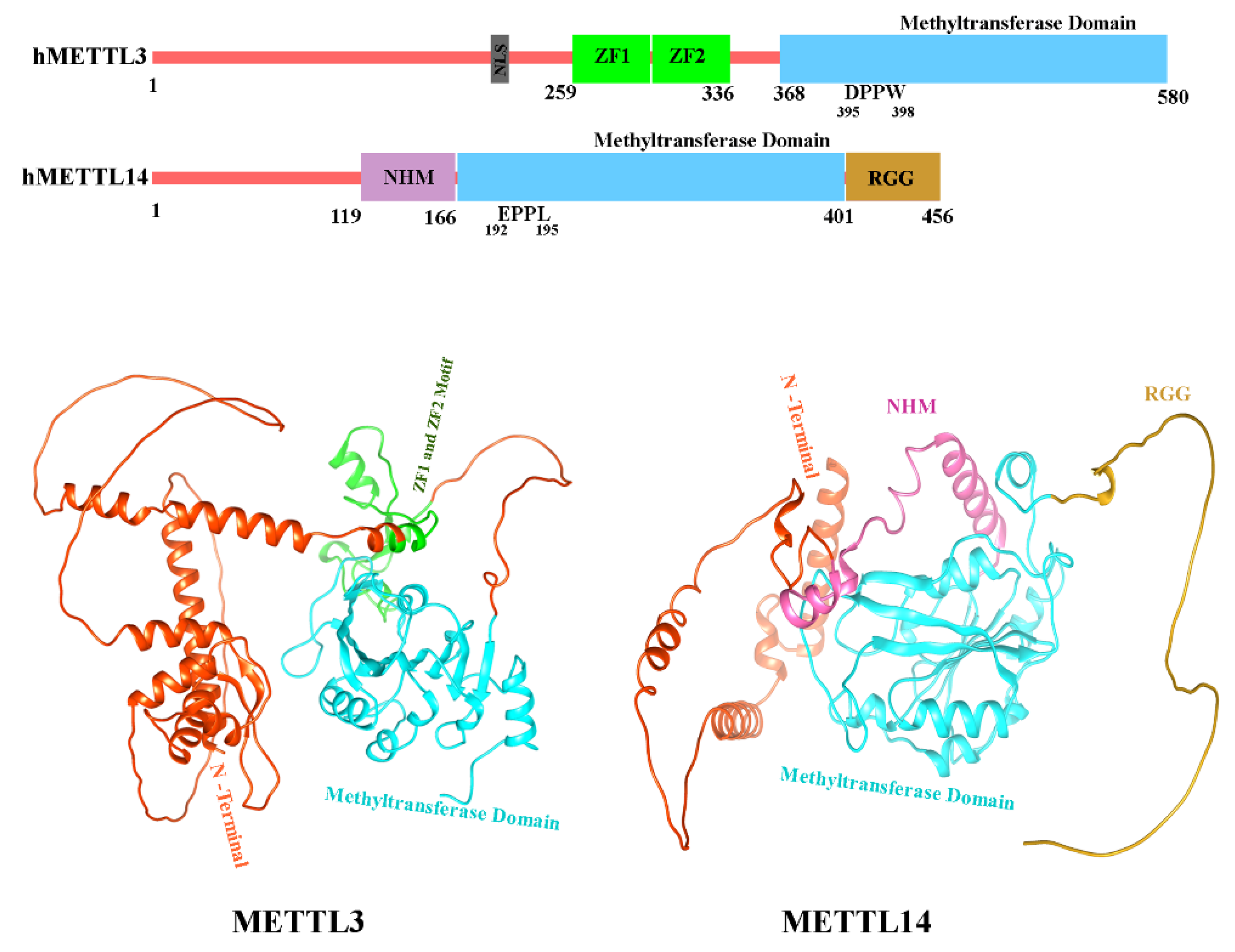

5.5. METTL3 and METTL14 Role in Asthma

5.6. Structure of METTL3 and METTL14

5.7. Role of IGF2BP2 in Asthma

5.8. Structure of IGF2BP2

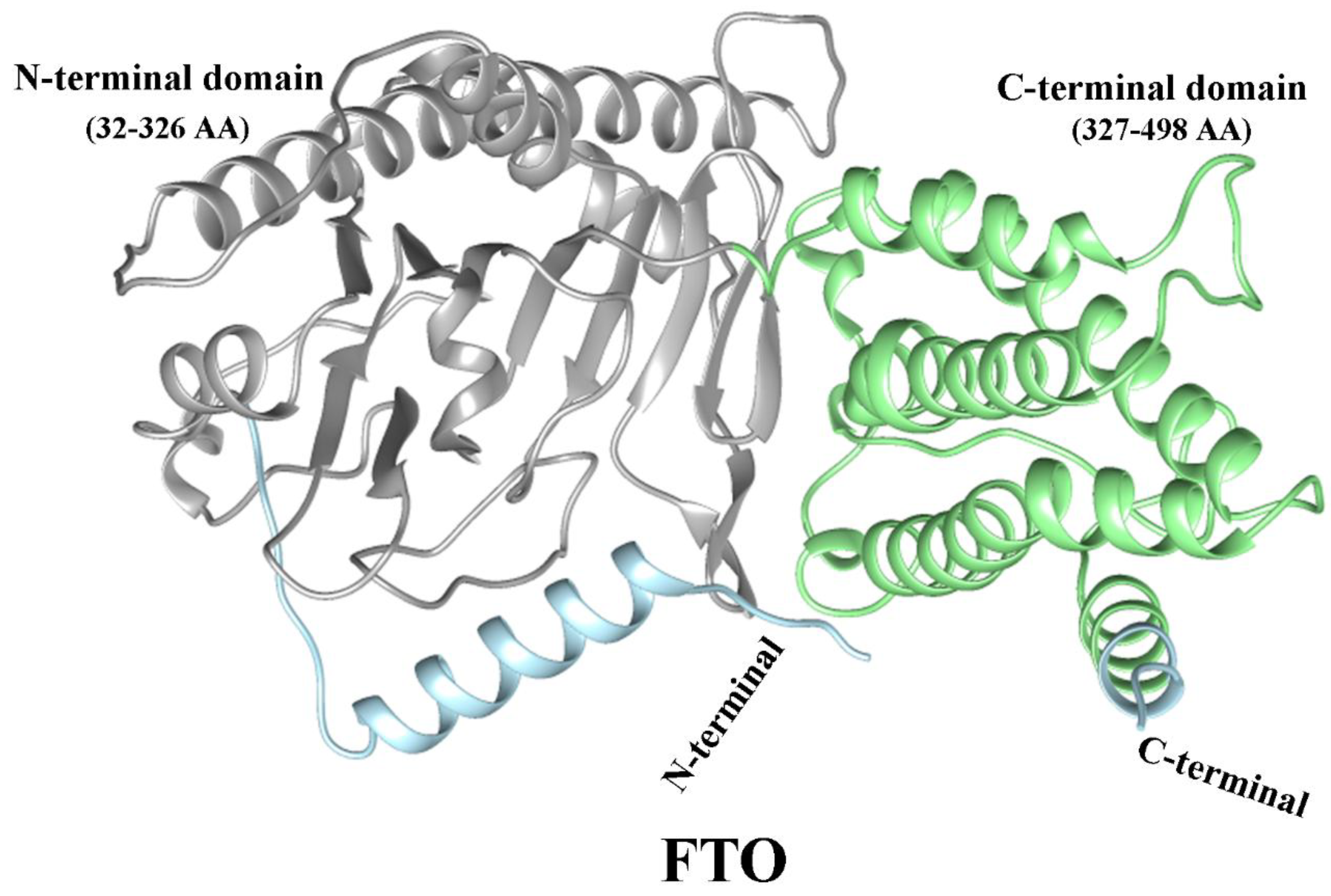

5.9. Role of FTO in Asthma

5.10. Structure of FTO

6. Conclusions and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBP | CREB Binding Protein |

| SIRT | Silent Information Regulator Proteins |

| DNMT1 | DNA (cytosine-5)-Methyltransferase 1 |

| IGF2BP2 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 mRNA-Binding Protein 2 |

| MBD2 | Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 2 |

| TET1 | Ten-Eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 1 |

| FTO | Fat Mass and Obesity Associated Gene |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| PTMs | Posttranslational Modifications |

| HATs | Histone Acetylases |

| HDACs | Histone Deacetylases |

| TFs | Transcription Factors |

| METTL3 | Methyltransferase-like 3 |

| WTAP | Wilms’ Tumor 1-Associating Protein |

| IBiD | interferon-binding transactivation domain |

| PWWP | Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro |

| ADD | Atrx-Dnmt3-Dnmt3l |

| DSBH | double-stranded β helix |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| ASMC | airway Smooth Muscle Cell |

| ZF1 | zinc finger motifs |

| RRM1 | RNA Recognition Motif 1 |

| RRM2 | RNA Recognition Motif 2 |

| KH | K Homology domain |

References

- Erle, D.J.; Sheppard, D. The Cell Biology of Asthma. Journal of Cell Biology 2014, 205, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrecht, B.N.; Hammad, H. The Immunology of Asthma. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. The Basic Immunology of Asthma. Cell 2021, 184, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Yang, T.; Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Bai, C.; Kang, J.; Ran, P.; Shen, H.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Management of Asthma in China: A National Cross-Sectional Study. The Lancet 2019, 394, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; Guo, M.; Li, X. Trends in Prevalence and Incidence of Chronic Respiratory Diseases from 1990 to 2017. Respir Res 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stikker, B.S.; Hendriks, R.W.; Stadhouders, R. Decoding the Genetic and Epigenetic Basis of Asthma. Allergy 2023, 78, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapri, A.; Pant, S.; Gupta, N.; Paliwal, S.; Nain, S. Asthma History, Current Situation, an Overview of Its Control History, Challenges, and Ongoing Management Programs: An Updated Review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences 2023, 93, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, A.; Brightling, C.; Pedersen, S.E.; Reddel, H.K. Seminar Asthma. Lancet 2018, 391, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edris, A.; den Dekker, H.T.; Melén, E.; Lahousse, L. Epigenome-Wide Association Studies in Asthma: A Systematic Review. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2019, 49, 953–968. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries, A.; Vercelli, D. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016, 13, S48–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovinsky-Desir, S.; Miller, R.L. Epigenetics, Asthma, and Allergic Diseases: A Review of the Latest Advancements. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2012, 12, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Mortaz, E.; Adcock, I.; Moin, M. Role of Epigenetics in the Pathogenesis of Asthma. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kabesch, M.; Adcock, I.M. Epigenetics in Asthma and COPD. Biochimie 2012, 94, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alashkar Alhamwe, B.; Miethe, S.; von Strandmann, E.; Potaczek, D.P.; Garn, H. Epigenetic Regulation of Airway Epithelium Immune Functions in Asthma. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I. V; Pedersen, B.S.; Liu, A.H.; O’Connor, G.T.; Pillai, D.; Kattan, M.; Misiak, R.T.; Gruchalla, R.; Szefler, S.J.; Hershey, G.K.K.; et al. The Nasal Methylome and Childhood Atopic Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2017, 139, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.-J.; Jun, J.; Chang, H.S.; Park, J.S.; Park, C.-S. Epigenetic Changes in Asthma: Role of DNA CpG Methylation. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2020, 83, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudon Thibeault, A.-A.; Laprise, C. Cell-Specific DNA Methylation Signatures in Asthma. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinberg, D.; Allis, D.; Jenuwein, T. Epigenetics 2007.

- Arrowsmith, C.H.; Bountra, C.; Fish, P. V; Lee, K.; Schapira, M. Epigenetic Protein Families: A New Frontier for Drug Discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacal, I.; Ventura, R. Epigenetic Inheritance: Concepts, Mechanisms and Perspectives. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. Chromosomal DNA and Its Packaging in the Chromatin Fiber. In Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition; Garland science, 2002.

- Harb, H.; Alhamwe, B.A.; Garn, H.; Renz, H.; Potaczek, D.P. Recent Developments in Epigenetics of Pediatric Asthma. Curr Opin Pediatr 2016, 28, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potaczek, D.P.; Harb, H.; Michel, S.; Alhamwe, B.A.; Renz, H.; Tost, J. Epigenetics and Allergy: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 539–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.P. da C.; Schroen, B.; Kuster, G.M.; Robinson, E.L.; Ford, K.; Squire, I.B.; Heymans, S.; Martelli, F.; Emanueli, C.; Devaux, Y.; et al. Regulatory RNAs in Heart Failure. Circulation 2020, 141, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, O.; Baccarelli, A.A. Environmental Health and Long Non-Coding RNAs. Curr Environ Health Rep 2016, 3, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Niu, F.; Humburg, B.A.; Liao, K.; Bendi, S.; Callen, S.; Fox, H.S.; Buch, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs and Their Role in Disease Pathogenesis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 18648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Yang, I. V; Schwartz, D.A. Epigenetic Regulation of Immune Function in Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2022, 150, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Xiao, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, H.; Yang, L.; Xie, X.; et al. RNA M6A Methylation Modulates Airway Inflammation in Allergic Asthma via PTX3-Dependent Macrophage Homeostasis. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyniak, P.; Krawczyk, K.; Swati, A.; Tan, G.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Karouzakis, E.; Dreher, A.; Jakiela, B.; Altunbulakli, C.; Sanak, M.; et al. Inhibition of CpG Methylation Improves the Barrier Integrity of Bronchial Epithelial Cells in Asthma. Authorea Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seumois, G.; Chavez, L.; Gerasimova, A.; Lienhard, M.; Omran, N.; Kalinke, L.; Vedanayagam, M.; Ganesan, A.P. V; Chawla, A.; Djukanović, R.; et al. Epigenomic Analysis of Primary Human T Cells Reveals Enhancers Associated with TH2 Memory Cell Differentiation and Asthma Susceptibility. Nat Immunol 2014, 15, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, A.; Chavez, L.; Li, B.; Seumois, G.; Greenbaum, J.; Rao, A.; Vijayanand, P.; Peters, B. Predicting Cell Types and Genetic Variations Contributing to Disease by Combining GWAS and Epigenetic Data. PLoS One 2013, 8, e54359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, K.; Shaheen, F.; Koo, H.-K.; Booth, S.; Knight, D.A.; Hackett, T.-L. Elevated H3K18 Acetylation in Airway Epithelial Cells of Asthmatic Subjects. Respir Res 2015, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, R.; Furukawa, Y.; Morita, M.; Iimura, Y.; Silva, F.P.; Li, M.; Yagyu, R.; Nakamura, Y. SMYD3 Encodes a Histone Methyltransferase Involved in the Proliferation of Cancer Cells. Nat Cell Biol 2004, 6, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, K.W.; Brown, M.; Park, F.; Emtage, S.; Harriss, J.; Das, C.; Zhu, L.; Crew, A.; Arnold, L.; Shaaban, S.; et al. Structural and Functional Profiling of the Human Histone Methyltransferase SMYD3. PLoS One 2011, 6, e22290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, P.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Wanke, K.; Sokolowska, M.; Bendelja, K.; Rückert, B.; Globinska, A.; Jakiela, B.; Kast, J.I.; Idzko, M.; et al. Regulation of Bronchial Epithelial Barrier Integrity by Type 2 Cytokines and Histone Deacetylases in Asthmatic Patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2017, 139, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, P.; Ahmad, T.; Adcock, I.M. The Role of Histone Deacetylases in Asthma and Allergic Diseases. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2008, 121, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leus, N.G.J.; Zwinderman, M.R.H.; Dekker, F.J. Histone Deacetylase 3 (HDAC 3) as Emerging Drug Target in NF-ΚB-Mediated Inflammation. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2016, 33, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, G. Roles of Sirtuins in Asthma. Respir Res 2022, 23, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-Y.; Hur, G.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Rho, M.-C. AGK2 Ameliorates Mast Cell-Mediated Allergic Airway Inflammation and Fibrosis by Inhibiting FcRI/TGF-β Signaling Pathway. Pharmacol Res 2020, 159, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, J. SIRT3 Regulates Bronchial Epithelium Apoptosis and Aggravates Airway Inflammation in Asthma. Mol Med Rep 2022, 25, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-Y.; Gu, S.; Lee, S.-M.; Park, B.-H. Overexpression of Sirtuin 6 Suppresses Allergic Airway Inflammation through Deacetylation of GATA3. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 138, 1452–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, N.; Ou, L.; Leng, L.; Pan, J.; Wang, X. SIRT7 Regulates the TGF-Β1-Induced Proliferation and Migration of Mouse Airway Smooth Muscle Cells by Modulating the Expression of TGF-β Receptor I. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 104, 781–787. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, M.; Chattopadhyay, B.D.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, K.; Verma, D. DNA Methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) Induced the Expression of Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling3 (Socs3) in a Mouse Model of Asthma. Mol Biol Rep 2014, 41, 4413–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, E.T.; Du, J.; Glosson, N.L.; Kaplan, M.H. DNA Methyltransferase 3a Limits the Expression of Interleukin-13 in T Helper 2 Cells and Allergic Airway Inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y.; He, Y.; Wasti, B.; Duan, W.; Jia, J.; Li, D.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, D.; Ma, L.; et al. MBD2 as a Potential Novel Biomarker for Identifying Severe Asthma with Different Endotypes. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 693605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somineni, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Myers, J.M.B.; Kovacic, M.B.; Ulm, A.; Jurcak, N.; Ryan, P.H.; Hershey, G.K.K.; Ji, H. Ten-Eleven Translocation 1 (TET1) Methylation Is Associated with Childhood Asthma and Traffic-Related Air Pollution. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 137, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Sun, F.; Cai, X.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Shang, Y. Significance of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Regulators in the Diagnosis and Subtype Classification of Childhood Asthma Using the Gene Expression Omnibus Database. Front Genet 2021, 12, 634162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Dai, L. WTAP Promotes the Excessive Proliferation of Airway Smooth Muscle Cells in Asthma by Enhancing AXIN1 Levels Through the Recognition of YTHDF2. Biochem Genet 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Ma, L.; Xiang, X.; Jia, J.; Ji, X.; et al. METTL3 Mediates SOX5 M6A Methylation in Bronchial Epithelial Cells to Attenuate Th2 Cell Differentiation in T2 Asthma. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Su, W.; Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Shuai, J.; et al. YTHDF1-CLOCK Axis Contributes to Pathogenesis of Allergic Airway Inflammation through LLPS. Cell Rep 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Hao, Y.Q.; Wang, C.; Gao, P. Role and Regulators of N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) RNA Methylation in Inflammatory Subtypes of Asthma: A Comprehensive Review. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1360607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Feng, P.; Liu, R.; Li, G.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ji, C.; Chen, D.; et al. The M6A Reader IGF2BP2 Regulates Macrophage Phenotypic Activation and Inflammatory Diseases by Stabilizing TSC1 and PPARγ. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; He, X.; Liu, S.; Ran, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, M.; Niu, B.; Xiong, Y.; Li, G. Oxidative Stress-Mediated Activation of FTO Exacerbates Impairment of the Epithelial Barrier by up-Regulating IKBKB via N6-Methyladenosine-Dependent MRNA Stability in Asthmatic Mice Exposed to PM2. 5. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2024, 272, 116067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potaczek, D.P.; Bazan-Socha, S.; Wypasek, E.; Wygrecka, M.; Garn, H. Recent Developments in the Role of Histone Acetylation in Asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2024, 185, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaskhar Alhamwe, B.; Khalaila, R.; Wolf, J.; von Bülow, V.; Harb, H.; Alhamdan, F.; Hii, C.S.; Prescott, S.L.; Ferrante, A.; Renz, H.; et al. Histone Modifications and Their Role in Epigenetics of Atopy and Allergic Diseases. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2018, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Swygert, S.G.; Peterson, C.L. Chromatin Dynamics: Interplay between Remodeling Enzymes and Histone Modifications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2014, 1839, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-J.; Man, N.; Tan, Y.; Nimer, S.D.; Wang, L. The Role of Histone Acetyltransferases in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Front Oncol 2015, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wapenaar, H.; Dekker, F.J. Histone Acetyltransferases: Challenges in Targeting Bi-Substrate Enzymes. Clin Epigenetics 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmorstein, R.; Zhou, M.-M. Writers and Readers of Histone Acetylation: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6, a018762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, I.M.; Ford, P.; Ito, K.; Barnes, P.J. Epigenetics and Airways Disease. Respir Res 2006, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschey, M.D. Old Enzymes, New Tricks: Sirtuins Are NAD+-Dependent de-Acylases. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potaczek, D.P.; Alashkar Alhamwe, B.; Miethe, S.; Garn, H. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Allergy Development and Prevention. In Allergic diseases–from basic mechanisms to comprehensive management and prevention; Springer, 2021; pp. 331–357.

- Gong, F.; Chiu, L.-Y.; Miller, K.M. Acetylation Reader Proteins: Linking Acetylation Signaling to Genome Maintenance and Cancer. PLoS Genet 2016, 12, e1006272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wei, T.; Cai, Y.; Jin, J. Small Molecules Targeting the Specific Domains of Histone-Mark Readers in Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, T.; Hatano, M.; Satake, H.; Ikari, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Tsuruoka, N.; Watanabe-Takano, H.; Fujimura, L.; Sakamoto, A.; Hirata, H.; et al. Development of Chronic Allergic Responses by Dampening Bcl6-Mediated Suppressor Activity in Memory T Helper 2 Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, E741–E750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J.; Adcock, I.M.; Ito, K. Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation: Importance in Inflammatory Lung Diseases. European Respiratory Journal 2005, 25, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardhana, L.P.; Gibson, P.G.; Simpson, J.L.; Powell, H.; Baines, K.J. Activity and Expression of Histone Acetylases and Deacetylases in Inflammatory Phenotypes of Asthma. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2014, 44, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, L.-L.; Jin, R.; Zhu, L.-H.; Xu, H.-G.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, J.-Y.; Zhou, G.-P. Promoter Characterization and Role of CAMP/PKA/CREB in the Basal Transcription of the Mouse ORMDL3 Gene. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Xu, H.-G.; Yuan, W.-X.; Zhuang, L.-L.; Liu, L.-F.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, L.-H.; Liu, J.-Y.; Zhou, G.-P. Mechanisms Elevating ORMDL3 Expression in Recurrent Wheeze Patients: Role of Ets-1, P300 and CREB. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012, 44, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Hottiger, M.O. Histone Acetyl Transferases: A Role in DNA Repair and DNA Replication. J Mol Med 2002, 80, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Marshall, C.B.; Ikura, M. Transcriptional/Epigenetic Regulator CBP/P300 in Tumorigenesis: Structural and Functional Versatility in Target Recognition. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2013, 70, 3989–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdasco, M.; Esteller, M. Genetic Syndromes Caused by Mutations in Epigenetic Genes. Hum Genet 2013, 132, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Shang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q. P300 Mediates the Histone Acetylation of ORMDL3 to Affect Airway Inflammation and Remodeling in Asthma. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 76, 105885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, D.; Wang, D. Increased P300/CBP Expression in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Is Associated with Interleukin-17 and Prognosis. Clin Respir J 2020, 14, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, S.-P.; Branton, P.E. Detection of Cellular Proteins Associated with Human Adenovirus Type 5 Early Region 1A Polypeptides. Virology 1985, 147, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, P.; Williamson, N.M.; Harlow, E.D. Cellular Targets for Transformation by the Adenovirus E1A Proteins. Cell 1989, 56, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrivia, J.C.; Kwok, R.P.S.; Lamb, N.; Hagiwara, M.; Montminy, M.R.; Goodman, R.H. Phosphorylated CREB Binds Specifically to the Nuclear Protein CBP. Nature 1993, 365, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avantaggiati, M.L.; Carbone, M.; Graessmann, A.; Nakatani, Y.; Howard, B.; Levine, A.S. The SV40 Large T Antigen and Adenovirus E1a Oncoproteins Interact with Distinct Isoforms of the Transcriptional Co-Activator, P300. EMBO J 1996, 15, 2236–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.R. Eukaryotic Transcription Activation: Right on Target. Mol Cell 2005, 18, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Roeder, R.G. The Metazoan Mediator Co-Activator Complex as an Integrative Hub for Transcriptional Regulation. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.L.; Taatjes, D.J. The Mediator Complex: A Central Integrator of Transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merika, M.; Williams, A.J.; Chen, G.; Collins, T.; Thanos, D. Recruitment of CBP/P300 by the IFNβ Enhanceosome Is Required for Synergistic Activation of Transcription. Mol Cell 1998, 1, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, F.; Wienerroither, S.; Stark, A. Combinatorial Function of Transcription Factors and Cofactors. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2017, 43, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholdi, D.; Roelfsema, J.H.; Papadia, F.; Breuning, M.H.; Niedrist, D.; Hennekam, R.C.; Schinzel, A.; Peters, D.J.M. Genetic Heterogeneity in Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome: Delineation of the Phenotype of the First Patients Carrying Mutations in EP300. J Med Genet 2007, 44, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, N.; Acosta, A.M.B.F.; Kohlhase, J.; Bartsch, O. Confirmation of EP300 Gene Mutations as a Rare Cause of Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome. European journal of human genetics 2007, 15, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, R.H.; Dauwerse, H.G.; van Ommen, G.-J.B.; Breuning, M.H. Do Human Chromosomal Bands 16p13 and 22q11-13 Share Ancestral Origins? The American Journal of Human Genetics 1998, 63, 1240–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancy, B.M.; Cole, P.A. Protein Lysine Acetylation by P300/CBP. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 2419–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.E.; Mapp, A.K. Modulating the Masters: Chemical Tools to Dissect CBP and P300 Function. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2018, 45, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delvecchio, M.; Gaucher, J.; Aguilar-Gurrieri, C.; Ortega, E.; Panne, D. Structure of the P300 Catalytic Core and Implications for Chromatin Targeting and HAT Regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013, 20, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Role of Intrinsic Protein Disorder in the Function and Interactions of the Transcriptional Coactivators CREB-Binding Protein (CBP) and P300. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 6714–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Rengachari, S.; Ibrahim, Z.; Hoghoughi, N.; Gaucher, J.; Holehouse, A.S.; Khochbin, S.; Panne, D. Transcription Factor Dimerization Activates the P300 Acetyltransferase. Nature 2018, 562, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Gerona-Navarro, G.; Moshkina, N.; Zhou, M.-M. Structural Basis of Site-Specific Histone Recognition by the Bromodomains of Human Coactivators PCAF and CBP/P300. Structure 2008, 16, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, B.T.; Narita, T.; Satpathy, S.; Srinivasan, B.; Hansen, B.K.; Schölz, C.; Hamilton, W.B.; Zucconi, B.E.; Wang, W.W.; Liu, W.R.; et al. Time-Resolved Analysis Reveals Rapid Dynamics and Broad Scope of the CBP/P300 Acetylome. Cell 2018, 174, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Valor, L.; Viosca, J.; P Lopez-Atalaya, J.; Barco, A. Lysine Acetyltransferases CBP and P300 as Therapeutic Targets in Cognitive and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19, 5051–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.-J.; Seto, E. Lysine Acetylation: Codified Crosstalk with Other Posttranslational Modifications. Mol Cell 2008, 31, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, D.C.; Kasper, L.H.; Fukuyama, T.; Brindle, P.K. Target Gene Context Influences the Transcriptional Requirement for the KAT3 Family of CBP and P300 Histone Acetyltransferases. Epigenetics 2010, 5, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Goto, Y.; Nishimasu, H.; Morimoto, J.; Ishitani, R.; Dohmae, N.; Takeda, N.; Nagai, R.; Komuro, I.; Suga, H.; et al. Structural Basis for Potent Inhibition of SIRT2 Deacetylase by a Macrocyclic Peptide Inducing Dynamic Structural Change. Structure 2014, 22, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penteado, A.B.; Hassanie, H.; Gomes, R.A.; Silva Emery, F. da; Goulart Trossini, G.H. Human Sirtuin 2 Inhibitors, Their Mechanisms and Binding Modes. Future Med Chem 2023, 15, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schemies, J.; Uciechowska, U.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M. NAD+-Dependent Histone Deacetylases (Sirtuins) as Novel Therapeutic Targets. Med Res Rev 2010, 30, 861–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, A.; Fritz, K.S.; Petersen, D.R.; Gius, D. The Human Sirtuin Family: Evolutionary Divergences and Functions. Hum Genomics 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigis, M.C.; Sinclair, D.A. Mammalian Sirtuins: Biological Insights and Disease Relevance. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2010, 5, 253–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, M.; Tian, Y. Trends and Age-Period-Cohort Effects on Incidence and Mortality of Asthma in Sichuan Province, China, 1990–2019. BMC Pulm Med 2022, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Akimoto, K.; Homma, T.; Baker, J.R.; Ito, K.; Barnes, P.J.; Sagara, H. Virus-Induced Asthma Exacerbations: SIRT1 Targeted Approach. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, T.; Mercado, N.; Kunori, Y.; Brightling, C.; Bhavsar, P.K.; Barnes, P.J.; Ito, K. Defective Sirtuin-1 Increases IL-4 Expression through Acetylation of GATA-3 in Patients with Severe Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 137, 1595–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Chen, Q.; Meng, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Ni, Z.; Wang, X. Suppression of Sirtuin-1 Increases IL-6 Expression by Activation of the Akt Pathway during Allergic Asthma. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 43, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Wu, Q.J.; Yang, X.; Xing, X.X.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, H. Effects of SIRT1/Akt Pathway on Chronic Inflammatory Response and Lung Function in Patients with Asthma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 4948–4953. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.G.; Reader, B.F.; Herman, D.; Streicher, A.; Englert, J.A.; Ziegler, M.; Chung, S.; Karpurapu, M.; Park, G.Y.; Christman, J.W.; et al. Sirtuin 2 Enhances Allergic Asthmatic Inflammation. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e124710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-Y.; Hur, G.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Rho, M.-C. AGK2 Ameliorates Mast Cell-Mediated Allergic Airway Inflammation and Fibrosis by Inhibiting FcRI/TGF-β Signaling Pathway. Pharmacol Res 2020, 159, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, J.A. Airway Remodeling in Asthma: Unanswered Questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161, S168–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Shang, Y.-X. Sirtuin 6 Attenuates Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition by Suppressing the TGF-Β1/Smad3 Pathway and c-Jun in Asthma Models. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 82, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, B.D.; Jackson, B.; Marmorstein, R. Structural Basis for Sirtuin Function: What We Know and What We Don’t. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2010, 1804, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, C.H.; Dipp, M.A.; Guarente, L. A Therapeutic Role for Sirtuins in Diseases of Aging? Trends Biochem Sci 2007, 32, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, J.L.; Celic, I.; Muhammad, S.; Cosgrove, M.S.; Boeke, J.D.; Wolberger, C. Structure of a Sir2 Enzyme Bound to an Acetylated P53 Peptide. Mol Cell 2002, 10, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Harshaw, R.; Chai, X.; Marmorstein, R. Structural Basis for Nicotinamide Cleavage and ADP-Ribose Transfer by NAD+-Dependent Sir2 Histone/Protein Deacetylases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 8563–8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalos, J.L.; Boeke, J.D.; Wolberger, C. Structural Basis for the Mechanism and Regulation of Sir2 Enzymes. Mol Cell 2004, 13, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnin, M.S.; Donigian, J.R.; Pavletich, N.P. Structure of the Histone Deacetylase SIRT2. Nat Struct Biol 2001, 8, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, J.; Liao, M.; Hu, M.; Li, W.; Ouyang, H.; Wang, X.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, L. An Overview of Sirtuins as Potential Therapeutic Target: Structure, Function and Modulators. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 161, 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamacina, C.R. The Nicotinamide Dinucleotide Binding Motif: A Comparison of Nucleotide Binding Proteins. The FASEB Journal 1996, 10, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Chattopadhyay, B.D.; Paul, B.N. Epigenetic Regulation of DNMT1 Gene in Mouse Model of Asthma Disease. Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 2357–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, M.G.; Bestor, T.H. Eukaryotic Cytosine Methyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 481–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Blumenthal, R.M. Mammalian DNA Methyltransferases: A Structural Perspective. Structure 2008, 16, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Gao, L.; Song, J. Structural Basis of DNMT1 and DNMT3A-Mediated DNA Methylation. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeltsch, A. On the Enzymatic Properties of Dnmt1: Specificity, Processivity, Mechanism of Linear Diffusion and Allosteric Regulation of the Enzyme. Epigenetics 2006, 1, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.P. Use of Restriction Enzymes to Study Eukaryotic DNA Methylation: II. The Symmetry of Methylated Sites Supports Semi-Conservative Copying of the Methylation Pattern. J Mol Biol 1978, 118, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M.; Bell, D.W.; Haber, D.A.; Li, E. DNA Methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b Are Essential for de Novo Methylation and Mammalian Development. Cell 1999, 99, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M.; Xie, S.; Li, E. Cloning and Characterization of a Family of Novel Mammalian DNA (Cytosine-5) Methyltransferases. Nat Genet 1998, 19, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekesiz, R.T.; Koca, K.K.; Kugu, G.; Çalşkaner, Z.O. Versatile Functions of Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain 2 (MBD2) in Cellular Characteristics and Differentiation. Mol Biol Rep 2025, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; He, Y.; Wasti, B.; Duan, W.; Ouyang, R.; Jia, J.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, D.; et al. MBD2 Mediates Th17 Cell Differentiation by Regulating MINK1 in Th17-Dominant Asthma. Front Genet 2022, 13, 959059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Xiao, B.; Jia, A.; Qiu, L.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, D.; Yuan, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, X. MBD2-Mediated Th17 Differentiation in Severe Asthma Is Associated with Impaired SOCS3 Expression. Exp Cell Res 2018, 371, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.A.; Webb, H.D.; Sinanan, L.M.; Scarsdale, J.N.; Walavalkar, N.M.; Ginder, G.D.; Williams Jr, D.C. An Intrinsically Disordered Region of Methyl-CpG Binding Domain Protein 2 (MBD2) Recruits the Histone Deacetylase Core of the NuRD Complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 3100–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Luu, P.-L.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S.J. Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain Proteins: Readers of the Epigenome. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalşkaner, Z.O. Computational Discovery of Novel Inhibitory Candidates Targeting Versatile Transcriptional Repressor MBD2. J Mol Model 2022, 28, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, C.; Lei, M.; Yang, A.; Loppnau, P.; Hughes, T.R.; Min, J. Structural Basis for the Ability of MBD Domains to Bind Methyl-CG and TG Sites in DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 7344–7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Luu, P.-L.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S.J. Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain Proteins: Readers of the Epigenome. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, I.; Shimotake, N.; Fujita, N.; Jee, J.-G.; Ikegami, T.; Nakao, M.; Shirakawa, M. Solution Structure of the Methyl-CpG Binding Domain of Human MBD1 in Complex with Methylated DNA. Cell 2001, 105, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, K.H.; Zhou, Z. Emerging Molecular and Biological Functions of MBD2, a Reader of DNA Methylation. Front Genet 2016, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesian, S.; Yousefi, A.-M.; Momeny, M.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Bashash, D. The DNA Methylation in Neurological Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.Y.S.; Shang, Y.; Limjunyawong, N.; Dao, T.; Das, S.; Rabold, R.; Sham, J.S.K.; Mitzner, W.; Tang, W.-Y. Alterations of the Lung Methylome in Allergic Airway Hyper-Responsiveness. Environ Mol Mutagen 2014, 55, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, L.M.; Tahiliani, M.; Rao, A.; Aravind, L. Prediction of Novel Families of Enzymes Involved in Oxidative and Other Complex Modifications of Bases in Nucleic Acids. Cell cycle 2009, 8, 1698–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, W.A.; Aravind, L.; Rao, A. TETonic Shift: Biological Roles of TET Proteins in DNA Demethylation and Transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Christensen, J.; Helin, K. DNA Methylation: TET Proteins—Guardians of CpG Islands? EMBO Rep 2012, 13, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Rao, Q.; Gong, W.; Liu, M.; Shi, Y.G.; Zhu, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, Y. Crystal Structure of TET2-DNA Complex: Insight into TET-Mediated 5mC Oxidation. Cell 2013, 155, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Gao, Y.; Gan, K.; Wu, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M. Prognostic Roles of N6-Methyladenosine METTL3 in Different Cancers: A System Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancer Control 2021, 28, 1073274821997455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweaad, W.K.; Stefanizzi, F.M.; Chamorro-Jorganes, A.; Devaux, Y.; Emanueli, C. ; others Relevance of N6-Methyladenosine Regulators for Transcriptome: Implications for Development and the Cardiovascular System. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021, 160, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncel, G.; Kalkan, R. Importance of m N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) RNA Modification in Cancer. Medical Oncology 2019, 36, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhou, L.; Yan, C.; Li, L. Emerging Role of N6-Methyladenosine RNA Methylation in Lung Diseases. Exp Biol Med 2022, 247, 1862–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, Y.; Shang, J.; Ji, W. ALKBH5-M6A-FOXM1 Signaling Axis Promotes Proliferation and Invasion of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells under Intermittent Hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020, 521, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.-M.; Jang, S.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, T.-D.; Kim, V.N. RNA Demethylation by FTO Stabilizes the FOXJ1 MRNA for Proper Motile Ciliogenesis. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-X.; Yan, W.; Liu, J.-P.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Chen, L. Long Noncoding RNA SNHG4 Remits Lipopolysaccharide-Engendered Inflammatory Lung Damage by Inhibiting METTL3–Mediated M6A Level of STAT2 MRNA. Mol Immunol 2021, 139, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Sun, G.; Sun, J.; Wu, D. The Effect of N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Factors on the Development of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in the Mouse Model. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 7622–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Zhao, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, W. Importance of N6-Methyladenosine RNA Modification in Lung Cancer. Mol Clin Oncol 2021, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, X.-F.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Yin, S.-Q.; Huang, C.; Li, J. N6-Methyladenosine and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comprehensive Review. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 731842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Tang, W.; Wuniqiemu, T.; Qin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, X.; Tang, Z.; Yi, L.; et al. N 6-Methyladenosine Methylomic Landscape of Lung Tissues in Murine Acute Allergic Asthma. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 740571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wei, L.; Law, C.-T.; Tsang, F.H.-C.; Shen, J.; Cheng, C.L.-H.; Tsang, L.-H.; Ho, D.W.-H.; Chiu, D.K.-C.; Lee, J.M.-F.; et al. RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase-like 3 Promotes Liver Cancer Progression through YTHDF2-Dependent Posttranscriptional Silencing of SOCS2. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2254–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, B.S.; Ma, H.; Hsu, P.J.; Liu, C.; He, C. YTHDF3 Facilitates Translation and Decay of N6-Methyladenosine-Modified RNA. Cell Res 2017, 27, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Yu, Y.; Ding, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Wei, D.; Ye, Q.; Wang, F.; et al. YTHDF1 Regulates Pulmonary Hypertension through Translational Control of MAGED1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 203, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Qi, Y.; Yu, J.; Hao, Y.; He, B.; Zhang, M.; Dai, Z.; Jiang, T.; Li, S.; Huang, F.; et al. Nuclear Aurora Kinase A Switches M6A Reader YTHDC1 to Enhance an Oncogenic RNA Splicing of Tumor Suppressor RBM4. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wei, Q.; Jin, J.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Li, L.; Pi, J.; Si, Y.; et al. The M6A Reader YTHDF1 Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression via Augmenting EIF3C Translation. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 3816–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Wu, C.; Gao, Y.; Qian, Y.; Hou, J.; Xie, R.; Han, B.; Chen, Z.; Wei, S.; et al. Adipocyte YTH N (6)-Methyladenosine RNA-Binding Protein 1 Protects against Obesity by Promoting White Adipose Tissue Beiging in Male Mice. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Teng, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Luo, X.; Liao, Y.; Yang, B. YTHDF1 Negatively Regulates Treponema Pallidum-Induced Inflammation in THP-1 Macrophages by Promoting SOCS3 Translation in an M6A-Dependent Manner. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 857727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hou, W.; Liu, F.; Zhu, R.; Lv, A.; Quan, W.; Mao, S. Blockade of NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β Regulated Th17/Treg Immune Imbalance and Attenuated the Neutrophilic Airway Inflammation in an Ovalbumin-Induced Murine Model of Asthma. J Immunol Res 2022, 2022, 9444227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Cheng, D.; Shi, C.; Shen, Z. The Protective Role of YTHDF1-Knock down Macrophages on the Immune Paralysis of Severe Sepsis Rats with ECMO. Microvasc Res 2021, 137, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Huang, B.; Lei, L.; Luo, S. Cetirizine Inhibits Activation of JAK2-STAT3 Pathway and Mast Cell Activation in Lung Tissue of Asthmatic Mice. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 38, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liao, G.; Chen, B.; Panettieri, R.A.; Penn, R.B.; Tang, D.D. Abi1 Mediates Airway Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Airway Remodeling via Jak2/STAT3 Signaling. iScience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, W.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Q.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; et al. α-Asarone Alleviates Allergic Asthma by Stabilizing Mast Cells through Inhibition of ERK/JAK2-STAT3 Pathway. Biofactors 2023, 49, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milara, J.; Ballester, B.; de Diego, A.; Calbet, M.; Ramis, I.; Miralpeix, M.; Cortijo, J. The Pan-JAK Inhibitor LAS194046 Reduces Neutrophil Activation from Severe Asthma and COPD Patients in Vitro. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Tian, X.; Luo, L. N6-Methyladenosine Reader YTHDF1 Regulates the Proliferation and Migration of Airway Smooth Muscle Cells through M6A/Cyclin D1 in Asthma. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Yang, H.; Fan, L.; Shen, F.; Wang, Z. M6A Regulator-Mediated RNA Methylation Modification Patterns and Immune Microenvironment Infiltration Characterization in Severe Asthma. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 10236–10247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the Human and Mouse M6A RNA Methylomes Revealed by M6A-Seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N 6-Methyladenosine-Dependent Regulation of Messenger RNA Stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bedi, R.K.; Wiedmer, L.; Huang, D.; Śledź, P.; Caflisch, A. Flexible Binding of M6A Reader Protein YTHDC1 to Its Preferred RNA Motif. J Chem Theory Comput 2019, 15, 7004–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, R.K.; Huang, D.; Wiedmer, L.; Li, Y.; Dolbois, A.; Wojdyla, J.A.; Sharpe, M.E.; Caflisch, A.; Sledz, P. Selectively Disrupting M6A-Dependent Protein–RNA Interactions with Fragments. ACS Chem Biol 2020, 15, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, K.; Ahmed, H.; Loppnau, P.; Schapira, M.; Min, J. Structural Basis for the Discriminative Recognition of N6-Methyladenosine RNA by the Human YT521-B Homology Domain Family of Proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 24902–24913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bedi, R.K.; Moroz-Omori, E. V; Caflisch, A. Structural and Dynamic Insights into Redundant Function of YTHDF Proteins. J Chem Inf Model 2020, 60, 5932–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.P.; Pickering, B.F.; Jaffrey, S.R. Reading M6A in the Transcriptome: M6A-Binding Proteins. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, D.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y. Structure of the YTH Domain of Human YTHDF2 in Complex with an M6A Mononucleotide Reveals an Aromatic Cage for M6A Recognition. Cell Res 2014, 24, 1490–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Ž\’\idek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nai, F.; Nachawati, R.; Zalesak, F.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Caflisch, A. Fragment Ligands of the M6A-RNA Reader YTHDF2. ACS Med Chem Lett 2022, 13, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The Proteomics Server for in-Depth Protein Knowledge and Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Roundtree, I.A.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, C.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; He, C.; Xu, Y. Crystal Structure of the YTH Domain of YTHDF2 Reveals Mechanism for Recognition of N6-Methyladenosine. Cell Res 2014, 24, 1493–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Liu, K.; Zeng, L.; Huang, J.; Pan, L.; Li, M.; Bai, R.; Zhuang, L.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine–Mediated Upregulation of WTAPP1 Promotes WTAP Translation and Wnt Signaling to Facilitate Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 5268–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sheng, H.; Ma, F.; Wu, Q.; Huang, J.; Chen, Q.; Sheng, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Xu, M. RNA M6A Reader YTHDF2 Facilitates Lung Adenocarcinoma Cell Proliferation and Metastasis by Targeting the AXIN1/Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Xu, C.; Lu, M.; Wu, X.; Tang, L.; Wu, X. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Links Embryonic Lung Development and Asthmatic Airway Remodeling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2017, 1863, 3226–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Ni, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhong, J.; Nie, H. Cross-Talk of Four Types of RNA Modification Writers Defines the Immune Microenvironment in Severe Asthma. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2022, 1514, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, R.; Ling, T.; Liu, B.; Huang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H.; Xie, X.; Xia, G.; et al. Elevated WTAP Promotes Hyperinflammation by Increasing m 6 A Modification in Inflammatory Disease Models. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, N.A.; Hastie, N.D.; Davies, R.C. Identification of WTAP, a Novel Wilms’ Tumour 1-Associating Protein. Hum Mol Genet 2000, 9, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, T.W.; Penalva, L.O.; Pickering, J.G. Vascular Biology and the Sex of Flies: Regulation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation by Wilms’ Tumor 1–Associating Protein. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2007, 17, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöller, E.V.A.; Weichmann, F.; Treiber, T.; Ringle, S.; Treiber, N.; Flatley, A.; Feederle, R.; Bruckmann, A.; Meister, G. Interactions, Localization, and Phosphorylation of the M6A Generating METTL3–METTL14–WTAP Complex. Rna 2018, 24, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, K.; Kawamura, T.; Iwanari, H.; Ohashi, R.; Naito, M.; Kodama, T.; Hamakubo, T. Identification of Wilms’ Tumor 1-Associating Protein Complex and Its Role in Alternative Splicing and the Cell Cycle. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 33292–33302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, X.-L.; Sun, B.-F.; Wang, L.U.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.-J.; Adhikari, S.; Shi, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; et al. Mammalian WTAP Is a Regulatory Subunit of the RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase. Cell Res 2014, 24, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Pei, K.; Guan, Z.; Liu, F.; Yan, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, Q.; Hou, M.; Tang, C.; Yin, P. AI-Empowered Integrative Structural Characterization of M6A Methyltransferase Complex. Cell Res 2022, 32, 1124–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3–METTL14 Complex Mediates Mammalian Nuclear RNA N 6-Adenosine Methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hu, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, L. Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) Epigenetically Modulates Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4) Expression to Affect Asthma. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023, 22, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Tian, Q.; Feng, D.; Zhuang, L.; Cao, Q.; Zhou, G.; Jin, R. ETS1 and RBPJ Transcriptionally Regulate METTL14 to Suppress TGF-Β1-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2024, 1870, 167349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Li, X.; Hu, B.; Wang, L. Chronic Allergic Asthma Alters M6A Epitranscriptomic Tagging of MRNAs and LncRNAs in the Lung. Biosci Rep 2022, 42, BSR20221395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Liu, S.; Xu, W. Microenvironment Modulation by Key Regulators of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Modification in Respiratory Allergic Diseases. BMC Pulm Med 2023, 23, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Toth, J.I.; Petroski, M.D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.C. N 6-Methyladenosine Modification Destabilizes Developmental Regulators in Embryonic Stem Cells. Nat Cell Biol 2014, 16, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3–METTL14 Complex Mediates Mammalian Nuclear RNA N 6-Adenosine Methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, L.M.; Zhang, D.; Aravind, L. Adenine Methylation in Eukaryotes: Apprehending the Complex Evolutionary History and Functional Potential of an Epigenetic Modification. Bioessays 2016, 38, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.; Mumbach, M.R.; Jovanovic, M.; Wang, T.; Maciag, K.; Bushkin, G.G.; Mertins, P.; Ter-Ovanesyan, D.; Habib, N.; Cacchiarelli, D.; et al. Perturbation of M6A Writers Reveals Two Distinct Classes of MRNA Methylation at Internal and 5′ Sites. Cell Rep 2014, 8, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledź, P.; Jinek, M. Structural Insights into the Molecular Mechanism of the M6A Writer Complex. Elife 2016, 5, e18434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dong, X.; Gong, Z.; Qin, L.-Y.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zou, T.; Yin, P.; et al. Solution Structure of the RNA Recognition Domain of METTL3-METTL14 N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Doxtader, K.A.; Nam, Y. Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol Cell 2016, 63, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Oyoshi, T.; Suda, A.; Futaki, S.; Imanishi, M. Recognition of G-Quadruplex RNA by a Crucial RNA Methyltransferase Component, METTL14. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbeski, I.; Vargas-Rosales, P.A.; Bedi, R.K.; Deng, J.; Coelho, D.; Braud, E.; Iannazzo, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, D.; Ethève-Quelquejeu, M.; et al. The Catalytic Mechanism of the RNA Methyltransferase METTL3. Elife 2024, 12, RP92537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerum, S.; Meynier, V.; Catala, M.; Tisné, C. A Comprehensive Review of M6A/M6Am RNA Methyltransferase Structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breger, K.; Kunkler, C.N.; O’Leary, N.J.; Hulewicz, J.P.; Brown, J.A. Ghost Authors Revealed: The Structure and Function of Human N 6-Methyladenosine RNA Methyltransferases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2024, 15, e1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N 6-Methyladenosine by IGF2BP Proteins Enhances MRNA Stability and Translation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Rapley, J.; Angel, M.; Yanik, M.F.; Blower, M.D.; Avruch, J. MTOR Phosphorylates IMP2 to Promote IGF2 MRNA Translation by Internal Ribosomal Entry. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhar, M.; Gul, M.; Li, W. Interactive Structural Analysis of KH3-4 Didomains of IGF2BPs with Preferred RNA Motif Having m6A through Dynamics Simulation Studies 2024.

- Lian, Z.; Chen, R.; Xian, M.; Huang, P.; Xu, J.; Xiao, X.; Ning, X.; Zhao, J.; Xie, J.; Duan, J.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of M6A Demethylase FTO by FB23 Attenuates Allergic Inflammation in the Airway Epithelium. The FASEB Journal 2024, 38, e23846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G.; Yang, C.-G.; Yang, S.; Jian, X.; Yi, C.; Zhou, Z.; He, C. Oxidative Demethylation of 3-Methylthymine and 3-Methyluracil in Single-Stranded DNA and RNA by Mouse and Human FTO. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 3313–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, J.D.W.; Sun, L.; Lau, L.Z.M.; Tan, J.; Low, J.J.A.; Tang, C.W.Q.; Cheong, E.J.Y.; Tan, M.J.H.; Chen, Y.; Hong, W.; et al. A Strategy Based on Nucleotide Specificity Leads to a Subfamily-Selective and Cell-Active Inhibitor of N 6-Methyladenosine Demethylase FTO. Chem Sci 2015, 6, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Xiao, W.; Ju, D.; Sun, B.; Hou, N.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Identification of Entacapone as a Chemical Inhibitor of FTO Mediating Metabolic Regulation through FOXO1. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11, eaau7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Niu, T.; Chang, J.; Lei, X.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Chai, J. Crystal Structure of the FTO Protein Reveals Basis for Its Substrate Specificity. Nature 2010, 464, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.-H.; Rao, G.-W.; Gan, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. Structure–Activity Relationships and Antileukemia Effects of the Tricyclic Benzoic Acid FTO Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 10638–10654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishodia, S.; Demetriades, M.; Zhang, D.; Tam, N.Y.; Maheswaran, P.; Clunie-O’Connor, C.; Tumber, A.; Leung, I.K.H.; Ng, Y.M.; Leissing, T.M.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Selective Fat Mass and Obesity Associated Protein (FTO) Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 16609–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, L.-H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yan, N.; Amu, G.; Tang, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structural Insights into FTO’s Catalytic Mechanism for the Demethylation of Multiple RNA Substrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 2919–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modification Type | Role | Examples | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification | Writer | p300/CBP | p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases that, with increased expression in asthma, likely activate pro-inflammatory genes, contributing to chronic airway inflammation. | [29] |

| Gcn5 | H3K27 acetylation via HAT Gcn5 plays a key role in the histone code, with strong associations to asthma through its regulatory impact. | [30,31] | ||

| KAT2A | KAT2A plays a crucial role in acetylating lysine 18 on histone 3, a modification that is found to be elevated in the epithelial cells of individuals with asthma | [32] | ||

| SMYD3 | In asthma, SMYD3 is upregulated in airway fibroblasts, affecting cell cycle regulation through histone methylation. However, its protein-level impact remains unclear, indicating possible additional transcriptional control layers | [33,34] | ||

| Eraser | HDAC1 | HDAC1 was significantly increased in bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) of asthmatic patients | [35] | |

| HDAC2 | Patients with mild asthma exhibit a slight decrease in HDAC2 activity in bronchial biopsies and alveolar macrophages | [36] | ||

| HDAC3 | HDAC3 regulates NF-κB activity in asthma by deacetylating specific lysine residues, suppressing inflammation. HDAC3 deficiency in macrophages reduces inflammatory gene expression, underscoring its role in controlling asthma-related inflammation. | [37] | ||

| SIRT1 | Both protective and deleterious roles in asthma | [38] | ||

| SIRT2 | SIRT2 exacerbates asthma-associated inflammation by driving Th2 cell responses and macrophage polarization. | [39] | ||

| SIRT3 | Song et al. found that decreased Sirt3 expression in asthmatic mice contributes to increased apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. | [40] | ||

| SIRT6 | Jiang et al. found that Sirt6 is upregulated in asthmatic mice | [41] | ||

| SIRT7 | Fang et al. found that increased SIRT7 expression in airway smooth muscle cells regulates TGF-β1-induced cell proliferation and migration, highlighting its role in asthmatic airway remodeling. | [42] | ||

| DNA modification | Writer | DNMT1 | DNMT1 maintains DNA methylation patterns, and reduced levels are associated with increased Socs3 expression, promoting inflammation in asthma | [43] |

| DNMT3a | Dnmt3a regulates Th2 responses by modulating IL-13 gene methylation; loss of Dnmt3a decreases methylation, enhancing IL-13 expression and asthma-associated lung inflammation | [44] | ||

| Reader | MBD2 | MBD2 is an epigenetic reader protein recognizing methylated CpG sites, suppressing SOCS3 expression, and promoting Th17 cell differentiation. Elevated MBD2 drives neutrophilic inflammation, contributing to severe asthma. | [45] | |

| Eraser | TET1 | Reduced TET1 promoter methylation (cg23602092) in nasal cells correlates with childhood asthma and traffic-related air pollution, altering TET1 expression and 5hmC.TET1 modulates DNA methylation and epigenetic regulation in asthma. | [46] | |

| RNA modification | Writer | WTAP | WTAP was demonstrated to be abnormally expressed in asthma patients.WTAP knockdown relieves asthma progression by regulating the m6A levels of AXIN1 in a YTHDF2-dependent manner. | [47,48] |

| METTL3 | METTL3 regulates Th2 cell differentiation in T2 asthma by modulating SOX5 m6A methylation in bronchial epithelial cells. This mechanism may offer a potential target for preventing and managing T2 asthma. | [49] | ||

| Reader | YTHDF1 | YTHDF1, highly expressed in airway epithelial cells of allergic and asthmatic individuals, enhances CLOCK translation in an m6A-dependent manner. This triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion, promoting inflammatory responses in the airways | [50] | |

| YTHDF2 | m6A-YTHDF2 regulates macrophage polarization by inhibiting M1 and promoting M2 phenotypes through NF-κB, MAPK, and STAT pathways, playing a key role in asthma subtypes and targeted therapy. | [51] | ||

| IGF2BP2 | IGF2BP2 promotes asthma by stabilizing Tsc1 mRNA, which helps macrophages adopt the M2 phenotype | [52] | ||

| Eraser | FTO | FTO plays a pivotal role as an eraser of m6A modifications in asthma by regulating the stability of mRNA transcripts such as IKBKB, leading to the activation of the NF-κB pathway and contributing to inflammation and epithelial barrier dysfunction. | [53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).