Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematological cancer derived from plasma cells, often defined by the presence of a monoclonal immunoglobulin. It accounts for 1% of cancers and about 10% of hematological malignancies. And findings during the course of the disease may include anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, renal failure, severe pain, bone fractures and hypercalcemia [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, almost all multiple myelomas arise from asymptomatic premalignant condition called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). This is diagnosed after more than 10 years of the disorder in 50% [

5,

6,

7]. Effective multi-drug regimens are available for most forms of MM, resulting in long-term remission. However, because of the disease’s biology, relapse remains frequent, and MM remains incurable due to the emergence of treatment resistance [

8,

9,

10]. MM has variable clinical findings, nonspecific symptoms as seen in diabetes, arthritis, or chronic renal failure all can lead to diagnosis late [

11], especially in elderly patients there are many differential diagnoses mimicking MM. Patients often develop these symptoms and present to primary healthcare providers or other specialties giving rise to delays in referrals to hematologists. Delayed diagnosis of the disease can negatively impact on patients’ quality of life and prognosis [

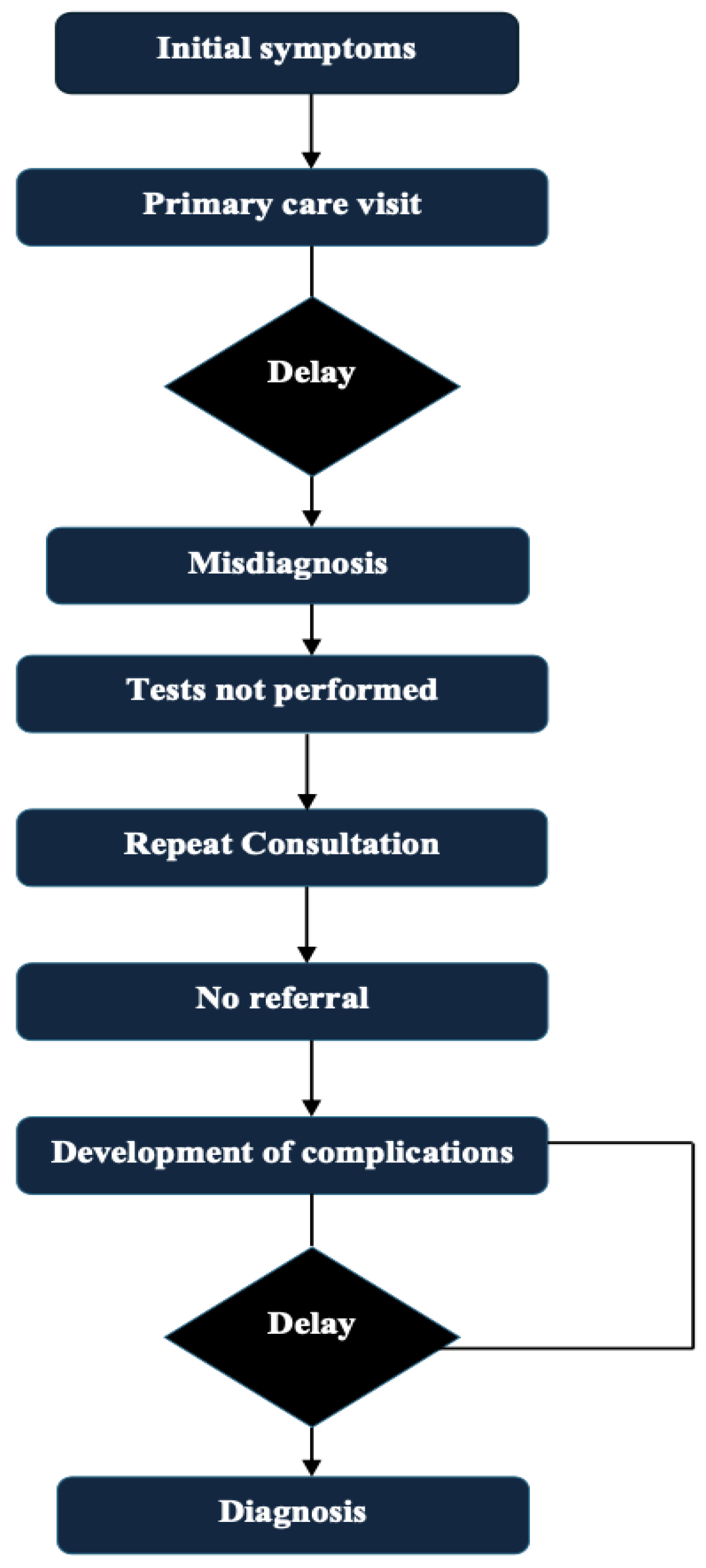

12]. The routine path to diagnosis of multiple myeloma and possible delays is presented in

Figure 1. Existing reviews and articles on this topic are sparse. The objective of this review is to present and evaluate the multifactorial factors which create and perpetuate delays in the diagnoses of multiple myeloma, highlight barriers that exist at the patient, physician, and system perspective level, present potential strategies which may facilitate earlier diagnoses and earlier interventions, and provide supplemental data to fill gaps in the existing literature to foster academic progress in this area.

Clinical Spectrum of Multiple Myeloma

The symptoms in multiple myeloma is usually nonspecific. Its defining symptoms are the CRAB symptoms (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, bone findings) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among 1027 multiple myeloma patients included in the Czech post marketing observational study, bone pain was reported at diagnosis by 58% of the patients and fatigue by 32% of the patients. Seventy-three percent of the patients had anemia, 48% had elevated creatinine levels, 13% had hypercalcemia and 79% had bone abnormalities (primarily but not limited to lytic lesions, fractures and osteoporosis). Other features typically noted are neuropathy, developing infections (recurrent), loss of weight (involuntary), easy bruising/bleeding [

13].

Because most symptoms are nonspecific, they can resemble many other conditions. Diabetes shares some symptoms with multiple myeloma, including excessive thirst and urination, fatigue, frequent infections, and neuropathy [

14]. Likewise, renal sufficiency due to multiple myeloma is difficult to separate from renal insufficiency from diabetes or chronic kidney disease in the absence of directed testing [

15]. Bone pain or low back pain is frequently shrugged off as arthritis or osteoporosis and not taken seriously. This results in delayed diagnosis, which consequently leads to increased morbidity and mortality [

16]. Presenting symptoms for multiple myeloma Although the most frequent presenting clinical symptoms for multiple myeloma, along with potential misunderstandings and diagnostic delays are outlined in

Table 1.

It has been shown that patients consult at least three specialists before arriving at a hematologist, which can cause a lapse of 3 to 6 months in the diagnostic workup [

17]. Delayed diagnosis is linked with a higher rate of myeloma-related complications and a significant decrease in disease-free survival, but does not affect the overall survival rate [

18]. Worse outcomes have been associated also with presenting with advanced complications (eg, severe infections, spinal cord compression, fractures, renal failure) [

19].

Reasons for Delays in Diagnosis

Tests and Limitations in the Diagnostic Process

Given that the diagnosis of MM is often made late in the course of the disease process, it is imperative that primary care physicians begin the diagnostic algorithm when they observe any of the aforementioned symptoms (eg, fatigue, weight loss) or abnormalities on routine laboratory testing (eg, anemia, elevated creatinine, hypercalcemia, elevated ESR, or elevated total protein levels [

37]. In this setting, relatively simple and directed tests like serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), serum free light chain (sFLC) testing, and serum immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) should be the first tests requested [

38,

39]. At this stage of imaging, a low-dose CT whole-body scan, if available, is to be preferred due to its sensibility in the detection of osteolytic lesions. What alternative methods can be used not covered by CT are advanced ones like PET-CT or MRI and the request for these tests is usually made by a hematologist or an oncologist [

40]. Hence, early referral of suspected cases with necessary lab tests from primary care to hematology aids in quicker diagnosis and avoids complications [

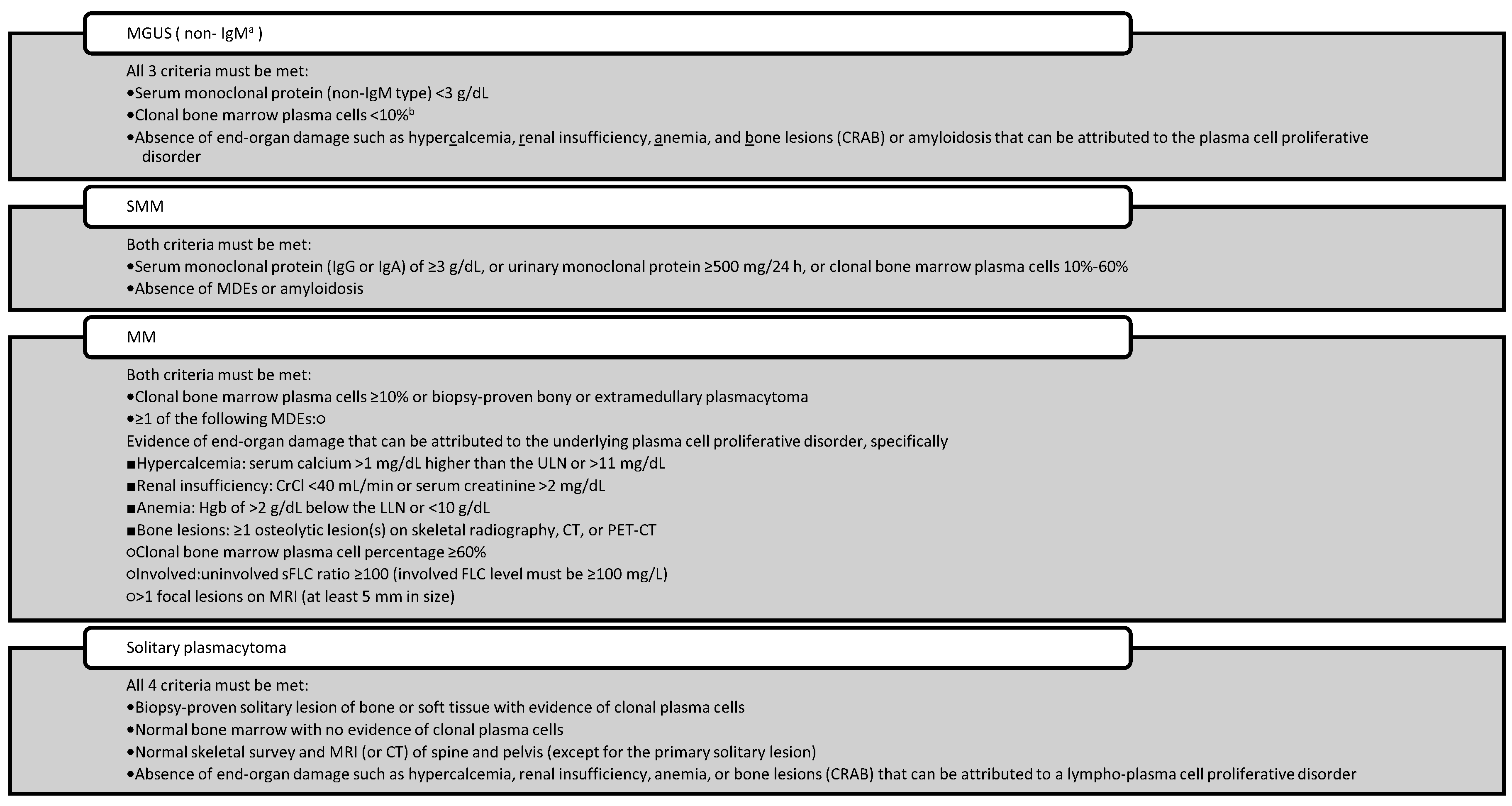

40]. Widespread implementation of diagnostic algorithms in primary care, better awareness among general practitioners and establishing rapid referral chains are required to prevent delays. The diagnosis is then made according to the International Myeloma Working Group Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Myeloma and Certain Related Plasma Cell Disorders [

41], once a hematologist has completed the workup.

Table 4.

International Myeloma Working Group Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Myeloma and Certain Related Plasma Cell Disorders.

Table 4.

International Myeloma Working Group Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Myeloma and Certain Related Plasma Cell Disorders.

Laboratory and Imaging Methods Used in the Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma

Laboratory and imaging diagnostic techniques for multiple myeloma report varying sensitivity and specificity for the identification of unique subtypes because of the biological heterogeneity of the disease [

42]. Although serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation tests are the most common techniques to identify monoclonal immunoglobulins, they are known to have low sensitivity, especially in light chain-only (LCO) or non-secretory myeloma [

38,

43]. In these subgroups, the serum free light chain (sFLC) test is of clear diagnostic utility, indirectly providing evidence of monoclonality due to alterations in the kappa and lambda ratio [

44]. However approximately 20% of LCO patients have non-elevated FLC that cannot be reliably identified in urine thus limiting utility both in diagnosis and treatment response assessment while above 100 mg/L offers a significant gain in reliability [

45].

However, many advanced diagnostic methods are unavailable in all healthcare facilities. Technologies such as mass spectrometry and isoelectric focusing that are more sensitive, are still not routinely used, and are only available to a handful of centers due to the expense and infrastructure and personnel required. For imaging, techniques such as low-dose whole-body CT, PET-CT, and whole-body MRI are essential for the early detection of osteolytic lesions but often rely on hematologist/oncologist referrals [

46]. Moreover, advanced radiological experience is needed for the interpretation of these tests and risks, like interpretational variability, or false negatives can add to the challenge in diagnosis [

47].

Table 5 Summary of the main diagnostic techniques for MM and of their sensitivity and specificity and limitations.

In addition, traditional methodologies like Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization analysis can detect high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities but cannot provide a complete picture of molecular heterogeneity in multiple myeloma at the molecular level [

48]. Next-generation sequencing technologies (whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing) overlap the ability to probe more deeply into the genetic infrastructure of the disease, but these techniques have not yet gained broad translation into clinical practice due to barriers of cost, interpretation of data, and a lack of infrastructure; thus, are limited in the application to the vast majority of MM patients. Collectively, these factors represent major technical and systematic obstacles towards accurate, rapid, and subtype specific diagnosis of multiple myeloma [

49]. New diagnostics in MM The last years have also seen the emergence of new biomarkers and technology for improvement in earlier and more accurate diagnosis of MM as shown in

Table 6. Although widely used, many of these diagnostic tests have deficiencies with regard to sensitivity, specificity, or application, as listed in

Table 7.

Consequences of Delayed Diagnosis

These challenges result in patients being diagnosed later, receiving treatment more slowly and experiencing worse clinical outcomes [

50]. Late identification raises the risk of potentially fatal issues in patients [

50]. This results in increased morbidity and early mortality, leading to more aggressive initial treatments, which drives up costs [

51]. Those who present with renal failure at diagnosis have limited therapeutic options and those who present with vertebrae fractures have limited mobility, chronic pain, and reduced quality of life [

52]. Moreover, the higher demand for treatment associated with late-stage disease manifests as an increased number of patients requiring hospitalization, intensive care and impact on the healthcare system, which, in turn, has economic implications [

53]. Delay in diagnosis also leads to more long-term problems including lower treatment compliance, lower quality of life, loss in workforce productivity and psychosocial effects [

54]. Hence, early diagnosis of the disease not only has clinical but also economic and social significance in multiple myeloma [

55].

Table 8 Clinical and prognostic implications of delayed diagnosis in multiple myeloma

Strategies to Prevent Diagnostic Delays

Diagnostic interval in multiple myeloma is one of the longest in all types of cancer that adversely affect both patient outcomes and a burden on the healthcare system [

56]. Such delays often occur in primary care, since general practitioners (GPs) are rarely seeing this rare disease clinically [

57]. Moreover, an average GP will see multiple myeloma only once every 8–10 years, making it very unlikely to be suspected early on [

58]. Hence, the enhancement of GPs familiarity with myeloma symptomatology and diagnostic pathways as well as the implementation of diagnostic safety nets for persistent and unexplained symptoms remains a key strategic priority [

59].

Early diagnosis may easily be established through the recognition of minor abnormalities in routine blood tests, along with the implementation of reflex myeloma screening [

60]. Clinical risk algorithms created for this approach seek to identify high-risk patients based on their electronic health records, utilizing parameters including symptoms, hemoglobin, creatinine, and inflammatory markers [

61] There are technical challenges that still exist with it being integrated into decision support systems, including, alignment with clinical workflows, and figuring out triggering thresholds. Active surveillance of precursor conditions such as MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is also critically important [

62]. A population-based screening study conducted in Iceland provides one valuable model, during which all MGUS patients were studied, applying different follow-up strategies [

63].

In addition, work with laboratories on early warning systems and proactive collaboration with hematologists can help facilitate diagnoses, particularly in less obvious cases. To facilitate timely referral decisions, critical test results must be interpreted according to pre-defined algorithms and communicated to the clinician with the correct reflex tests [

64]. In addition to their reliance on technological integration, cost-effectiveness, sustainability of their impact on the healthcare system, and diagnostic accuracy must be used to assess early diagnostic strategies. This approach can enhance the early detection of myeloma at a much earlier stage with minimal complications and improve basic clinical end-points, such as survival [

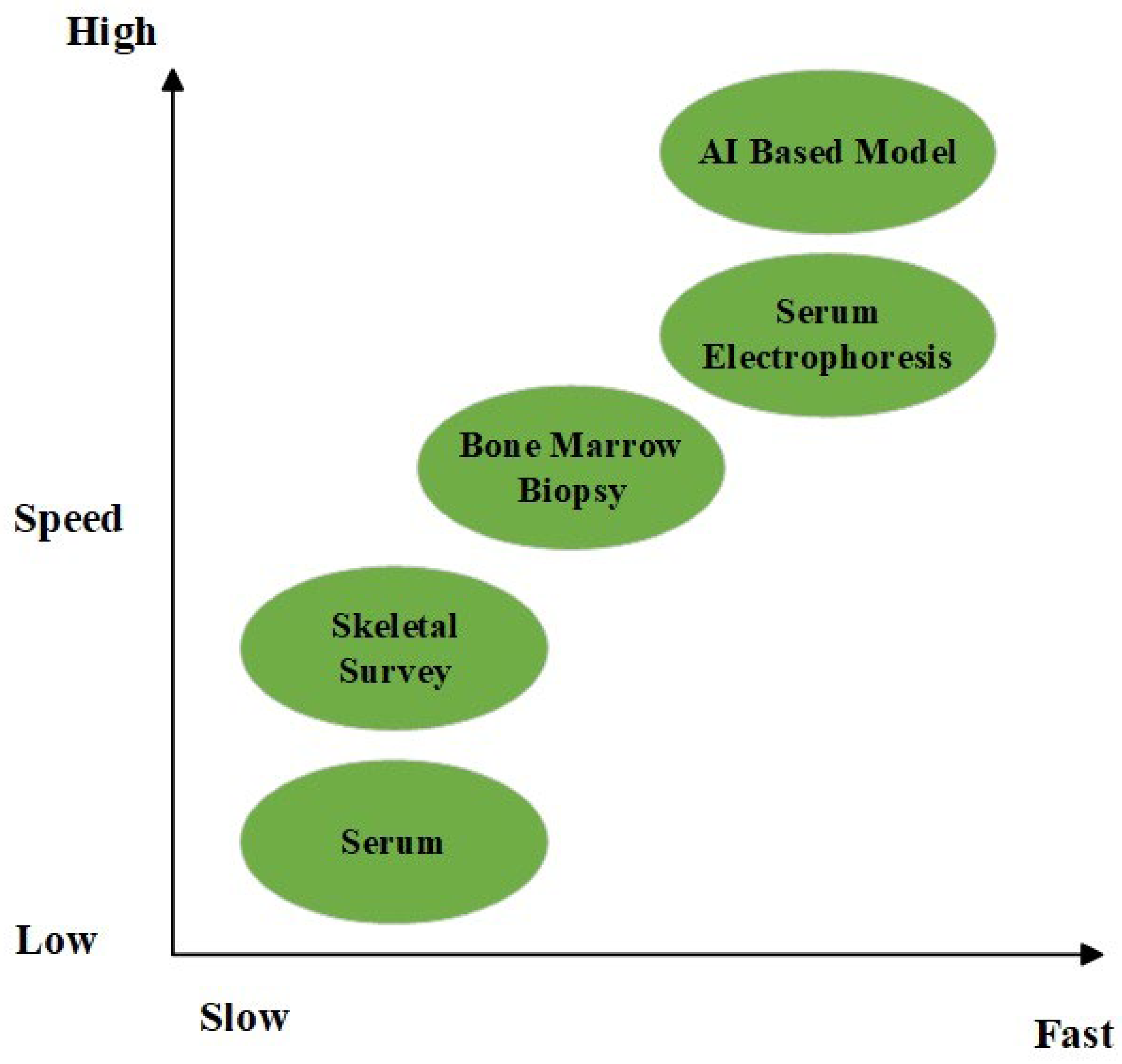

65]. A graphic comparison of two chosen diagnostic tools according to their speed and sensitivity is presented in

Figure 2.

Future Perspectives and Research Areas

Sufficient studies on enhanced diagnostic and prognostic markers are ongoing due to the rising incidence of multiple myeloma (MM) cases and the burdens and delay in diagnosis [

66]. MiRNAs, angiogenic factors, Extracellular Matrix proteins, telomeres and telomerase activities are newer biomarkers with promising capabilities in the diagnostics and prognostics of MM [

67]. Ongoing studies on methodologies such as blood/liquid biopsy, which could permit earlier disease detection than the still gold-standard invasive bone marrow biopsy but still allow more frequent and less painful measurements through the variants in circulating tumor cells (CTCs), miRNAs and cell freely circulating DNA (cfDNA) in peripheral circulation [

68].

As with other sectors, there is growing use of artificial intelligence in medicine. As the number of cases of multiple myeloma increases so does the volume of data that has been gathered [

69]. Such data can be processing using machine learning and deep learning models to expand the knowledge and better understand myeloma mechanisms to better manage MM patients [

70,

71].

MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) is prolonged premalignant phase prior to the development of multiple myeloma [

72]. This phase allows to study cancer evolution and to understand plasma cell neoplasm malignant evolution mechanisms, identify MGUS patients with high-risk of progression early and eventually design new therapeutic targets considering previous achievements. This may also delay or extend the process of malignant transformation [

73,

75].

The application of rapid advances in genomic techniques to study how premalignant cells evolve should also allow for the identification and subsequent targeting of driver events during clonal evolution in MM and in cancer more broadly [

74,

75].

Conclusion

Multiple myeloma is the second most common hematological malignancy, but late diagnosis of the disease is commonly reported due to non-specific symptoms, lack of awareness, and patient-, physician-, and system-related factors. We would like to remind that the majority of cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage of the disease, which, in turn, increases morbidity and reduces the quality of life. The microbiological, serological, and imaging techniques related to the diagnostic process have made significant progress but face challenges for widespread adoption and standardized implementation.

This opens up several avenues for early diagnosis including raising awareness through educational programs, algorithm development for primary healthcare centers, adoption of state-of-the-art technologies like AI and big data analytics, and genomic research specifically on the MGUS premalignant phase. Therefore, removing obstacles to early diagnosis and treatment initiation at an earlier stage can effectively reduce the morbidity and early mortality and has been associated with statistically significant improvements in patient survival and quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.Z., M.A.K., N.O., T.U., M.S.D., FA; Methodology: T.Z., M.A.K., N.O., T.U., M.S.D., FA; Writing—original draft preparation, T.Z., M.A.K., N.O., T.U., M.S.D., FA; writing—review and editing, T.Z., M.A.K., N.O., T.U., M.S.D., FA; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

References

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2020; 95(5): 548-567. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25791. Erratum in: Am J Hematol. 2020; 95(11): 1444. [CrossRef]

- Malard F, Neri P, Bahlis NJ, Terpos E, et al.Multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024; 10(1): 45. [CrossRef]

- Vrtis MC. Multiple Myeloma. Home Healthc Now. 2024;42(3):140-149. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024 ;99(9):1802-1824. [CrossRef]

- Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, Katzmann JA, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412-7. [CrossRef]

- Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362-9. [CrossRef]

- Weiss BM, Abadie J, Verma P, Howard RS, et al. A monoclonal gammopathy precedes multiple myeloma in most patients. Blood. 2009;113(22):5418-22. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Htut, M., & Sharman, J. P. (2020). Efficacy of four-drug regimens in multiple myeloma: A systematic review. Blood, 136(Supplement 1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Moreau P, Kumar SK, San Miguel J, Davies F, et al. Treatment of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: recommendations from the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(3):e105-e118. [CrossRef]

- Manier S, Salem KZ, Park J, Landau DA, et al. Genomic complexity of multiple myeloma and its clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(2):100-113. [CrossRef]

- Smith D, Yong K. Multiple myeloma. BMJ. 2013;346:f3863. [CrossRef]

- Koshiaris C, Oke J, Abel L, Nicholson BD, et al. Quantifying intervals to diagnosis in myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e019758. [CrossRef]

- Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007 21;356(25):2582-90. [CrossRef]

- Ali MA, Ahmed YA, Ibrahim A. Clinical challenges: Myeloma and concomitant type 2 diabetes. South Asian J Cancer. 2013 ;2(4):290-5. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Sonneveld P, Leung N, Merlini G, et al. International Myeloma Working Group Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Myeloma-Related Renal Impairment. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1544-57. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E. The role of novel drugs in multiple myeloma. Ann Oncol. 2008 ;19 Suppl 7:vii121-7. [CrossRef]

- Mohty M, Cavo M, Fink L, Gonzalez-McQuire S, et al. Understanding mortality in multiple myeloma: Findings of a European retrospective chart review. Eur J Haematol. 2019 ;103(2):107-115. [CrossRef]

- Howell D, Smith A, Appleton S, Bagguley T, et al. Multiple myeloma: routes to diagnosis, clinical characteristics and survival - findings from a UK population-based study. Br J Haematol. 2017;177(1):67-71. [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian D, Mailankody S, Korde N, Landgren O. Smoldering multiple myeloma: pathophysiologic insights, novel diagnostics, clinical risk models, and treatment strategies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014 ;12(9):578-87.

- Howlader, N., Noone, A. M., Krapcho, M., Miller, D., Brest, A., Yu, M., et al. (2021). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/.

- Urban VS, Cegledi A, Mikala G. Multiple myeloma, a quintessential malignant disease of aging: a geroscience perspective on pathogenesis and treatment. Geroscience. 2023;45(2):727-746. [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasan CC, Hughes DA, Jayatillake MM, Mehta AB. Multiple myeloma: causes and consequences of delay in diagnosis. QJM. 2007;100(10):635-40. [CrossRef]

- Bladé J, Beksac M, Caers J, Jurczyszyn A, et al. Extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma: a systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12(3):45. [CrossRef]

- Seesaghur A, Petruski-Ivleva N, Banks VL, Wang JR, et al. Clinical features and diagnosis of multiple myeloma: a population-based cohort study in primary care. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e052759. [CrossRef]

- Loberg, M., Aas, T., Wist, E., & Kiserud, C. E. (2018). Symptoms and diagnostic delay in multiple myeloma. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening, 138(14), 1347–1351. [CrossRef]

- Koshiaris C, Van den Bruel A, Oke JL, Nicholson BD, et al. Early detection of multiple myeloma in primary care using blood tests: a case-control study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 ;68(674):e586-e593. [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc MR, LeBlanc TW, Leak Bryant A, Pollak KI, et al. A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Living With Multiple Myeloma. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2021;48(2):151-160. [CrossRef]

- Negrete-Rodríguez P, Gallardo-Pérez MM, Lira-Lara O, Melgar-de-la-Paz M, et al. Prevalence and Consequences of a Delayed Diagnosis in Multiple Myeloma: A Single Institution Experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24(7):478-483. [CrossRef]

- Friese CR, Abel GA, Magazu LS, Neville BA, et al. Diagnostic delay and complications for older adults with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(3):392-400. [CrossRef]

- Md Imran Hossain, Peter Hampson, Craig Nowell, Shamshad Khan, Ranjoy Sen, et al.; An in Depth Analysis of Factors Contributing to Diagnostic Delay in Myeloma: A Retrospective UK Study of Patients Journey from Primary Care to Specialist Secondary Care. Blood 2021; 138 (Supplement 1): 3007. [CrossRef]

- Pour L, Sevcikova S, Greslikova H, Kupska R, et al. Soft-tissue extramedullary multiple myeloma prognosis is significantly worse in comparison to bone-related extramedullary relapse. Haematologica. 2014 ;99(2):360-4. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, Mateos MV, et al.; EHA Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: guidelines@ehaweb.org; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309-322. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014. Epub 2021 3. Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2022 ;33(1):117. [CrossRef]

- Ahmann GJ, Chng WJ, Henderson KJ, Price-Troska TL, et al. Effect of tissue shipping on plasma cell isolation, viability, and RNA integrity in the context of a centralized good laboratory practice-certified tissue banking facility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 ;17(3):666-73. [CrossRef]

- Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Cruz-Gordillo P, et al. Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014 13;25(1):91-101. [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Anderson, K.; Rajkumar, S.V.; San Miguel, J.; et al.Multiple myeloma: International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and response.Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15(12), e538–e548. [CrossRef]

- Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA, McPhail S, Neal RD, et al. Measures of promptness of cancer diagnosis in primary care: secondary analysis of national audit data on patients with 18 common and rarer cancers. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):686-90. [CrossRef]

- Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014 ;28(5):1122-8. [CrossRef]

- Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, Therneau TMet al. Immunoglobulin free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(2):785-9. [CrossRef]

- Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Larson DR, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1721-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60482-5. Erratum in: Lancet. 2010;376(9738):332. [CrossRef]

- Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, Durie BGM, et al. International myeloma working group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 ;20(6):e302-e312. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30309-2. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2019 ;20(7):e346. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, et al.International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 ;15(12):e538-48. [CrossRef]

- Boyd KD, Ross FM, Walker BA, Wardell CP, et al.; NCRI Haematology Oncology Studies Group. Mapping of chromosome 1p deletions in myeloma identifies FAM46C at 1p12 and CDKN2C at 1p32.3 as being genes in regions associated with adverse survival. Clin Cancer Res. 201115;17(24):7776-84. [CrossRef]

- Murray D, Kumar SK, Kyle RA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Detection and prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a study utilizing mass spectrometry-based monoclonal immunoglobulin rapid accurate mass measurement. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9(12):102. [CrossRef]

- Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, Bryant S, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1437-44.

- Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Harvey TC, et al. Serum test for assessment of patients with Bence Jones myeloma. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):489-91. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Mateos MV. Smoldering multiple myeloma. Blood. 2015 14;125(20):3069-75. [CrossRef]

- Zamagni E, Nanni C, Patriarca F, Englaro E, et al. A prospective comparison of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and whole-body planar radiographs in the assessment of bone disease in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2007;92(1):50-5. [CrossRef]

- Avet-Loiseau H, Attal M, Moreau P, Charbonnel C, et al. Genetic abnormalities and survival in multiple myeloma: the experience of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome. Blood. 2007;109(8):3489-95. [CrossRef]

- Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Cruz-Gordillo P, et al.; Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium; Getz G, Golub TR. Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(1):91-101. [CrossRef]

- Sandra CM Quinn, Lauren Kelly, Tom Lewis; The Additional Disease Burden Accompanying a Delayed Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma: Utilising a Large Real-World Evidence Base. Blood 2023; 142 (Supplement 1): 3771. [CrossRef]

- Luciano J Costa, Wilson I Gonsalves, Shaji Kumar; Early Mortality in Multiple Myeloma: Risk Factors and Impact on Population Outcomes. Blood 2014; 124 (21): 1320. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Rosinol L, Bladé J, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of renal failure in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22(8):1485-93. [CrossRef]

- Kansal A, Latour JM, See KC, Rai S, et al. Interventions to promote cost-effectiveness in adult intensive care units: consensus statement and considerations for best practice from a multidisciplinary and multinational eDelphi study. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):487. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04766-2. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2024;28(1):121. [CrossRef]

- Religioni U, Barrios-Rodríguez R, Requena P, Borowska M, et al. Enhancing Therapy Adherence: Impact on Clinical Outcomes, Healthcare Costs, and Patient Quality of Life. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025 17;61(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Yong, C., Korol, E., Khan, Z., Lin, et al. (2016). A real-world evidence systematic literature review of health-related quality of life, costs and economic evaluations in newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood, 128(22), 4777. [CrossRef]

- Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA, McPhail S, Neal RD, et al. Measures of promptness of cancer diagnosis in primary care: secondary analysis of national audit data on patients with 18 common and rarer cancers. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):686-90. [CrossRef]

- Green T, Atkin K, Macleod U. Cancer detection in primary care: insights from general practitioners. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S41-9. [CrossRef]

- Koshiaris C, Van den Bruel A, Oke JL, Nicholson BD, et al. Early detection of multiple myeloma in primary care using blood tests: a case-control study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 ;68(674):e586-e593. [CrossRef]

- Lyratzopoulos G, Vedsted P, Singh H. Understanding missed opportunities for more timely diagnosis of cancer in symptomatic patients after presentation. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S84-91. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L., Carmichael, J., Cook, G., Shinkins, B., et al. (2022). Diagnosing myeloma in general practice: How might earlier diagnosis be achieved? British Journal of General Practice, 72(723), 462–463. [CrossRef]

- Funston, G., Hamilton, W., Abel, G. A., Crosbie, E. J., et al. (2021). Development and validation of electronic health record–based prediction models for early diagnosis of multiple myeloma. British Journal of General Practice, 71(702), e528–e537. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar SV. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Staging System for Multiple Myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418-23. [CrossRef]

- Rögnvaldsson S, Love TJ, Thorsteinsdottir S, Reed ER, et al. Iceland screens, treats, or prevents multiple myeloma (iStopMM): a population-based screening study for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and randomized controlled trial of follow-up strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(5):94.doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00480-w. Erratum in: Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A, Basaleem H, et al. Global Burden of Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2018 ;4(9):1221-1227. [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(6):676-681. [CrossRef]

- Vaxman I, Gertz MA. How I approach smoldering multiple myeloma. Blood. 2022;140(8):828-838. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011670. Erratum in: Blood. 2023;141(11):1366. [CrossRef]

- Pour, L.; Sevcikova, S.; Greslikova, H.; Mikulkova, Z.; et al.Biomarkers for monitoring and prognosis of multiple myeloma.Blood Rev. 2020, 40, 100640. [CrossRef]

- Manier S, Park J, Capelletti M, Bustoros M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA and circulating tumor cells in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1691. [CrossRef]

- Alipour E, Pooyan A, Shomal Zadeh F, Darbandi AD, et al. Current Status and Future of Artificial Intelligence in MM Imaging: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(21):3372. [CrossRef]

- Allegra A, Tonacci A, Sciaccotta R, Genovese S, et al. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications in Multiple Myeloma Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Selection. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3):606. [CrossRef]

- Neri P, Lee H, Bahlis NJ. Artificial Intelligence Individualized Risk Classifier in Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(11):1207-1210. [CrossRef]

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2010;5(2):62-9. [CrossRef]

- Landgren O, Rajkumar SV. New Developments in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Assessment of Response in Multiple Myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(22):5428-5433. [CrossRef]

- Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, et al. Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:2997. [CrossRef]

- van Nieuwenhuijzen N, Spaan I, Raymakers R, Peperzak V. From MGUS to Multiple Myeloma, a Paradigm for Clonal Evolution of Premalignant Cells. Cancer Res. 2018;78(10):2449-2456. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).