1. Introduction

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a novel and rapidly evolving class of targeted therapeutics that combine the high specificity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with the potent cytotoxic effects of small-molecule drugs. These engineered molecules are designed to selectively deliver cytotoxic agents to specific cells, thereby reducing off-target toxicity and enhancing therapeutic efficacy. In oncology, ADCs have already demonstrated significant clinical success, particularly in the treatment of hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Agents such as trastuzumab emtansine and brentuximab vedotin exemplify how ADCs can effectively target cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy tissues. This review comprehensively explores key aspects of the use of ADCs in autoimmune disorders—an evolving field in immunotherapy.

Although originally developed for cancer therapy, the potential of ADCs in autoimmune diseases is now being explored. Autoimmune conditions are characterized by the immune system mistakenly attacking the body’s own cells and tissues. Conventional therapies often involve broad immunosuppressants, which can lead to systemic side effects and an increased risk of infections. In this context, ADCs offer a promising alternative by enabling targeted immunomodulation. By directing the cytotoxic payload specifically to pathogenic immune cells—such as autoreactive B cells or T cells—ADCs can suppress disease activity while preserving overall immune function [

1].

The development of ADCs for autoimmune and cancer indications faces unique challenges, including the need to identify disease-specific markers that distinguish pathogenic from protective immune cells. However, advances in immunology and molecular targeting are paving the way for precision-based approaches [

2]. For instance, targeting CD19 or CD22 on autoreactive B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or multiple sclerosis (MS) is under investigation. Furthermore, novel linker technologies and payloads are being optimized for use in chronic inflammatory conditions, ensuring controlled drug release and reduced toxicity [

3].

ADCs are composed of three main components [

4]:

Monoclonal antibody (mAb): Targets a disease-specific antigen.

Linker: Ensures stable attachment and release of the payload in target cells.

Payload (cytotoxic agent or immunomodulator): Induces apoptosis or modifies immune cell function.

In autoimmune disorders, the aim is to selectively deplete autoreactive immune cells (e.g., B cells, plasma cells, or T cells) without affecting healthy tissues [

1].

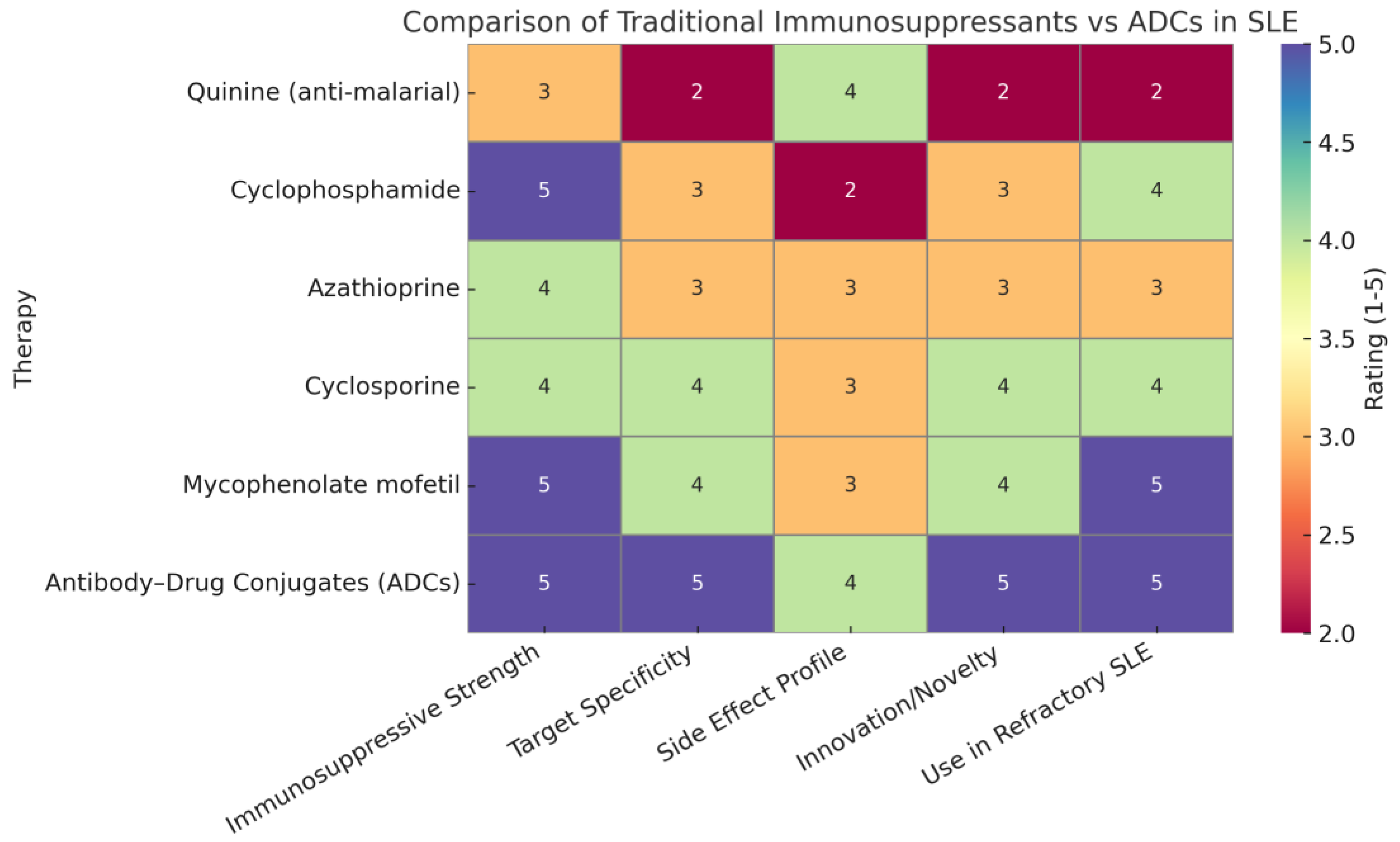

1.1. Comparative Analysis: Traditional Immunosuppressants vs. ADCs in SLE

The rapid growth of the chemical industry in the 19th and 20th centuries marked a transformative era in medicine, particularly in the development of immunosuppressive agents. The identification of key compounds such as anti-malarials (e.g., quinine), cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil laid the foundation for effective SLE management. These drugs provided broad-spectrum immune modulation, reducing disease activity and improving long-term outcomes in many patients. However, each of these agents is associated with specific limitations, including off-target effects, variable patient response, and toxicity due to systemic immune suppression [

4]. In contrast, the emergence of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) represents a paradigm shift. ADCs combine the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potency of cytotoxic drugs, allowing for targeted immune cell depletion or modulation with minimal off-target toxicity. In SLE, where autoreactive B cells and plasma cells play a central role, ADCs offer the potential to selectively eliminate pathogenic immune cells while sparing protective immunity [

5].

1.2. Justification of Heatmap Ratings

The heatmap ratings summarize the comparative strengths of traditional immunosuppressants versus antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) across key therapeutic parameters. ADCs scored highly in immunosuppressive strength due to their potent, targeted mechanism of action, often matching or exceeding traditional therapies. They received top ratings for target specificity, reflecting their precision in binding disease-specific antigens like CD19 and BCMA, unlike older drugs that act broadly. The side effect profile was rated slightly lower for ADCs than for specificity because, although targeted delivery reduces systemic toxicity, long-term safety data are still maturing. In terms of innovation, ADCs clearly surpassed traditional therapies, representing a major advancement in immunotherapy. Their high rating for use in refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is based on promising preclinical and clinical findings showing their ability to eliminate resistant immune cells where traditional treatments often fail. Overall, the heatmap highlights the evolving advantage of ADCs in modern autoimmune disease management [

6].

Table 1 shows a comparative evaluation of immunosuppressive therapies: traditional agents versus ADCs [7].

1.3. Clinical Relevance

As evidenced in early-phase trials and preclinical studies, ADCs like anti-CD19 or anti-BCMA conjugates have shown promise in modulating B-cell activity in autoimmune diseases, including lupus. These advances are particularly important for patients who fail standard immunosuppressants or experience intolerable side effects. Furthermore, while traditional drugs require lifelong administration and are associated with cumulative toxicity, ADCs hold the promise of inducing durable remission with limited dosing. As technologies improve, ADCs may be engineered with payloads that modulate immune activity without inducing profound cytotoxicity—an ideal strategy for chronic conditions like SLE [

7].

Figure 1 shows a comparison of traditional immunosuppressants versus ADCs in SLE.

2. Mechanism of Action

2.1. Mechanism of Action of Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs) in Autoimmune Diseases

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are an advanced therapeutic modality designed to combine the targeting capability of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with the potency of cytotoxic or immunomodulatory agents. While ADCs are widely recognized for their success in oncology, they are now emerging as promising tools in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. This transition is driven by the increasing demand for precision medicine approaches that can mitigate disease activity without causing widespread immunosuppression [

8].

ADCs consist of three integral components: a monoclonal antibody, a linker, and a payload. Each of these components plays a critical role in ensuring the targeted action and therapeutic efficacy of the ADC.

2.2. Monoclonal Antibody (mAb)

The monoclonal antibody component is the targeting arm of the ADC. It is designed to recognize and bind with high specificity to an antigen that is overexpressed or uniquely present on diseased cells. In the context of autoimmune diseases, potential targets include surface proteins expressed on autoreactive B cells, plasma cells, or T cells [

4]. Examples include CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD38, which are commonly expressed on B cell subsets implicated in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and multiple sclerosis (MS). The selective targeting of these antigens ensures that the therapeutic payload is delivered predominantly to cells that drive autoimmune pathology, thereby sparing non-pathogenic immune cells and reducing systemic toxicity.

2.3. Linker

The linker is a crucial structural element that connects the mAb to the cytotoxic or immunomodulatory payload. Linkers must be stable in circulation to prevent premature release of the payload, which could lead to systemic toxicity. At the same time, they should be cleavable within the target cells to enable the release of the active drug once the ADC is internalized [

9]. There are two main types of linkers: cleavable and non-cleavable.

Cleavable linkers are designed to respond to specific intracellular conditions, such as low pH, high glutathione concentrations, or the presence of particular enzymes (e.g., cathepsins). These features are often present within endosomes or lysosomes following receptor-mediated internalization. Non-cleavable linkers, on the other hand, rely on the complete degradation of the antibody component within the lysosome to release the active compound. The choice of linker influences the stability, efficacy, and safety of the ADC [

10].

2.4. Payload (Cytotoxic Agent or Immunomodulator)

The payload is the functional component of the ADC that exerts the therapeutic effect. In oncology, payloads are typically highly potent cytotoxins, such as microtubule inhibitors (e.g., monomethyl auristatin E) or DNA-damaging agents (e.g., calicheamicin). In autoimmune diseases, the payload may serve a different function [

11]. Rather than indiscriminate cytotoxicity, the goal is often to selectively eliminate autoreactive immune cells or modulate their activity to restore immune tolerance.

For instance, in B cell-mediated diseases like SLE, an ADC might be designed to deliver a cytotoxic agent that induces apoptosis in autoreactive B cells or long-lived plasma cells that produce pathogenic autoantibodies [

4,

12]. Alternatively, immunomodulatory payloads may interfere with intracellular signaling pathways, inhibit proliferation, or induce regulatory phenotypes in T cells. These mechanisms allow for precise immunosuppression without the broad side effects seen with conventional immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids or methotrexate [

13].

2.5. Cellular Mechanism of ADCs

The therapeutic activity of ADCs begins when the mAb component binds to the specific antigen on the surface of the target immune cell. This binding triggers internalization of the ADC–antigen complex via receptor-mediated endocytosis [

14]. The ADC is then trafficked to endosomes and subsequently to lysosomes, where the acidic environment and enzymatic activity facilitate the cleavage of the linker and release of the payload [

15].

Once released, the cytotoxic or immunomodulatory agent acts within the target cell. In the case of a cytotoxic payload, mechanisms such as microtubule disruption, DNA damage, or inhibition of protein synthesis can lead to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [

16]. For immunomodulatory payloads, the action may include suppression of inflammatory cytokine production, inhibition of antigen presentation, or modulation of transcription factors involved in autoimmunity [

17].

2.6. Relevance in Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by the dysregulation of immune tolerance, often involving the persistence of autoreactive lymphocytes that escape central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms [

18]. Conventional immunosuppressive therapies lack specificity and frequently lead to serious side effects, including infections and malignancy. ADCs present a more refined alternative by allowing the targeted removal or modulation of specific immune cells implicated in the disease process [

8].

For example, CD19- or CD22-directed ADCs have shown promise in preclinical models of SLE and MS by depleting autoreactive B cell populations. In multiple sclerosis, targeting CD25-expressing activated T cells may prevent relapses and disease progression. In autoimmune blistering diseases, ADCs directed against CD38-expressing plasma cells are under investigation for their ability to reduce autoantibody production [

8,

18].

3. Targets in Autoimmune Diseases for Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) Therapy

The application of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) in autoimmune diseases hinges on the identification of appropriate cell surface targets that are specifically or predominantly expressed on pathogenic immune cells [

8,

19]. Unlike in oncology, where tumor-associated antigens are often clearly delineated, autoimmune disorders present a more complex landscape due to the involvement of immune cells that may also serve protective roles under physiological conditions. Nonetheless, several promising targets have been identified, particularly on B cells, plasma cells, and activated immune cell subsets. These targets include CD19, CD20, CD22, B cell maturation antigen (BCMA), and CD38, all of which are under investigation for their therapeutic potential in a range of autoimmune conditions [

20,

21].

3.1. CD19, CD20, and CD22

CD19, CD20, and CD22 are surface proteins expressed on various stages of B cell development [

22]. CD19 is found from the early pre-B cell stage through to mature B cells but is lost upon terminal differentiation into plasma cells. CD20 is predominantly expressed on mature B cells, while CD22 is more restricted and mainly acts as a regulator of B cell receptor (BCR) signaling.

These antigens have been targeted in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and multiple sclerosis (MS). In SLE, autoreactive B cells play a central role in autoantibody production, antigen presentation, and cytokine secretion. Targeting CD19 or CD20 with ADCs facilitates the selective depletion of these pathogenic B cells. For example, CD22-targeting ADCs may also modulate B cell activity and reduce disease flares by inhibiting aberrant BCR signaling and B cell survival. The use of ADCs targeting these markers allows for deeper and more durable B cell depletion compared to monoclonal antibodies alone, owing to the cytotoxic payload that induces apoptosis upon internalization [

21].

3.2. BCMA (B Cell Maturation Antigen)

BCMA is a transmembrane receptor expressed almost exclusively on plasma cells and a subset of late-stage B cells. Its restricted expression pattern and crucial role in plasma cell survival make it an attractive target for ADC therapy in diseases characterised by pathogenic autoantibody production [

23].

3.3. CD38

CD38 is a multifunctional ectoenzyme that is widely expressed on activated T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and plasma cells, particularly in inflammatory environments. In autoimmune diseases, CD38 expression is upregulated in several pathological contexts, including autoimmune cytopenias such as systemic sclerosis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia and immune thrombocytopenia [

24]. In these conditions, CD38-targeting ADCs may offer therapeutic benefits by selectively depleting hyperactivated immune cells responsible for the destruction of red blood cells or platelets. Because CD38 is less expressed on resting immune cells, ADCs directed against this target may achieve selective immunosuppression with a lower risk of broad immunodeficiency.

4. Emerging ADCs in Clinical/Preclinical Studies

The development of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) for autoimmune diseases is an area of growing interest, with both clinical and preclinical studies exploring new targets and innovative delivery systems. These ADCs aim to improve upon the limitations of conventional immunosuppressive therapies by offering highly specific targeting of disease-driving immune cells. The development of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) for autoimmune diseases is an area of growing scientific and clinical interest. Traditionally, ADCs have been extensively studied and employed in oncology, where they are designed to deliver highly potent cytotoxic agents directly to cancer cells while sparing healthy tissues. Their success in targeting malignant cells has paved the way for investigating their use in other areas of medicine, including immune-mediated conditions [

3,

4].

Table 2 shows emerging antibody–drug conjugates in autoimmune clinical and preclinical studies.

Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), are characterised by the immune system’s failure to distinguish self from non-self. This leads to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Conventional treatments—including corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biologics—are often associated with broad immune suppression, leaving patients vulnerable to infections and malignancies. Therefore, there is a pressing need for therapies that can selectively target the pathological components of the immune system without compromising overall immune function [

25].

ADCs offer a precision medicine approach by combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the functional impact of cytotoxic or immunomodulatory agents. These agents are designed to target specific cell surface markers expressed predominantly on autoreactive immune cells such as B cells, plasma cells, or activated T cells. Once bound, the ADC is internalized, and the payload is released within the cell to induce apoptosis or modulate its function. Prominent targets under investigation include CD19, CD22, CD38, and BCMA, all of which are implicated in the survival and function of autoreactive lymphocytes [

26].

4.1. VAY736 (Ianalumab)—BAFF-R Target-SLE-Phase 2

VAY736, also known as Ianalumab, targets the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R), a key survival signal for B cells. In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), B cell hyperactivity and persistent autoantibody production are central to disease progression. VAY736 combines BAFF-R blockade with cell-depleting capability. Currently in Phase 2 clinical trials, it has shown promising reductions in disease flares and serological activity in early results [

27,

28]. Its success and limitation are:

4.2. TAK-079 Is a Fully Human IgG1λ Monoclonal Antibody Targeting CD38

TAK-079 is a fully human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody targeting CD38, a molecule expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, plasma cells, and activated B and T lymphocytes. In a cynomolgus monkey model of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), TAK-079 demonstrated both prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy. Administered intravenously at 3 mg/kg weekly, it significantly reduced arthritis severity, joint swelling, and radiographic damage compared to vehicle-treated controls. The treatment led to marked depletion of CD38-expressing NK, B, and T cells, correlating with decreased levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and alkaline phosphatase. Histopathological analyses revealed reduced pannus formation, leukocyte infiltration, cartilage degradation, and bone resorption in TAK-079-treated animals. Notably, TAK-079 was well tolerated, with no significant adverse effects observed. These findings suggest that TAK-079’s targeted depletion of CD38-positive cells may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, warranting further clinical investigation [

29,

30].

4.3. ABBV-3373 Is an Innovative Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC)

ABBV-3373 is an innovative antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) combining adalimumab (an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody) with a glucocorticoid receptor modulator (GRM), designed to deliver anti-inflammatory effects directly to activated immune cells. In a randomised, double-blind, active-controlled Phase IIa trial involving 48 adults with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis unresponsive to methotrexate, participants received either ABBV-3373 or adalimumab. At week 12, ABBV-3373 demonstrated a greater reduction in Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) compared to historical adalimumab data (−2.65 vs. −2.13;

p = 0.022) and combined in-trial/historical adalimumab (−2.65 vs. −2.29; probability 89.9%). Notably, 70.6% of ABBV-3373 recipients who achieved DAS28-CRP ≤ 3.2 at week 12 maintained this response at week 24, despite switching to placebo. The safety profile was comparable to adalimumab, with one case of anaphylactic shock in the ABBV-3373 group, which was mitigated by extending infusion duration. These findings support further development of ABBV-3373 as a potential treatment for rheumatoid arthritis [

31].

4.4. CD45-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugates (CD45-ADCs)

Researchers from Magenta Therapeutics have developed CD45-targeted antibody–drug conjugates (CD45-ADCs) as a novel conditioning strategy for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) in autoimmune diseases. Traditional conditioning regimens are often associated with significant toxicity, limiting the broader application of auto-HSCT. In preclinical models, a single dose of CD45-ADC effectively depleted hematopoietic stem and immune cells in humanized mice and non-human primates. In murine models of autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis and arthritis, CD45-ADC conditioning followed by congenic HSCT resulted in full donor chimerism, delayed disease onset, and reduced severity. These findings suggest that CD45-ADCs can safely and efficiently prepare patients for auto-HSCT, potentially expanding its use by mitigating the risks associated with conventional chemotherapy-based conditioning. This targeted approach may offer a more tolerable and effective means to achieve immune system reset in various autoimmune conditions [

32].

4.5. Development of an Anti-IL-7R Monoclonal Antibody (A7R) Conjugated with Cytotoxic Agents SN-38 and Monomethyl Auristatin E (MMAE)

This study explores the therapeutic potential of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting the interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R) to address steroid-resistant cancers and autoimmune diseases. The researchers developed an anti-IL-7R monoclonal antibody (A7R) conjugated with cytotoxic agents SN-38 and monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). These ADCs demonstrated significant anti-tumor effects against both steroid-sensitive and steroid-resistant malignant lymphoid cells in vitro and in vivo. In a mouse model of autoimmune arthritis, the IL-7R-targeting ADCs effectively reduced inflammation, outperforming traditional steroid treatments. The findings suggest that IL-7R plays a crucial role in steroid resistance and that targeting IL-7R-positive cells with ADCs could offer a novel therapeutic strategy for treating refractory cancers and autoimmune conditions. This approach holds promise for patients who do not respond to conventional steroid therapies [

33].

5. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Autoimmune Diseases: A Discussion

5.1. Target Specificity vs. Conventional Therapy

Conventional immunosuppressants (like corticosteroids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, DMARDs) broadly dampen the immune system, often leading to significant off-target effects and toxicity. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) offer a more

targeted approach: they combine the precision of monoclonal antibodies with potent cell-killing or immunomodulating payloads, homing in on disease-causing cells while sparing healthy tissue [

34]. This selective delivery not only

reduces systemic side effects but can also enhance therapeutic efficacy by concentrating the drug where it’s needed most [

34]. For example, chronic steroid use in autoimmune disease is limited by severe side effects, but researchers have developed ADCs that attach a glucocorticoid to an antibody (e.g., an anti-CD74-steroid ADC) to direct the immunosuppressive effect toward immune cells and minimize exposure elsewhere. Such an approach illustrates how ADCs can

surpass conventional therapy in specificity, acting like “guided missiles” to eliminate pathogenic immune cells (B cells, T cells, etc.) involved in autoimmunity while avoiding collateral damage [

35,

36]. Indeed, early

preclinical prototypes of immunosuppressive ADCs have validated this concept, delivering kinase-inhibitor payloads selectively to immune cells as a means to treat autoimmune pathology.

5.2. Reduced Dosing Frequency and Pharmacokinetic Advantages

ADCs inherit the pharmacokinetic benefits of their antibody component, notably a long plasma half-life that allows for

infrequent dosing schedules compared to traditional small-molecule drugs. Most therapeutic antibodies circulate for days to weeks, enabling dosing intervals of weeks rather than daily administration. This can translate into improved patient compliance and convenience [

36,

37]. Furthermore, by directly targeting drugs to diseased tissues, ADCs may require

lower total dosages than systemic therapies. For instance, one strategy in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) proposes using a DMARD as the payload of an ADC—thereby delivering the drug right to joint-infiltrating cells—which could reduce the need for multiple high doses and potentially enhance patient compliance [

38]. In short, the efficient delivery and prolonged circulation of ADCs offer pharmacokinetic and dosing advantages over conventional immunosuppressants, maintaining therapeutic levels with less frequent administration [

36,

37].

5.3. Disease-Modifying Potential and Long-Term Remission

By precisely attacking the cells or mediators driving disease, ADCs have shown promise for

modifying disease course and inducing longer remissions in autoimmune disorders. Unlike conventional therapies that often only suppress inflammation temporarily, a well-designed ADC can selectively eliminate pathogenic immune cell populations, potentially leading to deeper and more durable responses. Early clinical data are encouraging: in a proof-of-concept trial for RA, an anti-TNF ADC (adalimumab conjugated to a steroid) produced greater improvements in disease activity scores compared to the anti-TNF antibody alone, suggesting superior outcomes over the standard biologic therapy [

39]. Similarly, a preclinical ADC targeting plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lupus (via an anti-BDCA2 antibody conjugated to a glucocorticoid agonist) achieved

total suppression of pathological type I interferon production, far exceeding the effect of the naked antibody and highlighting the potential for profound immunomodulation [

40]. Notably, an open-label Phase II study in severe systemic sclerosis found that an anti-CD30 ADC (brentuximab vedotin) led to significant skin fibrosis improvement (mean ~11 point reduction in mRSS skin score at 48 weeks) in patients with refractory disease. Several patients achieved meaningful clinical responses without major safety issues, indicating that ADC-driven depletion of pathogenic cells (in this case, CD30

+ activated T cells/fibroblasts) can translate into tangible disease amelioration [

41]. These examples underscore the potential of ADCs to act as

disease-modifying agents, inducing sustained remission by removing or reprogramming the immune culprits of autoimmune disease [

39,

40,

41].

5.4. Challenges in ADC Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases

Despite their promise, the use of ADCs in autoimmunity comes with challenges that must be addressed:

Target Antigen Expression: Selecting the right antigen is critical. The ideal target is abundantly expressed on pathogenic immune cells but minimal on normal cells [

42]. In autoimmune diseases, many candidate antigens (e.g., CD20 on B cells, CD3 on T cells) are not unique to “bad actors”—they also appear on healthy immune cells. Targeting such antigens with an ADC risks broad immune depletion. For instance, CD6 is present on essentially all T cells, not just autoreactive ones. A recent approach to navigate this issue used an anti-CD6 ADC carrying a cell-cycle toxin so that only actively dividing (pathogenic) T cells are killed, whereas resting T cells are left unharmed [

42]. This example shows how careful target and payload selection can improve specificity. Nonetheless, identifying truly disease-specific markers (or selectively targeting activated/affected cell subsets) remains a challenge in order to avoid

off-target tissue damage and generalized immunosuppression [

35].

Payload Toxicity and Bystander Effects: ADC payloads are often highly potent (e.g., chemotoxins) to ensure the target cells are effectively destroyed. If the linker releases the drug too early or the drug diffuses out of target cells, normal tissues can be exposed to the toxin—a phenomenon known as the “bystander effect.” In cancer ADC development, bystander killing can sometimes be beneficial; but in autoimmune diseases, it could damage healthy immune cells or organs, leading to toxicity. Ensuring a

stable linker that only releases the payload inside the target cell (upon internalization) is therefore paramount [

36]. Additionally, payload choice may shift for autoimmune indications: rather than classical cytotoxins, payloads might be immunosuppressants (such as steroids or kinase inhibitors) to modulate cell function instead of outright killing. Even so, these active drugs can cause serious side effects if widely released. For example, an ADC delivering a glucocorticoid showed promise in concentrating steroid activity in immune cells, but any off-target release of the steroid could still contribute to systemic corticosteroid effects if not fully controlled [

36]. Careful engineering is required to minimize unwanted payload release. Overall, toxicity management is a key challenge—ADCs must be potent enough to impact disease drivers but safe enough to not create new problems [

35,

43].

Hypogammaglobulinemia and Immune Suppression: Since many autoimmune diseases are driven by B cells or plasma cells, several ADC strategies aim to deplete these populations. A potential consequence of prolonged or aggressive B cell–targeted ADC therapy is

hypogammaglobulinemia—analogous to what is observed with rituximab and other B-cell depleting antibodies. Patients on long-term rituximab can develop significantly lowered immunoglobulin levels, leading to increased infection risk [

44]. An ADC that more efficiently or persistently wipes out B cells could pose a similar or greater risk of secondary immunodeficiency. This means patients might require monitoring of IgG levels and prophylactic measures (e.g., IVIG replacement or antibiotics) if an ADC induces prolonged B-cell aplasia [

44]. More broadly, if an ADC indiscriminately eliminates immune cells, patients could experience opportunistic infections or impaired immune surveillance. The field is exploring ways to mitigate this—for example, the previously mentioned CD6-ADC that targets only proliferating T cells is one tactic to avoid wiping out the entire T-cell pool [

43]. Such strategies aim to retain enough immune function to prevent immunodeficiency while still removing the autoreactive cells. Balancing effective autoimmune suppression with the preservation of immune competence will be a continual challenge as ADC therapies are refined.

Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADA) and Immunogenicity: As protein-based therapeutics, ADCs can themselves trigger an immune response. Anti-drug antibodies against the ADC’s antibody component (or even against neo-epitopes created by the linker-payload) may neutralize the drug or accelerate its clearance from the body, reducing efficacy. Immunogenicity can also manifest as allergic or infusion reactions. To minimize this, modern ADCs employ fully human or humanized antibodies and linker technologies designed to be as inert as possible. Indeed, third-generation ADCs have moved to humanized IgG backbones specifically to

reduce the risk of ADA formation and improve pharmacokinetics [

37]. Many ADCs in oncology have low reported immunogenicity, but in chronic use (as would be the case for autoimmune diseases) even a small incidence of ADA could become problematic over time. Therefore, immunogenicity must be carefully assessed in trials. In some cases, concomitant immunosuppressive medications or intermittent dosing schedules might be used to mitigate ADA development. Ultimately, achieving low immunogenicity is critical so that patients can receive repeated ADC doses long-term without losing response [

35,

37].

Table 2.

A list of ADCs that have been tested for indications in autoimmune diseases. This document provides a concise summary of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) evaluated for use in autoimmune diseases, based on preclinical and clinical research. Each entry includes the antibody target, the drug payload, the linker technology employed, and the testing status of the conjugate. These ADCs illustrate the diversity of strategies employed to target specific immune components in autoimmune diseases, offering potential for more effective and less toxic therapies. Adapted from [

36].

Table 2.

A list of ADCs that have been tested for indications in autoimmune diseases. This document provides a concise summary of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) evaluated for use in autoimmune diseases, based on preclinical and clinical research. Each entry includes the antibody target, the drug payload, the linker technology employed, and the testing status of the conjugate. These ADCs illustrate the diversity of strategies employed to target specific immune components in autoimmune diseases, offering potential for more effective and less toxic therapies. Adapted from [

36].

| Indications |

ADCs |

Antibody |

Linkers |

Payloads |

Testing Status |

Ref. |

Autoimmune and

inflammatory models |

Anti-CXCR4

dasatinib |

Humanized

anti-CXCR4

mAb (HLCX) |

Tetra-poly-ethylene glycol linker |

Dasatinib |

In vitro pre-clinical |

[45] |

| Autoimmune models |

Anti-CD74

fluticasone

propionate

(Anti-CD74-flu449) |

Human

anti-CD74 mAb |

Pyrophosphate

acetal linker |

Fluticasone

propionate |

In vivo pre-clinical |

[46] |

| Myasthenia gravis |

Anti-TNFRSF13c siRNA |

anti-TNFRSF13c mA |

Protamine linker |

siRNA |

In vivo pre-clinical |

[47] |

| Systemic sclerosis |

Anti-CD30

Vedotin

(ADCETRIS) |

Chimeric

anti-CD30 mAb

(cAC10, SGN-30) |

Val-Cit linker |

MMAE

(Monomethyl auristatin E) |

Phase II clinical trial (NCT03198689), (NCT03222492) |

[48] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

Anti-IL-6

alendronate |

Humanized

anti-IL-6

mAb (tocilizumab) |

PDPH-PEG-NHS |

Alendronate (ALD) |

In vivo pre-clinical |

[49] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

Anti-FRβ

Pseudomonas

exotoxin A (PE38) |

Murine anti-FRβ mAb |

NA |

Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE38) |

In vivo pre-clinical |

[50] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

Anti–C5aR1 C5

siRNA |

Murine anti-C5aR1

mAb |

Protamine linker |

C5 siRNA |

In vivo pre-clinical |

[51] |

Bowel disease,

ulcerative colitis,

and Crohn’s disease. |

anti-CD70

mAb–Budesonide |

Anti-CD70 mAb |

Carbamate linkage |

Budesonide |

In vitro and vivo pre-clinical study |

[52] |

Anti-CD74–Fluticasone Propionate: This ADC targets CD74, expressed on immune cells such as B cells and monocytes. It utilises a human anti-CD74 monoclonal antibody linked via a pyrophosphate acetal linker to fluticasone propionate, a corticosteroid. The conjugate is under in vivo preclinical testing and aims to selectively deliver anti-inflammatory effects to CD74-positive cells [

36].

Anti-CXCR4–Dasatinib: Designed to target CXCR4 on T cells and hematopoietic cells, this ADC uses a humanised anti-CXCR4 antibody and a tetra-polyethylene glycol linker to deliver dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. It is currently being assessed in vitro for preclinical efficacy in autoimmune and inflammatory models [

45].

Anti-TNFRSF13C siRNA: This conjugate targets TNFRSF13C, a receptor involved in B-cell survival. It employs an anti-TNFRSF13C monoclonal antibody conjugated to siRNA via a protamine linker. This construct is in vivo preclinical and represents a novel RNAi-based therapeutic approach for diseases like myasthenia gravis [

47].

Anti-CD30–Vedotin (Brentuximab Vedotin): Utilising a chimeric anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody, this ADC links MMAE (Monomethyl auristatin E) via a valine-citrulline (Val-Cit) linker. It has progressed to Phase II clinical trials for conditions including systemic sclerosis [

48].

Anti-IL-6–Alendronate: This ADC involves a humanised anti-IL-6 antibody (tocilizumab) connected to alendronate using a PDPH-PEG-NHS linker. It is tested in vivo in preclinical settings, aiming to combine anti-inflammatory and bone-protective effects for rheumatoid arthritis treatment [

49].

Anti-FRβ–PE38: Using a murine monoclonal antibody against folate receptor beta, this ADC delivers a potent bacterial toxin, PE38. It is under in vivo preclinical evaluation for rheumatoid arthritis, aiming to eliminate activated macrophages in the synovium [

50].

Anti-C5aR1–C5 siRNA: This construct targets the C5a receptor using a murine antibody linked to C5-specific siRNA through a protamine linker. It is tested in vivo, aiming to reduce complement-mediated inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis [

51].

Anti-CD70–Budesonide: Aimed at diseases like ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, this ADC uses an anti-CD70 monoclonal antibody to deliver budesonide via a carbamate linkage. It is being assessed in vitro and in vivo in preclinical models [

52].

7. Summary

The ADCs outlined above represent an emerging paradigm in the treatment of autoimmune diseases: leveraging the specificity of antibodies to deliver potent immunomodulatory agents directly to pathogenic immune cells or inflammatory sites. Each of these experimental ADCs addresses a current therapeutic challenge in autoimmunity. For example, anti-CD74-fluticasone and anti-CD70-budesonide ADCs aim to retain the efficacy of glucocorticoids while avoiding their systemic toxicities by cell-targeted delivery [

43]. ADCs like anti-CXCR4-dasatinib and anti-CD30-vedotin seek to selectively suppress or eliminate autoreactive lymphocytes, reducing disease activity without broad immunosuppression [

45,

53]. Meanwhile, antibody–siRNA conjugates (against BAFF-R or C5/C5aR1) introduce nucleic acid therapies into specific immune cells, achieving gene silencing in vivo with unprecedented precision [

51,

54]. These approaches, though largely in preclinical or early clinical stages, have shown

promising results in animal models and initial trials, ranging from substantial disease attenuation in arthritis models [

51] to clinically meaningful improvements in conditions like systemic sclerosis [

40].

It is important to note that the development of ADCs for autoimmune diseases is still in its infancy, and challenges remain. Optimizing linker chemistry is crucial, as seen with the need for more stable yet cleavable linkers to keep payloads intact until internalization (e.g., Cathepsin-sensitive phosphate linkers for steroid ADCs) [

55]. Ensuring that payloads have the appropriate potency and cell permeability is also critical—an issue highlighted by the fluticasone-CD74 ADC experience where a highly permeable payload led to off-target effects [

43]. Safety will be a major consideration: unlike cancer, where some off-target toxicity is tolerated, autoimmune patients require preservation of normal immune function. Thus, many of these ADCs use payloads that modulate rather than ablate immune cells (kinase inhibitors, steroids, or selective toxins) to strike a balance between efficacy and safety. Early results are encouraging, as targeted approaches like brentuximab vedotin in SLE and SSc have so far shown

favorable safety profiles alongside efficacy signals [

48].

In summary, ADC technology is poised to expand beyond oncology and offers a

novel therapeutic avenue in autoimmunity. By coupling the specificity of biologic agents with the potent effector function of small-molecule or oligonucleotide payloads, ADCs can intervene in autoimmune pathogenesis with high precision. Each of the ADCs reviewed—from steroid-loaded antibodies to immune cell-directed immunotoxins-illustrates a strategy to improve treatment outcomes and reduce systemic side effects in autoimmune diseases. As these biologics progress through preclinical optimization and clinical trials, they hold the promise of ushering in more targeted and tolerable therapies for conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, multiple sclerosis, and beyond. The developmental stage of these ADCs varies, but collectively they demonstrate the feasibility and potential impact of ADCs in modulating the immune system. With ongoing refinements in antibody engineering, linker design, and payload selection, ADCs may become a key component of the future autoimmune disease therapy arsenal, offering patients more effective disease control with fewer adverse effects [

36].

7. Biospecific Antibodies used in the treatment of Autoimmune Diseases

7.1 Bispecific Antibodies (bsAbs) Are Engineered Antibodies

Bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) are engineered antibodies that can simultaneously bind two different antigens or epitopes [

56]. Unlike traditional monoclonal antibodies, which have two identical binding sites for the same target, bispecific antibodies have two distinct binding sites, allowing them to bridge two different cells or molecules [

57]. In autoimmune diseases, bispecific antibodies are designed to modulate immune responses by targeting key immune pathways, offering more precise therapeutic effects compared to conventional monoclonal antibodies [

58].

Bispecific antibodies are produced using several advanced biotechnological methods. Some are generated by chemically linking two different monoclonal antibodies, while others are created through recombinant DNA technology, where genes encoding two distinct binding sites are inserted into a single cell line. Common formats include dual-variable domain immunoglobulins (DVD-Ig), tandem single-chain variable fragments (scFv), and IgG-like bispecifics [

59].

Most therapeutic bispecifics are based on IgG isotypes, particularly IgG1, due to its stability, long half-life, and ability to mediate immune effector functions if needed. Modifications to Fc regions are often made to enhance stability, reduce immunogenicity, or control effector functions [

60]. Advances in bispecific antibody engineering have enabled the production of highly stable and effective molecules suitable for clinical use.

Table 3 shows some examples of bsAbs used in autoimmune diseases.

7.2. Limitations and Challenges

- ▪

Limited Approvals: Most bispecific antibodies for autoimmunity are still in clinical trials, with only a few (like Telitacicept) approved outside the U.S [

65].

- ▪

Risk of Infection: Because B cells are critical for normal immune defense, excessive suppression can increase infections (e.g., bacterial, viral) [

66].

- ▪

Immunogenicity: Bispecific structures can sometimes provoke immune reactions against the drug itself [

67].

- ▪

Complex Manufacturing: Producing stable, safe bispecific antibodies is more technically challenging and costly than monoclonals [

68].

- ▪

Efficacy in Heterogeneous Diseases: Autoimmune diseases like lupus are highly variable, making it hard to find “one-size-fits-all” therapies [

69].

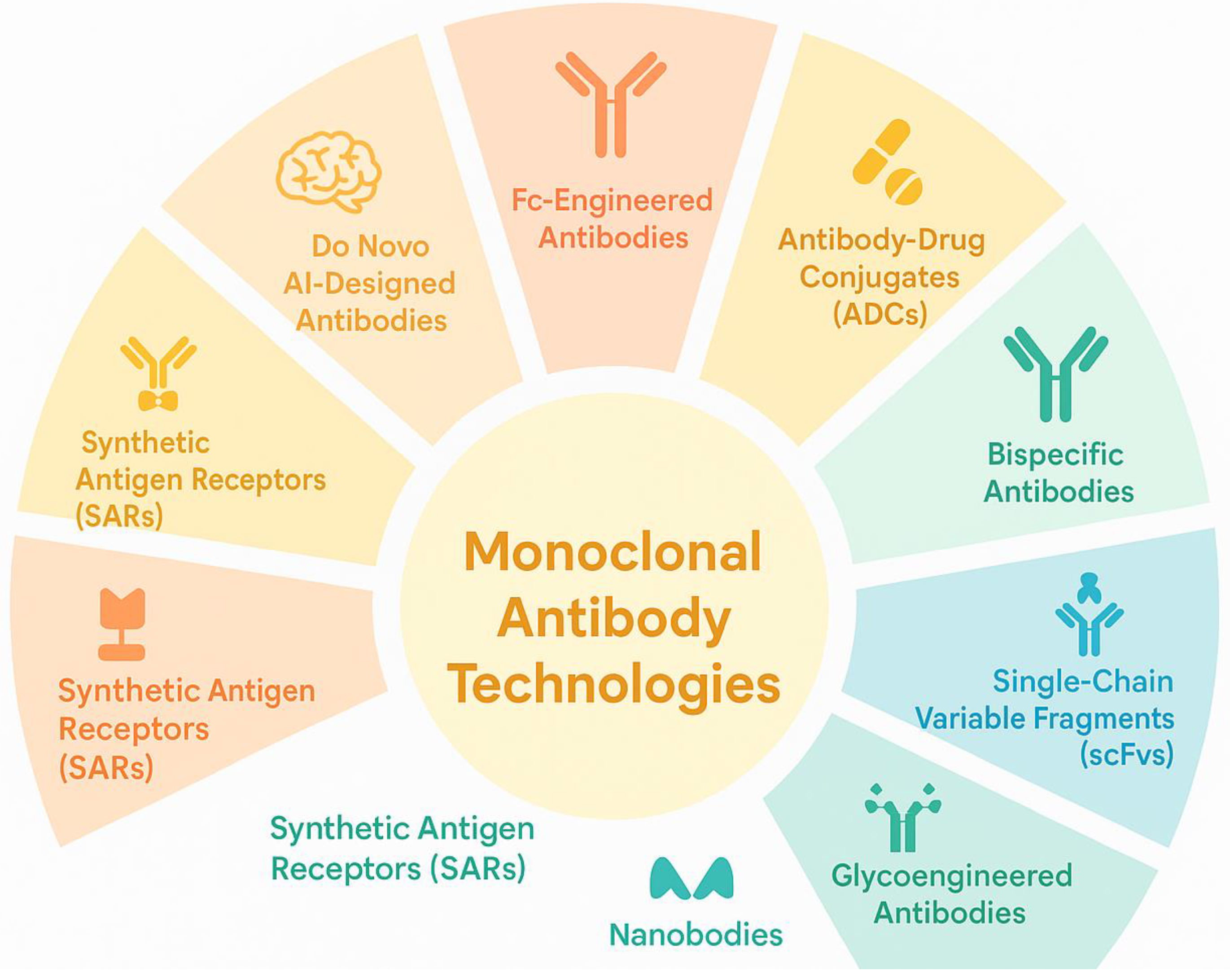

8. Monoclonal Antibodies Technologies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have revolutionized medicine through their roles in diagnostics, prevention, and treatment, including for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis. Originally developed using hybridoma technology—a method that fuses B lymphocytes with myeloma cells to generate antigen-specific mAbs—the field has advanced significantly. Multiple next-generation methodologies now complement or surpass this classical approach. These include electrofusion, B cell immortalization, and a variety of display platforms such as phage, yeast, ribosome, bacterial, and mammalian systems. Innovations like single B cell isolation, DNA/RNA-encoded antibody platforms, transgenic animal models, and artificial intelligence (AI)–driven antibody design have greatly improved the speed, specificity, and adaptability of mAb development, making them especially valuable for targeting dysregulated immune components in autoimmune conditions [

70].

Figure 2 shows some of the monoclonal antibody technologies.

In parallel, novel antibody formats like single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), nanobodies, bispecific antibodies, Fc-engineered variants, biosimilars, antibody mimetics, and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have enabled more targeted therapies for cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases. A particularly promising advancement in this spectrum is the development of synthetic antigen receptors (SARs). Like chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), SARs exhibit high antigen specificity but offer additional advantages, including modular designs that allow conditional activation, reduced off-target effects, and compatibility with non-viral delivery platforms. Importantly, SARs are being explored not only in oncology but also in the management of autoimmune diseases and chronic infections. Their increasing relevance reflects a shift toward more adaptable and controllable antibody-based therapies. Thus, SARs stand at the forefront of immunotherapy innovation, representing a transformative leap within the expanding landscape of monoclonal antibody technologies [

71,

72,

73].

9. Conclusions

Antibody–drug conjugates represent a novel and highly promising approach to autoimmune disease therapy, essentially

bridging the gap between traditional biologics and conventional immunosuppressants. By marrying the specificity of antibodies with the potent action of drugs, ADCs can address the longstanding unmet need for targeted yet effective treatments in disorders like RA, SLE, and others [

34,

35]. The recent progress in both preclinical and clinical realms—from early experimental immunosuppressive ADCs in 2015 [

45] to ongoing clinical trials in rheumatic diseases—provides optimism that with continued innovation, many of the challenges (target selection, safety, and immunogenicity) can be overcome. If so, ADCs could usher in a new era of therapy that delivers lasting remission with fewer side effects, fundamentally improving the management of autoimmune diseases. Each incremental advance in this field, supported by accumulating research and clinical evidence, brings us closer to realizing the full potential of ADCs as precision medicines for autoimmune disorders [

34,

41]. Bispecific antibodies represent an exciting frontier in autoimmune disease treatment, aiming to achieve more selective immune modulation with potentially fewer side effects than traditional therapies. However, more research is needed to fully establish their long-term safety, efficacy, and optimal use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.-V.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Review & Editing, A.J.-V, S.S.; P.E.A, J.M.E, and C.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study is included within the manuscript and its referenced sources, ensuring comprehensive access to the relevant data for further examination and analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the West Indian Immunology Society (WIIS) for their invaluable assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, L.; Yin, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q.; Gao, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Xin, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, M.; et al. A rationally designed CD19 monoclonal antibody-triptolide conjugate for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 4560–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Pandit, B.R.; Unakal, C.; Vuma, S.; Akpaka, P.E. A Comprehensive Review About the Use of Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2025, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Vico, A.; Frazzei, G.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Tas, S.W. Targeting B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune diseases: From established treatments to novel therapeutic approaches. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2149675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Barbosa, O.A.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pandit, B.; Umakanthan, S.; Akpaka, P.E. Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Molecules Involved in Its Imunopathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinato, M.C. Introduction to Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Antibodies 2021, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felten, R.; Scher, F.; Sibilia, J.; Chasset, F.; Arnaud, L. Advances in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: From back to the future, to the future and beyond. Jt. Bone Spine 2019, 86, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 4025–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xiao, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3889–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamkundu, S.; Liu, C.F. Lysosomal-Cleavable Peptide Linkers in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantasinghar, A.; Sunildutt, N.P.; Ahmed, F.; Soomro, A.M.; Salih, A.R. C.; Parihar, P. . & Choi, K.H. A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of antibody drug conjugate. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 161, 114408. [Google Scholar]

- Holborough-Kerkvliet, M.D.; Kroos, S.; van de Wetering, R.; Toes, R.E.M. Addressing the key issue: Antigen-specific targeting of B cells in autoimmune diseases. Immunol. Lett. 2023, 259, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, F.; Dal Bo, M.; Macor, P.; Toffoli, G. A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: From the conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1274088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: The “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickens, C.J.; Christopher, M.A.; Leon, M.A.; Pressnall, M.M.; Johnson, S.N.; Thati, S. . & Berkland, C. Antigen-drug conjugates as a novel therapeutic class for the treatment of antigen-specific autoimmune disorders. Molecular pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar]

- Velikova, T.; Sekulovski, M.; Bogdanova, S.; Vasilev, G.; Peshevska-Sekulovska, M.; Miteva, D.; Georgiev, T. Intravenous Immunoglobulins as Immunomodulators in Autoimmune Diseases and Reproductive Medicine. Antibodies 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, K. CD19: A promising target for systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1454913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expanding New Trends and Technologies in ADC Therapeutics. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/whitepaper/20250218/Expanding-new-trends-and-technologies-in-ADC-therapeutics.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- McPherson, M.J.; Hobson, A.D. Pushing the Envelope: Advancement of ADCs Outside of Oncology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2078, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemlinger, S.M.; Cambier, J.C. Therapeutic tactics for targeting B lymphocytes in autoimmunity and cancer. Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 54, 2249947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Burrows, P.D.; Wang, J.Y. Burrows, P.D.; Wang, J.Y. B cell development and maturation. In B Cells in Immunity and Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Cheng, Q.; Laurent, S.A.; Thaler, F.S.; Beenken, A.E.; Meinl, E.; Krönke, G.; Hiepe, F.; Alexander, T. B-Cell Maturation Antigen (BCMA) as a Biomarker and Potential Treatment Target in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarbati, S.; Benfaremo, D.; Viola, N.; Paolini, C.; Svegliati Baroni, S.; Funaro, A.; Moroncini, G.; Malavasi, F.; Gabrielli, A. Increased expression of the ectoenzyme CD38 in peripheral blood plasmablasts and plasma cells of patients with systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1072462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazzei, G.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; de Jong, B.A.; Siegelaar, S.E.; van Schaardenburg, D. Preclinical Autoimmune Disease: A Comparison of Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Multiple Sclerosis and Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 899372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zian, Z.; Anka, A.U.; Abdullahi, H.; Bouallegui, E.; Maleknia, S.; Azizi, G. Chapter 12—Clinical efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies in autoimmune diseases. In Breaking Tolerance to Antibody-Mediated Immunotherapy, Resistance to Anti-CD20 Antibodies and Approaches for Their Reversal; William, C.S.C., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024; Volume 2, ISBN 9780443192005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.J.; Fox, R.; Dörner, T.; Mariette, X.; Papas, A.; Grader-Beck, T.; Fisher, B.A.; Barcelos, F.; De Vita, S.; Schulze-Koops, H.; et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous ianalumab (VAY736) in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Hernández, J.; Ignatenko, S.; Gordienko, A.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Romanowska-Prochnicka, K.; Shen, N.; Ciferská, H.; Kodera, M.; Wei, J.C.C.; et al. POS0120 safety and efficacy of subcutaneous (SC) dose ianalumab (VAY736; anti-Baffr mAb) administered monthly over 28 weeks in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, W.; Carsillo, M.; Yuan, J.; Idamakanti, N.; Wagoner, M.; Shi, P.; Q. ; X.C.; Glennda, S.; Lachy, M.; Jonathan, Z.; et al. A reduction in B, T, and natural killer cells expressing CD38 by TAK-079 inhibits the induction and progression of collagen-induced arthritis in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, E.R.; Zhao, L.; Koch, A.; Smithson, G.; Estevam, J.; Chen, G.; Lahu, G.; Roepcke, S.; Lin, J.; Mclean, L. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the anti-CD38 cytolytic antibody TAK-079 in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, B.; McPherson, M.; Hernandez, A.; Goess, C.; Mathieu, S.; Waegell, W.; Bryant, S.; Hobson, A.; Ruzek, M.; Pang, Y.; et al. POS0365 anti-TNF glucocorticoid receptor modulator antibody drug conjugate for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, M.A.; Klodowska-Duda, G.; Maciejowski, M.; Potemkowski, A.; Li, J.; Patra, K.; Wesley, J.; Madani, S.; Barron, G.; Katz, E.; et al. Safety and tolerability of inebilizumab (MEDI-551), an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody, in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis: Results from a phase 1 randomised, placebo-controlled, escalating intravenous and subcutaneous dose study. Mult. Scler. 2019, 25, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, M.; Manabe, S.; Matsumura, Y. Immunoregulation by IL-7R-targeting antibody-drug conjugates: Overcoming steroid-resistance in cancer and autoimmune disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Braunstein, Z.; Chen, J.; Wei, Y.; Rao, X.; Dong, L.; Zhong, J. Precision Medicine in Rheumatic Diseases: Unlocking the Potential of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Roy, P.; Jirvankar, P. Antibody-Drug Conjugates vs. Traditional Biologics: A Comparative Analysis of Rheumatic Disease Management. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2025, 15, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, L.B.; Bule, P.; Khan, W.; Chella, N. An Overview of the Development and Preclinical Evaluation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Non-Oncological Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, D.; Yang, J.; Salam, M.A.; Sengupta, S.; Al-Amin, Y.; Mustafa, S.; Khan, M.A.; Huang, X.; Pawar, J.S. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: The Paradigm Shifts in the Targeted Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1203073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, T.; Vaidya, A.; Ravindran, S. Therapeutic potential of antibody–drug conjugates possessing bifunctional anti-inflammatory action in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hua, H. An immunomodulatory antibody–drug conjugate targeting BDCA2 strongly suppresses plasmacytoid dendritic cell function and glucocorticoid responsive genes. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Codina, A.; Nevskaya, T.; Baron, M.; Appleton, C.T.; Cecchini, M.J.; Philip, A.; El-Shimy, M.; Vanderhoek, L.; Pinal-Fernández, I.; E Pope, J. Brentuximab vedotin for skin involvement in refractory diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: An open-label trial. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, L.; Chen, J.Y.; Singh, R.; Baldwin, W.M.; Fox, D.A.; Lindner, D.J.; Martin, D.F.; Caspi, R.R.; Lin, F. A CD6-targeted antibody–drug conjugate as a potential therapy for T cell-mediated disorders. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e172914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F.; Aelion, J.; Rojkovich, B.; Zubrzycka-Sienkiewicz, A.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Arikan, D.; Ronilda, D.; Pang, Y.; Kupper, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of ABBV-3373, a Novel Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Antibody–Drug Conjugate, in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis Despite Methotrexate Therapy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Phase IIa Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharopoulos, C.; Lialios, P.-P.; Samarkos, M.; Gogas, H.; Ziogas, D.C. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Functional Principles and Applications in Oncology and Beyond. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmettler, S.; Ong, M.S.; Farmer, J.R.; Choi, H.; Walter, J. Hypogammaglobulinemia, late-onset neutropenia, and infections following rituximab therapy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 130, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.E.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Du, J.; Luo, X.; Deshmukh, V.; Kim, C.H.; Lawson, B.R.; Tremblay, M.S.; et al. An immunosuppressive antibody–drug conjugate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3229–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandish, P.E.; Palmieri, A.; Antonenko, S.; Beaumont, M.; Benso, L.; Cancilla, M.; Cheng, M.; Fayadat-Dilman, L.; Feng, G.; Figueroa, I.; et al. Development of Anti-CD74 Antibody–Drug Conjugates to Target Glucocorticoids to Immune Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtehaj, N.; Huda, R. High-dose BAFF receptor specific mAb-siRNA conjugate generates Fas-expressing B cells in lymph nodes and high-affinity serum autoantibody in a myasthenia mouse model. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 176, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Codina, A.; Nevskaya, T.; Pope, J. OP0172 Brentuximab Vedontin for Skin Involvement in Refractory Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis, Interim Results of a Phase IIB Open-Label Trial. BMJ 2021, 80, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Bhang, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.; Hahn, S.K. Tocilizumab–alendronate conjugate for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017, 28, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Tsuneyoshi, Y.; Matsushita, K.; Sunahara, N.; Matsuda, T.; Yoshida, H.; Komiya, S.; Onda, M.; Matsuyama, T. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of a recombinant immunotoxin against folate receptor β on the activation and proliferation of rheumatoid arthritis synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 2006, 54, 3126–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, G.; Scheinman, R.I.; Holers, V.M.; Banda, N.K. A new approach for the treatment of arthritis in mice with a novel conjugate of an anti-C5aR1 antibody and C5 small interfering RNA. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5446–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Olsen, O.; D’Souza, C.; Shan, J.; Zhao, F.; Yanolatos, J.; Hovhannisyan, Z.; Haxhinasto, S.; Delfino, F.; Olson, W. Development of Novel Glucocorticoids for Use in Antibody-Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 11958–11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.B. Brentuximab Vedotin Enters Phase 2 Trials & More. 2015. Available online: https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/brentuximab-vedotin-enters-phase-2-trials-more/#:~:text=drug%20conjugate%20,1 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Leung, D.; Wurst, J.M.; Liu, T.; Martinez, R.M.; Datta-Mannan, A.; Feng, Y. Antibody Conjugates-Recent Advances and Future Innovations. Antibodies 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ji, M.; Xiao, P.; Gou, J.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y. Glucocorticoids-based prodrug design: Current strategies and research progress. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, U.; Kontermann, R.E. Bispecific antibodies. Science 2021, 372, 916–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Er Saw, P.; Song, E. Challenges and strategies for next-generation bispecific antibody-based antitumor therapeutics. Cellular & molecular immunology 2020, 17, 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Udeabor, S.E. Monoclonal Antibodies in Modern Medicine: Their Therapeutic Potential and Future Directions. Trends in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 2024, 2, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, T.; Krah, S.; Sellmann, C.; Zielonka, S.; Doerner, A. Greatest hits—innovative technologies for high throughput identification of bispecific antibodies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the "biological missile" for targeted cancer therapy. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, H.; Wei, J.; Wu, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, X. . & Kong, F. Telitacicept in combination with B-cell depletion therapy in MuSK antibody-positive myasthenia gravis: a case report and literature review. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1456822. [Google Scholar]

- Abuqayyas, L.; Chen, P.W.; Dos Santos, M.T.; Parnes, J.R.; Doshi, S.; Dutta, S.; Houk, B.E. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties of Rozibafusp Alfa, a bispecific inhibitor of BAFF and ICOSL: analyses of phase I clinical trials. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2023, 114, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chasov V, Zmievskaya E, Ganeeva I, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus therapeutic strategy: From immunotherapy to gut microbiota modulation. J Biomed Res 2024. [CrossRef]

- Merino-Vico, A.; Frazzei, G.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Tas, S.W. Targeting B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune diseases: From established treatments to novel therapeutic approaches. European journal of immunology 2023, 53, 2149675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, Q. The Latest Progress in the Application of Telitacicept in Autoimmune Diseases. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2024, 5811–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Mikkelsen, H.; Jungersen, G. Intracellular pathogens: host immunity and microbial persistence strategies. Journal of immunology research 2019, 1356540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorovits, B.; Peng, K.; Kromminga, A. Current considerations on characterization of immune response to multi-domain biotherapeutics. BioDrugs 2020, 34, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amash, A.; Volkers, G.; Farber, P.; Griffin, D.; Davison, K.S.; Goodman, A. ;... & Jacobs, T. (2024, December). Developability considerations for bispecific and multispecific antibodies. In MAbs (Vol. 16, No. 1, p. 2394229). Taylor & Francis.

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Soodeen, S.; Gopaul, D.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Thompson, R.; Unakal, C.; Akpaka, P.E. Tackling Infectious Diseases in the Caribbean and South America: Epidemiological Insights, Antibiotic Resistance, Associated Infectious Diseases in Immunological Disorders, Global Infection Response, and Experimental Anti-Idiotypic Vaccine Candidates Against Microorganisms of Public Health Importance. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pooransingh, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Asin-Milan, O.; Akpaka, P.E. Advancements in Immunology and Microbiology Research: A Comprehensive Exploration of Key Areas. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chandley, P.; Rohatgi, S. Recent advances in the development of monoclonal antibodies and next-generation antibodies. Immunohorizons 2023, 7, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Cui, T.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W. Programmable synthetic receptors: the next-generation of cell and gene therapies. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla-Soto, J.; Sadelain, M. Synthetic HLA-independent T cell receptors for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi, B.; Muthugounder, S.; Jambon, S.; Tibbetts, R.; Hung, L.; Bassiri, H.; et al. Preclinical assessment of the efficacy and specificity of GD2-B7H3 SynNotch CAR-T in metastatic neuroblastoma. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).