Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

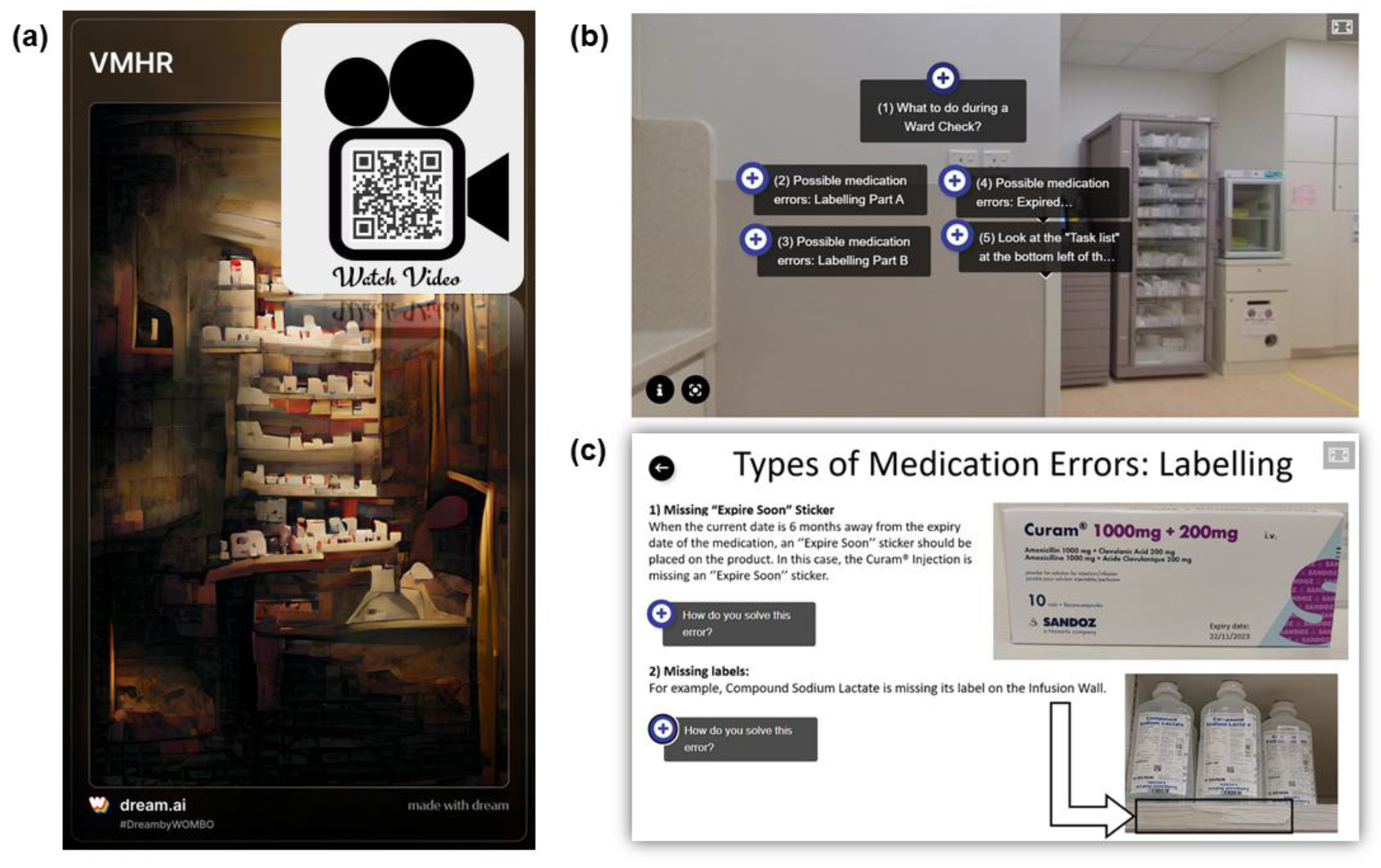

2.1. Design and Development of the Virtual Medication Horror Room (VMHR)

2.2. VMHR Pilot User Experience Study

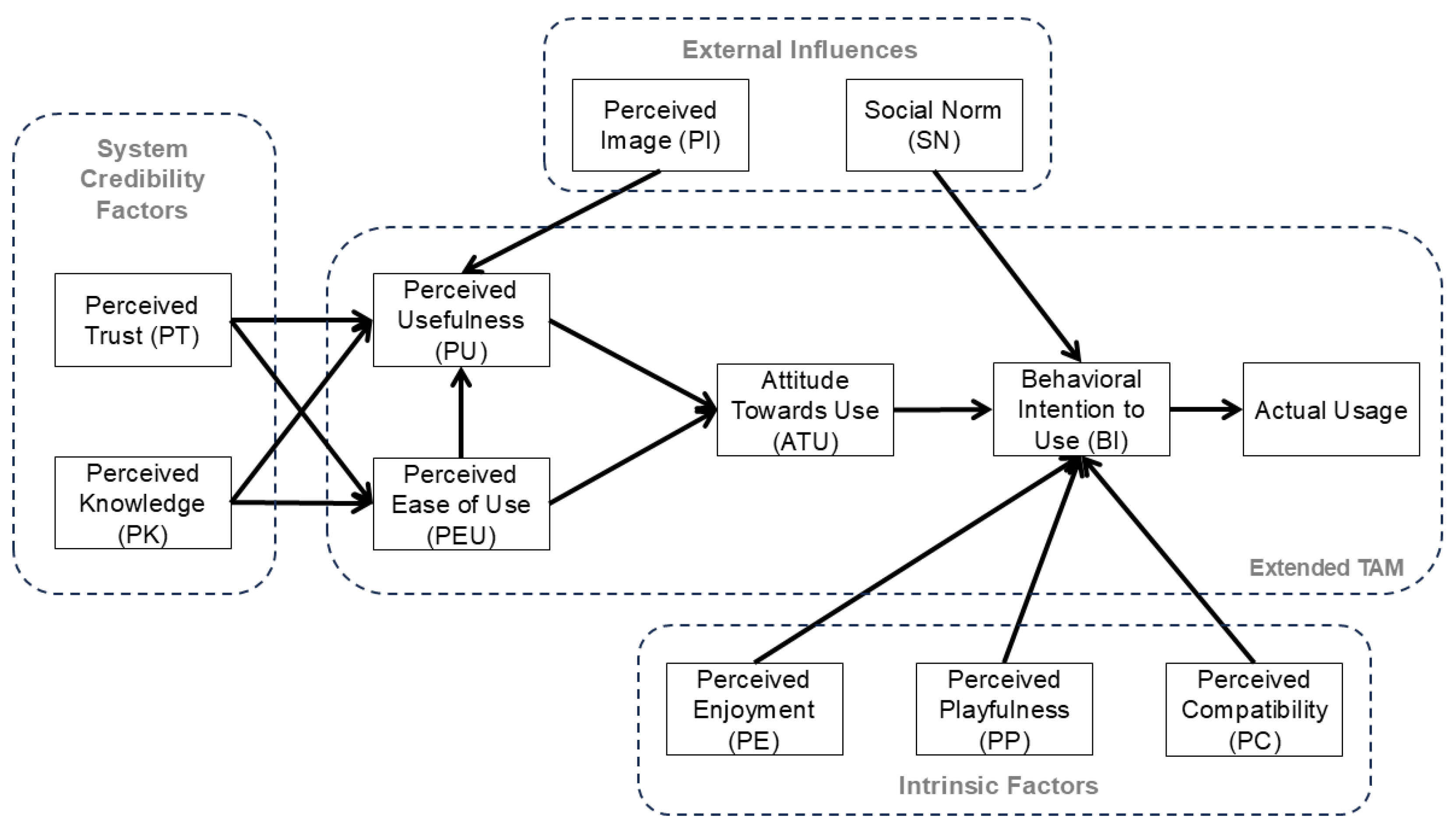

2.2.1. TAM Model

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The VMHR Training Program on Medication Safety in NPSAs

3.2. Pilot Study Results

3.2.1. Demographics of Participants

3.2.2. Participants’ Medication Safety Knowledge and Perceptions of the VMHR Content

3.2.3. Reliability of TAM Scale

3.2.4. Participants’ Perceptions and User Experience of VMHR

3.2.5. Associations of TAM Measures with Participants’ Prior Experience and Interest with Immersive Technologies, and Usefulness of VMHR Content

3.2.6. Correlation of TAM Measures with Participants’ Behavioral Intention to Use VMHR

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruutiainen, H.K.; Kallio, M.M.; Kuitunen, S.K. Identification and safe storage of look-alike, sound-alike medicines in automated dispensing cabinets. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2021, 28, e151–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neoh, C.F.; Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Awaisu, A.; Tambyappa, J. Compliance towards dispensed medication labelling standards: a cross-sectional study in the state of Penang, Malaysia. Curr Drug Saf 2009, 4, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of health Singapore; Singapore Pharmacy Board. Medication Safety Practice Guidelines & Tools; Ministry of Health Singapore: Singapore, 2006, pp. 1-85. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/medication-safety.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Safe selection and storage of medicines, 2022. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/safer-naming-labelling-and-packaging-medicines/safe-selection-and-storage-medicines (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professional guidance on the safe and secure handling of medicines. Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2022. Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/setting-professional-standards/safe-and-secure-handling-of-medicines/professional-guidance-on-the-safe-and-secure-handling-of-medicines (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Gray, R.C.F.; Hogerzeil, H.V.; Prüss, A.M.; Rushbrook, P. Guidelines for safe disposal of unwanted pharmaceuticals in and after emergencies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999, pp. 1-32.

- Cierniak, K.H. Integrating packaging, storage, and disposal options into the medication use system. US Food & Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/109538/download (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Cello, R.; Conley, M.; Cooley, T.; De la Torre, C.; Dorn, M.; Ferer, D.S.; Nickman, N.A.; Tjhio, D.; Urbanski, C.; Volpe, G. ASHP guidelines on the safe use of automated dispensing cabinets. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2022, 79, e71–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, H.H.; Abdullah, R.B.; Cally Yin Fang, C.; Leow, S. Singapore General Hospital inpatient ward check report (March 2022): Singapore, 2022, pp. 1-19.

- Farnan, J.M.; Gaffney, S.; Poston, J.T.; Slawinski, K.; Cappaert, M.; Kamin, B.; Arora, V.M. Patient safety room of horrors: A novel method to assess medical students and entering residents’ ability to identify hazards of hospitalisation. BMJ Qual Saf 2016, 25, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C.; Fridrich, A.; Schwappach, D.L.B. Training situational awareness for patient safety in a room of horrors: An evaluation of a low-fidelity simulation method. J Patient Saf 2021, 17, e1026–e1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daupin, J.; Atkinson, S.; Bedard, P.; Pelchat, V.; Lebel, D.; Bussieres, J.F. Medication errors room: A simulation to assess the medical, nursing and pharmacy staffs’ ability to identify errors related to the medication-use system. J Eval Clin Pract 2016, 22, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löber, N.; Garske, C.; Rohe, J. Room of horrors: A low-fidelity simulation practice for patient safety-relevant hazards of hospitalization. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2020, 153-154, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenbaum, H.; Gordon, L.; Brezis, M.; Porat, N. The use of a standard design medication room to promote medication safety: Organizational implications. Int J Qual Health Care 2013, 25, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiest, K.; Farnan, J.; Byrne, E.; Matern, L.; Cappaert, M.; Hirsch, K.; Arora, V. Use of simulation to assess incoming interns’ recognition of opportunities to choose wisely. J Hosp Med 2017, 12, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, W.Y.; Fan, P.; Raj, S.D.H.; Tan, Z.J.; Lee, I.Y.Y.; Boo, I.; Yap, K.Y.-L. Development of a three-dimensional (3D) virtual reality apprenticeship program (VRx) for training of medication safety practices. Int J Dig Health 2022, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Granić, A. The Technology Acceptance Model - 30 Years of TAM; Springer Cham: Switzerland AG, 2024; pp. 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharhan, A.; Salloum, S.A.; Aburayya, A. Technology acceptance drivers for AR smart glasses in the middle east: A quantitative study. Int J Data Netw Sci 2022, 6, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toraman, Y.; Gecit, B.B. User acceptance of metaverse: An analysis for e-commerce in the framework of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Sosyoekonomi 2023, 31, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, l. Measuring Technology Acceptance Model to use metaverse technology in Egypt. JSST 2022, 23, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr., J. F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson College Div: USA, 2009; p. 785. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to predict university students’ intentions to use metaverse-based learning platforms. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granić, A. Technology acceptance and adoption in education. In Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education; Zawacki-Richter, O., Jung, I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023, pp. 183-197.

- Kemp, A.; Palmer, E.; Strelan, P.; Thompson, H. Exploring the specification of educational compatibility of virtual reality within a technology acceptance model. Australasian J Educ Technol 2022, 38, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.; Ng, C.L.; Han, J.; Tsang, W.Y.; Fan, P.; Raj, S.D.H. Immersive training for sterile drug preparation through extended reality: Insights into the Virtual Aseptic Compounding (VAC) Programme, 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382636915_Immersive_Training_for_Sterile_Drug_Preparation_through_Extended_Reality_Insights_into_the_Virtual_Aseptic_Compounding_VAC_Programme (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Yap, K.Y.-L.; Ho, J.; Toh, P.S.T. Development of a Metaverse Art Gallery of Image Chronicles (MAGIC) for healthcare education: A digital health humanities approach to patients’ medication experiences. Information 2024, 15, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Tan, S.; Yap, K. The Saltomachy War - A metaverse escape room on the War Against Salt. Stud Health Technol Inform 2024, 310, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yap, K.Y.; Raj, S.D.H. “I am Groot” – How to be a “Guardian” of the Pharmacy Eduverse (Vol. 4). In Proceedings of the The 32nd Singapore Pharmacy Congress, Singapore, 9 Sep, 2023.

- H5P. Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser. H5P Group, 2025. Available online: https://h5p.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

| Demographics of Participants | Number of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender: | |

| Male | 10 (30.3) |

| Female | 23 (69.7) |

| Age ranges: | |

| 30 years old or younger | 27 (81.8) |

| Older than 30 years old | 6 (18.2) |

| Designation: | |

| Pharmacist | 5 (15.2) |

| Pre-registration pharmacist | 16 (48.5) |

| Pharmacy technician | 10 (30.3) |

| Pharmacy assistant | 2 (6.1) |

| Field of study: | |

| Pharmacy | 26 (78.8) |

| Pharmaceutical science | 4 (12.1) |

| Others | 3 (9.1) |

| Highest education level: | |

| Pre-university | 9 (27.3) |

| University | 24 (72.7) |

| Workplace: | |

| Inpatient | 17 (51.5) |

| Outpatient & retail | 16 (48.5) |

| Working experience: | |

| No working experience | 6 (18.2) |

| Less than 1 year | 10 (30.3) |

| 1 year or more | 17 (51.5) |

| Type of practice experience: | |

| Local practice | 29 (87.9) |

| Overseas practice | 4 (12.1) |

| Types of immersive technologies used prior to VMHR training a | |

| Augmented reality | 13 (39.4) |

| Augmented virtuality | 7 (21.2) |

| Virtual reality | 14 (42.4) |

| Mirror worlds | 12 (36.4) |

| 360-degree video/image applications | 12 (36.4) |

| Frequency of using extended reality applications: | |

| Never used before | 15 (45.5) |

| Not used in the past 6 months | 12 (36.4) |

| Used at least once in the past 6 months | 6 (18.2) |

| Frequency of using 360-degree video/image applications: | |

| Never used before | 14 (42.4) |

| Not used in the past 6 months | 15 (45.5) |

| Used at least once in the past 6 months | 4 (12.1) |

| Quiz Categories | Pre-quiz Scores (%) Mean ± SD (Median, IQR) |

Post-quiz Scores (%) Mean ± SD (Median, IQR) |

P-values a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency kit errors | 48.5 ± 22.2 (33.3, 33.3 – 66.7) |

65.7 ± 22.8 (66.7, 50.0 – 66.7) |

0.003* |

| Expired medications | 78.8 ± 24.0 (80.0, 60.0 – 100.0) |

87.9 ± 15.8 (100.0, 80.0 – 100.0) |

0.022* |

| High-risk medications | 77.3 ± 30.8 (100.0, 50.0 – 100.0) |

77.3 ± 25.3 (100.0, 50.0 – 100.0) |

1.000 |

| Inspection process inconsistencies | 37.9 ± 25.1 (50.0, 0.0 – 50.0) |

48.5 ± 29.3 (50.0, 50.0 – 50.0) |

0.071 |

| Labeling errors | 48.0 ± 16.5 (50.0, 33.3 – 66.7) |

61.6 ± 18.4 (66.7, 50.0 – 83.3) |

0.013* |

| Medication storage hazards | 58.4 ± 16.1 (57.1, 42.9 – 71.4) |

65.4 ± 16.8 (71.4, 57.1 – 78.6) |

0.027* |

| Total quiz scores | 58.7 ± 9.0 (60.0, 52.0 – 68.0) |

68.6 ± 10.3 (68.0, 60.0 – 76.0) |

<0.001* |

| Content in VMHR | Number of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Sections that are useful in improving medication safety knowledge: | |

| 360-degree virtual tour | 19 (57.6) |

| Interactive assessment book | 16 (48.5) |

| “Find-the-Errors” spots quiz | 12 (36.4) |

| Rating of Content in VMHR: a | |

| Understanding types of medication storage errors: | |

| Informative b | 30 (90.9) |

| Not very informative c | 3 (9.1) |

| Understanding how to mitigate medication storage hazards: | |

| Informative b | 29 (87.9) |

| Not very informative c | 4 (12.1) |

| Understanding the equipment and tools needed to perform ward/clinic checks: | |

| Informative b | 26 (78.8) |

| Not very informative c | 7 (21.2) |

| Interest in using extended reality and/or 360-degree video/image technologies for training: | |

| Interested d | 21 (63.6) |

| Not very interested e | 12 (36.4) |

| Demographics of Participants | Score Improvements/differences from Pre-quiz to Post-quiz (%) (Median, IQR) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency kit errors | Expired medications | High-risk medications | Inspection process inconsistencies | Labeling errors | Medication storage hazards | Total quiz scores | |

| Gender: | |||||||

| Male | 33.3 (25.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 12.5) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

7.1 (-3.6, 14.3) |

10.0 (4.0, 12.0) |

| Female | 0.0 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (0.0, 16.0) |

| P-value a | 0.049* | 0.106 | 1.000 | 0.456 | 0.856 | 0.609 | 0.619 |

| Age ranges: | |||||||

| 30 years old or younger | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| Older than 30 years old | 16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

20.0 (-5.0, 40.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 12.5) |

25.0 (-12.5, 50.0) |

16.7 (-8.3, 20.8) |

0.0 (-14.3, 17.9) |

8.0 (3.0, 16.0) |

| P-value a | 0.878 | 0.196 | 0.367 | 0.548 | 0.647 | 0.367 | 0.868 |

| Designation: | |||||||

| Pharmacists | 0.0 (0.0, 33.0) |

0.0 (-20.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (-25.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (-25.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (-8.3, 33.3) |

14.3 (-14.3, 21.4) |

4.0 (-4.0, 14.0) |

| Pre-registration pharmacists | 33.0 (0.0, 33.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 15.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 22.0) |

| Pharmacy technicians & Pharmacy assistants | 16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

20.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 37.5) |

25.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

8.3 (-12.5, 16.7) |

0.0 (-14.3, 14.3) |

10.0 (1.0, 15.0) |

| P-value a | 0.655 | 0.028*,b | 0.091 | 0.319 | 0.321 | 0.270 | 0.408 |

| Field of study: | |||||||

| Pharmacy | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| Pharmaceutical science | 0.0 (-25.0, 25.0) |

0.0 (-15.0, 15.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 37.5) |

25.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

-8.3 (-16.7, 12.5) |

-7.1 (-25.0, 21.4) |

2.0 (-6.0, 7.0) |

| P-value a | 0.210 | 0.520 | 0.216 | 0.343 | 0.078 | 0.239 | 0.063 |

| Highest education level: | |||||||

| Pre-university | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

20.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 25.0) |

0.0 (-25.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (-16.7, 16.7) |

0.0 (-14.3, 14.3) |

8.0 (2.0, 14.0) |

| University | 16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| P-value a | 0.427 | 0.482 | 0.118 | 0.839 | 0.162 | 0.311 | 0.498 |

| Workplace: | |||||||

| Inpatient | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 25.0) |

14.3 (-14.3, 14.3) |

4.0 (0.0, 12.0) |

| Outpatient & retail | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

20.0 (0.0, 35.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (5.0, 19.0) |

| P-value a | 1.000 | 0.015* | 0.164 | 0.825 | 0.838 | 0.611 | 0.060 |

| Working experience: | |||||||

| No working experience | 33.3 (25.0, 66.7) |

0.0 (-5.0, 15.0) |

0.0 (-12.5, 0.0) |

0.0 (-12.5, 12.5) |

16.7 (12.5, 41.7) |

7.1 (-3.6, 14.3) |

12.0 (5.0, 24.0) |

| Less than 1 year | 16.7 (-33.3, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (-12.5, 12.5) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

8.3 (-4.2, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 17.9) |

8.0 (3.0, 18.0) |

| 1 year or more | 0.0 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

50.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 25.0) |

0.0 (-7.1, 14.3) |

12.0 (2.0, 14.0) |

| P-value a | 0.079 | 0.734 | 0.637 | 0.142 | 0.590 | 0.469 | 0.757 |

| Type of practice experience: | |||||||

| Local practice | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| Overseas practice | 33.3 (8.3, 33.3) |

20.0 (-10.0, 20.0) |

25.0 (-37.5, 50.0) |

-25.0 (-50.0, 37.5) |

8.3 (-25.0, 16.7) |

7.1 (-10.7, 25.0) |

8.0 (1.0, 12.0) |

| P-value a | 0.470 | 0.510 | 0.286 | 0.185 | 0.232 | 1.000 | 0.502 |

| Rating of Content in VMHR: a | |||||||

| Understanding types of medication storage errors: | |||||||

| Informative | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| Not very informative c | 33.3 (0.0, --) |

20.0 (0.0, --) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (-50.0, --) |

0.0 (0.0, --) |

0.0 (-28.6, --) |

4.0 (0.0, --) |

| P-value a | 0.707 | 0.185 | 1.000 | 0.624 | 0.722 | 0.280 | 0.751 |

| Understanding how to mitigate medication storage hazards: | |||||||

| Informative | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 16.0) |

| Not very informative | 33.3 (8.3, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 15.0) |

0.0 (-37.5, 0.0) |

25.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

0.0 (-12.5, 12.5) |

0.0 (-25.0, 25.0) |

6.0 (1.0, 8.0) |

| P-value a | 0.470 | 0.834 | 0.286 | 0.355 | 0.117 | 0.584 | 0.198 |

| Understanding the equipment and tools needed to perform ward/clinic checks: | |||||||

| Informative | 33.3 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

0.0 (0.0, 12.5) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (3.0, 13.0) |

| Not very informative | 0.0 (0.0, 33.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 20.0) |

0.0 (-50.0, 0.0) |

50.0 (0.0, 50.0) |

16.7 (0.0, 33.3) |

14.3 (0.0, 14.3) |

12.0 (4.0, 24.0) |

| P-value a | 0.613 | 0.738 | 0.089 | 0.018* | 0.307 | 0.872 | 0.461 |

| TAM Measures | Number of Items/ Statements | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Knowledge (PK) | 2 | 0.969 |

| Perceived Trust (PT) | 3 | 0.928 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 3 | 0.796 |

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | 4 | 0.722 |

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | 2 | 0.844 |

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | 3 | 0.750 |

| Social Norm (SN) a | 3 | 0.499 |

| Perceived Image (PI) | 3 | 0.871 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) b | 4 | 0.638 |

| Attitude Towards Use (ATU) | 3 | 0.919 |

| Behavioral Intention (BI) | 3 | 0.856 |

| Overall Total | 33 | 0.951 |

| TAM Measures | TAM Items/Statements | Scores for TAM Statements (Mean ± SD) |

No. of Participants who agreed with statement (%), N=33 a | Scores for TAM Measures (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Knowledge (PK) |

|

5.64 ± 1.41 | 28 (84.8) | 5.58 ± 1.37 |

|

5.52 ± 1.37 | 28 (84.8) | ||

| Perceived Trust (PT) |

|

5.61 ± 0.93 | 28 (84.8) | 5.55 ± 0.81 |

|

5.48 ± 0.87 | 28 (84.8) | ||

|

5.55 ± 0.79 | 29 (87.9) | ||

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

|

5.67 ± 0.92 | 31 (93.9) | 5.44 ± 0.87 |

|

5.33 ± 1.14 | 27 (81.8) | ||

|

5.33 ± 1.02 | 26 (78.8) | ||

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) |

|

5.52 ± 1.00 | 29 (87.9) | 5.35 ± 0.86 |

|

4.85 ± 1.56 | 24 (72.7) | ||

|

5.79 ± 0.86 | 31 (93.9) | ||

|

5.24 ± 1.12 | 23 (69.7) | ||

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) |

|

5.27 ± 1.26 | 27 (81.8) | 5.32 ± 1.07 |

|

5.36 ± 1.03 | 28 (84.8) | ||

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) |

|

4.97 ± 1.40 | 24 (72.7) | 5.25 ± 1.00 |

|

4.94 ± 1.39 | 22 (66.7) | ||

|

5.85 ± 0.76 | 31 (93.9) | ||

| Social Norm (SN) |

|

5.73 ± 0.88 | 29 (87.9) | 5.24 ± 0.89 |

|

5.30 ± 1.05 | 26 (78.8) | ||

|

4.70 ± 1.70 | 22 (66.7) | ||

| Perceived Image (PI) |

|

5.12 ± 1.02 | 22 (66.7) | 5.09 ± 1.03 |

|

4.82 ± 1.33 | 21 (63.6) | ||

|

5.33 ± 1.08 | 23 (69.7) | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) |

|

5.73 ± 1.01 | 31 (93.9) | 4.65 ± 0.83 |

|

4.82 ± 1.38 | 23 (69.7) | ||

|

2.76 ± 1.17 | 25 (75.8) | ||

|

5.30 ± 1.19 | 27 (81.8) | ||

| Attitude Towards Use (ATU) |

|

4.30 ± 1.36 | 14 (42.4) | 4.23 ± 1.21 |

|

4.30 ± 1.29 | 15 (45.5) | ||

|

4.09 ± 1.28 | 11 (33.3) | ||

| Behavioral Intention to Use (BI) |

|

5.61 ± 0.86 | 29 (87.9) | 5.34 ± 0.87 |

|

5.09 ± 1.10 | 25 (75.8) | ||

|

5.33 ± 0.99 | 26 (78.8) |

| Prior Experience and Interest in Immersive Technologies | Ratings of TAM Measures (Median, IQR) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK | PT | PU | PP | PE | PC | PI | PEU | ATU | BI | |

| Prior experiences with: | ||||||||||

| Augmented reality | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (5.3, 7.0) |

6.0 (4.7, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.6, 6.0) |

5.5 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.2, 5.8) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

4.5 (4.4, 5.0) |

3.7 (3.0, 5.0) |

5.7 (4.2, 6.0) |

| No | 6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.1, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.9 (4.8, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.2 (4.2, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 5.2) |

4.2 (3.1, 5.3) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.404 | 0.624 | 0.437 | 0.452 | 0.508 | 0.277 | 0.641 | 0.340 | 0.458 | 0.297 |

| Augmented virtuality | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (6.0, 7.0) |

6.0 (4.3, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.7, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.0, 6.0) |

4.5 (4.0, 5.0) |

3.3 (3.0, 5.0) |

5.7 (5.3, 6.0) |

| No | 6.0 (5.4, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.8 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.5 (4.9, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.6, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 5.1) |

4.2 (3.3, 5.1) |

5.7 (4.7, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.264 | 0.425 | 0.227 | 0.857 | 0.530 | 0.840 | 0.947 | 0.434 | 0.478 | 0.700 |

| Virtual reality | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (5.4, 7.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

5.3 (4.0, 5.8) |

4.9 (4.3, 5.8) |

5.3 (4.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (3.7, 5.7) |

4.0 (3.9, 5.7) |

4.5 (3.4, 5.0) |

4.3 (3.6, 5.1) |

5.2 (4.3, 5.7) |

| No | 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.7, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 5.3) |

4.0 (3.0, 5.0) |

6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.953 | 0.026* | 0.006* | 0.006* | 0.068 | 0.003* | 0.006* | 0.059 | 0.279 | 0.008* |

| Mirror worlds | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (5.3, 6.8) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.8, 6.0) |

5.4 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.8 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.1, 6.0) |

4.9 (4.3, 5.4) |

4.5 (3.0, 5.5) |

5.7 (5.1, 6.0) |

| No | 6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.8 (4.5, 6.0) |

5.5 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

4.8 (4.5, 5.0) |

4.0 (3.2, 5.0) |

5.7 (4.7, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.493 | 0.690 | 0.058 | 0.894 | 0.953 | 0.518 | 0.495 | 0.531 | 0.806 | 0.700 |

| 360-degree video/image applications | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (5.5, 6.8) |

5.7 (4.3, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.8 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.5 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 5.9) |

5.2 (4.0, 5.9) |

4.9 (4.5, 5.0) |

4.2 (3.4, 5.0) |

5.7 (4.8, 6.0) |

| No | 6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.5 (4.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.3, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

4.8 (4.4, 5.3) |

4.0 (3.0, 5.3) |

5.3 (4.8, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.600 | 0.175 | 0.407 | 0.804 | 0.782 | 0.954 | 0.663 | 0.924 | 0.985 | 0.863 |

| Interest in using extended reality and/or 360-degree video/image technologies for training: | ||||||||||

| Interested | 6.0 (6.0, 6.3) |

6.0 (5.2, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.7, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.4, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.7, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.5, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.8, 5.4) |

4.3 (3.2, 5.2) |

6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

| Not very interested | 5.3 (3.3, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 5.7) |

4.9 (4.3, 5.2) |

5.0 (3.3, 5.5) |

4.5 (3.7, 5.0) |

4.5 (3.8, 5.0) |

4.5 (3.3, 4.7) |

3.8 (3.0, 5.0) |

4.8 (4.1, 5.3) |

| P-value a | 0.009* | 0.661 | <0.001* | 0.002* | 0.001* | <0.001* | 0.018* | <0.001* | 0.365 | >0.001* |

| Sections that participants found useful in improving medication safety knowledge: | ||||||||||

| 360-degree virtual tour | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.7, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.7, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.7, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 5.0) |

4.0 (3.3, 5.0) |

6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

| No | 5.8 (3.8, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.1) |

5.0 (4.5, 6.0) |

4.8 (4.4, 6.0) |

5.0 (3.8, 5.6) |

4.8 (4.0, 5.8) |

4.7 (4.0, 5.8) |

4.6 (4.4, 5.1) |

4.3 (2.9, 5.1) |

5.0 (4.3, 5.8) |

| P-value a | 0.057 | 0.861 | 0.030* | 0.032* | 0.009* | 0.040* | 0.347 | 0.530 | 0.797 | 0.059 |

| Interactive assessment book | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.3, 6.0) |

5.8 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.8 (4.6, 6.0) |

5.5 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.8, 6.0) |

5.2 (4.0, 5.9) |

4.9 (4.5, 5.3) |

5.0 (3.8, 5.3) |

5.7 (4.8, 6.0) |

| No | 6.0 (4.5, 6.0) |

6.0 (4.7, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.8 (4.9, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.3, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

4.8 (4.1, 5.0) |

3.7 (3.0, 4.7) |

5.3 (4.7, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.322 | 0.145 | 0.775 | 0.912 | 0.955 | 0.453 | 0.675 | 0.315 | 0.067 | 0.553 |

| “Find-the-Errors” spots quiz | ||||||||||

| Yes | 5.3 (3.3, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.2, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.6, 6.0) |

5.0 (3.4, 6.0) |

5.3 (4.1, 5.9) |

5.0 (4.0, 5.9) |

4.5 (4.3, 4.9) |

4.0 (2.8, 4.8) |

5.3 (4.3, 5.7) |

| No | 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.8 (4.9, 6.0) |

6.0 (5.5, 6.0) |

5.7 (5.0, 6.0) |

5.7 (4.0, 6.0) |

5.0 (4.5, 5.1) |

4.3 (3.2, 5.3) |

6.0 (5.2, 6.0) |

| P-value a | 0.025* | 0.675 | 0.213 | 0.554 | 0.093 | 0.371 | 0.970 | 0.134 | 0.258 | 0.172 |

| TAM Measures a | Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient (rs) b | P-value | 95% Confidence Interval | Exploratory Factor Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Loadings | Factor 2 Loadings | Factor 3 Loadings | Extraction Communalities c | ||||

| Perceived Knowledge (PK) | 0.582 | <0.001* | 0.288, 0.775 | 0.950 | 0.068 | 0.179 | 0.995 |

| Perceived Trust (PT) | 0.387 | 0.026* | 0.039, 0.651 | 0.068 | 0.230 | 0.014 | 1.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 0.743 | <0.001* | 0.529, 0.868 | 0.610 | 0.458 | 0.320 | 0.997 |

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | 0.828 | <0.001* | 0.672, 0.914 | 0.565 | 0.555 | 0.155 | 0.986 |

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | 0.775 | <0.001* | 0.582, 0.886 | 0.840 | 0.191 | 0.231 | 0.964 |

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | 0.835 | <0.001* | 0.683, 0.917 | 0.532 | 0.516 | 0.444 | 0.937 |

| Perceived Image (PI) | 0.651 | <0.001* | 0.387, 0.816 | 0.119 | 0.911 | 0.154 | 0.992 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | 0.560 | <0.001* | 0.258, 0.762 | 0.299 | 0.187 | 0.896 | 0.997 |

| Attitude Towards Use (ATU) | 0.241 | 0.177 | -0.122, 0.547 | 0.207 | -0.042 | 0.148 | 1.000 |

| Behavioral Intention to Use (BI) | -- | -- | -- | 0.260 | 0.465 | 0.330 | 0.997 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).