1. Introduction

Most of the approximately 200 recognized

Mycobacterium species (

www.bacterio.net/mycobacterium.html, accessed on 17 March 2025) are environmental organisms collectively referred to as nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Some of these are opportunistic pathogens capable of causing chronic and severe infections in humans [

1,

2,

3]. The bacteria are ubiquitous in natural water sources, soils, and aerosols, with certain environmental and occupational activities increasing the risk of exposure [

4]. Municipal water and plumbing systems serve as major reservoirs for human infection, as NTM form biofilms that are highly resistant to eradication. Such biofilms pose a particular risk for high-risk populations, including immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, and those with chronic illnesses [

5,

6].

Pulmonary infections are the most common clinical manifestation of NTM disease, though lymphatic, cutaneous, and soft tissue infections, as well as disseminated disease, can also occur [

7,

8,

9]. Despite being recognized for over 70 years, NTM remain a significant global health concern [

10,

11]. Advances in isolation, culturing, and molecular identification techniques have led to a rapid expansion in the number of described

Mycobacterium species, creating new challenges for clinical management, particularly in selecting appropriate antimicrobial therapies. Treatment is further complicated by the intrinsic resistance and heterogeneous antimicrobial susceptibility profiles among different NTM species [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These factors highlight the critical need for precise identification, taxonomic classification, and comprehensive characterization of these emerging pathogens [

16,

17].

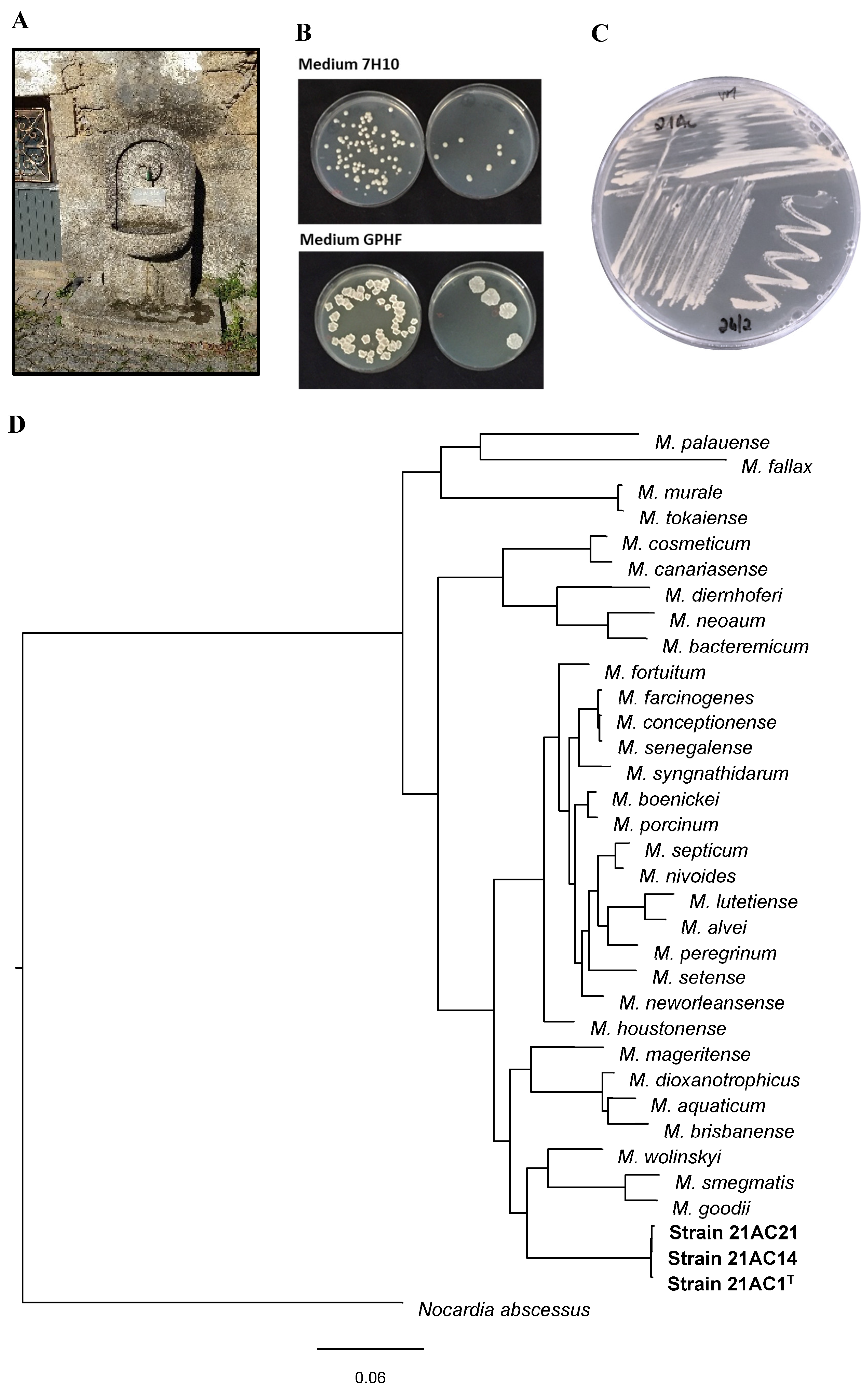

As part of an ongoing survey of NTM in water and biofilms from sources used by NTM-infected patients, samples were collected from a public water fountain and its runoff. This fountain had supplied drinking water to a rural community for several years and lies in close proximity to the home of a participant infected with a M. avium strain. Analysis of these samples yielded three morphologically identical colonies, designated 21AC1T, 21AC14, and 21AC21. Detailed phenotypic and genotypic and genotypic characterization confirmed that these isolates represent a novel species within the genus Mycobacterium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Sampling and Selective Isolation of Mycobacteria

Water samples were collected from the fountain (40.644510, -7.770130) using sterile containers. At the time of collection, the water temperature was 16ºC, and pH was 6.5. One litre was processed for the selective isolation of NTM, while an additional litre was used for chemical parameter analysis (CESAB, Portugal,

https://www.cesab.pt/). Samples were kept on ice packs and transported to the microbiology and chemistry laboratories within 6 hours to ensure sample integrity.

To prevent the overgrowth of contaminants and optimize the recovery of NTM from water samples, decontamination was performed using 0.005% cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), followed by incubation at room temperature for 20 min. Water samples (200 mL, processed in duplicate) were then filtered through 0.22 μm-pore size membranes [

18,

19]. The membranes were placed onto selective Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates: one supplemented with 1 mg/L malachite green and the other with a cocktail of antimicrobials (PANTA) [

20]. The plates were incubated at 30°C for up to 30 days, with daily monitoring for colony formation. Presumptive NTM colonies were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H10 agar for purification and further characterization.

2.2. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Genomic DNA of the three isolates was extracted and purified using the Microbial gDNA Isolation kit (NZYTech, Portugal), which includes an optimized mycobacterial cell lysis step [

21]. DNA concentration and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using universal primers 27F (5′-GAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1525R (5′–AGAAAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3′) with amplification performed using Supreme NZYTaq DNA polymerase (NZYTech, Portugal). The 16S rRNA gene and whole-genome sequences were obtained through sequencing at Eurofins Genomics (Germany). The 16S rRNA gene sequence was compared with available sequences in the NCBI database using the BLAST tool (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

2.3. Genomic Analysis and Genome Annotation

To determine the phylogenetic position of strains 21AC1

T, 21AC14, and 21AC21 within the genus

Mycobacterium, whole-genome sequencing was performed. Genomic libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT Library Preparation kit (Illumina), and sequencing was carried out on an Illumina MiSeq platform, generating 2×150-nt paired-end reads. For downstream analyses, MetaWRAP v1.3 [

22] was used. Quality trimming was performed with the sliding-window operation in TrimGalore v0.5.0 (

http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) using default parameters. Genome assembly was carried out using SPAdes v3.5.0 [

23] with default settings and k-mers of 33, 55, and 77 nt. The assembled genome was binned using MetaBat v2.12.1 [

24] with default parameters, and a quality assessment was performed using CheckM v1.0.12 [

25] under default settings.

2.4. Phenotypic analysis

Monitoring mycobacterial growth in liquid media can be challenging due to cell aggregation, which complicates turbidity measurements. This was mitigated by adding Tween 80 or glycerol to the medium [

26]. The ability of isolates 21AC1

T, 21AC14, and 21AC21 to grow on various solid media, including Middlebrook 7H10, GPHF agar (DSM 553), MacConkey agar without crystal violet, Columbia Agar with 5% sheep blood, and Lowenstein-Jensen slants, was assessed. Additionally, growth at different temperatures (20, 25, 30, 35, 40ºC) and in the presence of 2 or 5% NaCl was evaluated in Middlebrook 7H9 broth.

Strain 21AC1

T was tested for catalase and arylsulfatase activities, tellurite reduction, and Tween 80 hydrolysis [

27,

28]. Additional biochemical characteristics of all three isolates were assessed using API Coryne and API 20NE strips (BioMérieux) following the manufacturer’s instructions, with incubation at 35°C for 48 hours.

2.5. Mycolic and Fatty Acid Analyses (MIDI/GC-MS) and MALDI-TOF MS

The type strain 21AC1

T was cultivated on three Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates at 35ºC for 48 hours to obtain sufficient biomass for fatty acid and mycolic acid analysis, as well as MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. These analyses were conducted at the Identification Service of the Leibniz-Institut DSMZ - Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany, following the methodologies outlined at

www.dsmz.de/services/microorganisms/biochemical-analysis/cellular-fatty-acids.

2.6. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Susceptibility testing was performed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines for rapidly growing mycobacteria [

29,

30]. The antimicrobial agents tested included amikacin (Alfa Aesar), cefoxitin, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, imipenem, meropenem, minocycline, and tobramycin (all from Sigma), as well as linezolid (Acros Organics), moxifloxacin (TCI Chemicals), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Fluka). A culture suspension of each strain was prepared by harvesting colonies from Middlebrook 7H10 agar and resuspending them in 5 mL of saline solution to achieve a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard [

20]. The suspensions were vortexed vigorously for 20 s and subsequently diluted 1,000-fold before testing, which was conducted within 30 min. Susceptibility testing was performed in sterile 96-well microplates prefilled with Mueller Hinton (MH) medium supplemented with 0.5% OADC. Serial twofold dilution of each antimicrobial agent (from 128 to 0.125 μg/mL) were prepared in the wells. The plates were then inoculated with the diluted bacterial suspension. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that completely inhibited visible growth, indicated by the absence of a bacterial pellet at the bottom of the well. MICs were determined after 5 days of incubation at 30°C, except for clarithromycin, which was assessed after 7 days [

29,

31]. Appropriate controls were included to ensure normal bacterial growth, and all assays were performed in duplicate on two separate days to verify the reproducibility of results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sequence Identity and Phylogenetic Analysis

Initial analysis of the 1381-bp 16S rRNA gene sequence from strain 21AC1T showed 98.33% identity with M. neglectum CECT 8778, 98.19% with M. tusciae CIP 106367 and M. rufum JCM 16372, and 98.12% with M. gilvum SM 35. As previously reported, 16S rRNA gene sequencing alone often fails to achieve species-level discrimination within the Mycobacterium genus, a limitation also observed in this study.

The draft genome of strain 21AC1

T consisted of 7,617,360 bp, with a calculated DNA G+C content of 65.91% and an estimated completeness of 99.93%. The genomes of strains 21AC14 and 21AC21 were assembled to 7,658,160 bp and 7,661,220 bp, respectively (

Table S1). The estimated completeness of these genomes was 99.93% and 99.94%, respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the translated coding sequences (CDSs) of the type strains of

Mycobacterium (retrieved from the NCBI database) (

Table S2) and strains 21AC1

T, 21AC14, and 21AC21. The analysis was based on the comparison of amino acid sequences from 107 single-copy core genes using bcgTree v1.1.0 [

32]. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) calculations were performed against phylogenetically related genomes using the EzBioCloud ANI calculator [

33]. Phylogenetic analyses confirmed that strains 21AC1

T, 21AC14, and 21AC21 belong to the same species and are closely related to

M. wolinskyi, M. goodii, and

M. smegmatis (

Figure 1). The tree topology and branch lengths indicate that strain 21AC1

T represents a novel species within the genus

Mycobacterium. This conclusion is further supported by ANIb and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) results comparing the genome of strain 21AC1

T with those of its closest species relatives (

Table 1), and with strains 21AC14 and 21AC21 isolated from the same site (

Table S1). The ANI threshold for species delineation (95–96%) [

34] [

35] supports the classification of strain 21AC1

T as a distinct species, as it shares ANIb values of approximately 81% with its closest phylogenetic relatives (

Table 5). Furthermore, dDDH values between strain 21AC1

T and the type strains of

M. wolinskyi,

M. smegmatis, and

M. goodii were 23.6%, 22.1%, and 21.8%, respectively (

Table 1), which are well below the 70% threshold for species discrimination [

34]. The dDDH value among strains 21AC1

T, 21AC14, and 21AC21 was 100% (

Table S1), confirming their classification as members of the same species. Additionally, analysis using the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) further corroborated that the three isolates belong to a novel species within the genus

Mycobacterium.

3.2. Nucleotide and Genome Sequence Accession Numbers

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of Mycobacterium appelbergii strains 21AC1T, 21AC14 and 21AC21 have been deposited into GenBank under the accession numbers OP795714, PV139203 and PV130038, respectively. The assembled genomes of these three strains were annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genomes Annotation Pipeline (PGAP). The whole-genome shotgun (WGS) projects have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession numbers JAMQTH000000000, JBLKDU000000000 and JBLKDT000000000, respectively.

3.2. Chemical Analysis of the Water Source of Strain Isolation

The chemical composition and concentrations of selected metals and mineral salts in the water source are summarized in

Table 2, in accordance with established water-quality parameters. Previous studies have linked certain constituents, particularly molybdenum and calcium levels [

36], trace molybdenum and vanadium salts [

37], and the combined presence of molybdenum, vanadium and sulphate, to an increased incidence of NTM pulmonary infections, especially in cystic fibrosis patients [

38]. In the present work, the concentrations of molybdenum and vanadium fell well within the maximum limits set by both the German Environmental Protection Agency and the US Environmental Protection Agency for drinking water [

39,

40].

3.3. Physiological and Chemotaxonomic Analysis

Strain 21AC1

T grew in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 0.5% of glycerol across a temperature range of 20-35ºC, with optimal growth observed between 30 and 35ºC. A comparable optimal temperature range was identified for all three isolates cultured on solid Middlebrook 7H10 medium (

Table 2). At 25-35°C, the strains formed non-pigmented, light beige colonies within 2-3 days. Colony morphology varied with the growth medium: on Middlebrook 7H10, colonies appeared small and round, whereas on GPHF agar they appeared larger, rough, and dry (

Figure 1). Such phenotypic variation in colony morphology is common and can be influenced by environmental factors such as medium composition, temperature, and host interactions. This variability is well-documented in species like

M. avium and

M. abscessus, which can switch between morphotypes with distinct characteristics [

41]. These morphological shifts can be clinically relevant, as they can affect host-pathogen interactions and antibiotic susceptibility [

42].

Strain 21AC1

T tested positive for catalase and arylsulfatase activities, tellurite reduction, and Tween 80 hydrolysis. Based on API Coryne and API 20E strip results, all three strains showed positive reactions for nitrate reductase, pyrazinamidase, alkaline phosphatase, β-glucosidase, esculin hydrolysis, urease, and acetoin production (Voges-Proskauer test). None of the carbon sources included in the API strips were utilized by the strains under the tested conditions (

Table 3). In contrast,

M. fortuitum, used as a control in this study, utilized only L-arabinose as a sole carbon source, consistent with previous reports [

28]. The same study also reported that

M. porcinum could use inositol as a sole carbon source [

28]. Furthermore, other mycobacterial species, such as

M. barrassiae and

M. moriokaense, demonstrated the ability to utilize several sole carbon sources when tested using API Coryne and API 20E strips [

43].

Fatty acid analysis was conducted using the MIDI system and GS/MS (

Table 4). Strain 21AC1

T displayed a fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profile predominantly composed of the saturated fatty acid C16:0, followed by the unsaturated FAMEs C16:1ω6c and C18 :1ω9c, along with the characteristic tuberculostearic acid (TBSA) 10Me-18:0. This fatty acid composition closely resembles the profiles reported for

M. smegmatis,

M. fortuitum, and

M. genavense [

44,

45,

46].

Mycolic acids were identified by mass spectrometry, and their relative abundances were calculated from the total pool of detected mycolates (

Table 4). In strain 21AC1

T, the predominant species was the α-mycolate C

77H

150O

3 (36.25% relative abundance), followed by C

75H1

46O

3 (10.78%) and the oxygenated mycolate C

79H

154O

4 (9.92%). Based on exact masses, 81.5% of the mycolates were classified as α-mycolates and 18.5% as oxygenated (inferred to be epoxy-mycolates) [

47]. Comparable profiles have been reported for

M. goodii, M. wolinskyi, and

M. smegmatis by HPLC analysis [

48,

49]. In particular,

M. smegmatis produces three main mycolate classes: (i) α-mycolic acids (50–60% of total); (ii) α′-mycolates, a shorter variant found in some rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM); and (iii) epoxy-mycolates, containing an epoxide ring and largely confined to the

M. fortuitum-M. smegmatis group [

47]. Both α′- and epoxy-mycolates each account for roughly 15–30% of the mycolate pool [

50,

51]. Chain lengths for α′-mycolates are typically C₆₂–C₆₄ [

52,

53,

54], whereas α- and epoxy-mycolates range from C

77 to C

80 [

55]. Finally, MALDI-TOF Biotyper analysis of strain 21AC1

T yielded a score of 1.2, corresponding to “no reliable classification”.

3.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles

Although the pathogenic potential of strain 21AC1

T remains unknown, infections by

M. wolinskyi,

M. goodii and

M. smegmatis, historically rare in humans, are increasingly reported, particularly in nosocomial settings [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. The antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the three isolates belonging to the novel species are summarized in

Table 5. Strain 21AC1

T was susceptible to 10 of the 12 tested antimicrobials and exhibited intermediate susceptibility to imipenem and doxycycline. Strains 21AC14 and 21AC21 exhibited intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and tobramycin, whereas strain 21AC21 was resistant to imipenem (

Table 4). Intermediate susceptibility to doxycycline has previously been reported for

M. wolinskyi,

M. goodii, and clinical isolates of

M. smegmatis [

48]. Neither strain 21AC1

T nor 21AC14 showed resistance to tobramycin, in contrast to

M. wolinskyi, which has been reported to exhibit resistance to this antimicrobial [

48].

Table 5.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of Mycobacterium appelbergii strains.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of Mycobacterium appelbergii strains.

| Antimicrobial |

MIC (µg/mL)* |

| strain 21AC1T

|

strain 21AC14 |

strain 21AC21 |

| Amikacin |

0.25S

|

0.5S

|

0.25S

|

| Cefoxitin |

0.25S

|

2S

|

2S

|

| Ciprofloxacin |

0.5S

|

2I

|

2I

|

| Clarithromycin |

<0.125S

|

<0.125S

|

<0.125S

|

| Imipenem |

16I

|

16I

|

32R |

| Linezolid |

1S

|

0.25S

|

0.25S

|

| Meropenem |

0.25S

|

0.125S

|

0.25S

|

| Minocycline |

0.25S

|

0.5S

|

0.5S

|

| Moxifloxacin |

0.25S

|

0.5S

|

0.25S

|

| Tobramycin |

1S

|

4I

|

4I

|

| Doxycycline |

2I

|

2I

|

2I

|

| TMP-SMX |

0.5-9.5S

|

<0.125-2.375S

|

<0.125-2.375S

|

4. Conclusions

The present study describes the isolation and characterization of three isolates of a novel, rapidly growing non-pigmented NTM, for which the name Mycobacterium appelbergii sp. nov. is proposed. All three strains, recovered from the water of a public fountain, shared a coherent suite of phenotypic traits and genomic markers that clearly differentiate them from three nearest relatives, M. goodii, M. wolinskyi, and M. smegmatis. Comprehensive phylogenomic, biochemical and chemotaxonomic analyses uniformly support their status as a distinct species.

By expanding the known diversity of environemntal mycobacteria, the identification of M. appelbergii underscores the role of water supply systems as reservoirs for NTM. Although this work focused on taxonomic characterization, the isolation of M. appelbergii from a drinking water source highlights the need for follow-up studies on its potential clinical relevance, and ecological persistence. These foundational data lay the groundwoork for future investigations of this newly recognized species.

5. Description of Mycobacterium appelbergii sp. nov.

Mycobacterium appelbergii (ap.pel.berg’i.i. N.L. adj. appelbergii, in honour of Rui Appelberg, in recognition of his significant scientific contributions to the understanding of the immune response, vaccine development, and immune pathology associated with Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections). Mycobacterium appelbergii is a non-motile, non-spore-forming bacillus. Colonies are non-pigmented (light beige), appearing within 2-3 days at temperatures 25-35°C, with distinct morphologies on different media: small and round on Middlebrook 7H10 agar, and larger, irregular, and dry on GPHF agar. The bacteria grow on Middlebrook 7H9 broth within approximately 24 h at temperatures ranging from 20°C to 35°C, with an optimal growth temperature at about 30ºC. No growth occurs at 40°C. The species tolerates up to 5% NaCl. Mycobacterium appelbergii is biochemically positive for catalase (room temperature and 68ºC), arylsulfatase, tellurite reduction, Tween 80 hydrolysis, nitrate reductase, pyrazinamidase, alkaline phosphatase, β-glucosidase, esculin hydrolysis, urease, and acetoin production. The major cellular fatty acids include C16:0, C16:1ω6c, C18 :1ω9c, and 10Me-18:0 (tuberculostearic acid, TBSA). The predominant mycolic acid is C77H15003. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing indicates that M. appelbergii is susceptible to amikacin, cefoxitin, clarithromycin, linezolid, meropenem, minocycline, moxifloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), exhibits intermediate susceptibility to doxycycline, and variable susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (S-I), tobramycin (S-I) and imipenem (I-R). The genomic DNA G+C content ranges from 65.88-65.91 mol%. Three strains were isolated from water samples from a public fountain and its runoff. The type strain, 21AC1T has been deposited in the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ), Braunschweig, Germany, as DSM 113570, and in the Belgium Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms (BCCM) Mycobacteriology Unit, Institute of Tropical Medicine, as BCCM/ITM 501212.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through the COMPETE 2020 - Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation and Portuguese national funds via FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under projects PTDC/BIA-MIC/0122/2021 and projects UIDB/04539/2020, UIDP/04539/2020 and LA/P/0058/2020. FCT is also acknowledged for supporting S. Alarico through contract 10.54499/DL57/2016/CP1448/CT0017 and for PhD scholarship SFRH/BD/145135/2019 to I. Roxo. The authors acknowledge Sociedade Portuguesa de Pneumologia and Boehringer Ingelheim for “Prémio Thomé Villar 2017” award.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

NTM, nontuberculous mycobacteria; OADC, oleate-albumin-dextrose-catalase; LJ, Löwenstein–Jensen; MIC, Minimal inhibitory concentration; MALDI-TOF, Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry; DDH, DNA-DNA hybridization

References

-

Nunes-Costa D, Alarico S, Dalcolmo MP, Correia-Neves M, Empadinhas N. The looming tide of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in Portugal and Brazil. Tuberculosis 2016;96:107-119. [CrossRef]

-

Oliveira MJ, Gaio AR, Gomes M, Gonçalves A, Duarte R. Mycobacterium avium infection in Portugal. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017;21(2):218-222. [CrossRef]

-

Pavlik I, Ulmann V, Falkinham III JO. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria: Ecology and Impact on Animal and Human Health. Microorganisms 2022;10(8):1516. [CrossRef]

-

Falkinham III JO. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the environment. Tuberculosis 2022;137:102267. [CrossRef]

-

Falkinham III JO. Environmental Sources of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med 2015;36(1):35-41. [CrossRef]

-

Li T, Abebe LS, Cronk R, Bartram J. A systematic review of waterborne infections from nontuberculous mycobacteria in health care facility water systems. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2017;220(3):611-620. [CrossRef]

-

Thomson RM, Tolson C, Carter R, Coulter C, Huygens F et al. Isolation of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM) from Household Water and Shower Aerosols in Patients with Pulmonary Disease Caused by NTM. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51(9):3006-3011. [CrossRef]

-

Gopalaswamy R, Shanmugam S, Mondal R, Subbian S. Of tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections – a comparative analysis of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. J Biomed Sci 2020;27(1):74. [CrossRef]

-

Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, Castelli F. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2022;35(2). [CrossRef]

-

Timpe A, Runyon EH. The relationship of atypical acid-fast bacteria to human disease; a preliminary report. J Lab Clin Med 1954;44(2):202-209.

-

Ahmed I, Tiberi S, Farooqi J, Jabeen K, Yeboah-Manu D et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections—A neglected and emerging problem. Int J Infect Dis 2020;92:S46-S50. [CrossRef]

-

Kunduracılar H. Identification of mycobacteria species by molecular methods. Int Wound J 2020;17(2):245-250. [CrossRef]

-

Ahmad S, Mokaddas E. Diversity of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Kuwait: Rapid Identification and Differentiation of Mycobacterium Species by Multiplex PCR, INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 Assay and PCR Sequencing of rDNA. Med Princ Pract 2019;28(3):208-215. [CrossRef]

-

Forbes BA, Hall GS, Miller MB, Novak SM, Rowlinson M-C et al. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: Mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018;31(2). [CrossRef]

-

Durão V, Silva A, Macedo R, Durão P, Santos-Silva A et al. Portuguese in vitro antibiotic susceptibilities favor current nontuberculous mycobacteria treatment guidelines. Pulmonology 2019;25(3):162-167. [CrossRef]

-

Primm TP, Lucero CA, Falkinham III JO. Health Impacts of Environmental Mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17(1):98-106. [CrossRef]

-

Vaerewijck MJM, Huys G, Palomino JC, Swings J, Portaels F. Mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems: ecology and significance for human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2005;29(5):911-934. [CrossRef]

-

Radomski N, Cambau E, Moulin L, Haenn S, Moilleron R et al. Comparison of Culture Methods for Isolation of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria from Surface Waters. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010;76(11):3514-3520. [CrossRef]

-

Williams MD, Falkinham III JO. Effect of Cetylpyridinium Chloride (CPC) on Colony Formation of Common Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Pathogens 2018;7(4). [CrossRef]

-

Pereira SG, Alarico S, Tiago I, Reis D, Nunes-Costa D et al. Studies of antimicrobial resistance in rare mycobacteria from a nosocomial environment. BMC Microbiol, journal article 2019;19(1):62. [CrossRef]

-

Alarico S, Nunes-Costa D, Silva A, Costa M, Macedo-Ribeiro S et al. A genuine mycobacterial thermophile: Mycobacterium hassiacum growth, survival and GpgS stability at near-pasteurization temperatures. Microbiology 2020;166(5):474-483. [CrossRef]

-

Uritskiy GV, DiRuggiero J, Taylor J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 2018;6(1):158. [CrossRef]

-

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012;19(5):455-477. [CrossRef]

-

Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 2015;3:e1165. [CrossRef]

-

Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 2015;25(7):1043-1055. [CrossRef]

-

Alarico S, Costa M, Sousa MS, Maranha A, Lourenco EC et al. Mycobacterium hassiacum recovers from nitrogen starvation with up-regulation of a novel glucosylglycerate hydrolase and depletion of the accumulated glucosylglycerate. Sci Rep 2014;4:6766. [CrossRef]

-

Bhalla GS, Sarao MS, Kalra D, Bandyopadhyay K, John AR. Methods of phenotypic identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Pract Lab Med 2018;12:e00107. [CrossRef]

-

Adékambi T, Stein A, Carvajal J, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Description of Mycobacterium conceptionense sp. nov., a Mycobacterium fortuitum Group Organism Isolated from a Posttraumatic Osteitis Inflammation. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44(4):1268-1273. [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, Nocardia spp., and other aerobic actinomycetes. Document M24. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute2018.

- CLSI. Performance standards for susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, Nocardia spp., and other aerobic actinomycetes. Supplement M24S. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute2023.

-

Brown-Elliott BA, Woods GL. Antimycobacterial Susceptibility Testing of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol 2019;57(10):e00834-00819. [CrossRef]

-

Ankenbrand MJ, Keller A. bcgTree: automatized phylogenetic tree building from bacterial core genomes. Genome 2016;59(10):783-791. [CrossRef]

-

Yoon SH, Ha SM, Lim J, Kwon S, Chun J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2017;110(10):1281-1286. [CrossRef]

-

Stackebrandt E, Frederiksen W, Garrity GM, Grimont PAD, Kämpfer P et al. Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002;52(3):1043-1047. [CrossRef]

-

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009;106(45):19126-19131. [CrossRef]

-

Lipner EM, French J, Bern CR, Walton-Day K, Knox D et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease and Molybdenum in Colorado Watersheds. Int J Env Res Public Health 2020;17(11):3854. [CrossRef]

-

Lipner EM, French JP, Falkinham III JO, Crooks JL, Mercaldo RA et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Infection Risk and Trace Metals in Surface Water: A Population-based Ecologic Epidemiologic Study in Oregon. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022;19(4):543-550. [CrossRef]

-

Lipner EM, French JP, Mercaldo RA, Nelson S, Zelazny AM et al. The risk of pulmonary NTM infections and water-quality constituents among persons with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 2010–2019. Environ Epidemiol 2023;7(5). [CrossRef]

-

Bahr C, Jekel M, Amy G. Vanadium removal from drinking water by fixed-bed adsorption on granular ferric hydroxide. AWWA Water Sci 2022;4(1):e1271. [CrossRef]

-

Pichler T, Koopmann S. Should Monitoring of Molybdenum (Mo) in Groundwater, Drinking Water and Well Permitting Made Mandatory? Environ Sci Technol 2020;54(1):1-2. [CrossRef]

-

To K, Cao R, Yegiazaryan A, Owens J, Venketaraman V. General Overview of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Opportunistic Pathogens: Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus. J Clin Med 2020;9(8):2541. [CrossRef]

-

Koh W-J. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria — Overview. Microbiol Spectr 2017;5(1). [CrossRef]

-

Adékambi T, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Mycobacterium barrassiae sp. nov., a Mycobacterium moriokaense Group Species Associated with Chronic Pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44(10):3493-3498. [CrossRef]

-

Chou S, Chedore P, Kasatiya S. Use of Gas Chromatographic Fatty Acid and Mycolic Acid Cleavage Product Determination To Differentiate among Mycobacterium genavense, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium simiae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36(2):577-579. [CrossRef]

-

Selvarangan R, Wu W-K, Nguyen TT, Carlson LDC, Wallis CK et al. Characterization of a Novel Group of Mycobacteria and Proposal of Mycobacterium sherrisii sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42(1):52-59. [CrossRef]

-

Zimhony O, Vilchèze C, Jacobs WR. Characterization of Mycobacterium smegmatis Expressing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Fatty Acid Synthase I (fas1) Gene. J Bacteriol 2004;186(13):4051-4055. [CrossRef]

-

Minnikin DE, Minnikin SM, Parlett JH, Goodfellow M. Mycolic Acid Patterns of Some Rapidly-Growing Species of Mycobacterium. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Mikrobiologie und Hygiene Series A: Medical Microbiology, Infectious Diseases, Virology, Parasitology 1985;259(4):446-460. [CrossRef]

-

Brown BA, Springer B, Steingrube VA, Wilson RW, Pfyffer GE et al. Mycobacterium wolinskyi sp. nov. and Mycobacterium goodii sp. nov., two new rapidly growing species related to Mycobacterium smegmatis and associated with human wound infections: a cooperative study from the International Working Group on Mycobacterial Taxonomy. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 1999;49(4):1493-1511. [CrossRef]

-

Butler WR, Guthertz LS. Mycolic Acid Analysis by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for Identification of Mycobacterium Species. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001;14(4):704-726. [CrossRef]

-

Jamet S, Slama N, Domingues J, Laval F, Texier P et al. The Non-Essential Mycolic Acid Biosynthesis Genes hadA and hadC Contribute to the Physiology and Fitness of Mycobacterium smegmatis. PLOS ONE 2015;10(12):e0145883. [CrossRef]

-

Bouam A, Armstrong N, Levasseur A, Drancourt M. Mycobacterium terramassiliense, Mycobacterium rhizamassiliense and Mycobacterium numidiamassiliense sp. nov., three new Mycobacterium simiae complex species cultured from plant roots. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):9309. [CrossRef]

-

Baba T, Kaneda K, Kusunose E, Kusunose M, Yano I. Molecular species of mycolic acid subclasses in eight strains of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Lipids 1988;23(12):1132-1138. [CrossRef]

-

Etemadi A-H. Sur l’intérêt taxinomique et la signification phylogénétique des acides mycoliques. Bulletin de la Société Botanique de France 1965;112(sup1):47-74. [CrossRef]

-

Gray GR, Wong MYH, Danielson SJ. The major mycolic acids of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Progress in Lipid Research 1982;21(2):91-107. [CrossRef]

-

Laval F, Lanéelle M-A, Déon C, Monsarrat B, Daffé M. Accurate Molecular Mass Determination of Mycolic Acids by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry 2001;73(18):4537-4544. [CrossRef]

-

Fujikura H, Kasahara K, Ogawa Y, Hirai N, Yoshii S et al. Mycobacterium wolinskyi Peritonitis after Peritoneal Catheter Embedment Surgery. Intern Med 2017;56(22):3097-3101. [CrossRef]

-

Salas NM, Klein N. Mycobacterium goodii: An Emerging Nosocomial Pathogen: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2017;25(2):62-65. [CrossRef]

-

Waldron R, Waldron D, McMahon E, Reilly L, Riain UN et al. Mycobacterium goodii pneumonia: An unusual presentation of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection requiring a novel multidisciplinary approach to management. Respir Med Case Rep 2019;26:307-309. [CrossRef]

-

Hernández-Meneses M, González-Martin J, Agüero D, Tolosana JM, Sandoval E et al. Mycobacterium Wolinskyi: A New Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterium Associated with Cardiovascular Infections? Infect Dis Ther 2021;10(2):1073-1080. [CrossRef]

-

Pfeuffer-Jovic E, Heyckendorf J, Reischl U, Bohle RM, Bley T et al. Pulmonary vasculitis due to infection with Mycobacterium goodii: A case report. Int J Infect Dis 2021;104:178-180. [CrossRef]

-

Chen X, Zhu J, Liu Z, Ye J, Yang L et al. Mixed infection of three nontuberculous mycobacteria species identified by metagenomic next-generation sequencing in a patient with peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis: a rare case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol 2023;24(1):95. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).