Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

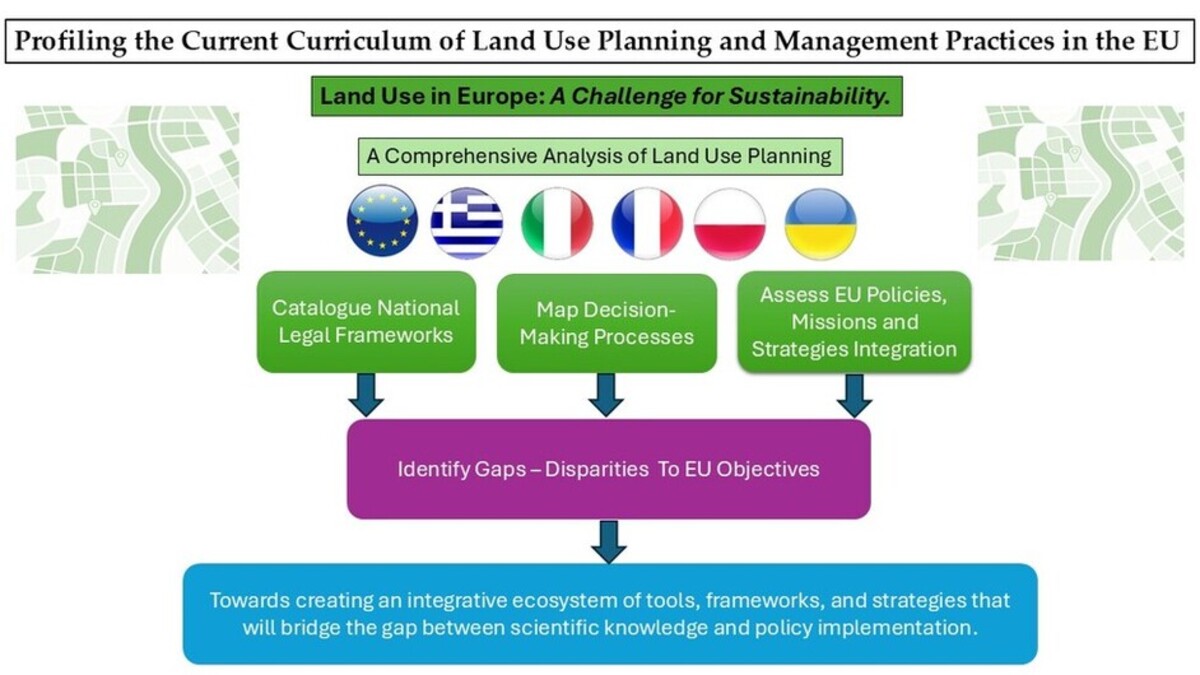

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- G. Tóth, “Impact of land-take on the land resource base for crop production in the European Union,” Sci Total Environ, vol. 435–436, pp. 202–214, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Goździewicz-Biechońska, “Law in the face of the problem of land take,” Przegląd Prawa Rolnego, no. 1(26), Art. no. 1(26), Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Paulsen, “Geography, policy or market? New evidence on the measurement and causes of sprawl (and infill) in US metropolitan regions,” Urban Studies, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 2629–2645, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Haase, M. Bernt, K. Großmann, V. Mykhnenko, and D. Rink, “Varieties of shrinkage in European cities,” European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 86–102, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvati et al., “Soil occupation efficiency and landscape conservation in four Mediterranean urban regions,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 20, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Carlucci, F. M. Chelli, and L. Salvati, “Toward a New Cycle: Short-Term Population Dynamics, Gentrification, and Re-Urbanization of Milan (Italy),” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvati and V. G. Morelli, “Unveiling Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean Region: Towards a Latent Urban Transformation?,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 1935–1953, 2014.

- W. Oueslati, S. Alvanides, and G. Garrod, “Determinants of urban sprawl in European cities,” Urban Studies, vol. 52, no. 9, pp. 1594–1614, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Hewitt and F. Escobar, “The territorial dynamics of fast-growing regions: Unsustainable land use change and future policy challenges in Madrid, Spain,” Applied Geography, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 650–667, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- “Land use.” Accessed: Aug. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/land-use.

- E. Ustaoglu and B. Williams, “Determinants of Urban Expansion and Agricultural Land Conversion in 25 EU Countries,” Environ Manage, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 717–746, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Ferrara, L. Salvati, A. Sabbi, and A. Colantoni, “Soil resources, land cover changes and rural areas: towards a spatial mismatch?,” Sci Total Environ, vol. 478, pp. 116–122, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Briassoulis, “Governing desertification in Mediterranean Europe: The challenge of environmental policy integration in multi-level governance contexts,” Land Degradation & Development, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 313–325, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvati and A. Ferrara, “Do land cover changes shape sensitivity to forest fires in peri-urban areas?,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 571–575, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “Guides | SEDAC.” Accessed: Aug. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/guides.

- R. S. de Groot, R. Alkemade, L. Braat, L. Hein, and L. Willemen, “Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making,” ECOL COMPLEX, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 260–272, 2010. [CrossRef]

- “Land cover accounts — an approach to geospatial environmental accounting,” European Environment Agency. Accessed: Aug. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/land-cover-accounts.

- “ICCD/COP(12)/20/Add.1,” UNCCD. Accessed: Sep. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.unccd.int/official-documents/cop-12-ankara-2015/iccdcop1220add1.

- A. L. Cowie et al., “Land in balance: The scientific conceptual framework for Land Degradation Neutrality,” Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 79, pp. 25–35, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Thompson, D. N. Carpenter, C. V. Cogbill, and D. R. Foster, “Four Centuries of Change in Northeastern United States Forests,” PLOS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, p. e72540, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Niedertscheider, T. Kuemmerle, D. Müller, and K.-H. Erb, “Exploring the effects of drastic institutional and socio-economic changes on land system dynamics in Germany between 1883 and 2007,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 28, pp. 98–108, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion | PLOS ONE.” Accessed: Aug. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0023777.

- M. Niedertscheider and K.-H. Erb, “Land system change in Italy from 1884 to 2007: Analysing the North–South divergence on the basis of an integrated indicator framework,” Land Use Policy, vol. 39, pp. 366–375, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Stellmes, A. Röder, T. Udelhoven, and J. Hill, “Mapping syndromes of land change in Spain with remote sensing time series, demographic and climatic data,” Land Use Policy, vol. 30, pp. 685–702, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Gellrich, P. Baur, B. Koch, and N. Zimmermann, “Agricultural land abandonment and natural forest re-growth in the Swiss mountains: A spatially explicit economic analysis,” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, vol. 118, pp. 93–108, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Müller, T. Kuemmerle, M. Rusu, and P. Griffiths, “Lost in transition: determinants of post-socialist cropland abandonment in Romania,” Journal of Land Use Science, vol. 4, no. 1–2, pp. 109–129, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. Kastner, K.-H. Erb, and H. Haberl, “Rapid growth in agricultural trade: effects on global area efficiency and the role of management,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 9, no. 3, p. 034015, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvati and M. Carlucci, “Zero Net Land Degradation in Italy: the role of socioeconomic and agro-forest factors,” J Environ Manage, vol. 145, pp. 299–306, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Salvati, M. Karamesouti, and K. Kosmas, “Soil degradation in environmentally sensitive areas driven by urbanization: An example from Southeast Europe,” Soil Use and Management, vol. 30, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Paul and M. Tonts, “Containing Urban Sprawl: Trends in Land Use and Spatial Planning in the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona,” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 7–35, 2005. [CrossRef]

- “Smart Cities | Free Full-Text | Exploring Key Aspects of an Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategy in Greece: The Case of Thessaloniki City.” Accessed: Sep. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2624-6511/6/1/2.

- G. Giannakourou, “Transforming spatial planning policy in Mediterranean countries: Europeanization and domestic change,” European Planning Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 319–331, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. Economou, “The planning system and rural land use control in Greece: A European perspective,” http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0031411506&partnerID=40&md5=498f9796217602a772a6233459250230, 1997, Accessed: Sep. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://ir.lib.uth.gr/xmlui/handle/11615/27279.

- H. Coccossis, D. Economou, and G. Petrakos, “The ESDP relevance to a distant partner: Greece,” European Planning Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 253–264, 2005.

- D. Stathakis and P. Baltas, “The Greek model of urbanization,” Land Use Policy, vol. 140, p. 107113, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- OECD, “Greece,” OECD, Paris, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- OECD, “Italy,” OECD, Paris, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Rega, “Ecological compensation in spatial planning in Italy,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 45–51, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Montaldi, “Consumo di suolo : un complesso quadro di politiche, definizioni e soglie,” Territorio : 103, 4, 2022, pp. 147–156, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Conticelli, S. Tondelli, S. Rossetti, M. Zazzi, and B. Caselli, “La nuova disciplina regionale sulla tutela e l’uso del territorio in Emilia Romagna (L-R. 24/2017). L’ambiziosa scommessa della terza legge urbanistica regionale tra conferme e innovazioni,” ITA, 2021. Accessed: Sep. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://cris.unibo.it/handle/11585/937714?mode=complete.

- “Spatial and land use planning in France | READ online,” oecd-ilibrary.org. Accessed: Aug. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/the-governance-of-land-use-in-france/spatial-and-land-use-planning-in-france_9789264268791-5-en.

- Europäische Kommission, Ed., The EU compendium of spatial planning systems and policies—France. in Regional development studies, no. 28E. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publ. of the European Communities, 2000.

- OECD, “Aix-Marseille, France,” OECD, Paris, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Geppert, “France, drifting away from the ‘regional economic’ approach,” 2014, pp. 109–126.

- M. Spaans, “The Changing Role of the Dutch Supralocal and Regional Levels in Spatial Planning: What Can France Teach Us?,” International Planning Studies, vol. 12, pp. 205–219, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R.-M. Cocheci, “Planning in Restrictive Environments—A Comparative Analysis of Planning Systems in EU Countries,” Journal of Urban and Landscape Planning, vol. 1, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- OECD, Governance of Land Use in Poland: The Case of Lodz. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016. Accessed: Aug. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/governance-of-land-use-in-poland_9789264260597-en.

- K. Cegielska et al., “Land use and land cover changes in post-socialist countries: Some observations from Hungary and Poland,” Land Use Policy, vol. 78, pp. 1–18, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Kwartnik-Pruc, “Exclusion of land from agricultural and forestry production : practical problems of the procedure,” Geomatics and Environmental Engineering, vol. 5, Jul. 2011.

- V. Radeloff and G. Gutman, “Land-Cover and Land-Use Changes in Eastern Europe after the Collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991,” Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Skakun, C. O. Justice, N. Kussul, A. Shelestov, and M. Lavreniuk, “Satellite Data Reveal Cropland Losses in South-Eastern Ukraine Under Military Conflict,” Front. Earth Sci., vol. 7, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Kogan and T. Adamenko, “Global and regional drought dynamics in the climate warming era,” Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 4, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Gray, “Ukraine Oilseeds and Products Annual Soybean Crush Unleashed for MY2018/19”.

- N. Tretiak et al., “Land Resources and Land Use Management in Ukraine: Problems of Agreement of the Institutional Structure, Functions and Authorities,” European Research Studies, vol. XXIV, no. 1, pp. 776–789, Feb. 2021.

- Z. Izakovičová, J. Špulerová, and F. Petrovič, “Integrated Approach to Sustainable Land Use Management,” Environments, vol. 5, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

| Source | Targets and Goals |

| EU, 2018/841- Land use and forestry regulation for 2021-20303 | The framework outlines the commitments required of Member States regarding the LULUCF sector, which are integral to meet the targets set forth by the Paris Agreement and the EU’s GHG emission reduction goals for the 2021-2030 period. It also specifies the guidelines for accounting emissions and removals related to LULUCF practices. |

| Regulation (EU) 2023/839- LULUCF Amendment4 | Amends Regulation 2018/841 and the Governance Regulation 2018/1999, widening scope, simplifying reporting/compliance, and setting updated Member-State LULUCF targets for 2030. |

| Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (EC, 2020c)5 | Chapter 2.2: Commitment to Land Degradation Neutrality through Updating Soil and Built Environment Strategies and the Mission of Soil Health and Food under Horizon Europe. |

| Soil Strategy for 2030 (EC, 2021)6 | Chapter 2: Reach no net land take by 2050. MS should set their own national, regional, and local targets. |

| Mission for Soil Health and Food (EC, 2020d)7 |

Objective 3: No net soil sealing and increase the reuse of urban soils for urban development Target 3.1: Switch from 2,4% to no net soil sealing Target 3.2: Increase the current rate of soil reuse from 13% to 50%. |

| Roadmap to a resource-efficient Europe (EC, 2011)8 | Milestone 4.6: Achieve no net land take by 2050. |

| Eighth Environment Action Programme to 2030 (EC, 2020b)9 |

Objectives: Decoupling economic growth from resource use and environmental degradation, targeting a zero-pollution ambition for a toxin-free environment, including air, water and soil protection, preservation and restoration of biodiversity |

| Country | Law | Short Description |

| Greece | Law 4685/2020—Incorporation into Greek legislation of Directives 2018/844 and 2019/692 of the European Parliament, the Council, and other provisions.10 | Chapter 3 pertains to the administration of protected areas and includes various essential elements: the governing bodies of the National Policy Governance System for Protected Areas; the formation, objectives, and oversight of the Natural Environment and Climate Change Organisation, which is responsible for advancing sustainable development and addressing climate change. It encompasses the functions and obligations of Protected Areas Management Units, including the conservation of species and habitats, the assessment of management objectives, engagement in local fire prevention planning, public awareness initiatives regarding protected areas, and actions that support ecotourism initiatives. Chapter 4 deals with the classification of specific zones within a protected area, which includes zones designated for absolute nature protection, special usage categories, and activities such as agriculture, forestry, livestock, aquaculture, recreational and professional fishing, rural development land improvement projects, and extractive activities; as well as biodiversity protection areas, wildlife sanctuaries, and national parks, along with their specific characteristics. |

| Law 4447/2016—Spatial Planning, Sustainable Development, and Other Provisions.11 | Consisting of 56 articles and divided into two main parts, it is designed to delineate a framework for spatial and urban planning, focusing on sustainable development and environmental protection. Specifically, Part I pertains to land use and spatial planning, defining essential terms such as the spatial planning system and strategic spatial planning. It also addresses regulatory spatial planning, which governs land use in urban and rural contexts. The law encompasses the organization and structure of the spatial planning system, the national spatial strategy for sustainable development, the management of public assets, the implementation of land policy, as well as the creation of a national planning council and its associated responsibilities. | |

| Law 4759/2020—Modernization of Spatial and Urban Planning Legislation.12 | Law’s provisions/objectives are articulated as folows: The spatial and urban planning system is designed to be more efficient, expeditious, and improved, addressing existing ambiguities and conflicts. Specific provisions for maritime spatial planning are delineated, ensuring its separation from land spatial planning, particularly concerning coastal land areas. Regulations are established for development activities outside urban planning zones and within organized areas for productive endeavours. The law emphasizes the control and protection of the constructed environment. An electronic urban identity framework is introduced. Provisions address unauthorized constructions and land-use alterations to resolve challenges related to interpreting associated regulations. Law introduces measures for urban expropriation. It stipulates the appointment of certified evaluators for spatial reports, who will evaluate these documents to guide the development of spatial and urban plans. |

|

| Law 2742/199913 Spatial planning, sustainable development and other provisions. |

The law is designed to establish core principles and develop modern governance frameworks, processes, and land and spatial planning strategies that facilitate sustainable development. It aims to promote productive and social cohesion, protect the environment throughout the national territory, and enhance the nation’s position at the international and European levels. The law comprises six chapters and 29 articles outlining the necessary characteristics for National Frameworks of Spatial Planning, encompassing general and thematic aspects. | |

| Law 1650/1986, Article 1914 | This law serves as the foundation for environmental protection. Its core objectives include preventing pollution and environmental degradation, safeguarding human health, renewing natural resources, and rationally managing non-renewable or rare resources, considering existing and anticipated needs. It aims to protect soil, surface, subterranean waters, and the atmosphere while ensuring the conservation of nature and landscapes, particularly in regions of notable biological, ecological, aesthetic, or geomorphological significance. The law also regulates permissible waste emissions and mandates environmental impact assessments. It is essential to highlight that Law 1650/86 introduces a more extensive classification of protected areas than that currently defined by the Forestry Code. |

|

| Italy | Legge Urbanistica, 1942, n. 1150.15 |

The Law constituted one of the most advanced urban planning regulations of its time and continues to underpin the complex framework of Italian urban planning legislation. The proposed system was hierarchical, emphasizing strict urban and regional spatial development regulations and direct governmental action at the national level. This system was clearly defined and consisted of two principal planning types: an urban land-use plan and a regional strategic plan, known as the territorial coordination plan. The plans were associated with two principal institutions: the municipalities and the national government. |

| “Bridge Law” No.765, of 196716 and the Joint Ministerial Decrees of 196817 (both amendments of the Legge Urbanistica) |

Both instituted mandatory taxations to facilitate the provision of land for public use and developed standards for allocating public services and infrastructure in each land-use plan based on the expected demographic growth over the next ten years. | |

| Law No. 142 of 8 June 1990 “Ordinamento delle autonomie locali” | Established the fundamental framework for local government organization in Italy, emphasising decentralisation and administrative autonomy. The law defines roles, responsibilities, and governance structures for municipalities, provinces, and metropolitan cities. Part of its objectives is to promote administrative decentralization and local autonomy. Additionally, it provides the guidelines for territorial and urban planning, while facilitating inter-municipal and inter-institutional cooperation. Among its key provisions, it recognizes municipalities (Comuni) and provinces (Province) as autonomous administrative units, as well as establishing the role and functions of metropolitan cities. Furthermore, the law introduces tools for coordination between municipalities and higher-level planning authorities. |

|

| Title V (Titolo Quinto)18 (Modified by Constitutional Law n. 3/2001) |

Comprising 20 articles, the Law articulates in Article 17 the primacy of national legislative frameworks in four domains: environmental protection, cultural heritage, landscape conservation, and territorial governance, alongside infrastructure and urban planning. This article also empowers the regions with legislative autonomy concerning issues not expressly reserved for the State. | |

| Legislative Decree 22 January 2004, n. 42 Code of Cultural and landscape heritage (protection of landscape environment)19 | This Legislative Decree outlines Italy’s national code for protecting cultural and landscape heritage, which also encompasses environmental heritage. It proclaims the Italian Republic’s responsibility to defend cultural heritage and to support the conservation of the collective memory of its national community and territory, aligning with the broader objectives of cultural promotion and development. In Article 142, paragraph 1, sections c-g, protective measures apply to an array of natural landscapes, including but not limited to rivers, streams, waterways, mountains, glaciers, national and regional parks, and forested territories. | |

| Legislative Decree No. 152/2006 approving the Code on the Environment.20 | The Code is organized into six Parts. The first part, Part I (articles 1-3), defines the scope of the application and introduces general provisions applicable to all sectors covered by the Code. Part II (articles 4-52) focuses on defining and regulating the procedures related to Strategic Environmental Assessment (VAS), Environmental Impact Assessment (VIA), and Integrated Environmental Authorization (IPPC). Part III (articles 53-176) focuses on soil protection, particularly addressing desertification. It also focuses on protecting water resources from contamination and their management. The national territory is categorized into hydrographical districts, where basin plans will be implemented. Section IV (articles 177-266) addresses waste management and the remediation of polluted sites, outlining the organization of the Integrated Waste Management Service. The fifth Part (articles 267-298) focuses on air quality, striving to decrease atmospheric emissions. Finally, the sixth Part (articles 299-318) applies the precautionary principle and delineates the liability framework. | |

| France | SRU ‘La loi relative à la solidarité et au renouvellement urbain’, 200021 | SRU law aims to combat socio-spatial divides in urban settings by fostering greater solidarity and addressing urban sprawl by carefully densifying already urbanized areas. The law clarifies the provisions of the City Orientation Law (LOV) from 1992, particularly regarding the balance of social housing in urban locales. The SRU law further defines the potential role of the State within a refreshed vision of urban planning. Article 1 stipulates that the territorial coherence plan (SCOT) is a compulsory element for enhancing spatial planning in urban settings. The SRU law aims to improve subdivision quality by requiring operators to submit an architectural and landscape project with their applications for subdivision authorization. This project should incorporate elements related to environmental sustainability and waste management. Simultaneously, the SRU law also serves to ease the restrictions associated with marketing practices. |

| The ‘Grenelle I’ Law (2009)22 |

The Grenelle I framework delineates various objectives and targets pertinent to climate change and energy management, including: Buildings: Establish the building sector as the foremost ally in combating climate change. Enforce the ‘Low Consumption Building’ standard for all new developments starting at the end of 2012 to maintain primary energy consumption below 50 kWh/m²/year. Target a 38% reduction in energy usage in older buildings by 2020. Urban planning: Synchronize policy and planning documents, especially those relevant to urban agglomerations. Transport: By 2020, reduce GHG emissions by 20% and decrease the sector’s dependence on fossil fuels. Implement an eco-tax for heavy vehicles in 2011. Invest EUR 2.5 billion from the state budget by 2020 to improve urban public transport infrastructure. • Energy: Contribute to the ambitious goal of reducing GHG emissions, aiming for a minimum of 23% of the energy mix to come from renewable sources by 2020. |

|

| Law 2010-788, 2010, on National Commitment for the Environment, also called the “Grenelle II Law.”23 | The law validates and expands upon the sustainable development objectives outlined in France’s 2009 Grenelle I Law. However, it lacks any provisions for a carbon tax, as France has chosen to await the establishment of relevant EU regulations. The statute is structured into six fundamental titles. Title I, “Buildings and Urban Planning,” focuses on optimizing building energy utilisation. Title II, referred to as “Transport,” includes provisions designed to hasten the progress of public transportation infrastructure. The provisions of Title III, known as “Energy and Climate,” introduce initiatives focused on minimizing energy consumption and carbon emissions by including energy-CO2 performance metrics on product labels. Title IV, “Biodiversity,” addresses strategies to ensure the effective operation of ecosystems and restore high-quality ecological water standards. Title V, “Risks, Health, and Wastes,” presents measures to alleviate noise and artificial light disturbances. Title VI, entitled “Governance,” mandates that corporations include a segment in their annual reports detailing the social and environmental impacts of their operations, along with a declaration of their commitment to sustainable development. |

|

| Poland | Act on the protection of agricultural and forest land (1995)—(Ustawa o ochronie gruntów rolnych i leśnych)24. |

This legislative framework articulates essential principles for protecting agricultural and forest lands and recultivating and improving land quality. Agricultural lands are safeguarded through several strategies, including limiting their use for other purposes, preventing degradation and destruction, implementing recultivation efforts, and conserving peat areas and natural water bodies. Likewise, forest lands are protected through restrictions on their allocation for alternative uses, measures to prevent degradation and destruction, efforts to restore land value, and actions to maintain or enhance productivity. The statute is divided into the following sections: General provisions; Limitations on land allocation for purposes that are neither agricultural nor forestry-related; Exclusion of land from agricultural or forestry production; Initiatives aimed at preventing land degradation; Land recultivation and its subsequent use; Financial aspects related to the exclusion of agricultural land from production; Supervision of the implementation of the provisions outlined in this Act; and finally, Transitional and final provisions. |

| Act on planning and spatial development (2003) - (Ustawa z dnia 27 marca 2003 r. o planowaniu i zagospodarowaniu przestrzennym)25 |

The Act outlines the foundational principles that guide the formulation of spatial policy by local government entities and administrative bodies. It outlines the extent and methodologies employed in allocating land for designated purposes and establishing regulations governing their development. It emphasizes spatial order and sustainable development as the cornerstone of these initiatives. The Act is organized into seven distinct chapters containing 89 articles. The chapters are as follows: General Rules; Spatial Planning in the Commune; Spatial Planning at the voivodeship Level; National Spatial Planning; Functional Areas; The Location of Public Purpose Investments and the Determination of Development Conditions for Additional Investments; Spatial Data Sets; Amendments to current legal provisions; and Provisions for transition and finalization. | |

| National Spatial Development Concept (NSDC)-203026 | The National Spatial Development Concept 2030 (NSDC 2030) is a fundamental national strategic document that governs spatial planning management in Poland. Six interconnected objectives for national spatial development by 2030 have been defined to support the realisation of this strategic goal. The NSDC 2030 framework aspires to improve the productivity and sustainability of the agricultural sector. Its second objective is to bolster internal cohesion and ensure equitable territorial development across the country’s regions by enabling the entire population to partake in development processes through guaranteed access to quality employment and public services. The fourth objective is to develop spatial structures that promote the achievement and preservation of Poland’s high-quality natural environment and landscape. To meet developmental needs, securing access to high-quality water is vital. A balance will be maintained between water extraction and wastewater discharge within catchment units. Moreover, the management protocols for other resources, such as soils and strategic minerals, will be clearly defined to enable the efficient and timely resolution of conflicts related to land development and to oversee the management of other natural resources in the same geographical context. Objective five is dedicated to reinforcing the resilience of spatial structures against the impacts of natural disasters and energy security issues while promoting spatial arrangements that enhance national defence capabilities. The principal elements of this objective include strengthening protection measures against extreme natural and man-made disasters, addressing threats to energy security, and developing effective strategies to respond to these threats. |

|

| Ukraine | Law No. 962-IV “On land protection”27. | This statute lays down the legal, economic, and social foundations for safeguarding land. It intends to promote sustainable land management, soil restoration, and enhancement while preserving the soil’s ecological functions and protecting the environment. The core principles of land protection are as follows: (a) ensuring the protection of land as the main national wealth of the Ukrainian people; (b) prioritizing the environmental safety requirements in the use of land as a spatial basis, natural resources and primary means of production; (c) providing compensation for damages caused by breaches of national land protection regulations; (d) regulating and limiting the effects of economic activities on soil; (e) combining economic incentives with legal responsibilities in the domain of land protection; and (f) promoting public involvement and transparency in land protection processes. This legal framework comprises nine sections, each further divided into fifty-six articles. The initial section presents the general provisions. The second section articulates the powers of state authorities and local government bodies concerning land protection. The third section pertains to the supervisory functions relating to land protection. The fourth section outlines comprehensive measures for land protection. The fifth section establishes the state standards and regulations applicable to land protection. The sixth section discusses the role of economic activities in land protection. The seventh section addresses the funding mechanisms for land and soil protection initiatives. The eighth section outlines the liabilities for violating land protection laws. The ninth section concludes with the final provisions of the legislation. |

| Land Code (No. 2768-III of 2001)28. | The Law is organized into X Sections, which collectively contain 212 articles. Section I introduces the general provisions. Section II defines the composition and purpose of the Ukrainian land. Section III outlines the rights associated with land ownership. Section IV discusses the acquisition and exercise of these land rights. Section V provides guarantees for the protection of land rights. Section VI addresses the issue of land conservation. Section VII pertains to management practices related to land use and its protection. Section VIII outlines the liabilities for breaches of land legislation. Section IX contains the final provisions, and Section X outlines the transitional provisions. Article 182 of the Law delineates that land management aims to promote the rational utilization and safeguarding of soil, establish a conducive environment, and enhance natural landscapes. |

|

| Law No. 858-IV on land management29. | The existing law establishes the legal and organizational parameters for land management, targeting the regulation of relationships between state executive bodies, local self-governments, legal entities and individuals to ensure sustainable development of land use practice. This framework is designed to ensure the sustainable development of land use practices. The legal framework is divided into nine sections, encompassing seventy articles. Section one (articles 1-7) provides the general provisions. Section two (articles 8-19) defines the plenary powers of state executive authorities and local self-governments concerning land use planning. Section three (articles 20-41) focuses on organizing and regulating land management processes. Section four (articles 45-48) addresses the execution of land management at national and regional scales. Section five (articles 49-59) pertains to implementing land use planning at the local level. Section six (articles 60, 61-1, and 63) discusses the state and the self-government control of land management. Section seven (articles 65-67) covers the scientific basis, personnel training, and funding related to land management. Section eight (articles 68-70) outlines the liabilities for land management legislation breaches. The ninth section concludes with final provisions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).