1. Introduction

Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) enables multiple entities to collaboratively perform distributed computations without compromising the confidentiality of their private data. In this context, the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem [

1], a homomorphic generalisation of the Paillier scheme [

2], emerges as an efficient alternative for secure aggregation operations, overcoming limitations of traditional asymmetric protocols such as RSA [

3] or ElGamal [

4]. Its ability to perform summations and scalar multiplications over encrypted data makes it an ideal candidate for decentralised multiparty environments.

The protocol proposed by Mehnaz et al. [

5], based on ElGamal, offers resistance to collusion between up to

parties but introduces quadratic complexity (

) and relies heavily on a trusted server, which limits its scalability. Furthermore, its layered encryption strategy introduces significant computational and communication overhead, particularly in the key-sharing phase, a step omitted in the original analysis. These limitations motivate the exploration of additive homomorphic schemes that simplify the architecture and reduce trust assumptions.

In this work, we present an adaptation of the Mehnaz protocol that uses the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem, integrating Schnorr’s noninteractive zero-knowledge proofs (NIZK) [

6] to verify the integrity of the results without revealing intermediate inputs. Our core contributions demonstrate that

- (i)

The additive homomorphic structure of Damgård-Jurik reduces computational complexity to ,

- (ii)

The elimination of layered encryption mitigates risks associated with partial collusions, and

- (iii)

NIZKs ensure correctness of the final computation without incurring additional communication costs.

We implemented our protocol through a proof-of-concept that processes data under both vertical and horizontal partitioning schemes, evidencing linear execution times and efficient handling of large data volumes. The results show a significant contrast to those reported for ElGamal in [

7], where the quadratic complexity constrains its practical applicability.

The article is organised as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical foundations of Damgård-Jurik and the Mehnaz protocol, alongside our proposed implementation.

Section 3 highlights the advantages of scalability achieved through reduced communication and computational complexity.

Section 4.2 discusses the results obtained from the local experimental implementation. Finally,

Section 5 provides concluding remarks and explores practical implications, offering recommendations for future improvements such as key generation optimisation and decentralised coordination strategies.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this section, we present the foundational concepts and cryptographic mechanisms that underpin the design and implementation of the proposed secure summation protocol. The framework is structured to offer a comparative analysis between existing approaches and the protocol introduced in this work, highlighting both theoretical robustness and practical applicability. We begin by reviewing the protocol proposed by Mehnaz et al., which uses the ElGamal cryptosystem to enable secure multiparty aggregation. Despite its notable resistance to collusion, this approach suffers from scalability limitations due to its quadratic complexity and reliance on a central trusted server. To address these limitations, we explore the principles of homomorphic encryption, with particular attention to the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem, an extension of the Paillier scheme offering enhanced additive homomorphic capabilities. Additionally, we incorporate Schnorr’s noninteractive zero-knowledge proofs (NIZK) to ensure result verifiability without compromising input privacy. The theoretical exposition provided here laid the groundwork for the protocol proposed in this study and justifies the architectural decisions taken to improve efficiency, scalability, and security in distributed settings.

2.1. Protocol Proposed by Mehnaz et al.

The protocol introduced by Mehnaz et al. [

5] is based on the ElGamal cryptosystem and supports secure summation among multiple parties, resisting collusion by up to

participants. Each data element must be encrypted in successive layers using the public keys of all participants, resulting in a computational complexity of

and a communication overhead estimated at

messages. However, this estimate excludes the key-sharing phase, which imposes additional costs.

Furthermore, the model assumes the presence of a trusted server under the “honest-but-curious” paradigm, acting as a “trusted third party” whose role is to collect encrypted data and disseminate the aggregated results to the involved participants. This intermediary entity adheres to the protocol but endeavours to extract as much information as possible from the data transactions.

However, a notably desirable feature in any secure multiparty summation protocol is the elimination of such intermediaries. The reliance on a central coordinator inherently limits the applicability of this scheme in decentralised settings. See [

7] for evidence that illustrates how quadratic complexities can significantly affect the performance of the protocol.

2.2. Homomorphic Encryption

Homomorphic encryption enables computations on encrypted data without the need to decrypt it beforehand. This property is fundamental to secure multiparty computation, as it facilitates the processing of sensitive information without exposing its content [

8].

2.3. Damgård-Jurik Cryptosystem

The Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem is a generalisation of the Paillier cryptosystem, offering enhanced homomorphic properties. It operates on the ring , where n is an RSA modulus and s is a positive integer, making the operational ring adaptable to different scenarios.

Homomorphic Properties

The Damgård-Jurik encryption scheme builds upon, or more precisely extends, the Paillier cryptosystem, offering improved homomorphic characteristics that permit the addition and scalar multiplication of encrypted data without decrypting intermediate results. This makes it particularly suitable for secure aggregation tasks in multi-party environments, ensuring confidentiality.

-

Homomorphic Addition

If

and

denote the encryptions of

and

respectively, the Damgård-Jurik scheme enables computation of:

-

Scalar Multiplication

It also supports the multiplication of an encrypted message by a scalar:

where

k is a scalar and

m is the message.

These properties enable efficient computation over encrypted datasets without decryption.

The following describes the key generation, encryption, and decryption algorithms of the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem.

Key Generation

Input: Security parameter

Output: Public key , private key

Select large primes p and q such that

Compute and define

Compute

Select a generator of suitable order

Define auxiliary function

Compute

Return: Public key , private key

One question that might arise when analyzing this algorithm (specifically, the key generation step) concerns the computability of the function . In particular, how is it ensured that the division within this expression is always feasible and well-defined?

Due to the properties of

(the least common multiple of

and

) and the choice of generator

g in step 4, the expression

will always yield a result of the form:

It is evident that the result is always an integer k, with no risk of division being undefined or invalid.

Encryption

Input: Message , public key

Output: Ciphertext c

Select random

Compute

Return:c

Decryption

Input: Ciphertext c, private key

Output: Message m

Compute

Retrieve

Return:m

Security

The security of this scheme is underpinned by the Decisional Composite Residuosity (DCR) assumption.

This implies that decrypting a message requires solving a mathematical problem closely tied to the structure of n (the product of two primes). The theorem affirms that only those who possess the secret prime factors of n can "unravel" the operation to systematically recover both the original message x and the random component r. Without this knowledge, distinguishing between encrypted and random ciphertexts is as hard as solving the DCR problem, thereby ensuring cryptographic security.

2.4. Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proof of Schnorr

The Schnorr NIZK (Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge) proof is a non-interactive adaptation of the original three-step Schnorr identification scheme, made non-interactive through the Fiat-Shamir heuristic. It enables a prover to demonstrate knowledge of a discrete logarithm without disclosing any information about its value [

6].

The protocol operates within a cyclic group G of prime order q, with generator g. The prover’s public key is , where x is the private key. The Schnorr NIZK proof proceeds as follows:

The prover selects a random and computes .

The prover computes the challenge , where H denotes a cryptographic hash function.

The prover computes the response .

The proof consists of the tuple .

The verifier accepts the proof if and only if .

As highlighted by Agal et al. in [

9], noninteractive zero-knowledge proofs offer significant advantages in authentication systems. In our SMPC context, these benefits extend to ensuring the correctness of computations while preserving the privacy of individual inputs.

2.5. Security Considerations of Protocol Proposed

The SMPC protocol built on Damgård-Jurik encryption ensures privacy against collusions involving up to parties. As long as at least two parties remain honest, their individual values cannot be determined, as the additive homomorphism conceals the data within the encrypted sum.

Table 1 presents a concise analysis on the resilience of Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem against various cyberattack scenarios.

The security of Schnorr’s NIZK in our system is based on the discrete logarithm assumption and the random oracle model (for the hash function). Although these assumptions are widely trusted in current cryptographic practice, it is important to note that they are not secure in post-quantum contexts.

Moreover, the implementation must carefully handle the generation of randomness and the protection of private keys to prevent side-channel attacks.

By integrating Schnorr’s NIZK into our Damgård-Jurik-based SMPC protocol, we achieve a balance between computational efficiency, proof conciseness, and the robust security properties required for privacy-preserving multiparty computations.

2.6. Algorithm of the Proposed Protocol with Damgård-Jurik

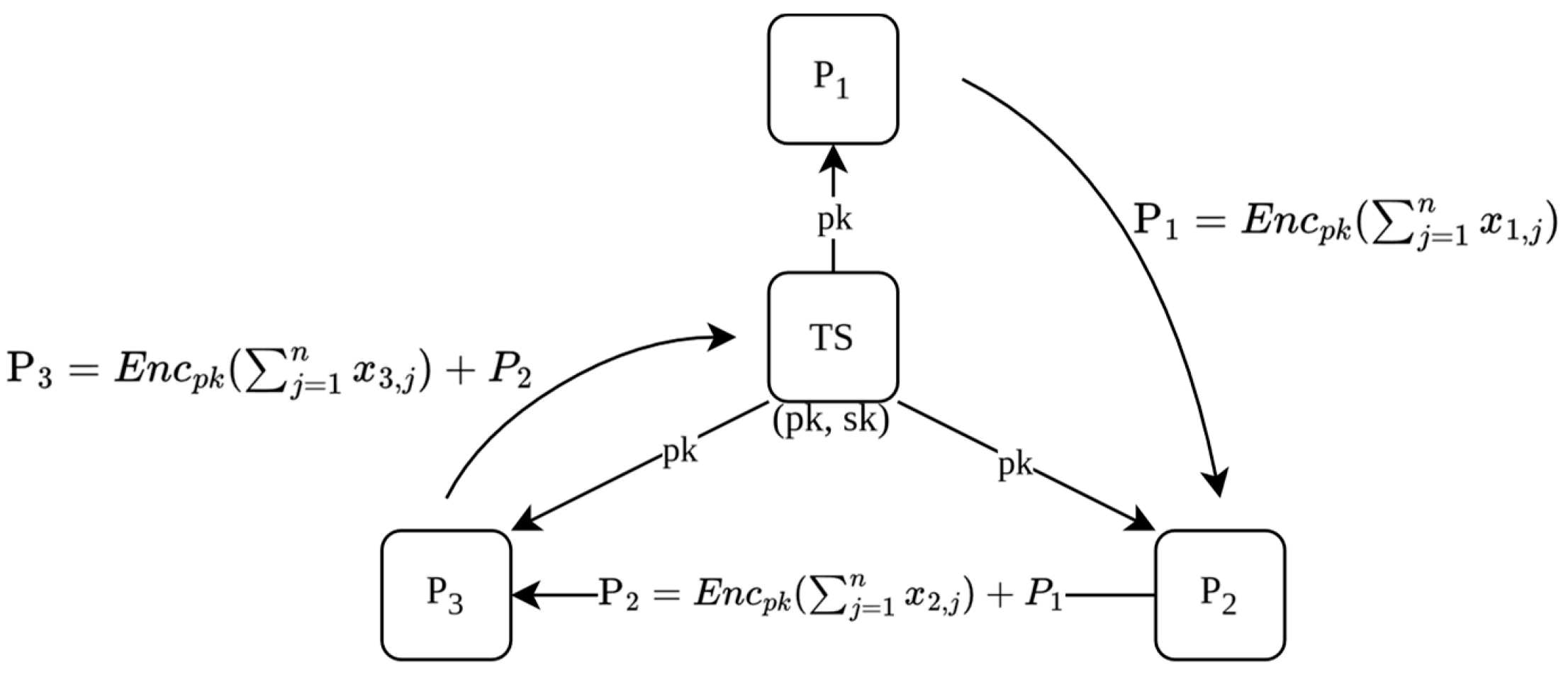

For the proposed protocol, we consider a minimum configuration of three parties (, , and ), together with a trusted server or mediator, hereafter referred to as the Trusted Server ().

Initialization, Encryption, and Homomorphic Addition

The mediator generates a public-private key pair, distributes the public key among all parties, and each party uses it to encrypt their local data. These encrypted values are then homomorphically summed, and the aggregated result is returned to the mediator (see

Figure 1).

|

Algorithm 1 Initialization, Data Encryption, and Generalized Homomorphic Summation |

- 1:

Input: Public key , private key

- 2:

Output: Homomorphic sum y sent to the mediator - 3:

Initialization: - 4:

The mediator generates the Public Key and Private Key

- 5:

The mediator distributes the public key to all parties , for

- 6:

Local Computation and Encryption: - 7:

for each party () do

- 8:

computes its local sum:

- 9:

encrypts its local sum using the public key:

- 10:

end for - 11:

Homomorphic Summation: - 12:

-

Initialize the encrypted accumulated result .

(Identity element for multiplication)

- 13:

for each party () do

- 14:

multiplies its encrypted value with the current accumulator:

- 15:

end for - 16:

Result Transmission to Mediator: - 17:

The final party sends y to the mediator |

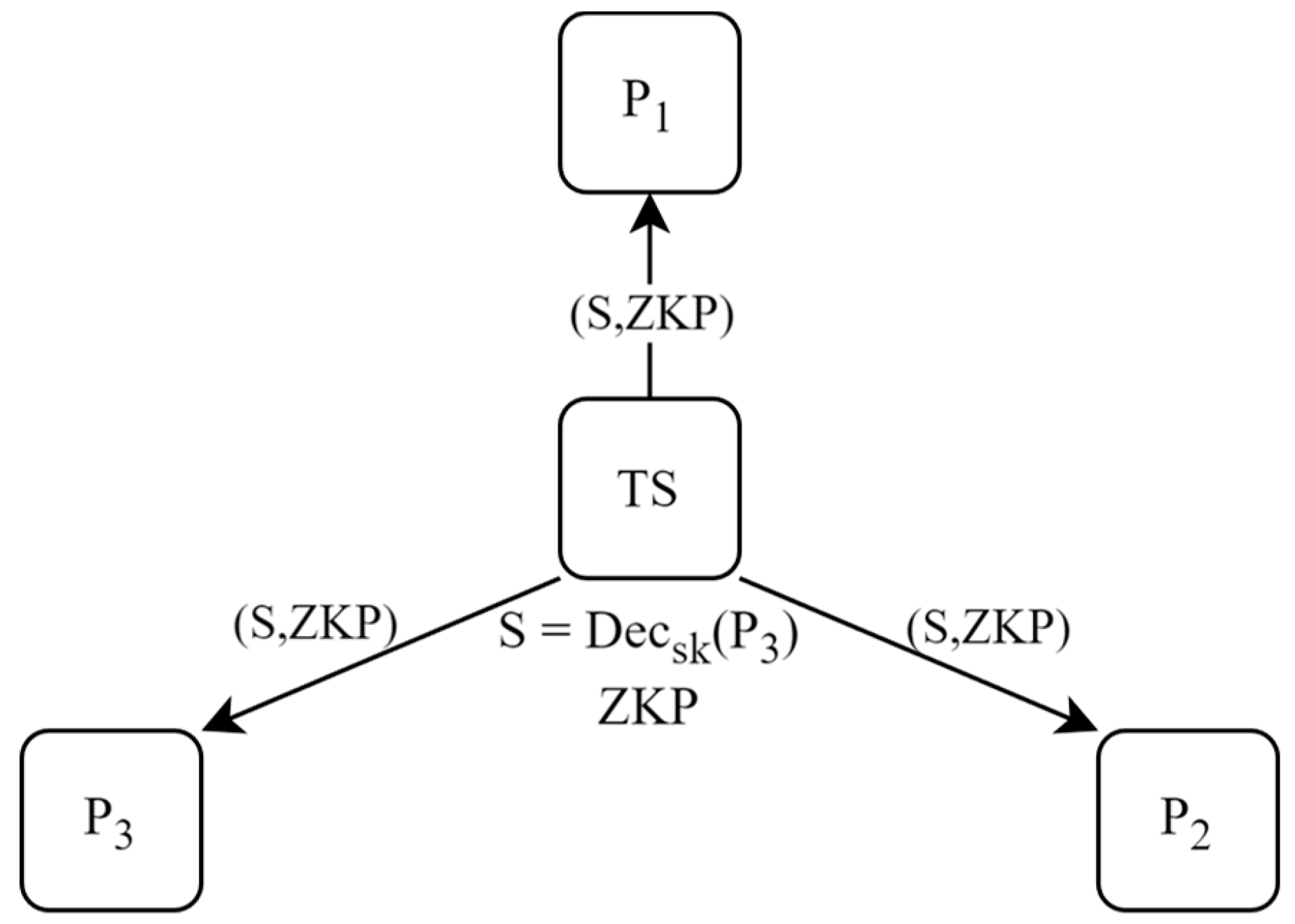

Decryption and Verification

The mediator decrypts the total sum and generates a Schnorr-type zero-knowledge proof to verify the integrity of the result; see [

10].

|

Algorithm 2 Decryption and Verification using Schnorr Proof |

- 1:

Input: Homomorphically encrypted sum , private key

- 2:

Requirements: g and n

- 3:

Output: Decrypted sum and verification via Schnorr proof - 4:

The mediator decrypts :

- 5:

The mediator generates such that: - 6:

is randomly chosen - 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

The mediator sends to all parties

- 11:

for each party do

- 12:

Party verifies whether

- 13:

if equality holds then

- 14:

The proof is valid - 15:

else

- 16:

The proof is invalid - 17:

end if

- 18:

end for |

The following diagrams illustrate the flow of information throughout the multi-party protocol. The initial diagram outlines the stages from key generation to data encryption and transmission, safeguarding individual data privacy. The subsequent diagram, corresponding to

Figure 2, explains the decryption of the total sum and the verification of its integrity using a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP). These procedures ensure that the result remains unchanged, fostering trust in the system without compromising individual data.

3. Comparative Evaluation of Communication and Computational Complexity

In the design and analysis of cryptographic protocols, two fundamental dimensions determine their efficiency and practical feasibility: communication complexity and computational complexity. These metrics enable performance evaluation both in terms of the volume of exchanged data and the computational effort required for secure execution.

Communication complexity refers to the amount of data that must be exchanged between the parties involved (N) to perform a cryptographic computation. It can also be interpreted as the total number of messages transmitted. This factor is crucial in techniques such as Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE), where it directly impacts network latency and resource consumption.

The most relevant models of communication complexity include:

Linear complexity: Denoted by , where the number of messages grows proportionally to the number of participants. Each entity exchanges a constant number of messages, thereby enhancing scalability.

Quadratic complexity: Represented by , arises when each participant must communicate with every other, as in protocols requiring exhaustive interaction to preserve security in distributed computations.

Logarithmic and sublinear complexity: Denoted by and , respectively, these complexities emerge in optimized protocols that employ hierarchical structures or efficient networks to reduce inter-party communication.

Evaluating communication complexity is essential to ensure that a protocol can scale efficiently in settings with many participants and large data volumes.

On the other hand,

computational complexity refers to the processing resources required to execute a cryptographic protocol, including CPU time, arithmetic operations, and memory usage, among others [

11].

Processing: Includes operations such as encryption, decryption, key generation, digital signing, and verification. These processes may be intensive, depending on the underlying algorithm.

Resources: Protocols with high computational complexity require more processing power and memory capacity, posing challenges in resource-constrained devices such as sensors, mobile platforms, or IoT devices.

Together, communication and computational complexity define the operational cost of cryptographic protocols. Analysing both dimensions allows for optimal trade-offs between security, efficiency, and scalability, critical for the development of practical and secure cryptographic solutions.

3.1. Communication Complexity of the Proposed Protocol as a Function of N

When extending the protocol for , it can be generalised as follows:

The mediator shares the public key with the N parties: N messages.

Each pair of consecutive parties exchanges encrypted data: messages.

The last party sends the aggregate to the mediator: 1 message.

The mediator sends the result and the noninteractive challenge to all parties: N messages.

Thus, the generalised communication cost is:

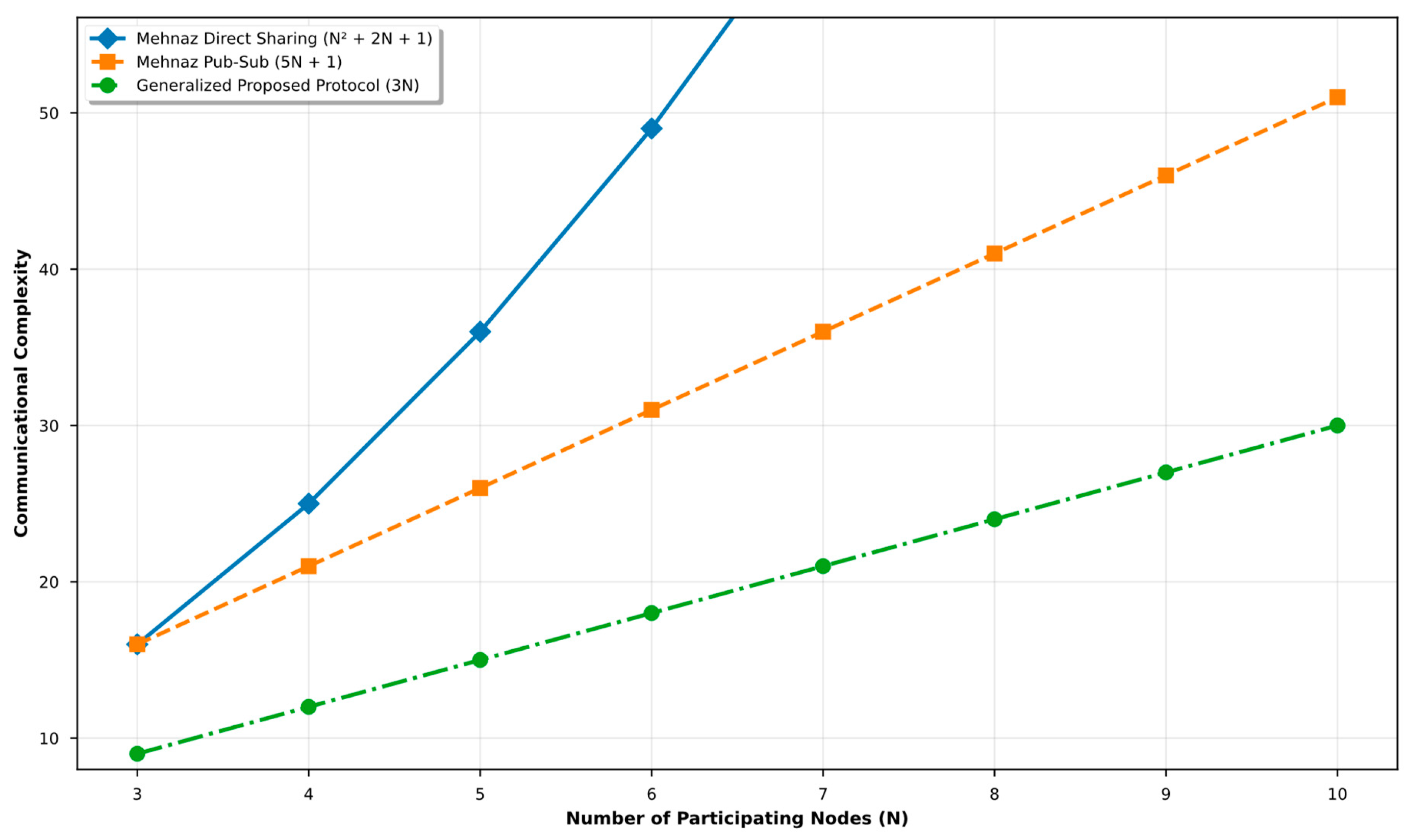

Regarding the communication complexity of the protocol proposed by Mehnaz et al., their article specifies a general complexity of , with N representing the number of participants.

A relevant observation is that this expression does not fully account for all the phases of the protocol, notably omitting the key-sharing stage conducted by both the trusted server and the participating nodes. This omission introduces additional communication costs that must be considered for a realistic analysis of the efficiency of the protocol.

Two alternative approaches are proposed below to model the key-sharing phase and incorporate these additional costs into the communication complexity analysis:

Direct-sharing method: In this scheme, each participant, including the mediator, communicates directly with each other to share keys. This results in exchanges, added to the initially considered. The total complexity becomes , indicating a quadratic growth with additional linear and constant terms, which negatively affects scalability.

Publish-subscribe (Pub-Sub) model: In this approach, each participant publishes their key on a shared channel accessible to all others, requiring N write operations. Subsequently, each participant reads the keys of the others, generating N additional reads. This introduces exchanges for key sharing, which added to the initial results in , producing linear complexity with an additional constant term. This model improves communication efficiency and enhances the scalability of the protocol.

Figure 3 presents the communication complexity curves for both proposed methods, alongside that of the generalised protocol proposed here. This comparison provides a visual perspective on the real impact of architectural decisions on the total communication cost of the system.

Figure 3 clearly shows that omitting the key-sharing stage conceals the true complexity of the system communication, leading to an underestimation in the analysis of communication costs.

3.2. Computational Complexity of the Proposed Protocol as a Function of N

From a computational standpoint, the efficiency of multi-party cryptographic protocols is evaluated based on the number of operations involved in each phase. The growth of these operations as a function of the number of participants (

N) allows classification into linear

, quadratic

, or higher-order complexity. Formally, the total cost of the protocol is expressed as follows.

where:

denotes encryption operations.

denotes decryption operations.

denotes homomorphic transformations.

Proposed Protocol based on Damgård-Jurik

This protocol follows a five-stage structure:

Key generation: performed by the mediator (1 operation).

Individual encryption: each participant performs one encryption (n operations).

Sequential aggregation: requires homomorphic operations.

Final decryption: performed by the trusted entity (1 operation).

Non-interactive verification: each participant conducts verification checks (n operations).

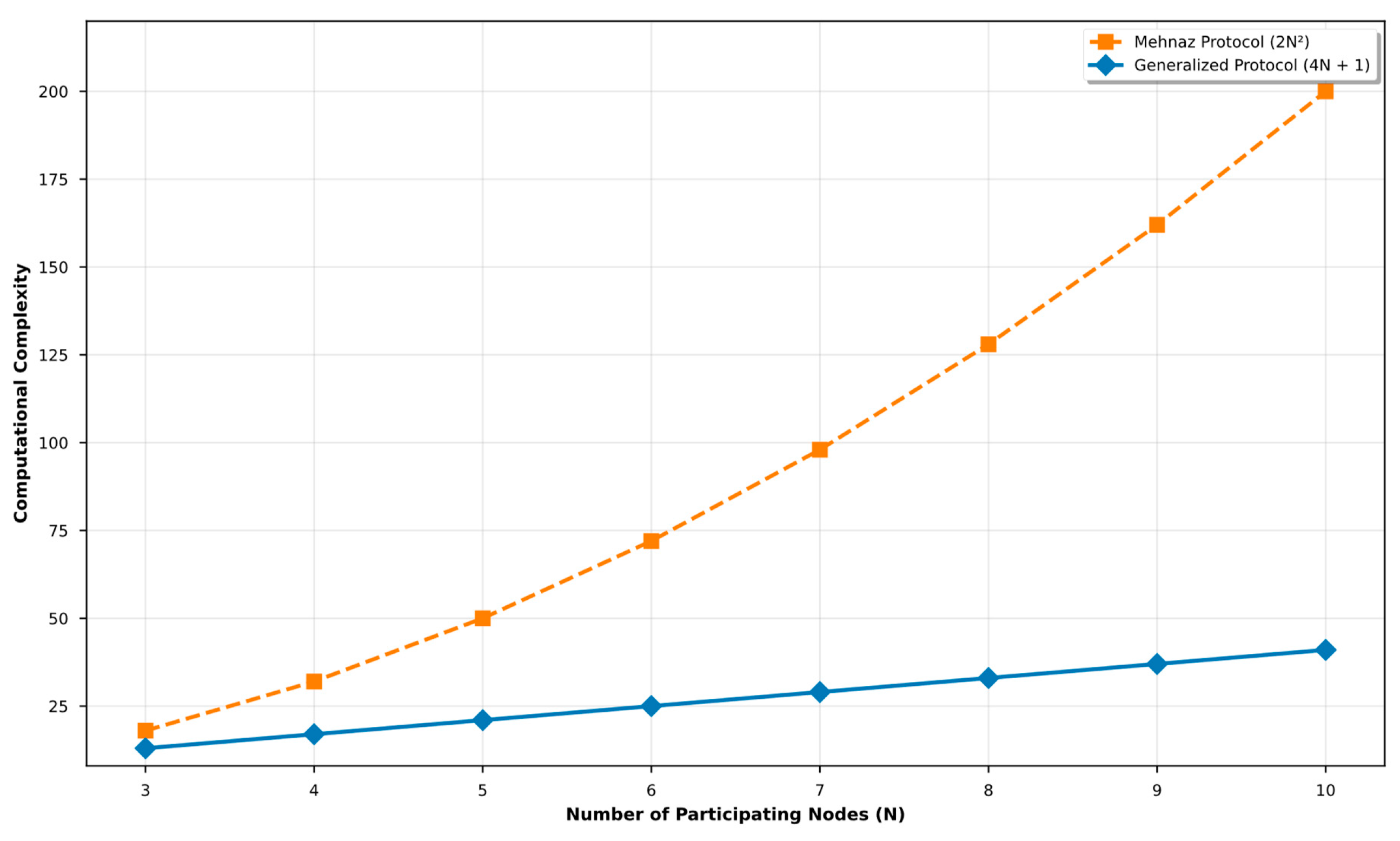

The total computational cost is

The unidirectional aggregation structure ensures that the protocol exhibits linear computational complexity .

Mehnaz et al.’s Protocol based on ElGamal

The Mehnaz et al. scheme is built on ElGamal and comprises three main stages:

Distributed key generation: each participant generates a public-private key pair (N operations).

Parallel encryption: operations are executed.

Multiple re-encryptions: transformations are required.

The total computational complexity is:

The graphical analysis in

Figure 4 illustrates that the protocol of Mehnaz et al. exhibits quadratic complexity

in both variations, limiting its scalability in resource-constrained environments, as also noted in [

7].

In contrast, the proposed Damgård-Jurik based protocol maintains linear complexity , due to its sequential structure and efficient use of homomorphic operations. This makes it suitable for distributed systems with computational constraints, ensuring enhanced scalability and efficiency in multiparty cryptographic schemes.

4. Proof of Concept in a Local Environment

To empirically validate the feasibility and efficiency of the proposed secure summation protocol, this section presents a proof-of-concept implementation conducted in a controlled local environment. The goal is to evaluate the performance of the protocol under realistic computational constraints and varying data distributions. To this end, a set of virtual machines was configured to emulate a decentralised setting with multiple participating entities and a trusted mediator. The implementation evaluates two distinct data partitioning strategies—vertical and horizontal—that simulate different real-world data ownership and distribution scenarios. By analysing execution times across varying dataset sizes, this proof-of-concept provides critical insights into the scalability and operational practicality of the protocol in secure multi-party computations.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the protocol, a local environment consisting of six virtual machines was configured with the following specifications:

Operating System: Ubuntu Server 24.04 LTS

CPU: Each machine utilized a Ryzen 5 3500U processor.

RAM: 2 GB per machine.

Storage: 10 GB per machine.

Five of the machines served as participating nodes in the protocol, while the sixth acted as the mediator node. The system was implemented using Python 3.12.3, with ZeroMQ enabling inter-party communication

1. Encryption was performed using the library ‘damgard-jurik 0.0.3’

2.

The study used five data sets, generated specifically to evaluate the protocol experimentally, each containing nine attributes. Experimental validation used five multidimensional datasets (9 attributes per case), with sizes progressively ranging from to records. The data sets were segmented using hybrid vertical-horizontal partitioning, allowing an evaluation of the efficiency of the protocol under both data distribution schemes.

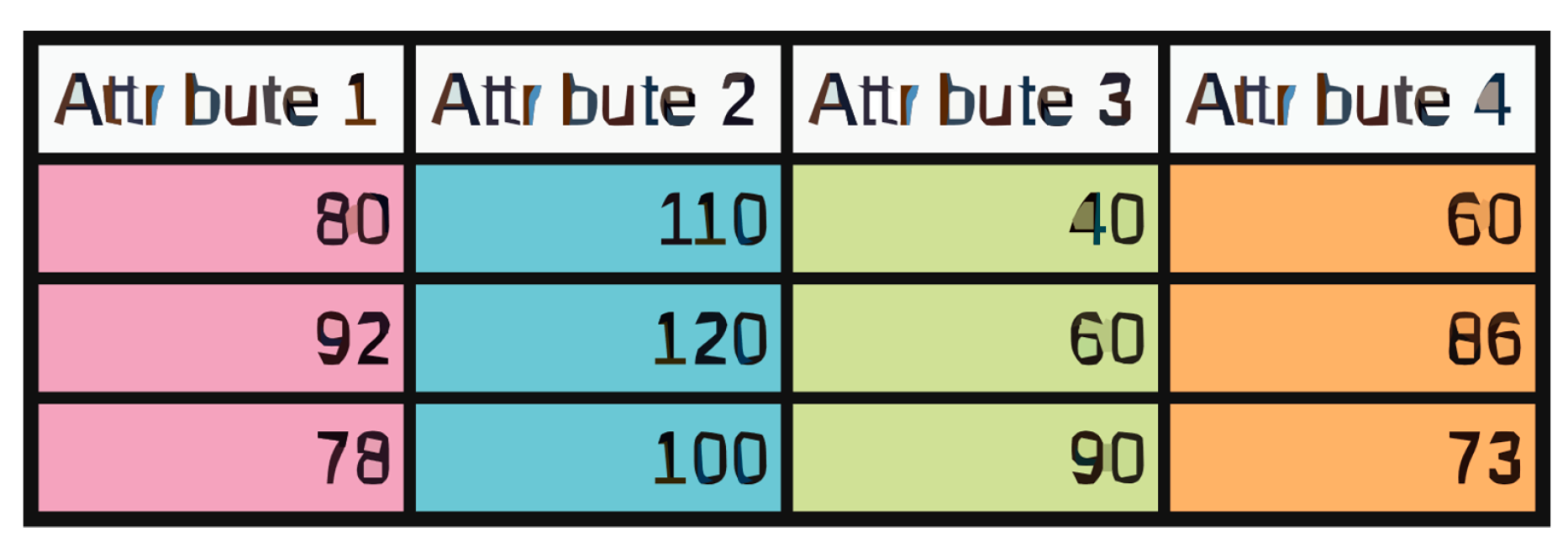

Figure 5.

Vertical partitioning scheme used in the experiment. Each color represents a partition.

Figure 5.

Vertical partitioning scheme used in the experiment. Each color represents a partition.

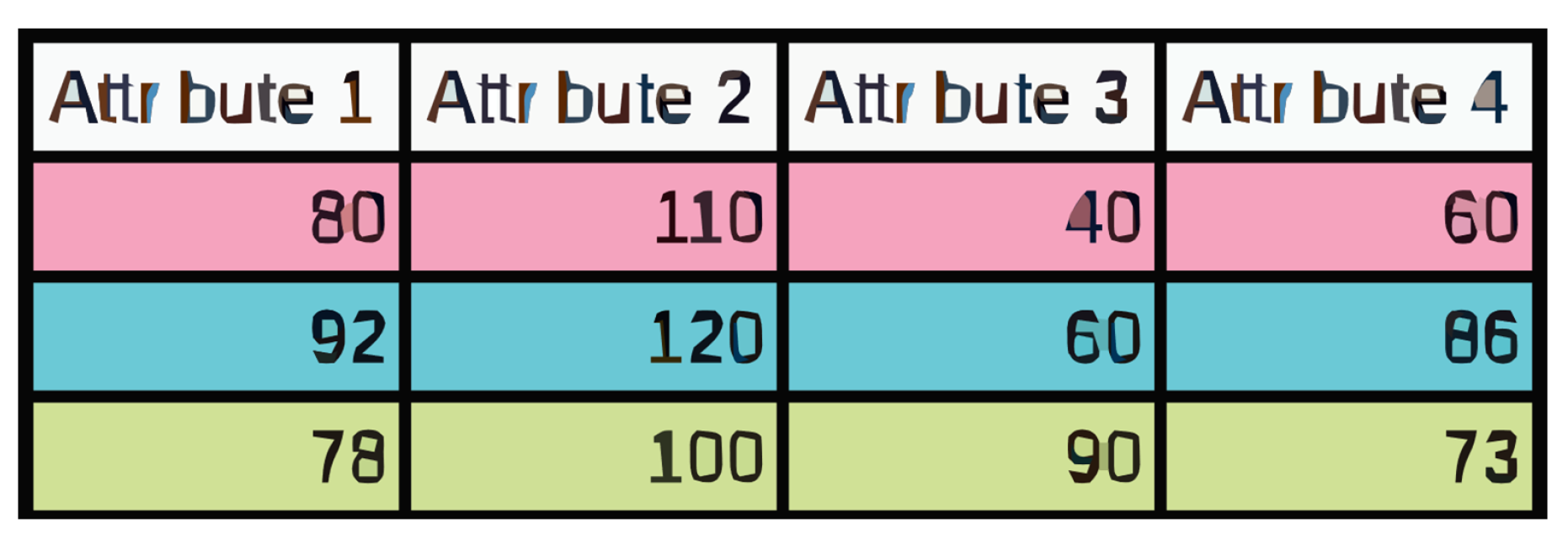

Figure 6.

Horizontal partitioning scheme used in the experiment. Each color represents a partition.

Figure 6.

Horizontal partitioning scheme used in the experiment. Each color represents a partition.

4.2. Performance of the Proof of Concept

This section examines the two proposed partitioning schemes (vertical and horizontal) utilised in the proof-of-concept. It presents graphs that illustrate the execution times for each case, accompanied by a detailed analysis explaining the observed behaviours and implications of each method.

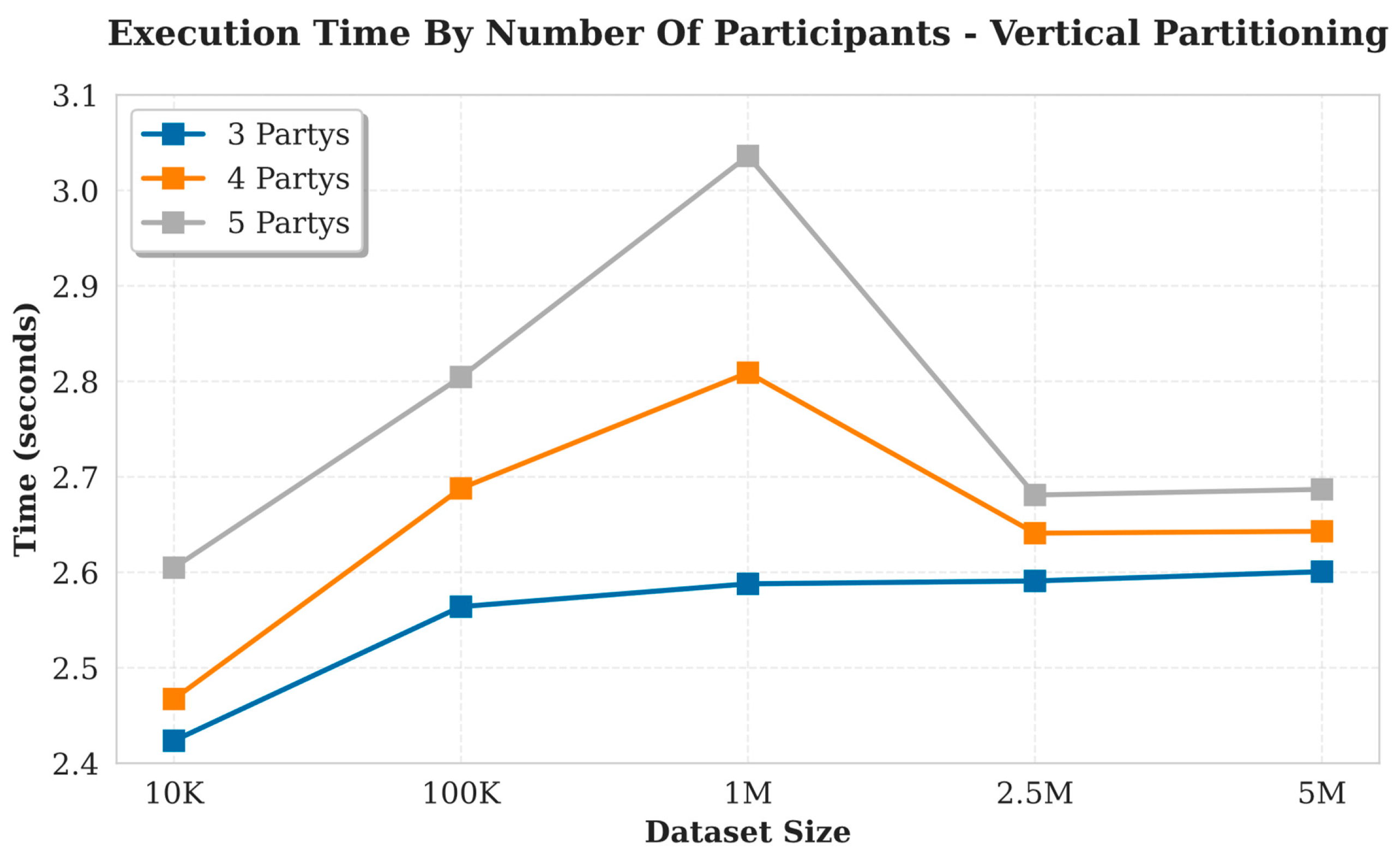

Vertical Partitioning

Figure 7 displays the execution times for various data sets in vertical partitioning. The x-axis indicates the size of the data set (in rows). The figure shows an ascending trend; however, beginning with the 2.5M rows dataset, execution times decrease significantly. This behaviour is attributed to a balanced data distribution: Larger data sets allow data loads to be distributed more uniformly and efficiently among participating nodes. As a result, the numerical values to be encrypted become more uniform in length, reducing biases in computational effort among participants.

Horizontal Partitioning

Figure 8 presents the execution times for various data sets in a horizontal partitioning scheme. Again, the x-axis represents the number of rows in the datasets. The curves show a nearly linear behaviour, attributed to the consistent digit lengths of encrypted values throughout the encryption phases. In this scheme, since the dataset is uniformly distributed, each participant receives a partition with a similar structure and characteristics. This leads to input values of approximately constant length for encryption, resulting in uniform processing loads and execution times that scale linearly with data set size.

4.3. Result of the Proof of Concept

The protocol demonstrated its ability to efficiently handle large datasets, provided that the summation is performed locally. This local aggregation results in a single value per party, which is then encrypted using homomorphic addition. This technique enables the combination of multiple encrypted values without the need for decryption. Although this implementation was tested only as a proof-of-concept, it was observed that the generation of public and private keys is the most time-intensive task, primarily due to key bit length. For this reason, this process is not reflected in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, as its duration depends on the hardware and is usually performed in advance.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduces a secure summation protocol based on the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem, implemented and evaluated within an experimental setup that considers both vertical and horizontal partitioning. Compared to previous work, such as the collusion-resistant secure summation protocol leveraging ElGamal [

5], the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem offers notable improvements in privacy and efficiency. These enhancements stem from its homomorphic properties and the conceptual refinement of encrypting only a single value per party, achieved through local data summation.

Furthermore, the practical feasibility of this protocol is reinforced by proof-of-concept and performance evaluation, demonstrating its effectiveness and efficiency in handling large-scale datasets. The findings emphasise the protocol’s ability to maintain data privacy through encryption and ensure result integrity via Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proofs (NIZK). However, several challenges emerge, including the substantial computational cost of key generation and distribution, as well as the need for precise synchronisation between parties, although the latter can be addressed using orchestration tools or communication frameworks such as ZeroC-Ice

3.

Importantly, this work has successfully reduced both communication and computational complexity from a quadratic order to a linear order, achieving a generalised and more scalable version of the protocol originally proposed by Mehnaz et al. This improvement is made possible by the integration of additive homomorphic cryptography, which enables efficient secure computation across decentralised multiparty environments.

In conclusion, the generalised protocol designed on the Damgård-Jurik cryptosystem provides a robust and secure framework for settings that require secure distributed computation. The results and evaluations presented here support its potential practical applicability. However, further research is encouraged to optimise and refine the protocol to enhance its efficiency and adaptability in various deployment scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.M., J.F.L. and F.E.J.; methodology, C.C.M. and J.F.L.; validation, C.C.M., J.F.L. and F.E.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.M., A.B.M. and M.B.L; writing—review and editing, J.F.L., C.C.M., F.E.J., A.B.M. and M.B.L; supervision, J.F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded (partially) by Dirección de Investigación, Universidad de La Frontera, Grant PP24-0027.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Damgård, I.; Jurik, M. A generalization, a simplification and some applications of Paillier’s probabilistic public-key system. In Proceedings of the Public Key Cryptography: 4th International Workshop on Practice and Theory in Public Key Cryptosystems, PKC 2001 Cheju Island, Korea, February 13–15, 2001 Proceedings 4. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2001, pp. 119–136.

- Paillier, P. Paillier Encryption and Signature Schemes., 2005.

- Kleinjung, T.; Aoki, K.; Franke, J.; Lenstra, A.K.; Thomé, E.; Bos, J.W.; Gaudry, P.; Kruppa, A.; Montgomery, P.L.; Osvik, D.A.; et al. Factorization of a 768-bit RSA modulus. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2010: 30th Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 15-19, 2010. Proceedings 30. Springer, 2010, pp. 333–350.

- Luo, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, L. An image encryption method based on elliptic curve elgamal encryption and chaotic systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38507–38522.

- Mehnaz, S.; Bellala, G.; Bertino, E. A secure sum protocol and its application to privacy-preserving multi-party analytics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM on Symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies. ACM, 2017, pp. 219–230.

- Hao, F. Schnorr Non-interactive Zero-Knowledge Proof. RFC 8235, RFC Editor, 2017.

- Ranbaduge, T.; Vatsalan, D.; Christen, P.; et al. Secure multi-party summation protocols: Are they secure enough under collusion? Trans. Data Priv. 2020, 13, 25–60.

- Acar, A.; Aksu, H.; Uluagac, A.S.; Conti, M. A survey on homomorphic encryption schemes: Theory and implementation. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–35.

- Agal, M.; Kishan, K.; Shashidhar, R.; Vantmuri, S.S.; Honnavalli, P. Non-interactive zero-knowledge proof based authentication. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Mysore Sub Section International Conference (MysuruCon). IEEE, 2021, pp. 837–843.

- Agal, M.; Kishan, K.; Shashidhar, R.; Vantmuri, S.S.; Honnavalli, P. Non-interactive zero-knowledge proof based authentication. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Mysore Sub Section International Conference (MysuruCon). IEEE, 2021, pp. 837–843.

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Barbhuiya, M.A.; Saikia, M. Multiple Encryption using ECC and its Time Complexity Analysis‖. International Journal of Computer Engineering In Research Trends 2016, 3, 568–572.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).