Wolpe and Lazarus introduced the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) in 1966 [

1]. They described the administration of the SUDS through the following interaction with a hypothetical patient:

Think of the worst anxiety you have ever experienced, or can imagine experiencing, and assign to this the number 100. Now think of the state of being absolutely calm and call this zero. Now you have a scale. On this scale how do your rate yourself at this moment? (p. 73).

Wolpe referred to each unit of measurement as a “sud” (p. 73), or a subjective unit of disturbance, with which patients communicated the severity of their distress throughout behavior therapy. In 1981, Wolpe & Wolpe [

2] anchored the SUDS with the descriptive terms displayed in

Table 1:

Consequently, the SUDS afforded practical advantages in clinical and research settings. First, it offered a means to collect within- and between-session ratings in a dynamic therapeutic environment across disorders. In recent studies, the SUDS has been used at the start and end of sessions [

3], at multiple timepoints throughout sessions, and immediately before and after exposures [

4]. Second, it allowed clinicians to rank-order fears on a hierarchy, a graduated list of anxiety-provoking situations that frequently guided exposure-based treatment [

5]. Third, it helped prevent exposure-based treatment from becoming too overwhelming. For instance, if a patient reported a SUD for one exposure as a 20 but the next as an 80, a clinician could develop intermediate challenges that progressively intensified the experience [

6]. Thus, SUDS scores directly influenced critical clinical decisions, such as determining the pace of exposure therapy, assessing treatment readiness, judging session effectiveness, and even defining treatment success (e.g., the common 50% reduction heuristic for habituation) [

7].

With a convenient measure applicable to clinical and research settings, the SUDS was swiftly integrated into anxiety research throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Pioneers in anxiety research found that within- and between-session decreases in the SUDS related to habituation during the treatment of OCD and agoraphobia [

8], while dissertations using the SUDS showed higher distress for teachers exposed to unruly classroom behaviors than teachers who were not [

9]. Wolpe himself argued for the SUDS as both a clinical tool [

6] as well as a research tool, which he used widely in his own seminal investigations in exposure work [

10].

The SUDS continues to be used in modern psychology, primarily for measuring state negative affective intensity within and between therapy sessions [

11,

12] and as a measure of subjective fear, anxiety, and discomfort [

13,

14] across various settings [

15,

16]. While other scales are often interminable, costly, and measure trait characteristics (vs states), the SUDS provides a method of measuring unstable constructs like distress and anxiety in real-time [

17]. In several training and practitioner-friendly resources, the SUDS continues to be the de facto method of generating modern fear hierarchies [

7,

18,

19]. Indeed, the SUDS, along with a 50% reduction cutoff, is often used to signify that habituation to a feared stimulus has occurred [

20,

21]. Clinicians rely on these SUDS ratings moment-to-moment to gauge patient tolerance, decide whether to continue, intensify, or cease an exposure task, and to collaboratively build fear hierarchies that form the backbone of treatment plans [

20]. The SUDS has also played an important role in basic and applied research clarifying exposure therapy’s mechanistic underpinnings [

22]. For example, in a study concluding that habitation is a separate phenomenon from extinction learning, SUDS ratings of conditioned stimuli were one of the measures [

23]. As such a popular and ubiquitous measure, a careful examination of its construct validity is warranted.

In clinical practice, accurate measurement of patient distress is fundamental to treatment planning, progress monitoring, and outcome evaluation. The SUDS has been widely adopted in exposure-based treatments across anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD, where clinicians rely on it to calibrate exposure intensity, determine habituation, and make moment-to-moment treatment decisions. However, as Messick (1995) [

24] and Cronbach and Meehl (1955) [

25] established, meaningful clinical application requires construct clarity before empirical utility can be established. Our theoretical critique through the rigorous Strong Program of Construct Validation [

26] addresses a critical gap affecting everyday clinical practice—namely, that clinicians using the SUDS to guide treatment decisions may be measuring qualitatively different phenomena across patients, sessions, or even within the same exposure exercise. This theoretical ambiguity undermines treatment standardization, complicates clinical training, and potentially compromises patient outcomes. By examining the SUDS through a rigorous theoretical framework, we provide the foundation necessary for improving research, clinical assessment practices, and patient care.

Validity Studies

Construct validation—the “integrative and evaluative judgement” that “supports the adequacy and appropriateness of inferences and actions based on test scores” is a necessary step for establishing the interpretation of scores [

27] (p. 13). As it relates to the SUDS, only three studies examined construct validity directly. The earliest attempt explored the relationship between the SUDS, digit temperature, and heart rate in twenty college students [

28]. Participants watched a 3-minute video of a venous cutdown procedure, during which SUDS were obtained at 30-second intervals. Average heart rate, left-hand, and right-hand temperature correlated with SUDS significantly. The authors concluded that peripheral vasoconstriction is more sensitive to subjective anxiety than heart rate, and that the results support the continued use of the SUDS in clinical and research settings.

Nevertheless, this overlooks the possibility that the SUDS was measuring other constructs: Participants may have reported anxiety, distress, disgust, or general autonomic arousal after watching the video of the venous cutdown procedure. The authors reported that the relationship between the left-hand and right-hand correlations and the SUDS were in the predicted direction. But in the absence of theory, their prediction could still have been confirmed if they found a statistically significant inverse correlation between digit temperature and anxiety (especially since at the time of publication the direction of the relationship was not yet established). Their belief in the SUDS and its predictive ability is plainly stated: “Self-report data such as the subjective anxiety scale are frequently the primary outcome measure of interest in clinical behavior therapy and its usefulness is not dependent on concurrent response parameters” (p. 6).

In another attempt to study the SUDS, Kim et al. [

29] analyzed SUDS scores from 61 patients treated with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) at a trauma clinic. At baseline, the authors stated that the SUDS correlated with the Beck Depression Inventory (

r = .28,

p < .05; Beck et al., 1961) and the State Anxiety Scale (

r = .31,

p < .05), which they argued was evidence for convergent validity. They interpreted a non-significant correlation with the Trait Anxiety Scale (

r = .21,

p > .05; Spieberger et al., 1983) as evidence for discriminant validity. They further claimed there were no correlations between SUDS and age (

r = -0.23,

p < .05), education (

r = -.016,

p < .05), or income (

r = 0.12,

p < .05)—interpreted as discriminant validity. In terms of predictive validity, they added that the SUDS at the end of the first session was significantly and positively correlated with the Clinical Global Impression of Change (

r = .32; CGI-C; [

30]). SUDS also correlated with CGI-C at the end of the second (

r = .51) and third sessions (

r = .61). The authors found significant, positive correlations between the SUDS and the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised’s Positive Symptom Distress Index (SCL-90 PSDI; [

31] and Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R; [

32]), both interpreted as evidence of concurrent validity (

rs = 0.50 & 0.46, respectively).

However, many validity interpretations were based on whether a parameter estimate was statistically significant. Unfortunately, this use of

p-values is problematic, as it relies on dichotomous decisions that overlook the strength and theoretical importance of the correlations themselves [

33]. For instance, the authors concluded that the SUDS did not correlate with the Trait Anxiety Scale because the

p-value was not significant—which they interpreted as evidence of discriminant validity—when in fact the size of the correlation (

r = .21) was akin to the correlation between the SUDS and the Beck Depression Inventory (

r = .28) that they concluded was evidence for

convergent validity. Since p-values say little about the magnitude of an effect [

33], their determination of convergent or discriminant validity is inconsistent. While laudable, this investigation lacks a strong foundation for clinicians looking to trust SUDS scores as specific indicators of state distress versus related constructs like depression or stable anxiety traits, highlighting the risk of relying on assessment approaches not grounded in robust, theoretically coherent validation evidence, a necessary step to distinguish evidence-based practice from potentially unsubstantiated claims [

34].

In the absence of a theoretical and empirical understanding of the SUDS, its measurement limitations, and the construct it purports to measure, one cannot interpret positive correlations between anxiety and depression as convergent validity. Again, using

p-values, Kim et al. [

29] claimed that neither age, education, nor income were significant, so these were evidence of discriminant validity. Considering predictive validity, the authors noted that SUDS following the first session predicted SUDS during all subsequent sessions. Nevertheless, these results may all have been artifacts resulting from their last observation carried forward (LOCF) method, which typically involves copying subject data forward in a dataset to fill in missing data. This approach is problematic enough that researchers and statisticians have been skeptical of it for some time [

35], hence several recommendations have been put forth for more sophisticated analyses/designs [

36,

37].

To expand the scope of the SUDS’s clinical utility, Tanner (2012) [

38] investigated emotional and physical discomfort. They used the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2; [

39]) and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; [

40]) with the SUDS to track 182 patients in a hospital setting. They found that emotional SUDS were moderately related to clinician GAF ratings (

r = -.44), Scale A of the MMPI-2 (

r = .35), sum of scales 1 – 3 (

r = .37), and decreased significantly after 3 months of treatment. Physical SUDS did not decrease significantly after treatment. The researchers concluded that “the data provide several pieces of evidence regarding the validity and sensitivity of global SUDS ratings” (p. 33) and that global SUDS ratings are a useful extension of the traditional SUDS scale.

Nevertheless, the foundation for Tanner’s (2012) [

38] argument was the work done by Thyer et al. [

28] and Kim et al. [

29], as well as by supplying several papers that have found correlations between the SUDS and other constructs. What do we make of the correlations between the SUDS and so many constructs, which continues to be demonstrated in numerous papers since then? First, we acknowledge that the SUDS is associated with measurements of stress and anxiety including heart rate and heart variability [

41]. It correlates with several constructs and instruments, including willingness to engage in treatment (r = -.12; [

42]), the Screen for Anxiety and Related Disorders – Youth and Parent reports [

43], the externalizing score on the parent report for the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire [

44], and the Global Distress Tolerance Scale [

45,

46]. Moreover, some research shows that the SUDS predicts between-session exposure therapy treatment outcomes [

47], and that changes in SUDS can predict changes in outcome variables such as OCD severity, functional impairment, and clinician-rated improvement [

48].

Nonetheless, validity evidence requires more than just a collection of correlations—it also requires theoretical justification [

25,

49]. Thus, a deeper examination of its construct validity is overdue. To modernize the field’s psychometric perspective on the SUDS, we assessed the SUDS’s focal construct, “distress,” through the Strong Program [

26] and Loevinger's (1957) [

50]process of construct validation. This framework of construct validation has been used extensively for several decades and is recommended by researchers and modern factor analytic texts [

51,

52]. Its primary purpose is to help researchers determine if a measure belongs within a nomological network, or a related network of constructs and variables [

25]. So it is within this framework that one can evaluate whether enough research and theoretical work suggests that the SUDS is a suitable measure of distress. Our assessment is followed by recommendations for research and clinical practice.

Strong and Weak Construct Validation

Cronbach (1989) [

49] described the Weak Program of construct validation as an exploratory endeavor that captures the correlational relationship between the focal construct and other constructs with little regard for theory. Because the Weak Program relies on exploratory (rather than confirmatory) empirical research, its atheoretical and unsystematic approach provides less convincing support for a construct.

To address the limitations of the Weak Program of construct validation, the Strong Program is a theory-driven framework derived from Loevinger (1957) [

50] and Nunnally (1978) [

53]. It integrates the six categories of construct validation from Messick's (1995) [

24] unified concept of validity and includes three components: Substantive, Structural, and External. A variety of evidence is required at all stages, which build upon each other. If one stage lacks evidence, it must be reevaluated.

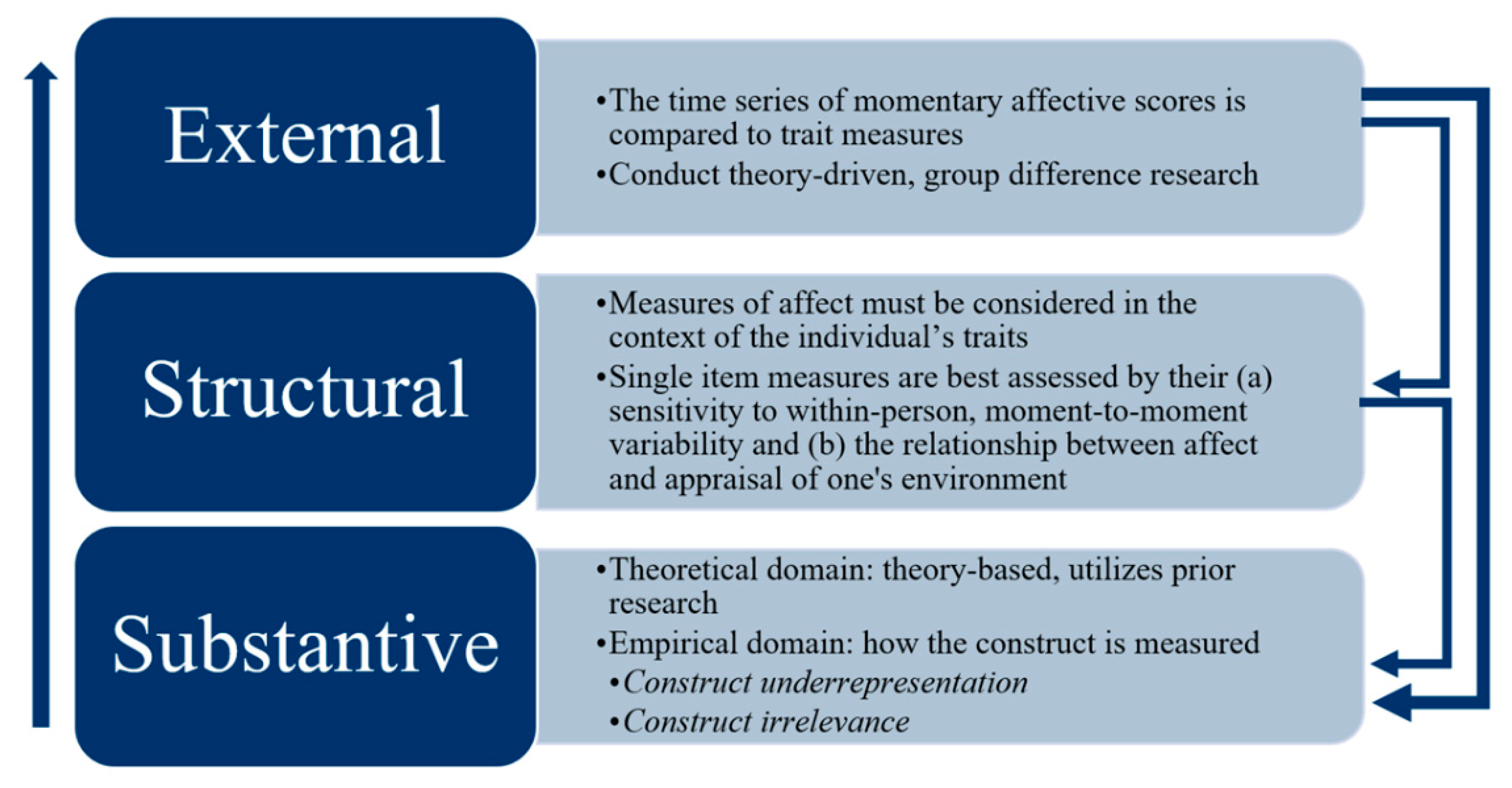

Figure 1 displays these components as building blocks:

Substantive Component

Within the Substantive Component, the theoretical and empirical domains of a construct are identified. A construct’s theoretical domain consists of all that is known about the construct in the literature and is supplemented by the researcher’s observations [

26]. Ideally, the theoretical domain corresponds to a construct’s empirical domain, or all ways that the construct can be operationalized (e.g., brain scans, electrophysiological recordings, behavioral measures, self-reports, etc.). Two threats to construct validity in this stage include construct underrepresentation and construct irrelevance [

24] (Messick, 1995). Construct underrepresentation occurs when measures do not sufficiently account for and represent the theoretical domain of the focal construct [

54]. Construct irrelevance occurs when an assessment captures variability unrelated to the construct’s theoretical domain.

A clinician observing a high SUDS score cannot be certain what specific aspect of the patient's experience it reflects (e.g., fear of the stimulus, general overwhelm, frustration), potentially leading to misinterpretations of the patient's state and misguided clinical interventions. This is highlighted by applying the Strong Program to “distress.” Without explicitly defining the domain (distress vs anxiety), it is unclear what the SUDS measures. For instance, patients are supposed to report the “worst

anxiety” [

1] (p. 66) they ever experienced. But it is called a subjective unit of

disturbance scale and was also encouraged to be used for domains such as “rejection,” “guilt,” “or others like them” (p. 67). This introduced many constructs—anxiety, rejection, guilt, or others—into the theoretical domain, ostensibly under the umbrella term “disturbance.” Yet without an operational definition of disturbance and how that relates to anxiety, the scale risks measuring multiple domains simultaneously and introducing construct irrelevant variance. For instance, someone with both anxiety and depression may have a high SUDS score because of depression, anxiety, or other reasons. By integrating multiple constructs of interest we risk combining the intensity of different affective responses.

The SUDS also fails to define its measurement period, obscuring the construct it purports to measure. Inconsistent prompting (

rate your distress now vs.

rate your peak distress during that exposure) across or within sessions can yield incomparable data, undermining the clinician's ability to accurately track change or therapeutic processes like habituation. For instance, in an investigation of public speaking anxiety, the SUDS was a measure of distress throughout the course of a speech [

55]. In another study measuring eating disorder treatment, the SUDS evaluated distress prior and after eating a feared food, during within-session and between-session habituation [

56]. Different domains measured on different time scales are subject to their own theoretical and empirical examinations. Each of these as a measure of state negative affective intensity requires a theoretical and empirical understanding.

Structural Component

When enough evidence is collected in the Substantive Stage, a construct should be evaluated in the Structural Stage. Here the relationship between the observed variables and the construct of interest is assessed [

26]. Constructs assessed by single-item measures are best assessed by their sensitivity to within-person, longitudinal variability [

57,

58]. In other words, fluctuations in one person’s scores may be a better measure of their affect than comparing their scores to others’ scores. Further, measures of affect must be considered in the context of an individual’s traits [

59]. For instance, while significant fluctuations in affect scores may be unusual for one person, they may be expected in an individual with greater emotional lability. More concretely, someone with OCD may report consistently high anxiety (low within-person variability) but someone with borderline personality disorder may experience a wider range of emotional fluctuation (greater within-person variability).

The SUDS falls short without clear theoretical and empirical operational definitions in the Structural Component. For instance, the within-person variability of distress as measured by the SUDS may differ depending on whether someone experiences anxiety, not just right, or hopelessness. Relying on a single SUDS number may cause clinicians to miss crucial patterns or sources of distress variability (e.g., lability vs. stable high anxiety), hindering a nuanced understanding of the patient's affective state and response to treatment. Also, the construct irrelevant variance in the Substantive Component carries through to the Structural Component. For example, a score after an exposure therapy session may be contaminated by the many different constructs the SUDS is measuring. Consequently, the extent and the source of within-person variability remains unexplained.

External Component

In the External component, an individual’s time series of momentary affective scores would be compared to trait measures [

59]. For instance, we may hypothesize that average longitudinal scores of anxiety and the degree of variation in reported anxiety over time would correlate with Beck Anxiety Inventory scores (BAI; [

60]). We might also hypothesize that a focal construct should change in the context of group differences [

61]. For instance, a researcher might randomize children to either a treatment or experimental condition and provide cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypothesizing that therapy will reduce scores on the SUDS in the treatment group. Similarly, a researcher could use knowledge of the construct to predict how different populations of individuals (OCD vs. non-OCD) might rate the SUDS in the presence of certain stimuli.

However, because the SUDS’s focal construct is not theoretically or empirically defined in the Substantive Stage—leaving its evidence from the Structural Stage undetermined—evidence from the External Stage is difficult to interpret. Without this theoretical and empirical knowledge, one cannot know, for example, how to make sense of the relationships in Kim et al. [

29], who found discriminant validity on the grounds of a non-significant correlation between the SUDS and Trait Anxiety Scale, and then found convergent validity when the SUDS correlated with the BDI. More broadly, without a clear understanding of what the SUDS measures, clinicians cannot confidently use it to predict treatment response, differentiate patient groups, or meaningfully relate subjective distress to other clinical outcomes. For this reason,

Figure 1 suggests that conceptual work be completed in earlier stages in the Strong Program.

Discussion

Since its development, the SUDS has been a cornerstone of research and clinical practice, providing a quick and convenient method of measuring subjective anxiety and distress [

62]. To evaluate the utility of the SUDS as a measure of distress, we investigated its development and applied the Strong Program of Construct Validation, a framework that outlines three cumulative and recursive steps for establishing evidence of construct validity: Substantive, Structural, and External.

Consider a clinical scenario: A patient with OCD undergoing ERP for contamination fears consistently reports a SUDS of 80/100 during exposures involving touching a contaminated object. The clinician, following standard practice, waits for the SUDS to decrease by 50% before ending the exposure, but the patient's rating remains high. Based solely on the SUDS, the clinician might conclude the exposure is ineffective or too difficult. However, upon further questioning prompted by the lack of observable avoidance reduction, the patient reveals the high rating reflects intense

frustration ("I

should be over this!") and

hopelessness ("This is never going to work"), rather than acute anxiety about contamination itself. The SUDS score, lacking clear construct definition (Substantive failure), provided misleading information. Relying on it obscured other clinically relevant affective states and potentially stalled effective treatment progression, underscoring the critical importance of precise differential assessment when interpreting subjective reports in clinical practice [

63].

With an understanding of where the SUDS stands in terms of the Strong Program, its place in modern assessment, as well as how to improve it, becomes clearer. The SUDS struggled to recover from the limitations in its development. For example, Wolpe and Lazarus [

1] approached depression and anxiety from a combined theoretical framework in their formulation of the SUDS. They asserted that “most neurotic depression is the product of severe anxiety arousal” (p. 28), potentially illuminating why the SUDS measures so many constructs. At the same time, little was known about how to measure constructs adequately over longitudinal periods [

64]. Nevertheless, the process of validation is ongoing [

54], and the SUDS should still meet modern measurement standards for clinical and research decisions.

Clinical Implications

Although the practical appeal of the SUDS in demanding clinical settings—offering a seemingly rapid, quantifiable snapshot of patient distress—is undeniable, the significant psychometric limitations regarding its construct validity necessitate considerable caution from clinicians relying on it. Instead of accepting the SUDS score at face value, it is advisable to supplement it with other data sources. Clinicians should integrate direct behavioral observations, such as latency to engage in exposure, task duration, avoidance attempts, or non-verbal signs of distress, alongside the SUDS rating. Crucially, employing qualitative inquiry can contextualize the number; asking clarifying questions like, “What specific feelings or thoughts are contributing to that rating right now?” may reveal whether the score reflects the targeted anxiety, or perhaps frustration, hopelessness, or physical discomfort, thus preventing potential misinterpretations.

Furthermore, clinicians could attempt to improve specificity by explicitly defining the construct during administration (e.g., 'Rate your

fear of contamination from 0-100 right now') rather than using ambiguous terms like “distress” or “disturbance.” While validated single-item measures for specific momentary affective states are being developed [

51], their psychometric robustness for guiding real-time clinical decisions within therapy sessions requires further dedicated research. For evaluating change across sessions or treatment phases, clinicians should continue to prioritize validated multi-item questionnaires designed to assess specific, relevant constructs beyond momentary distress, such as quality of life or symptom severity [

65]. The overarching goal must be to base clinical judgments and interventions on measures with demonstrated reliability and validity for the specific inferences being made, a standard the SUDS, in its current form, struggles to meet.

Improving the SUDS

While this evaluation highlights significant concerns regarding the SUDS's psychometric soundness, it also underscores the genuine need clinicians have for brief, real-time measures of subjective distress during therapeutic interventions like exposure therapy. To bridge this gap and provide clinicians with more trustworthy tools, a dedicated research roadmap is necessary. Firstly, foundational work must revisit the Substantive Component by rigorously defining the specific construct(s) intended for measurement. Rather than relying on the ambiguous umbrella term 'distress' or 'disturbance,' research employing qualitative methods, such as interviewing patients and clinicians about their moment-to-moment experiences during therapy, could identify and operationalize the most salient affective states (e.g., fear intensity, anxiety, disgust, hopelessness) relevant to specific therapeutic contexts. This clarification is a prerequisite for developing or refining any measurement tool [

66].

After building a stronger theoretical base, the measurement properties of the SUDS scale warrant empirical scrutiny. How do patients interpret the 0 - 100 range and the provided anchors (

Table 1)? Does the scale function consistently across different individuals and contexts? Cognitive interviewing studies exploring patients' thought processes as they generate a SUDS rating, or potentially advanced psychometric analyses like item response theory, could shed light on whether the scale yields meaningful quantitative information [

67,

68,

69]. Furthermore, future validation efforts must move beyond simple atheoretical correlations. Employing intensive longitudinal designs, such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA) within or across sessions, would allow researchers to examine the SUDS's sensitivity to change and its relationship with specific therapeutic events and validated measures of distinct emotional states over time. Utilizing a multitrait-multimethod approach within these studies would be crucial for systematically establishing the convergent and discriminant validity that has thus far been lacking

EMA research has already been underway for negative affect that falls under the umbrella of distress using the Strong Program of Construct Validation [

51]. For example, with specific reports of affective experience, Cloos and colleagues [

51] considered momentary affect as individual affective experiences on a dimensional spectrum, ranging from positive affect to negative affect. This underscores that distress is broad, and that measures of negative affect cannot be created on the spot. Thus, we recommend that clinicians and researchers instead operationalize the construct in which they are interested—anxiety? fear? hopelessness?—and select a validated measure for research and clinical care. Another recommendation is to quantify construct validity through meta-analysis [

70]. In attempting to validate a construct, one attempts to include a measure within a nomological network in which it relates to other variables [

25]. A meta-analysis can put one’s hypotheses about the SUDS to the test.

Conclusion

This manuscript has critical implications for researchers and clinicians about a distress scale that has been used for decades. Distress is a uniquely subjective negative affective experience, constantly fluctuating, and influenced by internal and external variables [

71]. As the subjective nature of affect remains pertinent [

72], it requires varied and modern measurement techniques (e.g., questionnaires, interviews) with an overall sensitivity to discriminant and incremental validity [

73]. Modern psychometric methods can supplement such approaches, providing new ways for researchers and clinicians to measure distress that may be applied to the SUDS. By incorporating longitudinal measures of negative affect or using meta-analyses with careful consideration of theory we can more accurately measure and interpret a rating of distress.

Given the significant unanswered questions about what SUDS measures and the potential for misinterpretation, we urge clinicians and researchers to be highly cautious and critical when employing it. While its simplicity is appealing, relying on SUDS scores without acknowledging their profound psychometric limitations may compromise clinical decision-making. However, developing and validating brief, reliable, and theoretically grounded measures of subjective state distress suitable for the dynamic context of therapy sessions remains an important and attainable goal to better support evidence-based clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z.; methodology, B.Z., E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.; writing—review and editing, B.Z.; visualization, E.M.; supervision, B.Z.; project administration, B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

For the past three years, BZ has consulted with Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and received royalties from Oxford University Press; these relationships are not related to the work described here.

References

- Wolpe, J.; Lazarus, A.A. Behavior Therapy Techniques: A Guide to the Treatment of Neuroses.; Pergamon Press, 1966;

- Wolpe, J.; Wolpe, D. Our Useless Fears; Houghton Mifflin, 1981;

- Shapira, S.; Yeshua-Katz, D.; Sarid, O. Effect of Distinct Psychological Interventions on Changes in Self-Reported Distress, Depression and Loneliness among Older Adults during Covid-19. World journal of psychiatry 2022, 12, 970.

- Miegel, F.; Bücker, L.; Kühn, S.; Mostajeran, F.; Moritz, S.; Baumeister, A.; Lohse, L.; Blömer, J.; Grzella, K.; Jelinek, L. Exposure and Response Prevention in Virtual Reality for Patients with Contamination-Related Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: A Case Series. Psychiatric Quarterly 2022, 93, 861–882.

- Wolpe, J. The Systematic Desensitization Treatment of Neuroses. 1961, 132, 189–203.

-

The Practice of Behavior Therapy; Wolpe, J., Ed.; 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: Elmsford, NY, 1969;

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Deacon, B.J.; Whiteside, S.P. Exposure Therapy for Anxiety: Principles and Practice; Guilford Publications, 2019;

- Foa, E.B.; Chambless, D.L. Habituation of Subjective Anxiety during Flooding in Imagery. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1978, 16, 391–399.

- Sherman, T.M.; Cormier, W.H. An Investigation of the Influence of Student Behavior on Teacher Behavior. J Appl Behav Anal 1974, 7, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Wolpe, J.; Flood, J. The Effect of Relaxation on the Galvanic Skin Response to Repeated Phobic Stimuli in Ascending Order. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 1970, 1, 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, C.L.; O’Neil, K.A.; Crawley, S.A.; Beidas, R.S.; Coles, M.; Kendall, P.C. Patterns and Predictors of Subjective Units of Distress in Anxious Youth. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy 2010, 38, 497–504.

- Elsner, B.; Jacobi, T.; Kischkel, E.; Schulze, D.; Reuter, B. Mechanisms of Exposure and Response Prevention in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Effects of Habituation and Expectancy Violation on Short-Term Outcome in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 66. [CrossRef]

- Levy, H.C.; Radomsky, A.S. Safety Behaviour Enhances the Acceptability of Exposure. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2014, 43, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.L.; Radomsky, A.S. An Experimental Investigation of Responsibility and Reassurance: Relationships with Compulsive Checking. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy 2006, 2, 174–191. [CrossRef]

- Zaboski, B.A.; Romaker, E.K. Using Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Exposure for Anxious Students with Classroom Accommodations. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 2023, 37, 209–226. [CrossRef]

- Zaboski, B.A. Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders in Schools: Getting Started. Contemporary School Psychology 2020, 1–6.

- Milgram, L.; Sheehan, K.; Cain, G.; Carper, M.M.; O’Connor, E.E.; Freeman, J.B.; Garcia, A.; Case, B.; Benito, K. Comparison of Patient-Reported Distress during Harm Avoidance and Incompleteness Exposure Tasks for Youth with OCD. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders 2022, 35, 100760.

- Reid, J.E.; Laws, K.R.; Drummond, L.; Vismara, M.; Grancini, B.; Mpavaenda, D.; Fineberg, N.A. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy with Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2021, 106, 152223. [CrossRef]

- Van Noppen, B.; Sassano-Higgins, S.; Appasani, R.; Sapp, F. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: 2021 Update. Focus 2020, 19, 430–443.

- Jacoby, R.J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Blakey, S.M.; Reuman, L. Is the Hierarchy Necessary? Gradual versus Variable Exposure Intensity in the Treatment of Unacceptable Obsessional Thoughts. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 2019, 64, 54–63.

- Kendall, P.C.; Robin, J.A.; Hedtke, K.A.; Suveg, C.; Flannery-Schroeder, E.; Gosch, E. Considering CBT with Anxious Youth? Think Exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2005, 12, 136–148. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, C.; Doebler, P.; Ehring, T.; Vossbeck-Elsebusch, A.N. Emotional Processing Theory Put to Test: A Meta-Analysis on the Association between Process and Outcome Measures in Exposure Therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2017, 24, 697–711.

- Prenoveau, J.M.; Craske, M.G.; Liao, B.; Ornitz, E.M. Human Fear Conditioning and Extinction: Timing Is Everything…or Is It? Biological Psychology 2013, 92, 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Messick, S. Validity of Psychological Assessment: Validation of Inferences from Persons’ Responses and Performances as Scientific Inquiry into Score Meaning. American psychologist 1995, 50, 741.

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct Validity in Psychological Tests. Psychological bulletin 1955, 52, 281–302. [CrossRef]

- Benson, J. Developing a Strong Program of Construct Validation: A Test Anxiety Example. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 2005, 17, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Messick, S. Validity. In Educational measurement; Linn, R.L., Ed.; Macmillan, 1989; pp. 13–103.

- Thyer, B.A.; Papsdorf, J.D.; Davis, R.; Vallecorsa, S. Autonomic Correlates of the Subjective Anxiety Scale. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 1984, 15, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Bae, H.; Park, Y.C. Validity of the Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale in EMDR. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 2008, 2, 57–62.

- Guy, W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology.; US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1976;

- Derogatis, L.R.; Rickels, K.; Rock, A.F. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A Step in the Validation of a New Self-Report Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1976, 128, 280–289.

- Weiss, D.S. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD; Springer, 2007; pp. 219–238.

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA Statement on P-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose 2016.

- Kranzler, J.H.; Floyd, R.G.; Benson, N.; Zaboski, B.; Thibodaux, L. Cross-Battery Assessment Pattern of Strengths and Weaknesses Approach to the Identification of Specific Learning Disorders: Evidence-Based Practice or Pseudoscience? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 2016, 4, 146–157. [CrossRef]

- Lachin, J.M. Fallacies of Last Observation Carried Forward Analyses. Clinical Trials 2016, 13, 161–168. [CrossRef]

- Hamer, R.M.; Simpson, P.M. Last Observation Carried Forward versus Mixed Models in the Analysis of Psychiatric Clinical Trials 2009.

- Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J. Challenges in Design and Interpretation of Chronic Pain Trials. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2013, 111, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, B.A. Validity of Global Physical and Emotional SUDS. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2012, 37, 31–34. [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.L. The MMPI-2: An Interpretive Manual; Allyn & Bacon, 2000;

- Endicott, J.; Spitzer, R.L.; Fleiss, J.L.; Cohen, J. The Global Assessment Scale: A Procedure for Measuring Overall Severity of Psychiatric Disturbance. Archives of general psychiatry 1976, 33, 766–771.

- Pittig, A.; Arch, J.J.; Lam, C.W.; Craske, M.G. Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability in Panic, Social Anxiety, Obsessive–Compulsive, and Generalized Anxiety Disorders at Baseline and in Response to Relaxation and Hyperventilation. International journal of psychophysiology 2013, 87, 19–27.

- Reid, A.M.; Garner, L.E.; Van Kirk, N.; Gironda, C.; Krompinger, J.W.; Brennan, B.P.; Mathes, B.M.; Monaghan, S.C.; Tifft, E.D.; André, M.-C.; et al. How Willing Are You? Willingness as a Predictor of Change during Treatment of Adults with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Depression and Anxiety 2017, 34, 1057–1064. [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.A.; Chiappetta, L.; Bridge, J.; Monga, S.; Baugher, M. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A Replication Study. Journal of the American academy of child & adolescent psychiatry 1999, 38, 1230–1236.

- Goodman, R. Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345.

- Simons, J.S.; Gaher, R.M. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. Motivation and emotion 2005, 29, 83–102.

- Tonarely, N.A.; Hirlemann, A.; Shaw, A.M.; LoCurto, J.; Souer, H.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Jensen-Doss, A.; Ehrenreich-May, J. Validation and Clinical Correlates of the Behavioral Indicator of Resiliency to Distress Task (BIRD) in a University- and Community-Based Sample of Youth with Emotional Disorders. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2020, 42, 787–798. [CrossRef]

- Sripada, R.K.; Rauch, S.A. Between-Session and within-Session Habituation in Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Hierarchical Linear Modeling Approach. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2015, 30, 81–87.

- Kircanski, K.; Wu, M.; Piacentini, J. Reduction of Subjective Distress in CBT for Childhood OCD: Nature of Change, Predictors, and Relation to Treatment Outcome. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2014, 28, 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Cronbach Construct Validation after Thirty Years. In Intelligence: Measurement, theory, and public policy: Proceedings of a symposium in honor of Lloyd G. Humphreys; Linn, R., Ed.; University of Chicago Press, 1989; pp. 147–167.

- Loevinger, J. Objective Tests as Instruments of Psychological Theory. Psychological reports 1957, 3, 635–694.

- Cloos, L.; Ceulemans, E.; Kuppens, P. Development, Validation, and Comparison of Self-Report Measures for Positive and Negative Affect in Intensive Longitudinal Research. Psychological Assessment 2022.

- Watkins, M.W. A Step-by-Step Guide to Exploratory Factor Analysis with R and RStudio; Routledge, 2020;

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory; 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, 1978;

- Association, A.E.R.; Association, A.P.; Education, N.C. on M. in Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, 2014; ISBN 978-0-935302-35-6.

- Takac, M.; Collett, J.; Blom, K.J.; Conduit, R.; Rehm, I.; Foe, A.D. Public Speaking Anxiety Decreases within Repeated Virtual Reality Training Sessions. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216288. [CrossRef]

- Essayli, J.H.; Forrest, L.N.; Zickgraf, H.F.; Stefano, E.C.; Keller, K.L.; Lane-Loney, S.E. The Impact of Between-session Habituation, Within-session Habituation, and Weight Gain on Response to Food Exposure for Adolescents with Eating Disorders. Intl J Eating Disorders 2023, 56, 637–645. [CrossRef]

- Brose, A.; Schmiedek, F.; Gerstorf, D.; Voelkle, M.C. The Measurement of Within-Person Affect Variation. Emotion 2020, 20, 677.

-

Methods, Theories, and Empirical Applications in the Social Sciences; Salzborn, S., Davidov, E., Reinecke, J., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, 2012; ISBN 978-3-531-17130-2.

- Trull, T.J.; Ebner-Priemer, U. Ambulatory Assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 151–176. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An Inventory for Measuring Clinical Anxiety: Psychometric Properties. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1988, 56, 893.

- Furr, R.M. Psychometrics: An Introduction; SAGE publications, 2021;

-

Phobias: The Psychology of Irrational Fear; Milosevic, I., McCabe, R.E., Eds.; ABC-CLIO, 2015;

- Mattera, E.F.; Ching, T.H.; Zaboski, B.A.; Kichuk, S.A. Suicidal Obsessions or Suicidal Ideation? A Case Report and Practical Guide for Differential Assessment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2022.

- Flake, J.K.; Fried, E.I. Measurement Schmeasurement: Questionable Measurement Practices and How to Avoid Them. 2020, 10.

- Molinari, A.D.; Andrews, J.L.; Zaboski, B.A.; Kay, B.; Hamblin, R.; Gilbert, A.; Ramos, A.; Riemann, B.C.; Eken, S.; Nadeau, J.M. Quality of Life and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents in Residential Treatment Facilities. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 2019, 36, 220–234. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; sage publications, 2004;

- Liu, W.; Dindo, L.; Hadlandsmyth, K.; Unick, G.J.; Zimmerman, M.B.; St. Marie, B.; Embree, J.; Tripp-Reimer, T.; Rakel, B. Item Response Theory Analysis: PROMIS® Anxiety Form and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale. West J Nurs Res 2022, 44, 765–772. [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Reise, S.P. Using Item Response Theory to Identify Responders to Treatment: Examples with the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) Physical Function Scale and Emotional Distress Composite. Psychometrika 2021, 86, 781–792.

- Westen, D.; Rosenthal, R. Quantifying Construct Validity: Two Simple Measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 84, 608–618. [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Verduyn, P. Emotion Dynamics. Current Opinion In Psychology, 17, 22–26 2017.

- Gray, E.K.; Watson, D. Assessing Positive and Negative Affect via Self-Report. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment 2007, 171–183.

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychological assessment 2019, 31, 1412.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).