Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Test Rice

2.2. Recruitment of Subjects

- Healthy group: Participants aged ≥ 21 years with a body mass index (BMI) within the normal range (18.5–24.9 kg/m²) were included. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, chronic disorders, use of hypoglycemic agents, smoking, and participation in high-intensity athletic activities.

- T2DM group: Participants aged ≥ 21 years with stable renal function for at least six months and a stable dose of oral hypoglycemic agents for at least three months were included. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, end-stage diabetes complications, multiple insulin dosages, recent T2DM diagnosis, and the use of GLP-1-based oral hypoglycemic medications (specifically DPP-IV inhibitors, such as sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, and others, which prolong endogenous GLP-1 activity by preventing its degradation).

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Sample Analysis

- Insulin analysis: Performed using the Diametra Insulin ELISA kit (DCM076-8 – Ed 09/2018, REF DKO076).

- GLP-1 analysis: Conducted in duplicate using the GLP-1 Total ELISA kit (96-well plate assay, Cat.# EZGLP1T-36K, EZGLP1T-36BK).

- Plasma glucose: Assessed using the Beckman Coulter Oxygen Electrode, a SYNCHRON system in the biochemical analytical lab of the Kuwait Ministry of Health. A certified technician, blinded to participant identities, conducted the analysis.

-

Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and β-cell function (HOMA-B) were calculated using the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA):

-

Matsuda Index (MI), which assesses insulin sensitivity during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), was calculated using glucose and insulin data at 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes:

- o

- MI = 10,000 / √(fasting glucose × fasting insulin × mean glucose × mean insulin) [12].

-

The Disposition Index (DI), which evaluates β-cell compensation for insulin resistance, was computed as:

- o

- DI = [(postprandial insulin - basal insulin) / (postprandial glucose - basal glucose) × 18] × MI [10].

-

Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as:

- o

- BMI = weight (kg) / height (m²)

- HbA1c was measured using a Tosoh Automated Glycohemoglobin Analyzer HLC-723G8.

- Incremental areas under the curve (IAUC) for glucose, insulin, and GLP-1 were calculated using the trapezoidal rule, excluding areas below baseline [25].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

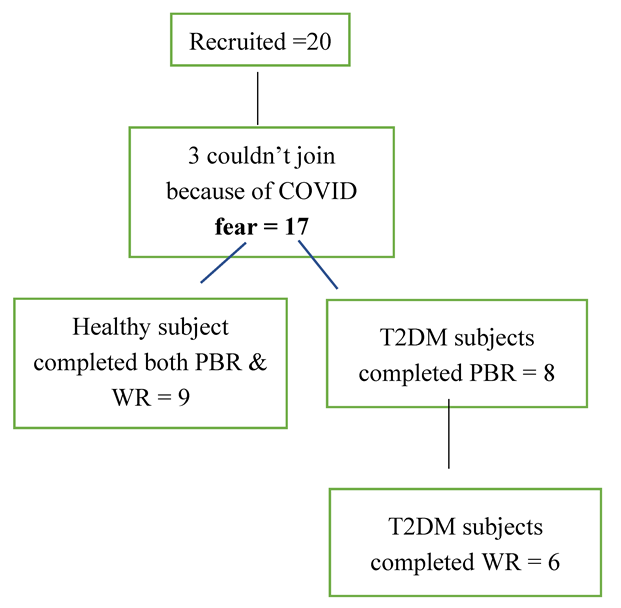

3.1. Subjects

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

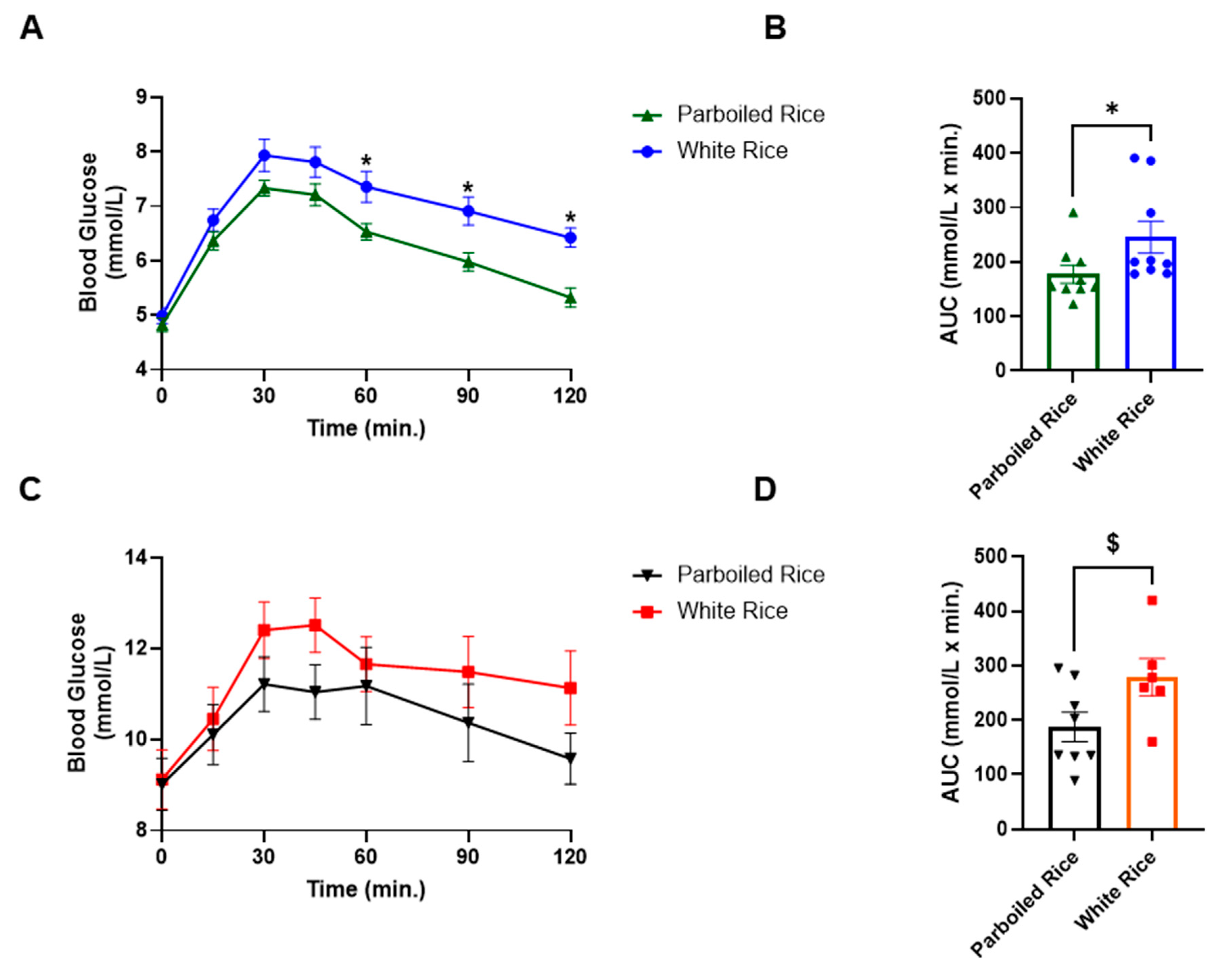

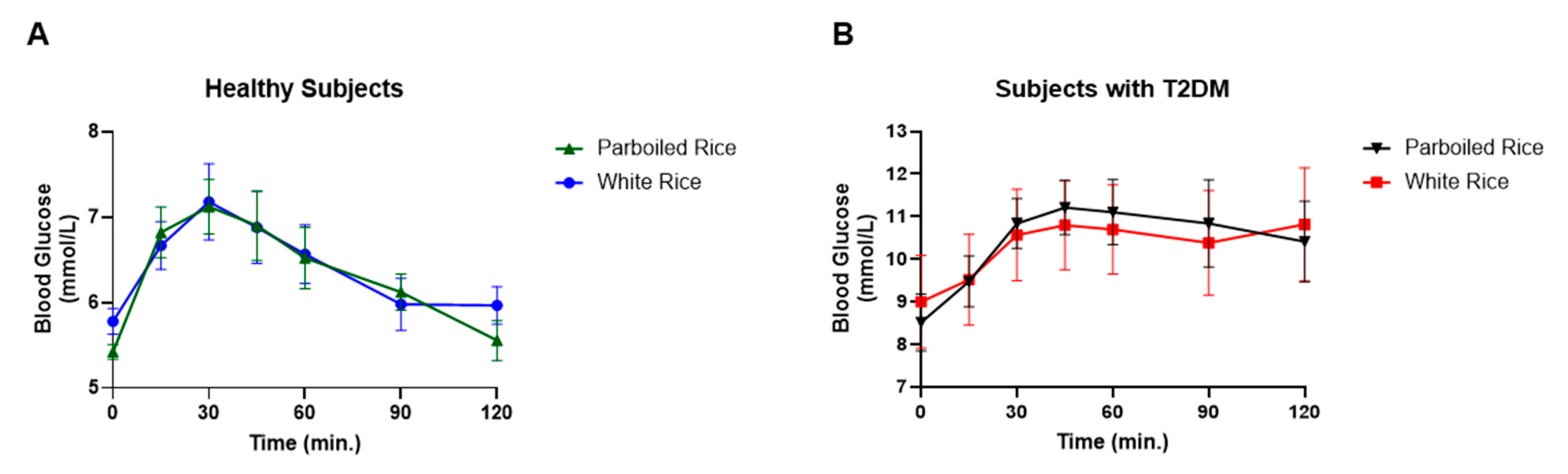

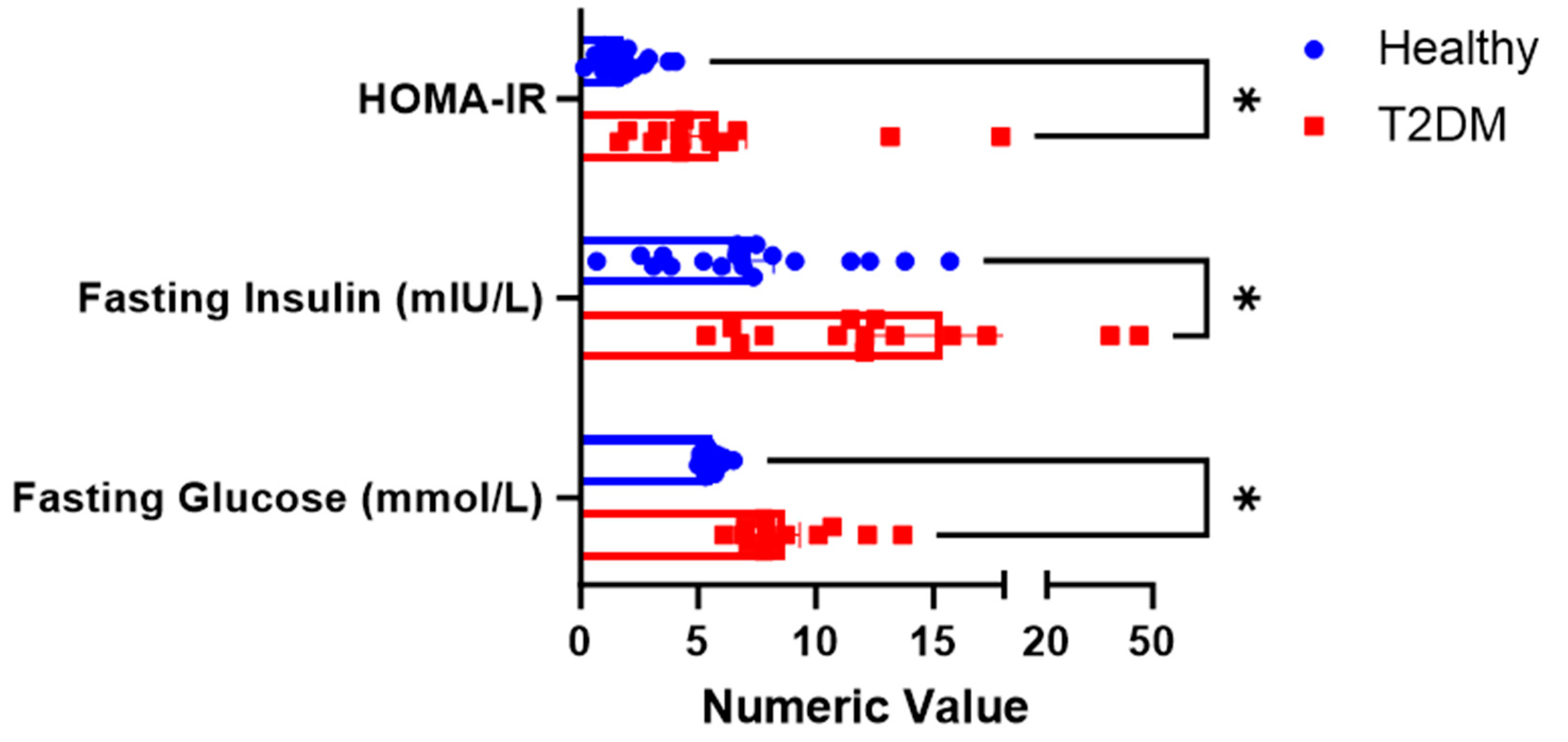

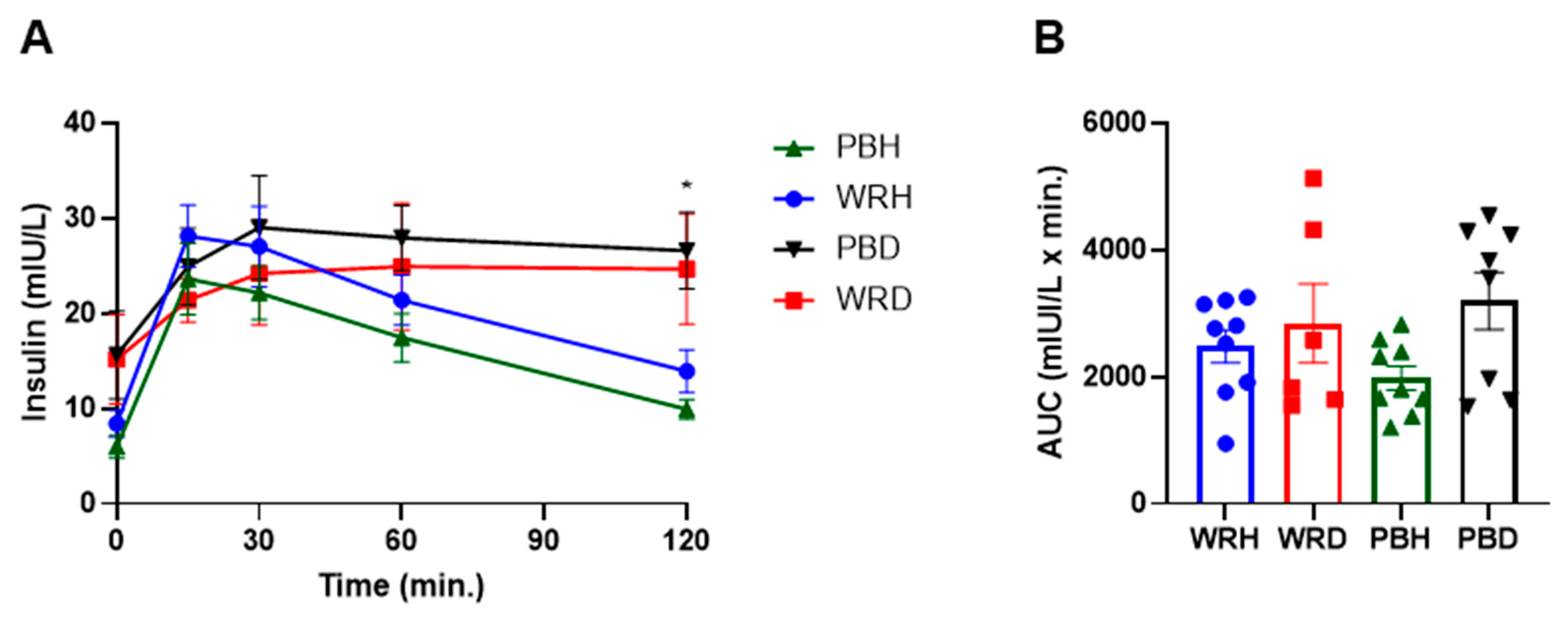

3.3. Biochemical Parameters Between the Two Groups after Consumption of the Test Rice

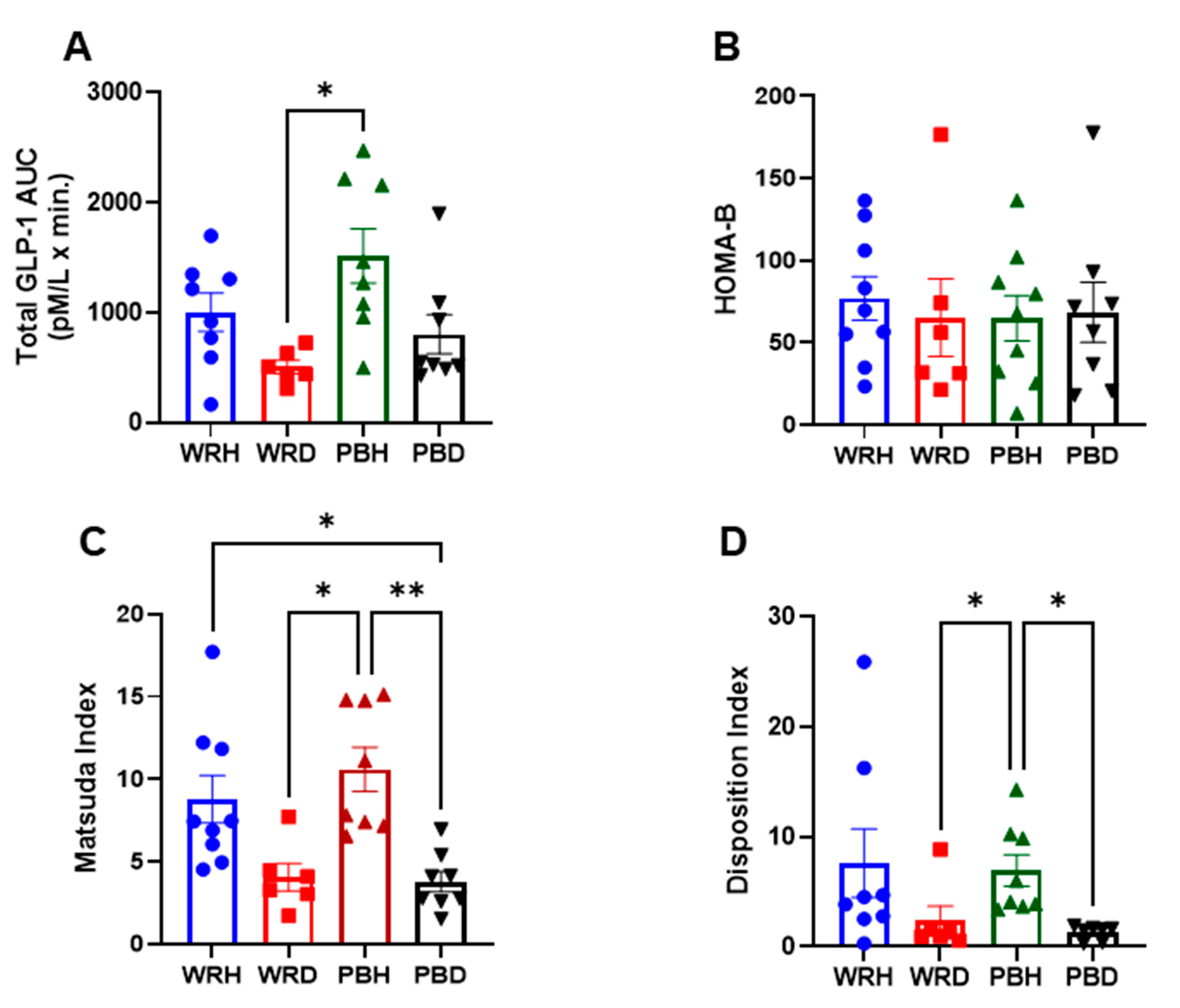

4. GLP-1 Responses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

7. Strengths & Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guariguata, L.; Whiting, D.; Hambleton, I.; Beagley, J.; Linnenkamp, U.; Shaw, J. Global Estimates of Diabetes Prevalence for 2013 and Projections for 2035. Diabet. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 103, 137–149.

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Available online: http://www.idf.org (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Ceriello, A.; Colagiuri, S. International Diabetes Federation Guideline for Management of Postmeal Glucose: A Review of Recommendations. Diabetes Med. 2008, 25, 1151–1156. [CrossRef]

- Litwak L, Goh SY, Hussein Z, Malek R, Prusty V, Khamseh ME. Prevalence of diabetes complications in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with baseline characteristics in the multinational A1chieve study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2013;5:57.

- Cantley, J.; Ashcroft, F.M. Q&A: Insulin Secretion and Type 2 Diabetes: Why Do β-Cells Fail? BMC Biol. 2015, 13, 33.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diabetes Symptoms. 15 August 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419.

- Furugen, M.; Saitoh, S.; Ohnishi, H.; Akasaka, H.; Mitsumata, M.; Chiba, M.; Miura, T. Matsuda–DeFronzo Insulin Sensitivity Index is a Better Predictor than HOMA-IR of Hypertension in Japanese: The Tanno–Sobetsu Study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2012, 26, 325–333.

- Basila, A.M.; Hernández, J.M.; Alarcón, M.L. Diagnostic Methods of Insulin Resistance in a Pediatric Population. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant Mex. 2011, 68, 367–373.

- Richard, N.; Bergman, R.N.; Marilyn, A.K.; Gregg, V.C. Accurate assessment of β-cell function: The hyperbolic correction. Diabetes 2002, 51 (Suppl 1), S212–S220. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Wagenknecht, L.E.; Rewers, M.; Karter, A.J.; Bergman, R.N.; Hanley, A.J.; Haffner, S.M. Disposition index, glucose effectiveness, and conversion to type 2 diabetes: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Diabetes Care 2011, 33, 2098–2103.

- Matsuda, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: Comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1462–1470.

- Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Yabe, D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: Similarities and differences. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010, 1, 8–23.

- Nauck, M.A., Müller, T.D. Incretin hormones and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2023, 66, 1780–1795. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabah, S.; Alasfar, F.; Al-Khaledi, G.; et al. Incretin Response to a Standard Test Meal in a Rat Model of Sleeve Gastrectomy with Diet-Induced Obesity. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Egan, J.M. The role of incretins in glucose homeostasis and diabetes treatment. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008, 60, 470–512. [CrossRef]

- Koopman, A.D.; Rutters, F.; Rauh, S.P.; Nijpels, G.; Holst, J.J.; Beulens, J.W.; et al. Incretin responses to oral glucose and mixed meal tests and changes in fasting glucose levels during 7 years of follow-up: The Hoorn Meal Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191114.

- Hu, F.B. Diet and Risk of Type II Diabetes: The Role of Types of Fat and Carbohydrate. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 805–817.

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Kato, M.; Inoue, M.; et al. Rice Intake and Type 2 Diabetes in Japanese Men and Women: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1348–1354.

- Oli, P.; Ward, R.; Adhikari, B.; Torley, P. Parboiled Rice: Understanding from a Materials Science Approach. J. Food Eng. 2014, 124, 173–183.

- Mohan, V.; Spiegelman, D.; Sudha, V.; Gayathri, R.; Hong, B.; Praseena, K.; et al. Effect of Brown Rice, White Rice, and Brown Rice with Legumes on Blood Glucose and Insulin Responses in Overweight Asian Indians: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2014, 16, 317–325.

- Hamad, S.; Zafar, T.; Sidhu, J. Parboiled Rice Metabolism Differs in Healthy and Diabetic Individuals with Similar Improvement in Glycemic Response. Nutr. 2018, 47, 43–49.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In Vitro Diagnostic Test Systems—Requirements for Blood-Glucose Monitoring Systems for Self-Testing in Managing Diabetes Mellitus; ISO 15197:2013; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Kameyama, N.; Maruyama, C.; Matsui, S.; Araki, R.; Yamada, Y.; Maruyama, T. Effects of Consumption of Main and Side Dishes with White Rice on Postprandial Glucose, Insulin, Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide, and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Responses in Healthy Japanese Men. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1632–1640. [CrossRef]

- Brouns, F.; Bjorck, I. Glycemic Index Methodology. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 145–171.

- Gutch, M.; Kumar, S.; Razi, S.; Gupta, K.; Gupta, A. Assessment of Insulin Sensitivity/Resistance. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 19, 1. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.W.; Venn, B.; Lu, J.; Monro, J.; Rush, E. Effect of Cold Storage and Reheating of Parboiled Rice on Postprandial Glycaemic Response, Satiety, Palatability, and Chewed Particle Size Distribution. Nutrients 2017, 9, 475.

- Rasaiah, B. Self-Monitoring of the Blood Glucose Level: Potential Sources of Inaccuracy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1985, 132, 1357–1361.

- Patel, N.; Patel, K. A Comparative Study of Venous and Capillary Blood Glucose Levels by Different Methods. GCSMC J. Med. Sci. 2015, IV, 1.

- Adnan, M.; Imamb, F.; Shabbira, I.; Alia, Z.; Rahata, T. Correlation Between Capillary and Venous Blood Glucose Levels in Diabetic Patients. Asian Biomed. 2015, 9, 55–59. [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, R.; Singh, R.P.; Chauhan, K. A Comparative Study of Venous and Capillary Blood Glucose in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2020, 11, 7, 673-677.

- Andelin, M.; Kropff, J.; Matuleviciene, V.; Joseph, J.I.; Attvall, S.; Theodorsson, E.; Hirsch, I.B.; Imberg, H.; Dahlqvist, S.; Klonoff, D.; et al. Assessing the Accuracy of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Calibrated With Capillary Values Using Capillary or Venous Glucose Levels as a Reference. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2016, 10, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chang, C.; Lin, J. A Comparison Between Venous and Finger-Prick Blood Sampling on Values of Blood Glucose. IPCBEE 2012, 39, 206–210.

- Longo, Casper, Fauci. Hauser, Jameson, Loscalzo, Harrison principles of Medicine. Diabetes Mellitus. 18th ed. Mcgrow Hill 2011; (2), 2970-71.

- Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO). Carbohydrates in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 66; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1997.

- DeFronzo, R. From the Triumvirate to the Ominous Octet: A New Paradigm for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 2009, 58, 773–795. [CrossRef]

- Melmed, S.; Polonsky, K.S.; Larsen, P.R.; Kronenberg, H.M. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 13th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.A.; Jenkinson, C.P.; Richardson, D.K.; Tripathy, D.; DeFronzo, RA. Insulin Secretion and Action In Subjects with Impaired Fasting Glucose and Impaired Glucose Tolerance: Results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study. Diabetes. 2006, 55(5):1430-5. [CrossRef]

- Gower, B. A., Goss, A. M., Yurchishin, M. L., Deemer, S. E., Sunil, B., & Garvey, W. T. Effects of a Carbohydrate-Restricted Diet on β-Cell Response in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.M.; Levy, J.C.; Matthews, D.R. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–1495. [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88(4):787–835, ix. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Haffner, S.M.; Stančáková, A.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M. Fasting and OGTT-Derived Measures of Insulin Resistance as Compared with the Euglycemic-Hyperinsulinemic Clamp in Nondiabetic Finnish Offspring of Type 2 Diabetic Individuals. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 544–550. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H., Rasmussen, O., Rasmussen, P. et al. Glycaemic index of parboiled rice depends on the severity of processing: study in type 2 diabetic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000, 54, 380–385. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.E.; Cooper, M.E.; Del Prato, S. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Perspectives on the Past, Present, and Future. Lancet 2014, 383, 1068–1083.

- Al-Sabah, S. Molecular Pharmacology of the Incretin Receptors. Med Princ Pract. 2016, 25, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; Homberger, E.; Siegel, E.G.; Allen, R.C.; Eaton, R.P.; Ebert, R.; et al. Incretin Effects of Increasing Glucose Loads in Man Calculated from Venous Insulin and C-Peptide Responses. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986, 63, 492–498.

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Incretin Hormones: Their Role in Health and Disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 5–21.

- Wang, X.L.; Ye, F.; Li, J.; et al. Impaired Secretion of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 During Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 48–53.

- Grespan, E.; Giorgino, T.; Natali, A.; Ferrannini, E.; Mari, A. Different mechanisms of GIP and GLP-1 action explain their different therapeutic efficacy in type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2021,114:154415.

- Watkins, J.D.; Carter, S.; Atkinson, G.; Koumanov, F.; Betts, J.A.; Holst, J.J.;, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in people with versus without type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Metabolism. 2023,1(140): 155375. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Kaneto, H.; Laybutt, D.R.; Duvivier-Kali, V.F.; Trivedi, N.; Suzuma, K.; et al. Downregulation of GLP-1 and GIP receptor expression by hyperglycemia possible contribution to impaired incretin effects in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007, 56(6):1551–8. [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.J. In Vivo Models for Incretin Research: From the Intestine to the Whole Body. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2016, 31, 45–51.

- Movahednasab, M.; Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Khodadad, S. et al. GLP-1-based therapies for type 2 diabetes: from single, dual and triple agonists to endogenous GLP-1 production and L-cell differentiation. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2025, 17, 60. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, T. A. High amylose cornstarch preloads stabilized postprandial blood glucose but failed to reduce appetite or food intake in healthy women. Appetite. 2018, 131 (1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Lu, W., Liang, Y., Wang, L., Jin, N., Zhao, H., Fan, B., & Wang, F. Research Progress on Hypoglycemic Mechanisms of Resistant Starch: A Review. Molecules, 2022, 27(20), 7111. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Hu, X. A More Pronounced Effect of Type III Resistant Starch vs. Type II Resistant Starch on Ameliorating Hyperlipidemia in High Fat Diet-Fed Mice Is Associated with Its Supramolecular Structural Characteristics. Food Funct. 2020, 11:1982–1995. [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.H.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23:1105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, S.; Wu, J.; Luo, L.; Qiao, S.; Li, R.; Xu, W.; Wang, N.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; et al. A Specific Gut Microbiota and Metabolomic Profiles Shifts Related to Antidiabetic Action: The Similar and Complementary Antidiabetic Properties of Type 3 Resistant Starch from Canna Edulis and Metformin. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159:104985. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Córdova, Y.; Ble-Castillo, J.L.; García-Vázquez, C.; Olvera-Hernández, V.; Ramos-García, M.; Navarrete-Cortes, A.; Jiménez-Domínguez, G.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Martínez-López, M.C.; et al. Resistant Starch Consumption Effects on Glycemic Control and Glycemic Variability in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Study. Nutrients. 2021, 13:52. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Martin, R.J.; Tulley, R.T.; et al. Dietary Resistant Starch Upregulates Total GLP-1 and PYY in a Sustained Day-Long Manner through Fermentation in Rodents. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E1160–E1166.

- Yong, W.; Jing, C.; Ying-Han, S.; et al. Effects of Resistant Starch on Glucose, Insulin, Insulin Resistance, and Lipid Parameters in Overweight or Obese Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Diabetes 2019, 9, 1–9.

- Bindels, L. B.; Segura Munoz, R. R.; Gomes-Neto, J. C.; Mutemberezi, V.; Martínez, I.; Salazar, N.; Cody, E. A.; Quintero-Villegas, M. I.; Kittana, H.; Schmaltz, R. J.; Muccioli, G. G.; Walter, J.; & Ramer-Tait, A. E. Resistant starch can improve insulin sensitivity independently of the gut microbiota. Microbiome, 2017, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

- Behall, K.M.; Scholfield, D.; Yuhaniak, I.; Canary, J. Diets containing high amylose vs amylopectin starch: Effects on metabolic variables in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1989, 49,337–44.

- Behall, K.; Hallfrisch, J. Plasma glucose and insulin reduction after consumption of breads varying in amylose content. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2002, 56, 913–20.

- Behall, K.M.; Howe, J.C. Effect of long-term consumption of amylose vs amylopectin starch on metabolic variables in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr, 1995, 61,334–40.

- Kendall, C.W.; Esfahani, A.; Sanders, L.M.; Potter, S.M.; Vidgen, E. The Effect of a Pre-Load Meal Containing Resistant Starch on Spontaneous Food Intake and Glucose and Insulin Responses. J. Food Technol. 2010, 8, 67–73.

- Jenkins, D.J.; Vuksan, V.; Kendall, C.W.; Würsch, P.; Jeffcoat, R.; Waring, S.; et al. Physiological Effects of Resistant Starches on Fecal Bulk, Short Chain Fatty Acids, Blood Lipids and Glycemic Index. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1998, 17, 609–616.

- Takahashi, K.; Fujita, H.; Fujita, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Kato, S.; Shimizu, T.; Suganuma, Y.; Sato, T.; Waki, H.; Yamada, Y. A Pilot Study to Assess Glucose, Insulin, and Incretin Responses Following Novel High Resistant Starch Rice Ingestion in Healthy Men. Diabetes Ther. 2022, 13, 1383. [CrossRef]

- Bodinham, C.; Smith, L.; Thomas, E.; Bell, J.; Swann, J.; Costabile, A.; et al. Efficacy of Increased Resistant Starch Consumption in Human Type 2 Diabetes. Endocr. Connect. 2014, 3, 75–84.

- Regmi, P.; van Kempen, T.; Matte, J.J.; Zijlstra, R.T. Starch with High Amylose and Low In Vitro Digestibility Increases Short-Chain Fatty Acid Absorption, Reduces Peak Insulin Secretion, and Modulates Incretin Secretion in Pigs. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 398–405.

- Pugh, J.E.; Cai, M.; Altieri, N.; Frost, G. A Comparison of the Effects of Resistant Starch Types on Glycemic Response in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1118229. [CrossRef]

- Jin, T. The WNT Signalling Pathway and Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1771–1780.

- Muchlisyiyah, J.; Shamsudin, R.; Kadir Basha, R.; Shukri, R.; How, S.; Niranjan, K.; Onwude, D. Parboiled Rice Processing Method, Rice Quality, Health Benefits, Environment, and Future Perspectives: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1390. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2017 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin. Diabetes 2017, 35, 5–26. [CrossRef]

- Vajje, J.; Khan, S.; Kaur, A.; et al. Comparison of the Efficacy of Metformin and Lifestyle Modification for the Primary Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus 2023, 15, e47105. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Diabetic (n = 8) | Healthy (n = 9) |

| Gender Male / Female (n) |

3 / 5 |

4 / 5 |

| Age (years) Mean ± SD | 45.96 ± 11.34 | 32.9 ± 2.64 |

| BMI (kg/m²) Mean ± SD | 31.23 ± 4.50 | 23.54 ± 0.74 |

| Blood Pressure (mm Hg) Mean ± SD Systolic Diastolic |

117.33 ±11.82 79.33 ± 7.07 |

112.5 ± 9.99 80 ± 3.53 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.75 ± 0.67 | 4.96 ± 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).