Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Quantum Computing Fundamentals

2.1. Types of Hardware

2.2. Quantum Error: Error Suppression, Error Mitigation and Error Correction

- Error suppression is a fundamental level of error handling in quantum computing. It involves techniques that use knowledge of undesirable effects to anticipate and avoid potential impacts, often at the hardware level. These methods, which date back decades, typically involve altering or adding control signals to ensure the processor returns the desired result. Error suppression, also known as deterministic or dynamic error suppression, reduces the likelihood of hardware errors during quantum bit manipulation or memory storage. It leverages quantum control techniques to build resilience against errors. For example, quantum logic gates, which are essential for quantum algorithms, can be redefined using machine learning to enhance robustness against errors [12]. Similarly, control operations can protect idle qubits from external interference, akin to a "force field" that deflects noise [13]. Various strategies for error suppression can significantly improve quantum computing performance. Designing new quantum logic gates can make operations up to ten times less likely to suffer errors, thus enhancing algorithmic performance. Research has shown that error suppression can increase the likelihood of achieving correct results by over 1000 times [14]. Error suppression can be integrated into quantum firmware or configured for automated workflows, reducing errors on each run without additional overhead. However, it cannot correct all errors, such as "Energy Relaxation" (T1) errors, which require Quantum Error Correction strategies.

- Error mitigation (EM) is crucial for making near-term quantum computers useful by reducing or eliminating noise through the estimation of expectation values. Each EM method has its own overhead and accuracy level. The most powerful techniques can have exponential overhead, meaning the time to run increases exponentially with the problem size (number of qubits and circuit depth). Users can choose the best technique based on their accuracy needs and acceptable overhead. In quantum computing, estimating calculated parameters, like energy levels of molecules in quantum chemistry, can be affected by errors in both algorithm execution and measurement. Various strategies have been developed to improve results through post-processing, including randomized compiling [15], measurement-error mitigation [16], zero-noise extrapolation [17], and probabilistic error cancellation [18]. These strategies involve running many slightly different versions of a target algorithm and combining the results to "extract the right answer through the errors". Measurement-error mitigation is particularly powerful, using statistical techniques to identify correct calculations despite readout failures. To maximize benefits from EM, an algorithm might need to be run around 100 times with different configurations, which could lead to a significant increase in quantum computing costs.

- Error correction (QEC) aims to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation by building redundancies so that even if some qubits experience errors, the system still returns accurate results [19]. In classical computing, error correction involves encoding information with redundancy to check for errors. Quantum error correction follows the same principle but must account for new types of errors and carefully measure the system to avoid collapsing the quantum state. In QEC, single qubit values (logical qubits) are encoded across multiple physical qubits. Gates are implemented to treat these physical qubits as error-free logical qubits. The QEC algorithm distributes quantum information across supporting qubits, protecting it against local hardware failures. Special measurements on helper qubits indicate failures without disturbing the stored information, allowing corrections to be applied. QEC involves cycles of gates, syndrome measurements, error inference, and corrections, functioning as feedback stabilization. The entire error-correction cycle is designed to tolerate errors at every stage, enabling error-robust quantum processing even with unreliable components. This fault-tolerant architecture enables the construction of large quantum computers with low error rates, but quantum error correction (QEC) requires a significant number of qubits. The greater the noise, the more qubits are needed, and estimates suggest that thousands of physical qubits may be required to encode a single protected logical qubit, which presents a challenge given the limited qubit counts of current systems. The sheer scale of this overhead and the complexity of QEC is why despite many promising results, QEC still needs further refinement to provide efficient operations for useful applications [20]. This may change soon though, following the recent advancements from hardware providers.

3. Classical Machine Learning: Principles and Overview

3.1. Kernel Method

- Linear Kernel — This is just the standard dot product in the original space and doesn’t map the data to a higher dimension.

- Polynomial Kernel — This maps the data into a higher-dimensional space based on polynomial functions.

- Radial Basis Function (RBF) / Gaussian Kernel — This kernel maps the data into an infinite-dimensional space and is often used in SVMs for classification tasks. It is useful for capturing non-linear relationships.

- Sigmoid Kernel — Based on the hyperbolic tangent function, it’s similar to the activation function used in neural networks.

3.2. Random Forest

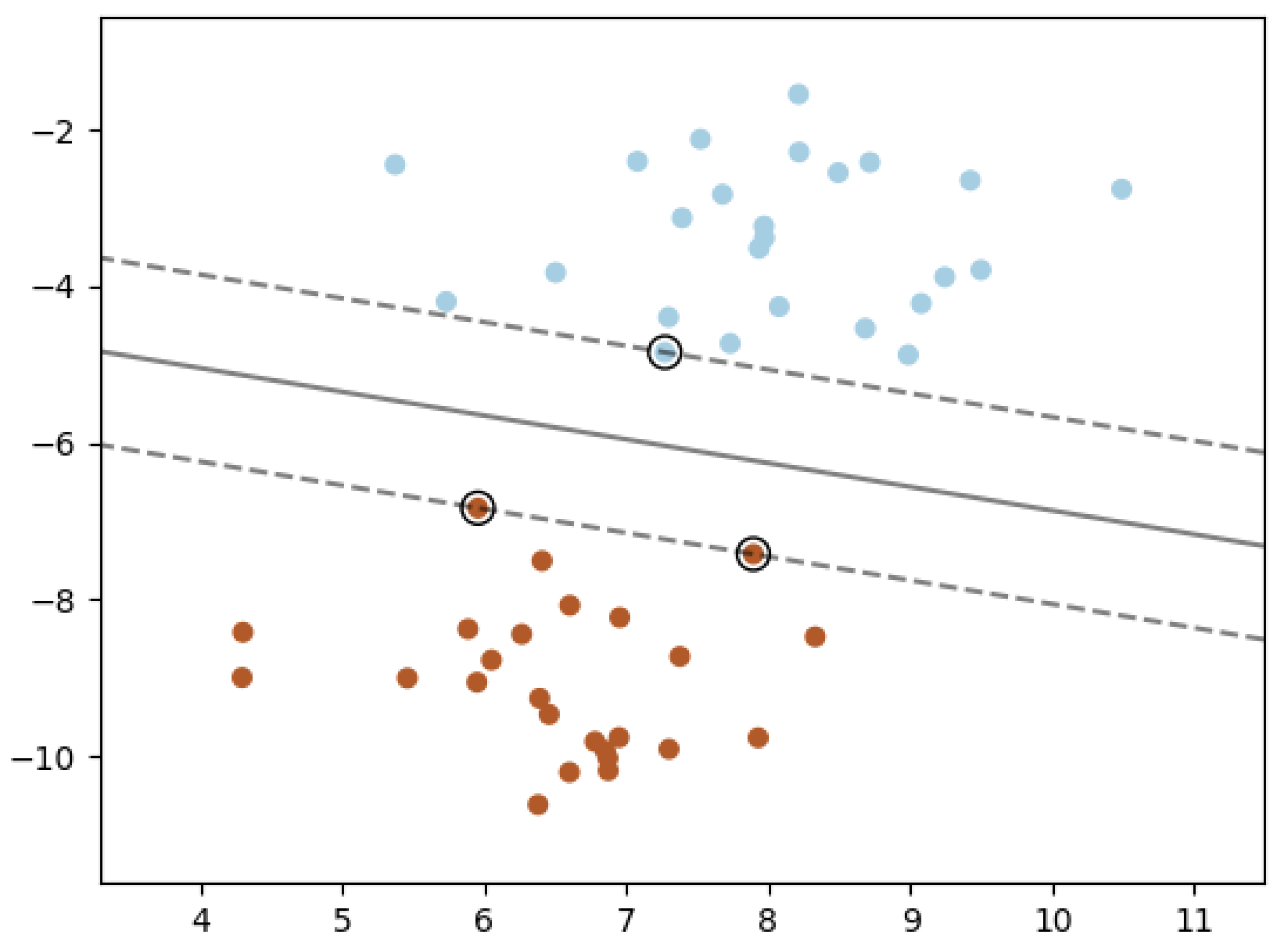

3.3. Support Vector Machine

3.4. Artificial Neural Networks

3.5. Restricted Boltzmann Machine

4. Quantum Machine Learning

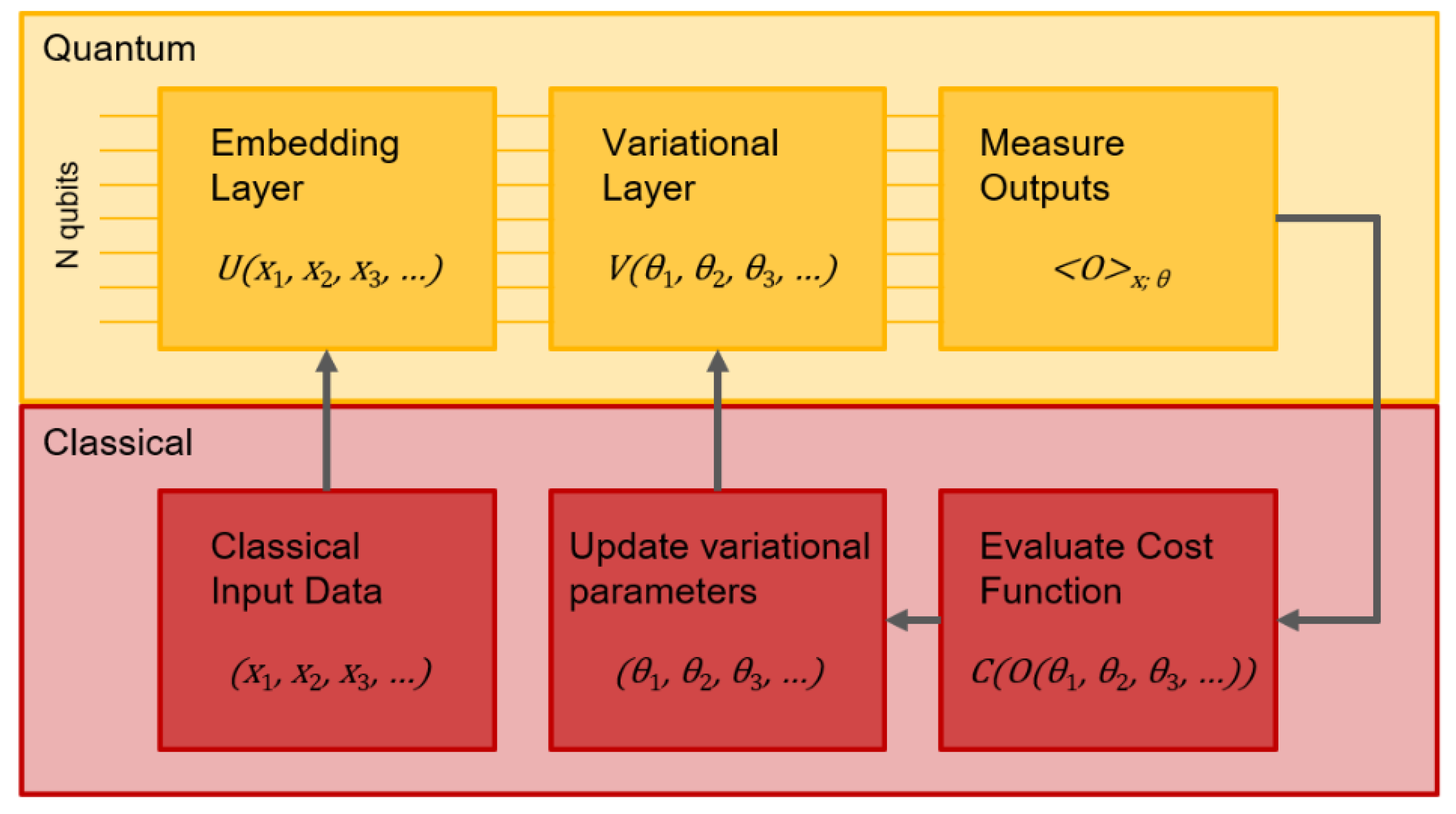

4.1. Quantum Variational Algorithms

4.2. Expressivity-Trainability Trade-Off

4.3. Explicit Quantum Models

4.4. Implicit Quantum Models (Quantum Kernels)

4.5. Quantum Neural Networks

4.6. Quantum Annealing Applied to Machine Learning

5. Case-Based Research in the Energy Sector

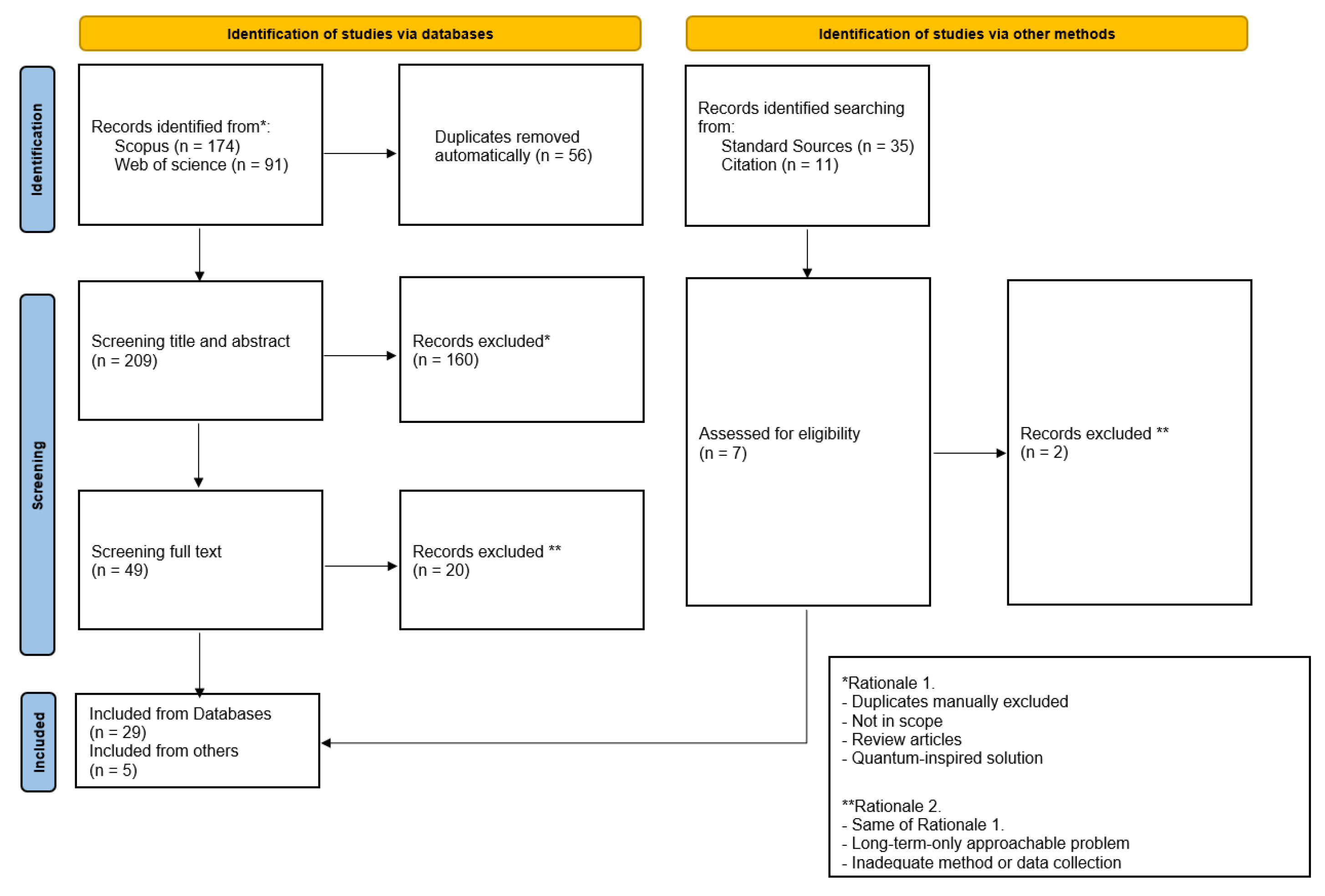

5.1. Rationale

- How can the energy and utilities sector benefit from quantum computing, and which specific ML applications or challenges will QC address in the near- to medium-term future?

- Which use cases of quantum machine learning have the most significant impact on the energy and utilities sector related to their level of readiness?

5.2. Methods and Overview

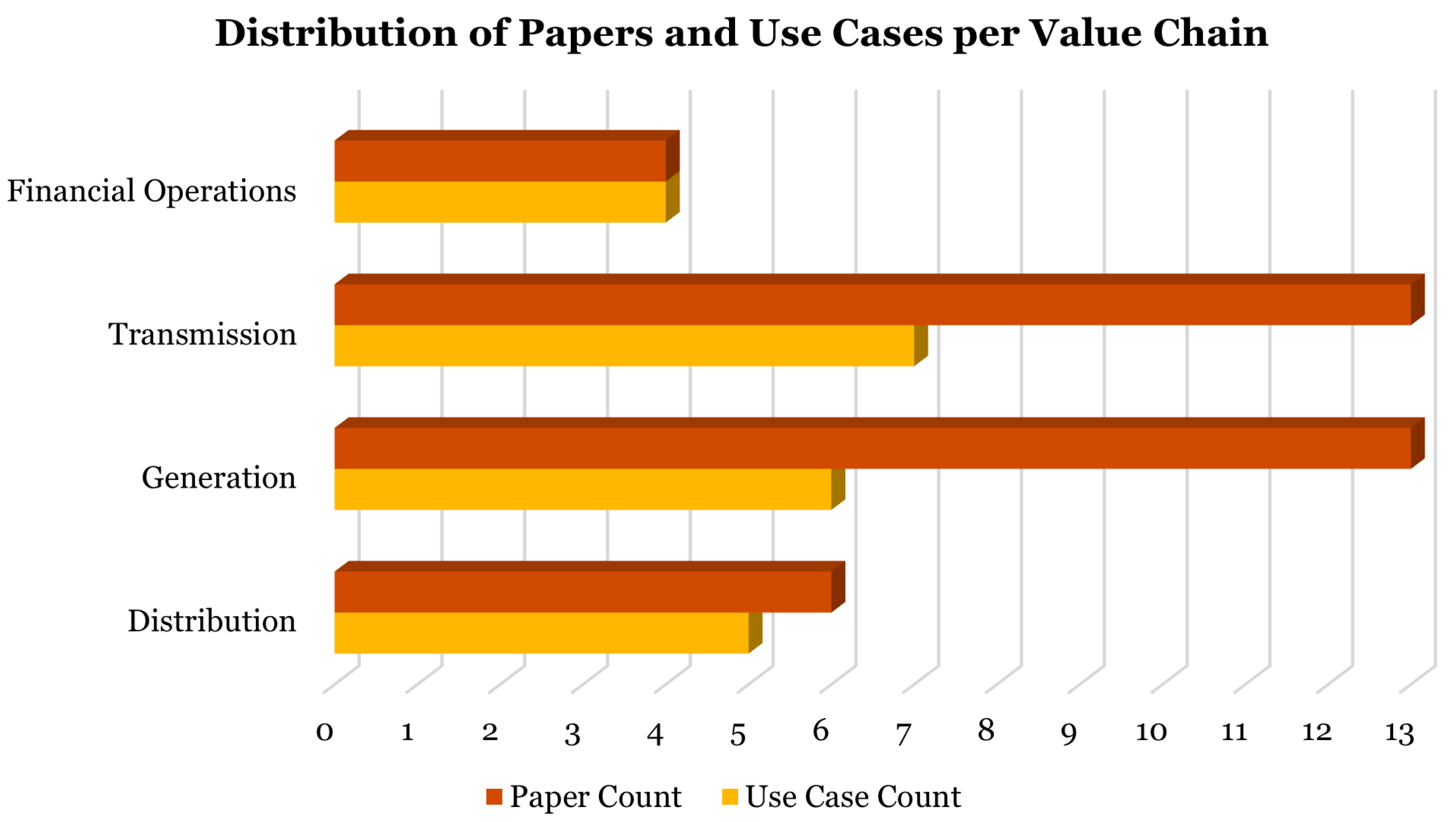

5.3. Distribution

5.3.1. Overview

5.3.2. Key Studies

5.4. Generation

5.4.1. Overview

5.4.2. Key Studies

5.5. Transmission

5.5.1. Overview

- Increased safety and reliability: particularly important in high-risk environments such as power plants and transmission lines.

- Reduced maintenance costs: enabling predictive maintenance, where potential faults can be identified before they cause significant damage. Reducing in turn maintenance costs and extending the lifespan of equipment. QML has the potential to further enhance predictive maintenance by improving the accuracy and speed of fault detection, leading to even greater cost savings and reduced downtime [88].

- Efficiency: FDD can help improve the overall efficiency of power generation and distribution, by identifying and correcting inefficiencies in the system.

5.5.2. Key Studies

- Quantum generative training: it initialize CRBM weights randomly and bias as zero vectors, then data and model expectations are computed by averaging the latent output variables and via quantum sampling respectively. Quantum sampling is performed on a quantum annealer, hence the problem should be formulated in such a way that is compatible with the QPU architecture. At every step of the training process the model parameters are updated via gradient ascent (mini batch fashion for stochasticity).

- Discriminative training: following generative training, discriminative training of the CRBM is performed. Data abstractions extracted from the CRBM are used to identify the state of the input measured data samples. The CRBM network with model parameters forms the first fully connected layer of the classification network. Those are already trained and will be fine-tuned through this phase. Directed links between conditioning and hidden layers of the CRBM are treated as FFNN with a ReLU. On top of this, an additional fully connected layer is applied and finally, a sigmoid layer is used to predict class scores for each category.

- Most algorithms are unsupervised or semi-supervised, due the difficulty of acquiring robust and reliable labels from the systems [130].

- It is unclear which architecture and approach is better: SVM could be unstable in high dim, RF overfits easily, and DL models are highly complex and require huge amount of data to be trained on, hence can perform poorly under limited data availability regimes [131].

- Non-Gaussian feature encoding for flexible, nonlinear representation.

- Gaussian quantum gates for efficient exploration of solution space.

- Re-encoding layers to enhance expressivity.

- A repetitive layered structure typical of VQC’s.

- Single-Machine Infinite-Bus (SMIB) system, one of the most widely used test systems in power system research.

- The two-area system, a benchmark system exhibiting both local and inter-area oscillation modes.

- Northeast Power Coordinating Council (NPCC) test system, a real Northeastern US power system [133].

- A classical section in which the classical data (28x28-sized image matrices) are processed into a CNN model with 5x5 kernel size and ReLu activation.

- A quantum section composed by a VQC with a ZZ-Feature-Map circuit for feature encoding layer and a Real-Amplitudes ansatz for the variational layer.

- A classical section in which the VQC parameters are optimized with classical optimization methods.

5.6. Financial Operations

5.6.1. Overview

5.6.2. Key Studies

- Linear layers before and after the VQC to extract feature representations. By compressing input features, linear layers reduce the number of qubits and considerably increase the learning ability of VQCs.

- The linear layer before the VQC’s has shared parameters across all VQC’s, to reduce parameters without losing a reduction in terms of parameters without losing too much accuracy in prediction.

- The variational layer from the original version employed CNOT operations to achieve entanglement. In this version the variational form of the VQCs is replaced by a strongly entangled controlled-Z quantum circuit. In principle, this should guarantee a stronger entanglement across qubits, giving them more expressivity.

6. Analysis and Discussion

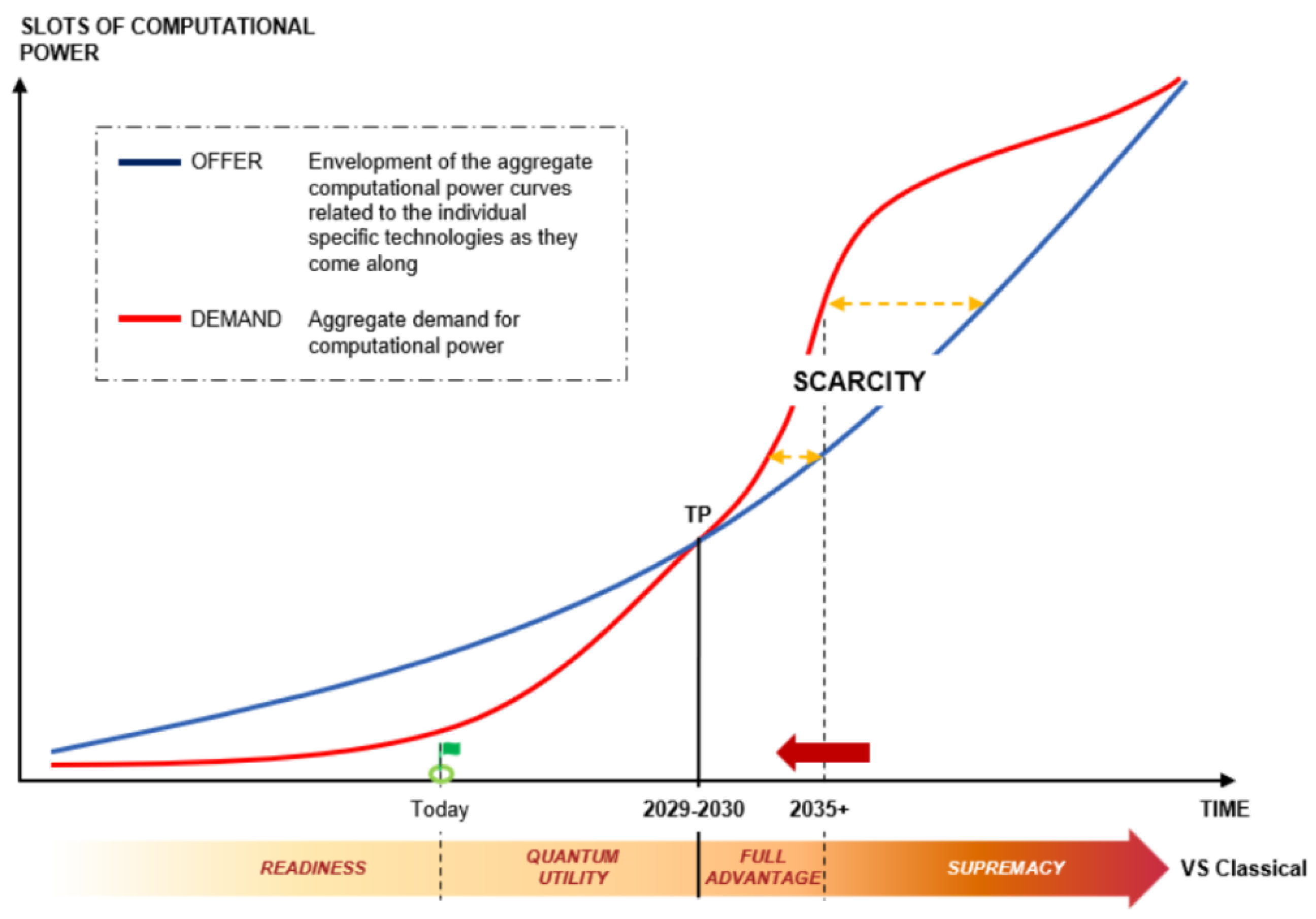

6.1. Technology Outlook

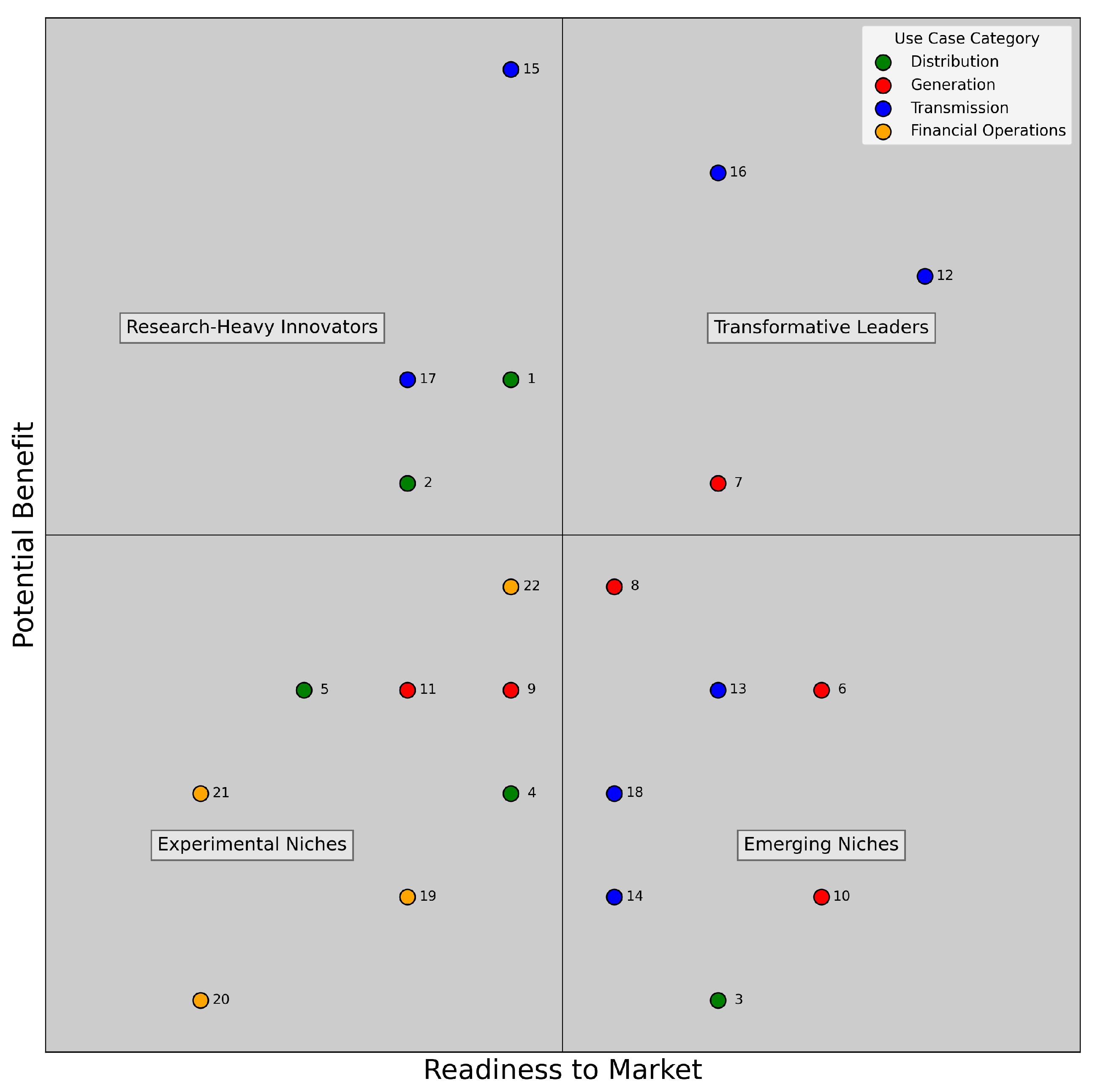

6.2. Assessment Model for Innovation Management

- Readiness to Market

- Potential Benefit

6.2.1. Readiness to Market

- Scalability: This KPI evaluates the potential for the use case to grow within the market. It considers whether it can scale as demand increases, handle larger user bases, and adapt to future needs. The criteria used to measure this KPI include the (i) user growth potential, which assesses its ability to accommodate increasing numbers of users, customers, or data, and (ii) use case flexibility, which evaluates the use case’s capacity to integrate with new technologies and adjust to changing business environments.

- Market Compatibility: This KPI assesses how ready the present environment (e.g. society, stakeholders, technology, business, ecosystem) is to the use case. The criteria used to measure this KPI are (i) customer readiness, which evaluates the target audience’s awareness and readiness to adopt the new use case and (ii) technological infrastructure which determines if the market has the required technology to support the use case

- Implementation Feasibility: This KPI assesses how ready the use case is to the present market. In other words it evaluates whether the use case integrates easily with existing systems and processes. The criteria used to measure this KPI include (i) integration complexity, which evaluates the number and complexity (customization requirements, compatibility, etc.) of integrations required with existing technologies, software, or hardware, and (ii) compliance feasibility, which assesses the ability to meet regulatory requirements, focusing on the ease and likelihood of achieving compliance.

6.2.2. Potential Benefit

- Impact on Efficiency: This KPI measures the use case’s potential to enhance operational efficiency. The criteria used to measure this KPI include (i) cost reduction, which evaluates the percentage reduction in operational or production costs post-implementation, (ii) Return on Investment (ROI), which evaluates whether the benefits of the use case justify the investment required, determining if the use case is worthwhile in relation to the resources committed, and (iii)productivity gains, which measures the improvement in system productivity.

- Criticality of the Problem: This KPI measures the severity and importance of the problem being addressed. The more urgent or impactful the problem, the higher the benefit of solving it. The criteria used to measure this KPI include (i) problem severity, which assesses how serious and urgent the problem is for the target market, stakeholders, (ii) market demand, which evaluates the extent to which the market needs a solution to this problem, and (iii) sustainability which evaluates a use case’s ability to promote long-term environmental health (resource consumption and waste), social well-being (community support), and ensure economic viability (financial stability).

- Margin for Further Improvement: This KPI measures how much the use case can be vertically and horizontally developed. The criteria used to measure this KPI include (i)the development stage, which determines the current stage of development of the use case, ranging from proposal stage to fully developed, thus reflecting the margin left for improvement. Additionally, (ii) use case performance gaps which helps identify any performance gaps in the present use case and therefore potential enhancements still necessary.

6.2.3. Results

- Transformation Leaders (upper-right): Use cases that are both market-ready and have high potential benefits.

- Experimental Niche (lower-left): Use cases that are not ready for market and offer low benefits.

- Research Heavy Innovators (upper-left): Use cases that are not market-ready but offer high potential benefits.

- Emerging Niche (lower-right): Use cases with low potential benefits but higher market readiness.

- ID 16: Power Stability Assessment

- ID 12: Fault Diagnosis in Electrical Power Systems

- ID 7: Wind speed forecasting

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 1996, pp. 212–219.

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 1997, pp. 124–134.

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S. A quantum adiabatic evolution algorithm applied to random instances of an NP-complete problem. Science 2001, 292, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biamonte, J.; Botterill, J.; et al. . Quantum Machine Learning. Nature 2017, 549, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumbling, E.; Horowitz, M. Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects; National Academies Press, 2019.

- Albash, T.; Lidar, D.A. Demonstration of a scaling advantage for a quantum annealer over simulated annealing. Physical Review X 2018, 8, 031016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, W.; Lidar, D.A. Non-stoquastic Hamiltonians in quantum annealing via geometric phases. npj Quantum Information 2017, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Chen, J.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Efficient homologous recombination-mediated genome engineering in zebrafish using TALE nucleases. Development 2014, 141, 3807–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Dong, F.; Tang, Z. Research Progress on Catalysts for the Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Methanol. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13318–13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, N.P.; Itoh, K.M.; Kim, D.; Mehta, K.K.; Northup, T.E.; Paik, H.; Palmer, B.S.; Samarth, N.; Sangtawesin, S.; Steuerman, D.W. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 2021, 372, eabb2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Y.; Amico, M.; Howell, S.; Hush, M.; Liuzzi, M.; Mundada, P.; Merkh, T.; Carvalho, A.R.; Biercuk, M.J. Experimental Deep Reinforcement Learning for Error-Robust Gate-Set Design on a Superconducting Quantum Computer. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 040324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzell, N.; Pokharel, B.; Tewala, L.; Quiroz, G.; Lidar, D.A. Dynamical decoupling for superconducting qubits: A performance survey. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 20, 064027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundada, P.; Barbosa, A.; Maity, S.; Wang, Y.; Merkh, T.; Stace, T.; Nielson, F.; Carvalho, A.; Hush, M.; Biercuk, M.; et al. Experimental Benchmarking of an Automated Deterministic Error-Suppression Workflow for Quantum Algorithms. Physical Review Applied 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallman, J.J.; Emerson, J. Noise tailoring for scalable quantum computation via randomized compiling. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 052325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, E.; Minev, Z.K.; Temme, K. Model-free readout-error mitigation for quantum expectation values. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 105, 032620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgica-Tiron, T.; Hindy, Y.; LaRose, R.; Mari, A.; Zeng, W.J. Digital zero noise extrapolation for quantum error mitigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE); 2020; pp. 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Shammah, N.; Zeng, W.J. Extending quantum probabilistic error cancellation by noise scaling. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 052607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 52, R2493–R2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E. A series of fast-paced advances in quantum error correction. Nature Reviews Physics 2024, 6, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppersmith, D. Matrix inversion with quantum mechanics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. ACM, 1994, pp. 23–31.

- Harrow, A.W.; Hassidim, A.; Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithms for fixed Qubit architectures. Physical Review Letters 2009, 103, 150502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; Nakadai, A. Quantum RAM. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100, 160501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhan, S. Quantum RAM with O(1) Query Complexity. Physical Review Letters 2018, 121, 030501. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrato, J.; et al. Quantum-Inspired Algorithms: A Review and Perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2023, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kandala, A.; et al. . Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 2017, 549, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, J.R.; et al. . The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. New Journal of Physics 2016, 18, 023023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanov, Y.S.; Armaos, V.; Barnes, C.H.; Arvidsson-Shukur, D.R. Qubit-excitation-based adaptive variational quantum eigensolver. Communications Physics 2021, 4, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekos, K.; Brand, D.; Ceschini, A.; Chou, C.H.; Li, R.H.; Pandya, K.; Summer, A. A review on quantum approximate optimization algorithm and its variants. Physics Reports 2024, 1068, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottou, L.; Curtis, F.E.; Nocedal, J. Optimization Methods for Large-Scale Machine Learning. SIAM Review 2018, 60, 223–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, J.R.; Sweke, R.; Rungger, I.; et al. . Cost function dependent barren plateaus in shallow parametrized quantum circuits. Physical Review A 2018, 98, 042324. [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo, M.; et al. . Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Z.; et al. . Connecting Ansatz Expressibility to Gradient Magnitudes and Barren Plateaus. Quantum 2021, 5, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, T.L.; Najafi, K.; Gao, X.; Yelin, S.F. Entanglement devised barren plateau mitigation. Physical Review Research 2021, 3, 033090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, L.; Maziero, J. Avoiding barren plateaus with classical deep neural networks. Physical Review A 2022, 106, 042433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.K.; Huang, J.; Wang, X. Mitigating barren plateaus of variational quantum eigensolvers. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Rashid, M.; Al-Kuwari, S.; Shafique, M. Alleviating barren plateaus in parameterized quantum machine learning circuits: Investigating advanced parameter initialization strategies. In Proceedings of the 2024 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, M.S.; Miller, J.; Motlagh, D.; Chen, J.; Acharya, A.; Perdomo-Ortiz, A. Synergy between quantum circuits and tensor networks: Short-cutting the race to practical quantum advantage. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.13673 2022.

- Skolik, A.; McClean, J.R.; Mohseni, M.; Van Der Smagt, P.; Leib, M. Layerwise learning for quantum neural networks. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2021, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, S. Bit-bit encoding, optimizer-free training and sub-net initialization: techniques for scalable quantum machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.02148 2025.

- Lloyd, S.; Schuld, M.; Ijaz, A.; Izaac, J.; Killoran, N. Quantum embeddings for machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.03622 2020.

- Ma, Y.; Tresp, V.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y. Variational quantum circuit model for knowledge graph embedding. Advanced Quantum Technologies 2019, 2, 1800078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, T.; Kim, L.; Park, D.K. Quantum convolutional neural network for classical data classification. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2022, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, V.; Córcoles, A.D.; Temme, K.; Harrow, A.W.; Kandala, A.; Chow, J.M.; Gambetta, J.M. Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature 2019, 567, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, M.; Arrasmith, A.; Babbush, R.; Benjamin, S.C.; Endo, S.; Fujii, K.; McClean, J.R.; Mitarai, K.; Yuan, X.; Cincio, L.; et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengoni, R.; Di Pierro, A. Kernel methods in quantum machine learning. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Killoran, N. Quantum machine learning in feature hilbert spaces. Physical review letters 2019, 122, 040504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Kaulgud, N. Quantum machine learning for support vector machine classification. Evolutionary Intelligence 2024, 17, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentinetta, G.; Thomsen, A.; Sutter, D.; Woerner, S. The complexity of quantum support vector machines. Quantum 2024, 8, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Herbrich, R.; Smola, A.J. A generalized representer theorem. In Proceedings of the International conference on computational learning theory. Springer; 2001; pp. 416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Jerbi, S.; Fiderer, L.J.; Poulsen Nautrup, H.; Kübler, J.M.; Briegel, H.J.; Dunjko, V. Quantum machine learning beyond kernel methods. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding machine learning: From theory to algorithms; Cambridge university press, 2014.

- Gil Vidal, F.J.; Theis, D.O. Input redundancy for parameterized quantum circuits. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Sweke, R.; Meyer, J.J. Effect of data encoding on the expressive power of variational quantum-machine-learning models. Physical Review A 2021, 103, 032430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, M.C.; Gil-Fuster, E.; Meyer, J.J.; Eisert, J.; Sweke, R. Encoding-dependent generalization bounds for parametrized quantum circuits. Quantum 2021, 5, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salinas, A.; Cervera-Lierta, A.; Gil-Fuster, E.; Latorre, J.I. Data re-uploading for a universal quantum classifier. Quantum 2020, 4, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.H.; Pei, J.J.; Zhang, T.F.; Zhou, N.R. Quantum convolutional neural network based on variational quantum circuits. Optics Communications 2024, 550, 129993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastianelli, A.; Zaidenberg, D.A.; Spiller, D.; Le Saux, B.; Ullo, S.L. On circuit-based hybrid quantum neural networks for remote sensing imagery classification. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 15, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chu, P.C.; Liu, G.Z.; Tian, Y.B.; Qiu, T.H.; Wang, S.M. An image classification algorithm based on hybrid quantum classical convolutional neural network. Quantum Engineering 2022, 2022, 5701479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhan, D.; Mastiukova, A.S.; Boev, A.S.; Trubnikov, D.N.; Fedorov, A.K. Multiclass classification using quantum convolutional neural networks with hybrid quantum-classical learning. Frontiers in Physics 2022, 10, 1069985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari Dacrema, M.; Moroni, F.; Nembrini, R.; Ferro, N.; Faggioli, G.; Cremonesi, P. Towards feature selection for ranking and classification exploiting quantum annealers. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2022, pp.2814–2824.

- Thakkar, S.; Kazdaghli, S.; Mathur, N.; Kerenidis, I.; Ferreira-Martins, A.J.; Brito, S. Improved financial forecasting via quantum machine learning. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.; Selvarajan, R.; Aldwairi, T.; Koshka, Y.; Novotny, M.A.; Humble, T.S.; Alam, M.A.; Kais, S. Training a quantum annealing based restricted boltzmann machine on cybersecurity data. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2021, 6, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, L.; Prati, E. Anomaly detection speed-up by quantum restricted Boltzmann machines. Communications Physics 2023, 6, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Next Generation EU. https://next-generation-eu.europa.eu/index_en. Accessed: 2023-10-05.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutakki, M.; Koduru, S.; Mandava, S.; et al. Quantum support vector machine for forecasting house energy consumption: a comparative study with deep learning models. Journal of Cloud Computing 2024, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, A.; Badamchizadeh, M.A. NeuroQuMan: Quantum neural network-based consumer reaction time demand response predictive management. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 19121–19138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; You, F. Variational quantum circuit based demand response in buildings leveraging a hybrid quantum-classical strategy. Applied Energy 2024, 364, 123244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, E.; Cuéllar, M.P.; Navarro, G. On the use of quantum reinforcement learning in energy-efficiency scenarios. Energies 2022, 15, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitidis, A.I.; Valdez, L.A.; Alamaniotis, M. A Quantum Machine Learning Methodology for Precise Appliance Identification in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y. Quantum machine learning for electricity theft detection: An initial investigation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing & Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical & Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics). IEEE, 2021, pp. 204–208.

- Senekane, M.; Taele, B.M.; et al. Prediction of solar irradiation using quantum support vector machine learning algorithm. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy 2016, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hu, G.; Liu, C.; Xiong, J.; Wu, Z. Prediction of solar irradiance one hour ahead based on quantum long short-term memory network. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2023, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Santos, V.; Marinho, F.P.; Costa Rocha, P.A.; Thé, J.V.G.; Gharabaghi, B. Application of Quantum Neural Network for Solar Irradiance Forecasting: A Case Study Using the Folsom Dataset, California. Energies 2024, 17, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Lopez, D.J.D.; Wang, Y.Y. Solar Irradiance Forecasting using a Hybrid Quantum Neural Network: A Comparison on GPU-based Workflow Development Platforms. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushmit, M.M.; Mahbubul, I.M. Forecasting solar irradiance with hybrid classical–quantum models: A comprehensive evaluation of deep learning and quantum-enhanced techniques. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 294, 117555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Arce, C.J.E.; Huang, T.W. A Robust Hybrid Classical and Quantum Model for Short-Term Wind Speed Forecasting. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Chen, N.Y.; Li, T.Y.; Chen, K.C.; et al. Quantum Kernel-Based Long Short-term Memory for Climate Time-Series Forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08851 2024.

- Jaderberg, B.; Gentile, A.A.; Ghosh, A.; Elfving, V.E.; Jones, C.; Vodola, D.; Manobianco, J.; Weiss, H. Potential of quantum scientific machine learning applied to weather modelling. arXiv 2024, [arXiv:quant-ph/2404.08737].

- Sagingalieva, A.; Komornyik, S.; Senokosov, A.; Joshi, A.; Sedykh, A.; Mansell, C.; Tsurkan, O.; Pinto, K.; Pflitsch, M.; Melnikov, A. Photovoltaic power forecasting using quantum machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16379 2023.

- Khan, S.Z.; Muzammil, N.; Ghafoor, S.; Khan, H.; Zaidi, S.M.H.; Aljohani, A.J.; Aziz, I. Quantum long short-term memory (QLSTM) vs. classical LSTM in time series forecasting: a comparative study in solar power forecasting. Frontiers in Physics 2024, 12, 1439180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; He, Y.; Li, H. Deep Learning Model for Short-term Photovoltaic Power Prediction Based on Data Augmentation and Quantum Computing. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC), 2024, pp. 4097–4102. [CrossRef]

- Hangun, B.; Akpinar, E.; Oduncuoglu, M.; Altun, O.; Eyecioglu, O. A Hybrid Quantum-Classical Machine Learning Approach to Offshore Wind Farm Power Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1105–1110.

- Uehara, G.S.; Narayanaswamy, V.; Tepedelenlioglu, C.; Spanias, A. Quantum Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Topology Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; You, F. Quantum computing based hybrid deep learning for fault diagnosis in electrical power systems. Applied Energy 2021, 303, 117628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, G.; Rao, S.; Dobson, M.; Tepedelenlioglu, C.; Spanias, A. Quantum Neural Network Parameter Estimation for Photovoltaic Fault Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), 2021, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Jullian, C.; Cofre-Martel, S.; Martin, G.S.; Droguett, E.L.; de Novaes Pires Leite, G.; Costa, A. Exploring Quantum Machine Learning and Feature Reduction Techniques for Wind Turbine Pitch Fault Detection. Energies 2022, 15, Article–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbashie, S.M.; Olatunji, O.O.; Adedeji, P.A.; Madushele, N. Hybrid Quantum Convolutional Neural Network for Defect Detection in a Wind Turbine Gearbox. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica; 2024; pp. 01–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P. Noise-Resilient Quantum Machine Learning for Stability Assessment of Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2023, 38, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabadra, T.; Yu, S.; Zhou, Y. Quantum Kernel Based Transient Stability Assessment of Power Systems and Its Implementation in NISQ Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), 2024, pp. 7402–7406. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhou, Y. Quantum Adversarial Machine Learning for Robust Power System Stability Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L. Quantum-Enabled Distributed Transient Stability Assessment of Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), 2024, Vol. 01, pp. 593–599. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y. Extended Abstract: Quantum-Accelerated Transient Stability Assessment for Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), 2024, pp. 593–594. [CrossRef]

- afari, H.; Aghababa, H.; Barati, M. Quantum Leaps: Dynamic Event Identification using Phasor Measurement Units in Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Grid Synchronized Measurements and Analytics (SGSMA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Wang, Q.L.; Jin, Y.; Li, X.H.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Zhang, K.J.; Liu, H.; Cheng, L. An advanced quantum support vector machine for power quality disturbance detection and identification. EPJ Quantum Technology 2024, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangun, B.; Eyecioglu, O.; Altun, O. Quantum Computing Approach to Smart Grid Stability Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid), 2024, pp. 840–843. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Fei, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J. Linear-layer-enhanced quantum long short-term memory for carbon price forecasting. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2023, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, H.; Cao, Y.; Fei, X.; Liang, G.; Zhao, J. Carbon market risk estimation using quantum conditional generative adversarial network and amplitude estimation. Energy Conversion and Economics 2024, 5, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Dohare, U.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N. Blockchain Based Optimized Energy Trading for E-Mobility Using Quantum Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 5167–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, K.B.; Mourshed, M. Forecasting methods in energy planning models. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 88, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Fan, S.; Kjaerbye, S.E. Probabilistic Electric Load Forecasting: A Tutorial Review. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 35, 2060–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Perez, J.; Santos, M. Energy Demand Models For Policy Formulation: A Comparative Study Of Energy Demand Models. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111–418. [Google Scholar]

- Malshe, R.; Deshmukh, S.R.; Khandare, A. Electrical Load Forecasting Models: A Critical Systematic Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 131, 109–974. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yan, C.; Liu, X. A Review of Data-Driven Building Energy Consumption Prediction Studies. Applied Energy 2019, 236, 797–809. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, N.; Li, C.; Peng, X.; Zeng, F.; Lu, X. Conventional models and artificial intelligence-based models for energy consumption forecasting: A review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 181, 106–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time series analysis: forecasting and control; John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Shahid, M.; Yahya, S.; Khan, M.A. Computational Intelligence Approaches for Energy Load Forecasting in Smart Energy Management Grids: State of the Art, Future Challenges, and Research Directions. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, K.J.; Hu, H.T. Fitting Curves to Data Using Nonlinear Regression: A Practical and Nonmathematical Review. Creative Education 2020, 11, 733–748. [Google Scholar]

- Mehr, A.D.; Bagheri, F.; Safari, M.J.S. Electrical energy demand prediction: A comparison between genetic programming and decision tree. Gazi University Journal of Science 2020, 33, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Multiscale Stochastic Prediction of Electricity Demand in Smart Grids Using Bayesian Networks. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2022, 13, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Alahakoon, D.; Awan, I. A Novel Energy Demand Prediction Strategy for Residential Buildings Based on Ensemble Learning. Energy 2021, 230, 120–813. [Google Scholar]

- Tzanetos, A.; Dounias, G. An application-based taxonomy of nature inspired intelligent algorithms. Management and Decision Engineering Laboratory (MDE-Lab) University of the Aegean, School of Engineering, Department of Financial and Management Engineering, Chios 2019.

- Andersson, M. Modeling electricity load curves with hidden Markov models for demand-side management status estimation. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 2017, 27, e2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Efendi, R.; Deris, M.M. Application of fuzzy time series approach in electric load forecasting. New Mathematics and Natural Computation 2015, 11, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C. Electricity consumption prediction using a neural-network-based grey forecasting approach. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2017, 68, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yano, H.; Gao, Q.; Uno, S.; Tanaka, T.; Akiyama, M.; Yamamoto, N. Analysis and synthesis of feature map for kernel-based quantum classifier. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2020, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallal, M.; Chabaa, S.; Zeroual, A. A novel deep neural network based on randomly occurring distributed delayed PSO algorithm for monitoring the energy produced by four dual-axis solar trackers. Renewable Energy 2020, 149, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharadga, H.; Hajimirza, S.; Balog, R. Time series forecasting of solar power generation for large-scale photovoltaic plants. Renewable Energy 2020, 150, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Benefits of physical and machine learning hybridization for photovoltaic power forecasting. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 168, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essam, Y.; Ahmed, A.; Ramli, R.; Chau, K.; Ibrahim, M.; Sherif, M.; Sefelnasr, A.; El-Shafie, A. Investigating photovoltaic solar power output forecasting using machine learning algorithms. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2022, 16, 2002–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Xu, N.; Du, J. Experimental realization of a quantum support vector machine. Physical review letters 2015, 114, 140504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashinath, K.; Mustafa, M.; Albert, A.; Wu, J.L.; Jiang, C.; Esmaeilzadeh, S.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Wang, R.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Singh, A.; et al. Physics-informed machine learning: case studies for weather and climate modelling. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2021, 379, 20200093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Trevisan, L.V.; Salvia, A.L.; Mazutti, J.; Dibbern, T.; de Maya, S.R.; Bernal, E.F.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Sharifi, A.; del-Carmen Alarcón-del Amo, M.; et al. Prosumers and sustainable development: An international assessment in the field of renewable energy. Sustainable Futures 2024, 7, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.D. UW Power Systems Test Case Archive. http://labs.ece.uw.edu/pstca/, 2018. Accessed: [Insert date of access here].

- Silva, K.; Souza, B.; Brito, N. Fault Detection and Classification in Transmission Lines Based on Wavelet Transform and ANN. Power Delivery, IEEE Transactions on 2006, 21, 2058–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S. Decision tree-based fault zone identification and fault classification in flexible AC transmissions-based transmission line. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2009, 3, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, A. PVWatts Version 1 Technical Reference. Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-60272, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2013. Online resource (8 pages).

- Leahy, K.; Gallagher, C.; O’Donovan, P.; Bruton, K.; O’Sullivan, D.T.J. A Robust Prescriptive Framework and Performance Metric for Diagnosing and Predicting Wind Turbine Faults Based on SCADA and Alarms Data with Case Study. Energies 2018, 11, Article–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, O.; Wang, Q.; Svensén, M.; Dersin, P.; Lee, W.J.; Ducoffe, M. Potential, challenges and future directions for deep learning in prognostics and health management applications. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 92, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetco, A.; Dinmohammadi, F.; Zhao, X.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Barnes, M.; Keane, J.; Nenadic, G. Machine learning methods for wind turbine condition monitoring: A review. Renewable Energy 2019, 133, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.W.; Pai, M.A.; Chow, J.H. Sauer, P.W.; Pai, M.A.; Chow, J.H. Power System Dynamics and Stability: With Synchrophasor Measurement and Power System Toolbox; Wiley-IEEE Press, 2017.

- Fei, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Shu, T.; Wen, F. Power system fault diagnosis with quantum computing and efficient gate decomposition. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ink, H.; LaCava, W.; van Dam, J.; McNiff, B.; Sheng, S.; Wallen, R.; McDade, M.; Lambert, S.; Butterfield, S.; Oyague, F. Gearbox Reliability Collaborative Project Report: Findings from Phase 1 and Phase 2 Testing. Technical report, National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL), Golden, CO (United States), 2011. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Long, Q. A modification of adaptive moment estimation (adam) for machine learning. Journal of Industrial and Management Optimization 2024, 20, 2516–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.C.; Yoo, S.; Fang, Y.L.L. Quantum Long Short-Term Memory. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022; pp. 8622–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska-Ziarko, A.; Markowski, L.; Pyke, C.; Amin, S. Conventional and downside CAPM: The case of London stock exchange. Global Finance Journal 2022, 54, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, L.T.; Kim, K.S.; Su, Y. Reexamination of Estimating Beta Coefficient as a Risk Measure in CAPM. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 2018, 5, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, G. Monte Carlo Methods for Value-at-Risk and Conditional Value-at-Risk: A Review. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 2014, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z. Sensitivity estimation of conditional value at risk using randomized quasi-Monte Carlo. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 298, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.H.; Wei, Y.M.; Wang, K. Estimating risk for the carbon market via extreme value theory: An empirical analysis of the EU ETS. Applied Energy 2012, 99, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, D.J.; Gambella, C.; Marecek, J.; McFaddin, S.; Mevissen, M.; Raymond, R.; Simonetto, A.; Woerner, S.; Yndurain, E. Quantum Computing for Finance: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2020, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenninger, J. Quantum Optimization for the Future Energy Grid: Summary and Quantum Utility Prospects, 2024. To appear. [CrossRef]

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual, 2023.

- McGeoch, C.; Farre, P.; Bernoudy, W. D-Wave Hybrid Solver Service + Advantage: Technology Update. Technical report, D-Wave Systems Inc., 2020.

- Kjaergaard, M.; Schwartz, M.E.; Braumüller, J.; Krantz, P.; Wang, J.I.J.; Gustavsson, S.; Oliver, W.D. Superconducting qubits: Current state of play. Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics 2020, 11, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantum, G.A. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 2023, 614, 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- Putterman, H.; Noh, K.; Hann, C.T.; MacCabe, G.S.; Aghaeimeibodi, S.; Patel, R.N.; Lee, M.; Jones, W.M.; Moradinejad, H.; Rodriguez, R.; et al. Hardware-efficient quantum error correction via concatenated bosonic qubits. Nature 2025, 638, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaee Rad, H.; Ainsworth, T.; Alexander, R.; Altieri, B.; Askarani, M.; Baby, R.; Banchi, L.; Baragiola, B.; Bourassa, J.; Chadwick, R.; et al. Scaling and networking a modular photonic quantum computer. Nature 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, E.; San-Jose, P.; de Moor, M.W.; Geresdi, A.; Lee, E.J.; Klinovaja, J.; Loss, D.; Nygård, J.; Aguado, R.; Kouwenhoven, L.P. From Andreev to Majorana bound states in hybrid superconductor–semiconductor nanowires. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantum, M.A.; Aghaee, M.; Alcaraz Ramirez, A.; Alam, Z.; Ali, R.; Andrzejczuk, M.; Antipov, A.; Astafev, M.; Barzegar, A.; Bauer, B.; et al. Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs–Al hybrid devices. Nature 2025, 638, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkard, G.; Ladd, T.D.; Pan, A.; Nichol, J.M.; Petta, J.R. Semiconductor spin qubits. Reviews of Modern Physics 2023, 95, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriet, L.; Beguin, L.; Signoles, A.; Lahaye, T.; Browaeys, A.; Reymond, G.O.; Jurczak, C. Quantum computing with neutral atoms. Quantum 2020, 4, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzewicz, C.D.; Chiaverini, J.; McConnell, R.; Sage, J.M. Trapped-ion quantum computing: Progress and challenges. Applied physics reviews 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Eddins, A.; Anand, S.; Wei, K.X.; Van Den Berg, E.; Rosenblatt, S.; Nayfeh, H.; Wu, Y.; Zaletel, M.; Temme, K.; et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 2023, 618, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. Superconducting Quantum Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- IonQ. Trapped Ion Quantum Computing, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Quera. Quantum Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Google Quantum, AI. Quantum AI Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Pasqal. Our Technology and Quantum Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- MeetIQM. Technology Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Alice and Bob. Quantum Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Microsoft. Topological Quantum Roadmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Quantinuum. Accelerated Roadmap to Universal Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing by 2030, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-14.

- Héder, M. From NASA to EU: the evolution of the TRL scale in Public Sector Innovation. The Innovation Journal 2017, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Schiffner, S.; Schmitz, S. SMART: a Technology Readiness Methodology in the Frame of the NIS Directive. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.00546 2022.

| Value Chain | Category | Use Case | Reference | ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Demand Response Systems | Load Forecasting for Demand Response | [67,68] | 1 |

| Automated Demand Response in Smart Cities | [69] | 2 | ||

| Smart Grid Management | HVAC Automated Control in Buildings | [70] | 3 | |

| Appliance Load Signature Identification | [71] | 4 | ||

| Electricity Theft Detection | [72] | 5 | ||

| Generation | Indirect Generation Forecasting | Solar Irradiation Forecasting | [73,74,75,76,77] | 6 |

| Wind Speed Forecasting | [78] | 7 | ||

| Weather and Climate Modeling | [79,80] | 8 | ||

| Direct Generation Forecasting | Photovoltaic Power Forecasting | [81,82,83] | 9 | |

| Forecasting Power from Offshore Wind Farms | [84] | 10 | ||

| Plant Operations | PV Array Topology Optimization | [85] | 11 | |

| Transmission | Maintenance | Fault Diagnosis in Electrical Power Systems | [86] | 12 |

| Photovoltaic Panels Fault Detection | [87] | 13 | ||

| Wind Turbine Pitch Fault Detection | [88] | 14 | ||

| Defect Detection in Wind Turbine Gearbox | [89] | 15 | ||

| Grid Operations | Power System Stability Assessment | [90,91,92,93,94] | 16 | |

| Power Disturbances and Events Identification | [95,96] | 17 | ||

| Smart Grid Stability Forecasting | [97] | 18 | ||

| Financial Operations |

Finance for Sustainable Energy | Carbon Price Forecasting | [98] | 19 |

| Carbon Market Risk Estimation | [99] | 20 | ||

| Blockchain-based P2P Energy Trading for E-Mobility | [100] | 21 | ||

| Smart Energy Distribution | Optimal Scheduling of EV Recharges | [70] | 22 |

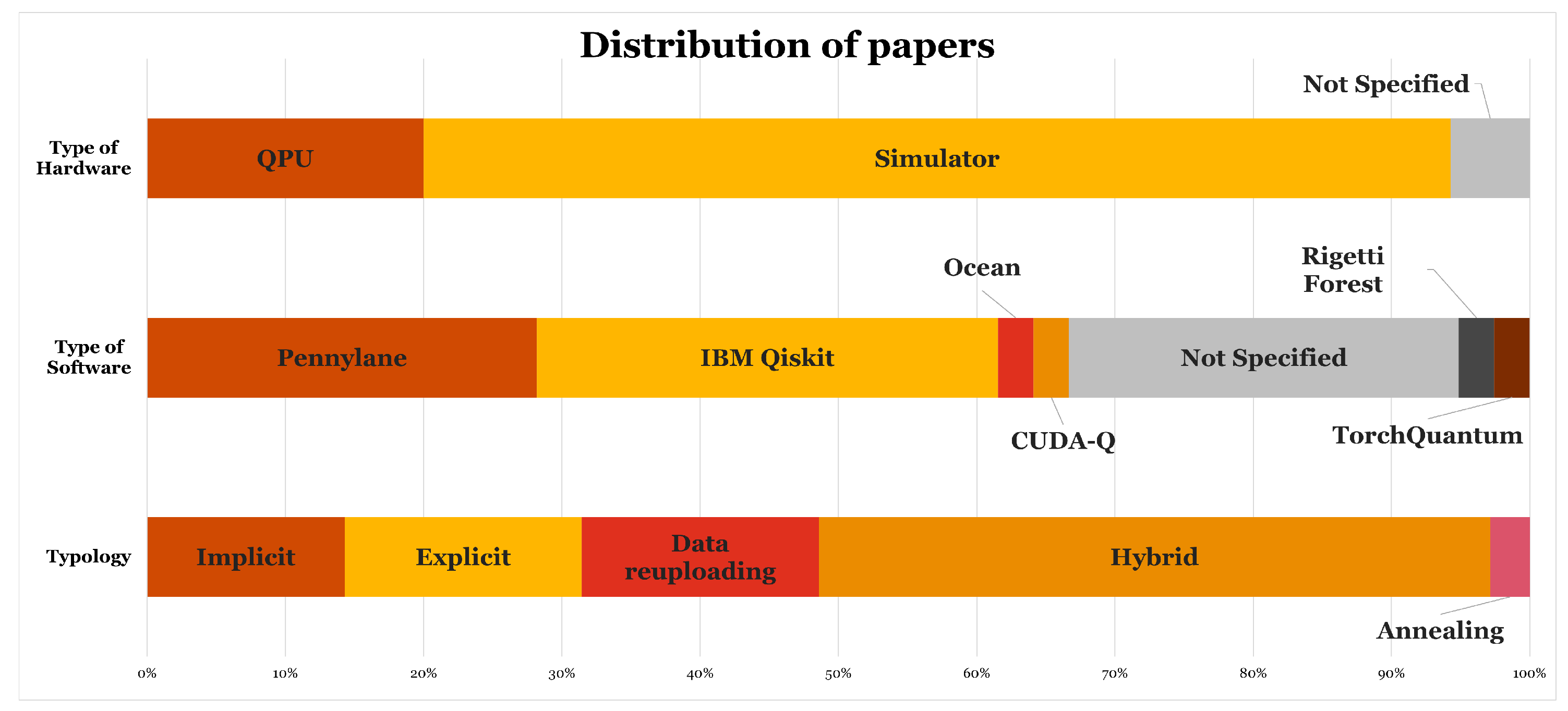

| ID | Method | Typology | SW Technology | HW Technology | Reported Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QSVM | Implicit | Not Specified | Not Specified | RNN, LSTM |

| QNN | Data re-uploading | PennyLane, IBM Quantum Lab | IBM (various devices) | ARIMA, SARIMA, RNN, LSTM, GRU, Ensemble Learning | |

| 2 | Hybrid RL | Hybrid | IBM Qiskit | IBM Brisbane | MPC, DDPG, Lo-DDPG |

| 3 | Hybrid RL | Hybrid | Not Specified | Simulator | NN |

| 4 | VQC | Explicit | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | CNN |

| 5 | VQC | Explicit | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | None |

| 6 | QSVM | Explicit | Not Specified | Simulator | None |

| QLSTM | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | SARIMA, CNN, RNN, GRU, LSTM | |

| QNN | Data re-uploading | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | SVR, XGBoost, GMDH | |

| Hybrid CNN | Hybrid | PennyLane, Torchquantum, CUDA Quantum | Simulator | CNN | |

| Hybrid QNN | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | RNN, LSTM | |

| 7 | QLSTM | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | RF, SVR, XGBoost, NAR, LSTM, LSTM AE |

| 8 | QK-LSTM | Implicit | Not Specified | Simulator | LSTM |

| Physics Informed QNN | Data re-uploading | Not Specified | Not Specified | Spectral Element Method | |

| 9 | QNN, QLSTM, QSeq2Seq | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | RNN, LSTM |

| QLSTM | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | LSTM | |

| VAE-GWO-VQC-GRU | Hybrid | Not Specified | Simulator | GRU | |

| 10 | Hybrid QNN-SVR | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | None |

| 11 | Hybrid QNN | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | NN |

| 12 | Quantum Sampling for CRBM | Annealing | Ocean (D-Wave SDK) | DWave 2000 QPU | NN, DT |

| 13 | QNN | Hybrid | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | NN |

| 14 | QSVM | Implicit | Not Specified | Simulator | RF, k-NN, L-SVM, RBF-SVM |

| 15 | Hybrid CNN | Explicit | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | H-CNN versions |

| 16 | QNN | Data re-uploading | IBM Qiskit | Simulator, ibmq_boeblingen QPU | None |

| QEK with VQC | Implicit | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | Classical kernel methods | |

| QaTSA with ReHELD VQC | Explicit | Not Specified | Simulator | None | |

| QFL with HELD QNNs | Data re-uploading | IBM Qiskit, PennyLane | Simulator, IBM ibm_lagos (7-qubit QPU) | NN | |

| QPCA + VQA | Hybrid | Not Specified | Simulator | PCA | |

| 17 | QVR | Explicit | IBM Qiskit | IBM Falcon r5.11H QPU | LSTM |

| QSVM | Implicit | IBM Qiskit | Simulator | SVM, other classical PQD methods | |

| 18 | VQC | Explicit | Not Specified | Simulator | SVM |

| 19 | QLSTM | Hybrid | PennyLane | Simulator | QLSTM versions |

| 20 | QCGAN + QAE | Data re-uploading | IBM Qiskit | Simulator, IBM QPU | Historical simulation, CGAN, QCGAN |

| 21 | Hybrid RL | Hybrid | Rigetti Forest (PyQuil) | Simulator | Deep Q-Learning |

| 22 | Hybrid RL | Hybrid | Not Specified | Simulator | NN-based RL |

| ID | Scalability | Market Compatibility | Implementation Feasibility | Total Readiness to Market | Impact on Efficiency | Criticality of the Problem | Margin for Further Improvement | Total Potential Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 9 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 10 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| 12 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| 13 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| 14 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 15 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 11 |

| 17 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| 18 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 19 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 20 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 21 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 22 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).