1. Introduction

Service robots are increasingly being deployed in everyday environments such as museums, restaurants, and public facilities, moving beyond the confines of laboratory testing. As these robots become integrated into various aspects of daily life, it has become critically important to understand how users interact with them from a Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) perspective. This is particularly relevant in the service sector, where optimizing user-robot interactions is essential for delivering meaningful and satisfying user experiences.

Traditionally, HRI research has relied heavily on survey-based methods to assess user perceptions and preferences. However, surveys often fall short in capturing the subtle, dynamic, and context-dependent behaviors that occur in real-world settings. Designing robots that can effectively respond to the diverse needs of users in complex public environments requires moving beyond self-reported data and adopting more naturalistic investigative methods.

Observational methods offer a distinct advantage in HRI research by capturing user behavior. Among various observational techniques, naturalistic observation is particularly valuable for identifying authentic behavioral patterns as they occur in real-life contexts. By studying behavior in everyday environments without experimental interference, researchers can uncover subtle interaction dynamics that are often difficult to detect through surveys, controlled experiments, or post-hoc interviews. Despite these advantages, prior studies in HRI have frequently lacked structured analytical frameworks to systematically interpret behavioral data, limiting the generalizability and practical application of their findings.

To address this limitation, the present study introduces a dual-level analytical approach to behavioral observation, which integrates group-level statistical analysis based on demographic factors with individual-level temporal modeling of user engagement. This approach is intended to support a more comprehensive understanding of HRI in real-world public settings and to inform the practical deployment of socially engaging and adaptive service robots.

2. Related Works

Service robots are increasingly being integrated into daily life, accompanied by a rise in large-scale field studies. This trend has led to growing interest in observational research methods suited for real-world settings. As a result, recent efforts in the HRI field have focused on systematizing observational research methodologies, and recent studies have been introduced that examine human behavior through observational techniques.

In HRI research, field studies have frequently employed observational methods to explore diverse user behaviors and perceptions, especially in deployment contexts outside the laboratory. One of the key strengths of observational research is its ability to capture behaviors in natural environments where direct intervention may be impractical or disruptive [

1]. This is especially valuable in everyday social settings and public-facing environments, where artificial manipulation could unintentionally influence the behaviors being observed. By capturing user behavior in its natural context, observational methods allow researchers to identify genuine interaction patterns and uncover insights that are often inaccessible through surveys or controlled experiments [

2].

In this way, observational data complement self-reported measures by providing a more accurate reflection of actual user behavior and mitigating biases inherent in retrospective reporting [

40]. These strengths are particularly evident in analytical observational studies, which allow researchers to investigate behavioral outcomes in real-world settings without experimental manipulation, while still enabling causal inference through advanced techniques such as matching and stratification [

3].

Recent studies have demonstrated the value of observational approaches in public and semi-public environments. For instance, Babel et al. analyzed pedestrian interactions with cleaning robots in train stations, identifying points of conflict and proposing design strategies to enhance robot acceptance [

4]. Laura-Dora et al. examined how greeting behaviors used by a museum guide robot influenced visitor engagement, highlighting the role of spatial and cultural context in shaping HRI [

5,

6]. Lettinger et al. applied the Technology Acceptance Model [

8] to study elderly users’ interactions with a social assistive robot in nursing homes, reporting generally positive emotional responses and improved social communication [

7].

Matsumoto et al. proposed a conceptual approach to proximate human-robot teaming, which considers various task contexts, platforms, and sensors. Their approach supports the exploration of complex HRI components through iterative and time-series data collection and analysis [

13]. However, the framework lacks specific methodological guidance, instead offering a high-level overview of potential components such as research questions, task environments, and analysis methods ranging from causal inference to quantitative assessment.

Lee et al. introduced an approach utilizing causal inference based on conditional probabilities to identify cause-effect relationships in observational settings, especially when randomized controlled trials are infeasible. Their method was applied to consumer robot usage data, offering tools for HRI researchers to apply causal analysis to real-world scenarios [

14]. However, while their study presents various use cases involving household robots, it does not fully explore the breadth of HRI contexts where causal inference could be applied. Moreover, the model is not readily adaptable to complex public settings such as museums, where a large and unspecified number of people interact with robots.

Similarly, Boos et al. proposed the Compliance–Reactance Framework, which uses conditional probabilities to evaluate human responses to robot cues in both experimental and field studies [

15]. This framework supports the analysis of compliance, cooperation, and resistance behaviors and offers recommendations for improving robot interaction design. However, it primarily focuses on the binary presence or absence of compliance, overlooking the nuanced progression of user engagement.

Kim et al. conducted an observational study using Bayesian networks to model subtle engagement behaviors in interactions between individual children with autism spectrum disorders and a social robot [

16]. Their research showed the feasibility of probabilistic inference in understanding complex interaction dynamics in therapeutic contexts. However, the study focused on a highly specific setting—prosocial skill development in autism therapy—and involved a small sample size, limiting the generalizability of its findings.

While these studies illustrate the utility of observational approaches in informing user-centered robot design and deployment, much of the literature still lacks structured and reproducible analytical methods for interpreting behavioral data. Prior work has often relied on qualitative categorization or descriptive reporting, without the use of standardized coding schemes or formal behavior modeling frameworks [

9].

To address these gaps, the present study proposes a structured dual-level observational approach tailored to the HRI context. This approach includes an adaptable, low-specificity behavior coding scheme grounded in formalized behavioral grammar and combines statistical analysis of group-level behavioral trends with temporal modeling of individual engagement using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [

12]. By integrating both group- and individual-level analyses, our approach improves the interpretability and generalizability of observational data, contributing to the advancement of HRI methodology and supporting the practical deployment of social robots in real-world public environments.

Unlike previous studies, we place a central focus on the behavioral processes of HRI in uncontrolled environments by implementing a dual-level observational approach. The primary contributions of this work include: (a) formalizing a grammar for defining human behavioral patterns, (b) developing a low-specificity behavior coding scheme centered on basic actions to ensure adaptability across diverse real-world contexts, (c) designing an iterative process for refining the coding scheme, (d) providing guidelines for video tagging to facilitate consistent behavioral data extraction, (e) demonstrating the use of a probabilistic sequential model to analyze the relationship between time-series behavioral data and user engagement with robots, and (f) validating the proposed approach in an uncontrolled public environment—a science museum.

Our approach involved an extensive analysis of visitor behavior in interactions with a museum guide robot. We introduced a coding scheme based on a systematic grammar for human behavior, which enabled structured categorization of visitor-robot interactions. This scheme was refined through an iterative review process involving feedback from multiple coder groups. We also proposed detailed guidelines for video tagging to promote consistency in data collection. Further methodological details are provided in the following

Section 3.

3. Behavior Coding Scheme

The development of the behavior coding scheme was divided into two stages: initial identification where the behavior types were classified and predefined, and refinement where the classification and labeling of predefined behaviors were modified. This two-stage approach was adopted to ensure that the behaviors defined in the video tagging process were interpreted objectively and consistently. Specifically, if the definitions of the behaviors in the coding scheme were open to subjective interpretation by the coders during video tagging, maintaining consistency would be challenging. To address this, the development of the behavior coding scheme was divided into two stages: the initial analysis stage and the refinement stage. Separate groups of coders were assigned to each stage to ensure objective and consistent tagging across both phases.

3.1. Initial Identification of Visitor Behaviors

In this stage, two coders reviewed the collected videos and formalized the specific situations and conditions in which behavior types occurred to define the coding scheme. The coding scheme was primarily defined as physical proximity [

17] and interaction attempts [

18].

Andrés

et al. classified the characteristics of interactions based on the types of interactions between humans and robots [

19]. They mentioned that the characteristics of interactions were categorized into interaction level, role in interaction, physical proximity, spatiotemporal context, and level of intervention. The most clearly demonstrated interaction characteristic of the visitors at the RoboLife Museum was the physical proximity. Hence, physical proximity was applied as one of the behavior factors in the coding scheme. Physical proximity indicates the distance at which humans feel a sense of intimacy with others [

17]. The act of humans reducing the distance to a robot can be interpreted as feeling a sense of intimacy. In the collected videos, the visitors exhibited behavior types related to physical proximity, such as approaching, avoiding, and passing by the museum guide robot.

The second behavior factor, interaction attempts, includes the various kinds of behaviors. The visitors who approached the robot closely attempted multiple interactions with the museum guide robot. Their behaviors were categorized into three main types: attempting social interactions such as greeting and gesturing, attempting to obtain information from the screen by touching the robot, and visually observing the robot without attempting interaction.

Table 1 shows some selected video clips and the representative behavior types selected by the two coders. The selected behavior types were confirmed to be classifiable based on the attributes of physical proximity and interaction attempts.

To provide a descriptive definition of visitor behaviors based on selected behavioral types, behavioral grammar was developed as shown in

Table 2. The grammar was designed to express behaviors starting from the point at which a visitor intends to initiate an interaction with a robot. In addition, behavioral definitions were structured to be described based on stimuli and responses, where stimuli refer to specific robot actions (stationary or moving) and responses refer to characteristic behaviors, such as physical proximity and interaction attempts, categorized as primary behavioral factors. Grammar 1 applies to behaviors before an interaction attempt, while Grammar 2 applies to behaviors after an interaction attempt. For instance, using Grammar 1, we can descriptively define behavior as `approaches while looking (a response related to recognizing the robot’s presence) and passes (a response related to distance) when the robot is stationary (stimulus)’. The action of recognizing the robot’s presence, such as gazing or head orientation, was considered synchronous behavior with the distance-related response. Grammar 2 allows us to define behaviors that occur after approaching the robot, that is, after reaching a distance where interaction with the robot is possible. For example, descriptive definitions such as `greets (a response related to social interaction)’ and `touches the screen (a response related to information seeking)’ are possible.

The initial draft of the coding scheme included four behaviors related to physical proximity (Approach, Pass, Avoid, Follow) and three behaviors related to interaction attempts (Touch, Gesture, None) for a total of seven behaviors. In describing the seven behaviors according to Grammars 1 and 2, behaviors that were subject to various subjective interpretations were expressed differently. For example, `approaches’ in Approach was changed to `stops and stands’, and `avoids’ in Avoid was changed to `steps aside’. `Approaches’ implies closing the distance with the robot, connecting to an interaction attempt. However, it is difficult to express with `approach’ the meaning that the behavior related to distance ends to attempt the next interaction, and also difficult to distinguish the visitor’s behavior shown in the video data from `avoid’, `pass’, and `follow’ with `approach’. Therefore, it was modified to a more specific expression, such as `stops and stands’, which conveys the meaning of the end of the behavior.

Although the behaviors of visitors avoiding or passing the robot can be distinguished by the letters `avoid’ and `pass’, they appeared as similar behaviors in the video data. Hence, expressions that clearly distinguish `avoid’ and `pass’ were needed. To this end, we distinguished between the cases where the robot is stationary or moving as stimuli, added temporal concepts such as `passes immediately’, and also added directional concepts such as `steps aside from the path the robot is moving’.

3.2. Refinement of Behavior Coding Scheme

To ensure intercoder reliability, a refinement process was conducted for the coding scheme. Two additional coders were involved in this phase. These coders were tasked with tagging videos using the established coding scheme. Before initiating the video tagging process, they reviewed and revised the descriptive definitions for behaviors. This revision addressed instances that the coders either overlooked during the initial identification of visitor behavior, subject to varied interpretations or were incongruent with the natural context in the representative behavior selection and initial analysis.

Modifications were primarily made to the definitions of interaction initiation. For instance, there were instances where visitors often touched not only the screen but also the robot’s body. Given the robot’s mobility within the museum lobby, determining whether the screen or the body was touched could be challenging due to the video’s angle. Consequently, the definition of Touch was expanded to encompass interactions with the robot’s screen, its body, or both.

Furthermore, observations revealed that children exhibited a wide range of gestures toward the robot. There were various social interaction attempts, such as waving their hands in greeting, shaking their heads as they approached, and raising their arms and bringing them toward the robot’s face. As a result, Gesture was refined to include all forms of interaction attempts, excluding Touch.

Lastly, it was observed that some visitors would approach the robot, halt and remain stationary, but then engage in no further action. Since the interaction attempts are considered to be a series of continuous behaviors with physical proximity, the behavior of None, where no action is taken, was added in the refinement process as a pause. The revised coding scheme is detailed in

Table 3. This includes the seven behaviors of physical proximity and interaction attempts, along with their respective descriptive definitions.

3.3. Video Tagging

The two coders involved in the video tagging completed the refinement process and proceeded to tag the videos based on the refined coding scheme. The tagging focused on the behaviors exhibited by individuals toward the robot, considering that all behaviors are significant only when the visitor acknowledges the presence of the robot. Consequently, five key guidelines were established for the tagging process:

The tagging process is based on the subject’s behavior. All actions become significant once the subject acknowledges the presence of the robot. Therefore, observations begin when the subject’s face is oriented towards the robot.

The behavior code “Pass” was used when a visitor noticed the robot but continued to move past it without halting, determined by observing the direction of the visitor’s head.

If the visitor followed the robot and eventually stopped while looking at the robot, “F-AP” was tagged sequentially. Conversely, if the visitor started to follow the robot but then diverged onto a different path, “F” was tagged.

The behavior code “None” was specifically tagged only for the behavior after either an Approach or Follow action. It was used when no Gesture or Touch occurred after the visitor approached the robot. “None” was also used to denote the absence of interaction or the interval between different interactions.

Continuous occurrences of the same interaction, even if separated by intervals, were considered a single action and tagged as such.

Before starting the video tagging, to accurately identify the behavior of specific individuals across different footage, we documented the external characteristics (age, gender, and clothing) of all visitors shown in the videos, along with the filename of the video in which they appeared. Subsequently, we trimmed the original footage to only include the segments featuring the targeted individual for easier reference in Dartfish Software, a video tagging program.

Through this data preprocessing stage, a total of 290 samples were extracted. To maintain the consistency of the tagging data, the two coders collaboratively tagged the same set of 290 people, rather than dividing the workload between them. The videos were analyzed to display both the physical proximity, and the interaction attempts of all visitors, with the timeline unit set to seconds. Each value was presented in the Interlinear Text format, separated by tabs for clarity. The inter-rater reliability analysis yielded a Cohen’s kappa of 0.8, indicating a substantial level of agreement between the two coders at 84.2% as shown in

Table 4.

4. Observation Results

4.1. Environment

The observation study was conducted at the RoboLife Museum in Pohang, South Korea. The video data about the interactions between visitors and the museum guide robot were collected under the Institutional Review Board approval (Approval number: KIRO-2023-IRB-01). Upon entering the museum, visitors were to confirm their reservation status at the information desk, where they were informed about the purpose of data collection, its use, and security measures. The written consent was obtained from all participants, and especially for children, the written consent was provided by their guardians ensuring full ethical compliance.

The museum guide robot is equipped with a service that allows it to patrol and provide guidance at both the entrance and central lobby. To facilitate this, CCTV cameras capable of monitoring the entire entrance and lobby from all angles were installed. Video data were recorded for approximately 4 hours each day, from 10 A.M. to 6 P.M., aligned with the four scheduled daily exhibition tours. This resulted in a total of 24 hours of collected footage. Data was collected through video recordings of 290 visitors. The coding of the video data followed the behavior coding scheme described in Table

Section 3.

Given that the observations were conducted on an unspecified population of visitors to the RoboLife Museum, demographic analysis was not feasible. Nonetheless, comparisons were made between visually discernible gender groups, and between the adult group and the children and adolescent group.

4.2. Group-Level Behavioral Observation

Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to verify if there were significant differences in the frequency and duration of physical proximity and interaction attempts based on gender and age.

4.2.1. Gender Difference

No significant difference was observed in the duration of maintaining physical proximity between genders (male: M=20.7, S.D.=16.6; female: M=22.9, S.D.=17.9; p-value=0.26), nor did the duration of interaction attempts (male: M=26.6, S.D.=43.3; female: M=21.5, S.D.=43.7; p-value=0.16). There were no significant differences were found in the frequency of physical proximity (male: M=0.097, S.D.=0.118; female: M=0.071, S.D.=0.073; p-value=0.708) and interaction attempts (male: M=0.039, S.D.=0.053; female: M=0.029, S.D.=0.055; p-value=0.067) between genders.

4.2.2. Age Difference

A significant difference was found in the duration of interaction attempts between age groups (U-value=8426.5, p-value=0.0027), with children and adolescents (M=30.2, S.D.=48.8) exhibiting a higher duration than adults (M=17.2, S.D.=34.7). The frequency of interaction attempts also differed significantly between age groups (U-value=8882, p-value=0.021), with children and adolescents (M=0.039, S.D.=0.057) engaging more frequently than adults (M=0.029, S.D.=0.049). However, the duration of physical proximity did not significantly vary (adults: M=21.3, S.D.=14.8; children and adolescents: M=21.9, S.D.=19). No significant difference was also found in the frequency of physical proximity between age groups (adults: M=0.07, S.D.=0.08; children and adolescents: M=0.09, S.D.=0.11).

4.3. Individual-Level Behavioral Observation

In the individual-level behavioral observation, we modeled visitor’s engagement levels using a probabilistic model. It focused on distinguishing the time-series behavioral patterns of museum visitors, categorizing the depth of engagement in their interactions with the museum guide robot. It was conducted by utilizing video data, capturing the interaction between visitors and the museum guide robot.

4.3.1. Model Selection and Data Preprocessing

The HMM is a probabilistic model to deduce patterns and information about hidden states that are not directly observable [

20]. HMM can be employed to discover hidden states using observable variables in time-series data [

21]. Prior research [

22,

23,

24,

25] has successfully applied HMM in analyzing human behavior patterns. The selection of the HMM model is typically determined by the input format: standard HMMs are used for discrete data, Gaussian Hidden Markov Models (GHMMs) for continuous data, and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) for cases that involve both discrete and continuous data. We achieved using a series of observed behavior codes and their durations and frequencies from 290 samples as input variables. In this study, a Gaussian Mixture Hidden Markov Model (GMM-HMM) was developed to infer the engagement levels of individual visitors with the museum guide robot.

The estimation of the hidden state was conducted using three data sources. The variable Duration_Code was defined as the length in seconds during which specific individual behaviors such as Approach, Follow, Avoid, etc. were observed. The variable Frequency_Code was defined as the occurrences of each behavior occurring divided by the entire observation period for each visitor. The variable Code_Encoded was assigned an integer value ranging from 0 to 5 (Approach=0, Avoid=1, Follow=2, Gesture=3, Pass=4, Touch=5), serving as a unique identifier for each distinct behavior representing 6 individual Code in

Table 3. Although the behavior code None can represent a type of pause in the interaction process, it was excluded to minimize ambiguity, simplify transition dynamics, and reduce noise in the engagement analysis. While None in group-level observation provides a comprehensive view of the behavior of different visitor groups including active interaction and pauses, which is important for understanding differences in interaction styles and designing for diverse visitor needs, the HMM model focuses purely on active states allowing for a more straightforward interpretation of the visitor behavior without introducing additional complexity from pauses that can be challenging to interpret in a consistent manner. This simplification helps in achieving actionable insights into how the visitors engaged with the robot and what improvements can be made to sustain or increase engagement levels.

4.3.2. Model Training

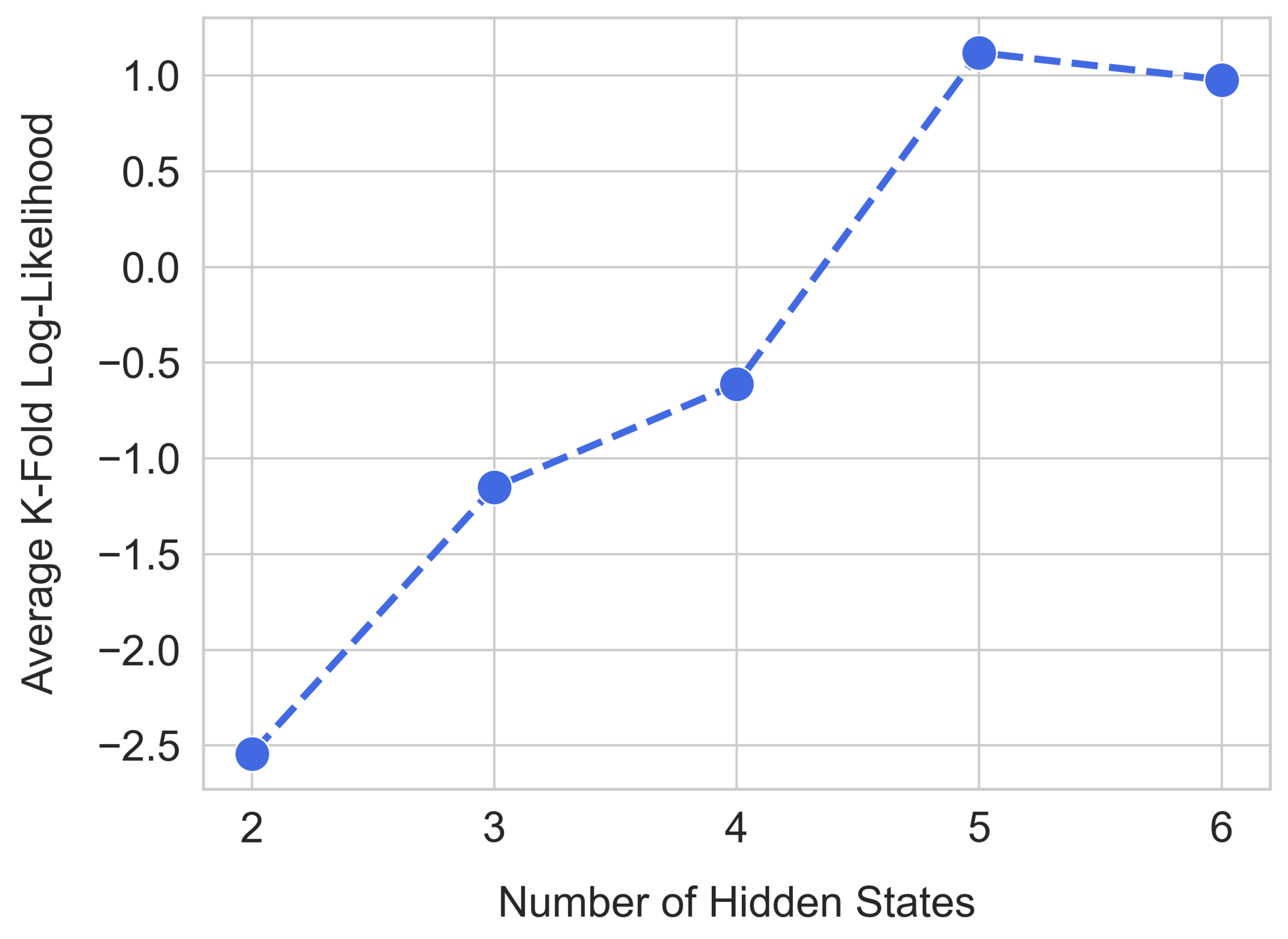

To estimate the parameters of GMM-HMM, we employed K-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal number of hidden states (K=5). The cross-validation procedure identified the optimal model by selecting the one with the highest average log-likelihood across folds, thereby ensuring that the model could generalize effectively to unseen data. As depicted in

Figure 1, the optimal number of hidden states was selected to be 5. This approach allowed the model to effectively capture the variability inherent in user behaviors. Emissions from each hidden state were modeled as a combination of several Gaussian distributions, providing a flexible representation capable of accounting for the diverse interaction patterns observed.

The model parameters were refined iteratively using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. These parameters included the initial state probabilities, transition probabilities between hidden states, and GMM-HMM parameters for emissions. The training process was set to

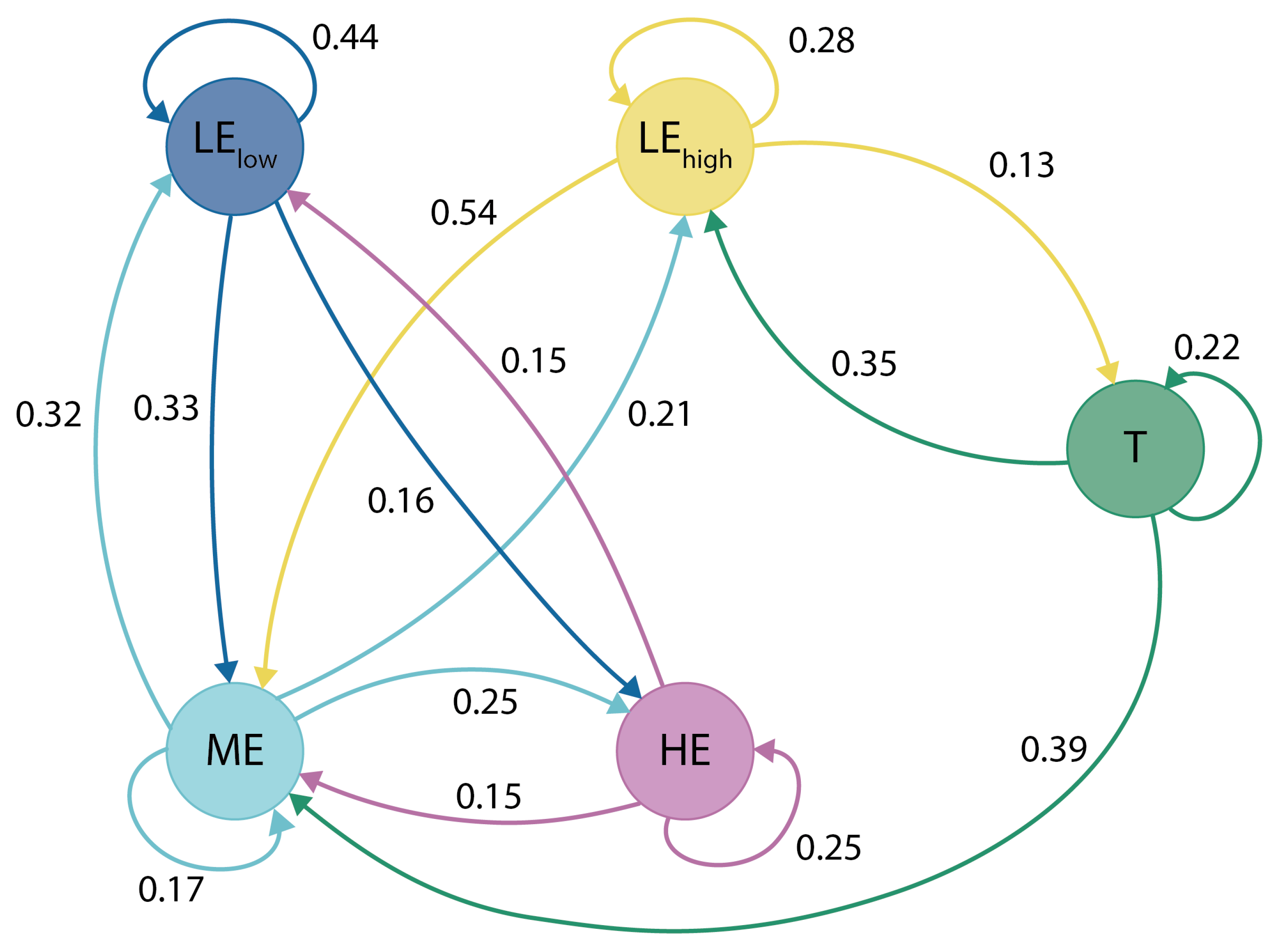

n_iteration=100, and the dataset was split into an 8:2 ratio for the train and test sets. The model training converged after several iterations as the log-likelihood values stabilized, indicating that the model had effectively learned the underlying patterns in the data. The final model produced a transition matrix with probabilities that reflected the likelihood of users transitioning between different hidden states as shown in

Figure 2. The optimal number of hidden states was determined based on the highest average log-likelihood achieved during cross-validation, and the final model used these hidden states to classify user behaviors. The observation distributions and state transition dynamics were then further analyzed to understand user interaction patterns.

4.3.3. Model Interpretation

The results provide valuable insights into the different levels of visitor’s engagement during interactions with the robot. The transition diagram in

Figure 3 allows us to better understand the behaviors associated with each of the five hidden states. Each state represents a distinct level of engagement, ranging from initial exploration to more focused interactions. The state transitions illustrate how the visitors move between these phases, highlighting typical paths in their engagement.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of observed behaviors. The

x-axis delineates the distribution intervals, and the

y-axis quantifies the frequency of data points within each interval. For instance, the Duration_Code in

shows that most behaviors lasted between 0 and 10 seconds. Similarly, the Frequency_Code primarily falls within the 0 to 0.05 range. In terms of behavior types (Code_Encoded), Touch (coded as 5) was the most frequent, significantly outnumbering Gesture (coded as 3), which occurred less than 50 times.

The five hidden states identified by the HMM can be grouped into three categories of engagement. Low Engagement (LE) includes and , where the visitors either initiate brief interactions or fluctuate between minimal and exploratory activities, showing little commitment. Moderate Engagement (ME) represented that the visitors are more involved, actively exploring the robot and repeating actions to understand its features, but without fully committing to deep engagement. Finally, High Engagement (HE) means that the visitors demonstrate focused and sustained interaction, spending significant time on specific tasks that require attention. This grouping highlights the progression from initial, exploratory interactions to highly immersive and focused engagement, indicating the phases the visitors typically go through as they deepen their interaction with the robot.

represents a brief exploration. The visitors entering this state exhibit minimal interaction, as seen from the short durations and very low frequency of actions. The Code_Encoded values show that only a few specific types of interactions are repeated, indicating that the visitors likely enter this state when they are just beginning to explore or are hesitant to engage deeply. The transition probabilities show that the visitors in often move to or occasionally back to ME, suggesting a pattern of oscillating between exploratory behavior and more engagement.

represents a mixed engagement with a broad range of interaction characteristics. It includes the visitors who spend varying amounts of time interacting, as indicated by Duration_Code, and engage with the robot at moderate frequencies. The Code_Encoded distribution shows a few dominant values, indicating that the visitors in tend to focus on certain types of actions. The transition matrix reveals that the visitors in often return to or self-transition, suggesting that is somewhat unstable, with the visitors either continuing with mixed activities or dropping back to lower engagement.

T serves as a transitionary phase, where the visitors move between different types of engagement behaviors. The observation distributions for T show short durations of engagement, combined with a wide range of interaction types, implying that the visitors in this state are not entirely settled in their interaction patterns. Instead, they are transitioning to test different features without spending much time on any specific one. The transition diagram reveals that the visitors in T frequently move to or advance to HE, the latter indicating a potential progression toward more focused engagement.

ME represents moderate exploration, characterized by the visitors engaging with the robot for a longer time compared to . This is reflected in broader distributions for Duration_Code and higher interaction frequencies. In this state, the visitors are actively exploring the robot’s functionalities, likely performing repeated actions to understand them. The transition diagram indicates that the visitors in ME can move towards if they lose interest, or progress to T, which acts as an intermediary. This suggests that ME serves as a temporary engagement level, where the visitors decide whether to progress to deeper levels of interaction or return to less active states.

HE is a state of focused interaction. The visitors in HE exhibit long engagement durations, suggesting they are deeply involved in specific activities. Unlike the other states, Frequency_Code in HE shows lower interaction frequencies, indicating that the visitors are not repeating the same actions frequently. Instead, they appear to be spending more time on individual tasks that require attention or effort. This state represents a high level of engagement, and the fact that the visitors tend to stay in this state longer, as indicated by the moderate self-transition probability, suggests they find value in these interactions. However, the visitors can also transition to , showing that after the focused engagement, they might move back to mixed activity levels.

4.4. A Guide to Observation Studies Using Our Approach

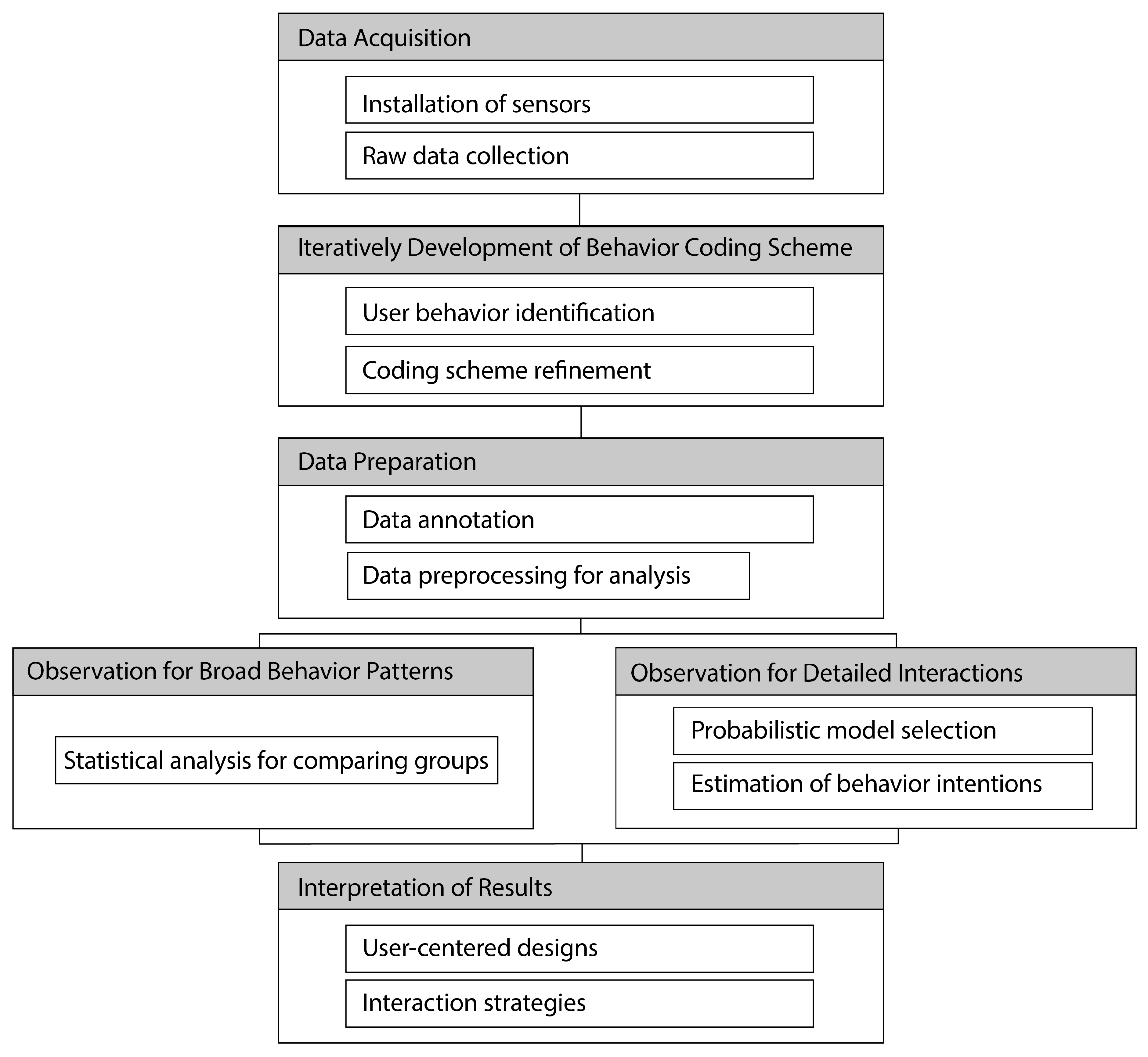

We suggest a guideline for conducting observation studies in HRI using our observational approach as illustrated in

Figure 5.

4.4.1. Development of Behavior Coding Scheme

The development of the coding scheme follows a two-stage process. Initially, researchers define a preliminary set of behavior categories informed by observing collected data. Afterward, new interaction patterns may be identified, or the definitions of existing behaviors may require modification, prompting revisions to the coding categories. This iterative refinement process ensures that the coding scheme evolves to remain relevant and accurately reflects the observed behaviors. A detailed account of the process for developing the behavior coding scheme is provided in

Figure 5.

4.4.2. Group-Level Observation for Broad Behavior Patterns

Group-level observation is focused on capturing broad behavioral patterns across large groups or populations. It emphasizes the frequency, duration, and proximity of interactions with robots or other stimuli. This approach is beneficial when studying group-level trends or analyzing differences across demographic variables.

To implement group-level observation effectively, researchers begin by employing video surveillance using wide-angle cameras or CCTV systems to record interactions across large environments. This setup facilitates the observation of broad behavioral trends such as how visitors approach or avoid robots. By capturing a comprehensive view of the environment, researchers can gather valuable data on interaction patterns within a diverse population.

Next, researchers apply the behavior coding scheme to categorize general actions, including approaching, avoiding, or interacting with the robot, and then conduct statistical analyses such as t-tests or ANOVA to identify significant differences in behaviors across demographic groups, including factors like age, gender, or other relevant categories. These statistical methods are well-suited for quantifying broad interaction trends and comparing behavioral responses across different population segments, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of group-level engagement dynamics.

4.4.3. Individual-Level Observation for Detailed Interaction Dynamics

Individual-level observation offers a detailed lens for capturing the moment-by-moment dynamics of HRI. This approach focuses on subtle behaviors such as gestures, gaze shifts, and specific physical or verbal responses directed toward the robot. By analyzing these nuanced aspects of interaction, researchers can gain deeper insights into comprehensive interaction processes.

A key strength of this method lies in its use of time-series data to represent behavioral sequences. The process begins with the precise coding of observed behaviors, which are then converted into temporal data streams. This enables the systematic tracking of interaction dynamics over time, capturing shifts in engagement levels and transitions between distinct interaction states.

In this study, we employed a HMM to analyze temporal engagement trajectories. HMM was particularly well-suited to our context, as it captures latent engagement states and models the probabilistic transitions between them over time. This allowed us to identify meaningful patterns in user behavior that would have been difficult to detect using static or frequency-based methods.

However, it is important to note that the choice of temporal model should be guided by the nature of the data and the research goals. While HMM proved advantageous for modeling sequential engagement states in our study, alternative models—such as Conditional Random Fields, Dynamic Bayesian Networks or deep learning-based temporal models may be more appropriate in other contexts.

Ultimately, the use of temporal modeling in individual-level observation enhances our ability to understand how engagement evolves, identify key turning points in interaction, and inform the design of adaptive systems. This approach contributes to more responsive and personalized robot behaviors, fostering richer and more effective HRIs in real-world environments.

5. Discussion

This study offers meaningful insights into HRI in a real-world setting, focusing on spontaneous interactions between visitors and a museum guide robot. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of a dual-level observational approach—combining group-level and individual-level analyses—for capturing both overall behavioral trends and dynamic engagement processes.

The results have several implications for the design and implementation of service robots in public spaces. Key themes include the importance of behavior-driven, user-centered design; the value of adaptive interaction strategies; and the utility of time-based engagement modeling for supporting long-term interaction.

5.1. Behavior-Driven, User-Centered Design

Group-level analysis revealed that children and adolescents engaged more frequently and intensely with the robot compared to adults. This aligns with prior research showing higher responsiveness among younger users to interactive technologies [

26,

27,

28]. In contrast, gender was not found to significantly influence interaction frequency or duration [

29,

30], suggesting that age is a more salient factor in designing adaptive interaction strategies.

These findings underscore the importance of user-centered design principles grounded in actual behavioral patterns. For younger users, playful and exploratory interaction elements may enhance engagement [

31,

32], while adults may prefer more functional and task-oriented interfaces [

33]. This observation aligns with the theory of selective optimization with compensation, which suggests that older users prioritize technologies that enhance everyday functionality.

To increase inclusivity and engagement, robot behaviors should be tailored to demographic and situational characteristics. Flexible interfaces and modular interaction modes can help ensure that service robots remain accessible and engaging for a wide range of users in public environments.

5.2. Adaptive, Dynamic Interaction Strategies

Through the use of a HMM, this study identified three distinct engagement states—low, moderate, and high—capturing the dynamic nature of user interaction. Visitors categorized as

HE showed more sustained and complex engagement behaviors, consistent with research linking prolonged interaction to increased curiosity and attention [

34].

These findings emphasize the need for robots to adopt real-time adaptive strategies. For users in

LE states, simple prompts such as greetings or visual stimuli could initiate engagement. In contrast,

HE users may benefit from content-rich experiences like storytelling, games, or interactive tasks [

35,

36]. Tailoring interactions in this way can optimize user experience and maintain engagement over time.

5.3. Utility of Time-Based Engagement Modeling

This study highlights the value of time-based engagement modeling for understanding and supporting user interaction in real-world HRI contexts. By converting behavioral codes into time-series data, we were able to analyze not only the frequency of behaviors but also the transitions between engagement states and the duration of each state. This temporal perspective allows engagement to be treated as a dynamic, context-sensitive process rather than a fixed or binary outcome.

Such an approach provides a meaningful foundation for designing robots that can adapt to the ebb and flow of user behavior in real time. Integrating temporal modeling with intelligent sensing technologies could lead to the development of socially responsive robots capable of recognizing patterns, predicting disengagement, and modifying their behavior to sustain meaningful interaction.

Importantly, this dynamic modeling also offers practical implications for long-term engagement. In public environments such as museums—where users may interact with the same robot across multiple visits—robots equipped with memory and adaptive mechanisms can foster familiarity and build user trust over time [

37,

38]. Our findings, particularly the transitions from

LE to

HE, suggest that repeated positive experiences can deepen user-robot relationships. Gradually increasing interaction complexity and personalization can help sustain interest and promote continued engagement [

39].

These insights extend beyond the museum context and are relevant to other domains such as healthcare, education, and customer service—settings where long-term engagement and trust are vital for effective and meaningful HRI.

5.4. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into HRI within a real-world public setting, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, although the proposed approach effectively categorized visitor engagement into three levels, it did not investigate how these engagement states could be leveraged to inform real-time robot behavior. As a result, the findings remain limited to post-hoc analysis and do not yet support adaptive interactions during live deployments. Future research should explore mechanisms for detecting engagement states in real time and dynamically adjusting robot behaviors to enhance user experience.

Second, the present study focused exclusively on short-term, single-session interactions, without examining how engagement may evolve over repeated encounters. Understanding long-term engagement trajectories is essential for designing robots that can foster sustained interest, trust, and acceptance—particularly in public environments where recurring user contact is common.

Third, the analysis was limited to age and gender as demographic variables. While these factors are relevant, a more inclusive approach would incorporate additional characteristics such as cultural background, educational attainment, prior experience with technology, and cognitive or physical diversity. Expanding the demographic scope would improve the generalizability of the findings and support broader applications in other domains, including healthcare, retail, and public services.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we proposed an observational approach to analyze HRI in real-world public environments, with a specific focus on a science museum setting. By combining group-level and individual-level behavioral observation methods, our approach captured both broad behavioral trends and subtle interactional nuances in visitor interactions with a museum guide robot. The group-level analysis revealed demographic differences, showing that children and adolescents engaged more actively than adults. At the individual level, we applied a GMM-HMM model to classify visitor engagement into three distinct levels, enabling a dynamic view of how engagement evolves over time. This dual-level approach provided valuable insights into interaction dynamics and informed practical design guidelines for optimizing HRI in complex public environments.

Building on these findings, several promising directions for future research emerge. First, long-term engagement patterns—particularly for repeat or returning users—should be explored to understand how sustained interaction can influence user experience and robot effectiveness in public settings. Second, incorporating affective and physiological data using non-intrusive biometric sensing—such as gaze tracking, facial expression analysis, posture estimation, or audio-based crowd response detection—could deepen our understanding of both individual and group-level engagement. These multimodal signals can reveal internal and collective emotional states that are difficult to observe through behavioral cues alone, enabling more adaptive and context-aware HRI in public environments. Finally, given the substantial time and labor required for manual observational studies, future work should explore the use of artificial intelligence to assist in automating behavioral annotation and pattern recognition, thereby enhancing the efficiency and real-world applicability of observational research.

Author Contributions

All authors worked on conceptualizing the observation research framework for human-robot interaction. H.Y. and G.S. were responsible for methodology, investigation, visualization, project administration, and the original draft. H.L. was involved in the software implementation and testing. M.-G.K. and S.K. served as the principal investigator for the study and revised the original manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Information and Communications Technology Planning and Evaluation (IITP) Grant funded by the Korean Government through MSIT (Development of AI Technology for Early Screening of Infant/Child Autism Spectrum Disorders Based on Cognition of the Psychological Behavior and Response) under Grant RS-2019-II190330. This work was also equally supported by the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) Grant funded by the Korean Government through MOTIE (Development of Behavior-Oriented HRI AI Technology for Long-Term Interaction between Service Robots and Users) under Grant 20023495.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Institute of Robotics and Technology Convergence (KIRO-2023-IRB-01) on 29 March 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Anguera, M.T. Possibilities and relevance of systematic observation by the psychology professional. Pap. Psicól. 2010, 31, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- S. L. Godwin, E. Chambers IV, Observational research: A tool for collecting behavioral data and validating surveys. In Proceedings of the Summer Programme in Sensory Evaluation; 2009; pp. 29–36.

- P. R. Rosenbaum, Observational Study: Definition and Examples, Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 2014.

- F. Babel, J. Kraus, M. Baumann, Findings from a qualitative field study with an autonomous robot in public: exploration of user reactions and conflicts. International Journal of Social Robotics, 2022; 14, 1625–1655.

- L. D. Daczo, L. Kalova, K. L. F. Bonita, M. D. Lopez, M. Rehm, Interaction initiation with a museum guide robot—from the lab into the field. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT); 2021; pp. 438–447.

- M. Shiomi, T. M. Shiomi, T. Kanda, H. Ishiguro, N. Hagita, A larger audience, please!—Encouraging people to listen to a guide robot, pp. 31–38, 2010. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI).

- L. Rettinger, A. Fürst, E. Kupka-Klepsch, K. Mühlhauser, E. Haslinger-Baumann, F. Werner, Observing the interaction between a socially-assistive robot and residents in a nursing home. International Journal of Social Robotics 2024, 16, 403–413. [CrossRef]

- M. Heerink, B. M. Heerink, B. Kröse, V. Evers, B. Wielinga, Assessing acceptance of assistive social agent technology by older adults: the almere mode. International Journal of Social Robotics 2010, 2, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Wansink, Conducting useful observational research to improve behavior, Context: The Effects of Environment on Product Design and Evaluation, forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- M. Sasaki, H. Mishima, K. Suzuki, M. Ohkura, Observations on micro-exploration in everyday activities, In Studies in Perception and Action III, (Routledge, ed. 1, 1995), pp. 99–102.

- E. B. Smith, W. E. B. Smith, W. Rand, Simulating macro-level effects from micro-level observations. Management Science 2018, 64, 5405–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Oliveira, P. Arriaga, A. Paiva, Human-robot interaction in groups: Methodological and research practices, Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 5, 59, 2021. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2021, 5, 59.

- S. Matsumoto, A. S. Matsumoto, A. Washburn, L. D. Riek, A framework to explore proximate human-robot coordination, ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction, 11, 1–34, 2022.

- J. J. Lee, G. Ajaykumar, I. Shpitser, C. M. An Introduction to causal inference methods for observational human-robot interaction research, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Boos, O. Herzog, J. Reinhardt, K. Bengler, M. Zimmermann, A compliance–reactance framework for evaluating human-robot interaction. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2022, 9, 733504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Kim, M. Hirokawa, S. Matsuda, A. Funahashi, K. Suzuki, Smiles as a signal of prosocial behaviors toward the robot in the therapeutic setting for children with autism spectrum disorder, Frontiers in Robotics and AI. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8, 599755. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Hall, Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2010, 54, 48–57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Fischer, S. Yang, B. Mok, R. Maheshwari, D. Sirkin, W. Ju, Initiating interactions and negotiating approach: a robotic trash can in the field, In 2015 AAAI Spring Symposium Series, 2015.

- A. Andrés, D. E. Pardo, M. Díaz, C. Angulo, New instrumentation for human robot interaction assessment based on observational methods. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart Environments, 2015; 7, 397–413.

- L. Rabiner, B. Juang, An introduction to hidden Markov models. IEEE ASSP Magazine, 1986; 3, 4–16.

- A. Panuccio, M. A. Panuccio, M. Bicego, V. Murino, A hidden Markov model-based approach to sequential data clustering, pp. 734–743. In Proceedings of the Structural, Syntactic, and Statistical Pattern Recognition: Joint IAPR International Workshops SSPR 2002 and SPR 2002.

- V. G. Sánchez, O. M. Lysaker, N. O. Skeie, Human behaviour modelling for welfare technology using hidden Markov models. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 137, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- H. Le, J. E. Hoch, O. Ossmy, K. E. Adolph, X. Fern, A. Fern, Modeling infant free play using hidden Markov models, pp. 1–6. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL, 2021).

- D. Gupta, M. Gupta, S. Bhatt, A. S. Tosun, Detecting anomalous user behavior in remote patient monitoring, pp. 33–40. In In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI, 2021).

- X. Cheng, B. Huang, CSI-based human continuous activity recognition using GMM–HMM. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 18709–18717. [CrossRef]

- T. Flanagan, G. Wong, T. Kushnir, The minds of machines: Children’s beliefs about the experiences, thoughts, and morals of familiar interactive technologies. Developmental Psychology 2023, 59, 1017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. L. Lewis, L. K. Kervin, I. Verenikina, S. J. Howard, Young children’s at-home digital experiences and interactions: An ethnographic study. Frontiers in Education, 2024; 9, 1392379.

- A. Suryani, S. Soedarso, K. Nisa, F. Z. Z. Hamdan, Revisiting young children’s technological learning behavior within a microsystem context for development of the next generation. Journal of Development Research 2023, 7, 283–298.

- S. A. Olatunji, W. A. S. A. Olatunji, W. A. Rogers, Development of a design framework to support pleasurable robot interactions for older adults, 13th World Conference of Gerontechnology (Gerontechnology), Daegu, South Korea, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Wróbel, K. A. Wróbel, K. Źróbek, M. M. Schaper, P. Zguda, B. Indurkhya, Age-appropriate robot design: in-the-wild child-robot interaction studies of perseverance styles and robot’s unexpected behavior, pp. 1451–1458. In Proceedings of the 32nd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN, 2023).

- J. Xie, Research on interactive children’s teaching mode driven by artificial intelligence technology. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2023, 20, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- A. Neerincx, D. Veldhuis, J. M. Masthoff, M. M. de Graaf, Co-designing a social robot for child health care. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 2023, 38, 100615. [CrossRef]

- L. Chu, H. W. Chen, P. Y. Cheng, P. Ho, I. T. Weng, P. L. Yang, S. E. Chien, Y. C. Tu, C. C. Yang, T. M. Wang, H. H. Fung, Identifying features that enhance older adults’ acceptance of robots: a mixed methods study. Gerontology 2019, 65, 441–450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Sakaguchi, Y. Okafuji, K. Matsumura, J. Baba, J. Nakanishi, An estimation framework for passerby engagement interacting with social robots. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Finkel, N. C. Krämer, The robot that adapts too much? An experimental study on users’ perceptions of social robots’ behavioral and persona changes between interactions with different users. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2023, 1, 100018. [CrossRef]

- K. Inoue, D. Lala, K. Yamamoto, K. Takanashi, T. Kawahara, Engagement-based adaptive behaviors for laboratory guide in human-robot dialogue, In Increasing Naturalness and Flexibility in Spoken Dialogue Interaction: 10th International Workshop on Spoken Dialogue Systems (IWSDS, 2021), pp. 129–139.

- B. Matcovich, C. B. Matcovich, C. Gena, F. Vernero, How the personality and memory of a robot can influence user modeling in human-robot interaction, In Adjunct Proceedings of the 32nd ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization (UMAP, 2024), pp. 136–141.

- M. Maroto-Gómez, S. M. M. Maroto-Gómez, S. M. Villarroya, M. Malfaz, Á. Castro-González, J. C. Castillo, M. Á. Salichs, A preference learning system for the autonomous selection and personalization of entertainment activities during human-robot interaction, pp. 343–348. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL, 2022).

- D. Ghiglino, S. Marchesi, A. Wykowska, Play with me: complexity of human-robot interaction affects individuals’ variability in intentionality attribution towards robots. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Schrum, M. Ghuy, E. Hedlund-Botti, M. Natarajan, M. Johnson, M. C. Gombolay, Concerning Trends in Likert Scale Usage in Human-Robot Interaction: Towards Improving Best Practices. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 2023, 12, 1–32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).