Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Research Design

Data Collection and Analysis

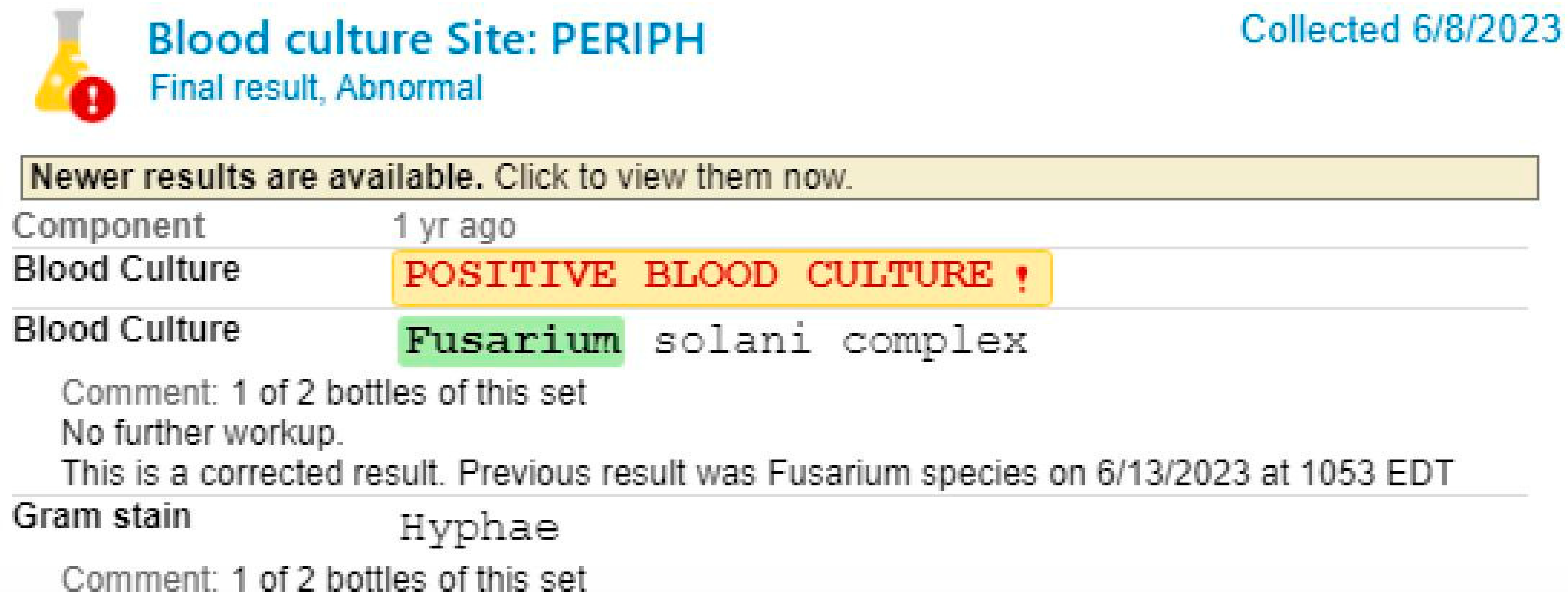

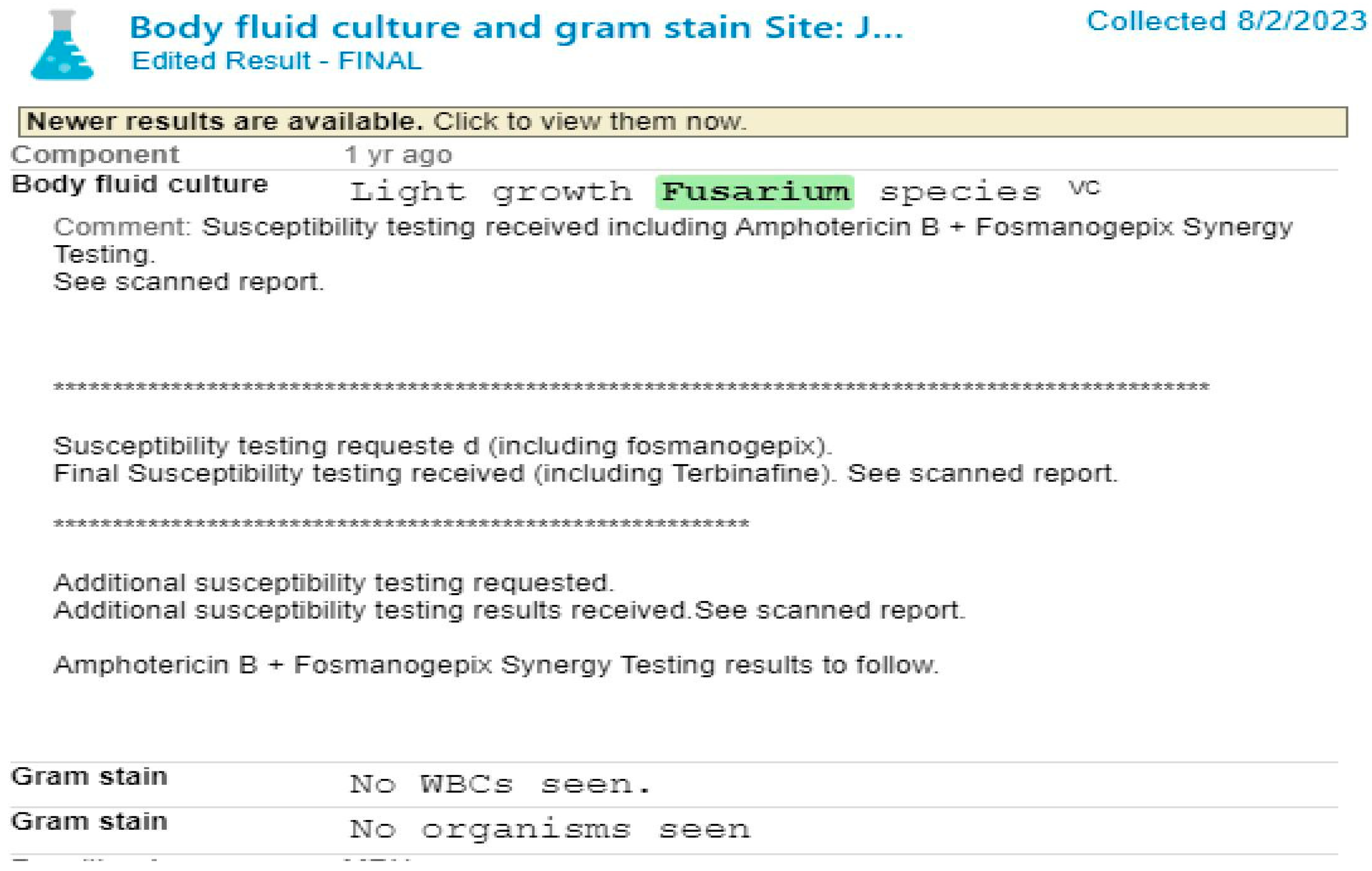

Case Presentation

Discussion

Fusariosis in Immunocompromised Hosts

Diagnostic Challenges and Imaging Findings

Management and Treatment Considerations

Clinical Implications and Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgment

Informed Consent

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Y. Sugiura et al., “Physiological characteristics and mycotoxins of human clinical isolates of Fusarium species,” Mycol. Res., vol. 103, no. 11, pp. 1462–1468, Nov. 1999. [CrossRef]

- L. Huang et al., “Disseminated Fusarium solani infection in a child with acute lymphocytic leukemia: A case report and literature review,” Med. Microecol., vol. 18, p. 100093, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Demonchy et al., “Multicenter Retrospective Study of Invasive Fusariosis in Intensive Care Units, France,” Emerg. Infect. Dis., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 215–224, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Empiric Amphotericin B Therapy in Patients with Acute Leukemia | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic.” Accessed: Mar. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article-abstract/7/5/619/471480?redirectedFrom=PDF.

- C. Alarcón-Payer, M. D. M. Sánchez Suárez, A. Martín Roldán, J. M. Puerta Puerta, and A. Jiménez Morales, “Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms and Biomarkers on the Effectiveness and Toxicity of Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Acute Myeloid Leukemia,” J. Pers. Med., vol. 12, no. 10, p. 1607, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Acute Leukemia Clinical Presentation | IntechOpen.” Accessed: Mar. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/44629.

- E. I. Boutati and E. J. Anaissie, “Fusarium, a Significant Emerging Pathogen in Patients With Hematologic Malignancy: Ten Years’ Experience at a Cancer Center and Implications for Management,” Blood, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 999–1008, Aug. 1997. [CrossRef]

- R. Galimberti, A. C. Torre, M. C. Baztán, and F. Rodriguez-Chiappetta, “Emerging systemic fungal infections,” Clin. Dermatol., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 633–650, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Gamis, T. Gudnason, G. S. Giebink, and N. K. Ramsay, “Disseminated infection with Fusarium in recipients of bone marrow transplants,” Rev. Infect. Dis., vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1077–1088, 1991. [CrossRef]

- V. Letscher-Bru, F. Campos, J. Waller, R. Randriamahazaka, E. Candolfi, and R. Herbrecht, “Successful outcome of treatment of a disseminated infection due to Fusarium dimerum in a leukemia patient,” J. Clin. Microbiol., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 1100–1102, Mar. 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Fei et al., “Disseminated fusarium infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after CART: A case report,” Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 101, no. 45, p. e31594, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Letscher-Bru, F. Campos, J. Waller, R. Randriamahazaka, E. Candolfi, and R. Herbrecht, “Successful outcome of treatment of a disseminated infection due to Fusarium dimerum in a leukemia patient,” J. Clin. Microbiol., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 1100–1102, Mar. 2002. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).