Submitted:

20 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

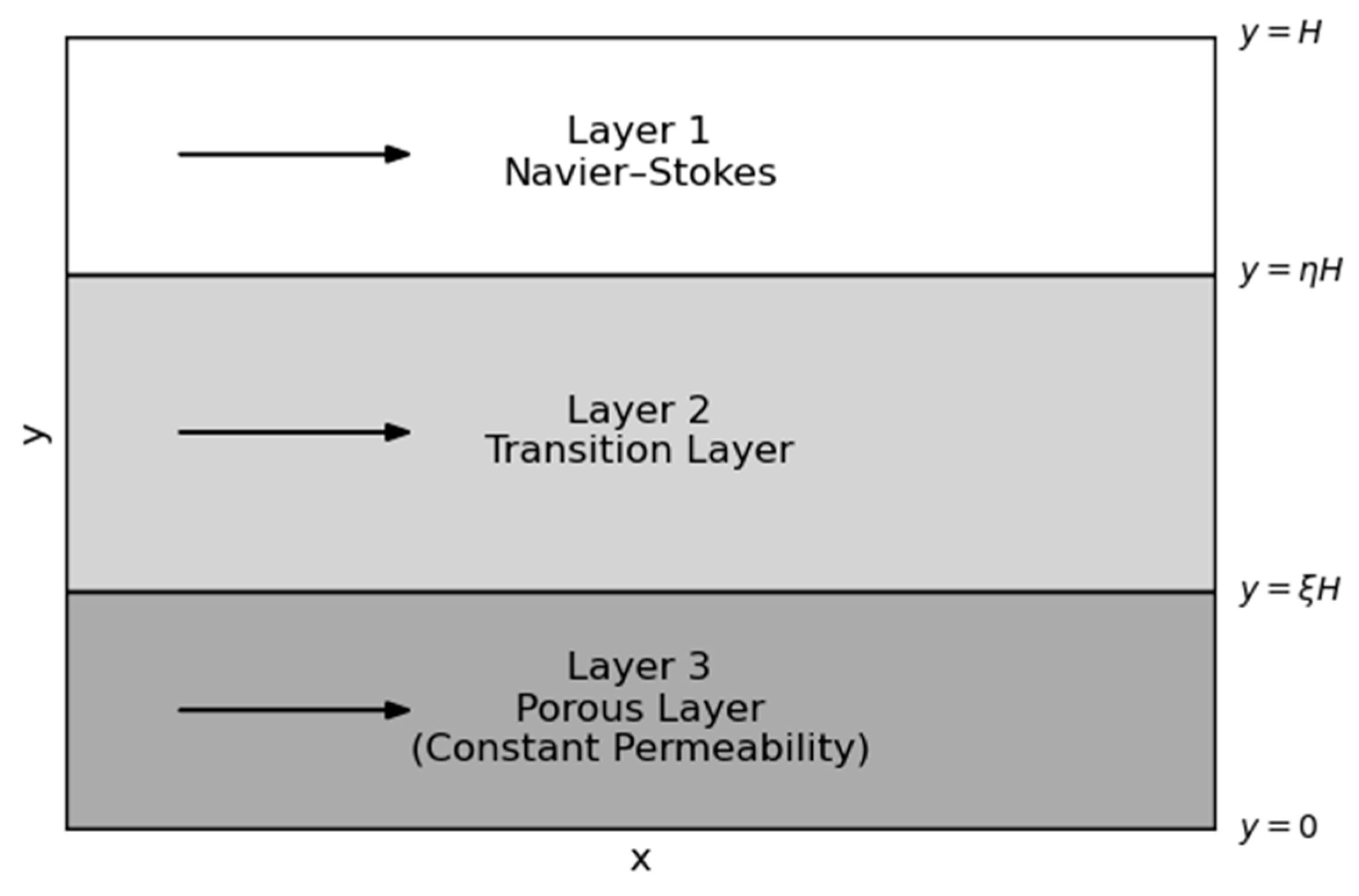

2. Problem Formulation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Permeability Distributions

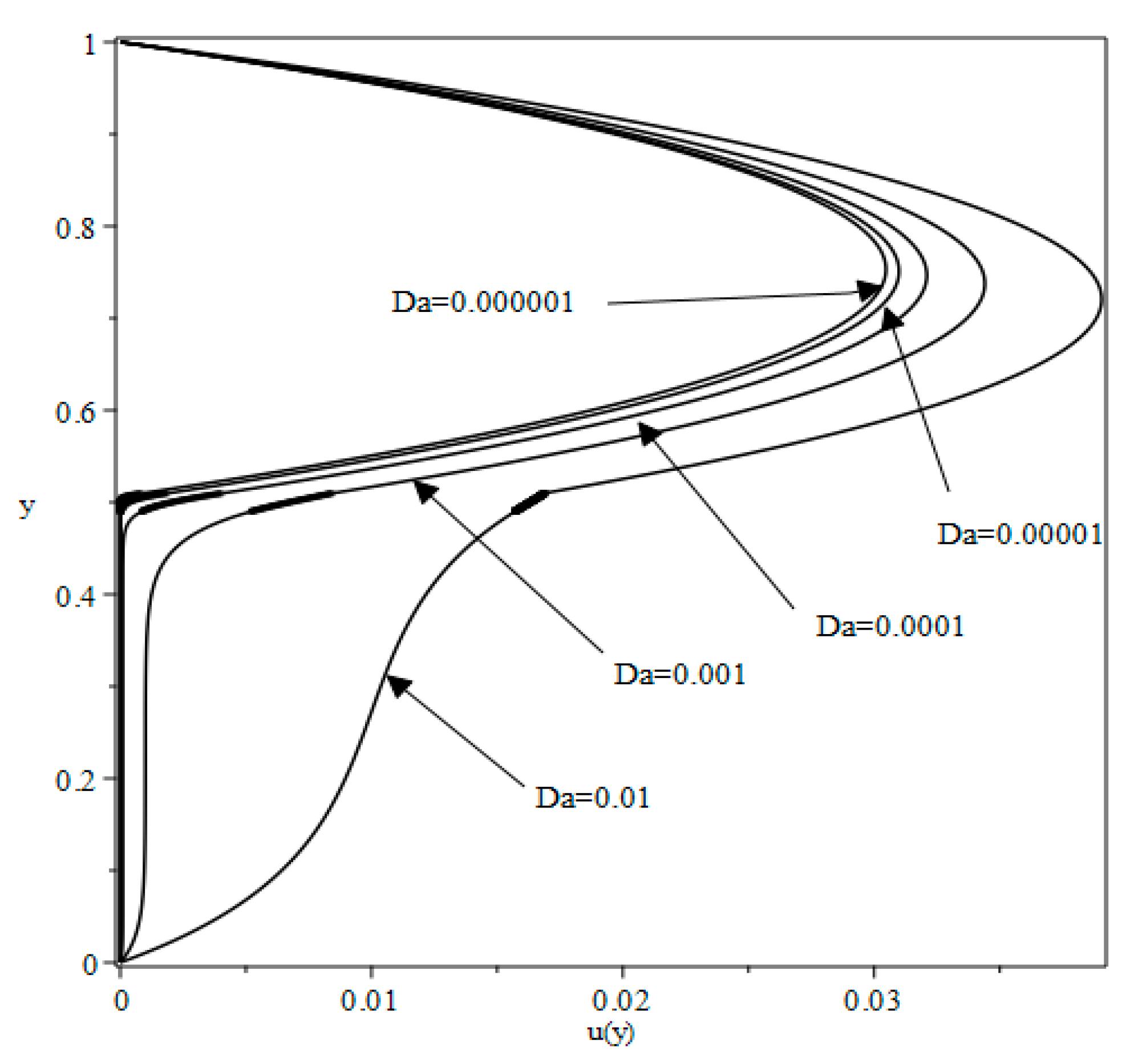

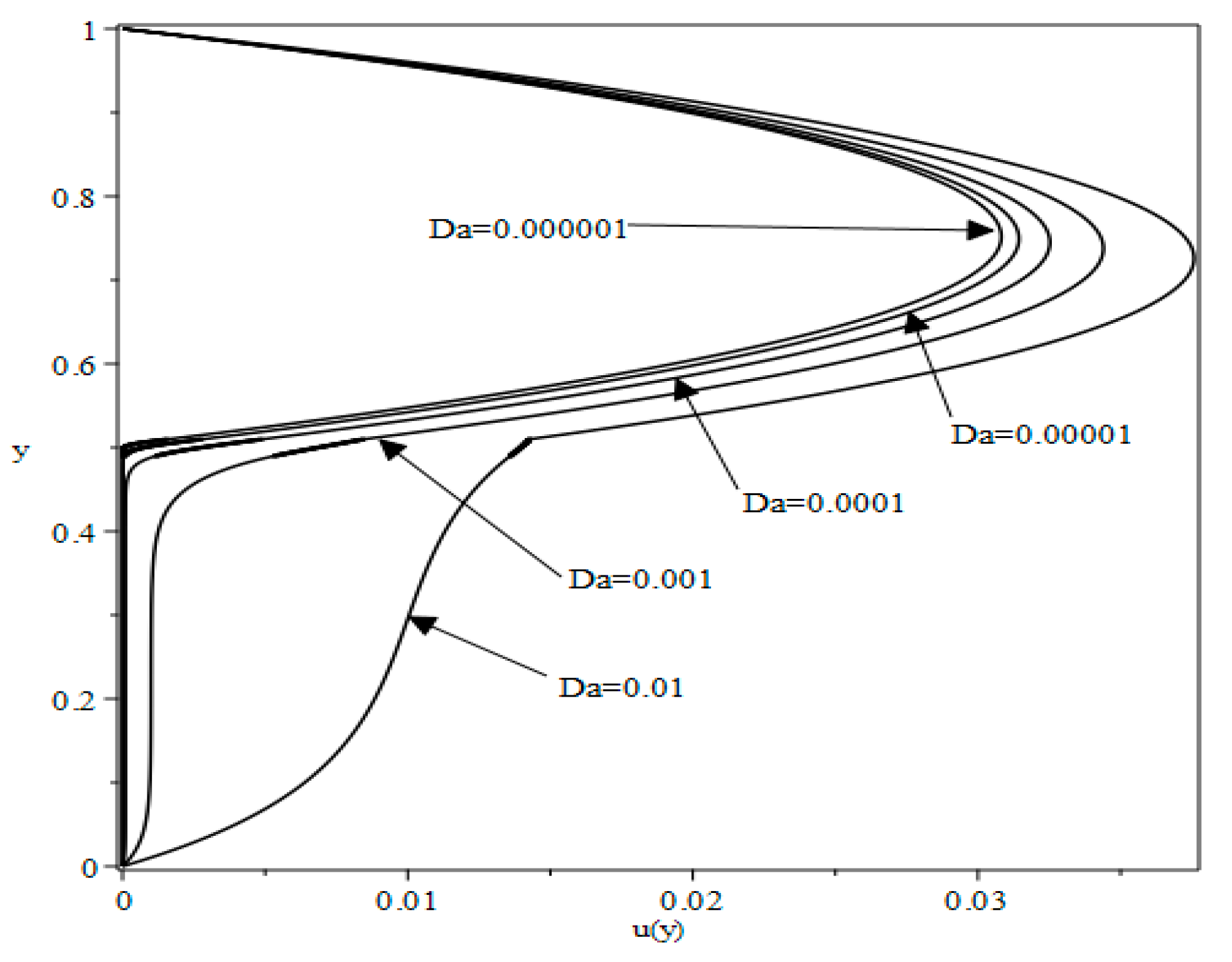

3.2. Velocity Profiles

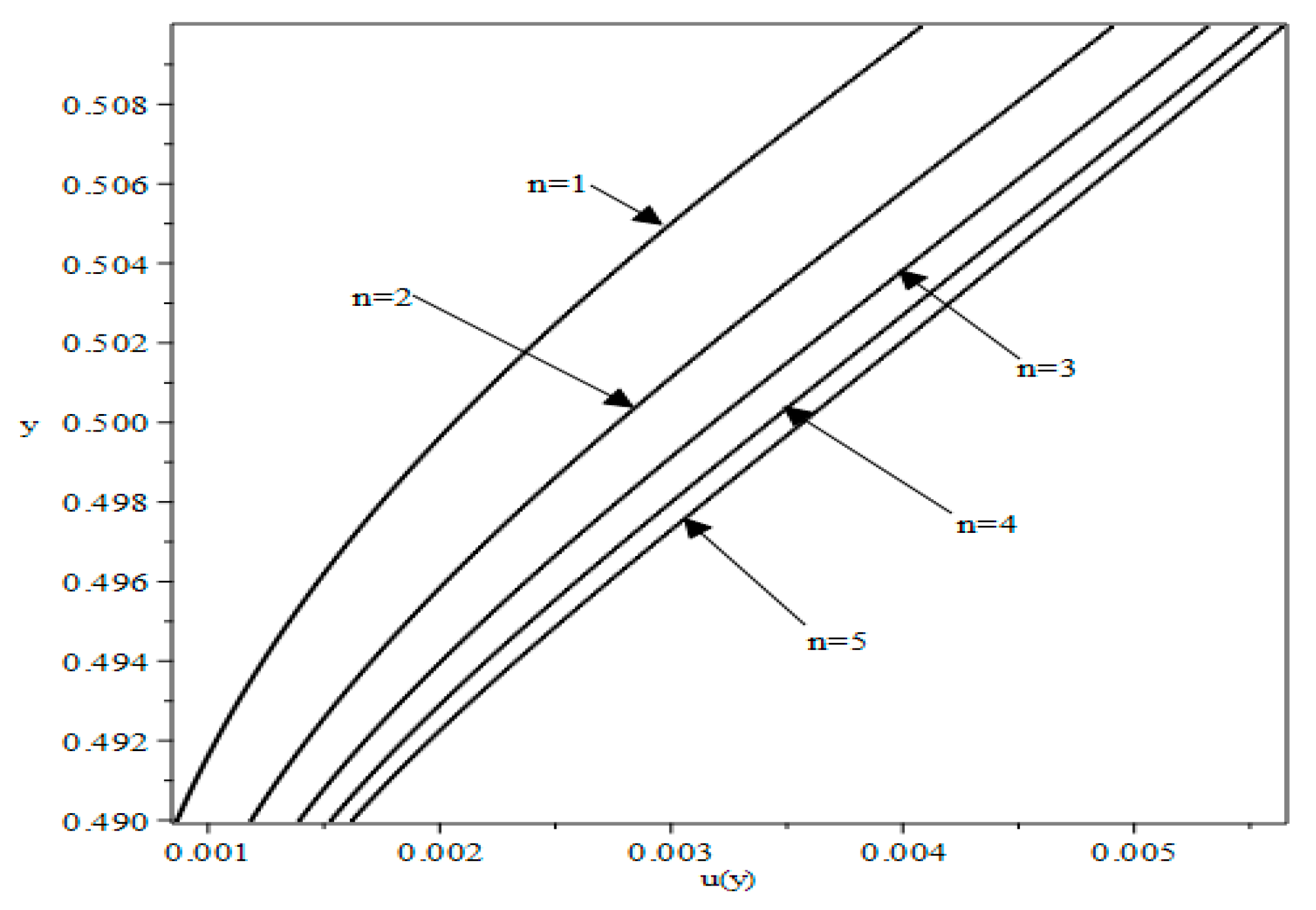

3.3. Velocity at the Interfaces

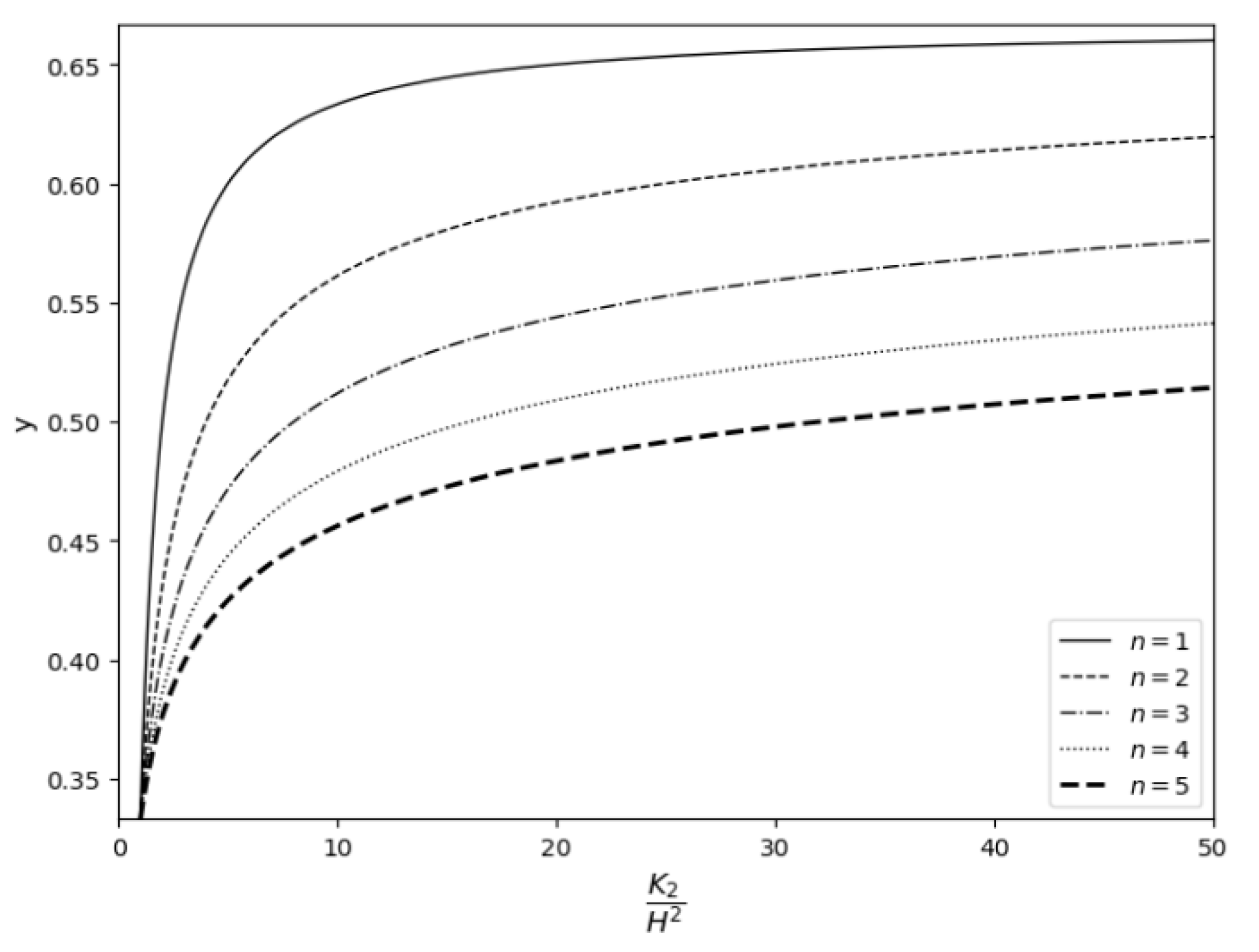

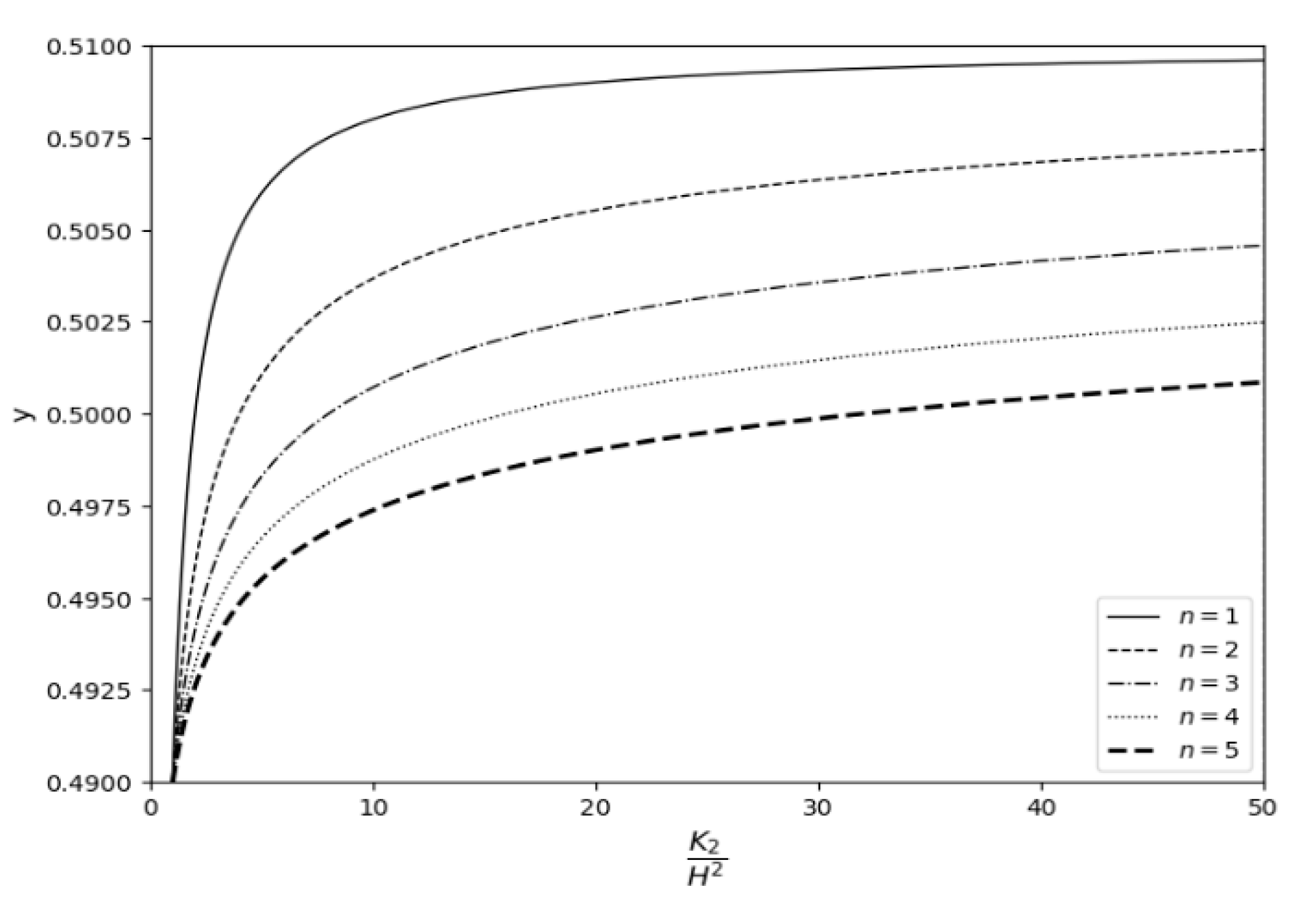

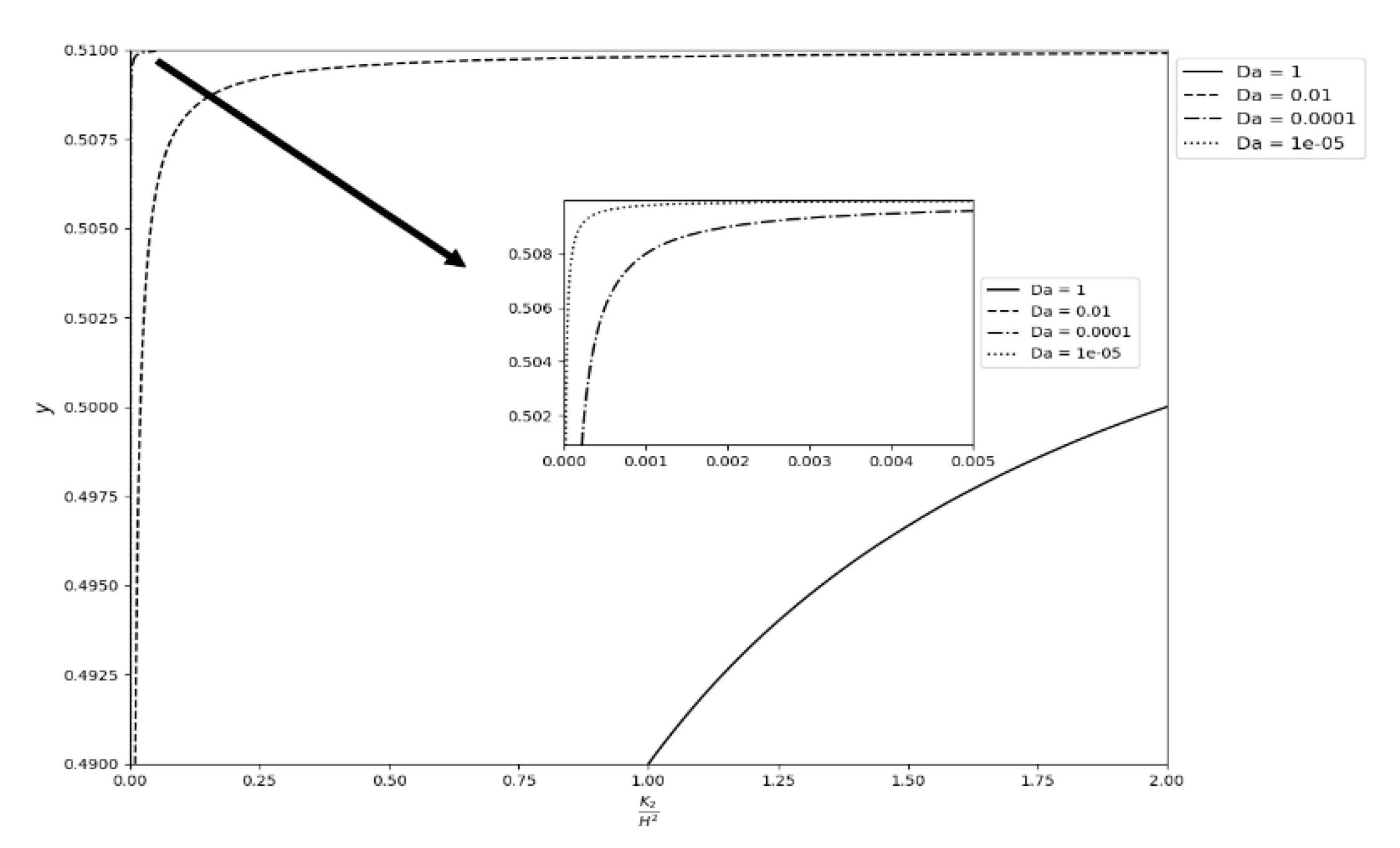

3.4. Shear Stress at the Interfaces

- For a given Da, the value of the shear stress at the upper interface decreases with increasing n for the thick layer. However, it increases with increasing n for thin layer.

- For a given Da, the value of the shear stress at the upper interface increases with increasing n for the thin layer, and decreases with increasing n for the thick layer.

- The thin layer experiences a higher sheer than the thick layer at the upper interface with increasing n.

- The thick layer experiences a higher sheer than the thin layer at the lower interface when n deviates from 1.

3.5. Mean Velocity Across the Layers

4. Conclusions

- The introduction of a generalized permeability function that provides modeling flexibility and validity for small Darcy number, and possible control over permeability amplification in the transition layer.

- Obtaining the general and particular solutions to the resulting inhomogeneous generalized Airy’s equation through the introduction of a generalized Nield-Kuznetsov function.

- Providing an evaluation procedure for the arising generalised Airy’s functions and the generalized Nield-Kuznetsov function.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nield, D.A.; Bejan, A. Convection in porous media, 5th ed.; Springer: New York, 2017.

- Hamdan, M.H. Single-phase flow through porous channels: a review. Flow models and channel entry conditions. J. Applied Math. Comp. 1994, 62, 203-222. [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.A.; Abu Zaytoon, M.S.; Hamdan, M.H. Simulation of flow through layered porous media. IOSR J. Eng. 2016, 6, 48-61.

- Alazmi, B.; Vafai, K. Analysis of fluid flow and heat transfer interfacial conditions between a porous medium and a fluid layer. Int. J. of Heat Mass Transfer. 2001, 44, 1735-1749. [CrossRef]

- Vafai, K.; Thiyagaraja, R. Analysis of flow and heat transfer at the interface region of a porous medium. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 1987, 30, 1391-1405. [CrossRef]

- Kaviany, M. Laminar flow through a porous channel bounded by isothermal parallel plates. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer.1985, 28, 851-858. [CrossRef]

- Rudraiah, N. Coupled parallel flows in a channel and a bounding porous medium of finite thickness, J. Fluids Eng. ASME. 1985, 107, 322-329.

- Rudraiah, N. Flow past porous layers and their stability. Encyclopedia of Fluid Mechanics, Slurry Flow Technology, Gulf Publishing, 1986, pp. 567-647.

- Hill, A. A.; Straughan, B. Poiseuille flow in a fluid overlying a porous medium. J. Fluid Mech. 2008, 603, 137-149.

- Goyeau, B.; Lhuillier, D.; Velarde, M. G. Momentum transport at a fluid-porous interface. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2003, 46, 4071-4081.

- Kaviany, M. Laminar Flow through a porous channel Bounded by isothermal parallel plates, Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 1985, 28, 851-858.

- Sahraoui, M.; Kaviany, M. Slip and no-slip velocity boundary conditions at interface of porous, plain media. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 1992, 35, 927-943. [CrossRef]

- Jamet, D.; Chandesris, M. Boundary conditions at a planar fluid-porous interface for a Poiseuille flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2006, 49, 2137-2150.

- Jamet, D.; Chandesris, M. Boundary conditions at a fluid-porous interface: An a priori estimation of the stress jump coefficients. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2007, 50, 3422-3436.

- Beavers, G.S.; Joseph, D.D. Boundary conditions at a naturally permeable wall. J. Fluid Mech. 1967, 30, 197-207.

- Nield, D.A. The Beavers–Joseph boundary condition and related matters: A historical and critical note. Transp Porous Med. 2009, 78, 537–540.

- Ehrhardt, M. An Introduction to Fluid-Porous Interface Coupling. Weierstrass Institute for Applied Analysis and Stochastics, Berlin, 2010.

- Parvazinia, M.; Nassehi, V.; Wakeman, R. J.; Ghoreishy, M. H. R. Finite element modelling of flow through a porous medium between two parallel plates using the Brinkman equation. Transp. Porous Med. 2006, 63, 71-90.

- Neale, G.; Nader, W. Practical significance of Brinkman’s extension of Darcy’s law: coupled parallel flows within a channel and a bounding porous medium. Canadian J. Chem. Eng. 1974, 52, 475-478.

- Ochoa-Tapia, J. A.;Whitaker, S. Momentum transfer at the boundary between a porous medium and a homogeneous fluid: I) Theoretical Development. Int.J. Heat Mass Transfer 1995, 3, 2635-2646. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Tapia, J. A.;Whitaker, S. Momentum transfer at the boundary between a porous medium and a homogeneous fluid: II) Comparison with experiment. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 1995, 3, 2647-2655.

- Brinkman, H.C. A Calculation of the viscous force exerted by a flowing fluid on a dense swarm of particles. Appl. Sci. Res. 1947, A1, 27-34.

- Roach, D.C.; Hamdan, M.H. Interfacial velocities, slip Parameters and other theoretical expressions arising in the Beavers and Joseph condition. WSEAS Transactions on Fluid Mechanics 2022, 17, 68-78.

- Nield, D.A. The boundary correction for the Rayleigh-Darcy problem: limitations of the Brinkman equation. J. Fluid Mech. 1983, 128, 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Nield, D.A. The limitations of the Brinkman- Forchheimer equation in modeling flow in a saturated porous medium and at an interface. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 1991, 12, 269-272.

- Auriault, J.L. On the domain of validity of Brinkman’s equation. Transp. Porous Med. 2009, 79, 215–223.

- Haider, F.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A. Flow of hybrid nanofluid through Darcy-Forchheimer porous space with variable characteristics. Alexandria Eng. J. 2021, 60, 3047-3056. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Yao, J.; Huang, Z. Analysis of the laminar ow in a transition layer with variable permeability between a free-fluid and a porous medium. Acta Mech. 2013, 224, 1943-1955.

- Abu Zaytoon, M. S.; Alderson, T. L.; Hamdan, M. H. Flow through variable permeability composite porous layers. Gen. Math. Notes. 2016, 33, 26-39.

- Nield, D.A.; Kuznetsov, A.V. The effect of a transition layer between a fluid and a porous medium: shear flow in a channel”, Transp. Porous Med. 2009, 78, 477-487.

- Goharzadeh, A.; Khalili, A.; Jorgensen, B. B. Transition layer thickness at a fluid-porous interface. Phys. Fluids. 2005, 17, 1057102-10571021.

- Duman , T.; Shavit, U. A solution of the laminar ow for a gradual transition between porous and fluid domains. Water Res. Research 2010, 46, 09517.

- Abu Zaytoon, M. S.; Alderson, T. L.; Hamdan, M. H. Flow through layered media with embedded transition porous layer. Int. J. of Enhanced Res. In Sci., Tech. and Eng. 2016, 5, 9-26.

- Abu Zaytoon, M. S.; Alderson, T. L.; Hamdan, M. H. Flow through a variable permeability Brinkman porous core. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2016, 4, 766– 778. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.H.; Kamel, M.T. Flow through variable permeability porous layers. Adv. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2011, 4, 135-145.

- Rees, D.A.S.; Pop, I. Vertical free convection in a porous medium with variable permeability effects. In. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2000, 43, 2565-2571. [CrossRef]

- Siginer, D.A.; Bakhtiyarov, S. I. Flow in porous media of variable permeability and novel effects. J. Appl. Mech. 2001, 68, 312-319. [CrossRef]

- Vafai, K. Analysis of the channeling effect in variable porosity media, ASME J. Energy Resources and Technology 1986, 108, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Roach, D.C.; Hamdan, M.H. Variable permeability and transition layer models for Brinkman equation. In Proceedings Int. Khazar Sci. Res. Conference-III, Khazar University, Baku, Azerbaijan, January 7-9, 2022, IKSAD Publishing House ISBN: 978-625-8423-84-6, pp. 184-191.

- Hamdan, M.H.; Kamel, M.T. On the Ni(x) integral function and its application to the Airy’s non homogeneous equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 21, 7349-7360. [CrossRef]

- Abu Zaytoon, M.S.; Hamdan, M.H.: Weber equation model of flow through a variable permeability porous core bounded by fluid layers. J. Fluids Eng., Trans. ASME, 2022, 144, 041302. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C. A.; Headley, V. B. An extension of Airy’s equation. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1967, 15, 1400-1412. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Flow Equation |

|---|---|

| Navier-Stokes equations | |

| Darcy’s equation | |

| Brinkman’s equation | |

| Forchheimer equation |

| n | Da=0.01 | Da=0.001 | Da=0.0001 | Da=0.00001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.02114994 | 0.01233274 | 0.00649720 | 0.00321735 | |

| 2 | 0.02486639 | 0.01738999 | 0.01133148 | 0.00699674 | |

| 3 | 0.02673316 | 0.02050963 | 0.01498183 | 0.01049763 |

| n | Da=0.01 | Da=0.001 | Da=0.0001 | Da=0.00001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.01570451 | 0.00521685 | 0.00086581 | 0.00002779 | |

| 2 | 0.01359440 | 0.005336297 | 0.0011867 | 0.00006497 | |

| 3 | 0.01217774 | 0.00526991 | 0.00139504 | 0.00011395 |

| Upper Interface |

Da=0.01 Thin Layer |

Da=0.01 Thick Layer |

|---|---|---|

| n=1 | 0.21053324 | 0.10321682 |

| n=2 | 0.21585593 | 0.09206747 |

| n=3 | 0.21940578 | 0.08646717 |

| Lower Interface |

||

| n=1 | 0.05854085 | 0.02721478 |

| n=2 | 0.03743739 | 0.04813607 |

| n=3 | 0.02326929 | 0.06526954 |

| Thick Layer | Da=1 | Da=0.1 | Da=0.01 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=1 | 0.07939500 0.0794* |

0.05692682 | 0.02071123 0.0207* |

| n=2 | 0.08744141 | 0.06403606 | 0.02670879 |

| Thin Layer | |||

| n=1 | 0.07940428 0.0794* |

0.05735128 | 0.02355505 0.0236* |

| n=2 | 0.07945951 | 0.05759342 | 0.0238459 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).