Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Latin America

3. Molecular Data

4. Key Genetic Affected Pathways

4.1. RNA Splicing

4.2. Chromatin Modification

4.3. DNA Methylation

4.4. Transcriptional Regulation

4.5. DNA Damage Response

4.6. Signal Transduction

4.7. Others

5. Molecular Data Integrated in Clinical Scores

6. Molecular Data Incorporated in Current Classifications and New Proposals

7. Molecular Data to Tailor Treatment Strategies

8. Germline Predispositions: Implications and Challenges in Latin America

9. Molecular Tools in Latin America

10. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDS | Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| LA | Latin America |

| SEER | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

| CMML | Chronic myelomonocitic leukemia |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| CNV | Copy number variations |

| IPSS-R | International Prognostic Scoring System Revised |

| IPSS-M | International Prognostic Scoring System Molecular |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| LFS | Leukemia Free Survival |

| VAF | Variant allele frequency |

| HMA | Hypomethylating agents |

| CHIP | Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential |

| PFS | Progression free survival |

| AIPSS | Artificial Intelligence Prognostic Scoring System |

References

- Hasserjian, R.P., U. Germing, and L. Malcovati, Diagnosis and classification of myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood, 2023. 142(26): p. 2247-2257.

- Luo, B., et al., Myelodysplastic syndromes are multiclonal diseases derived from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Exp Hematol Oncol, 2022. 11(1): p. 28.

- Khoury, J.D., et al., The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia, 2022. 36(7): p. 1703-1719.

- Bernard, E., et al., Molecular taxonomy of myelodysplastic syndromes and its clinical implications. Blood, 2024. 144(15): p. 1617-1632.

- Gou, X., Z. Chen, and Y. Shangguan, Global, regional, and national burden of myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloproliferative neoplasms, 1990-2021: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Front Oncol, 2025. 15: p. 1559382.

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Demographic Observatory, 2024 (LC/PUB.2024/22-P), Santiago, 2024.. 2024. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/dc566b9e-b3ef-44e9-a167-995614696404/content.

- Crisp, R., et al., Myelodysplastic syndromes in Latin America: state of the art. Blood Adv, 2018. 2(Suppl 1): p. 60-62.

- Goksu, S.Y., et al., The impact of race and ethnicity on outcomes of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: a population-based analysis. Leuk Lymphoma, 2022. 63(7): p. 1651-1659.

- Borges, D.P., et al., Functional polymorphisms of DNA repair genes in Latin America reinforces the heterogeneity of Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther, 2023. 45(2): p. 147-153.

- Ribeiro Junior, H.L., Molecular monitoring of myelodysplastic neoplasm: Don’t just watch this space, consider the patient’s ancestry. Br J Haematol, 2024. 205(3): p. 759-760.

- Belli, C.B., et al., Myelodysplastic syndromes in South America: a multinational study of 1080 patients. Am J Hematol, 2015. 90(10): p. 851-8.

- Belli, C.B., et al., Application of the revised International Prognostic Scoring System for myelodysplastic syndromes in Argentinean patients. Ann Hematol, 2014. 93(4): p. 705-7.

- Gonzalez, J.S., et al., Prognostic assessment for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in the context of the World Health Organization 2016 proposal: a multicenter study of 280 patients. Ann Hematol, 2021. 100(6): p. 1439-1449.

- Azevedo, R.S., et al., Age, Blasts, Performance Status and Lenalidomide Therapy Influence the Outcome of Myelodysplastic Syndrome With Isolated Del(5q): A Study of 58 South American Patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 2022. 22(1): p. e1-e6.

- Lazzarino, C., et al., Severe thrombocytopenia as a predictor of survival and response to hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndromes: A Latin-American cohort of 212 patients. Am J Hematol, 2020. 95(12): p. E323-E326.

- Castelo, L., et al., Alternative Dosing Schedules of Azacitidine: A Real-World Study Across South American Centers. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 2024. 24(6): p. 407-411.

- Moura, A.T.G., et al., Prolonged response to recombinant human erythropoietin treatment in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome at a single referral centre in Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2019. 74: p. e771.

- Bejar, R., et al., Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2011. 364(26): p. 2496-506.

- Yoshida, K., et al., Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature, 2011. 478(7367): p. 64-9.

- Duployez, N. and C. Preudhomme, Monitoring molecular changes in the management of myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol, 2024. 205(3): p. 772-779.

- Papaemmanuil, E., et al., Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood, 2013. 122(22): p. 3616-27; quiz 3699.

- Haferlach, T., et al., Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia, 2014. 28(2): p. 241-7.

- Bernard, E., et al., Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. NEJM Evid, 2022. 1(7): p. EVIDoa2200008.

- Lincango, M., et al., Assessing the Relevance of Non-molecular Prognostic Systems for Myelodysplastic Syndrome in the Era of Next-Generation Sequencing. Ann Lab Med, 2025. 45(1): p. 44-52.

- Catalán, A.I., et al., Integration of NGS and CNV Analysis in Prognostic Evaluation of MDS in a Developing Country: Insights from Uruguay. Blood Global Hematology, 2025. Accepted for publication, 2025.

- Tseng, C.C. and E.A. Obeng, RNA splicing as a therapeutic target in myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin Hematol, 2024. 61(6): p. 431-441.

- Reinig, E., et al., Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia Aids Diagnosis in Challenging Cases and Identifies Frequent Spliceosome Mutations in Transformed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol, 2016. 145(4): p. 497-506.

- Thol, F., et al., Frequency and prognostic impact of mutations in SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood, 2012. 119(15): p. 3578-84.

- Tefferi, A., et al., Targeted next-generation sequencing in myelodysplastic syndromes and prognostic interaction between mutations and IPSS-R. Am J Hematol, 2017. 92(12): p. 1311-1317.

- Lindsley, R.C., et al., Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood, 2015. 125(9): p. 1367-76.

- Jiang, M., et al., SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: A potential therapeutic target for modulating the entire disease process. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1116438.

- Malcovati, L., et al., SF3B1-mutant MDS as a distinct disease subtype: a proposal from the International Working Group for the Prognosis of MDS. Blood, 2020. 136(2): p. 157-170.

- Lincango, M., I. Larripa, and C. Belli, Bioinformatic Evaluation of Differentially Expressed Genes in Myelodysplastic Syndromes with SF3B1 Variants. Medicina (B Aires), 2022. 82(Supl. V): p. 98.

- Lincango, M., et al., Validation of Novel Hub Genes Expression in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome and SF3B1 Mutations. Medicina (B Aires), 2024. 84(Suppl. V).

- Arber, D.A., et al., International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood, 2022. 140(11): p. 1200-1228.

- Donaires, F.S., et al., Splicing factor SF3B1 mutations and ring sideroblasts in myelodysplastic syndromes: a Brazilian cohort screening study. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter, 2016. 38(4): p. 320-324.

- Sarmiento, M., et al., Efficacy of lenalidomide in a patient with systemic mastocytosis associated with SF3B1-mutant myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma, 2021. 62(12): p. 3027-3030.

- Badar, T., et al., U2AF1 pathogenic variants in myeloid neoplasms and precursor states: distribution of co-mutations and prognostic heterogeneity. Blood Cancer J, 2023. 13(1): p. 149.

- Bersanelli, M., et al., Classification and Personalized Prognostic Assessment on the Basis of Clinical and Genomic Features in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J Clin Oncol, 2021. 39(11): p. 1223-1233.

- Kuendgen, A., et al., Efficacy of azacitidine is independent of molecular and clinical characteristics - an analysis of 128 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia and a review of the literature. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(45): p. 27882-27894.

- Kim, E., et al., SRSF2 Mutations Contribute to Myelodysplasia by Mutant-Specific Effects on Exon Recognition. Cancer Cell, 2015. 27(5): p. 617-30.

- Makishima, H., et al., Dynamics of clonal evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet, 2017. 49(2): p. 204-212.

- Nagehan, P., et al., Impact of single versus multiple spliceosome mutations on myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Exp Hematop, 2023. 63(3): p. 173-176.

- Cockey, S.G., et al., Molecular landscape and clinical outcome of SRSF2/TET2 Co-mutated myeloid neoplasms. Leuk Lymphoma, 2025. 66(3): p. 469-478.

- Thol, F., et al., Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(18): p. 2499-506.

- Yang, L., X. Wei, and Y. Gong, Prognosis and risk factors for ASXL1 mutations in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Med, 2024. 13(1): p. e6871.

- Lin, Y., et al., Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: A meta-analysis. Hematology, 2016. 21(8): p. 454-61.

- Rinke, J., et al., EZH2 in Myeloid Malignancies. Cells, 2020. 9(7).

- Ball, S., et al., Clinical characteristics and outcomes of EZH2-mutant myelodysplastic syndrome: A large single institution analysis of 1774 patients. Leuk Res, 2023. 124: p. 106999.

- Damm, F., et al., BCOR and BCORL1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and related disorders. Blood, 2013. 122(18): p. 3169-77.

- Sportoletti, P., D. Sorcini, and B. Falini, BCOR gene alterations in hematologic diseases. Blood, 2021. 138(24): p. 2455-2468.

- Baranwal, A., et al., Genetic landscape and clinical outcomes of patients with BCOR mutated myeloid neoplasms. Haematologica, 2024. 109(6): p. 1779-1791.

- Liu, Y., et al., Next generation sequencing reveals the mutation landscape of Chinese MDS patients and the association between mutations and AML transformations. Hematology, 2024. 29(1): p. 2392469.

- Meyer, C., et al., The KMT2A recombinome of acute leukemias in 2023. Leukemia, 2023. 37(5): p. 988-1005.

- Wei, Q., et al., Detection of KMT2A Partial Tandem Duplication by Optical Genome Mapping in Myeloid Neoplasms: Associated Cytogenetics, Gene Mutations, Treatment Responses, and Patient Outcomes. Cancers (Basel), 2024. 16(24).

- Lee, W.H., et al., Validation of the molecular international prognostic scoring system in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes defined by international consensus classification. Blood Cancer J, 2023. 13(1): p. 120.

- Fathima, S., et al., Myeloid neoplasms with PHF6 mutations: context-dependent genomic and prognostic characterization in 176 informative cases. Blood Cancer J, 2025. 15(1): p. 28.

- Zuo, Z., et al., Concurrent Mutations in SF3B1 and PHF6 in Myeloid Neoplasms. Biology (Basel), 2022. 12(1).

- Sudunagunta, V.S. and A.D. Viny, Untangling the loops of STAG2 mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma, 2025. 66(1): p. 6-15.

- Kon, A., et al., Recurrent mutations in multiple components of the cohesin complex in myeloid neoplasms. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(10): p. 1232-7.

- Katamesh, B., et al., Clinical and prognostic impact of STAG2 mutations in myeloid neoplasms: the Mayo Clinic experience. Blood Adv, 2023. 7(8): p. 1351-1355.

- Deb, P.Q. and W. Xiao, “Ring-form” megakaryocytic dysplasia in STAG2-mutated myelodysplastic neoplasm. Blood, 2024. 143(21): p. 2218.

- Kawashima, N., et al., Landscape of biallelic DNMT3A mutant myeloid neoplasms. J Hematol Oncol, 2024. 17(1): p. 87.

- Yang, L., R. Rau, and M.A. Goodell, DNMT3A in haematological malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer, 2015. 15(3): p. 152-65.

- Challen, G.A., et al., Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Genet, 2011. 44(1): p. 23-31.

- Jaiswal, S., et al., Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371(26): p. 2488-98.

- Lee, W.H., et al., Clinico-genetic and prognostic analyses of 716 patients with primary myelodysplastic syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia based on the 2022 International Consensus Classification. Am J Hematol, 2023. 98(3): p. 398-407.

- GenoMed4All, c., A sex-informed approach to improve the personalised decision making process in myelodysplastic syndromes: a multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Haematol, 2023. 10(2): p. e117-e128.

- Jawad, M., et al., DNMT3A R882 Mutations Confer Unique Clinicopathologic Features in MDS Including a High Risk of AML Transformation. Front Oncol, 2022. 12: p. 849376.

- Zhang, X., et al., TET (Ten-eleven translocation) family proteins: structure, biological functions and applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023. 8(1): p. 297.

- Hawking, Z.L. and J.M. Allan, Landscape of TET2 Mutations: From Hematological Malignancies to Solid Tumors. Cancer Med, 2025. 14(6): p. e70792.

- Smith, A.E., et al., Next-generation sequencing of the TET2 gene in 355 MDS and CMML patients reveals low-abundance mutant clones with early origins, but indicates no definite prognostic value. Blood, 2010. 116(19): p. 3923-32.

- Danishevich, A., et al., Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Clinical Characteristics and Significance of Preclinically Detecting Biallelic Mutations in the TET2 Gene. Life (Basel), 2024. 14(5).

- Awada, H., et al., Invariant phenotype and molecular association of biallelic TET2 mutant myeloid neoplasia. Blood Adv, 2019. 3(3): p. 339-349.

- Bezerra, M.F., et al., Screening for myeloid mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther, 2022. 44(3): p. 328-331.

- Komrokji, R., et al., IDH mutations are enriched in myelodysplastic syndrome patients with severe neutropenia and can be a potential for targeted therapy. Haematologica, 2023. 108(4): p. 1168-1172.

- Patnaik, M.M., et al., Differential prognostic effect of IDH1 versus IDH2 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: a Mayo Clinic study of 277 patients. Leukemia, 2012. 26(1): p. 101-5.

- Wang, N., et al., IDH1 Mutation Is an Independent Inferior Prognostic Indicator for Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Acta Haematol, 2017. 138(3): p. 143-151.

- Jain, A.G., et al., Patterns of lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome progression: factors predicting progression to high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica, 2024. 109(7): p. 2157-2164.

- Bellissimo, D.C. and N.A. Speck, RUNX1 Mutations in Inherited and Sporadic Leukemia. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2017. 5: p. 111.

- Sutandyo, N., et al., Association of Somatic Gene Mutations with Risk of Transformation into Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2022. 23(4): p. 1107-1116.

- He, W., C. Zhao, and H. Hu, Prognostic effect of RUNX1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: a meta-analysis. Hematology, 2020. 25(1): p. 494-501.

- Wang, Y.H., et al., Higher RUNX1 expression levels are associated with worse overall and leukaemia-free survival in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. EJHaem, 2022. 3(4): p. 1209-1219.

- Watad, A., et al., Somatic Mutations and the Risk of Undifferentiated Autoinflammatory Disease in MDS: An Under-Recognized but Prognostically Important Complication. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 610019.

- Okano, T., et al., Somatic mutation in RUNX1 underlies mucocutaneus inflammatory manifestations. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2021. 60(12): p. e429-e431.

- Hulea, L. and A. Nepveu, CUX1 transcription factors: from biochemical activities and cell-based assays to mouse models and human diseases. Gene, 2012. 497(1): p. 18-26.

- Dermawan, J.K., et al., Clinically Significant CUX1 Mutations Are Frequently Subclonal and Common in Myeloid Disorders With a High Number of Co-mutated Genes and Dysplastic Features. Am J Clin Pathol, 2022. 157(4): p. 586-594.

- Aly, M., et al., Distinct clinical and biological implications of CUX1 in myeloid neoplasms. Blood Adv, 2019. 3(14): p. 2164-2178.

- Wang, Q., et al., ETV6 mutation in a cohort of 970 patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica, 2014. 99(10): p. e176-8.

- Gurney, M., et al., The clinical and molecular spectrum of ETV6 mutated myeloid neoplasms. Br J Haematol, 2023. 202(2): p. 279-283.

- Siddon, A.J. and O.K. Weinberg, Diagnosis and Classification of Myelodysplastic Syndromes with Mutated TP53. Clin Lab Med, 2023. 43(4): p. 607-614.

- Boada, M., et al., TP53 Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Latin America. Real World Data from Latin American MDS Group (GLAM). Leukemia Research, 2023. 128S: p. 107158.

- Hsu, J.I., et al., PPM1D Mutations Drive Clonal Hematopoiesis in Response to Cytotoxic Chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell, 2018. 23(5): p. 700-713 e6.

- Fandrei, D., et al., Clonal Evolution of PPM1D Mutations in the Spectrum of Myeloid Disorders. Clin Cancer Res, 2025.

- Xu, F., et al., Somatic mutations of activating signalling, transcription factor, and tumour suppressor are a precondition for leukaemia transformation in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Cell Mol Med, 2022. 26(23): p. 5901-5916.

- Menssen, A.J., et al., Convergent Clonal Evolution of Signaling Gene Mutations Is a Hallmark of Myelodysplastic Syndrome Progression. Blood Cancer Discov, 2022. 3(4): p. 330-345.

- Sumiyoshi, R., et al., The FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutation at disease diagnosis is a negative prognostic factor in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Leuk Res, 2022. 113: p. 106790.

- da Silva-Coelho, P., et al., Clonal evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 15099.

- Ren, Y., et al., Co-mutation landscape and clinical significance of RAS pathway related gene mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Hematol Oncol, 2023. 41(1): p. 159-166.

- Pinheiro, R.F., et al., The Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is the most important gene for repairing the DNA in Myelodysplastic Neoplasm. DNA Repair (Amst), 2025. 146: p. 103803.

- Yang, X.J. and E. Seto, HATs and HDACs: from structure, function and regulation to novel strategies for therapy and prevention. Oncogene, 2007. 26(37): p. 5310-8.

- Dai, Y. and D.V. Faller, Transcription Regulation by Class III Histone Deacetylases (HDACs)-Sirtuins. Transl Oncogenomics, 2008. 3: p. 53-65.

- Goes, J.V.C., et al., Gene expression patterns of Sirtuin family members (SIRT1 TO SIRT7): Insights into pathogenesis and prognostic of Myelodysplastic neoplasm. Gene, 2024. 915: p. 148428.

- Greenberg, P.L., et al., Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood, 2012. 120(12): p. 2454-65.

- Baliakas, P., et al., How to manage patients with germline DDX41 variants: Recommendations from the Nordic working group on germline predisposition for myeloid neoplasms. Hemasphere, 2024. 8(8): p. e145.

- Nazha, A., et al., Personalized Prediction Model to Risk Stratify Patients With Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J Clin Oncol, 2021. 39(33): p. 3737-3746.

- Mosquera Orgueira, A., et al., Machine Learning Improves Risk Stratification in Myelodysplastic Neoplasms: An Analysis of the Spanish Group of Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Hemasphere, 2023. 7(10): p. e961.

- Huber, S., et al., MDS subclassification-do we still have to count blasts? Leukemia, 2023. 37(4): p. 942-945.

- Loghavi, S., et al., Fifth Edition of the World Health Classification of Tumors of the Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue: Myeloid Neoplasms. Mod Pathol, 2024. 37(2): p. 100397.

- Vaughan, L. and J.E. Pimanda, Seeing MDS through the lens of genomics. Blood, 2024. 144(15): p. 1552-1554.

- Mendonca, P.D.S., R.F. Pinheiro, and S.M.M. Magalhaes, Myelodysplastic Syndrome Over Time: A Comparative Analysis of Overall Outcome. Mayo Clin Proc, 2019. 94(12): p. 2593-2594.

- Basquiera, A., et al., Myelodysplasia-Related Mortality Remains the Main Cause of Death Along Different Groups of Risks: An Analysis from MDS Argentinean Study Group. Haematologica, 2017. 102(s2): p. 485. Abstract n. 1182.

- Al-Kali, A., et al., Outcome of Myelodysplastic Syndromes Over Time in the United States: A National Cancer Data Base Study From 2004-2013. Mayo Clin Proc, 2019. 94(8): p. 1467-1474.

- Burke, S., O. Chowdhury, and K. Rouault-Pierre, Low-risk MDS-A spotlight on precision medicine for SF3B1-mutated patients. Hemasphere, 2025. 9(3): p. e70103.

- DiNardo, C.D., et al., Final phase 1 substudy results of ivosidenib for patients with mutant IDH1 relapsed/refractory myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood Adv, 2024. 8(15): p. 4209-4220.

- DiNardo, C.D., et al., Targeted therapy with the mutant IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib for high-risk IDH2-mutant myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood Adv, 2023. 7(11): p. 2378-2387.

- Othman, J., et al., Molecular MRD is strongly prognostic in patients with NPM1-mutated AML receiving venetoclax-based nonintensive therapy. Blood, 2024. 143(4): p. 336-341.

- Senapati, J., et al., Venetoclax abrogates the prognostic impact of splicing factor gene mutations in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, 2023. 142(19): p. 1647-1657.

- Lachowiez, C.A., et al., Contemporary outcomes in IDH-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: The impact of co-occurring NPM1 mutations and venetoclax-based treatment. Am J Hematol, 2022. 97(11): p. 1443-1452.

- Nanaa, A., et al., Venetoclax plus hypomethylating agents in DDX41-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: Mayo Clinic series on 12 patients. Br J Haematol, 2024. 204(1): p. 171-176.

- Itzykson, R., et al., Impact of TET2 mutations on response rate to azacitidine in myelodysplastic syndromes and low blast count acute myeloid leukemias. Leukemia, 2011. 25(7): p. 1147-52.

- Traina, F., et al., Impact of molecular mutations on treatment response to DNMT inhibitors in myelodysplasia and related neoplasms. Leukemia, 2014. 28(1): p. 78-87.

- Hu, C. and X. Wang, Predictive and prognostic value of gene mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome treated with hypomethylating agents: a meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma, 2022. 63(10): p. 2336-2351.

- Zhang, J., et al., Germline Mutations in Predisposition Genes in Pediatric Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373(24): p. 2336-2346.

- Schwartz, J.R., et al., The genomic landscape of pediatric myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1557.

- Feurstein, S., et al., Germline variants drive myelodysplastic syndrome in young adults. Leukemia, 2021. 35(8): p. 2439-2444.

- Sebert, M., et al., Germline DDX41 mutations define a significant entity within adult MDS/AML patients. Blood, 2019. 134(17): p. 1441-1444.

- Churpek, J.E., et al., Genomic analysis of germ line and somatic variants in familial myelodysplasia/acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, 2015. 126(22): p. 2484-90.

- DiNardo, C.D., et al., Evaluation of Patients and Families With Concern for Predispositions to Hematologic Malignancies Within the Hereditary Hematologic Malignancy Clinic (HHMC). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 2016. 16(7): p. 417-428 e2.

- Zhang, J., K.E. Nichols, and J.R. Downing, Germline Mutations in Predisposition Genes in Pediatric Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374(14): p. 1391.

- Yang, F., et al., Identification and prioritization of myeloid malignancy germline variants in a large cohort of adult patients with AML. Blood, 2022. 139(8): p. 1208-1221.

- Feurstein, S., et al., Germ line predisposition variants occur in myelodysplastic syndrome patients of all ages. Blood, 2022. 140(24): p. 2533-2548.

- Trottier, A.M., S. Feurstein, and L.A. Godley, Germline predisposition to myeloid neoplasms: Characteristics and management of high versus variable penetrance disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol, 2024. 37(1): p. 101537.

- Arber, D.A., et al., The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood, 2016. 127(20): p. 2391-405.

- Owen, C., M. Barnett, and J. Fitzgibbon, Familial myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukaemia--a review. Br J Haematol, 2008. 140(2): p. 123-32.

- Smith, M.L., et al., Mutation of CEBPA in familial acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med, 2004. 351(23): p. 2403-7.

- Tawana, K., et al., Disease evolution and outcomes in familial AML with germline CEBPA mutations. Blood, 2015. 126(10): p. 1214-23.

- Taskesen, E., et al., Prognostic impact, concurrent genetic mutations, and gene expression features of AML with CEBPA mutations in a cohort of 1182 cytogenetically normal AML patients: further evidence for CEBPA double mutant AML as a distinctive disease entity. Blood, 2011. 117(8): p. 2469-75.

- Polprasert, C., et al., Inherited and Somatic Defects in DDX41 in Myeloid Neoplasms. Cancer Cell, 2015. 27(5): p. 658-70.

- Quesada, A.E., et al., DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms are associated with male gender, TP53 mutations and high-risk disease. Am J Hematol, 2019. 94(7): p. 757-766.

- Makishima, H., et al., Germ line DDX41 mutations define a unique subtype of myeloid neoplasms. Blood, 2023. 141(5): p. 534-549.

- Auger, N., et al., Cytogenetics in the management of myelodysplastic neoplasms (myelodysplastic syndromes, MDS): Guidelines from the groupe francophone de cytogenetique hematologique (GFCH). Curr Res Transl Med, 2023. 71(4): p. 103409.

- Homan, C.C., et al., Somatic mutational landscape of hereditary hematopoietic malignancies caused by germline variants in RUNX1, GATA2, and DDX41. Blood Adv, 2023. 7(20): p. 6092-6107.

- Saygin, C., et al., Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant outcomes in adults with inherited myeloid malignancies. Blood Adv, 2023. 7(4): p. 549-554.

- Owen, C.J., et al., Five new pedigrees with inherited RUNX1 mutations causing familial platelet disorder with propensity to myeloid malignancy. Blood, 2008. 112(12): p. 4639-45.

- Song, W.J., et al., Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet, 1999. 23(2): p. 166-75.

- Arepally, G., et al., Evidence for genetic homogeneity in a familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia (FPD/AML). Blood, 1998. 92(7): p. 2600-2.

- Beri-Dexheimer, M., et al., Clinical phenotype of germline RUNX1 haploinsufficiency: from point mutations to large genomic deletions. Eur J Hum Genet, 2008. 16(8): p. 1014-8.

- Churpek, J.E., et al., Identification and molecular characterization of a novel 3′ mutation in RUNX1 in a family with familial platelet disorder. Leuk Lymphoma, 2010. 51(10): p. 1931-5.

- Michaud, J., et al., In vitro analyses of known and novel RUNX1/AML1 mutations in dominant familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: implications for mechanisms of pathogenesis. Blood, 2002. 99(4): p. 1364-72.

- Noris, P. and A. Pecci, Hereditary thrombocytopenias: a growing list of disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2017. 2017(1): p. 385-399.

- Noris, P., et al., Mutations in ANKRD26 are responsible for a frequent form of inherited thrombocytopenia: analysis of 78 patients from 21 families. Blood, 2011. 117(24): p. 6673-80.

- Noris, P., et al., ANKRD26-related thrombocytopenia and myeloid malignancies. Blood, 2013. 122(11): p. 1987-9.

- Marconi, C., et al., 5’UTR point substitutions and N-terminal truncating mutations of ANKRD26 in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol, 2017. 10(1): p. 18.

- Noetzli, L., et al., Germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red cell macrocytosis and predisposition to lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(5): p. 535-538.

- Rampersaud, E., et al., Germline deletion of ETV6 in familial acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv, 2019. 3(7): p. 1039-1046.

- Zhang, M.Y., et al., Germline ETV6 mutations in familial thrombocytopenia and hematologic malignancy. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(2): p. 180-5.

- Wlodarski, M.W., et al., Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of GATA2-related myelodysplastic syndromes in children and adolescents. Blood, 2016. 127(11): p. 1387-97; quiz 1518.

- Hahn, C.N., et al., Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet, 2011. 43(10): p. 1012-7.

- Donadieu, J., et al., Natural history of GATA2 deficiency in a survey of 79 French and Belgian patients. Haematologica, 2018. 103(8): p. 1278-1287.

- Spinner, M.A., et al., GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood, 2014. 123(6): p. 809-21.

- Sahoo, S.S., E.J. Kozyra, and M.W. Wlodarski, Germline predisposition in myeloid neoplasms: Unique genetic and clinical features of GATA2 deficiency and SAMD9/SAMD9L syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol, 2020. 33(3): p. 101197.

- Bluteau, O., et al., A landscape of germ line mutations in a cohort of inherited bone marrow failure patients. Blood, 2018. 131(7): p. 717-732.

- Narumi, S., et al., SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nat Genet, 2016. 48(7): p. 792-7.

- Gonzalez, K.D., et al., Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol, 2009. 27(8): p. 1250-6.

- Baliakas, P., et al., Nordic Guidelines for Germline Predisposition to Myeloid Neoplasms in Adults: Recommendations for Genetic Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Follow-up. Hemasphere, 2019. 3(6): p. e321.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Myelodysplastic Syndromes (Version 2.2025). 2025 April 13, 2025]. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mds.pdf.

- Hemoterapia, S.E.d.H.y. Manual para el Diagnóstico y Atención Clínica en la Predisposición Germinal a Neoplasias Hematológicas. 2024. Available online: https://sehh.es/publicaciones/manuales-publicaciones/126044-manual-para-el-diagnostico-y-atencion-clinica-en-la-predisposicion-germinal-a-neoplasias-hematologicas.

- Roloff, G.W., L.A. Godley, and M.W. Drazer, Assessment of technical heterogeneity among diagnostic tests to detect germline risk variants for hematopoietic malignancies. Genet Med, 2021. 23(1): p. 211-214.

- DeRoin, L., et al., Feasibility and limitations of cultured skin fibroblasts for germline genetic testing in hematologic disorders. Hum Mutat, 2022. 43(7): p. 950-962.

- Drazer, M.W., et al., Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with ANKRD26 or ETV6 germline mutations. Blood Adv, 2022. 6(15): p. 4357-4359.

- Gutierrez-Rodrigues, F., et al., Differential diagnosis of bone marrow failure syndromes guided by machine learning. Blood, 2023. 141(17): p. 2100-2113.

- Kamiya, L.J., et al., Two novel families with RUNX1 variants indicate glycine 168 as a new mutational hotspot: Implications for FPD/AML diagnosis. Br J Haematol, 2024. 205(6): p. 2315-2320.

- Cunningham, L., et al., Natural history study of patients with familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancy. Blood, 2023. 142(25): p. 2146-2158.

- Bove, V., et al., Myelodysplastic syndrome with dual germline RUNX1 and DDX41 variants: a rare genetic predisposition case. Fam Cancer, 2025. 24(1): p. 20.

- Spangenberg, M.N., et al., Unusual Co-Occurrence of Multiple Myeloma and AML in a Patient With Germline CEBPA Variant. Expanding the Spectrum of Hereditary Hematologic Malignancies. Clin Genet, 2025. 107(5): p. 576-578.

- Boada, M., et al., Germline CEBPA mutation in familial acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Rep, 2021. 13(3): p. 9114.

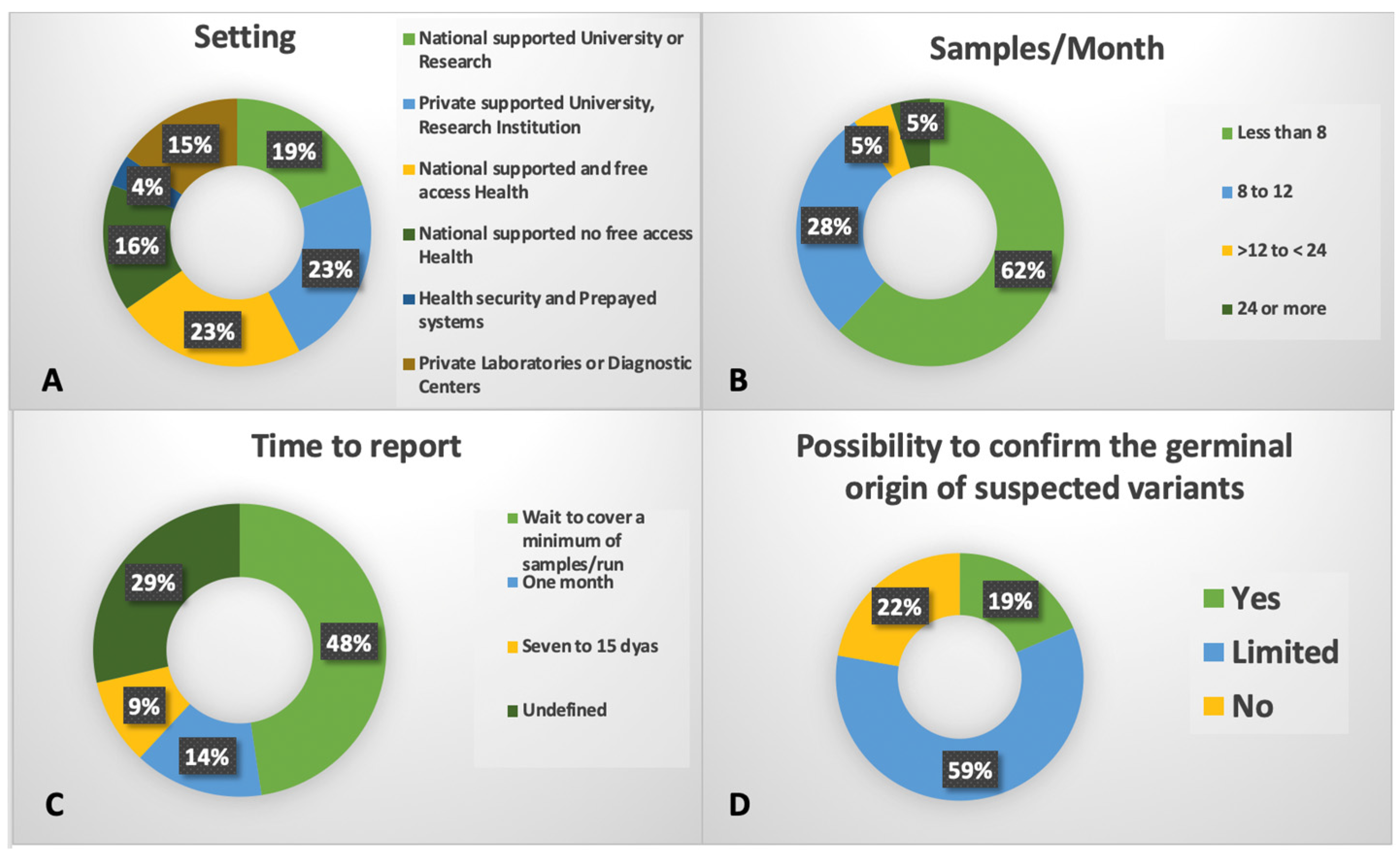

- Belli, C., et al., P008 - Topic: AS01-Diagnosis/AS01c-Molecular aberrations (cytogenetic, genetic, gene expression): REAL-WORLD LABORATORY PRACTICE PATTERNS ON NEXT-GENERATION-SEQUENCING (NGS) TECHNOLOGY IN LATIN AMERICA. Leukemia Research, 2023. 128: p. 107143.

- Crisp, R., et al., [Preferences and limitations of hematologists to address the complexity of myelodysplastic syndromes]. Medicina (B Aires), 2019. 79(3): p. 174-184.

- Grille Montauban, S., et al., Flow cytometry “Ogata score” for the diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes in a real-life setting. A Latin American experience. Int J Lab Hematol, 2019. 41(4): p. 536-541.

- Grille, S., et al., Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Latin-America - Results from a Novel International Registry: Re-Glam. Blood, 2022. 140(Supplement 1): p. 4096-4097.

- Cazzola, M. and L. Malcovati, Genome sequencing in the management of myelodysplastic syndromes and related disorders. Haematologica, 2025. 110(2): p. 312-329.

| Group | Entity | % | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated 5 established subgroups | DDX41 | 3.3 | 56% of patients with mutated DDX41 had both a putative germ line DDX41 variant (defined here as >30% VAF) and a somatic DDX41 mutation, 37% only a putative germ line DDX41 variant, and 7% only somatic DDX41 mutations. |

| AML-like | 2 | NPM1 mutations or at least 2 events from WT1, FLT3, MLLPTD, or MYC mutations. | |

| TP53 complex | 10 | Multihit TP53 mutations were present in 74% cases, of which 91% had complex karyotype. | |

| del/5q) | 6.9 | Presence of del(5q) as the sole cytogenetic abnormality or with 1 additional abnormality excluding −7/7q. Monoallelic TP53 mutations were significantly enriched in this group | |

| SF3B1 | 14 | Indolent clinical course. | |

| Confirmed 3 previously reported subgroups | Bi-allelic TET2 | 13 | Early biallelic TET2 mutations with splicing factor mutations in 80% of patients, most commonly affecting SRSF2, SF3B1, or ZRSR2. Modulation of phenotype by ASXL1 and RAS mutations driving monocytosis and JAK2 driving thrombocytosis. |

| der(1;7) | 0.5 | ETNK1 mutations were enriched in this group. | |

| CCUS-like | 6.9 | 46% had a single mutated gene (TET2, or DNMT3A), 8% had loss of Y without gene mutations, and 6% only had ≥2 DTA mutations. | |

| Eight novel subgroups | -7/SETBP1 | 4.9 | SETBP1 mutations and/or −7 in the absence of complex karyotype. GATA2 variants were prevalent. |

| EZH2-ASXL1 | 4 | ASXL1 and EZH2 mutation co-occurrence. High molecular complexity (75% of patients with ≥5 mutated genes). | |

| IDH-STAG2 | 8.9 | Mutations at the IDH2 R140 hot spot, IDH1, and/or STAG2 co-occurring with either SRSF2 or ASXL1 mutations | |

| BCOR/L1 | 3.5 | 83% of patients had mutations in BCOR, 33% in BCORL1, and 17% in both genes. | |

| U2AF1 | 4.3 | 58% had a Q157 mutation, 41% had a S34 mutation, and 1% had both. | |

| SRSF2 | 2.2 | Aggressive disease. | |

| ZRSR2 | 1.3 | Indolent clinical course. | |

| Two subgroups without defining genetic events | Not otherwise specified | 7.9 | Presence of other cytogenetic abnormalities and/or mutations in 51 other recurrently mutated genes |

| No event | 6.5 | Absence of any recurrent drivers evaluated. |

| World Health Organization (2022) fifth edition | International Consensus Classification (2022) |

|---|---|

|

Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition without a preexisting platelet disorder or organ dysfunction: Germline CEBPA P/LP variant Germline DDX41 P/LP variant Germline TP53 P/LP variant |

Hematologic neoplasms with germline predisposition without a constitutional disorder affecting multiple organ systems: Myeloid neoplasms with germline CEBPA variant Myeloid or lymphoid neoplasms with germline DDX41 variant Myeloid or lymphoid neoplasms with germline TP53 variant |

|

Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition and pre-existing platelet disorder: Germline RUNX1 P/LP variant Germline ANKRD26 P/LP variant Germline ETV6 P/LP variant |

Hematologic neoplasms with germline predisposition associated with a constitutional platelet disorder: Myeloid or lymphoid neoplasms with germline RUNX1 variant Myeloid neoplasms with germline ANKRD26 variant Myeloid or lymphoid neoplasms with germline ETV6 variant |

|

Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition and potential organ dysfunction: Germline GATA2 P/LP variant Bone marrow failure syndromes (Severe congenital neutropenia Shwachman, Diamond syndrome, Fanconi anemia) Telomere biology disorders RASopathies (Neurofibromatosis type 1, CBL syndrome Noonan syndrome or Noonan syndrome–like disorders) Down syndrome Germline SAMD9 P/LP variant (MIRAGE Syndrome) Germline SAMD9L P/LP variant (SAMD9L-related Ataxia Pancytopenia Syndrome) Biallelic germline BLM P/LP variant (Bloom syndrome) |

Hematologic neoplasms with germline predisposition associated with a constitutional disorder affecting multiple organ systems: Myeloid neoplasms with germline GATA2 variant Myeloid neoplasms with germline SAMD9 variant Myeloid neoplasms with germline SAMD9L variant Myeloid neoplasms associated with bone marrow failure syndromes (Fanconi anemia, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Telomere biology disorders, including dyskeratosis congenita Severe congenital neutropenia, Diamond-Blackfan anemia) JMML associated with neurofibromatosis JMML associated with Noonan syndrome and Noonan syndrome–like disorder Myeloid or lymphoid neoplasms associated with Down syndrome |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).