1. Introduction

Recently, a large number of scientists have been concerned about the sharp downward trend in the level of the Caspian Sea, which has been observed since 2005. The coastline migration is especially noticeable in the northern part of the sea, as it is characterized by shallow water. In addition, the northern part of Kazakhstan is rich in oil and gas deposits. It is strategically important not only for Kazakhstan, but also for other Caspian countries. This importance is due to economic, political, social, biological-ecological and recreational aspects. In addition, the waters of the Caspian Sea are home to the Caspian seal, which is endemic. It is classified as an endangered group of mammals. The main stages of the life cycle of Caspian seals, such as birth of calves, nursing and molting take place on the ice and islands of the Northern Caspian Sea.

Lev Semenovich Berg was one of the first to summarize the results of this research in his famous work “The Level of the Caspian Sea over Historical Time”. His work was published more than 100 years ago (Berg, 1934). In his study of water level fluctuations in the Caspian Sea, L.S. Berg concluded that the main cause of its changes is climate.

The history of the Caspian Sea is characterized by a complex course of natural processes. In historical time, there has been a repeated change of low and high stands of the Caspian Sea level. Scientists have obtained data to reconstruct the history of the Caspian Sea development by studying ancient marine terraces. These terraces are widespread along the coast. They also analyzed sediments from natural outcrops and drilling samples.

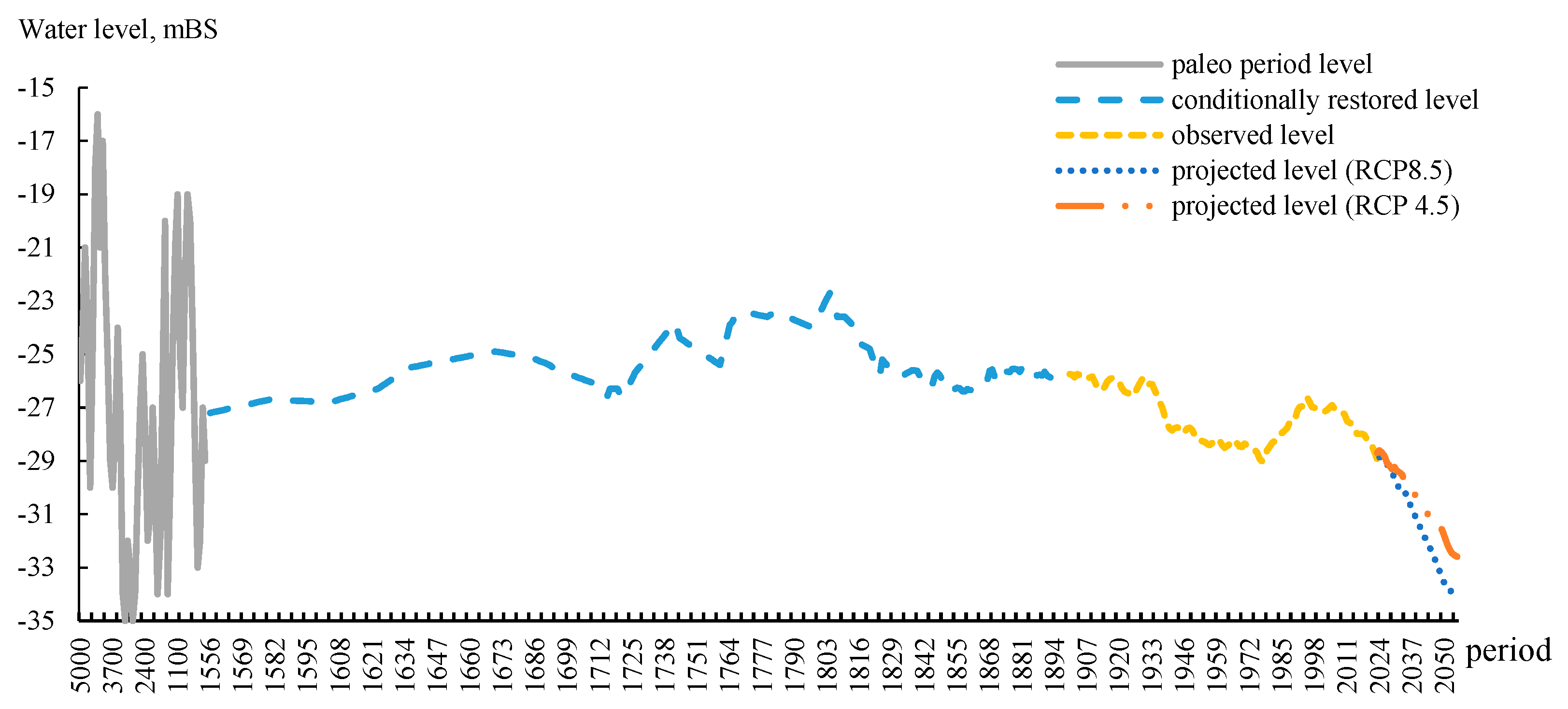

Scientists are currently concerned about the future of the Caspian Sea, due to rapid climate change. The interest of this paper is to combine studies of level changes in the early Caspian transgression, the New Caspian time, the Derbent regression, with the present-day observed level and with the level that we have projected for the future up to 2055, considering the impact of climate change. This will make it possible to trace the course of the Caspian Sea level in historical times, at present and in the future.

Actuality

The study of the Caspian Sea level change has always had an increased relevance. In different periods of time, the level of the Caspian Sea has changed within quite large limits. Changes in the level always bring about important problems: flooding of important objects, roads, buildings, or retreat of water over long distances. At present, there is a clear tendency for the Caspian Sea level to decrease. Therefore, scientists from different countries are concerned about the causes and consequences of this decline (Haustov et al., 2018; Pigaryov, 2022; Tabelinova, 2019). Many scientists are engaged in the development of forecasts of changes in the Caspian Sea level for the future. German scientists Rohit Samant and Matthias Prange published an article on the Caspian Sea level changes for the future up to the end of the 21st century (Samant et al., 2023).

They used 15 coupled climate models, two climate change scenarios (SSP245 and SSP585) and three general socio-economic trajectories to estimate future changes in Caspian Sea level. According to their data, the projected increase in evaporation will significantly exceed the increase in precipitation in the whole Caspian Sea catchment area. This will result in a negative water balance during the 21st century. The authors of the article assume that the decrease in the level of the Caspian Sea under the influence of climate change by the end of the current century under the SSP245 scenario will be about 8 m, and under the SSP585 scenario it will be 14 m.

A group of scientists from the UK also published a forecast of Caspian Sea level changes for the future (Koriche et al., 2021).

In their work, the authors studied the change in the water balance in the Caspian Sea catchment area and its potential impact on the Caspian Sea level in the 21st century. They used data from selected climate change scenarios of the general socioeconomic pathway (SSPs) and representative concentration pathway (RCPs), and also investigated anthropogenic influence. Moisture deficit is more pronounced for scenarios with extreme radiative forcing (RCP8.5/SSP585). By 2100, the Caspian Sea level decline under the RCP4.5 (RCP8.5) scenario will be up to 8 (10) meters. The rate of water withdrawal and anthropogenic influence also play a major role in determining the future level of the Caspian Sea. Further declines in level could lead to the drying up of the shallow northern part of the Caspian Sea. This will have wide-ranging consequences for the livelihoods of surrounding communities, increasing vulnerability to freshwater scarcity, transforming ecosystems, and affecting the entire climate system.

2. Materials and Methods

Caspian Sea level changes are divided into two main types: eustatic and deformation. The first type includes secular, perennial, interannual and seasonal fluctuations that depend on changes in water volume. The second type includes runup and surge fluctuations of sea level, seiches, and breeze oscillations, which affect only the redistribution of water over the sea area. In this paper, we consider only eustatic changes.

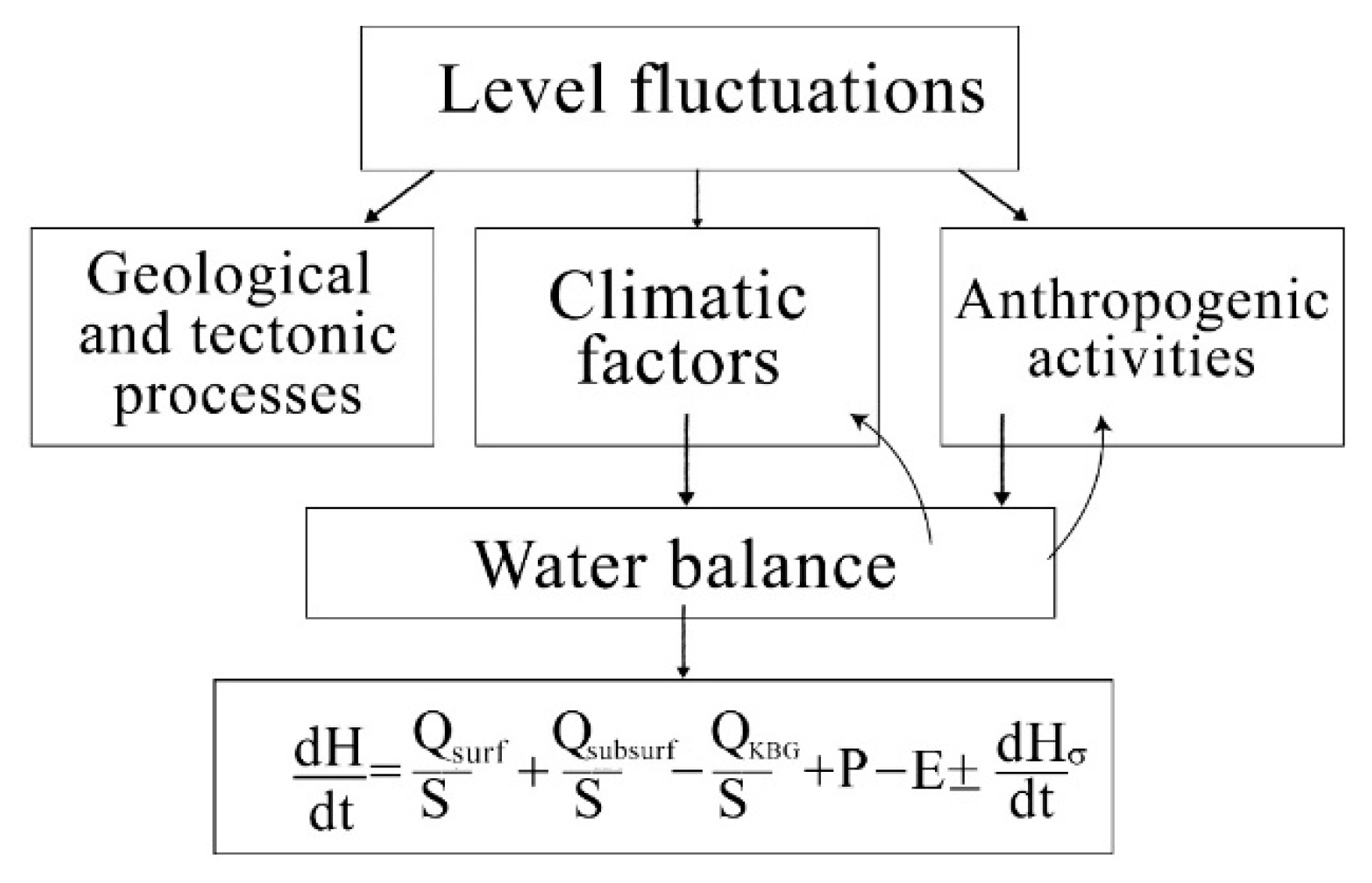

Many factors influence the secular and multiyear variations in sea level (

Figure 1).

The study of Caspian Sea level changes over such a long period was carried out using different methods at different stages. The Caspian Sea level fluctuations during the paleoperiod were systematized and analyzed using literature sources (Berg, 1934; Varuschenko et al., 1987; Fedorov, 1957; Nikolaeva et al., 1962). ArcGis program was used to assess the changes in the Caspian Sea coastline at different water levels and to construct maps. During the period of instrumental observations of the Caspian Sea level, data from the sea gauging stations of Kazakhstan, Russia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan (Baku, Neftyaniye Stones, Fort-Shevchenko, Makhachkala, Guvly-Mayak, Turkmenbashi, Kara-Bogaz-Gol) were processed (

http://www.caspcom.com/index.php?razd=sess&lang=1&sess=17&podsess=61). The actual data on Caspian Sea stations and posts are formed in a single database according to the International Agreements on Information Exchange of the Caspian Sea countries [

http://www.caspcom.com/index.php?razd=sess&lang=1&sess=17&podsess=61; https://tehranconvention.org]. Data from representative marine stations were used to calculate the background sea level. Further, it was interesting to forecast and analyze the Caspian Sea level in the future, considering climate change and anthropogenic load.

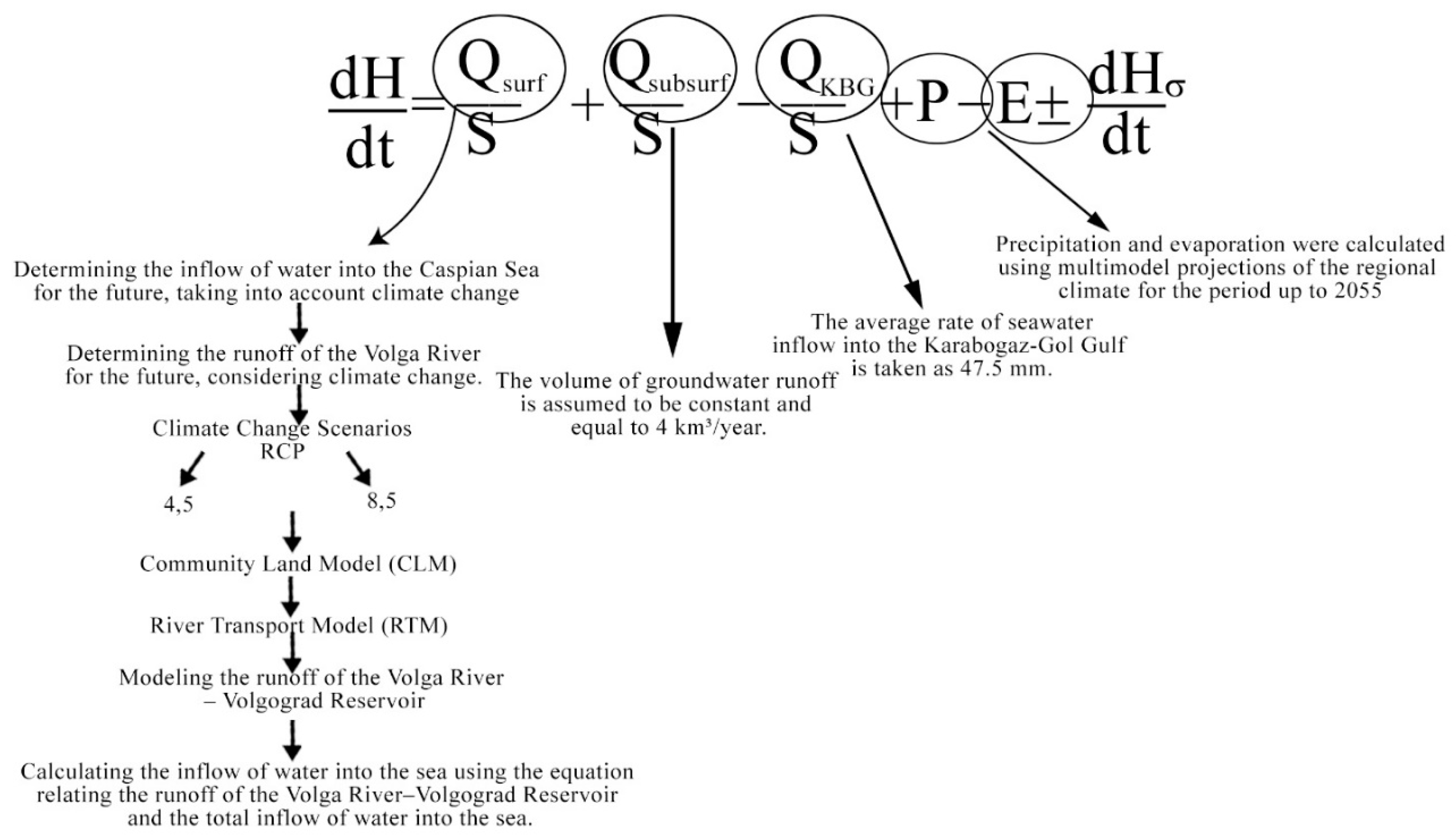

The sea level change for the future up to 2055 was determined using the Caspian Sea water balance equation, according to

Figure 2.

The level of the Caspian Sea, as a closed water body, is subject to significant multi-year, inter-annual and seasonal fluctuations. These level fluctuations belong to the type of volumetric fluctuations. They reflect changes in the volume of water masses in the sea basin. They have a relatively the same magnitude at any point in the sea, and they are usually slow, smooth. These fluctuations provide the backdrop against which short-term, sharp deformation fluctuations in sea level develop.

According to some geologists (Mazurov, 2007; Rychagov, 2000), the cause of the current unstable Caspian Sea level may be tectonic movements, the amount of bottom sediments, seismic deformations, as well as submarine unloading of groundwater or absorption of water by sub-bottom layers of the sea bed. However, modern movements on the Caspian coast do not exceed a few mm per year, and therefore cannot have a significant impact on sea level changes, as well as the balance of sedimentary sand-silt sedimentation, defined by values of 0.27-0.46 mm/year.

The Caspian Sea area is located in a tectonically active area and tectonic movements can lead to changes in coastlines, but according to studies (Varushchenko et al, 1987) the rates of level fluctuations are much higher than the rates of tectonic movements. They could not have a significant influence on the transgressions and regressions of the sea. A number of scientists (Andreev et al, 2010; Bukharitsin et al, 2020) suggest the dependence of the Caspian Sea level on solar activity. Supercentury periods of maximum solar activity increase the continentality of the climate in the steppe zone. This generates regression, while in regions of minimum activity continentality decreases.

Most scientists consider climatic changes and anthropogenic activities as the main causes of the Caspian Sea level fluctuations. They have a significant impact on the change of water balance characteristics.

3. Results & Discussion

Changes in climatic factors determine cyclical fluctuations in sea water volume and water level with durations ranging from 2-5 years to quasi-periods. For example, a large atmospheric-circulation anomaly covering the entire northern hemisphere led to a sharp decrease in the Caspian Sea level in the 1930s (by 1.82 m) (Water balance and level fluctuations in the Caspian Sea. Modeling and Forecasting, 2016). In the 70s, similar anticyclonic conditions developed - decreased humidity, reduced surface inflow, and increased evaporation from the sea area. This resulted in to water balance deficit by 1977 and sea level decrease by 0.7 m.

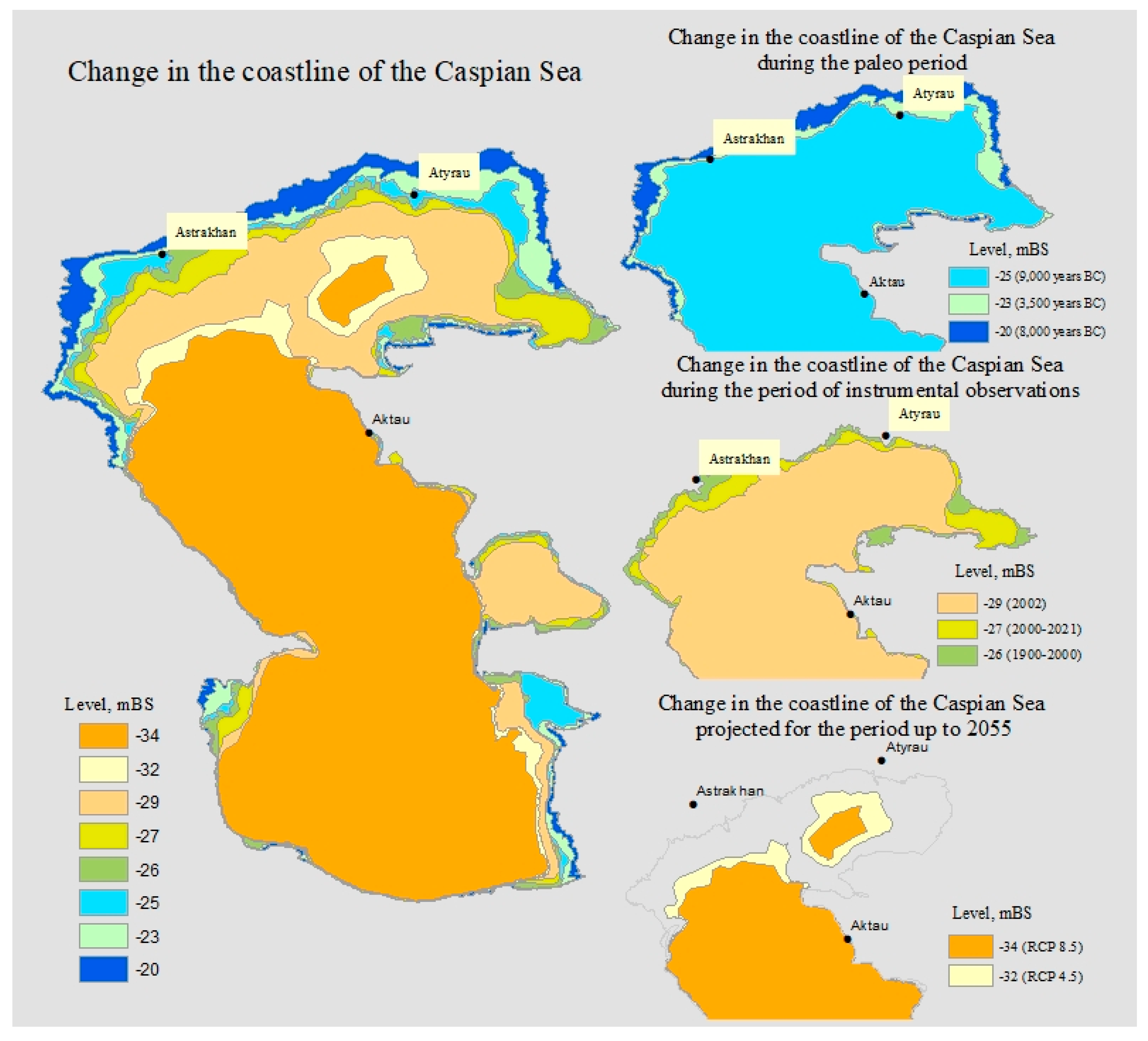

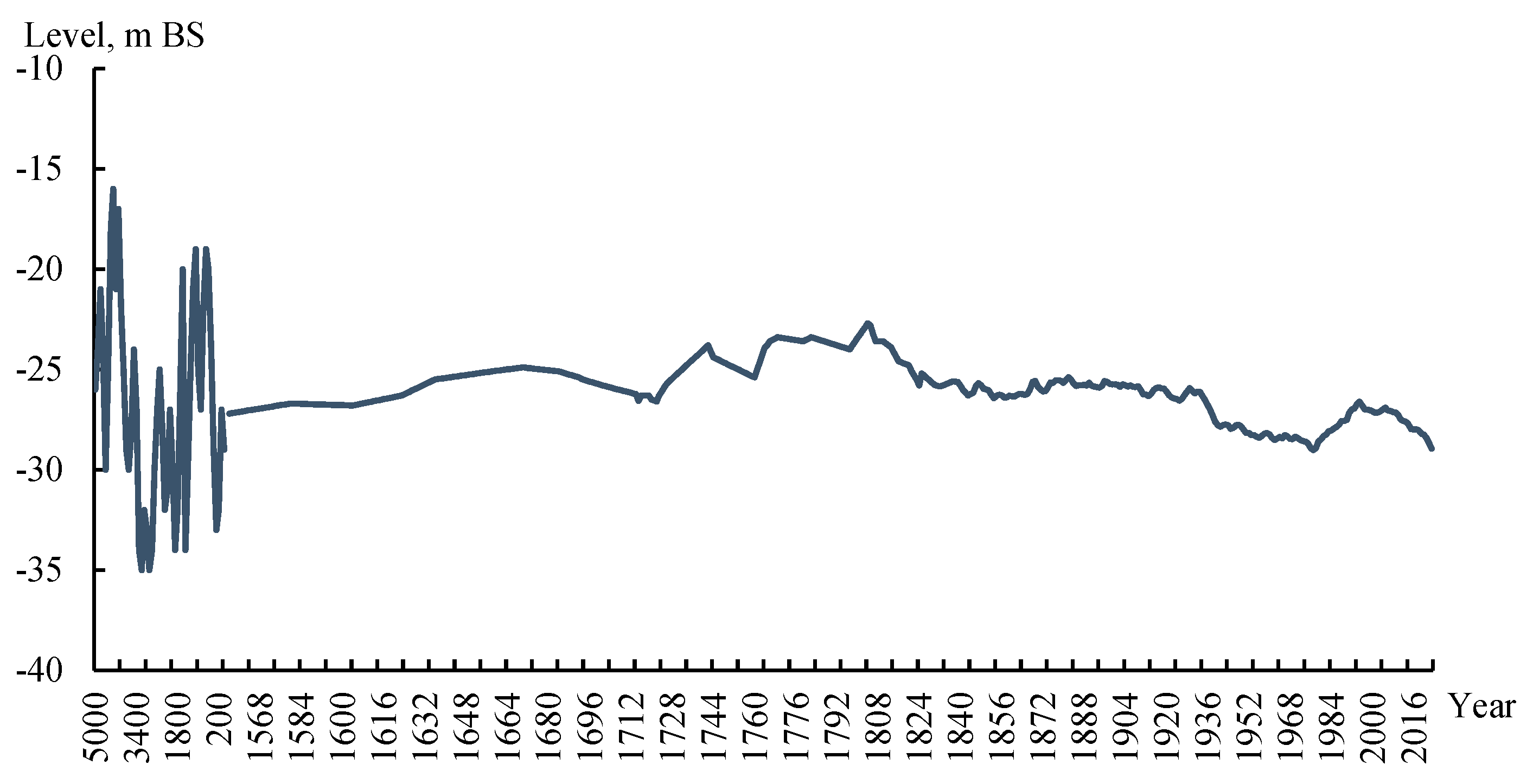

The present-day configuration of the Kazakhstan shores of the Caspian Sea was formed after the maximum of the Early Caspian transgression 6-3 thousand years ago. At that time, the coastline ran along the horizontal minus 22 m BS. Relief elements confirming this boundary are preserved in the low-lying northeastern part. According to some data (Berg, 1934), somewhat earlier (7 thousand years ago) the level of standing of the Early Caspian Sea reached the minus 20 m BS. At this level, the shore of the reservoir was located in the upper part of the modern Volga and Zhaiyk deltas, i.e. north of the Astrakhan and Atyrau cities (

Figure 3).

It is generally recognized that the curve of sea level fluctuations in the New Caspian time has a cyclic character, apparently, as before. The most reliable data on the range of fluctuations were obtained for the first and second millennia AD. At this time, archaeological and historical data were added to the traditional geochronological methods. In the 10th-13th centuries during the Derbent regression the level decreased to minus 33 meters. In the middle of the 17th century the sea level rose to minus 22.5 meters. The settlement founded in 1940, later Guryev, was located on the sea shore. Nowadays Atyrau city. Atyrau is 25-30 km away from the sea (

Figure 3). During the rest of the second millennium, sea level fluctuations occurred with a periodicity of 230-280 years relative to the mark of minus 26 m (Berg, 1934).

3.1. Altitudinal Position of Sea Level in Quaternary Time

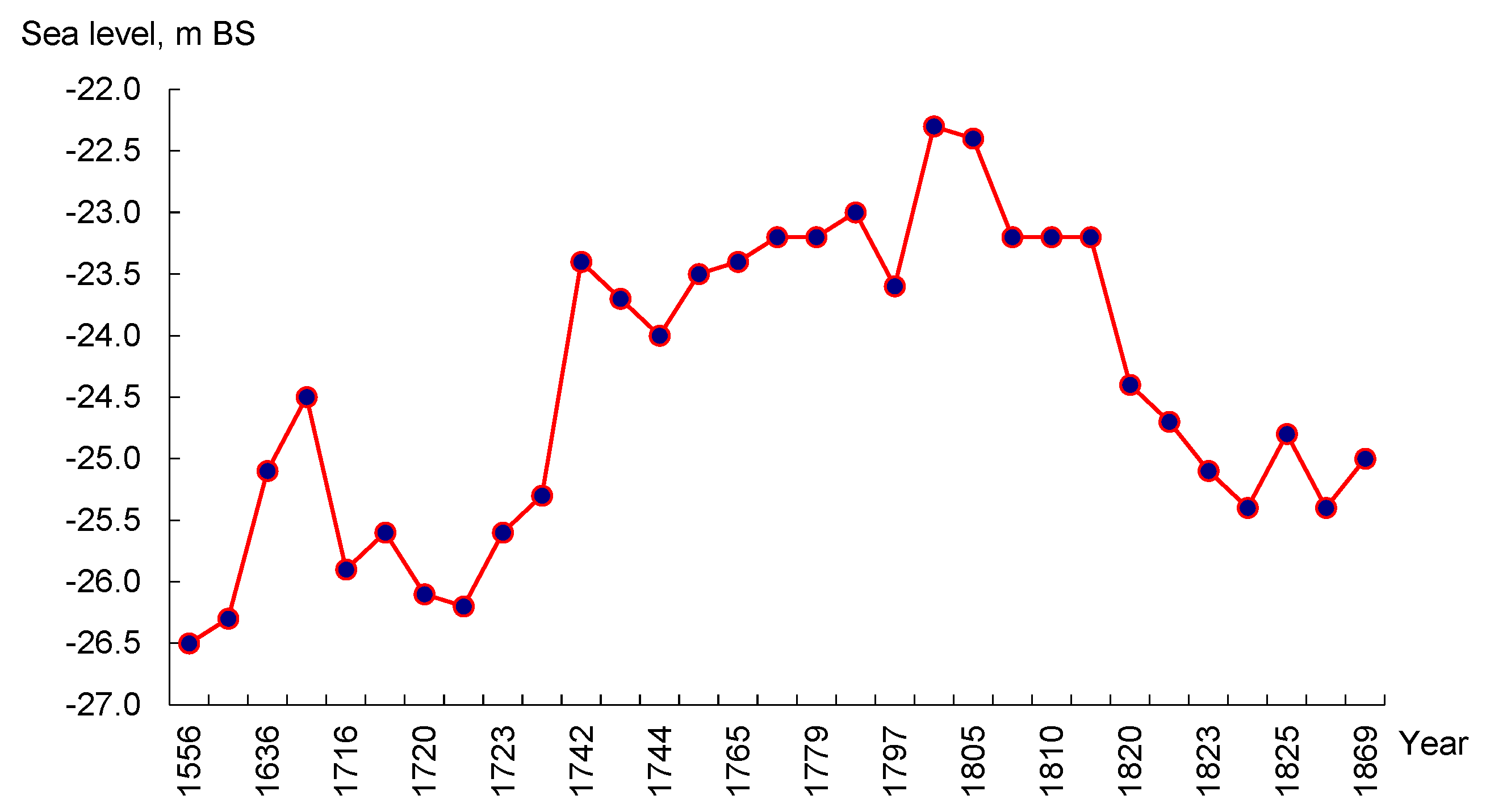

The most reliable data on Caspian Sea level fluctuations are available for the last 400-450 years.

Studies by a number of scientists (Berg, 1934; Apollov, 1956; Fedorov, 1957; Nikolaeva et al, 1962) show that in the middle of the 16th century the sea level was at minus 26.6 meters. In the following century the level rose to minus 24.5 meters. At the beginning of the 18th century, the level dropped again to minus 26 m. After this significant decrease, a period of high standing level began. By the beginning of the 19-th century (1805) the level reached minus 22.4 meters. Then the level began to decline again, and by 1825 it reached minus 24.8 m BS.

Figure 4 shows a graph of multi-year fluctuations in the level of the Caspian Sea, constructed according to the data of L.S. Berg, which are based on geological data.

A rather definite idea of the Caspian Sea level change in Quaternary time is contained in the works of P.V. Fedorov (Fedorov, 1957). Based on the results of his research, he was the first to characterize the altitudinal position of the sea level in different periods of its geological history.

The existing ideas about the Quaternary history of the level regime are presented in the monograph (Varuschenko et al, 1987).

The fact that sea water reached such high levels is evidenced by fossils of marine organisms, which are abundant on the coast at a considerable distance from the modern coastline (

Figure 5).

3.2. Changes in the Coastline of the Caspian Sea

It was noted above that the modern geomorphologic structure of Kazakhstan's Caspian shores and, first of all, their configuration was determined in the New Caspian time (7-10 thousand years ago). This was facilitated by the dynamics of tectonic elements of the platform cover, largely dependent on the structures of the consolidated basement. The main indicator of the inheritance of tectonic structures is especially clear in the Mangistau region (Atlas of Mangistau region, 2010).

In the lowland part of the Kazakhstan coast of the Caspian Sea, according to the peculiarities of the geomorphologic structure of the coastline, adjacent coastal land and underwater slope, the following are distinguished:

- -

Northern accumulative area from the eastern part of the Volga River delta to the eastern edge of the Zhaiyk River delta (delta banks - separate sub-areas);

- -

Northeastern area from the delta of the Zhaiyk River to the Bozashchi Peninsula, including Olikoltyk Bay and its continuation Kaidak Bay;

- -

area of the Bozashchi peninsula, the northern shore of which is formed by the Olikoltyk bay, the eastern shore by the Kaidak bay (sor), and the southern shore by the Mangyshlak bay and sor system.

The eastern upland shores are subdivided into:

- -

Tupkaragan-Aktau area of predominantly abrasion banks;

- -

Aktau region - Kenderli Bay, where accumulative and abrasion-accumulative shores prevail;

- -

distinct abrasion bank - escarpment of the Kenderli-Kayasai plateau up to the southern border of Kazakhstan.

The northern shore is about 230 km long and has the appearance of a weakly curved arc with a very indented outline of the land edge resembling a jagged saw. The underwater slope, which is more submerged in the west at the Volga avandelta, becomes shallow in the east. Artificial channels through the avandelta of the Zhaiyk River are necessary for navigation. Zhaiyk. There are numerous shoals and banks in the water area, as if continuing under water the accumulative capes of the coast. Reed thickets are widespread in the coastal shallows. The coastal land is characterized by a relatively narrow strip of Novocaspian formations, which are bounded from the north by the sands of a vast aeolian massif with the common name of Naryn. The sands are lumpy and lumpy-cellular predominantly fixed by vegetation. Only in the zone of the large sand rampart Menteke mobile sand forms prevail, as well as along the transportation routes Atyrau - Astrakhan. The formation of aeolian relief is associated with sandy sediments of the Late Khvalyn Sea and alluvial deposits of rivers of that time. In this coastal part of the Caspian Basin, the basement lies at a depth of 7-10 km and dips significantly both southward and northward toward the center of the basin. The Paleozoic cover contains a system of uplifts (Astrakhan, North Caspian, Guryev, and Biikzhal vaults), mainly carbonate platforms, which influence the distribution and size of salt structures (Tectonic map, 2003). The Martyshi, Kamyshitovy, Chernorechensky, Zhambaysky salt domes are known, which are reflected in the modern relief.

The northeastern shores frame the shallowest part of the Caspian Sea. On a considerable area of the water area the depth does not exceed 1 m. There are extensive shoals. On land, the flat, slightly sloping surface of the Novocaspian terrace reaches a width of many kilometers. Its edge is expressed by an abrasion ledge 0.5-0.8 m high, which in some places is densely dissected by small scour holes. In this part of the sea the most extensive surges and run-ups occur even in winds of average strength and stability. This circumstance required the creation of a system of coastal infrastructure protection structures, including dozens of kilometers of embankment (dyke) enclosing the Tengiz field with its plants and settlements.

This part of the Caspian Sea water area, extending far to the east, is confined to a large latitudinal trough, which is part of the Zavolzhsko-Tugarakchan trough system (Tectonic map, 2003). The trough is distinguished already in the basement of the depression, which in the axial part lies at depths of 10-14 km. Several carbonate uplifts of the Paleozoic cover are found there, the largest of which is the Tengiz-Kashagan uplift. The northern side of the trough is bounded by the Guryev and Biikzhal vaults, and the southern side by the Turan plate structures and the South Embene uplift of the Caspian Basin. The boundary of these two large structural elements is a discontinuous disturbance projected through the mouth of Olikoltyk Bay. The most extensive area of the same name, framed in the east by the Ustirt chinks, is a plain of late Novocaspian generation. At a sea level of minus 26.5 m it joins the water area, and when the sea level drops Olikoltyk turns into a sorghum. Sea waters through a system of narrow channels between the Durneva islands spread eastward along a relatively narrow channel (3-8 km) for a distance of up to 85 km and fill the sor, from which the Kaidak tract, which reaches a length of 150 km and a width of 7-10 km, flows to the south-southwest. The southern part of the Kaidak tract stretches rectilinearly at the base of the western Ustirt chink for 80 km, has steep sides and a depth of up to 20 meters. This indicates the neotectonic nature of the soron.

If Olikoltyk is located in the collision zone of platform structures of the North Ustyrt block (Koltyk trough) and the South Embinsky uplift. Bozashchi is structurally almost entirely within the Turan plate. Although in its lowland accumulative relief it is identical to the Pre-Caspian lowland. Its northern and western shores are typically marshy, flooded during surges. It is composed of silty and fine-grained sands. Soils are solonchak, in the west swampy, especially in detached lagoons. The eastern shore is the side of the Kaidak valley (sora), in the distinct escarpment of which Khvalyn deposits are exposed. A notable feature of the relief of Bozashcha, in addition to a number of aeolian massifs, is Ulkensor. A significant part of the bottom of its area (~ 2000 km2) is below sea level, which forces to protect oil fields with dikes.

The strictly latitudinal Mangystau Bay delimits the lowland and upland coasts. Its northern accumulative upland shore belongs to Bozashchi, and its steep, rugged abrasion-accumulative shore belongs to the Tupkaragan Peninsula.

The structure of the upland shores of the Kazakhstan Caspian Sea is characterized by great complexity. Structural and geomorphologic features of more or less large bays correspond to deflections, and capes reflect uplifts (Sydykov et al, 1995).

Consistent accumulation of the sum of geological data proved the different ages of the folded basement of the region and made it possible to define the boundaries of areas with different consolidation of the Earth's crust. Against this background, regional structural-tectonic elements are distinguished in the sedimentary platform complex, within which smaller, second and third order, positive and negative structures are established. The outline of the coastline is influenced by both large and localized uplifts and troughs, the boundaries of which can be determined (Atlas of Mangistau region, 2010).

Tupkaragan-Aktau coastal area. The Tupkaragan peninsula is deeply penetrating into the sea water area. It is confined to the western part of the Central Mangistau system of Cimmerian consolidation uplifts. Further to the WNW, this system forms the underwater Mangyshlak sill separating the northern and middle parts of the Caspian Sea. The surface of the Tupkaragan Plateau, a flat plain armored with Sarmat limestones, is little disturbed, as the total magnitude of vertical neotectonic movements does not exceed 100 meters. In the east, such movements reached 500 and more meters, forming the low-lying Karatau massif.

3.3. Multiyear and Interannual Sea Level Fluctuations over the Period of Instrumental Observations

Systematic observations of the level of the Caspian Sea began in 1830. The first attempt of refined observations of the Caspian Sea level fluctuations was made by E. Lenz. He established two permanent level marks in the vicinity of Baku. Since February 1, 1837 observations of level fluctuations in the Baku Bay were carried out at the footpost against the Customs Exchange. In 1856 N.M. Filippov installed a new footstick. This marked the beginning of systematic observations of the sea level. Since 1866 the water gauging post was located in the Baku military port. After the opening of the Baku water gauging post, the water gauging posts in Boast (Volga delta) started to operate since 1876, in Astrakhan since 1881, on Biryuchya Spit (Volga delta) since 1892, and since 1900 the water gauging post in the port of Makhachkala has been in operation (Hydrological Handbook of the Seas of the USSR, 1936).

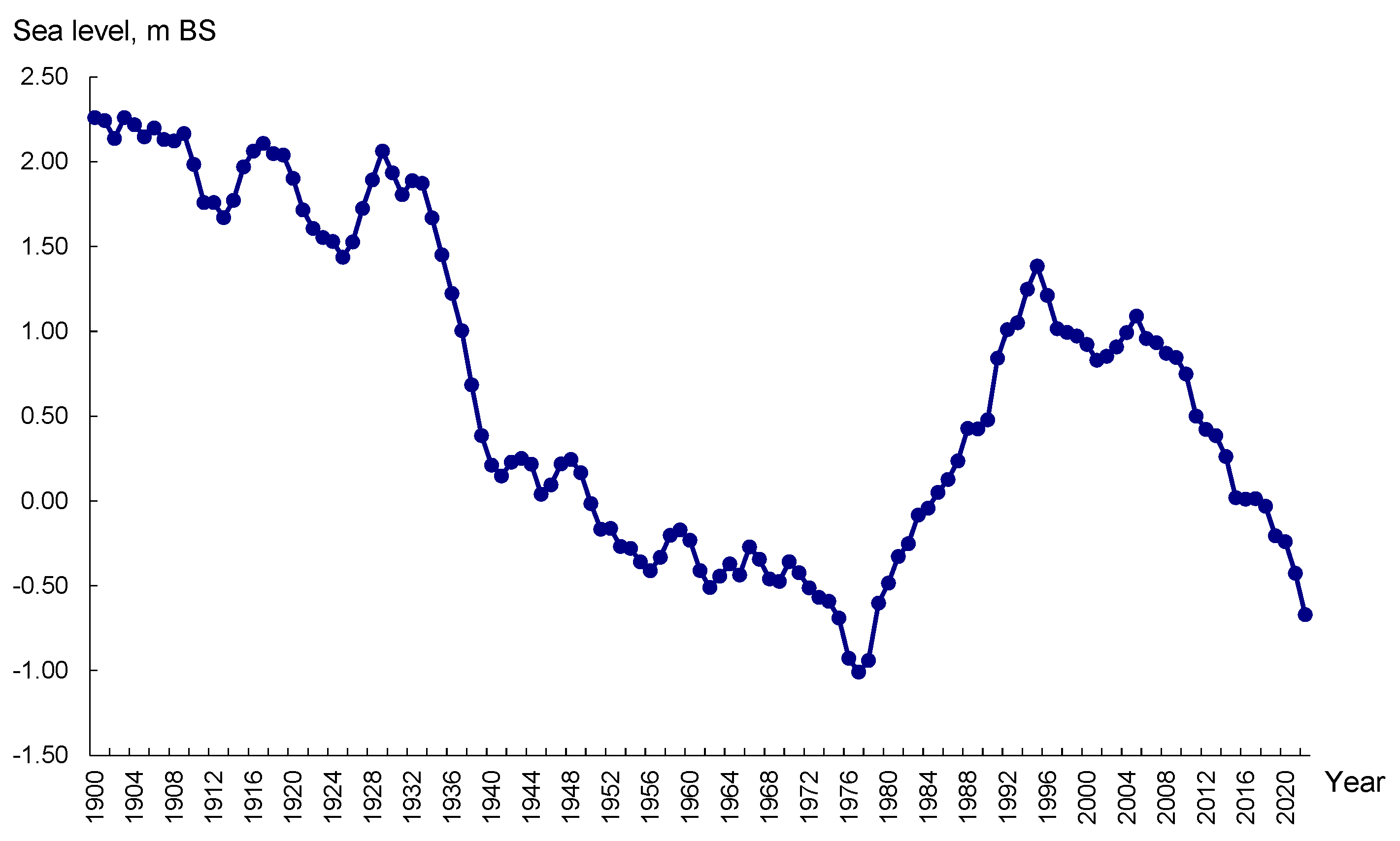

The most reliable data on the level of the Caspian Sea have been available since 1900 from the gauging stations in Makhachkala, Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi), Fort-Shevchenko, and Baku (

Figure 6).

From the beginning of instrumental observations until the 20th century, the Caspian Sea level fluctuated insignificantly. On average, the fluctuations were around the mark of minus 25.8 m BS. In the last century, the level of the Caspian Sea mainly decreased almost until the end of the 1970s. The total continuous level fall observed between 1930 and 1977 was 3.2 m. The average intensity of the level fall was about 4 cm per year. In 1977 the sea level reached the lowest mark (minus 29.01 m BS) not only for the whole period of instrumental observations, but also for the last 500 years. During this period, the range of mean sea level fluctuations amounted to 7 m. (

Figure 7)

At the beginning of the 20th century, sea level changes were insignificant. The magnitude of the level decrease for this period was 0.34 m, with an average level mark of minus 26.2 m BS. Starting from 1930, this relatively stable sea level position was replaced by a sharp decrease (with an intensity of up to 16-20 cm per year). During the period from 1930 to 1941 the level decreased by 1.82 m. Then, until the 60s, some stabilization of the level at about -28.4 m BS was observed. In 1970, a new decline in the level of the Caspian Sea began. The total drop in the average annual level of the Caspian Sea from 1929 to 1977 amounted to 3.2 meters. The drop in the level was due to the fact that since the mid-1930s intensive water management construction began on the rivers of the Caspian basin. This became most noticeable in the 50s. By the early 1970s, practically all major rivers in the basin were regulated. As a result, the volume of river runoff has decreased and its intra-annual distribution has changed. As a consequence, the area of the sea water surface decreased. According to R.E. Nikonova (Nikonova, 2008), the reduction of the area amounted to about 50 thousand km

2. The shallow-water Kaidak and Mertvyi Kultuk (Komsomolets) bays dried up and turned into sorries. In the northeastern part of the Northern Caspian, the coastline retreated by 120-140 km. The lowering of the level caused great complications in the work of the Caspian coast ports and sharply worsened shipping conditions, especially in the Northern Caspian. There was a reformation of the coasts and desertification of part of the territory, which caused a decrease in the groundwater level. The salinity of the Northern Caspian waters has increased, which has affected the state of the food base of semi-navigable and sturgeon fish and led to a decrease in the biomass of most bottom organisms. In this connection, the problem of the Caspian Sea level has attracted much attention in the 20th century. Climate change and human economic activity in the Volga River basin were the main factors contributing to this decline (Hydrometeorology and hydrochemistry of the seas of the USSR, 1992). Since 1978, the present-day intensive rise in the Caspian Sea level began. It continued for 18 years (1978-1995). During this time, the sea level rose by 2.5 meters and reached minus 26.6 meters by the beginning of 1996. The average intensity of sea level rise during this period was about 14 cm per year, and in some years - up to 36 cm. The most intense sea level rise was observed in 1979 (0.31 m), in 1990 (0.36 m), in 1991 (0.29 m) and in 1994 (0.28 m) (Mikhailov et al, 1993). This rise in the level of the Caspian Sea is the longest in 170 years. (

Figure 7)

In 1995 the sea level rise slowed down, and in 1996 it decreased mainly due to low water levels in the Volga basin. In the second quarter of 1996, the discharge to the downstream of the Volgograd HPP amounted to only 62 km3. In the years of sea level rise the discharge amounted to 110...140 km3. In 1997, water discharge into the lower reach of Volgogradskaya HPP amounted to about 80 km3. The average sea level in 1997 was 15...20 cm below the level observed in 1996. (Golubtsov et al, 1997). From 1997 to 2001, the average annual sea level decreased by 19 cm. In 2001, it reached the mark of minus 27.17 m. Then there was a tendency to sea level rise. The average sea level in 2005 amounted to minus 26.91 m of the Baltic system.

Sea level rise has led to new problems related to waterlogging and flooding of coastal territories. According to research by R.E. Nikonova (Nikonova, 2008), the area of flooded territories amounted to 35-40 thousand km2 as a result of sea level rise. In some areas, the coastline extended 25-50 km. About 100,000 people were resettled from flooded and submerged areas and industrial facilities were relocated.

As a result of the background water level rise and flooding of a large area of the coast, hydrological conditions in the coastal zone of the Kazakhstan part of the Northern Caspian Sea have changed. The area from Kurmangazy village (in the west) to Zhanbai settlement (in the east) was significantly flooded. In their works Sydykov J.S. and Golubtsov V.V. note that this led to the underflow of underground flow directed to the sea. As a result, small water bodies flooded with salt water, as well as solonchaks and marshy areas scattered among themselves and having no open connection with the sea were formed. Water exchange in groundwater has slowed down, causing an increase in its salinity. As a result of flooding of large areas (up to 10-50 km) between Zhanbai settlement and the vicinity of Atyrau city there was an outflow of sea water into adjacent depressions. Formation of such depressions resulted in reduction of groundwater migration paths to the sea and increase of its level. One of such depressions is located in the Ural River delta near the Peshnoy post. At present, the area of this depression as well as the depth of groundwater began to decrease. The process of groundwater rises also took place in the vicinity of Atyrau. In many areas of the city groundwater levels reached critical mark. This led to water accumulation in basements and flooding of building foundations. Additionally, negative processes of land flooding in the city were exacerbated by the reduced drainage effect of water in the Ural River channel. As a result of the rising sea level, infrastructure in the coastal part of Aktau was damaged. Hundreds of kilometers of paved and unpaved roads were affected. Oil extraction and fishing enterprises suffered due to the rising sea level. The increase in sea level to minus 26.5 m BS (the level of 1995) created conditions for the free ingress of water into river deltas, as well as causing backflow of river discharge and an increase in flooded areas during spring floods (Sydykov et al, 1995).

Since 2006, the Caspian Sea level has shown a stable downward trend. The average rate of decline is about 10 cm per year, but in certain years, it exceeded 15 cm: 25 cm in 2011, 24 cm in 2015, 17 cm in 2019, 21 cm in 2021, and 24 cm in 2022. Since 2011, the background sea level has been below the long-term average of minus 27.35 m BS (1900-2023).

In 2022 and 2023, the level dropped below minus 28.5 m BS. In 2023, it reached minus 28.67 m. A decrease in sea level to minus 28.5 m, based on the history of the Caspian Sea, is critical for both its ecosystem and maritime economy. This drop has significantly complicated economic activities in the coastal and shallow-water zones. The most vulnerable areas are the channels, which require dredging to function effectively. On the other hand, costs associated with combating coastal erosion may be reduced.

Such fluctuations in sea level have raised many questions, the most important of which are flood protection and prevention of marine water intrusion. To address these issues, it is necessary to determine the causes of sea level decline and rise, study its water balance, and develop a scientifically grounded forecast.

3.4. Assessment of Potential Changes in the Caspian Sea Level Until 2055

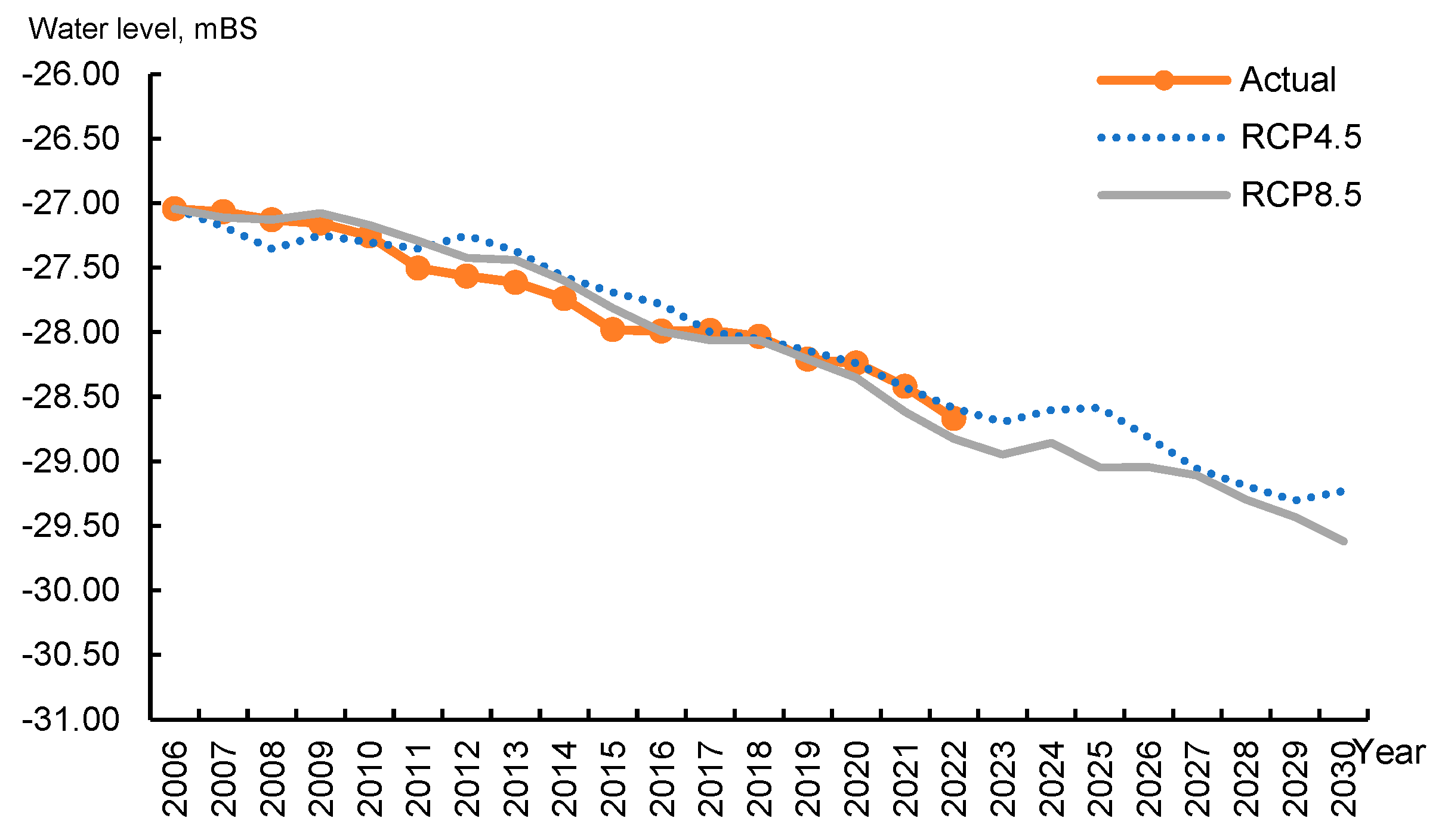

The assessment of potential changes in the Caspian Sea level was conducted based on identifying the relationships between the components of the water balance of the Caspian Sea. The calculation of the Caspian Sea level for the future was based on the water balance equation (Water Balance and Fluctuations of the Caspian Sea Level. Modeling and Forecasting, 2016). Key water balance characteristics, such as river inflow, evaporation, and precipitation, were calculated for the outlook until 2055.

For the long-term perspective, the role of these characteristics can be evaluated according to specific climate change and water consumption scenarios in the basin. This study utilized results from the fifth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5), which were used to prepare the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/). Calculations were based on the two most well-researched future climate scenarios: RCP4.5 – a moderate and fairly likely scenario, and RCP8.5 – the worst-case scenario for greenhouse gas concentration growth. This scenario assumes that the radiative forcing of the underlying surface reaches 8.5 W/m² and that greenhouse gas concentrations do not stabilize throughout the 21-st century.

One of the main factors affecting fluctuations in the Caspian Sea level is river discharge (with the Volga River contributing the most) and visible evaporation.

The assessment of potential changes in the Volga River discharge was conducted using modeling results from the Community Land Model and its river transport module (RTM) to route the total water discharge to oceans or seas (Branstetter et al., 1999; Branstetter, 2001).

The assessment of the total river inflow to the Caspian Sea was based on the identified relationship between total inflow and discharges from the Volgograd Hydroelectric Power Station, which are starting points for determining inflow to the Caspian Sea from the Volga-Kama basin (Ivkina et al., 2022). Data processing of river discharge projections for the Volgograd Reservoir and their visualization were performed using the Integrated Data Viewer (IDV) software. The results indicated that the inflow of water to the Caspian Sea until 2055 does not exhibit a clear trend.

Calculations of precipitation and evaporation in the Caspian region were also carried out for the two selected climate scenarios. Visible evaporation was calculated as the difference between precipitation and evaporation. The calculations showed that evaporation from the Caspian Sea will significantly increase by 2055, which is explained by the projected rise in air temperature (Ivkina et al., 2022).

Water losses in the lower reaches of the Volga and Zhaik (Ural) rivers are essential for calculating the water balance of the Caspian Sea. Therefore, a correction for losses in the river deltas was included in the modeled values of river inflow to the Caspian Sea.

One of the outflow components in the water balance of the Caspian Sea is the discharge of seawater into the Karabogazgol Bay. The average outflow based on data from Rosgidromet was incorporated into the calculations and amounted to 47.5 mm. Groundwater inflow to the Caspian Sea is the least studied component of the water balance. Most researchers believe that an average of about 3-5 km³/year of groundwater enters the sea (Water Balance and Fluctuations of the Caspian Sea Level. Modeling and Forecasting, 2016). Therefore, for the water balance calculation of the Caspian Sea, the volume of groundwater discharge was assumed to be constant at 4 km³/year. The examination sample used was the period from 2006 to 2022.

As shown in

Figure 8, the level of the Caspian Sea has a stable downward trend, particularly evident in the second third of the 21st century. According to the RCP4.5 scenario, the Caspian Sea level may drop to minus 32.6 m BS by 2055. Under the more pessimistic RCP8.5 scenario, the level could fall below minus 34 m BS.

Figure 9 presents the combined trend of the Caspian Sea level.

Thus, by 2055, the sea level may decrease by more than 4 and 5 meters, respectively, according to the climate scenarios. Such a decline in level will lead to a significant reduction in the area of the Caspian Sea (

Figure 3) and the near-complete disappearance of its northern shallow region.

4. Conclusions

The level of the Caspian Sea has varied significantly over an extended period (from paleo times to the present). Over the last 5,000 years BCE, the maximum recorded level of the Caspian Sea was minus 16 meters below sea level (BSL), while the minimum level dropped to minus 34.5 meters BSL. This era was characterized by relatively high but unstable moisture conditions in the Caspian Sea basin. This instability caused the sea level to rise significantly above the current level and then fall well below it.

It's important to understand that determining sea level over such a distant period is inevitably subject to inaccuracies, influenced by storm waves and oscillations in water level that affect the height of accumulation and erosion features forming along the coastline.

In the last 200-400 years (still before the advent of instrumental measurements), the accuracy and reliability of level determinations improved, as geomorphological methods were supplemented by historical data from literary sources. During this period, the sea level fluctuated between minus 22.7 meters BSL and minus 27.2 meters BSL.

Reliable measurements began in 1900. Since then, the level of the Caspian Sea has ranged from minus 25.74 meters BSL to minus 29.01 meters BSL, with the lowest level (minus 29.01 meters BSL) recorded in 1977. In 2023, the level approached this historical low, measuring minus 28.95 meters BSL. Since 1900, there have been periods of both decline and rise in the level.

The changes in the Caspian Sea level during this period have been influenced more by anthropogenic factors than climatic ones. Since the mid-20th century, active construction of reservoirs and dams on the main rivers flowing into the Caspian Sea (such as the Volga and Ural) began. Additionally, oil field development in the northern Caspian started. From 2005 onwards, the level has consistently decreased from minus 26.91 meters BSL to minus 28.95 meters BSL, which is attributed to climate change leading to warming. Evaporation from the sea surface has increased, while precipitation has decreased.

Starting in 2024, we have projected changes in the level of the Caspian Sea up to 2055. This forecast can be used as a guideline. According to the projection, the level of the Caspian Sea will continue to decline, reaching minus 34.17 meters BSL (under the RCP 8.5 climate scenario) and minus 32.59 meters BSL (under the RCP 4.5 climate scenario) by 2055. It is important to note that the minimum level forecasted for 2055 has already been observed in the historical changes of the Caspian Sea levels.