Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

2.2. Animal Groups

2.3. Behavioral Tests

2.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) of Cytokines

2.7. Cell Culture of Primary Oligodendrocytes and Drug Treatments

2.8. Cell Culture of OLN-93 Cell Line

2.9. CCK-8 Assay

2.10. Assessment of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2.11. Detection of ROS

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

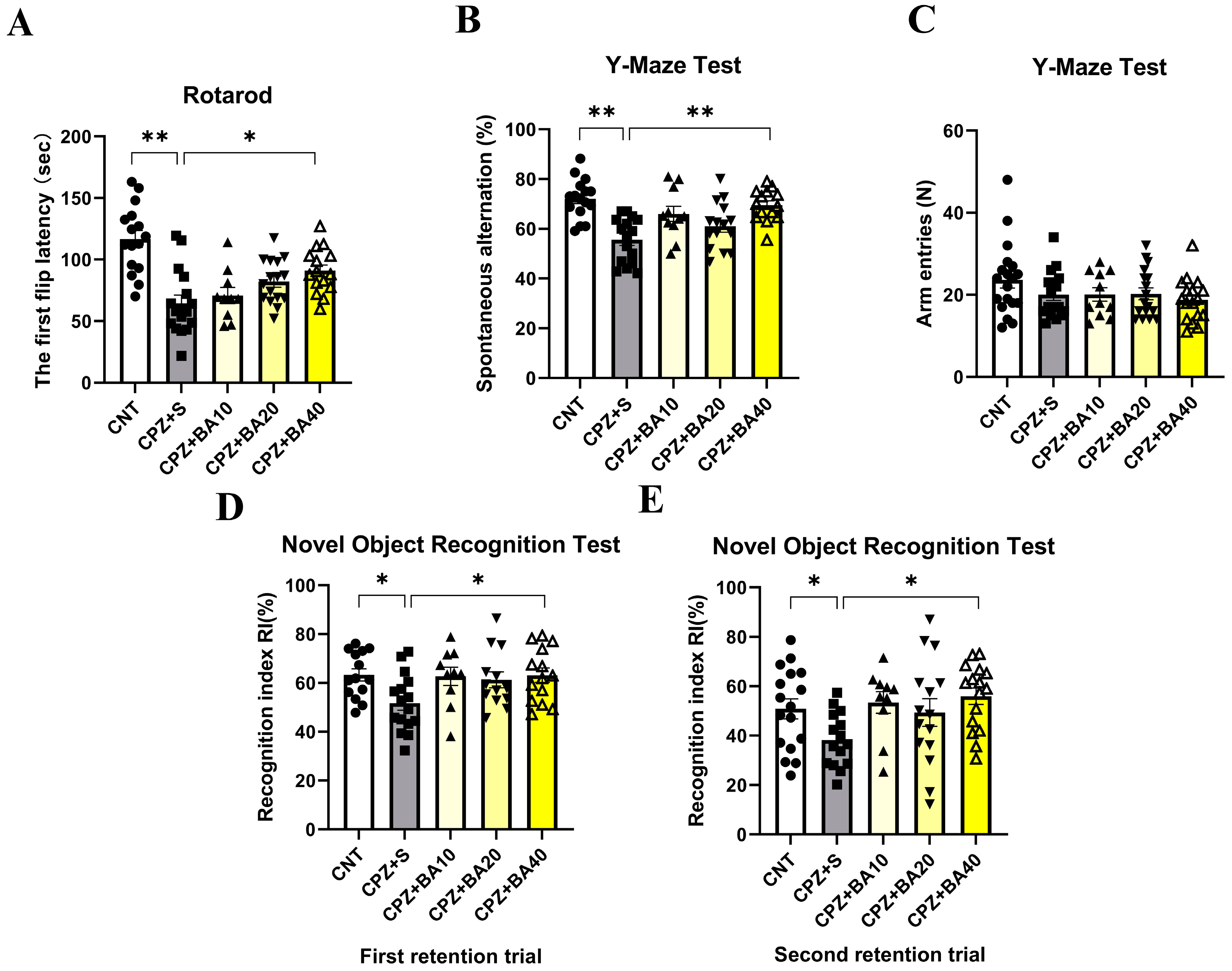

3.1. Baicalein Improved Motor and Cognitive Impairment in Cuprizone-Exposed Mice

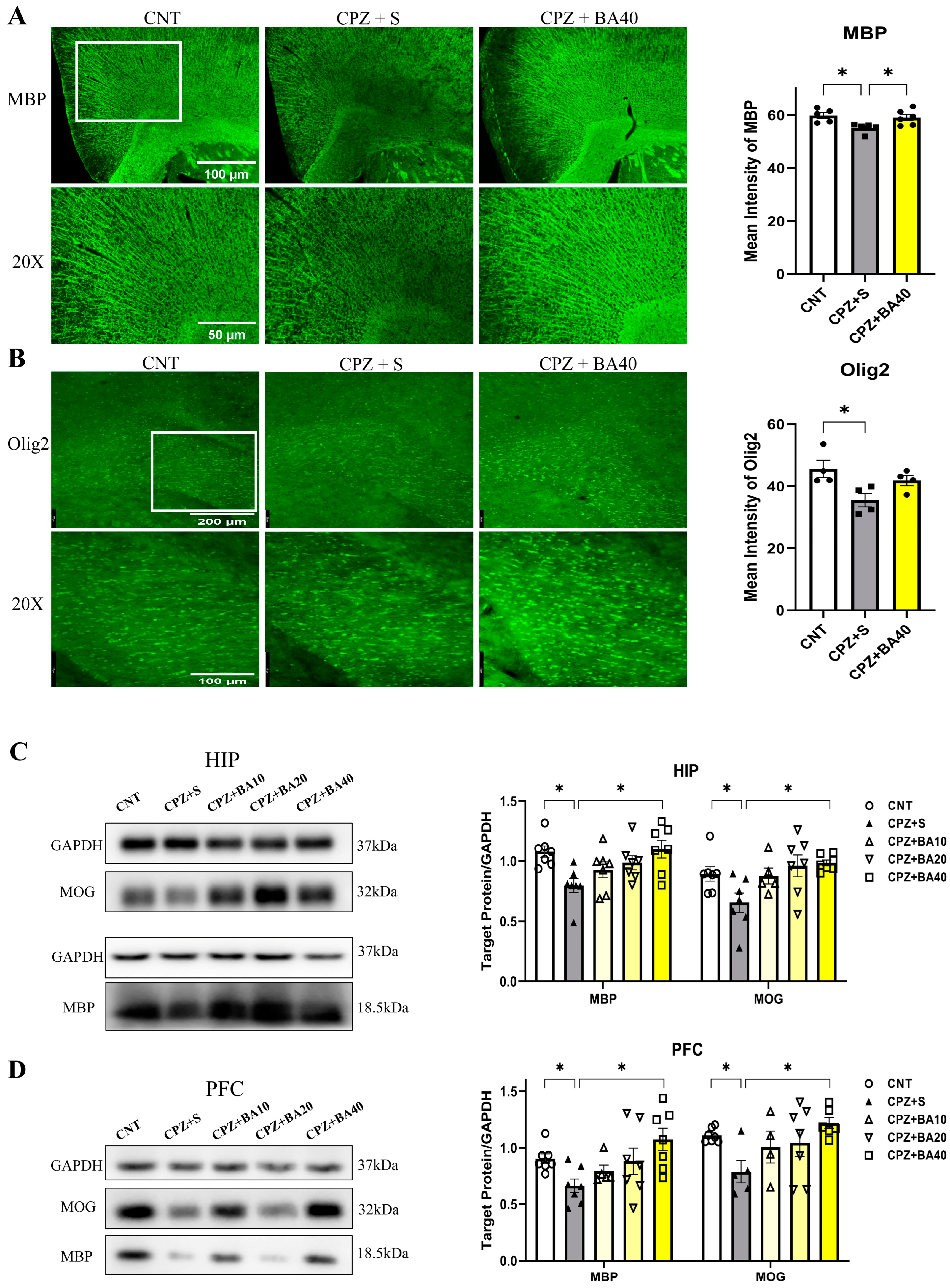

3.2. Baicalein Promoted Remyelination following CPZ-induced Demyelination in Mice

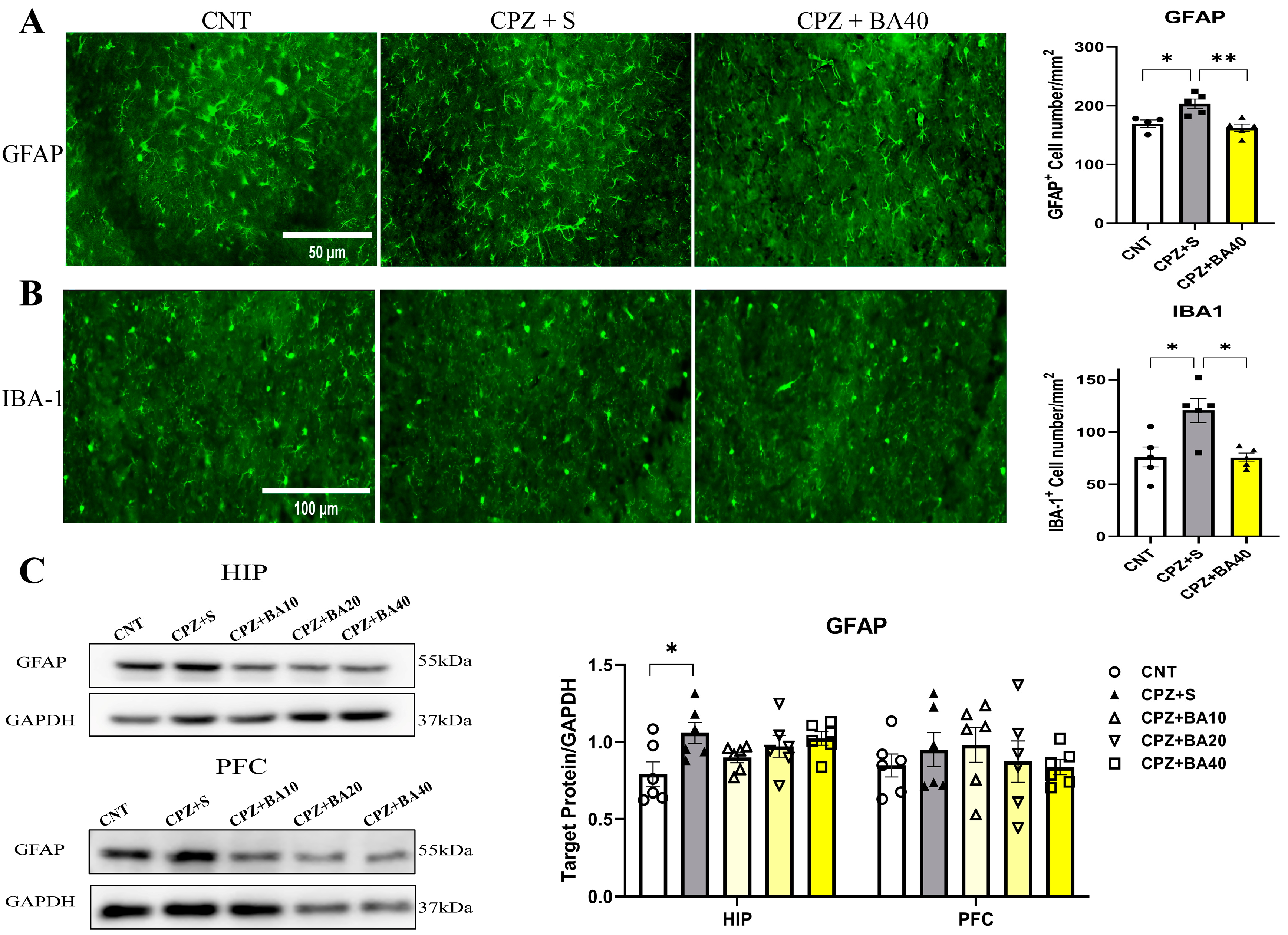

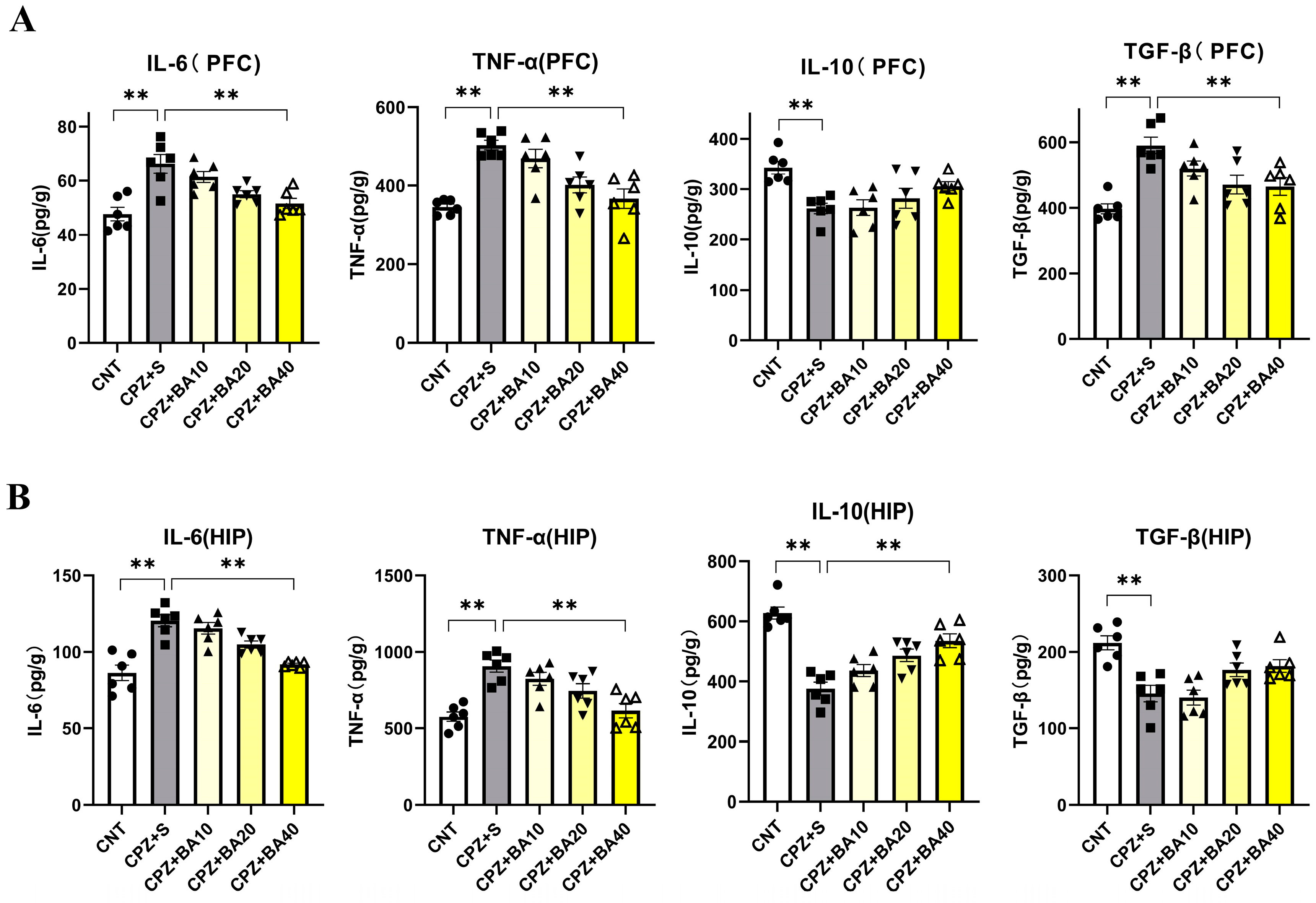

3.3. Baicalein Suppressed Neuroinflammation in Cuprizone-Exposed Mice

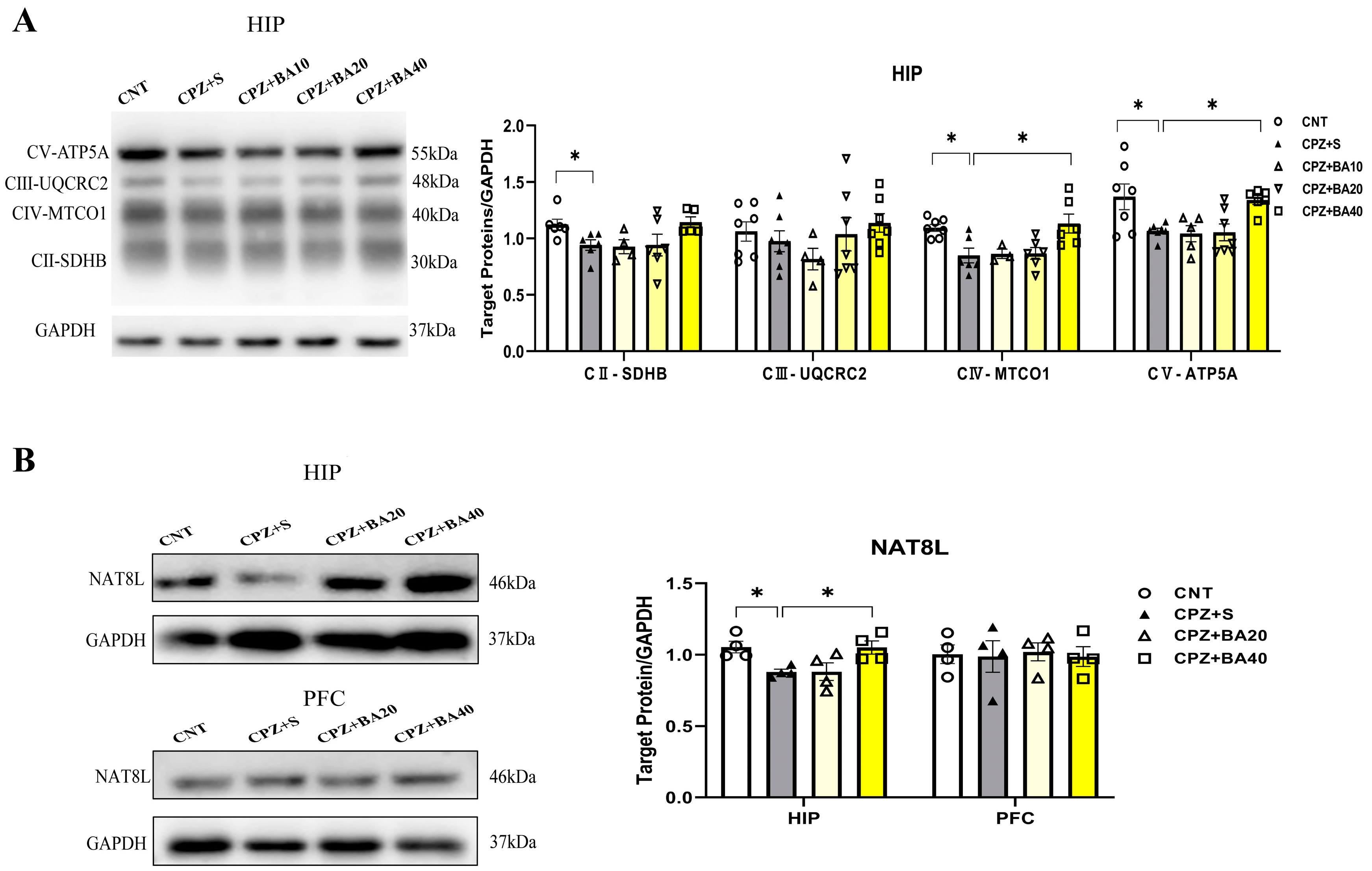

3.4. Baicalein Improved Mitochondrial Dysfunction in CPZ-Exposed Mice

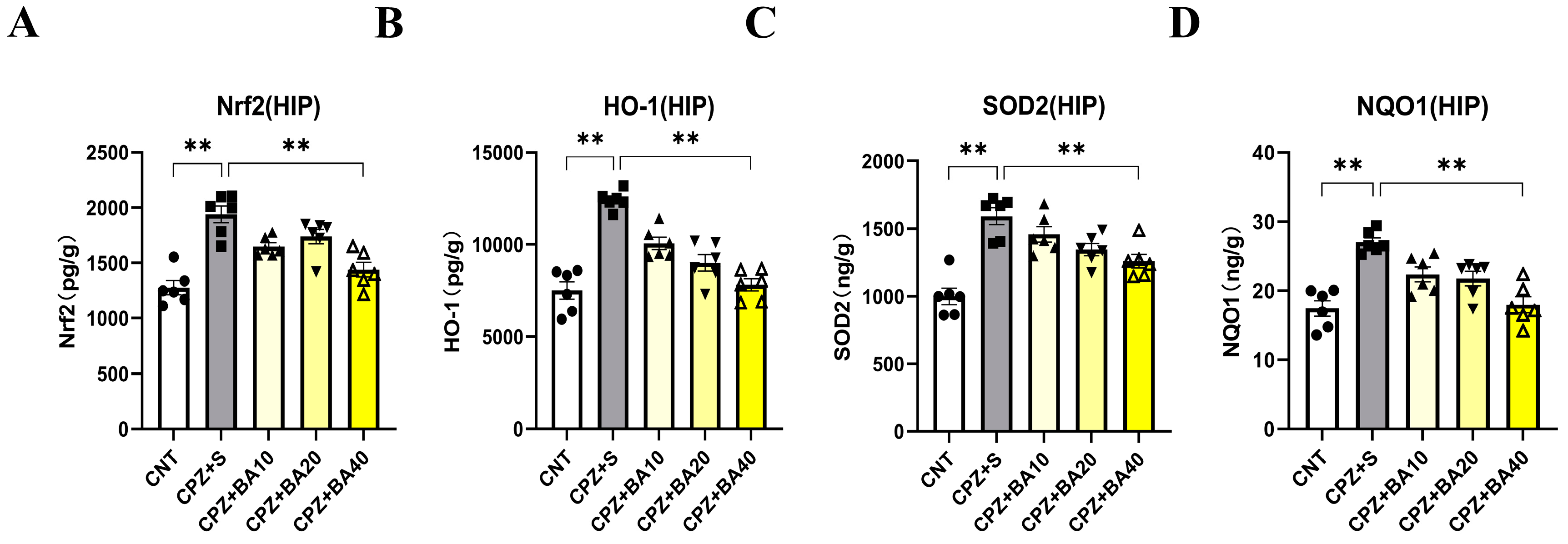

3.5. Baicalein Regulated the NRF2 Redox Pathway in CPZ-Exposed Mice

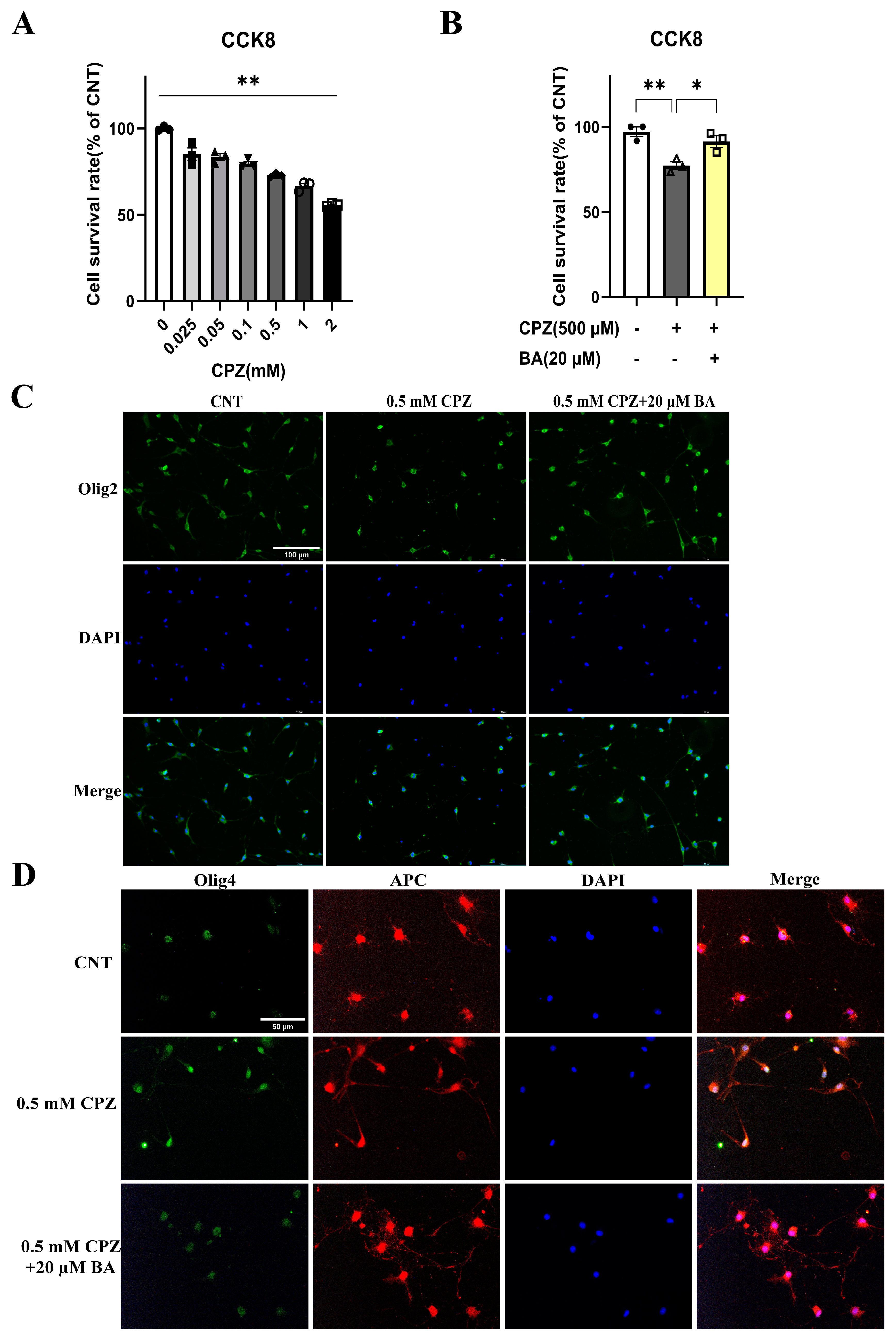

3.6. Baicalein Protected Against the Inhibitory Effects of CPZ on the Development of Cultured OL Lineage Cells

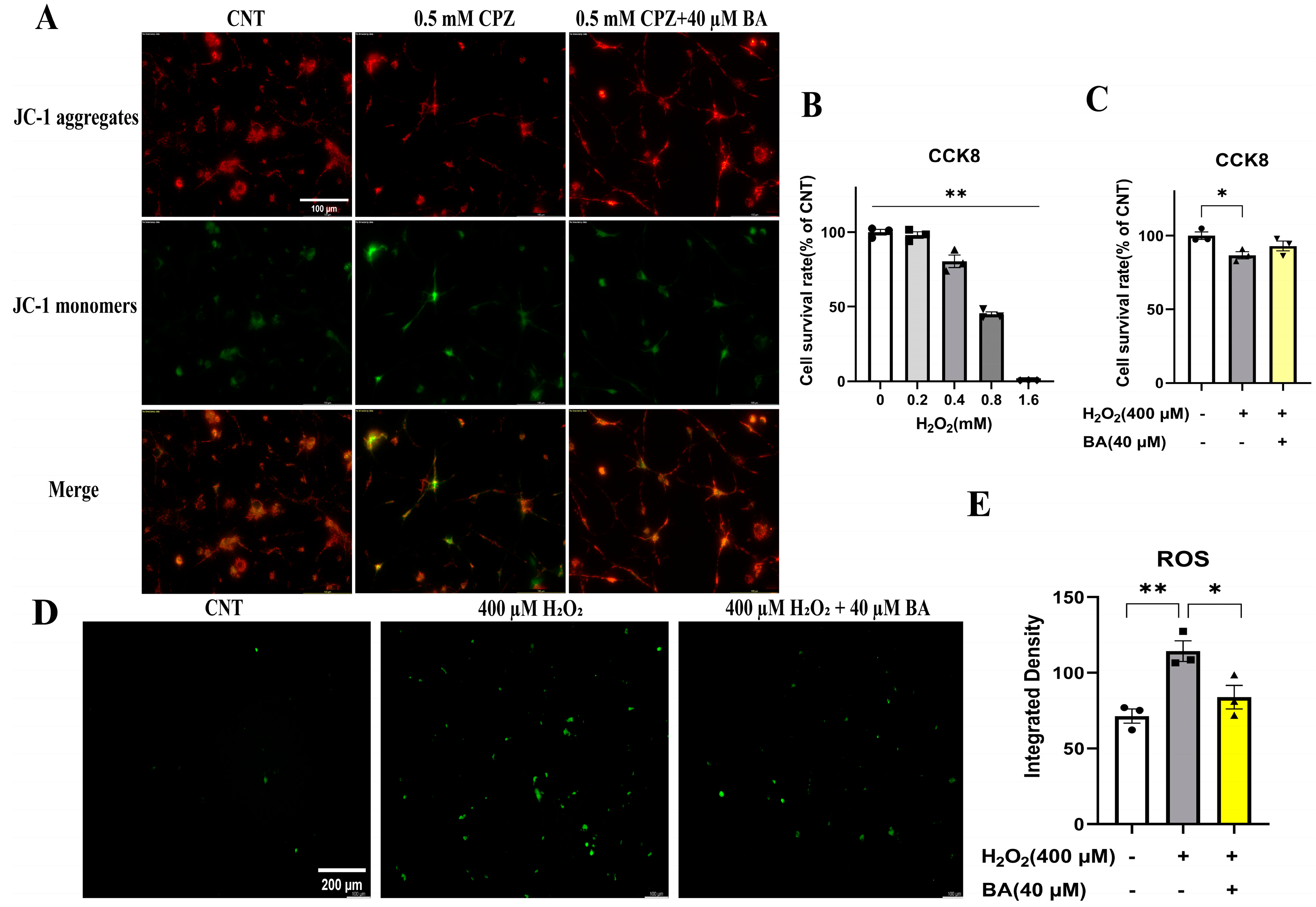

3.7. Baicalein Protected Cultured OLs and OLN-93 Cells against the Toxic Effects of CPZ on Mitochondria of the Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement:All experimental protocols involving animals in this study received approval by the Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Number: wydw2025-0209) and were carried out according to the institutional and ARRIVE guidelines.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Tobore, T.O. Towards a comprehensive etiopathogenetic and patho-- theory of multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020, 130, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.A.-O.; Engler, J.A.-O.; Friese, M.A.-O. The neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25(7), 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Exploring the Etiological Links behind Neuro-degenerative Diseases: Inflammatory Cytokines and Bioactive Kynurenines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, A.; Li, Y.; Claflin, S.B.; van der Mei, I.; Taylor, B.V. Role of environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corthay, A. A Three-cell Model for Activation of Naïve T Helper Cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2006, 64, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiela, D.; Chinnery, P.F. Mitochondria in neuroinflammation – Multiple sclerosis (MS), leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) and LHON-MS. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, T.; Biniecka, M.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. Hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 125, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J.; Stromsnes, K. Oxidative stress and inflammation: From mechanisms to therapeutic approaches. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maged, A.E.-S.; Gad, A.M.; Rashed, L.A.; Azab, S.S.; Mohamed, E.A.; Awad, A.S. Repurposing of secukinumab as neuroprotective in cuprizone-induced multiple sclerosis experimental model via inhibition of oxidative, inflammatory, and neurodegenerative signaling. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 3291–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirngibl, M.; Assinck, P.; Sizov, A.; Caprariello, A.V.; Plemel, J.R. Oligodendrocyte death and myelin loss in the cuprizone model: an updated overview of the intrinsic and extrinsic causes of cuprizone demyelination. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorile, A.; Ferretta, A.; Ruggieri, M.; Paolicelli, D.; Lattanzio, P.; Trojano, M.; De Rasmo, D. Mitochondria, oxidative stress, cAMP signalling and apoptosis: A crossroads in lymphocytes of multiple sclerosis, a possible role of nutraceutics. Antioxidants 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muguruza, E.; Matute, C. Alterations of oligodendrocyte and myelin energy metabolism in multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Deng, M.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Hu, S.; Xu, H. Differential susceptibility and vulnerability of brain cells in C57BL/6 mouse to mitochondrial dysfunction induced by short-term cuprizone exposure. Front. Neuroanat. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, R.; Tong, Y.; Chen, P.; Shen, Y.; Miao, S.; Liu, X. Neuroprotection by dihydrotestosterone in LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ambrosi, N.; Cozzolino, M.; Carrì, M.T. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Role of redox (dys) regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paty, D.W.; Li, D.K.B. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1993, 43, 662–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermel Ra Fau - Inglese, M.; Inglese, M. Neurodegeneration and inflammation in MS: the eye teaches us about the storm. Neurology 2012, 80, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, C.H. Anti-myelin antibodies in multiple sclerosis: clinically useful? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2006, 77, 712–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudick, R.A.; Stuart Wh Fau - Calabresi, P.A.; Calabresi Pa Fau - Confavreux, C.; Confavreux C Fau - Galetta, S.L.; Galetta Sl Fau - Radue, E.-W.; Radue Ew Fau - Lublin, F.D.; Lublin Fd Fau - Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Weinstock-Guttman B Fau - Wynn, D.R.; Wynn Dr Fau - Lynn, F.; Lynn F Fau - Panzara, M.A.; et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer-Gould, A.; Atlas Sw Fau - Green, A.J.; Green Aj Fau - Bollen, A.W.; Bollen Aw Fau - Pelletier, D.; Pelletier, D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353(4), 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, S.A.; Clift, F.; Devonshire, V.; Lapointe, E.; Schneider, R.; Stefanelli, M.; Vosoughi, R. Use of natalizumab in persons with multiple sclerosis: 2022 update. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Barkhof F Fau - Comi, G.; Comi G Fau - Hartung, H.-P.; Hartung Hp Fau - Khatri, B.O.; Khatri Bo Fau - Montalban, X.; Montalban X Fau - Pelletier, J.; Pelletier J Fau - Capra, R.; Capra R Fau - Gallo, P.; Gallo P Fau - Izquierdo, G.; Izquierdo G Fau - Tiel-Wilck, K.; et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362(5), 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappos, L.; Radue Ew Fau - O'Connor, P.; O'Connor P Fau - Polman, C.; Polman C Fau - Hohlfeld, R.; Hohlfeld R Fau - Calabresi, P.; Calabresi P Fau - Selmaj, K.; Selmaj K Fau - Agoropoulou, C.; Agoropoulou C Fau - Leyk, M.; Leyk M Fau - Zhang-Auberson, L.; Zhang-Auberson L Fau - Burtin, P.; et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362(5), 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, D.; Hafler, D.A. Fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Spelman, T.; Jokubaitis, V.; Havrdova, E.; Horakova, D.; Trojano, M.; Lugaresi, A.; Izquierdo, G.; Grammond, P.; Duquette, P.; et al. Comparison of Switch to Fingolimod or Interferon Beta/Glatiramer Acetate in Active Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M. The risk of varicella zoster virus infection in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2016, 56, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. The multiple sclerosis modulatory potential of natural multi-targeting antioxidants. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht-Mayer, S.; Wimmer, I.; Traffehn, S.; Metz, I.; Brück, W.; Bauer, J.; Bradl, M.; Lassmann, H. Cell type-specific Nrf2 expression in multiple sclerosis lesions. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, Q.; Dang, S.; Jin, M.; Shi, Y.; Wan, B.; Zhang, Y. Inhibition of 12/15-lipoxygenase by baicalein induces microglia PPARβ/δ: a potential therapeutic role for CNS autoimmune disease. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e569–e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Iwasa, K.; Yamashina, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Maruyama, K.; Bosetti, F.; Yoshikawa, K. The flavonoid Baicalein attenuates cuprizone-induced demyelination via suppression of neuroinflammation. Brain Res. Bull. 2017, 135, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-y.; Wang, X.-j.; Su, Y.-l.; Wang, Q.; Huang, S.-w.; Pan, Z.-f.; Chen, Y.-p.; Liang, J.-j.; Zhang, M.-l.; Xie, X.-q.; et al. Baicalein ameliorates ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal epithelial barrier via AhR/IL-22 pathway in ILC3s. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 43, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaceur, A.; Delacour, J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res. -59. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, H.-J.; Li, X.-M. Differential effects of antipsychotics on the development of rat oligodendrocyte precursor cells exposed to cuprizone. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 264, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, M.; Salimi, A.; Seydi, E.; Naserzadeh, P.; Kouhnavard, M.; Rahimi, A.; Pourahmad, J. Toxicity of cuprizone a Cu2+chelating agent on isolated mouse brain mitochondria: a justification for demyelination and subsequent behavioral dysfunction. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2016, 26, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.E.; Rhie, S.J.; Yoon, S. The role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 2015, 24, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branca, C.; Ferreira, E.; Nguyen, T.-V.; Doyle, K.; Caccamo, A.; Oddo, S. Genetic reduction of Nrf2 exacerbates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4823–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, M.S.; Gray, N.E. NRF2 as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases. ASN Neuro 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MichaliČKovÁ, D.; ŠÍMa, M.; SlanaŘ, O. New insights in the mechanisms of impaired redox signaling and its interplay with inflammation and immunity in multiple sclerosis. Physiol. Res. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.C.; Vargas, M.R.; Pani, A.K.; Smeyne, R.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Kan, Y.W.; Johnson, J.A. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: Critical role for the astrocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 2933–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podbielska, M.; Banik, N.; Kurowska, E.; Hogan, E. Myelin recovery in multiple sclerosis: The challenge of remyelination. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 1282–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, P.; De Groot, C.J.A. Staging of multiple sclerosis (MS) lesions: pathology of the time frame of MS. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2000, 26, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, S. Role of glial cells in innate immunity and their role in CNS demyelination. J. Neuroimmunol. 2011, 239, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolati, S.; Babaloo, Z.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Ayromlou, H.; Sadreddini, S.; Yousefi, M. Multiple sclerosis: Therapeutic applications of advancing drug delivery systems. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 86, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinza, I.; Ayoub, I.M.; Eldahshan, O.A.; Hritcu, L. Baicalein 5,6-dimethyl ether prevents memory deficits in the scopolamine zebrafish model by regulating cholinergic and antioxidant systems. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, J.; Vengalasetti, Y.V.; Bredesen, D.E.; Rao, R.V. Neuroprotective herbs for the management of alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, X.; Li, Y.; Ye, W.; Yao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Gao, J. Baicalein-corrected gut microbiota may underlie the amelioration of memory and cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M.R.; Nabavi, S.F.; Habtemariam, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M. The effects of baicalein and baicalin on mitochondrial function and dynamics: A review. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.H.; Huang, K.X.; Yang, X.L.; Xu, H.B. Free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of flavonoids extracted from the radix of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999, 1472, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, D.P.; Ungurianu, A.; Ciotu, C.I.; Fischer, M.J.M.; Olaru, O.T.; Nitulescu, G.M.; Andrei, C.; Zbarcea, C.E.; Zanfirescu, A.; Seremet, O.C.; et al. Effects of Venlafaxine, Risperidone and Febuxostat on Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination, Behavioral Deficits and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, S.; Huang, Q.; Xu, H. N-acetylcysteine attenuates the cuprizone-induced behavioral changes and oligodendrocyte loss in male C57BL/7 mice via its anti-inflammation actions. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 96, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Su, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xu, H. Deep rTMS mitigates behavioral and neuropathologic anomalies in cuprizone-exposed mice through reducing microglial proinflammatory cytokines. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Pons, N.; Torrente, M.; Colomina, M.T.; Vilella, E. Behavioral deficits in the cuprizone-induced murine model of demyelination/remyelination. Toxicol. Lett. 2007, 169, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbits, N.; Pannu, R.; Wu, T.J.; Armstrong, R.C. Cuprizone demyelination of the corpus callosum in mice correlates with altered social interaction and impaired bilateral sensorimotor coordination. ASN Neuro 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.S.; Engler, J.B.; Friese, M.A. The neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzelnigg, A.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Stadelmann, C.; Brück, W.; Rauschka, H.; Bergmann, M.; Schmidbauer, M.; Parisi, J.E.; Lassmann, H. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2005, 128, 2705–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; Rinaldi, F.; Grossi, P.; Gallo, P. Cortical pathology and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.A.; Calatayud, C.A.; Bertone Uña, A.L.; Millet, V.; Pasquini, J.M.; Soto, E.F. The neurotoxic effect of cuprizone on oligodendrocytes depends on the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by microglia. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 32, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, H.A.; Mason, J.; Marino, M.; Suzuki, K.; Matsushima, G.K.; Ting, J.P.Y. TNFα promotes proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahad, D.; Lassmann, H.; Turnbull, D. Review: Mitochondria and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2008, 34, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp, M.; Clarner, T.; Dang, J.; Copray, S.; Beyer, C. The cuprizone animal model: new insights into an old story. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praet, J.; Guglielmetti, C.; Berneman, Z.; Van der Linden, A.; Ponsaerts, P. Cellular and molecular neuropathology of the cuprizone mouse model: Clinical relevance for multiple sclerosis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 47, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Zveik, O.; Fainstein, N.; Lachish, M.; Rechtman, A.; Sofer, L.; Brill, L.; Ben-Hur, T.; Vaknin-Dembinsky, A. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells differentiation induction with MAPK/ERK inhibitor fails to support repair processes in the chronically demyelinated CNS. Glia 2023, 71, 2815–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zveik, O.; Fainstein, N.; Rechtman, A.; Haham, N.; Ganz, T.; Lavon, I.; Brill, L.; Vaknin-Dembinsky, A. Cerebrospinal fluid of progressive multiple sclerosis patients reduces differentiation and immune functions of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia 2022, 70, 1191–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zveik, O.; Rechtman, A.; Ganz, T.; Vaknin-Dembinsky, A. The interplay of inflammation and remyelination: rethinking MS treatment with a focus on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, T.; Al-Kafaji, G.; Bakheit, H.F.; AlAli, F.; Fattah, M.; Alhajeri, S.; Alharbi, M.A.; Daif, A.; Alsabbagh, M.M.; Alwehaidah, M.S.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of the whole mitochondrial genome identifies functionally deleterious mutations in patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.R.; Mahad, D.J. Mitochondrial changes associated with demyelination: Consequences for axonal integrity. Mitochondrion 2012, 12, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; McDonough, J.; Yin, X.; Peterson, J.; Chang, A.; Torres, T.; Gudz, T.; Macklin, W.B.; Lewis, D.A.; Fox, R.J.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 59, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, P.P.; Guevara, C.; Olesen, M.A.; Orellana, J.A.; Quintanilla, R.A.; Ortiz, F.C. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis: The role of Nrf2-dependent pathways. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draheim, T.; Liessem, A.; Scheld, M.; Wilms, F.; Weißflog, M.; Denecke, B.; Kensler, T.W.; Zendedel, A.; Beyer, C.; Kipp, M.; et al. Activation of the astrocytic Nrf2/ARE system ameliorates the formation of demyelinating lesions in a multiple sclerosis animal model. Glia 2016, 64, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosito, M.; Testi, C.; Parisi, G.; Cortese, B.; Baiocco, P.; Di Angelantonio, S. Exploring the use of dimethyl fumarate as microglia modulator for neurodegenerative diseases treatment. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abramov, A.Y. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.; Xu, Z.; Qu, C.; Zhang, J. Dimethyl fumarate improves cognitive deficits in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion rats by alleviating inflammation, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis via NRF2/ARE/NF-κB signal pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uruno, A.; Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1-NRF2 system and neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 38, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Song, X.; Xu, J.; Shi, Y.; Hu, R.; Ren, Z.; Qi, Q.; Lü, H.; Cheng, X.; Hu, J. Morroniside protects OLN-93 cells against H2O2-induced injury through the PI3K/Akt pathway-mediated antioxidative stress and antiapoptotic activities. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saija, A.; Scalese, M.; Lanza, M.; Marzullo, D.; Bonina, F.; Castelli, F. Flavonoids as antioxidant agents: importance of their interaction with biomembranes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 19, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Cha, H.-J.; Choi, E.O.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, G.-Y.; Yoo, Y.H.; Hwang, H.-J.; Park, H.T.; Yoon, H.M.; Choi, Y.H. Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway contributes to the protective effects of baicalein against oxidative stress-induced DNA damage and apoptosis in HEI193 Schwann cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Choi, E.O.; Kim, G.-Y.; Hwang, H.-J.; Kim, B.W.; Yoo, Y.H.; Park, H.T.; Choi, Y.H. Protective Effect of Baicalein on Oxidative Stress-induced DNA Damage and Apoptosis in RT4-D6P2T Schwann Cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Guo, S.; Yi, X.; Cui, T.; He, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, C.; et al. Baicalein protects human vitiligo melanocytes from oxidative stress through activation of NF-E2-related factor2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 129, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).