Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) an English physician.

1. Introduction

Age-related peripheral artery disease (PAD) and atherosclerosis with vascular ossification-calcification (VOC) have been around since the times of ancient Egyptians that were discovered by the studies of mummies via computed tomography scanning, which reveled vascular calcifications [

1,

2,

3]. Globally, PAD affects 200-250 million people [

4,

5]. Currently, we are living in one of the oldest living populations in history [

6,

7,

8] and therefore, we can expect to experience an even higher occurance of symptomatic PAD, atherosclerosis, VOC, hypertension (specifically systolic hypertension) with increased injurious pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

4,

5,

9,

10].

The presence of PAD is associated with a marked increase in the prediction of cerebrocardiovascular disease (CCVD) events such as myocardial infarction and stroke with increased morbidity and mortality [

11]. Further, Grenon et al. were able to demonstrate that coronary artery disease (CAD) plus PAD had greater risk for cerebrocardiovascular disease (CCVD) events such as myocardial infarction and stroke with increased morbidity and mortality than those individuals with just CAD alone [

12]. Indeed, PAD should be considered a red flag warning in that it serves as a biomarker for the increased risk, morbidity and mortality of CCVD events [

11,

12].

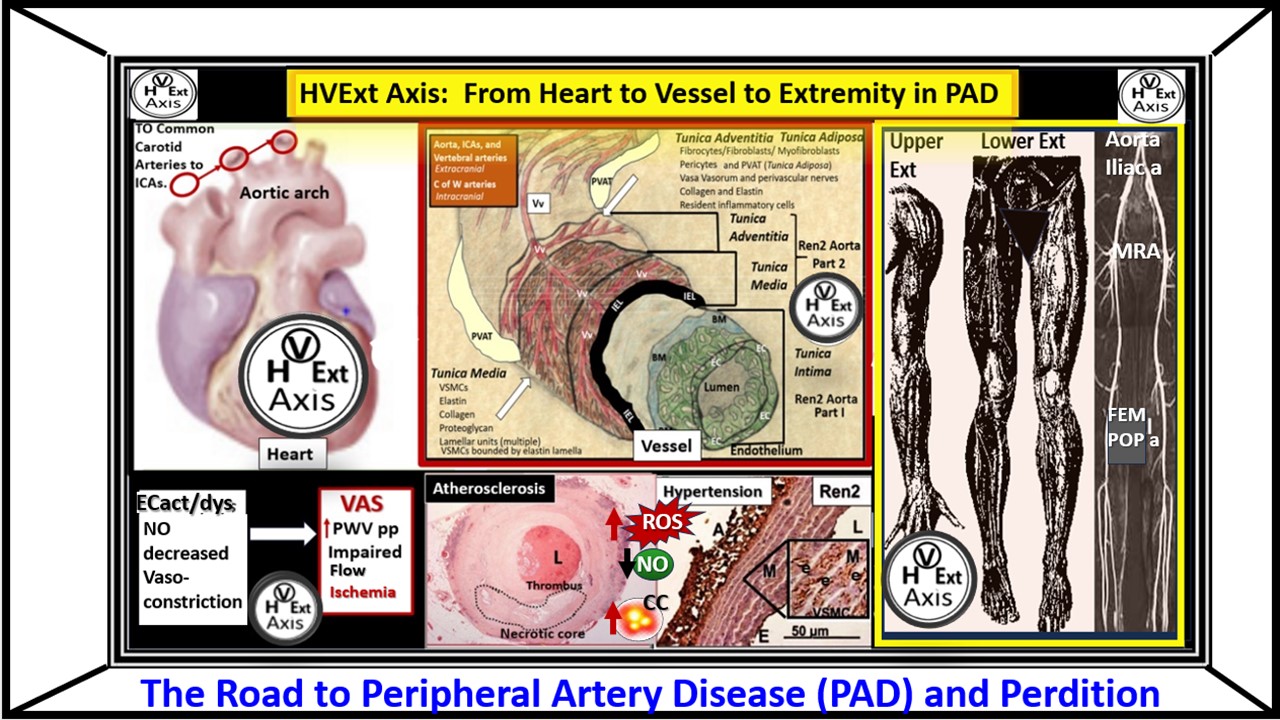

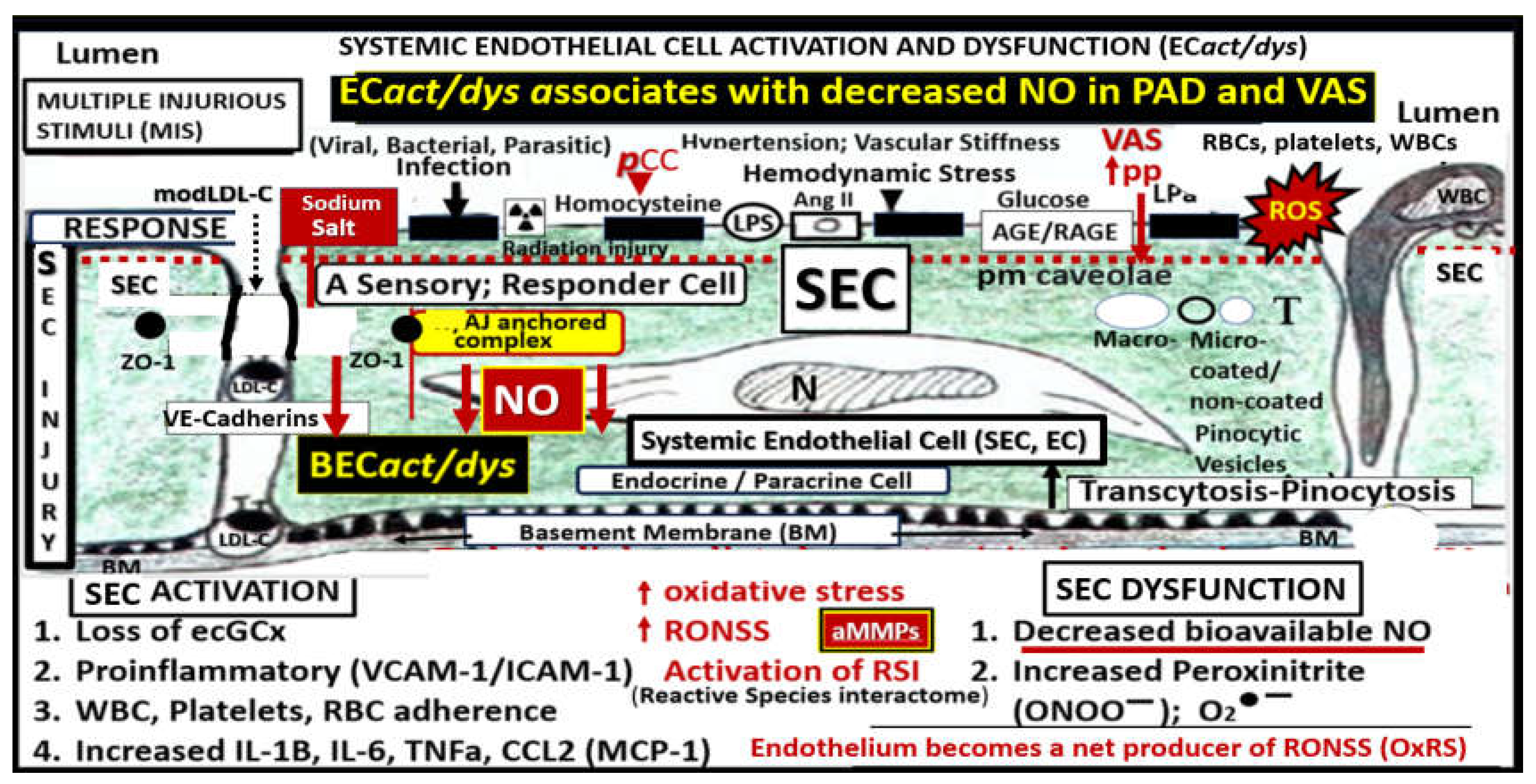

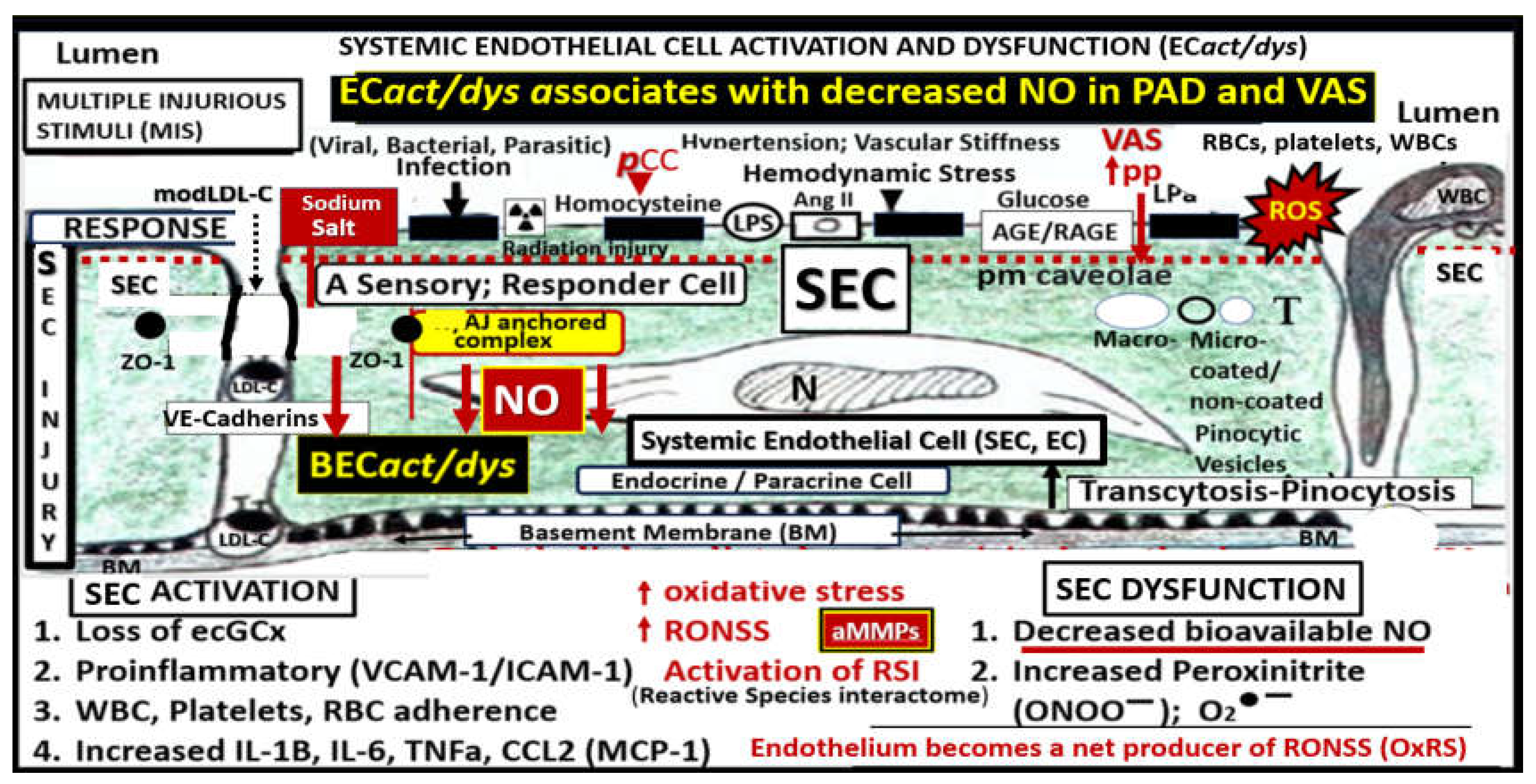

The vascular endothelial cell(s) (ECs) with their protruding cell surface protective endothelial glycocalyx (ecGCx) are the first cells and surface layer that are exposed to the circulating blood plasma, red blood cells, leukocytes, and multiple injurious species that are capable of triggering EC activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

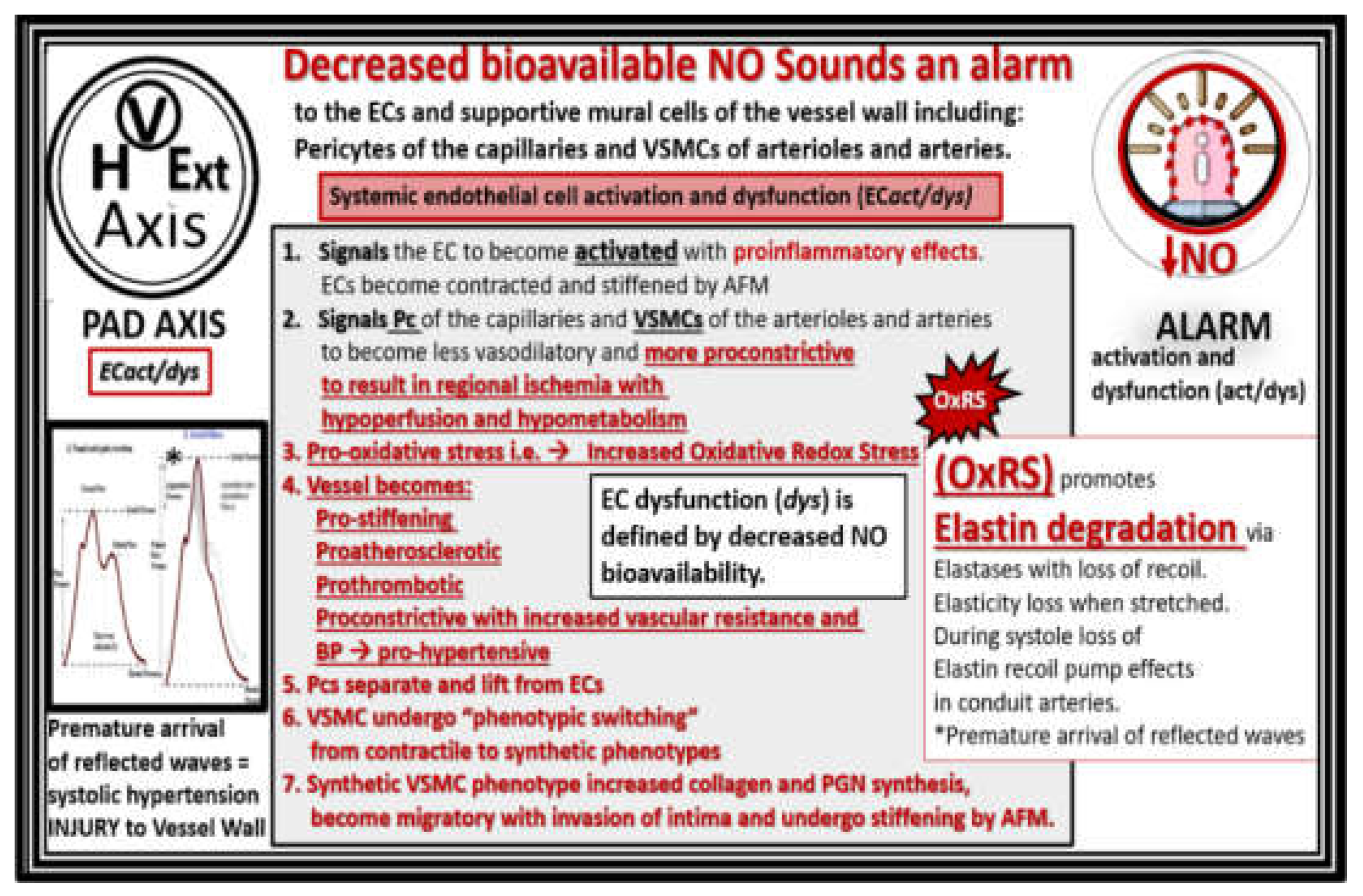

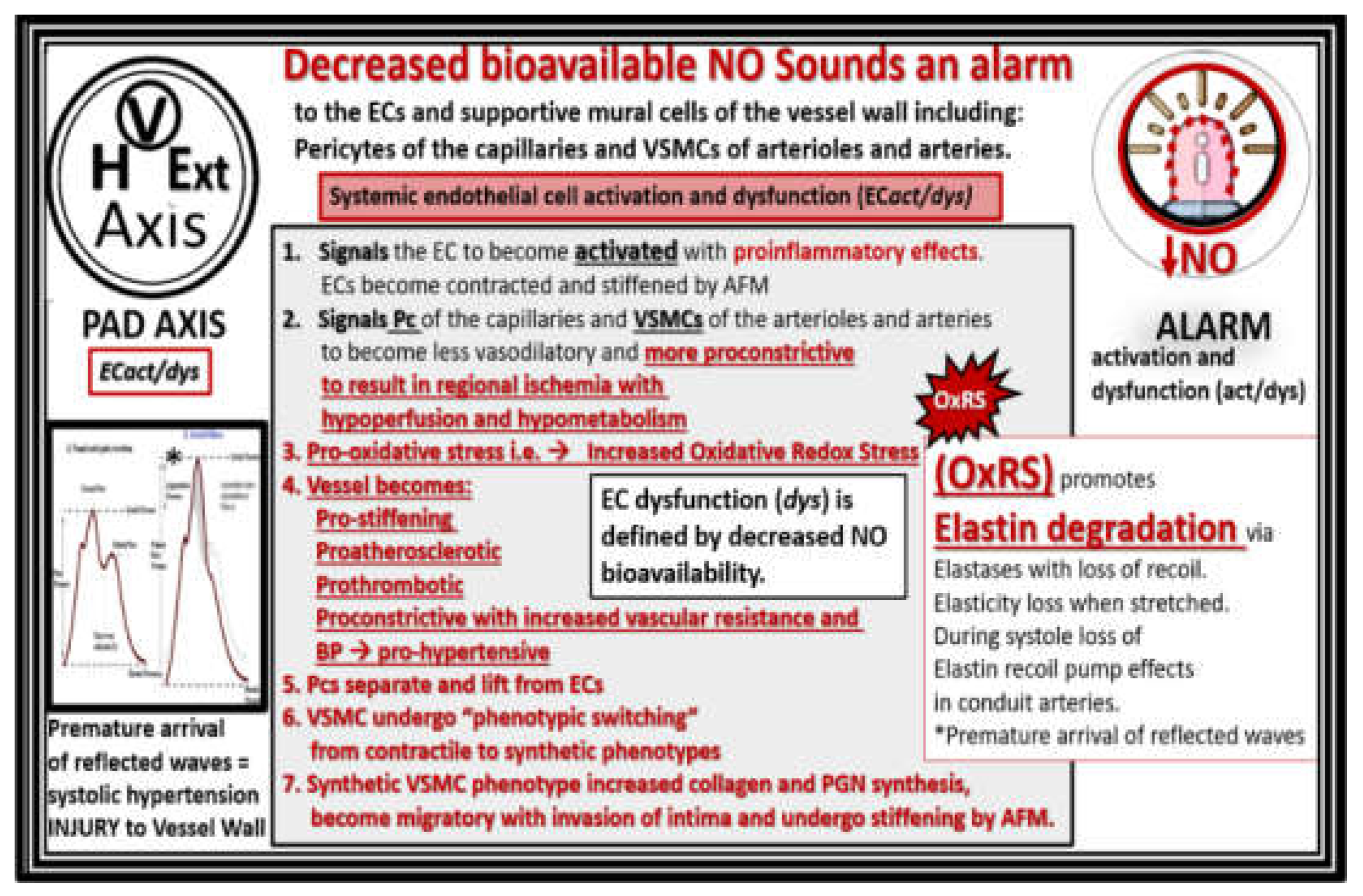

EC

act/dys results in a proinflammatory surface with attenuation and/or loss of the ecGCx (activation), while ECdys results in a decrease in bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) [

9]. Indeed, EC dysfunction with decreased bioavailability of NO may sound an alarm within the cells of the vessel wall (

Figure 3) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Interestingly, the decrease in the bioavailability of NO may not only sound an alarm but also may act to activate an alarmin system also referred to as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), wherein multiple response to injury inflammatory immune signals interact with pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [

23,

24]. A brief list of EC alarmins involved with atherosclerosis include: high mobility group box 1(HMGB1), Fas ligand, heat shock proteins (HSP70-90), S100AB, and S100A9 [

23,

24].

PAD results primarily from chronic and progressive atherosclerotic disease characterized by narrowing of the peripheral arteries and reduced blood flow to the lower extremities [

25]. Vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) of the extremities is closely related to the continued development of atherosclerosis and its progression. As atherosclerotic plaque burden progresses and extracellular matrix accumulate, the arteries and particularly the arterioles will have less lumen diameter and stiffening will continue to progess with less ability to dilate and carry blood oxygen and nutrients resulting in ischemia, ischemic pain and neuropathy in the extremities with intermittent claudication (IC) that may progress to resting pain with ischemic ulceration and or limb loss with critical limb ischemia (CLI) [

26].

The primary aim of this narrative review is to increase the database of knowledge regarding the development and progression of PAD in order to decrease its increasing morbidity and mortality. In the following sections, author will discuss PAD and the role of atherosclerosis, aging and HTN, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Also addressed, is the importance of bioavailable NO and its pathologic injurious structural remodeling roles and functional abnormalities in PAD that associate with decreased bioavailability in the presence of EC

act/dys as in

Figure 3. Additionally, VAS and vascular ossification calcification (VOC), microvessel remodeling in skeletal muscle, and ischemic neuropathy with neuronal remodeling in the lower extremities and the perception of pain will be discussed along with concluding remarks and future directions.

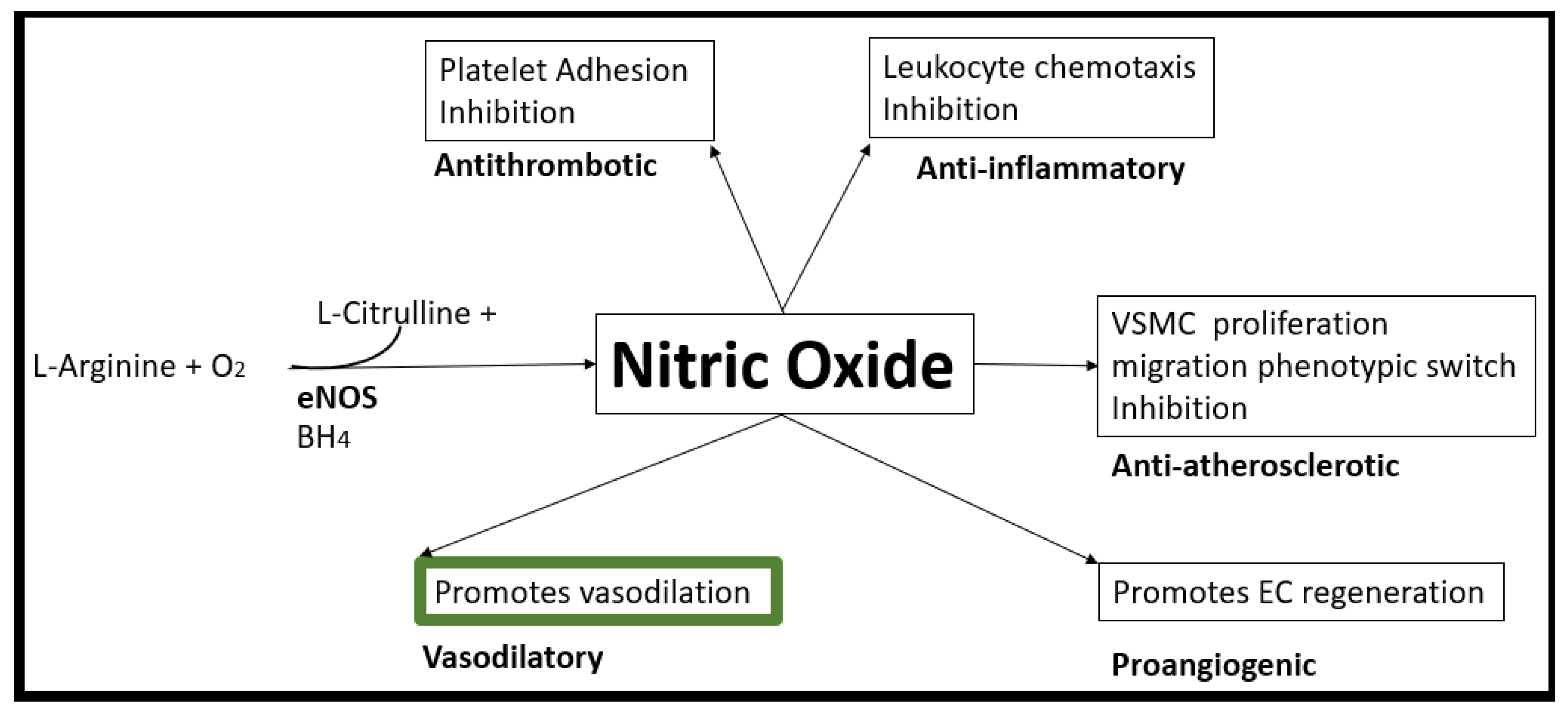

3. Decreased Bioavailability of Endothelial Cell-Derived Nitric Oxide in PAD

When the endothelium is exposed to the multiple injurious species as presented in figures one and two in the introduction, it becomes activated and dysfunctional. EC

act/dys associates with a proinflammatory EC (activation) and decreased NO bioavailability (dysfunction). This EC

act/dys plays an important role in the development of CCVDs, which includes PAD. Indeed, decreased NO bioavailability plays an important role in the development of atherosclerosis, HTN, VAS and PAD [

76,

77,

78].

In health, vascular EC-derived NO (one of three EC gasotransmitters along with carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide) is known to be responsible for numerous pleiotropic and vasculoprotective functions. These protective functions include its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antithrombotic, antiatherosclerotic, antiplatelet activation (decreasing adherence and aggregation) with potent vasodilation properties [

75,

79,

80,

81,

82]. NO synthesis is dependent on its substrate L-arginine oxidation with NADPH and oxygen serving as co-substrates and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase enzyme (eNOS) with its essential cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) that must be in its totally reduced form in order to run the eNOS reaction to produce NO and L-citrulline [

83]. Unfortunately, when there is increased OxRS, BH4 will be oxidized to BH2 and the eNOS reaction will not run to produce NO. The eNOS reaction is very sensitive to detrimental effects of OxRS since this not only interferes with the total reduction of BH4 but also associates with increased asymmetrical dimethyl arginine (ADMA) that competes with L-arginine for NO production [

77]. Also, the known decrease in NO due to the excessive and rapid oxidation of NO to nitrite (NO

2−), peroxynitrite, and nitrate (NO

3−) via increased OxRS also contributes to decreased NO bioavailability [

84]. Unfortunately, when there develops a decreased in NO bioavailability due to EC

act/dys as in PAD in

Figure 3, a vascular alarm is sounded and this results in at least seven detrimental cellular effects of the arterial vessel wall that promotes not only atherogenesis but also VAS and PAD.

Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) is an important mediator between the vicious cycle of inflammation and OxRS wherein one instigates the other bidirectionally. Additionally, homeostatic levels of NO are known to directly inhibit NF-κB activation by preventing the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB-α, a protein that keeps NF-κB inactive in the cytoplasm and this relationship results in the findings that when NO is decreased it associates with increased activity of NF-κB [

85]. Interestingly, the other gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is capable of NO production via a cascade of phosphorylation events that starts with p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Akt to eNOS, to form NO [

86,

87]. Indeed, EC-derived NO via the eNOS enzyme plays a critical role in the maintenance of vascular homeostasis (

Figure 12) [

88].

4. Vascular Arterial Stiffening (VAS) in PAD

VAS and PAD are clinically determined by the careful examination of individuals for decreased or asymmetrical pulsations of distal lower extremity arteries and elevated systolic blood pressure-isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) with an increase in pulse pressure. Additional evaluation for VAS includes the more precise and quantitative measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) or the gold standard, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV) [

89]. Importantly, the finding of VAS is well known to be an independent predictor of CVD morbidity and mortality [

90,

91]. Multiple risk factors for the development of VAS include: aging [

62,

92,

93,

94]; MetS [

62]; T2DM and insulin resistance [

95,

96,

97]; obesity [

98,

99]. Also, lifestyle risks are involved such as: smoking [

100], physical inactivity-sedentary lifestyle [

101], and high salt, high caloric intake as occurs with the diet-induced obesity Western style diets [

102,

103]. Risk factors for the development of VAS and PAD closely parallel those of CVD [

104,

105] and importantly, VAS may even begin in youth or middle age with some reports that VAS may precede the development of HTN and metabolic risks [

106].

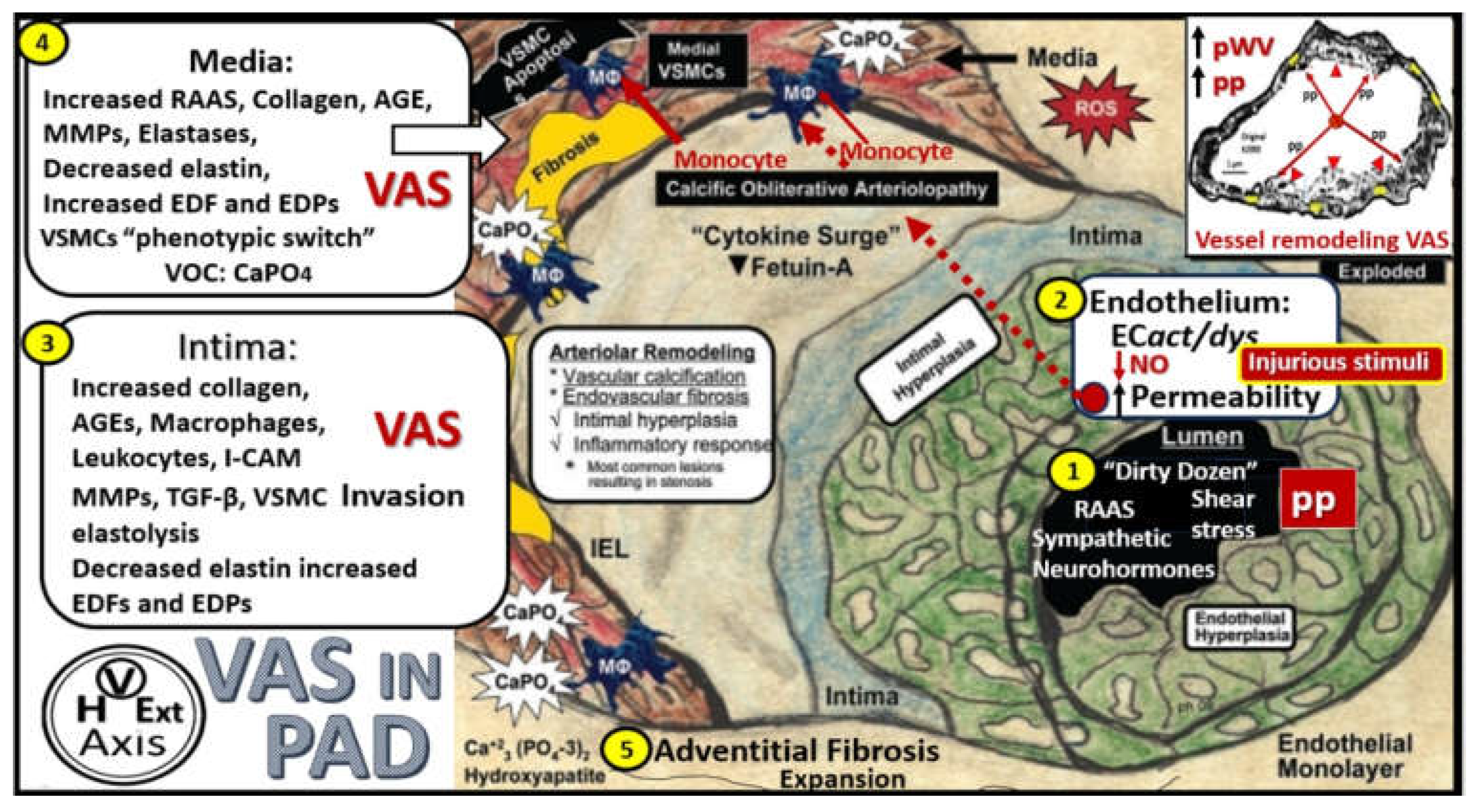

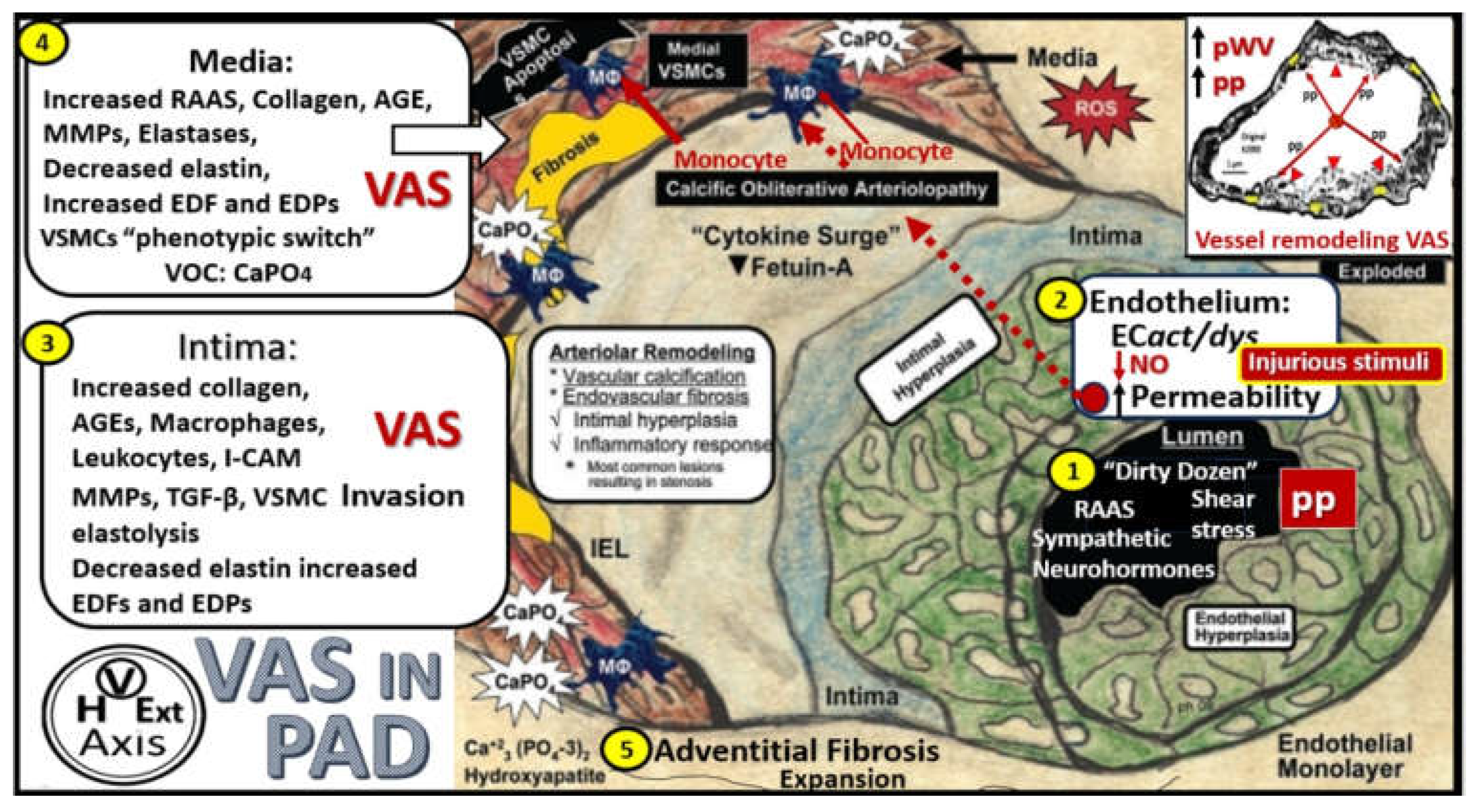

The pathobiology mechanisms for the development and progression of VAS are currently thought to be initiated by injuries to the endothelium by a number of injurious stimuli as previously listed in

Figure 2 as the dirty dozen [

21]. Once injured, EC

act/dys develops, which results in a proinflammatory endothelium with increased OxRS and decreased NO bioavailability. This functional change in the activated and dysfunctional endothelium results in a response to injury wound healing mechanism that becomes chronically activated along with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the direct damaging effects of AngII and aldosterone induced OxRS and transforming growth factor-beta one (TGF-β1). Following the activation and dysfunction of the endothelium there is an activation of MMPs and various elastases to result in the degradation, fragmentation, and splitting of elastin and loss of compliance and recoil upon stretching. These remodeling changes of elastin give rise to elastin-derived fragments (EDFs) that are a rich source of elastin-derived peptides (EDPs) and along with OxRS are known to result in a vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMC(s) “phenotype switch” (from a contractile phenotype to a synthetic phenotype) in the media. Additionally, in the proliferative phases of the wound healing mechanism the cytokine growth factor TGF-β1 is known to be increased and also stimulates these reactive VSMCs to produce stiffer organized collagen, i.e. fibrosis. In turn, these reactive, dedifferentiated, synthetic, proliferative VSMCs are known to be highly synthetic (with increased production of stiffer collagen (types I) and proteoglycans (PGNs) within the media, and a heightened capability for migration to the intima of the vessel wall to result in and contribute to the neogenesis of the intimal space. These structural and functional remodeling changes to the ECM proteins elastin and collagen result in a decreased elastin/collagen ratio with ensuing increased vascular stiffness (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) [

21,

98,

105,

107,

108,

109,

110].

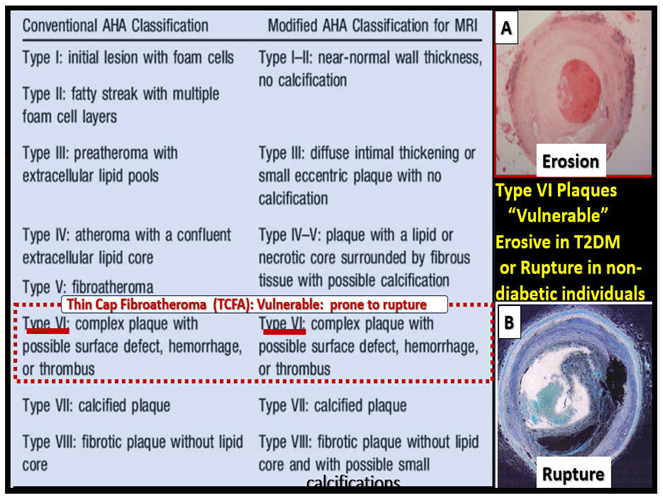

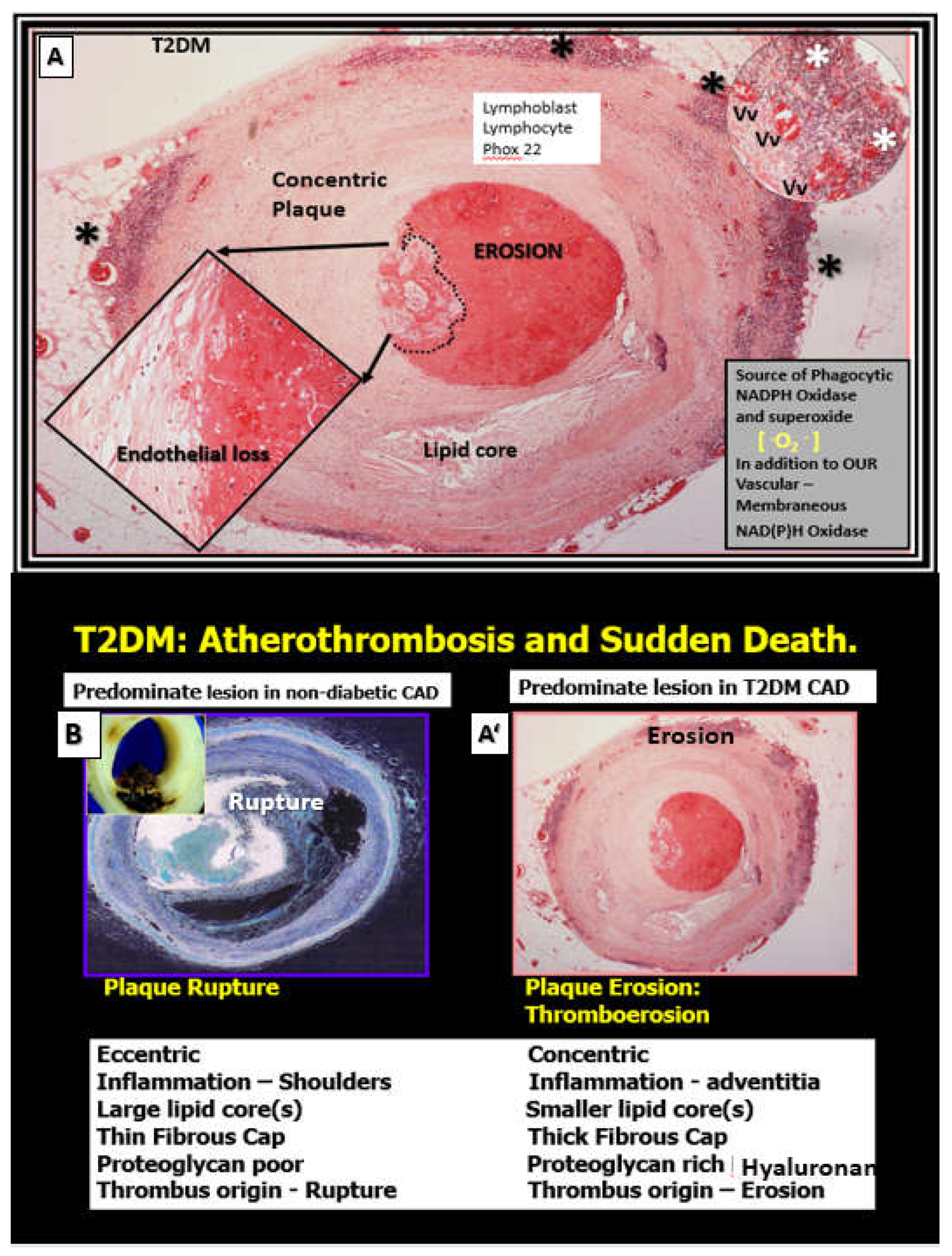

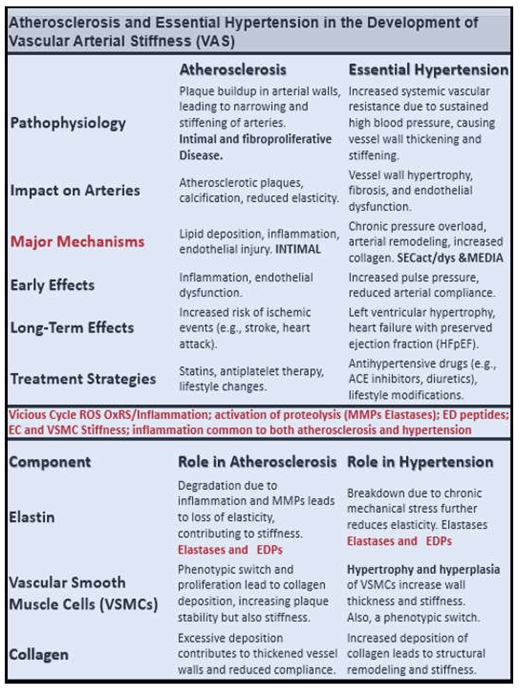

T2DM with its accelerated atherosclerosis and HTN frequently co-occur in aging [

111,

112]. Therefore, it is important to compare some of the effects of atherosclerosis and HTN in the development of VAS in PAD (

Box 2).

Box 2. Comparison of atherosclerosis and hypertension (HTN) in the development of vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and peripheral artery disease (PAD). Notably, atherosclerosis is an intimal disease that associates primarily with PAD and that HTN is a disease that associates with the media of the arterial vessel wall that associates primarily with VAS. However, note that many of the pathologic mechanisms of HTN and atherosclerosis may be associated with either VAS or PAD. Reproduced image provided with permission by CC 4.O [

21]. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; EC(s), endothelial cells; EDPs, elastin-derived peptides; MMP(s), matrix metalloproteinases; SECact/dys, systemic endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; VSMC(s), vascular smooth muscle cells.

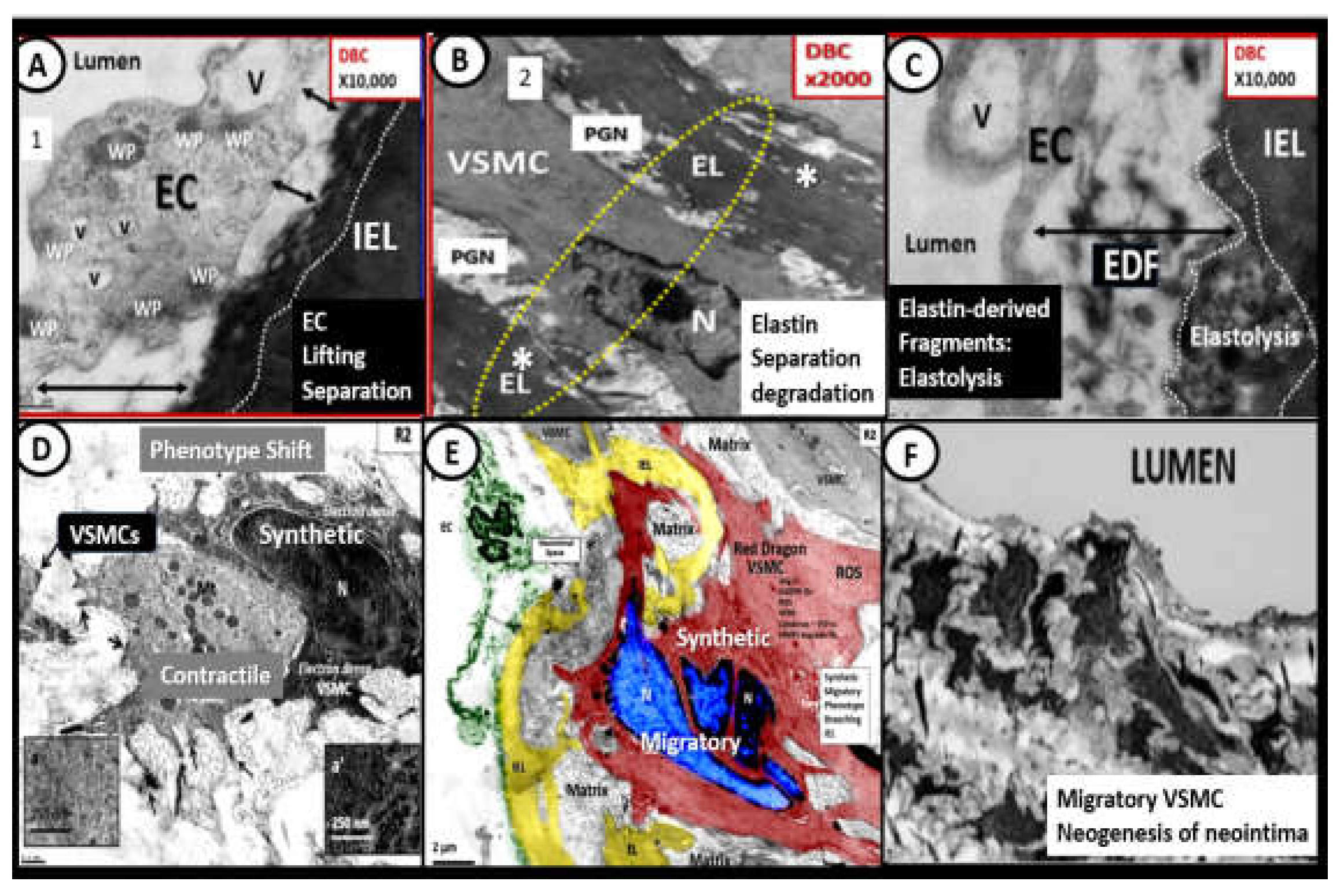

4.1. Bioactive Elastin-Derived Peptides (EDPs) and Transglutaminase 2 (TG2)

The degradation of the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and elastin lamella result in the formation/production of elastin-derived fragments (EDFs) that are a rich source of elastin-derived peptides as visualized in

Figure 14 in panels A-C; however, these similar remodeling changes are also found to be present in hypertension (not shown). These bioactive EDPs (also termed matrikines or elastokines) interact with their receptors the elastin receptor complex and are capable of instigating multiple interactions that contribute to the development and progression of VAS in PAD. EDPs are known to promote inflammation and react with RAGE to increase OxRS, NFkappa B, MMP activation, cytokine activation including TNFa and IL-6, increased crosslinking of collagen and elastin to collagen, and importantly to promote phenotypic switching from contractile VSMCs to a synthetic, proliferative, migratory phenotype, that increases the synthesis of collagen and proteoglycans. Indeed, EDPs contribute to VSMC remodeling and further amplify elastin degradation to promote VAS in both atherosclerosis and hypertension that may be present in the development of PAD [

113,

114,

115].

Importantly, transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is an enzyme that is ubiquitously expressed in the vasculature, which promotes the synthesis and crosslinking of extracellular matrix collagen that is also important in the development of VAS. Increased TG2 is a known collagen crosslinker that associates with VAS and affects the extracellular matrix by increasing collagen deposition, and crosslinking (in a calcium-dependent manner) that has been long recognized as critical player in vascular stiffening [

102,

116]. Herein, it is notable that Ramirez-Perez et al. were able to demonstrate that cystamine (a nonspecific TG2 inhibitor) reduced vascular stiffness in Western diet-fed female mice; however, they did not investigate cysteamines’ role as also being an antioxidant that could additionally contribute to the vascular destiffening effects [

102].

The multiple functional and structural remodeling changes discussed in this section are multifactorial and complicated to say the least. However, it is possible to create a more simplified possible sequence of events that help to understand the development and progression of VAS in the development and progression of PAD, which can supplement the recent findings by the multiorganizational bodies for the recommended reading of the management of lower extremity PAD (

Figure 15) [

117].

Importantly, it has been demonstrated that VAS with its damaging increased pulsatile pulse pressure (an injurious stimuli to the endothelium) is independently associated with PAD even after adjusting for several atherosclerotic risk factors and that there is a significant association between VAS and the onset of PAD regardless of blood pressure status [

26,

118].

4.2. Vascular Ossification Calcification (VOC) in Type VII Plaques

VOC is the term utilized to define the process of calcium phosphate complexes deposition in the form of hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) in the media of the vasculature, which also results in increased VAS [

21,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122]. Arterial VOC is a definite characteristic of vascular aging [

123,

124] and is also increased in clinical diseases such as diabetes, HTN, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and hereditary disorders (

Figure 16) [

21,

107,

125,

126].

VOC occurs at different locations, e.g. in HTN VOC occurs primarily in the tunica media regions and in diabetes it occurs primarily in the tunica intima; however, in certain situations VOC may co-occur in both regions since these two clinical diseases often co-occur [

119,

127]. Notably, VOC is no longer thought to be a passive process that associates with aging, but involves a reprogramming of tunica media VSMC from its contractile phenotype to a synthetic and proliferative, migratory phenotype that is capable of becoming an osteogenic cell [

108,

128]. Indeed, local VSMC cues are different for medial calcification that associates with aging, HTN, senescence, and uremia of renal failure with multiple elevations of uremic toxins and specifically elevated calcium and phosphate levels in contrast to atherosclerosis-related aortic tunica intima calcification, which involves inflammation, OxRS, and apoptosis [

99,

128].

Also, elastin degradation/fragmentation as depicted in

Figure 14C results in the release of bioactive EDPs, which can readily induce an osteogenic phenotype switch along with OxRS from an activated endothelium to induce a contractile VSMC to a synthetic phenotype. Once this phenotype switch occurs these VSMC are capable of producing calcification similar to osteogenic cells in bone in the media that have a predilection to adhere to the damaged elastin lamella within the media or to the internal elastic lamella of the intima [

129]. While VOC was not included in the six-steps regarding the development of PAD in

Figure 15, it is nevertheless a very important step in its progression.

4.3. PAD involves arterial vessels large and small: Microvessel (Mv) remodeling in skeletal muscle (SkM)

Lower extremity PAD is caused by the initial progression and expansion of atherosclerosis of the large conduit arteries that develop VAS and PAD with ischemia due to progressive luminal narrowing and or thrombosis. However, it is the microvessels (arterioles, capillaries, and venules with lumen diameters ranging from 5 to 500 micrometers) that undergo structural remodeling and functional changes that contribute to the horrendous and horrifying pain associated with claudication, nocturnal leg cramps (lower extremity myalgias and myopathy), and the stabbing-like pain of ischemic peripheral neuropathy [

130,

131].

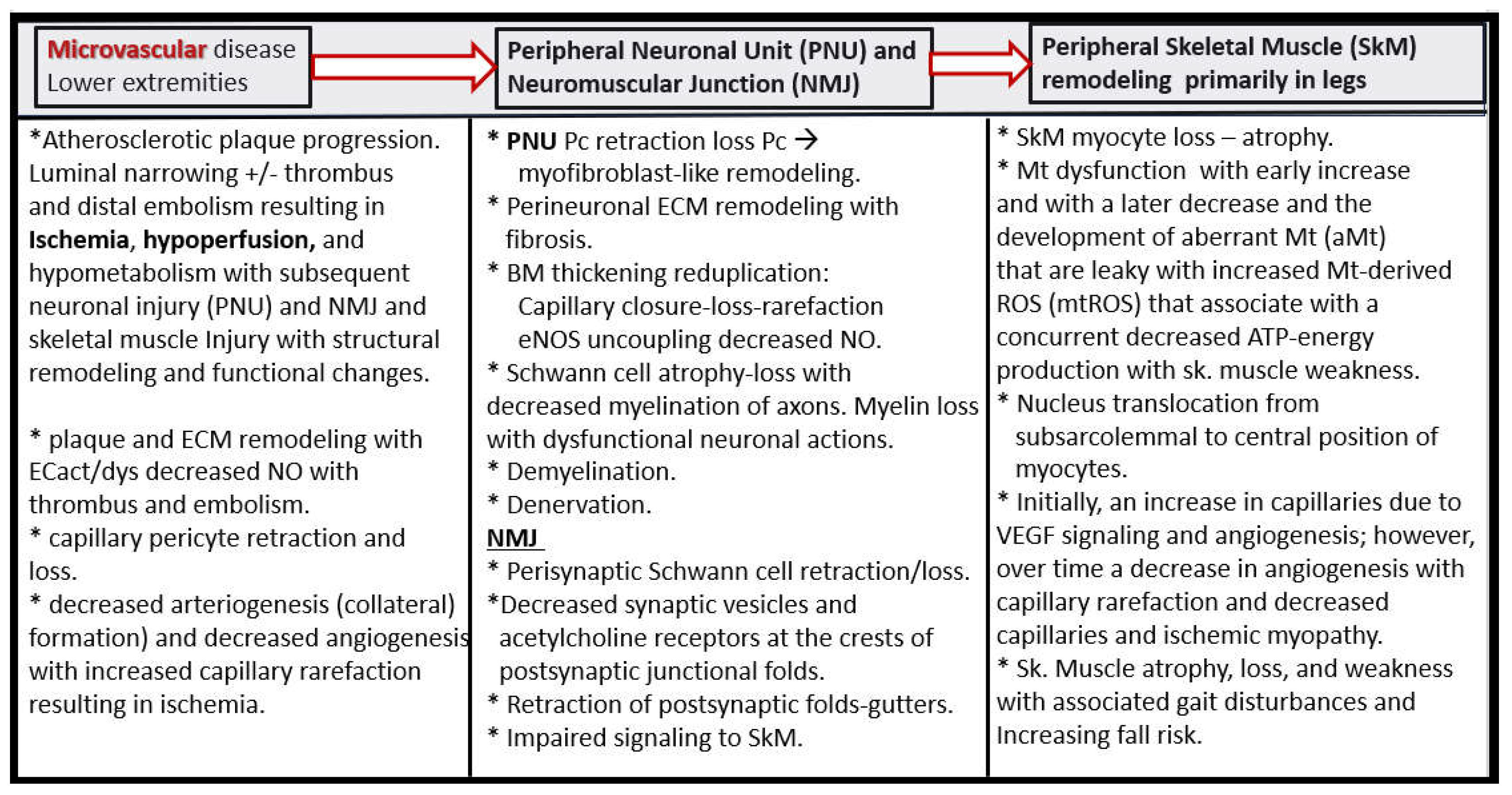

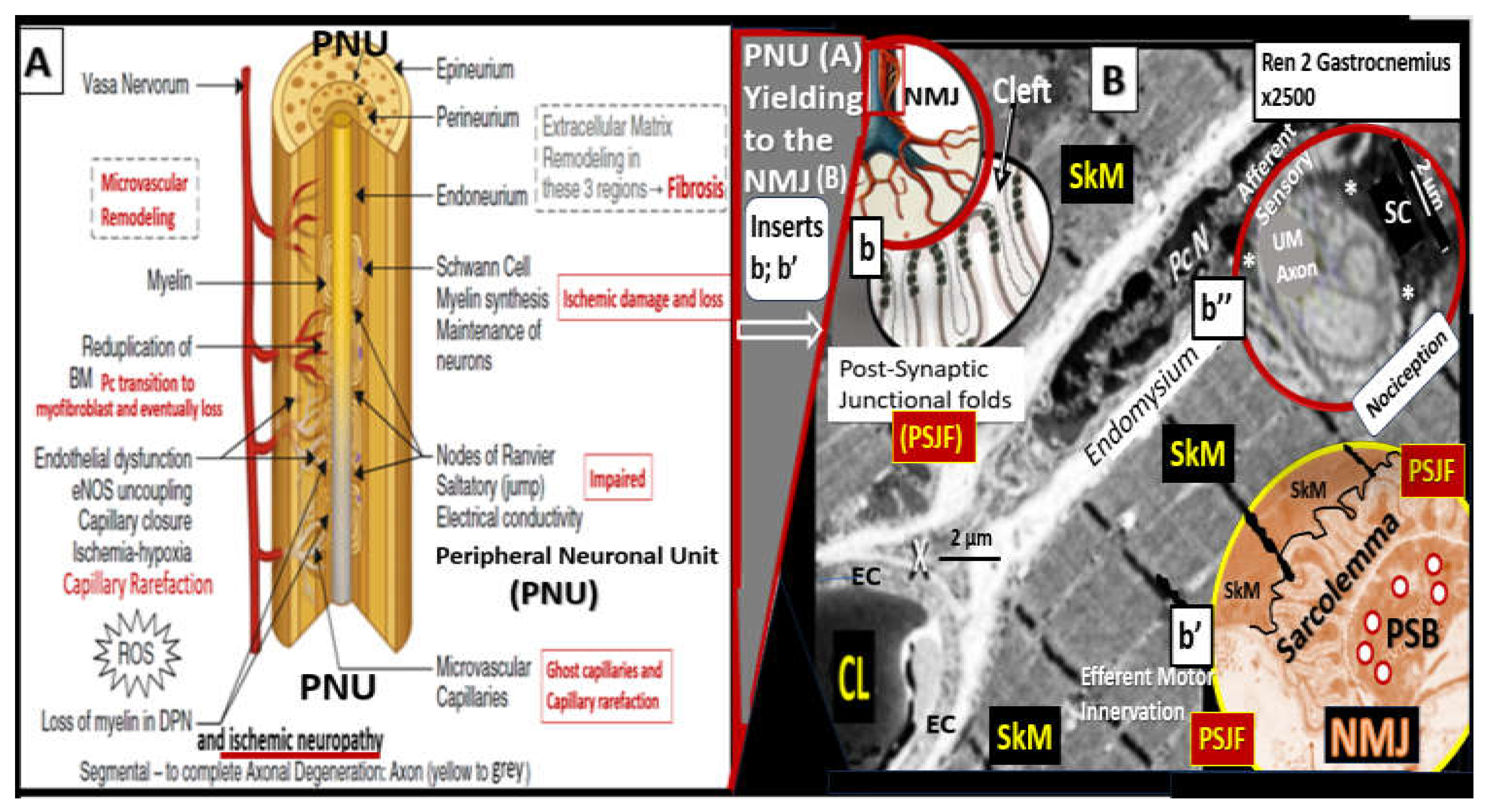

Mv remodeling is extensive in PAD and consists of i) basement membrane thickening (primarily due to increased type IV collagen; ii) perivascular collagen I and type III fibrosis due to the initial response to injury to acute or early critical ischemia with an initial increased pericyte coverage of Mv capillary ECs and their capability to transition to myofibroblasts as a result of increased transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) chronically; iii) endothelial cell remodeling, which includes endothelial activation that is proinflammatory and endothelial dysfunction that associates with decreased protective bioavailable NO primarily due to eNOS uncoupling; iv) increased OxRS that is central to the peripheral neuronal unit (PNU), neuromuscular junction (NMJ), and the skeletal muscle myopathy aberrant remodeling of PAD [

130,

131]. Importantly, there is evidence that decreased lower extremity skeletal muscle microvascularization is primarily responsible for exercise intolerance in PAD [

132] and that microvascular disease potentiates the risk of amputation in PAD [

133]. Further, the initial response to regional hypoxia due to lower extremity PAD would be increased angiogenesis due to ischemia-induced hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1α) and activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to result in angiogenesis and capillary expansion and density. However, over time this initial angiogenesis may be complicated by capillary loss with the development of string-like microvessels and capillary rarefaction due to the ongoing chronic ischemia induced EC

act/dys, OxRS, inflammation, and decreased NO (

Figure 17) [

131,

132,

133].

Lower extremity PAD impacts skeletal muscle by increased OxRS damage, inflammation, aberrant mitochondria dysfunction/loss, and decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, loss of number and function of myofibers, dysfunction and loss of capillary density, increased proteolysis and apoptosis. Although ischemia/ischemia reperfusion injury cycles are considered the principal cause of skeletal muscle pathophysiology in PAD, the impact of other comorbidities such as hyperlipidemia on endothelial dysfunction and skeletal muscle pathophysiology should not be overlooked [

135].

In addition to microvessel remodeling there is a co-occurance of skeletal muscle (SkM) remodeling that includes skeletal muscle loss (atrophy/ischemia-induced sarcopenia), endomysial fibrosis, myocyte lipid infiltration, and aberrant mitochondria with loss of pericapillary skeletal muscle mitochondrial mounding and loss of subsarcolemmal mitochondria with reduced ATP production in PAD [

136].

Thus, as PAD progresses from chronic atherosclerotic macrovessel disease it results in the development of hypoperfusion and hypometabolism to the lower extremity with microvessel remodeling that transition from the early symptoms of IC, which often progresses to CLI. This results, in structural remodeling in three critical regional tissue beds that are also involved with aberrant functional changes, which include microvessel (Mv), peripheral neuronal unit (PNU), neuromuscular junction (NMJ), and lower extremity SkM regions (

Figure 18).

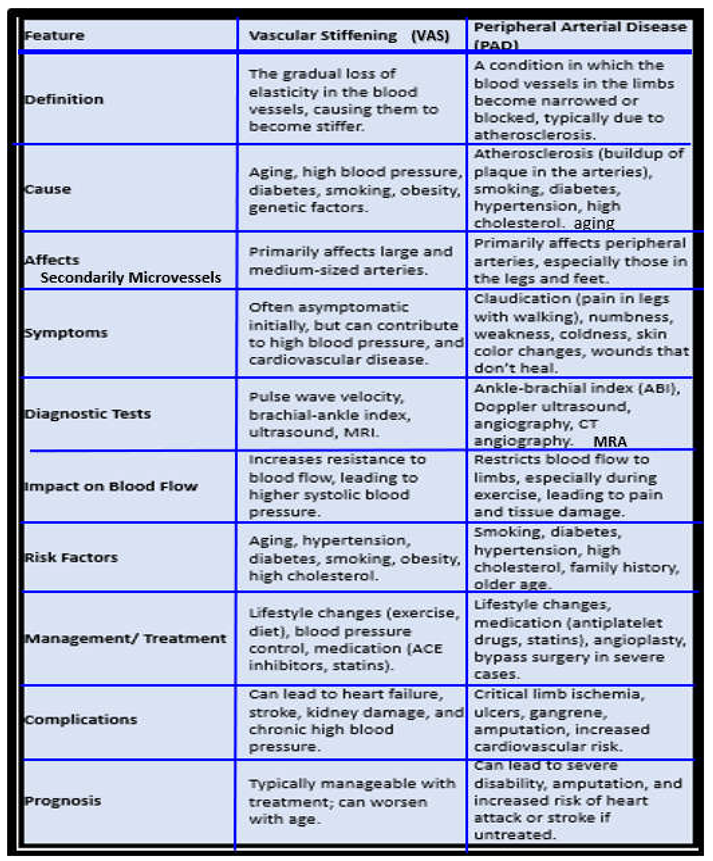

While VAS describes a condition or a process of stiffening of the arterial vessel wall due to a loss of elastin and an increase in stiffer collagen, PAD describes a specific vascular disease associated with the accumulation of intimal atherosclerotic plaques that eventually result in a narrowing of the arterial vessel lumen resulting in ischemia to peripheral arteries as well as an increased incidence of thrombosis and embolism to the distal extremities. Indeed, while VAS and PAD are each important in the development and progression of cerebrocardiovascular diseases, when compared side by side what stands out is how they co-develop, co-occur and share so many commonalities (

Box 3) [

26,

51,

70,

90,

91,

137].

Box 3. A simplistic comparison of vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; CT, computed tomography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

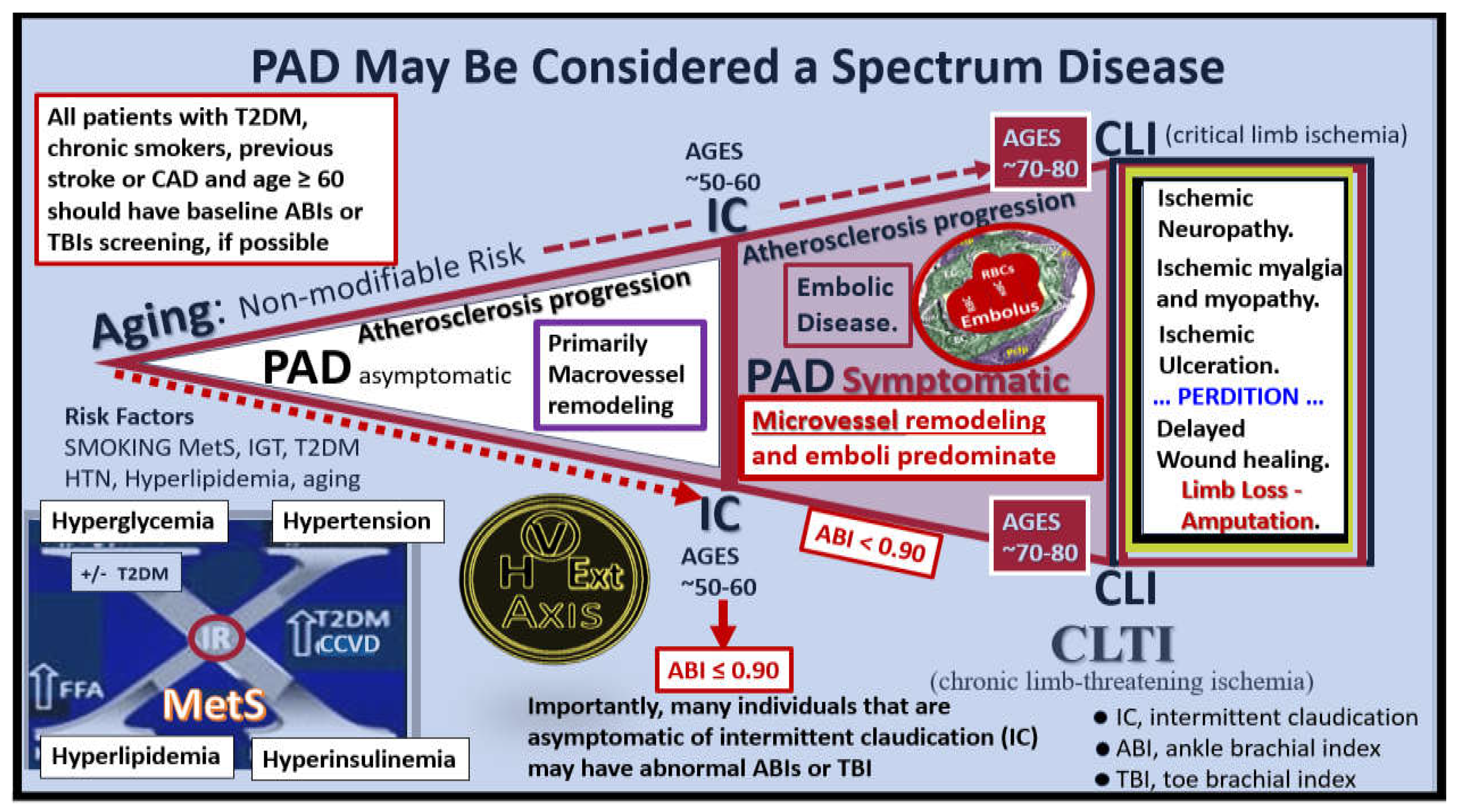

At this juncture, it is noteworthy to point out that PAD may be considered a spectrum disorder/disease as portrayed in following image (

Figure 19) [

131,

133,

138].

The clinical identification of PAD is important and ankle brachial index (ABI) and/or toe brachial index (TBI) measurements will allow for its diagnosis that is more sensitive than the clinical findings of intermittent claudication since only 50% of individuals with PAD have symptoms of IC, while the other half with PAD still remain asymptomatic. Additionally, microvessel remodeling is associated with elevations of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) due to hypoxia induced factor alpha (HIF-1α) that induces VEGF.

5. Ischemia and Ischemia/Reperfusion (IR) Injury, Microvessel (Mv) Remodeling, Ischemic Neuropathy, Ischemic Skeletal Muscle (SkM) Remodeling with Myopathy and Myalgias, and Pain Perception

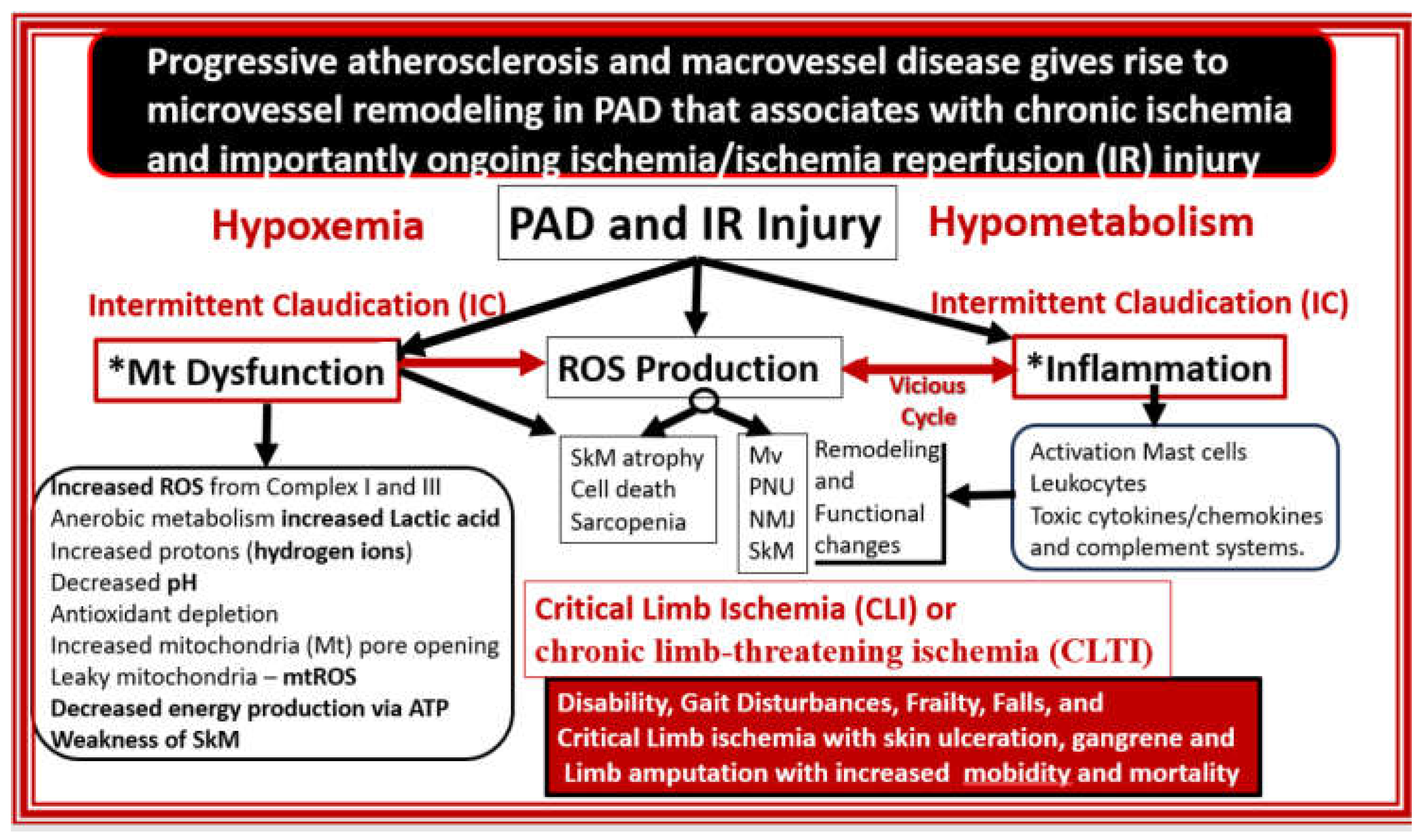

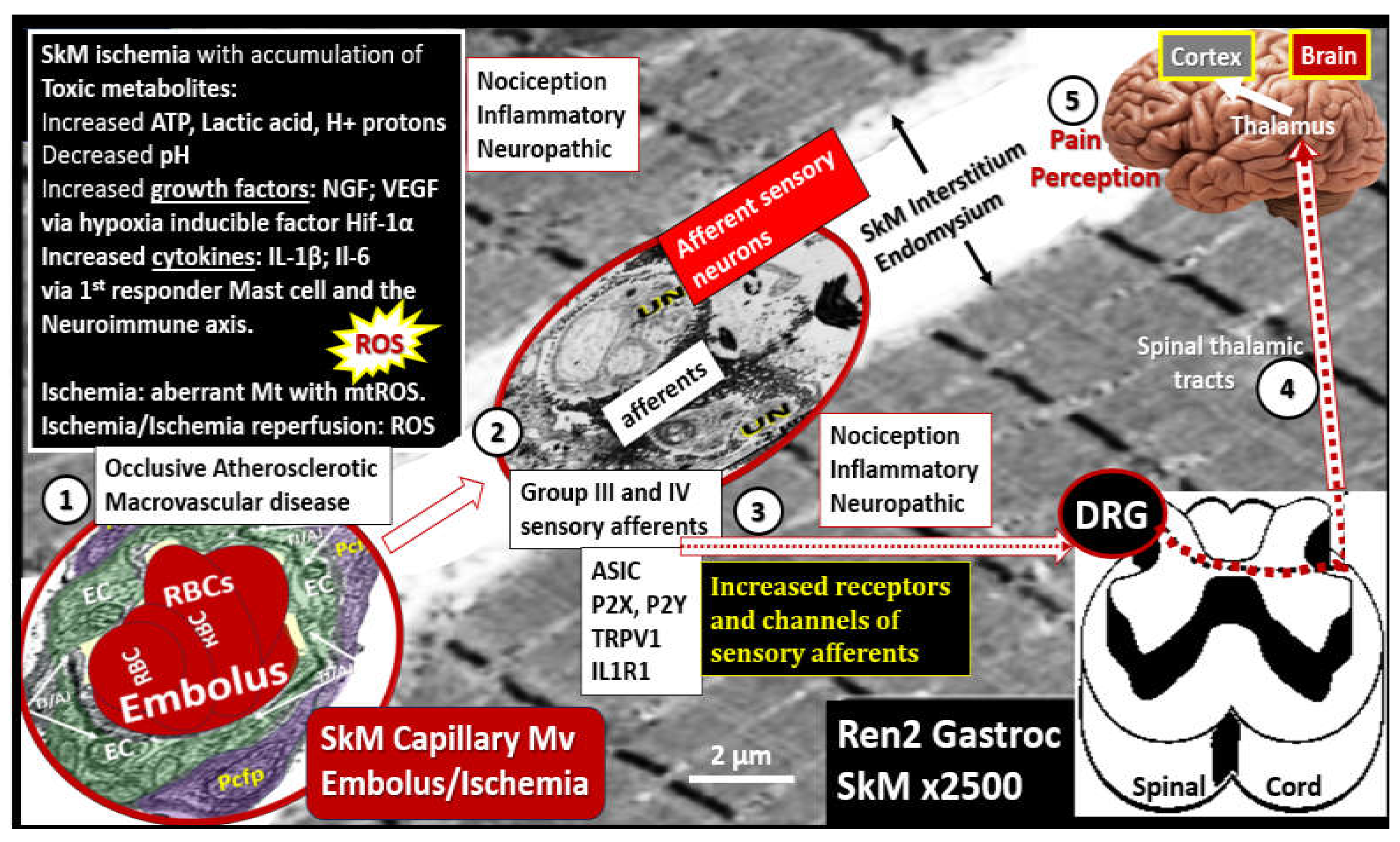

Progressive atherosclerotic macrovascular remodeling changes result in luminal narrowing and additionally contribute to Mv remodeling with EC

act/dys and decreased NO that contribute to neuronal and SkM ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Initially ischemia results in hypoperfusion with hypometabolism and hypoxia to tissues. This combined energy and oxygen deficiency or deficit contribute to both Mt dysfunction and inflammation in SkM. Notably, this brings into play the ROS-inflammation ongoing damaging vicious cycle. Mt dysfunction results in increased OxRS–ROS, which overtime depletes the natural antioxidant reserves. Anerobic metabolism contributes to increased lactic acid, H+ proton accumulation, and the initial decrease in ATP to supply cellular energy; however, over time increased ATP leakage via the opening of Mt transition pores and liberation of ATP upon cellular death allow for the signaling of afferent sensory neurons. These abnormalities along with increased cytokines and chemokines of inflammation also contribute to cellular damage and death via apoptosis-necrosis. Thus, IR injury is largely due to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased mtROS production with increased OxRS and inflammation to result in SkM remodeling (

Figure 20) [

13,

139,

140].

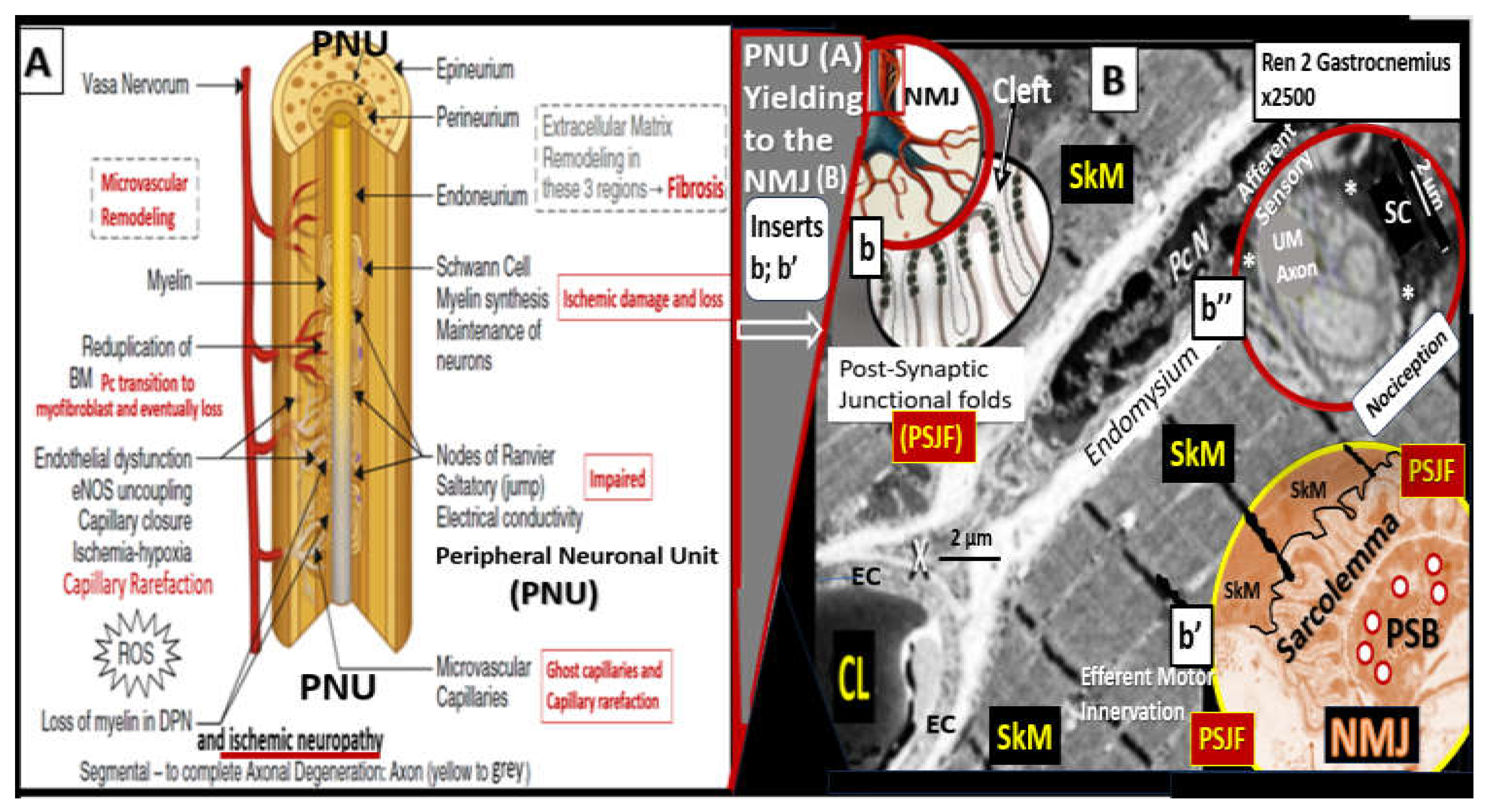

Also, Mv remodeling as previously discussed in subsection

4.3. and

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 is accompanied with a co-occurance of peripheral neuronal unit remodeling in the lower extremities in regards to the development and progression of ischemic neuropathy that occurs in intermittent claudication as it progresses to CLI in lower extremity PAD (

Figure 21) [

141,

142,

143].

Ischemic neuropathy is tightly associated with Mv remodeling and subsequent ischemia to the PNU and associated remodeling as in

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. The perception of pain in ischemic neuropathy of PAD is initially instigated via the ischemic injury, which results in the accumulation of toxic metabolic stimuli such as increased lactic acid, decreased pH, increased hydrogen protons, and ATP. Additionally, this ischemic injury is capable of instigating an activation of mast cells since they serve as the first responders to injury to create a cellular inflammatory response to injury and pain perception. In turn, these activated mast cells are capable of forming a neuroimmune axis with the sensory afferent neurons within the SkM interstitial or endomysial spaces between SkM myocytes (

Figure 22) [

144].

SkM remodeling in PAD was specifically discussed in section

4.3. Figure 17 and this section

Figure 21 and consisted primarily of skeletal muscle loss (atrophy/ischemic sarcopenia), endomysial fibrosis, myocyte lipid infiltration, and aberrant mitochondria with loss of pericapillary skeletal muscle mitochondrial mounding and loss of subsarcolemmal mitochondria with reduced ATP production [

136]. Once the lower extremity SkM is injured and remodeled due to chronic atherosclerotic macrovascular disease progression with continued luminal narrowing and Mv remodeling with ischemia occur or acute peripheral embolic events occur, there develops a sequence of signaling events, which result in the perception of pain (

Figure 23) [

145].

Incidently, these same SkM groups III and IV sensory afferents as depicted in

Figure 22 also form the sensory components of the exercise pressor reflex that involves the increase in heart rate and blood pressure following muscle contraction during casual walking and exercise [

146,

147,

148].

The two most common forms of neuropathy are diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) of diabetes (specifically T2DM) and ischemic neuropathy of PAD as discussed in subsection

2.3. and illustrated in

Figure 11. Therefore, it is appropriate to compare these two most common forms of neuropathy, especially since diabetes has a 2-fold increase in the prevalence of PAD (

Figure 24) [

67].

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

PAD is the third most common manifestation of atherosclerosis after coronary artery (CAD) and cerebrovascular disease (CVD) that currently affects between 200-250 million individuals globally, and it is considered to be an aging-associated disease [

4,

5]. Since we are now living in one of the oldest living populations in history, we can only expect to experience an even greater number of individuals to develop PAD as the global aging population expands along with the major risk factors associated with the development and progression of PAD. Further, numerous authors have pointed out that PAD is underappreciated, understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated [

150,

151,

152,

153,

154] and in the past some have even pointed out that PAD may be the last major pandemic of cardiovascular disease [

4,

5,

150]. Indeed, the diagnosis of PAD should be considered a ‘red flag’ in that it serves as a biomarker for the increased risk, morbidity, and mortality of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease that should merit earlier detection and a more aggressive and sustained treatment plan [

150].

This narrative review has examined the background of PAD and how it is associated with ECact/dys due to multiple injurious species, atherosclerosis development and progression, aging and HTN, MetS and T2DM, and tobacco smoking. Also discussed, was how ECact/dys with eNOS uncoupling associated with the decrease in vasculoprotective bioavailable nitric oxide in the development and progression of PAD. Further, the role of VAS with elastin loss and associated increase in collagen and proteoglycans, the role of transglutaminase 2, and vascular ossification and calcification and how they are involved with the development and progression of PAD was presented. Then, PAD progression via progressive macrovascular atherosclerosis accumulation with lumen encroachment to limit blood flow to the lower extremities was presented. Also, Mv remodeling as a result of increased VAS and increased pulsatile pp and impaired vasodilation with the persistence of ECact/dys and decreased NO bioavailability, which resulted in ischemia, ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury was discussed. Finally, IR injury and its effects not only on Mv remodeling but also its effects on the development of ischemic neuropathy with remodeling of the PNU and NMJ, ischemic SkM remodeling. and pain perception were presented.

In regards to future directions, we may need to focus more on the microvessel disease associated with VAS and PAD in regards to the development ischemic neuropathy and the skeletal muscle remodeling in the lower extremities. Especially, since these remodeling changes along with macrovascular remodeling changes are responsible for the horrific debilitating pain that control individual lives every day if they are not eligible for surgical revascularization.

Indeed, future directions should include methods to increase the awareness of PAD not only to individuals but also to their health care providers, especially since the study by Hirsch et al. reported that only 49% of caring physicians were aware that their patients had PAD that were identified by ankle-brachial index (ABI) studies in their large reported study with 6,979 individuals [

150]. Therefore, creative planning by primary care provider offices may be necessary in order to overcome the findings that limited time by staff and limited reimbursement were thought to be roadblocks to perform ABI testing [

155]. In the future, clinicians might consider annual or new patient vascular health questioners for their patients to fill out prior to examination. Also, regional hospitals that serve multiple out-patient clinics might consider having outpatient vascular health screening clinics that include BP recordings, blood tests to access for hyperlipidemia, and ABI measurements to overcome these concerns regarding underappreciation and underdiagnosis concerns by multiple authors in this field of study.

Because PAD is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and its association with increased prevalence of risk for morbid, mortal CVDs, newer treatment strategies for the prevention and delaying the progression in order to extend life expectancy and prevention of disability, pain, and limb loss are needed. Further, Arabzadeh et al. have discussed the possibility of utilizing strategies like regenerative medicine, cell-based therapies, nano-therapy, gene therapy, and targeted therapy, besides other traditional drug combination therapy for PAD that may be considered promising novel therapies [

156]. Also, novel or innovative treatments might be considered regarding the treatment of PAD in addition to aggressive therapy with antihypertensive medications to lower blood pressure (specifically angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers), lipid lowering strategies with the use of statins and/or monoclonal antibodies along with diet to slow the progression of atherosclerosis, dual antiplatelet therapies to prevent thromboembolism, emphasizing smoking cessation, and if possible regular exercise that are already recommended.

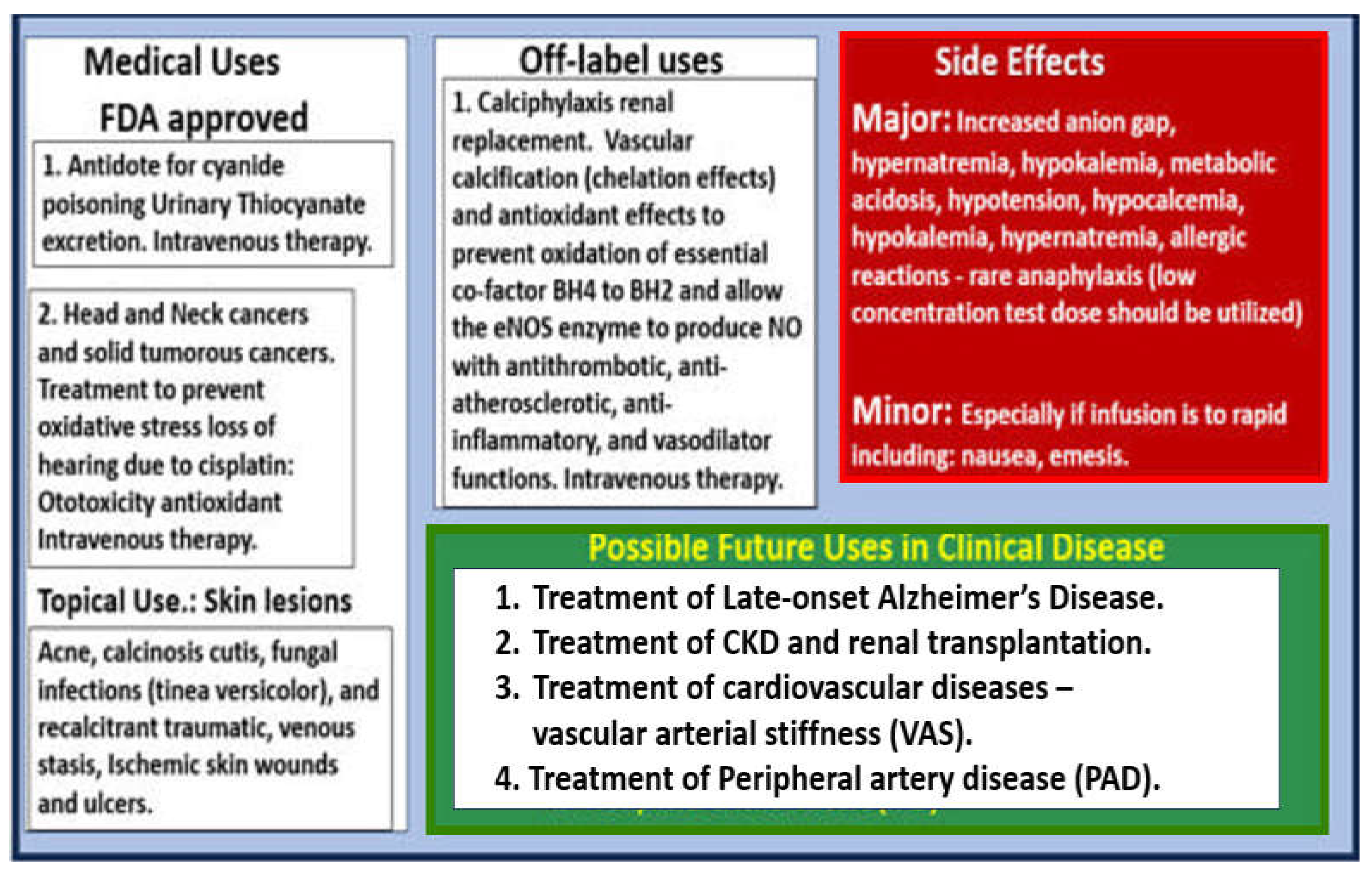

In this regard, author has recently proposed utilizing intravenous sodium thiosulfate (STS) as an innovative, multi-targeting, and repurposed therapeutic approach for the treatment of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease [

156] and has also previously suggested STS treatment for its novel antioxidant potential in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy [

142]. Because STS has been successfully and widely utilized in the global treatment of calciphylaxis [

127,

157], it is felt that STS might also be utilized as an innovative treatment modality for PAD. PAD like late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is also multifactorial in its development and progression, which involves oxidant stress, inflammation, excess calcium deposition in the development of VOC, and EC

act/dys with decreased bioavailability of NO due to excessive oxidation and dysfunction of the essential coenzyme tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) that allows the eNOS enzyme to produce NO may also benefit with the use of STS treatment (

Figure 25) [

157].

While STS has not yet been approved for the treatment of calciphylaxis in humans, it has now been sucessfully used off-label to treat calciphylaxis for just over two decades and results have been reported in the literature primarily as case reports, small case series, and reviews of calciphylaxis with discussions of STS embedded within these reviews [

127,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166,

167]. Additionally, STS has been utilized to prevent the excessive oxidative stress associated with cisplatin induced hearing loss for solid tumors and head and neck cancers [

168,

169] and also recently approved for the treatment in pediatric age populations [

170]. Also, STS has been shown to improve cardiac dysfunction and the extracellular matrix remodeling in a heart failure induced arterial venous fistula mouse model, in part, by increasing ventricular H

2S generation [

171]. Additionally, Wen et al. found that STS attenuated the progression of vascular calcification and importantly vascular arterial stiffness (VAS) in hemodialysis treated individuals [

172]. These findings by Wen et al. are pertinent in that VAS plays an important role in the development and progression of PAD. Further, ischemia and IR injury to skeletal muscle has been shown to be associated with increased OxRS and decreased H2S with SkM dysfunction and weakness. Recently, Du et al were able to demonstrate in rat models that H2S treatment was able to significantly protect rat SkM against ischemia and IR injury [

173]. These findings are important since we now know that STS serves as an H2S donor/mimetic as presented in

Figure 25 and may be able to restore SkM dysfunction and possibly weakness.

Notably, STS treatment has been consistently associated with a rapid improvement of the neuritic/ischemic pain associated with the vascular calcification of calciphylaxis in human individuals and this may be due to a restoration of eNOS enzyme function and NO production [

126,

174]. Indeed, STS has U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medical uses, off-label uses, side effects, and possible future uses in clinical diseases (

Figure 26) [

157].

Of great concern to suffering individuals and their health care providers is that a full understanding of the pathobiology for the development of nocturnal leg cramping and rest pain as occur in critical limb ischemia (CLI) or chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) still remain uncertain and therefore poses a treatment problem [

175]. While

Figure 19 provides somewhat of a spectrum and a roadmap for the development and progression of PAD, this image also points to the importance of microvessel remodeling and its relation to the development of ischemic neuropathy and ischemia-related myopathy and myalgias. Author’s personal observations have concluded that a personalized approach of utilizing a walker to prevent falling and stretching the involved cramping muscle(s) by standing upright from the supine nocturnal sleeping position to literally walk away from this horrendous cramping pain of the lower extremity myalgias. While this may not prevent future nocturnal cramping that may occur later during the night, it at least helps to prevent the active cramping at that moment in time. Additionally, author highly recommends the algorithm created by Allen and Kirby for the evaluation and treatment of nocturnal leg cramps [

175].

Over the years we have been taught that PAD-associated atherosclerosis begins distally in the abdominal aorta at the iliac artery bifurcations while concurrently developing VAS that progresses cephalad initially to the coronary arteries resulting in CVD, CAD, and congestive heart failure and then to the extracranial carotid arteries to involve the brain’s microvessels with brain EC

act/dys of the neurovascular unit to result in the co-occurance of vascular dementia and VCID that co-occurs with neurodegeneration resulting in mixed dementias (cerebrovascular disease) and stroke [

21]. In reality, while atherosclerosis is progressing cephalad it is concurrently progressing caudad to the distal lower extremities via the femoral, popliteal, peroneal, tibial, and dorsalis pedis arteries on the road to PAD and perdition. PAD frequently presents clinically with asymptomatic stenosis; however, it is known to progress from intermittent claudication to the most severe form of critical limb ischemia that leads to severe and debilitating pain due to ischemic neuropathy and SkM myopathy with the development of ischemic skin ulcerations, gangrene, and eventual limb amputation that also associates with a high risk of morbidity and mortality [

176]. Indeed, we are as old as our arteries [

177].

Abbreviations

ABI, ankle brachial index; AGE, advanced glycation endproducts; AGE/RAGE, advanced glycation endproducts and it receptor for AGE ; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; BH2, dihydrobiopterin; CAD, coronary artery disease; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CLTI, chronic limb-threating ischemia; CVD, cerebrovascular disease-cardiovascular disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; Ca2+ and Ca++, calcium cation;; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CL, capillary lumen; ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation/dysfunction; ecGCx, endothelial cell glycocalyx; EDFs, elastin-derived fragments; EDPs, elastin-derived peptides eHTN, essential hypertension; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; Hif-1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha; HTN, hypertension; IC, intermittent claudication; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IR, ischemia reperfusion; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MMP(s), matrix metalloproteinases; MMP-2,-9, matrix metalloproteinase-2,-9; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mtROS, mitochondrial ROS; mod-LDL-C, modified low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Mv, microvessel; NF-kB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; pCC, peripheral cytokines chemokines; PGNs, proteoglycans; PNU, peripheral neuronal unit; pp, pulsatile pulse pressure; pWV, pulse wave velocity; RAGE, receptor for AGE; ROS, reactive oxygen species, RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; rPVACfp/ef, reactive perivascular astrocyte foot processes/endfeet; rPVMΦ, reactive resident perivascular macrophages; RSI, reactive species interactome; SkM, skeletal muscle; STS, sodium thiosulfate; SVD, cerebral small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TG2, transglutaminase 2; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VaD, vascular dementia; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VOC, vascular ossification calcification; VSMC(s), vascular smooth muscle cells; WMH, white matter hyperintensities.

Figure 1.

Multiple injurious species in the plasma result in systemic endothelial cell (SEC) activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) resulting in a proinflammatory endothelium with decreased nitric oxide (NO). Note that the initial endothelial cell glycocalyx surface layer (a gel-like layer of proteoglycans, glycoproteins and extracellular matrix components) is absent from his image due to the size constraint of the figure. Further, note that tobacco smoke was left out due to the large numbers of chemicals that are found within smoke; nevertheless, a large number of highly unstable reactive and damaging free radicals are found in smoke that instigates injury to the endothelium. Image reproduced with permission by CC4.0 [

17,

19,

21]. Ang II, angiotensin 2; AGE/RAGE, advanced glycation endproducts and its receptor RAGE; AJ, adherens junction; aMMPs, activated matrix metalloproteinases; CCL2, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; downward arrows, decrease; ecGCx, endothelial cell glycocalyx; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; modLDL-C, modified low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; N, nucleus; O

2̇̄ , superoxide anion; ONOO

−, OxRS, oxidative redox stress; peroxinitrite; pCC, peripheral cytokines, chemokines; pp, pulsatile pulse pressure; RBC, red blood cell; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RSI, reactive species interactome; upward arrows, increase; SEC, systemic endothelial cell(s); T, transcytosis; VAS, vascular arterial stiffness; VCAM-1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule -1; VE-cadherins, vascular endothelial cell cadherins; WBC, white blood cell; ZO-1 zona occludins 1.

Figure 1.

Multiple injurious species in the plasma result in systemic endothelial cell (SEC) activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) resulting in a proinflammatory endothelium with decreased nitric oxide (NO). Note that the initial endothelial cell glycocalyx surface layer (a gel-like layer of proteoglycans, glycoproteins and extracellular matrix components) is absent from his image due to the size constraint of the figure. Further, note that tobacco smoke was left out due to the large numbers of chemicals that are found within smoke; nevertheless, a large number of highly unstable reactive and damaging free radicals are found in smoke that instigates injury to the endothelium. Image reproduced with permission by CC4.0 [

17,

19,

21]. Ang II, angiotensin 2; AGE/RAGE, advanced glycation endproducts and its receptor RAGE; AJ, adherens junction; aMMPs, activated matrix metalloproteinases; CCL2, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; downward arrows, decrease; ecGCx, endothelial cell glycocalyx; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; modLDL-C, modified low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; N, nucleus; O

2̇̄ , superoxide anion; ONOO

−, OxRS, oxidative redox stress; peroxinitrite; pCC, peripheral cytokines, chemokines; pp, pulsatile pulse pressure; RBC, red blood cell; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RSI, reactive species interactome; upward arrows, increase; SEC, systemic endothelial cell(s); T, transcytosis; VAS, vascular arterial stiffness; VCAM-1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule -1; VE-cadherins, vascular endothelial cell cadherins; WBC, white blood cell; ZO-1 zona occludins 1.

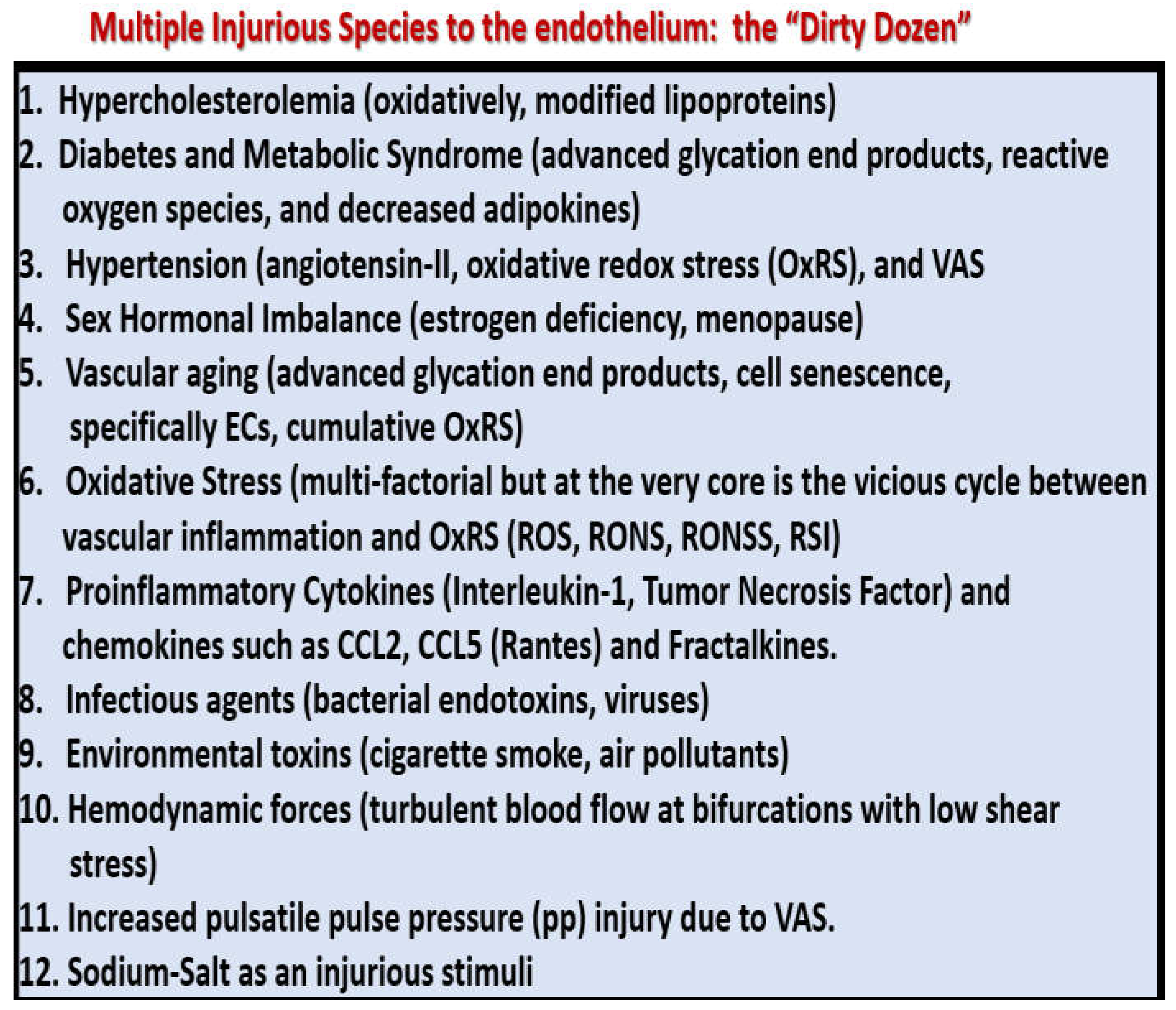

Figure 2.

Multiple injurious species: “The dirty dozen” affecting the systemic endothelium. Regarding number eight, the ultimate bacterial endotoxin is lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and that number 12, sodium acts as an injurious stimulus via the endothelial sodium channel (eNAC). CCL2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CCL-5, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (RANTES); ECs, endothelial cells; Fractalkine(s), chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; RSI, reactive species interactome; VAS, vascular arterial stiffening.

Figure 2.

Multiple injurious species: “The dirty dozen” affecting the systemic endothelium. Regarding number eight, the ultimate bacterial endotoxin is lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and that number 12, sodium acts as an injurious stimulus via the endothelial sodium channel (eNAC). CCL2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CCL-5, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (RANTES); ECs, endothelial cells; Fractalkine(s), chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; RSI, reactive species interactome; VAS, vascular arterial stiffening.

Figure 3.

EC

act/dys results in a decrease of bioavailable endothelial nitric oxide (NO), which sounds an alarm to ECs and the cells of the vessel wall. In addition to the seven detrimental effects of decreased nitric oxide also note the important role of increased oxidative redox stress (OxRS) and its important role in uncoupling the NO generating eNOS enzyme reaction that requires its essential co-enzyme tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to be totally reduced. If BH4 is oxidized to dihydrobiopterin (BH2) via excessive oxidative redox stress (OxRS) the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme reaction will not produce NO. Also, note the pulse wave velocity wave forms on the left-hand side of the image that illustrates the premature arrival of the reflected pulse wave contributing to the increased pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) to further result in vascular injury and remodeling with increased vascular arterial stiffening of peripheral artery disease. Pulse wave velocity image lower left-hand side reproduced with permission by CC 4.0 [

22]. AFM, atomic force microscopy; Asterisk, indicates emphasis; BP, blood pressure; EC

act/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; EC(s), endothelial cells; Ext, extremities; H, heart; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; PAD, peripheral artery disease; Pc, pericyte; V, vessel-vascular; PGN, proteoglycan; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 3.

EC

act/dys results in a decrease of bioavailable endothelial nitric oxide (NO), which sounds an alarm to ECs and the cells of the vessel wall. In addition to the seven detrimental effects of decreased nitric oxide also note the important role of increased oxidative redox stress (OxRS) and its important role in uncoupling the NO generating eNOS enzyme reaction that requires its essential co-enzyme tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to be totally reduced. If BH4 is oxidized to dihydrobiopterin (BH2) via excessive oxidative redox stress (OxRS) the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme reaction will not produce NO. Also, note the pulse wave velocity wave forms on the left-hand side of the image that illustrates the premature arrival of the reflected pulse wave contributing to the increased pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) to further result in vascular injury and remodeling with increased vascular arterial stiffening of peripheral artery disease. Pulse wave velocity image lower left-hand side reproduced with permission by CC 4.0 [

22]. AFM, atomic force microscopy; Asterisk, indicates emphasis; BP, blood pressure; EC

act/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; EC(s), endothelial cells; Ext, extremities; H, heart; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; PAD, peripheral artery disease; Pc, pericyte; V, vessel-vascular; PGN, proteoglycan; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

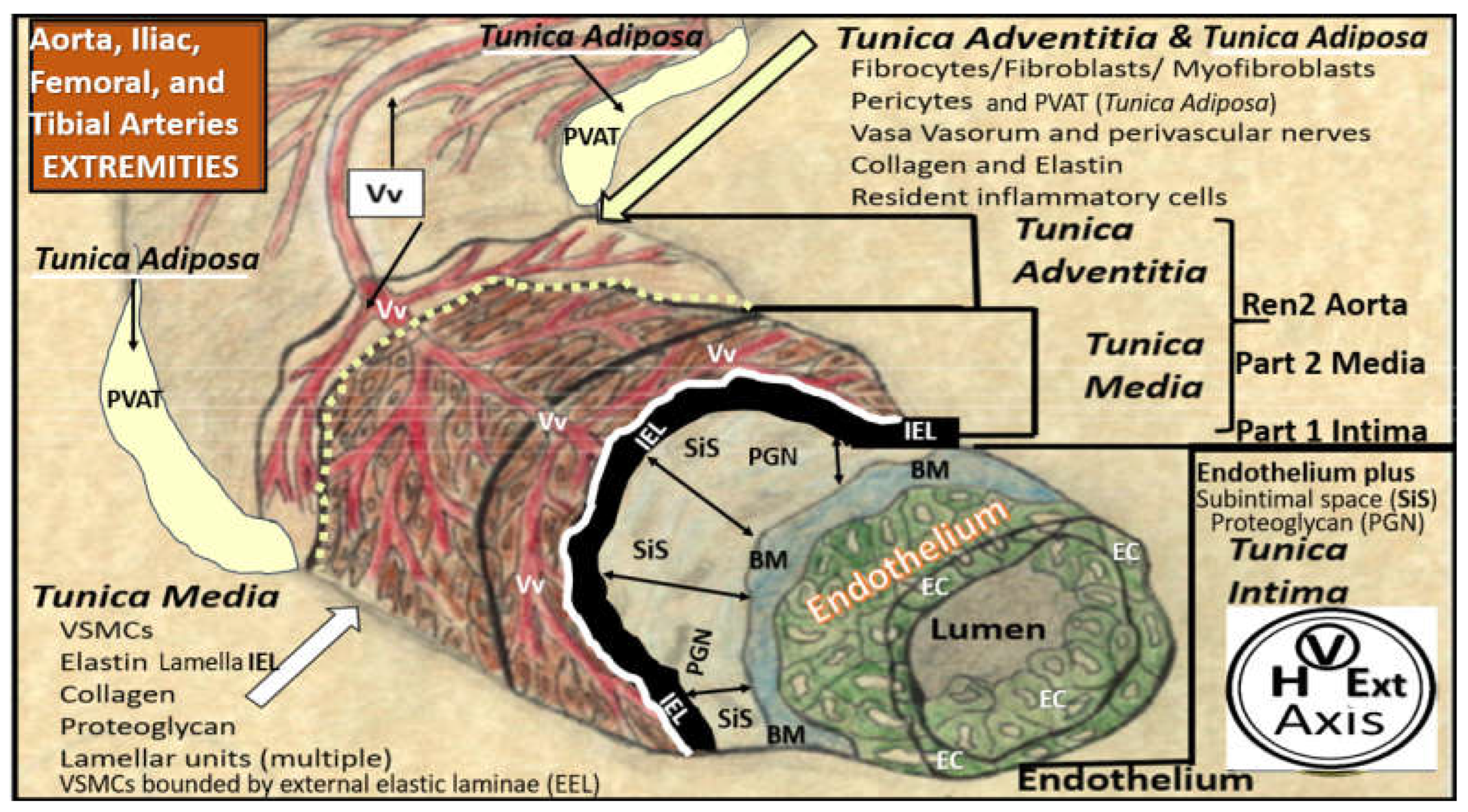

Figure 4.

A pull-out vessel model demonstrating the three major layers of arteries and how they are structurally interrelated. This figure illustrates the lumen that is surrounded by systemic endothelial cells (SECs pseudo-colored green) that have a basement membrane (BM) pseudo-colored blue, and the proteoglycan (PGN)-rich intima-subintimal space (SiS noted by double arrows). These three tunica layers begin most luminally with the tunica intima composed of the endothelium and its basement membrane the subendothelial intimal space where atherosclerosis is known to originate and expand. Next the thickened black line forms the internal elastic lamina (IEL), which is demarcated by the bold white line, which separates the intima from the tunica media that encircles the artery and serves to allow elastic recoil of the artery during contraction and relaxation. Once the vessel is stretched along with its multiple layers of the elastin lamella that bound the lamellar units containing the vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) pseudo-colored red and denoted by open white arrows that comprise the second tunica that is bound abluminally by the external elastic lamina (yellow dashed line). The most abluminal and third tunica is the tunica adventitia, which is demarcated by the yellow dashed line luminally and the perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) of the tunica adventitia that contains loose connective tissue with multiple cells including pericytes, leukocytes, and occasional mast cells through which, the vasa vasorum (Vv) flows as it penetrates the media to be referred to as the vessel within the vessel. The perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT underlined and pseudo-colored yellow) contains visceral adipocytes and extracellular matrix) is an extension of the tunica adventitia; however, some feel that it merits the distinction to be called the tunica adiposa due to its proinflammatory-metainflammation potential to result in aberrant arterial remodeling from the outside in. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

1,

21,

27]. EC, endothelial cell; EL, elastin lamina; HVExt, heart-vessel-extremity axis; PGN, proteoglycan; Ren2 rat part I and II, ultrastructure study of the young male transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 (Ren2) rat hypertensive model: Aorta intima Part I and media-adventitia Part II with elevated renin, angiotensin II, angiotensin type-1 (AT-1) receptors, and aldosterone; Vv, vasa vasorum.

Figure 4.

A pull-out vessel model demonstrating the three major layers of arteries and how they are structurally interrelated. This figure illustrates the lumen that is surrounded by systemic endothelial cells (SECs pseudo-colored green) that have a basement membrane (BM) pseudo-colored blue, and the proteoglycan (PGN)-rich intima-subintimal space (SiS noted by double arrows). These three tunica layers begin most luminally with the tunica intima composed of the endothelium and its basement membrane the subendothelial intimal space where atherosclerosis is known to originate and expand. Next the thickened black line forms the internal elastic lamina (IEL), which is demarcated by the bold white line, which separates the intima from the tunica media that encircles the artery and serves to allow elastic recoil of the artery during contraction and relaxation. Once the vessel is stretched along with its multiple layers of the elastin lamella that bound the lamellar units containing the vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) pseudo-colored red and denoted by open white arrows that comprise the second tunica that is bound abluminally by the external elastic lamina (yellow dashed line). The most abluminal and third tunica is the tunica adventitia, which is demarcated by the yellow dashed line luminally and the perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) of the tunica adventitia that contains loose connective tissue with multiple cells including pericytes, leukocytes, and occasional mast cells through which, the vasa vasorum (Vv) flows as it penetrates the media to be referred to as the vessel within the vessel. The perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT underlined and pseudo-colored yellow) contains visceral adipocytes and extracellular matrix) is an extension of the tunica adventitia; however, some feel that it merits the distinction to be called the tunica adiposa due to its proinflammatory-metainflammation potential to result in aberrant arterial remodeling from the outside in. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

1,

21,

27]. EC, endothelial cell; EL, elastin lamina; HVExt, heart-vessel-extremity axis; PGN, proteoglycan; Ren2 rat part I and II, ultrastructure study of the young male transgenic heterozygous (mRen2)27 (Ren2) rat hypertensive model: Aorta intima Part I and media-adventitia Part II with elevated renin, angiotensin II, angiotensin type-1 (AT-1) receptors, and aldosterone; Vv, vasa vasorum.

Figure 6.

Malignant-like invasion of vasa vasorum (Vv) to result in intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) of a type VI plaque to result in thrombosis and distal ischemia. Note the increased angiogenesis of the hand-drawn vessel on the left and how it invades the type VI plaque on the right to result in a type VI thin cap atheroma prone to rupture resulting in thrombosis. This process of Vv invasion results in a lipid laden, prothrombotic, acidic, angiogenic, inflamed, ‘hot plaque’ due to IPH, Revised figures provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

27]. EC

act/dys, endothelial activation and dysfunction; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ph, pH or potential of hydrogen and a measure of acidity; PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue; NO, nitric oxide; perivascular adipose tissue; OxRS, oxidative redox stress.

Figure 6.

Malignant-like invasion of vasa vasorum (Vv) to result in intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) of a type VI plaque to result in thrombosis and distal ischemia. Note the increased angiogenesis of the hand-drawn vessel on the left and how it invades the type VI plaque on the right to result in a type VI thin cap atheroma prone to rupture resulting in thrombosis. This process of Vv invasion results in a lipid laden, prothrombotic, acidic, angiogenic, inflamed, ‘hot plaque’ due to IPH, Revised figures provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

27]. EC

act/dys, endothelial activation and dysfunction; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ph, pH or potential of hydrogen and a measure of acidity; PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue; NO, nitric oxide; perivascular adipose tissue; OxRS, oxidative redox stress.

Figure 7.

In femoral-popliteal arteries acute thrombi and atherosclerotic plaques are more common in contrast to infra-popliteal arteries (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, peroneal, and dorsalis pedis arteries) where chronic thrombosis and emboli predominate with medial calcifications and fewer atherosclerotic plaques. Note circular insert (upper far-left) that depicts the abdominal aorta, the iliac bifurcations and the femoral arteries. In the regular magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) (far-left) note the yellow horizontal line that separates the superior femoral-popliteal (FEM-POP) regions from the more distal infra-popliteal (INFRA-POP) regions. a, artery; ATA, anterior tibial artery’ ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FEM, femoral artery; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; NO, nitric oxide; PA, peroneal artery; PTA, posterior tibial artery; TPT, tibia peroneal trunk; STS, sodium thiosulfate.

Figure 7.

In femoral-popliteal arteries acute thrombi and atherosclerotic plaques are more common in contrast to infra-popliteal arteries (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, peroneal, and dorsalis pedis arteries) where chronic thrombosis and emboli predominate with medial calcifications and fewer atherosclerotic plaques. Note circular insert (upper far-left) that depicts the abdominal aorta, the iliac bifurcations and the femoral arteries. In the regular magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) (far-left) note the yellow horizontal line that separates the superior femoral-popliteal (FEM-POP) regions from the more distal infra-popliteal (INFRA-POP) regions. a, artery; ATA, anterior tibial artery’ ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FEM, femoral artery; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; NO, nitric oxide; PA, peroneal artery; PTA, posterior tibial artery; TPT, tibia peroneal trunk; STS, sodium thiosulfate.

Figure 8.

The essential hypertension (eHTN-HTN) wheel. Insulin resistance (IR) presents as a central core feature of the HTN wheel as it is also the central core feature in the metabolic syndrome (MetS). IR is a central mediator for the development of HTN and impaired fasting glucose (IFG)-impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)–type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), along with multiple metabolic and clinical boxed-in clinical conditions that surround the outer positions of this wheel. Extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and PAD are placed at the top of the wheel because they are believed to be a driving force behind the subsequent clinical end-organ remodeling and disease in addition to the development of HTN. Endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) at the bottom of the wheel results in increased peroxynitrite (ONOO

−) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (asterisk). Peroxynitrite is generated by the reaction between superoxide and NO. Note the multiple clinical diseases that are associated with HTN, and the wheel depicts the interconnectedness between HTN and the multiple clinical disease states, including vascular stiffening and PAD. Thus, obesity, IR, HTN, and T2DM are not to be underestimated. The wheel background icon was chosen because it goes round and round, and over time it just keeps on turning and results in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS), PAD, and end-organ damage in the heart-vessel-extremity axis. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

21]. Asterisk, indicates emphasis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Dd, diastolic dysfunction

; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease; MI, myocardial infarction; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; O

2•–, superoxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; PAD, peripheral artery disease;.

Figure 8.

The essential hypertension (eHTN-HTN) wheel. Insulin resistance (IR) presents as a central core feature of the HTN wheel as it is also the central core feature in the metabolic syndrome (MetS). IR is a central mediator for the development of HTN and impaired fasting glucose (IFG)-impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)–type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), along with multiple metabolic and clinical boxed-in clinical conditions that surround the outer positions of this wheel. Extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and PAD are placed at the top of the wheel because they are believed to be a driving force behind the subsequent clinical end-organ remodeling and disease in addition to the development of HTN. Endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) at the bottom of the wheel results in increased peroxynitrite (ONOO

−) and decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (asterisk). Peroxynitrite is generated by the reaction between superoxide and NO. Note the multiple clinical diseases that are associated with HTN, and the wheel depicts the interconnectedness between HTN and the multiple clinical disease states, including vascular stiffening and PAD. Thus, obesity, IR, HTN, and T2DM are not to be underestimated. The wheel background icon was chosen because it goes round and round, and over time it just keeps on turning and results in vascular arterial stiffening (VAS), PAD, and end-organ damage in the heart-vessel-extremity axis. Modified image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

21]. Asterisk, indicates emphasis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Dd, diastolic dysfunction

; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; LOAD, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease; MI, myocardial infarction; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; O

2•–, superoxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; PAD, peripheral artery disease;.

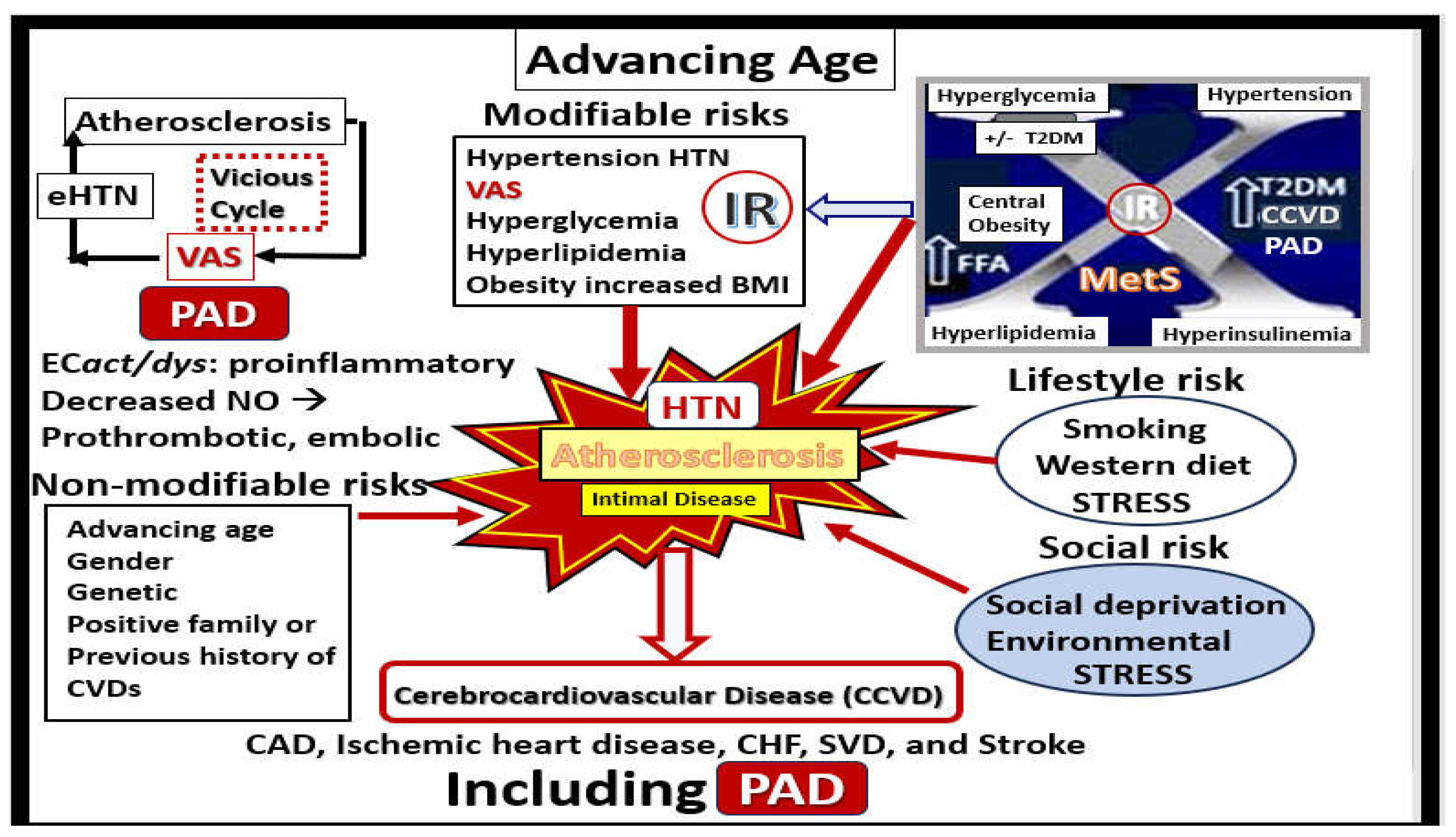

Figure 9.

Multiple risk factors for the development of peripheral artery disease (PAD) include both hypertension (HTN), atherosclerosis, and the metabolic syndrome (MetS). Note how the metabolic syndrome (MetS) upper right is a major supplier for the modifiable risk factors for the development cerebrocardiovascular diseases (CCVDs) including PAD of the extremities. Also note the non-modifiable risks lower-left and the lifestyle and social risks lower-right. Importantly, note the importance of endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) and how the uncoupling of the eNOS reaction leads to a decrease in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), which contributes to a prothrombotic state and thrombotic emboli due to decreased NO. Also, note the importance of the vicious cycle upper left between hypertension, atherosclerosis, and vascular stiffness (VAS). Modified image supplied with permission by 4.0 [

21]. CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD(s), cardiovascular diseases; ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; FFA, free fatty acids; SVD, small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 9.

Multiple risk factors for the development of peripheral artery disease (PAD) include both hypertension (HTN), atherosclerosis, and the metabolic syndrome (MetS). Note how the metabolic syndrome (MetS) upper right is a major supplier for the modifiable risk factors for the development cerebrocardiovascular diseases (CCVDs) including PAD of the extremities. Also note the non-modifiable risks lower-left and the lifestyle and social risks lower-right. Importantly, note the importance of endothelial cell activation and dysfunction (EC

act/dys) and how the uncoupling of the eNOS reaction leads to a decrease in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), which contributes to a prothrombotic state and thrombotic emboli due to decreased NO. Also, note the importance of the vicious cycle upper left between hypertension, atherosclerosis, and vascular stiffness (VAS). Modified image supplied with permission by 4.0 [

21]. CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD(s), cardiovascular diseases; ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; FFA, free fatty acids; SVD, small vessel disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

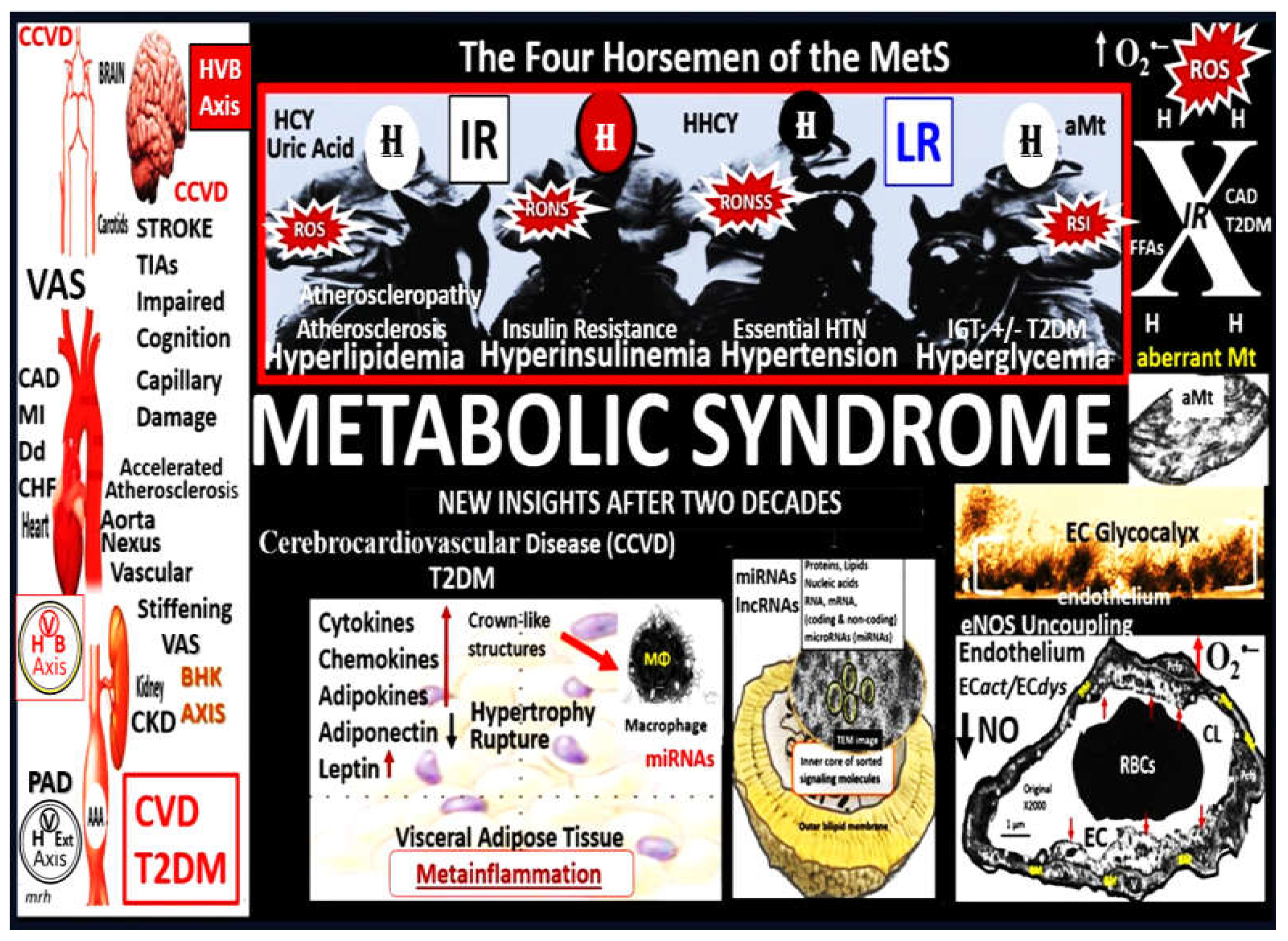

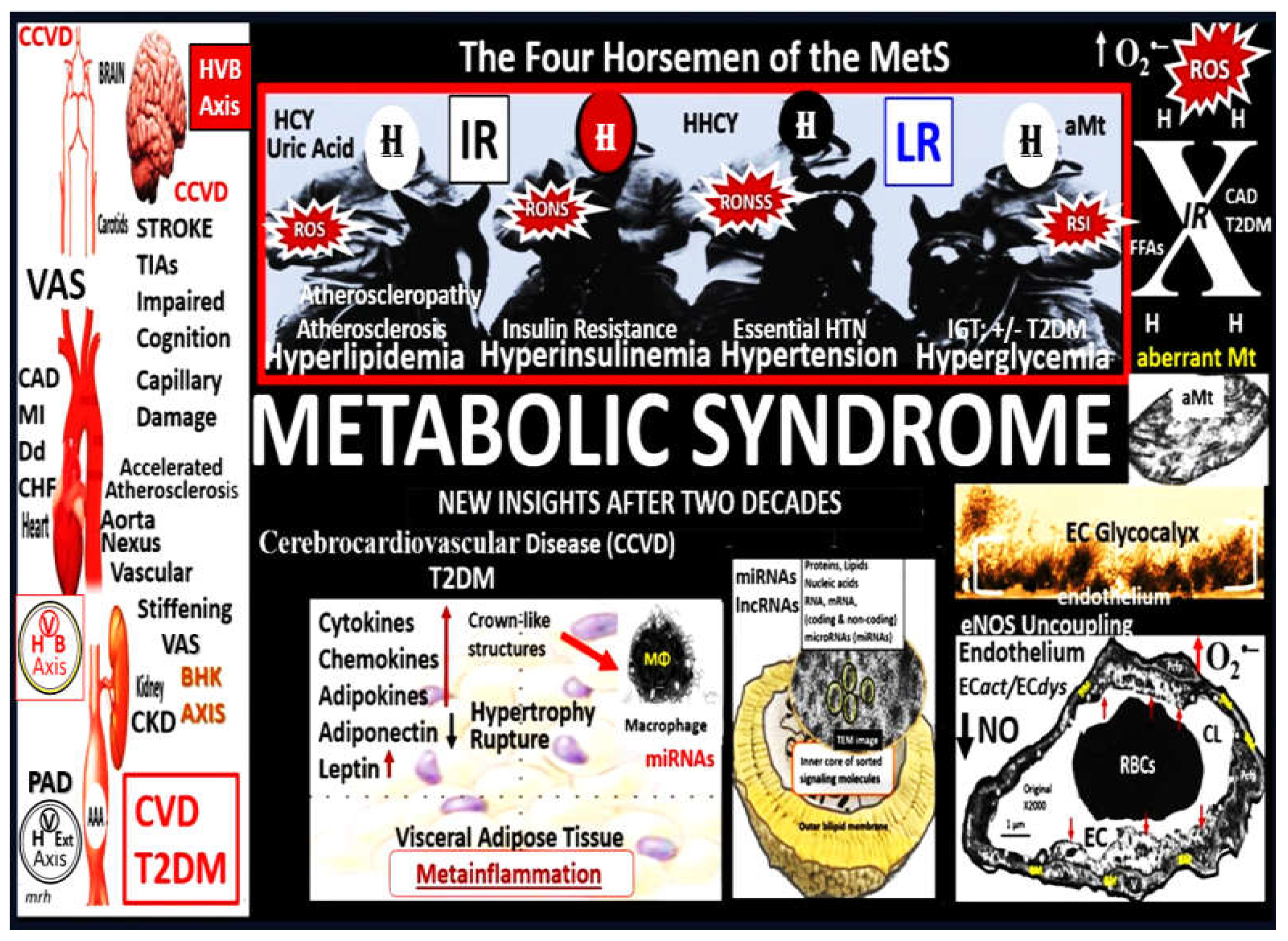

Figure 10.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS). The “H” phenomenon (four horsemen) of the MetS includes: I. Hyperlipidemia (obesity and the atherogenic lipid triad); II. Hyperinsulinemia (insulin resistance-(IR)), III. Hypertension (HTN); IV. Hyperglycemia (impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) +/- type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as well as, the clustering effect of each of the multiple variables of the MetS itself and contribute to extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and peripheral artery disease (PAD). Additionally, IR and LR contribute to vascular stiffening primarily through the actions of obesity on the development of VAS. Modified graphic abstract image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

57]. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; aMt, aberrant mitochondria; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CL, capillary lumen; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BHK, brain-heart-kidney axis; CHF, congestive heart failure; Dd, diastolic dysfunction; EC, endothelial cell; FFA, free fatty acids; H, hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia; HCY, homocysteine; HHCY, hyperhomocyteinemia; HVExt, heart-vessel-extremity axis; HVB, heart-vessel-brain axis; IR, insulin resistance; LR, leptin resistance; lncRNAs, long non-coding ribonucleic acids MI, myocardial infarction; miRNAs, micro ribonucleic acids; MΦ, macrophage; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; RSI, reactive species interactome.

Figure 10.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS). The “H” phenomenon (four horsemen) of the MetS includes: I. Hyperlipidemia (obesity and the atherogenic lipid triad); II. Hyperinsulinemia (insulin resistance-(IR)), III. Hypertension (HTN); IV. Hyperglycemia (impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) +/- type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as well as, the clustering effect of each of the multiple variables of the MetS itself and contribute to extracranial vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and peripheral artery disease (PAD). Additionally, IR and LR contribute to vascular stiffening primarily through the actions of obesity on the development of VAS. Modified graphic abstract image provided with permission by CC 4.0 [

57]. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; aMt, aberrant mitochondria; CCVD, cerebrocardiovascular disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CL, capillary lumen; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BHK, brain-heart-kidney axis; CHF, congestive heart failure; Dd, diastolic dysfunction; EC, endothelial cell; FFA, free fatty acids; H, hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia; HCY, homocysteine; HHCY, hyperhomocyteinemia; HVExt, heart-vessel-extremity axis; HVB, heart-vessel-brain axis; IR, insulin resistance; LR, leptin resistance; lncRNAs, long non-coding ribonucleic acids MI, myocardial infarction; miRNAs, micro ribonucleic acids; MΦ, macrophage; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RONS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen species; RONSS, reactive oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur species; RSI, reactive species interactome.

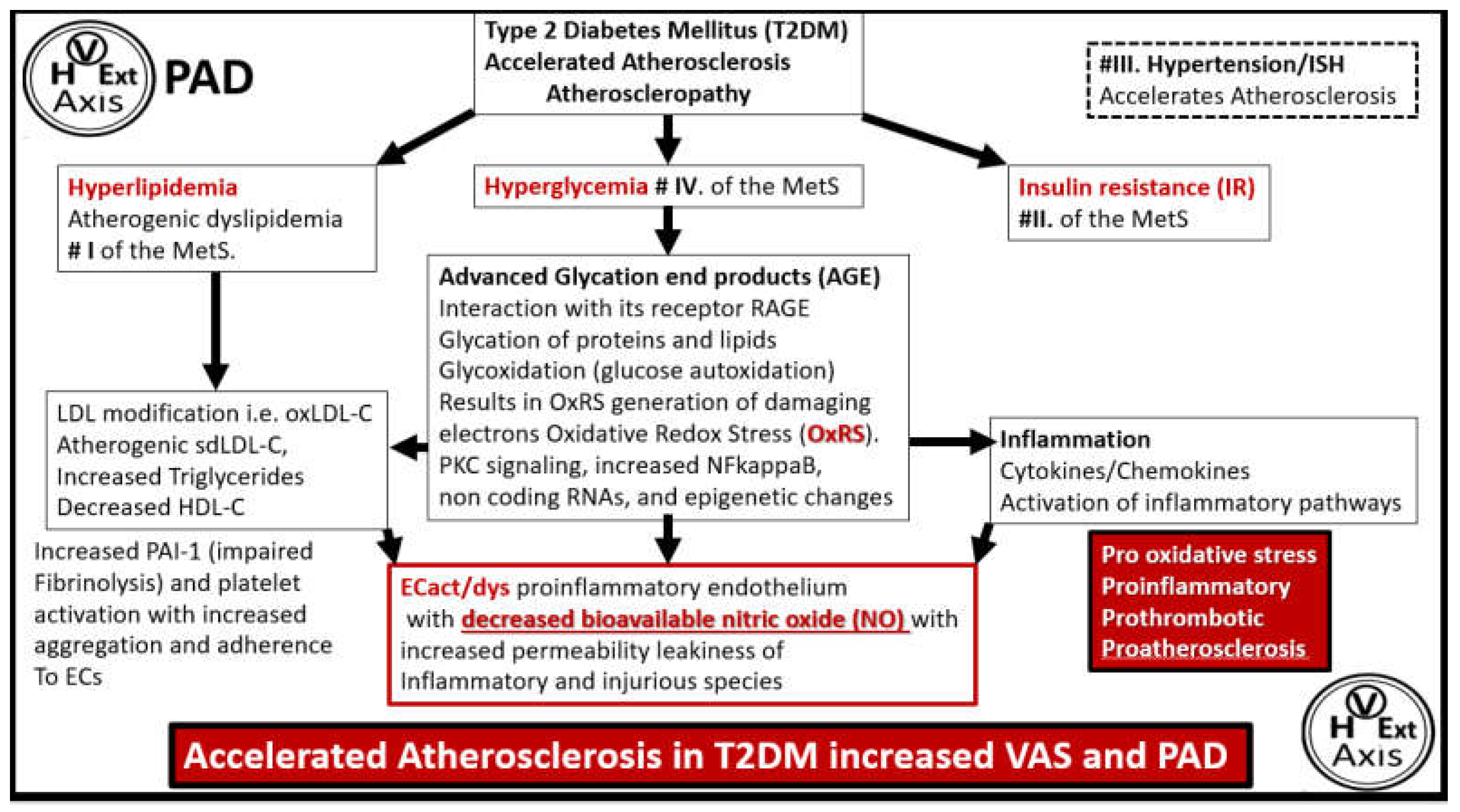

Figure 11.

Schematic for how type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) associates with accelerated atherosclerosis and a two-fold increase in prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD). Note that ECact/dys is outlined in red color to highlight its importance because EC activation (proinflammatory endothelium) and dysfunction (decrease of protective bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) of the endothelium) of the vascular endothelium is the hallmark of atherosclerosis in T2DM. ECs, endothelial cells; ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; IR, insulin resistance; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; NFkappaB, nuclear factor kappa B; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products. .

Figure 11.

Schematic for how type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) associates with accelerated atherosclerosis and a two-fold increase in prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD). Note that ECact/dys is outlined in red color to highlight its importance because EC activation (proinflammatory endothelium) and dysfunction (decrease of protective bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) of the endothelium) of the vascular endothelium is the hallmark of atherosclerosis in T2DM. ECs, endothelial cells; ECact/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; IR, insulin resistance; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; NFkappaB, nuclear factor kappa B; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products. .

Figure 12.

Nitric oxide has at least five positive and protective effects on the arterial vessel wall. Antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, vasodilatory, and proangiogenic effects. BH4. Tetrahydrobiopterin necessary coenzyme for eNOS enzyme; EC, endothelial cell; eNOS, endothelial nitroxide synthase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell. .

Figure 12.

Nitric oxide has at least five positive and protective effects on the arterial vessel wall. Antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, vasodilatory, and proangiogenic effects. BH4. Tetrahydrobiopterin necessary coenzyme for eNOS enzyme; EC, endothelial cell; eNOS, endothelial nitroxide synthase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell. .

Figure 13.

Development of vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) in peripheral artery disease (PAD). The process of VAS development begins with the presence of injurious species within the lumen and note the pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) boxed-in red along with the dirty dozen from

Figure 2 along with neurohormonal and sympathetic stimuli with increased shear stress (step 1). Next, the endothelium becomes activated and dysfunctional (EC

act/dys) with increased permeability (step 2), which allows these injurious species to penetrate the vessel wall with subsequent structural remodeling and dysfunctional steps that follow (steps 3-5) in the development of VAS. Note the increased pulsatile pp (red arrows) and pulse wave velocity (pWV) upper right insert that play an important role in both macro-and microvessel aberrant remodeling with dysfunction and damage in VAS. Incidently, it is important to note that both hypertension and atherosclerosis also contribute to the development of VAS. Modified background image provided with permission by 4.0 [

108]. AGE(s), advanced glycation end-products; CaPO4, calcium phosphate; EDFs, elastin-derived fragments; EDPs, elastin-derived peptides; I-CAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; NO, MΦ, macrophage; nitric oxide; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta-one; VOC, vascular ossification-calcification; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells. .

Figure 13.

Development of vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) in peripheral artery disease (PAD). The process of VAS development begins with the presence of injurious species within the lumen and note the pulsatile pulse pressure (pp) boxed-in red along with the dirty dozen from

Figure 2 along with neurohormonal and sympathetic stimuli with increased shear stress (step 1). Next, the endothelium becomes activated and dysfunctional (EC

act/dys) with increased permeability (step 2), which allows these injurious species to penetrate the vessel wall with subsequent structural remodeling and dysfunctional steps that follow (steps 3-5) in the development of VAS. Note the increased pulsatile pp (red arrows) and pulse wave velocity (pWV) upper right insert that play an important role in both macro-and microvessel aberrant remodeling with dysfunction and damage in VAS. Incidently, it is important to note that both hypertension and atherosclerosis also contribute to the development of VAS. Modified background image provided with permission by 4.0 [

108]. AGE(s), advanced glycation end-products; CaPO4, calcium phosphate; EDFs, elastin-derived fragments; EDPs, elastin-derived peptides; I-CAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; NO, MΦ, macrophage; nitric oxide; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta-one; VOC, vascular ossification-calcification; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells. .

Figure 14.

A collection of representitive ultrastructural images that are only meant to illustrate the following: Endothelial cell (EC) lifting and separation in panel A, elastin separation and degradation in panel B, the formation of elastin-derived fragments (EDFs) via elastolysis that are a rich source of elastin-derived peptides (EDPs) in panel C, which represent remodeling changes at the endothelium and intima regions, which involves both the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and the elastin that forms the boundaries of the elastin lamellar units containing vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) sandwiched between the elastin lamella (EL). Then the phenotypic shift of VSMCs is illustrated in panel C, phenotype shift of VSMCs in panel D and the migratory “red dragon” VSMC representing the migratory potential and the creation of neointima just abluminally to the EC cell in panel E, and the migratory VSMCs creating and invading the neointimal space in panel F. Images A-C are from the obese, insulin resistant female diabetic db/db mouse models at 20 weeks of age without hypertension and images D-G are from a male genetic-induced hypertensive Ren2 rat at 14 weeks of age. Modified images panels A-C and panels D-F are provided with permission respectfully by CC4.0 [

21,

109,

110]. Asterisks, elastin splitting and degradation; DBC, female, obese, insulin resistant diabetic

db/db models at 20-weeks of age; Mt, mitochondria; N, nucleus; PGN(s), proteoglycans; Ren2, male transgenic hypertensive models TGR(mRen2)27 rat at 10-weeks of age; ROS, reactive oxygen species; V, vacuole; v, vesicle; WP, Weible-Palade bodies.

Figure 14.

A collection of representitive ultrastructural images that are only meant to illustrate the following: Endothelial cell (EC) lifting and separation in panel A, elastin separation and degradation in panel B, the formation of elastin-derived fragments (EDFs) via elastolysis that are a rich source of elastin-derived peptides (EDPs) in panel C, which represent remodeling changes at the endothelium and intima regions, which involves both the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and the elastin that forms the boundaries of the elastin lamellar units containing vascular smooth muscle cell(s) (VSMCs) sandwiched between the elastin lamella (EL). Then the phenotypic shift of VSMCs is illustrated in panel C, phenotype shift of VSMCs in panel D and the migratory “red dragon” VSMC representing the migratory potential and the creation of neointima just abluminally to the EC cell in panel E, and the migratory VSMCs creating and invading the neointimal space in panel F. Images A-C are from the obese, insulin resistant female diabetic db/db mouse models at 20 weeks of age without hypertension and images D-G are from a male genetic-induced hypertensive Ren2 rat at 14 weeks of age. Modified images panels A-C and panels D-F are provided with permission respectfully by CC4.0 [

21,

109,

110]. Asterisks, elastin splitting and degradation; DBC, female, obese, insulin resistant diabetic

db/db models at 20-weeks of age; Mt, mitochondria; N, nucleus; PGN(s), proteoglycans; Ren2, male transgenic hypertensive models TGR(mRen2)27 rat at 10-weeks of age; ROS, reactive oxygen species; V, vacuole; v, vesicle; WP, Weible-Palade bodies.

Figure 15.

Possible sequence of events leading to the development and progression of peripheral artery disease (PAD). The sequence of events begins with the injury to the endothelium at the top of the figure that was previously presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and is followed sequentially by the six steps and representative images (1-6) with explanation to the left-hand side to arrive at the

magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) images of the aorta, iliac, femoral, popliteal, and the distal anterior and posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries of the lower extremity images on the right-hand side of the Figure (7, 8) in regards to clinical assessment of PAD. Note that steps and figures in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 are from diabetic models), and that step 5 is from hypertensive models and denote the beginning of the vessel wall cellular remodeling that is associated with both atherosclerosis and hypertension, which associate with vascular arterial stiffening (VAS) and the development and progression of PAD. Further, note that steps 3, 4, and 5 are associated with vascular calcification that is discussed in greater detail in the following section. As can be observed, the development and progression PAD involves the multifactorial interactions and remodeling changes, which culminate in hypertensive changes and excessive atherosclerosis that associate with stiffening of the vascular wall to result in the development and progression of PAD. Importantly, note the two vicious cycles on the road to develop PAD. Once PAD is established it is the formation of progressive vascular narrowing with thrombosis and emboli that result in ischemia and multiple painful clinical stages from intermittent claudication to critical limb ischemia and potential skin ulceration. Notably, most of the clinical symptoms in the in Infra-POP regions result from thrombosis and embolic phenomenon and not atherosclerosis remodeling changes. While these sequential six steps are presented, it is important to note that each of these steps are in a dynamic interaction with one another to result in the multifactorial development and progression of PAD. Notably, vascular ossification and calcification was not included in this six-step process that would occur between step-5 and step-6, it is nevertheless very important in some individuals in regards to the development and progression of PAD and vascular stiffening that is discussed in the following section

4.2. EC, endothelial cell; EC

act/dys, endothelial cell activation and dysfunction; ecGCx, endothelial glycocalyx; EDF, elastin-derived fragments; EDP, elastin-derived products; eHTN, essential hypertension; FEM-POP, femoral-popliteal arteries; HPA, hypothalamus pituitary axis; INFRA-POP, inferior popliteal arteries; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; NFkappaB, nuclear factor kappa B; NO, nitric oxide; OxRS, oxidative redox stress; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 15.

Possible sequence of events leading to the development and progression of peripheral artery disease (PAD). The sequence of events begins with the injury to the endothelium at the top of the figure that was previously presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and is followed sequentially by the six steps and representative images (1-6) with explanation to the left-hand side to arrive at the

magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) images of the aorta, iliac, femoral, popliteal, and the distal anterior and posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries of the lower extremity images on the right-hand side of the Figure (7, 8) in regards to clinical assessment of PAD. Note that steps and figures in

Figure 3 and