1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent and significant public health issue worldwide [

1]. The disease is characterized by persistent structural changes in the airways and alveolar structures. One of the most important components of these structural changes is emphysema. Emphysema is defined as a permanent and abnormal enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by the destruction of their walls [

2]. It represents the most well-defined histopathological component of COPD and is one of the primary mechanisms contributing to airflow limitation.

With the introduction of concepts such as PRISm (Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry) and pre-COPD into the literature, it has become evident that COPD is a heterogeneous disease that cannot be solely defined by the FEV₁/FVC ratio [

3,

4,

5]. In individuals who have not yet developed airflow limitation but exhibit structural lung changes, accurate assessment of symptom burden has gained clinical importance. In this context, the extent of emphysema detected by thoracic CT and its relationship with pulmonary function tests may serve as a valuable guide in both diagnostic and follow-up processes.

It is well established that lung function reaches its peak around the ages of 20 to 25 and begins to decline physiologically after the age of 45 to 50. Therefore, the 20–50 age range represents a critical period where the peak of respiratory function intersects with the onset of early functional decline [

6]. Structural abnormalities identified in this age group may provide insights into the future course of COPD. Furthermore, this period is important for enhancing our understanding of the disease and for the early identification of individuals at risk. In this context, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between radiological findings, symptom severity, and pulmonary function parameters in young adults with radiologically detected emphysema but without spirometric evidence of airflow limitation.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans of patients who presented to our hospital with complaints of dyspnea between April 1, 2022, and June 31, 2024, were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with radiologically detected emphysema but without airflow limitation on pulmonary function tests were included in the study group. Demographic and clinical characteristics of these individuals—such as clinical symptoms, radiological findings, pulmonary function test results, comorbidities, and medications used—were thoroughly evaluated.

2.1. Evaluation of Radiological Images

In this study, the presence of emphysema was assessed using HRCT. The images were obtained with a Philips Ingenuity 128-slice CT scanner. HRCT scans were analyzed by an experienced radiologist according to the Global Radiological Criteria (GRCt) method to evaluate the presence and severity of emphysema.

The assessment of emphysema was conducted based on the following criteria:

2.2. Low Attenuation Areas (LAA)

Lung regions with emphysema were defined as LAA if the density was below −950 Hounsfield Units. The percentage of LAA was calculated in proportion to the total lung volume.

2.3. Types of Emphysema

Centrilobular Emphysema (CLE): Small, irregular low attenuation areas predominantly located in the upper lobes of the lungs.

Panacinar Emphysema (PLE): Diffuse low attenuation areas observed throughout all lung regions.

Paraseptal Emphysema (PSE): Large airspaces localized in the subpleural regions.

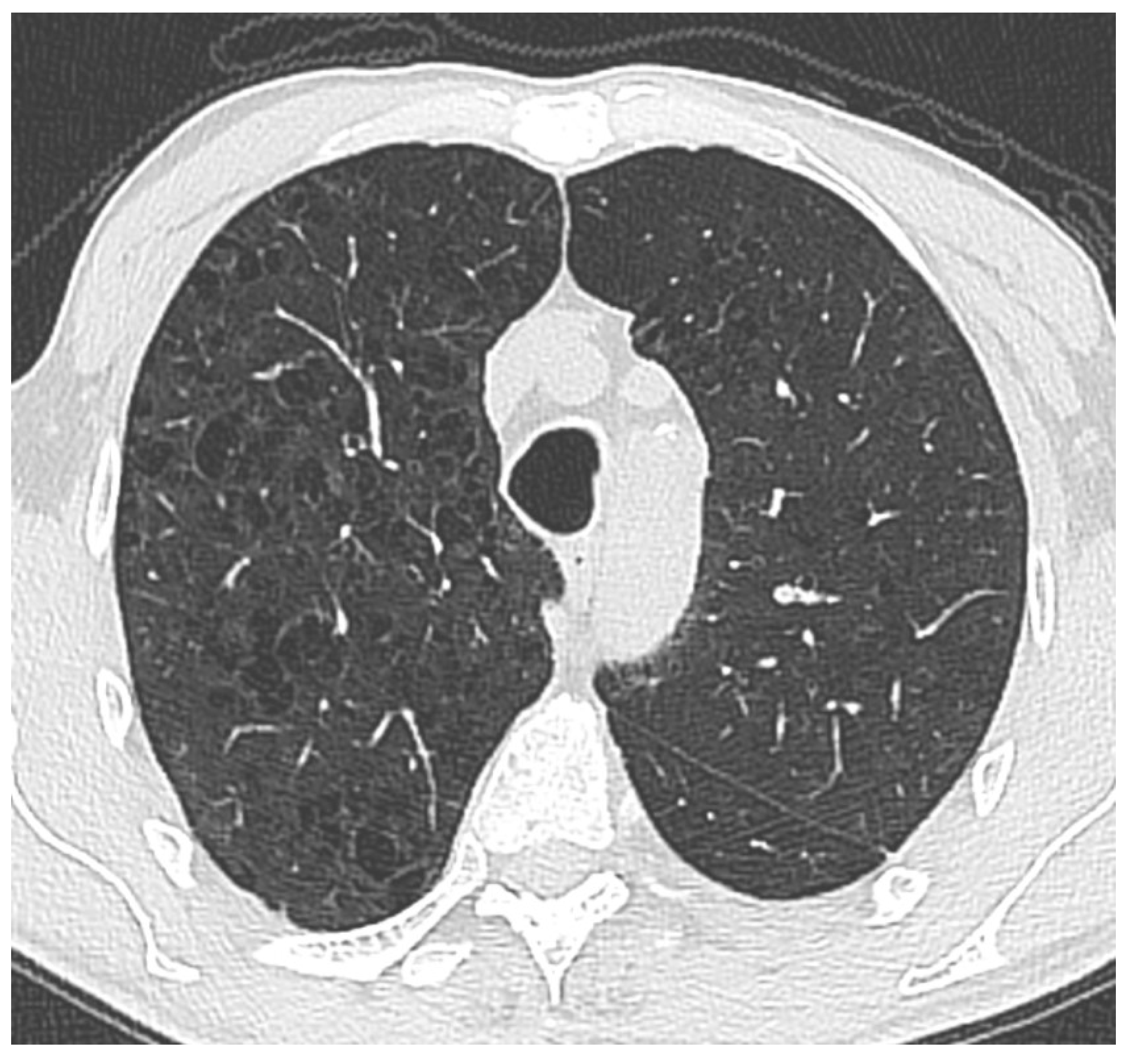

Figure 1.

Thoracic CT image demonstrates widespread, small, irregularly shaped areas of low attenuation predominantly located in the upper lobes of both lungs. These findings are suggestive of centrilobular emphysema. The lesions’ absence of peripheral distribution and their proximity to the central bronchioles are consistent with a typical centrilobular pattern.

Figure 1.

Thoracic CT image demonstrates widespread, small, irregularly shaped areas of low attenuation predominantly located in the upper lobes of both lungs. These findings are suggestive of centrilobular emphysema. The lesions’ absence of peripheral distribution and their proximity to the central bronchioles are consistent with a typical centrilobular pattern.

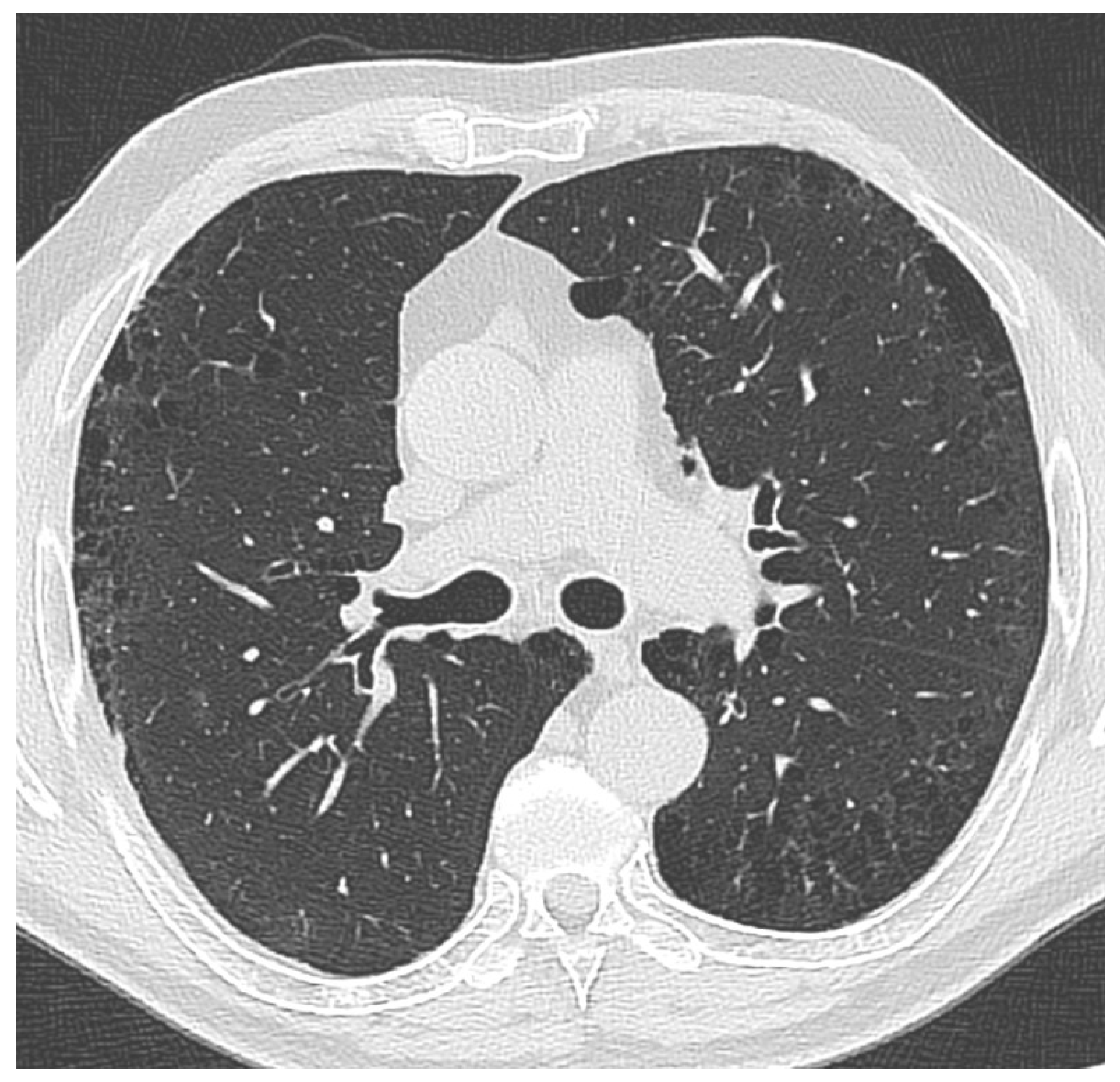

Figure 2.

Thoracic CT image from one of the patients included in the study shows thin-walled, low-attenuation air spaces predominantly located in subpleural regions, particularly in the upper lobes. These findings are consistent with radiological characteristics typical of paraseptal emphysema.

Figure 2.

Thoracic CT image from one of the patients included in the study shows thin-walled, low-attenuation air spaces predominantly located in subpleural regions, particularly in the upper lobes. These findings are consistent with radiological characteristics typical of paraseptal emphysema.

2.4. Severity Grading of Emphysema

Mild: Involvement of less than 5% of the lung parenchyma.

Moderate: Involvement of 5% to 25% of the lung parenchyma.

Severe: Involvement of more than 25% of the lung parenchyma.

2.5. Assessment of Body Mass Index

The body mass index (BMI) of individuals included in the study was calculated by dividing body weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m²). The calculated BMI values were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria as follows: underweight (<18.5 kg/m²), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m²), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m²). This classification was used to evaluate the relationship between BMI, emphysema extent, and symptom severity.

2.6. Assessment of Dyspnea Severity

Dyspnea was assessed using the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, which is designed to evaluate the level of breathlessness experienced by patients during daily activities. The scale is scored from 0 to 4, where a score of 0 indicates dyspnea only during strenuous exercise, and a score of 4 reflects severe symptoms, such as breathlessness that prevents the patient from leaving the house or causes difficulty even while dressing.

2.7. Assessment of Spirometry Test Acceptability

The spirometry test was considered unacceptable if any of the following criteria were present:

Inadequate rapid start of the test,

Incomplete execution of test maneuvers,

Coughing during the procedure,

Premature termination of the test,

Marked fluctuations in effort level,

Transition time from end-inspiration to expiration exceeding 2 seconds,

Time to reach peak expiratory flow from total lung capacity exceeding 1.5 seconds,

Inability to maintain sufficient expiratory effort or to achieve an end-expiratory plateau.

2.8. Patient Selection

The study included patients aged between 20 and 50 years who presented to the pulmonology outpatient clinic of our hospital with complaints of dyspnea and underwent thoracic CT imaging based on clinical indications. This age range was selected because it represents the period during which lung function physiologically reaches its peak and subsequently begins to decline, making it suitable for evaluating early structural changes.

Patients were excluded from the study if other major pathologies that could contribute to dyspnea—such as pulmonary embolism, pleural effusion, bronchiectasis, pulmonary malignancies, interstitial lung diseases, heart failure, or severe anemia—were identified either radiologically or clinically. This exclusion aimed to allow a more isolated assessment of the relationship between emphysema and symptoms.

2.9. Inclusion Criteria

Patients aged between 20 and 50 years

Patients diagnosed with emphysema by a radiologist based on HRCT findings

Patients with acceptable spirometry test performance

Patients without evidence of obstruction on spirometry

2.10. Exclusion Criteria

Asymptomatic patients

Patients with unavailable spirometry data

Patients with unacceptable spirometry performance

Patients with evidence of obstruction on spirometry

Patients with radiological findings suggestive of interstitial lung disease

Patients diagnosed with lung malignancy or those with suspicious masses on radiological evaluation

Presence of any parenchymal lung disease

Patients under 20 years of age

Patients over 50 years of age

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our hospital with decision number 159, dated November 13, 2024. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For continuous variables that did not show normal distribution, median values along with interquartile ranges (IQR: 25th–75th percentile) were reported. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages (%). Clinical, demographic, and pulmonary function test parameters were compared among emphysema severity groups (<5%, 5–25%, >25%) using the Kruskal-Wallis test; for variables with statistically significant differences, pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Correlations between emphysema severity and pulmonary function test parameters (FEV₁, FVC, FEV₁/FVC) as well as the mMRC score were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation analysis. Additionally, PRISm and pre-COPD subgroups were compared in terms of clinical and symptomatic features. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

3. Results

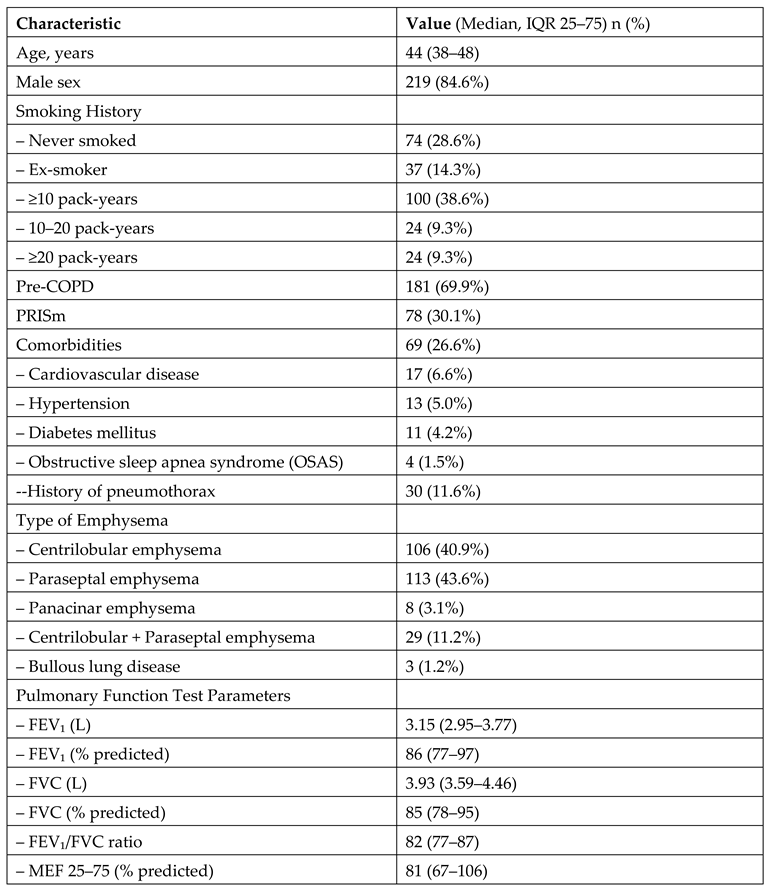

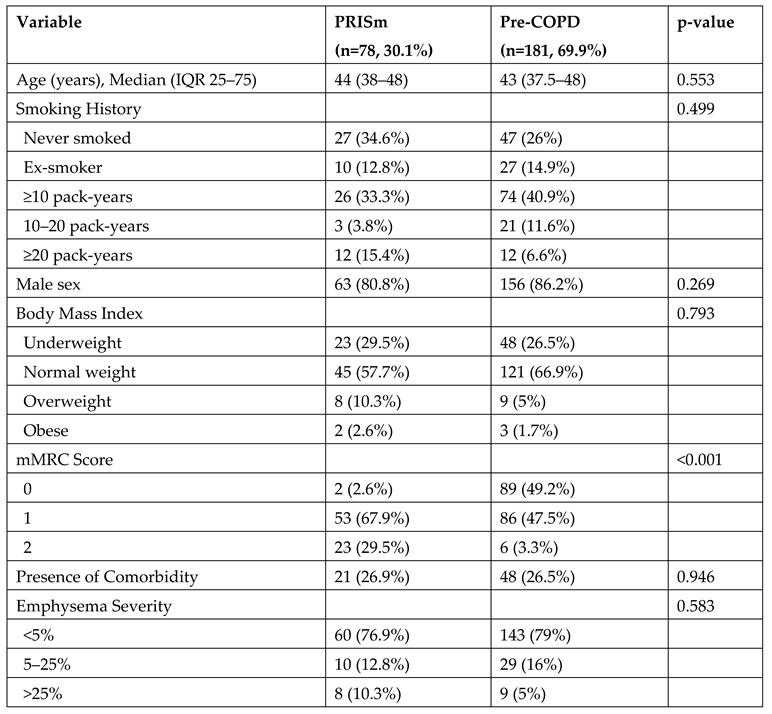

A total of 259 patients who met the eligibility criteria were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 44 years, and the majority were male (84.6%). A substantial proportion of patients had a history of smoking; 38.6% had a smoking history of ≥10 pack-years. Among the participants, 69.9% were classified in the pre-COPD category, while 30.1% belonged to the PRISm group. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical, Demographic, Radiological, and Functional Characteristics of the Patients Included in the Study (N = 259).

Table 1.

Clinical, Demographic, Radiological, and Functional Characteristics of the Patients Included in the Study (N = 259).

Among the patients included in the study, paraseptal emphysema was the most frequently observed type, identified in 43.6% of cases. Regarding the extent of emphysema, the majority of patients (78.4%) had less than 5% involvement of the lung parenchyma. Evaluation of pulmonary function tests revealed a median FEV₁ of 3.15 L and a percent predicted FEV₁ of 86%. The results are presented in

Table 1.

Among the 30 patients with a history of pneumothorax, paraseptal emphysema was the most frequently observed type (n=17, 56.7%), followed by centrilobular emphysema (n=10, 33.3%).

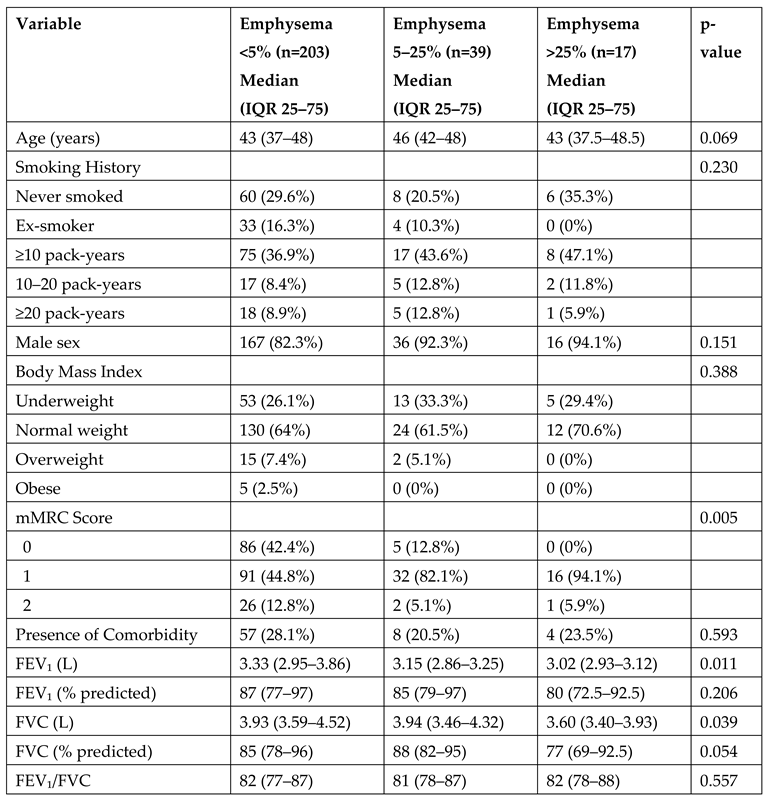

Patients were categorized into three groups based on the extent of emphysema observed on imaging: <5% (n=203), 5–25% (n=39), and >25% (n=17). In the subgroup analysis according to emphysema severity, there were no significant differences in age, smoking history, sex, or BMI. However, the level of dyspnea increased significantly with greater emphysema extent (p=0.005). Regarding pulmonary function, both FEV₁ (p=0.011) and FVC (p=0.039) values were significantly lower in patients with more extensive emphysema. The FEV₁/FVC ratio did not differ significantly between the groups (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup Comparisons According to Emphysema Severity.

Table 2.

Subgroup Comparisons According to Emphysema Severity.

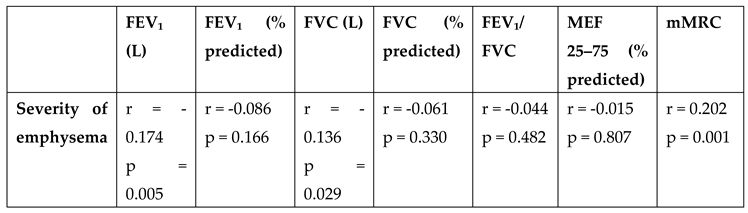

In the correlation analysis between emphysema severity and pulmonary function tests, a weak but statistically significant negative correlation was found between emphysema severity and FEV₁ (L) (r = -0.174, p = 0.005) as well as FVC (L) (r = -0.136, p = 0.029). No significant associations were observed between emphysema severity and other spirometric parameters. Additionally, a significant relationship was identified between emphysema severity and dyspnea level; a weak positive correlation was found between the mMRC score and emphysema severity (r = 0.202, p = 0.001) (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis Between Emphysema Severity and Pulmonary Function Test Results in Study Participants.

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis Between Emphysema Severity and Pulmonary Function Test Results in Study Participants.

Patients were divided into two groups based on spirometry results: PRISm and pre-COPD. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, smoking history, body mass index, or presence of comorbidities. However, when dyspnea severity was assessed using mMRC scores, significantly higher levels of dyspnea were reported in the PRISm group (p<0.001). While 29.5% of patients in the PRISm group had an mMRC score of 2, this proportion was only 3.3% in the pre-COPD group (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between PRISm and Pre-COPD Groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between PRISm and Pre-COPD Groups.

4. Discussion

In this study, the clinical and functional implications of radiologically detected emphysema were investigated in individuals aged 20 to 50 years who presented with dyspnea but did not exhibit airflow limitation on pulmonary function tests. The findings suggest that the presence of emphysema in the pre-obstructive phase may have a significant impact on symptom burden and pulmonary capacity. Notably, the significant association between dyspnea severity and emphysema extent, along with the observed decrease in FEV₁ with increasing emphysema severity, highlights the clinical relevance of these structural changes. Furthermore, the presence of more severe dyspnea in patients with PRISm (Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry) supports the importance of recognizing this phenotype. The fact that paraseptal emphysema was the most frequently observed subtype on imaging—and the predominant form among patients with a history of pneumothorax—suggests that this emphysema type may be more prominent in younger individuals.

In our study, a notable frequency of systemic comorbidities was observed among younger individuals who had not yet developed airflow limitation. At least one comorbidity was identified in 26.6% of the patients, with the most common accompanying conditions being cardiovascular diseases (6.6%), hypertension (5%), and diabetes mellitus. The literature also indicates that the presence of emphysema is not limited to respiratory effects alone but may be associated with metabolic and systemic disorders such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes [

7,

8]. These findings suggest that comorbidities may also be present in early-stage cases without airflow limitation. Therefore, it is important to monitor patients in both the PRISm and pre-COPD groups not only for respiratory symptoms but also for systemic risks. A multidisciplinary approach may be valuable in preventing potential future complications in this population.

The PRISm phenotype has been associated with reduced pulmonary function, increased symptom burden, and adverse long-term clinical outcomes [

9]. In the literature, the prevalence of this phenotype varies between 7% and 20% depending on the population studied. It has been frequently linked to male sex, smoking, and metabolic comorbidities [

10]. In our study, the prevalence of PRISm was found to be relatively high at 30.1%. This may be attributed to the fact that the study sample consisted solely of symptomatic individuals presenting with dyspnea. The prevalence of comorbidities and male sex distribution were similar between the PRISm and pre-COPD groups. However, the proportion of patients with a smoking history of ≥20 pack-years was higher in the PRISm group compared to the pre-COPD group. This finding suggests that the PRISm phenotype may reflect a clinical profile more susceptible to smoking-related structural lung damage.

Patients in the PRISm group have been shown in the literature to exhibit symptom levels comparable to, or even exceeding, those observed in individuals with COPD [

11]. In a study by Evans et al., 57% of PRISm patients had an mMRC score of ≥2, indicating a notably high symptom burden [

12]. Similarly, in our study, dyspnea levels were significantly higher in the PRISm group. The proportion of patients with an mMRC score of 2 was 29.5% in the PRISm group, compared to only 3.3% in the pre-COPD group. This finding suggests that the PRISm phenotype should be differentiated not only by spirometric classification but also by symptom severity. Monitoring this level of symptom burden -even in younger individuals- is critically important for early intervention and preserving quality of life.

Radiological assessment of emphysema extent is gaining increasing importance in predicting the clinical course and functional impact of the disease. In our study, weak but statistically significant negative correlations were found between emphysema severity and key spirometric parameters such as FEV₁ and FVC. These findings suggest that the extent of emphysema identified by CT may affect pulmonary function even in the absence of airflow limitation. In a study conducted by Senel et al. in patients with COPD, emphysema severity was significantly associated with FEV₁ levels; however, no significant relationship was found with mMRC dyspnea scores [

13]. In contrast, our study identified a significant positive correlation between mMRC scores and emphysema severity. This reflects the impact of structural lung damage in symptomatic pre-COPD or PRISm phenotypes. Similarly, a large cohort study by Kahnert et al. demonstrated significant associations between emphysema scores and parameters such as FEV₁/FVC [

14]. Collectively, these findings indicate that emphysema can influence both respiratory symptoms and functional capacity not only in advanced-stage COPD but also during the pre-obstructive phase of the disease.

Additionally, in terms of emphysema subtypes, one of the noteworthy findings of our study is that paraseptal emphysema was the most frequently observed subtype in the young adult population. In the literature, paraseptal emphysema has commonly been associated with spontaneous pneumothorax and is more likely to be seen in young, thin males due to its subpleural distribution [

15]. In this context, the finding that more than half (56.7%) of the patients with a history of pneumothorax in our study had paraseptal emphysema provides clinical support for this association. This suggests that paraseptal emphysema may represent a silent yet potentially complication-prone pathology in young adults.

This study has several limitations. First, the extent and severity of emphysema were assessed qualitatively by a radiology specialist based on HRCT images. The absence of quantitative CT analysis limited the ability to measure structural changes with greater precision and objectivity. Additionally, due to the retrospective design of the study, follow-up data and longitudinal clinical outcomes of the patients were not available. Therefore, it was not possible to draw conclusions regarding the long-term prognostic impact of emphysema or the risk of COPD development in these individuals. No significant difference was found in the extent of emphysema between the PRISm and pre-COPD groups, which may be related to the young age of the study population and the fact that emphysema was limited to <5% in the majority of patients. The single-center design of the study is another factor that may limit the generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, our study contributes meaningfully to the literature as one of the few investigations exploring the clinical implications of radiologically detected emphysema in a young adult population.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that radiologically detected emphysema in young adults without airflow limitation may have clinically significant effects. The observed associations between emphysema extent, reduced FEV₁ levels, and increased dyspnea severity suggest that structural lung changes can impact symptoms and functional capacity even at an early stage. Our findings highlight the importance of not overlooking emphysema identified before the development of airflow limitation and underscore the need for close monitoring of this patient population. To enhance the generalizability of these results and better guide clinical management, multicenter prospective studies are warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., H.E. and M.Y.; methodology, T.Ö., D.Ç. and D.K.; investigation, M.K. and T.D.; resources, Ö.F.T. and T.Y.; data curation, S.K.K., T.D. and T.Y.; formal analysis, Ö.F.T., T.D., and T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., M.Y. and D.Ç.; writing—review and editing, H.E. and T.Ö. ; supervision, M.A. and Ö.F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Ankara Ataturk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital (Decision No: 159, dated 13 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Wachami N; Guennouni M; Iderdar Y; Boumendil K; Arraji M; Mourajid Y; Bouchachi FZ; Barkaoui M; Louerdi ML; Hilali A; et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024, Cilt 25;24(1):297. [CrossRef]

- Petrache I. Unraveling the Distal Lung Destruction in Emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023, Cilt 15;208(4):357-358. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan P. GOLD report: 2022 update. Lancet Respir Med. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Han MK; Agusti A; Celli BR; Criner GJ; Halpin DMG; Roche N; Papi A; Stockley RA; Wedzicha J; Vogelmeier CF. From GOLD 0 to Pre-COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021, Cilt 15;203(4):414-423. [CrossRef]

- Adibi A; Sadatsafavi M. Looking at the COPD spectrum through "PRISm". Eur Respir J. 2020, Cilt 2;55(1):1902217. [CrossRef]

- Melén E; Faner R; Allinson JP; Bui D; Bush A; Custovic A; Garcia-Aymerich J; Guerra S; Breyer-Kohansal R; Hallberg J; et al. Lung-function trajectories: relevance and implementation in clinical practice. Lancet. 2024, Cilt 13;403(10435):1494-1503. [CrossRef]

- Cobb, K. Kenyon, J. Lu, J. Krieger, B. Perelas, A. Nana-Sinkam, P. Kim, Y. Rodriguez-Miguelez, P. COPD is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk independent of phenotype. Respirology. 2024, Cilt 29(12):1047-1057. [CrossRef]

- Ter Haar EAMD; Slebos DJ; Klooster K; Pouwels SD; Hartman JE. Comorbidities reduce survival and quality of life in COPD with severe lung hyperinflation. ERJ Open Res. 2024, Cilt 18;10(6):00268-2024. [CrossRef]

- Wan ES; Balte P; Schwartz JE; Bhatt SP; Cassano PA; Couper D; Daviglus ML; Dransfield MT; Gharib SA; Jacobs DR Jr; et al. Association Between Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry and Clinical Outcomes in US Adults. JAMA. 2021, Cilt 14;326(22):2287-2298. [CrossRef]

- Higbee DH; Granell R; Davey Smith G; Dodd JW. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: a UK Biobank cohort analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, Cilt 10(2):149-157. [CrossRef]

- Agustí A; Hughes R; Rapsomaki E; Make B; Del Olmo R; Papi A; Price D; Benton L; Franzen S; Vestbo J; et al. The many faces of COPD in real life: a longitudinal analysis of the NOVELTY cohort. ERJ Open Res. 2024, Cilt 12;10(1):00895-2023. [CrossRef]

- Evans A; Tarabichi Y; Pace WD; Make B; Bushell N; Carter V; Chang KL; Fox C; Han MK; Kaplan A; et al. Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry in US Primary Care Patients Diagnosed with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Pragmat Obs Res. 2024, Cilt 13;15:221-232. [CrossRef]

- Yumrukuz Senel M; Akcali SD; Dilli A; Kurt B. Correlation of the Radiological Emphysema Score of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients with Clinic Parameters. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2021, Cilt 31(5):506-510. [CrossRef]

- Kahnert K; Jobst B; Biertz F; Biederer J; Watz H; Huber RM; Behr J; Grenier PA; Alter P; Vogelmeier CF; et al. Relationship of spirometric, body plethysmographic, and diffusing capacity parameters to emphysema scores derived from CT scans. Chron Respir Dis. 2019, Cilt 16:1479972318775423. [CrossRef]

- Diaz AA. Paraseptal Emphysema: From the Periphery of the Lobule to the Center of the Stage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020, Cilt 15;202(6):783-784. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).