1. Introduction

The use of thyroid US has substantially risen over the past two decades, reflecting a global trend. A study combining data from the Medicare and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) databases revealed an annual increase of 21% in US use over a decade (2002-2013) [

1]. Similarly, an analysis within the Veterans Affairs healthcare system demonstrated a nearly five-fold increase in the rate of US use, from 125 per 100,000 individuals in 2001 to 572 per 100,000 in 2012 [

2]. The widespread adoption of US has reshaped the approach to managing thyroid conditions. Concurrently, the incidence of thyroid cancer has risen, with a correlation to the frequency of US procedures performed [

3]. Studies from Korea also indicate that the increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses can be attributed to extensive screening and overdiagnosis [

4]. Regional variations in thyroid cancer rates, including those observed in Belgium, further emphasize the role of imaging and management practices in this trend [

5].

Thyroid ultrasound, being a non-invasive and radiation-free imaging technique, provides valuable information about thyroid size, morphology, and structure, particularly in managing thyroid nodules and cancers [

6]. However, inappropriate use of this technology can lead to adverse consequences. It is estimated that between 10-50% of US exams are conducted outside recommended clinical guidelines [

7]. Patients who undergo unnecessary US exams, particularly those in which thyroid nodules are incidentally discovered, may face undue anxiety, unnecessary diagnostic procedures, and potentially overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer. While the exact drivers behind inappropriate US use remain unclear, likely, a combination of clinician, patient, and healthcare system factors play a role [

8]. This review aims to explore the patterns in US usage, factors driving its misuse, and potential strategies to mitigate overuse, which contributes to escalating healthcare costs and patient risks.

2. Thyroid Ultrasound: Fundamental Concepts

Thyroid ultrasound is a critical imaging modality for diagnosing thyroid disorders. It offers a real-time, noninvasive examination of the thyroid gland and surrounding tissues. The technology allows for the precise assessment of thyroid size, shape, composition, and blood flow and is essential for detecting abnormalities such as nodules and diffuse thyroid diseases.

2.1. Ultrasound Probes

At the core of it is the ultrasound probe (transducer), which emits high-frequency sound waves and captures the returning echoes from tissues, translating these into images. The choice of transducer frequency, ranging typically from 5 MHz to 15 MHz, depends on the patient’s body type and the depth of the thyroid gland. Higher-frequency probes (10-15 MHz) provide better resolution for superficial structures, while lower frequencies (5-7.5 MHz) offer greater penetration for deeper tissues. Linear array transducers are commonly used for imaging the thyroid due to their ability to provide high-resolution images of the gland's superficial regions [

9]

2.2. Color Doppler Ultrasound

Color Doppler ultrasound enhances conventional imaging by adding color-coded blood flow data within the thyroid. This technique helps identify hypervascular nodules, using red to show blood moving toward the transducer and blue for blood moving away, allowing assessment of flow direction and speed in vessels [

10] However, it has limitations in detecting artifacts and experiences challenges related to depth.

2.3. Elastography and Shear Wave Elastography

Elastography measures tissue stiffness, thus helping distinguish between benign and malignant nodules. Tissue stiffness is quantified in kilopascals (kPa), with stiffer tissues often associated with malignancy. There are two main types of elastography: strain elastography, which offers a qualitative measure of stiffness based on tissue deformation, and shear wave elastography (SWE), which provides a more accurate, quantitative assessment. SWE is increasingly favored in daily practice due to its reproducibility and precision [

11]

2.4. Thyroid Ultrasound Examination Technique

The patient is positioned supine with the extended neck, facilitating optimal thyroid gland visualization. The examination proceeds by moving the transducer across the thyroid lobes and isthmus, evaluating both anterior and posterior aspects and lateral and medial margins. In addition to assessing nodules, the exam should evaluate surrounding structures such as lymph nodes and the parathyroid glands. Doppler technology can assess blood flow, while elastography may be applied to evaluate concerning thyroid nodules [

12]. Ultrasound examination of the thyroid plays a crucial role in identifying, monitoring, and treating various thyroid conditions, such as nodules, inflammatory disorders, and other thyroid pathologies. It should be noted, however, that the diagnostic accuracy depends on the operator’s expertise, and errors in technique or interpretation may result in inaccurate diagnoses. Thus, a comprehensive approach that combines ultrasound findings with clinical evaluation is crucial to ensuring the best patient outcomes.

3. Thyroid Ultrasound in Thyroid Dysfunctions

3.1. Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism refers to an excessive level of thyroid hormones in tissues, resulting from increased hormone synthesis, excessive release of preformed thyroid hormones, or an exogenous or endogenous extrathyroidal source. The most prevalent causes of increased thyroid hormone production are Graves’ disease, followed by toxic multinodular goiter and toxic adenoma. In contrast, the most common cause of passive hormone release is painless (silent) thyroiditis, although its clinical presentation overlaps with other causes. Treatment of hyperthyroidism due to overproduction of thyroid hormones can include antithyroid medications (e.g., methimazole, propylthiouracil), radioiodine therapy, or thyroidectomy. Treatment selection depends on the underlying cause, potential contraindications, disease severity, and patient preferences [

13]. Before initiating treatment, a comprehensive assessment is crucial to identify the precise etiology of hyperthyroidism. While a thorough clinical history and examination can often establish the cause, distinguishing Graves’ disease from other forms of thyrotoxicosis may pose challenges, especially in the absence of pathognomonic signs such as thyroid-associated orbitopathy or palpable thyroid nodules [

14,

15]. According to the American Thyroid Association guidelines, diagnosis can be confirmed with clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging. While not always conclusive, ultrasound findings can significantly aid in differential diagnosis [

14]. Radionuclide scanning, utilizing either

99mTc-pertechnetate or

123I, remains the standard diagnostic approach for differentiating destructive thyrotoxicosis from hyperthyroidism and distinguishing between diffuse and focal thyroid hyperactivity [

16,

17,

18].

3.2. Ultrasound Findings in Thyrotoxicosis

Ultrasound patterns observed in patients with thyrotoxicosis can vary based on the underlying condition, such as Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, or thyroiditis. These patterns are essential for differential diagnosis and include:

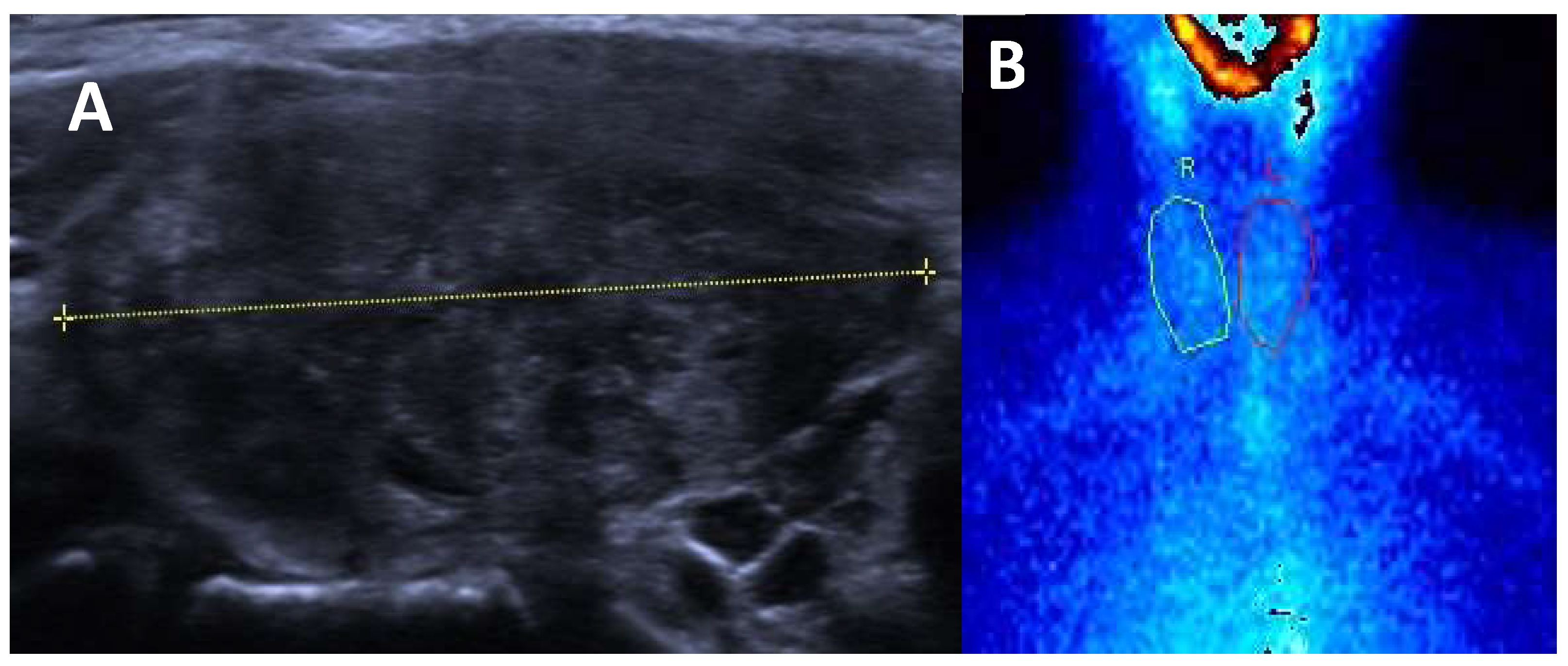

3.2.1. Graves’ Disease

Diffuse Enlargement: the thyroid is typically symmetrically enlarged.

Increased Vascularity: Doppler ultrasound often reveals increased blood flow within the thyroid, corresponding to heightened metabolic activity.

Hypoechoic Parenchyma: the thyroid tissue may appear hypoechoic relative to normal tissue, reflecting inflammatory changes.

Heterogeneous echogenicity: a mild to marked heterogeneity in echotexture may be seen, indicative of autoimmune processes and inflammatory changes within the thyroid gland.

An example of Graves’ Diseases ultrasound appearance is illustrated in the

Figure 1.

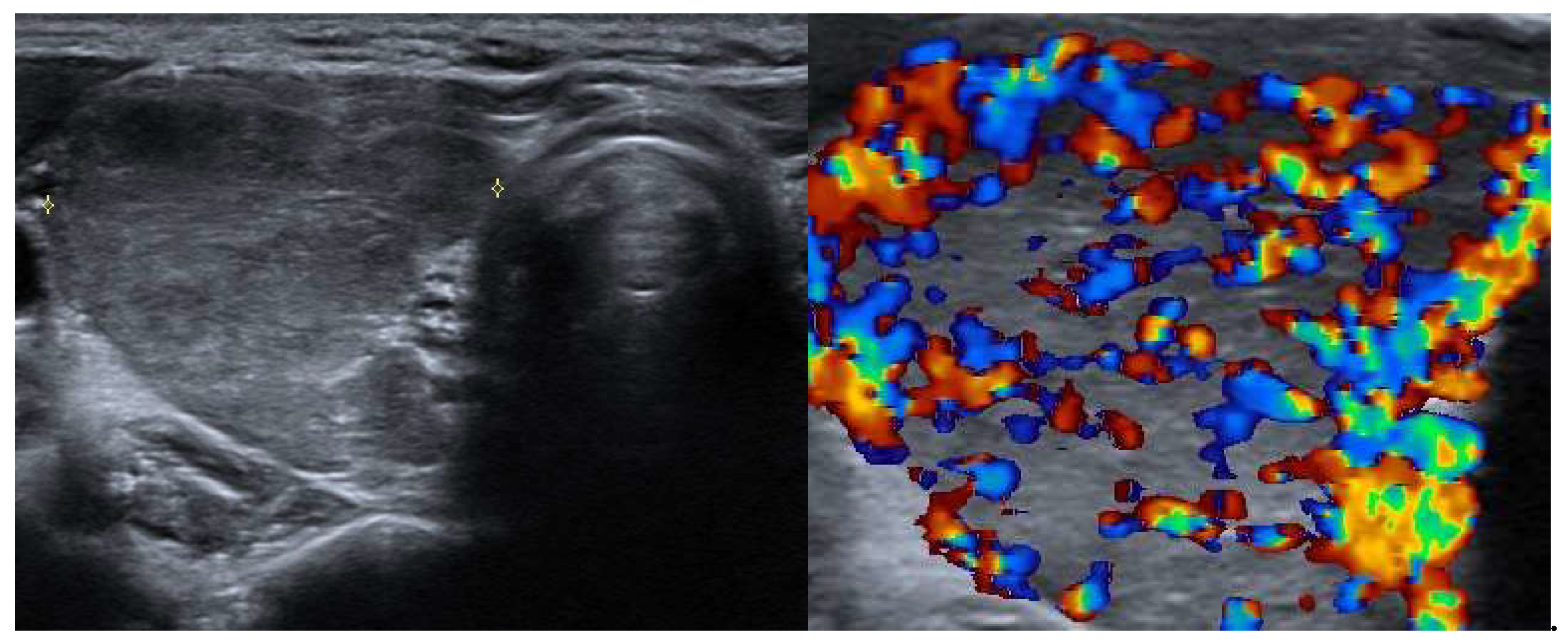

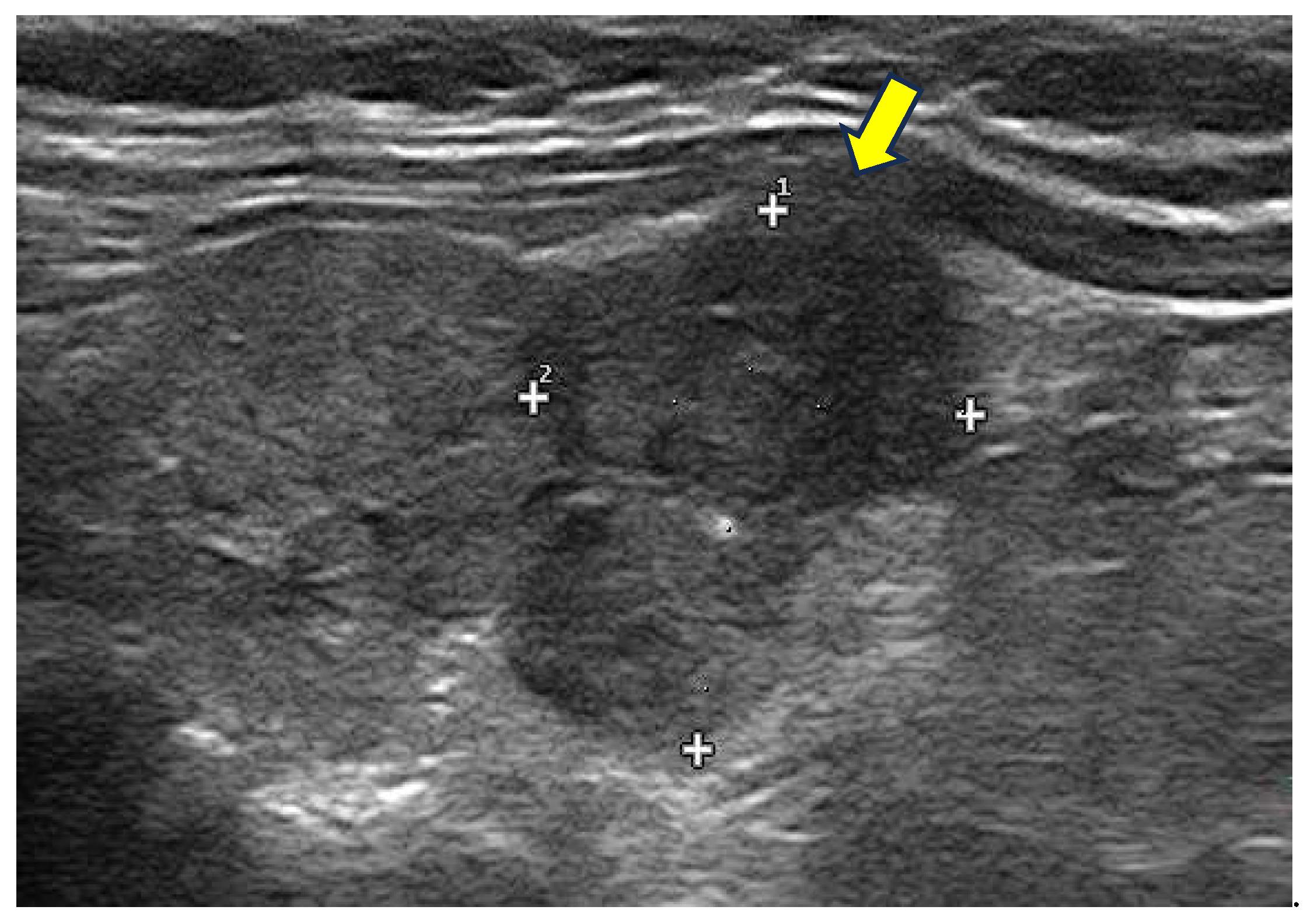

3.2.2. Unifocal Thyroid Autonomy (Solitary Toxic Adenoma)

Hypoechoic Nodule: a solitary toxic adenoma typically appears as a well-defined, hypoechoic nodule.

Increased Vascularity: Doppler ultrasound may reveal heightened blood flow, peripherally and within the nodule.

Compression of Surrounding Tissue: larger adenomas may exert pressure on adjacent thyroid tissue.

Thypical appearance of an autonomously functioning thyroid nodules at ultrasound and scintigraphy is showed in the

Figure 2.

3.2.3. Multifocal Thyroid Autonomy (Toxic Multinodular Goiter)

Multiple Nodules: Multiple nodules are characteristic of toxic multinodular goiter.

Heterogeneous Echogenicity: The thyroid often exhibits an irregular echotexture due to multiple nodules of varying sizes, which may compress the surrounding tissue.

Vascularity: Doppler ultrasound typically demonstrates increased vascularity within the thyroid gland and individual nodules, particularly in areas of active thyroid tissue.

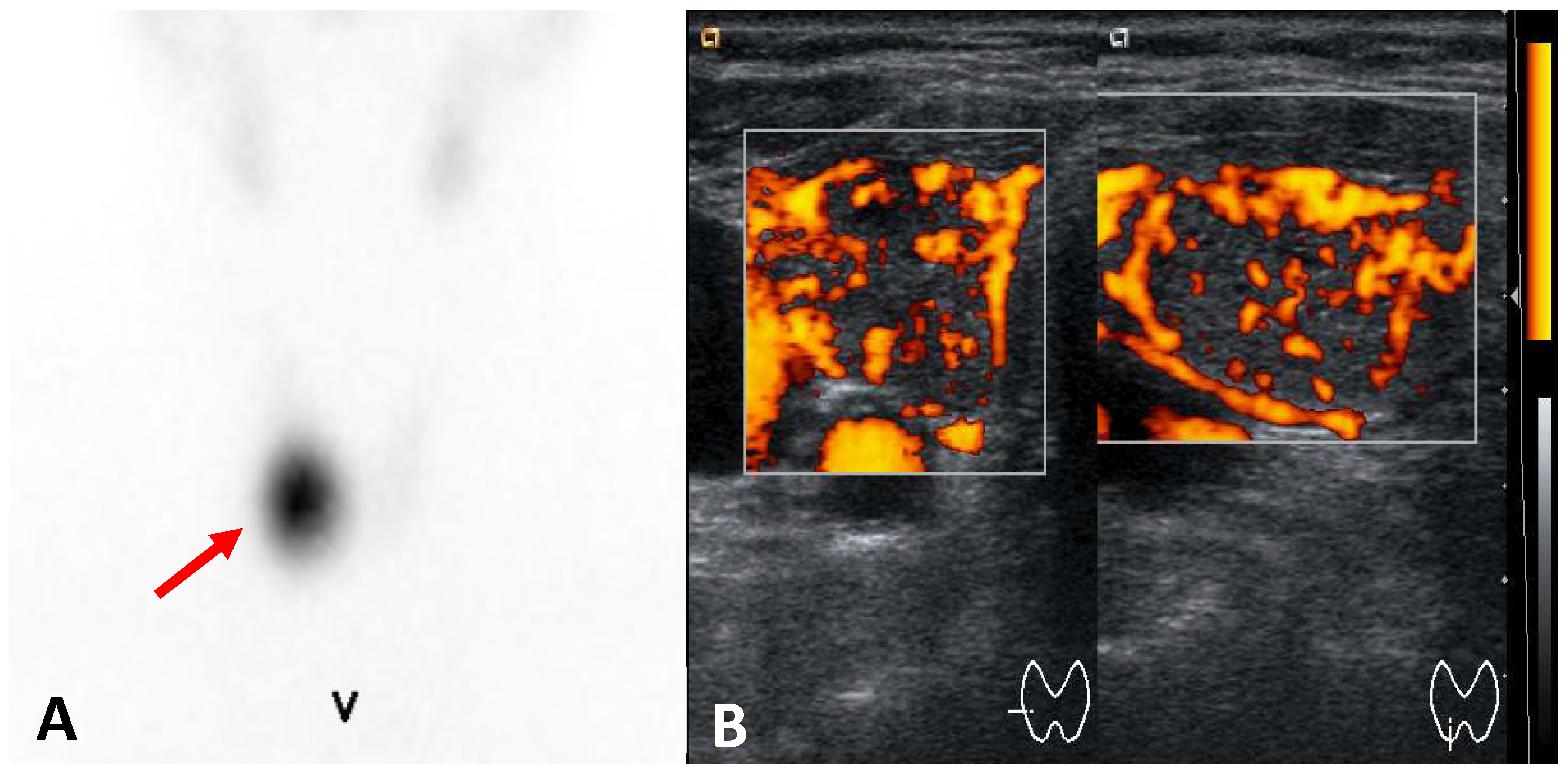

3.2.4. Destructive Thyroiditis

Enlarged gland: the thyroid may appear enlarged but with a texture distinct from that seen in Graves’ disease or toxic multinodular goiter. Pseudonodules may be present.

Hypoechoic and heterogeneous texture: the thyroid tissue may display a hypoechoic and heterogeneous pattern due to inflammation and necrosis, particularly in subacute thyroiditis (

Figure 2).

Reduced vascularity: unlike Graves’ disease, thyroiditis often shows diminished or absent vascularity on Doppler ultrasound due to reduced blood flow in the inflamed tissue.

Figure 3.

Subacute thyroiditis A. Ultrasound: enlarged thyroid markedly hypoechoic and hererogeneous, B. 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy: absent thyroid activity.

Figure 3.

Subacute thyroiditis A. Ultrasound: enlarged thyroid markedly hypoechoic and hererogeneous, B. 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy: absent thyroid activity.

Although ultrasound findings in thyrotoxicosis are not pathognomonic, they can help narrow differential diagnoses. The key features to assess include vascularity and gland texture. Colour Doppler ultrasound, in particular, is a valuable tool for distinguishing Graves’ disease from destructive thyrotoxicosis. However, the test remains highly operator-dependent and is subject to considerable variability [

19].

3.3. Clinical guidelines

Almost all available guidelines suggest a selective use of diagnostic tools to define the cause of thyrotoxicosis. However, significant divergences exist concerning the use of US that is recommended in all patients together with thyrotropin receptor antibodies (TRAb) by ETA guidelines but only in patients with unclear diagnosis and alternatively to TRAb or scintigraphy by ATA. Divergent recommendations can be found in the literature and clinical guidelines. Finally, NICE guidelines suggest TRAb in the first line followed by thyroid scintigraphy in TRAb-negative patients while ultrasound is suggested in case of clinically detectable nodule(s) [

20] (

Table 1)

Measurement of TRAb is a highly effective and rapid diagnostic tool for Graves’ disease. Newer TRAb binding immunoassays offer excellent sensitivity (>97%) and specificity (98%-99%) [

22]. Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI) serve as the hallmark of Graves’ hyperthyroidism and its extrathyroidal manifestations [

23]. While previous methods of assessing TSI were complex and expensive, recent advances have simplified the process, enhancing their inclusion in diagnostic algorithms [

24]. When two thyrotropin-receptor antibody assays (TRAb and TSI), thyroid scintigraphy, and ultrasonography were performed and compared in 124 patients with newly diagnosed and untreated thyrotoxicosis (final diagnosis: GD, n= 86; non-GD hyperthyroidism, n = 38), thyroid scintigraphy remained the most accurate method to differentiate causes of thyrotoxicosis. However, TRAb assays may be alternatively adopted in this setting, limiting the use of thyroid scintigraphy to TRAb-negative patients. Thyroid US was less accurate than TRAb/TSI and thyroid scintigraphy, but the ‘thyroid inferno’ pattern provides a high positive predictive value for GD, respectively [

25]. All in all, it should be concluded that a careful clinical history and clinical examination are pivotal in evaluating patients with biochemically confirmed hyperthyroidism and may solve most cases without additional tests, reducing patients’ discomfort and anxiety as well as attached costs. Biochemical markers (i.e., TRAb) or imaging (US, thyroid scintigraphy, and radioiodine uptake test) should be selectively employed in cases with an unclear clinical diagnosis. Measurement of TRAb should be adopted in the first line as a positive result confirms a GD diagnosis (the most frequent cause of hyperthyroidism) with a pretty absolute accuracy. In other cases, thyroid scintigraphy offers a functional differential diagnosis (i.e., low uptake as in destructive thyroiditis; high uni- or multifocal hyperactivity as in autonomously functioning nodules) and informs adequate treatments. Conversely, the US cannot provide etiological or functional information and should be limited to patients with coexisting non-autonomous nodules or large goiters to provide anatomical information.

3.4. Hypothyroidism

In patients with suspected hypothyroidism, TSH measurement should be the initial diagnostic test. A normal TSH level generally rules out primary hypothyroidism. However, if clinical symptoms strongly suggest hypothyroidism despite nonelevated TSH, a free thyroxine level should be measured to evaluate for central hypothyroidism (caused by pituitary or hypothalamic dysfunction), which is much less common but should not be overlooked. Thyroid autoantibodies (antithyroid peroxidase, TPOAb, and antithyroglobulin antibodies, TgAb) are positive in 95% and 60% of patients with autoimmune thyroiditis, respectively. Testing for TPOAb provides adequate sensitivity and specificity to serve as the sole confirmatory test required for diagnosing autoimmune thyroiditis [

26]. Importantly, up to 10% of the general population may be positive for TPOAb without having thyroid dysfunction, but treatment is not indicated in these individuals. On the other hand, it signals an increased risk of becoming hypothyroid over time, and annual TSH testing is suggested in this case [

27]. Basically, a diagnosis of hypothyroidism itself is not an indication for thyroid imaging. Thyroid ultrasonography is only indicated to evaluate suspicious structural thyroid abnormalities (i.e., palpable thyroid nodules) [

28,

29,

30]. Despite consistent literature and guidelines suggesting a restricted use of US in patients with thyroid dysfunctions, current clinical practice diverges significantly from recommendations. Edwards and colleagues reviewed and meta-analyzed seven studies (total enrolled patients = 1573) and established an overall frequency of inappropriate US use of 46% (95% CI 15-82%; n = 388 patients) and 34% (95% CI 16-57%; n = 190 patients) in studies using guideline-based definitions. The pooled frequency of inappropriate ultrasound was 17% (95% CI 7-37%; n = 191 patients) in patients with thyroid dysfunction (either hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis) and 11% (95% CI 5-22%; n = 124) in patients with nonspecific symptoms without a palpable mass [

7]. Acosta and colleagues reported that 10% to 50% of US orders are outside clinical practice recommendations. The drivers of inappropriate use of US are not yet completely defined, but a combination of clinician, patient, and healthcare system factors likely contribute to this problem [

31]. Most data on the (in)appropriate use of US comes from the United States, Canada, and the UK, while European data are unavailable. However, considering more permissive guidelines and the wide use of US in endocrinologists’ offices, the rate of inappropriately requested/performed procedures is likely higher in European countries. Notably, different clinical societies recently diffused a firm warning against the systematic use of US in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests (i.e., over- and under-active thyroid function). They stressed that it should not be required on a routine basis in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests but should be restricted to patients with large goiter or a lumpy thyroid at clinical examination. Specifically, they suggested that excessive reliance on US often reveals clinically insignificant nodules, potentially shifting the focus of medical evaluation away from the underlying thyroid dysfunction to these incidental findings. Finally, they suggest using thyroid scintigraphy to assess the etiology of the thyrotoxicosis when a differential diagnosis is needed, instead of US [

32,

33].

4. Thyroid nodules

Thyroid nodules are lesions inside the thyroid gland that are radiologically different from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma. They are common, and their prevalence in the general population varies from 2 to 65% depending on diagnostic techniques [

34]. Moreover, nodules are more common in countries with iodine-deficient populations [

35]. Although the introduction of iodized salt eliminated iodine deficiency in many regions across the globe, the real prevalence of thyroid nodules is still largely unknown [

36] They are discovered either clinically (i.e. self-palpation by a patient, by a clinician) or, much more frequently, incidentally during a radiologic procedure such as US, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography ([

18F]FDG PET/CT) for other indications. Indeed, US is still largely performed outside guidelines’ recommendations and without clear indications (as an example, see sections on thyroid dysfunctions), greatly increasing the number of detected nodules. Overall, the diagnosis of thyroid nodules includes a fraction that harbored malignancy (2-5%), may cause compressive symptoms (5%), or are functionally hyperactive (<5%) [

37]. Following the trend of increasing detection of thyroid nodules, Chen and colleagues reported a large increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer occurred between 1975 (5.0 cases per 100 000 people) and 2009 (14.6 cases per 100 000 people), which was followed by a plateau until 2019 (14.1 cases per 100 000 people). This plateau occurred in almost all age groups, starting from age 25 years, and was most marked during middle age (around 45–65 years), suggesting a time-period effect rather than a cohort effect. Similarly to data published elsewhere, mortality rates for thyroid cancer remained virtually unchanged in the USA over the whole study period at 0.5 deaths per 100,000 people in both 1975 and 2019. Notably, rates of metastasis at diagnosis remained stable at 0.4 cases per 100,000 people in both 1975 and 2019 [

38,

39].

4.1. How to Assess a Clinically Relevant Thyroid Nodule: The Role of Ultrasound

The first step in evaluating clinically relevant thyroid nodule is to measure the TSH level and perform US of the thyroid and cervical lymph nodes [

40]. A normal or elevated TSH level indicates that a thyroid nodule is non-functioning, while a low or suppressed TSH suggests primary hyperthyroidism, warranting a radionuclide thyroid uptake scan. Hyperfunctioning nodules rarely harbor malignancy and don't require fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Non-functioning or "cold" nodules should undergo FNAC if they meet specific clinical or ultrasound criteria. A comprehensive US report should describe thyroid parenchyma texture (homogeneous or heterogeneous), gland size, nodule location and sonographic characteristics, and presence/absence of suspicious cervical lymph nodes in both central and lateral compartments. The report should document nodule size in three dimensions, location (e.g., right upper lobe), and detailed sonographic features, including composition (solid, cystic proportion, or spongiform), echogenicity, margins, calcification presence and type, shape (particularly if taller than wide), and vascularity. These sonographic features, together with nodule size, determine malignancy risk and guide FNAC decision-making [

41,

42]. Given the nuances in sonographic appearances of different thyroid cancer histologies and the challenges posed by partially cystic nodules, some authors have suggested risk stratification based upon a constellation of sonographic features [

43,

44,

45] (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

In the absence of sonographically suspicious cervical lymph nodes, features associated with the highest risk for thyroid cancer can be used to triage smaller nodules for fine-needle biopsy, whereas nodules with sonographic appearance suggesting lower risk might be considered for fine-needle biopsy at a larger size as determined by maximal diameter. The sonographic appearance for most thyroid nodules can be generally classified in the categories of US patterns, which combine specific individual sonographic characteristics since the interobserver variability in reporting individual characteristics is moderate, even within controlled studies [

46,

47,

48]. In particular, different Thyroid Imaging-Reporting and Data Systems (TI-RADSs) offer a reliable framework for differentiating between benign and malignant nodules with some differences between them and slightly better performance of the American College of Radiologists TI-RADS (ACR TI-RADS) [

49]. Higher scores are more suggestive of malignancy, while lower scores indicate a benign disease. The TI-RADS level and the maximum diameter of nodules guide the decision to perform FNAC or undergo follow-up. Notably, highly suspicious nodules should be submitted to biopsy only if they measure 1 cm or larger. In comparison, nodules with a low risk for malignancy should be further investigated only when their size reaches 2.5 cm or more. Interestingly, however, Rucz and colleagues found comparable sensitivity and specificity for echogenicity alone (i.e., FNAC recommended in all hypoechoic nodules disregarding other characteristics) and five TIRADS systems in identifying malignancies in nodules in the 10-20 mm size range [

50]. A detailed review of TI-RADS systems is out of the scope of our present paper and readers are referred to updated reviews and comparative studies [

51,

52].

4.2. How to Manage a Thyroid Incidentaloma: an Open Debate

As detailed above, thyroid incidentalomas constitute a serious problem in terms of the induction of inappropriate diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, anxiety, patients’ discomfort, and costs [

53]. Even if the best way to avoid incidentalomas is not to perform US without apparent clinical indications, the problem remains when such negligible nodules are detected during imaging procedures performed for other reasons. A considerable debate is ongoing, especially in radiology literature, with some data showing no risk excess in not reporting thyroid incidentalomas [

54,

55]. Considering the exceedingly high number of incidentally detected thyroid nodules, the attached increase in incidental detection of small, smoldering, and clinically unrelevant thyroid carcinomas and flat mortality of thyroid cancer since decades, not reporting thyroid incidentalomas is likely a safe and cost-effective solution. However, it is likely hard to accept due to many reasons, including the absence of long-term prospective studies and potential medico-legal problems. Interestingly, Song and colleagues conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases to identify relevant studies reporting on the prevalence, follow-up, and risk of malignancy (ROM) of thyroid incidentalomas detected by CT and published before April 12, 2024. Thirty-eight studies involving 195,959 patients were included in the prevalence analysis, revealing a prevalence of thyroid incidentalomas on CT of 8.3% (confidence interval [CI], 7.4-9.3), higher in neck CT (16.5%, CI, 11.0-22.1) compared with chest CT (6.6%, CI, 5.3-7.9). Multiple incidentalomas were found in 27.0% (CI, 12.9-41.1) of patients. Of the nodules, 46.3% (CI, 32.3-60.3) were ≥1 cm, and 28.6% (CI, 19.9-37.3) were ≥1.5 cm. Thyroid ultrasounds, FNAC, and surgeries were performed in 34.9% (CI, 26.1-43.7), 28.4% (CI, 19.9-36.9), and 8.2% (CI, 2.1-14.4) of cases, respectively. Additionally, 25 studies with 6272 patients reported a ROM of 3.9% (CI, 3.0-4.9) for thyroid incidentalomas detected on CT. Notably, the ROM of nodules <1 cm and <1.5 cm was negligible (0.1%, CI, 0-0.8 and 0%, CI, 0-0.2, respectively). This is perfectly in line with the recommendation not to perform FNAC in subcentimetric nodules, even if at high risk based on TI-RADS [

56].

4.2.1. PET/CT Incidentalomas: A Particular Case

As 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography [

18F]FDG PET/CT becomes more commonly used for cancer investigation and staging, thyroid nodules with [

18F]FDG uptake are increasingly discovered incidentally, occurring in approximately 1-4% of [

18F]FDG PET/CT scans. These incidental [

18F]FDG-avid thyroid nodules carry a malignancy risk of 15-20%, substantially higher than nodules found through ultrasound, CT, or other imaging methods. Nevertheless, when malignancy is confirmed, most cases represent differentiated thyroid cancers with excellent outcomes even without intervention. Therefore, management decisions should carefully consider the patient's primary cancer diagnosis, age, and existing health conditions, as further investigation of an incidental [

18F]FDG-avid thyroid nodule may often be unnecessary [

57].

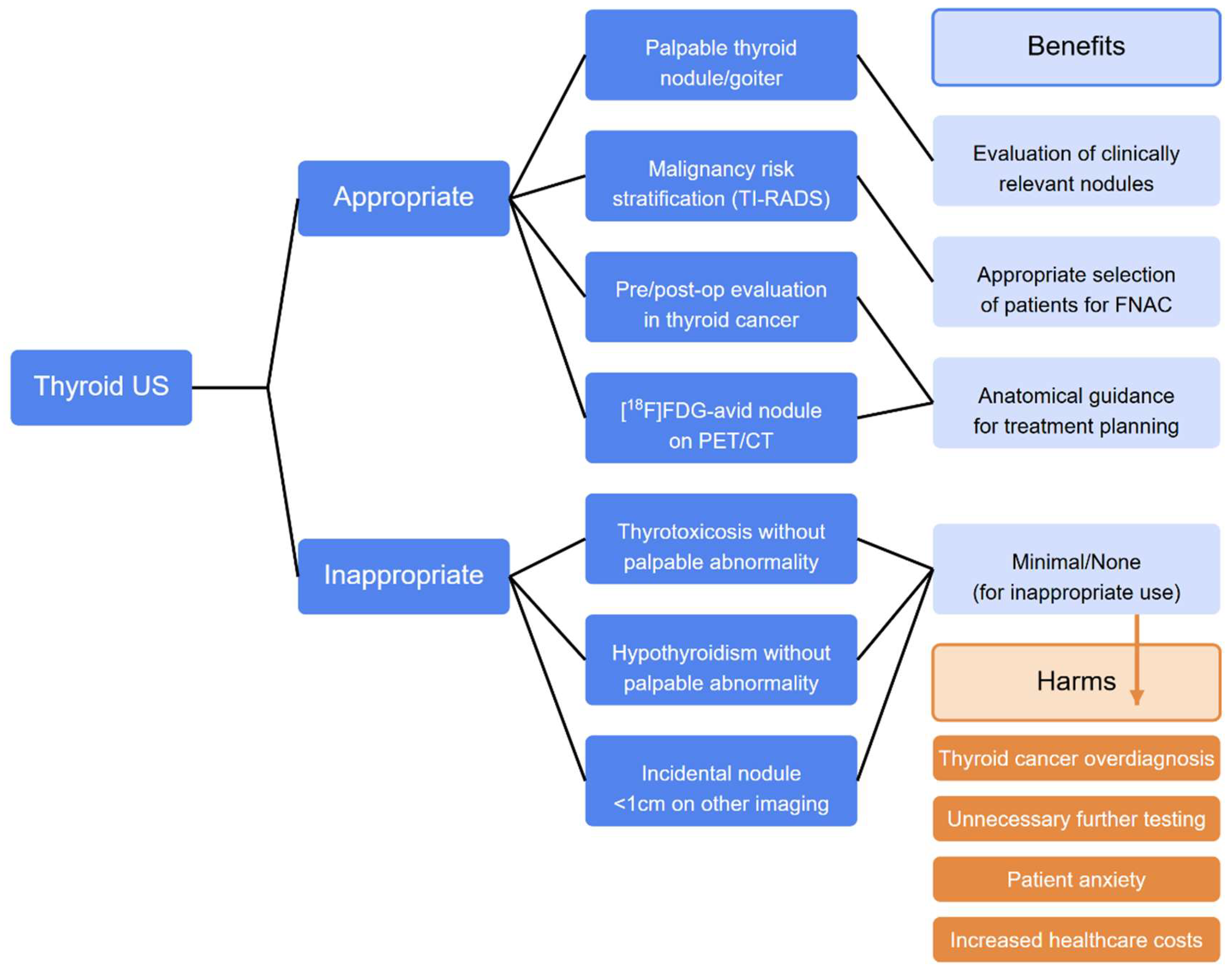

5. Cost-effectiveness and suggested recommendations

The excessive ordering of unnecessary or inappropriate medical tests constitutes overuse and represents inefficient resource allocation. In 2012, Berwick and Hackbarth estimated that 6% to 8% of U.S. annual healthcare expenditures (at least

$270 billion) could be categorized as overuse [

58]. Studies examining medical test overutilization in both hospital and ambulatory settings have prompted initiatives such as Choosing Wisely, the Right Care Alliance, and Wiser Healthcare [

59]. Several factors contribute to this problem, including media misrepresentation of weak evidence, leading many healthcare providers and patients to incorrectly believe that more testing invariably leads to better outcomes by potentially identifying treatable conditions. In clinical settings, physicians frequently order routine tests for various reasons, including self-referral practices [

60].Current indications for US in patients with thyroid dysfunctions are summarized in

Table 2 and a proposed flow-chart is illustrated in

Figure 6.

6. Conclusions

The overdiagnosis of thyroid nodules and cancer stems primarily from the improper use of US, which increases healthcare expenses and potential patient harm. This inappropriate use results from inadequate knowledge and implementation of guidelines, widespread availability of US equipment in various specialists' offices (with associated self-referral), the quick and uncomplicated nature of the procedure, and growing patient demand. Addressing this overutilization requires a better understanding of how frequently US is inappropriately used clinically and identifying contributing factors. Such data would enable the development of targeted interventions to reduce unnecessary US examinations, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and optimizing healthcare resource allocation. For now, we strongly suggest refraining from performing US in hyperthyroid and hypothyroid patients without palpable nodules and euthyroid patients without palpable abnormalities. No additional studies should be required in patients with subcentimetric nodules incidentally detected during non-thyroid-directed imaging procedures. With this simple and well-supported action, the number of US will decrease without harm to our patients, leaving the rare patients with relevant thyroid cancers to have the best service in terms of diagnosis and treatment. So, it probably is not the time to shut down our US machines, but, for sure, it is time to reason a little bit more before moving the probe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G. and P.P.O.; methodology, L.G.; investigation, L.G.; data curation, L.G. and P.P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing—review and editing, L.G. and P.P.O.; supervision, L.G and P.P.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haymart, M.R.; Banerjee, M.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Caoili, E.; Norton, E.C. Thyroid Ultrasound and the Increase in Diagnosis of Low-Risk Thyroid Cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zevallos, J.P.; Hartman, C.M.; Kramer, J.R.; Sturgis, E.M.; Chiao, E.Y. Increased Thyroid Cancer Incidence Corresponds to Increased Use of Thyroid Ultrasound and Fine-Needle Aspiration: A Study of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Cancer 2015, 121, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udelsman, R.; Zhang, Y. The Epidemic of Thyroid Cancer in the United States: The Role of Endocrinologists and Ultrasounds. Thyroid 2014, 24, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Welch, H.G. Korea’s Thyroid-Cancer “Epidemic”--Screening and Overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 1765–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bruel, A.; Francart, J.; Dubois, C.; Adam, M.; Vlayen, J.; De Schutter, H.; Stordeur, S.; Decallonne, B. Regional Variation in Thyroid Cancer Incidence in Belgium Is Associated with Variation in Thyroid Imaging and Thyroid Disease Management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.K.; Iñiguez-Ariza, N.M.; Singh Ospina, N.; Lincango-Naranjo, E.; Maraka, S.; Brito, J.P. Inappropriate Use of Thyroid Ultrasound: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrine 2021, 74, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Jacome, C.; Segura Torres, D.; Fan, J.W.; Garcia-Bautista, A.; Golembiewski, E.; Duran, M.; Loor-Torres, R.; Toro-Tobon, D.; Singh Ospina, N.; Brito, J.P. Drivers of Thyroid Ultrasound Use: A Retrospective Observational Study. Endocr Pract 2023, 29, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, D.M.; Frates, M.C. Ultrasound of the Normal Thyroid with Technical Pearls and Pitfalls. Radiol Clin North Am 2020, 58, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripura, N.G.; Malik, A.; Khanna, G.; Mohil, R.S. Role of Ultrasonography (USG) and Color Doppler in the Evaluation of Thyroid Nodules and Its Association with USG-Guided FNAC - A Cross-Sectional Study. J Family Med Prim Care 2024, 13, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiina, T.; Nightingale, K.R.; Palmeri, M.L.; Hall, T.J.; Bamber, J.C.; Barr, R.G.; Castera, L.; Choi, B.I.; Chou, Y.H.; Cosgrove, D.; et al. WFUMB Guidelines and Recommendations for Clinical Use of Ultrasound Elastography: Part 1: Basic Principles and Terminology. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015, 41, 1126–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Baek, J.H.; Chung, J.; Ha, E.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lim, H.K.; Moon, W.J.; Na, D.G.; Park, J.S.; et al. Ultrasonography Diagnosis and Imaging-Based Management of Thyroid Nodules: Revised Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology Consensus Statement and Recommendations. Korean J Radiol 2016, 17, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravets, I. Hyperthyroidism: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2016, 93, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.S.; Burch, H.B.; Cooper, D.S.; Greenlee, M.C.; Laurberg, P.; Maia, A.L.; Rivkees, S.A.; Samuels, M.; Sosa, J.A.; Stan, M.N.; et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1343–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Bartalena, L.; Hegedüs, L.; Leenhardt, L.; Poppe, K.; Pearce, S.H. 2018 European Thyroid Association Guideline for the Management of Graves’ Hyperthyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2018, 7, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Avram, A.M.; Ovčariček, P.P.; Clerc, J. Thyroid Functional and Molecular Imaging. Presse Med 2022, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanella, L.; Avram, A.M.; Iakovou, I.; Kwak, J.; Lawson, S.A.; Lulaj, E.; Luster, M.; Piccardo, A.; Schmidt, M.; Tulchinsky, M.; et al. EANM Practice Guideline/SNMMI Procedure Standard for RAIU and Thyroid Scintigraphy. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2019 46:12 2019, 46, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (UK), N.G.C. Tests for People with Confirmed Thyrotoxicosis. Tests for people with confirmed thyrotoxicosis: Thyroid disease: assessment and management: Evidence review H.

- Giovanella, L.; Campennì, A.; Tuncel, M.; Petranović Ovčariček, P. Integrated Diagnostics of Thyroid Nodules. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanella, L.; Avram, A.; Clerc, J. Molecular Imaging for Thyrotoxicosis and Thyroid Nodules. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2021, 62, 20S–25S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview | Thyroid Disease: Assessment and Management | Guidance | NICE.

- Giovanella, L.; Ceriani, L.; Ghelfo, A. Second-Generation Thyrotropin Receptor Antibodies Assay and Quantitative Thyroid Scintigraphy in Autoimmune Hyperthyroidism. Horm Metab Res 2008, 40, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Görges, R.; Giovanella, L. Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Semin Nucl Med 2024, 54, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzoli, R.; Bagnasco, M.; Giavarina, D.; Bizzaro, N. TSH Receptor Autoantibody Immunoassay in Patients with Graves’ Disease: Improvement of Diagnostic Accuracy over Different Generations of Methods. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2012, 12, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scappaticcio, L.; Trimboli, P.; Keller, F.; Imperiali, M.; Piccardo, A.; Giovanella, L. Diagnostic Testing for Graves’ or Non-Graves’ Hyperthyroidism: A Comparison of Two Thyrotropin Receptor Antibody Immunoassays with Thyroid Scintigraphy and Ultrasonography. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020, 92, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topliss, D.J.; Eastman, C.J. 5: Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Hypothyroidism. Med J Aust 2004, 180, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, P.C.; Feddema, P.H.; Michelangeli, V.P.; Leedman, P.J.; Chew, G.T.; Knuiman, M.; Kaye, J.; Walsh, J.P. Investigations of Thyroid Hormones and Antibodies Based on a Community Health Survey: The Busselton Thyroid Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006, 64, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devdhar, M.; Ousman, Y.H.; Burman, K.D. Hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2007, 36, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, H.J.; Cobin, R.H.; Duick, D.S.; Gharib, H.; Guttler, R.B.; Kaplan, M.M.; Segal, R.L.; Garber, J.R.; Hamilton, C.R.; Handelsman, Y.; et al. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS MEDICAL GUIDELINES FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE FOR THE EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF HYPERTHYROIDISM AND HYPOTHYROIDISM. Endocr Pract 2002, 8, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K. V; Kennedy, A.G.; Repp, A.B.; Tompkins, B.J.; Gilbert, M.P. Predictors and Consequences of Inappropriate Thyroid Ultrasound in Hypothyroidism. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, G.J.; Singh Ospina, N.; Brito, J.P. Overuse of Thyroid Ultrasound. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2023, 30, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don’t Routinely Order a Thyroid Ultrasound in Patients with Abnormal Thyroid Function Tests If There Is No Palpable Abnormality of the Thyroid Gland. Available online: https://www.choosingwisely.org.au/recommendations/esa1 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Endocrinology and Metabolism Recommendations. Available online: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/recommendation/endocrinology-and-metabolism/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Dean, D.S.; Gharib, H. Epidemiology of Thyroid Nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 22, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Ming, X.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yao, M.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Mapping Global Epidemiology of Thyroid Nodules among General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1029926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völzke, H.; Lüdemann, J.; Robinson, D.M.; Spieker, K.W.; Schwahn, C.; Kramer, A.; John, U.; Meng, W. The Prevalence of Undiagnosed Thyroid Disorders in a Previously Iodine-Deficient Area. Thyroid 2003, 13, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Grani, G.; Lamartina, L.; Filetti, S.; Mandel, S.J.; Cooper, D.S. The Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules: A Review. JAMA 2018, 319, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Maso, L.; Vaccarella, S.; Franceschi, S. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Overdiagnosis in the USA. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025, 13, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.M.; Luu, M.; Sacks, W.L.; Orloff, L.; Wallner, L.P.; Clair, J.M.S.; Pitt, S.C.; Ho, A.S.; Zumsteg, Z.S. Trends in Incidence, Metastasis, and Mortality from Thyroid Cancer in the USA from 1975 to 2019: A Population-Based Study of Age, Period, and Cohort Effects. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025, 13, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R.; Davis, A.; Verma, V. Thyroid Nodules: Advances in Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician 2020, 102, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith-Bindman, R.; Lebda, P.; Feldstein, V.A.; Sellami, D.; Goldstein, R.B.; Brasic, N.; Jin, C.; Kornak, J. Risk of Thyroid Cancer Based on Thyroid Ultrasound Imaging Characteristics: Results of a Population-Based Study. JAMA Intern Med 2013, 173, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, J.P.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Nofal, A. Al; Boehmer, K.R.; Leppin, A.L.; Reading, C.; Callstrom, M.; Elraiyah, T.A.; Prokop, L.J.; Stan, M.N.; et al. The Accuracy of Thyroid Nodule Ultrasound to Predict Thyroid Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, E.; Majlis, S.; Rossi, R.; Franco, C.; Niedmann, J.P.; Castro, A.; Dominguez, M. An Ultrasonogram Reporting System for Thyroid Nodules Stratifying Cancer Risk for Clinical Management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, 1748–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.T.; Dong, J.L.; Ki, H.B.; Woo, C.P.; Youn, S.L.; Jung, E.C.; Jong, M.L.; Moo, I.K.; Bong, Y.C.; Ho, Y.S.; et al. Diagnostic Value of Ultrasonography to Distinguish between Benign and Malignant Lesions in the Management of Thyroid Nodules. Thyroid 2007, 17, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, H.; Haraguchi, K.; Hiejima, Y.; Fukunari, N.; Fujimoto, Y.; Katagiri, M.; Koyanagi, N.; Kurita, T.; Miyakawa, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Distinct Diagnostic Criteria for Ultrasonographic Examination of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Multicenter Study. Thyroid 2005, 15, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.J.; So, L.J.; Jeong, H.L.; Dong, G.N.; Baek, J.H.; Young, H.L.; Kim, J.; Hyun, S.K.; Jun, S.B.; Dong, H.L. Benign and Malignant Thyroid Nodules: US Differentiation--Multicenter Retrospective Study. Radiology 2008, 247, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, G.; Royer, B.; Bigorgne, C.; Rouxel, A.; Bienvenu-Perrard, M.; Leenhardt, L. Prospective Evaluation of Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System on 4550 Nodules with and without Elastography. Eur J Endocrinol 2013, 168, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.P.; Lee, J.J.; Lin, J.L.; Chuang, S.M.; Chien, M.N.; Liu, C.L. Characterization of Thyroid Nodules Using the Proposed Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS). Head Neck 2013, 35, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSaedi, A.H.; Almalki, D.S.; ElKady, R.M. Approach to Thyroid Nodules: Diagnosis and Treatment. Cureus 2024, 16, e52232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucz, K.; Hegedűs, L.; Bonnema, S.J.; Frasoldati, A.; Jambor, L.; Kovacs, G.L.; Papini, E.; Russ, G.; Karanyi, Z.; Nagy, E. V.; et al. Echogenicity as a Standalone Nodule Characteristic Is Not Inferior to the TIRADS Systems in the 10-20 Mm Nodule Diameter Range in Patient Selection for Fine Needle Aspiration: A Pilot Study. Eur Thyroid J 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, W.D.; Teefey, S.A.; Reading, C.C.; Langer, J.E.; Beland, M.D.; Szabunio, M.M.; Desser, T.S. Comparison of Performance Characteristics of American College of Radiology TI-RADS, Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology TIRADS, and American Thyroid Association Guidelines. American Journal of Roentgenology 2018, 210, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.P.; Antunes, C.; Caseiro-Alves, F.; Donato, P. Analysis of 665 Thyroid Nodules Using Both EU-TIRADS and ACR TI-RADS Classification Systems. Thyroid Res 2023, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, J.K.; Nguyen, X. V. Understanding the Risks and Harms of Management of Incidental Thyroid Nodules: A Review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017, 143, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, R.H.; Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B.; White, M.G.; Kaplan, E.L.; Angelos, P. Thyroid Incidentalomas and the Overdiagnosis Conundrum. Int J Endocr Oncol 2016, 3, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, T.; Gravely, A.; Westanmo, A.; Billington, C. Prevalence of Thyroid Incidentalomas from 1995 to 2016: A Single-Center, Retrospective Cohort Study. J Endocr Soc 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Wu, C.; Kasmirski, J.; Gillis, A.; Fazendin, J.; Lindeman, B.; Chen, H. Incidental Thyroid Nodules on Computed Tomography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Examining Prevalence, Follow-Up, and Risk of Malignancy. Thyroid 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsley, J.; Balasubramanian, S.P.; Madani, G.; Munday, J.; Roques, T.; Rowe, C.W.; Touska, P.; Boelaert, K. Consensus Statement on the Management of Incidentally Discovered FDG Avid Thyroid Nodules in Patients Being Investigated for Other Cancers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2024, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M.; Hackbarth, A.D. Eliminating Waste in US Health Care. JAMA 2012, 307, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.F.; Griffiths, R. Use and Overuse of Diagnostic Neck Ultrasound in Ontario: Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Canadian Family Physician 2020, 66, e62. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.F.; Irish, J.; Groome, P.; Griffiths, R. Access, Excess, and Overdiagnosis: The Case for Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Med 2014, 3, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).