1. Introduction

Diagnostic imaging plays a crucial role in dentistry by providing essential anatomical information that complements clinical examinations to identify the presence and severity of oral conditions. Imaging technology influences all aspects of oral healthcare, ranging from monitoring disease progression to treatment planning and assessment of therapeutic outcomes [

1]. Despite their significance, dental practices predominantly rely on ionizing radiation-based imaging modalities, which pose cumulative radiation exposure risks [

1,

2]. Periapical, bitewing, and panoramic radiographs and Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) are the most commonly used imaging methods in dentistry. However, these imaging techniques often fail to effectively visualize the soft tissues [

3]. Both 2D and 3D imaging approaches may not detect early inflammatory changes limited to soft tissues, which typically precede noticeable bone loss [

4]. For radiographic identification of these alterations, significant mineral loss (30-50%) is usually necessary to clearly observe periapical and periodontal lesions [

5]. Although advanced 3D imaging techniques, particularly CBCT, have enhanced the understanding of anatomical structures and pathology, they still involve ionizing radiation, even when protocols aim to minimize doses [

6]. The intricate anatomy of the dentomaxillofacial region poses difficulties for current imaging techniques due to the combination of different types of hard and soft tissues, as well as air and fluid-filled spaces. This region encompasses critical anatomical structures, such as the maxilla, mandible (including the neurovascular canals), nose, paranasal sinuses, and oral cavity, including teeth [

7]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is gaining recognition not only for imaging the head and neck but also for evaluating the dentoalveolar complex. Traditionally, it has been used in head and neck imaging to examine the temporomandibular joint(TMJ), salivary glands, and soft tissue abnormalities. MRI offers benefits over conventional radiography, including the absence of ionizing radiation and better soft tissue differentiation [

8]. The absence of ionizing radiation in MRI makes it an ideal method for continuous research and repeated scans in children and young adults, who are particularly at risk from the cumulative effects of ionizing radiation [

9,

10]. Although there are some contraindications for MRI, especially at higher magnetic field strengths, dental materials, and orthodontic devices are typically not prohibited. However, these items may create artifacts that can potentially affect the quality of the images produced [

11]. Recent MRI advancements that reduce the time between signal excitation and acquisition now enable solid imaging within minutes, a process that previously took hours. These techniques hold great promise for dental MRI. Ex vivo Ultrashort Echo Time (UTE), Zero Echo Time (ZTE) MRI outperform conventional MRI and CBCT in both resolution and detail. Notably, these methods can differentiate multiple components within the solid structure of the tooth, an area that previously yielded no detectable signal [

3]. This review outlines the advancements in dental MRI, highlighting the potential of UTE, ZTE, and Sweep Imaging with Fourier Transformation (SWIFT) sequences in overcoming the limitations of conventional imaging techniques. By discussing the role of intraoral coils and the expanding applications of MRI in dentistry, this article emphasizes the evolving landscape of diagnostic imaging. As these innovations continue to refine image quality and clinical utility, dental MRI stands poised to transform oral healthcare by providing a non-ionizing, high-resolution alternative for both hard and soft tissue assessment.

2. Challenges and Limitations of Conventional MRI in Dental Imaging

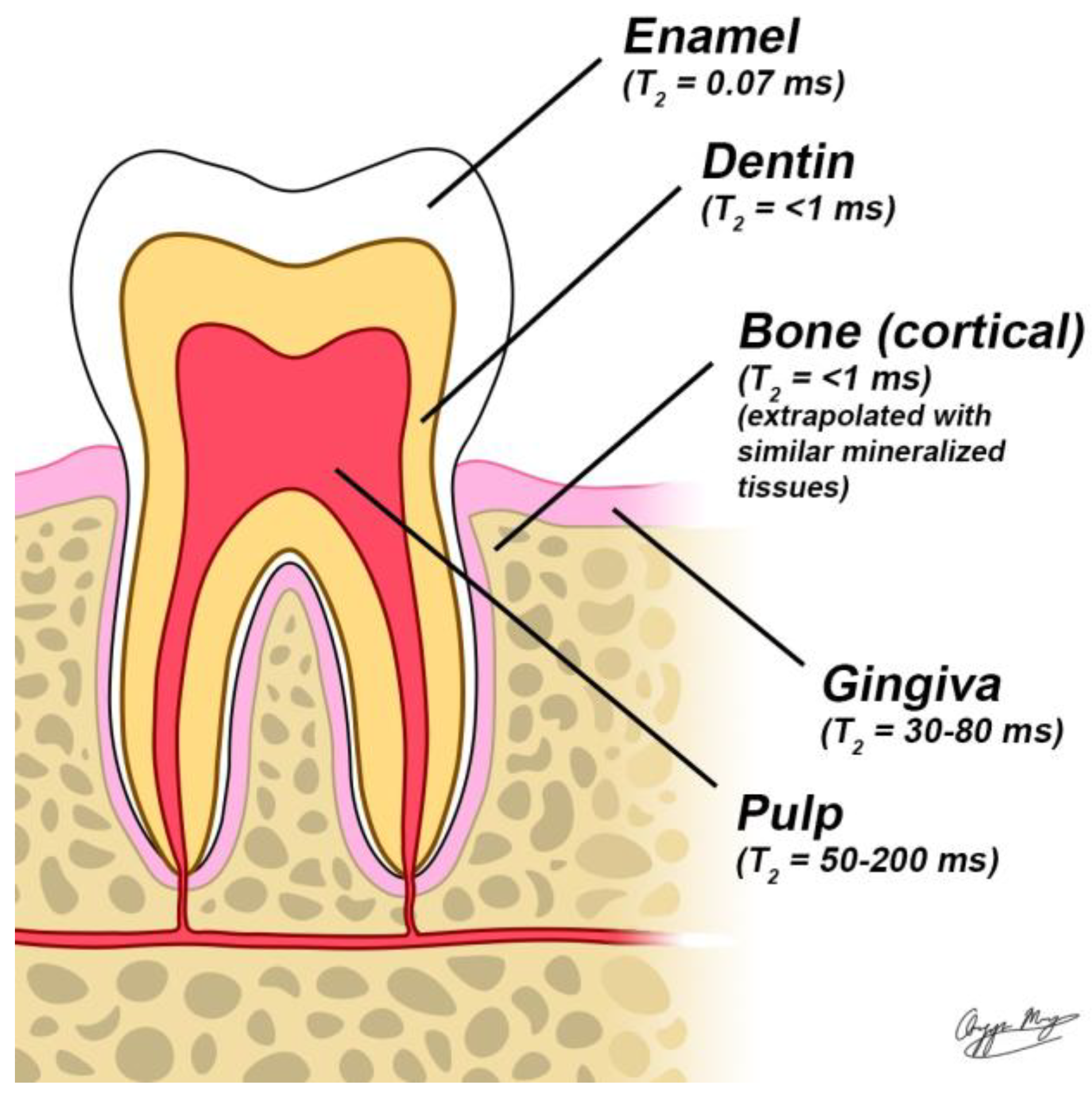

MRI is a powerful, non-invasive imaging modality for diagnosing and monitoring soft tissue conditions without exposing patients to ionizing radiation. It works by detecting signals from hydrogen nuclei in water molecules, commonly referred to as the "water signal." This signal is generated when a radiofrequency (RF) pulse excites nuclear spins, causing them to resonate within a strong static magnetic field. However, conventional MRI struggles to capture detailed images of teeth due to their high mineral content. Dentin is composed of roughly 50% minerals by volume, while enamel consists of about 90%, with the remainder made up of water and proteins. This composition limits the visibility of dental structures in standard MRI scans [

12]. Additionally, the restricted molecular motion of water within these highly mineralized structures leads to rapid signal decay after RF excitation, known as Free induction decay (FID). This decay is characterized by the transverse relaxation time (T2), which averages approximately 200 μs for dentin [

13] and 60 μs for enamel [

14]. These short decay times fall well below the duration required for conventional MRI pulse sequences to complete spatial encoding using pulsed magnetic field gradients, which typically require over 1 ms. Consequently, the signal from mineralized dental tissues fades before MRI signal digitization, making these structures appear as dark or black areas in MRI images. As a result, traditional MRI applications in dentistry have been restricted to imaging the pulp, attached periodontal membrane, and surrounding soft tissues, or have depended on indirect visualization of enamel and dentin using MRI-visible contrast agents [

15,

16,

17].

3. Advances in Short T2 MRI Sequences for Dental Hard Tissue Visualization

Recent advancements in pulse sequence technology have enabled the visualization of highly mineralized structures such as enamel, dentin, and bone, which were previously difficult to image using conventional MRI. These techniques, commonly referred to as short T2 sequences, are designed to capture the rapidly decaying T2 signal characteristic of hard tissues. Among the most notable short T2 sequences are Ultrashort Echo Time (UTE), Zero Echo Time (ZTE), and Sweep Imaging with Fourier Transformation (SWIFT) all of which have demonstrated promising results in dental imaging [

18].

4. Ultrashort Echo Time (UTE)

UTE imaging encompasses MRI sequences designed for visualizing tissues with T2 relaxation times shorter than 10 ms. The fundamental 2D UTE sequence employs two short half RF pulses: the first is applied with a negative gradient, and the second with a positive gradient, effectively simulating a single complete excitation pulse. Data acquisition begins as soon as the readout gradient is activated [

19,

20,

21].The collected data contribute to k-space, mapped radially from its center outward in multiple steps, typically ranging from 128 to 512. These data points are then reconstructed into a rectangular matrix, such as 512×512, and transformed into an image using a two-dimensional Fourier Transform (FT) [

22,

23].

For imaging ultrashort T2 components, rapid signal acquisition immediately after excitation is crucial. This necessitates fast transmit/receive switching coils and specialized hardware to minimize signal decay. While a high B0 field is not strictly required for optimal UTE acquisition, strong field strength enhances signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly for nuclei with lower signal sensitivity than hydrogen, such as phosphorus and sodium. Additionally, high-gradient performance—both in terms of slew rate and amplitude—is essential to rapidly ramp up gradients post-RF pulse. A high-performance RF receiver system is also necessary to capture signals efficiently without data loss [

24].

However, the rapid gradient switching and short receiver sampling periods required in UTE sequences can induce eddy currents in the scanner’s conductive structures, leading to artifacts, localization errors, and signal distortions [

25,

26]. These imperfections are also observed in non-Cartesian MRI acquisitions, such as radial and spiral imaging, and have been mitigated using methods like pre-emphasis corrections, imaging-based gradient measurements (IGM), and gradient impulse response function (GIRF) techniques [

27,

28]. To address eddy current effects in UTE imaging, a ramped hybrid encoding (RHE) approach has been introduced. This method applies an initial low gradient during RF excitation to minimize slice selectivity, followed by a gradient ramp-up to reduce overall sampling duration. RHE-UTE has demonstrated improved spatial resolution for short T2 species and reduced chemical shift artifacts compared to conventional 3D-UTE techniques. Additionally, integrating RHE-UTE with a one-dimensional dynamic single-point imaging (SPI) method enables high-resolution k-space sampling, further enhancing imaging performance [

29]

5. Zero Echo Time (ZTE)

In ZTE imaging, the encoding gradient is activated before the RF pulse, theoretically resulting in a zero echo time (TE). This technique employs a short hard-pulse excitation with a small flip angle while the gradients in all three spatial directions are gradually adjusted. Compared to UTE, ZTE sequences impose greater limitations on flip angles and readout bandwidths. However, the gradual gradient adjustments contribute to significantly reduced acoustic noise and mitigate eddy current effects, making ZTE a highly stable imaging method. Data acquisition follows a 3D radial center-out approach, with k-space reconstruction performed through gridding and Fourier Transform (FT), similar to UTE imaging. In practice, a short delay (δ) occurs after RF excitation due to the time required for transmit/receive switching. To compensate for this data gap, an oversampling technique is applied using a linear algebra-based reconstruction scheme. While effective, large-scale oversampling increases data volume, necessitating substantial computational memory for processing [

30,

31].

To enhance k-space filling, an alternative method known as Pointwise Encoding Time Reduction with Radial Acquisition (PETRA) has been introduced [

32]. This approach integrates radial mapping with Cartesian single-point acquisition, enabling accurate filling of the central k-space region. PETRA allows for improved SNR by capturing more signal from short T2 tissues before significant decay occurs. However, this method requires the imaged object to fit within the primary lobe of the sinc-shaped excitation profile. To address potential artifacts caused by inhomogeneous excitation, a correction algorithm using a quadratic phase-modulated RF pulse has been developed, allowing for extended RF pulses with lower peak power, making PETRA more suitable for clinical MRI systems. PETRA-based imaging has demonstrated superior performance compared to conventional ZTE techniques and has been successfully implemented in 1.5T and 3T MRI systems for hard tissue imaging [

33,

34].

Despite its advantages, ZTE imaging faces technical challenges, including the need for rapid RF switching and robust hardware capable of handling large data volumes. Recent advancements have led to the development of custom imaging consoles equipped with high-speed spectrometers, pulse generators, and real-time data storage solutions. These enhancements have facilitated reductions in RF excitation pulses and transmit/receive switching times. However, concerns remain regarding the large excitation bandwidth, specific absorption rate (SAR), and associated imaging artifacts. Further refinements, such as the use of amplitude- and frequency-modulated pulses for broader RF excitation and improved suppression of long T2 signals, have significantly advanced ZTE imaging for clinical applications [

35,

36].

6. Sweep Imaging with Fourier Transformation (SWIFT)

The SWIFT technique, introduced by Idiyatullin et al., integrates key elements of three fundamental Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) approaches: continuous wave (CW), pulsed, and stochastic NMR. It employs a swept RF excitation similar to CW NMR but at a faster rate, acquires signals over time like pulsed NMR, and utilizes correlation-based extraction methods characteristic of stochastic NMR. This combination enables an MRI sequence capable of nearly simultaneous excitation and acquisition, making it particularly effective for detecting ultrashort T2 components.

In SWIFT imaging, RF pulses are applied in sequences with a designated duration (Tp) in the millisecond range. Each pulse is segmented into multiple parts, during which the RF signal remains active for a specific time interval (τp) following a brief delay. Signal acquisition occurs at τa after each segment, allowing for the collection of frequency-encoded projections. These projections are subsequently reconstructed using a 3D back-projection or gridding algorithm, followed by image formation through a cross-correlation method. However, the time required for transitions between pulse segments imposes constraints on signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and image resolution.

Several refinements of the SWIFT sequence have been developed to help mitigate hardware constraints, lower specific absorption rate (SAR) and improve acquisition efficiency, enhancing the overall performance of SWIFT imaging. The advancements include continuous SWIFT (cSWIFT), multiple excitation bands (MB-SWIFT), and gradient-modulated SWIFT (GM-SWIFT) [

37,

38].

7. Dental MRI Coils: Advancements and Challenges in Imaging Quality

Dental MRI offers high-contrast imaging of soft tissues and specialized imaging of hard tissues such as teeth and bones. However, achieving high spatial resolution remains challenging due to the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) inherent in small voxel volumes. Specialized radiofrequency (RF) coils are essential for enhancing SNR and improving image quality in dental MRI [

39].

8. Body and Surface Coils

Body Coils:

Clinical MRI scanners are typically equipped with large RF coils within the bore, known as body coils, designed to energize the entire body. These body coils transmit radio waves, regardless of the anatomy being imaged. To record the RF signal emitted from the patient, anatomy-specific receiver or surface coils are used.

Surface Coils:

Surface coils are placed adjacent to the anatomy being imaged, enhancing the detection of the RF signal. In dental MRI, anatomy-specific coils, such as extraoral or intraoral coils, improve resolution by focusing on a smaller Field of View (FOV). These coils allow for higher-resolution imaging, which is crucial for detecting small anatomical changes in dental structures, such as the teeth, periodontium, and alveolar bone.

Gradient Coils

Gradient coils are located within the body of the magnet and are responsible for creating small magnetic field gradients in the x-, y-, and z-directions during scanning. These gradients allow for spatial information recording and produce the noise associated with MRI scans. In pulse sequences demanding rapid and large gradient changes (such as functional MRI), the noise can be significant [

40]

Innovative Coil Designs for Dental MRI Intraoral Coils:

Cable-bound intraoral coils, placed between teeth, have demonstrated resolutions of 300 μm³ with a 12 cm³ FOV in 4.5 minutes. However, these designs struggle to capture critical structures like the periapical region or alveolar bone [

41].

- 1.

Wireless Inductively-Coupled Coils:

These coils offer localized sensitivity with resolutions ranging from 350–800 μm³. Their wireless design improves patient comfort and reduces setup complexity, making them a promising option for dental MRI [

42].

- 2.

Multi-Channel RF Arrays:

A 7-channel RF coil array with flexible "wings" has been developed to enhance imaging performance while prioritizing patient comfort. This design allows for angular adjustments for optimal placement near target areas and supports parallel imaging, which enables faster acquisition times [

43]

- 3.

SWIFT-Based Coils:

SWIFT technology utilizes specialized intraoral coils to simultaneously image both hard and soft tissues without ionizing radiation. Invivo studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using a one-sided shielded single-loop intraoral coil (40 mm diameter) placed between the cheek and teeth, secured with a 2 mm thick Teflon bite fork for stable positioning. The coil's close proximity to the region of interest enhances SNR), improving resolution while maintaining clinically feasible scan times. The reduced gradient demands of SWIFT also make it a promising option for low-noise, high-resolution dental imaging. SWIFT’s lower demand on gradient coil changes makes it more feasible for dental applications, where high-quality imaging of hard tissues is required [

41].

- 4.

Transverse Loop Coils (tLoop and mtLoop)

The transverse loop coil (tLoop) introduced an innovative design for dental MRI, with the coil plane orthogonal to B₀, enabling full dental arch imaging while minimizing signals from adjacent tissues like cheeks and tongue. Despite its advantages, the tLoop faced limitations such as steep sensitivity gradients, signal voids at the incisors due to feed port gaps, and discomfort caused by its rigid geometry. To address these issues, the modified transverse loop coil (mtLoop) was developed with significant improvements. These include overlapping feed port conductors to eliminate signal voids, a bent posterior section for enhanced comfort, and a parallel plate capacitor to reduce eddy currents by 10%. Operating in receive-only mode, the mtLoop achieves an 11× SNR improvement at incisors and 2.5× at molar roots, enabling isotropic resolutions of 250 μm³ within a 2-minute scan time. These advancements make the mtLoop a promising solution for high-resolution, patient-friendly dental imaging [

44].

- 5.

Coupled Stack-Up Volume Coils:

For low-field MRI systems, coupled stack-up volume coils enhance RF field efficiency by ensuring strong coupling between coil elements. This improves both transmit/receive efficiency and field homogeneity, making it effective for dental imaging in lower-field systems [

45].

Challenges in Dental MRI Coils

- 1.

Low SNR and Resolution:

Current clinical MRI systems, despite advanced gradient hardware capable of 0.2 mm resolution, still struggle to match the spatial resolution of MDCT or CBCT. SNR is directly affected by voxel size, making it difficult to balance resolution with imaging time.

- 2.

Design Limitations:

Standard surface coils, commonly used for dental MRI, face challenges such as handling difficulties and reduced patient comfort. Conventional head-and-neck coils often have a low filling factor for dental imaging, reducing sensitivity.

- 3.

Material and Miniaturization Challenges:

Coils must be biocompatible, lightweight, and ergonomically designed for intraoral or facial use. These requirements complicate manufacturing, especially as miniaturization is necessary for high-quality dental imaging.

- 4.

FOV Limitations:

Dental MRI typically captures an FOV covering the entire head, resulting in lower resolution and challenges in isolating fine anatomical features, such as individual teeth.

- 5.

Gradient Hardware Constraints:

Advanced sequences like UTE and SWIFT are constrained by the time required for RF excitation and gradient ramping, limiting their ability to produce diagnostic-quality images within clinically feasible scanning durations [

39]. The future of dental MRI is set to be transformed by cutting-edge advancements in coil technology. Custom-designed coils, tailored to individual patient anatomy, will significantly enhance the SNR and improve diagnostic precision, leading to greater imaging accuracy. Integrating these specialized coils with advanced sequences such as UTE, ZTE, and SWIFT will further optimize the visualization of fast-relaxing tissues, delivering superior contrast and highly detailed imaging. At the same time, ensuring compliance with biocompatibility standards and addressing miniaturization challenges will remain paramount, as manufacturers strive to enhance patient safety, comfort, and regulatory approval.

9. Clinical Applications of Short T2 Sequences in Dentistry

In dentistry, MRI has traditionally been employed to diagnose internal derangements related to the TMJ. MR imaging can reveal disc shape, position, and direction of displacement, as well as any signs of inflammation, such as effusion, and to some extent indicate degenerative joint disease. Additionally, MRI was utilized to assess infectious or inflammatory conditions in the maxillofacial region, examine soft tissue pathologies of the salivary glands, maxillary sinuses, and masticatory muscle abnormalities, as well as identify vascular anomalies and lesions [

46]. As previously discussed, short sequences like UTE, ZTE, and SWIFT have greatly enhanced the visualization of mineralized dental tissues, including enamel, dentin, and bone. These sequences open new opportunities for dental MRI, enabling a thorough evaluation of hard tissues in conjunction with soft tissue structures. The following section explores the potential uses of these sequences in dentistry, emphasizing their importance in diagnosing and monitoring a wide range of dental conditions.

Imaging of Teeth:

The use of MRI in dentistry is steadily increasing, but imaging dental tissues remains challenging due to their short relaxation times. The first UTE MR image of teeth was captured in 2003 using the Fat-suppressed UTE (FUTE) method on a 1.5 T system (Gatehouse & Bydder, 2003) [

47]. Later, whole-body 3 T MRI scans were conducted on human subjects with a total scan time of 10 minutes. UTE sequences with a TE of 50 μs provided detailed visualization of dental structures, including enamel. Furthermore, 3D-UTE imaging not only allowed for high-resolution tooth anatomy visualization but also helped estimate relative T2* values, which have been linked to the detection of dental caries [

48].

The SWIFT images provide a detailed visualization of dental anatomy, including enamel, dentin, and pulpal structures. Due to its lower water content and shorter T2 relaxation time, enamel exhibits a less intense signal compared to dentin. The observed signal intensities in the pulp, dentin, and enamel follow an approximate ratio of 100:35:10. This pattern is consistent with their respective water content levels, which are roughly 100:20:8. Because MRI signal strength is strongly influenced by the amount of water present in tissues, structures with higher water content, such as the pulp, appear much brighter than those with lower water content, like enamel. This correlation reinforces the reliability of MRI in reflecting differences in dental tissue composition. These SWIFT images lack significant T2 weighting, unlike Gradient Echo (GRE) images, allowing for clear visualization of all dental tissues [

47]. (

Figure 1)

Detection of Dental Caries:

In early stages of dental caries, the decayed area experiences acid buildup, leading to the demineralization of the tooth, which increases tissue porosity and potentially allowing saliva to seep in. These factors raise local proton density and prolong the T2 spins of protons. The resulting high-intensity signal from water, combined with the absence of signal from adjacent mineralized tissues, creates a contrast that helps distinguish caries from the surrounding tooth structure. However, this signal can only be detected using short TE MR sequences. The random dephasing caused by residual minerals limits the visualization of caries in conventional spin echo images. In more advanced lesions, an increase in T2 values and minimal random dephasing, caused by a notable reduction in mineral content, enhance the visualization of advanced lesions in spin-echo images [

48]. In addition, UTE sequences generated less severe metal artifacts compared to conventional spino echo. The 3D UTE MRI demonstrated comparable sensitivity to both intermediate and advanced lesions, significantly outperforming X-ray and conventional spin-echo MRI methods for early-stage lesions [

49].

Dental Restorative Materials

Using UTE-MRI at both 3T and 9.4T, researchers have demonstrated the ability to differentiate dental hard tissues and restorative materials based on their unique T1 and T2* relaxation properties and signal intensities. In the 3T study, dentin exhibited a T1 of 545 ms—significantly longer than restorative materials like Harvard Cement (30 ms) and Provicol QM (166 ms)—due to its higher water and organic content. T2* values for dentin (478 μs) were comparable to materials like Rebilda DC (337 μs), though restorative materials showed greater variability due to differences in composition [

50]. In contrast, the 9.4T UTE-MRI study found that dentin appeared with moderate signal intensity, while gutta-percha showed no signal (signal void), and AH Plus sealer exhibited a slightly higher signal due to its greater hydrogen content and longer T2* relaxation times. These distinct T1 and T2* characteristics enable UTE-MRI to effectively distinguish dentin from filling materials, providing high-resolution imaging that can assess root canal anatomy, material interfaces, and detect potential degradation or recurrent caries—something conventional MRI cannot achieve [

51].

Dental Pulp and Vitality status of tooth:

Dental MRI is gaining recognition as a non-invasive and radiation-free tool for assessing pulp vitality and perfusion, especially in situations where standard diagnostic methods like thermal or electric tests provide inconclusive results. Traditional T₁ and T₂ MRI sequences often fall short in differentiating between vital and non-vital pulps due to similar signal patterns. However, contrast-enhanced T₁-weighted imaging has shown potential in this area. This technique allows for the assessment of pulpal perfusion by tracking changes in signal intensity after contrast administration, with research reporting marked differences in enhancement between vital (82.7%) and non-vital (17.3%) teeth (P = 0.003). In regenerative endodontic treatments, newly formed pulp tissue has been found to exhibit MRI signal characteristics that align with cold test outcomes (r = -0.63, P < 0.05) [

52,

53]. Additionally, 3T MRI has proven effective in visualizing blood flow restoration in pediatric dental trauma, potentially preventing unnecessary endodontic therapy [

54].

Advanced MRI sequences such as ZTE, UTE, and SWIFT have significantly enhanced the ability to visualize the internal structure and condition of the dental pulp. Notably, 3D ZTE MRI conducted at ultra-high magnetic field strengths (e.g., 9.4 Tesla) has shown promise in distinguishing between intact and damaged pulp tissue in ex vivo models, with contrast variations corresponding to areas of pulpal degeneration, as demonstrated in equine studies (Hövener et al., 2012). Although these imaging methods do not directly assess vascular perfusion, they are highly effective in revealing morphological changes such as calcification, resorption, or structural compromise of the pulp chamber [

3].

Periapical Inflammatory Disease:

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has proven to be highly effective in differentiating periapical cysts from granulomas and in monitoring their healing process after treatment. In their 2023 study, Wamasing et al. identified several key MRI features for distinguishing these lesions, including lesion size (with cysts typically measuring 15.9 mm or larger), margin clarity (well-defined in cysts and ill-defined in granulomas), and peripheral rim thickness (thin in cysts and thick in granulomas). These findings are consistent with the work of Juerchott et al. in 2018, who outlined six important MRI criteria, such as the texture of the peripheral rim (homogeneous in cysts versus heterogeneous in granulomas) and the signal characteristics of the lesion center on T2-weighted fat-saturated sequences (uniform in cysts, variable in granulomas). For post-treatment monitoring, MRI is valuable for assessing healing, with key indicators including reduced T2 hyperintensity (signifying edema resolution) and normalized bone marrow T1 signal intensity (reflecting osseous repair), as reported by Wamasing et al. Additionally, persistent contrast enhancement or the presence of recurrent fluid-filled cavities may indicate incomplete healing or recurrence of the lesion. [

55,

56]. However, despite the growing interest in advanced sequences such as SWIFT, UTE, and ZTE MRI, there remains a lack of clinical studies specifically evaluating their role in the diagnosis and monitoring of periapical lesions.

Periodontal Assessment

A recent technical report demonstrated the potential of a dental-dedicated magnetic resonance imaging (ddMRI) system for non-invasive periodontal assessment. This imaging modality effectively depicted changes in marginal bone levels, offering important information about the progression of periodontal disease and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. The ddMRI system also identified advanced periodontal involvement, such as furcation defects marked by bone loss between tooth roots. Beyond anatomical visualization, the ddMRI sequences detected signal changes consistent with fluid accumulation in the periodontal tissues, which may indicate ongoing inflammation. These observations highlight the supplementary role of ddMRI in clinical evaluations, particularly in identifying both structural alterations and signs of active inflammatory processes in periodontal conditions [

43].

Cracks and Fracture Detection in the Teeth:

Cracks in teeth often present a diagnostic challenge. While CBCT enhances the detection of these cracks, assessing their proximity to dental restorations remains difficult due to artifacts. In teeth with crowns, these artifacts can obscure both the crown and the crack in CBCT images. An ex vivo study involving extracted teeth compared CBCT with SWIFT and GRE protocols, utilizing intraoral coils and MicroCT as a reference. The authors found that SWIFT MRI could detect cracks as narrow as 20 micrometers, which is more than ten times smaller than the image voxel size. They also noted that MR images are less influenced by metal restorations like amalgam and gold, resulting in fewer artifacts than those seen in CBCT. The authors attributed this advantage to the presence of water in the crack, which serves as a negative contrast, and the differences in transverse relaxation times compared to motion-restricted mineralized tissues like dentin. Since the T2 relaxation time of water is in the submillisecond range, cracks are not clearly visible in GRE images obtained under similar conditions [

57]. The presence of artifacts in filled teeth makes it difficult to detect cracks in CBCT images. In vitro studies have demonstrated that UTE sequences can successfully identify dentin cracks in endodontically treated teeth [

51]. Similar to cracks, presence of artifacts due to restorative materials pose a challenge to diagnose root fractures and verical root fractures(VRF). In vitro studies assessing root fractures and VRFs using MRI have shown comparable specificity and sensitivity to those obtained with small field-of-view (FOV) cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) [

58,

59], Notably, studies utilizing SWIFT MRI sequences have successfully detected VRFs with widths ranging from 26 to 64 µm [

60].

Nerve Detection:

In cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), visualization of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) often relies on indirect assessment through the cortical boundaries of the mandibular canal. However, in individuals with conditions such as osteopenia, reduced bone mineral density, or osseous pathology like osteolytic lesions, these cortices may undergo resorption or disruption, compromising the reliability of nerve tracing. In contrast, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows for direct visualization of the IAN and lingual nerve, independent of surrounding bone [

61]. High-resolution MRI sequences such as 3D double-echo steady-state (DESS) and short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) offer excellent soft-tissue contrast for imaging neurovascular structures within the mandible. Research indicates that DESS sequences are particularly effective in visualizing the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle and peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve, benefiting from high signal-to-noise ratios and minimal susceptibility to dephasing artifacts. Additionally, SPACE-STIR sequences enhance nerve visualization by suppressing fat signals, thereby improving contrast in regions affected by magnetic field variations from dental appliances [

62],. In a technical report focused on ddMRI, the authors noted that, in addition to clear depiction of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), the images also successfully demonstrated the lingual nerve [

43].

Alveolar Bone Evaluation for Implant Treatment Planning:

Accurate measurements of the implant site are crucial for effective implant planning. CBCT is the preferred method for obtaining bone measurements prior to implant placement. The ZTE sequences were assessed for their capability to evaluate bone height, width, and area at the implant site. Research conducted on human cadavers showed that bone height measurements were nearly equivalent to those obtained from CBCT. However, ZTE MRI slightly underestimated bone width and area at the implant site. In another similar study, measurements of alveolar bone height and width in ZTE MR images were found to be comparable to those from CBCT [

63].

Jaw Bone Pathology:

While evaluating both odontogenic and non-odontogenic jaw lesions, short TE sequences, like ZTE, can yield information comparable to computed tomography (CT) for assessing the periphery, internal structure, and the impact of the lesion on adjacent anatomical structures. When these sequences are combined with other MRI sequences, tissue characterization can be achieved, revealing further details such as the presence of minerals in the internal matrix in the case of calcified cysts or tumors and detect fluid-blood levels in tumors like aneurysmal bone cysts. Moreover, the reduced imaging time enhances the practicality of these sequences for use in neonates and pediatric patients, aiding in the detection of bone abnormalities and vascular malformations [

64].

Similarly, in the evaluation of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), UTE sequences have been explored for their diagnostic utility in comparison with CBCT. The qualitative assessment analyzed characteristics such as osteolysis, periosteal thickening, and osteosclerosis. A significant correlation was observed between the two modalities across both qualitative and quantitative parameters. However, the presence of air in the vestibule close to the bone appeared similarly dark to the bone in UTE MR sequences, which posed a challenge. Adequate instructions and rinsing mouth prior to the scan might minimize these artifacts [

65]

Temporomandibular Joint(TMJ):

MRI is the preferred method for assessing internal derangements of the TMJ. MRI provides valuable insights into disc position, morphological changes of the disc, joint effusion, and some signs of degenerative joint disease. Additionally, it can reveal alterations in surrounding soft tissues and muscles. Over the years, various MRI techniques have been developed to explore biochemical and structural changes near the joint that occur before visible morphological changes.

The application of short sequences, such as UTE, has improved the visualization of structures with short T2, including the fibrocartilaginous disc and the fibrocartilage lining the joint's articular surfaces. Studies have indicated that the mean UTE T2 in symptomatic individuals is higher than in asymptomatic individuals. Further research is necessary to clarify the potential role of these sequences in evaluating TMJ pathology [

66]. ZTE sequences have demonstrated encouraging outcomes when compared to CBCT in assessing degenerative changes in the joint, including flattening, sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and remodeling alterations in the fossa. However, there is a lack of sufficient data to confirm these results [

67].

Potential Uses in Oral Cancer

The sequences such as ZTE and UTE are FDA-approved for clinical use and can be utilized at various magnetic field strengths. It is advisable to use surface coils positioned directly over the area of interest. MRI, with its superior contrast resolution, effectively highlights tumor margins and surrounding tissues, including muscle, fascia, and perineural fat. Typically, CT imaging is conducted alongside MRI to assess bone involvement. Integrating ZTE sequences eliminates the necessity for extra CT scans, facilitating accurate evaluation and tumor staging. Another significant benefit of ZTE is its capability to evaluate postoperative complications due to reduced hardware-related artifacts [

64]. A study conducted on oral cancer patients assessed the effectiveness of PET/CT and PET/MRI with ZTE-based attenuation correction (ZTE-AC). The ZTE-AC maps accurately defined the jaw bones, and the impact of metal artifacts from dentures was minimal [

68].

MR based Panoramic Reconstruction:

Panoramic imaging is a two-dimensional X-ray technique utilized as a screening tool that provides a comprehensive assessment of the dentoalveolar region. A typical digital panoramic image captured with a charge couple device (CCD) exposes the patient to a radiation dose ranging from 14 to 24 microsieverts [

69]. In a pilot study aimed at producing panoramic reformats from UTE MRI, researchers employed a 3T scanner and a 15-channel mandibular coil, experimenting with various sequences in patients undergoing third molar extraction. The UTE-based sequences demonstrated superior performance in evaluating spatial relationships and root morphology, with excellent image quality and reduced susceptibility artifacts [

70]. In a prior study utilizing a comparable magnetic field strength, the implementation of UTE sequences along with a 64-channel head coil produced high-resolution neurographic panoramic images. This approach enabled the assessment of both osseous texture and neural architecture within a single imaging modality.

MR Based Lateral Cephalometric Reconstruction and Cephalometric Analysis:

Lateral cephalograms (LC) are frequently utilized in orthodontics for conducting cephalometric analysis. Various types of analyses rely on identifying specific osseous anatomical landmarks. A standard lateral cephalometric image subjects the patient to a radiation dose of 5-6 microsieverts. The majority of patients receiving orthodontic treatment are typically in their growth phase, making them ideal candidates for non-ionizing radiation based imaging techniques. In the realm of medical MRI, some researchers have experimented with adjustments to the GRE scan protocol. They reduced the flip angle and also decreased both the repetition time (TR) and echo time (TE). This imaging technique, referred to as "black bone" MRI, enhanced the contrast between bone and soft tissue in MR images [

71]. In another study, the authors modified a similar protocol to create 2D midsagittal planes and compared these with traditional LC, T1, and T2 sequences. A limitation of this study is that anatomical information from the paramedian planes was not accessible. A subsequent effort was undertaken to gather data from median and paramedian slices by incorporating UTE sequences, which further minimized TR and TE. While the MR-generated LC successfully identified various anatomical landmarks, the Traditional LC outperformed it. The authors attributed this difference to lower resolution, increased noise in the scans, and insufficient training in interpreting these novel images [

72].

Assessment of Craniocervical Junction:

To assess alterations in the craniocervical junction (CCJ), CT remains the preferred imaging method. Recent advancements in bone visualization, due to the development of specialized sequences, have led some studies to explore the efficacy of shorter sequences for evaluating the CCJ. UTE demonstrated a high level of agreement for specific distance measurements when compared to CT. Given these findings, UTE is suggested as a viable alternative to CT [

73].

Applications in Forensic Dentistry:

The formation of secondary dentin in teeth has been utilized as a parameter for estimating age. One key measurement is the reduction in the size of the pulp cavity observed through imaging. Research demonstrated that UTE sequences at high magnetic field strengths (9.4T) effectively distinguish between tooth structure and pulp in extracted teeth, achieving an in-plane resolution of 66 μm³. Using these tooth-to-pulp volume ratios, calculations can be made that aid in age estimation [

74]. In a separate study, the authors compared measurements with CBCT, noting slight variations; specifically, the pulp volume appeared smaller on MRI. They concluded that method-specific reference values are essential for practical age assessment [

75].

In the majority of the aforementioned applications, short sequences demonstrated potential comparable to ionizing radiation-based modalities. However, most studies are based on in vitro, ex vivo, and cadaveric research. Studies involving human subjects typically had small sample sizes. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to validate these findings.

10. Discussion

The first NMR image was created by Lauterbur in 1973. Since that time, the field has experienced remarkable progress. While MRI scans of the head and neck can reveal the teeth and dentoalveolar region, medical MRI systems have not been adopted in routine dental practice due to inadequate visualization of mineralized tissues. Furthermore, several obstacles, such as space constraints in dental operatories, cost, and technological challenges, have hindered its implementation in dentistry. However, advancements in hardware, including the development of light-magnet technology and built-in automation, and the refinement of short sequences have made MRI more accessible to dentistry, similar to x-ray-based imaging.

Numerous efforts have been made to enhance the visualization of dentoalveolar structures. These efforts focus on the use of contrast agents, high field strengths, the development of specialized surface coils, and the enhancement of imaging sequences. A study conducted in 2004, investigated different contrast agents by filling patient’s mouths with biocompatible materials. The authors noted that some of these contrast materials improved the visibility of anatomical structures while reducing susceptibility artifacts. Furthermore, they indicated that the spatial resolution of contrast-enhanced dental MRI is on par with that of CT scans [

15].

Magnetic field strength is measured in Tesla (T), with most systems utilized in clinical settings falling between 1.5 and 4T. Units operating at 3-7T are classified as high Tesla. Numerous previous studies indicate that 3T MRI scanners provide enhanced visualization of dental structures [

44,

76,

77].

The heightened magnetic field strength increases the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and enhances image resolution. However, with higher field strengths, there is a decrease in T2 relaxation time and an increase in susceptibility artifacts that may hinder in vivo resolution. New generation scanners now focus on imaging teeth at low field strengths such as 0.55T, placement of surface coils and ultra short echo time sequences [

43,

78,

79].

Traditionally, MRI scans of the gnathic region are conducted using head and neck coils. These coils with their large FOV and limited gradient strength compromised the image resolution, making them less effective for examining teeth and endodontic structures. In recent years, specialized MRI coils for dentistry have been developed. These include both extraoral surface coils and intraoral coils. These advancements minimize the FOV and have shown encouraging results for imaging teeth and surrounding structures [

43,

54,

80]. Research indicates that using intraoral coil placement enhances image resolution; however, this approach has its drawbacks. It can interfere with anatomical structures and presents challenges in coil placement, often resulting in difficulties capturing distal areas, root apices, and periapical regions [

81]. Studies showed significant improvement in SNR with surface coils positioned directly on the face and mandible [

82].

As previously discussed, specific types of sequences with short T2 values eliminate the signal void caused by mineralized tissues that have high dipole-dipole interaction. In vitro studies utilizing such sequences demonstrated the ability to accurately evaluate the level of demineralization and identify occlusal and recurrent caries, as well as cracks within the tooth [

41].

Advanced MRI sequences such as UTE and ZTE provide innovative alternatives to conventional CT and other dental imaging techniques. These sequences enable simultaneous visualization of both soft and hard tissues, allowing clear differentiation of dental structures, including enamel, dentin, cementum, and pulp. At higher magnetic field strengths, such as 7T, they enhance image contrast and resolution beyond what is achievable with standard MRI and CBCT.

ZTE MRI has shown high accuracy in depicting solid dental structures, closely matching actual tooth surfaces. It effectively distinguishes between healthy and diseased pulp regions and can visualize materials like calcium phosphate-based pulp capping and glass ionomer restorations, which are typically challenging to detect using conventional MRI.

Unlike traditional UTE sequences, the SWIFT technique utilizes swept RF excitation and simultaneous signal acquisition while maintaining field gradients. This method allows imaging of ultrashort T2 components with minimal strain on MR hardware, making it particularly effective for capturing calcified dental tissues. Additionally, SWIFT excels in identifying accessory canals in the apical third of the root, offering superior diagnostic capabilities in endodontics compared to CBCT [

83].

In a recent study, the authors utilized a scanner developed specifically for dentistry. The machine operates at a magnetic field strength of 0.55T, equipped with a dental surface coil positioned on the face. This setup minimizes the FOV and they used very short pulse sequences. Preliminary findings from the report indicate a diverse array of applications in orthodontics, including the generation of 2D lateral cephalograms to identify cephalometric points for analysis, panoramic reconstructions akin to CBCT, detection of carious tooth, fractures in crowns and roots, and endodontic evaluations of root canals and periapical tissues. Furthermore, it demonstrates its value in assessing periodontal hard and soft tissues [

43].

11. Conclusions

This paper outlines critical developments supporting the integration of MRI into dental diagnostics, marking a shift toward high-resolution, radiation-free imaging. Advances in magnetic field optimization, intraoral and surface coil design, and short T2 sequences (UTE, ZTE, SWIFT) have significantly improved the ability to visualize both hard and soft tissues with clinically feasible scan times and high diagnostic accuracy. Dental-specific MRI systems now address the anatomical and technical challenges of the dentoalveolar region, enhancing image quality and reducing artifacts. These improvements are expanding MRI’s potential applications in dental diagnostics, particularly in areas requiring simultaneous assessment of hard and soft tissues—where conventional imaging may offer limited information.

The absence of ionizing radiation enables safe, repeat imaging—especially advantageous for pediatric patients and individuals requiring longitudinal follow-up. Future work should focus on protocol optimization, artifact reduction, and hardware improvements to support broader clinical implementation. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to advance dental MRI from research to routine practice. In conclusion, the integration of advanced MRI technology into dental imaging holds promise for redefining diagnostic approaches, offering a non-invasive, comprehensive alternative that supports improved patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Sonam Khurana; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: Sonam Khurana, Pranav Parasher, Anusha Vaddi; Writing – Review & Editing: Anusha Vaddi, Pranav Parasher, Sonam Khurana; Literature Review: Pranav Parasher, Sonam Khurana, Anusha Vaddi; Introduction: Pranav Parasher, Sonam Khurana; Sequences, coils design: Sonam Khurana; Potential Applications of Sequences: Anusha Vaddi, Sonam Khurana; Discussion: Pranav Parasher, Anusha Vaddi

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Qingyu Meng (NYU Dentistry Class of 2026) for his illustration. For inquiries, he can be reached at qm316@nyu.edu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBCT |

Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| UTE |

Ultrashort Echo Time |

| ZTE |

Zero Echo Time |

| SWIFT |

Sweep Imaging with Fourier Transformation |

| TMJ |

Temporomandibular Joint |

| RF |

Radiofrequency |

| FID |

Free Induction Decay |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| IGM |

Imaging -Based Gradient Measurements |

| GIRF |

Gradient Impulse Response Function |

| RHE |

Ramped Hybrid Encoding |

| TE |

Echo Time |

| FT |

Fourier Transform |

| PETRA |

Pointwise Encoding Time Reduction with Radial Acquisition |

| SAR |

Specific Absorption Rate |

| NMR |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| CW |

continuous wave |

| FOV |

Field of View |

| tLoop |

transverse loop coil |

| mtLoop |

modified transverse loop coil |

| FUTE |

Fat-Suppressed UTE |

| GRE |

Gradient Echo Images |

| IAN |

Inferior Alveolar Nerve |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| MRONJ |

Medication -Related Osteonecrosis of Jaws |

| CCD |

Charge Couple Device |

| LC |

Lateral cephalogram |

| TR |

Repition Time |

| CCJ |

Craniocervical Junction |

References

- Sedentexct Radiation Protection N°172 – Cone Beam Ct For Dental And Maxillofacial Radiology – Evidence-Based Guidelines | cbct-Xchange [Internet]. Available online: https://www.cbct-xchange.com/document/sedentexct-radiation-protection-n172-cone-beam-ct-for-dental-and-maxillofacial-radiology-evidence-based-guidelines/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Jacobs R, Salmon B, Codari M, Hassan B, Bornstein MM. Cone beam computed tomography in implant dentistry: recommendations for clinical use. BMC Oral Health. 2018 May 15;18(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Hövener JB, Zwick S, Leupold J, Eisenbeiβ AK, Scheifele C, Schellenberger F, et al. Dental MRI: imaging of soft and solid components without ionizing radiation. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2012 Oct;36(4):841–6. [CrossRef]

- Probst M, Burian E, Robl T, Weidlich D, Karampinos D, Brunner T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic tool for periodontal disease: A prospective study with correlation to standard clinical findings-Is there added value? J Clin Periodontol. 2021 Jul;48(7):929–48. [CrossRef]

- Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: Part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2009;42(6):463–75. [CrossRef]

- Bromberg N, Brizuela M. Dental Cone Beam Computed Tomography. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592390/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Nakamura T. Dental MRI: a road beyond CBCT. Eur Radiol. 2020 Dec;30(12):6389–91. [CrossRef]

- Niraj LK, Patthi B, Singla A, Gupta R, Ali I, Dhama K, et al. MRI in Dentistry- A Future Towards Radiation Free Imaging - Systematic Review. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2016 Oct;10(10):ZE14–9. [CrossRef]

- Stratis A, Zhang G, Jacobs R, Bogaerts R, Bosmans H. The growing concern of radiation dose in paediatric dental and maxillofacial CBCT: an easy guide for daily practice. Eur Radiol. 2019 Dec;29(12):7009–18. [CrossRef]

- Pauwels R, Cockmartin L, Ivanauskaité D, Urbonienė A, Gavala S, Donta C, et al. Estimating cancer risk from dental cone-beam CT exposures based on skin dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2014 Jul 21;59(14):3877–91. [CrossRef]

- Juerchott A, Roser CJ, Saleem MA, Nittka M, Lux CJ, Heiland S, et al. Diagnostic compatibility of various fixed orthodontic retainers for head/neck MRI and dental MRI. Clin Oral Investig. 2023 May;27(5):2375–84. [CrossRef]

- Pasteris JD, Wopenka B, Valsami-Jones E. Bone and Tooth Mineralization: Why Apatite? Elements. 2008 Apr 1;4(2):97–104. [CrossRef]

- Schreiner LJ, Cameron IG, Funduk N, Miljković L, Pintar MM, Kydon DN. Proton NMR spin grouping and exchange in dentin. Biophys J. 1991 Mar;59(3):629–39. [CrossRef]

- Funduk N, Kydon DW, Schreiner LJ, Peemoeller H, Miljković L, Pintar MM. Composition and relaxation of the proton magnetization of human enamel and its contribution to the tooth NMR image. Magn Reson Med. 1984 Mar;1(1):66–75. [CrossRef]

- Olt S, Jakob PM. Contrast-enhanced dental MRI for visualization of the teeth and jaw. Magn Reson Med. 2004 Jul;52(1):174–6. [CrossRef]

- Węglarz WP, Tanasiewicz M, Kupka T, Skórka T, Sułek Z, Jasiński A. 3D MR imaging of dental cavities—an in vitro study. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2004 Jan 1;25(1):84–7. [CrossRef]

- Tymofiyeva O, Rottner K, Gareis D, Boldt J, Schmid F, Lopez M a., et al. In vivo MRI-based dental impression using an intraoral RF receiver coil. Concepts Magn Reson Part B Magn Reson Eng. 2008;33B(4):244–51. [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiacomo S, Dou W, Jansen JA, Walboomers XF. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Hard Tissues and Hard Tissue Engineered Bio-substitutes. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019 Dec;21(6):1003–19. [CrossRef]

- Robson MD, Bydder GM. Clinical ultrashort echo time imaging of bone and other connective tissues. NMR Biomed. 2006 Nov;19(7):765–80. [CrossRef]

- Bydder GM. The Agfa Mayneord lecture: MRI of short and ultrashort T2 and T2* components of tissues, fluids and materials using clinical systems. Br J Radiol. 2011 Dec;84(1008):1067–82. [CrossRef]

- Chang EY, Du J, Chung CB. UTE imaging in the musculoskeletal system. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2015 Apr;41(4):870–83. [CrossRef]

- Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27(6):825–46. [CrossRef]

- Tyler DJ, Robson MD, Henkelman RM, Young IR, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance imaging with ultrashort TE (UTE) PULSE sequences: technical considerations. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2007 Feb;25(2):279–89. [CrossRef]

- Brodsky EK, Samsonov AA, Block WF. Characterizing and Correcting Gradient Errors in Non-Cartesian Imaging: Are Gradient Errors Linear-Time-Invariant? Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2009 Dec;62(6):1466–76. [CrossRef]

- Bartusek K, Kubasek R, Fiala P. Determination of pre-emphasis constants for eddy current reduction. Meas Sci Technol. 2010 Aug;21(10):105601. [CrossRef]

- Addy NO, Wu HH, Nishimura DG. Simple method for MR gradient system characterization and k-space trajectory estimation. Magn Reson Med. 2012 Jul;68(1):120–9. [CrossRef]

- Vannesjo SJ, Haeberlin M, Kasper L, Pavan M, Wilm BJ, Barmet C, et al. Gradient system characterization by impulse response measurements with a dynamic field camera. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(2):583–93. [CrossRef]

- Jang H, Wiens CN, McMillan AB. Ramped hybrid encoding for improved ultrashort echo time imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2016 Sep;76(3):814–25. [CrossRef]

- Jang H, McMillan AB. A rapid and robust gradient measurement technique using dynamic single-point imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2017 Sep;78(3):950–62. [CrossRef]

- Weiger M, Pruessmann KP. MRI with zero echo time. In: Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, editors. Weiger, M; Pruessmann, K P (2012) MRI with zero echo time In: Harris, R K; Wasylishen, R E Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance Chichester: John Wiley, 311-321 [Internet]. Chichester: John Wiley; 2012 [cited 2025 Apr 2]. p. 311–21. Available online: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/73614/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Weiger M, Pruessmann KP, Hennel F. MRI with zero echo time: hard versus sweep pulse excitation. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Aug;66(2):379–89. [CrossRef]

- Grodzki DM, Jakob PM, Heismann B. Ultrashort echo time imaging using pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA). Magn Reson Med. 2012 Feb;67(2):510–8. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Magland JF, Seifert AC, Wehrli FW. Correction of excitation profile in Zero Echo Time (ZTE) imaging using quadratic phase-modulated RF pulse excitation and iterative reconstruction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2014 Apr;33(4):961–9. [CrossRef]

- Lee YH, Suh JS, Grodzki D. Ultrashort echo (UTE) versus pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA) sequences at 3 Tesla for knee meniscus: A comparative study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2016 Feb;34(2):75–80. [CrossRef]

- Schieban K, Weiger M, Hennel F, Boss A, Pruessmann KP. ZTE imaging with enhanced flip angle using modulated excitation. Magn Reson Med. 2015 Sep;74(3):684–93. [CrossRef]

- Weiger M, Wu M, Wurnig MC, Kenkel D, Boss A, Andreisek G, et al. ZTE imaging with long-T2 suppression. NMR Biomed. 2015 Feb;28(2):247–54. [CrossRef]

- Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Park JY, Garwood M. Fast and quiet MRI using a swept radiofrequency. J Magn Reson San Diego Calif 1997. 2006 Aug;181(2):342–9. [CrossRef]

- Idiyatullin D, Suddarth S, Corum CA, Adriany G, Garwood M. Continuous SWIFT. J Magn Reson San Diego Calif 1997. 2012 Jul;220:26–31. [CrossRef]

- Prager M, Heiland S, Gareis D, Hilgenfeld T, Bendszus M, Gaudino C. Dental MRI using a dedicated RF-coil at 3 Tesla. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2015 Dec;43(10):2175–82. [CrossRef]

- Gruber B, Froeling M, Leiner T, Klomp DWJ. RF coils: A practical guide for nonphysicists. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2018 Jun 13;48(3):590–604. [CrossRef]

- Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Moeller S, Prasad HS, Garwood M, Nixdorf DR. Dental magnetic resonance imaging: making the invisible visible. J Endod. 2011 Jun;37(6):745–52. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig U, Eisenbeiss AK, Scheifele C, Nelson K, Bock M, Hennig J, et al. Dental MRI using wireless intraoral coils. Sci Rep. 2016 Mar 29;6(1):23301. [CrossRef]

- Greiser A, Christensen J, Fuglsig JMCS, Johannsen KM, Nixdorf DR, Burzan K, et al. Dental-dedicated MRI, a novel approach for dentomaxillofacial diagnostic imaging: technical specifications and feasibility. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2024 Jan 11;53(1):74–85. [CrossRef]

- Özen AC, Ilbey S, Jia F, Idiyatullin D, Garwood M, Nixdorf DR, et al. An improved intraoral transverse loop coil design for high-resolution dental MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2023;90(4):1728–37. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Bhosale AA, Zhang X. Coupled stack-up volume RF coils for low-field open MR imaging [Internet]. medRxiv; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 2]. p. 2024.08.30.24312851. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.08.30.24312851v1 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Flügge T, Gross C, Ludwig U, Schmitz J, Nahles S, Heiland M, et al. Dental MRI-only a future vision or standard of care? A literature review on current indications and applications of MRI in dentistry. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2023 Apr;52(4):20220333. [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse PD, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance imaging of short T2 components in tissue. Clin Radiol. 2003 Jan;58(1):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bracher AK, Hofmann C, Bornstedt A, Boujraf S, Hell E, Ulrici J, et al. Feasibility of ultra-short echo time (UTE) magnetic resonance imaging for identification of carious lesions. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Aug;66(2):538–45. [CrossRef]

- Bracher AK, Hofmann C, Bornstedt A, Hell E, Janke F, Ulrici J, et al. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI for the assessment of caries lesions. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2013;42(6):20120321. [CrossRef]

- Grosse U, Syha R, Papanikolaou D, Martirosian P, Grözinger G, Schabel C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of solid dental restoration materials using 3D UTE sequences: visualization and relaxometry of various compounds. Magma N Y N. 2013 Dec;26(6):555–64. [CrossRef]

- Timme M, Masthoff M, Nagelmann N, Masthoff M, Faber C, Bürklein S. Imaging of root canal treatment using ultra high field 9.4T UTE-MRI - a preliminary study. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2020 Jan;49(1):20190183. [CrossRef]

- Kress B, Buhl Y, Anders L, Stippich C, Palm F, Bähren W, et al. Quantitative analysis of MRI signal intensity as a tool for evaluating tooth pulp vitality. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2004 Jul;33(4):241–4. [CrossRef]

- Juerchott A, Jelinek C, Kronsteiner D, Jende JME, Kurz FT, Bendszus M, et al. Quantitative assessment of contrast-enhancement patterns of the healthy dental pulp by magnetic resonance imaging: A prospective in vivo study. Int Endod J. 2022 Mar;55(3):252–62. [CrossRef]

- Assaf AT, Zrnc TA, Remus CC, Khokale A, Habermann CR, Schulze D, et al. Early detection of pulp necrosis and dental vitality after traumatic dental injuries in children and adolescents by 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2015 Sep;43(7):1088–93. [CrossRef]

- Wamasing, N.; Yomtako, S.; Watanabe, H.; Sakamoto, J.; Kayamori, K.; Kurabayashi, T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics of Radicular Cysts and Granulomas. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2023, 52, 20220336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juerchott A, Pfefferle T, Flechtenmacher C, Mente J, Bendszus M, Heiland S, et al. Differentiation of periapical granulomas and cysts by using dental MRI: a pilot study. Int J Oral Sci. 2018 May 17;10(2):17. [CrossRef]

- Idiyatullin D, Garwood M, Gaalaas L, Nixdorf DR. Role of MRI for detecting micro cracks in teeth. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 45(7):20160150. [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans TJ, Nixdorf DR, Idiyatullin DS, Law AS, Barsness BD, Roach SH, et al. Accuracy and Reliability of Root Crack and Fracture Detection in Teeth Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Endod. 2019 Jun;45(6):750-755.e2. [CrossRef]

- Groenke BR, Idiyatullin D, Gaalaas L, Petersen A, Law A, Barsness B, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of MRI versus CBCT to Detect Vertical Root Fractures Using MicroCT as a Reference Standard. J Endod. 2023 Jun;49(6):703–9. [CrossRef]

- Groenke BR, Idiyatullin D, Gaalaas L, Petersen A, Chew HP, Law A, et al. Minimal Detectable Width of Tooth Fractures Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Method to Measure. J Endod. 2022 Nov;48(11):1414-1420.e1. [CrossRef]

- Burian E, Sollmann N, Ritschl LM, Palla B, Maier L, Zimmer C, et al. High resolution MRI for quantitative assessment of inferior alveolar nerve impairment in course of mandible fractures: an imaging feasibility study. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 14;10(1):11566. [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain, A., Schmidt, V., Valdec, S. et al. MR-orthopantomography in operative dentistry and oral and maxillofacial surgery: a proof of concept study. Sci Rep 13, 6228 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Fuglsig JM de CES, Hansen B, Schropp L, Nixdorf DR, Wenzel A, Spin-Neto R. Alveolar bone measurements in magnetic resonance imaging compared with cone beam computed tomography: a pilot, ex-vivo study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2023 Apr;81(3):241–8. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Bambach S, Selvaraj B, Ho ML. Zero-TE MRI: Potential Applications in the Oral Cavity and Oropharynx. Top Magn Reson Imaging TMRI. 2021 Apr 1;30(2):105–15. [CrossRef]

- Huber FA, Schumann P, von Spiczak J, Wurnig MC, Klarhöfer M, Finkenstaedt T, et al. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw-Comparison of Bone Imaging Using Ultrashort Echo-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Invest Radiol. 2020 Mar;55(3):160–7. [CrossRef]

- Bae WC, Tafur M, Chang EY, Du J, Biswas R, Kwack KS, et al. High-resolution morphologic and ultrashort time-to-echo quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the temporomandibular joint. Skeletal Radiol. 2016 Mar;45(3):383–91. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Jeon KJ, Han SS, Kim YH, Choi YJ, Lee A, et al. CT-like MRI using the zero-TE technique for osseous changes of the TMJ. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2020 Mar;49(3):20190272. [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa T, Kanno M, Ito Y, Oikawa H, Rahman MGM, Narita N, et al. Zero Echo Time-Based PET/MRI Attenuation Correction in Patients With Oral Cavity Cancer: Initial Experience. Clin Nucl Med. 2020 Jul;45(7):501–5. [CrossRef]

- Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, White SC. Patient Risk Related to Common Dental Radiographic Examinations: The Impact of 2007 International Commission on Radiological Protection Recommendations Regarding Dose Calculation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Sep 1;139(9):1237–43. [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain A, Oechslin DA, Stadlinger B, Winklhofer S, Özcan M, Schönegg D, et al. Preoperative imaging in third molar surgery - A prospective comparison of X-ray-based and radiation-free magnetic resonance orthopantomography. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2024 Jan;52(1):117–26. [CrossRef]

- Eley KA, McIntyre AG, Watt-Smith SR, Golding SJ. “Black bone” MRI: a partial flip angle technique for radiation reduction in craniofacial imaging. Br J Radiol. 2012 Mar;85(1011):272–8. [CrossRef]

- Abkai C, Hourfar J, Glockengießer J, Ulrici J, Hell E, Rasche V, et al. Ultra short time to Echo (UTE) MRI for cephalometric analysis-Potential of an x-ray free fast cephalometric projection technique. PloS One. 2021;16(9):e0257224. [CrossRef]

- Deininger-Czermak E, Villefort C, von Knebel Doeberitz N, Franckenberg S, Kälin P, Kenkel D, et al. Comparison of MR Ultrashort Echo Time and Optimized 3D-Multiecho In-Phase Sequence to Computed Tomography for Assessment of the Osseous Craniocervical Junction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53(4):1029–39. [CrossRef]

- Timme M, Borkert J, Nagelmann N, Schmeling A. Evaluation of secondary dentin formation for forensic age assessment by means of semi-automatic segmented ultrahigh field 9.4 T UTE MRI datasets. Int J Legal Med. 2020 Nov;134(6):2283–8. [CrossRef]

- Timme M, Borkert J, Nagelmann N, Streeter A, Karch A, Schmeling A. Age-dependent decrease in dental pulp cavity volume as a feature for age assessment: a comparative in vitro study using 9.4-T UTE-MRI and CBCT 3D imaging. Int J Legal Med. 2021 Jul;135(4):1599–609. [CrossRef]

- Allison JR, Chary K, Ottley C, Vuong QC, German MJ, Durham J, et al. The effect of magnetic resonance imaging on mercury release from dental amalgam at 3T and 7T. J Dent. 2022 Dec;127:104322. [CrossRef]

- Kotaki S, Watanabe H, Sakamoto J, Kuribayashi A, Araragi M, Akiyama H, et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of teeth and periodontal tissues using a microscopy coil. Imaging Sci Dent. 2024 Sep;54(3):276–82. [CrossRef]

- Algarín JM, Díaz-Caballero E, Borreguero J, Galve F, Grau-Ruiz D, Rigla JP, et al. Simultaneous imaging of hard and soft biological tissues in a low-field dental MRI scanner. Sci Rep. 2020 Dec 8;10(1):21470. [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo G, Soltani P. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Digital Dentistry: The Start of a New Era. Prosthesis. 2024 Aug;6(4):798–802. [CrossRef]

- Cankar K, Vidmar J, Nemeth L, Serša I. T2 Mapping as a Tool for Assessment of Dental Pulp Response to Caries Progression: An in vivo MRI Study. Caries Res. 2020;54(1):24–35. [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo D, Gambarini G, Capuani S, Testarelli L. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Endodontics: A Review. J Endod. 2018 Apr;44(4):536–42. [CrossRef]

- Gradl J, Höreth M, Pfefferle T, Prager M, Hilgenfeld T, Gareis D, et al. Application of a Dedicated Surface Coil in Dental MRI Provides Superior Image Quality in Comparison with a Standard Coil. Clin Neuroradiol. 2017 Sep;27(3):371–8. [CrossRef]

- S. More S, Zhang X. Ultrashort Echo Time and Zero Echo Time MRI and Their Applications at High Magnetic Fields: A Literature Survey. Investig Magn Reson Imaging. 2024 Dec 1;28(4):153–73. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).