Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

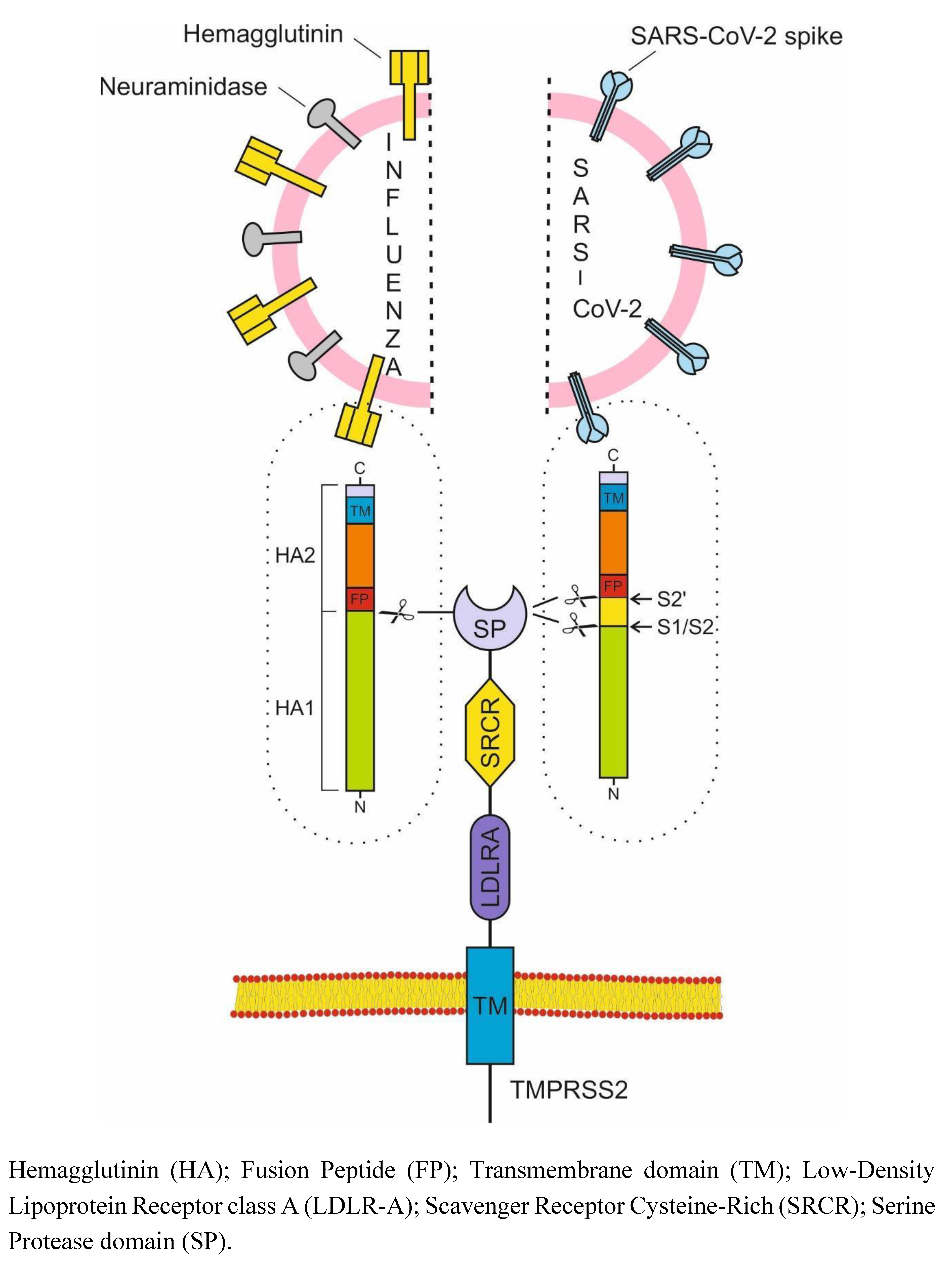

2. TMPRSS2 - main target for the prevention of COVID-19 and influenza

2.1. TMPRSS2

2.2. Role of TMPRSS2 in Influenza and COVID-19 Infections

2.2.1. Influenza

2.2.2. SARS-CoV-2

2.3. Inhibitors of TMPRSS2

2.3.1. Camostat Mesylate

2.3.2. Bromhexine hydrochloride

3. NLRP3 inflammasome - main target for treatment of COVID-19 and influenza

3.1. Structure and distribution of NLRP3 inflammasome

3.2. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome

3.3. Regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome

4. Clinical course of influenza and COVID-19

4.1. FLU

4.2. COVID-19

5. Strategies for dealing with COVID-19 and the flu - which one is the winner?

5.1. Antivirals and inhibitors of individual cytokines

5.2. Inhibition of TMPRSS2 and NLRP3 inflammasome

- 1)

- SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A and B viruses enter the cell mainly through TMPRSS2.

- 2)

- Bromhexine inhibits TMPRSS2.

- 3)

- The effect of BRH is best when taken prophylactically, not after the viruses have already entered the cell.

- 4)

- Post-exposure prophylaxis with BRH is also very effective, especially when done by inhalation.

- 5)

- Complications in both influenza and COVID-19 are due to a NLRP3 inflammasome hyperreaction, which causes a cytokine storm.

- 6)

- Colchicine accumulates in myeloid cells, which explains its NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitory effect at high doses.

- 7)

- Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome prevents cytokine storm and normalizes cytokine levels.

- 8)

- Higher doses of colchicine have been used in the past and are completely safe, provided the rules for administering colchicine are being followed.

- 9)

- With a series of clinical cases, we demonstrated the life-saving effect of high doses of colchicine in critically ill patient [111], those with high levels of obesity [112-114], and the unique case of recovery of a 101-year-old patient infected with COVID-19 in intensive care after major surgery [115]. It is very demonstrative that four patients who mistakenly took more than 12.5 mg of colchicine recovered quickly and completely after discontinuing all therapy [47,116].

- 10)

- Studies on 795 inpatients treated with high doses of colchicine reduced mortality by 2 to 7 times, in direct proportion to increasing doses [117,118]. Outpatients’ high-dose colchicine treatment practically prevents hospitalizations and demonstrates reverse relationship with hospitalization [108]. The maximum loading doses we use of up to 5mg of colchicine (0.045mg/kg) are completely safe [48,57,119].

- 11)

- 12)

- The epidemic situation in Bulgaria for the winter of 2025 is dominated by influenza viruses A(H3N2 and H1N1pdm09) and influenza viruses B/Victoria. We are monitoring several hundred people taking BRH prophylactically. The results will be summarized at the end of the epidemic, but so far none of those taking prophylactic BRH have fallen ill. Our preliminary results were reported at a national conference [121] and published [122].

| Influenza | COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Viruses | Spanish influenza in 1918 (H1N1), Asian influenza in 1957 (H2N2), Hong Kong influenza in 1968 (H3N2), Russian influenza in 1977 (H1N1) | SARS-CoV-2, 2019 |

| Virus family | Orthomyxoviridae | Coronaviridae |

| Viral nucleic acid | Negative sense single-stranded RNA | Positive sense single-stranded RNA |

| Vulnerable contingent |

children and adults H1N1 influenza in 1918 - young people |

adults |

| Incubation period | 2 days | 2-14 days |

| R0 | 1.4-2.8 | 5.7 |

| Tropism | Respiratory tract epithelium | Multiple organs |

| Host receptor | α 2,6 sialic acids | ACE2 |

| Viral proteins required for fusion | HA | S |

| Critical protease | TMPRSS2 | TMPRSS2 |

| First symptom | Cough | Fever |

| Contagiousness |

One day before the onset of symptoms and up to five to seven days after | 48 hours before the onset of symptoms and up to 10 days after |

| Most contagious | The first three days after the onset of symptoms | 1-2 days before the onset of symptoms |

| Viral load peak |

2 day | Early at the onset of symptoms, now in a highly immune adult population - 4 day |

| Worst Days Alert | 7-9 | 8-10 |

| Cause of cytokine storm | NLRP3 hyperactivation | NLRP3 hyperactivation |

| IL-6/ IL-1/ IL-18/ D-Dimer/ Hypercoagulative state/ DIC/ Endotheliopathy / Ferritin/ Activated macrophages/ High neutrophil to Lymphocyte ratio/ Immunothrombosis, LDH | ++/++/+/++/++/++/ +++/++/+/++/ ++/+++ |

+++/+++/+++/++/+++/ ++/+++/++/+++/++/++/+++ |

| Radiological findings | Multilobe consolidations | Ground-glass opacities |

| Need for hospitalization | 5.6% | 20% |

| Need for intubation | 4.8% | 10%–15% |

| Mortality | 0.13%–1.36% | 1.40%–3.67% |

| Prophylaxis | BRH | BRH |

| Рost-exposure prophylaxis | Inhaled BRH | Inhaled BRH |

| Cytokine storm treatment | High colchicine doses | High colchicine doses |

Funding Statement

References

- Johnson NPAS, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: Global mortality of the 1918-1920 “spanish” influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine [Internet]. 2002;76(1):105–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11875246/.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 deaths | WHO COVID-19 dashboard [Internet]. World Health Organization Data. 2024. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths.

- Adam, D. The pandemic’s true death toll: Millions more than official counts. Nature [Internet]. 2022 Jan 18;601(7893):312–5. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00104-8.

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal) [Internet]. Who.int. World Health Organization: WHO; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Di Cera, E. Serine Proteases. IUBMB Life. 2009 May;61(5):510–5.

- Bugge TH, Antalis TM, Wu Q. Type II Transmembrane Serine Proteases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009 Aug;284(35):23177–81.

- Fraser BJ, Beldar S, Seitova A, Hutchinson A, Mannar D, Li Y, et al. Structure and activity of human TMPRSS2 protease implicated in SARS-CoV-2 activation. Nature Chemical Biology [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1;18(9):963–71. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41589-022-01059-7.

- Li X, He L, Luo J, Zheng Y, Zhou Y, Li D, et al. Paeniclostridium sordellii hemorrhagic toxin targets TMPRSS2 to induce colonic epithelial lesions. Nature Communications. 2022 Jul 26;13(1).

- Harbig A, Mernberger M, Bittel L, Pleschka S, Klaus Schughart, Torsten Steinmetzer, et al. Transcriptome profiling and protease inhibition experiments identify proteases that activate H3N2 influenza A and influenza B viruses in murine airways. 2020 Aug 14;295(33):11388–407.

- Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors Are Highly Expressed in Nasal Epithelial Cells Together with Innate Immune Genes. Nature Medicine [Internet]. 2020 May 1;26(5):681–7. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0868-6.

- Donaldson SH, Hirsh A, Li DC, Holloway G, Chao J, Boucher RC, et al. Regulation of the Epithelial Sodium Channel by Serine Proteases in Human Airways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Mar;277(10):8338–45.

- Florian Sure, Marko Bertog, Afonso S, Alexei Diakov, Rinke R, M. Gregor Madej, et al. Transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) proteolytically activates the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by cleaving the channel’s γ-subunit. 2022 Apr 1;298(6):102004–4.

- Kim TS, Heinlein C, Hackman RC, Nelson PS. Phenotypic Analysis of Mice Lacking the Tmprss2-Encoded Protease. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006 Feb 1;26(3):965–75.

- Gasi Tandefelt D, Boormans J, Hermans K, Trapman J. ETS Fusion Genes in Prostate Cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2014 Mar 20;21(3):R143–52.

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hu Q, Zhi F, Zhang S, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG Gene Fusion in Prostate Cancer. Molecular Medicine Reports [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1;16(4):5450–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5647090/.

- Esumi M, Ishibashi M, Yamaguchi H, Nakajima S, Tai Y, Kikuta S, et al. Transmembrane Serine Protease TMPRSS2 Activates Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2015 Jan 20;61(2):437–46.

- Melis M, Diaz G, Kleiner DE, Zamboni F, Kabat J, Lai J, et al. Viral Expression and Molecular Profiling in Liver Tissue versus Microdissected Hepatocytes in Hepatitis B Virus - Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of translational medicine. 2014 Aug 21;12(1).

- Hamamoto Y, Kawamura M, Uchida H, Hiramatsu K, Chiaki Katori, Asai H, et al. Increased ACE2 and TMPRSS2 Expression in Ulcerative Colitis. Pathology - Research and Practice. 2024 Jan 10;254:155108–8.

- Hoang T, Nguyen TQ, Tran TTA. Genetic Susceptibility of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in Six Common Cancers and Possible Impacts on COVID-19. Cancer Research and Treatment. 2020 Dec 29.

- Barros G, Everton Nencioni, Fábio Thimoteo, Perea C, Fuzaro R, Sasaki SD. TMPRSS2 as a Key Player in Viral Pathogenesis: Influenza and Coronaviruses. Biomolecules. 2025 Jan 7;15(1):75–5.

- Zhang N, Fang S, Wang T, Li J, Cheng X, Zhao C, et al. Applicability of a Sensitive Duplex real-time PCR Assay for Identifying B/Yamagata and B/Victoria Lineages of Influenza Virus from Clinical Specimens. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011 Nov 24;93(2):797–805.

- Krammer F, Smith GJD, Fouchier RAM, Peiris M, Kedzierska K, Doherty PC, et al. Influenza. Nature Reviews Disease Primers [Internet]. 2018 Jun 28;4(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7097467/.

- Böttcher-Friebertshäuser E, Garten W, Matrosovich M, Klenk HD. The Hemagglutinin: A Determinant of Pathogenicity. Influenza Pathogenesis and Control - Volume I. 2014;3–34.

- BöttcherE, Matrosovich T, Beyerle M, Klenk HD, Garten W, Matrosovich M. Proteolytic Activation of Influenza Viruses by Serine Proteases TMPRSS2 and HAT from Human Airway Epithelium. Journal of Virology. 2006 Oct 1;80(19):9896–8.

- Limburg H, Harbig A, Bestle D, Stein DA, Moulton HM, Jaeger J, et al. TMPRSS2 Is the Major Activating Protease of Influenza a Virus in Primary Human Airway Cells and Influenza B Virus in Human Type II Pneumocytes. Schultz-Cherry S, editor. Journal of Virology. 2019 Nov;93(21).

- Shen LW, Mao HJ, Wu YL, Tanaka Y, Zhang W. TMPRSS2: A potential target for treatment of influenza virus and coronavirus infections. Biochimie [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1;142:1–10. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300908417301876?

- Bi Y, Yang J, Wang L, Ran L, Gao GF. Ecology and Evolution of Avian Influenza Viruses. Current Biology. 2024 Aug;34(15):R716–21.

- Abe M, Tahara M, Sakai K, Yamaguchi H, Kazuhiko Kanou, Kazuya Shirato, et al. TMPRSS2 Is an Activating Protease for Respiratory Parainfluenza Viruses. Journal of Virology. 2013 Aug 22;87(21):11930–5.

- Schwerdtner M, Schmacke LC, Nave J, Limburg H, Steinmetzer T, Stein DA, et al. Unveiling the Role of TMPRSS2 in the Proteolytic Activation of Pandemic and Zoonotic Influenza Viruses and Coronaviruses in Human Airway Cells. Viruses. 2024 Nov 20;16(11):1798.

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020 Mar;181(2):271–80.

- Vanyo Mitev, Tsanko Mondeshki, Ani Miteva, Konstantin Tashkov, Dimitrova V. COVID-19 Prophylactic Effect of Bromhexine Hydrochloride. 2024 Oct 25.

- Simmons G, Gosalia DN, Rennekamp AJ, Reeves JD, Diamond SL, Bates P. Inhibitors of Cathepsin L Prevent Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [Internet]. 2005 Aug 16;102(33):11876–81. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/content/102/33/11876.

- Simmons G, Zmora P, Gierer S, Heurich A, Pöhlmann S. Proteolytic Activation of the SARS-coronavirus Spike protein: Cutting Enzymes at the Cutting Edge of Antiviral Research. Antiviral Research. 2013 Dec;100(3):605–14.

- Du L, Kao RY, Zhou Y, He Y, Zhao G, Wong C, et al. Cleavage of Spike Protein of SARS Coronavirus by Protease Factor Xa Is Associated with Viral Infectivity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007 Jul;359(1):174–9.

- Koch J, Uckeley ZM, Doldan P, Stanifer M, Boulant S, Lozach P. TMPRSS2 Expression Dictates the Entry Route Used by SARS-CoV-2 to Infect Host Cells. The EMBO Journal. 2021 Jul 13;40(16).

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Pöhlmann S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Molecular Cell. 2020 May;78(4).

- Mykytyn AZ, Breugem TI, Geurts MH, Beumer J, Schipper D, Romy van Acker, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Entry Is Type II Transmembrane Serine protease-mediated in Human Airway and Intestinal Organoid Models. Journal of virology. 2023 Aug 31;97(8).

- Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of Spike Glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on Virus Entry and Its Immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nature Communications. 2020 Mar 27;11(1).

- Maggio R, Corsini GU. Repurposing the Mucolytic Cough Suppressant and TMPRSS2 Protease Inhibitor Bromhexine for the Prevention and Management of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pharmacological Research. 2020 Jul;157:104837.

- Depfenhart, M. A SARS-CoV-2 Prophylactic and Treatment; a Counter Argument against the Sole Use of Chloroquine. American Journal of Biomedical Science & Research. 2020 Apr 9;8(4):248–51.

- Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Okamura T, Shimizu Y, Hasegawa H, Takeda M, Nagata N. TMPRSS2 Contributes to Virus Spread and Immunopathology in the Airways of Murine Models after Coronavirus Infection. Gallagher T, editor. Journal of Virology. 2019 Jan 9;93(6).

- Breining P, Frølund AL, Højen JF, Gunst JD, Staerke NB, Saedder E, et al. Camostat Mesylate against SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19—Rationale, Dosing and Safety. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2020 Nov 22;128(2):204–12.

- Tobback E, Degroote S, Buysse S, Delesie L, Van Dooren L, Vanherrewege S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Camostat Mesylate in Early COVID-19 Disease in an Ambulatory setting: a Randomized placebo-controlled Phase II Trial. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2022 Sep;122:628–35.

- Khan U, Muhammad Mubariz, Yehya Khlidj, Nasir MM, Ramadan S, Saeed F, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Camostat Mesylate for Covid-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2024 Jul 19;24(1).

- Kinoshita T, Shinoda M, Nishizaki Y, Shiraki K, Hirai Y, Kichikawa Y, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Camostat Mesilate in Patients with COVID-19 (CANDLE study). BMC Medicine. 2022 Sep 27;20(1).

- Chupp G, Spichler-Moffarah A, Søgaard OS, Esserman D, Dziura J, Danzig L, et al. A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Trial of Oral Camostat Mesylate for Early Treatment of COVID-19 Outpatients Showed Shorter Illness Course and Attenuation of Loss of Smell and Taste. medRxiv: The Preprint Server for Health Sciences [Internet]. 2022 Jan 31 [cited 2022 Oct 17]; 2022.01.28.22270035. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35132421/.

- Marinov K, Tsanko Mondeshki, Georgiev H, Dimitrova VS, Vanyo Mitev. Effects of long-term Prophylaxis with Bromhexine Hydrochloride and Treatment with High Colchicine Doses of COVID-19. Pharmacia. 2025 Jan 13;72:1–10.

- Vanyo Mitev. Comparison of Treatment of COVID-19 with Inhaled bromhexine, Higher Doses of Colchicine and Hymecromone with WHO-recommended paxlovid, molnupiravir, remdesivir, anti-IL-6 Receptor Antibodies and Baricitinib. Pharmacia/Farmaciâ. 2023 Oct 20;70(4):1177–93.

- Depfenhart M, de Villiers D, Lemperle G, Meyer M, Di Somma S. Potential New Treatment Strategies for COVID-19: Is There a Role for Bromhexine as add-on therapy? Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2020 May 26.

- Ansarin K, Tolouian R, Ardalan M, Taghizadieh A, Varshochi M, Teimouri S, et al. Effect of Bromhexine on Clinical Outcomes and Mortality in COVID-19 patients: a Randomized Clinical Trial. BioImpacts. 2020 Jul 19;10(4):209–15.

- Eslami Ghayour A, Nazari S, Keramat F, Shahbazi F, Eslami-Ghayour A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine and Bromhexine Compared with Standard Care in Preventing Hospitalization of Outpatients with COVID-19: a Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Revista Clínica Española (English Edition) [Internet]. 2024 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Jun 17];224(2):86–95. Available from: https://www.revclinesp.es/en-evaluation-efficacy-n-acetylcysteine-bromhexine-compared-articulo-S225488742400002X?

- Fu Q, Zheng X, Zhou Y, Tang L, Chen Z, Ni S. Re-recognizing Bromhexine hydrochloride: Pharmaceutical Properties and Its Possible Role in Treating Pediatric COVID-19. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Dec 9];77(2):261–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7459257/.

- Ramin Tolouian, Moradi O, Mulla ZD, Shadi Ziaie, Haghighi M, Hadi Esmaily, et al. Bromhexine, for Post Exposure COVID-19 prophylaxis: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Control Trial. Research Square (Research Square). 2022 May 6.

- Ramin Tolouian, Mulla ZD. Controversy with Bromhexine in COVID-19; Where We Stand. Immunopathologia Persa. 2020 Aug 12;7(2):e12–2.

- Ogbac MK, Tamayo JE. Effect of Bromhexine among COVID-19 Patients - a Meta-anaylsis. 대한결핵및호흡기학회 추계학술발표초록집 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 7];129(0):412–2. Available from: https://kiss.kstudy.com/Detail/Ar?key=3921594.

- Vila Méndez ML, Antón Sanz C, Cárdenas García A del R, Bravo Malo A, Torres Martínez FJ, Martín Moros JM, et al. Efficacy of Bromhexine versus Standard of Care in Reducing Viral Load in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19 Disease Attended in Primary Care: a Randomized Open-Label Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine [Internet]. 2022 Dec 24 [cited 2024 Mar 20];12(1):142. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9821213/.

- Vanyo Mitev. Colchicine—The Divine Medicine against COVID-19. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024 Jul 16;14(7):756–6.

- Duan Y, Wang J, Cai J, Kelley N, He Y. The leucine-rich Repeat (LRR) Domain of NLRP3 Is Required for NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2022 Dec 1;298(12):102717–7.

- Kelley N, Jeltema D, Duan Y, He Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: an Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences [Internet]. 2019 Jul 6;20(13):3328. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6651423/.

- Anil Akbal, Alesja Dernst, Lovotti M, Mangan M, McManus RM, Latz E. How Location and Cellular Signaling Combine to Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2022 Sep 20;19(11):1201–14.

- Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A. Inflammasome Recognition of Influenza Virus Is Essential for Adaptive Immune Responses. The Journal of Experimental Medicine [Internet]. 2009 Jan 19;206(1):79–87. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2626661/.

- Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, et al. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Mediates in Vivo Innate Immunity to Influenza a Virus through Recognition of Viral RNA. Immunity. 2009 Apr;30(4):556–65.

- Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JPY. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular Activation and Regulation to Therapeutics. Nature Reviews Immunology [Internet]. 2019 Apr 29;19(8):477–89. Available from:https://www.nature.com/articles/s41577-019-0165-0.

- Dadkhah M, Sharifi M. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Mechanisms of activation, regulation, and Role in Diseases. International Reviews of Immunology. 2024 Oct 14;44(2):98–111.

- Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Núñez G. Cutting Edge: TNF-α Mediates Sensitization to ATP and Silica via the NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Absence of Microbial Stimulation. The Journal of Immunology. 2009 Jun 19;183(2):792–6.

- Tate MD, Mansell A. An Update on the NLRP3 Inflammasome and influenza: the Road to Redemption or perdition? Current Opinion in Immunology. 2018 Jun 30;54:80–5.

- Beesetti, S. Ubiquitin Ligases in Control: Regulating NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark. 2025 Mar 19;30(3).

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB Activating Pattern Recognition and Cytokine Receptors License NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Regulating NLRP3 Expression. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) [Internet]. 2009 Jul 15;183(2):787–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19570822/.

- Liu X, Wang H, Shi S, Xiao J. Association between IL-6 and Severe Disease and Mortality in COVID-19 disease: a Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2021 Jun 3;postgradmedj-2021-139939.

- Tosato G, Jones K. Interleukin-1 Induces interleukin-6 Production in Peripheral Blood Monocytes. Blood. 1990 Mar 15;75(6):1305–10.

- Chen W, Zheng KI, Liu S, Yan Z, Xu C, Qiao Z. Plasma CRP Level Is Positively Associated with the Severity of COVID-19. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2020 May 15;19(1).

- Manson JJ, Crooks C, Naja M, Ledlie A, Goulden B, Liddle T, et al. COVID-19-associated Hyperinflammation and Escalation of Patient care: a Retrospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. The Lancet Rheumatology [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1;2(10):e594–602. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanrhe/article/PIIS2665-9913(20)30275-7/fulltext#seccestitle150.

- Slaats J, ten Oever J, van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG. IL-1β/IL-6/CRP and IL-18/ferritin: Distinct Inflammatory Programs in Infections. Bliska JB, editor. PLOS Pathogens. 2016 Dec 15;12(12):e1005973.

- Potere N, Del Buono MG, Caricchio R, Cremer PC, Vecchié A, Porreca E, et al. Interleukin-1 and the NLRP3 Inflammasome in COVID-19: Pathogenetic and Therapeutic Implications. eBioMedicine. 2022 Nov;85:104299.

- Yin M, Marrone L, Peace CG, O’Neill LAJ. NLRP3, the Inflammasome and COVID-19 Infection. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2023 Jan 20 [cited 2025 Feb 11];116(7):502–7. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10382191/.

- Xu H, Akinyemi IA, Chitre SA, Loeb JC, Lednicky JA, McIntosh MT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viroporin Encoded by ORF3a Triggers the NLRP3 Inflammatory Pathway. Virology. 2022 Mar;568:13–22.

- Guarnieri JW, Alessia Angelin, Murdock DG, Schaefer P, Prasanth Portluri, Lie T, et al. SARS-COV-2 Viroporins Activate the NLRP3-inflammasome by the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023 Feb 20;14.

- Pan P, Shen M, Yu Z, Ge W, Chen K, Tian M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 N Protein Promotes NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation to Induce Hyperinflammation. Nature Communications. 2021 Aug 2;12(1).

- Sun X, Liu Y, Huang Z, Xu W, Hu W, Yi L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 non-structural Protein 6 Triggers NLRP3-dependent Pyroptosis by Targeting ATP6AP1. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2022 Jan 8;29(6):1240–54.

- Theobald S, Simonis A, Georgomanolis T, Christoph Kreer, Zehner M, Eisfeld HS, et al. Long-lived Macrophage Reprogramming Drives Spike Protein-mediated Inflammasome Activation in COVID-19. 2021 Aug 9;13(8).

- Eisfeld HS, Simonis A, Winter S, Chhen J, Ströh LJ, Krey T, et al. Viral Glycoproteins Induce NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pyroptosis in Macrophages. Viruses. 2021 Oct 15;13(10):2076.

- Planès R, Pinilla M, Santoni K, Hessel A, Passemar C, Lay K, et al. Human NLRP1 Is a Sensor of Pathogenic Coronavirus 3CL Proteases in Lung Epithelial Cells. Molecular Cell [Internet]. 2022 Jul 7;82(13):2385-2400.e9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9108100/.

- Ambrożek-Latecka M, Kozlowski P, Hoser G, Bandyszewska M, Karolina Hanusek, Dominika Nowis, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Its ORF3a, E and M Viroporins Activate Inflammasome in Human Macrophages and Induce of IL-1α in Pulmonary Epithelial and Endothelial Cells. Cell death discovery. 2024 Apr 25;10(1).

- Cerato JA, Silva, Porto BN. Breaking Bad: Inflammasome Activation by Respiratory Viruses. Biology. 2023 Jul 1;12(7):943–3.

- Sefik E, Qu R, Junqueira C, Kaffe E, Mirza H, Zhao J, et al. Inflammasome Activation in Infected Macrophages Drives COVID-19 Pathology. Nature. 2022 Apr 28.

- Song H, Liu B, Huai W, Yu Z, Wang W, Zhao J, et al. The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TRIM31 Attenuates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Promoting Proteasomal Degradation of NLRP3. Nature Communications. 2016 Dec;7(1).

- Cai B, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Ma C, Yi F, et al. USP5 Attenuates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Promoting Autophagic Degradation of NLRP3. Autophagy [Internet]. 2021 Sep 5 [cited 2024 Nov 26];18(5):990–1004. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9196652/.

- Paik S, Kim JK, Silwal P, Sasakawa C, Jo EK. An Update on the Regulatory Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2021 Apr 13;18(5):1141–60.

- Yang Y, Wang H, Kouadir M, Song H, Shi F. Recent Advances in the Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Its Inhibitors. Cell Death & Disease. 2019 Feb;10(2).

- Ji X, Song Z, He J, Guo S, Chen Y, Wang H, et al. NIMA-related Kinase 7 Amplifies NLRP3 Inflammasome pro-inflammatory Signaling in microglia/macrophages and Mice Models of Spinal Cord Injury. Experimental Cell Research. 2020 Dec 9;398(2):112418–8.

- Zhang E, Li X. The Emerging Roles of Pellino Family in Pattern Recognition Receptor Signaling. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022 Feb 7;13.

- Kim, SK. The Mechanism of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pathogenic Implication in the Pathogenesis of Gout. Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2022 Jul 1;29(3):140–53.

- Pan X, Wu S, Wei W, Chen Z, Wu Y, Gong K. Structural and Functional Basis of JAMM Deubiquitinating Enzymes in Disease. Biomolecules [Internet]. 2022 Jun 29 [cited 2025 Mar 4];12(7):910. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9313428/.

- Palazón-Riquelme P, Worboys JD, Green J, Valera A, Martín-Sánchez F, Pellegrini C, et al. USP7 and USP47 Deubiquitinases Regulate NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. EMBO Reports. 2018 Sep 11;19(10).

- Martens A, van Loo G. A20 at the Crossroads of Cell Death, Inflammation, and Autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2019 Aug 19;12(1):a036418.

- Song N, Li T. Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome by Phosphorylation. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018 Oct 8;9.

- Zhang Z, Meszaros G, He W, Xu Y, de Fatima Magliarelli H, Mailly L, et al. Protein Kinase D at the Golgi Controls NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine [Internet]. 2017 Sep 4 [cited 2021 Dec 6];214(9):2671–93. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584123/.

- Song N, Liu ZS, Xue W, Bai ZF, Wang QY, Dai J, et al. NLRP3 Phosphorylation Is an Essential Priming Event for Inflammasome Activation. Molecular Cell. 2017 Oct;68(1):185-197.e6.

- Spalinger MR, Kasper S, Gottier C, Lang S, Atrott K, Vavricka SR, et al. NLRP3 Tyrosine Phosphorylation Is Controlled by Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase PTPN22. Journal of Clinical Investigation [Internet]. 2016 Apr 4;126(5):1783–800. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4855944/.

- McKee CM, Fischer FA, Bezbradica JS, Coll RC. PHOrming the inflammasome: Phosphorylation Is a Critical Switch in Inflammasome Signalling. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2021 Dec 2;49(6):2495–507.

- Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Förster I, et al. Type I Interferon Inhibits Interleukin-1 Production and Inflammasome Activation. Immunity. 2011 Feb;34(2):213–23.

- Masters SL, Mielke LA, Cornish AL, Sutton CE, O’Donnell J, Cengia LH, et al. Regulation of interleukin-1beta by interferon-gamma Is Species specific, Limited by Suppressor of Cytokine Signalling 1 and Influences interleukin-17 Production. EMBO Reports [Internet]. 2010 Aug 1;11(8):640–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 2059.

- Lee JS, Shin EC. The Type I Interferon Response in COVID-19: Implications for Treatment. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020.

- Wang N, Zhan Y, Zhu L, Hou Z, Liu F, Song P, et al. Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study Shows Early Interferon Therapy Is Associated with Favorable Clinical Responses in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Host & Microbe. 2020 Sep;28(3):455-464.e2.

- Vora SM, Lieberman J, Wu H. Inflammasome Activation at the Crux of Severe COVID-19. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021 Aug 9;21(11):694–703.

- Tate MD, Ong JDH, Dowling JK, McAuley JL, Robertson AB, Latz E, et al. Reassessing the Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome during Pathogenic Influenza a Virus Infection via Temporal Inhibition. Scientific Reports. 2016 Jun 10;6(1).

- Sho Nakakubo, Unoki Y, Kitajima K, Terada M, Hiroyuki Gatanaga, Norio Ohmagari, et al. Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level One Week after Admission Is the Strongest Predictor of Prognosis of COVID-19: a Large Observational Study Using the COVID-19 Registry Japan. Viruses. 2023 Mar 2;15(3):671–1.

- Vanyo Mitev, Marinov K, Rumen Tiholov, Konstantin Tashkov, Radoslav Bilyukov, Lilov AI, et al. High Colchicine Doses Are More Effective in COVID-19 Outpatients than Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir, Remdesivir, and Molnupiravir. 2024.

- Smart SJ, Polachek SW. COVID-19 Vaccine and risk-taking. Journal of risk and uncertainty. 2024 Feb 1;68(1):25–49.

- Kelleni, MT. SARS CoV-2 Viral Load Might Not Be the Right Predictor of COVID-19 Mortality. Journal of Infection. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mondeshki T, Bilyukov R, Tomov T, Mihaylov M, Mitev V. Complete, Rapid Resolution of Severe Bilateral Pneumonia and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a COVID-19 Patient: Role for a Unique Therapeutic Combination of Inhalations with Bromhexine, Higher Doses of Colchicine, and Hymecromone. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 21];14(10):e30269. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 9653.

- Lilov A, Palaveev K, Mitev V. High Doses of Colchicine Act as “Silver Bullets” against Severe COVID-19. Cureus. 2024.

- Tsanko Mondeshki, Vanyo Mitev. High-Dose Colchicine: Key Factor in the Treatment of Morbidly Obese COVID-19 Patients. Cureus. 2024.

- Mitev, V. High colchicine doses are really silver bullets against COVID-19. Acta Medica Bulgarica. 2024, 51(4): 95-96.

- Dimitar Bulanov, Atanas Yonkov, Arabadzhieva E, Vanyo Mitev. Successful Treatment with High-Dose Colchicine of a 101-Year-Old Patient Diagnosed with COVID-19 after an Emergency Cholecystectomy. Cureus. 2024.

- Mondeshki T, Bilyukov R, Mitev V. Effect of an Accidental Colchicine Overdose in a COVID-19 Inpatient with Bilateral Pneumonia and Pericardial Effusion. Cureus. 2023.

- Vanyo Mitev, Mondeshki Tsanko, Marinov K, Radoslav Bilyukov. Colchicine, Bromhexine, and Hymecromone as Part of COVID-19 Treatment-Cold, Warm, Hot. 2023 Jan 30 [cited 2025 Apr 8];106–14. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Rumen Tiholov, Lilov AI, Gergana Georgieva, Palaveev KR, Konstantin Tashkov, Vanyo Mitev. Effect of Increasing Doses of Colchicine on the Treatment of 333 COVID-19 Inpatients. Immunity Inflammation and Disease. 2024 ;12(5). 1 May.

- Vanyo Mitev. What Is the Lowest Lethal Dose of colchicine? Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2023 Nov 25;37(1).

- Vanyo Mitev, Tsanko Mondeshki, Ani Miteva, Konstantin Tashkov, Dimitrova V. COVID-19 Prophylactic Effect of Bromhexine Hydrochloride. Preprints 2024. 2024.

- Mitev, V. Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 and Influenza with Bromhexine and Colchicine. 2025. XXXth Anniversary Medicine and Football International Scientific Conference, 15 april 2025, Sofia, Bulgaria; oral presentation.

- Mitev, V. Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 and Influenza with Bromhexine and Colchicine. Medizina I Sport. 2025;(1-2):38–9.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).