Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, S15–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K.B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, C.-T.; Lam, S.-H.; Lee, S.-S.; Su, M.-J. Hypoglycemic action of borapetoside A from the plant Tinospora crispa in mice. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Al Kaabi, J. Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes–Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Gao, P.; Seshasai, S.R.; Gobin, R.; Kaptoge, S.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ingelsson, E.; Lawlor, D.A.; Selvin, E.; et al.; The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010, 375, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, V.A.; Kulkarni, K.D. Management of Type 2 Diabetes: Oral Agents, Insulin, and Injectables. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, S29–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchuluun, B.; Pinkosky, S.L.; Steinberg, G.R. Lipogenesis inhibitors: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamon, M.; Sumitani, J.-I.; Tani, S.; Kawaguchi, T. Characterization and gene cloning of a maltotriose-forming exo-amylase from Kitasatospora sp. MK-1785. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 4743–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakowski, J.J.; Bruns, D.E. Biochemistry of Human Alpha Amylase Isoenzymes. CRC Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1985, 21, 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinfemiwa, O.; Zubair, M.; Muniraj, T. Amylase. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Gigras, P.; Mohapatra, H.; Goswami, V.K.; Chauhan, B. Microbial α-amylases: a biotechnological perspective. Process. Biochem. 2003, 38, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Liang, J.; Deng, G.; Yu, M.; Long, H. New insights into the origin and evolution of α-amylase genes in green plants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Ali, S.; Hassan, A.; Tahir, H.M.; Mumtaz, S.; Mumtaz, S. Biosynthesis and industrial applications of α-amylase: a review. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachons, C.P.D.; Breslin, P.A.S. Salivary Amylase: Digestion and Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maarel, M.J.; van der Veen, B.; Uitdehaag, J.C.; Leemhuis, H.; Dijkhuizen, L. Properties and applications of starch-converting enzymes of the α-amylase family. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 94, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, T.M. Amylase. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 70, M8–M9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Feng, D.; Wang, T.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase: Potential linkage for whole cereal foods on prevention of hyperglycemia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6320–6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kumar, V.; Nayak, S.K.; Wadhwa, P.; Kaur, P.; Sahu, S.K. Alpha-amylase as molecular target for treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiele, M.; Ghoos, Y.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vantrappen, G. Effects of acarbose on starch hydrolysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1992, 37, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, T.; Samadi, A.; Burade, S.; Mahmud, T. Complete biosynthetic pathway to the antidiabetic drug acarbose. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropsha, A. Best Practices for QSAR Model Development, Validation, and Exploitation. Mol. Inform. 2010, 29, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turabekova, M.A.; Rasulev, B.F.; Dzhakhangirov, F.N.; Salikhov, S.I. Aconitum and Delphinium alkaloids "Drug-likeness" descriptors related to toxic mode of action. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2008, 25, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropova, A.P.; Toropov, A.A.; Rasulev, B.F.; Benfenati, E.; Gini, G.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. QSAR models for ACE-inhibitor activity of tri-peptides based on representation of the molecular structure by graph of atomic orbitals and SMILES. Struct. Chem. 2012, 23, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatica, P.; Cassani S Fau - Chirico, N.; Chirico, N. QSARINS-chem: Insubria datasets and new QSAR/QSPR models for environmental pollutants in QSARINS. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2014, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.C. QSAR. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 4th ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press, 2024; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, A.; Sizochenko, N.; Rasulev, B.; Gorb, L.; Leszczynski, J. In vivo toxicity of nitroaromatics: A comprehensive quantitative structure–activity relationship study. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 2227–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juretic, D.; Kusic, H.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Rasulev, B.; Bozic, A.L. Modeling of photooxidative degradation of aromatics in water matrix; combination of mechanistic and structural-relationship approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 257, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghighi, A.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Timmerman, T.; Milenković, D.; Lučić, B.; Rasulev, B. In Silico Prediction of the Toxicity of Nitroaromatic Compounds: Application of Ensemble Learning QSAR Approach. Toxics 2022, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, S.A.; Ghimire, M.P.; Lamichhane, T.A.; Adhikari, R.A.; Adhikari, A. Identification of potential human pancreatic α-amylase inhibitors from natural products by molecular docking, MM/GBSA calcula-tions, MD simulations, and ADMET analysis. PlOS One 2023, 18, e0275765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropsha, A.; Isayev, O.; Varnek, A.; Schneider, G.; Cherkasov, A. Integrating QSAR modelling and deep learning in drug discovery: the emergence of deep QSAR. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 23, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, R.D.; Patterson, D.E.; Bunce, J.D. Comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA). 1. Effect of shape on binding of steroids to carrier proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 5959–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuravskyi, Y.; Iduoku, K.; Erickson, M.E.; Karuth, A.; Usmanov, D.; Casanola-Martin, G.; Sayfiyev, M.N.; Ziyaev, D.A.; Smanova, Z.; Mikolajczyk, A.; et al. Quantitative Structure─Permittivity Relationship Study of a Series of Polymers. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Akhtar, J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Guan, S.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Jeon, H.-N.; Kim, M.S.; et al. Comprehensive strategies of machine-learning-based quantitative structure-activity relationship models. iScience 2021, 24, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieguez-Santana, K.; Pham-The, H.; Rivera-Borroto, O.M.; Puris, A.; Le-Thi-Thu, H.; Casanola-Martin, G.M. A Two QSAR Way for Antidiabetic Agents Targeting Using α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: Model Parameters Settings in Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadpanah, E.; Riahi, S.; Abbasi-Radmoghaddam, Z.; Gharaghani, S.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtanai, M. A simple and robust model to predict the inhibitory activity of α-glucosidase inhibitors through combined QSAR modeling and molecular docking techniques. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1811–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhan, M.; Singh, R.; Devi, M.; Sindhu, J.; Bhatia, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P. Synthesis, molecular docking and QSAR study of thiazole clubbed pyrazole hybrid as α-amylase inhibitor. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 39, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Bose, S.; Panda, P.; Basak, S.; Ghosh, N.; Mandal, S.C.; Singhmura, S.; Halder, A.K. Finding structural requirements of structurally diverse α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitors through validated and predictive 2D-QSAR and 3D-QSAR analyses. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 126, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatica, P.; Chirico, N.; Papa, E.; Cassani, S.; Kovarich, S. QSARINS: A new software for the development, analysis, and validation of QSAR MLR models. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillers, J. Genetic algorithms in molecular modeling; Academic Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fjodorova, N.; Novič, M.; Venko, K.; Drgan, V.; Rasulev, B.; Saçan, M.T.; Erdem, S.S.; Tugcu, G.; Toropova, A.P.; Toropov, A.A. How fullerene derivatives (FDs) act on therapeutically important targets associated with diabetic diseases. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhijawi, B.; Awajan, A. Genetic algorithms: theory, genetic operators, solutions, and applications. Evol. Intell. 2023, 17, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetnic, M.; Perisic, D.J.; Kovacic, M.; Ukic, S.; Bolanca, T.; Rasulev, B.; Kusic, H.; Bozic, A.L. Toxicity of aromatic pollutants and photooxidative intermediates in water: A QSAR study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 169, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holford, N. Pharmacodynamic principles and the time course of immediate drug effects. Transl. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 25, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.; Bertola, M. Alvascience: A New Software Suite for the QSAR Workflow Applied to the Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Thakkar, A.; Mercado, R.; Engkvist, O. Molecular representations in AI-driven drug discovery: a review and practical guide. J. Chemin- 2020, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, W.M.; Bixler, G.V.; Brucklacher, R.M.; Lin, C.-M.; Patel, K.M.; VanGuilder, H.D.; LaNoue, K.F.; Kimball, S.R.; Barber, A.J.; A Antonetti, D.; et al. A multistep validation process of biomarkers for preclinical drug development. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009, 10, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rácz, A.; Bajusz, D.; Héberger, K. Modelling methods and cross-validation variants in QSAR: a multi-level analysis$. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2018, 29, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, N.; Chen, Y.; Kirchmair, J. Validation strategies for target prediction methods. Briefings Bioinform. 2020, 21, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hu, J.; Ho, Y. Global Performance and Trend of QSAR/QSPR Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Mol. Informatics 2014, 33, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramspek, C.L.; Jager, K.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C.; van Diepen, M. External validation of prognostic models: what, why, how, when and where? Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 14, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P.; Kar, S.; Ambure, P.; Roy, K. Prediction reliability of QSAR models: an overview of various validation tools. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, E. Spectral Moments of the Edge Adjacency Matrix in Molecular Graphs. 1. Definition and Applications to the Prediction of Physical Properties of Alkanes. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1996, 36, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Libera, J.L.; Caballero, J.; Toropova, A.P.; Toropov, A.A. Estimation of 2D autocorrelation descriptors and 2D Monte Carlo descriptors as a tool to build up predictive models for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2019, 184, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginex, T.; Vazquez, J.; Gilbert, E.; Herrero, E.; Luque, F.J. Lipophilicity in Drug Design: An Overview of Lipophilicity Descriptors in 3D-QSAR Studies. Futur. Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisoni, F.; Schneider, G. Molecular Scaffold Hopping via Holistic Molecular Representation. Methods Mol Biol 2021, 2266, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, I. Fragment Descriptors in SAR/QSAR/QSPR Studies, Molecular Similarity Analysis and in Virtual Screening. In Chemoinformatics Approaches to Virtual Screening; Varnek, A., Tropsha, A., Eds.; Chapter 1, The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, L.R.d.S.; Moreira-Filho, J.T.; Neves, B.J.; Maidana, R.L.B.R.; Guimarães, A.C.R.; Furnham, N.; Andrade, C.H.; Silva, F.P. In silico Strategies to Support Fragment-to-Lead Optimization in Drug Discovery. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

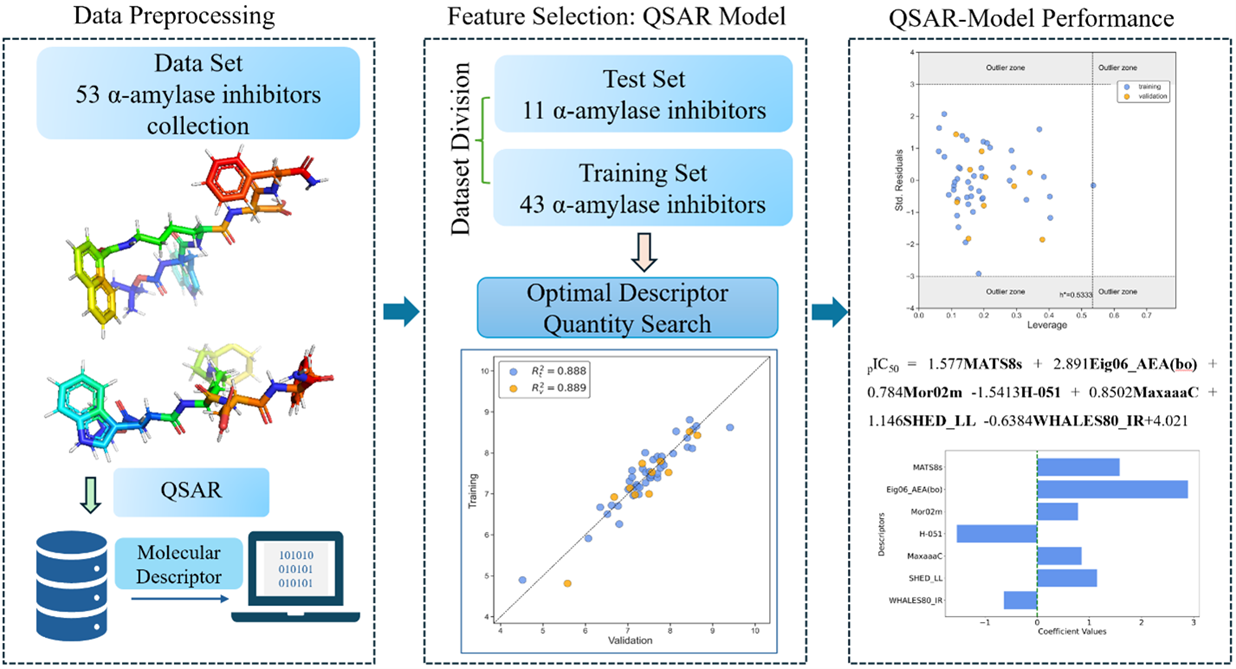

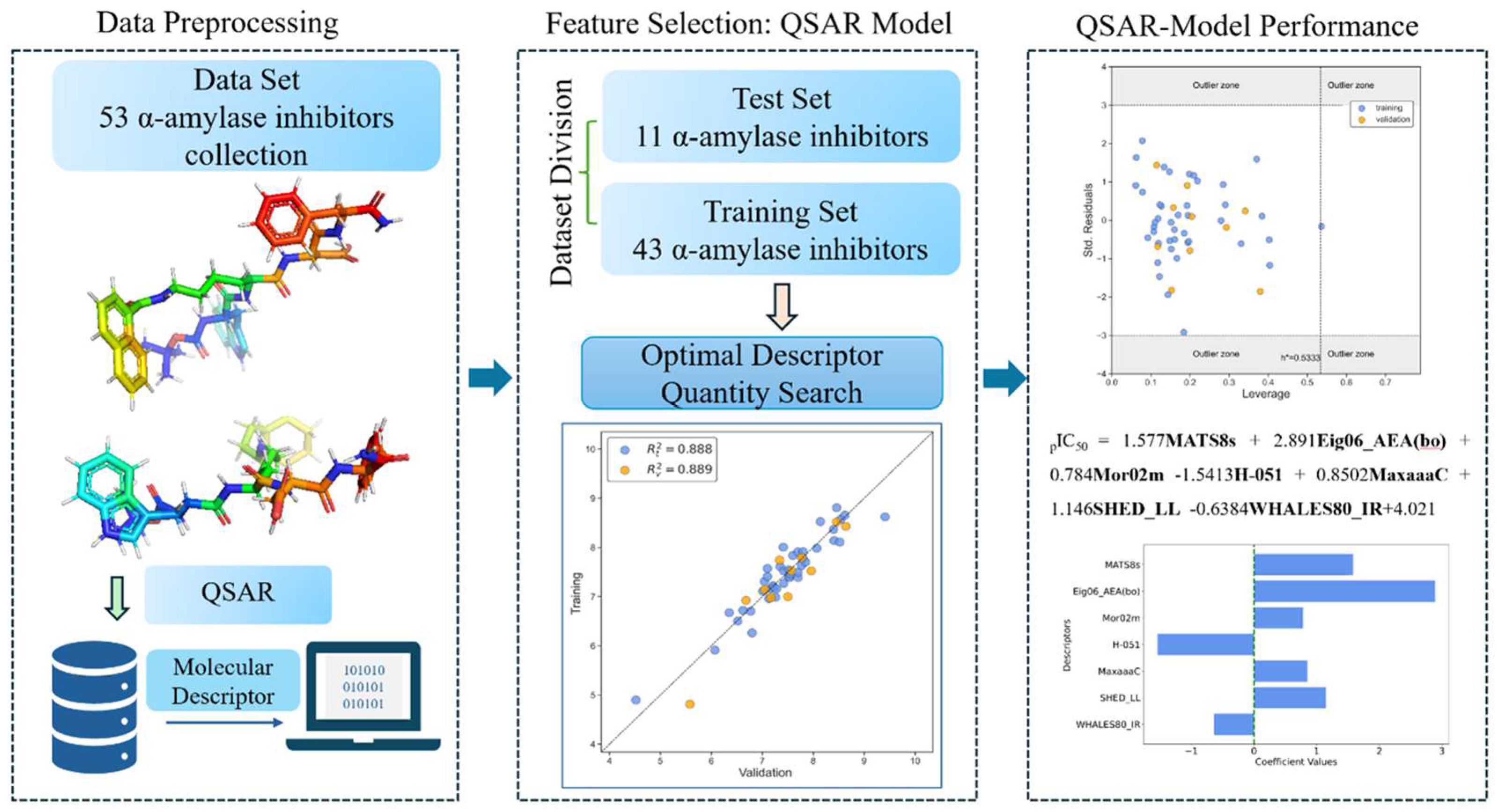

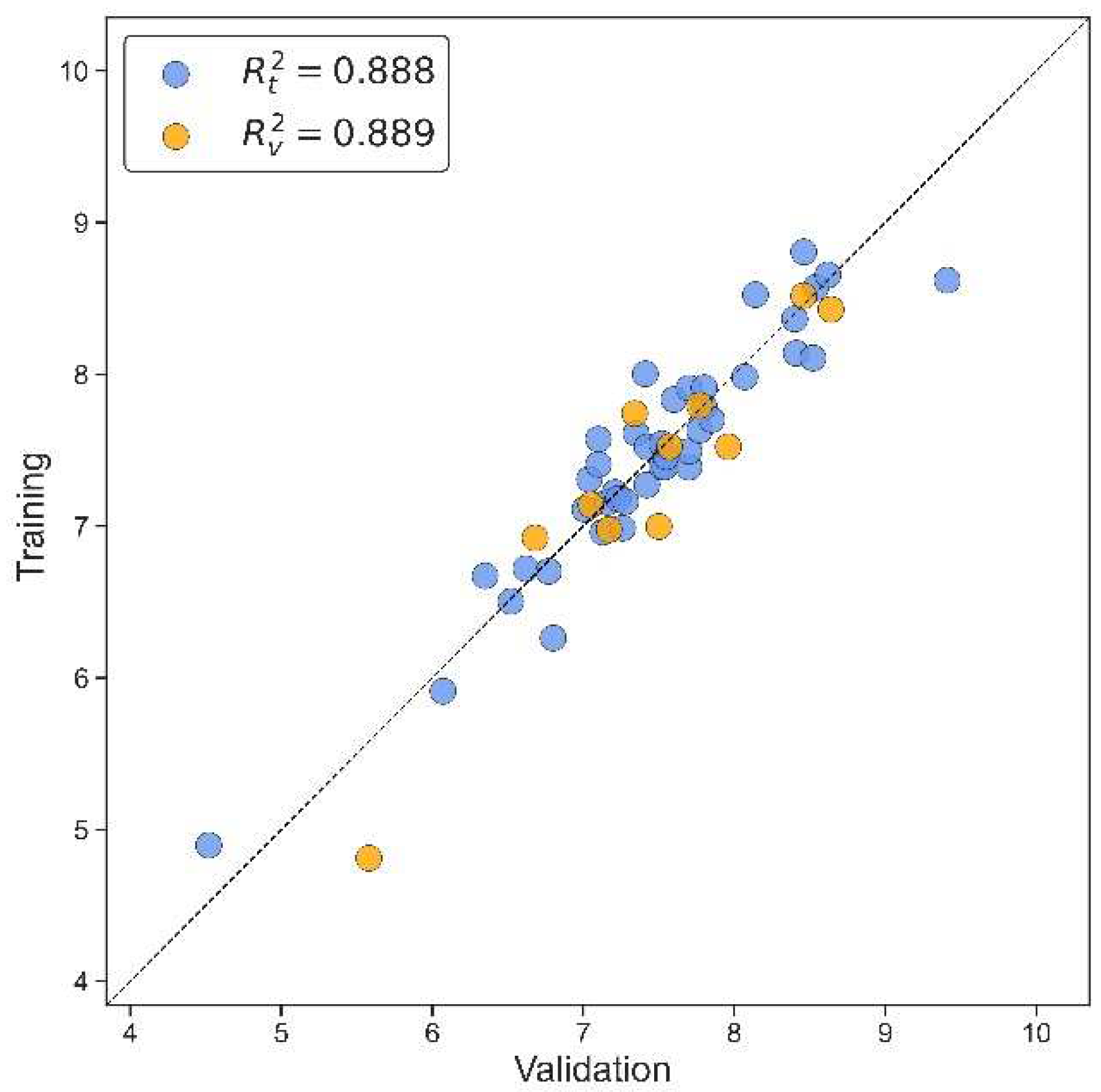

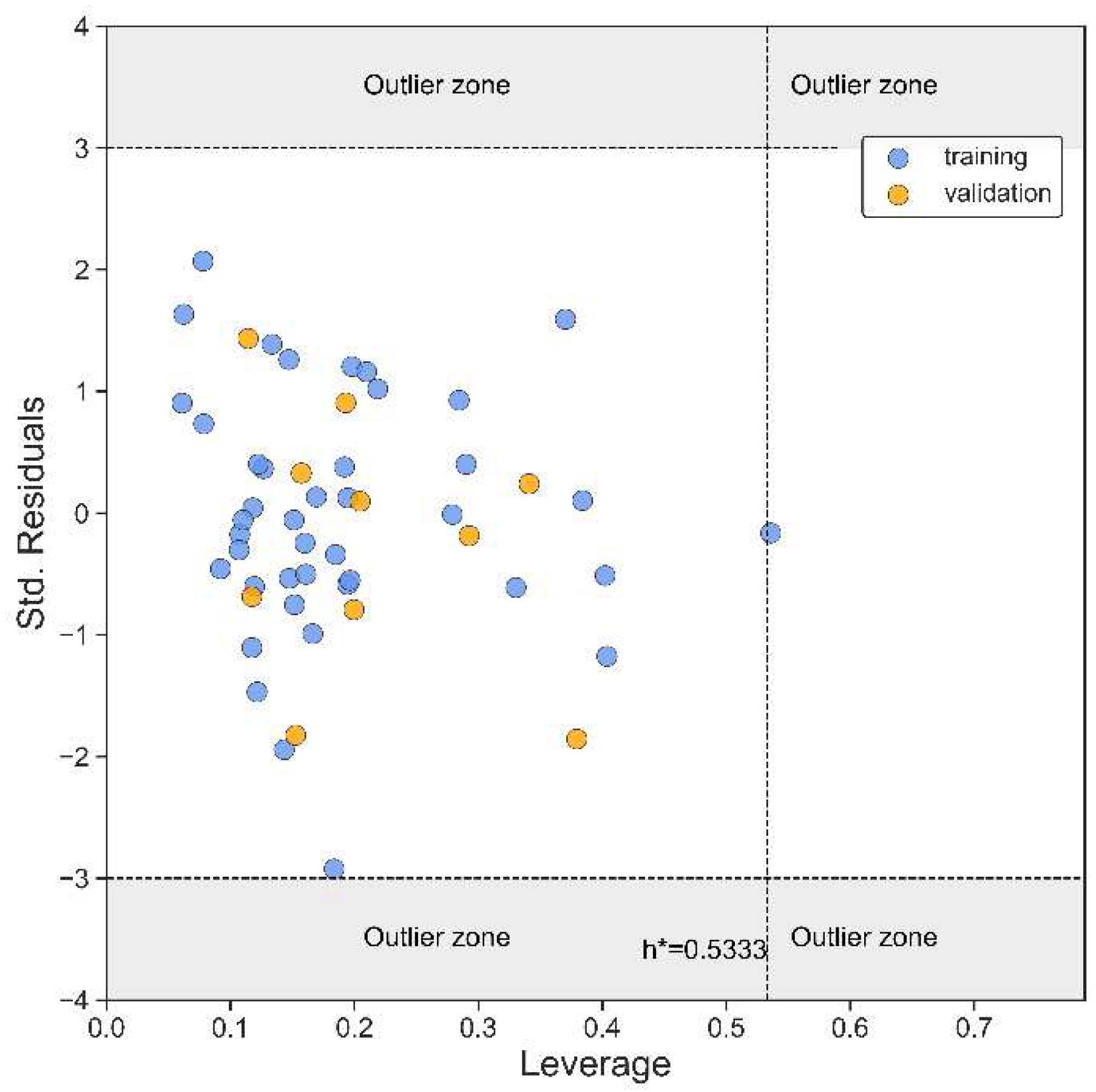

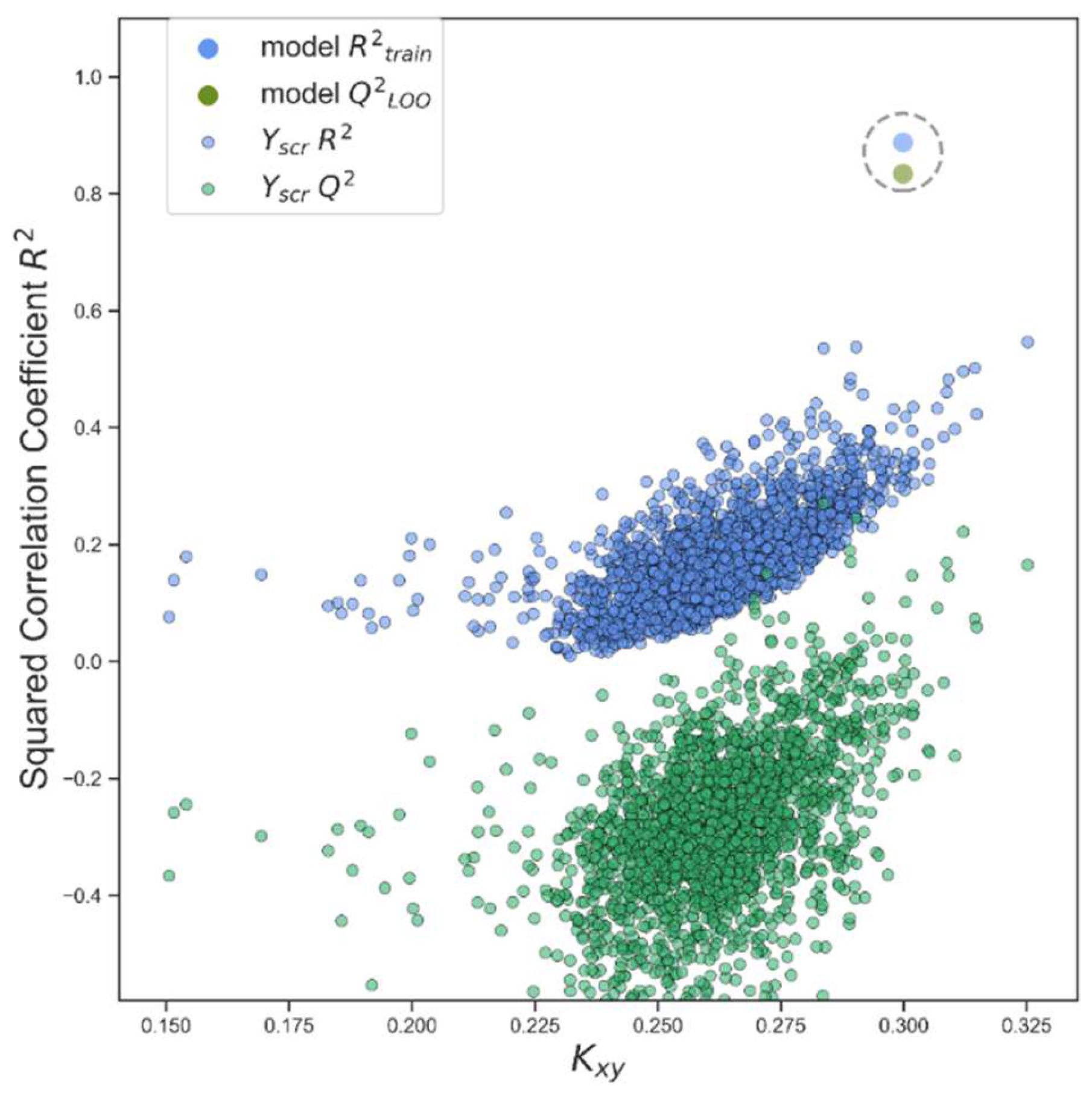

| N(TS/ES)* | R²train | R2adj | R²test | Q2Loo | RMSEtrain | RMSEval | RMSEtest | F | Intercept |

| 43/11 | 0.888 | 0.865 | 0.889 | 0.834 | 0.268 | 0.326 | 0.350 | 38.524 | 4.021 |

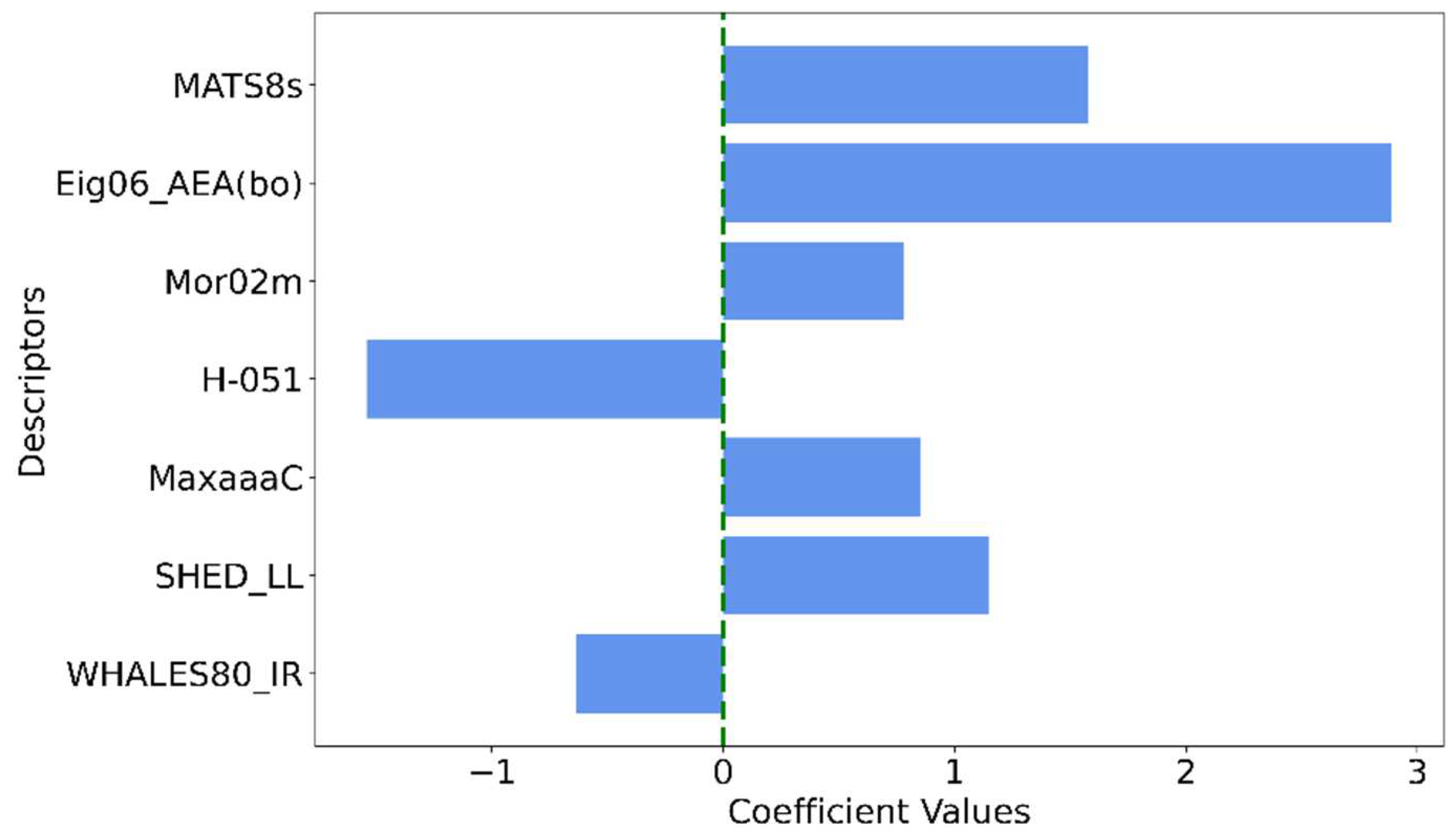

| Descriptor | Description | Descriptor family |

|---|---|---|

| MATS8s | Moran autocorrelation of lag 8 weighted by I-state | 2D autocorrelations |

| Eig06_AEA(bo) | Eigenvalue number 6 from augmented edge adjacency matrices weighted by bond order | Edge adjacency indices |

| Mor02m | Signal 02 / weighted by mass | 3D-MoRSE descriptors |

| H-051 | H attached to alpha C | Atom-centered fragments |

| MaxaaaC | Maximum aaaC | Atom-type E-state indices |

| SHED_LL | SHED Lipophilic-Lipophilic | Pharmacophore descriptors |

| WHALES80_IR | WHALES Isolation-Remoteness ratio (IR) (percentile 80) | WHALES descriptors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).