1. Introduction and Literature Review

In the context of increasingly pronounced economic and social changes in European mountain regions, commercial entrepreneurship is gaining strategic importance in maintaining territorial cohesion and ensuring a decent standard of living for local populations. Small commercial businesses in mountain areas not only provide essential goods and services, but also contribute significantly to preserving local traditions and revitalizing economies in territories often at risk of depopulation. However, entrepreneurs in mountainous areas face complex challenges: limited accessibility, underdeveloped infrastructure, restricted markets, and economic instability exacerbated by external factors such as fiscal policies or climatic conditions.

In this equation, the ability to anticipate economic developments and assess business sustainability becomes essential. This article analyzes the performance of forecasting models applied to key economic indicators relevant to mountain commercial entrepreneurship, aiming to identify both the vulnerabilities and opportunities of this sector. The study is based on official data from 15 European countries and applies advanced statistical methods (such as RMSE, MAPE, MAE) to better understand the dynamics of mountain businesses and their impact on employment.

Through this research, the authors aim to provide an overview of current and future trends in mountain commercial entrepreneurship and to support the development of economic policies tailored to the specific needs of these regions. In a mountain landscape undergoing continuous transformation, adaptability, institutional support, and the integration of innovation are becoming key elements for the sustainable development of local businesses.

In small mountain villages, the presence of commercial businesses plays a crucial role in inhabiting the areas and ensuring the well-being of residents. However, small commercial enterprises—just like other general interest services—tend to experience a numerical decline, contributing to the marginalization of the local communities they serve and widening the gap between them and urbanized areas.

Given this context, ensuring a mix of general interest services in mountain regions has represented a major challenge for decision-makers, who are concerned with guaranteeing equal rights and opportunities for people living everywhere, regardless of how remote the location is (Fassmann et al., 2015; Stielike, 2024). This issue is also mentioned in the EU’s Territorial Agenda 2030 (EC, 2020) – a “Just” Europe, a document designed as a guide for the 2021–2027 cohesion policy.

The EU’s Rural Vision, approved by the European Commission in 2021, also reiterates the importance of supporting small mountain communities, which are considered the cornerstones of development and the well-being of their residents. In small mountain communities, residents suffer from the progressive decline of essential services—a trend that has intensified following austerity policies implemented during times of crisis.

Low population density and the more dispersed structure of mountain settlements make it more difficult to generate the economies of scale necessary to efficiently provide both public and private services. Alternative solutions are being sought, many of which rely on the mobilization of local communities and the service sector—forms of social innovation that leverage new technologies (such as the smart village approach) and networks of collaboration between municipal administrations (SARURE, 2021).

These issues are exacerbated in mountain areas, where constraints further deepen disparities within the settlement network. Indeed, a few small or medium-sized towns—most of them located in valleys—serve as points of reference for vast mountain areas, to the extent that they often have a more complex functional profile than similarly sized towns located in the “shadow cone” of metropolitan areas. Proximity to the plains, ease of connectivity with large urban areas, and the ability to attract flows of people for work and tourism are key factors driving positive transitions in small mountain municipalities, with effects on the dynamics of the local business network (ESPON, 2018).

Negative demographic trends in less populated areas result in a shortage of locally available services, which limits quality of life and contributes to depopulation. This, in turn, compromises the sustainability of commercial services, placing them in a difficult-to-manage vicious circle (ESPON, 2017). Such dynamics affect commercial businesses and pose a significant challenge when it comes to the supply of basic food and necessary products—essentials for a “better life.” In fact, in many mountain areas, the presence of commercial activities and other basic services is commonly seen by local communities as the foundation of the sustainability of the mountain population.

2. Methodology

This study examines the projected dynamics of commercial entrepreneurship in the mountain regions of Europe, with a focus on commercial activities. The analysis and forecasting period covers the years 2021–2035. The database consists of 28 statistical indicators specific to mountain commercial entrepreneurship, with their definitions available in the Eurostat or published by the authors at the following address [

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14713867].

The research includes 15 European countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden. Data extracted form Eurostat were processed in SPSS and Excel, models being ARIMA (0,0,0).

The analysis focuses on:

- evaluating the number of enterprises and the growth/decline rate in the mountain commercial sector;

- monitoring employment in newly established enterprises and those ceasing activity;

- identifying high-potential firms and medium-term survival rates;

- comparisons between countries to determine common patterns or regional particularities.

The results will provide a comprehensive view of the sustainability of mountain entrepreneurship in trade, with implications for economic policies tailored to the specifics of mountain areas.

2.1. Description of the Context and the Aim of the Analysis

Mountain commercial entrepreneurship faces distinct challenges arising from the characteristics of mountain regions. Reduced accessibility and underdeveloped infrastructure represent some of the main obstacles, while market volatility remains a constant factor significantly influencing this sector. Additionally, regional economic conditions, often unstable, contribute to an uncertain climate, directly impacting commercial activities in these areas. Nevertheless, the mountain commercial entrepreneurship sector remains crucial for local economic development. By creating jobs, supporting economic activities, and contributing to the preservation of local traditions, mountain trade plays a significant role in maintaining economic cohesion in geographically disadvantaged areas. Furthermore, the complexity of economic activities in trade is marked by high business birth and closure rates, making the analysis of these economic fluctuations an important topic.

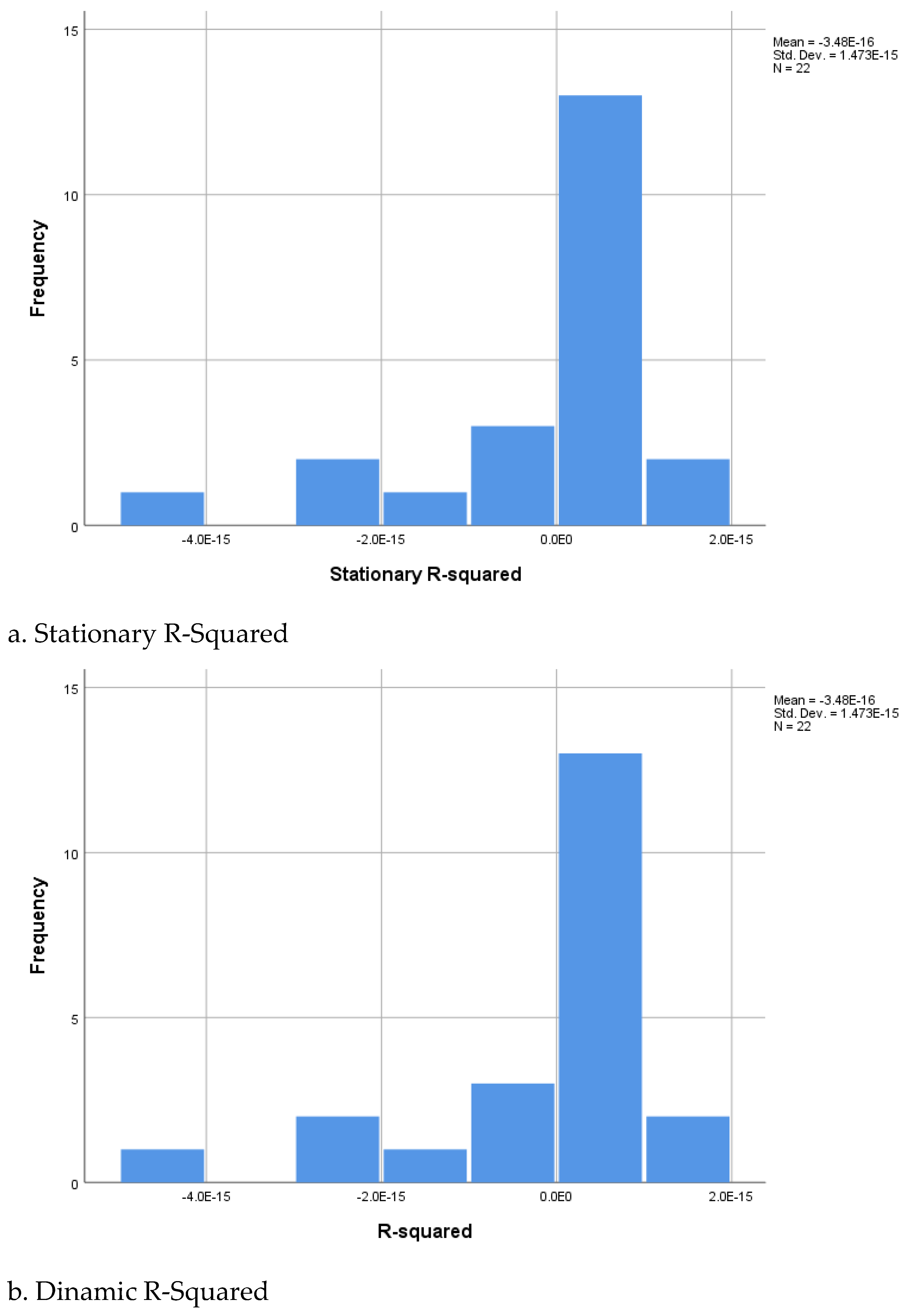

The main aim of this analysis is to assess the performance of various forecasting models used to estimate relevant economic indicators for mountain commercial entrepreneurship. These include the birth and death rates of enterprises, survival rates, and developments regarding forced employment. The research utilized an extensive set of economic data reflecting the dynamics of mountain businesses, considering aspects related to the number of new businesses, survival rates, as well as developments in forced employment and other relevant economic factors for the mountain trade sector.

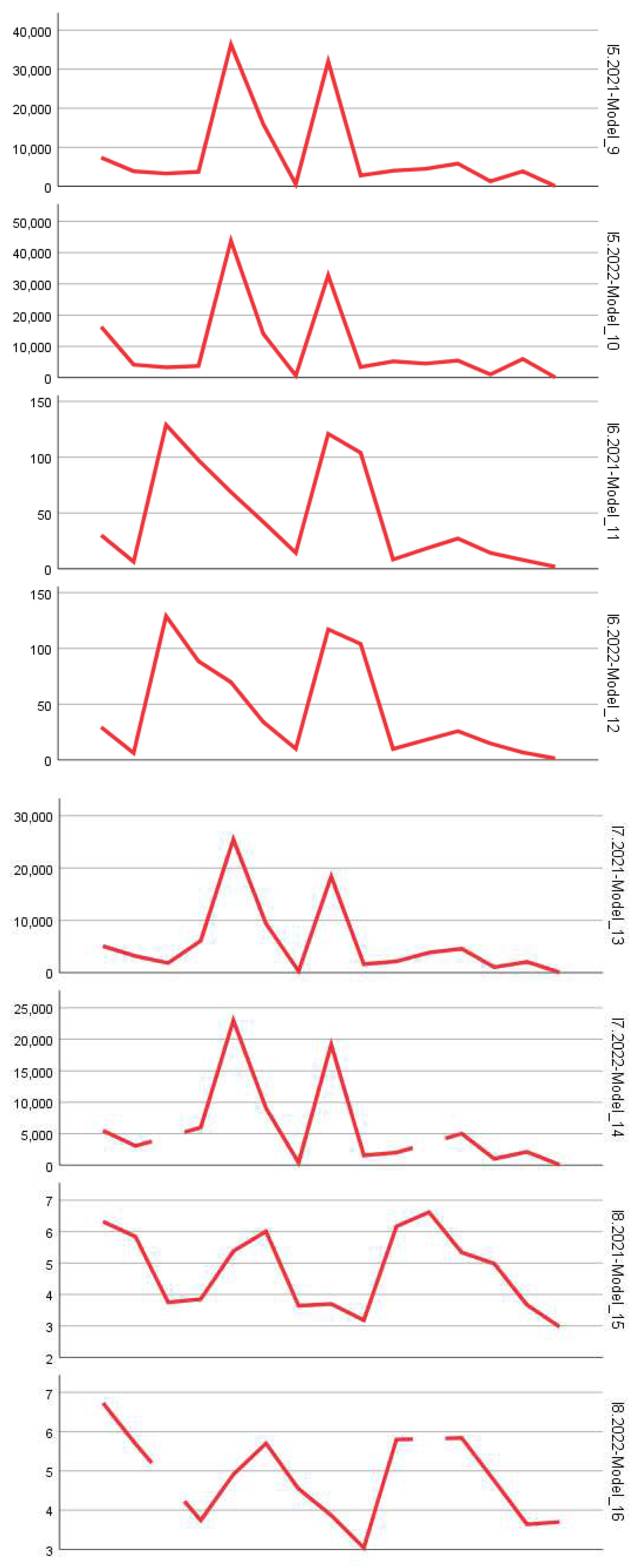

The data included in this analysis are divided into two main categories: I1-I17 (

Table 1 and

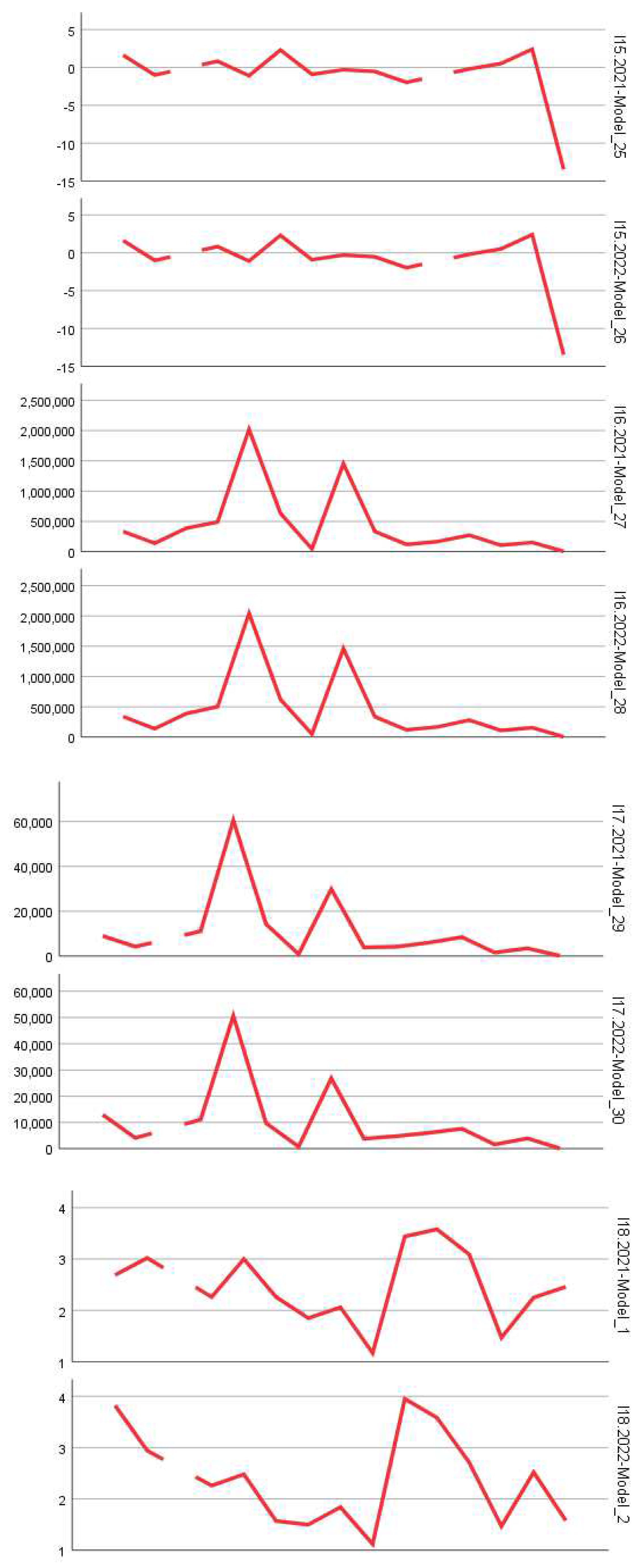

Figure 1), indicators reflecting the structure and dynamics of mountain enterprises, such as the number of enterprises, establishment and closure rates, and I18-I28 (

Table 2 and

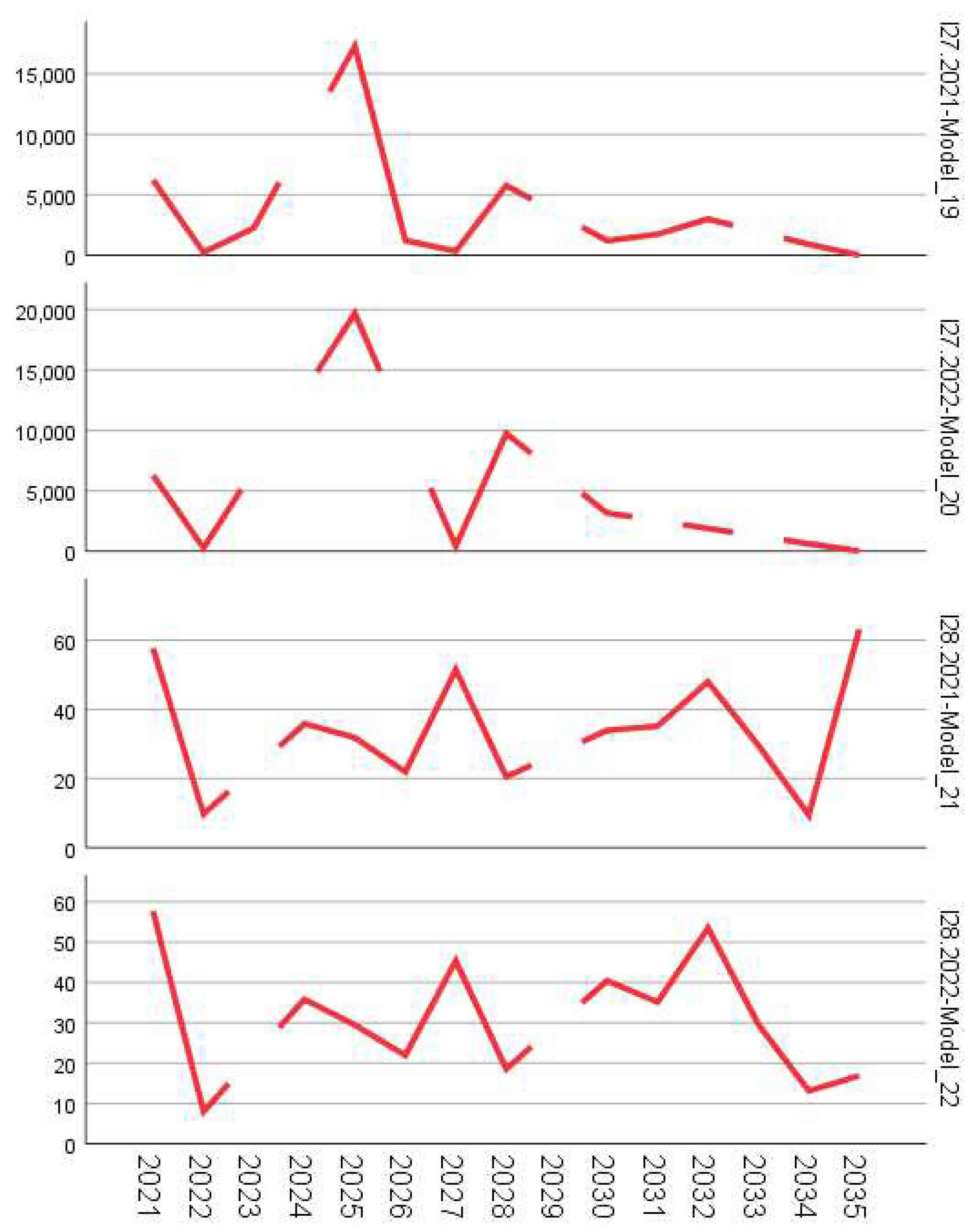

Figure 2), indicators related to labor force in these enterprises, including employment in newly established firms and those that have closed. The analysis of this data was carried out using advanced statistical techniques including RMSE, MAPE, MaxAPE, MAE, MaxAE, and normalized BIC, essential statistics for evaluating the accuracy of economic forecasts and identifying potential errors in estimation models.

The analysis of mountain commercial entrepreneurship is based on a set of structural and dynamic indicators, calculated according to Eurostat methodology. The data come from official registers of enterprises active in mountain areas, with trade as their primary activity. The process of data collection and processing involves the following steps:

1. Enterprise selection – identifying units based in mountain areas and with the corresponding CAEN code for trade.

2. Indicator calculation – applying standardized formulas for each indicator, with correlations between the number of enterprises, employees, and survival rates.

3. Dynamics analysis – year-on-year comparisons to highlight trends in growth, decline, or stability in the sector.

4. Interpretation of results – correlating data with economic and geographical factors specific to mountain areas.

2.2. Justification for the Choice of Indicators

Each of the indicators selected in this analysis plays a key role in understanding the dynamics of mountain commercial entrepreneurship. Some fluctuations worth mentioning are as follows:

- I1: the number of enterprises is a significant indicator for understanding the market size and volume of economic activities in this sector, providing essential information for evaluating the evolution of the local economy. It directly reflects capital flows and changes in consumer behavior, thus indicating the health of the commercial sector.

- I2: business births provide relevant information about trends in new business creation, an essential indicator in evaluating government support or the effects of local economic policies. These trends can be influenced by external factors such as government support programs or incentives for developing local businesses.

- I5: business deaths represent a crucial indicator reflecting the difficulties faced by mountain entrepreneurs in sustaining businesses in the long term. Business closures, often caused by economic crises or market condition changes, are a harsh reality in the mountain entrepreneurial sector and highlight the need for adaptability and support. Analyzing this indicator is essential for evaluating the impact of implemented economic measures and for understanding the success of support policies.

These indicators are closely interconnected and reflect not only the evolution of the sector’s health but also the effects of economic policies, available infrastructure, and entrepreneurs’ adaptability to economic changes. The dynamics of these indicators can offer a comprehensive view of the stability and sustainability of mountain entrepreneurship in trade.

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

2.3.1. Data Collection and Processing

For this analysis, data were collected from Eurostat, sourced from a wide range of official statistical sources, including national and regional economic registers, as well as estimates provided by research institutions and local authorities. These data sources provide a solid foundation for understanding economic trends and fluctuations in entrepreneurial activity in mountain regions. After data collection, a rigorous cleaning process was applied to eliminate any apparent errors or missing data, an essential step to ensure the quality of the analysis.

During the data cleaning process, imputation techniques were applied to handle missing values, aiming to maintain data integrity and avoid distorting results. Additionally, measurement units were standardized to ensure consistency and comparability of data from various sources. These data processing techniques are essential for obtaining a clean and consistent dataset that can be used in advanced statistical analysis.

2.3.2. Forecasting Methods

To forecast economic indicators, multiple regression models were used, adapted based on historical data and observed seasonal variations in mountain trade. Multiple regression models capture the complex relationships between variables, thus providing more precise forecasts regarding economic developments in this sector. Additionally, time series forecasting models were integrated, which are suitable for economic data displaying seasonal or cyclical trends. These models were crucial for generating short- and long-term forecasts and for evaluating potential developments in mountain entrepreneurship in trade under current market conditions.

Furthermore, forecasting models that include adjustments for seasonality and external economic fluctuations were implemented, allowing for better capture of the dynamics of the mountain economy. By using advanced forecasting techniques, the aim was to provide a detailed and accurate picture of potential economic scenarios based on historical data and observed trends in the sector.

2.3.3. Forecast Error Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of forecasting models is an essential step in validating their accuracy. For this purpose, a series of error evaluation statistics were used, including RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), MaxAPE (Maximum Absolute Percentage Error), and MAE (Mean Absolute Error). These statistics help identify errors and evaluate the performance of models in relation to observed data.

RMSE represents the square root of the average squared difference between the forecasted and observed values, while MAPE expresses the mean absolute error in percentage terms. Both statistics are essential for understanding the accuracy of forecasts and for identifying areas where forecasting models can be improved. MaxAPE and MaxAE are also important as they allow for the identification of the largest errors, providing valuable information for improving model performance.

2.3.4. Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

After applying the forecasting models, data validation analyses were performed by testing the models on separate datasets to ensure that the results obtained are accurate and stable. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to assess how the forecast varies with small changes in economic conditions, allowing us to observe possible extreme scenarios in which the models might produce incorrect results. These sensitivity analyses are essential for evaluating the robustness of the models and for identifying conditions under which they may no longer function correctly.

3. Results

The forecasting analysis conducted on mountain entrepreneurship in commerce yielded several results regarding the mountain indicators from Eurostat, concerning the dynamics of enterprises, the impact on employment, high-growth enterprises, and so on.

- Enterprise dynamics

The total number of active enterprises in mountain commerce (I1) shows a slight increase in the reference year. Newborn enterprises (I2) represent certain units, reflecting a birth rate (I13). Of these, some enterprises survive after three years (I7), resulting in a survival rate (I9).

Regarding the average size of enterprises, newly established ones (I3) typically have a few employees, while those that close down (I4) leave behind additional employees. The business mortality rate (I14) is at a certain level, and business churn (I12) indicates moderate dynamics within the sector.

- Impact on employment

Total employment in mountain commerce (I16) totals a certain number of people, some of whom work in newly established enterprises (I17). These contribute to total employment (I18). Enterprises that close (I19) reduce the workforce by other employees, representing a certain percentage of the total number of employees (I22).

Enterprises that survive for three years (I20) demonstrate an increase in employment compared to their founding year (I24), confirming the sustainability of some mountain businesses. Their proportion within the total number of active enterprises (I8) represents a high percentage, and their share of employment (I23) aligns with indicator I8.

- High-growth enterprises

The number of high-growth enterprises (I10) stands at a certain value, representing a certain percentage of all firms with over 10 employees (I11). This result highlights the presence of competitive businesses capable of generating significant employment.

3.1. General Performance of Forecasting Models for Indicators I1-I17

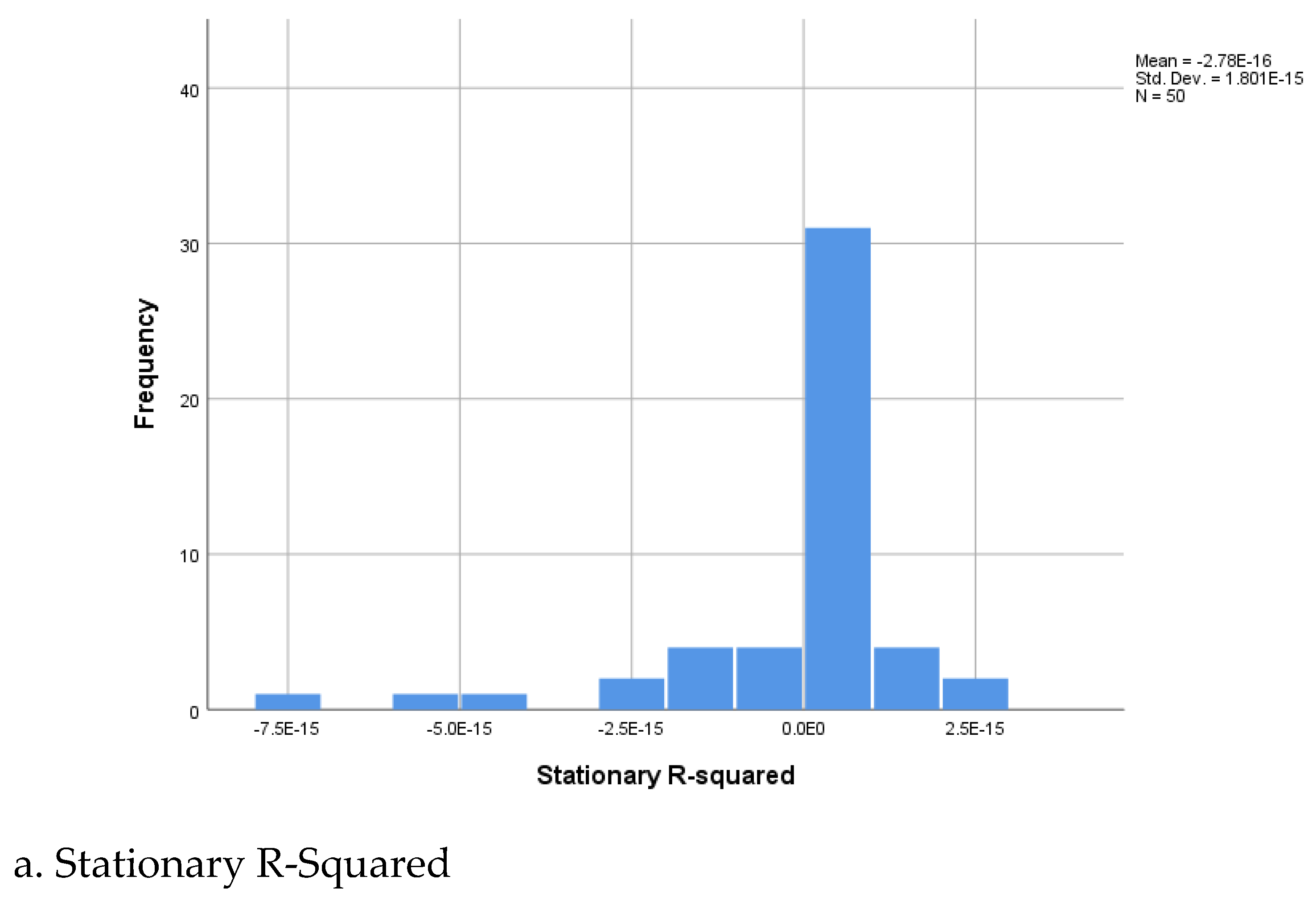

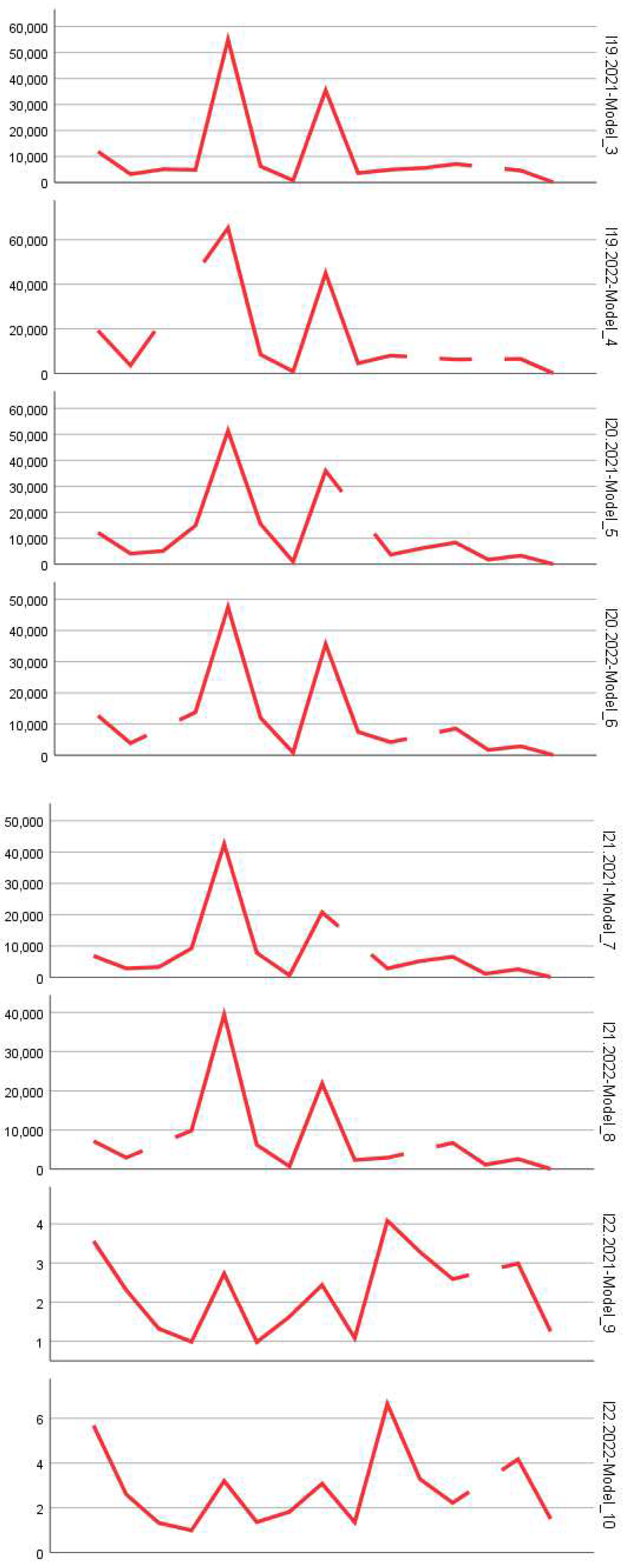

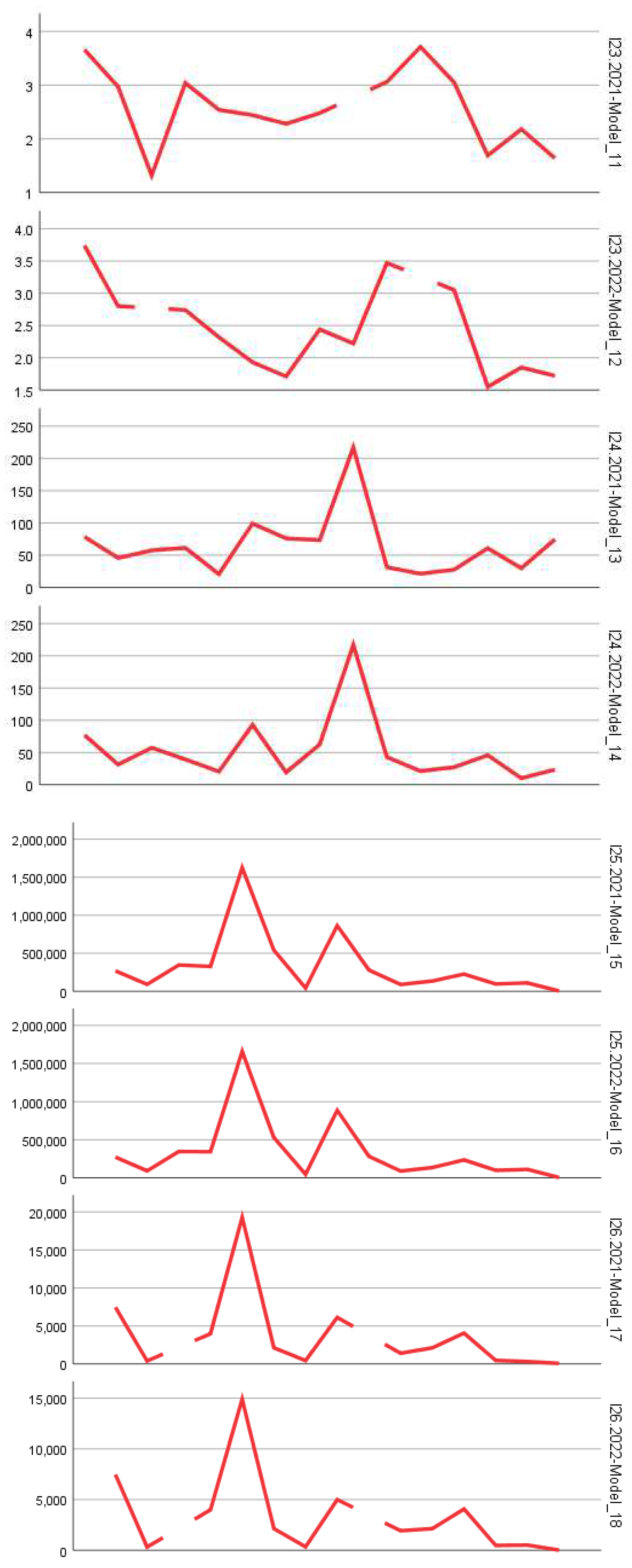

In the economic analysis of mountain entrepreneurship in commerce, the forecasting models applied to indicators I1-I17 (

Table 1,

Figure 1 and

Figure 3) demonstrated variable performance, depending on the characteristics of each indicator and its complexity within the mountain economic context. The analyzed indicators revealed various aspects of the performance of mountain enterprises, including birth and death rates, long-term survival, employment rates, and other aspects related to the sector’s evolution.

In particular, to evaluate the performance of the forecasting models, several adjustment statistics were considered, with the most relevant being RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), and MaxAPE (Maximum Absolute Percentage Error).

The values obtained for RMSE showed a significant margin of error, with an average value of 47,764.948 and a standard deviation of 134,886.773. This indicates that the forecasts were quite dispersed from the actual values, with significant errors in indicators such as I1 and I2, which refer to the trends in the establishment of businesses in mountain regions. These fluctuations were largely caused by unstable economic conditions in certain areas, where environmental factors and economic resources had a direct influence on the number of new enterprises.

MAPE had an average value of 554.630, with an extreme range between 0.000 and 2582.355, suggesting a relatively high error in forecasting economic activity. This was influenced by significant exogenous factors, such as frequent changes in fiscal policy or government support in mountain regions, leading to unpredictable economic fluctuations. Additionally, some mountain regions faced difficult natural conditions that impacted local businesses.

MaxAPE reached a maximum value of 5741.942, indicating that the forecasting models were influenced by exceptional economic events or rapid changes in the local context. These large errors are characteristic of mountain economies, where business success can depend heavily on unpredictable factors such as weather conditions or fluctuations in tourism demand, which are difficult to predict in the long term.

Despite the significant errors, the forecasting models provided valuable insights into the economic trends of mountain entrepreneurship in commerce. Indicators I1 and I2 reflected a positive trend in the establishment of new businesses in certain mountain areas. This suggests that, in the short term, the business environment in these regions was favorable, with government support and access to EU funds having a significant impact on the development of mountain enterprises.

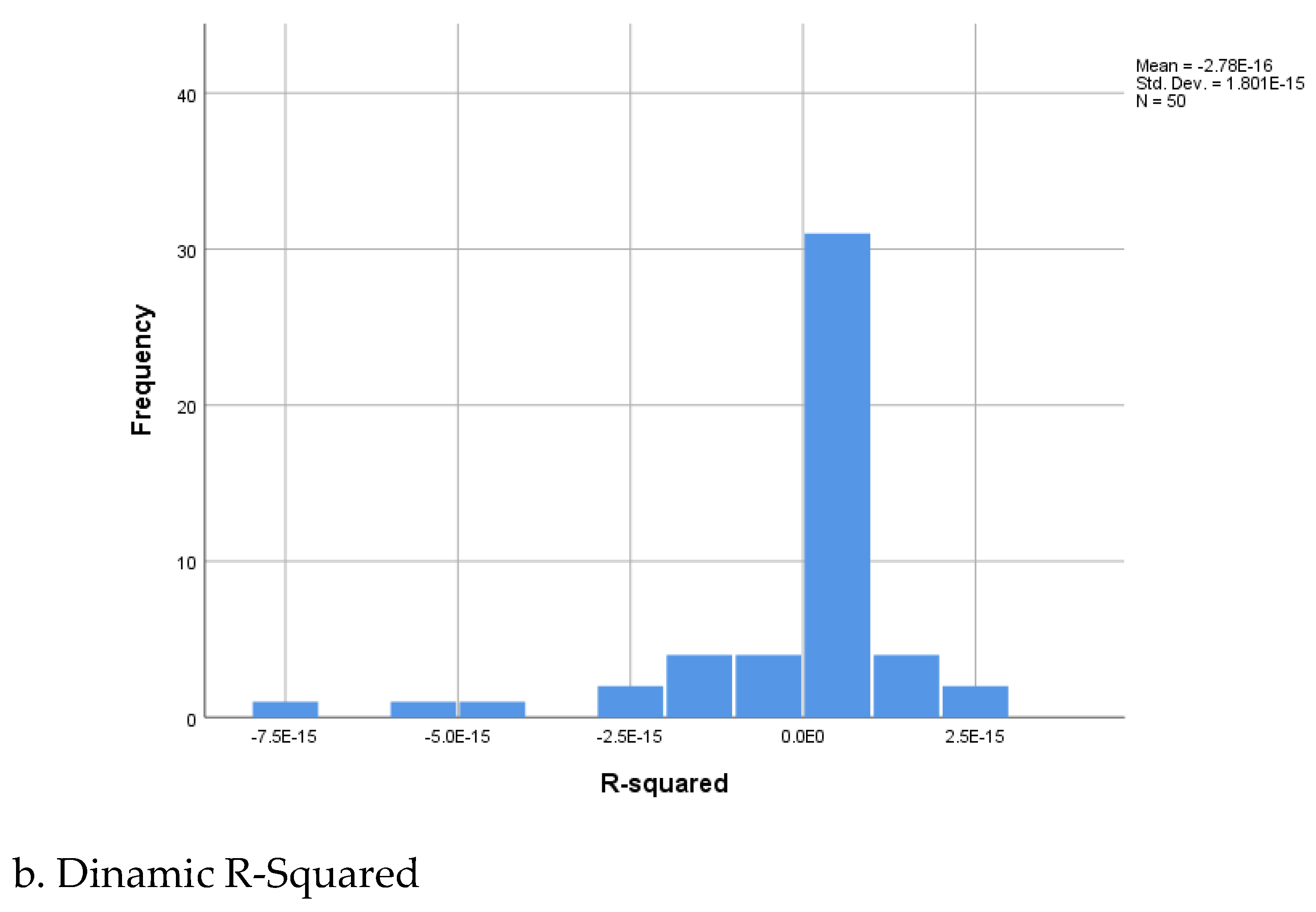

3.2. Forecasting Model Performance for Indicators I18-I28

The forecasting models for indicators I18-I28 (

Table 2,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), which focus on employment in mountain enterprises and their growth rates, performed better than those for indicators I1-I17. They reflected a more stable trend and had a lower average RMSE value of 43,479.839 compared to the previous section’s values. This suggests greater accuracy in forecasting employment and employee evolution in the mountain entrepreneurship sector in commerce.

MAE (Mean Absolute Error) had an average value of 28,110.788, indicating more precise forecasting regarding the number of employees in the mountain sector. This improved performance can be explained by greater labor market stability in mountain regions, where tourism and the trade of local products are essential factors that contribute to maintaining a steady number of jobs.

One of the most important indicators was I10 and I11. The forecasting models captured a significant increase in the number of high-growth enterprises, particularly in mountain regions with well-developed infrastructure and a favorable economic environment. The estimated growth rate was 24.931%, which shows that there are accelerated development opportunities in certain sectors of the mountain economy. These opportunities were supported by European funding programs, tax incentives for small businesses, and increasing demand for traditional products and tourist services.

Values for MaxAPE for these indicators were high, reaching 7944.070, indicating significant uncertainty in forecasting this type of growth. This can be explained by factors such as market instability and fluctuations in consumer demand in mountain regions, which can vary significantly depending on the tourist season or weather conditions.

Indicators I7 and I9 showed a positive trend regarding the long-term resilience of mountain enterprises. The forecast showed that approximately 28.3% of newly established enterprises managed to sustain their activity for at least 3 years. This suggests that, despite economic challenges and risks associated with the mountain environment, many new businesses have managed to survive. This is quite a good performance for mountain entrepreneurship in commerce, given its seasonal nature and dependence on external factors such as tourism and weather conditions.

Regarding employment, the forecasting models showed significant growth in the number of employees in enterprises that survived in the long term. Indicator I20 had an average value of 2,543 people, indicating workforce consolidation in these enterprises. Compared to those that failed to survive, the number of employees was significantly higher in those that surpassed the critical three-year period.

However, forecasting errors were significant. MaxAPE reached 8921.972, reflecting uncertainties in forecasting long-term enterprise behavior, influenced by unpredictable factors such as changes in consumer demand or weather conditions. These external variables have a direct impact on business activity and employment decisions in mountain enterprises.

3.3. Analysis of Fluctuation Indicators and Business Turnover Rate

Indicators I12 and I13 are relevant for understanding the market dynamics and business environment in mountain areas. Their forecast revealed a continuously changing economic sector, with a fluctuation rate of about 24% and a new enterprise birth rate of 21%. This suggests a constant activity, with regular business turnover, within a context of sustainable development, but with a significant degree of economic instability.

However, fluctuation rates were variable, and MaxAE was 1.358, indicating that forecasts were influenced by unforeseen factors. External factors such as changes in fiscal regulations and fluctuations in demand for products and services contributed to this uncertainty.

The forecasting models for economic indicators in the mountain entrepreneurship sector in commerce had variable performance, with significant errors in some cases, but they also provided valuable results for analyzing economic trends in mountain regions. While some forecasts were more accurate than others, forecasting errors were inevitable due to market instability, unpredictable economic factors, and other external variables. Nevertheless, the models provided valuable information about the behavior of mountain enterprises, indicating the general directions of the economy in these areas.

The results obtained from the forecasting analysis and the specific economic indicators of mountain entrepreneurship in commerce provided several important perspectives for the future of this sector. Based on the data collected and the forecasting techniques applied, the following directions can be concretized:

- Stability and volatility of mountain entrepreneurship

In general, mountain entrepreneurship in commerce is a sector with relatively short-term stability, but it is extremely vulnerable to external economic fluctuations, political crises, and climate change. The forecasting models showed that the establishment of new enterprises (I2) is sustainable in mountain regions, but business closures (I5) and the uncertainty regarding job retention are factors that could negatively influence the future of this sector. Economic support measures and policies protecting mountain entrepreneurship in commerce are essential for maintaining a stable economy in these regions.

- Efficiency of support strategies for mountain enterprises

The analysis highlighted that government support and economic policies to encourage the establishment of businesses in mountain areas are effective in the short term. However, these policies must be flexible and adaptable, given that business closures and forced migration of the workforce are frequent phenomena in mountain areas, affecting business viability in the long term. It was also found that to support the development of this sector, it is essential to diversify the types of support, including both financial measures and those aimed at professional training for the local population and improving regional infrastructure.

- Importance of adapting to external changes

Another essential point identified in our analysis is the close link between the evolution of mountain entrepreneurship and external economic and climatic changes. Development projects must consider these external variables to minimize their negative impact. In this regard, it is recommended to implement adaptive strategies that include continuous monitoring of economic and social indicators and rapid adjustment of support policies according to the local and regional context.

- Limitations and future research directions

Although the analysis provided valuable insights, it faces some limitations. Firstly, the forecasting models did not fully capture the complexity of external factors influencing mountain entrepreneurship in commerce. Also, the data available for certain mountain regions was insufficient, which limited the ability to generalize the results. In the future, it is recommended to expand the research to include a broader set of data and analyze the impact of more specific factors, such as environmental policies, tourist infrastructure, or sustainable development initiatives.

Mountain commercial enterprises exhibit moderate dynamics, with a survival rate higher than the national average in some subzones. Access difficulties and seasonality affect the mortality rate, but enterprises that manage to persist contribute significantly to employment. Support policies could stimulate growth for high-potential businesses.

4. Conclusions

Mountain entrepreneurship in commerce presents itself as an economic sector with significant potential for growth and development, but it faces distinct structural and economic challenges. In the analysis conducted, the forecasting models applied to the economic indicators showed variable performance, highlighting both the opportunities and uncertainties that mountain businesses face. The birth and death rates of businesses, as well as survival rates, are crucial indicators in understanding the behavior of the mountain sector. The forecasting models provided a clear picture of general economic trends, as well as the impact of external factors on them.

An essential aspect highlighted by the research findings is the importance of exogenous factors, such as fiscal changes and external economic fluctuations, which have influenced the performance of mountain businesses and their ability to predict economic developments. These external variables had a direct impact on business survival rates and the dynamics of the labor market in mountainous regions. The forecasting models that focused on employment and workforce trends yielded more stable results, indicating a positive trend regarding long-term employment in mountain businesses, especially in regions where infrastructure and government support are more developed.

At the same time, the analysis highlighted that the mountain commerce sector has a high degree of fluctuation, with a constant business dynamic in which a significant number of enterprises close or restructure. These fluctuations can be explained by the economic instability in mountainous regions, as well as by the seasonal impact of tourism on the demand for products and services. Despite these challenges, mountainous regions with well-developed infrastructure and favorable economic policies have presented significant opportunities for fast-growing businesses, suggesting that there is potential for accelerated development in certain areas.

In conclusion, the research emphasizes the importance of adjusting economic policies and government support in mountainous regions to foster the sustainable development of commerce entrepreneurship. It is essential that forecasting models continue to be improved, considering the significant errors and external economic uncertainties, in order to provide a more accurate picture of economic developments in these areas. Despite the limitations, the analysis provides a solid foundation for future research and support policies aimed at the mountain commerce entrepreneurship sector.

Data Availability Statement

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized artificial intelligence tools for assistance in statistical analysis and data interpretation. Following this, the authors rigorously reviewed, validated, and refined all results, ensuring accuracy and coherence. The final content reflects the authors’ independent analysis, critical revisions, and scholarly judgment. The authors assume full responsibility for the integrity and originality of the published work.

References

- Clerici, M. A. (2025). Mountain areas and the growing scarcity of essential services: The evolution of retail business density in mountain municipalities in Lombardy (Italy), 2001–2021. European Countryside, 17(1), 47–69. [CrossRef]

- ESPON. (2014). TOWN: Small and medium-sized towns in their functional territorial context: Final report. Luxembourg: ESPON.

- https://archive.espon.eu/programme/projects/espon2013/applied-research/town-%E2%80%93-small-and-medium-sized-towns.

- ESPON. (2017). PROFECY-Processes, features and cycles of inner peripheries in Europe: Final report. Luxembourg: ESPON. Retrieved from https://www.espon.

- ESPON. (2018). Alps2050: Common spatial perspectives for the Alpine area: Towards a common vision. Final report. Luxembourg: ESPON.

- https://www.espon.eu/Alps2050.

- European Commission (EC). (2020). Territorial Agenda 2030 − A future for all places.

- https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/brochures/2021/territorialagenda-2030-a-future-for-all-places.

- European Commission (EC). (2021). A long-term vision for the EU’s rural areas: Towards stronger, connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040 (COM 2021/345 final). Brussels: EC.

- Eurostat (2025). Business demography and high growth enterprises by NACE Rev. 2 activity and other typologies [urt_bd_hgn__custom_15325082].

- Fassmann, H. , Rauhut, D., da Costa, E. M., & Humer, A. (Eds.). (2015). Services of general interest and territorial cohesion: European perspectives and national insights. V&R Unipress GmbH.

- Hüller, S.; Heiny, J.; Leonhäuser, I.-U. Linking agricultural food production and rural tourism in the Kazbegi district – A qualitative study. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.A.; Woods, M.; Cejudo, E. The LEADER Initiative has been a Victim of Its Own Success. The Decline of the Bottom-Up Approach in Rural Development Programmes. The Cases of Wales and Andalusia. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 56, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicula, A.-S.; Georgescu, V.Ț.-B.; Nicula, E.-A.; Domnița, M.; Păcurar, B.-N. Seeking Economic Balance: Spatial Analysis of the Interaction Between Smart Specialisation and Diversification in Romanian Mountain Areas. 68, 57. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M. The impact of entrepreneurship of farmers on agriculture and rural economic growth: Innovation-driven perspective. Innov. Green Dev. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panciszko-Szweda, B. Short Food Supply Chains as a policy tool for smart and sustainable rural development in the European Union. Stud. Ecol. et Bioethicae 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. , Dassie, W., & Christy, R. (2004). Entrepreneurship and small business development as a rural development strategy. Journal of Rural Social Sciences, 20(2), Article 1. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol20/iss2/1.

- Salukvadze, G.; Michel, A.H.; Backhaus, N.; Gugushvili, T.; Dolbaia, T. From Tradition to Innovation: The Pioneers of Mountain Entrepreneurship in the Lesser Caucasus. Mt. Res. Dev. 2024, 44, R14–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salukvadze, G.; Michel, A.H.; Backhaus, N.; Gugushvili, T.; Dolbaia, T. From Tradition to Innovation: The Pioneers of Mountain Entrepreneurship in the Lesser Caucasus. Mt. Res. Dev. 2024, 44, R14–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stielike, J.M. Securing access to Services of General Interest in remote regions – ethical perspectives and practical implications for spatial planning. disP - Plan. Rev. 2024, 60, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARURE [Save Rural Retail]. (2021). Good practices handbook. Retrieved from https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1623261108.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).