Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

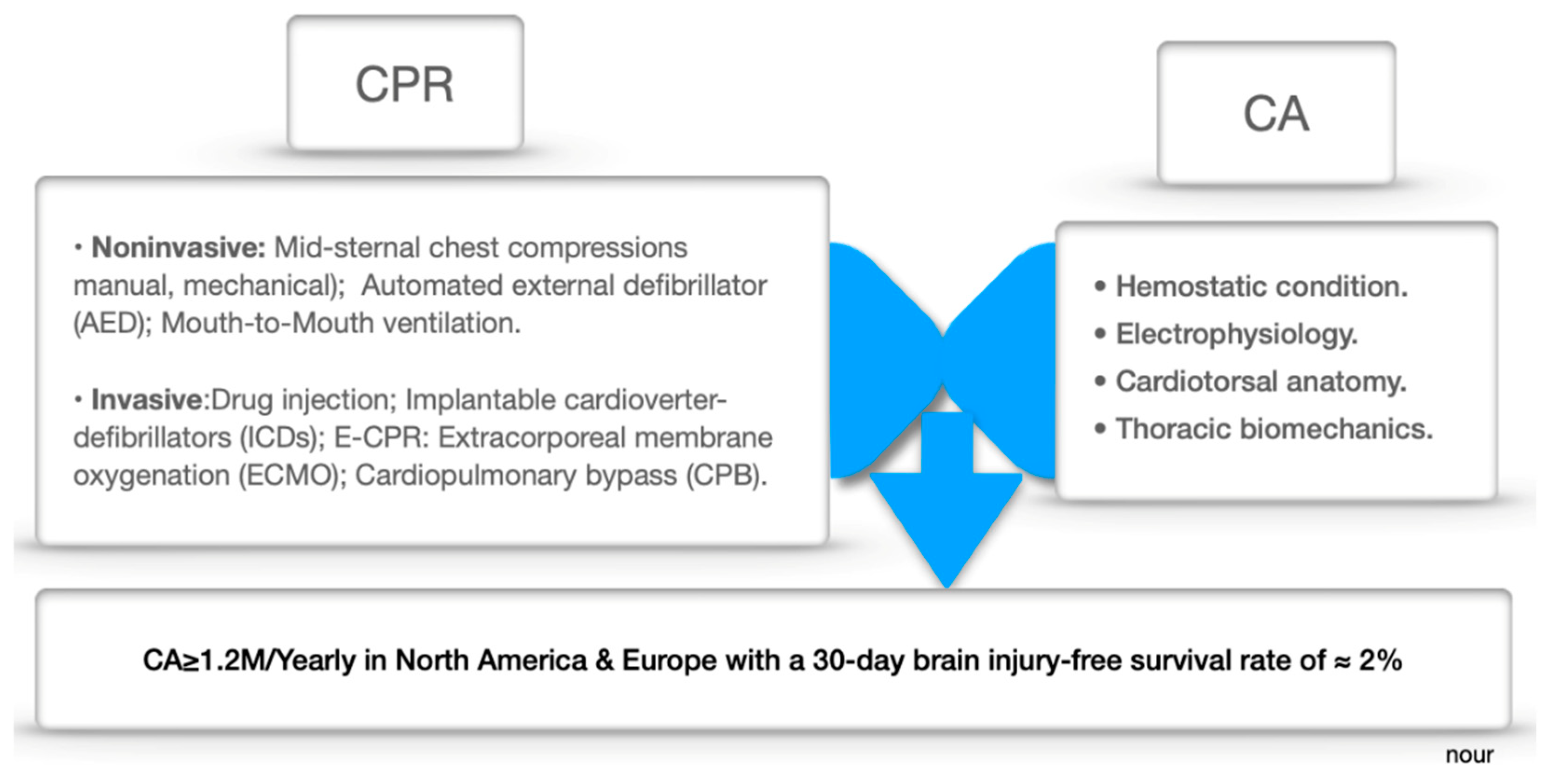

1. Introduction

In-Depth Glance at CA

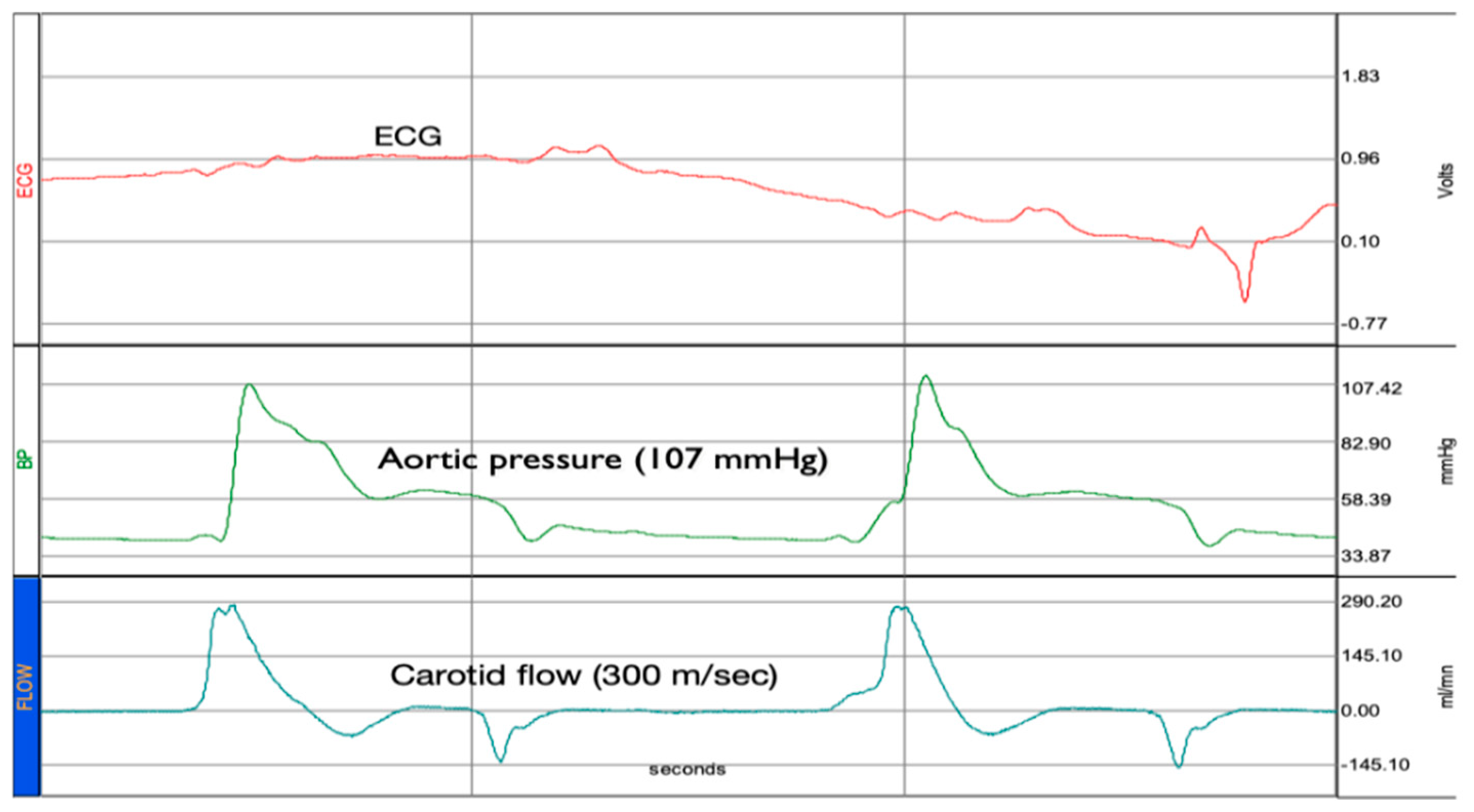

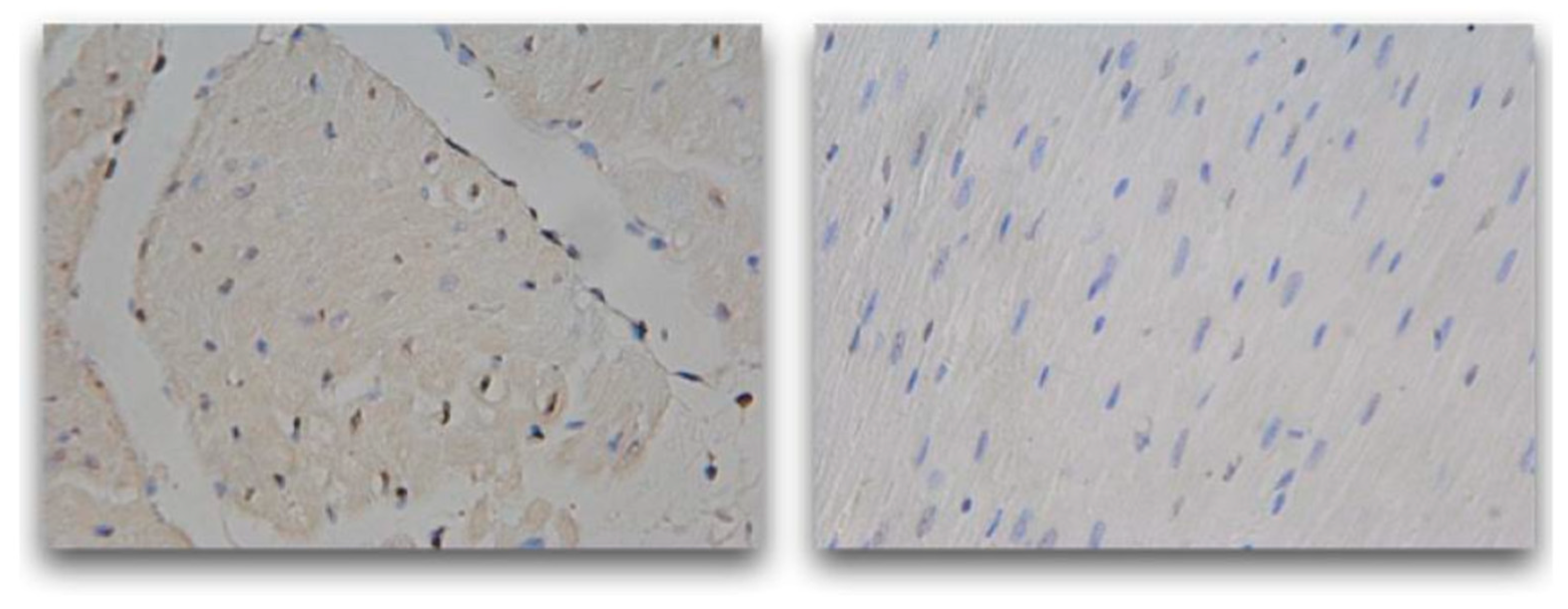

2. Results

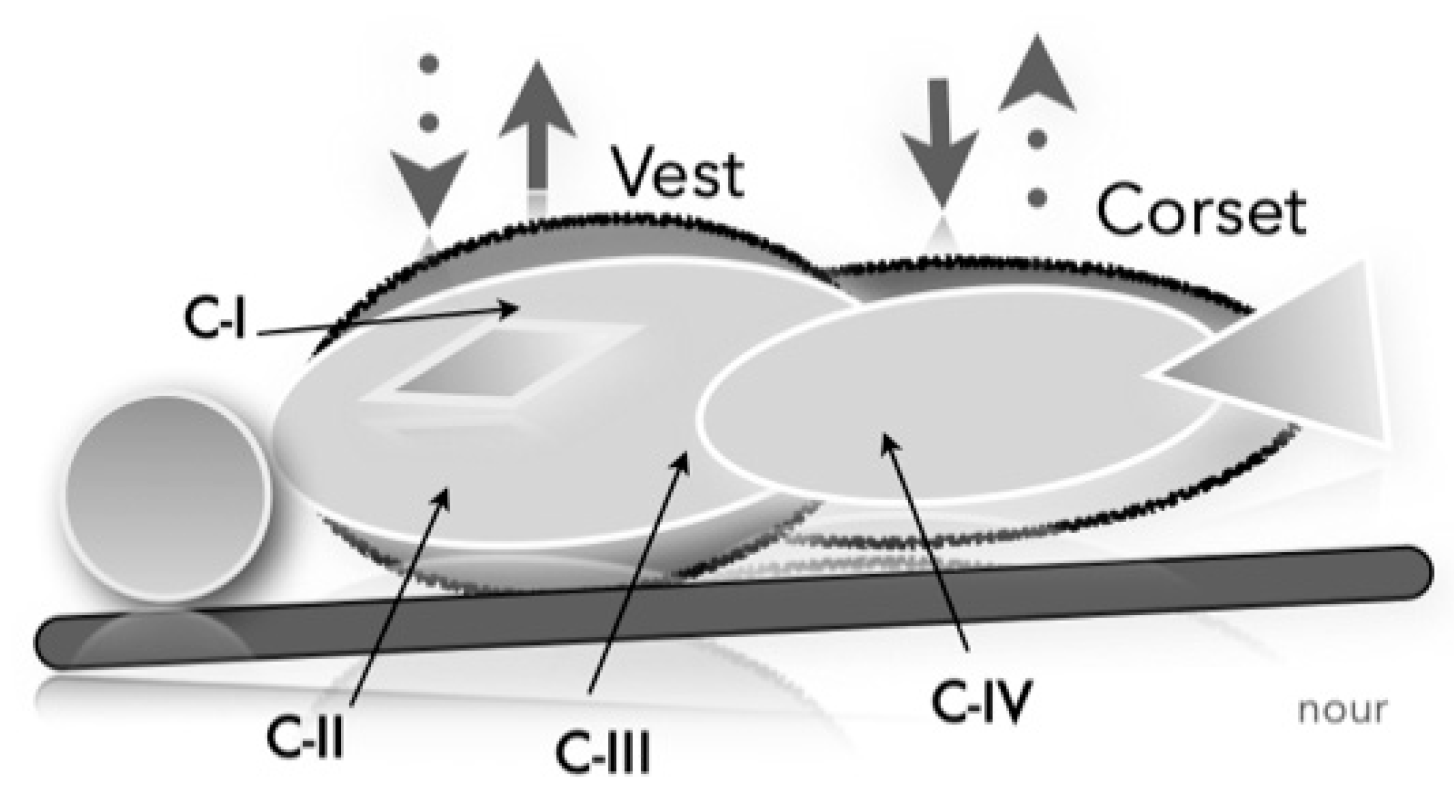

Novel Concept

STUDIES

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA | Cardiac arrest |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| AED | Automated external defibrillators |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter defibrillators |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| OHCA | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| ROSC | Return of spontaneous circulation |

| ESS | Endothelial shear stress |

| CFR | Circulatory flow restoration |

| MCS | Mechanical circulatory support |

| bpm | beats per minute |

| BV | Blood volume |

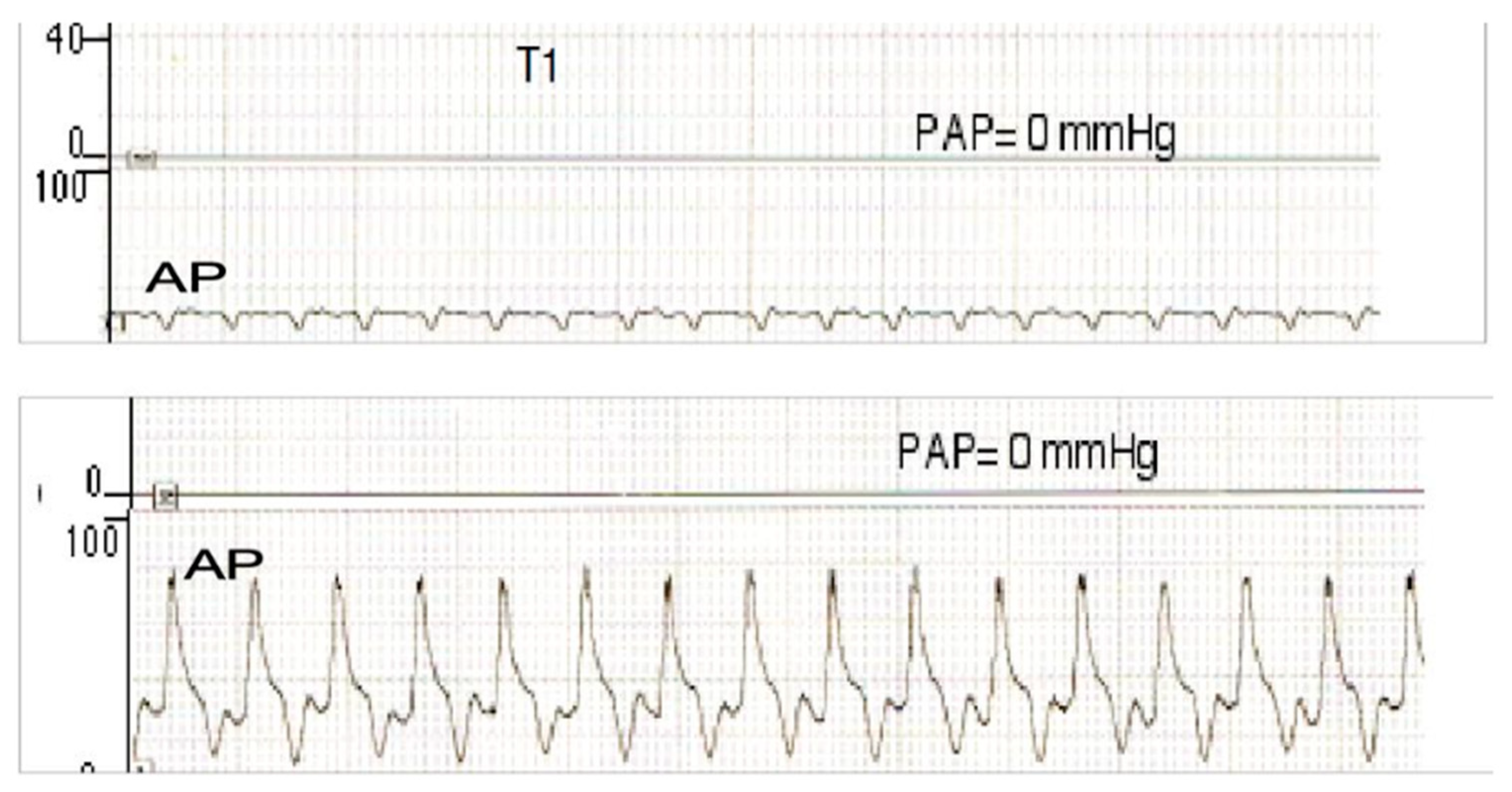

| AP | Arterial pressure |

| PA | Pulmonary artery |

| PAP | Pulmonary artery pressure |

| RV | Right ventricle |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| IV | Intravenous |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CO | Cardiac output |

| CI | Cardiac index |

References

- Sandroni, C.; Cronberg, T.; Sekhon, M. Brain injury after cardiac arrest: pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toy, J.; Friend, L.; Wilhelm, K.; Kim, M.; Gahm, C.; Panchal, A.R.; Dillon, D.; Donofrio-Odmann, J.; Montroy, J.C.; Gausche-Hill, M.; Bosson, N.; Coute, R.; Schlesinger, S.; Menegazzi, J. Evaluating the current breadth of randomized control trials on cardiac arrest: A scoping review. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2024, 5, e13334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, H.T.; Low, L.S.; Kern, K.B. Current Approaches to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2015, 40, 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peberdy, M.A.; Gluck, J.A.; Ornato, J.P.; Bermudez, C.A.; Griffin, R.E.; Kasirajan, V.; Kerber, R.E.; Lewis, E.F.; Link, M.S.; Miller, C.; Teuteberg, J.J.; Thiagarajan, R.; Weiss, R.M.; O’Neil, B. American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative, and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular Diseases in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults and Children With Mechanical Circulatory Support: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017, 135, e1115–e1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, P.C.M.; de Graaf, C.; Tan, H.L.; Hulleman, M.; Koster, R.W.; Beesems, S.G.; Blom, M.T. Transfer of essential AED information to treating hospital (TREAT). Resuscitation. 2020, 149, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, C.D.; Koster, R.W. Chest compression pauses during defibrillation attempts. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016, 22, 206–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, J.A.; Doeleman, L.C.; Loer, S.A.; Koster, R.W.; van Schuppen, H.; Schober, P. Ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A narrative review. Resuscitation. 2024, 203, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, A.; Hiraide, A.; Shinozaki, T.; Shibata, N.; Miyamoto, K.; Tamura, S.; Inoue, S. Impact of epinephrine on neurological outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after automated external defibrillator use in Japan. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.B.; Mariani, J.A.; Kistler, P.M.; Patel, H.; Voskoboinik, A. Transvenous versus subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillators in young cardiac arrest survivors. Intern Med J. 2023, 53, 1956–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.L.; Gauvreau, K.; Alexander, P.M.A.; Teele, S.A.; Fynn-Thompson, F.; Lasa, J.J.; Bembea, M.; Thiagarajan, R.R.; American Heart Association’s (AHA) Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-R) Investigators. Higher Survival With the Use of Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Compared With Conventional Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Children Following Cardiac Surgery: Results of an Analysis of the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Registry. Crit Care Med. 2024, 52, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamoto, K.; Tanno, K.; Takeyama, Y.; Asai, Y. Successful treatment of severe accidental hypothermia with cardiac arrest for a long time using cardiopulmonary bypass - report of a case. Int J Emerg Med. 2012, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zong, Q.; Chen, S.; Lv, C. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubertsson, S.; Lindgren, E.; Smekal, D.; Östlund, O.; Silfverstolpe, J.; Lichtveld, R.A.; Boomars, R.; Ahlstedt, B.; Skoog, G.; Kastberg, R.; Halliwell, D.; Box, M.; Herlitz, J.; Karlsten, R. Mechanical chest compressions and simultaneous defibrillation vs conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the LINC randomized trial. JAMA. 2014, 311, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Avishay, D.M.; Jones, C.R.; Shaikh, J.D.; Kaur, R.; Aljadah, M.; Kichloo, A.; Shiwalkar, N.; Keshavamurthy, S. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 22, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Salcido, D.D.; Menegazzi, J.J. Coronary perfusion pressure and return of spontaneous circulation after prolonged cardiac arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care 2010, 14, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, K.B.; Maltese, M.R.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Steen, PA.; Nysaether, J.B. Anterior-posterior thoracic force-deflection characteristics measured during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: comparison to post-mortem human subject data. Stapp Car Crash J. 2006, 50, 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, A.R.; Bartos, J.A.; Cabañas, J.G.; Donnino, M.W.; Drennan, I.R.; Hirsch, K.G.; Kudenchuk, P.J.; Kurz, M.C.; Lavonas, E.J.; Morley, P;T.; O’Neil, B.J.; Peberdy, M.A.; Rittenberger, J.C.; Rodriguez, A.J.; Sawyer, K.N.; Berg, K.M.; Adult basic and advanced life support writing group. Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020,142(16-suppl-2),S366-S468. [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.M.; Cheng, A.; Panchal, A.R.; Topjian, A.A.; Aziz. K.; Bhanji, F.; Bigham, B.L.; Hirsch, K.G.; Hoover, A.V.; Kurz, M.C.; Levy, A.; Lin, Y.; Magid. D.J.; Mahgoub, M.; Peberdy, M.A.; Rodriguez, A.J.; Sasson. C.; Lavonas, E.J.; Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support, Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support, Neonatal Life Support, and Resuscitation Education Science Writing Groups. Part 7: Systems of Care: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation.2020,142(16_suppl_2),S580-S604. [CrossRef]

- Oeser, C. Cardiac resuscitation: Continuous chest compressions do not improve outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, N.T.; Schilling, R.J. Sudden Cardiac Death and Arrhythmias. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018, 7, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Noronha, S.V.; Sharma, S.; Papadakis, M.; Desai, S.; Whyte, G.; Sheppard, M.N. Aetiology of sudden cardiac death in athletes in the United Kingdom: a pathological study. Heart. 2009, 95, 1409–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, M.S. Mechanically induced sudden death in chest wall impact (commotio cordis). Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003, 82, 175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Uretsky, B.F. Acute ischaemia as a trigger of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2004, 6, D88–D90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.R.; Herman, H.K.; Quigley, P.C.; Shinnick, J.K.; Cundiff, C.A.; Caltharp, S. Shehata, B.M. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (ARVC/D): Review of 16 Pediatric Cases and a Proposal of Modified Pediatric Criteria. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016,37,646-55. [CrossRef]

- Surawicz, B.; Gettes, L.S. Two mechanisms of cardiac arrest produced by potassium. Circ Res. 1963, 12, 415–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, A.J.; Nadkarni, V.; Berg, R.A.; Osmond, M.H.; Wells, G.; Nesbitt, L.; Stiell, I.G.; CanAm Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Investigators. Out-of-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest: an epidemiologic review and assessment of current knowledge. Ann Emerg Med. 2005, 46, 512-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Empel, V.P.; Bertrand, A.T.; Hofstra, L.; Crijns, H.J.; Doevendans, P.A.; De Windt, L.J. Myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2005, 67, 21–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, D.; Rivera, E.J.; Santana, L.F. The life cycle of a capillary: Mechanisms of angiogenesis and rarefaction in microvascular physiology and pathologies. Vascul Pharmacol. 2024, 156, 107393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour. S.; Carbognani, D.; Chachques, J.C. Circulatory flow restoration versus cardiopulmonary resuscitation: new therapeutic approach in sudden cardiac arrest. Artif Organs. 2017,41,356-366.

- Nour, S. Endothelial shear stress enhancements: a potential solution for critically ill Covid-19 patients. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2020, 19, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, S. Preliminary study of pulsatile versus conventional pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass with a new device tested in piglets. Univ. of Paris XI, France. Master’s degree in Surgical Sciences (2003). University of Paris-Saclay, France.

- Nour, S. Shear Stress, Energy losses and Cost: The Resolved Dilemma of Pediatric Heart Lung Machines with a Pulsatile tube. 16th Annual Meeting of The Asian Society For Cardiovascular And Thoracic Surgery. SINGAPORE. 13-16 March 2008.

- Nour, S.; Liu, J.; Dai, G.; Carbognani, D.; Yang, D.; Wu, G.; Wang, Q.; Chachques, J.C. Shear stress, energy losses, and costs: a resolved dilemma of pulsatile cardiac assist devices. Biomed Res Int. 2014, 2014, 651769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, S. Time to Resuscitate Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: The 3R/CPR Refill-Recoil-Rebound. Cardiology and Angiology: An International Journal. 2022, 11, 363–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoungani, G.; Nour, S. Application of Refill, Recoil, Rebound (3R) as a Novel Chest Compression Technique in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; Report of Two Cases. Arch Acad EmergMed. 2025, 13, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, H.J. Subdiaphragmatic pressure to expel water from the lungs of drowning persons. Ann Emerg Med. 1981, 10, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Pearson/Addison-Wesley, USA, 2005. ISBN 0805390499.

- Nour, S.; Zhensheng, Z.; Wu, G.; Chachques, J.C.; Carpentier, A.; Payen, D. The forgotten driving forces in right heart failure: new concept and device. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009, 17, 525–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alto, M.; Vizza, C.D.; Romeo, E.; Badagliacca, R.; Santoro, G.; Poscia, R.; Sarubbi, B.; Mancone, M.; Argiento, P.; Ferrante, F.; Russo, M.G.; Fedele, F.; Calabrò, R. Long term effects of bosentan treatment in adult patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension related to congenital heart disease (Eisenmenger physiology): safety, tolerability, clinical, and haemodynamic effect. Heart. 2007, 93, 621–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Holzer, M.; Losert, H.; Grassmann, D.; Ettl, F.; Gatterbauer, M.; Magnet, I.; Nuernberger, A.; Kienbacher, CL.; Gelbenegger, G.; Girsa, M.; Herkner, H.; Krammel, M. The association of capillary refill time and return of spontaneous circulation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Crit Care. 2025, 29, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, S.; Dai, G.; Carbognani, D.; Feng, M.; Yang, D.; Lila, N.; Chachques, J.C.; Wu, G. Intrapulmonary shear stress enhancement: a new therapeutic approach in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012, 33, 1332–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, G.M.; Kessler-Hanna, A.; Moore, G.W. Development of the coronary arteries in the embryonic human heart. Circulation. 1988, 77, 1250–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, S. Flow and Rate: Concept and Clinical Applications of a New Hemodynamic Theory. In Biophysics, Misra, A.N.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp.1-62. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Putzer, G.; Martini, J.; Spraider, P.; Abram, J.; Hornung, R.; Schmidt, C., Bauer, M.; Pinggera, D.; Krapf, C.; Hell, T.; Glodny, B.; Helbok, R.; Mair, P. Adrenaline improves regional cerebral blood flow, cerebral oxygenation and cerebral metabolism during CPR in a porcine cardiac arrest model using low-flow extracorporeal support. Resuscitation. 2021,168,151-159.

- Swenson, R.D.; Weaver, W.D.; Niskanen, R.A.; Martin, J.; Dahlberg, S. Hemodynamics in humans during conventional and experimental methods of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 1988, 78, 630–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, G.D.; Ji, C. Deakin, C.D.; Nolan, J.P.; Scomparin, C.; Regan, S.; Long, J.; Slowther, A.; Pocock, H.; Black, J.J.M.; Moore, F.; Fothergill, R.T.; Rees, N.; O’Shea, L.; Docherty, M.; Gunson, I.; Han, K.; Charlton, K.; Finn, J.; Petrou, S.; Stallard, N.; Gates, S.; Lall, R.; PARAMEDIC2 Collaborators. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2018,379,711-72.

- Pound, G.; Eastwood, G.M.; Jones, D.; Hodgson, C.L.; ANZ-CODE Investigators. ANZ-CODE management committee; Sites and Site Investigators. Potential role for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cardiopulmonary resuscitation (E-CPR) during in-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia: A nested cohort study. Crit Care Resusc. 2023,25,90-96. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A. A relationship between Reynolds stresses and viscous dissipation: implications to red cell damage. Ann Biomed Eng. 1995, 23, 21–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorge, G.; Schmidt, T.; Ito, B.R.; Pantely, G.A.; Schaper, W. Microvascular and collateral adaptation in swine hearts following progressive coronary artery stenosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 1989, 84, 524–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

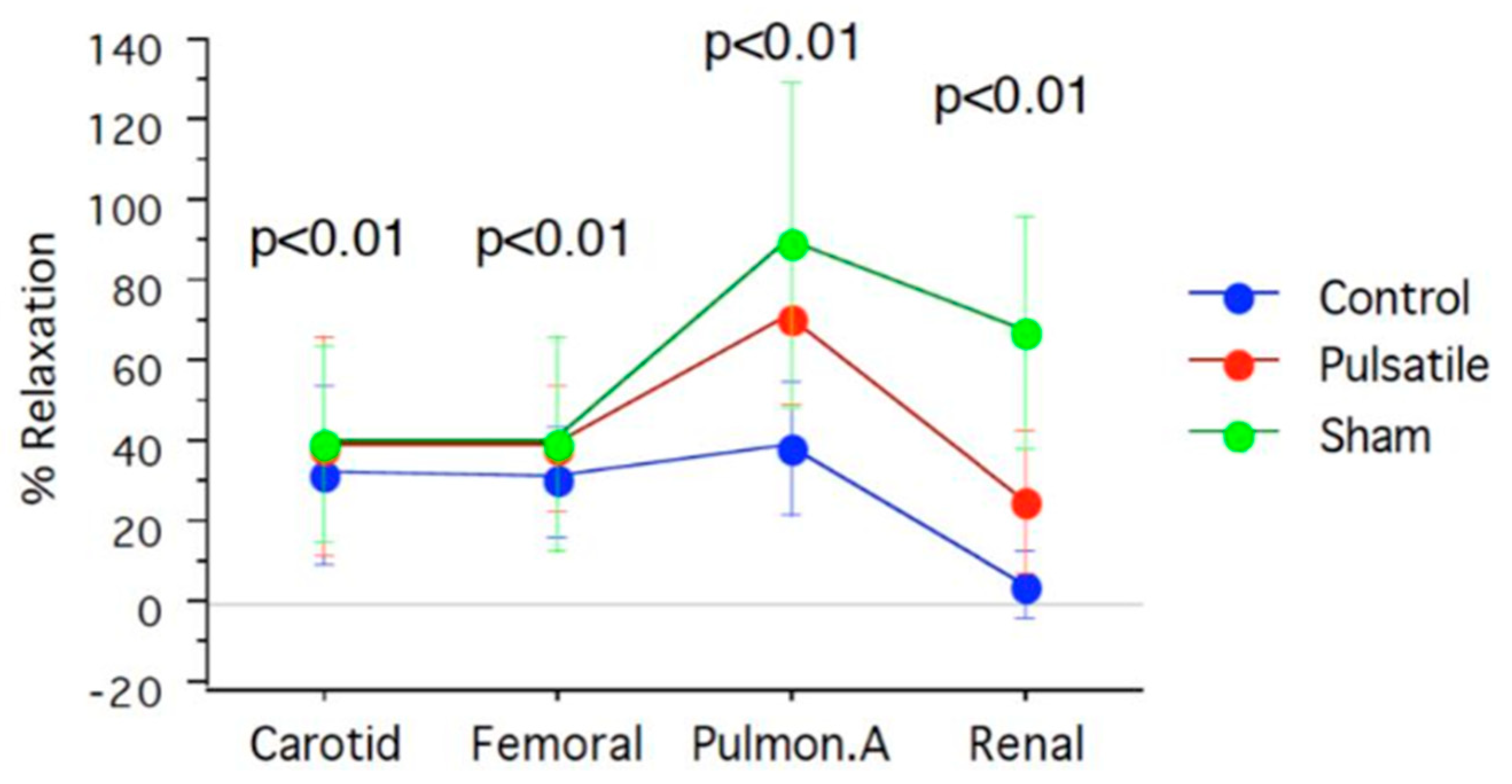

| Arterial segments | Sham | Pulsatile CPB | Control | Acetylcholine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid | 40±24.4 | 39.4±27.6 | 32.3±22.03 | |

| Femoral | 40±26.7 | 39.3±15.6 | 30.6±14.2 | % |

| Pulmonary | 78±37.5 | 72.2±25.9 | 39.3±16.6 | |

| Renal | 67±28.9 | 26±17.7 | 5.3±8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).