1. Introduction

Aging is a complex, ever-evolving biological process that profoundly influences our cellular and neurological systems. One hallmark of aging is a subtle but persistent low-grade inflammation termed “inflammaging” [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This sterile inflammation, occurring without infection, is a key feature of the aging process and has been implicated in age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, both marked by chronic, low-level central nervous system (CNS) inflammation [

3,

4,

5].

During the aging process, levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 increase, contributing to neuroinflammation. Evidence also suggests that certain anti-inflammatory cytokines, including transforming growth factor (TGF) and IL-1RA (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist), show elevated levels in aging [

6,

7,

8]. These changes in cytokine levels further shape the inflammatory milieu associated with aging and its impact on the CNS.

Carbohydrate-binding proteins, such as galectins, play significant roles in regulating these inflammatory events. Galectin-1 demonstrates strong anti-inflammatory properties by inducing apoptosis in activated T lymphocytes [

9], while galectin-3 exhibits pro-inflammatory functions by inducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines in septical and other serious inflammatory conditions [

10]. This dual functionality of galectins underscores their complex involvement in the inflammatory processes of aging.

By examining these intricate mechanisms, we gain insight into how inflammation influences the aging process and age-associated diseases. Such understanding may inform targeted strategies for mitigating inflammation-driven aging effects and their neurological consequences.

2. The Structure of Glycocalyx and Carbohydrate Recognition Domain Containing (CRD) Proteins

The ligand of these lectins localized inside the membrane in the presence of protein and lipid linked oligoscahrides. The lipid and protein components of the cell membrane are glycosylated, and these glycan structures on the cell surface form the "glycocalyx" or "cell coat." The biological functions of glycans can be categorized into three broad areas: (1) structural glycans which are part of extracellular scaffolds such as cell walls or extracellular matrix, (2) glycans which participates in energy metabolism as carbon source for energy production (3) glycans with information carriers based on interaction with GBPs (glycan binding protein) [

11]

Glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus produces various glycans that typically attach to cellular proteins and lipids. In mammalian cells, the building blocks of cell surface glycans consist of nine monosaccharides: fucose, galactose, N-acetyl-lactosamine, glucose, glucuronic acid, mannose, sialic acid, and xylose. These monosaccharides combine to form the final protein- and lipid-bound glycan structures [

12].

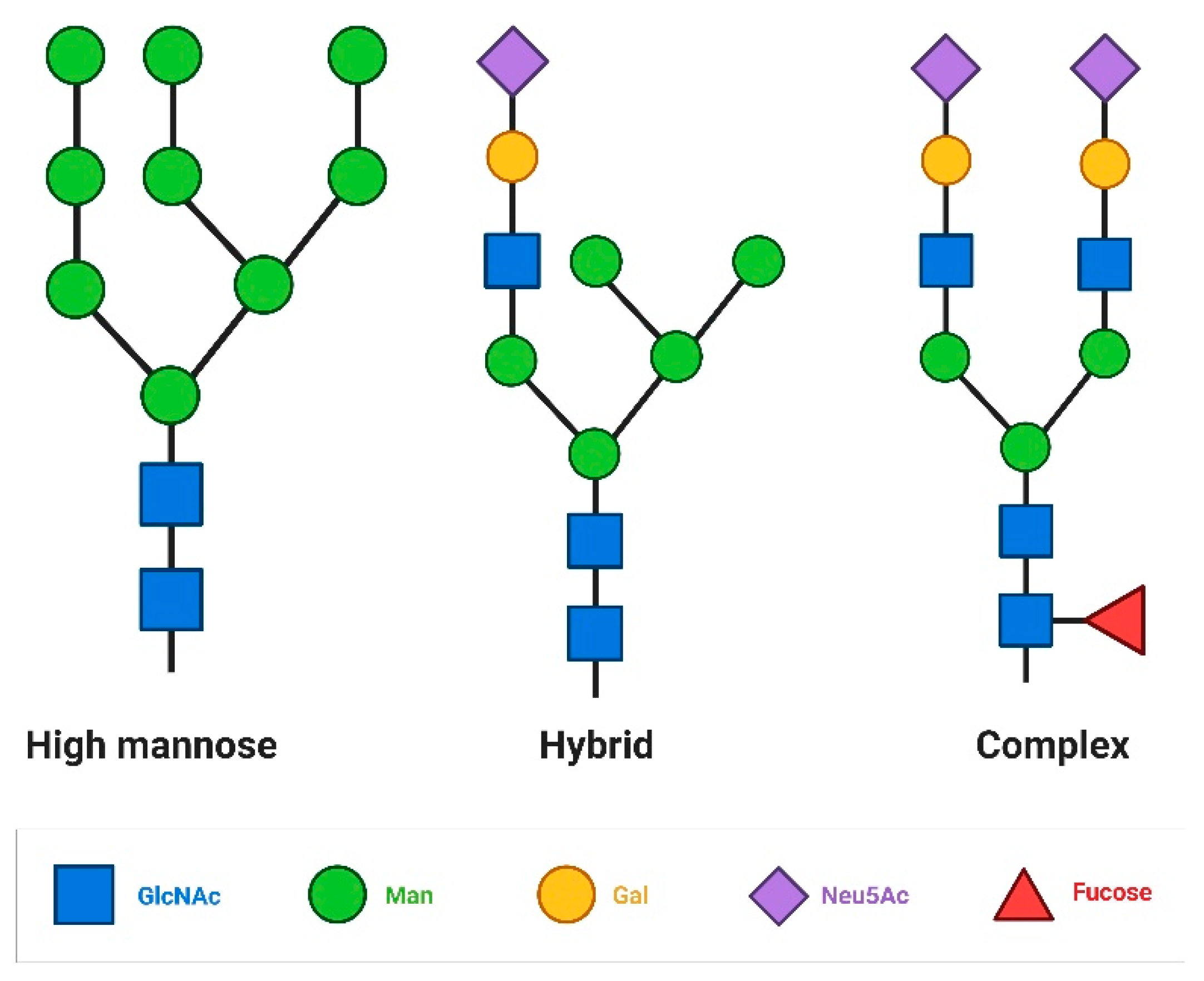

In N-Glycans the carbohydrate chain attaches to asparagine residues of proteins, specifically in the Asn-X-Ser/Thr motif. All eukaryotic N-glycans share a common core sequence with 5 carbohydrate molecules coupled to the Asn amino acid side chain of Asn-X-Ser motif in the following order: Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-Asn-X-Ser/Thr.

These core sequence could be extended to form the final structure of the cell surface N glycans. There are oligomannose type glycans in which only mannose residues extend the core and complex N glycans where antennae initiated by GlcNAc extend the core. The structure of complex N-glycans can form bi-, tri-, or tetra-antennae complexes, depending on the number of branches. These branched N-glycans on the cell surface have a high capacity to bind GBPs, enabling information carrier functions. In hybrid N glycans mannose extends the Manα1-6 arm of the core, while one or two GlcNAc-initiated antennae extend the Manα1-3 arm [

13]. (

Figure 1)

In O-glycan structures an glycan structures attach to Ser/Thr residues forming four major core structures. The Core 1 glycans formed by the extension of O-GalNAc linked to Ser/Thr residues by β1-3Gal. The Core 2 O glycans formed by the addition of β1-6GlcNAc to the GalNAc of Core 1. In Core 3 glycans the GlcNAc couple to –O GalNAc with β1-3 link. The Core 4 type O glycans formed by branching Core 3 with β1-6GlcNAc.

Each core can be extended by a variety of sugar residues, forming linear or branched chains similar to those of N-glycans and glycolipids [

14].

3. Galectins in the Central Nervous System (CNS)

Galectins, the best charachterized immunregulatory lectins, in particular, bind β-galactose-containing glycoconjugates (e.g., N-acetyl-lactosamine (LacNAc), formed by Gal and GlcNAc) and share structural homology in their carbohydrate-recognition domains. These are also referred to as S-type lectins due to their dependence on disulfide bonds for stability and carbohydrate binding. The galectin family consists of 15 distinct members, which are classified into three main structural types the proto-type galectins with two identical CRD (galectin-1, -2, -5, -7, -10, -11, -13, -14, and -15), chimera type galectins with one CRD and another distinct domain (galectin-3) and the tandem repaeat galectins posses two CRD with different carbohydrate specifities (galectin-4, -6,-8,-9, and -12) [

15].

The glycan-binding affinity of galectins is influenced by the glycan structure and modifications of galactose residues, such as fucosylation, sialylation, and sulfation [

16]. For instance, the affinity of galectins increases with the branching of complex N-glycans or the presence of a repeated LacNAc motif. However, galectins vary in their binding capacities depending on the glycan modification. Galectin-1 recognize alpha2,3-sialylated and the non-sialylated branched N-glycans, but not the alpha2,6 sialylated N glycans. [

17]. In contrast, galectin-3 and galectin-9 maintain their ability to bind these modified glycan forms. The core 2 O-glycans with polyLacNac structures can also be recognized by galectin-1, galectin-3, and galectin-9 [

18]. Galectins also bind to lactose-containing glycolipids like galectin-4 binds to sulfatide and SM3 (lactosylceramide sulfate), galectin-1 recognizes GM (manosialo-gangliosid) and GA1 (asialo gangliosids) type gangliosides and galectin-8 couple to GD1a (ganglioside N-acetylgalactosaminyl) and GM3 (monosialodihexosylganglioside).

Additionally, galectins, especially galectin-3 and galectin-9, are known to bind sulfated proteoglycans, such as keratan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate[

19].

Because of their heteromeric structure and multiple CRD domains, many galectins can bridge cell surface molecules. This promotes interactions among cell surface components, facilitates lipid raft formation, and influences signal transduction events [

20].

4. Galectins in the Central Nervous System (CNS)

The most charchterized member of the galectin (galectin-1, galectin-3, galectin-4, galectin-8 and galectin-9) family is expressed all cell type of the CNS (

Table 1).

4.1. Neurons and Galectins

4.1.1. Galectin-1 in Neurons

According to in situ hybridization studies, galectin-1 is expressed in primary sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), motoneurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, and motor nuclei in the brainstem, including the facial motor nucleus, trigeminal motor nucleus, and nucleus ambiguus. Additionally, specific regions of the cerebellum, such as the cerebellar dentate nucleus, along with neurons in the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus and vestibular nucleus, also express galectin-1. These findings indicate that galectin-1 expression is significantly higher in the DRG and spinal cord than in the brain, and its presence is detectable soon after neuronal differentiation [

39].

Galectin-1 interacts with glycosylated structures on the neuronal cell surface, playing a key role in adhesion modulation. For instance, galectin-1 expressed in the olfactory bulb promotes olfactory bulb fasciculation [

21]. Moreover, the oxidized form of galectin-1 supports neurite outgrowth, aiding axonal regeneration [

40,

41]. Both galectin-1 and galectin-3 promote neurite outgrowth and branching by inhibiting the Semaphorin 3A (Sema3A) pathway or binding to neural cell adhesion molecule L1 (NCAML1) and laminin. Sema3A normally has a repellent effect on axonal growth, as it inhibits actin polymerization via PlexinA4 surface receptors. Galectin-1 blocks this interaction by binding to the glycan structure on PlexinA4, facilitating its endocytosis and removing it from the cell surface, thereby promoting axon growth [

22].

4.1.2. Galectin-3 in Neurons

Galectin-3 is widely expressed in the brain, with high levels in the hypothalamus, particularly in the arcuate nucleus and dorsomedial nucleus. Moderate expression is observed in the supraoptic, paraventricular, and ventromedial nuclei. Galectin-3 is also present in the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis (VOLT), a sensory circumventricular organ (CVO). Outside the hypothalamus, galectin-3 is found in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus, the cochlear nucleus, the solitary nucleus, and the pontine nucleus, though subcortical nuclei show no immunoreactivity [

39].

Galectin-3 interacts with laminin and NCAML1, modulating cell adhesion and promoting neurite outgrowth [

23]. Its phosphorylated form (pGal-3) enhances NCAML1 association with Thy-1-rich membrane microdomains and recruits membrane-actin linker proteins (ERM (ezrin radixin moesin) proteins) via interaction with the intracellular domain of L1. This mechanism locally regulates the L1-ERM-actin pathway, contributing to axon branching. Phosphorylation of galectin-3 may act as a molecular switch for axonal responses [

24].

4.1.3. Galectin-4 in Neurons

Galectin-4 is expressed in the rat brain during early postnatal development but decreases significantly by days 12-16 and becomes undetectable in adults. Its expression is linked to the myelination process and is localized in the cerebral cortex, hippocampal formation, thalamus, and corpus callosum, where it is found in both neurons and oligodendrocytes[

36]. Galectin-4 facilitates communication between neurons and oligodendrocytes, which is essential for proper myelination. It binds to the N-glycan end of NCAML1 molecules, promoting L1 membrane clustering needed for myelin sheath formation. Galectin-4 also binds sulfatide-containing microtubule-associated carriers, organizing the transport of L1 and other axonal glycoproteins, which is critical for proper axon growth [

25].

4.1.4. Galectin-8 in Neurons

Galectin-8 is expressed in the thalamus, choroid plexus, and weakly in the hippocampus and cortex in mice. It is produced by primary cultured hippocampal neurons and has neuroprotective effects against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and amyloid-beta-induced neurotoxicity. Galectin-8 achieves this by activating β1-integrins (α3/β1 and α5/β1 integrins), ERK1/2, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, which mediate neuroprotection [

26].

4.2. Astrocytes and Galectins

4.2.1. Galectin-1 in Astrocytes

Astrocytes predominantly express galectin-1, which induces their differentiation while strongly inhibiting proliferation. Differentiated astrocytes, in turn, produce high levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a mechanism that may help prevent neuronal loss after injury [

27,

42]. Following ischemic injury, galectin-1 expression is upregulated in activated astrocytes around the infarct, where it inhibits astrocyte proliferation, attenuates astrogliosis, and downregulates the expression of nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-1β [

43]. However, after spinal cord injury, GFAP-positive reactive astrocytes begin to express galectin-1, which enhances astrocytosis [

44].

4.2.2. Galectin-3 in Astrocytes

Galectin-3 is also expressed by activated astrocytes in the ischemic brain, where it plays a role in post-ischemic tissue remodeling by enhancing angiogenesis and neurogenesis [

45,

46]. During brain injury, galectin-3 activates the Notch signaling pathway, which is essential for the astrocytic response to injury by reactive astrocytes [

28].

4.2.3. Galectin-9 in Astrocytes

Under normal conditions, astrocytes do not express galectin-9. However, its expression increases in response to inflammatory signals such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and interferon-γ [

47].

4.3. Microglia and Galectins

4.3.1. Galectin-1 in Microglia

A specific microglia subpopulation with increased galectin-1 expression has been identified in aging and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This heightened galectin-1 expression is associated with the morphologically active, amoeboid phenotype of microglia [

48]. Galectin-1 plays a critical role in reducing microglia-related inflammatory processes by deactivating classically activated microglia and promoting an M2 phenotype shift. This reprogramming is mediated through interactions between galectin-1 and CD45-related O-glycans [

29].

4.3.2. Galectin-3 in Microglia

Activated microglia, but not resting microglia, express abundant galectin-3. Its expression increases in both M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes and rises further in pathological conditions such as ischemia or brain injury. Galectin-3 is also released by activated microglia in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, aging, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

49].

In Alzheimer’s disease, activated microglia expressing galectin-3 bind to TLR4 (Toll Like Receptor 4), MerTK, and TREM2 (Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2), which facilitates amyloid-beta clearance and promotes inflammatory responses associated with the disease [

30,

31,

32]. In Parkinson’s disease, the internalization of alpha-synuclein triggers galectin-3 release by microglia [

50].

In Huntington’s disease, microglia-released galectin-1 activates inflammasomes, leading to cytokine release [

51]. In multiple sclerosis (MS), galectin-3 expression is associated with demyelination and interacts with TREM2 to regulate inflammatory events [

52].

In stroke, galectin-3 binds to IGF1R (insulin like growth factor receptor 1) and TLR4, mediating cytokine release and microgliosis around the infarct site. Additionally, galectin-3 promotes VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) release, supporting angiogenesis[

53]. In traumatic brain injury (TBI), galectin-3 interacts with TLR4, driving intense inflammatory responses and cytokine release [

54].

Galectin-3 also binds to the MerTK receptor on microglial surfaces, enhancing their phagocytic activity. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) plays a central role in microglial reprogramming mediated by galectin-3 [

33].

4.3.3. Galectin-4 in Microglia

While galectin-4 is not expressed under normal microglial conditions [

36], it becomes expressed in activated microglia within the brain and spinal cord in cuprizone-induced demyelination models of multiple sclerosis lesions [

55].

4.3.4. Galectin-9 in Microglia

Stimulation with Poly I:C triggers galectin-9 expression in microglia, and astrocyte-derived galectin-9 further enhances TNF expression in microglial cells [

34].

4.4. Oligodendrocytes and Galectins

During their development, oligodendrocytes undergo a well-characterized maturation process, with each stage associated with a specific molecular expression pattern.

Expression of galectin-1 is associated with A2B5/PDGFRα/O4-positive oligodendrocyte precursors and pre-oligodendroblasts but is absent in O1-positive mature oligodendrocytes [

35].

Galectin-3 is predominantly expressed in mature oligodendrocytes. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) secrete matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), which cleaves galectin-3 into truncated proteins. These truncated forms lack the ability to form oligomers but have an increased carbohydrate-binding capacity [

56,

57]. Extracellular galectin-3 promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination, whereas galectin-1 inhibits these processes, suggesting opposing roles for the two galectins in oligodendrocyte differentiation [

35].

Galectin-4 is present in the nucleus of OPCs and accumulates in the nucleus of mature oligodendrocytes [

36]. Interestingly, galectin-4 is released by neurons-not oligodendrocytes-and inhibits myelination by binding to pre-myelinating oligodendrocytes, thereby influencing the timing of myelination [

36,

58].

4.5. Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells and Galectins

The brain contains two primary populations of stem and progenitor cells: one in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle and another in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus.

The SVZ consists of astrocytic neural stem cells (Type B1 cells), astrocytes (Type B2 cells), transit-amplifying cells (Type C cells), and neuroblasts (Type A cells). Both galectin-1 and galectin-3 are expressed in this region.

Galectin-1 is expressed in GFAP-positive Type B1 cells (astrocytic neural stem cells). It plays an important role in the proliferation of adult neural progenitor cells, including SVZ astrocytes. Interaction between β1 integrin and galectin-1 is crucial for the proliferation-promoting effects of galectin-1 in neural progenitor cells of the subependymal zone (SEZ) [

37].

Galectin-3 is expressed in astrocytes but not in neuroblasts within the SVZ. Its presence promotes cell migration through the EGFR-mediated (epidermal growth factor receptor) pathway [

38]. Galectin-3 also inhibits cell emigration from the SVZ in the cuprizone-induced multiple sclerosis model [

59]. In viral-induced multiple sclerosis models, galectin-3 is essential for the neurogenic niche response in the SVZ. Loss of galectin-3 reduces chemokine expression, immune cell migration to the SVZ, and progenitor cell proliferation, particularly in the corpus callosum [

60].

After stab wound injury, both galectin-1 and galectin-3 expression increase in reactive astrocytes and neural stem cells, highlighting their role in regeneration [

61].

The hippocampal dentate gyrus subgranular layer is the second brain region with neural stem/progenitor cells. Galectin-1 is expressed in neural stem cells and downregulates neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus [

62]. It also promotes both basal and kainate-induced proliferation of neural progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus [

63].

5. Aging and Glycocalyx Modification in the Aging Coupled Inflammatory Events

More than 100 rare human genetic disorders have been identified that result from deficiencies in glycosylation pathways. Many of these disorders impact the central and/or peripheral nervous system, causing symptoms such as intellectual disabilities, hypotonia, and seizures.

One common disorder affecting N-linked glycosylation is PMM2-CDG (phosphomannose mutase2 congenital disorder), caused by a mutation in the PMM2 enzyme, which is responsible for converting mannose-6-phosphate to mannose-1-phosphate. This deficiency disrupts the dolichol-coupled oligosaccharide chain formation in the ER, impairing the global glycosylation process [

64].

During aging, the proportion of modified N-glycans, such as monoantennary (A1), agalactosylated (G0), and oligomannose (OM), increases in the serum of both sexes [

65]. In immunological terms, immunoglobulins are the most significant serum molecules. Aging causes global changes in IgG-coupled N-glycan patterns, particularly modifications at the ends of oligosaccharides. These changes include reduced galactose and sialic acid residues on branches (leaving GlcNAc in the terminal position) and increased core fucosylation.

These changes are prominent in inflammation-related autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [

66]. Elevated levels of agalactosylated IgG-G0 in aged individuals suggest that altered IgG activity may contribute to age-related inflammation, also known as "inflammaging." Aging alters the galactosylation but sialylation patterns of the IgG, which modulate the interaction between IgG and Fc receptors, thereby affecting their efficacy [

67].

Aging leads to reduced expression of glycosylation factors, not only in peripheral tissues but also in the brain. This reduction affects glycan structures and functions [

68]. For example, studies have shown that the aging brain exhibits decreased complexity in glycan profiles, particularly in brain-derived CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) proteins. The altered N-glycosylation patterns of these proteins impair their function and cellular communication, potentially affecting synaptic plasticity and neuronal connectivity-key processes for maintaining cognitive function [

69,

70].

In the brain and myelin structures, glycosylation patterns differ significantly between embryonic and adult stages, suggesting a role for glycosylation in aging.

Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) is a nervous system-specific molecule that mediates cellular adhesion in neural tissues. During embryonic development, the polysialylated form of NCAM (PolySia-NCAM) is widely and highly expressed in the nervous system, playing crucial roles in neurogenesis, cell migration, axon/dendrite growth, synaptic reorganization, and myelination [

71]. In adults, PolySia-NCAM expression is restricted to neurogenic regions, such as the subventricular zone (SVZ) and subgranular zone (SGZ), but is absent in non-neurogenic regions like the trigeminal ganglion and brainstem nuclei [

72].

Aging Coupled Chronic Diseases (AD) and Glycosylation

Chronic and aging-associated diseases also have glycosylation-dependent molecular backgrounds. Large-scale proteomic analyses have revealed significant changes in N-glycosylation patterns in Alzheimer’s disease. These changes include the appearance of glycosites that are exclusively glycosylated in the AD brain, possibly due to abnormal protein conformational changes that expose new glycosylation sites. Conversely, some proteins lose N-glycosylation sites due to misrecognition by the glycosylation machinery [

73].

Gene expression studies show that enzymes required for N-glycosylation are dysregulated in AD, altering protein glycosylation [

74]. The two key pathogenic proteins in AD, tau and amyloid-beta, both trigger ER stress, disrupting normal ER functions and glycosylation processes [

75].

In Alzheimer’s and aging brains, the endothelial glycocalyx in the microvasculature undergoes strong modifications. Plant-derived lectins, such as ConA (concanavalinA), can activate inflammasomes and trigger inflammatory events in the CNS microvasculature. These increment in lectin-binding capacity reflect alterations in the endothelial glycocalyx during aging and AD [

76,

77].

6. Lectin Based Effect on CNS Aging

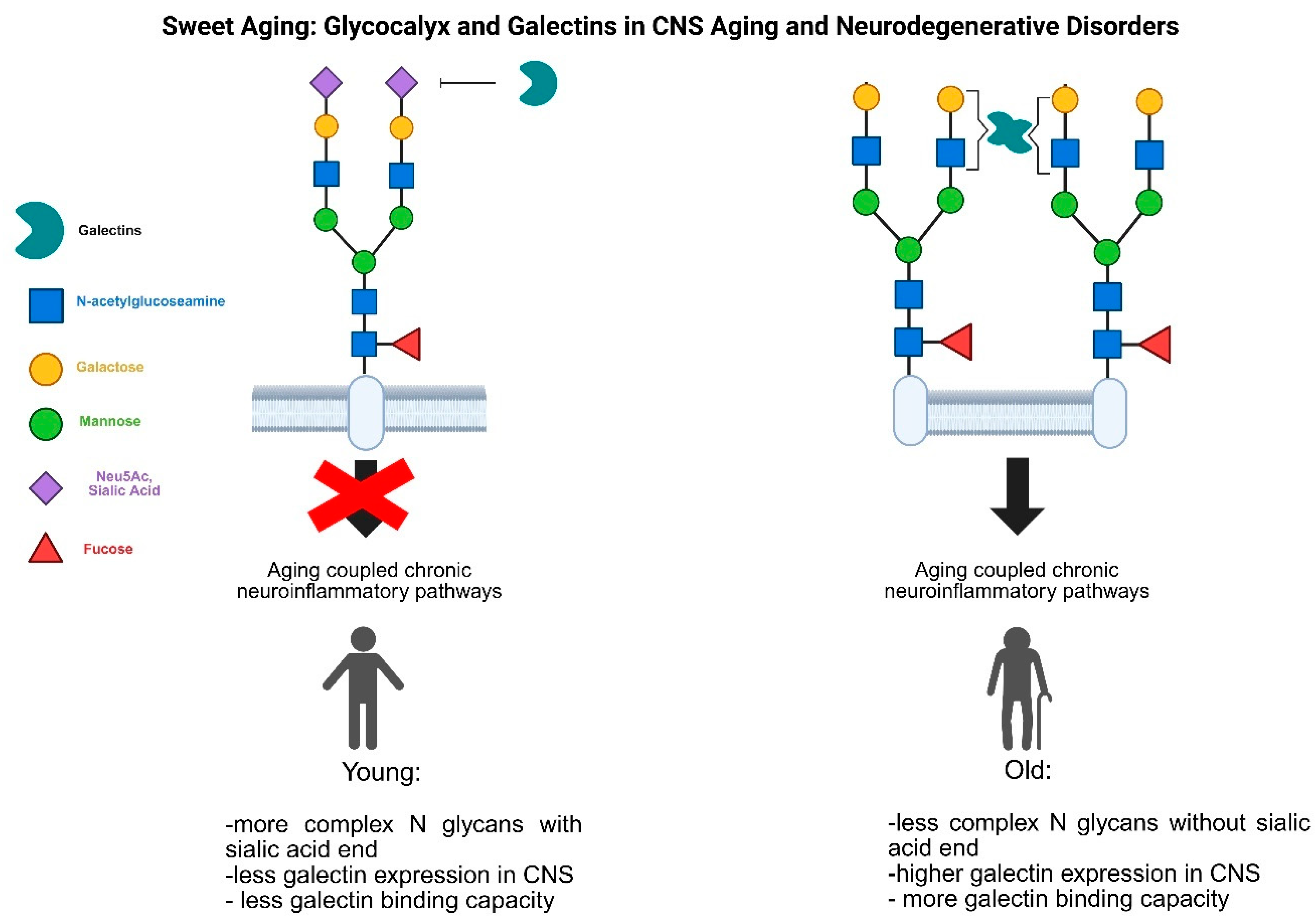

As highlighted earlier, glycosylation pattern alterations-particularly in immune-related pathways-play a significant role in chronic inflammation, including aging-related processes. These changes impact the glycocalyx and subsequently alter the amount and quality of membrane-bound lectins during inflammation within the nervous system (

Figure 2).

The correct sialylation of cell surface proteins is a crucial regulator of neuroimmunological homeostasis in the CNS. Microglial cells, the main regulator of CNS immune functions, detect sialic acid residues on neuronal membranes via their Siglec receptors. These interactions provide inhibitory signals to microglia due to the ITIM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif) in the Siglec receptors. When the sialylation pattern is disrupted due to injury or pathological events, this inhibitory signaling is impaired, leading to microglial activation and inflammation-driven tissue damage [

78]

.

Beneath the sialylated ends of glycosylated proteins lie N-acetyl-lactosamine structures, which are recognized by galectins. During aging, serum levels of inflammation-linked galectin-3 increase, underscoring their role in aging-related inflammation [

79]. Within the CNS, aging alters lectin-like molecules, with increasing levels of galectin-1-expressing microglial populations in the aged rodent brain. These microglia exhibit an activated morphology [

48].

In Alzheimer’s diseas, high levels of galectin-3 exacerbate amyloid deposits and worsen the pathological outcomes of the disease. In contrast, Galectin-3 knockout (KO) mice show reduced amyloid-beta oligomerization, suggesting that galectin-3 contributes to the disease’s progression [

80]. A microglia population with galectin-3 expression and inflammatory phenotype was markedly identified in AD mouse model brain with single cell RNA sequencing data [

81] . Galectin-3 shows colocalisation with TREM2 microglial activatory receptors in AD brain. [

49].

Severely damaged oligosaccharides often terminate in mannose residues, which are recognized by mannose-binding lectins (MBLs). These MBLs can opsonize damaged cells, triggering complement activation or phagocytosis to clear the injured tissue. In AD, MBL binds to amyloid-beta, modulating inflammation associated with the disease. Elevated levels of MBL may increase the brain's inflammatory capacity in AD, contributing to disease progression.[

82].

7. Concluding Remarks

Aging is a highly intricate process, marked by physiological changes across the body, including within the central nervous system. As we age, the delicate molecular balance that maintains cellular homeostasis becomes disrupted, leading to impaired cellular functions. Among the first responders in molecular interactions are the glycans-proteins and lipids linked with oligosaccharide structures-mediated by lectins, which are carbohydrate-recognizing molecules.

The evidence presented highlights that during aging and chronic inflammation, key aspects of lectin-based signaling pathways undergo significant changes. These include alterations to both the receptor component, such as the modified N-glycan patterns on cell surfaces, and the ligand component, as seen in the altered expression of lectins in the CNS. Notably, the presence of simpler glycans with N-acetyllactosamine ends enhances the efficacy of galectin-mediated signaling. These changes in carbohydrate-based interactions could contribute to the disruption of molecular homeostasis, driving the pathological processes associated with CNS aging.

Detecting lectins or their recognized oligosaccharides in cerebrospinal fluid or CNS tissue could serve as a diagnostic tool to assess the state of CNS aging. Furthermore, modulating the strength and efficiency of carbohydrate-lectin interactions presents a potential therapeutic avenue for addressing CNS aging and related inflammatory conditions.

Author Contributions

Wrote the paper: AL. Edited the paper: AL, YM.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from TKP2021-EGA-28 and University of Szeged Open Acess

Fund (grant number: 7680) grant.

Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by a grant from TKP2021-EGA-28 and University of Szeged Open Acess Fund (grant number: 7680) grant.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| BDNF |

brain derived neurotrophic factor |

| CNS |

central nervous system |

| CRD |

carbohydrate reognition domain |

| CSF |

cerebrospinal fluid |

| DRG |

dorsal root ganglia |

| GalNAc |

N-acetyl-galactoseamine |

| GFAP |

glial fibrillar acidic protein |

| GlcNAc |

N-acetyl-glucosamine |

| Gal |

Galactose |

| IL |

interleukin |

| LacNAc |

N-acetyl-lactosamine |

| Man |

-Mannose |

| NCAML1 |

neural cell adhesion molecule L1 |

| OPC |

oligodendrocyte precursor |

| Sema3A |

semaphorin3A |

| SVZ |

subventricular zone |

| TGF |

transforming growth factor |

| TLR4 |

toll like receptor4 |

| TNF |

tumor necrosis factor |

| TREM2 |

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

References

- Frasca, D.; Blomberg, B.B. Inflammaging decreases adaptive and innate immune responses in mice and humans. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, L.L.; et al. Microglia and memory: modulation by early-life infection. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 15511–15521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L. Neuroinflammation and cognitive aging. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, J.R.; Streit, W.J. Microglia in the aging brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006, 65, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsey, R.J.; et al. Plasma cytokine profiles in elderly humans. Mech Ageing Dev 2003, 124, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallone, L.; et al. The role of IL-1 gene cluster in longevity: a study in Italian population. Mech Ageing Dev 2003, 124, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciullo, P.L.; et al. Inflammaging and Anti-Inflammaging: The Role of Cytokines in Extreme Longevity. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2016, 64, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perillo, N.L.; et al. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by galectin-1. Nature 1995, 378, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.B.; et al. Galectin-3 functions as an alarmin: pathogenic role for sepsis development in murine respiratory tularemia. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. and S. Kornfeld, Historical Background and Overview, in Essentials of Glycobiology, A. Varki; et al. Editors. 2022: Cold Spring Harbor (NY). 1–20.

- Kornfeld, R. and S. Kornfeld, Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem 1985, 54, 631–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagae, M. and Y. Yamaguchi, Function and 3D structure of the N-glycans on glycoproteins. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 8398–8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, H. and I. Brockhausen, The biosynthesis of branched O-glycans. Symp Soc Exp Biol 1989, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirabayashi, J. and K. Kasai, The family of metazoan metal-independent beta-galactoside-binding lectins: structure, function and molecular evolution. Glycobiology 1993, 3, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nio-Kobayashi, J. and T. Itabashi, Galectins and Their Ligand Glycoconjugates in the Central Nervous System Under Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Front Neuroanat 2021, 15, 767330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppanen, A.; et al. Dimeric galectin-1 binds with high affinity to alpha2,3-sialylated and non-sialylated terminal N-acetyllactosamine units on surface-bound extended glycans. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 5549–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.D., F.T. Liu, and G.R. Vasta, Galectins, in Essentials of Glycobiology, A. Varki; et al. Editors. 2015: Cold Spring Harbor (NY). 469–480.

- Yang, R.Y., G. A. Rabinovich, and F.T. Liu, Galectins: structure, function and therapeutic potential. Expert Rev Mol Med 2008, 10, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A. and M.A. Toscano, Turning 'sweet' on immunity: galectin-glycan interactions in immune tolerance and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanthappa, N.K.; et al. Rat olfactory neurons can utilize the endogenous lectin, L-14, in a novel adhesion mechanism. Development 1994, 120, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinta, H.R.; et al. Ligand-mediated Galectin-1 endocytosis prevents intraneural H2O2 production promoting F-actin dynamics reactivation and axonal re-growth. Exp Neurol 2016, 283(Pt A), 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesheva, P.; et al. Galectin-3 promotes neural cell adhesion and neurite growth. J Neurosci Res 1998, 54, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Revuelta, N.; et al. Phosphorylation of adhesion- and growth-regulatory human galectin-3 leads to the induction of axonal branching by local membrane L1 and ERM redistribution. J Cell Sci 2010, 123(Pt 5), 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, S.; et al. Neuronal Galectin-4 is required for axon growth and for the organization of axonal membrane L1 delivery and clustering. J Neurochem 2013, 125, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, E.; et al. GALECTIN-8 Is a Neuroprotective Factor in the Brain that Can Be Neutralized by Human Autoantibodies. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 7774–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.S.; et al. Galectin-1 attenuates astrogliosis-associated injuries and improves recovery of rats following focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem 2011, 116, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, T.N., L. M. Delgado-Garcia, and M.A. Porcionatto, Notch1 and Galectin-3 Modulate Cortical Reactive Astrocyte Response After Brain Injury. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 649854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starossom, S.C.; et al. Galectin-1 deactivates classically activated microglia and protects from inflammation-induced neurodegeneration. Immunity 2012, 37, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, K.; et al. Activated Microglia Desialylate and Phagocytose Cells via Neuraminidase, Galectin-3, and Mer Tyrosine Kinase. J Immunol 2017, 198, 4792–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza-Serrano, A.; et al. Galectin-3, a novel endogenous TREM2 ligand, detrimentally regulates inflammatory response in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2019, 138, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Galectin-3 regulates microglial activation and promotes inflammation through TLR4/MyD88/NF-kB in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Clin Immunol 2022, 236, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, U.V.; et al. Galectin-3 enhances angiogenic and migratory potential of microglial cells via modulation of integrin linked kinase signaling. Brain Res 2013, 1496, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steelman, A.J. and J. Li, Astrocyte galectin-9 potentiates microglial TNF secretion. J Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.A.; et al. Galectin-3 drives oligodendrocyte differentiation to control myelin integrity and function. Cell Death Differ 2011, 18, 1746–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stancic, M.; et al. Galectin-4, a novel neuronal regulator of myelination. Glia 2012, 60, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, M.; et al. A carbohydrate-binding protein, Galectin-1, promotes proliferation of adult neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 7112–7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, I.; et al. Galectin-3 maintains cell motility from the subventricular zone to the olfactory bulb. J Cell Sci 2011, 124(Pt 14), 2438–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, M.A.; et al. Selective expression of an endogenous lactose-binding lectin gene in subsets of central and peripheral neurons. J Neurosci 1990, 10, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, H.; et al. Galectin-1 regulates initial axonal growth in peripheral nerves after axotomy. J Neurosci 1999, 19, 9964–9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, Y.; et al. Oxidized galectin-1 promotes axonal regeneration in peripheral nerves but does not possess lectin properties. Eur J Biochem 2000, 267, 2955–2964. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W.S.; et al. Galectin-1 enhances astrocytic BDNF production and improves functional outcome in rats following ischemia. Neurochem Res 2010, 35, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; et al. Galectin-1 induces astrocyte differentiation, which leads to production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Glycobiology 2004, 14, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, A.D.; et al. Galectin-1 in injured rat spinal cord: implications for macrophage phagocytosis and neural repair. Mol Cell Neurosci 2015, 64, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of Galectin-3 in perinatal rat hypoxic-ischemic brain injury model. Neurosci Lett 2019, 711, 134439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.P.; et al. Galectin-3 mediates post-ischemic tissue remodeling. Brain Res 2009, 1288, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, A.J.; et al. Galectin-9 protein is up-regulated in astrocytes by tumor necrosis factor and promotes encephalitogenic T-cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 23776–23787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, T.; et al. Galectin-1 as a marker for microglia activation in the aging brain. Brain Res 2023, 1818, 148517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Revilla, J.; et al. Galectin-3, a rising star in modulating microglia activation under conditions of neurodegeneration. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza-Serrano, A.; et al. The role of Galectin-3 in alpha-synuclein-induced microglial activation. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014, 2, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Siew, J.J.; et al. Galectin-3 is required for the microglia-mediated brain inflammation in a model of Huntington's disease. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, H.C.; et al. Galectin-3 controls the response of microglial cells to limit cuprizone-induced demyelination. Neurobiol Dis 2014, 62, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.C.; et al. Blocked angiogenesis in Galectin-3 null mice does not alter cellular and behavioral recovery after middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke. Neurobiol Dis 2014, 63, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, P.K.; et al. Galectin-3 released in response to traumatic brain injury acts as an alarmin orchestrating brain immune response and promoting neurodegeneration. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, C.; et al. Galectin-4, a Negative Regulator of Oligodendrocyte Differentiation, Is Persistently Present in Axons and Microglia/Macrophages in Multiple Sclerosis Lesions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018, 77, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochieng, J.; et al. Galectin-3 is a novel substrate for human matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 14109–14114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; et al. Cleavage and phosphorylation: important post-translational modifications of galectin-3. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2017, 36, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Revuelta, N.; et al. Neurons define non-myelinated axon segments by the regulation of galectin-4-containing axon membrane domains. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, J.M.; et al. Cuprizone demyelination induces a unique inflammatory response in the subventricular zone. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.E.; et al. Loss of galectin-3 decreases the number of immune cells in the subventricular zone and restores proliferation in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. Glia 2016, 64, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirko, S.; et al. Astrocyte reactivity after brain injury-: The role of galectins 1 and 3. Glia 2015, 63, 2340–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, Y.; et al. Galectin-1 is expressed in early-type neural progenitor cells and down-regulates neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Mol Brain 2011, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, K.; et al. Galectin-1 promotes basal and kainate-induced proliferation of neural progenitors in the dentate gyrus of adult mouse hippocampus. Cell Death Differ 2009, 16, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeze, H.H. , Understanding human glycosylation disorders: biochemistry leads the charge. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 6936–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado-Baleato, O.; et al. Age-Related Changes in Serum N-Glycome in Men and Women-Clusters Associated with Comorbidity. Biomolecules 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferis, R.; et al. A comparative study of the N-linked oligosaccharide structures of human IgG subclass proteins. Biochem J 1990, 268, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakovic, M.P.; et al. High-throughput IgG Fc N-glycosylation profiling by mass spectrometry of glycopeptides. J Proteome Res 2013, 12, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, D.; et al. Concerted Regulation of Glycosylation Factors Sustains Tissue Identity and Function. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.; et al. Mammalian brain glycoproteins exhibit diminished glycan complexity compared to other tissues. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerenfaenger, M.; et al. Glycoproteomics in Cerebrospinal Fluid Reveals Brain-Specific Glycosylation Changes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, L. , PSA-NCAM in mammalian structural plasticity and neurogenesis. Prog Neurobiol 2006, 80, 129–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; et al. Different properties of polysialic acids synthesized by the polysialyltransferases ST8SIA2 and ST8SIA4. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. Integrative glycoproteomics reveals protein N-glycosylation aberrations and glycoproteomic network alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; et al. Transcriptomic and glycomic analyses highlight pathway-specific glycosylation alterations unique to Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogen-Shtern, N. Ben David, and G.Z. Lederkremer, Protein aggregation and ER stress. Brain Res 2016, 1648(Pt B), 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Hare, N., K. Millican, and E.E. Ebong, Unraveling neurovascular mysteries: the role of endothelial glycocalyx dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Front Physiol 2024, 15, 1394725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, T.; et al. Plant Lectins Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome To Promote Inflammatory Disorders. J Immunol 2017, 198, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnartz-Gerlach, B., J. Kopatz, and H. Neumann, Siglec functions of microglia. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; et al. Galectin-3, osteopontin and successful aging. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016, 54, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.C.; et al. Galectin-3 promotes Abeta oligomerization and Abeta toxicity in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Differ 2020, 27, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, H.; et al. Temporal Tracking of Microglia Activation in Neurodegeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larvie, M.; et al. Mannose-binding lectin binds to amyloid beta protein and modulates inflammation. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012, 2012, 929803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).