1. Introduction

Risk is an inherent part of running a business. The level of risk amplifies, and challenges increase multifold when transactions occur across borders. There is an added element of uncertainty in the international business environment that makes it more dynamic when compared with domestic trading environment. Risk across borders can manifest in various forms, that range from market fluctuations, to import restrictions, to even insolvencies and defaults of different degrees. In addition to paying ongoing trade costs, and facing cultural and institutional differences, exporters must be ready for different forms of risks while they penetrate foreign markets.

One of the dimensions of global business risks is political risk, which arises from governments’ policies and actions that can directly affect business operations and firms’ ability to perform their economic obligations. Wars, coups, political violence, regime changes due to uprisings, currency transfer and conversion restrictions, expropriation, and regulatory changes can all wreak havoc on exporters and investors in foreign markets. Given the rising political instability worldwide, companies remain vigilant to political risks and seek ways to mitigate them. According to recent Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) reports, $30.2 billion worth of political risk and credit enhancement guarantees have been issued since 2020, representing a 75% increase compared to the previous five-year period. Meanwhile, total trade credit insurance premiums recorded by International Credit Insurance and Surety Association (ICISA) members reached €42.1 billion between 2016 and 2021.

The importance of political risk on globalization has become increasingly recognized by international economics and business researchers. They have mainly addressed the hidden barriers and threats political risk poses and documented its deteriorating impact on trade and foreign direct investment.

1 In this study, we seek to complement and extend this research by analyzing the impact of political risk on trade finance using disaggregated industry level trade finance data from Turkey.

Trade finance is broadly defined as the methods and instruments that support exporting and importing firms throughout the trade cycle (Menichini 2009). Banks, firms, credit agencies provide trade finance, mainly short-term credit, to enhance global trade. Aubin (2007) notes that more than 90% of international trade are underpinned by some form of trade credit. According to survey reports, one of the main reasons why world trade experienced a slowdown in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2009 was the expensive trade credit in global recession period. That is why, G20 countries agreed to provide

$250 billion trade finance for two years in 2009.

2 Trade finance facilitates the cross-border transactions by providing capital and liquidity to companies, mitigates the country and company specific risks and provides a set of payment instruments that help exporters to timely receive their payments and importers to securely receive their orders.

Trade finance serves a handful of functions, but this study’s primary focus is the payment aspect of trade finance, with emphasis on its relationship with political risk. In any form of trade, it is crucial to get paid in full and on time for the seller and to receive the goods as specified in the contract for the buyer. Given the degree of incomplete information between buyers and sellers, an appropriate method of payment must be chosen in international trade to minimize the default and non-delivery risks. An exporter can execute a cross-border transaction in two main ways: through cash in advance, where the payment takes place before the goods are shipped, and on an open account (extending trade credit) where the payment is received some time after the delivery. In international business, banks also act as intermediaries to reduce the risk of the transactions and provide other financing options such as letter of credit and documentary collections. Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2017) show that letters of credit constitute about 13 percent and documentary collections about 2 percent of global trade.

Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013) develops a theoretical model to analyze the payment choice in international transactions. In his model, two risk-neutral importing and exporting firms play a one-shot game where the exporter makes a take it or leave it offer to the importer. This proposal specifies the price, quantity, and the payment method in the exchange. In this setting, there are two problems arising: a financing problem and a commitment problem. Under open account, exporter finances the transaction using her country’s financial resources and enforcement takes place in the importer’s country. Trade finance extended by the firm in the country with lower financing costs and weaker enforcement maximizes the exporter profit. Consequently, open account export transactions are more likely to happen when the enforcement is strong and the and financing cost is high in importer’s country.

Political risk affects the payment choice both via financing and commitment channels described in Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013). First, political risk in the importer’s country increases the risk premium in financial markets and drives up the cost of financing, which makes it less likely for the buyer to offer cash in advance. Second, sellers will perceive higher risks in terms of following country-specific procedures and claiming their rights and thus be reluctant to extend trade credit when there is political instability and repression in export destinations. Accordingly, we hypothesize that export transactions executed under open account terms will increase if the political risk in the export markets decreases. Using industry-level trade finance data from Turkey and applying different econometric specifications, we provide strong support for this hypothesis in this paper.

In our formal econometric analysis, we use a wide range of indicators for political risk to identify the relative importance of these indicators for extending trade finance. We investigate the influences of law and order, democratic accountability, government stability, socio-economic conditions, investment profile, internal and external conflict, military in politics, and the quality of bureaucracy. We also perform a battery of sensitivity tests. Our results are robust to a subsample analysis in which we exclude observations from different regions. We also checked the robustness of our results by dropping the top three exporting industries from our sample. We employed linear regressions as well as probit and ordered logit models. All estimations strongly confirm the effect of political risk on trade finance. Finally, we also analyzed the differential impact of product complexity on the relationship between political risk on trade finance. We argue that industries with complex products will be more watchful for political risks before they extend trade of the degree of customization and relationship specific investment in their products. This hypothesis is supported in our model when we interact our political risk measures with the complexity measure developed in Nunn (2007).

The paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 provides a summary of related studies and our contribution. In

Section 3 we describe the data set.

Section 4 summarizes the identification strategy, results, robustness checks and extensions.

Section 5 concludes.

2. Related Literature and Contribution

Our paper bridges two strands of literature. One body of research studies the impact of political risk on international trade and investment. Within this research, scholars have documented the negative impacts of political risk on internationalization. An early example on the trade side is Morrow et al. (1998) which suggest the effect of international politics on trade flows. Anderson and Marcouiller (2002), on the other hand, shows that inadequate institutions constrain trade and omission of indices of institutional quality biases the estimates of gravity models of international trade. Long (2008) demonstrates that that expectations of domestic or interstate conflict, in addition to violent armed conflicts, are negatively correlated with bilateral trade flows. Berkowitz et al. (2006) observe that institutional quality of trade partners has a trade enhancing impact, especially for complex products. Oh and Revueny (2010) studies the interaction of political risk and disasters on trade and finds that the negative impact of disasters on trade flows is less severe for countries with low political risk. Moser et al. (2008) finds evidence that political risk has a detrimental effect on exports. More recently, Bilgin et al. (2018) examines the exports of Turkey to Islamic countries in a gravity framework and documents the negative impact of political risk and government instability on exports. The negative impact of political risk on investment, FDI and capital inflows was also documented in many studies (including but not limited to: Lensink et al., 2000; Busse and Hefeker, 2007; Harms and Ursprung, 2002; Harms, 2002; Solomon and Ruiz, 2012).

This study also fits into a much larger literature which blends trade and finance. One part of this research explores the effect of financial conditions in a country on its export flows. Financial development has been shown a source of comparative advantage for the industries that rely more on external finance (Beck, 2003; Manova, 2008). Similarly, Gur and Avsar (2016) demonstrate that R&D intensive industries export more in countries where financing cost is low. Hur et al. (2006) finds that countries with better financial institutions have higher export shares and trade balance in sectors with more intangible assets. Using Chinese firm-level data, Manova et al. (2015) provide evidence that credit constraints influence not only trade but also the pattern of multinational activity. Amiti and Weinstein (2011) and Chor and Manova (2012) find that constraints in the availability of trade finance culminated in the collapse of trade in the global recession period. Auboin and Engemann (2014) identify a significantly positive effect of insured trade credit, as a proxy for trade credits, on exports. Van der Veer (2014) also points out the importance of private credit insurance on exports.

Another strand within this literature focuses on the payment aspect of trade finance. On the theoretical side, Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013) examines the trade-off firms have between different payment terms in cross border trade and the cross-country differences in their use. He also indirectly tests the predictions of his model by gravity regressions and shows that financial conditions and contract environments both in exporting and importing country affects international trade. Love (2013) notes that lack of reliable and comprehensive data was the main reason why the literature of the payment aspect of trade finance paled as compared to other dimensions. The data was mainly gathered through bank and firm surveys, which often had insufficient coverage and did not provide bilateral information on different payment terms in exports or imports.

More recently, this literature has seen several empirical contributions as more detailed payment data on trade transactions has become available. Hoefele et al. (2016) tests the predictions of Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013) model utilizing the World Bank Enterprise Survey and document that international trade transactions are more likely to be paid after delivery when financing costs in the source country are high and when contract enforcement is weak. Similar result is obtained in Antras and Foley (2015), which uses transaction trade data from a single firm that sells poultry products. Turkcan and Avsar (2018) shows that financing cost in a country is more important in terms of offering post-shipment terms in exports for the industries that rely more on external finance. Demir and Javorcik (2018) provide evidence that competitive pressures lead exporters to provide trade credit.

A few empirical works on payment methods placed the microscope on letter of credit. Theoretical model by Glady and Potin (2011) finds that exports to countries with better financial sector are more likely to occur on letter of credit. Using Colombian data, Ahn and Sarmiento (2013) shows that adverse bank liquidity shocks led to a decline in imports through letter of credit. Olsen (2013) suggests that the use of letter of credit can be used to overcome weak contract enforcement during the crisis. Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013) examines the letter of credit transactions using US banks’ data and show that the use of letter of credit increases in default risk and decreases in interest rates.

To sum up, this work contributes to the literature that examines the effect of political risk on international trade and mentions the trade finance channel for the first time. In addition, we also contribute to a growing literature on the payment choice in international transactions by analyzing the effect of different dimensions of political risk on the decision to extend trade credit. The bilateral information on payment methods in export transactions at the industry level used in this study represents a significant improvement over other studies in this literature.

3

3. Data

Data on method of payments in export transactions is purchased from Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK). This database documents the use of different payment terms in export transactions originating from Turkey at the 2-digit level of ISIC Revision 3 and covers the years from 2002 to 2010. This data also reports the export markets, which allows us to examine the effect of variation in political risk on trade finance.

Table 1 shows the average use of post-shipment, pre-shipment, and letter of credit terms in Turkey’s exports over the years of our sample. As shown, open account (post-shipment) method has the lion’s share in export transactions. About 58% of exports were executed under open account terms. This observation gives a hint of the positive impact of political stability since Turkey’s exports are heavily concentrated on European markets. Payment methods with bank intermediation, letter of credit and documentary collection, constitute around 34% and cash-in-advance terms make around 5% of total exports. We also observe an increasing trend in the share of open account terms, whereas a decreasing one in the shares of cash against documents and letter of credit. These trends are more visible in the crisis period. We believe that increase in the letter of credit fees associated with financial meltdown was the main reason for the decrease in bank intermediation in export transactions.

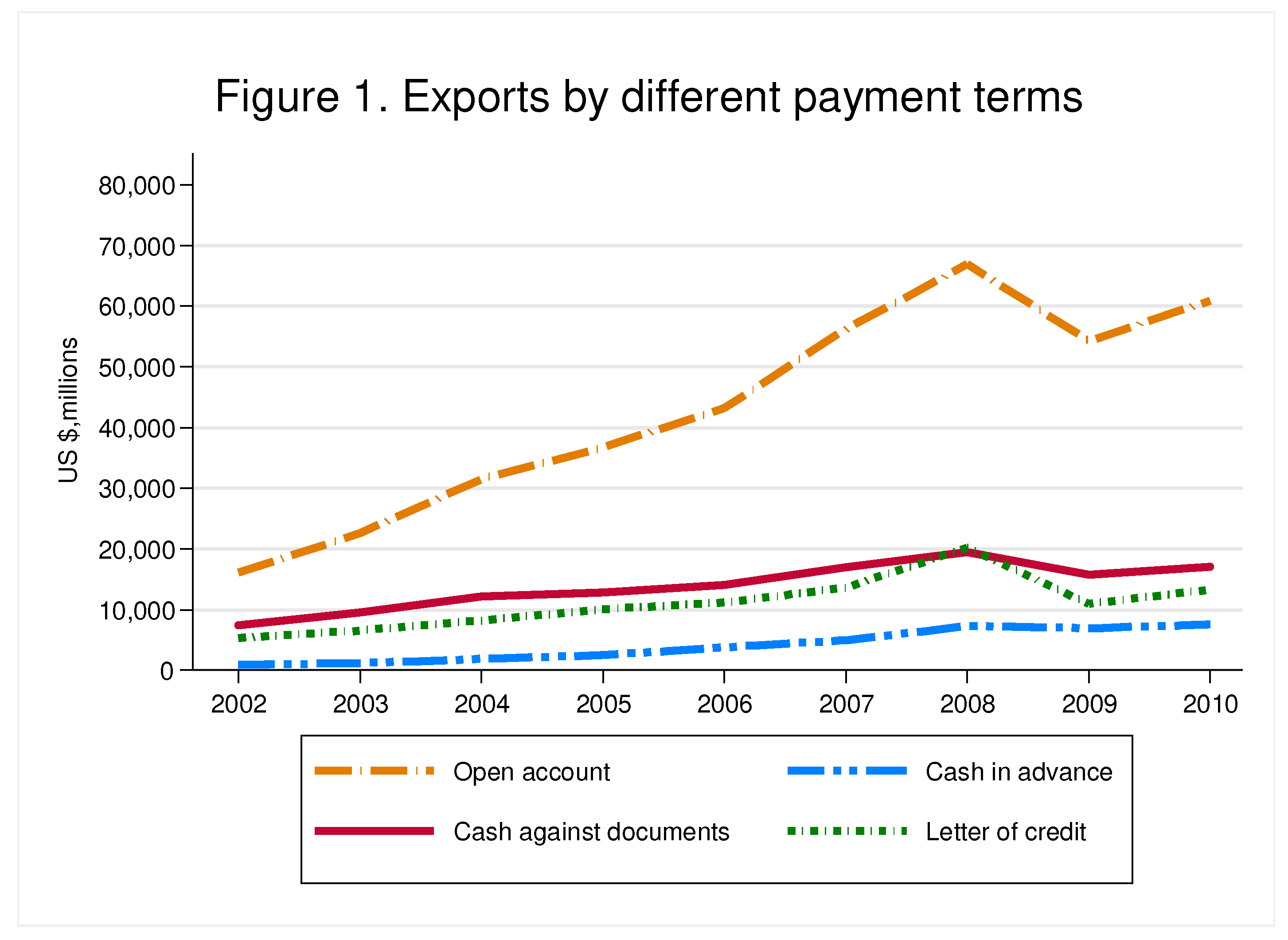

Figure 1 shows the trend of the value of exports for different payment terms. Open account transactions reached to more than 60 billion dollars in our sample, and it is by far the most preferred payment method. However, the increase in cash-in-advance transactions is also noteworthy. In fact, the value of exports under cash-in-advance increased from 500 million dollars to around 10 billion dollars from 2002 to 2010. Similar trend is also observed for cash against documents transactions. The value of exports executed under cash against documents terms almost doubled over the years of our sample. The drastic increase in pre-shipment terms can primarily be attributed to the shift in exports to the Middle Eastern countries. In fact, according to TUIK statistics, the same period witnessed an export increase of around 20 billion dollars to this region.

4 This finding is also parallel to our hypothesis on the relationship between political risk and trade finance since this period also coincides with anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that spread across North Africa and the Middle East regions.

In

Table 2, we document the export shares by payment terms for different regions. In support to our earlier discussions,

Table 2 shows that companies preferred more open account terms when exporting to European and North American countries, while more pre-shipment terms to regions with high political risk, such as Africa and Middle East. In fact, more than 50% of the export transactions to those regions were executed with a form of bank intermediation.

Table 2 provides suggestive evidence for our hypothesis that Turkish exporters are more prone to offering post-shipment terms to countries with less conflict and political stability.

In

Table 3, we present the shares of exports executed under post-shipment terms for 2-digit ISIC industries. In almost all industry categories, open account terms dominate the cross-border transactions. We also observe that high-tech industries (such as machinery, electrical machinery and chemicals) had larger shares in open account terms compared to low-tech industries (such as paper products, publishing and wood). The second column in

Table 3 shows the same averages for the exports to the countries that is above the median of

law-and-order rating, one of the measures of political risk in this paper. As shown, in almost all industry classifications, exporters extended more trade credit to the countries with better

law and order rating. This is another interesting observation from raw data that supports our hypothesis.

We gathered the information on political risk and from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) provided by the Political Risk Services (PRS) Group. Howell (2011) describes the variables and the methodology of the database. We used the following political risk components in our study: (1) Law and Order, which assesses the strength and impartiality of the legal system, (2) Democratic Accountability, a measure of how responsive government is to its people, (3) Bureaucratic quality, which rates the institutional strength and quality of the bureaucracy, (4) Military in politics, which represents the influence of military in politics, (5) External conflict, which weighs the risk to the government from foreign action, (6) Investment profile, an assessment of factors affecting the risk to investment, (7) Socioeconomic conditions, an evaluation of the socioeconomic pressures at work in society that could constrain government action, (8) Government stability, a measure of government’s ability to implement its policies and to stay in office, (9) Internal conflict, a measure of political violence within country. The political risk data are available monthly, and we use the annual average of the monthly indicators in our models.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix of Political Risk Variables.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix of Political Risk Variables.

| |

Law and Order |

Democratic Accountability |

Bureaucratic Quality |

Military in Politics |

External Conflict |

Investment Profile |

Socioeconomic Conditions |

Government Stability |

Internal Conflict |

| LO |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DA |

0.3034 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BQ |

0.625 |

0.5482 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MP |

0.618 |

0.5344 |

0.6987 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| EC |

0.2371 |

0.2675 |

3459 |

0.4581 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| IP |

0.6165 |

0.4939 |

0.6886 |

0.695 |

0.4368 |

1 |

|

|

|

| SC |

0.7437 |

0.3488 |

0.7745 |

0.6915 |

0.3248 |

0.7397 |

1 |

|

|

| GS |

0.1771 |

0.3625 |

0.0393 |

0.0023 |

0.1626 |

0.1206 |

0.1848 |

1 |

|

| IC |

0.5884 |

0.3086 |

0.4736 |

0.6447 |

0.5465 |

0.5557 |

0.5818 |

0.2319 |

1 |

Each measure has a different scale, but a higher value indicates less political risk for all of them. As it is to be expected, these measures are closely related to each other. For instance, as shown in

Table 4 above, partial correlation between bureaucratic quality and law and order is 0.63, which shows that strong legal system goes hand in hand with better institutions. There are other papers in the literature that uses the same dataset such as Busse and Hefeker (2007), Bove and Nistico (2014), Bilgin et al. (2017).

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Case

We are interested in the effect of different dimensions of political risk on trade finance. The data on method of payments from TUIK reports the exports transactions for each industry and export market combination. To empirically evaluate our hypothesis that industries extend more trade credit when political risk in the export destination is low, we begin with the following OLS specification:

where

denotes the share of export transactions settled under post-shipment terms (open account) in industry

i to export destination

j.

5 We also used the log of the value of exports executed under post-shipment terms as dependent variable in an alternative specification.

stands for one of the indicators for political risk and

is a set of control variables. Following Busse and Hefeker (2007), we add political risk indicators one by one to avoid multicollinearity. A high value in the political risk measure denotes a low risk for the export destination. Thus, we expect a positive sign for these variables.

Eisenlohr (2013)’s theory of trade finance suggests that an increase in the financing cost in a country makes it harder for its importers to offer cash in advance. For this consideration, we include net interest margin, the net interest income of the banks relative to their total earning assets, in the export destination as a control variable. We expect a positive sign for this variable. We also add the log of the total value of exports to the export destination in the previous year as another control variable. We believe that past trade create trust between global business partners, and it also gives them an opportunity to share information with companies in the same and other sectors. Therefore, we believe that industries are more likely to extend trade credit to their partners located in countries that had more trade volume with Turkey in the past. Some industry characteristics or product features like technology intensity may also affect the method of payments in cross border trade. To remedy this potential bias, we include the industry fixed effects. For the aggregate variations in Turkey such as business cycle, exchange rate and current account shocks, we used year fixed effects.

Table 5 displays the results. All columns include a suppressed constant term, year, industry, and country fixed effects. First, all the control variables have significant coefficients with expected signs. There is a positive relationship between net interest margin and the share of open account transactions in exports. This supports the results obtained in the earlier studies that financing cost in the importing country leads to an increase in exporter-financed trade. In addition, the coefficient estimates for the log of the value of past exports (all industries) are positive and significant in all specifications. This suggests that open account terms are more preferred when goods are shipped to countries that imported more goods from Turkey in the past.

When it comes to the variables of interest, all 9 political risk variables provide positive and significant estimates across different specifications. Turkish exporters extended more trade credit to destinations with lower risk. Consider specification 1 to gauge economic significance. If an export destination in the 25th percentile of law-and-order rating moves to the 50th percentile, such a switch will increase the share of post-shipment financed transactions by 2.1 percentage points. Similarly, if a country in the 50th percentile of law-and-order rating moves to the 75th percentile, around 1.4 percentage points increase is estimated in the share of exporter financed transactions resulting from this potential decrease in political risk.

Table 6.

Estimation Results: Dependent Variable: Log of value of Open Account Exports to country i in industry j.

Table 6.

Estimation Results: Dependent Variable: Log of value of Open Account Exports to country i in industry j.

| |

−1 |

−2 |

−3 |

−4 |

−5 |

−6 |

−7 |

−8 |

−9 |

| LO |

0.112 *** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

−0.02 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DA |

|

0.022 * |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

−0.013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BQ |

|

|

0.103 *** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

−0.024 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MP |

|

|

|

0.040 *** |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

−0.015 |

|

|

|

|

|

| EC |

|

|

|

|

0.035 ** |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

−0.016 |

|

|

|

|

| IP |

|

|

|

|

|

0.032 *** |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

−0.012 |

|

|

|

| SC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.027 ** |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

−0.011 |

|

|

| GS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.010 *** |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

−0.004 |

|

| IC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.005 *** |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

−0.001 |

| Control Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Log (Exports)it-1 |

1.327 *** |

1.333 *** |

1.322 *** |

1.330 *** |

1.337 *** |

1.326 *** |

1.327 *** |

1.336 *** |

1.336 *** |

| |

−0.013 |

−0.013 |

−0.014 |

−0.014 |

−0.013 |

−0.014 |

−0.014 |

−0.013 |

−0.013 |

| Net Interest Margin |

0.019 ** |

0 |

0.016 * |

0.005 |

0 |

0.006 |

0.01 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

| |

−0.009 |

−0.008 |

−0.009 |

−0.009 |

−0.008 |

−0.009 |

−0.009 |

−0.008 |

−0.009 |

| N |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

24886 |

We also estimate equation 1 with a different dependent variable, log of the value of exports occurred under post-shipment terms. Above,

Table 6 reports the results of this exercise. In line with the earlier results, all 9 political risk indicators are significant with expected signs. With respect to the size of the estimates, specification (1) indicates that a one-point increase in the government stability index in the importing country leads to a 11.8% increase in the value of exports occurred under open account terms.

4.2. Robustness Checks

Do our findings depend sensitively on a set of observations that comes from a special set of observations? We check by selectively dropping different sets of observations. We first drop the observations from Middle Eastern and North African region since the period in our dataset coincided with political uprisings in this region. We then successively delete observations for African, Asian, and European countries. In addition, we drop the observations from low income, low-middle income, upper-middle income, and high-income countries in different specifications. As shown, our findings remain salient. Political risk indicators enter significantly to our regressions with a positive sign.

Some readers may argue that our results are driven by traditional exporting sectors in Turkey. To address this concern, we also drop the observations from the top three exporting industries, textile, basic materials, and machinery, and estimate our model for the remaining industries. As documented in the last row of

Table 7, our results are insensitive to this treatment. Overall, none of the subsample analysis shakes the confidence we have in our main finding that increase in political risk in the export market is associated with a decrease in the share of exports executed under post-shipment terms.

We also subject our results to alternative estimations. We begin by the following probit model:

In this model, our dependent variable is a dummy and unity if the value of post-shipment financed transactions dominates the cash in advance and letter of credit transactions combined for an industry-importer combination. We estimate the probit model using the same set of control variables and political risk indicators.

Table 8 demonstrates the average marginal effects of the variables estimated from the probit model. Once again, all our political risk indicators remain positive and significant. For each additional increase in the rating for law and order, industries are 11% more likely to choose post-shipment terms over pre-shipment terms. Similarly, a point increase in the democratic accountability rating increases the likelihood of industries offering trade credit by 6%.

We also performed ordered logit regressions for method of payments in industries’ exports. To do so, we considered three groupings of export financing terms: pre-shipment terms, letter of credit, post-shipment terms.

6 Our dependent variable in this case takes on a value of 1 if majority of exports to a specific destination for an industry occurred under cash in advance (pre-shipment) terms. Similarly, it becomes 2 for letter of credit (bank intermediation) and 3 for open account (post-shipment) terms.

Table 9 documents the ordered logit estimations. We show the marginal effects of political risk variables on the probability of pre-shipment, bank intermediation and post-shipment terms in specifications 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Estimates suggest that political risk increase the likelihood of cash in advance and letter of credit terms whereas decreases the likelihood of post-shipment terms. According to the marginal effects reported in

Table 9, a one unit increase in bureaucratic quality index is associated with a 1.2% increase in the likelihood of having an export transaction under open account terms and a 0.4% decrease in the likelihood of cash in advance terms. Overall, both probit and ordered logit estimations confirm our hypothesis on the relationship between political risk and trade finance.

4.3. The Role of Industry Complexity

Carrying out a trade finance deal in complex, innovation intensive manufactured products require significant exchange of information between trade partners. Selling these complex products often requires relationship-specific arrangements, face-to-face interactions, quality controls and technical support as well as more dependence on financial institutions. In the periods of political instability and conflicts, importers of these industries will be more affected by the risk premiums, and it will be harder for the exporters to follow up on a payment in the case of a default. As a result, we believe that business partners in these industries will be more affected by political risks. To test whether the effect of political risk is more pronounced for complex industries, we interact our political risk variables with the industry complexity measures from Nunn (2007). Nunn (2007) develops the complexity measure using the input-output table from the US. In his classification, sectors that use a large share of intermediate inputs are classified as more complex.

Table 10 shows the estimates when we use the share of post-shipment financed exports as dependent variable and interact political risk indicators with the complexity measure. In all 9 specifications, both the political risk measures and the interaction terms are positive and significant. This suggests that the role of political risk in terms of extending trade finance is more important for complex industries. In an industry of low complexity (basic metals), one-point increase in the law-and-order rating increases the share of open account exports by around 1.1 percentage points, but the same change causes around 2 percentage points increase for an industry of high complexity (motor vehicles).

5. Conclusions

Serving international markets brings extra risks to companies, which they do not have in the domestic side. One of the risks in global business is the political risk which arises from governments’ policies and actions that can directly affect business operations and firms’ ability to perform their economic obligations. Political instability is on the rise worldwide. Ten years of data in the Fragile State Index indicate that the number of states in the ‘high alert’ and ‘very high alert’ categories more than doubled in the last 15 years. Studies have shown the negative impact of political risks on foreign trade and investment. In this paper, we complement and extend this line of research by analyzing the effect of political risk on trade finance. Trade finance is the lifeblood of cross border transactions and has become a central concern of governments especially after the trade collapse in the aftermath of global financial crisis. Our paper suggests that one of the channels through which political risks dampen global trade flows is the payment channel.

Political risk in the importer’s country increases the risk premium in financial markets and drives up the cost of financing, which makes it harder for the buyer to offer cash in advance. Second, sellers will perceive higher risks in terms of following up on their payments and thus be reluctant to extend trade credit when there is political instability and repression in export markets. In line with these arguments, we hypothesize that export transactions executed under open account terms increase if the political risk in the export markets decreases. Using industry-level trade finance data from Turkey, which reports payment methods for importer-industry combinations, and applying linear as well as maximum likelihood models, we provide strong support for this hypothesis. We also show that the political risk disproportionately affects the industries that produce complex products in terms of extending trade finance.

There are several avenues for future research in this area. For instance, it would be interesting to investigate the effect of political risk on the currency choice in export transactions. Does political risk increase the usage of vehicle currency in trade, rather than importing country’s currency? Answering this question can increase our understanding of the effect of political risk on international trade and finance. Political risk in the export destination may also impact the delivery methods and trade insurance policies in cross border transactions as well. However, pursuing these research questions require more detailed cross border data on payments and insurance policies.

Notes

| 1 |

We discuss these in more detail in the next section of the paper. |

| 2 |

Chauffour and Farole (2009). |

| 3 |

Turkcan and Avsar (2018), Avsar (2020) and Demir and Javorcik (2018) are the only exceptions in this regard. |

| 4 |

Total exports to Middle Eastern countries were recorded about 3 billion dollars in 2002, and more than 23 billion dollars in 2010. This increase represents the largest regional jump over those years in Turkish exports. |

| 5 |

Following Antras and Foley (2013), we classified the open account and documentary collection as post-shipment terms. |

| 6 |

Antras and Foley (2015) has a similar estimation using multinomial logit. |

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in all aspects of this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from TUIK (third party). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of TUIK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript, particularly in the tables:

| D_Mena: |

Drop Mena Countries |

| D_African: |

Drop African Countries |

| D_Asian: |

Drop Asian Countries |

| D_European: |

D_European Countries |

| D_LowInc: |

Drop Low Income Countries |

| D_LMInc: |

Drop Lower Middle-Income Countries |

| D_UMInc: |

Drop Upper Middle-Income Countries |

| D_HighInc: |

Drop High Income Countries |

| D_Textile&Basic Materials & Machinery and Equipment: |

Drop Textile&Basic Materials & Machinery and Equipment |

| LO: |

Law and Order |

| DA: |

Democratic Accountability |

| BQ: |

Bureaucratic Quality |

| MP: |

Military in Politics |

| EC: |

External Conflict |

| IP: |

Investment Profile |

| SC: |

Socioeconomic Conditions |

| GS: |

Government Stability |

| IC: |

Internal Conflict |

References

- Ahn, J., & Sarmiento, M. (2013). Estimating the direct impact of bank liquidity shocks on the real economy: Evidence from letter-of-credit import transactions in Colombia. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Anderson, J. E., & Marcouiller, D. (2002). Insecurity and the pattern of trade: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and statistics, 84(2), 342-352.

- Antras, P., & Foley, C. F. (2015). Poultry in motion: A study of international trade finance practices. Journal of Political Economy, 123(4), 853-901.

- Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. E. (2011). Exports and financial shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1841-1877.

- Auboin, M., & Engemann, M. (2014). Testing the trade credit and trade link: evidence from data on export credit insurance. Review of World Economics, 150(4), 715-743.

- Avsar, V. (2020). Travel Visas and Trade Finance. Economics Bulletin, 40(1), 567-573.

- Beck, T. (2003). Financial dependence and international trade. Review of International Economics, 11(2), 296-316.

- Berkowitz, D., Moenius, J., & Pistor, K. (2006). Trade, law, and product complexity. the Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(2), 363-373.

- Bove, V., & Nistico, R. (2014). Military in politics and budgetary allocations. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(4), 1065-1078.

- Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European journal of political economy, 23(2), 397-415.

- Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2012). Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. Journal of international economics, 87(1), 117-133.

- Demir, B., & Javorcik, B. (2018). Don’t throw in the towel, throw in trade credit!. Journal of International Economics, 111, 177-189.

- Glady, N., & Potin, J. (2011). Bank intermediation and default risk in international trade-theory and evidence. ESSEC Business School, mimeo.

- Gur, N. Gur, N., & Avşar, V. (2016). Financial system, R&D intensity and comparative advantage. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 25(2), 213-239.

- Harms, P., & Ursprung, H. W. (2002). Do civil and political repression really boost foreign direct investments? Economic inquiry, 40(4), 651-663.

- Harms, P. (2002). Political risk and equity investment in developing countries. Applied Economics Letters, 9(6), 377-380.

- Hoefele, A., Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T., & Yu, Z. (2016). Payment choice in international trade: Theory and evidence from cross-country firm-level data. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 49(1), 296-319.

- Hur, J., Raj, M., & Riyanto, Y. E. (2006). Finance and trade: A cross-country empirical analysis on the impact of financial development and asset tangibility on international trade. World Development, 34(10), 1728-1741.

- Lensink, R., Hermes, N., & Murinde, V. (2000). Capital flight and political risk. Journal of international Money and Finance, 19(1), 73-92.

- Long, A. G. (2008). Bilateral trade in the shadow of armed conflict. International Studies Quarterly, 52(1), 81-101.

- Love, I. (2013). Role of Trade Finance. In The Evidence and Impact of Financial Globalization (pp. 199-212). Academic Press.

- Manova, K. (2008). Credit constraints, equity market liberalizations and international trade. Journal of International Economics, 76(1), 33-47.

- Manova, K., Wei, S. J., & Zhang, Z. (2015). Firm exports and multinational activity under credit constraints. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(3), 574-588.

- Morrow, J. D., Siverson, R. M., & Tabares, T. E. (1998). The political determinants of international trade: The major powers, 1907–1990. American political science review, 92(3), 649-661.

- Moser, C., Nestmann, T., & Wedow, M. (2008). Political risk and export promotion: evidence from Germany. World Economy, 31(6), 781-803.

- Niepmann, F., & Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2017). International trade, risk and the role of banks. Journal of International Economics, 107, 111-126.

- Nunn, N. (2007). Relationship-specificity, incomplete contracts, and the pattern of trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 569-600.

- Oh, C. H., & Reuveny, R. (2010). Climatic natural disasters, political risk, and international trade. Global Environmental Change, 20(2), 243-254.

- Olsen, M. (2013), “How Firms Overcome Weak International Contract Enforcement: Repeated Interaction, Collective Punishment and Trade Finance”, University of Navarra, IESE Business School, mimeo.

- Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2013). Towards a theory of trade finance. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 96-112.

- Solomon, B., & Ruiz, I. (2012). Political risk, macroeconomic uncertainty, and the patterns of foreign direct investment. The International Trade Journal, 26(2), 181-198.

- Van der Veer, K. J. (2015). The private export credit insurance effect on trade. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 82(3), 601-624.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).