1. Introduction

Financial inclusion is increasingly recognized as a critical driver of economic development, particularly in low-income countries. It refers to the process of ensuring that individuals and businesses have access to affordable and appropriate financial services, including savings accounts, loans, insurance, and payment systems (World Bank, 2021). The importance of financial inclusion lies in its ability to empower marginalized populations, enabling them to manage their finances effectively, invest in opportunities, and protect themselves against economic shocks (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

Micro insurance, a subset of financial services, specifically targets low-income individuals and micro-enterprises by providing affordable insurance products that cover various risks, such as health, life, property, and agricultural losses (Churchill & Matul, 2021). By mitigating financial risks, microinsurance plays a crucial role in enhancing the resilience of low-income populations, helping them to safeguard their assets and livelihoods against unforeseen events (Morduch, 2023).

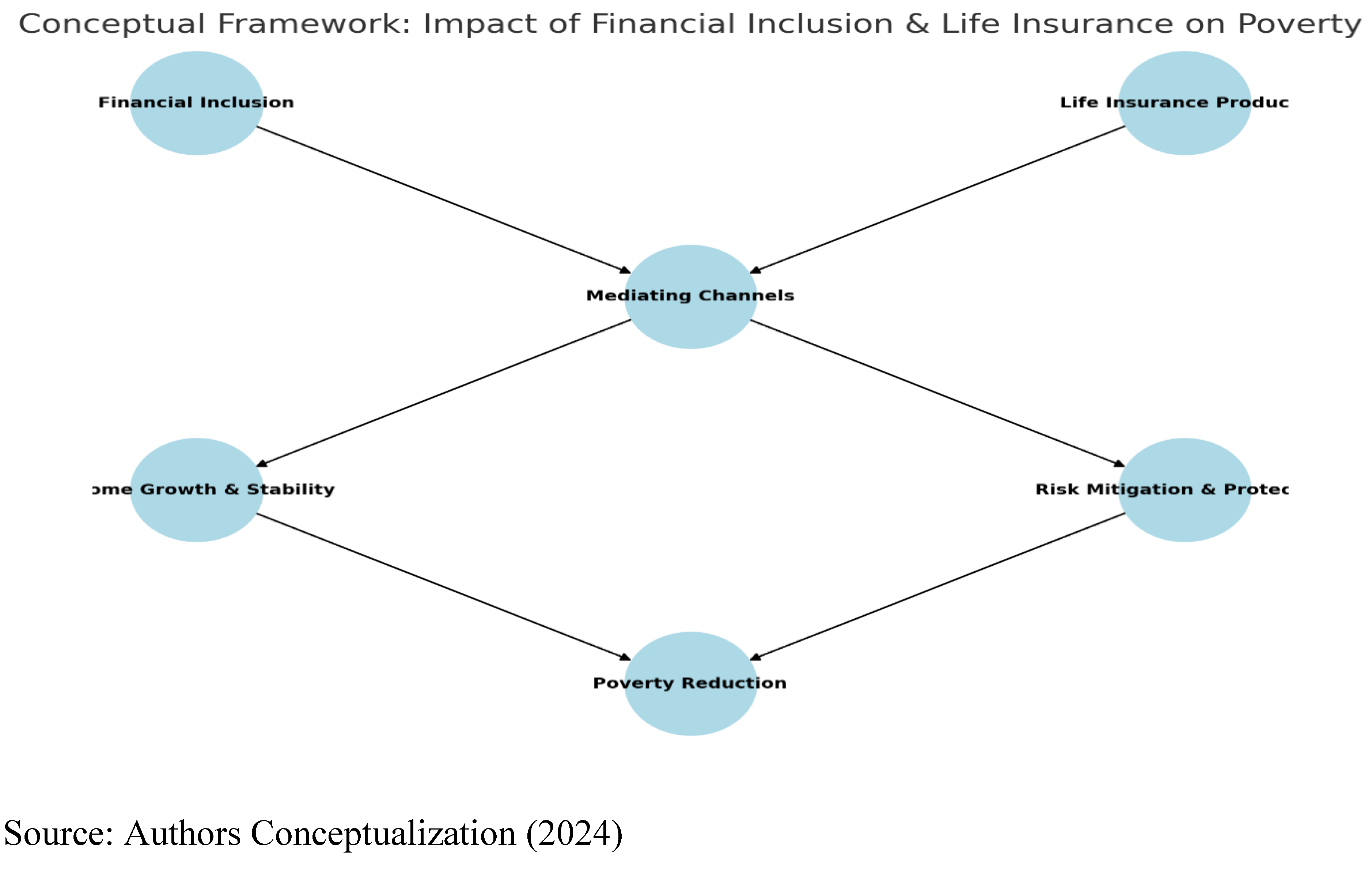

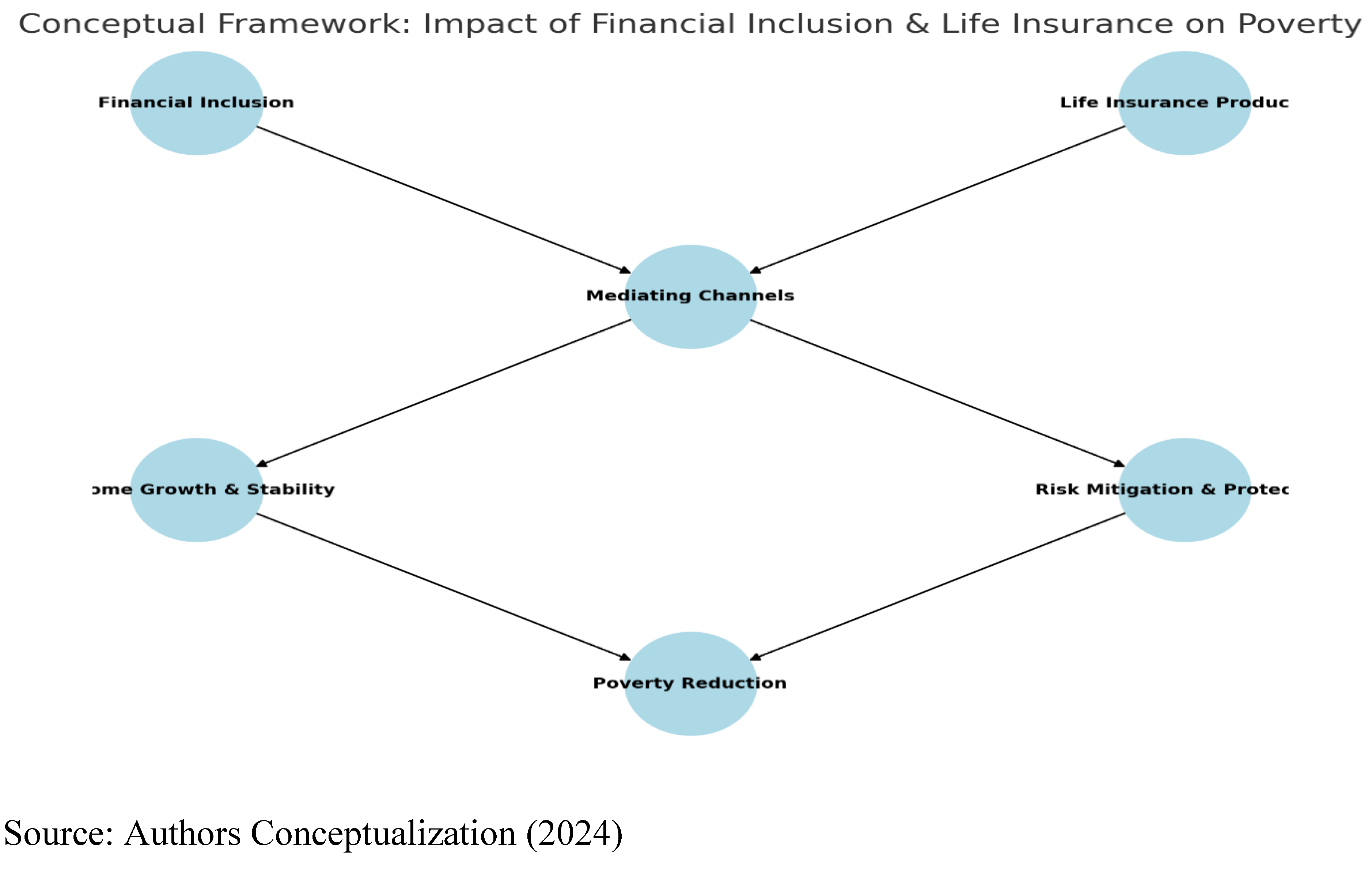

Despite the recognized benefits of financial inclusion and micro insurance, many low-income countries face significant challenges in achieving widespread penetration of these services. Barriers such as limited access to financial institutions, low financial literacy, high costs of services, and a lack of trust in formal financial systems hinder progress (Kumar & Singh, 2023). Additionally, micro insurance products often suffer from low awareness and complex designs, making it difficult for potential clients to understand and adopt them (Bhatia & Kaur, 2024).This study aims to explore the relationship between financial inclusion and life insurance in low-income countries, identifying key factors that influence this dynamic and the barriers that persist.

By understanding these elements, the research seeks to inform policymakers and financial institutions on effective strategies to enhance financial inclusion and micro insurance uptake, ultimately contributing to poverty alleviation and economic resilience in vulnerable communities. Despite global advancements in financial inclusion, significant gaps persist in ensuring equitable access to financial services for low-income populations in many developing countries. A considerable portion of individuals in these regions remain unbanked, and the uptake of micro insurance—an essential financial tool for mitigating risks such as health emergencies, natural disasters, and crop failures—remains alarmingly low. For example, it is estimated that only 11.5 percent of the potential market for micro insurance in low-income countries is currently served, leaving a vast 88.5percent protection gap (Micro insurance Network, 2023).

The problem is compounded by systemic barriers, including limited financial literacy, inadequate digital infrastructure, and the high costs of delivering financial services to remote areas. Furthermore, cultural and institutional factors hinder the adoption of insurance products, leaving millions vulnerable to economic shocks. Studies show that women and other marginalized groups are particularly underserved, even as they represent a significant segment of the market that could benefit from targeted inclusive financial solutions (Munich Re Foundation, 2021). Addressing these challenges is critical, as financial inclusion is closely linked to poverty alleviation and economic resilience. Understanding the interplay between financial inclusion efforts and microlife insurance is vital to designing policies and interventions that close the protection gap and support sustainable development in low-income countries (Center for Financial Inclusion, 2024).

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: section 2 presents the theoretical and empirical Review of literatures on impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Saharan countries, section 3 presents the data and methodology, section 4 presents the discussion of results, and section 5 presents the conclusions and policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Financial inclusion and micro life insurance are interconnected concepts critical to enhancing economic resilience and reducing poverty in Low-Income Countries (LICs). Financial inclusion, defined as the access and effective use of affordable financial services by underserved populations, forms the foundation for expanding microinsurance, a subset of inclusive insurance tailored to low-income individuals (World Bank, 2021). Financial inclusion has been widely recognized as a driver of economic growth, enabling individuals to save, invest, and access credit and insurance. Inclusive financial systems contribute to economic development by fostering entrepreneurship, reducing vulnerability to financial shocks, and improving income distribution (Center for Financial Inclusion, 2024). In LICs, financial inclusion efforts often focus on digitizing payment systems, promoting financial literacy, and developing regulatory frameworks conducive to innovation (Microinsurance Network, 2023).

Microinsurance is a low-cost, scalable financial product designed to address risks faced by vulnerable populations, such as health emergencies, crop failures, and climate-induced disasters. The penetration of microinsurance in LICs remains low, with only 11.5percent of the potential market covered in some regions (Microinsurance Network, 2023). The concept emphasizes affordability, accessibility, and relevance, offering solutions like weather-indexed crop insurance, community health insurance, and bundled financial products that include savings and insurance.

Financial inclusion plays a pivotal role in facilitating micro life insurance. A well-developed financial ecosystem allows for cost-efficient distribution channels, such as mobile money platforms, which reduce the administrative and transaction costs of insurance services. Mobile-based microinsurance initiatives, like those implemented in Kenya through M-Pesa, exemplify how financial inclusion infrastructure enhances insurance accessibility (Munich Re Foundation, 2021).

Conversely, microinsurance contributes to financial inclusion by building trust in formal financial institutions and encouraging participation in broader financial markets. When individuals experience the tangible benefits of micro insurance—such as receiving payouts during emergencies—they are more likely to adopt other financial services (Center for Financial Inclusion, 2024).

The theoretical underpinnings of financial inclusion and microlife insurance are multifaceted, drawing from economic, behavioural, and developmental frameworks. These theories collectively emphasize the importance of reducing barriers, leveraging intermediaries, and addressing behavioural challenges to expand access to financial services in LICs. Future efforts to enhance financial inclusion and microinsurance should incorporate insights from these theories to design scalable, sustainable, and impactful solutions.

Financial inclusion initiatives align closely with the Theory of Financial Intermediation, which posits that financial institutions play a critical role in reducing transaction costs, managing risks, and bridging information asymmetries in markets. In LICs, microinsurance providers rely on intermediaries such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), mobile network operators, and community-based organizations to distribute affordable insurance products. These intermediaries enhance access by leveraging existing networks, particularly in underserved regions (World Bank, 2021).

The Inclusive Growth Theory emphasizes the need for equitable economic growth that benefits all segments of society. Financial inclusion directly supports this theory by providing tools like savings, credit, and insurance to marginalized populations. Microinsurance, as a component of inclusive financial systems, ensures that vulnerable households can manage economic risks, preventing poverty traps and fostering more sustainable development (Microinsurance Network, 2023). The protection afforded by microinsurance enables households to invest in productive assets and participate more fully in economic activities.

The paper is anchored on Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) Theory and Institutional Theory. The DOI explains how innovations (e.g., financial services or insurance products) are adopted over time by a population. Financial inclusion promotes the diffusion of financial literacy and digital tools, which may increase awareness and trust in insurance products. It is relevance for this study Insurance products, particularly microinsurance, are innovations in low-income communities where financial inclusion initiatives like mobile money pave the way for adoption. Also, Institutional theory emphasizes the role of formal and informal structures (e.g., laws, norms, and organizations) in shaping behaviour. Financial inclusion initiatives often rely on institutional reforms to improve financial and insurance market accessibility. As Regulatory frameworks enabling mobile money and microinsurance are institutional changes that foster life insurance.

2.1. Empirical Review on the relationship between financial inclusion and life insurance

Empirical studies have explored the relationship between financial inclusion and life insurance in Low-Income Countries (LICs). Financial inclusion was empirically linked to improved economic resilience, poverty reduction, and income equality in LICs.

Micro insurance, a key component of financial inclusion, has demonstrated its potential to improve financial resilience among low-income households. Empirical evidence from Ghana and other LICs indicates that micro insurance provides a critical safety net against economic shocks, such as health emergencies and agricultural losses. For example, parametric insurance models, which trigger payouts based on predefined indices like rainfall levels, have been particularly effective in addressing rural risks. Despite these successes, the penetration rate remains low, with many LICs failing to exceed 12 percent market coverage due to affordability and infrastructure challenges (MAPFRE Economics, 2023; Microinsurance Network, 2023).

2.1.1. Financial Inclusion and Life insurance

The synergy between financial inclusion and microinsurance is evident in empirical research. Studies reveal that mobile money platforms and digital financial services significantly enhance microinsurance distribution by lowering transaction costs and improving accessibility. In Kenya, the integration of microinsurance with mobile platforms like M-Pesa has expanded coverage to previously unreachable demographics, illustrating the importance of leveraging digital infrastructure for inclusive insurance growth (Munich Re Foundation, 2021; World Bank, 2021).

Chummun (2017) investigated the relationship between mobile microinsurance and financial inclusion in developing countries. Through a review of literature, the author advances the hypothesis that inclusive financing is more likely to be successful in countries where mobile microinsurance is being used than countries where the service is not available to the low-income people. The study’s drive is predicated on the argument that mobile platform including mobile money can be used as a measure to mitigate the inherent transaction costs of microinsurance and to assist in the building of volume of microinsurance and mobile microinsurance policies. Despite some identified challenges, the findings revealed that leveraging use of relatively low-cost mobile channels of microinsurance could promote the effective accessibility of microinsurance, providing the opportunities to reach the low-income households in remote places and contribute to financial inclusion. Finally, the author points to some possible ways for mobilizing mobile microinsurance to enable effective financial inclusion.

Mbugua (2021) conducted a study in Kenya that utilized a cross-sectional descriptive survey to analyse the impact of microinsurance on life insurance. Factors like client education, regulatory frameworks, and innovative distribution channels were found to drive microinsurance adoption. The research found that microinsurance strategies, including financial literacy education and the use of technology, significantly improved insurance uptake among low-income households. The study highlighted the importance of affordable and flexible premium payment options in enhancing accessibility to microinsurance products.

Inyang and Okonkwo (2022) provided an integrative review of microinsurance schemes in Nigeria, identifying both opportunities and barriers to increasing life insurance. Their findings indicated Nigeria’s insurance sector suffers from under-penetration, contributing less than 1percent to GDP. This study highlights microinsurance's potential to increase penetration, leveraging Nigeria’s demographics, regulatory frameworks, and insures advancements. Barriers like low awareness and insufficient market research were identified, prompting recommendations for stakeholder initiatives and tailored microinsurance schemes. The authors emphasized the need for tailored products that meet the specific needs of low-income populations to improve engagement with microinsurance offerings.

Jain and Singh (2024) explored the transformative role of financial inclusion in the Indian insurance sector through a mixed-methods approach. Financial inclusion strategies have catalysed growth and innovation in India’s insurance sector. This review highlights how digital solutions and government-private initiatives have boosted penetration rates and product diversification. Their study revealed that microinsurance not only serves as a safety net for low-income individuals but also encourages savings and investment in small enterprises. The research underscored the significance of financial literacy programs in enhancing the understanding and utilization of microinsurance among economically disadvantaged communities.

VL and Mohan (2022) conducted a quantitative analysis to assess the impact of insurance inclusion on financial well-being in India. Their empirical findings demonstrated that households with access to microinsurance reported greater financial security and resilience against economic shocks. The study utilized a large sample size and employed statistical methods to analyse the data, confirming that microinsurance is vital for promoting financial inclusion and improving the overall economic stability of low-income households. The study notes that stagnant life insurance can be addressed through microinsurance products and technological integration, emphasizing the role of insurance in reducing vulnerabilities

Kajwang (2022) study on microinsurance and poverty alleviation revealed that Microinsurance is tailored for low-income groups, provides financial protection against risks while fostering resilience amidst vulnerabilities. The study used a desk research approach to evaluate its impact on poverty alleviation, finding that it protects the poor from shocks, supports gender-specific needs, and liberates household capital for small enterprises. The paper recommends increased government support, insurance literacy campaigns, and innovative strategies to raise awareness of microinsurance's benefits

Mose (2022) study addressed Kenya’s low life insurance rate of 2.43percent by exploring microinsurance strategies such as financial literacy, technological adoption, and product flexibility. Using descriptive surveys, the findings highlighted that microinsurance positively influences penetration through customer education and innovative distribution methods. The paper recommends stronger public-private partnerships to expand microinsurance. Anusha (2020) connected financial and insurance inclusion, focusing on microinsurance’s role in spreading financial services to rural areas. It suggests that policies aimed at simultaneous financial and insurance inclusion can enhance equity and drive sustainable growth, particularly in underserved areas

Overall, the empirical evidence highlights the significant relationship between financial inclusion and microlife insurance in low-income countries. Studies consistently emphasize the importance of client education, tailored product offerings, and supportive regulatory frameworks in enhancing access to microinsurance. Integrating microinsurance into broader financial inclusion strategies is essential for fostering economic resilience among vulnerable populations.

2.1.2. Financial inclusion and poverty

Lal (2018) examined the impact of financial inclusion on poverty alleviation. In order to fulfil the objectives of the study, primary data were collected from 540 beneficiaries of cooperative banks operating in three northern states of India, i.e., J&K, Himachal Pradesh (HP) and Punjab using purposive sampling during July-December 2015. The technique of factor analysis had been used for summarisation of the total data into minimum factors. For checking the validity and reliability of the data, the second-order CFA was performed. Statistical techniques like one-way ANOVA, t-test and SEM were used for data analysis. The study results reveal that financial inclusion through cooperative banks has a direct and significant impact on poverty alleviation. The study highlights that access to basic financial services such as savings, loans, insurance, credit, etc., through financial inclusion has generated a positive impact on the lives of the poor and help them to come out of the clutches of poverty.

Tran and Le (2021) examined the financial inclusion- poverty nexus of 29 European nations between 2011 and 2017. Based on panel data from 29 European nations between 2011 and 2017, 2SLS and GMM regressions reveal that financial inclusion has a negative effect on poverty at all three poverty lines of USD 1.9, USD 3.2, and USD 5.5 per day. All three levels of POV1.9, POV3.2, and POV5.5 are negatively impacted by the percentage of the population between the ages of 15 and 64 as well as the ratio of service employment to total employment. On the other hand, the percentage of people aged 25 and older who have completed at least secondary school, GDP per capita, and trade openness all positively affect poverty at all three levels.

Tran, Le, Nguyen, Pham, and Hoang (2022) assessed how financial inclusion affected multifaceted poverty reduction, particularly with regard to household use of financial products and services. This study estimates the impact of financial inclusion on household use of financial products and services, as well as other factors, on multidimensional poverty using a multivariate probit model using a Vietnamese dataset. The findings demonstrate that multifaceted poverty is decreased by financial inclusion. In particular, households are less likely to experience multidimensional poverty if they have bank accounts, saves at banks, use credit or debit cards, or invest in stocks or bonds. In light of the results, we provide a number of suggestions to legislators in an effort to boost household usage of financial services and products.

Sakanko (2023) used primary data gathered from 624 questionnaires to examine the effect of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in 224 towns and villages spread over 12 Local Government Areas in Niger State, Nigeria. In order to do this, the study used the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation techniques along with the logistics regression and Probit regression models. The findings show that while age has a negative impact on financial inclusion in Niger State, gender, education, literacy, income, social security, and phone availability are all important positive drivers of financial inclusion. Furthermore, the OLS results show that while the literacy rate shows a position that reduces income, account ownership, bank access, social security access, and employment all have a favourable impact on income levels.

In summary, to best of the knowledge of the authors there exist no empirical literature directly examining the moderating effect of life insurance on the financial inclusion-poverty nexus this therefore form the crux of this research.

3. Data and Methodology

This section presents the methodology for investigating the life insurance on financial inclusion in SSA countries. Data for this study was obtained from World Bank Global Financial Development Database and World Bank Development Indicators Database. All data was converted from annual data to quarterly data using E-View tool-kits.

Table 1.

Data, data proxies, variable measurement and sources.

Table 1.

Data, data proxies, variable measurement and sources.

| S/N |

Variable |

Proxies |

Variable measurement |

Source(s) |

| 1 |

Financial Inclusion Index (FII) |

Author’s computation1 of Financial Inclusion Index (FII)

World Bank Global Financial Development DatabaseWorld Bank Global Financial Development Database

Author’s computation2 |

| Usability |

Bank credit to bank deposits |

Quarterly |

| Accessibility |

Commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults |

Quarterly |

| Concentration |

Concentration of banks (percent) |

Quarterly |

| Availability |

Depositors with commercial banks (per 1000 adults) |

Quarterly |

| 2 |

Life insurance |

| |

LIFINSUR |

Life insurance premium volume to GDP (percent) |

Quarterly |

| 3 |

Poverty |

| |

POV |

Multidimensional poverty headcount ratio (UNDP) (percent of population) |

Quarterly |

| 4 |

Interactive term of financial inclusion and Life insurance |

| |

|

is the interaction term between financial inclusion and life insurance |

Quarterly |

| |

Control Variables |

|

| 5 |

INFL |

Inflation |

Quarterly |

World Bank

Development Indicators Database

World Bank

Development Indicators Database

World Bank

Development Indicators Database |

| 6 |

GRO |

Economic growth

(GDP per capita) |

Quarterly |

| 7 |

TO |

Trade openness = |

Quarterly |

Econometric Model Specification

The various variables included in the model specification are calibrated in line with work of (Wong, Badeeb, & Philip, 2023) to investigate the moderating effect of life insurance on the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty in SSA countries as follows

where, FI is financial Inclusion, INSUR is life insurance and

is the interaction term between financial inclusion and life insurance. This interaction term is expected to indicate the impact of life insurance on the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty. At the margin, the total effects of life insurance can be calculated by examining the partial derivative of poverty with respect to financial inclusion.

The equation reveals the marginal effect of financial inclusion on poverty changes with respect to the level of life insurance. The sign of coefficient of the interaction term shows its moderating effect. However, if is negative and the interactive term coefficient has a positive sign. It indicates that a rise in life insurance would enhance the negative impact of financial inclusion on poverty. If and are negative, it would indicate that life insurance retards the positive effects of financial inclusion on poverty.

Source: Author (2024)

Table 2.

Variables expected theoretical sign.

Table 2.

Variables expected theoretical sign.

| S/N |

Variable |

Expected Sign |

| 1 |

Multidimensional poverty headcount ratio (UNDP) (percent of population) |

|

| 2 |

FI is Financial Inclusion Index |

+ |

| 3 |

INSUR is life insurance proxied by Life insurance premium volume to GDP (percent) |

+ |

| 4 |

is the interaction term between financial inclusion and life insurance * |

+/- |

| 5 |

Inflation |

+ |

| 6 |

Economic growth (GDP per capita) |

+ |

| 7 |

Trade openness = |

+ |

*This interaction term is expected to indicate the impact of Life insurance on the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty. However, if is negative and the interactive term coefficient has a positive sign. It indicates that a rise in life insurance would enhance the negative impact of financial inclusion on poverty. If and are negative, it would indicate that life insurance retards the positive effects of financial inclusion on poverty.

4. Results

The summary of statistics is important to explore the time-series distribution of the data collected on each of the variables. The table 3 indicates that all variables used as endogenous variable for poverty are positive. This reveals that on the average all the endogenous variables. For instance, the mean distribution of the poverty reduction in SSA. This is a pointer to the fact that SSA countries poverty reduced as a result of the joint impacts of joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance.

Table 3.

Summary of Descriptive statistics for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa from 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

Table 3.

Summary of Descriptive statistics for the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa from 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

| |

POVR |

FII |

INSUR |

FIINSUR |

INFL |

TO |

GRO |

| Mean |

17.87146 |

-0.087919 |

0.554257 |

0.230332 |

9.691020 |

56.87562 |

1694.168 |

| Median |

16.57316 |

0.000000 |

0.036539 |

0.000000 |

5.289867 |

54.36966 |

860.9715 |

| Maximum |

44.62394 |

5.084794 |

15.38098 |

30.66771 |

513.9068 |

175.7980 |

14222.55 |

| Minimum |

0.000000 |

-1.612566 |

0.000000 |

-3.524327 |

-16.85969 |

0.000000 |

-17.00469 |

| Observations |

944 |

944 |

944 |

944 |

944 |

944 |

944 |

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix of the variables used in the model. The correlation matrix shows the degree of association and direction of relationship among the variables. Results in the table show that there exists a negative relationship among poverty, financial inclusion, life insurance, interactive term of financial inclusion and life insurance (FIInsur), inflation, trade openness (TOP), and growth. It can be deduced that all independent variables can be included in the same model without the fear of multicollinearity.

Various studies such as (Anifowose, Adeleke, & Mukorera, 2019) among others have advised researchers to always use more than one method of panel unit root test in order to be sure of the order of integration of the variables to be included in a particular model. The reason behind this might not be unconnected to the fact that a non-stationary variable constitutes an outlier among other variable and the inclusion can significantly influence the outcome of the empirical analysis. For this study both the ADF and PP methods of Panel unit root tests are adopted for consistency’s sake. Their results are presented in table

Table 5.

Panel Unit root test for the joint impacts of the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

Table 5.

Panel Unit root test for the joint impacts of the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

| |

Augmented Dickey -Fuller Unit root test |

Phillips-Perron unit root test |

Status |

| |

Level |

First Diff |

Level |

First Diff |

| Variables |

Stat. |

P-Val |

Stat. |

P-Val |

Stat. |

P-val. |

Stat |

P-val |

| POV |

-1.300918 |

0.1773 |

-2.6187 |

0.0093 |

-0.5202 |

0.4889 |

-4.7495 |

0.0000 |

I (1) |

| FI |

-1.8141 |

0.0664 |

-3.0997 |

0.0022 |

-1.1810 |

0.2158 |

-3.3598 |

0.0000 |

I (1) |

| INSUR |

-1.0146 |

0.2769 |

-2.3442 |

0.0195 |

-0.9816 |

0.2902 |

-3.9692 |

0.0001 |

I (1) |

| FIINS |

-1.588 |

0.1052 |

-2.8445 |

0.0048 |

-0.9934 |

0.2854 |

-3.0662 |

0.0025 |

I (1) |

| INFL |

-2.1507 |

0.0310 |

-3.8391 |

0.002 |

-1.2701 |

0.1868 |

-4.0576 |

0.001 |

I (1) |

| TOP |

-0.0935 |

0.6487 |

-2.2319 |

0.026 |

0.2346 |

0.7522 |

-3.3962 |

0.0009 |

I (1) |

| GRO |

1.1222 |

0.9314 |

-3.0934 |

0.0023 |

1.9196 |

0.9865 |

-3.3502 |

0.0010 |

I (1) |

After identifying the order of integration of the variables, the next step was to determine if the variables share a long run equilibrium relationship. For this test, the Pedroni Residual Cointegration Test is used to determine whether a set of non-stationary time series are cointegrated, meaning they share a long-term equilibrium relationship despite potential short-term fluctuations.

Table 6.

Pedroni Panel Cointegration Test results.

Table 6.

Pedroni Panel Cointegration Test results.

| Pedroni Residual Cointegration Test |

| Sample: 1999 2023 |

| Included observations: 1125 |

| Cross-sections included: 24 (21 dropped) |

| Null Hypothesis: No cointegration |

| Trend assumption: No deterministic trend |

| User-specified lag length: 1 |

| Newey-West automatic bandwidth selection and Bartlett kernel |

| Alternative hypothesis: common AR coefs. (within-dimension) |

| |

Statistic |

Prob. |

Weighted Statistic |

Prob. |

| Panel v-Statistic |

-0.459862 |

0.6772 |

-3.492881 |

0.9998 |

| Panel rho-Statistic |

-0.654990 |

0.2562 |

0.519885 |

0.6984 |

| Panel PP-Statistic |

-17.39254 |

0.0000 |

-13.41169 |

0.0000 |

| Panel ADF-Statistic |

-1.981620 |

0.0238 |

-2.282931 |

0.0112 |

| Alternative hypothesis: individual AR coefs. (between-dimension) |

| Group rho-Statistic |

Statistic |

Prob. |

|

|

| 1.741184 |

0.9592 |

|

|

| Group PP-Statistic |

-19.86679 |

0.0000 |

|

|

| Group ADF-Statistic |

-1.610455 |

0.0536 |

|

|

The Panel PP-Statistic and Panel ADF-Statistic strongly reject the null hypothesis, suggesting the existence of cointegration. Also, the Panel v-Statistic and Panel rho-Statistic fail to reject the null hypothesis, but these are less powerful in many cases compared to the PP and ADF statistics. Based on the significant Panel PP-Statistic and Panel ADF-Statistic, there is evidence to suggest that the series are cointegrated, meaning they share a long-term equilibrium relationship. Further analysis, such as estimating the long-term relationship using an error correction model (ECM), can provide insights into the dynamics among these variables.

Table 7.

Impact of Financial inclusion and Life insurance on poverty in SSA countries.

Table 7.

Impact of Financial inclusion and Life insurance on poverty in SSA countries.

| ARDL Long Run Form and Bounds Test |

|

|

|

|

| Dependent Variable: D(POV) |

|

|

|

|

| Selected Model: ARDL(1, 1, 4, 4, 1, 0, 1) |

|

|

|

|

| Case 2: Restricted Constant and No Trend |

|

|

|

|

| Sample: 1999Q1 2023Q4 |

|

|

|

|

| Included observations: 96 |

|

|

|

|

| Conditional Error Correction Regression |

|

|

|

|

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

| C |

14,76683 |

4,63495 |

3,185974 |

0,0021 |

| POVRED(-1)* |

-0,58083 |

0,058081 |

-10,0005 |

0.0000 |

| FII(-1) |

-1,77413 |

2,608128 |

-0,68023 |

0,4984 |

| INSUR(-1) |

10,16912 |

1,913961 |

5,313129 |

0.0000 |

| FI_INSUR(-1) |

1,326426 |

2,170821 |

0,611025 |

0,543 |

| INFL(-1) |

0,05442 |

0,038452 |

1,41525 |

0,161 |

| TO** |

0,021312 |

0,060642 |

0,351443 |

0,7262 |

| GRO(-1) |

-0,00657 |

0,00306 |

-2,14819 |

0,0348 |

| D(FII) |

11,09885 |

4,992058 |

2,223301 |

0,0291 |

| D(INSUR) |

7,633998 |

3,508842 |

2,175646 |

0,0326 |

| D(INSUR(-1)) |

-7,11253 |

3,048546 |

-2,33309 |

0,0223 |

| D(INSUR(-2)) |

-7,11253 |

3,048546 |

-2,33309 |

0,0223 |

| D(INSUR(-3)) |

-7,11253 |

3,048546 |

-2,33309 |

0,0223 |

| D(FI_INSUR) |

-10,49 |

3,128879 |

-3,35264 |

0,0012 |

| D(FI_INSUR(-1)) |

-4,73752 |

2,136045 |

-2,2179 |

0,0295 |

| D(FI_INSUR(-2)) |

-4,73752 |

2,136045 |

-2,2179 |

0,0295 |

| D(FI_INSUR(-3)) |

-4,73752 |

2,136045 |

-2,2179 |

0,0295 |

| D(INFL) |

0,265815 |

0,062902 |

4,225891 |

0,0001 |

| D(GRO) |

0,005477 |

0,006712 |

0,815905 |

0,4171 |

| * p-value incompatible with t-Bounds distribution. |

| ** Variable interpreted as Z = Z(-1) + D(Z). Levels Equation |

| Case 2: Restricted Constant and No Trend |

|

|

|

|

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

| FII |

-3,05445 |

4,482203 |

-0,68146 |

0,4976 |

| INSUR |

17,50779 |

2,93155 |

5,972196 |

0.0000 |

| FIINSUR |

2,283658 |

3,730642 |

0,612135 |

0,5423 |

| INFLATION |

0,093692 |

0,066244 |

1,414357 |

0,1613 |

| TRADEOPP |

0,036693 |

0,10393 |

0,353052 |

0,725 |

| GRO |

-0,01132 |

0,005189 |

-2,18122 |

0,0322 |

| C |

25,4235 |

7,849006 |

3,239072 |

0,0018 |

| EC = POVRED - (-3.0544*FII + 17.5078*INSUR + 2.2837*FI_INSUR + 0.0937*INFL + 0.0367*TO-0.0113*GRO+ 25.4235) |

5. Results and Discussion

This research used P-ARDL technique to measure the impact of financial inclusion. Table 8 present the ARDL Bounds Test and the associated error correction model for determining the short-run and long-run relationships between poverty (POV) and several explanatory variables.

The coefficients in the "Levels Equation" reveal the long-term effects of the independent variables on poverty reduction (POV). The coefficient for FII (-3.05) indicates that an increase in the financial inclusion index (FII) is associated with a reduction in poverty. However, this result is not statistically significant (p = 0.498). This insignificance may stem from low financial literacy in Sub-Saharan African countries, which limits the ability of low-income earners to effectively and efficiently access financial services. Additionally, the result may reflect the broader impact of financial inclusion on different income groups, rather than exclusively benefiting the low-income segment, thereby diluting its specific effect on poverty reduction. The result is similar to the findings of (Turegano & Herrero, 2018).

The coefficient for life insurance (INSUR) is significant and positive (coef. = 17.51, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher insurance levels contribute significantly to poverty reduction in the long run. This finding aligns with the results of Chummun (2017). However, the interactive term of financial inclusion and insurance performance (FIINSUR) is not statistically significant (p = 0.542), contrasting with the findings of Chummun (2017).

The inflation coefficient (0.0937) implies a weak and insignificant effect of inflation on poverty reduction (p = 0.1613). Trade openness (TRADEOPP) shows no significant relationship (p = 0.725). The Economic growth (GRO)has a significant negative effect (coef. = -0.0113, p = 0.0322). This might suggest that while GDP per capita increases, poverty reduction does not proportionally follow due to inequality or other factors. The constant term Constant (C) (25.42) represents the baseline level of poverty reduction when all variables are at zero.

The error correction term, POV (-1), has a significant negative coefficient (-0.5808, p < 0.001), confirming the presence of a long-run relationship. The adjustment speed is 58.08percent, meaning that over half of any short-run disequilibrium is corrected in the next period. Key short-run effects include: D(FII): Positive effect (coef. = 11.10, p = 0.0291), indicating a short-run benefit of financial inclusion. D(INSUR): Mixed results; while the initial effect is positive (coef. = 7.63, p = 0.0326), the lagged terms are negative and significant, suggesting dynamic effects over time. D(FI_INSUR): Significant negative impact across lags, implying that the interaction between financial inclusion and life insurance may introduce complex and potentially detrimental short-term dynamics. D(INFLATION): Positive and significant effect (coef. = 0.265, p < 0.001), highlighting a short-term inflationary boost to poverty reduction (GRO): Insignificant effect (p = 0.4171).

6. Conclusions and Policy Implication

This study has explored how life insurance may moderate the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty, which indicate that financial inclusion and life insurance products have a positive and insignificant impact on poverty in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, it suggests that while these factors may be associated with poverty reduction, their effects are not strong or statistically reliable. This imply that there is limited penetration and usage, that is financial inclusion and life insurance might not be widespread or effectively utilized by the poor. Many individuals may have access to financial services but are not actively using them in ways that significantly reduce poverty. Secondly, there is low Financial Literacy – People might not fully understand or trust financial services, including life insurance, leading to underutilization or misuse. Thirdly, it indicates that there exist short-term versus long-Term Effects that is, the benefits of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty reduction might take longer to materialize, and the study period may not have captured the long-term effects. Furthermore, there could be structural constraints such as other economic and institutional factors (such as weak governance, corruption, or inadequate infrastructure) could be limiting the effectiveness of financial services in reducing poverty as well as insurance design issues, that is life insurance, in particular, may not directly alleviate poverty in the short term, as benefits are often realized only upon death or after long periods. If policies are not tailored to the needs of the poor, their impact may be minimal. More so, there could be credit usage and indebtedness i.e. if financial inclusion primarily increases access to credit without corresponding productive investments, it may not significantly reduce poverty and, in some cases, could lead to over-indebtedness.

Inconclusion it revealed that there could be measurement and data Limitations, that is the insignificant impact could also be due to data limitations or methodological issues in the study, such as small sample sizes or omitted variable bias. Future research could consider investigating additional potential moderators that could strengthen this relationship. For example, financial literacy might serve as a significant moderator, as a better understanding and awareness of financial products and services could enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their use, particularly among lower-income segments.

2024 World Bank Classification of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries.

| S/N |

Country Name |

World Bank Classification |

Ranking |

| 1 |

Angola |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 2 |

Benin |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 3 |

Botswana |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 4 |

Burundi |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 5 |

Cabo Verde |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 6 |

Cameroon |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 7 |

Central Africa Republic |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 8 |

Chad |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 9 |

Comoros |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 10 |

Congo Democratic Republic |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 11 |

Congo Republic |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 12 |

Cote d’Ivoire |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 13 |

Equatorial Guinea |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 14 |

Eritrea |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 15 |

Liberia |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 16 |

Eswatini |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 17 |

Ethiopia |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 18 |

Gabon |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 19 |

Gambia |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 20 |

Ghana |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 21 |

Guinea |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 22 |

Guinea Bissau |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 23 |

Kenya |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 24 |

Lesotho |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 25 |

Seychelles |

High Income Country |

**** |

| 26 |

Madagascar |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 27 |

Malawi |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 28 |

Mali |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 29 |

Somalia |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 30 |

Mauritania |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 31 |

Mauritius |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 32 |

Mozambique |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 33 |

Namibia |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 34 |

Nigeria |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 35 |

Rwanda |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 36 |

Sao tome and Principe |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 37 |

Senegal |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 38 |

Sierra-Leone |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 39 |

South Africa |

Upper Middle-Income Country (UMC) |

*** |

| 40 |

Sudan-Sudan |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 41 |

Tanzania |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 42 |

Togo |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 43 |

Uganda |

Low Income Country (LIC) |

* |

| 44 |

Zambia |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

| 45 |

Zimbabwe |

Lower Middle-Income Country (LMC) |

** |

Source: World Bank (2024) https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Appendix

| S/N |

Country |

financial inclusion |

life insurance products |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Publication and research Funding

University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Private Box X54001, Durban, 4000, South Africa. VAT: 4860209305

Notes

| 1 |

The authors’ employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) technique in construction of Financial Inclusion Index (FII) for forty-five (45) Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries in this study. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) technique adopted the methodological procedures of the works of (Gupte, Venkataramani, & Gupta, 2012; Tram, Lai, & Nguyen, 2023). In this approach, through a two-stage principal component analysis (PCA) method, appropriate weights were obtained to assign dimensions and individual indicators that measure the level of financial inclusion. The first stage applies the PCA method to estimate three sub-indices, that is, the dimensions that represent financial inclusion (penetration, availability, and usage). The second stage also applies the PCA method to estimate the overall FI index using three sub-indices estimated at the first stage as causal variables, which implies that we estimate the sub-metrics first instead of estimating the overall financial inclusion index directly by selecting all indicators simultaneously. This approach is considered an optimal strategy because it avoids weight bias against the indicators that exhibit the highest correlation..

However, the constructed Financial Inclusion Index (FII) annual data for 45 SSA countries was converted into quarterly data using E-view 13 tool kits, which makes it unique from the previous construction of Financial Inclusion Index (FII) studies which are constructed in annual format alone. See the constructed financial inclusion index values in annual data format for all SSA countries in Microsoft Excel employed in this study.

In conclusion, the works of Gupte et al., (2012) is limited in scope and number of variables selected which focused on India alone while this financial inclusion index captured a longer time frame and numbers of countries in a quarterly form which gives a clearer policy implication for policy makers in each of these countries therefore contributing to the body of knowledge on financial inclusion.

|

| 2 |

Interaction term between financial inclusion and insurance penetration i.e. financial inclusion index values was multiplied with life insurance values for each of the 45 SSA countries considered.. |

References

- Anifowose, O. L.; Adeleke, O.; Mukorera, S. Determinants for BRICs Countries Military Expenditure. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica 2019, 15(4). [Google Scholar]

- Anusha, N. Insurance inclusion: A tool for financial inclusion in India. 2020. Retrieved from. Available online: https://mcom.sfgc.ac.in/downloads/2020/20.pdf.

- Center for Financial Inclusion. Inclusive Insurance: Closing the Protection Gap for Emerging Customers. 2024. Retrieved from. Available online: https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org.

- Chummun, B. Z. Mobile microinsurance and financial inclusion: the case of developing African countries. Africagrowth Agenda 2017, 2017(3), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chummun, B. Z. Mobile microinsurance and financial inclusion: the case of developing African countries. Africagrowth Agenda 2017, 2017(3), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, C.; Matul, M. Microinsurance: Targeting the poor; International Labour Organization, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D. Financial inclusion and the role of digital finance. World Bank Economic Review 2022, 36(2), 345–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gupte, R.; Venkataramani, B.; Gupta, D. Computation of financial inclusion index for India. 2012, 37, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, U.; Okonkwo, I. V. Microinsurance schemes and life insurance in Nigeria: An integrative review. The Journal of Risk Management and Insurance 2022, 26(1), 60–74. Available online: https://jrmi.au.edu/index.php/jrmi/article/view/243.

- Jain, M. K.; Singh, M. D. A review on enhancing insurance accessibility in India: The transformative role of financial inclusion. International Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development 2024, 3(1), 13–22. Available online: https://www.ijprems.com/uploadedfiles/paper/issue_3_march_2024/32813/final/fin_ijprems1709980781.pdf.

- Kajwang, B.

Influence of microinsurance access on poverty alleviation

. International Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development 2022, 3(1), 13–22. Available online: https://www.ajpojournals.org/journals/index.php/IJPID/article/view/1143.

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R. Barriers to financial inclusion in developing economies: A systematic review. International Journal of Financial Studies 2023, 11(1), 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, T. Impact of financial inclusion on poverty alleviation through cooperative banks. International Journal of Social Economics 2018, 45(5), 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, T. Impact of financial inclusion on poverty alleviation through cooperative banks. International Journal of Social Economics 2018, 45(5), 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbugua, D. K. Effect of microinsurance growth on life insurance in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, 2021. Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/160481.

-

Microinsurance Network The Landscape of Microinsurance 2023. 2023. Retrieved from. Available online: https://microinsurancenetwork.org/resources/the-landscape-of-microinsurance-2023.

- Morduch, J. The role of microinsurance in poverty alleviation: Evidence from low-income countries. Development Policy Review 2023, 41(3), 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Mose, S. Microinsurance as a strategy in enhancing life insurance in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, 2022. Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/162756.

- Foundation, Munich Re. The Landscape of Microinsurance 2021. 2021. Retrieved from. Available online: https://www.munichre-foundation.org.

- Sakanko, M. A. A state-level impact analysis of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in nigeria university of abuja, 2023.

- Sakanko, M. A. A STATE-LEVEL IMPACT ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION ON POVERTY REDUCTION IN NIGERIA. UNIVERSITY OF ABUJA, 2023.

- sBhatia, M.; Kaur, R. Challenges in microinsurance adoption: A study of low-income populations. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 2024, 29(1), 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, R. B. L. Assessment of Financial Inclusion: Indian Economic Growth and Micro Insurance. International Journal of Innovative Research in Engineering & Management 2022, 9(1), 504–509. Available online: https://acspublisher.com/journals/index.php/ijirem/article/view/11417.

- Tram, T. X. H.; Lai, T. D.; Nguyen, T. T. H. Constructing a composite financial inclusion index for developing economies. 2023, 87, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H. T. T.; Le, H. T. T. The impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction. Asian Journal of Law and Economics 2021, 12(1), 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H. T. T.; Le, H. T. T.; Nguyen, N. T.; Pham, T. T. M.; Hoang, H. T. The effect of financial inclusion on multidimensional poverty: the case of Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance 2022, 10(1), 2132643. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H. T. T.; Le, H. T. T.; Nguyen, N. T.; Pham, T. T. M.; Hoang, H. T. The effect of financial inclusion on multidimensional poverty: the case of Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance 2022, 10(1), 2132643. [Google Scholar]

- Turegano, D. M.; Herrero, A. G. Financial inclusion, rather than size, is the key to tackling income inequality. The Singapore Economic Review 2018, 63(01), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turegano, D. M.; Herrero, A. G. Financial inclusion, rather than size, is the key to tackling income inequality. The Singapore Economic Review 2018, 63(01), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VL, S. J.; Mohan, S. Insurance for financial inclusion and well-being. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2022, 6(3), 3989–3996. Available online: https://mail.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article.

- Wong, Z. Z. A.; Badeeb, R. A.; Philip, A. P. Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in ASEAN countries: does financial innovation matter? Social Indicators Research 2023, 169(1), 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z. Z. A.; Badeeb, R. A.; Philip, A. P. Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in ASEAN countries: does financial innovation matter? Social Indicators Research 2023, 169(1), 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Financial inclusion: A global perspective; World Bank Publications, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for the joint impacts of the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for the joint impacts of the joint impacts of financial inclusion and life insurance on poverty in Sub-Sahara Africa 1999Q1 to 2023Q4.

| |

POV |

FII |

INSUR |

FIINSUR |

INFL |

TO |

GRO |

| POV |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FII |

-0.096962 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| INSUR |

-0.219864 |

0.162425 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

| FIINSUR |

-0.090943 |

0.537680 |

0.290674 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

| INFL |

-0.019307 |

-0.000832 |

-0.040455 |

-0.015598 |

1.000000 |

|

|

| TO |

-0.187813 |

-0.057908 |

0.110489 |

0.099893 |

-0.138565 |

1.000000 |

|

| GRO |

-0.025682 |

0.106001 |

0.349707 |

0.143149 |

-0.067886 |

0.384479 |

1.000000 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).