Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

05 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nearest Neighbour

2.2. Radial Basis Function

2.3. Loss Function

- (1)

- it must be nonnegative;

- (2)

- if the inferred data match the modelled ones, the loss function vanishes;

- (3)

- the loss function increases as the discrepancy between inferred and known training data increases.

3. Results

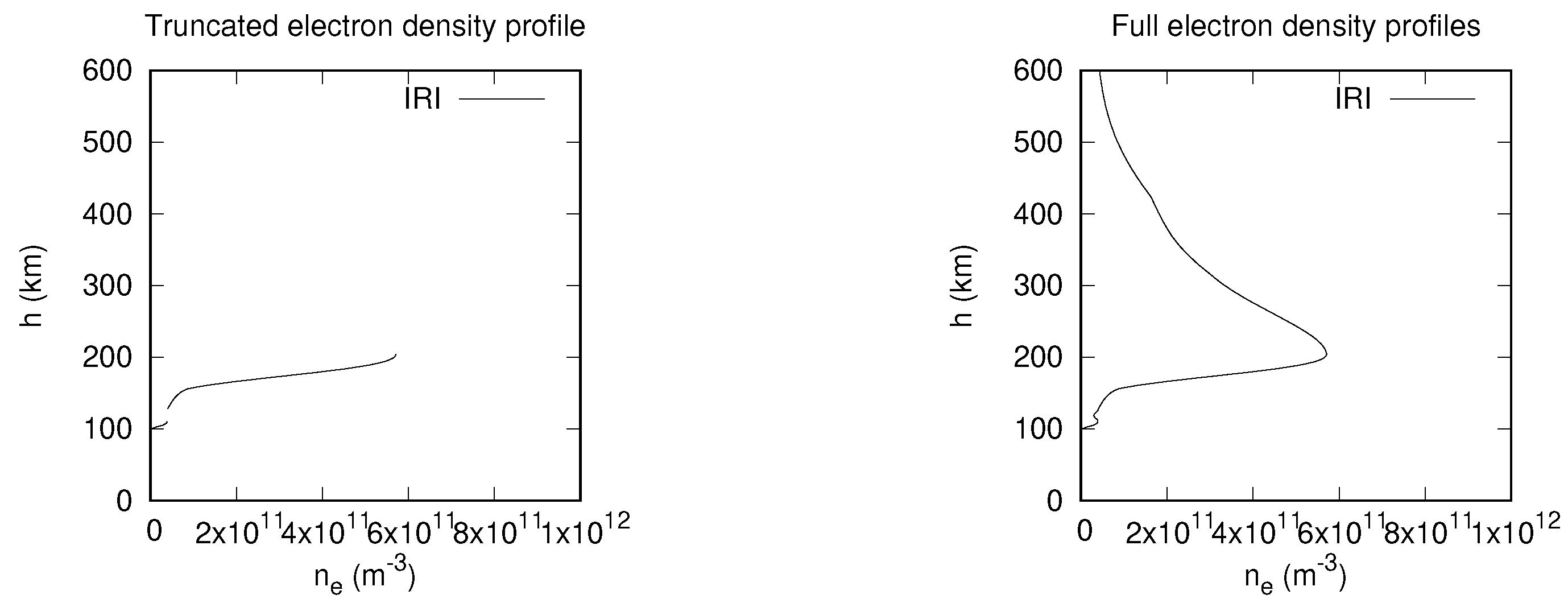

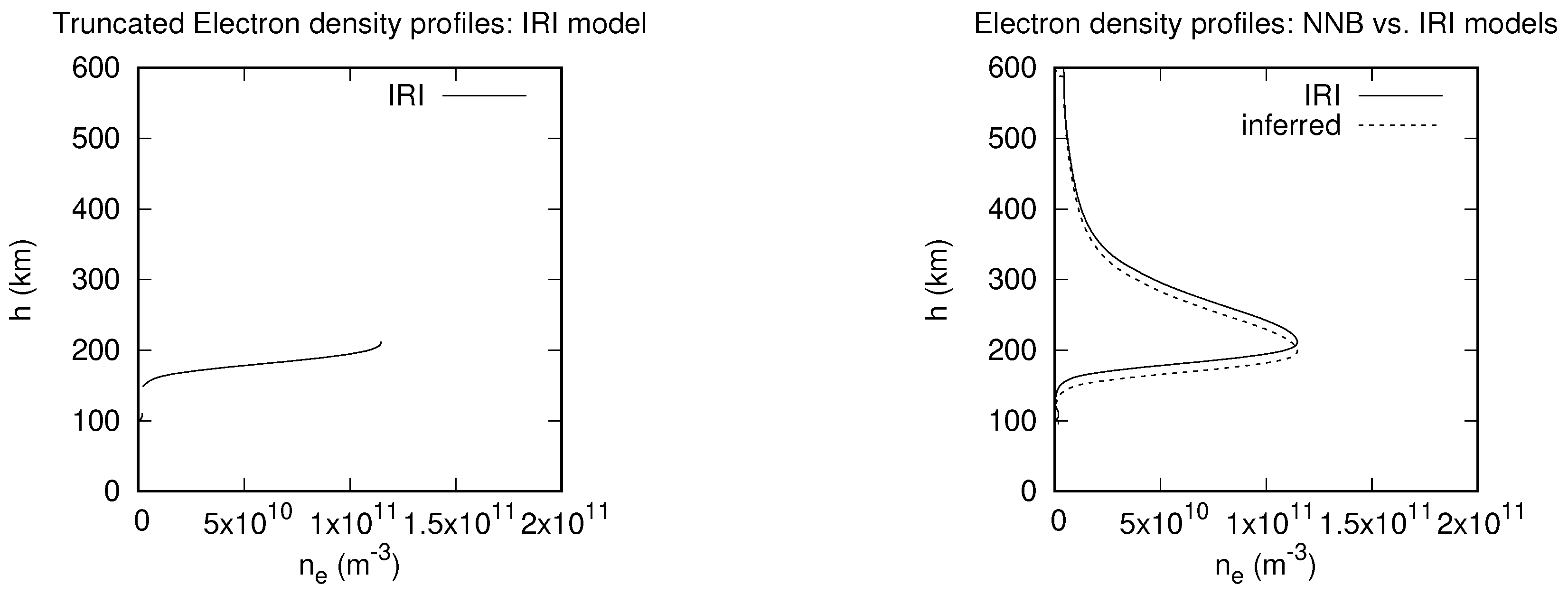

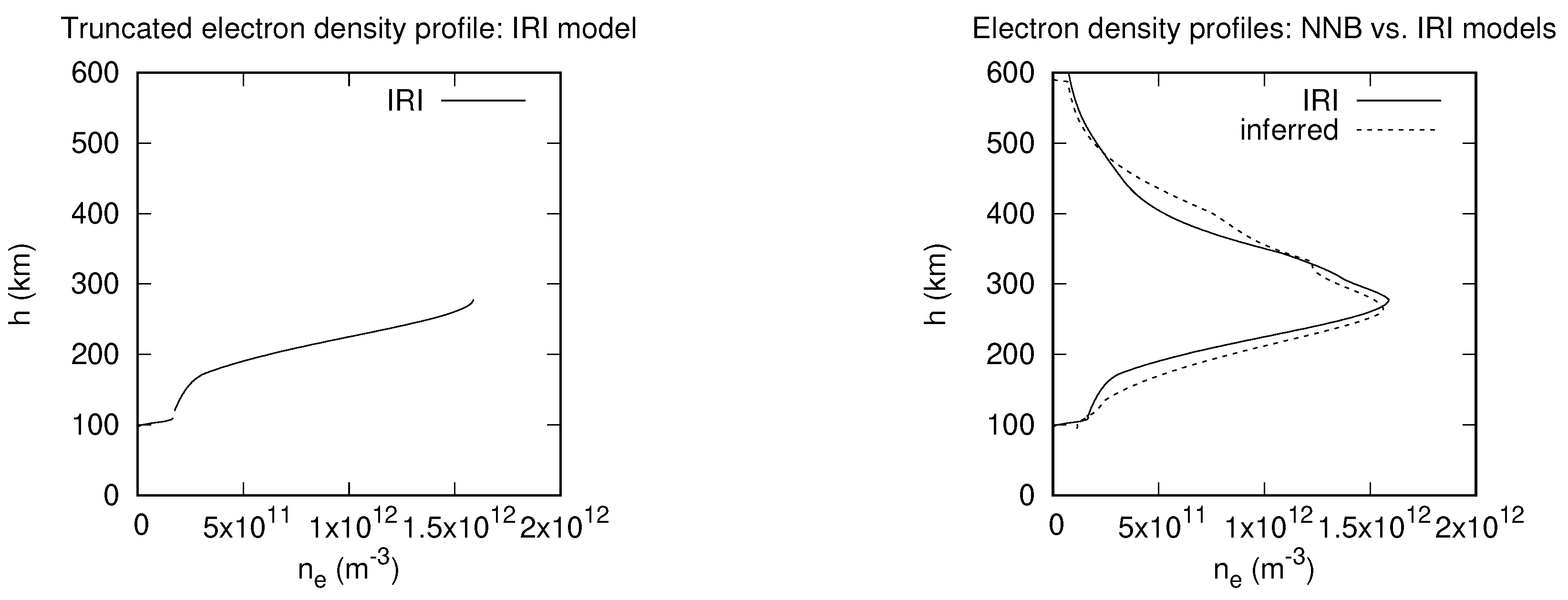

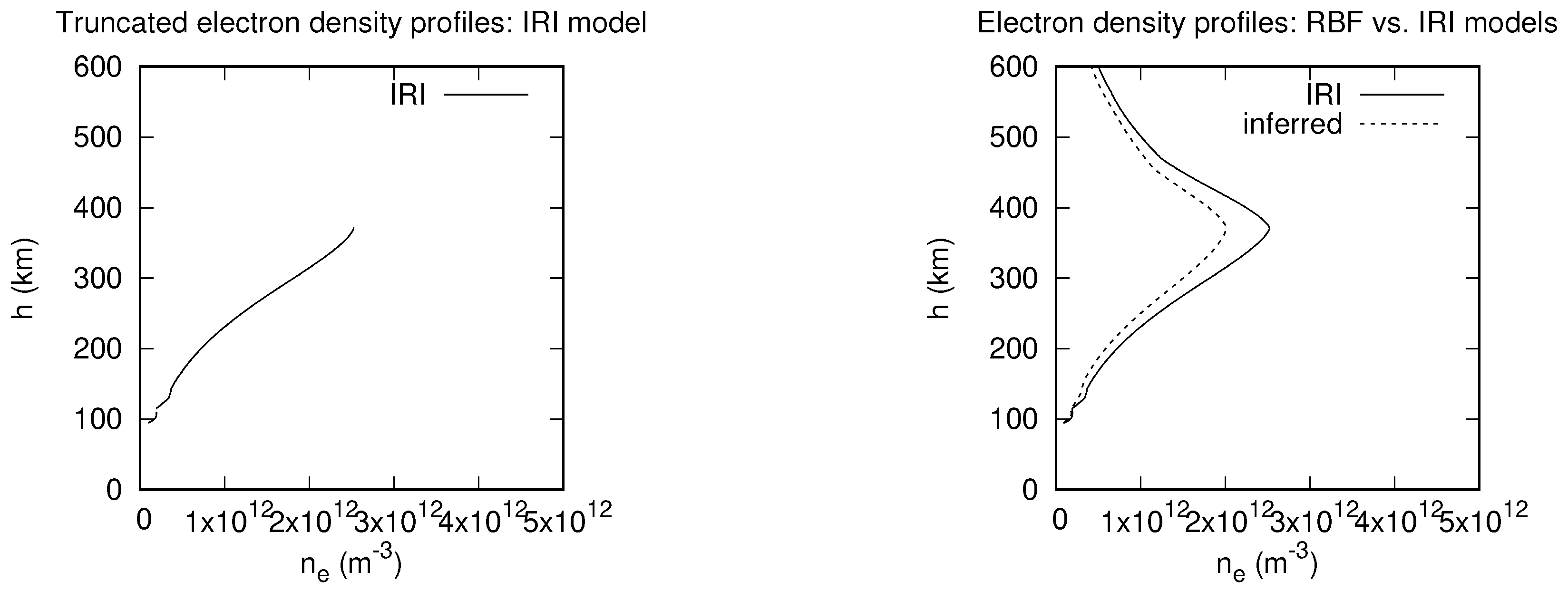

3.1. Inference of Electron Density Profiles with NNB and RBF Models

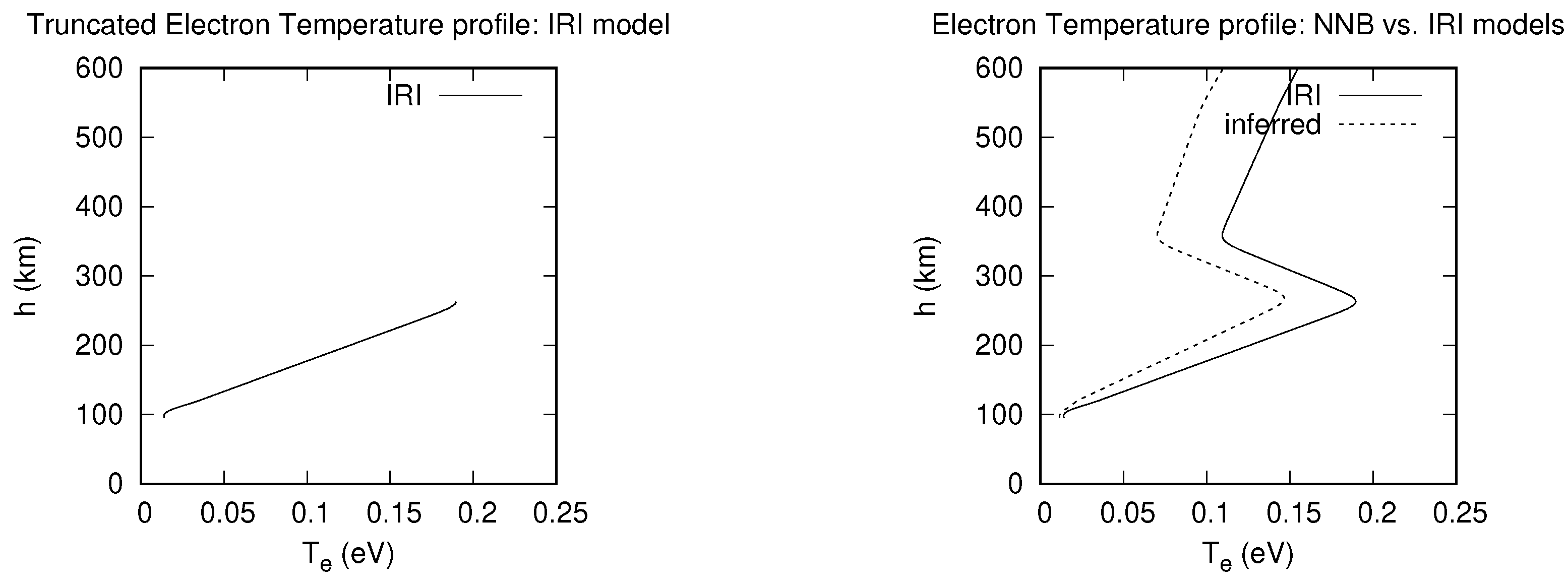

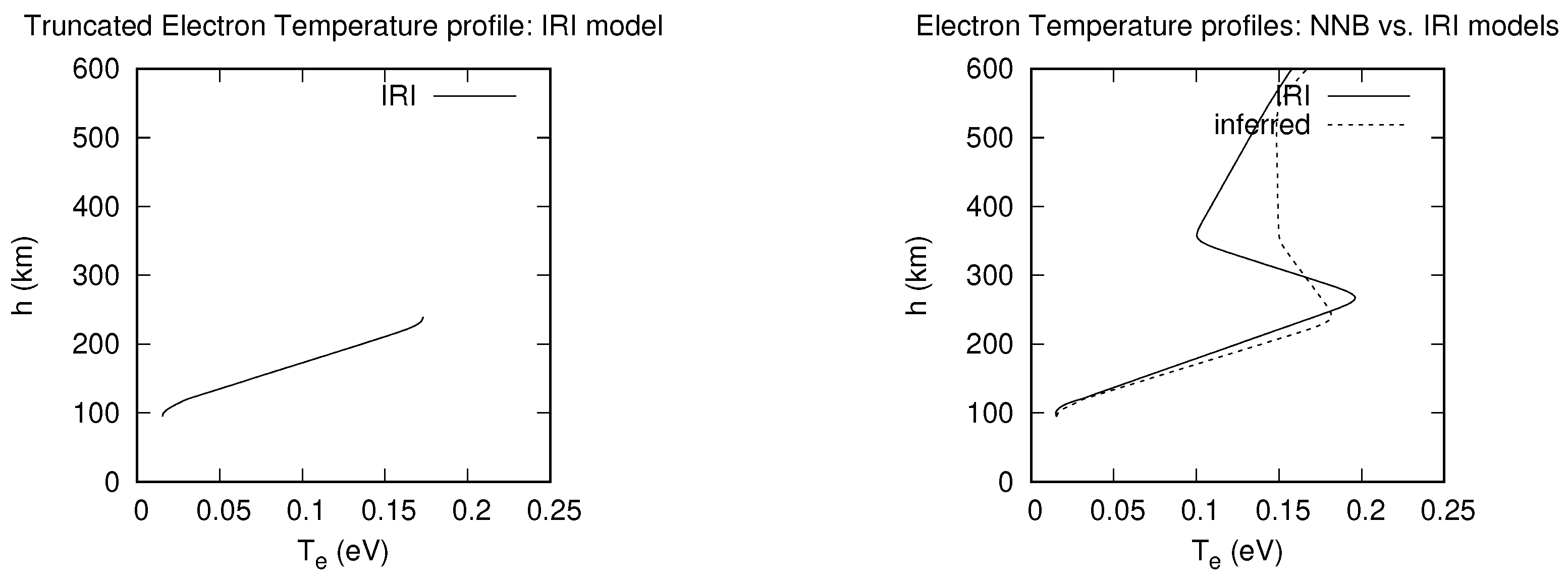

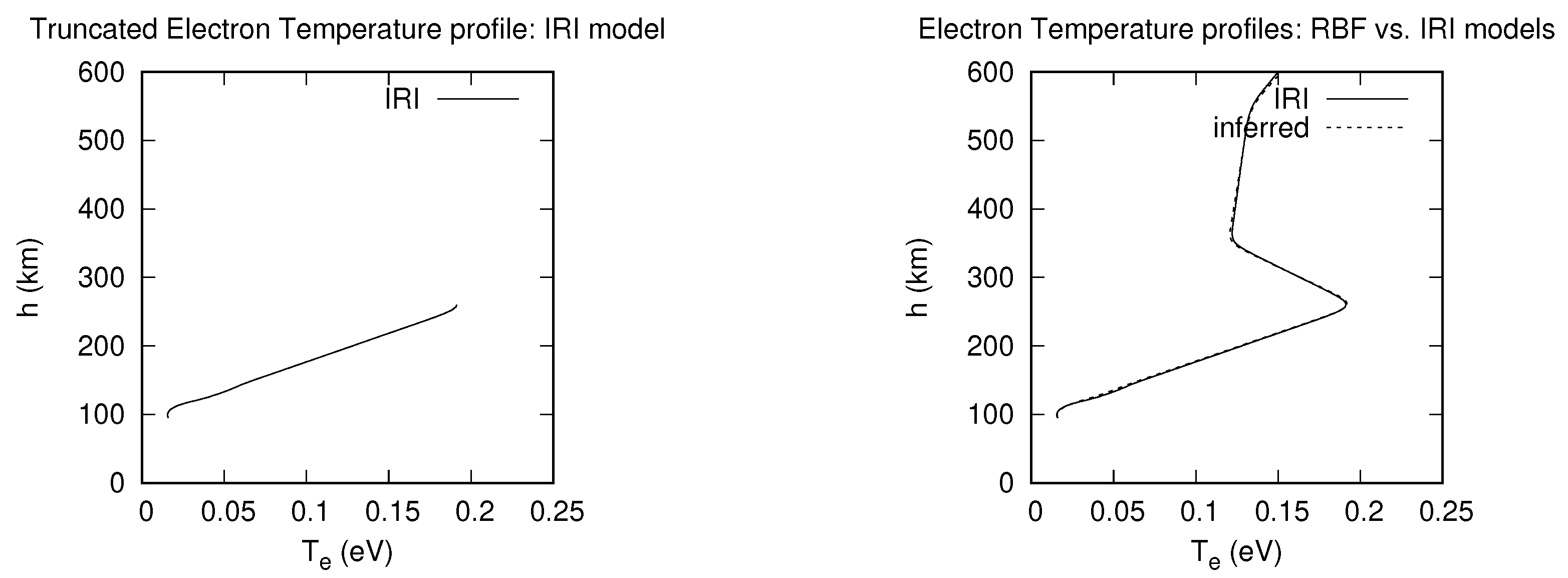

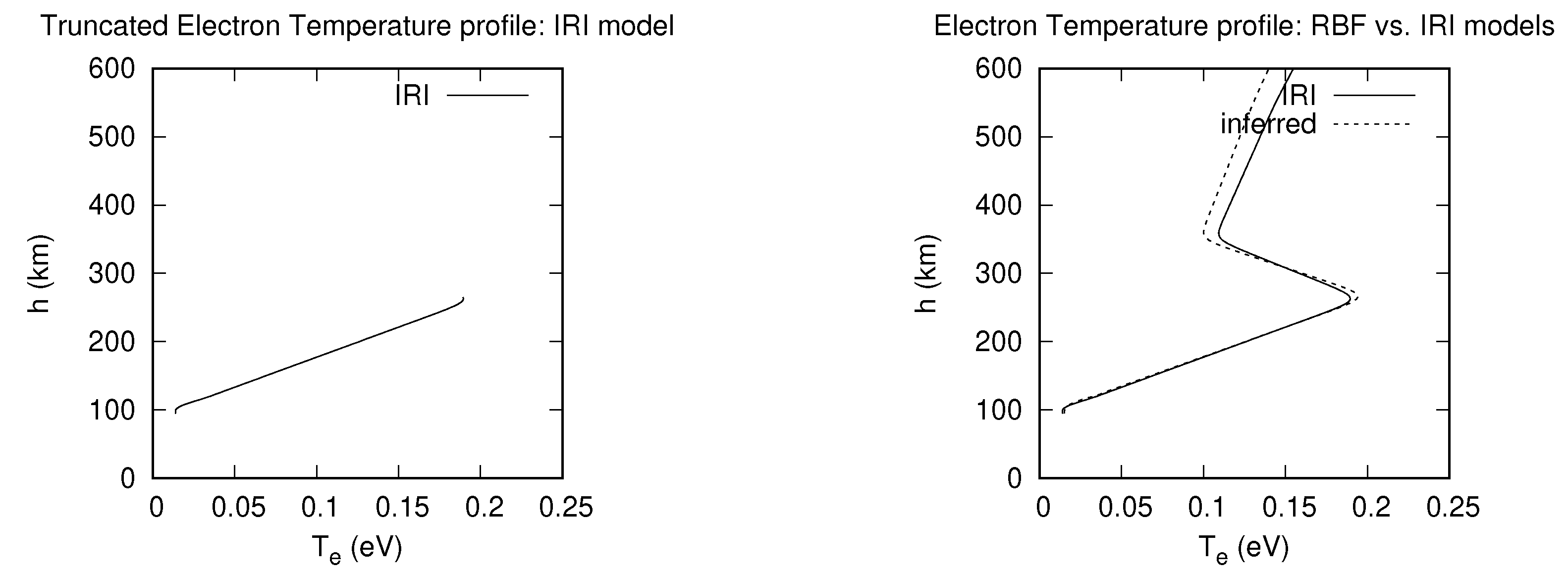

3.2. Inference of electron temperature profiles with NNB and RBF models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NNB | Nearest Neighbor |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| IRI | International Reference Ionosphere |

| E-CHAIM | Empirical Canadian High Arctic Ionospheric Model |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| AfriTEC | Africa Total Electron Content |

| ISR | Incoherent Scattering Radars |

| OSSEs | Observation System Simulation Experiments |

| TEC | Total Electron Content |

| COSMIC | Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere and Climate |

| RIOMETER | Relative Ionospheric Opacity Meter for Extra-Terrestrial Emissions of Radio noise |

| RO | Radio Occultation |

| RIOMETER | Relative Ionospheric Opacity Meter for Extra-Terrestrial Emissions of Radio noise |

| hmE | Height at Maximum E layer |

| hmF2 | Height at Maximum F2 layer |

| NmE | Maximum electron density in E layer |

| NmF2 | Maximum electron density in F2 layer |

| GOES | Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites |

References

- Appleton, E. V. Geophysical influences on the transmission of wireless waves. Proceedings of the Physical Society of London 1924, 37, 16D–22D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, G. Radio telegraphy. Journal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers 1922, 41, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, G.; Tuve M., A. A test of the existence of the conducting layer. Phys. Rev. 1926, 28, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bai, B. A novel low-power multifunctional ionospheric sounding system. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2011, 61, 1252–12591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Liu, L.; Wan, W.; Zhang, S. Variations of electron density based on long-term incoherent scatter radar and ionosonde measurements over millstone hill. in Radio Science 2015, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N.; Friis-Christensen, E.; Floberghagen, R.; Alken, P.; Beggan, C.D.; Chulliat, A.; Doornbos, E.; Da Encarnação, J.T.; Hamilton, B.; Hulot, G.; van den IJssel, J. The Swarm Satellite Constellation Application and Research Facility (SCARF) and Swarm data products. Earth Planet 2013, 65, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, R.; Exner, M.; Feng, D.; Gorbunov, M.; Hardy, K.; Herman, B.; Kuo, Y.; Meehan, T.; Melbourne, W.; Rocken, C.; Schreiner, W. Gps sounding of the atmosphere from low earth orbit: Preliminary results. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 1996, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthes, R. A. Exploring earth’s atmosphere with radio occultation: Contributions to weather, climate and space weather. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 2011, 4, 1077–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.N.; Kintner, P.M.; Kelley, M.C. Inference of equatorial field-line-integrated electron density values using whistlers. Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics, 1985, 47, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Forsythe, V.; Blay, R.; Azeem, I.; Crowley, G.; Wilson, W.J.; Dao, E.; Colman, J.; Parris, R. On constructing a realistic truth model using ionosonde data for observation system simulation experiments. Radio Science, 2022, 57, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yue, X.; Astafyeva, E.; Le, H.; Ren, Z.; Pedatella, N.M.; Ding, F.; Wei, Y. Global gridded ionospheric electron density derivation during 2006–2016 by assimilating cosmic tec and its validation. Journal of Geo- physical Research: Space Physics, 2022, 127, e2022JA030955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni G., D.; Radicella, S. M. An analytical model of the electron density profile in the ionosphere. Advances in Space Research, 1990, 10, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, D.; Vierinen, J. ; Kero,A.; Partamies,N. On the determination of ionospheric electron density profiles using multi-frequency riometry, 2022, Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst., 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, P.; McKinnell, L. Topside ionospheric vertical electron density profile reconstruction using gps and ionosonde data: Possibilities for south africa. in Annales Geophysicae, 2011, 9, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarulema, J.B.; Okoh, D.; Burešová, D.; Rabiu, B.; Tshisaphungo, M.; Kosch, M.; Häggström, I.; Erickson, P.J.; Milla, M.A. A global 3-d electron density reconstruction model based on radio occultation data and neural networks. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 2022, 221, 105–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarulema, J.B.; Okoh, D.; Burešová, D.; Rabiu, B.; Scipión, D.; Häggström, I.; Erickson, P.J.; Milla, M.A. A storm-time global electron density reconstruction model in three-dimensions based on artificial neural networks. Advances in Space Research, 2019, 124, 4639–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilitza, D.; Truhlik, V.; Yoshihara, O.; Moldwin, M. B. Development and Improvement of the International Reference Ionosphere with special emphasis on the topside and extension to the plasmasphere. Annals of Geophysics, 204, 67, SA443. [CrossRef]

- Nibigira, J.D. D; Ratnam, D. V.; Sivavaraprasad, G. Performance analysis of IRI-2016 model TEC predictions over Northern and Southern Hemispheric IGS stations during descending phase of solar cycle 24. Acta Geophys., 2021, 69, 1509–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, P. T.; Langley, R. B.; MacDougall, J. W.; Mushini, S. C.; Pokhotelov, D.; Hamza, A. M. Canadian high arctic ionospheric network (chain). Radio Science, 2009, 44, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibigira, J. D. D.; Ratnam, D.; Sivakrishna, K. Performance analysis of Nequick-G, IRI-2016, IRI-Plas 2017 and AfriTEC models over the African region during the geomagnetic storm of March 2015. Geomagn. Aeron., 2023, 63, S83––S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, B.; Koustov, A.V.; Themens, D.R.; Gillies, R.G. Ionospheric electron density over Resolute Bay according to E-CHAIM model and RISR radar measurements. Advances in Space Research, 2023, 71, 2759–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; An, B.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, R.; Wang, J.; Deng, X. Ionospheric Electron Density Model by Electron Density Grid Deep Neural Network (EDG-DNN). Atmosphere, 2023, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharenkova, I; Cherniak I; Gleason, S; Hunt, D; Freesland, D; Krimchansky, A.; McCorkel, J.; Ramsey, G.; Chapel, J. Statistical validation of ionospheric electron density profiles retrievals from GOES geosynchronous satellites. J. Space Weather Space Clim., 2023, 13, 23. [CrossRef]

- Köhnlein, W. (1986). A model of the electron and ion temperatures in the ionosphere. Planetary and Space Science, 1986, 34, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, M.; Galand, M.; Moore, L.; Mendillo, M.; Withers, P. Numerical simulations of ion and electron temperatures in the ionosphere of Mars: Multiple ions and diurnal variations. Icarus, 2014, 227, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignalberi, A.; Giannattasio, F.; Truhlik, V.; Coco, I.; Pezzopane, M; and Alberti, T. Investigating the main features of the correlation between electron density and temperature in the topside ionosphere through swarm satellites data. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys., 2024, 129, e2023JA032201. [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Wang, W.; Burns, A. G.; Yue, X.; Zhu, F. The correlation between electron temperature and density in the topside ionosphere during 2006–2009. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 2015, 120, 724–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S. W.; Hickey,G. L.; Head, S. J. Statistical primer: Multivariable regression considerations and pitfalls. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, 2019, 55, 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A. L. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 1959, 3, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C. Neural networks and deep learning. Cham: springer, 2018, 978, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallika, I. L.; Ratnam, D. V.; Ostuka, Y.; Sivavaraprasad, G.; Raman, S. Implementation of hybrid ionospheric tec forecasting algorithm using pca-nn method. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2018, 12, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, A.; Biersteker, J. B.; Dewey, R. M.,;Doran, G.; Forsberg, E. J.; Harris, C. D. K.; Kerner, H. R.; Skinner, K. A.; Smith, A. W.; Amini, R.; Cambioni, S.; Poian, V. D.; Garton, T. M.; Himes, M. D.; Millholland, S.; Ruhunusiri, S. Integrating Machine Learning for Planetary Science: Perspectives for the Next Decade. Bulletin of the AAS, 2021, 53. [CrossRef]

- Han,Y. ; Wang, L.; Fu, W.; Zhou, H.;Li, T.; Chen, R. Machine learning- based short-term gps tec forecasting during high solar activity and magnetic storm periods. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2022, 15, 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Azari, A.R.; Lockhart, J.W.; Liemohn, M.W.; Jia, X. Incorporating physical knowledge into machine learning for planetary space physics. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN COMPUT. SCI., 2021, 2, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Neskovic, P.; Cooper, L. N. An adaptive nearest neighbor algorithm for classification. In 2005 international conference on machine learning and cybernetics, 2005, 5, 3069–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Akoglu, L.; Rinaldo, A. Statistical analysis of nearest neighbor methods for anomaly detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Monte-Moreno, E.; Yang, H.; Hern´andez-Pajares, M. Forecast of the global tec by nearest neighbour technique. Remote Sensing, 2022, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.; Hinneburg, A.; Keim, D. On the surprising behavior of distance metrics in high dimensional space. In: Van den Bussche, J., Vianu, V. (eds) Database Theory — ICDT 2001. ICDT 2001. Lecture Notes in Com- puter Science 2001, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. science, 2019, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, R. , Shahsavani, S.; Sanchez-Arriaga, G. Beyond analytic ap- proximations with machine learning inference of plasma parameters and confidence intervals. Journal of Plasma Physics, 2023, 89, 905890111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. and Yuan, H. Ionospheric single-station tec short-term forecast using rbf neural network. Radio Science, 2014 49, 283–292. [CrossRef]

- Olowookere, A.; Marchand, R. A new technique to infer plasma density, flow velocity, and satellite potential from ion currents collected by a segmented langmuir probe. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 2022, 50, 3774–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Marholm, S.; Eklund, A.; Clausen, L.; Marchand, R. M-nlp infer- ence models using simulation and regression techniques. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 2023, 128, e2022JA030835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, H. Improving regional ionospheric tec mapping based on rbf interpolation. Advances in Space Research, 2021, 7, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Marchand, R. Inference of m-NLP data using radial basis function regression with center-evolving algorithm. Computer Physics Communication, 2022, 280, 108497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilitza, D.; Brace, L. H.; and Theis, R. F. Modelling of ionospheric temperature profiles. Advances in Space Research, 2019, 5, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model-inference | MARE | h (km) |

|---|---|---|

| NNB-Best | 0.20 | 145 |

| RBF-Best | 0.25 | 360 |

| NNB-Worst | 0.60 | 415 |

| RBF-Worst | 0.83 | 420 |

| Model-inference | MARE | h (km) |

|---|---|---|

| NNB-Best | 0.27 | 255 |

| RBF-Best | 0.01 | 360 |

| NNB-Worst | 0.50 | 350 |

| RBF-Worst | 0.12 | 420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).