Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

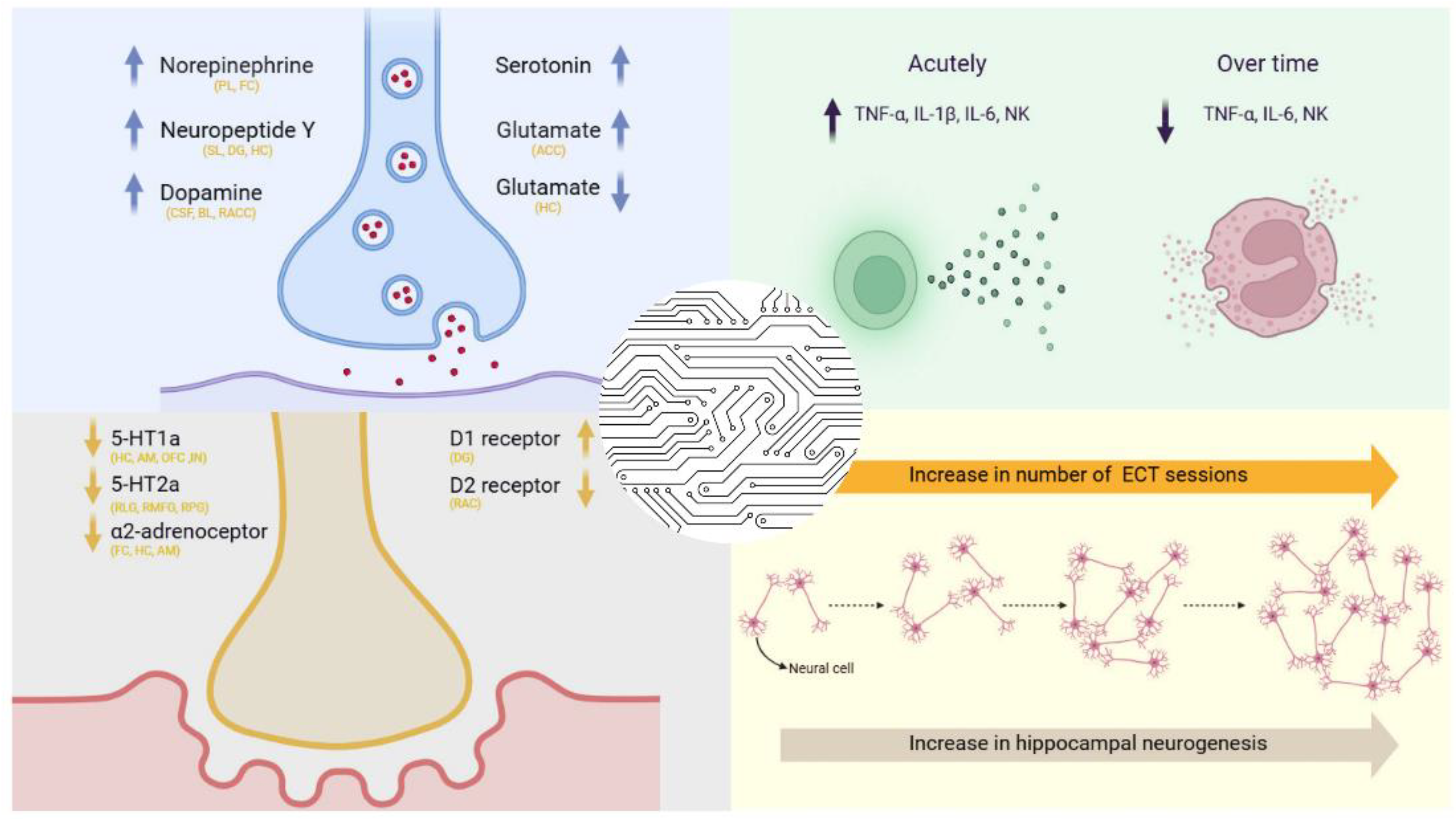

2. Understanding the Mechanisms of ECT: Key Theories

3. Neurotransmitter Modulation by ECT

4. The Role of Neuroplasticity, Functional Network Reorganization, and Neuroanatomical Changes in the Therapeutic Effects of ECT

4. Molecular Pathways Related to ECT

4.1. Neurotrophins and ECT

4.2. ECT and Immunological Alterations

4.3. Mitochondrial Function and Energy Metabolism During ECT

4.4. Oxidative Stress and ECT

4.5. Apoptosis and ECT

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marx, W.; Penninx, B.W.; Solmi, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Firth, J.; Carvalho, A.F.; Berk, M. Major depressive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023., 9(1), p.44.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Data Resources [Internet]. Seattle, WA: IHME; 2019.

- Collaborators; G.B.D.; 2019. Mental Disorders, et al.(2022) Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), pp.137-150.

- Mathers, C. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2008.; pp. 7-49.

- Abe, Y.; Erchinger, V.J.; Ousdal, O.T.; Oltedal, L.; Tanaka, K.F.; Takamiya, A. Neurobiological mechanisms of electroconvulsive therapy for depression: Insights into hippocampal volumetric increases from clinical and preclinical studies. J. Neurochem. 2024., 168(9), pp.1738-1750. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, R.T.; Kellner, C.H. Electroconvulsive therapy. NEJM. 2022., 386(7), pp.667-672.

- Spaans, H.P.; Sienaert, P.; Bouckaert, F.; van den Berg, J.F.; Verwijk, E.; Kho, K.H.; Stek, M.L.; Kok, R.M. Speed of remission in elderly patients with depression: electroconvulsive therapy v. medication. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015., 206(1), pp.67-71.

- Kellner, C.H.; Fink, M.; Knapp, R.; Petrides, G.; Husain, M.; Rummans, T.; Mueller, M.; Bernstein, H.; Rasmussen, K.; O’Connor, K.;Smith, G. Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: a consortium for research in ECT study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005., 162(5), pp.977-982. [CrossRef]

- Trifu, S.; Sevcenco, A.; Stănescu, M.; Drăgoi, A.M.; Cristea, M.B. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy as a potential first-choice treatment in treatment-resistant depression. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021., 22(5), p.1281.

- UK Ect Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2003., 361(9360), pp.799-808. [CrossRef]

- Kritzer, M.D.; Peterchev, A.V.; Camprodon, J.A. Electroconvulsive therapy: mechanisms of action, clinical considerations, and future directions. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2023., 31(3), pp.101-113. [CrossRef]

- McClintock, S.M.; Brandon, A.R.; Husain, M.M.; Jarrett, R.B. A systematic review of the combined use of electroconvulsive therapy and psychotherapy for depression.J. ECT. 2011., 27(3), pp.236-243. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Zhao, L.B.; Liu, Y.Y.; Fan, S.H.; and Xie, P. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of electroconvulsive therapy versus repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a systematic review and multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 2017., 320, pp.30-36. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mulsant, B.H.; Liu, A.Y.; Blumberger, D.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Rajji, T.K. Systematic review of cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in late-life depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016., 24(7), pp.547-565. [CrossRef]

- Karabatsiakis, A.; Schönfeldt-Lecuona, C. Depression, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and electroconvulsive therapy: a new approach towards personalized medicine in psychiatric treatment-a short review and current perspective. Transl. Psychiatry 2020., 10(1), p.226.

- Kellner, C.H.; Husain, M.M.; Knapp, R.G.; McCall, W.V.; Petrides, G.; Rudorfer, M.V.; Young, R.C.; Sampson, S.; McClintock, S.M.; Mueller, M.; Prudic, J. Right unilateral ultrabrief pulse ECT in geriatric depression: phase 1 of the PRIDE study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016., 173(11), pp.1101-1109. [CrossRef]

- McCall, W.V.; Lisanby, S.H.; Rosenquist, P.B.; Dooley, M.; Husain, M.M.; Knapp, R.G.; Petrides, G.; Rudorfer, M.V.; Young, R.C.; McClintock, S.M.; Mueller, M.; Effects of continuation electroconvulsive therapy on quality of life in elderly depressed patients: A randomized clinical trial. J. Psychiatr. Res 2018., 97, pp.65-69. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.S.; Chung, C.H.; Tsai, C.K.; Chien, W.C. In-hospital mortality among electroconvulsive therapy recipients: a 17-year nationwide population-based retrospective study. Eur. psychiatr. 2017., 42, pp.29-35. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.S.; Chung, C.H.; Ho, P.S.; Tsai, C.K.; Chien, W.C. Superior anti-suicidal effects of electroconvulsive therapy in unipolar disorder and bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2018., 20(6), pp.539-546. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.M.; McLoughlin, D.M. From Molecules to Mind: Mechanisms of Action of Electroconvulsive Therapy. FOCUS, Am. J. Psychiatry 2019., 17(1), pp.73-75. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Psychological theories of ECT: a review. Br. J. Psychiatry 1967., 113(496), pp.301-311.

- Cameron, D.E. Production of differential amnesia as a factor in the treatment of schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 1960., 1(1), pp.26-34.

- Netto, C.A.; Izquierdo, I. Amnesia as a major side effect of electroconvulsive shock: the possible involvement of hypothalamic opioid systems. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1984., 17(3-4), pp.349-351.

- Bassa, A.; Sagués, T.; Porta-Casteràs, D.; Serra, P.; Martínez-Amorós, E.; Palao, D.J.; Cano, M.; Cardoner, N. The neurobiological basis of cognitive side effects of electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2021., 11(10), p.1273. [CrossRef]

- Sackeim, H.A.; Prudic, J.; Devanand, D.P.; Kiersky, J.E.; Fitzsimons, L.; Moody, B.J.; McElhiney, M.C.; Coleman, E.A.; Settembrino, J.M. Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993., 328(12), pp.839-846. [CrossRef]

- Sienaert, P.; Vansteelandt, K.; Demyttenaere, K.; Peuskens, J. Randomized comparison of ultra-brief bifrontal and unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: cognitive side-effects. J. Affect. Disord. 2010., 122(1-2), pp.60-67. [CrossRef]

- Farzan, F.; Boutros, N.N.; Blumberger, D.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J. What does the electroencephalogram tell us about the mechanisms of action of ECT in major depressive disorders?. J. ECT. 2014., 30(2), pp.98-106. [CrossRef]

- Duthie, A.C.; Perrin, J.S.; Bennett, D.M.; Currie, J.; Reid, I.C. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of electroconvulsive therapy and relation to therapeutic efficacy. J ECT. 2015, 31(3), pp.173-178. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, M.K.; Near, J.; Blicher, A.B.; Videbech, P.; Blicher, J.U. Magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopic measurement of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in major depression before and after electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2019, 31(1), pp.17-26. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.D.; Robins, P.L.; Regenold, W.; Rohde, P.; Dannhauer, M.; Lisanby, S.H. How electroconvulsive therapy works in the treatment of depression: is it the seizure, the electricity, or both?. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024., 49(1), pp.150-162. [CrossRef]

- Altar, C.A.; Laeng, P.; Jurata, L.W.; Brockman, J.A.; Lemire, A.; Bullard, J.; Bukhman, Y.V.; Young, T.A.; Charles, V.; Palfreyman, M.G. Electroconvulsive seizures regulate gene expression of distinct neurotrophic signaling pathways. J. Neurosci. 2004., 24(11), pp.2667-2677. [CrossRef]

- Newton, S.S.; Collier, E.F.; Hunsberger, J.; Adams, D.; Terwilliger, R.; Selvanayagam, E.; Duman, R.S. Gene profile of electroconvulsive seizures: induction of neurotrophic and angiogenic factors. J. Neurosci. 2003., 23(34), pp.10841-10851. [CrossRef]

- Perera, T.D.; Coplan, J.D.; Lisanby, S.H.; Lipira, C.M.; Arif, M.; Carpio, C.; Spitzer, G.; Santarelli, L.; Scharf, B.; Hen, R.; Rosoklija, G. Antidepressant-induced neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult nonhuman primates. J. Neurosci. 2007., 27(18), pp.4894-4901. [CrossRef]

- Haskett, R.F. Electroconvulsive therapy’s mechanism of action: neuroendocrine hypotheses. J. ECT.2014., 30(2), pp.107-110.

- Eşel, E.; Baştürk, M.; Kula, M.; Reyhancan, M.; Turan, M.T.; Sofuoğlu, S. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy on pituitary hormones in depressed patients. Klin. Psikofarmakol. B. 2003., 13, pp.109-117.

- Burgese, D.F.; Bassitt, D.P. Variation of plasma cortisol levels in patients with depression after treatment with bilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2015., 37(1), pp.27-36. [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, F.; Sienaert, P.; Obbels, J.; Dols, A.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Stek, M.; Bolwig, T. ECT: its brain enabling effects: a review of electroconvulsive therapy–induced structural brain plasticity. J. ECT. 2014., 30(2), pp.143-151.

- Madsen, T.M.; Treschow, A.; Bengzon, J.; Bolwig, T.G.; Lindvall, O.; Tingström, A. Increased neurogenesis in a model of electroconvulsive therapy. Biol. Psychiatry 2000., 47(12), pp.1043-1049. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, O.; Gohar, S.M.; Ibrahim, W.; El-Makawi, S.M.; Fakher, W.; Taher, D.B.; Abdel Samie, M.; Khalil, M.A.; Saleh, A.A. Brain-Derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plasma level increases in patients with resistant schizophrenia treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Int J Psychiat Clin. 2022., 26(4), pp.370-375. [CrossRef]

- Kato, N. Neurophysiological mechanisms of electroconvulsive therapy for depression. Neurosci. Res. 2009., 64(1), pp.3-11. [CrossRef]

- Baldinger, P.; Lotan, A.; Frey, R.; Kasper, S.; Lerer, B.; Lanzenberger, R. Neurotransmitters and electroconvulsive therapy. J. ECT. 2014., 30(2), pp.116-121.

- Yatham, L.N.; Liddle, P.F.; Lam, R.W.; Zis, A.P.; Stoessl, A.J.; Sossi, V.; Adam, M.J.; Ruth, T.J. Effect of electroconvulsive therapy on brain 5-HT2 receptors in major depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010., 196(6), pp.474-479. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.M.; Vasile, A.I.; Trifu, S.C. Neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic impact of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Rom. J. Morphol. Embryology 2024., 65(1), p.13. [CrossRef]

- Landau, A.M.; Phan, J.A.; Iversen, P.; Lillethorup, T.P.; Simonsen, M.; Wegener, G.; Jakobsen, S.; Doudet, D.J. Decreased in vivo α2 adrenoceptor binding in the Flinders Sensitive Line rat model of depression. Neuropharmacol. 2015., 91, pp.97-102. [CrossRef]

- Lillethorup, T.P.; Iversen, P.; Wegener, G.; Doudet, D.J.M.; Landau, A.M. α2-adrenoceptor binding in Flinders-sensitive line compared with Flinders-resistant line and Sprague-Dawley rats. Acta Neuropsyciatr. 2015., 27(6), pp.345-352. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Imoto, Y.; Yamamoto, F.; Kawasaki, M.; Ueno, M.; Segi-Nishida, E.;Suzuki, H. Rapid and lasting enhancement of dopaminergic modulation at the hippocampal mossy fiber synapse by electroconvulsive treatment. J. Neurophysiol. 2017., 117(1), pp.284-289. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, R.; Deng, N.; Tang, L.; Zhao, B. Anesthetic Influence on Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024., pp.1491-1502. [CrossRef]

- Markianos, M.; Hatzimanolis, J.; Lykouras, L. Relationship between prolactin responses to ECT and dopaminergic and serotonergic responsivity in depressed patients.Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002., 252, pp.166-171. [CrossRef]

- Burnet, P.W.; Sharp, T.; LeCorre, S.M.; Harrison, P.J. Expression of 5-HT receptors and the 5-HT transporter in rat brain after electroconvulsive shock. Neurosci. Lett. 1999., 277(2), pp.79-82. [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.; Gur, E.; Shapira, B.; Lerer, B. Neurochemical mechanisms of action of ECS: evidence from in vivo studies. J. ECT. 1998., 14(3), pp.153-171.

- Burnet, P.W.J.; Mead, A.; Eastwood, S.L.; Lacey, K.; Harrison, P.J.; Sharp, T. Repeated ECS differentially affects rat brain 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor expression. Neuroreport 1995., 6(6), pp.901-904. [CrossRef]

- Chaput, Y.; de Montigny, C.; Blier, P. Presynaptic and postsynaptic modifications of the serotonin system by long-term administration of antidepressant treatments. An in vivo electrophysiologic study in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1991., 5(4), pp.219-229.

- Strome, E.M.; Clark, C.M.; Zis, A.P.; Doudet, D.J. Electroconvulsive shock decreases binding to 5-HT2 receptors in nonhuman primates: an in vivo positron emission tomography study with [18F] setoperone. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005., 57(9), pp.1004-1010. [CrossRef]

- Lanzenberger, R.; Baldinger, P.; Hahn, A.; Ungersboeck, J.; Mitterhauser, M.; Winkler, D.; Micskei, Z.; Stein, P.; Karanikas, G.; Wadsak, W.; Kasper, S. Global decrease of serotonin-1A receptor binding after electroconvulsive therapy in major depression measured by PET. Mol. Psychiatry 2013., 18(1), pp.93-100. [CrossRef]

- Saijo, T.; Takano, A.; Suhara, T.; Arakawa, R.; Okumura, M.; Ichimiya, T.; Ito, H.; Okubo, Y. Effect of electroconvulsive therapy on 5-HT1A receptor binding in patients with depression: a PET study with [11C] WAY 100635. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010., 13(6), pp.785-791. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT2A receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain Res. Bull. 2001., 56(5), pp.441-451. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.H.; Kapur, S.; Eisfeld, B.; Brown, G.M.; Houle, S.; DaSilva, J.; Wilson, A.A.; Rafi-Tari, S.; Mayberg, H.S.; Kennedy, S.H. The effect of paroxetine on 5-HT2A receptors in depression: an [18F] setoperone PET imaging study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001., 158(1), pp.78-85.

- Nikisch, G.; Mathé, A.A. CSF monoamine metabolites and neuropeptides in depressed patients before and after electroconvulsive therapy. Eur. psychiatr. 2008., 23(5), pp.356-359. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Yoshimura, R.; Ikenouchi-Sugita, A.; Hori, H.; Umene-Nakano, W.; Inoue, Y.; Ueda, N.; Nakamura, J. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy is associated with changing blood levels of homovanillic acid and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in refractory depressed patients: a pilot study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008., 32(5), pp.1185-1190. [CrossRef]

- Saijo, T.; Takano, A.; Suhara, T.; Arakawa, R.; Okumura, M.; Ichimiya, T.; Ito, H.; Okubo, Y. Electroconvulsive therapy decreases dopamine D2 receptor binding in the anterior cingulate in patients with depression: a controlled study using positron emission tomography with radioligand [11C] FLB 457. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010., 71(6), p.793.

- Landau, A.M.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Clark, C.M.; Zis, A.P.; Doudet, D.J. Electroconvulsive therapy alters dopamine signaling in the striatum of non-human primates. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011., 36(2), pp.511-518. [CrossRef]

- Lammers, C.H.; Diaz, J.; Schwartz, J.C.; Sokoloff, P. Selective increase of dopamine D3 receptor gene expression as a common effect of chronic antidepressant treatments. Mol. Psychiatry 2000., 5(4), pp.378-388. [CrossRef]

- Huuhka, K.; Anttila, S.; Huuhka, M.; Hietala, J.; Huhtala, H.; Mononen, N.; Lehtimäki, T.;Leinonen, E. Dopamine 2 receptor C957T and catechol-o-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphisms are associated with treatment response in electroconvulsive therapy. Neurosci. Lett. 2008., 448(1), pp.79-83. [CrossRef]

- Kask, A.; Harro, J.; von Hörsten, S.; Redrobe, J.P.; Dumont, Y.; Quirion, R. The neurocircuitry and receptor subtypes mediating anxiolytic-like effects of neuropeptide Y. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2002., 26(3), pp.259-283. [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, S.; Eker, O.O.; Abdulrezzak, U. The effects of antidepressants on neuropeptide Y in patients with depression and anxiety. Pharmacopsychiatry 2016., 49(01), pp.26-31. [CrossRef]

- Lillethorup, T.P.; Iversen, P.; Fontain, J.; Wegener, G.; Doudet, D.J.; Landau, A.M. Electroconvulsive shocks decrease α2-adrenoceptor binding in the Flinders rat model of depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015., 25(3), pp.404-412. [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Manevitz, A.Z.; Chen, J.S.; Johnson, K.S.; Adelsheimer, E.F.; Azima-Heller, R.; Massina, A.; Wilner, P.J. Acute effects of single and repeated electroconvulsive therapy on plasma catecholamines and blood pressure in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1990., 34(2), pp.127-137. [CrossRef]

- Ambade, V.; Arora, M.M.; Singh, P.; Somani, B.L.; Basannar, D. Adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine level estimation in depression: does it help?. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2009., 65(3), pp.216-220. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.B.; Cooper, S.J. Plasma noradrenaline response to electroconvulsive therapy in depressive illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997., 171(2), pp.182-186. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, C.; Maier, H.B.; Moschny, N.; Jahn, K.; Bleich, S.; Frieling, H.; Neyazi, A. Epinephrine levels decrease in responders after electroconvulsive therapy. J. Neural. Transm. 2021., 128, pp.1917-1921. [CrossRef]

- El Mansari, M.; Guiard, B.P.; Chernoloz, O.; Ghanbari, R.; Katz, N.; Blier, P. Relevance of norepinephrine–dopamine interactions in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2010., 16(3), pp.e1-e17. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Min, S.; Wei, K.; Li, P.; Cao, J.; Li, Y. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy and propofol on spatial memory and glutamatergic system in hippocampus of depressed rats.J. ECT. 2010., 26(2), pp.126-130. [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, A.; Mahlstedt, M.M.; Vollmayr, B.; Henn, F.A.; Ende, G.; Elevated spectroscopic glutamate/γ-amino butyric acid in rats bred for learned helplessness. Neuroreport 2007., 18(14), pp.1469-1473. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Sawa, A.; Iyo, M.; Increased levels of glutamate in brains from patients with mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007., 62(11), pp.1310-1316. [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; van der Veen, J.W.; Tumonis, T.; Meyers, N.; Shen, J.; Drevets, W.C. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and γ-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007., 64(2), pp.193-200. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Narr, K.L.; Woods, R.P.; Phillips, O.R.; Alger, J.R.; Espinoza, R.T. Glutamate normalization with ECT treatment response in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2013., 18(3), pp.268-270. [CrossRef]

- Njau, S.; Joshi, S.H.; Espinoza, R.; Leaver, A.M.; Vasavada, M.; Marquina, A.; Woods, R.P.; Narr, K.L. Neurochemical correlates of rapid treatment response to electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depression. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017., 42(1), pp.6-16. [CrossRef]

- Pfleiderer, B.; Michael, N.; Erfurth, A.; Ohrmann, P.; Hohmann, U.; Wolgast, M.; Fiebich, M.; Arolt, V.; Heindel, W. Effective electroconvulsive therapy reverses glutamate/glutamine deficit in the left anterior cingulum of unipolar depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2003., 122(3), pp.185-192. [CrossRef]

- Erchinger, V.J.; Craven, A.R.; Ersland, L.; Oedegaard, K.J.; Bartz-Johannessen, C.A.; Hammar, Å.; Haavik, J.; Riemer, F.; Kessler, U.; Oltedal, L. Electroconvulsive therapy triggers a reversible decrease in brain N-acetylaspartate. Front. Psychiatry 2023., 14, p.1155689. [CrossRef]

- Puderbaugh, M.; Emmady, P.D. Neuroplasticity. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, Florida, 2023., pp 3-9.

- Joshi, S.H.; Espinoza, R.T.; Pirnia, T.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Ayers, B.; Leaver, A.; Woods, R.P.; Narr, K.L. 2016. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry.2016., 79(4), pp.282-292. [CrossRef]

- Nordanskog, P.; Dahlstrand, U.; Larsson, M.R.; Larsson, E.M.; Knutsson, L.; Johanson, A. Increase in hippocampal volume after electroconvulsive therapy in patients with depression: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. J. ECT. 2010., 26(1), pp.62-67.

- Jorgensen, A.; Magnusson, P.; Hanson, L.G.; Kirkegaard, T.; Benveniste, H.; Lee, H.; Svarer, C.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Fink-Jensen, A.; Knudsen, G.M.; Paulson, O.B. Regional brain volumes, diffusivity, and metabolite changes after electroconvulsive therapy for severe depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2016., 133(2), pp.154-164. [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, F.; Dols, A.; Emsell, L.; De Winter, F.L.; Vansteelandt, K.; Claes, L.; Sunaert, S.; Stek, M.; Sienaert, P.; Vandenbulcke, M. Relationship between hippocampal volume, serum BDNF, and depression severity following electroconvulsive therapy in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016., 41(11), pp.2741-2748. [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, A.; Demirakca, T.; Böhringer, A.; von Hohenberg, C.C.; Aksay, S.S.; Bumb, J.M.; Kranaster, L.; Nickl-Jockschat, T.; Grözinger, M.; Thomann, P.A.; Wolf, R.C.; Electroconvulsive therapy induced gray matter increase is not necessarily correlated with clinical data in depressed patients. Brain Stimul. 2019., 12(2), pp.335-343. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, J.A.; Hoffstaedter, F.; Zavorotny, M.; Zöllner, R.; Wolf, R.C.; Thomann, P.; Redlich, R.; Opel, N.; Dannlowski, U.; Groezinger, M.; Demirakca, T. Electroconvulsive therapy modulates grey matter increase in a hub of an affect processing network. Neuroimage Clin. 2020., 25, p.102114. [CrossRef]

- van Oostrom, I.; van Eijndhoven, P.; Butterbrod, E.; van Beek, M.H.; Janzing, J.; Donders, R.; Schene, A.; Tendolkar, I. Decreased cognitive functioning after electroconvulsive therapy is related to increased hippocampal volume: exploring the role of brain plasticity. J. ECT.2018., 34(2), pp.117-123.

- Ousdal, O.T.; Brancati, G.E.; Kessler, U.; Erchinger, V.; Dale, A.M.; Abbott, C.; Oltedal, L. The neurobiological effects of electroconvulsive therapy studied through magnetic resonance: what have we learned, and where do we go?.Biol. Psychiatry 2022., 91(6), pp.540-549. [CrossRef]

- Pirnia, T.; Joshi, S.H.; Leaver, A.M.; Vasavada, M.; Njau, S.; Woods, R.P.; Espinoza, R.; Narr, K.L. Electroconvulsive therapy and structural neuroplasticity in neocortical, limbic and paralimbic cortex. Transl. Psychiatry 2016., 6(6), pp.e832-e832. [CrossRef]

- Lyden, H.; Espinoza, R.T.; Pirnia, T.; Clark, K.; Joshi, S.H.; Leaver, A.M.; Woods, R.P.; Narr, K.L. Electroconvulsive therapy mediates neuroplasticity of white matter microstructure in major depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2014., 4(4), pp.e380-e380. [CrossRef]

- Malberg, J.E.; Eisch, A.J.; Nestler, E.J.; Duman, R.S. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000., 20(24), pp.9104-9110. [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.W.; Wojtowicz, J.M.; Burnham, W.M. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the rat following electroconvulsive shock seizures. Exp. Neurol. 2000., 165(2), pp.231-236. [CrossRef]

- Sorri, A.; Järventausta, K.; Kampman, O.; Lehtimäki, K.; Björkqvist, M.; Tuohimaa, K.; Hämäläinen, M.; Moilanen, E.; Leinonen, E. Effect of electroconvulsive therapy on brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with major depressive disorder.Brain Behav. 2018., 8(11), p.e01101. [CrossRef]

- Kyeremanteng, C.; MacKay, J.C.; James, J.S.; Kent, P.; Cayer, C.; Anisman, H.; Merali, Z. Effects of electroconvulsive seizures on depression-related behavior, memory and neurochemical changes in Wistar and Wistar–Kyoto rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014., 54, pp.170-178. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Min, S.; Wei, K.; Cao, J.; Wang, B.; Li, P.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y. Behavioral and molecular responses to electroconvulsive shock differ between genetic and environmental rat models of depression. Psychiatry Res. 2015., 226(2-3), pp.451-460. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi-Yamaguchi, Y.; Furuichi, T. The Homer family proteins. Genome Biol. 2007., 8, pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.H.; Park, J.M.; Park, S.; Xiao, B.; Dehoff, M.H.; Kim, S.; Hayashi, T.; Schwarz, M.K.; Huganir, R.L.; Seeburg, P.H.; Linden, D.J. Homeostatic scaling requires group I mGluR activation mediated by Homer1a. Neuron 2010., 68(6), pp.1128-1142. [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.K.; Orlowski, D.; Bjarkam, C.R.; Wegener, G.; Elfving, B. Potential roles for Homer1 and Spinophilin in the preventive effect of electroconvulsive seizures on stress-induced CA3c dendritic retraction in the hippocampus. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.2015., 25(8), pp.1324-1331. [CrossRef]

- Serchov, T.; Clement, H.W.; Schwarz, M.K.; Iasevoli, F.; Tosh, D.K.; Idzko, M.; Jacobson, K.A.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Normann, C.; Biber, K.; van Calker, D. Increased signaling via adenosine A1 receptors, sleep deprivation, imipramine, and ketamine inhibit depressive-like behavior via induction of Homer1a. Neuron 2015., 87(3), pp.549-562. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.V.; Hartmann, J.; Labermaier, C.; Häusl, A.S.; Zhao, G.; Harbich, D.; Schmid, B.; Wang, X.D.; Santarelli, S.; Kohl, C.; Gassen, N.C. Homer1/mGluR5 activity moderates vulnerability to chronic social stress. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015., 40(5), pp.1222-1233. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yao, X.; Sun, L.; Zhao, L.; Xu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, F.; Zou, X.; Cheng, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, W. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy on depression and its potential mechanism. Front Psychol. 2020., 11, p.80. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, S.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Lu, F.; Pang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; Chu, C.; Tian, Y. Enhanced default mode network functional connectivity links with electroconvulsive therapy response in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2022., 306, pp.47-54. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, C.C.; Lemke, N.T.; Gopal, S.; Thoma, R.J.; Bustillo, J.; Calhoun, V.D.; Turner, J.A. Electroconvulsive therapy response in major depressive disorder: a pilot functional network connectivity resting state FMRI investigation. Front. Psychiatry. 2013., 4, p.10. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.D.; Robins, P.L.; Regenold, W.; Rohde, P.; Dannhauer, M.; Lisanby, S.H. How electroconvulsive therapy works in the treatment of depression: is it the seizure, the electricity, or both?. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024., 49(1), pp.150-162. [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.J.; Boulle, F.; Steinbusch, H.W.; van den Hove, D.L.; Kenis, G.; Lanfumey, L. Neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity pathways in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Psychopharmacol. 2018., 235, pp.2195-2220. [CrossRef]

- Pardossi, S.; Fagiolini, A.; Cuomo, A. Variations in BDNF and Their Role in the Neurotrophic Antidepressant Mechanisms of Ketamine and Esketamine: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024., 25(23), p.13098. [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Seki, T.; Liu, J.; Nakamura, K.; Namba, T.; Matsubara, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Arai, H. Effects of repeated electroconvulsive seizure on cell proliferation in the rat hippocampus. Synapse 2010., 64(11), pp.814-821. [CrossRef]

- Ricken, R.; Adli, M.; Lange, C.; Krusche, E.; Stamm, T.J.; Gaus, S.; Koehler, S.; Nase, S.; Bschor, T.; Richter, C.; Steinacher, B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum concentrations in acute depressive patients increase during lithium augmentation of antidepressants. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013., 33(6), pp.806-809. [CrossRef]

- Mikoteit, T.; Beck, J.; Eckert, A.; Hemmeter, U.; Brand, S.; Bischof, R.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Delini-Stula, A. High baseline BDNF serum levels and early psychopathological improvement are predictive of treatment outcome in major depression. Psychopharmacology 2014., 231, pp.2955-2965. [CrossRef]

- Nase, S.; Köhler, S.; Jennebach, J.; Eckert, A.; Schweinfurth, N.; Gallinat, J.; Lang, U.E.; Kühn, S. Role of serum brain derived neurotrophic factor and central n-acetylaspartate for clinical response under antidepressive pharmacotherapy. Neurosignals 2018., 24(1), pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Mitoma, M.; Sugita, A.; Hori, H.; Okamoto, T.; Umene, W.; Ueda, N.; Nakamura, J. Effects of paroxetine or milnacipran on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in depressed patients. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007., 31(5), pp.1034-1037. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Kishi, T.; Hori, H.; Katsuki, A.; Sugita-Ikenouchi, A.; Umene-Nakano, W.; Atake, K.; Iwata, N.; Nakamura, J. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor at 4 weeks and response to treatment with SSRIs. Psychiatry Investig. 2014., 11(1), p.84. [CrossRef]

- Tadić, A.; Wagner, S.; Schlicht, K.F.; Peetz, D.; Borysenko, L.; Dreimüller, N.; Hiemke, C.; Lieb, K. The early non-increase of serum BDNF predicts failure of antidepressant treatment in patients with major depression: a pilot study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011., 35(2), pp.415-420. [CrossRef]

- Dreimüller, N.; Schlicht, K.F.; Wagner, S.; Peetz, D.; Borysenko, L.; Hiemke, C.; Lieb, K.; Tadić, A. Early reactions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in plasma (pBDNF) and outcome to acute antidepressant treatment in patients with Major Depression. Neuropharmacol. 2012., 62(1), pp.264-269. [CrossRef]

- Karege, F.; Perret, G.; Bondolfi, G.; Schwald, M.; Bertschy, G.; Aubry, J.M. Decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in major depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 2002., 109(2), pp.143-148. [CrossRef]

- Haile, C.N.; Murrough, J.W.; Iosifescu, D.V.; Chang, L.C.; Al Jurdi, R.K.; Foulkes, A.; Iqbal, S.; Mahoney III, J.J.; De La Garza, R.; Charney, D.S.; Newton, T.F. Plasma brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and response to ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014., 17(2), pp.331-336.

- Piccinni, A.; Del Debbio, A.; Medda, P.; Bianchi, C.; Roncaglia, I.; Veltri, A.; Zanello, S.; Massimetti, E.; Origlia, N.; Domenici, L.; Marazziti, D. Plasma Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in treatment-resistant depressed patients receiving electroconvulsive therapy. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009., 19(5), pp.349-355. [CrossRef]

- Maffioletti, E.; Gennarelli, M.; Gainelli, G.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L.; Bortolomasi, M.; Minelli, A. BDNF genotype and baseline serum levels in relation to electroconvulsive therapy effectiveness in treatment-resistant depressed patients. J. ECT. 2019., 35(3), pp.189-194. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.M.; Dunne, R.; McLoughlin, D.M. BDNF plasma levels and genotype in depression and the response to electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul. 2018., 11(5), pp.1123-1131. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Gama, C.S.; Massuda, R.; Torres, M.; Camargo, D.; Kunz, M.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P.S.; Kapczinski, F.; de Almeida Fleck, M.P.; Lobato, M.I. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is not associated with response to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a pilot study in drug resistant depressed patients. Neurosci. Lett. 2009., 453(3), pp.195-198. [CrossRef]

- van Zutphen, E.M.; Rhebergen, D.; van Exel, E.; Oudega, M.L.; Bouckaert, F.; Sienaert, P.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Stek, M.; Dols, A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a possible predictor of electroconvulsive therapy outcome. Transl. Psychiatry 2019., 9(1), p.155. [CrossRef]

- Vanicek, T.; Kranz, G.S.; Vyssoki, B.; Fugger, G.; Komorowski, A.; Höflich, A.; Saumer, G.; Milovic, S.; Lanzenberger, R.; Eckert, A.; Kasper, S. Acute and subsequent continuation electroconvulsive therapy elevates serum BDNF levels in patients with major depression. Brain Stimul. 2019., 12(4), pp.1041-1050. [CrossRef]

- Zelada, M.I.; Garrido, V.; Liberona, A.; Jones, N.; Zúñiga, K.; Silva, H.; Nieto, R.R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as a predictor of treatment response in major depressive disorder (MDD): a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023., 24(19), p.14810. [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Liu, Y.; Gui, S.; Tian, L.; Xu, S.; Song, X.; Zhong, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, L. Vascular endothelial growth factor in major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: A network meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020., 292, p.113319. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.N.; Soares, J.C.; Carvalho, A.F.; Quevedo, J. Role of trophic factors GDNF, IGF-1 and VEGF in major depressive disorder: A comprehensive review of human studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2016., 197, pp.9-20. [CrossRef]

- Minelli, A.; Zanardini, R.; Abate, M.; Bortolomasi, M.; Gennarelli, M.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) serum concentration during electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in treatment resistant depressed patients. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011., 35(5), pp.1322-1325. [CrossRef]

- Minelli, A.; Maffioletti, E.; Bortolomasi, M.; Conca, A.; Zanardini, R.; Rillosi, L.; Abate, M.; Giacopuzzi, M.; Maina, G.; Gennarelli, M.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L. Association between baseline serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels and response to electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014., 129(6), pp.461-466. [CrossRef]

- Grønli, O.; Stensland, G.Ø.; Wynn, R.; Olstad, R. Neurotrophic factors in serum following ECT: a pilot study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2009., 10(4), pp.295-301. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sha, W.; Xie, C.; Xi, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y. Electroconvulsive therapy increases glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) serum levels in patients with drug-resistant depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009., 170(2-3), pp.273-275. [CrossRef]

- Angelucci, F.; Aloe, L.; Jiménez-Vasquez, P.; Mathé, A.A. Electroconvulsive stimuli alter the regional concentrations of nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in adult rat brain. J. ECT. 2002., 18(3), pp.138-143. [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, S.; Shimizu, K.; Nibuya, M.; Suzuki, E.; Nagata, K.;Kondo, T. Activated brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB signaling in rat dorsal and ventral hippocampi following 10-day electroconvulsive seizure treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2017., 660, pp.45-50. [CrossRef]

- Schurgers, G.; Walter, S.; Pishva, E.; Guloksuz, S.; Peerbooms, O.; Incio, L.R.; Arts, B.M.; Kenis, G.; Rutten, B.P. Longitudinal alterations in mRNA expression of the BDNF neurotrophin signaling cascade in blood correlate with changes in depression scores in patients undergoing electroconvulsive therapy.Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022., 63, pp.60-70. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2009., 65(9), pp.732-741.

- Mössner, R.; Mikova, O.; Koutsilieri, E.; Saoud, M.; Ehlis, A.C.; Müller, N.; Fallgatter, A.J.; Riederer, P. Consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Biological Markers: biological markers in depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2007., 8(3), pp.141-174. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.N.; Macdougall, M.G.; Hu, F.; Pace, T.W.W.; Raison, C.L.; Miller, A.H. Endogenous glucocorticoids protect against TNF-alpha-induced increases in anxiety-like behavior in virally infected mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2007., 12(4), pp.408-417. [CrossRef]

- Simen, B.B.; Duman, C.H.; Simen, A.A.; Duman, R.S. TNFα signaling in depression and anxiety: behavioral consequences of individual receptor targeting. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006, 59(9), pp.775-785. [CrossRef]

- Tyring, S.; Gottlieb, A.; Papp, K.; Gordon, K.; Leonardi, C.; Wang, A.; Lalla, D.; Woolley, M.; Jahreis, A.; Zitnik, R.; Cella, D. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. The Lancet. 2006, 367(9504), pp.29-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zong, S.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.; The effects of microglia-associated neuroinflammation on Alzheimer’s disease. Front. immunol. 2023, 14, p.1117172. [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Reshef, R. Depression as a microglial disease. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38(10), pp.637-658.

- Goldfarb, S.; Fainstein, N.; Ganz, T.; Vershkov, D.; Lachish, M.; Ben-Hur, T. Electric neurostimulation regulates microglial activation via retinoic acid receptor α signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2021, 96, pp.40-53. [CrossRef]

- Lehtimäki, K.; Keränen, T.; Huuhka, M.; Palmio, J.; Hurme, M.; Leinonen, E.;Peltola, J. Increase in plasma proinflammatory cytokines after electroconvulsive therapy in patients with depressive disorder. J ECT. 2008, 24(1), pp.88-91. [CrossRef]

- Kronfol, Z.A.; Lemay, L.; Nair, M.P.; Kluger, M.J. Electroconvulsive Therapy Increases Plasma Levels of Interleukin-6 a. 1990. [CrossRef]

- Hestad, K.A.; Tønseth, S.; Støen, C.D.; Ueland, T.; Aukrust, P. Raised plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor α in patients with depression: normalization during electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2003, 19(4), pp.183-188.

- Järventausta, K.; Sorri, A.; Kampman, O.; Björkqvist, M.; Tuohimaa, K.; Hämäläinen, M.; Moilanen, E.; Leinonen, E.; Peltola, J.; Lehtimäki, K. Changes in interleukin-6 levels during electroconvulsive therapy may reflect the therapeutic response in major depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135(1), pp.87-92. [CrossRef]

- Kranaster, L.; Hoyer, C.; Aksay, S.S.; Bumb, J.M.; Müller, N.; Zill, P.; Schwarz, M.J.; Sartorius, A. Antidepressant efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy is associated with a reduction of the innate cellular immune activity in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018, 19(5), pp.379-389. [CrossRef]

- Fluitman, S.B.; Heijnen, C.J.; Denys, D.A.; Nolen, W.A.; Balk, F.J.; Westenberg, H.G. Electroconvulsive therapy has acute immunological and neuroendocrine effects in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131(1-3), pp.388-392. [CrossRef]

- Kronfol, Z.; Nair, M.P.; Weinberg, V.; Young, E.A.; Aziz, M. Acute effects of electroconvulsive therapy on lymphocyte natural killer cell activity in patients with major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 71(1-3), pp.211-215. [CrossRef]

- Moschny, N.; Jahn, K.; Maier, H.B.; Khan, A.Q.; Ballmaier, M.; Liepach, K.; Sack, M.; Skripuletz, T.; Bleich, S.; Frieling, H.; Neyazi, A.. Electroconvulsive therapy, changes in immune cell ratios, and their association with seizure quality and clinical outcome in depressed patients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 36, pp.18-28. [CrossRef]

- Donato, R. S100: a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33(7), pp.637-668. [CrossRef]

- Marenholz, I.; Heizmann, C.W.; Fritz, G. S100 proteins in mouse and man: from evolution to function and pathology (including an update of the nomenclature). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 322(4), pp.1111-1122. [CrossRef]

- F. Winningham-Major, J.L.; Staecker, S.W.; Barger, S. Coats,; L.J. Van Eldik. Neurite extension and neuronal survival activities of recombinant S100 beta proteins that differ in the content and position of cysteine residues, J. Cell Biol. 109. 1989, 3063–3071. [CrossRef]

- Arts, B.; Peters, M.; Ponds, R.; Honig, A.; Menheere, P.; van Os, J. S100 and impact of ECT on depression and cognition. J ECT. 2006, 22:206–212. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Baussan, Y.; Hebert-Chatelain, E. Connecting Dots between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Depression. Biomolecules. 2023, Apr 20;13(4):695. [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J. An update on mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Antioxidants. 2020, 9(6), p.472. [CrossRef]

- Andrés Juan, C.; Pérez de Lastra, J.M.; Plou Gasca, F.J; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 28;22(9):4642.

- Mattson, MP.; Gleichmann, M.; Cheng, A.; Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron. 2008, 10;60(5):748-66. [CrossRef]

- Petschner, P.; Gonda, X.; Baksa, D.; Eszlari, N.; Trivaks, M.; Juhasz, G.; Bagdy, G. Genes linking mitochondrial function, cognitive impairment and depression are associated with endophenotypes serving precision medicine. Neuroscience. 2018, 370, pp.207-217. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Sheng, H.; Mitochondria in depression: The dysfunction of mitochondrial energy metabolism and quality control systems. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2024, 30(2), p.e14576. [CrossRef]

- Gebara, E.; Zanoletti, O.; Ghosal, S.; Grosse, J.; Schneider, B.L.; Knott, G.; Astori, S.;Sandi, C. Mitofusin-2 in the nucleus accumbens regulates anxiety and depression-like behaviors through mitochondrial and neuronal actions. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021, 89(11), pp.1033-1044. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Huang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lu, J.; Sheng, H; Ni, X.; Treadmill exercise ameliorates depression-like behavior in the rats with prenatal dexamethasone exposure: the role of hippocampal mitochondria. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, p.264. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chai, Y.; Ding, J.H.; Sun, X.L; Hu, G. Chronic mild stress damages mitochondrial ultrastructure and function in mouse brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 488(1), pp.76-80. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Benatti, C.; Blom, J.M.; Caraci, F.; Tascedda, F. The many faces of mitochondrial dysfunction in depression: From pathology to treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, p.995. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Wan, S.; Guo, R. Association between mitochondrial DNA levels and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry. 2023, 23(1), p.866. [CrossRef]

- Fattal, O.; Link, J.; Quinn, K.; Cohen, B.H;Franco, K. Psychiatric comorbidity in 36 adults with mitochondrial cytopathies. CNS spectrums. 2007, 12(6), pp.429-438. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A.; Johansson, A.; Wibom, R.; Nennesmo, I.; von Döbeln, U.; Hagenfeldt, L.; Hällström, T. Alterations of mitochondrial function and correlations with personality traits in selected major depressive disorder patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 76(1-3), pp.55-68.

- Brymer, K.J.; Fenton, E.Y.; Kalynchuk, L.E.; Caruncho, H.J. Peripheral etanercept administration normalizes behavior, hippocampal neurogenesis, and hippocampal reelin and GABAA receptor expression in a preclinical model of depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, p.121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hodes, G.E.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, W.; Golden, S.A.; Bi, W.; Menard, C.; Kana, V.; Leboeuf, M.; Xie, M. Epigenetic modulation of inflammation and synaptic plasticity promotes resilience against stress in mice. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9(1), p.477. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, A.; Rollins, B.; Magnan, C.; van Oven, M.; Baldi, P.; Myers, R.M.; Barchas, J.D.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Watson, S.J.; Akil, H.; Bunney, W.E. Mitochondrial mutations in subjects with psychiatric disorders. PloS one. 2015, 10(5), p.e0127280. [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, T.; Kubota, M.; Miyauchi, T.; Ishiwata, M.; Kato, T. A marked effect of electroconvulsive stimulation on behavioral aberration of mice with neuron-specific mitochondrial DNA defects. PLoS One. 2008, 3(3), p.e1877. [CrossRef]

- Búrigo, M.; Roza, C.A.; Bassani, C.; Fagundes, D.A.; Rezin, G.T.; Feier, G.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Quevedo, J.; Streck, E.L. Effect of electroconvulsive shock on mitochondrial respiratory chain in rat brain. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 31, pp.1375-1379. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.;Abramov, A.Y. Mechanism of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, (1), p.428010.

- Yoshikawa, T.; You, F. Oxidative stress and bio-regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(6), p.3360.

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Oršolić, N.; Karlović, D.; Peitl, V. Flavonols in action: targeting oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in major depressive disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(8), p.6888. [CrossRef]

- Gadoth, N.; Göbel, HH. Oxidative Stress in Applied Basic Research and Clinical Practice. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2011; pp. 19–27.

- Bakunina, N.; Pariante, C.M.; Zunszain, P.A.. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression. Immunology. 2015, 144(3), pp.365-373. [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Galecki, P.; Chang, Y.S.; Berk, M. A review on the oxidative and nitrosative stress (O&NS) pathways in major depression and their possible contribution to the (neuro) degenerative processes in that illness. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011, 35(3), pp.676-692. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Nagappa, A.N.; Patil, C.R. Role of oxidative stress in depression. Drug Discov. Today. 2020, 25(7), pp.1270-1276.

- Ait Tayeb, A.E.K.; Poinsignon, V.; Chappell, K.; Bouligand, J.; Becquemont, L.;Verstuyft, C. Major depressive disorder and oxidative stress: a review of peripheral and genetic biomarkers according to clinical characteristics and disease stages. Antioxidants. 2023, 12(4), p.942. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, S.; Gurpegui, M.; Garrote-Rojas, D.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Carretero, M.D.; Correll, C.U. Oxidative stress parameters and antioxidants in adults with unipolar or bipolar depression versus healthy controls: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 314, pp.211-221. [CrossRef]

- Atagün, M.İ.; Canbek, Ö.A. A systematic review of the literature regarding the relationship between oxidative stress and electroconvulsive therapy. Alpha Psychiatry. 2022, 23(2), p.47. [CrossRef]

- Bader, M.; Abdelwanis, M.; Maalouf, M.; Jelinek, H.F. Detecting depression severity using weighted random forest and oxidative stress biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), p.16328. [CrossRef]

- Barichello, T.; Bonatto, F.; Feier, G.; Martins, M.R.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Izquierdo, I.; Quevedo, J. No evidence for oxidative damage in the hippocampus after acute and chronic electroshock in rats. Brain Res. 2004, 1014(1-2), pp.177-183. [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Ş.; Aybastı, Ö.; Elboğa, G.; Altındağ, A.; Tamam, L. Major depresyonda elektrokonvulsif terapinin oksidatif metabolizma üzerine etkisi. Çukurova med. j. 2017, 42(3), pp.513-517.

- Lv, Q.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Huang, X.; Zhu, M.; Geng, R.; Cheng, X.; Bao, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; He, Y. Disturbance of oxidative stress parameters in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder and their association with electroconvulsive therapy response. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020, 23(4), pp.207-216. [CrossRef]

- Karayağmurlu, E.; Elboğa, G.; Şahin, Ş.K.; Karayağmurlu, A.; Taysı, S.; Ulusal, H.;Altındağ, A. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy on nitrosative stress and oxidative DNA damage parameters in patients with a depressive episode. Int. J. Psychiatry. 2022, 26(3), pp.259-268. [CrossRef]

- Barichello, T.; Bonatto, F.; Agostinho, F.R.; Reinke, A.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Izquierdo, I.; Quevedo, J. Structure-related oxidative damage in rat brain after acute and chronic electroshock. Neurochem. Res. 2004, 29, pp.1749-1753. [CrossRef]

- Župan, G.; Pilipović, K.; Hrelja, A.; Peternel, S. Oxidative stress parameters in different rat brain structures after electroconvulsive shock-induced seizures. Prog.Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008, 32(3), pp.771-777. [CrossRef]

- Eraković, V.; Župan, G.; Varljen, J.; Radošević, S.; Simonić, A. Electroconvulsive shock in rats: changes in superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activity. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2000, 76(2), pp.266-274. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.; Cejvanovic, V.; Wörtwein, G.; Hansen, A.R.; Marstal, K.K.; Weimann, A.; Bjerring, P.N.; Dela, F.; Poulsen, H.E.; Jørgensen, M.B. Increased oxidation of RNA despite reduced mitochondrial respiration after chronic electroconvulsive stimulation of rat brain tissue. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 690, pp.1-5. [CrossRef]

- Hollville, E.; Romero, S.E.; Deshmukh, M. Apoptotic cell death regulation in neurons. FEBS Lett. 2019, 286(17), pp.3276-3298. [CrossRef]

- Erekat, N.S. Apoptosis and its therapeutic implications in neurodegenerative diseases. Clin. Anat. 2022, 35(1), pp.65-78. [CrossRef]

- Lucassen, P.J.; Heine, V.M.; Muller, M.B.; van der Beek, E.M.; Wiegant, V.M.; Ron De Kloet, E.; Joels, M.; Fuchs, E.; Swaab, D.F.; Czeh, B. Stress, depression and hippocampal apoptosis. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006, 5(5), pp.531-546.

- Kondratyev, A.; Sahibzada, N.; Gale, K. Electroconvulsive shock exposure prevents neuronal apoptosis after kainic acid-evoked status epilepticus. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001, 91(1-2), pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Zarubenko, I.I.; Yakovlev, A.A.; Stepanichev, M.Y.; Gulyaeva, N.V. Electroconvulsive shock induces neuron death in the mouse hippocampus: correlation of neurodegeneration with convulsive activity. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2005, 35, pp.715-721. [CrossRef]

- Sigström, R.; Göteson, A.; Joas, E.; Pålsson, E.; Liberg, B.; Nordenskjöld, A.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Landén, M. Blood biomarkers of neuronal injury and astrocytic reactivity in electroconvulsive therapy. Mol. Psychiatry. 2024, pp.1-9. [CrossRef]

- McGrory, C.L.; Ryan, K.M.; Kolshus, E.; McLoughlin, D.M. Peripheral blood E2F1 mRNA in depression and following electroconvulsive therapy. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2019, 89, pp.380-385. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, W.J.; Kim, S.H.; Seo, M.S.; Kim, Y.; Kang, U.G.; Juhnn, Y.S.; Kim, Y.S. Repeated electroconvulsive seizure induces c-Myc down-regulation and Bad inactivation in the rat frontal cortex. Exp Mol Med. 2008, 40(4), pp.435-444. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).