Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- determine the impact of both internal and external shutter placement on the overall heat transfer characteristics of double-glazed window assemblies;

- -

- analyze the fluid dynamics and energy equations within the inter-pane air cavities and the heat conduction within solid components of the window structure under realistic operating conditions;

- -

- quantify the increase in thermal resistance achieved by incorporating shutters, and assess the effectiveness of shutters as a strategy for improving the energy efficiency of windows and building envelopes;

- -

- investigate the influence of various design and physical factors, including the geometric characteristics of the air cavity between the glazing unit and shutters, on the heat transfer processes;

- -

- validate the numerical simulations against experimental data to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the findings;

- -

- provide practical recommendations for the selection and implementation of shutters to optimize thermal performance in both new and retrofitted window systems.

2. Materials and Methods

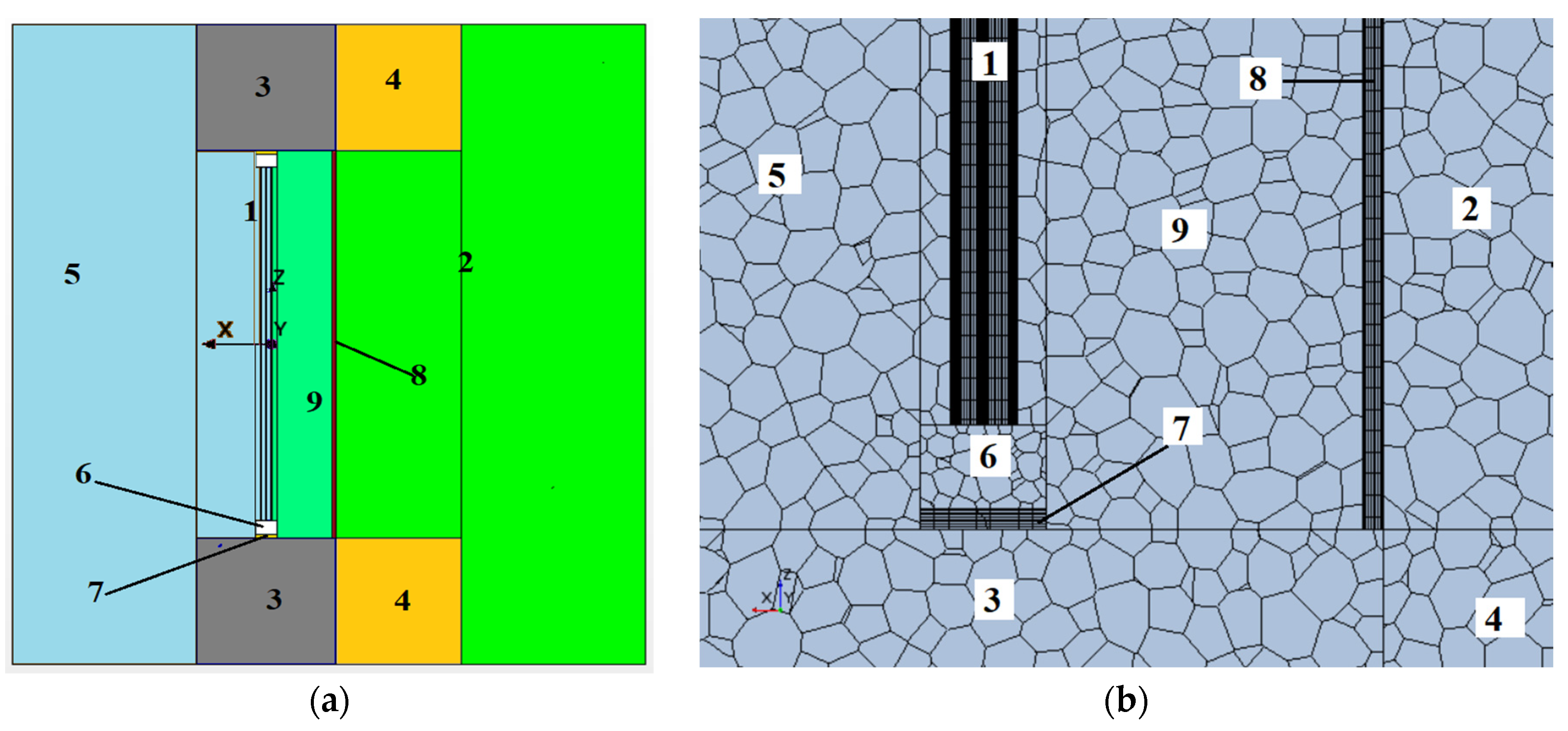

2.2. Physical Formulation of the Problem

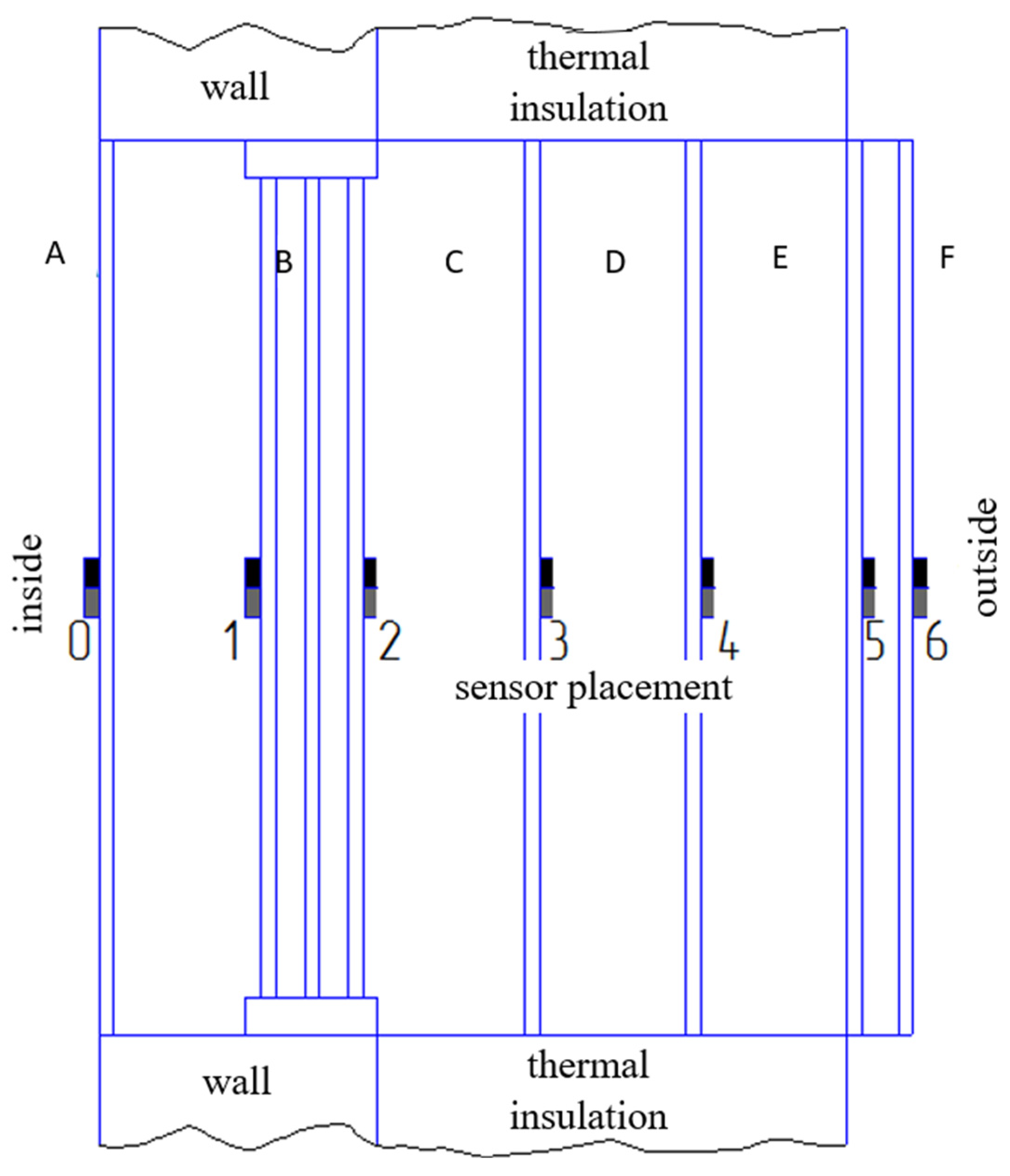

2.3. Methodology for Experimental Investigations Under Real-World Meteorological Conditions

3. Results

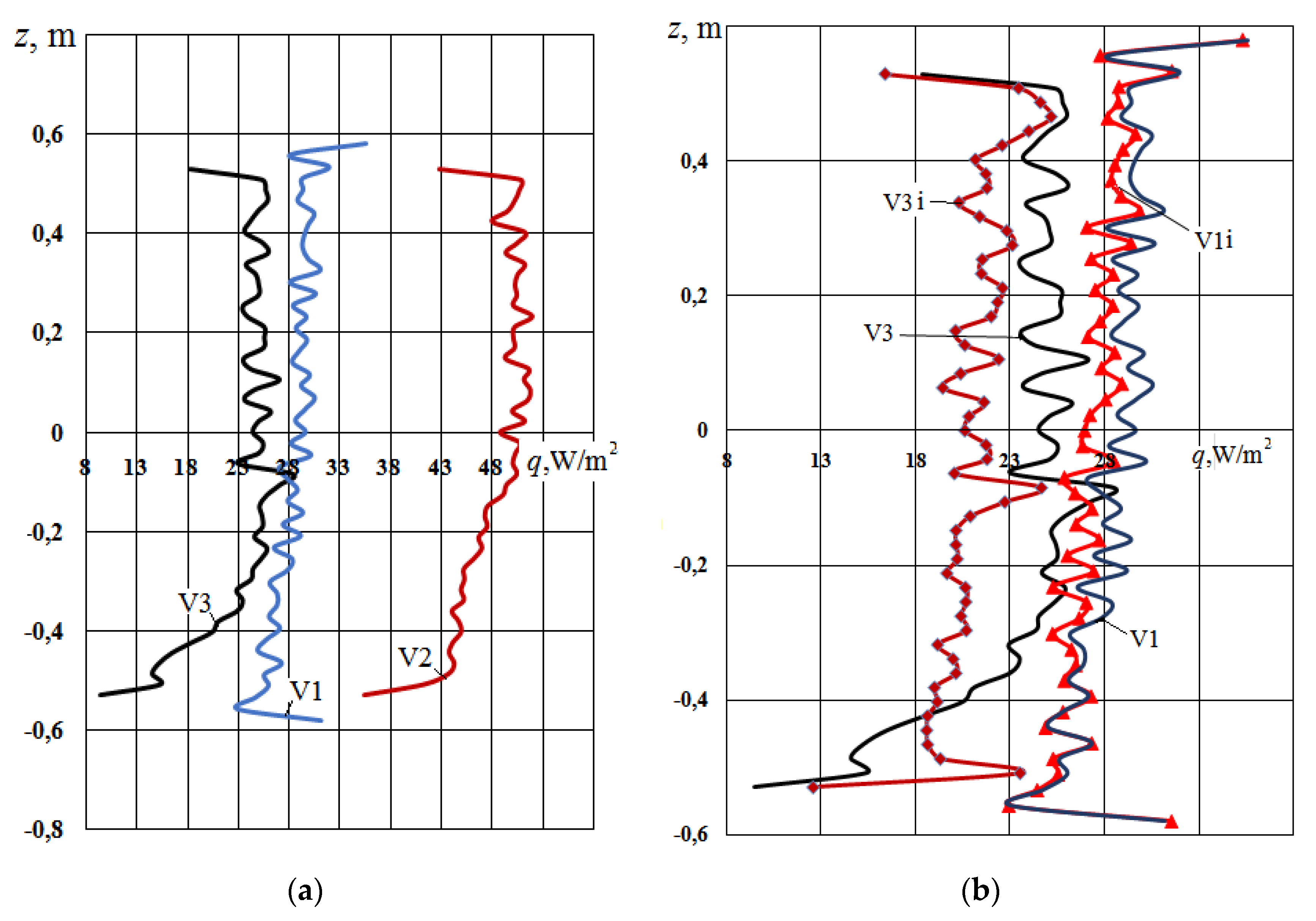

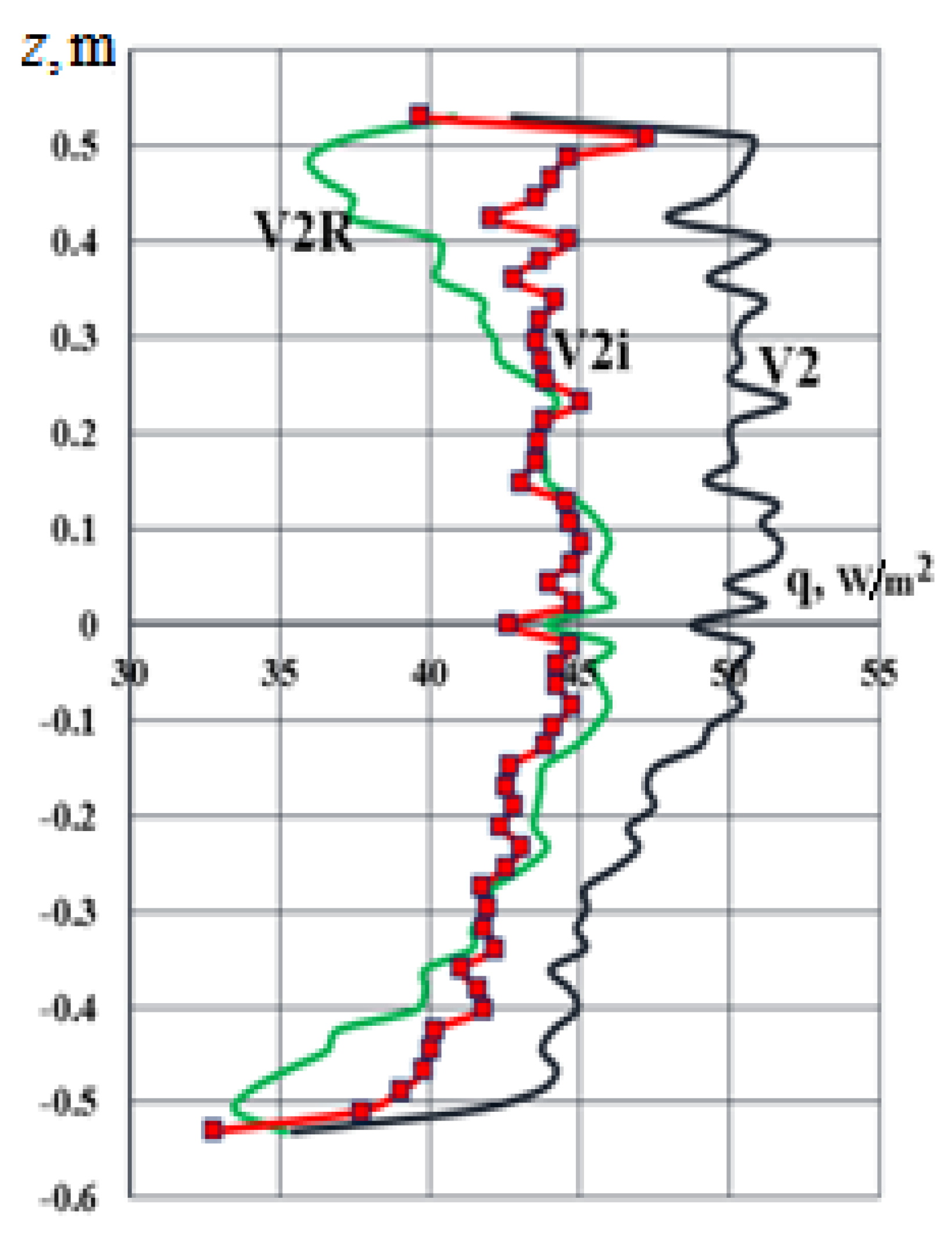

3.1. Analysing the Results of Numerical Studies

3.2. Results of Experimental Analysis Under Real Meteorological Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Insulatingshutters. https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Insulating_shutters.

- Shen, L.; He, B.; Jiao, L.; Song, X.; Zhang, X. Research on the development of main policy instruments for improving building energy-efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1789–1803. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.K.; Darsaleh, A.; Abdelbaqi, S.; Khoukhi, M. Thermal Performance Evaluation of Window Shutters for Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Abu Dhabi, UAE. Energies 2022, 15, 5858. [CrossRef]

- Tiago Silva, Romeu Vicente, Cláudia Amaral, António Figueiredo, Thermal performance of a window shutter containing PCM: Numerical validation and experimental analysis, Applied Energy, Volume 179, 2016, Pages 64-84, . [CrossRef]

- Maria Malvoni, Cristina Baglivo, Paolo Maria Congedo, Domenico Laforgia,CFD modeling to evaluate the thermal performances of window frames in accordance with the ISO 10077, Energy, Volume 111, 2016, Pages 430-438. [CrossRef]

- Ficker T. Heat Losses of Window Compact Shutters. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 960 (2020) 022021 IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Radl, J., & Kaiser, J. (2019). Benefits of Implementation of Common Data Environment (CDE) into Construction Projects. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 471. [CrossRef]

- Currie J., Williamson J.B., Stinson J., Jonnard M. Thermal assessment of internal shutters and window film applied to traditional single glazed sash and case windows. Historic Scotland Technical Paper 23. 2014. www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/technicalpapers.

- Hashemi A. and Gage S. (2014). Technical issues that affect the use of retrofit panel thermal shutters in commercial buildings. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology, 35 (1): 6-22. (DOI: 10.1177/0143624412462906).

- M. Che-Pan, E. Simá, A. Ávila-Hernández, J. Uriarte-Flores, R. Vargas-López, Thermal performance of a window shutter with a phase change material as a passive system for buildings in warm and cold climates of México, Energy and Buildings, Volume 281, 2023, 112775, . [CrossRef]

- Rolains Golchimard Elenga, Li Zhu, Steivan Defilla, Performance evaluation of different building envelopes integrated with phase change materials in tropical climates, Energy and Built Environment, Volume 6, Issue 2, 2025, Pages 332-346. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Sharda A. An Empirical Study of Thermal Transmittance through Windows with Interior Blinds. J Adv Res Mech Engi Tech 2017; 4(1&2): 10-16.

- Chaoen Li, Hang Yu, Yuan Song, Yin Tang, Pengda Chen, Huixin Hu, Meng Wang, Zhiyuan Liu, Experimental thermal performance of wallboard with hybrid microencapsulated phase change materials for building application, Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 28, 2020, 101051. [CrossRef]

- Foroushani Mohaddes S.S., Wright J.L., Naylor D., Collins M.R. Assessing Convective Heat Transfer Coefficients Associated with Indoor Shading Attachments Using a New Technique Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics. © 2015 ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). Published in ASHRAE Conference Papers, Winter Conference, Chicago, IL. For personal use only.

- Takada, K., Hayama, H., Mori, T., & Kikuta, K. (2020). Thermal insulated PVC windows for residential buildings: feasibility of insulation performance improvement by various elemental technologies. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 20(3), 340–355. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi A., Alam M., Kenneth Ip. Comparative performance analysis of Vacuum Insulation Panels in thermal window shutters. Technologies and Materials for Renewable Energy, Environment and Sustainability, TMREES18, 19–21 September 2018, Athens, Greece. Energy Procedia 157 (2019) 837–843. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

- Hashemi A, Gage S. Technical issues that affect the use of retrofit panel thermal shutters in commercial buildings. Building Services Engineering Research & Technology. 2012;35(1):6-22. [CrossRef]

- Ákos Lakatos, Zsolt Kovács, Comparison of thermal insulation performance of vacuum insulation panels with EPS protection layers measured with different methods, Energy and Buildings, Volume 236, 2021, 110771. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi A., Alam M., Mohareb E. Thermal Performance of Vacuum Insulated Window Shutter Systems. ZEMCH, International Conference l Seoul, Korea November 2019.

- Ariosto T., Memari A. M. Evaluation of Residential Window Retrofit Solutions for Energy Efficiency. The Pennsylvania Housing Research Center (PHRC). PHRC Research Series Report No. 111 The Pennsylvania Housing Research Center. December 2013.

- Jonathan Dahl Jørgensen, Jens Henrik Nielsen, Luisa Giuliani, Thermal resistance of framed windows: Experimental study on the influence of frame shading width, Safety Science,Volume 149, 2022, 105683, . [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka A. Lechowska, Jacek A. Schnotale, Giorgio Baldinelli, Window frame thermal transmittance improvements without frame geometry variations: An experimentally validated CFD analysis, Energy and Buildings, Volume 145, 2017, Pages 188-199. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Song, S.-Y. Evaluation of Alternatives for Improving the Thermal Resistance of Window Glazing Edges. Energies 2019, 12, 244. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, Jonathan Dahl, Jens Henrik Nielsen, and Luisa Giuliani. "Thermal resistance of framed windows: Experimental study on the influence of frame shading width." Safety Science 149 (2022): 105683. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, G.; Ruan, S.-T.; Qi, H. Dynamic coupled heat transfer and energy conservation performance of multilayer glazing window filled with phase change material in summer day. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104183. [CrossRef]

- Find the perfect shutters for your home. https://www.shutterland.com/.

- Basok, B.I.; Nakorchevskii, A.I.; Goncharuk, S.M.; Kuzhel, L.N. Experimental Investigations of Heat Transfer Through Multiple Glass Units with Account for the Action of Exterior Factors. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 2017, 90, 88.

- Basok, B.I.; Davydenko, B.V.; Isaev, S.A.; Goncharuk, S.M.; Kuzhel, L.N. NumericalModelingofHeatTransferThrough a Triple-PaneWindow. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 2016, 89, 1277.

- Hanna Koshlak, Borys Basok, Borys Davydenko. HeatTransfer through Double-Chamber Glass Unit with Low-Emission Coating. Energies 2024, 17, 1100. [CrossRef]

- Basok B., Davydenko B., Pavlenko A., Novikov V., Goncharuk S. Heat Transfer Characteristics of Combination of Two Double-chamber Windows. RocznikOchronaŚrodowiska. 2023. Vol. 25. Pp. 289-300.

- Basok B, Novikov V, Pavlenko A, Davydenko B, Koshlak H, Goncharuk S, Lysenko O. CFD Simulation of Heat Transfer Through a Window Frame. Rocznik Ochrona Środowiska. 2024; 26. [CrossRef]

- ISO 10211:2017. Thermal Bridges in Building Construction—Heat Flows and Surface Temperatures—Detailed Calculations; International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

| Serial number | Configuration description | Thermal resistance (m²K/W) | Percentage increase in thermal resistance relative to standard window | Increment in thermal resistance relative to preceding configuration (m²K/W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | standard 4M1i-10-4M1-10-4M1 window (DSTU V B2.7-107:2008) | 0.64 | - | - |

| 2 | window only (experimental data: 08-10.11.2024) | 0.63 / 0.64 | - | - |

| 3 | window with one shutter (experimental data: 15-16.11.2024) | 0.80 | 25 | 0.16 |

| 4 | window with two shutters (experimental data: 20-22.11.2024) | 0.99 / 0.97 | 53 | 0.18 |

| 5 | window with three shutters (experimental data: 22-25.11.2024) | 1.09 / 1.11 / 1.13 | 73 | 0.13 |

| 6 | window with four shutters (experimental data: 25-27.11.2024) | 1.27 / 1.25 | 97 | 0.15 |

| 7 | shutter + window with four shutters (experimental data: 25-02.12.2024) |

1.75 / 1.74 / 1.74 / 1.76 | 173 | 0.49 |

| Thermal resistance, (m²K/W) | Var1 | Var2 | Var3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| double-glazed unit (CFD Model) | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

| double-glazed unit with shutters (CFD Model) | 0.56 | - | 0.64 |

| double-glazed unit with shutters and i-coating (CFD Model) | 0.62 | - | 0.78 |

| double-glazed unit with i-coating (CFD Model) | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).